Abstract

This paper is focused on the derivation of data-processing and majorization inequalities for f-divergences, and their applications in information theory and statistics. For the accessibility of the material, the main results are first introduced without proofs, followed by exemplifications of the theorems with further related analytical results, interpretations, and information-theoretic applications. One application refers to the performance analysis of list decoding with either fixed or variable list sizes; some earlier bounds on the list decoding error probability are reproduced in a unified way, and new bounds are obtained and exemplified numerically. Another application is related to a study of the quality of approximating a probability mass function, induced by the leaves of a Tunstall tree, by an equiprobable distribution. The compression rates of finite-length Tunstall codes are further analyzed for asserting their closeness to the Shannon entropy of a memoryless and stationary discrete source. Almost all the analysis is relegated to the appendices, which form the major part of this manuscript.

1. Introduction

Divergences are non-negative measures of dissimilarity between pairs of probability measures which are defined on the same measurable space. They play a key role in the development of information theory, probability theory, statistics, learning, signal processing, and other related fields. One important class of divergence measures is defined by means of convex functions f, and it is called the class of f-divergences. It unifies fundamental and independently-introduced concepts in several branches of mathematics such as the chi-squared test for the goodness of fit in statistics, the total variation distance in functional analysis, the relative entropy in information theory and statistics, and it is closely related to the Rényi divergence which generalizes the relative entropy. The class of f-divergences was introduced in the sixties by Ali and Silvey [1], Csiszár [2,3,4,5,6], and Morimoto [7]. This class satisfies pleasing features such as the data-processing inequality, convexity, continuity and duality properties, finding interesting applications in information theory and statistics (see, e.g., [4,6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]).

This manuscript is a research paper which is focused on the derivation of data-processing and majorization inequalities for f-divergences, and a study of some of their potential applications in information theory and statistics. Preliminaries are next provided.

1.1. Preliminaries and Related Works

We provide here definitions and known results from the literature which serve as a background to the presentation in this paper. We first provide a definition for the family of f-divergences.

Definition 1

([16], p. 4398). Let P and Q be probability measures, let μ be a dominating measure of P and Q (i.e., ), and let and . The f-divergence from P to Q is given, independently of μ, by

where

Definition 2.

Let be a probability distribution which is defined on a set , and that is not a point mass, and let be a stochastic transformation. The contraction coefficient for f-divergences is defined as

where, for all ,

The notation in (6) and (7), and also in (20), (21), (42), (43), (44) in the continuation of this paper, is consistent with the standard notation used in information theory (see, e.g., the first displayed equation after (3.2) in [17]).

Contraction coefficients for f-divergences play a key role in strong data-processing inequalities (see [18,19,20], ([21], Chapter II), [22,23,24,25,26]). The following are essential definitions and results which are related to maximal correlation and strong data-processing inequalities.

Definition 3.

The maximal correlation between two random variables X and Y is defined as

where the supremum is taken over all real-valued functions f and g such that

Definition 4.

Pearson’s -divergence [27] from P to Q is defined to be the f-divergence from P to Q (see Definition 1) with or for all ,

independently of the dominating measure μ (i.e., , e.g., ).

Neyman’s -divergence [28] from P to Q is the Pearson’s -divergence from Q to P, i.e., it is equal to

with or for all .

Proposition 1

(([24], Theorem 3.2), [29]). The contraction coefficient for the -divergence satisfies

with and (see (7)).

Proposition 2

([25], Theorem 2). Let be convex and twice continuously differentiable with and . Then, for any that is not a point mass,

i.e., the contraction coefficient for the -divergence is the minimal contraction coefficient among all f-divergences with f satisfying the above conditions.

Remark 1.

The following result provides an upper bound on the contraction coefficient for a subclass of f-divergences in the finite alphabet setting.

Proposition 3

([26], Theorem 8). Let be a continuous convex function which is three times differentiable at unity with and , and let it further satisfy the following conditions:

- (a)

- (b)

- The function , given by for all , is concave.

Then, for a probability mass function supported over a finite set ,

For the presentation of our majorization inequalities for f-divergences and related entropy bounds (see Section 2.3), essential definitions and basic results are next provided (see, e.g., [30], ([31], Chapter 13) and ([32], Chapter 2)). Let P be a probability mass function defined on a finite set , let be the maximal mass of P, and let be the sum of the k largest masses of P for (hence, it follows that and ).

Definition 5.

Consider discrete probability mass functions P and Q defined on a finite set . It is said that P is majorized by Q (or Q majorizes P), and it is denoted by , if for all (recall that ).

A unit mass majorizes any other distribution; on the other hand, the equiprobable distribution on a finite set is majorized by any other distribution defined on the same set.

Definition 6.

Let denote the set of all the probability mass functions that are defined on . A function is said to be Schur-convex if for every such that , we have . Likewise, f is said to be Schur-concave if is Schur-convex, i.e., and imply that .

Characterization of Schur-convex functions is provided, e.g., in ([30], Chapter 3). For example, there exist some connections between convexity and Schur-convexity (see, e.g., ([30], Section 3.C) and ([32], Chapter 2.3)). However, a Schur-convex function is not necessarily convex ([32], Example 2.3.15).

Finally, what is the connection between data processing and majorization, and why these types of inequalities are both considered in the same manuscript? This connection is provided in the following fundamental well-known result (see, e.g., ([32], Theorem 2.1.10), ([30], Theorem B.2) and ([31], Chapter 13)):

Proposition 4.

Let P and Q be probability mass functions defined on a finite set . Then, if and only if there exists a doubly-stochastic transformation (i.e., for all , and for all with ) such that . In other words, if and only if in their representation as column vectors, there exists a doubly-stochastic matrix (i.e., a square matrix with non-negative entries such that the sum of each column or each row in is equal to 1) such that .

1.2. Contributions

This paper is focused on the derivation of data-processing and majorization inequalities for f-divergences, and it applies these inequalities to information theory and statistics.

The starting point for obtaining strong data-processing inequalities in this paper relies on the derivation of lower and upper bounds on the difference where and denote, respectively, pairs of input and output probability distributions with a given stochastic transformation (i.e., where and ). These bounds are expressed in terms of the respective difference in the Pearson’s or Neyman’s -divergence, and they hold for all f-divergences (see Theorems 1 and 2). By a different approach, we derive an upper bound on the contraction coefficient for f-divergences of a certain type, which gives an alternative strong data-processing inequality for the considered type of f-divergences (see Theorems 3 and 4). In this framework, a parametric subclass of f-divergences is introduced, its interesting properties are studied (see Theorem 5), all the data-processing inequalities which are derived in this paper are applied to this subclass, and these inequalities are exemplified numerically to examine their tightness (see Section 3.1).

This paper also derives majorization inequalities for f-divergences where part of these inequalities rely on the earlier data-processing inequalities (see Theorem 6). A different approach, which relies on the concept of majorization, serves to derive tight bounds on the maximal value of an f-divergence from a probability mass function P to an equiprobable distribution; the maximization is carried over all P with a fixed finite support where the ratio of their maximal to minimal probability masses does not exceed a given value (see Theorem 7). These bounds lead to accurate asymptotic results which apply to general f-divergences, and they strengthen and generalize recent results of this type with respect to the relative entropy [33], and the Rényi divergence [34]. Furthermore, we explore in Theorem 7 the convergence rates to the asymptotic results. Data-processing and majorization inequalities also serve to strengthen the Schur-concavity property of the Tsallis entropy (see Theorem 8), showing by a comparison to earlier bounds in [35,36] that none of these bounds is superseded by the other. Further analytical results which are related to the specialization of our central result on majorization inequalities in Theorem 7, applied to several important sub-classes of f-divergences, are provided in Section 3.2 (including Theorem 9). A quantity which is involved in our majorization inequalities in Theorem 7 is interpreted by relying on a variational representation of f-divergences (see Theorem 10).

As an application of the data-processing inequalities for f-divergences, the setup of list decoding is further studied, reproducing in a unified way some known bounds on the list decoding error probability, and deriving new bounds for fixed and variable list sizes (see Theorems 11–13).

As an application of the majorization inequalities in this paper, we study properties of a measure which is used to quantify the quality of approximating probability mass functions, induced by the leaves of a Tunstall tree, by an equiprobable distribution (see Theorem 14). An application of majorization inequalities for the relative entropy is used to derive a sufficient condition, expressed in terms of the principal and secondary real branches of the Lambert W function [37], for asserting the proximity of compression rates of finite-length (lossless and variable-to-fixed) Tunstall codes to the Shannon entropy of a memoryless and stationary discrete source (see Theorem 15).

1.3. Paper Organization

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides our main new results on data-processing and majorization inequalities for f-divergences and related entropy measures. Illustration of the theorems in Section 2, and further mathematical results which follow from these theorems are introduced in Section 3. Applications in information theory and statistics are considered in Section 4. Proofs of all theorems are relegated to the appendices, which form a major part of this paper.

2. Main Results on f-Divergences

This section provides strong data-processing inequalities for f-divergences (see Section 2.1), followed by a study of a new subclass of f-divergences (see Section 2.2) which later serves to exemplify our data-processing inequalities. The third part of this section (see Section 2.3) provides majorization inequalities for f-divergences, and for the Tsallis entropy, whose derivation relies in part on the new data-processing inequalities.

2.1. Data-Processing Inequalities for f-Divergences

Strong data-processing inequalities are provided in the following, bounding the difference and ratio where and denote, respectively, pairs of input and output probability distributions with a given stochastic transformation.

Theorem 1.

Let and be finite or countably infinite sets, let and be probability mass functions that are supported on , and let

Let be a stochastic transformation such that for every , there exists with , and let (see (6) and (7))

Furthermore, let be a convex function with , and let the non-negative constant satisfy

where denotes the right-side derivative of f, and

Then,

- (a)

- (b)

- If f is twice differentiable on , then the largest possible coefficient in the right side of (22) is given by

- (c)

- (d)

- Under the assumption in Item (b), ifthen,

- (e)

- The lower and upper bounds in (24), (27), (32) and (33) are locally tight. More precisely, let be a sequence of probability mass functions defined on and pointwise converging to which is supported on , and let and be the probability mass functions defined on via (20) and (21) with inputs and , respectively. Suppose thatIf f has a continuous second derivative at unity, thenand these limits indicate the local tightness of the lower and upper bounds in Items (a)–(d).

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

An application of Theorem 1 gives the following result.

Theorem 2.

Let and be finite or countably infinite sets, let , and let and be random vectors taking values on and , respectively. Let and be the probability mass functions of discrete memoryless sources where, for all ,

with and supported on for all . Let each symbol be independently selected from one of the source outputs at time instant i with probabilities λ and , respectively, and let it be transmitted over a discrete memoryless channel with transition probabilities

Let be the probability mass function of the symbols at the channel input, i.e.,

let

and let be a convex and twice differentiable function with . Then,

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- If f has a continuous second derivative at unity, and for all , then

Proof.

See Appendix B. □

Remark 2.

In continuation to ([26], Theorem 8) (see Proposition 3 in Section 1.1), we next provide an upper bound on the contraction coefficient for a subclass of f-divergences (this subclass is different from the one which is addressed in ([26], Theorem 8)). Although the first part of the next result is stated for finite or countably infinite alphabets, it is clear from its proof that it also holds in the general alphabet setting. Connections to the literature are provided in Remarks A1–A3.

Theorem 3.

Let be a function which satisfies the following conditions:

- f is convex, differentiable at 1, , and ;

- The function , defined for all by , is convex.

Let and be non-identical probability mass functions which are defined on a finite or a countably infinite set , and let

where and are given in (18) and (19). Then, in the setting of (20) and (21),

Consequently, if is finitely supported on ,

Proof.

See Appendix C.1. □

Similarly to the extension of Theorem 1 to Theorem 2, a similar extension of Theorem 3 leads to the following result.

Theorem 4.

Proof.

See Appendix C.2. □

2.2. A Subclass of f-Divergences

A subclass of f-divergences with interesting properties is introduced in Theorem 5. The data-processing inequalities in Theorems 2 and 4 are applied to these f-divergences in Section 3.

Theorem 5.

Let be given by

for all . Then,

- (a)

- is an f-divergence which is monotonically increasing and concave in α, and its first three derivatives are related to the relative entropy and -divergence as follows:

- (b)

- (c)

- where the function is defined aswhich is monotonically increasing in α, satisfying for all , and it tends to infinity as we let . Consequently, unless ,

- (d)

- (e)

- For every and a pair of probability mass functions where , there exists such that for all

- (f)

- If a sequence of probability measures converges to a probability measure Q such thatwhere for all sufficiently large n, then

- (g)

- If , then

- (h)

Proof.

See Appendix D. □

2.3. f-Divergence Inequalities via Majorization

Let denote an equiprobable probability mass function on for an arbitrary , i.e., for all . By majorization theory and Theorem 1, the next result strengthens the Schur-convexity property of the f-divergence (see ([38], Lemma 1)).

Theorem 6.

Let P and Q be probability mass functions which are supported on , and suppose that . Let be twice differentiable and convex with , and let and be, respectively, the maximal and minimal positive masses of Q. Then,

Proof.

See Appendix E. □

The next result provides upper and lower bounds on f-divergences from any probability mass function to an equiprobable distribution. It relies on majorization theory, and it follows in part from Theorem 6.

Theorem 7.

Let denote the set of all the probability mass functions that are defined on . For , let be the set of all which are supported on with , and let be a convex function with . Then,

- (a)

- The set , for any , is a non-empty, convex and compact set.

- (b)

- For a given , which is supported on , the f-divergences and attain their maximal values over the set .

- (c)

- For and an integer , letletand let the probability mass function be defined on the set as follows:whereThen,

- (d)

- For and an integer , let the non-negative function be given by

- (e)

- (f)

- (g)

- Let , and let be an integer. Then,Furthermore, if , f is differentiable on , and , then, for every ,

- (h)

- For , let the function f be also twice differentiable, and let M and m be constants such that the following condition holds:

- (i)

- Let . If for all , then for all , if

Proof.

See Appendix F. □

Tsallis entropy was introduced in [39] as a generalization of the Shannon entropy (similarly to the Rényi entropy [40]), and it was applied to statistical physics in [39].

Definition 7

([39]). Let be a probability mass function defined on a discrete set . The Tsallis entropy of order of X, denoted by or , is defined as

where . The Tsallis entropy is continuously extended at orders 0, 1, and ∞; at order 1, it coincides with the Shannon entropy on base (expressed in nats).

Theorem 6 enables to strengthen the Schur-concavity property of the Tsallis entropy (see ([30], Theorem 13.F.3.a.)) as follows.

Theorem 8.

Let P and Q be probability mass functions which are supported on a finite set, and let . Then, for all ,

Proof.

See Appendix G. □

Remark 4.

The lower bound in ([36], Theorem 1) also strengthens the Schur-concavity property of the Tsallis entropy. It can be verified that none of the lower bounds in ([36], Theorem 1) and Theorem 8 supersedes the other. For example, let , and let and be probability mass functions supported on with and where and . This yields . From (A233) (see Appendix G),

If , then , and the continuous extension of the lower bound in ([36], Theorem 1) at is specialized to the earlier result by the same authors in ([35], Theorem 3); it states that if , then . In contrast to (104), it can be verified that

which can be made arbitrarily large by selecting β to be sufficiently close to 1 (from above). This provides a case where the lower bound in Theorem 8 outperforms the one in ([35], Theorem 3).

Remark 5.

Due to the one-to-one correspondence between Tsallis and Rényi entropies of the same positive order, similar to the transition from ([36], Theorem 1) to ([36], Theorem 2), also Theorem 8 enables to strengthen the Schur-concavity property of the Rényi entropy. For information-theoretic implications of the Schur-concavity of the Rényi entropy, the reader is referred to, e.g., [34], ([41], Theorem 3) and ([42], Theorem 11).

3. Illustration of the Main Results and Implications

3.1. Illustration of Theorems 2 and 4

We apply here the data-processing inequalities in Theorems 2 and 4 to the new class of f-divergences introduced in Theorem 5.

In the setup of Theorems 2 and 4, consider communication over a time-varying binary-symmetric channel (BSC). Consequently, let , and let

with and for every . Let the transition probabilities correspond to (i.e., a BSC with a crossover probability ), i.e.,

For all and , the probability mass function at the channel input is given by

with

where the probability mass function in (109) refers to a Bernoulli distribution with parameter . At the output of the time-varying BSC (see (42)–(44) and (107)), for all ,

where

with

The -divergence from to is given by

and since the probability mass functions , , and correspond to Bernoulli distributions with parameters , , and , respectively, Theorem 2 gives that

for all and . From (26), (31) and (55), we get that for all ,

and, from (47), (48) and (106), for all ,

provided that for some (otherwise, both f-divergences in the right side of (116) are equal to zero since and therefore for all i and ). Furthermore, from Item (c) of Theorem 2, for every and ,

and the lower and upper bounds in the left side of (116) and the right side of (117), respectively, are tight as we let , and they both coincide with the limit in the right side of (124).

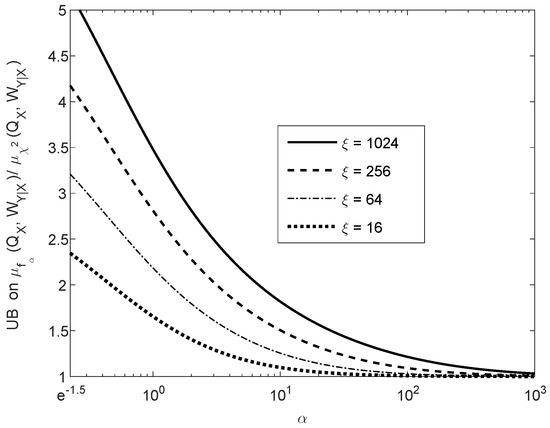

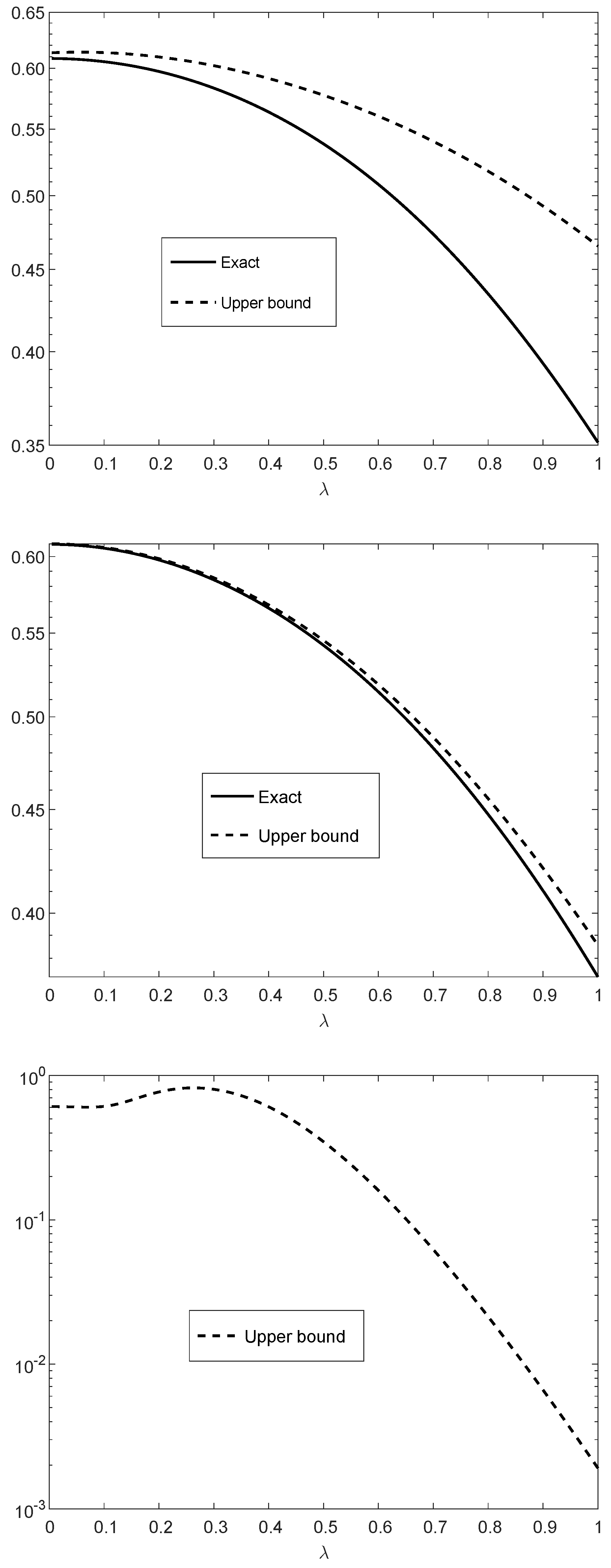

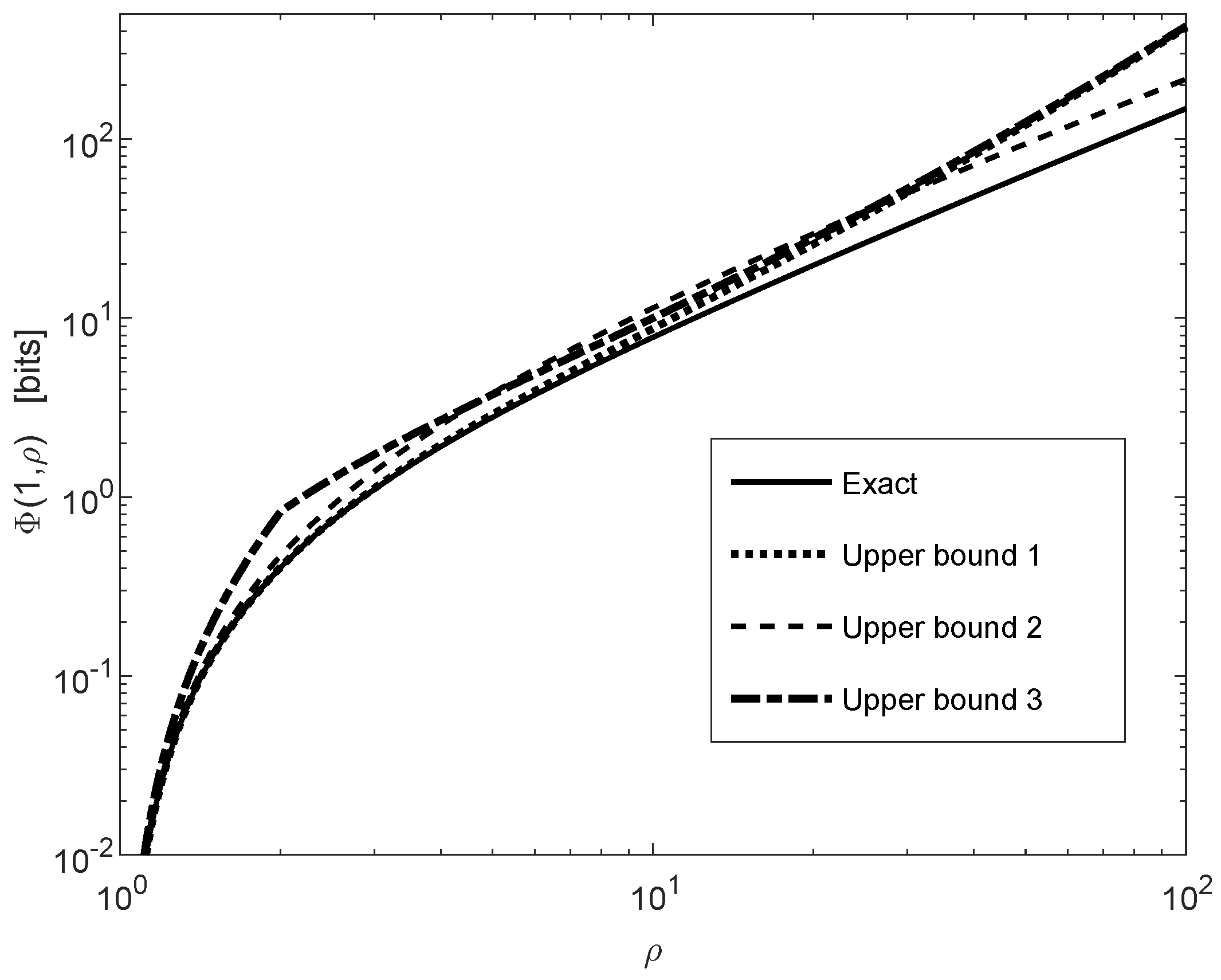

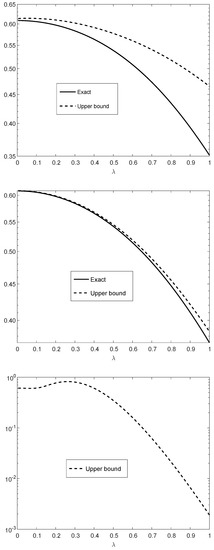

Figure 1 illustrates the upper and lower bounds in (116) and (117) with , , and for all i, and . In the special case where are fixed for all i, the communication channel is a time-invariant BSC whose capacity is equal to bit per channel use.

Figure 1.

The bounds in Theorem 2 applied to (vertical axis) versus (horizontal axis). The -divergence refers to Theorem 5. The probability mass functions and correspond, respectively, to discrete memoryless sources emitting n i.i.d. and symbols; the symbols are transmitted over with . The bounds in the upper and middle plots are compared to the exact values, being computationally feasible for and , respectively. The upper, middle and lower plots correspond, respectively, to , , and .

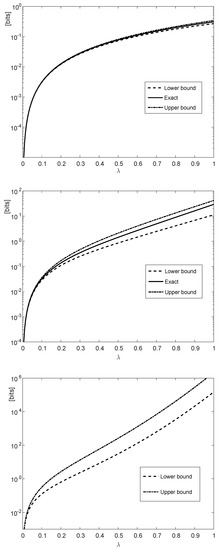

By referring to the upper and middle plots of Figure 1, if or , then the exact values of the differences of the -divergences in the right side of (116) are calculated numerically, being compared to the lower and upper bounds in the left side of (116) and the right side of (117) respectively. Since the -divergence does not tensorize, the computation of the exact value of each of the two -divergences in the right side of (116) involves a pre-computation of probabilities for each of the probability mass functions , , and ; this computation is prohibitively complex unless n is small enough.

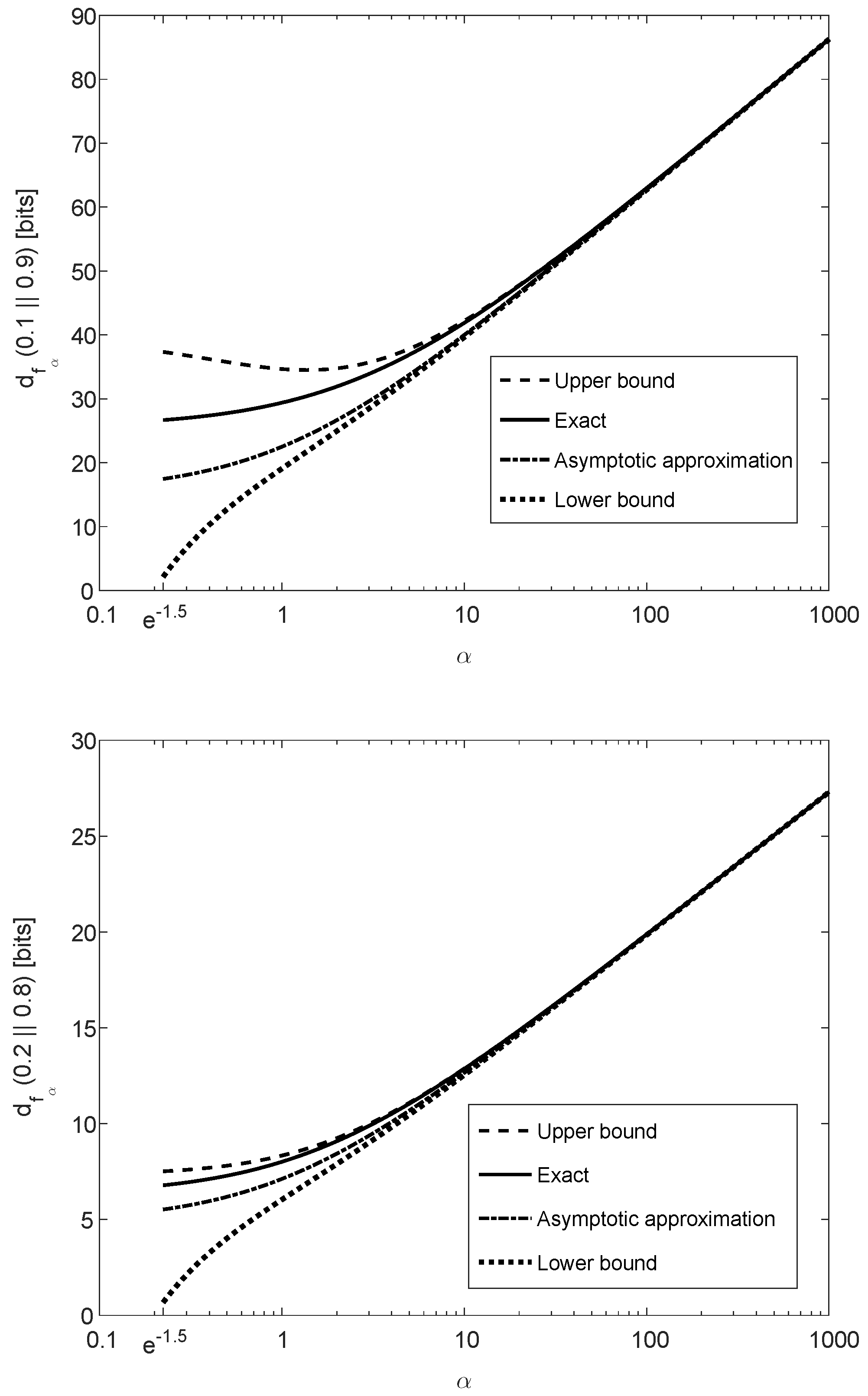

We now apply the bound in Theorem 4. In view of (51), (54), (55) and (73), for all and ,

where and are given in (122) and (123), respectively, and for ,

Figure 2 illustrates the upper bound on (see (125)–(127)) as a function of . It refers to the case where , , and for all i (similarly to Figure 1). The upper and middle plots correspond to with and , respectively; the middle and lower plots correspond to with and , respectively. The bounds in the upper and middle plots are compared to their exact values since their numerical computations are feasible for . It is observed from the numerical comparisons for (see the upper and middle plots in Figure 2) that the upper bounds are informative, especially for large values of where the -divergence becomes closer to a scaled version of the -divergence (see Item (e) in Theorem 5).

Figure 2.

The upper bound in Theorem 4 applied to (see (125)–(127)) in the vertical axis versus in the horizontal axis. The -divergence refers to Theorem 5. The probability mass functions and are and , respectively, for all with n uses of , and parameters . The upper and middle plots correspond to with and , respectively; the middle and lower plots correspond to with and , respectively. The bounds in the upper and middle plots are compared to the exact values, being computationally feasible for .

3.2. Illustration of Theorems 3 and 5

Following the application of the data-processing inequalities in Theorems 2 and 4 to a class of f-divergences (see Section 3.1), some interesting properties of this class are introduced in Theorem 5.

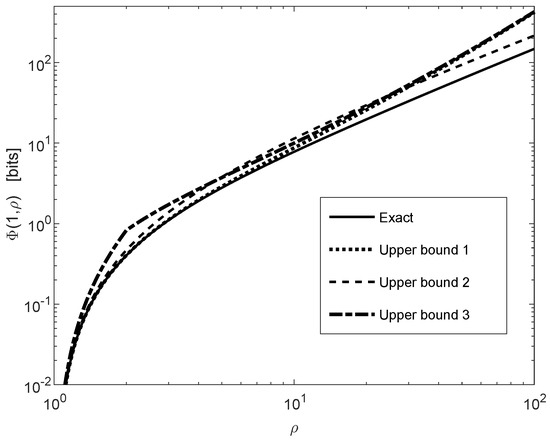

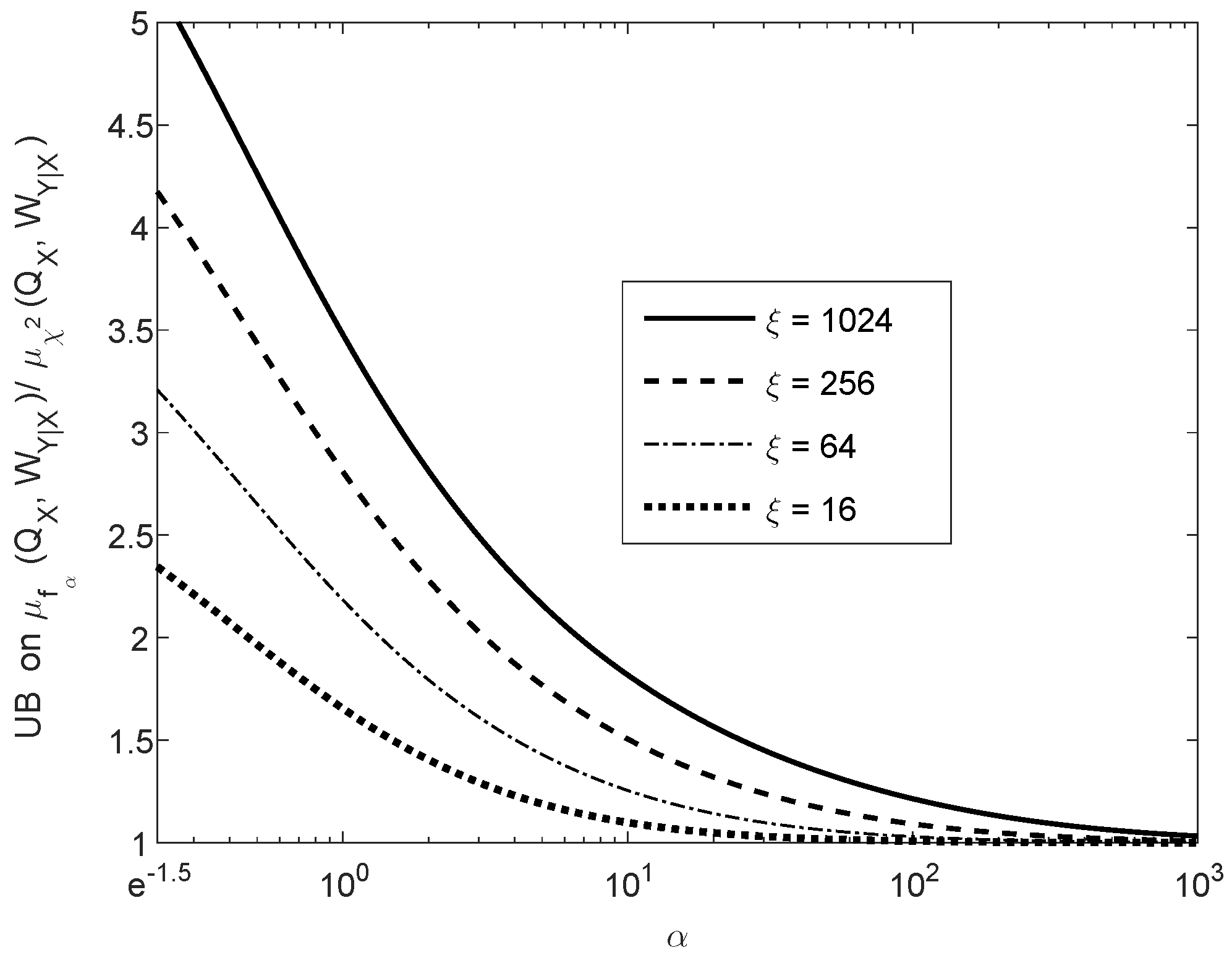

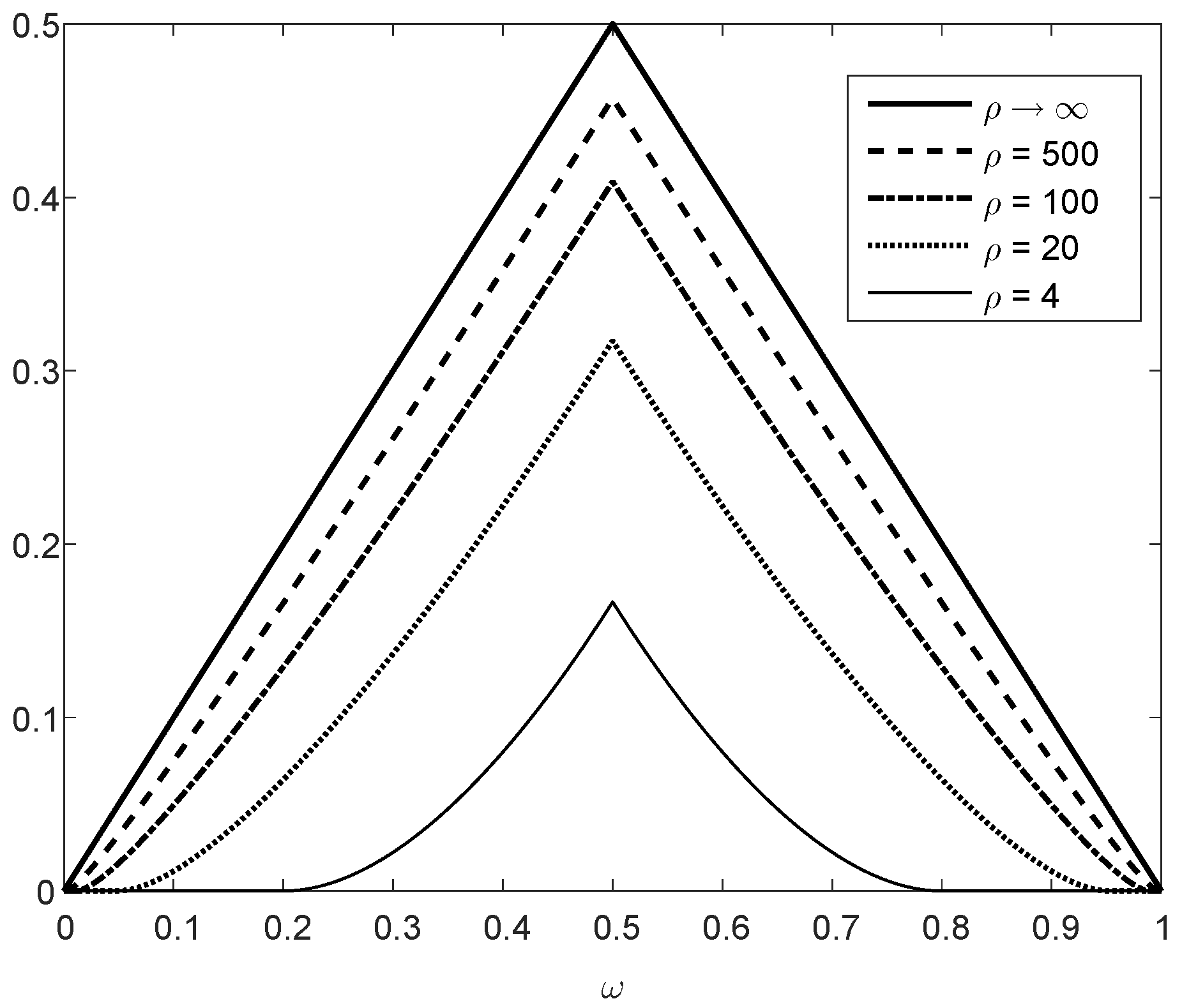

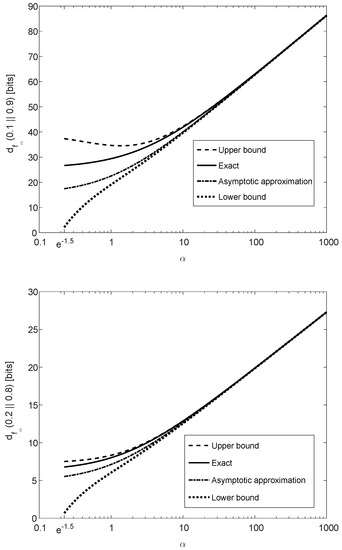

Theorem 5 is illustrated in Figure 3, showing that is monotonically increasing as a function of (note that the concavity in is not reflected from these plots because the horizontal axis of is in logarithmic scaling). The binary divergence is also compared in Figure 3 with its lower and upper bounds in (61) and (65), respectively, illustrating that these bounds are both asymptotically tight for large values of . The asymptotic approximation of for large , expressed as a function of and (see (66)), is also depicted in Figure 3. The upper and lower plots in Figure 3 refer, respectively, to and ; a comparison of these plots show a better match between the exact value of the binary divergence, its upper and lower bounds, and its asymptotic approximation when the values of p and q are getting closer.

In view of the results in (66) and (68), it is interesting to note that the asymptotic value of for large values of is also the exact scaling of this f-divergence for any finite value of when the probability mass functions P and Q are close enough to each other.

We next consider the ratio of the contraction coefficients where is finitely supported on and it is not a point mass (i.e., ), and is arbitrary. For all ,

where is given in (55), and

The left-side inequality in (130) is due to ([25], Theorem 2) (see Proposition 2), and the right-side inequality in (130) holds due to (53) and (73).

Figure 4 shows the upper bound on the ratio of contraction coefficients , as it is given in the right-side inequality of (130), as a function of the parameter . The curves in Figure 4 correspond to different values of , as it is given in (131); these upper bounds are monotonically decreasing in , and they asymptotically tend to 1 as we let . Hence, in view of the left-side inequality in (130), the upper bound on the ratio of the contraction coefficients (in the right-side inequality) is asymptotically tight in . The fact that the ratio of the contraction coefficients in the middle of (130) tends asymptotically to 1, as gets large, is not directly implied by Item (e) of Theorem 5. The latter implies that, for fixed probability mass functions P and Q and for sufficiently large ,

however, there is no guarantee that for fixed Q and sufficiently large , the approximation in (132) holds for all P. By the upper bound in the right side of (130), it follows however that tends asymptotically (as we let ) to the contraction coefficient of the divergence.

3.3. Illustration of Theorem 7 and Further Results

Theorem 7 provides upper and lower bounds on an f-divergence, , from any probability mass function Q supported on a finite set of cardinality n to an equiprobable distribution over this set. We apply in the following, the exact formula for

to several important f-divergences. From (87),

Since f is a convex function on with , Jensen’s inequality implies that the function which is subject to maximization in the right-side of (134) is non-negative over the interval . It is equal to zero at the endpoints of the interval , so the maximum over this interval is attained at an interior point. Note also that, in view of Items (d) and (e) of Theorem 7, the exact asymptotic expression in (134) satisfies

3.3.1. Total Variation Distance

By setting to zero the derivative of the function which is subject to maximization in the right side of (136), it can be verified that the maximizer over this interval is equal to , which implies that

3.3.2. Alpha Divergences

The class of Alpha divergences forms a parametric subclass of the f-divergences, which includes in particular the relative entropy, -divergence, and the squared-Hellinger distance. For , let

where is a non-negative and convex function with , which is defined for as follows (see ([8], Chapter 2), followed by studies in, e.g., [10,16,43,44,45]):

The functions and are defined in the right side of (139) by a continuous extension of at and , respectively. The following relations hold (see, e.g., ([44], (10)–(13))):

Setting to zero the derivative of the function which is subject to maximization in the right side of (147) gives

where it can be verified that for all and . Substituting (148) into the right side of (147) gives that, for all such and ,

By a continuous extension of in (149) at and , it follows that for all

Consequently, for all ,

where (151) holds due to (140); (152) is due to (146), and (153) holds due to (150). This sharpens the result in ([33], Theorem 2) for the relative entropy from the equiprobable distribution, , by showing that the bound in ([33], (7)) is asymptotically tight as we let . The result in ([33], Theorem 2) can be further tightened for finite n by applying the result in Theorem 7 (d) with for all (although, unlike the asymptotic result in (149), the refined bound for a finite n does not lend itself to a closed-form expression as a function of n; see also ([34], Remark 3), which provides such a refinement of the bound on for finite n in a different approach).

It should be noted that in view of the one-to-one correspondence between the Rényi divergence and the Alpha divergence of the same order where, for ,

the asymptotic result in (149) can be obtained from ([34], Lemma 4) and vice versa; however, in [34], the focus is on the Rényi divergence from the equiprobable distribution, whereas the result in (149) is obtained by specializing the asymptotic expression in (134) for a general f-divergence. Note also that the result in ([34], Lemma 4) is restricted to , whereas the result in (149) and (150) covers all values of .

In view of (146), (149), (153), (155), and the special cases of the Alpha divergences in (140)–(144), it follows that for all and for every integer

and the upper bounds on the right sides of (157)–(161) are asymptotically tight in the limit where n tends to infinity.

Theorem 9.

The function Δ satisfies the following properties:

- (a)

- For every , is a convex function of α over the real line, and it is symmetric around with a global minimum at .

- (b)

- The following inequalities hold:

- (c)

- For every , is monotonically increasing and continuous in , and .

Proof.

See Appendix H.1. □

Remark 6.

The symmetry of around (see Theorem 9 (a)) is not implied by the following symmetry property of the Alpha divergence around (see, e.g., ([8], p. 36)):

Relying on Theorem 9, the following corollary gives a similar result to (146) where the order of Q and in is switched.

Corollary 1.

For all and ,

Proof.

See Appendix H.2. □

We next further exemplify Theorem 7 for the relative entropy. Let for . Then, , so the bounds on the second derivative of f over the interval are given by and . Theorem 7 (h) gives the following bounds:

Furthermore, (96) gives that

which, for , is a looser bound in comparison to (167). It can be verified, however, that the dominant term in the Taylor series expansion (around ) of the right side of (167) coincides with the right side of (168), so the bounds scale similarly for small values of .

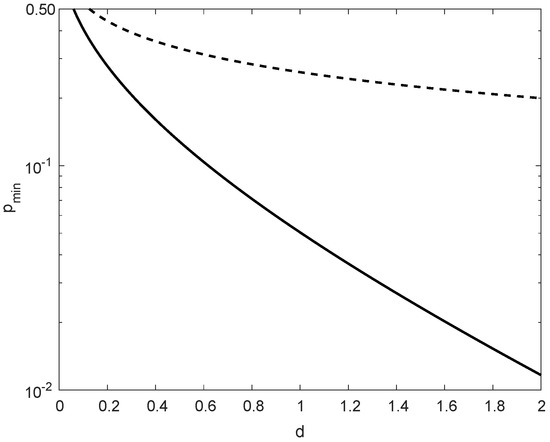

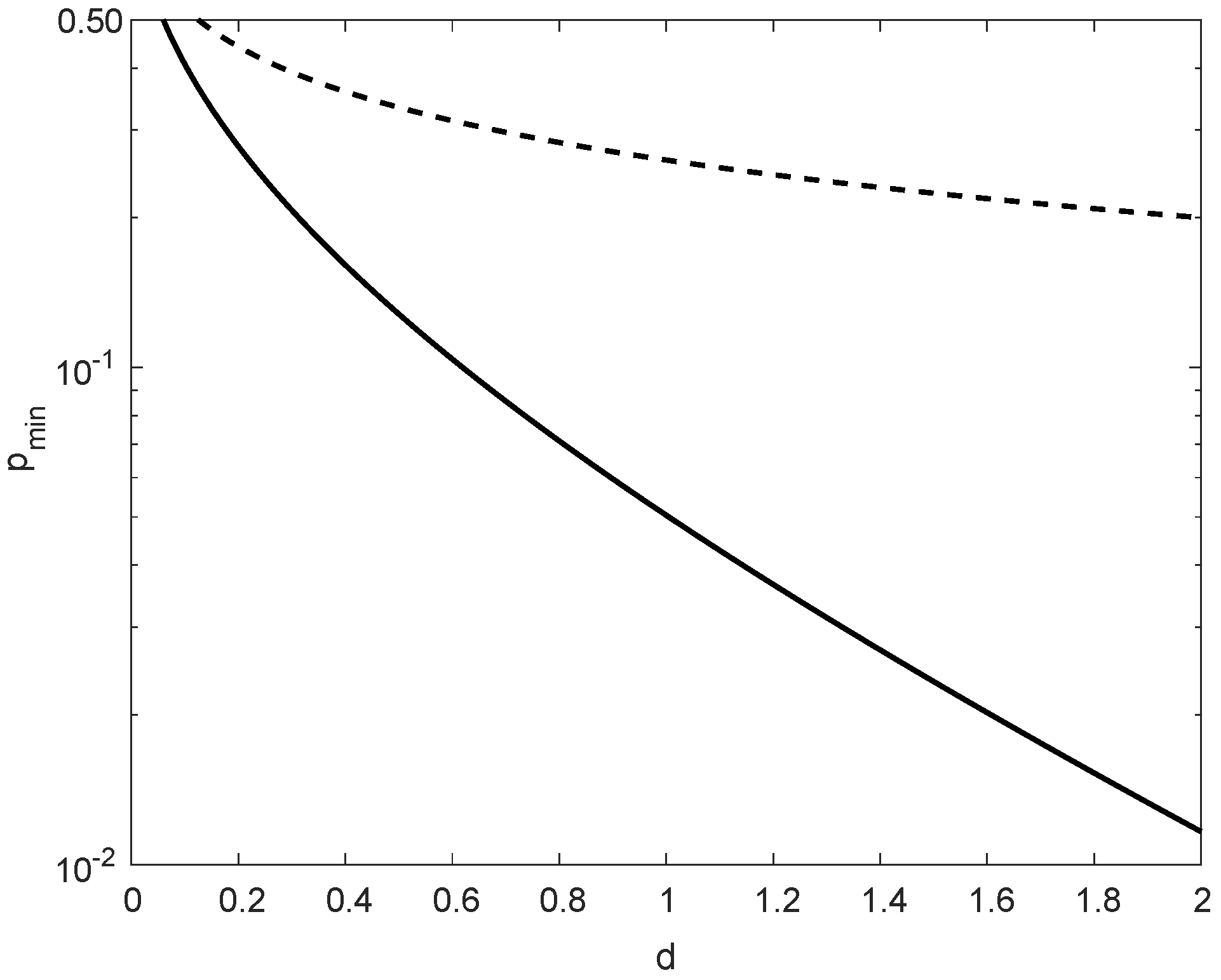

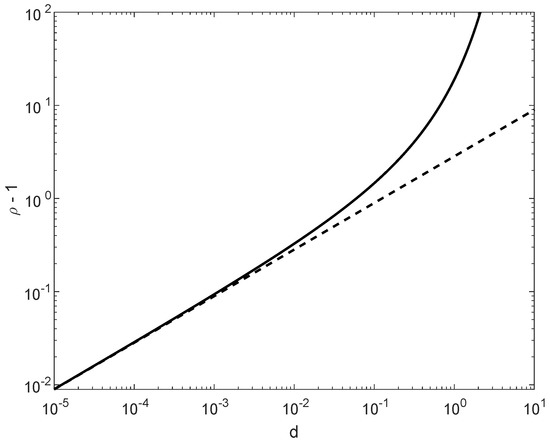

Suppose that we wish to assert that, for every integer and for all probability mass functions , the condition

holds with a fixed . Due to the left side inequality in (89), this condition is equivalent to the requirement that

Due to the asymptotic tightness of the upper bound in the right side of (157) (as we let ), requiring that this upper bound is not larger than is necessary and sufficient for the satisfiability of (169) for all n and . This leads to the analytical solution with (see Appendix I)

where and denote, respectively, the principal and secondary real branches of the Lambert W function [37]. Requiring the stronger condition where the right side of (168) is not larger than leads to the sufficient solution with the simple expression

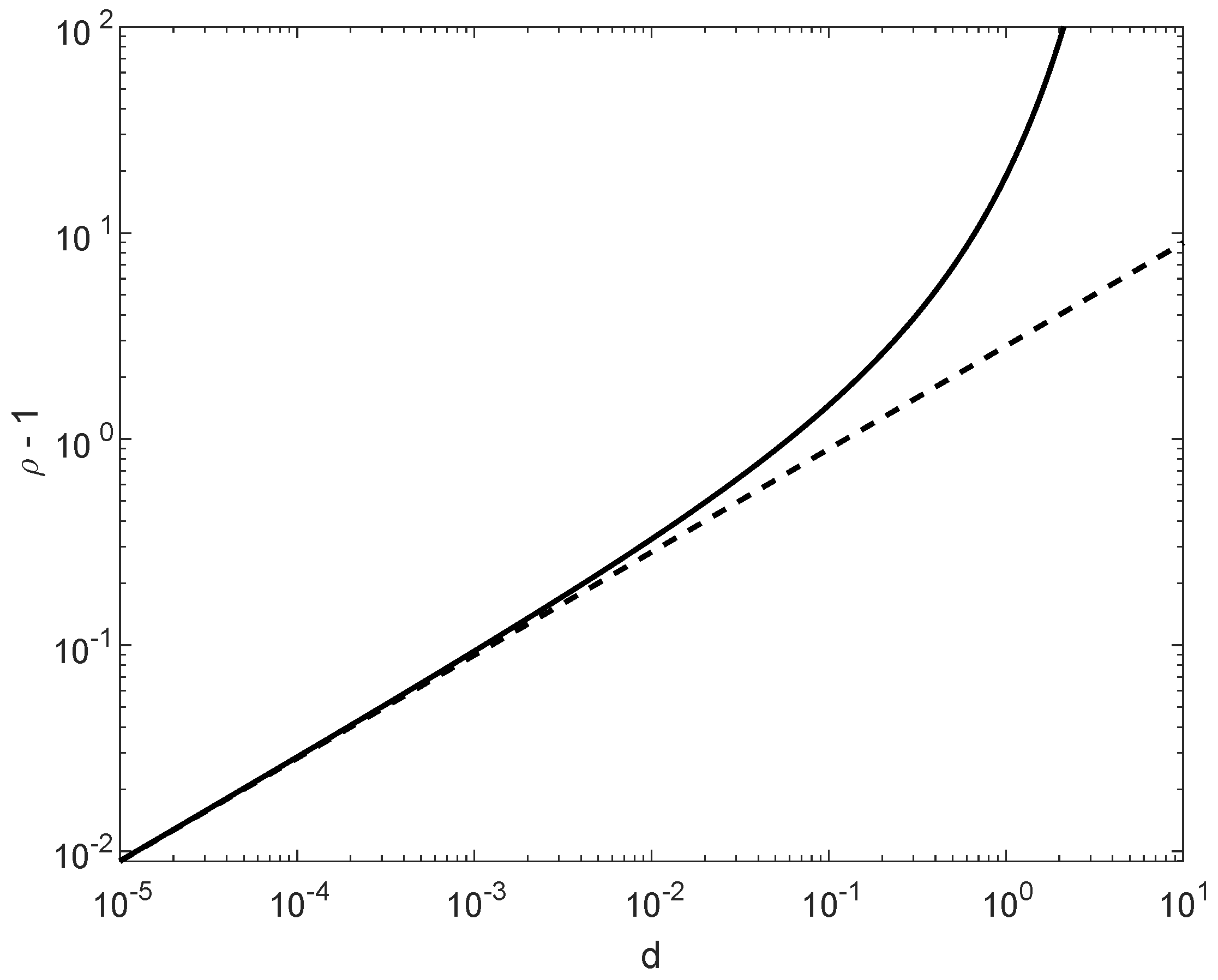

In comparison to in (171), in (172) is more insightful; these values nearly coincide for small values of , providing in that case the same range of possible values of for asserting the satisfiability of condition (169). As it is shown in Figure 5, for , the difference between the maximal values of in (171) and (172) is marginal, though in general for all .

Figure 5.

A comparison of the maximal values of (minus 1) according to (171) and (172), asserting the satisfiability of the condition , with an arbitrary , for all integers and probability mass functions Q supported on with . The solid line refers to the necessary and sufficient condition which gives (171), and the dashed line refers to a stronger condition which gives (172).

3.3.3. The Subclass of f-Divergences in Theorem 5

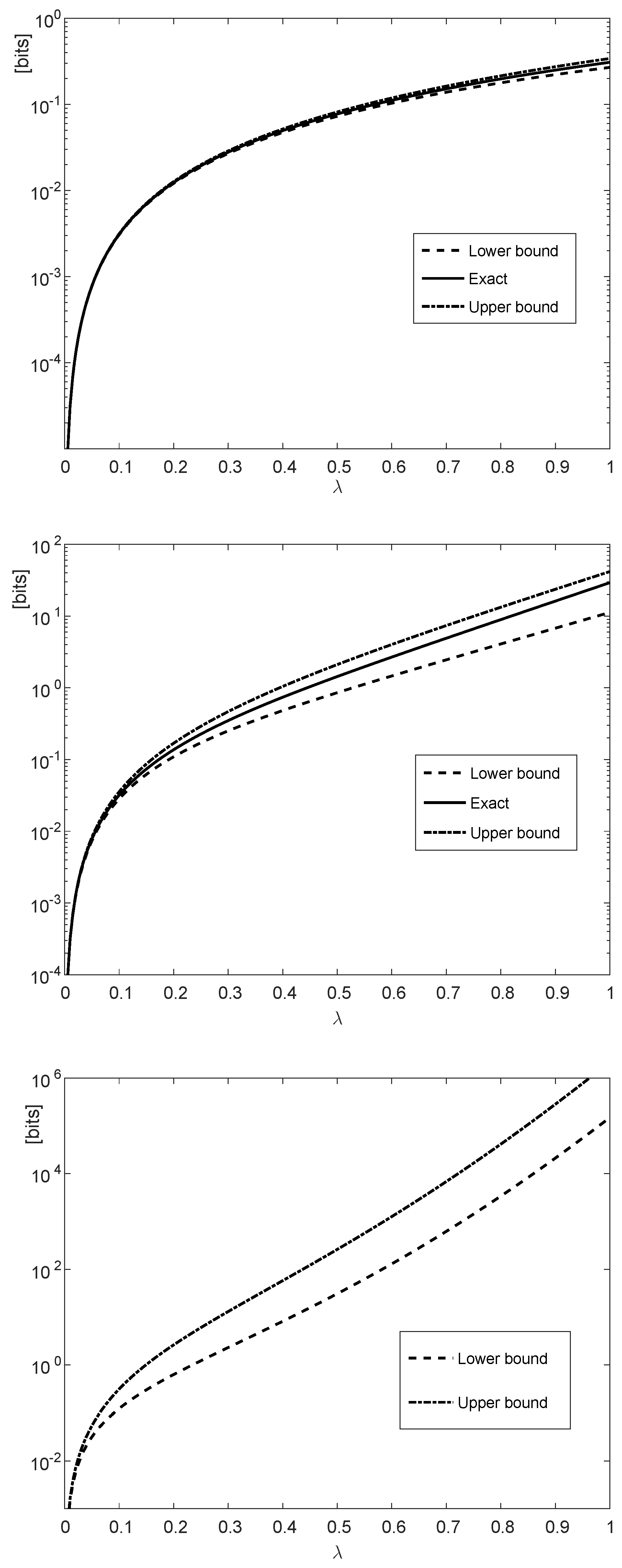

This example refers to the subclass of f-divergences in Theorem 5. For these -divergences, with , substituting from (55) into the right side of (134) gives that for all

The exact asymptotic expression in the right side of (175) is subject to numerical maximization.

We next provide two alternative closed-form upper bounds, based on Theorems 5 and 7, and study their tightness. The two upper bounds, for all and , are given by (see Appendix J)

and

Suppose that we wish to assert that, for every integer and for all probability mass functions , the condition

holds with a fixed and . Due to (173)–(174) and the left side inequality in (89), the satisfiability of the latter condition is equivalent to the requirement that

In order to obtain a sufficient condition for to satisfy (179), expressed as an explicit function of and d, the upper bound in the right side of (176) is slightly loosened to

where

for all and . The upper bounds in the right sides of (176), (177) and (180) are derived in Appendix J.

In comparison to (179), the stronger requirement that the right side of (180) is less than or equal to gives the sufficient condition

with

Figure 6 compares the exact expression in (175) with its upper bounds in (176), (177) and (180). These bounds show good match with the exact value, and none of the bounds in (176) and (177) is superseded by the other; the bound in (180) is looser than (176), and it is derived for obtaining the closed-form solution in (183)–(185). The bound in (176) is tighter than the bound in (177) for small values of , whereas the latter bound outperforms the first one for sufficiently large values of . It has been observed numerically that the tightness of the bounds is improved by increasing the value of , and the range of parameters of over which the bound in (176) outperforms the second bound in (177) is enlarged when is increased. It is also shown in Figure 6 that the bound in (176) and its loosened version in (180) almost coincide for sufficiently small values of (i.e., for is close to 1), and also for sufficiently large values of .

3.4. An Interpretation of in Theorem 7

We provide here an interpretation of in (77), for and an integer ; note that since . Before doing so, recall that (82) introduces an identity which significantly simplifies the numerical calculation of , and (85) gives (asymptotically tight) upper and lower bounds.

The following result relies on the variational representation of f-divergences.

Theorem 10.

Let be convex with , and let be the convex conjugate function of f (a.k.a. the Fenchel-Legendre transform of f), i.e.,

Let , and define for an integer . Then, the following holds:

- (a)

- For every , a random variable , and a function ,

- (b)

- There exists such that, for every , there is a function which satisfieswith .

Proof.

See Appendix K. □

Remark 7.

The proof suggests a constructive way to obtain, for an arbitrary , a function which satisfies (188).

4. Applications in Information Theory and Statistics

4.1. Bounds on the List Decoding Error Probability with f-Divergences

The minimum probability of error of a random variable X given Y, denoted by , can be achieved by a deterministic function (maximum-a-posteriori decision rule) (see [42]):

Fano’s inequality [46] gives an upper bound on the conditional entropy as a function of (or, otherwise, providing a lower bound on as a function of when X takes a finite number of possible values.

The list decoding setting, in which the hypothesis tester is allowed to output a subset of given cardinality, and an error occurs if the true hypothesis is not in the list, has great interest in information theory. A generalization of Fano’s inequality to list decoding, in conjunction with the blowing-up lemma ([17], Lemma 1.5.4), leads to strong converse results in multi-user information theory. This approach was initiated in ([47], Section 5) (see also ([48], Section 3.6)). The main idea of the successful combination of these two tools is that, given a code, it is possible to blow-up the decoding sets in a way that the probability of decoding error can be as small as desired for sufficiently large blocklengths; since the blown-up decoding sets are no longer disjoint, the resulting setup is a list decoder with sub-exponential list size (as a function of the block length).

In statistics, Fano’s-type lower bounds on Bayes and minimax risks, expressed in terms of f-divergences, are derived in [49,50].

In this section, we further study the setup of list decoding, and derive bounds on the average list decoding error probability. We first consider the special case where the list size is fixed (see Section 4.1.1), and then move to the more general case of a list size which depends on the channel observation (see Section 4.1.2).

4.1.1. Fixed-Size List Decoding

A generalization of Fano’s inequality for fixed-size list decoding is given in ([42], (139)), expressed as a function of the conditional Shannon entropy (strengthening ([51], Lemma 1)). A further generalization in this setup, which is expressed as a function of the Arimoto-Rényi conditional entropy with an arbitrary positive order (see Definition 9), is provided in ([42], Theorem 8).

The next result provides a generalized Fano’s inequality for fixed-size list decoding, expressed in terms of an arbitrary f-divergence. Some earlier results in the literature are reproduced from the next result, followed by its strengthening as an application of Theorem 1.

Theorem 11.

Let be a probability measure defined on with . Consider a decision rule , where stands for the set of subsets of with cardinality L, and is fixed. Denote the list decoding error probability by . Let denote an equiprobable probability mass function on . Then, for every convex function with ,

Proof.

See Appendix L. □

Remark 8.

The case where (i.e., a decoder with a single output) gives ([50], (5)).

As consequences of Theorem 11, we first reproduce some earlier results as special cases.

Corollary 2

([42] (139)). Under the assumptions in Theorem 11,

where denotes the binary relative entropy, defined as the continuous extension of for .

Proof.

Theorem 11 enables to reproduce a result in [42] which generalizes Corollary 2. It relies on Rényi information measures, and we first provide definitions for a self-contained presentation.

Definition 8

([40]). Let be a probability mass function defined on a discrete set . The Rényi entropy of order of X, denoted by or , is defined as

The Rényi entropy is continuously extended at orders 0, 1, and ∞; at order 1, it coincides with the Shannon entropy .

Definition 9

([52]). Let be defined on , where X is a discrete random variable. The Arimoto-Rényi conditional entropy of order of X given Y is defined as follows:

- If , then

- The Arimoto-Rényi conditional entropy is continuously extended at orders 0, 1, and ∞; at order 1, it coincides with the conditional Shannon entropy .

Definition 10

([42]). For all , the binary Rényi divergence of order α, denoted by for , is defined as . It is the continuous extension to of

For ,

The following result, generalizing Corollary 2, is shown to be a consequence of Theorem 11. It has been originally derived in ([42], Theorem 8) in a different way. The alternative derivation of this inequality relies on Theorem 11, applied to the family of Alpha-divergences (see (138)) as a subclass of the f-divergences.

Corollary 3

Proof.

See Appendix M. □

Another application of Theorem 11 with the selection , for and a parameter , gives the following result.

Corollary 4.

The following refinement of the generalized Fano’s inequality in Theorem 11 relies on the version of the strong data-processing inequality in Theorem 1.

Theorem 12.

Under the assumptions in Theorem 11, let the convex function be twice differentiable, and assume that there exists a constant such that

where

and the interval is defined in (23). Let for . Then,

Proof.

See Appendix N. □

An application of Theorem 12 gives the following tightened version of Corollary 2.

Corollary 5.

Under the assumptions in Theorem 11, the following holds:

Proof.

Remark 9.

Remark 10.

The ceil operation in the right side of (217) is redundant with denoting the list decoding error probability (see (A335)–(A341)). However, for obtaining a lower bound on with (217), the ceil operation assures that the bound is at least as good as the lower bound which relies on the generalized Fano’s inequality in (193).

Example 1.

Let X and Y be discrete random variables taking values in and , respectively, and let be the joint probability mass function, given by

Let the list decoder select the L most probable elements from , given the value of . Table 1 compares the list decoding error probability with the lower bound which relies on the generalized Fano’s inequality in (193), its tightened version in (217), and the closed-form lower bound in (210) for fixed list sizes of . For and , (217) improves the lower bound in (193) (see Table 1). If , then the generalized Fano’s lower bound in (193) and also (210) are useless, whereas (217) gives a non-trivial lower bound. It is shown here that none of the new lower bounds in (210) and (217) is superseded by the other.

4.1.2. Variable-Size List Decoding

In the more general setting of list decoding where the size of the list may depend on the channel observation, Fano’s inequality has been generalized as follows.

Proposition 5

(([48], Appendix 3.E) and [53]). Let be a probability measure defined on with . Consider a decision rule , and let the (average) list decoding error probability be given by with for all . Then,

where denotes the binary entropy function. If almost surely, then also

By relying on the data-processing inequality for f-divergences, we derive in the following an alternative explicit lower bound on the average list decoding error probability . The derivation relies on the divergence (see, e.g., [54]), which forms a subclass of the f-divergences.

Theorem 13.

Let , and let for all . Then, (222) holds with equality if, for every , the list decoder selects the most probable elements in given ; if denotes the ℓ-th most probable element in given , where ties in probabilities are resolved arbitrarily, then (222) holds with equality if

with being an arbitrary function which satisfies

Proof.

See Appendix O. □

Example 2.

Let X and Y be discrete random variables taking their values in and , respectively, and let be their joint probability mass function, which is given by

Let and be the lists in , given the value of . We get , so the conditional probability mass function of X given Y satisfies for all . It can be verified that, if , then , and also (223) and (224) are satisfied (here, , and ). By Theorem 13, it follows that (222) holds in this case with equality, and the list decoding error probability is equal to (i.e., it coincides with the lower bound in the right side of (222) with ). On the other hand, the generalized Fano’s inequality in (220) gives that (the left side of (220) is bits); moreover, by letting , (221) gives the looser lower bound . This exemplifies a case where the lower bound in Theorem 13 is tight, whereas the generalized Fano’s inequalities in (220) and (221) are looser.

4.2. A Measure for the Approximation of Equiprobable Distributions by Tunstall Trees

The best possible approximation of equiprobable distributions, which one can get by using tree codes has been considered in [38]. The optimal solution is obtained by using Tunstall codes, which are variable-to-fixed lossless compression codes (see ([55], Section 11.2.3), [56]). The main idea behind Tunstall codes is parsing the source sequence into variable-length segments of roughly the same probability, and then coding all these segments with codewords of fixed length. This task is done by assigning the leaves of a Tunstall tree, which correspond to segments of source symbols with a variable length (according to the depth of the leaves in the tree), to codewords of fixed length. The following result links Tunstall trees with majorization theory.

Proposition 6

([38] Theorem 1). Let be the probability measure generated on the leaves by a Tunstall tree , and let be the probability measure generated by an arbitrary tree with the same number of leaves as of . Then, .

From Proposition 6, and the Schur-convexity of an f-divergence (see ([38], Lemma 1)), it follows that (see ([38], Corollary 1))

where n designates the joint number of leaves of the trees and .

Before we proceed, it is worth noting that the strong data-processing inequality in Theorem 6 implies that if f is also twice differentiable, then (226) can be strengthened to

where and denote, respectively, the maximal and minimal positive masses of on the n leaves of a tree , and is given in (26).

We next consider a measure which quantifies the quality of the approximation of the probability mass function , induced by the leaves of a Tunstall tree, by an equiprobable distribution over a set whose cardinality (n) is equal to the number of leaves in the tree. To this end, consider the setup of Bayesian binary hypothesis testing where a random variable X has one of the two probability distributions

with a-priori probabilities , and for an arbitrary . The measure being considered here is equal to the difference between the minimum a-priori and minimum a-posteriori error probabilities of the Bayesian binary hypothesis testing model in (228), which is close to zero if the two distributions are sufficiently close.

The difference between the minimum a-priori and minimum a-posteriori error probabilities of a general Bayesian binary hypothesis testing model with the two arbitrary alternative hypotheses and with a-priori probabilities and , respectively, is defined to be the order- DeGroot statistical information [57] (see also ([16], Definition 3)). It can be expressed as an f-divergence:

where is the convex function with , given by (see ([16], (73)))

The measure considered here for quantifying the closeness of to the equiprobable distribution is therefore given by

which is bounded in the interval .

The next result partially relies on Theorem 7.

Theorem 14.

- (a)

- It is the minimum of with respect to all probability measures that are induced by an arbitrary tree with n leaves.

- (b)

- (c)

- The following bound holds for every , which is the asymptotic limit of the right side of (232) as we let :

- (d)

- If is convex and twice differentiable, continuous at zero and , then

Proof.

See Appendix P.1. □

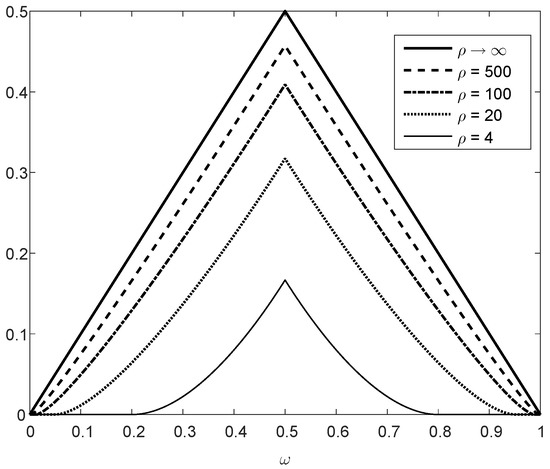

Remark 12.

Figure 7 refers to the upper bound on the closeness-to-equiprobable measure in (233) for Tunstall trees with n leaves. The bound holds for all , and it is shown as a function of for several values of . In the limit where , the upper bound is equal to since the minimum a-posteriori error probability of the Bayesian binary hypothesis testing model in (228) tends to zero. On the other hand, if , then the right side of (233) is identically equal to zero (since ).

Figure 7.

Curves of the upper bound on the measure in (233), valid for all , as a function of for different values of .

Theorem 14 gives an upper bound on the measure in (231), for the closeness of the probability mass function generated on the leaves by a Tunstall tree to the equiprobable distribution, where this bound is expressed as a function of the minimal probability mass of the source. The following result, which relies on ([33], Theorem 4) and our earlier analysis related to Theorem 7, provides a sufficient condition on the minimal probability mass for asserting the closeness of the compression rate to the Shannon entropy of a stationary and memoryless discrete source.

Theorem 15.

Let P be a probability mass function of a stationary and memoryless discrete source, and let the emitted source symbols be from an alphabet of size . Let be a Tunstall code which is used for source compression; let m and denote, respectively, the fixed length and the alphabet of the codewords of (where ), referring to a Tunstall tree of n leaves with . Let be the minimal probability mass of the source symbols, and let

with an arbitrary such that . If

where and denote, respectively, the principal and secondary real branches of the Lambert W function [37], then the compression rate of the Tunstall code is larger than the Shannon entropy of the source by a factor which is at most .

Proof.

See Appendix P.2. □

Remark 13.

Example 3.

Consider a memoryless and stationary binary source, and a binary Tunstall code with codewords of length referring to a Tunstall tree with leaves. Letting in Theorem 15, it follows that if the minimal probability mass of the source satisfies (see (235), and Figure 8 with ), then the compression rate of the Tunstall code is at most larger than the Shannon entropy of the source.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Guest Editor, Amos Lapidoth, and the two anonymous reviewers for an efficient process in reviewing and handling this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 1

We start by proving Item (a). By our assumptions on and ,

Since by assumption and are supported on , and and are supported on (see (A5) and (A6)), it follows that the left side inequality in (A7) is strict if the infimum in the left side is equal to 0, and the right side inequality in (A7) is strict if the supremum in the right side is equal to ∞. Hence, due to (18), (19) and (23),

Since by assumption is convex, it follows that its right derivative exists, and it is monotonically non-decreasing and finite on (see, e.g., ([58], Theorem 1.2) or ([59], Theorem 24.1)). A straightforward generalization of ([60], Theorem 1.1) (see ([60], Remark 1)) gives

where

In comparison to ([60], Theorem 1.1), the requirement that f is differentiable on is relaxed here, and the derivative of f is replaced by its right-side derivative. Note that if f is differentiable, then with as defined in (A10) is Bregman’s divergence [61]. The following equality, expressed in terms of Lebesgue-Stieltjes integrals, holds by ([16], Theorem 1):

By combining (A9), (A12) and (A13), it follows that

and an evaluation of the sum in the right side of (A14) gives (see (20), (21) and (A3))

Combining (A14)–(A18) gives (24); (25) is due to the data-processing inequality for f-divergences (applied to the -divergence), and the non-negativity of in (22).

The -divergence is an f-divergence with for . The condition in (22) allows to set here , implying that (24) holds in this case with equality.

We next prove Item (b). Let f be twice differentiable on (see (23)), and let with . Dividing both sides of (22) by , and letting , yields . Since this holds for all , it follows that . We next show that in (26) fulfills the condition in (22), and therefore it is the largest possible value of to satisfy (22). By the mean value theorem of Lagrange, for all with , there exists an intermediate value such that ; hence, , so the condition in (22) is indeed fulfilled with as given in (26).

We next prove Item (c). Let be the dual convex function which is given by for all with . Since , , and are supported on (see (A5) and (A6)), we have

Consequently, it follows that

where (A23) holds due to (A19) and (A20); (A24) follows from (24) with f, and replaced by , and , respectively, which then implies that and in (18) and (19) are, respectively, replaced by and in (A21) and (A22); finally, (A25) holds due to (A21) and (A22). Since by assumption f is twice differentiable on , so is , and

Hence,

where (A27) follows from (24) with f, and replaced by , and , respectively; (A28) holds due to (A26), and (A29) holds by substituting . This proves (27) and (30), where (28) is due to the data-processing inequality for f-divergences, and the non-negativity of .

Similarly to the condition for equality in (24), equality in (27) is satisfied if for all , or equivalently for all . This f-divergence is Neyman’s -divergence where for all P and Q with (due to (30), and since for all ).

The proof of Item (d) follows that same lines as the proof of Items (a)–(c) by replacing the condition in (22) with a complementary condition of the form

We finally prove Item (e) by showing that the lower and upper bounds in (24), (27), (32) and (33) are locally tight. More precisely, let be a sequence of probability mass functions defined on and pointwise converging to which is supported on , let and be the probability mass functions defined on via (20) and (21) with inputs and , respectively, and let and be defined, respectively, by (18) and (19) with being replaced by . By the assumptions in (35) and (36),

Appendix B. Proof of Theorem 2

We start by proving Item (a). By the assumption that and are supported on for all , it follows from (39) that the probability mass functions and are supported on . Consequently, from (41), also is supported on for all . Due to the product forms of and in (39) and (41), respectively, we get from (47) that

and likewise, from (48),

for all . In view of (24), (26), (A35) and (A36), replacing in (24) and (26) with we obtain that, for all ,

Due to the setting in (39)–(44), for all and ,

with

and is the probability mass function at the channel output at time instant i. In particular, setting in (A38) gives

Due to the tensorization property of the divergence, and since , , and are product probability measures (see (39), (41), (A38) and (A40)), it follows that

and

Substituting (A41) and (A42) into the right side of (A37) gives that, for all ,

Due to (41) and (A39), since

and (see ([45], Lemma 5))

for every pair of probability measures , it follows that

Substituting (A47) and (A48) into the right side of (A43) gives (45). For proving the looser bound (46) from (45), and also for later proving the result in Item (c), we rely on the following lemma.

Lemma A1.

Let and be non-negative with for all . Then,

- (a)

- For all ,

- (b)

- If for at least one index i, then

Proof.

Let be defined as

We have , and the first two derivatives of g are given by

and

Since by assumption for all i, it follows from (A53) that for all , which asserts the convexity of g on . Hence, for all ,

where the right-side equality in (A54) is due to (A51) and (A52). This gives (A49).

We next prove Item (b) of Lemma A1. By the Taylor series expansion of the polynomial function g, we get

for all . Since by assumption for all i, and there exists an index such that , it follows that the coefficient of in the right side of (A55) is positive. This yields (A50). □

We obtain here (46) from (45) and Item (a) of Lemma A1. To that end, for , let

with for every . Since by (39), (40), (43) and (44),

it follows from the data-processing inequality for f-divergences, and their non-negativity, that

which yields (46) from (45), (A49), (A56) and (A59).

We next prove Item (b) of Theorem 2. Similarly to the proof of (A37), we get from (32) (rather than (24)) that

Combining (A41), (A42), (A47), (A48) and (A60) gives (49).

We finally prove Item (c) of Theorem 2. In view of (47) and (48), and by the assumption that for all , we get

Since, by assumption f has a continuous second derivative at unity, (26), (31), (A61) and (A62) imply that

From (A56), (A59), and Item (b) of Lemma A1, it follows that

Appendix C. Proof of Theorems 3 and 4

Appendix C.1. Proof of Theorem 3

We first obtain a lower bound on , and then obtain an upper bound on .

where (A67) holds by the definition of g in Theorem 3 with the assumption that ; (A69) is due to Jensen’s inequality and the convexity of g; (A70) holds by the definition of the -divergence; (A71) holds due to the convexity of g, and its differentiability at 1 (due to the differentiability of f at 1); (A72) holds since ; finally, (A73) holds since implies that .

By ([62], Theorem 5), it follows that

where is given in (51). Combining (A66)–(A74) yields (52). Taking suprema on both sides of (52), with respect to all probability mass functions with and , gives (53) since by the definition of in (51), it is monotonically decreasing in and monotonically increasing in , while (18) and (19) yield

Remark A1.

The derivation in (A66)–(A73) is conceptually similar to the proof of ([24], Lemma A.2). However, the function g here is convex, and our derivation involves the -divergence.

Remark A2.

The proof of ([26], Theorem 8) (see Proposition 3 in Section 1.1 here) relies on ([24], Lemma A.2), where the function g is required to be concave in [24,26]. This leads, in the proof of ([26], Theorem 8), to an upper bound on . One difference in the derivation of Theorem 3 is that our requirement on the convexity of g leads to a lower bound on , instead of an upper bound on . Another difference between the proofs of Theorem 3 and ([26], Theorem 8) is that we apply here the result in ([62], Theorem 5) to obtain an upper bound on , whereas the proof of ([26], Theorem 8) relies on a Pinsker-type inequality (see ([63], Theorem 3)) to obtain a lower bound on ; the latter lower bound relies on the condition on f in (16), which is not necessary for the derivation of the bound in Theorem 3.

Remark A3.

From ([62], Theorem 1 (b)), it follows that

with in the right side of (A76) as given in (51), and the supremum in the left side of (A76) is taken over all probability measures P and Q such that . In view of ([62], Theorem 1 (b)), the equality in (A76) holds since the functions , defined as and for all , satisfy and for all probability measures P and Q, and since while the function is also strictly positive on . Furthermore, from the proof of ([62], Theorem 1 (b)), restricting P and Q to be probability mass functions which are defined over a binary alphabet, the ratio can be made arbitrarily close to the supremum in the left side of (A76); such probability measures can be obtained as the output distributions and of an arbitrary non-degenerate stochastic transformation , with , by a suitable selection of probability input distributions and , respectively (see (A5) and (A6)). In the latter case where , this shows the optimality of the non-negative constant in the right side of (A74).

Appendix C.2. Proof of Theorem 4

Combining (A66)–(A73) gives that, for all ,

and from (A74)

From (A41) and (A47),

and similarly, from (A42) and (A48),

Combining (A77)–(A80) yields (54).

Appendix D. Proof of Theorem 5

The function in (55) satisfies , and for all

which yields the convexity of on . This justifies the definition of the f-divergence

for probability mass functions P and Q, which are defined on a finite or countably infinite set , with Q supported on . In the general alphabet setting, sums and probability mass functions are, respectively, replaced by Lebesgue integrals and Radon-Nikodym derivatives. Differentiation of both sides of (A82) with respect to gives

where

The function is convex since

and . Hence, is an f-divergence, and it follows from (A83)–(A85) that

which gives (56), so is monotonically increasing in . Double differentiation of both sides of (A82) with respect to gives

where

The function is concave, and . By referring to the f-divergence , it follows from (A91)–(A93) that

which gives (57), so is concave in for . Differentiation of both sides of (A93) with respect to gives that

which implies that

This gives (58), and it completes the proof of Item (a).

We next prove Item (b). From Item (a), the result in (59) holds for . We provide in the following a proof of (59) for all . In view of (A98), it can be verified that for ,

which, from (A82), implies that

with

The function is convex for , with . By referring to the f-divergence , its non-negativity and (A103) imply that for all

Furthermore, we get the following explicit formula for n-th partial derivative of with respect to for :

where (A107) holds due to (A103); (A108) follows from (A104), and (A110) is satisfied by the definition of the Rényi divergence [40] which is given by

with by continuous extension of at . For , the right side of (A110) is simplified to the right side of (58); this holds due to the identity

To prove Item (c), from (55), for all

which implies by a Taylor series expansion of that

where in the right side of (A116) is an intermediate value between 1 and t. Hence, for ,

where (A117) follows from (A116) since and is monotonically decreasing and positive (see (A115)); in the right side of (A117) denotes the indicator function which is equal to 1 if the relation holds, and it is otherwise equal to zero; (A118) holds since for all , and ; finally, (A119) follows by substituting (A114) and (A115) into the right side of (A118), which gives the equality

with as defined in (63). Since the first term in the right side of (A119) does not affect an f-divergence (as it is equal to for and some constant c), and for an arbitrary positive constant and for , we get , inequality (61) follows from (A117) and (A119). To that end, note that defined in (63) is monotonically increasing in , and therefore for all . Due to the inequality (see, e.g., ([64], Theorem 5), followed by refined versions in ([62], Theorem 20) and ([65], Theorem 9))

the looser lower bound on in the right side of (62), expressed as a function of the relative entropy , follows from (61). Hence, if P and Q are not identical, then (64) follows from (61) since and .

We next prove Item (d). The Taylor series expansion of implies that, for all ,

where in the right side of (A122) is an intermediate value between 1 and t. Consequently, since and , it follows from (A122) that, for all ,

Based on (A123)–(A125), it follows that

where (A127) holds due to (A111) (with ). Substituting (A114) and (A115) into the right side of (A127) gives (65).

We next prove Item (e). Let P and Q be probability mass functions such that , and let be arbitrarily small. Since the Rényi divergence is monotonically non-decreasing in (see ([66], Theorem 3)), it follows that , and therefore also

In view of (61), there exists such that for all

and, from (65), there exists such that for all

Letting gives the result in (66) for all .

Item (f) of Theorem 5 is a direct consequence of ([45], Lemma 4), which relies on ([67], Theorem 3). Let for (hence, is the divergence). If a sequence converges to a probability measure Q in the sense that the condition in (67) is satisfied, and for all sufficiently large n, then ([45], Lemma 4) yields

which gives (68) from (A114) and (A131).

We next prove Item (g). Inequality (69) is trivial. Inequality (70) is obtained as follows:

where (A133) follows from (56), and (A134) holds since the function given by

is monotonically decreasing in u (note that by increasing the value of the non-negative variable u, the probability mass function gets closer to Q). This gives (70).

For proving inequality (71), we obtain two upper bounds on with . For the derivation of the first bound, we rely on (A83). From (A84) and (A85),

where is given by

with the convention that (by a continuous extension of at ). Since , and

which implies that is convex on , we get

where (A141) holds due to (A83) (recall the convexity of with ); (A142) holds due to (A138) and since for implies that ; finally, (A143) follows from the non-negativity of the f-divergence . Consequently, integration over the interval () on the left side of (A141) and the right side of (A143) gives

Note that the same reasoning of (A132)–(A136) also implies that

which gives a second upper bound on the left side of (A145). Taking the minimal value among the two upper bounds in the right sides of (A144) and (A145) gives (71) (see Remark A4).

We finally prove Item (h). From (55) and (A81), the function is convex for with , , and it is also differentiable at 1. It is left to prove that the function , defined as for , is convex. From (55), the function is given explicitly by

and its second derivative is given by

with

Since , and

it follows that for all ; hence, from (A147), for , which yields the convexity of the function on for all . This shows that, for every , the function satisfies all the required conditions in Theorems 3 and 4. We proceed to calculate the function in (51), which corresponds to , i.e., (see (72)),

with

where the definition of is obtained by continuous extension of the function at (recall that the function is given in (55)). Differentiation shows that

where, for ,

and

From (A156), it follows that if , , and if . Since is therefore monotonically decreasing on and it is monotonically increasing on , (A155) implies that

Since (see (A154)), and is monotonically increasing on , it follows that for all and for all . This implies that for all (see (A153)); hence, from (A152), the function is monotonically increasing on , and it is continuous over this interval (see (A151)). It therefore follows from (A150) that

for every and (independently of ), which proves (73).

Remark A4.

None of the upper bounds in the right sides of (A144) and (A145) supersedes the other. For example, if P and Q correspond to and , respectively, and , then the right sides of (A144) and (A145) are, respectively, equal to and . If on the other hand , then the right sides of (A144) and (A145) are, respectively, equal to and .

Appendix E. Proof of Theorem 6

By assumption, where the probability mass functions P and Q are defined on the set . The majorization relation is equivalent to the existence of a doubly-stochastic transformation such that (see Proposition 4)

(See, e.g., ([32], Theorem 2.1.10) or ([30], Theorem 2.B.2) or ([31], pp. 195–204)). Define

The probability mass functions given by

satisfy, respectively, (20) and (21). The first one is obvious from (A159)–(A161); equality (21) holds due to the fact that is a doubly stochastic transformation, which implies that for all

Since (by assumption) and are supported on , relations (20) and (21) hold in the setting of (A159)–(A161), and is (by assumption) convex and twice differentiable, it is possible to apply the bounds in Theorem 1 (b) and (d). To that end, from (18), (19), (A160) and (A161),

which, from (24), (25), (32), (A160), (A161) and (A164), give that

The difference of the divergences in the left side of (A166) and the right side of (A167) satisfies

and the substitution of (A169) into the bounds in (A166) and (A167) give the result in (74) and (75).

Let for , which yields from (26) and (31) that . Since , it follows from (A169) that the upper and lower bounds in the left side of (74) and the right side of (75), respectively, coincide for the -divergence; this therefore yields the tightness of these bounds in this special case.

We next prove (76). The following lower bound on the second-order Rényi entropy (a.k.a. the collision entropy) holds (see ([34], (25)–(27))):

where . This gives

By Cauchy-Schwartz inequality which, together with (A171), give

In view of the Schur-concavity of the Rényi entropy (see ([30], Theorem 13.F.3.a.)), the assumption implies that

and an exponentiation of both sides of (A173) (see the left-side equality in (A170)) gives

Combining (A172) and (A173) gives (76).

Appendix F. Proof of Theorem 7

We prove Item (a), showing that the set (with ) is non-empty, convex and compact. Note that is a singleton, so the claim is trivial for .

Let . The non-emptiness of is trivial since . To prove the convexity of , let , and let and be the (positive) maximal and minimal probability masses of and , respectively. Then, and yield

For every ,

Combining (A175)–(A177) implies that

so for all . This proves the convexity of .

The set of probability mass functions is clearly bounded; for showing its compactness, it is left to show that is closed. Let , and let be a sequence of probability mass functions in which pointwise converges to P over the finite set . It is required to show that . As a limit of probability mass functions, , and since by assumption for all , it follows that

which yields for all m. Since for every m, it follows that also for the limiting probability mass function P we have , and . This proves that , and therefore is a closed set.

An alternative proof for Item (a) relies on the observation that, for ,

which yields the convexity and compactness of the set for all .

The result in Item (b) holds in view of Item (a), and due to the convexity and continuity of in (where ). This implication is justified by the statement that a convex and continuous function over a non-empty convex and compact set attains its supremum over this set (see, e.g., ([68], Theorem 7.42) or ([59], Theorem 10.1 and Corollary 32.3.2)).

We next prove Item (c). If , then where the lower bound on is attained when Q is the probability mass function with masses equal to and a single smaller mass equal to , and the upper bound is attained when Q is the equiprobable distribution. For an arbitrary , let where can get any value in the interval defined in (79). By ([34], Lemma 1), and where is given in (80). The Schur-convexity of (see ([38], Lemma 1)) and the identity give that

for all with ; equalities hold in (A180) if . The maximization of and over all probability mass functions can be therefore simplified to the maximization of and , respectively, over the parameter which lies in the interval in (79). This proves (82) and (83).

We next prove Item (e), and then prove Item (d). In view of Item (c), the maximum of over all the probability mass functions is attained by with (see (79)–(81)). From (80), can be expressed as the n-length probability vector

The influence of the -th entry of the probability vector in (A181) on tends to zero as we let . This holds since the entries of the vector in (A181) are written in decreasing order, which implies that for all (with )

from (A182) and the convexity of f on (so, f attains its finite maximum on every closed sub-interval of ), it follows that

In view of (A181) and (A183), by letting , the maximization of over can be replaced by a maximization of where

with the free parameter , and with (the value of is determined so that the total mass of is 1). Hence, we get

The f-divergence in the right side of (A185) satisfies

where (A188) holds by the definition of the function in (84). It therefore follows that

where (A189) holds by combining (82) and (A185)–(A188); (A190) holds by the continuity of the function on , which follows from (84) and the continuity of the convex function f on for (recall that a convex function is continuous on every closed sub-interval of its domain of region, and by assumption f is convex on ). This proves (87), by the definition of in (84).

Equality (88) follows from (87) by replacing with , with as given in (29); this replacement is justified by the equality .

Once Item (e) is proved, we return to prove Item (d). To that end, it is first shown that

for all and integers , with the functions and , respectively, defined in (77) and (78). Since for all , (77) and (78) give that

so the monotonicity property in (A192) follows from (A191) by replacing f with . To prove (A191), let be a probability mass function which attains the maximum at the right side of (77), and let be the probability mass function supported on , and defined as follows:

Since by assumption , (A194) implies that . It therefore follows that

where (A195) and (A201) hold due to (77); (A196) holds since ; finally, (A198) holds due to (A194), which implies that the two sums in the right side of (A197) are identical, and they equal to the sum in the right side of (A198). This gives (A191), and likewise also (A192) (see (A193)).

where (A202) holds since, due to (A191), the sequence is monotonically increasing, which implies that the first term of this sequence is less than or equal to its limit. Equality (A203) holds since the limit in its right side exists (in view of the above proof of (87)), so its limit coincides with the limit of every subsequence; (A204) holds due to (A189) and (A190). A replacement of f with gives, from (A193), that

Combining (A202)–(A205) gives the right-side inequalities in (85) and (86). The left-side inequality in (85) follows by combining (77), (A184) and (A186)–(A188), which gives

Likewise, in view of (A193), the left-side inequality in (86) follows from the left-side inequality in (85) by replacing f with .

We next prove Item (f), providing an upper bound on the convergence rate of the limit in (87); an analogous result can be obtained for the convergence rate to the limit in (88) by replacing f with in (29). To prove (89), in view of Items (d) and (e), we get that for every integer

where (A209) holds due to monotonicity property in (A191), and also due to the existence of the limit of ; (A210) holds due to (85); (A211) holds since the function (as it is defined in (84)) satisfies (recall that by assumption ); (A212) holds since , so the maximization of over the interval is the maximum over the maximal values over the sub-intervals for ; finally, (A213) holds since the maximum of a sum of functions is less than or equal to the sum of the maxima of these functions. If the function is differentiable on , and its derivative is upper bounded by , then by the mean value theorem of Lagrange, for every ,

Combining (A209)–(A214) gives (89).

We next prove Item (g). By definition, it readily follows that if . By the definition in (77), for a fixed integer , it follows that the function is monotonically increasing on . The limit in the left side of (90) therefore exists. Since is convex in Q, its maximum over the convex set of probability mass functions is obtained at one of the vertices of the simplex . Hence, a maximum of over this set is attained at with for some , and for . In the latter case,

Note that (since the union of , for all , includes all the probability mass functions in which are supported on , so is not an element of this union); hence, it follows that

On the other hand, for every ,

where (A217) holds due to the left-side inequality of (85), and (A218) is due to (84). Combining (A217) and (A218), and the continuity of f at zero (by the continuous extension of the convex function f at zero), yields (by letting )

Combining (A216) and (A219) gives (90) for every integer . In order to get an upper bound on the convergence rate in (90), suppose that , f is differentiable on , and . For every , we get

where (A220) holds since the sets are monotonically increasing in ; (A221) follows from (A216)–(A218); (A222) holds by the assumption that for all , by the mean value theorem of Lagrange, and since for all and . This proves (91).

We next prove Item (h). Setting yields for every probability mass function Q which is supported on . Since and , and since by assumption , it follows that

Combining the assumption in (92) with (A224) implies that

The lower bound on in the left side of (94) follows from a combination of (75), the left-side inequality in (A226), and . Similarly, the upper bound on in the right side of (95) follows from a combination of (74), the right-side inequality in (A226), and the equality . The looser upper bound on in the right side of (96), expressed as a function of M and , follows by combining (74), (76), and the right-side inequality in (A226).

The tightness of the lower bound in the left side of (94) and the upper bound in the right side of (95) for the divergence is clear from the fact that if for all ; in this case, .

To prove Item (i), suppose that the second derivative of f is upper bounded on with for all , and there is a need to assert that for an arbitrary . Condition (97) follows from (96) by solving the inequality , with the variable , for given and (note that does not depend on ).

Appendix G. Proof of Theorem 8

The proof of Theorem 8 relies on Theorem 6. For , let be the non-negative and convex function given by (see, e.g., ([8], (2.1)) or ([16], (17)))

and let be the convex function given by

Let P and Q be probability mass functions which are supported on a finite set; without loss of generality, let their support be given by . Then, for ,

where

designates the order- Tsallis entropy of a probability mass P defined on the set . Equality (A229) also holds for by continuous extension.