Abstract

The Curie–Weiss model for quantum measurement describes the dynamical measurement of a spin- by an apparatus consisting of an Ising magnet of many spins coupled to a thermal phonon bath. To measure the z-component of a spin l, a class of models is designed along the same lines, which involve order parameters. As required for unbiased measurement, the Hamiltonian of the magnet, its entropy and the interaction Hamiltonian possess an invariance under the permutation mod . The theory is worked out for the spin-1 case, where the thermodynamics is analyzed in detail, and, for spins , the thermodynamics and the invariance are presented.

PACS:

03.65.Ta Foundations of quantum mechanics; measurement theory; 03.65.Yz Decoherence; open systems; quantum statistical methods; 05.30.-d Quantum statistical mechanics; 05.30.Ch Quantum ensemble theory

1. Introduction

The interpretation of quantum mechanics has long been shrouded in mystery. The best working formulation involves the Copenhagen postulates, while various other attempts are summarized in Ref. [1]. While a plethora of (semi-) philosophical papers have been written on the subject, the one and only touchstone between the quantum formalism and the reality in a laboratory lies in quantum measurement, hence this connection has been the focus of our research in the last decades.

Indeed, while indispensable for introductory classes in quantum mechanics, “Copenhagen” skips over the reality of a real apparatus performing a measurement in a laboratory, and thus bypasses the physics to which it pretends to provide interpretation. It is best seen as a short cut to the reality of measurement, useful for introductory courses on quantum mechanics, but lacking rigour at a fundamental level.

What is needed is a complete modelling of the whole system plus apparatus (S+A) setup, and the dynamics that takes place. The literature on models for measurement was reviewed by “ABN”, our collaboration with Armen Allahverdyan and Roger Balian, in our 2013 “Opus Magnum” [2], a paper which we will term “Opus” in the present work. A typical early example of measurement models is Hepp’s semi-infinite chain of spins , which measures the first spin [3]; Bell terms it the Coleman–Hepp model [4]. Gaveau and Schulman consider a ring of such spins and extend the model to measure an atom passing near one of the spins of the ferromagnet. If the atom is in the excited state, it enhances the phonon coupling of that spin to the lattice, so as to create a critical droplet that flips the overall magnetization [5]. Another model is the few-degrees-of-freedom setup of an overdamped large oscillator measuring a small one [6,7]. To employ a Bose–Einstein condensate as a measuring apparatus has been proposed by ABN [8]. There is an entire amount of literature on the puzzling idea that only the environment is needed to describe quantum measurements [9,10,11].

To back up the popular von Neumann–Wheeler “theory” of quantum measurement, put forward in von Neumann’s 1932 book on the Hilbert space structure of quantum mechanics [12,13], no working models are known to us, so that the ensuing “relative state” [14] or “many worlds interpretation” [15,16] remains at an intuitive level. The apparatus is supposed to start and remain in a pure state. Our own approach employing Hamiltonians for the measurement dynamics as elaborated in the next paragraph considers the apparatus to start in a metastable thermal state and to end up in a stable one. In the von Neumann-Wheeler philosophy, one would have to slice the initial mixed state in pure components and identify representative ones as “pure states of the apparatus’’. But these “states” interact with each other during the dynamical phase transition that makes the pointer indicate the outcome, so that the representative sliced “pure states” at the final time were extremely improbable initially, which makes the connection unnnatural.

Progress was made in this millenium, when our ABN collaboration introduced the “Curie–Weiss model for quantum measurement” [17]. Here, for a system S, which is just a spin- that does not evolve in time, the operator is measured by an apparatus A. The latter consists of a magnet M and a thermal bath B. M contains spins- and B is a harmonic oscillator bath in a thermal state at temperature T. The model appears to be rich enough to deal with various fundamental issues in quantum measurement. Many details of the dynamics and subsequently the thermodynamics were worked out in various followup papers [18,19,20,21,22] and further expanded and summarized in “Opus” [2]. Lecture notes on the subject were presented [23]. A straightforward interpretation for a class of such measurements models was provided [24]. A paper on teaching the ensuing insights is in preparation [25]. A numerical test on a simplified version of the Curie–Weiss model by Donker et al. reproduced nearly all of its properties [26].

The dynamics of the measurement can be summarized as follows: In a very small time window after coupling the system S to the apparatus A, there occurs a truncation of the density matrix (erasing Schrödinger cat terms) due to the first dephasing in the magnet and then decoherence due to the phonon bath. On a longer time scale, the registration of the measurement takes place because the coupling of S to A allows the magnet to leave its initial paramagnetic state and go to the thermodynamically stable state with magnetization upwards or downwards in the z-direction, which can then be read off.

The interpretation of quantum mechanics ensuing from these models is that the density matrix describes our best knowledge about the ensemble of identically prepared systems. The truncation of the density matrix (disappearance of Schrödinger cat terms) is a dynamical effect, while the Born rule follows in the case of an ideal experiment from the dynamical conservation of the tested operator. A quantum measurement consists of a large set of measurement runs on a large set of identically prepared systems. Reading off the pointer of the apparatus (the final upward or downward magnetization) allows for selecting the measurement outcomes and to update the predictions for future experimentation.

The insight that quantum mechanics must be only considered in its laboratory context was stressed in particular by Bohr, see Max Jammer [27], and is central in the approach of Auffèves and Grangier [28,29]. Their contexts–systems–modalities (CSM) approach is complementary to our model based approach. However, the latter proves rather than postulates the working of the setup and, among others, provides specifications for the (model) experiment to be close enough to ideal.

The aim of the present paper is to present Hamiltonians for the measurement of of a higher spin like . To have an unbiased apparatus, M must have a invariance for measuring any of the eigenvalues of , to be denoted as . This is achieved by starting from cosines of the spins of M, while they allow a simplified connection to low moments of these spins. The manifest invariance in the cosine-formulation leads to a linear map between the moments.

In Section 2, we propose the formulation for the Hamiltonian of M for general spin-l. In Section 3, we verify that, for spin-, this leads to the known Curie–Weiss model. In Section 4, we consider the thermodynamics of the spin-1 situation in detail. In Section 5, we investigate the thermodynamics for spins , 2 and . We close with a summary in Section 6.

2. General Spin

We aim to measure the z-component of an arbitrary quantum spin-l with (). The eigenvalues s of the operator (we indicate operators by a hat) lie in the spectrum (To simplify the notation, we replace the standard notation for spins by and . For an angular momentum , the model also applies to the measurement of with eigenvalues . We employ units ).

The measurement will be performed by employing an apparatus with vector spins-l denoted by , . . They have components , , which are coupled to a thermal harmonic oscillator bath; for the case , this was worked out [2,17]. The generalization of such a bath for arbitrary spin-l is straightforward and will be applied to the spin-1 model in future work.

The eigenvalues of each lie also in the spectrum (1). Since the present work only considers these z-components, we can discard the operator nature and only deal with the eigenvalues, which are integer or half-integer numbers.

In order to have an unbiased apparatus, the Hamiltonian of the magnet should have maximal symmetry and degenerate minima. To construct such a functional, we consider the spin–spin form

The expression in the middle is manifestly invariant under the shift of all mod for any spec. is non-negative and lies between 0 for the paramagnet, and 1 for each of the ferromagnetic states where all take one of the values of (1). Since the in (2) take the finite number of values, their cosines and sines can be expressed as polynomials of order in , which, summed over i, leads the spin-moments , , ⋯, , where

Let, out of the N spins , a number be in state , with and let be their fraction. The constraint implies . The moments read likewise

Inversion of these relations determines the as linear combinations of the . There is no simple general formula for this. In the next sections, we work out a number of low-l cases.

For the Hamiltonian , we shall follow [17] and adopt the spin–spin and four-spin terms

while multi-spin interaction terms such as can be added, but they will not change the overall picture. In a quantum approach, the and the will be operators; the Hamiltonian of the magnet M will be .

The degeneracy of this state is the multinomial coefficient

The entropy reads . With the Stirling formula, it follows that, for large N,

The thermodynamic free energy per magnet spin is

In order to use the magnet coupled to its bath as an apparatus for a quantum measurement, a coupling to the system S is needed. In the sector of Hilbert space where the tested quantum operator has the eigenvalue s, the system–apparatus interaction can likewise be taken as a sum of spin–spin couplings,

where g is the coupling constant. It will be seen that, for given l, it can be expressed as a linear combination of the moments , ⋯, .

When the coupling g is turned on, the total free energy per spin is . At low enough T, it has an absolute minimum when nearly all are equal to s. In a measurement setup, one considers quantum dynamics of the system, starting initially in the paramagnetic state and evolving to this absolute minimum. In the paramagnet, the spins are randomly oriented, so the fractions are equal. This leads to the moments

Clearly, the odd moments are zero. The relevant even moments are for ; for ; and for ; and, in the case , we finally consider and .

The quantum evolution leads the system from the paramagnet to the lowest free energy state characterized by s, undergoing a dynamical phase transition and ending with different parameters . In a measurement setup, the macroscopic order parameters can be read off, and the “measured” value of s can be deduced from them.

The invariance implies that expressions for , U, S, F, and are invariant under the simultaneous permutations mod and mod for all i. For any sequence , the numbers and the fractions are maintained. (An example for , : the sequence has and . Hence, and , while ). An equivalent method is to maintain while introducing . For , this gives

which, with , can be written as the linear map between s and the ,

When the results for are known for one of the s-values, the results for other cases can be obtained from that by applying this map times. Indeed, our starting point with the manifestly invariant cosines in Equations (2) and (9) has straightforwardly led to this invariance as a map between the moments . It assures that the apparatus has no bias for measuring any particular spec value.

3. Recap: The Spin- Curie–Weiss Model

We will work out the above models for low values of the spin. We set the stage by considering the spin- situation, a gentle reformulation of the original Curie–Weiss model for quantum measurement [17]. In units of ℏ, the z-component of a spin has the eigenvalues

which implies

The magnet has N such spins with each . According to (2), we consider the invariant

In terms of the moment,

which lies in the interval , equals, using (2) and (13) for each and summing,

for the paramagnetic state , while when all equal and .

From (5), the Hamiltonian is taken as pair and quartet interactions,

With for , we have from (4)

From (6) and (7), we obtain the standard result for the entropy at large N

In order to use the magnet coupled to its bath as an apparatus for a quantum measurement, a system–apparatus (SA) coupling is needed. It can be chosen as a spin–spin coupling,

where (13) was employed also for . The free energy per spin in the s-sector, , reads

In accordance with (11), it has the invariance required for an unbiased measurement. At low T, takes its lowest value for . This state is reached near the end of the measurement, after which the apparatus is decoupled from the system by setting . Equation (20) shows that an amount of energy has to be added to M for the decoupling. After a quick relaxation to the nearby thermodynamic minimum of the situation, the pointer, that is, the macroscopic magnetization , can be read off, the sign of which reveals the sought sign of s.

The map (11) reads here , so that the paramagnet is its stable point. This should be because it is the fully random state, which is statistically invariant under permutation.

All of this is a reformulation of the original spin- Curie–Weiss model [17], which involves the notation , , so that its lies between and . The couplings in (5) and g in (20) keep their values; for example, the interaction term in (20) lies for and between and g, as does in [17]. This occurs by construction, since in the definitions (14) and (20), one has to adjust the arguments of the cosines, not their values.

4. The Spin-1 Curie–Weiss Model

We now work out similar steps in the model of Section 2 for spin 1 and analyze the thermodynamics.

4.1. Formulation of the Model

A spin-1 has discrete z-components . Since and for , the three values of the cosine and sine can be expressed as quadratic or linear polynomials in s,

Using this with and summing over i leads to introducing the moments

Let denote the number of spins with for . In terms of the fractions , it holds that

Their inversion reads

For these to be nonnegative, the physical values are limited to

The actual values of are found as follows from (23). When all , . When one , and , where ; when two of the are , and or 0; when 3 are , and or , and so on. Thus, ranges from 0 to 1 with steps of , while ranges from to with steps of .

To construct the energy, we consider the invariant of the spins of the magnet

Expanding the cosine, employing (22) for the and summing yields a polynomial in the moments ,

For the Hamiltonian, we take as in (5)

The degeneracy of states characterized by is the multinomial

Equation (7) yields the explicit result for the entropy per spin at large N,

The symmetry of these quantities can be expressed by considering the permutation (11),

as can be verified in the special case in the second alinea after Equation (10). It follows that is unchanged. As expected, the weights (25) are permuted,

so that U, S and F are invariant, as required for unbiased measurement, and implying that the minima of F are degenerate; see Figure 1. (Due to (6), is invariant at any finite N). Making the shift mod 3 a second time, or the inverse shift mod 3, leads (32) to

Inserting (32) in the right-hand side of leads to , the identity map, as it should.

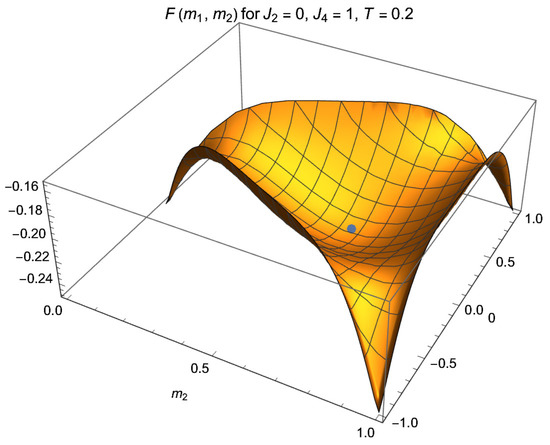

Figure 1.

The free energy F of the spin-1 magnet with , at below . The physical parameter range is . The paramagnetic state at (), indicated by the dot, is metastable with ; the three minima near the edges are degenerate and stable. The left one is located at , , where thermal effects make and lie below the edge value . Two other minima lie at the symmetry points , and , . In this setting, the magnet can be employed for quantum measurement. In the final state, one reads off , which is close to 0 or , and , which is close to 0 or N, well separated from the initial paramagnetic values , .

The thermodynamic free energy is

The ferromagnetic states and , have and . The paramagnet (, ) has energy zero and maximal entropy per spin, .

For T low enough, one can use the model as a measuring apparatus that starts in the metastable paramagnetic state and ends up in one of the three degenerate stable states. To measure the z-component of a spin-1, we assume that the tested spin S has a spin–spin coupling with all spins of the apparatus. For the SA coupling (9), we obtain, using (22) for s and the ,

It is invariant for mod 3 and likewise for the , the latter being equivalent to as given in (32), which, with the invariance of and , assures absence of bias in the measurement.

4.2. The Paramagnetic State

The paramagnetic state has , . It is invariant under the map (32), as expected, since it refers to the completely random state. One may verify the total weight of this state for large N in the Stirling approximation, which leads to small Gaussian deviations and ,

Expansion brings likewise , which yields

At high T, the paramagnetic state is the only stable state. At lower T, it remains locally stable for ; in the case of , it is locally stable at all T. In the measurement setup, this local stability is required to let the apparatus lie in the metastable paramagnetic state (“ready state”) until the measurement is started.

4.3. The Equilibrium States of the Magnet

The free energy is given by (28) and (35). For the case , and , it is depicted in Figure 1. It has three minima, of which one occurs at and small . At , one has

Its mean field equation reads

The paramagnetic state having and is the only stable state at high T. In case , there appears a metastable (ms) state , when develops a solution at

Below the critical temperature , this state attains the absolute minimum of the free energy,

Let, for general , F has an absolute minimum at and small ; for as in Figure 1, . The symmetry ensures that this minimum is degenerate with the pair of minima at the symmetry points and . With being small, the minima lie close to the edge values , and , respectively, where the magnet is polarized with nearly all equal and , respectively.

When , it may be negative, but is needed for the minimum at to have a lower free energy than the paramagnet and thus be the absolute minimum.

4.4. The Thermodynamic Equilibrium State of M Coupled to S

The total free energy per particle has an absolute minimum for each s, which is most easily analyzed for low T. For , it is optimal to have , , which occurs when nearly all are 0; for , it is optimal to have , , which occurs at low T when nearly all are equal to s. This correlation between the apparatus spins and tested spin s allows for employing the setup as an apparatus that measures s by reading off the macroscopic order parameters of the magnet. Hereto, one sets g from 0 to a large enough positive value at an initial time of the measurement and puts it back to zero near the final time . In the first stage, the magnet goes at given s to the state with lowest ; after cutting g, there occurs a small rearrangement to the nearby stable state of F. Then, the macroscopic order parameters can be read off, which determine s.

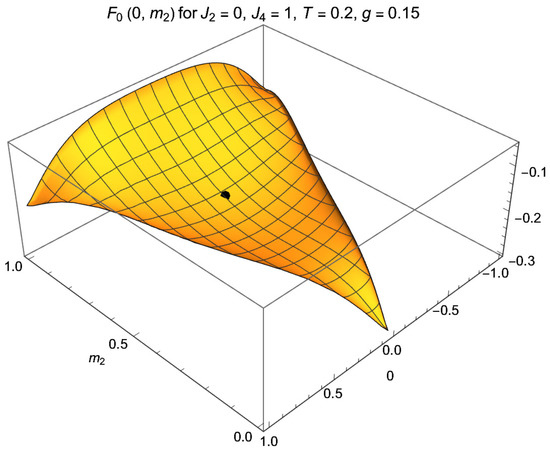

At large enough g and proper low T, has one absolute minimum for each s; see Figure 2 for the case . It suffices to know for one of the cases, say . The profiles for read, in the notations of (32) and (34), and .

Figure 2.

The free energy of the spin-1 magnet with , at coupled to the spin-1 with strength in the sector . The coupling acts as a magnetic field, leading the magnet from its initial paramagnetic state at (), indicated by the dot, to the absolute minimum of at and small . For , is related by the maps (32), (34), viz. and .

The free energy at is relevant in the case . With the SA interaction included, it reads

Its mean field Equation (40) now includes g,

The paramagnet is not a solution at . When and , a coupling is needed to suppress the barrier around between the paramagnetic and state, so that the ferromagnetic pointer state can be reached dynamically by “sliding off the hill”.

For small T, which can be used when is small or negative but , is exponentially small,

The free energy, equal to

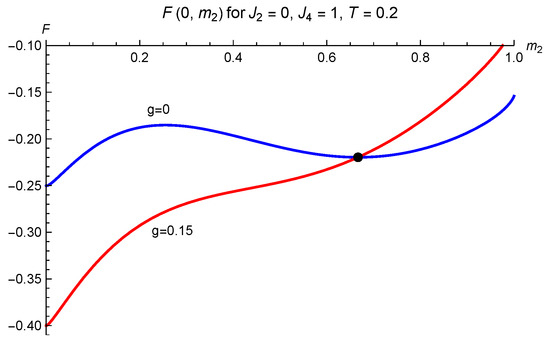

lies slightly below the corner value at and well below the paramagnetic . The free energy for the case is plotted in Figure 1 as a function of . For it is plotted as function of in Figure 3, both for and .

Figure 3.

The free energy of the spin 1 magnet with parameters as in Figure 1 and Figure 2: , at , (not) coupled to a spin 1 with strength in the sector . The coupling acts as a magnetic field, leading the magnet from its initial paramagnetic state indicated by the dot, to the absolute minimum at and small .

The stability of a extremal state with and finite is set by

while . For small T, one has , so these are approximately equal to , making this point is stable. There are two related stable points: The minimum of F at , is degenerate with , . In all cases, and .

4.5. Spin 1 Effectively Behaving as Spin

If , the value shows that states are empty, so that only the states participate, effectively a spin system. This can be achieved by a strong repulsive magnetic field in the 0-direction, expressed by the Hamiltonian with .

4.6. An Apparatus That Measures Only Two Values of of a Spin 1

Suppose that we couple the spin S to an apparatus with spins , which have and . Let the interaction Hamiltonian not be set by (36) but by

In each sector , the first term is a constant that can be dropped. For , registration takes place as in the spin- CW model of Section 2, where the sign of the final total magnetization is set by the sign of s. In the sector , there is no coupling between system and apparatus, hence no dynamics takes place: the apparatus does not act; not even a truncation of the density matrix occurs.

Setting in Equation (48) brings a model for measuring only the and values of , while leads to a model for measuring and .

5. Higher Spin Models

Proceeding in a similar way as for spin and 1, we consider the cases of spin , 2 and .

5.1. Spin 3/2

The z-component of a spin can take the values

This implies

which may be expressed by the at most cubic polynomials

The magnet has N such spins . We consider the invariant

Expression in the magnetic moments takes the form

with the standard definitions

when all equal any of the s values, in which , as it should.

In the paramagnet, one has random , each taking one of the s values with probability ,

The multinomial

leads for large N to the entropy per particle

The spin moments are

Inversion of the expressions brings

They must all be nonnegative, which confines the allowable . This implies and . The combinations and impose , in accordance with its definition . The combinations and yield , while and yield .

In , the coupling to S is chosen as in (9),

Again, it leads to the lowest value , when for all for all four s-values in the spectrum (49). Due to thermal effects, the optimal will slightly deviate from these values.

The paramagnetic state (55) is invariant under the map, as it should for the completely random state.

5.2. Spin 2

The z-component of a spin 2 takes one of the values

It is handy to define

which arise from the properties

From Equation (2), it follows that

In the paramagnet, one has random , so that

which amounts to , , , confirming that vanishes. The moments read

The follow as

and fix the entropy by (7). The ferromagnetic state indeed has and . The possible values of follow from , which make the nonnegative.

The SA coupling (9) reads explicitly

5.3. Spin

Finally, we consider , where

Here, we define

which are introduced to satisfy

This leads to

and, from (9),

The entropy per spin reads at large N

The weights take the form

They must be nonnegative, which sets the physical ranges of the , next to for and for from their definitions .

6. Summary

Interpretation of quantum mechanics should be based on its touchstone with reality, that is, on the action of an idealized apparatus that performs a large set of measurements on a large set of identically prepared systems. For measurement of the z-component of spins-, a rich enough model was formulated, the Curie–Weiss model for quantum measurement [17], where the apparatus consists of an Ising magnet M having itself spins-, coupled to thermal harmonic oscillator bath. Details of the dynamical solution were summarized and further worked out in “Opus” [2]. In order to have an unbiased measurement, it is required that the Hamiltonian is symmetric under reversal of all spins of M, and that the interaction Hamiltonian is symmetric under their reversal and reversal of the tested spin.

The purpose of this paper is to construct models to measure the z-component of a quantum spin or angular momentum , which takes the values . In order to have an unbiased setup, a invariance is required. This is achieved by starting from cosines and sines of , for the tested spin and the N spins of the magnet, which are manifestly invariant under the shift mod . Shapes for the energy functional and the interaction energy are proposed, which are invariant under the shift, and so is the corresponding entropy. Since s takes discrete values, the cosines and sines can be expressed in powers , . For the magnet, each of them leads to an order parameter, the first being the magnetization. The symmetry now gets coded in a linear map between the order parameters. The general form of the Hamiltonian, the free energy, and the map is worked out for spin , 1, , 2 and . For the spin 1-case, the thermodynamics are discussed in detail.

To deal with the measurement dynamics, the components of each quantum spin of the magnet can be coupled to a harmonic oscillator bath such as in the spin- case, which yields the dynamical equations in the early truncation and the subsequent registration periods. This subject is presently under study.

In conclusion, the purpose of this work was to support the previous ABN works for interpretation of quantum mechanics based on the dynamics of quantum measurement of a spin . This goal is achieved by constructing models for spin 1 and larger that can likewise be investigated dynamically. Since it is clear from the ABN works that the measurement dynamics is set by its thermodynamics, it can already be expected that the new models will exhibit similar dynamics. We have demonstrated that the thermodynamics of the new models are similar in structure to the spin case, be it at the cost of additional order parameters. The agreement in structure and thermodynamics between the well documented spin model for quantum measurement and the present models for larger spin support the ABN interpretation of quantum mechanics that was put forward previously.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wheeler, J.A.; Zurek, W.H. Quantum Theory and Measurement; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. Understanding quantum measurement from the solution of dynamical models. Phys. Rep. 2013, 525, 1–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, K. Quantum theory of measurement and macroscopic variables. Helv. Phys. Acta 1972, 45, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.S. On wave packet reduction in the Coleman–Hepp model. In John S Bell On The Foundations Of Quantum Mechanics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2001; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gaveau, B.; Schulman, L. Model apparatus for quantum measurements. J. Stat. Phys. 1990, 58, 1209–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haake, F.; Walls, D.F. Overdamped and amplifying meters in the quantum theory of measurement. Phys. Rev. A 1987, 36, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haake, F.; Żukowski, M. Classical motion of meter variables in the quantum theory of measurement. Phys. Rev. A 1993, 47, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. Quantum measurement as a driven phase transition: An exactly solvable model. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 032108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeh, H.D. On the interpretation of measurement in quantum theory. Found. Phys. 1970, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosshauer, M. Decoherence, the measurement problem, and interpretations of quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005, 76, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Neumann, J. Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 38. [Google Scholar]

- Von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics: New Edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Everett III, H. “Relative state” formulation of quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1957, 29, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, B.S. Quantum mechanics and reality. Phys. Today 1970, 23, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, B.S. The many-universes interpretation of quantum mechanics. In The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 167–218. [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. Curie–Weiss model of the quantum measurement process. EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 2003, 61, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdyan, A.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. The quantum measurement process: An exactly solvable model. arXiv 2003, arXiv:cond-mat/0309188, 719. [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. The quantum measurement process in an exactly solvable model. In AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics: College Park, MD, USA, 2005; Volume 750, pp. 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. Dynamics of a quantum measurement. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2005, 29, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. The Quantum Measurement Process: Lessons from an exactly solvable model. In Beyond the Quantum; WorldScientific: Singapore, 2007; pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. Phase transitions and quantum measurements. In AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics: College Park, MD, USA, 2006; Volume 810, pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuizen, T.M.; Perarnau-Llobet, M.; Balian, R. Lectures on dynamical models for quantum measurements. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2014, 28, 1430014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. A sub-ensemble theory of ideal quantum measurement processes. Ann. Phys. 2017, 376, 324–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. Teaching quantum measurement: From dynamics to interpretation; Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Donker, H.; De Raedt, H.; Katsnelson, M. Quantum dynamics of a small symmetry breaking measurement device. Ann. Phys. 2018, 396, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammer, M. The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Auffèves, A.; Grangier, P. Contexts, systems and modalities: A new ontology for quantum mechanics. Found. Phys. 2016, 46, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffèves, A.; Grangier, P. Deriving Born’s rule from an Inference to the Best Explanation. Found. Phys. 2020, 50, 1781–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).