Abstract

In this paper, we study a two-parameter family of Stieltjes transformations related to holomorphic Lambert–Tsallis functions, which are a two-parameter generalization of the Lambert function. Such Stieltjes transformations appear in the study of eigenvalue distributions of random matrices associated with some growing statistically sparse models. A necessary and sufficient condition on the parameters is given for the corresponding functions being Stieltjes transformations of probabilistic measures. We also give an explicit formula of the corresponding R-transformations.

1. Introduction

This paper is a continuation of a previous paper [1] dealing with high-dimensional asymptotics of eigenvalue distributions of Gaussian and covariance matrices related to growing statistical sparse models. The paper [1] gives an explicit formula of Stieltjes transformations of the limits of empirical eigenvalue distributions on some Wishart-type ensembles. Asymptotics of empirical eigenvalue distributions are a classical topic of the random matrix theory (RMT). There are numerous interactions of RMT with important areas of modern multivariate statistics: high-dimensional statistical inference, estimation of large covariance matrices, principal component analysis (PCA), time series and many others; see the review papers by Diaconis [2] [Section 2], Johnstone [3], Paul and Aue [4], Bun et al. [5], and the book by Yao et al. [6] and references therein.

Stieltjes transformations and R-transformations are fundamental objects in Random Matrix Theory and Free Probability Theory, and basic tools for investigating probabilistic measures (cf. Voiculescu [7], Mingo and Speicher [8], and references therein). In particular, R-transformations admit some additive property with respect to a sum of two random matrices under some conditions. We study R-transformations associated with Wishart-type ensembles considered in [1] in detail in Section 3.

The previous paper [1] tells us that Stieltjes transformations of limiting density functions with respect to Wishart-type ensembles in [1] are described using a two-parameter generalization of the Lambert W function, called the Lambert–Tsallis function. It is an inverse function of the product of a linear fraction of z and the Tsallis q-exponential function; see (1) for a definition. We note that the Tsallis q-exponential function is now actively studied in information geometry [9,10] and physics [11,12,13]. There were several attempts to generalize the Lambert function in many directions. In Mezö and Baricz [14], z before is replaced by rational function of z (see also [15,16]) and in da Silva and Ramos [11], is replaced by the Tsallis q-exponential function. The matrix Lambert W function is considered in [17,18].

In Section 4, we investigate Lambert–Tsallis functions in detail to obtain a complete set of parameters such that the corresponding functions are Stieltjes transformations of probabilistic measures. The proofs are in Section 5.

The results of this paper should be useful in further applications of Lambert–Tsallis functions in the Random Matrix Theory, in particular Theorem 3 and Corollary 2, and also the open problem formulated below it.

This paper can be read independently of the paper [1], if the reader admits Theorem 1 below.

2. Preliminaries

We begin this paper by fixing basic notions. The sets of real numbers and complex numbers are described and , respectively. We set . We denote by the space of matrices with real coefficients. When , we simply write . For a matrix , its transpose matrix is denoted by .

For a non-zero real number , we set

where we take the main branch of the power function when is not an integer. If , then it is exactly the so-called Tsallis q-exponential function(cf. [9,10]). For the sake of simplicity, we use the parameter rather than q. By virtue of , we define .

For two real numbers such that , we introduce a holomorphic function , which we call generalized Tsallis function, by

Analogously to Tsallis q-exponential, we also consider . In particular, . Since it is easily verified that , the function has an inverse function in a neighborhood of .

Such a function appears in the study of Wishart-type random matrices in the previous paper [1]. Let us consider the limit of eigenvalue distributions of matrices of the form

Here, we constraint that the ratio converges to a constant c as n grows, and the angle parameter is independent of n. Set and . Then, the Stieltjes transformations corresponding to the limiting eigenvalue distributions are given as follows.

Here, we constraint that the ratio converges to a constant c as n grows, and the angle parameter is independent of n. Set and . Then, the Stieltjes transformations corresponding to the limiting eigenvalue distributions are given as follows.

Theorem 1

([1] [Proposition 4.7]). The Stieltjes transformation corresponding to the limiting eigenvalue distribution with respect to is given as

Here, is the Lambert–Tsallis function, which is the holomorphic extension of the inverse function of the generalized Lambert function . In the current situation where the parameters satisfy , such an extension is unique.

This theorem tells us that we have a two-parameter family of Stieltjes transformations related to Wishart-type random matrices. Then, it is natural to raise the question of whether the domain of parameters can be extended or not. This is half of the aim of this paper.

The other half is to investigate the corresponding R-transformations in detail. By Theorem 1, we can obtain the formula of the corresponding R-transformations as in Proposition 4.7 of [1]. R-transformations relate to the theory of free probability, and they have interesting properties such as homomorphism with respect to asymptotically free elements. We first work on this topic.

3. R-Transforms

We review here the basic properties of R-transformations. For a probability measure , we let be its Stieltjes transformation. Its R-transformation is defined as

as a formal power series at first, and it is shown that it can be defined as an analytic function on a domain in . In particular, if has compact support, then it is known that the corresponding R-transformation is analytic around .

In this section, we consider the limiting eigenvalue distributions with respect to Wishart matrices of the form (2). We have calculated the support of explicitly in Theorem 18 of the previous paper [1]. It tells us that has compact support so that the corresponding R-transformations are analytic in a neighborhood of . To state formulas, we recall that the inverse function of the Tsallis exponential is given as

Theorem 2.

The R transformation corresponding to is given as

If we set , then the above equation can be reformulated as

Remark 1.

The first equation is given in Proposition 4.7 in [1], whereas the second seems to be new. We also give a proof of the first equation for the reader’s convenience.

Proof.

The R-transformations and the Stieltjes transformations relate in the formula . Here, stands for the inverse function of . For a Stieltjes transformation , it is known that its inverse exists for z such that is large enough, and it can be analytically continued to . Thus, we first calculate the inverse of . Assume that is large enough. Then, since , we see that is enough small. By the second equality of Theorem 1, we have

By the definition of , we obtain

which implies the following formula for enough small:

Thus, we arrive at

Next, we consider the second assertion. Since for , we have

Thus, by setting , we obtain

Noticing , we obtain

We have shown that the assertions are valid for z in a neighborhood of . On the other hand, we know that R-transformations of are analytic around so that we have proved this theorem by the identity theorem for analytic functions. □

The following corollary is a direct consequence of Theorem 2.

Corollary 1.

In the setting of (2), we decompose as , where corresponds to the triangular part of , and the rectangular part. Then, can be viewed as a sum of and . Let (resp. and ) be the R-transformation with respect to (resp. and ). Then, one has

Proof.

Suppose that the aspect ratios of and are and c, respectively. Then, the shape parameters and of are given as

By Theorem 2, the R-transformations and are given, respectively, as

and is just the R-transformation with respect to the Marchenko–Pastur law of parameter c so that

Thus, it is now obvious that we have . □

Although R-transformations have some additive property on a sum of two probabilistic measures, this corollary is not trivial because we do not know whether or not triangle Wishart ensembles and Wishart ensembles are asymptotically free. In fact, we have a counterexample of such a decomposition formula as follows. We first recall that the R-transformation of Marchenko–Pastur law with parameter c is given as

Let us set . In this case, the corresponding matrices are a kind of triangular matrices in . Since an ordering of column vectors in does not affect the resultant, the matrices can be viewed as two copies of triangular matrices, that is,

where and are upper triangular matrices in . By Theorem 2, we see that the R-transformation corresponding to is given as

This shows that the limit of density functions of the sum of two triangle Wishart ensembles is equal to that of MP laws with parameter :

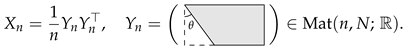

where are triangular matrices and M is a square random matrix (see Figure 1). On the other hand, Theorem 2 also tells us that the R-transformation with respect to is given as

We have thus confirmed that

which shows that two triangle Wishart matrices are not asymptotically free. Recall that if two random matrices are asymptotically free, then the corresponding R-transformations admit an additivity property, that is, the R-transformation corresponding to their sum is equal to the sum of their R-transformations (cf. Chapter 4 of [8], see also [7]).

Figure 1.

The left one indicates the histogram of eigenvalues of , whereas the right that of .

4. A Two-Parameter Family of Stieltjes Transforms

In this section, we investigate the parameter domain of such that is a Stieltjes transformation of a probability measure. To do so, we first give an explicit definition of Lambert–Tsallis functions.

Let be the domain of , i.e., if is integer then , and if is not integer, then

Let and we set for finite , where stands for the principal argument of w; . Since we now take the main branch of the power function, we have for finite

If , then we regard as y because we have . Then, implies

If , then does not vanish so that y needs to be zero. This means that if with , then we have . Thus, Equation (3) for can be rewritten as

For , we set . If , then since , we have . Here, we take the main branch of , i.e., we have . Let us introduce a connected domain by

where denotes the connected component of an open set containing . Please note that since F is an even function in y, the domain is symmetric with respect to the real axis. Set

Definition 1.

If there exists a unique holomorphic extension of to , then we call the Lambert–Tsallis function.

Remark 2.

Strictly speaking, the Lambert–Tsallis function is the main branch of the multivalued Lambert–Tsallis W function (recall that ). In our terminology the Lambert–Tsallis W function is multivalued and the Lambert–Tsallis function is single-valued. In this paper, we only study among other branches of the Lambert–Tsallis W function.

Our goal now is to prove the following theorem which allows the determination of the parameter domain of such that is a Stieltjes transformation of a probability measure.

Theorem 3.

There exists the main branch of the Lambert–Tsallis W function if and only if (i) and , or(ii) and , or(iii) and . Moreover, maps onto bijectively.

We conclude by giving the range of parameters such that the corresponding function is the Stieltjes transformation of a probabilistic measure.

Corollary 2.

is the Stieltjes transformation of a probabilistic measure if and only if:

(i) and , or (ii) and , or (iii) and .

Recall from [1] that if (i) and or (ii) and , then there exists a large random matrix model of the form (2) such that the Stieltjes transformation of its spectral limit is . It is an interesting open problem whether or not a large random matrix model exists with as the spectral limit for the following cases:

- (a)

- and ,

- (b)

- and ,

- (c)

- and .

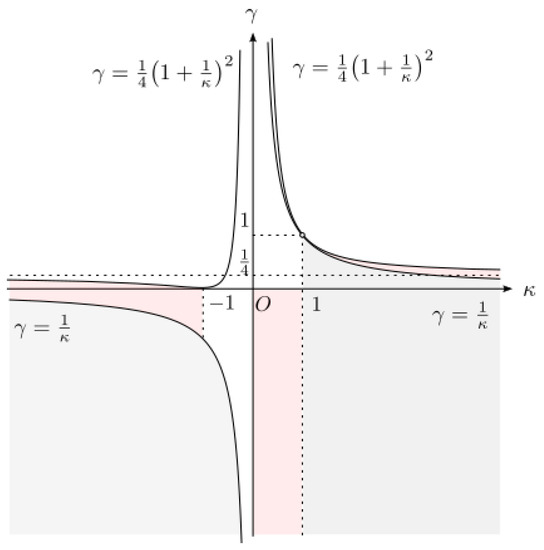

Figure 2 indicates the parameter domain on and . The grey area corresponds to random matrices of the form (2) and the red area corresponds to Stieltjes transformations of a probabilistic measure in cases (a), (b), (c).

Figure 2.

The parameter domain on and .

Remark 3.

As we shall see in Section 5.4, in the case and , the function maps two-to-one, and hence a holomorphic extension of exists on a smaller domain in

which is mapped by

bijectively to , but it is not unique. In the case and , the function is not surjective. It is well known that a function on is a Stieltjes transformation of a probability measure if and only if is analytic function of with . Thus, the Theorem 3 shows that for parameters outside of the theorem cannot be a Stieltjes transformation of a probability measure.

Remark 4.

In [1], we have proven Theorem 3 for the case and , and when and . Please note that the case can be derived from the case ; see Section 5.4.5. Therefore, the sufficiency in the Theorem 3 is essentially new in the three cases (a),(b),(c).

Please note that for these cases are not obtained from Wishart-type random matrices as in (2). The necessity part in the Theorem 3 is also a new result.

5. Proof of Theorem 3

The proof of the Theorem 3 is conducted in two steps. More precisely, we first give an explicit expression of , and then show that maps to bijectively.

5.1. Properties of the Generalized Tsallis Function

In this section, we investigate the function in detail to prepare the proof of the Theorem 3. Let us change variables in (4) by

Set and

Then, Equation (4) can be written as

If , then (9) has a solution

Thus, for each angle , there exists at most two points on . Since the change (7) of variables is the polar transformation, we need to know whether is positively real or not. To do so, we shall study the function

Remark 5.

Intuitively, if for some then the domain become bigger and the function maps to the whole , which threatens the unicity of . On the other hand, if then which implies that the angle θ such that is included in . When , or equivalently , it may fail that for , which violates the bijectivity of . The discussions below will justify such intuitive arguments with a slightly complicated calculation.

We first consider because . Set

Since for , we exclude these two cases.

Lemma 1.

Let us set .

- (1)

- Suppose that , or . If , then there exists a unique such that , and one has for , and otherwise. If , then one has for any .

- (2)

- Suppose that . If , then there exists a unique such that , and one has for , and for . If , then one has for any .

Proof.

Let us set for

For , we have

and hence can be written as

Let us set

Then, the signatures of and are the same on the interval , and hence we actually work with . We have for any , and

and

In fact, we have when . The derivative of is given as

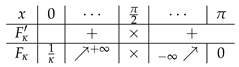

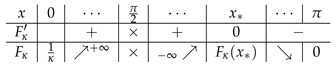

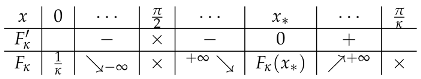

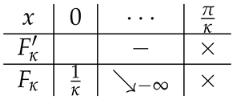

We note that the condition comes from a condition . According to a case classification with respect to (cf. Table 1), we need to consider the following four cases: (i) , (ii) , (iii) , and (iv) .

Table 1.

Monotonicity table of .

Let us first consider the equation

Since does not depend on , it is important to know where it meets end points or maximal/minimal values of . By Table 1, for end points, they are or 0, and its solutions on a are given as or , respectively. If (), then we need a solution of . Since is bijective, there exists a unique solution such that .

The proof can be done by considering further cases according to the position of . The calculations are delicate and tedious but elementary, and, thus, we only give proof for the case and .

Assume that . In this case, we have by (12). Recall that is monotonic decreasing in a in this situation. Let be the maximal point of in . Then, we have . In fact, since , we have and hence it implies that

Here we use and . Let be the unique solution of in a. Then, we see that by . Table 1 tells us that we have three cases in Equation (14) as follows.

- (a)

- It does not have a solution if , which is equivalent to the condition . Since , we see that in this situation.

- (b)

- The Equation (14) has a unique solution if or . In the former case, the condition is equivalent to , and we have and . In the latter case, we have , and the condition is divided into two situations; one is , and the other is .

- (c)

- The Equation (14) has two solutions if , which is equivalent to the condition so that . We note that we have , and if then we have . We only deal with case (c).

Let us assume that , i.e., . In this situation, the signature of is negative in the interval and , and positive in . To show that (), which implies for any , we calculate in a different way as follows. By differentiating using expression (8), we obtain

and hence can be also described as

Since satisfy by definition, we see that

Now we assume and we know so that we have and for by (16). Since , we see that and hence we obtain by (15). Thus, we conclude on the interval .

The other cases can be done similarly. □

5.2. The domain for

Now, we can obtain explicit formulas for . Please note that since is a continuous function, the boundary is included in the set .

Proposition 1.

Suppose that .

- (1)

- If , then .

- (2)

- If , then .

- (3)

- If , then .

- (4)

- If , then , which is bounded.

Proof.

In the case , we have so that . Thus, we have

Please note that is contained in the set

Since it is connected, the proof is completed. □

Set and . Let be the solutions of Equation (9) and let , be the solutions of the equation which come from rational part of . If are real, then we assume that , and if not, then we assume that . Recall that and .

Proposition 2.

Let with . For , one sets . Then, can be described as follows.

- (1)

- If , then there exists a unique such that and that are both positive with on . Moreover,In particular, is bounded. One has and , whereas .

- (2)

- If , then one has which is positive on the interval . Moreover,has an asymptotic line . One has and .

- (3)

- If , then is the only positive solution of on , andOne has , whereas . If , then has an asymptotic line . Please note that if then .

- (4)

- Suppose that and .

- (a)

- If , then one has and for , and . One has and .

- (b)

- If , then one has and for , andOne has , while . Moreover, has an asymptotic line .

- (5)

- Suppose that .

- (a)

- If with , then are both positive in with , andhas an asymptotic line . One has , but , .

- (b)

- If and , then there exists a unique such that , and are both positive in the interval . Moreover,In this case, , are both non-real numbers and one has and . Moreover, has an asymptotic line .

- (c)

- If , then there is no such that , and one has .

Proof.

Since is symmetric with respect to the real axis, we shall actually work with the boundary of . The cases (1)–(3) are done in the previous paper [1], and thus we omit them.

(4) Assume that and . In this case, , are given as or , and Equation (9) reduces to , whose solutions are , . Since can be described as in this case, it is easily verified that, if then , and if then for any . This means that if then the Equation (9) does not have a positive solution, and hence we have

which shows . Since we have and , the assertion (4)-(a) is proved. On the other hand, if , then we have for by Lemma 1 together with the fact for any . Since and , the function is monotonic increasing on and therefore we have . Thus, the curve , has an asymptotic line with gradient , which is determined later. Therefore, we have

In this case, we have and . The assertion (4)-(b) is now proved.

(5) Suppose that and . In this case, we have and

Please note that if . Since , two solutions of (9) have the same signature if are real.

(a) We first consider the case and . Let us show that for . If we set , then the condition is equivalent to , and hence we have because if . By the assumption , we see that for any by Lemma 1 so that b is monotonically decreasing in this interval. Since , the function b is negative in , and hence so that is monotonic increasing in the interval , and in particular, it is positive on . Thus, we see that are real on , and by we have . Since for

we have , and hence the function is monotonic increasing, whereas is monotonic decreasing because . Please note that we have and as . Thus, , draws an unbounded curve connecting to ∞ with an asymptotic line with slope , and , draws a bounded curve connecting to . Since we have and since is the connected component including , we have

(b) Next, we assume that and . According to Lemma 1 (1), we consider the function in two cases, that is, (i) and (ii) .

(i) Assume that . Then, is negative and hence is monotonically decreasing. Since , we see that for any and therefore for any . Thus, is monotonic increasing with . Since as , we see that there exists a unique such that , and are real for . In this interval, since , we see that are both positive. By (17), we have and thus the function is monotonic increasing, whereas is monotonic decreasing because . As , we have and . This means that draws an unbounded curve connecting and , and draws a bounded curve connecting and , where is the complex solution of with positive imaginary part. Since we have , the domain is given as

(ii) Assume that . In this case, we have and as . Then, there are two possibilities on , i.e., it is positive or negative. If , then has a unique minimal point at . On the other hand, if , then there exist exactly two in such that . Then, has a unique maximal point at whereas there are exactly two minimal points at in . We note that . Since , if , then are both negative so we need not deal with this case. Thus, regardless of whether is positive or not, there exists a unique such that and for any . By (17), we see that is monotonic increasing on , whereas is monotonic decreasing. Moreover, we have and as , and hence the curves , form an unbounded curve connecting and . Since , we have

(c) We finally assume that . In this case, we have . We note that implies . In fact, means so that

Since , the signatures of are the same, and they are the opposite of the signature of .

Let be the maximal interval such that D is positive on . We shall show that there are no suitable solutions of (9), i.e., for any , which yields that and hence . Let us recall Lemma 1.

(i) Assume that and . In this case, has a unique maximal point at , and we have . If , then we see that for any , which implies for any . If , then there exists a unique such that , and we have by (18). Hence, have a unique maximal point at and a unique minimal point at . Thus, is included in and b is positive on , whence for any .

(ii) Assume that and . Then, Lemma 1 tells us that for any . Thus, is monotonic decreasing on the interval with , and hence for any . This means that and is monotonic decreasing on . Since , we see that and hence for any .

(iii) Assume that . In this case, we have we have for any so that is monotonic increasing. In fact, if , then since for and since , we always have so that by Lemma 1, and if then we have so that . If , then we have for any and hence we see that for . If then there exists a unique such that . Thus, has a unique minimal point with and , and hence there are no such that and . Thus, we have for , which implies .

We shall determine an asymptotic line with respect to when as or . To calculate them in one scheme, we set or , and denote its denominator by k. A line with gradient can be written as with some constant A. Let us determine the constant A. Since and as in (7), we have

A simple calculation yields that as , which implies

Since can be described as

we have

Thus, we have

and, therefore, the proof is now complete. □

5.3. The Domain for

In this section, we deal with the case . Since is regarded as y in this case, Equation (4) can be written as

Proposition 3.

Assume that and let , be solutions of with if they are real.

- (1)

- If , then one has .

- (2)

- Suppose that . Then, there exists a unique function defined on such thatThe function has a unique minimal point and tends to π as .

- (3)

- If , then , are both real for any , and one has

- (4)

- Suppose that . Then, there exists a unique such that and if then , are real. Moreover, one hasIn particular, is bounded.

Proof.

As with the proof of Proposition 2, we work with . Let us assume .

(i) The case is dealt in the previous paper [1], and hence we omit it. Please note that The case corresponds to the case of the classical Lambert function (cf. [19]).

(ii) Assume that . Since there are no solutions of (19) on the line and since is symmetric with respect to the real axis, it is enough to consider y in the interval . The Equation (19) can be calculated as

Let us set . Then, the function satisfies

In order that Equation (20) has a real solution in x and y, the function needs to be non-negative, and it is equivalent to the condition that the absolute value of the function is less than or equal to 1. Therefore, we investigate the function . At first, we observe that and . Its derivative is calculated as

Set . Then, the signature of can be determined by the product of signatures of , and .

(ii-1) Assume that . If , then we have and hence there exists a unique such that . If , we have so that there exists a unique such that . Thus, for both cases, has a unique maximal point at with and . If , then we have , whence for and for so that in this case is the only solution of for .

These observation shows that, if , then there exists one and only one such that and for . In this case, is non-negative in the interval , and for . Let , be the real solutions of Equation (20) with . Then, since we have , the curves , form a connected curve. Moreover, since the correspondence of to is one-to-one and since , and as , the function connecting the two inverse functions of is defined for any and its image is . Thus, we have

(ii-2) Assume that . Then, we have and hence there are no such that . Thus, we obtain for any so that g is monotonic decreasing from to . This shows that is non-negative in the interval . Let , be the solutions of Equation (20) with . Then, since and as , we have by

which completes the proof. □

5.4. Bijectivity of

In this section, we investigate whether maps to bijectively, where . Then, since , the bijectivity of from to is obtained at the same time.

The key tool is the argument principle (see Theorem 18, p.152 in [20], for example).

Theorem 4

(The argument principle).If is meromorphic in a domain with the zeros and the poles , then

for every cycle γ which is homologous to zero in

and does not pass through any of the zeros or poles. Here, is the winding number of γ with respect to a.

We also use the following elementary property of holomorphic functions.

Lemma 2.

Let be a holomorphic function. The implicit function has an intersection point at only if .

5.4.1. The Case and

This case is made in the previous paper [1], and thus we omit it.

5.4.2. The Case and

In this case, Propositions 1–3 tell us that is unbounded. We first consider defined in (6). Please note that the case is the trivial case .

Lemma 3.

Let , be the solutions of .

- (1)

- Assume that or together with . Then, are both real and with . Please note that is included in this case.

- (2)

- Assume that and . Then, are both real, and one has with . Please note that is equivalent to .

- (3)

- Assume that or together with . Then, are both non-real, and one has . On the other hand, one has .

Proof.

The proof is elementary, so we only deal with the latter assertion in (3). It is easily verified that as by . Propositions 1–3 show that if a point is on the curve , then we have and

This means that if goes to ∞ along the path , then must tend to . On the other hand, taking a limit along is equivalent to in this case and hence . Since is continuous, the assertion is now proved. □

For , let be the circle of origin with radius L. We distinguish cases according to this lemma.

Case . In this case, is given in Propositions 2 or 3. Let us take a path , in such a way that by starting from , it goes to along the curve describing in the upper half plane, and then goes to along the real axis. Here, we can assume that whenever , because otherwise. We take an arc-length parameter t so that represents the direction of the tangent line at . Lemma 2 tells us that is a monotonic increasing function on such that as and as .

We shall show that for any there exists one and only one such that . Recall that for any . Let us take an such that . For an , let , be two distinct intersection points of C and . Please note that we can take and . Let be a closed path obtained from C by connecting and via the arc of included in .

Let be the inside set of . Since is non-singular on the arc , the curve does not have a singular point so that it is homotopic to a semicircle in . In particular, we can take an L such that its radius is larger than R so that the inside set of the curve is a bounded domain including . Since the winding number of the path about is exactly one, we see that

Since does not have a pole on by definition, the function has only one zero point, say , by the argument principle in Theorem 4. Then, we obtain , and such is unique. Since we can take arbitrary, we conclude that the map is a bijection from to the upper half plane .

Case . In this case, is given in Proposition 1 (2). As in the case (1), it is enough to show that an approximating domain of satisfies that the image of its boundary curve under has a winding number about being exactly one for any .

By the proof of Proposition 1, the boundary of can be described as a path , defined in a such a way that by staring , it goes to along the real axis, and then it goes to along the curve , which is a semicircle of origin with radius , and then it goes to along the real axis. Notice that for any except for such that , . In particular, Lemma 2 tells us that is monotonic increasing in the interval , and hence the function maps to bijectively. Therefore, we can construct an approximating domain from and similar to case (1), such that the image of its boundary under has a winding number being exactly one, and hence we have shown the bijectivity of on to .

Case . In this case, we shall show that the approximating domain of satisfies that the image of its boundary curve under has a winding number about being exactly two for any , and hence the function maps to two-to-one.

(i) Let us assume that . The domain is given in Proposition 2 (5-b). Let , be a path defined in such a way that by starting from , it goes to along the curve , and then goes to along the real axis. Let such that . Then, Lemma 3 (3) tells us that maps to bijectively, and hence we see that it maps to in two-to-one correspondence. Let and its boundary. the image of its boundary curve under has a winding number about being exactly two for any , and hence the function maps to two-to-one.

(ii) Assume that together with , i.e., . Then, is described in Proposition 3 (2). Take a large and a small such that . Then, we approximate by the curve , defined in such a way that for and , by starting from , it goes to along the real axis avoiding along a semicircle of radius in , and next to along the line parallel to the imaginary axis, and next to along and finally goes back to along the line parallel to the imaginary axis. Then, since , we can choose such that

and since and are bounded around , we can choose such that . Since is non-singular on the lines , , the curve , contains the domain obtained from a semicircle of radius R removing a semicircle of radius . In particular, it contains . Since we can show that the winding number of the path with respect to is exactly two, we conclude that the function maps to in a two-to-one way by a similar argument as in (i) above.

5.4.3. The Case and

Although this case is out of the result stated in the previous paper [1], the same proof given there (see the supplementary material of [1]) is valid, and therefore we omit it.

5.4.4. The Case and

In this case, Proposition 2 tells us that if then , and if then . If maps to bijectively, then it needs map to . However, if satisfies , then tends to as via the arc . Since , then we see that is not real and therefore cannot map to bijectively.

5.4.5. The Case of

We shall complete the proof of Theorem 3 by proving it for the case . To do so, let us recall the homographic (linear fractional) action of on : for and . For each , the corresponding homographic action map to bijectively. Let with positive . Consider the transformation

Notice that this transformation can be written as a homographic action as , and hence it maps to bijectively. Then, since

(recall that we are taking the main branch so that ), we obtain

Set . Since homographic actions map to bijectively, there exists a domain such that maps to bijectively if and only if it holds for . Thus, the condition is equivalent to , and the condition and with is equivalent to

This shows the case , and, therefore, we have completed the proof of Theorem 3.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, H.N.; Project administration, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Japan Science and Technology Agency CREST Project JPMJCR2015 (manager: Kenji Fukumizu). The first author was supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS fellows (2018J00379). Both authors are supported by the French grant GDR MEGA Matrices et Graphes Aléatoires 2017–2023. This work was partly supported by MEXT Promotion of Distinctive Joint Research Center Program JPMXP0619217849. The authors are grateful to the Centre Henri Lebesgue ANR-11-LABX-0020-01 for the support of this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the referees for invaluable comments by which the present paper has been improved considerably.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Nakashima, H.; Graczyk, P. Wigner and Wishart ensembles for sparse Vinberg models. Ann. Inst. Stat. Math. 2022, 74, 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconis, P. Patterns in eigenvalues: The 70th Josiah Willard Gibbs lecture. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 2003, 40, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, I.M. High dimensional statistical inference and random matrices. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians, Madrid, Spain, 22–30 August 2006; pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, D.; Aue, A. Random matrix theory in statistics: A review. J. Statist. Plann. Inference 2014, 150, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bun, J.; Bouchaud, J.P.; Potters, M. Cleaning large correlation matrices: Tools from Random Matrix Theory. Phys. Rep. 2017, 666, 1–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zheng, S.; Bai, Z. Large Sample Covariance Matrices and High-dimensional Data Analysis; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Voiculescu, D. Limit laws for random matrices and free products. Invent. Math. 1991, 104, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingo, J.A.; Speicher, R. Free Probability and Random Matrices; Fields Institute Monographs; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 35. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, S.; Ohara, A. Geometry of q-exponential family of probability distributions. Entropy 2011, 13, 1170–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.D.; Ng, H.K.T.; Shi, Y.M. Information geometry on the curved q-exponential family with application to survival data analysis. Phys. A 2018, 512, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.B.; Ramos, R.V. The Lambert-Tsallis Wq function. Phys. A 2019, 525, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.V. Analytical solutions of cubic and quintic polynomials in micro and nanoelectronics using the Lambert-Tsallis Wq function. J. Comput. Elect. 2022, 21, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, I.; Katori, M. Hydrodynamic limit of multiple SLE. J. Stat. Phys. 2018, 171, 166–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezö, I.; Baricz, Á. On the generalization of the Lambert W function. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2017, 369, 7917–7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamilla, C.; Mendoza, R.; Mezö, I. Solutions of neutral delay differential equations using a generalized Lambert W function. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 382, 125334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, A.; Scott, T. Fleshing out the generalized Lambert W function. ACM Commun. Comput. Algebra 2016, 50, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corless, R.; Ding, H.; Higham, N.; Jeffrey, D. The solution of s exp(s) = a is not always the Lambert W function of a. In Proceedings of the ISSAC 2007, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 28 July–1 August 2007; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima, S. Verified computation for the matrix Lambert W function. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 362, 124555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corless, R.M.; Gonnet, G.H.; Hare, D.E.G.; Jeffrey, D.J.; Knuth, D.E. On the Lambert W function. Adv. Comput. Math. 1996, 5, 329–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfors, L. Complex Analysis, An Introduction to the Theory of Analytic Functions of One Complex Variable, 3rd ed.; International Series in Pure and Applied Mathematics; McGraw-Hill Book Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).