Abstract

This paper provides tight bounds on the Rényi entropy of a function of a discrete random variable with a finite number of possible values, where the considered function is not one to one. To that end, a tight lower bound on the Rényi entropy of a discrete random variable with a finite support is derived as a function of the size of the support, and the ratio of the maximal to minimal probability masses. This work was inspired by the recently published paper by Cicalese et al., which is focused on the Shannon entropy, and it strengthens and generalizes the results of that paper to Rényi entropies of arbitrary positive orders. In view of these generalized bounds and the works by Arikan and Campbell, non-asymptotic bounds are derived for guessing moments and lossless data compression of discrete memoryless sources.

1. Introduction

Majorization theory is a simple and productive concept in the theory of inequalities, which also unifies a variety of familiar bounds [1,2]. These mathematical tools find various applications in diverse fields (see, e.g., [3]) such as economics [2,4,5], combinatorial analysis [2,6], geometric inequalities [2], matrix theory [2,6,7,8], Shannon theory [5,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], and wireless communications [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

This work, which relies on the majorization theory, has been greatly inspired by the recent insightful paper by Cicalese et al. [12] (the research work in the present paper has been initialized while the author handled [12] as an associate editor). The work in [12] provides tight bounds on the Shannon entropy of a function of a discrete random variable with a finite number of possible values, where the considered function is not one to one. For that purpose, and while being of interest by its own right (see [12], Section 6), a tight lower bound on the Shannon entropy of a discrete random variable with a finite support was derived in [12] as a function of the size of the support, and the ratio of the maximal to minimal probability masses. The present paper aims to extend the bounds in [12] to Rényi entropies of arbitrary positive orders (note that the Shannon entropy is equal to the Rényi entropy of order 1), and to study the information-theoretic applications of these (non-trivial) generalizations in the context of non-asymptotic analysis of guessing moments and lossless data compression.

The motivation for this work is rooted in the diverse information-theoretic applications of Rényi measures [34]. These include (but are not limited to) asymptotically tight bounds on guessing moments [35], information-theoretic applications such as guessing subject to distortion [36], joint source-channel coding and guessing with application to sequential decoding [37], guessing with a prior access to a malicious oracle [38], guessing while allowing the guesser to give up and declare an error [39], guessing in secrecy problems [40,41], guessing with limited memory [42], and guessing under source uncertainty [43]; encoding tasks [44,45]; Bayesian hypothesis testing [9,22,23], and composite hypothesis testing [46,47]; Rényi generalizations of the rejection sampling problem in [48], motivated by the communication complexity in distributed channel simulation, where these generalizations distinguish between causal and noncausal sampler scenarios [49]; Wyner’s common information in distributed source simulation under Rényi divergence measures [50]; various other source coding theorems [23,39,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58], channel coding theorems [23,58,59,60,61,62,63,64], including coding theorems in quantum information theory [65,66,67].

The presentation in this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides notation and essential preliminaries for the analysis in this paper. Section 3 and Section 4 strengthen and generalize, in a non-trivial way, the bounds on the Shannon entropy in [12] to Rényi entropies of arbitrary positive orders (see Theorems 1 and 2). Section 5 relies on the generalized bound from Section 4 and the work by Arikan [35] to derive non-asymptotic bounds for guessing moments (see Theorem 3); Section 5 also relies on the generalized bound in Section 4 and the source coding theorem by Campbell [51] (see Theorem 4) for the derivation of non-asymptotic bounds for lossless compression of discrete memoryless sources (see Theorem 5).

2. Notation and Preliminaries

Let

- P be a probability mass function defined on a finite set ;

- and be, respectively, the maximal and minimal positive masses of P;

- be the sum of the k largest masses of P for (note that and );

- , for an integer , be the set of all probability mass functions defined on with ; without any loss of generality, let ;

- , for and an integer , be the subset of all probability measures such that

Definition 1 (Majorization).

Consider discrete probability mass functions P and Q defined on the same (finite or countably infinite) set . It is said that P is majorized by Q (or Q majorizes P), and it is denoted by , if for all (recall that ). If P and Q are defined on finite sets of different cardinalities, then the probability mass function which is defined over the smaller set is first padded by zeros for making the cardinalities of these sets be equal.

By Definition 1, a unit mass majorizes any other distribution; on the other hand, the equiprobable distribution on a finite set is majorized by any other distribution defined on the same set.

Definition 2 (Schur-convexity/concavity).

A function is said to be Schur-convex if for every such that , we have . Likewise, f is said to be Schur-concave if is Schur-convex, i.e., and imply that .

Definition 3

(Rényi entropy [34]). Let X be a random variable taking values on a finite or countably infinite set , and let be its probability mass function. The Rényi entropy of order is given by

Unless explicitly stated, the logarithm base can be chosen by the reader, with exp indicating the inverse function of log.

By its continuous extension,

where is the (Shannon) entropy of X.

Proposition 1

(Schur-concavity of the Rényi entropy (Appendix F.3.a (p. 562) of [2])). The Rényi entropy of an arbitrary order is Schur-concave; in particular, for , the Shannon entropy is Schur-concave.

Remark 1.

[17] (Theorem 2) strengthens Proposition 1, though it is not needed for our analysis.

Definition 4

(Rényi divergence [34]). Let P and Q be probability mass functions defined on a finite or countably infinite set . The Rényi divergence of order is defined as follows:

- If , then

- By the continuous extension of ,where in the right side of (8) is the relative entropy (a.k.a. Kullback-Leibler divergence).

Throughout this paper, for , denotes the ceiling of a (i.e., the smallest integer not smaller than the real number a), and denotes the flooring of a (i.e., the greatest integer not greater than a).

3. A Tight Lower Bound on the Rényi Entropy

We provide in this section a tight lower bound on the Rényi entropy, of an arbitrary order , when the probability mass function of the discrete random variable is defined on a finite set of cardinality n, and the ratio of the maximal to minimal probability masses is upper bounded by an arbitrary fixed value . In other words, we derive the largest possible gap between the order- Rényi entropies of an equiprobable distribution and a non-equiprobable distribution (defined on a finite set of the same cardinality) with a given value for the ratio of the maximal to minimal probability masses. The basic tool used for the development of our result in this section relies on the majorization theory. Our result strengthens the result in [12] (Theorem 2) for the Shannon entropy, and it further provides a generalization for the Rényi entropy of an arbitrary order (recall that the Shannon entropy is equal to the Rényi entropy of order , see (4)). Furthermore, the approach for proving the main result in this section differs significantly from the proof in [12] for the Shannon entropy. The main result in this section is a key result for all what follows in this paper.

The following lemma is a restatement of [12] (Lemma 6).

Lemma 1.

Let with and an integer , and assume without any loss of generality that the probability mass function P is defined on the set . Let be defined on as follows:

where

Then,

- (1)

- , and ;

- (2)

- .

Proof.

See [12] (p. 2236) (top of the second column). ☐

Lemma 2.

Let , , and be an integer. For

let be defined on as follows:

where

Then, for every ,

Proof.

See Appendix A. ☐

Lemma 3.

For and , let

with . Then, for every ,

and is monotonically increasing in .

Proof.

See Appendix B. ☐

Lemma 4.

For and , the limit

exists, having the following properties:

- (a)

- If , thenand

- (b)

- If , then

- (c)

- For all ,

- For every , and ,

Proof.

See Appendix C. ☐

In view of Lemmata 1–4, we obtain the following main result in this section:

Theorem 1.

Let , , , and let in (16) designate the maximal gap between the order-α Rényi entropies of equiprobable and arbitrary distributions in . Then,

Remark 2.

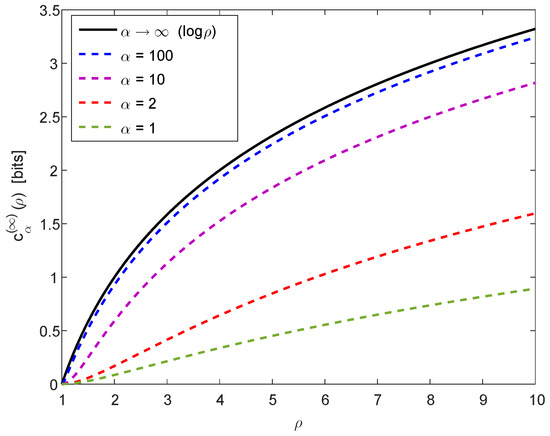

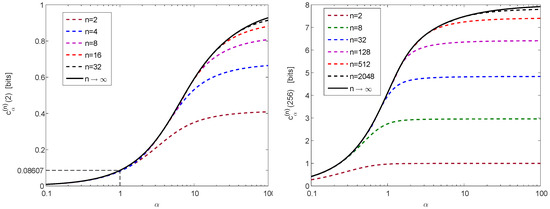

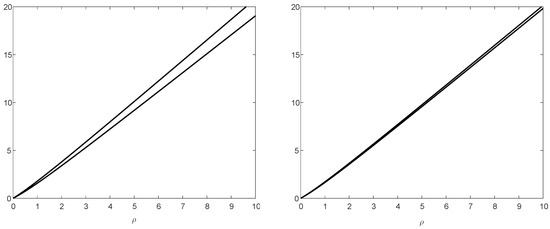

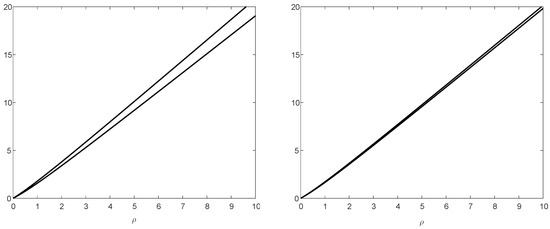

For a numerical illustration of Theorem 1, Figure 1 provides a plot of in (20) and (22) as a function of , confirming numerically the properties in (21) and (23). Furthermore, Figure 2 provides plots of in (16) as a function of , for (left plot) and (right plot), with several values of ; the calculation of the curves in these plots relies on (15), (20) and (22), and they illustrate the monotonicity and boundedness properties in (24).

Figure 2.

Plots of in (16) (log is on base 2) as a function of , for (left plot) and (right plot), with several values of .

Remark 3.

Theorem 1 strengthens the result in [12] (Theorem 2) for the Shannon entropy (i.e., for ), in addition to its generalization to Rényi entropies of arbitrary orders . This is because our lower bound on the Shannon entropy is given by

whereas the looser bound in [12] is given by (see [12] ((7)) and (22) here)

and we recall that (see (24)). Figure 3 shows the improvement in the new lower bound (28) over (29) by comparing versus for and with several values of n. It is reflected from Figure 3 that there is a very marginal improvement in the lower bound on the Shannon entropy (28) over the bound in (29) if (even for small values of n), whereas there is a significant improvement over the bound in (29) for large values of ρ; by increasing the value of n, also the value of ρ needs to be increased for observing an improvement of the lower bound in (28) over (29) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A plot of in (22) versus for finite n (, and 8) as a function of ρ.

An improvement of the bound in (28) over (29) leads to a tightening of the upper bound in [12] (Theorem 4) on the compression rate of Tunstall codes for discrete memoryless sources, which further tightens the bound by Jelinek and Schneider in [69] (Equation (9)). More explicitly, in view of [12] (Section 6), an improved upper bound on the compression rate of these variable-to-fixed lossless source codes is obtained by combining [12] (Equations (36) and (38)) with a tightened lower bound on the entropy of the leaves of the tree graph for Tunstall codes. From (28), the latter lower bound is given by where is expressed in bits, is the reciprocal of the minimal positive probability of the source symbols, and n is the number of codewords (so, all codewords are of length bits). This yields a reduction in the upper bound on the non-asymptotic compression rate R of Tunstall codes from (see [12] (Equation (40)) and (22)) to bits per source symbol where denotes the source entropy (converging, in view of (17), to as we let ).

Remark 4.

Equality (15) with the minimizing probability mass function of the form (13) holds, in general, by replacing the Rényi entropy with an arbitrary Schur-concave function (as it can be easily verified from the proof of Lemma 2 in Appendix A). However, the analysis leading to Lemmata 3–4 and Theorem 1 applies particularly to the Rényi entropy.

4. Bounds on the Rényi Entropy of a Function of a Discrete Random Variable

This section relies on Theorem 1 and majorization for extending [12] (Theorem 1), which applies to the Shannon entropy, to Rényi entropies of any positive order. More explicitly, let and

- and be finite sets of cardinalities and with ; without any loss of generality, let and ;

- X be a random variable taking values on with a probability mass function ;

- be the set of deterministic functions ; note that is not one to one since .

The main result in this section sharpens the inequality , for every deterministic function with and , by obtaining non-trivial upper and lower bounds on . The calculation of the exact value of is much easier, and it is expressed in closed form by capitalizing on the Schur-concavity of the Rényi entropy.

The following main result extends [12] (Theorem 1) to Rényi entropies of arbitrary positive orders.

Theorem 2.

Let be a random variable which satisfies .

- (a)

- For , if , let be the equiprobable random variable on ; otherwise, if , let be a random variable with the probability mass functionwhere is the maximal integer such thatThen, for every ,where

- (b)

- There exists an explicit construction of a deterministic function such thatwhere is independent of α, and it is obtained by using Huffman coding (as in [12] for ).

- (c)

- Let be a random variable with the probability mass functionThen, for every ,

Remark 5.

Setting specializes Theorem 2 to [12] (Theorem 1) (regarding the Shannon entropy). This point is further elaborated in Remark 8, after the proof of Theorem 2.

Remark 6.

Similarly to [12] (Lemma 1), an exact solution of the maximization problem in the left side of (32) is strongly NP-hard [70]; this means that, unless , there is no polynomial time algorithm which, for an arbitrarily small , computes an admissible deterministic function such that

A proof of Theorem 2 relies on the following lemmata.

Lemma 5.

Proof.

Since (see [12] (Lemma 2)) with , and for all such that (see [12] (Lemma 4)), the result follows from the Schur-concavity of the Rényi entropy. ☐

Lemma 6.

Let , , and with . Then,

Proof.

Since f is a deterministic function in with , the probability mass function of is an element in which majorizes (see [12] (Lemma 3)). Inequality (39) then follows from Lemma 5. ☐

We are now ready to prove Theorem 2.

Proof.

In view of (39),

We next construct a function such that, for all ,

where the function in the right side of (41) is given in (33), and (42) holds due to (38) and (40). The function in our proof coincides with the construction in [12], and it is, therefore, independent of .

We first review and follow the concept of the proof of [12] (Lemma 5), and we then deviate from the analysis there for proving our result. The idea behind the proof of [12] (Lemma 5) relies on the following algorithm:

- (1)

- Start from the probability mass function with ;

- (2)

- Merge successively pairs of probability masses by applying the Huffman algorithm;

- (3)

- Stop the merging process in Step 2 when a probability mass function is obtained (with );

- (4)

- Construct the deterministic function by setting for all probability masses , with , being merged in Steps 2–3 into the node of .

Let be the largest index such that (note that corresponds to the case where each node , with , is constructed by merging at least two masses of the probability mass function ). Then, according to [12] (p. 2225),

Let

be the sum of the smallest masses of the probability mass function Q. In view of (43), the vector

represents a probability mass function where the ratio of its maximal to minimal masses is upper bounded by 2.

At this point, our analysis deviates from [12] (p. 2225). Applying Theorem 1 to with gives

with

where (47) follows from (20); (48) is straightforward algebra, and (49) is the definition in (33).

In view of (44), let be the probability mass function which is given by

The validity of (60) is extended to by taking the limit on both sides of this inequality, and due to the continuity of in (33) at . Applying the majorization result in [12] ((31)), it follows from (60) and the Schur-concavity of the Rényi entropy that, for all ,

which together with (40), prove Items a) and b) of Theorem 2 (note that, in view of the construction of the deterministic function in Step 4 of the above algorithm, we get ).

We next prove Item c). Equality (36) is due to the Schur-concavity of the Rényi entropy, and since we have

- is an aggregation of X, i.e., the probability mass function of satisfies () where partition into m disjoint subsets as follows:

- By the assumption , it follows that for every such ;

- From (35), where the function is given by for all , and for all . Hence, is an element in the set of the probability mass functions of with which majorizes every other element from this set.

☐

Remark 7.

Remark 8.

Inequality (43) leads to the application of Theorem 1 with (see (46)). In the derivation of Theorem 2, we refer to (see (47)–(49)) rather than referring to (although, from (24), we have for all ). We do so since, for , the difference between the curves of (as a function of ) and the curve of is marginal (see the dashed and solid lines in the left plot of Figure 2), and also because the function v in (33) is expressed in a closed form whereas is subject to numerical optimization for finite n (see (15) and (16)). For this reason, Theorem 2 coincides with the result in [12] (Theorem 1) for the Shannon entropy (i.e., for ) while providing a generalization of the latter result for Rényi entropies of arbitrary positive orders α. Theorem 1, however, both strengthens the bounds in [12] (Theorem 2) for the Shannon entropy with finite cardinality n (see Remark 3), and it also generalizes these bounds to Rényi entropies of all positive orders.

Remark 9.

The minimizing probability mass function in (35) to the optimization problem (36), and the maximizing probability mass function in (30) to the optimization problem (38) are in general valid when the Rényi entropy of a positive order is replaced by an arbitrary Schur-concave function. However, the main results in (32)–(34) hold particularly for the Rényi entropy.

Remark 10.

Theorem 2 makes use of the random variables denoted by and , rather than (more simply) and respectively, because Section 5 considers i.i.d. samples and with and ; note, however, that the probability mass functions of and are different from and , respectively, and for that reason we make use of tilted symbols in the left sides of (30) and (35).

5. Information-Theoretic Applications: Non-Asymptotic Bounds for Lossless Compression and Guessing

Theorem 2 is applied in this section to derive non-asymptotic bounds for lossless compression of discrete memoryless sources and guessing moments. Each of the two subsections starts with a short background for making the presentation self-contained.

5.1. Guessing

5.1.1. Background

The problem of guessing discrete random variables has various theoretical and operational aspects in information theory (see [35,36,37,38,40,41,43,56,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81]). The central object of interest is the distribution of the number of guesses required to identify a realization of a random variable X, taking values on a finite or countably infinite set , by successively asking questions of the form “Is X equal to x?” until the value of X is guessed correctly. A guessing function is a one-to-one function , which can be viewed as a permutation of the elements of in the order in which they are guessed. The required number of guesses is therefore equal to when with .

Lower and upper bounds on the minimal expected number of required guesses for correctly identifying the realization of X, expressed as a function of the Shannon entropy , have been respectively derived by Massey [77] and by McEliece and Yu [78], followed by a derivation of improved upper and lower bounds by De Santis et al. [80]. More generally, given a probability mass function on , it is of interest to minimize the generalized guessing moment for . For an arbitrary positive , the -th moment of the number of guesses is minimized by selecting the guessing function to be a ranking function , for which if is the ℓ-th largest mass [77]. Although the tie breaking affects the choice of , the distribution of does not depend on how ties are resolved. Not only does this strategy minimize the average number of guesses, but it also minimizes the -th moment of the number of guesses for every . Upper and lower bounds on the -th moment of ranking functions, expressed in terms of the Rényi entropies, were derived by Arikan [35], Boztaş [71], followed by recent improvements in the non-asymptotic regime by Sason and Verdú [56]. Although if is small, it is straightforward to evaluate numerically the guessing moments, the benefit of bounds expressed in terms of Rényi entropies is particularly relevant when dealing with a random vector whose letters belong to a finite alphabet ; computing all the probabilities of the mass function over the set , and then sorting them in decreasing order for the calculation of the -th moment of the optimal guessing function for the elements of becomes infeasible even for moderate values of k. In contrast, regardless of the value of k, bounds on guessing moments which depend on the Rényi entropy are readily computable if for example, are independent; in which case, the Rényi entropy of the vector is equal to the sum of the Rényi entropies of its components. Arikan’s bounds in [35] are asymptotically tight for random vectors of length k as , thus providing the correct exponential growth rate of the guessing moments for sufficiently large k.

5.1.2. Analysis

We next analyze the following setup of guessing. Let be i.i.d. random variables where takes values on a finite set with . To cluster the data [82] (see also [12] (Section 3.A) and references therein), suppose that each is mapped to where is an arbitrary deterministic function (independent of the index i) with . Consequently, are i.i.d., and each takes values on a finite set with .

Let and be, respectively, the ranking functions of the random vectors and by sorting in separate decreasing orders the probabilities for , and for where ties in both cases are resolved arbitrarily. In view of Arikan’s bounds on the -th moment of ranking functions (see [35] (Theorem 1) for the lower bound, and [35] (Proposition 4) for the upper bound), since and , the following bounds hold for all :

In the following, we rely on Theorem 2 and the bounds in (63) and (64) to obtain bounds on the exponential reduction of the -th moment of the ranking function of as a result of its mapping to . First, the combination of (63) and (64) yields

In view of Theorem 2-(a) and (65), it follows that for an arbitrary and

where is a random variable whose probability mass function is given in (30). Please note that

where the first inequality in (68) holds since (see Lemma 5) and the Rényi entropy is Schur-concave.

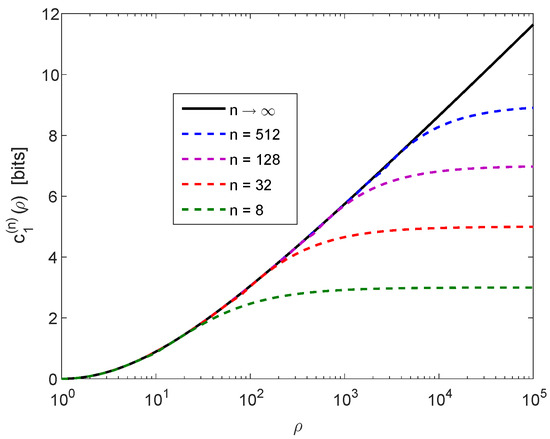

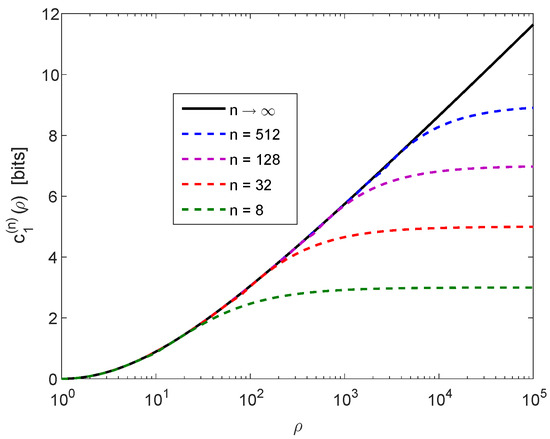

By the explicit construction of the function according to the algorithm in Steps 1–4 in the proof of Theorem 2 (based on the Huffman procedure), by setting for every , it follows from (34) and (66) that for all

where the monotonically increasing function is given in (33), and it is depicted by the solid line in the left plot of Figure 2. In view of (33), it can be shown that the linear approximation is excellent for all , and therefore for all

Hence, for sufficiently large value of k, the gap between the lower and upper bounds in (67) and (69) is marginal, being approximately equal to for all .

The following theorem summarizes our result in this section.

Theorem 3.

Let

- be i.i.d. with taking values on a set with ;

- , for every , where is a deterministic function with ;

- and be, respectively, ranking functions of the random vectors and .

Then, for every ,

- (a)

- The lower bound in (67) holds for every deterministic function ;

- (b)

- The upper bound in (69) holds for the specific , whose construction relies on the Huffman algorithm (see Steps 1–4 of the procedure in the proof of Theorem 2);

- (c)

- The gap between these bounds, for and sufficiently large k, is at most

5.1.3. Numerical Result

The following simple example illustrates the tightness of the achievable upper bound and the universal lower bound in Theorem 3, especially for sufficiently long sequences.

Example 1.

Let X be geometrically distributed restricted to with the probability mass function

where and . Assume that are i.i.d. with , and let for a deterministic function with and . We compare the upper and lower bounds in Theorem 3 for the two cases where the sequence is of length or . The lower bound in (67) holds for an arbitrary deterministic , and the achievable upper bound in (69) holds for the construction of the deterministic function (based on the Huffman algorithm) in Theorem 3. Numerical results are shown in Figure 4, providing plots of the upper and lower bounds on in Theorem 3, and illustrating the improved tightness of these bounds when the value of k is increased from 100 (left plot) to 1000 (right plot). From Theorem 3-(c), for sufficiently large k, the gap between the upper and lower bounds is less than 0.08607 bits (for all ); this is consistent with the right plot of Figure 4 where .

Figure 4.

Plots of the upper and lower bounds on in Theorem 3, as a function of , for random vectors of length (left plot) or (right plot) in the setting of Example 1. Each plot shows the universal lower bound for an arbitrary deterministic , and the achievable upper bound with the construction of the deterministic function (based on the Huffman algorithm) in Theorem 3 (see, respectively, (67) and (69)).

5.2. Lossless Source Coding

5.2.1. Background

For uniquely decodable (UD) lossless source coding, Campbell [51,83] proposed the cumulant generating function of the codeword lengths as a generalization to the frequently used design criterion of average code length. Campbell’s motivation in [51] was to control the contribution of the longer codewords via a free parameter in the cumulant generating function: if the value of this parameter tends to zero, then the resulting design criterion becomes the average code length per source symbol; on the other hand, by increasing the value of the free parameter, the penalty for longer codewords is more severe, and the resulting code optimization yields a reduction in the fluctuations of the codeword lengths.

We introduce the coding theorem by Campbell [51] for lossless compression of a discrete memoryless source (DMS) with UD codes, which serves for our analysis jointly with Theorem 2.

Theorem 4

(Campbell 1965, [51]). Consider a DMS which emits symbols with a probability mass function defined on a (finite or countably infinite) set . Consider a UD fixed-to-variable source code operating on source sequences of k symbols with an alphabet of the codewords of size D. Let be the length of the codeword which corresponds to the source sequence . Consider the scaled cumulant generating function of the codeword lengths

where

Then, for every , the following hold:

- (a)

- Converse result:

- (b)

- Achievability result: there exists a UD source code, for which

The term scaled cumulant generating function is used in view of [56] (Remark 20). The bounds in Theorem 4, expressed in terms of the Rényi entropy, imply that for sufficiently long source sequences, it is possible to make the scaled cumulant generating function of the codeword lengths approach the Rényi entropy as closely as desired by a proper fixed-to-variable UD source code; moreover, the converse result shows that there is no UD source code for which the scaled cumulant generating function of its codeword lengths lies below the Rényi entropy. By invoking L’Hôpital’s rule, one gets from (72)

Hence, by letting tend to zero in (74) and (75), it follows from (4) that Campbell’s result in Theorem 4 generalizes the well-known bounds on the optimal average length of UD fixed-to-variable source codes (see, e.g., [84] ((5.33) and (5.37))):

and (77) is satisfied by Huffman coding (see, e.g., [84] (Theorem 5.8.1)). Campbell’s result therefore generalizes Shannon’s fundamental result in [85] for the average codeword lengths of lossless compression codes, expressed in terms of the Shannon entropy.

Following the work by Campbell [51], Courtade and Verdú derived in [52] non-asymptotic bounds for the scaled cumulant generating function of the codeword lengths for -optimal variable-length lossless codes [23,86]. These bounds were used in [52] to obtain simple proofs of the asymptotic normality of the distribution of codeword lengths, and the reliability function of memoryless sources allowing countably infinite alphabets. Sason and Verdú recently derived in [56] improved non-asymptotic bounds on the cumulant generating function of the codeword lengths for fixed-to-variable optimal lossless source coding without prefix constraints, and non-asymptotic bounds on the reliability function of a DMS, tightening the bounds in [52].

5.2.2. Analysis

The following analysis for lossless source compression with UD codes relies on a combination of Theorems 2 and 4.

Let be i.i.d. symbols which are emitted from a DMS according to a probability mass function whose support is a finite set with . Similarly to Section 5.1, to cluster the data, suppose that each symbol is mapped to where is an arbitrary deterministic function (independent of the index i) with . Consequently, the i.i.d. symbols take values on a set with . Consider two UD fixed-to-variable source codes: one operating on the sequences , and the other one operates on the sequences ; let D be the size of the alphabets of both source codes. Let and denote the length of the codewords for the source sequences and , respectively, and let and denote their corresponding scaled cumulant generating functions (see (72)).

In view of Theorem 4-(b), for every , there exists a UD source code for the sequences in such that the scaled cumulant generating function of its codeword lengths satisfies (75). Furthermore, from Theorem 4-(a), we get

From (75), (78) and Theorem 2 (a) and (b), for every , there exist a UD source code for the sequences in , and a construction of a deterministic function (as specified by Steps 1–4 in the proof of Theorem 2, borrowed from [12]) such that the difference between the two scaled cumulant generating functions satisfies

where (79) holds for every UD source code operating on the sequences in with (for ) and the specific construction of as above, and in the right side of (79) is a random variable whose probability mass function is given in (30). The right side of (79) can be very well approximated (for all ) by using (70).

We proceed with a derivation of a lower bound on the left side of (79). In view of Theorem 4, it follows that (74) is satisfied for every UD source code which operates on the sequences in ; furthermore, Theorems 2 and 4 imply that, for every , there exists a UD source code which operates on the sequences in such that

where (81) is due to (39) since (for ) with an arbitrary deterministic function , and for every i; hence, from (74), (80) and (81),

We summarize our result as follows.

Theorem 5.

Let

- be i.i.d. symbols which are emitted from a DMS according to a probability mass function whose support is a finite set with ;

- Each symbol be mapped to where is the deterministic function (independent of the index i) with , as specified by Steps 1–4 in the proof of Theorem 2 (borrowed from [12]);

- Two UD fixed-to-variable source codes be used: one code encodes the sequences , and the other code encodes their mappings ; let the common size of the alphabets of both codes be D;

- and be, respectively, the scaled cumulant generating functions of the codeword lengths of the k-length sequences in (see (72)) and their mapping to .

Then, for every , the following holds for the difference between the scaled cumulant generating functions and :

- (a)

- There exists a UD source code for the sequences in such that the upper bound in (79) is satisfied for every UD source code which operates on the sequences in ;

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- The UD source codes in Items (a) and (b) for the sequences in and , respectively, can be constructed to be prefix codes by the algorithm in Remark 11.

Remark 11 (An Algorithm for Theorem 5 (d)).

A construction of the UD source codes for the sequences in and , whose existence is assured by Theorem 5 (a) and (b) respectively, is obtained by the following algorithm (of three steps) which also constructs them as prefix codes:

- (1)

- As a preparatory step, we first calculate the probability mass function from the given probability mass function and the deterministic function which is obtained by Steps 1–4 in the proof of Theorem 2; accordingly, for all . We then further calculate the probability mass functions for the i.i.d. sequences in and (see (73)); recall that the number of types in and is polynomial in k (being upper bounded by and , respectively), and the values of these probability mass functions are fixed over each type;

- (2)

- The sets of codeword lengths of the two UD source codes, for the sequences in and , can (separately) be designed according to the achievability proof in Campbell’s paper (see [51] (p. 428)). More explicitly, let ; for all , let be given bywithand let , for all , be given similarly to (83) and (84) by replacing with , and with . This suggests codeword lengths for the two codes which fulfil (75) and (80), and also, both satisfy Kraft’s inequality;

- (3)

- The separate construction of two prefix codes (a.k.a. instantaneous codes) based on their given sets of codeword lengths and , as determined in Step 2, is standard (see, e.g., the construction in the proof of [84] (Theorem 5.2.1)).

Theorem 5 is of interest since it provides upper and lower bounds on the reduction in the cumulant generating function of close-to-optimal UD source codes because of clustering data, and Remark 11 suggests an algorithm to construct such UD codes which are also prefix codes. For long enough sequences (as ), the upper and lower bounds on the difference between the scaled cumulant generating functions of the suggested source codes for the original and clustered data almost match (see (79) and (82)), being roughly equal to (with logarithms on base D, which is the alphabet size of the source codes); as , the gap between these upper and lower bounds is less than . Furthermore, in view of (76),

so, it follows from (4), (33), (79) and (82) that the difference between the average code lengths (normalized by k) of the original and clustered data satisfies

where the gap between the upper and lower bounds is equal to .

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Lemma 2

We first find the extreme values of under the assumption that . If , then P is the equiprobable distribution on and . On the other hand, if , then the minimal possible value of is obtained when P is the one-odd-mass distribution with masses equal to and a smaller mass equal to . The latter case yields .

Let , so can get any value in the interval . From Lemma 1, and , and the Schur-concavity of the Rényi entropy yields for all with . Minimizing over can be therefore restricted to minimizing over .

Appendix B. Proof of Lemma 3

The sequence is non-negative since for all . To prove (17),

where (A2) holds since is monotonically decreasing in , and (A3) is due to (5) and .

Let denote the equiprobable probability mass function on . By the identity

and since, by Lemma 2, attains its minimum over the set of probability mass functions , it follows that attains its maximum over this set. Let be the probability measure which achieves the minimum in (see (16)), then from (A4)

Let be the probability mass function which is defined on as follows:

Since by assumption , it is easy to verify from (A7) that

Appendix C. Proof of Lemma 4

From Lemma 2, the minimizing distribution of is given by where

with , and . It therefore follows that the influence of the middle probability mass of on tends to zero as . Therefore, in this asymptotic case, one can instead minimize where

with the free parameter and (so that the total mass of is equal to 1).

For , straightforward calculation shows that

and by letting , the limit of the sequence exists, and it is equal to

Let be given by

Then, , and straightforward calculation shows that the derivative vanishes if and only if

We rely here on a specialized version of the mean value theorem, known as Rolle’s theorem, which states that any real-valued differentiable function that attains equal values at two distinct points must have a point somewhere between them where the first derivative at this point is zero. By Rolle’s theorem, and due to the uniqueness of the point in (A22), it follows that . Substituting (A22) into (A20) gives (20). Taking the limit of (20) when gives the result in (21).

References

- Hardy, G.H.; Littlewood, J.E.; Pólya, G. Inequalities, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A.W.; Olkin, I.; Arnold, B.C. Inequalities: Theory of Majorization and Its Applications, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, B.C. Majorization: Here, there and everywhere. Stat. Sci. 2007, 22, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B.C.; Sarabia, J.M. Majorization and the Lorenz Order with Applications in Applied Mathematics and Economics; Statistics for Social and Behavioral Sciences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cicalese, F.; Gargano, L.; Vaccaro, U. Information theoretic measures of distances and their econometric applications. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Istanbul, Turkey, 7–12 July 2013; pp. 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, J.M. The Cauchy-Schwarz Master Class; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, R. Matrix Analysis Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, R.A.; Johnson, C.R. Matrix Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Bassat, M.; Raviv, J. Rényi’s entropy and probability of error. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1978, 24, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicalese, F.; Vaccaro, U. Bounding the average length of optimal source codes via majorization theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2004, 50, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicalese, F.; Gargano, L.; Vaccaro, U. How to find a joint probability distribution with (almost) minimum entropy given the marginals. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Aachen, Germany, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 2178–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Cicalese, F.; Gargano, L.; Vaccaro, U. Bounds on the entropy of a function of a random variable and their applications. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 2220–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicalese, F.; Vaccaro, U. Maximum entropy interval aggregations. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Vail, CO, USA, 17–20 June 2018; pp. 1764–1768. [Google Scholar]

- Harremoës, P. A new look on majorization. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory and Its Applications, Parma, Italy, 10–13 October 2004; pp. 1422–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.W.; Yeung, R.W. The interplay between entropy and variational distance. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2010, 56, 5906–5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.W.; Verdú, S. On the interplay between conditional entropy and error probability. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2010, 56, 5930–5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.W.; Verdú, S. Convexity/concavity of the Rényi entropy and α-mutual information. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Hong Kong, China, 14–19 June 2015; pp. 745–749. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, H. Majorization, entropy and paired comparisons. Ann. Stat. 1988, 16, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, H. Majorization and divergence. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1990, 148, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, H. Characterization of the smooth Rényi entropy using majorization. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Information Theory Workshop, Seville, Spain, 9–13 September 2013; pp. 604–608. [Google Scholar]

- Puchala, Z.; Rudnicki, L.; Zyczkowski, K. Majorization entropic uncertainty relations. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sason, I.; Verdú, S. Arimoto-Rényi conditional entropy and Bayesian M-ary hypothesis testing. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdú, S. Information Theory, 2018; in preparation.

- Witsenhhausen, H.S. Some aspects of convexity useful in information theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1980, 26, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, T. Schur-convexity on generalized information entropy and its applications. In Information Computing and Applications; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 7030, pp. 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Inaltekin, H.; Hanly, S.V. Optimality of binary power control for the single cell uplink. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2012, 58, 6484–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorshweick, E.; Bosche, H. Majorization and matrix-monotone functions in wireless communications. Found. Trends Commun. Inf. Theory 2006, 3, 553–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar, D.P.; Jiang, Y. MIMO transceiver design via majorization theory. Found. Trends Commun. Inf. Theory 2006, 3, 331–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roventa, I. Recent Trends in Majorization Theory and Optimization: Applications to Wireless Communications; Editura Pro Universitaria & Universitaria Craiova: Bucharest, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, A.; Jorswieck, E.A. Applications of majorization theory in space-time cooperative communications. In Cooperative Communications for Improved Wireless Network Transmission: Framework for Virtual Antenna Array Applications; Information Science Reference; Uysal, M., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 429–470. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath, P.; Anantharam, V. Optimal sequences and sum capacity of synchronous CDMA systems. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1999, 45, 1984–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, P.; Anantharam, V.; Tse, D.N.C. Optimal sequences, power control, and user capacity of synchronous CDMA systems with linear MMSE multiuser receivers. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1999, 45, 1968–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, P.; Anantharam, V. Optimal sequences for CDMA under colored noise: A Schur-saddle function property. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2002, 48, 1295–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rényi, A. On measures of entropy and information. In Proceedings of the 4th Berkeley Symposium on Probability Theory and Mathematical Statistics, Berkeley, CA, USA, 8–9 August 1961; pp. 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Arikan, E. An inequality on guessing and its application to sequential decoding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1996, 42, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, E.; Merhav, N. Guessing subject to distortion. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1998, 44, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, E.; Merhav, N. Joint source-channel coding and guessing with application to sequential decoding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1998, 44, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, A.; Shayevitz, O. Reducing guesswork via an unreliable oracle. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 6941–6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzuoka, S. On the conditional smooth Rényi entropy and its applications in guessing and source coding. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1810.09070. [Google Scholar]

- Merhav, N.; Arikan, E. The Shannon cipher system with a guessing wiretapper. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1999, 45, 1860–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, R. Guessing based on length functions. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Nice, France, 24–29 June 2007; pp. 716–719. [Google Scholar]

- Salamatian, S.; Beirami, A.; Cohen, A.; Médard, M. Centralized versus decentralized multi-agent guesswork. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Aachen, Germany, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 2263–2267. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan, R. Guessing under source uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2007, 53, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracher, A.; Lapidoth, A.; Pfister, C. Distributed task encoding. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Aachen, Germany, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 1993–1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bunte, C.; Lapidoth, A. Encoding tasks and Rényi entropy. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2014, 60, 5065–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayevitz, O. On Rényi measures and hypothesis testing. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 31 July–5 August 2011; pp. 800–804. [Google Scholar]

- Tomamichel, M.; Hayashi, M. Operational interpretation of Rényi conditional mutual information via composite hypothesis testing against Markov distributions. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Barcelona, Spain, 10–15 July 2016; pp. 585–589. [Google Scholar]

- Harsha, P.; Jain, R.; McAllester, D.; Radhakrishnan, J. The communication complexity of correlation. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2010, 56, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Verdú, S. Rejection sampling and noncausal sampling under moment constraints. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Vail, CO, USA, 17–22 June 2018; pp. 1565–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Tan, V.Y.F. Wyner’s common information under Rényi divergence measures. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 3616–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.L. A coding theorem and Rényi’s entropy. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtade, T.; Verdú, S. Cumulant generating function of codeword lengths in optimal lossless compression. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Honolulu, HI, USA, 29 June–4 July 2014; pp. 2494–2498. [Google Scholar]

- Courtade, T.; Verdú, S. Variable-length lossy compression and channel coding: Non-asymptotic converses via cumulant generating functions. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Honolulu, HI, USA, 29 June–4 July 2014; pp. 2499–2503. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, M.; Tan, V.Y.F. Equivocations, exponents, and second-order coding rates under various Rényi information measures. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2017, 63, 975–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzuoka, S. On the smooth Rényi entropy and variable-length source coding allowing errors. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Barcelona, Spain, 10–15 July 2016; pp. 745–749. [Google Scholar]

- Sason, I.; Verdú, S. Improved bounds on lossless source coding and guessing moments via Rényi measures. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 4323–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, V.Y.F.; Hayashi, M. Analysis of ramaining uncertainties and exponents under various conditional Rényi entropies. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 3734–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, H. Coding theorems using Rényi information measures. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Twenty-Third National Conference on Communications, Chennai, India, 2–4 March 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Csiszár, I. Generalized cutoff rates and Rényi information measures. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1995, 41, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyanskiy, Y.; Verdú, S. Arimoto channel coding converse and Rényi divergence. In Proceedings of the Forty-Eighth Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control and Computing, Monticello, IL, USA, 29 September–1 October 2010; pp. 1327–1333. [Google Scholar]

- Sason, I. On the Rényi divergence, joint range of relative entropies, and a channel coding theorem. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2016, 62, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Tan, V.Y.F. Rényi resolvability and its applications to the wiretap channel. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information Theoretic Security, Hong Kong, China, 29 November–2 December 2017; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 10681, pp. 208–233. [Google Scholar]

- Arimoto, S. On the converse to the coding theorem for discrete memoryless channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1973, 19, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimoto, S. Information measures and capacity of order α for discrete memoryless channels. In Proceedings of the 2nd Colloquium on Information Theory, Keszthely, Hungary, 25–30 August 1975; Csiszár, I., Elias, P., Eds.; Colloquia Mathematica Societatis Janós Bolyai: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 16, pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dalai, M. Lower bounds on the probability of error for classical and classical-quantum channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2013, 59, 8027–8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leditzky, F.; Wilde, M.M.; Datta, N. Strong converse theorems using Rényi entropies. J. Math. Phys. 2016, 57, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosonyi, M.; Ogawa, T. Quantum hypothesis testing and the operational interpretation of the quantum Rényi relative entropies. Commun. Math. Phys. 2015, 334, 1617–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simic, S. Jensen’s inequality and new entropy bounds. Appl. Math. Lett. 2009, 22, 1262–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelineck, F.; Schneider, K.S. On variable-length-to-block coding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1972, 18, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completness; W. H. Freedman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Boztaş, S. Comments on “An inequality on guessing and its application to sequential decoding”. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1997, 43, 2062–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracher, A.; Hof, E.; Lapidoth, A. Guessing attacks on distributed-storage systems. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Hong-Kong, China, 14–19 June 2015; pp. 1585–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, M.M.; Duffy, K.R. Guesswork, large deviations, and Shannon entropy. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2013, 59, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawal, M.K.; Sundaresan, R. Guessing revisited: A large deviations approach. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2011, 57, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawal, M.K.; Sundaresan, R. The Shannon cipher system with a guessing wiretapper: General sources. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2011, 57, 2503–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huleihel, W.; Salamatian, S.; Médard, M. Guessing with limited memory. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Aachen, Germany, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 2258–2262. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, J.L. Guessing and entropy. In Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Trondheim, Norway, 27 June–1 July 1994; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- McEliece, R.J.; Yu, Z. An inequality on entropy. In Proceedings of the 1995 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Whistler, BC, Canada, 17–22 September 1995; p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, C.E.; Sullivan, W.G. Rényi entropy, guesswork moments and large deviations. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2004, 50, 2794–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, A.; Gaggia, A.G.; Vaccaro, U. Bounds on entropy in a guessing game. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2001, 47, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yona, Y.; Diggavi, S. The effect of bias on the guesswork of hash functions. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Aachen, Germany, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 2253–2257. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, G.; Ma, C.; Wu, J. Data Clustering: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications; ASA-SIAM Series on Statistics and Applied Probability; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, L.L. Definition of entropy by means of a coding problem. Probab. Theory Relat. Field 1966, 6, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoyiannis, I.; Verdú, S. Optimal lossless data compression: Non-asymptotics and asymptotics. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2014, 60, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erven, T.; Harremoës, P. Rényi divergence and Kullback-Leibler divergence. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2014, 60, 3797–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).