Abstract

In this paper, we combine the two universalisms of thermodynamics and dynamical systems theory to develop a dynamical system formalism for classical thermodynamics. Specifically, using a compartmental dynamical system energy flow model we develop a state-space dynamical system model that captures the key aspects of thermodynamics, including its fundamental laws. In addition, we establish the existence of a unique, continuously differentiable global entropy function for our dynamical system model, and using Lyapunov stability theory we show that the proposed thermodynamic model has finite-time convergent trajectories to Lyapunov stable equilibria determined by the system initial energies. Finally, using the system entropy, we establish the absence of Poincaré recurrence for our thermodynamic model and develop clear and rigorous connections between irreversibility, the second law of thermodynamics, and the entropic arrow of time.

1. Introduction

The arrow of time and the second law of thermodynamics is one of the most famous and controversial problems in physics. The controversy between the course of time (i.e., a timeless universe) and the arrow of time (i.e., a constantly changing universe) can be traced back to the famous dialogues between the ancient Greek philosophers Parmenides and Herakleitos on being and becoming. Parmenides, like Einstein, insisted that time is an illusion, that there is nothing new, and that everything is (being) and will forever be. This statement is, of course, paradoxical since the status quo changed after Parmenides wrote his famous poem. Herakleitos’ aphorism on the other hand is predicated on change (becoming); namely, the universe is in a constant state of flux and nothing is stationary—T. Furthermore, Herakleitos goes on to state that the universe evolves in accordance with its own laws which are the only unchangeable things in the universe (i.e., universal conservation and nonconservation laws). His statements that everything is in a state of flux—T—and that man cannot step into the same river twice, because neither the man nor the river is the same——give the earliest perception of irreversibility of nature and the universe along with time’s arrow. The idea that the universe is in constant change and there is an underlying order to this change—the Logos ()—postulates the existence of entropy as a physical property of matter permeating the whole of nature and the universe.

Herakleitos’ statements are completely consistent with the laws of thermodynamics which are intimately connected to the irreversibility of dynamical processes in nature. In addition, his aphorisms go beyond the worldview of thermodynamics and have deep relativistic ramifications to the space-time fabric of the cosmos. Specifically, Herakleitos’ profound statement—All matter is exchanged for energy, and energy for all matter ()—is a statement of the law of conservation of mass-energy and is a precursor to the principle of relativity. In describing the nature of the universe Herakleitos postulates that nothing can be created out of nothing, and nothing that disappears ceases to exist. This totality of forms, or mass-energy equivalence, is eternal and unchangeable in a constantly changing universe.

Energy is a concept that underlies our understanding of all physical phenomena and is a measure of the ability of a dynamical system to produce changes (motion) in its own system state as well as changes in the system states of its surroundings. Thermodynamics is a physical branch of science that deals with laws governing energy flow from one body to another and energy transformations from one form to another. These energy flow laws are captured by the fundamental principles known as the first and second laws of thermodynamics. The first law of thermodynamics gives a precise formulation of the equivalence between heat and work and states that among all system transformations, the net system energy is conserved. Hence, energy cannot be created out of nothing and cannot be destroyed; it can merely be transformed from one form to another.

The law of conservation of energy is not a mathematical truth, but rather the consequence of an immeasurable culmination of observations over the chronicle of our civilization, and is a fundamental axiom of the science of heat. The first law does not tell us whether any particular process can actually occur, that is, it does not restrict the ability to convert work into heat or heat into work, except that energy must be conserved in the process. The second law of thermodynamics asserts that, while the system energy is always conserved, it will be degraded to a point where it cannot produce any useful work. Hence, it is impossible to extract work from heat without at the same time discarding some heat, giving rise to an increasing quantity known as entropy.

As discussed in the recent monograph [1], there have been many different presentations of classical thermodynamics with varying hypotheses and conclusions. To exacerbate matters, the careless and considerable differences in the definitions of two of the key notions of thermodynamics—namely, the notions of reversibility and irreversibility—have contributed to the widespread confusion and lack of clarity in the exposition of classical thermodynamics over the past one and a half centuries. For example, the concept of a reversible process as defined by Clausius, Kelvin, Planck, and Carathéodory has very different meanings. In particular, Clausius defines a reversible (umkehrbar) process as a slowly varying process wherein successive states of this process differ by infinitesimals from the equilibrium system states. Such system transformations are commonly referred to as quasistatic transformations in the thermodynamic literature.

Alternatively, Kelvin’s notions of reversibility involve the ability of a system to completely recover its initial state from the final system state. Planck introduced several notions of reversibility. His main notion of reversibility is one of complete reversibility and involves recoverability of the original state of the dynamical system while at the same time restoring the environment to its original condition. Unlike Clausius’ notion of reversibility, Kelvin’s and Planck’s notions of reversibility do not require the system to exactly retrace its original trajectory in reverse order. Carathéodory’s notion of reversibility involves recoverability of the system state in an adiabatic process [2,3,4], resulting in yet another definition of thermodynamic reversibility. These subtle distinctions of (ir)reversibility are often unrecognized in the thermodynamic literature. Notable exceptions to this fact include [1,5,6], with [1,6] providing an excellent exposition of the relation between irreversibility, the second law of thermodynamics, and the arrow of time.

The arrow of time [7] remains one of physics’ most perplexing enigmas [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Even though time is one of the most familiar concepts humankind has ever encountered, it is the least understood. Puzzling questions of time’s mysteries have remained unanswered throughout the centuries—questions such as, Where does time come from? What would our universe look like without time? Can there be more than one dimension to time? Is time truly a fundamental appurtenance woven into the fabric of the universe, or is it just a useful edifice for organizing our perception of events? Why is the concept of time hardly ever found in the most fundamental physical laws of nature and the universe? Can we go back in time? And if so, can we change past events?

Human experience perceives time flow as unidirectional; the present is forever flowing toward the future and away from a forever fixed past. Many scientists have attributed this emergence of the direction of time flow to the second law of thermodynamics due to its intimate connection to the irreversibility of dynamical processes [14]. In this regard, thermodynamics is disjoint from Newtonian and Hamiltonian mechanics (including Einstein’s relativistic and Schrödinger’s quantum extensions), since these theories are invariant under time reversal, that is, they make no distinction between one direction of time and the other. Such theories possess a time-reversal symmetry, wherein, from any given moment of time, the governing laws treat past and future in exactly the same way [15]. For example, a film run backward of a harmonic oscillator over a full period or a planet orbiting the Sun would represent possible events. In contrast, a film run backward of water in a glass coalescing into a solid ice cube or ashes self-assembling into a log of wood would immediately be identified as an impossible event. Over the centuries, many philosophers and scientists shared the views of a Parmenidean frozen river time theory. However, since the advent of the science of thermodynamics in the 19th century, philosophy and science took a different point of view with the writings of Hegel, Bergson, Heidegger, Clausius, Kelvin, and Boltzmann; one involving time as our existential dimension. The idea that the second law of thermodynamics provides a physical foundation for the arrow of time has been postulated by many authors [9,16,17]. However, a convincing argument of this claim has never been given [1,6,10,12,18].

In this paper, we use energy flow compartmental dynamical system theory to place thermodynamics on a system-theoretic foundation so as to harmonize it with classical mechanics. In particular, we develop a novel formulation of thermodynamics that can be viewed as a moderate-sized system theory as compared to statistical thermodynamics. This middle-ground theory involves deterministic large-scale dynamical system models that bridge the gap between classical and statistical thermodynamics. Specifically, since thermodynamic models are concerned with energy flow among subsystems, we use a state space formulation to develop a nonlinear compartmental dynamical system model that is characterized by energy conservation laws capturing the exchange of energy between coupled macroscopic subsystems. Furthermore, using graph-theoretic notions, we state two thermodynamic axioms consistent with the zeroth and second laws of thermodynamics, which ensure that our large-scale dynamical system model gives rise to a thermodynamically consistent energy flow model. Specifically, using a large-scale dynamical systems theory perspective for thermodynamics, we show that our compartmental dynamical system model leads to a precise formulation of the equivalence between work energy and heat in a large-scale dynamical system.

Next, we give a deterministic definition of entropy for a large-scale dynamical system that is consistent with the classical thermodynamic definition of entropy, and we show that it satisfies a Clausius-type inequality leading to the law of entropy nonconservation. However, unlike classical thermodynamics, wherein entropy is not defined for arbitrary states out of equilibrium, our definition of entropy holds for nonequilibrium dynamical systems. Then, using Lyapunov stability theory, we show that in the absence of energy exchange with the environment our thermodynamically consistent large-scale nonlinear dynamical system model possesses a continuum of equilibria and is semistable, that is, it has subsystem energies convergent to Lyapunov stable energy equilibria determined by the large-scale system’s initial subsystem energies.

For our thermodynamically consistent dynamical system model, we further establish the existence of a unique continuously differentiable global entropy function for all equilibrium and nonequilibrium states. Using this global entropy function, we go on to establish a clear connection between thermodynamics and the arrow of time. Specifically, we rigorously show the state irrecoverability and hence the state irreversibility [6,19] nature of thermodynamics. In particular, we show that for every nonequilibrium system state and corresponding system trajectory of our thermodynamically consistent large-scale nonlinear dynamical system, there does not exist a state such that the corresponding system trajectory completely recovers the initial system state of the dynamical system and at the same time restores the energy supplied by the environment back to its original condition. This, along with the existence of a global strictly increasing entropy function on every nontrivial system trajectory, gives a clear time-reversal asymmetry characterization of thermodynamics, establishing the emergence of the direction of time flow. Finally, since for every physical system energy and temperature equipartition is achieved in finite time rather than merely asymptotically, we merge the theories of semistability and finite-time stability developed in [20,21,22] to develop a mathematically rigorous framework for finite-time thermodynamics.

2. Dynamical System Model

In this section, we establish notation and provide a general axiomatic definition of a dynamical system. The notation used in this paper is fairly standard. Specifically, denotes the set of real numbers, (respectively, ) denotes the set of nonnegative (respectively, positive) integers, denotes the set of column vectors, denotes transpose, and or I denotes the identity matrix. For we write (respectively, ) to indicate that every component of z is nonnegative (respectively, positive). In this case we say that z is nonnegative or positive, respectively. Furthermore, let and denote the nonnegative and positive orthants of , that is, if , then and are equivalent, respectively, to and . Finally, let , , and denote the boundary, the interior, and the closure of the set , respectively.

We write ‖ · ‖ for the Euclidean vector norm, for the Fréchet derivative of V at z, , , , for the open ball centered at α with radius ε, and as to denote that approaches the set (that is, for each there exists such that dist for all , where dist). Finally, the notions of openness, convergence, continuity, and compactness that we use throughout the paper refer to the topology generated on by the norm .

Next, we define a dynamical system as a precise mathematical object satisfying a set of axioms. For this definition, let denote an input space that consists of bounded continuous U-valued functions on . The set contains the set of input values, that is, at any time , . The space is assumed to be closed under the shift operator, that is, if , then the function defined by is contained in for all . Furthermore, we let denote an output space that consists of continuous Y-valued functions on . The set contains the set of output values, that is, each value of , . The space is assumed to be closed under the shift operator, that is, if , then the function defined by is contained in for all .

Definition 2.1

Let be a Euclidean space with norm ∥ · ∥. A dynamical system on is the octuple , where and are such that the following axioms hold:

- (i)

- (Continuity): is jointly continuous for all .

- (ii)

- (Consistency): for all , , and .

- (iii)

- (Determinism): for all , , and , satisfying , .

- (iv)

- (Semigroup property): for all , , and τ, .

- (v)

- (Read-out map): For every , , and , there exists such that for all .

We denote the dynamical system by . Furthermore, we refer to the map as the flow or trajectory of corresponding to , and for a given , , , we refer to as an initial condition of . Given , we denote the map by . Hence, for a fixed the set of mappings defined by for every and gives the flow of . In particular, if is a collection of initial conditions such that , then the flow is the motion of all points or, equivalently, the image of under the flow , that is, , where and . Alternatively, if the initial condition is fixed and we let and , then the mapping defines the solution curve or trajectory of the dynamical system . Hence, the mapping generates a graph in identifying the trajectory corresponding to the motion along a curve through the point with input in a subset of the state space. Given and , we denote the map by .

In general, the output of depends on both the present input of and the past history of . Hence, the output at some time depends on the state of , which effectively serves as an information storage (memory) of past history. Furthermore, the determinism axiom ensures that the state and thus the output before some time are not influenced by the values of the output after time . Hence, future inputs to do not affect past and present outputs of . This is simply a statement of causality that holds for all physical systems. Finally, we note that the read-out map is memoryless in the sense that outputs only depend on the instantaneous (present) values of the state and input.

The dynamical system is isolated if . Furthermore, an equilibrium point of the isolated dynamical system is a point satisfying . An equilibrium point of the isolated dynamical system is Lyapunov stable with respect to the positively invariant set if, for every relatively open subset of containing , there exists a relatively open subset of containing such that for all , where . An equilibrium point of the isolated dynamical system is called semistable if it is Lyapunov stable and there exists a relatively open subset of containing such that for all initial conditions in , the trajectory of converges to a Lyapunov stable equilibrium point, that is, as , where is a Lyapunov stable equilibrium point of and . The isolated dynamical system is said to be semistable if every equilibrium point of is semistable.

Finally, for a given interval , where , let denote the set of all possible trajectories of given by

where denotes the solution curve or trajectory of for a given fixed initial condition and input .

3. Reversibility, Irreversibility, Recoverability and Irrecoverability

The notions of reversibility, irreversibility, recoverability, and irrecoverability all play a central role in thermodynamic processes. In this section, we define the notions of R-state reversibility, state reversibility, and state recoverability of a dynamical system . R-state reversibility concerns the existence of a system state with the property that a transformed system trajectory through an involution operator R is an image of a given system trajectory of on a specified finite time interval. State reversibility concerns the existence of a system state with the property that the resulting system trajectory is the time-reversed image of a given system trajectory of on a specified finite time interval. Finally, state recoverability concerns the existence of a system state with the property that the resulting system trajectory completely recovers the initial state of the dynamical system over a finite time interval.

For the results of this section we use the definition of a dynamical system given in Definition 2.1. We start by establishing the notions of (ir)reversibility and (ir)recoverability of a dynamical system defined on a Euclidean space .

Definition 3.1

Consider the dynamical system defined on . Let be an involutive operator (that is, , where denotes the identity operator on ) and let , where . The function is an R-reversed trajectory of if there exist an input and a continuous, strictly increasing function such that , , and

Definition 3.2

Consider the dynamical system defined on . Let be an involutive operator, let , and let , where . is an R-reversible trajectory of if there exists an input such that and

where denotes the read-out map for the R-reversed trajectory of . Furthermore, is an R-state reversible dynamical system if for every , , where is an R-reversible trajectory of .

In classical mechanics, R is a transformation that reverses the sign of all system momenta and magnetic fields, whereas in classical reversible thermodynamics R can be taken to be the identity operator. Note that if , then , where is an -reversible trajectory or, simply, is a reversible trajectory. Furthermore, we say that is a state reversible dynamical system if and only if for every , , where is a reversible trajectory of . Note that unlike state reversible systems, R-state reversible dynamical systems need not retrace every stage of the original system trajectory in reverse order, nor is it necessary for the dynamical system to recover the initial system state.

The function in Definition 3.2 is a generalized power supply from the environment to the dynamical system through the system’s input-output ports . Hence, Equation (3) ensures that the total generalized energy supplied to the dynamical system by the environment is returned to the environment over a given R-reversible trajectory starting and ending at any given (not necessarily the same) state . Furthermore, Equation (3) ensures that a reversible process completely restores the original dynamic state of a system and at the same time restores the energy supplied by the environment back to its original condition. The following result provides sufficient conditions for the existence of an R-reversible trajectory of a nonlinear dynamical system , and hence, establishes sufficient conditions for R-state reversibility of the dynamical system .

Theorem 3.1

Consider the dynamical system defined on . Let be an involutive operator, and let , where . Assume there exist a continuous function and a function such that , , and for every and all , , ,

Furthermore, assume there exists such that for all , , , and , , Equation (4) holds as a strict inequality. If is an R-reversible trajectory of , then , .

Proof.

Let , where , be an R-reversible trajectory of so that there exists such that . Suppose, ad absurdum, there exists such that . Now, it follows that there exists an interval such that for ,

which further implies that

Next, since , where , it follows that

Now, adding Equations (6) and (7), using the definition of , using the fact that , , and using Equation (3) yields

which is a contradiction. Hence, , . ☐

It is important to note that since in Theorem 3.1 is not sign definite, Theorem 3.1 also holds for the case where the inequality in Equation (4) is reversed. The following corollary to Theorem 3.1 is immediate.

Corollary 3.1

Consider the dynamical system defined on . Let be an involutive operator, let , and let , where . Assume there exists a continuous function such that , , and for , , is a strictly increasing (respectively, decreasing) function of time. If is an R-reversible trajectory of , then , .

Proof.

The proof is a direct consequence of Theorem 3.1 with and the fact that Theorem 3.1 also holds for the case when the inequality in Equation (4) is reversed. ☐

It follows from Corollary 3.1 that if, for a given dynamical system , there exists an R-reversible trajectory of , then there does not exist a function of the state of the system that strictly decreases or strictly increases in time on any trajectory of lying in . In this case, the existence of a completely ordered time set having a topological structure involving a closed set homeomorphic to the real line cannot be established. Such systems, which include lossless Newtonian and Hamiltonian systems, are time-reversal symmetric and hence lack an inherent time direction. However, that is not the case with thermodynamic systems.

Next, we present a notion of state recoverability of a dynamical system .

Definition 3.3

Consider the dynamical system defined on . Let , and let , where . is a recoverable trajectory of if there exist and such that ,

and

where denotes the read-out map for the trajectory . Furthermore, is a state recoverable dynamical system if for every , is a recoverable trajectory of .

It follows from the definition of state recoverability that the way in which the initial dynamical system state is restored may be chosen freely so long as Equation (9) is satisfied. Hence, unlike R-state reversibility, it is not necessary for the dynamical system to recover the initial state of the system through an involutive transformation of the system trajectory. Furthermore, unlike state reversibility, it is not necessary for the dynamical system to retrace every stage of the original trajectory in the reverse order. However, Equation (9) ensures that the recoverable process completely restores the original dynamic state and at the same time restores the energy supplied by the environment back to its original condition. This notion of recoverability is closely related to Planck’s notion of complete reversibility, wherein the initial system state is restored in the totality of nature (“die gesamte Natur"). The following result provides a sufficient condition for the existence of a recoverable trajectory of a nonlinear dynamical system , and hence, establishes sufficient conditions for state recoverability of .

Theorem 3.2

Consider the dynamical system defined on . Let , where . Assume there exist a continuous function and a function such that for every and all , , ,

Furthermore, assume there exists such that for all , , , and , , Equation (10) holds as a strict inequality. If is a recoverable trajectory of , then , .

Proof.

Let , where , be a recoverable trajectory of so that there exist and such that . Suppose, ad absurdum, there exists such that . Now, it follows that there exists an interval such that for ,

which further implies that

Next, it follows from Equation (10) with that

Now, adding Equations (12) and (13), using the definition of , and using Equation (9) yields

which is a contradiction. Hence, , . ☐

The following corollary to Theorem 3.2 is immediate.

Corollary 3.2

Consider the dynamical system defined on . Let , and let , where . Assume there exists a continuous function such that for , , is a strictly increasing (respectively, decreasing) function of time. If is a recoverable trajectory of , then , .

Proof.

The proof is a direct consequence of Theorem 3.2 with and the fact that Theorem 3.2 also holds for the case when the inequality in Equation (10) is reversed. ☐

As in the case of R-state reversibility and state reversibility, state recoverability can be used to establish a connection between a dynamical system evolving on a manifold and the arrow of time. However, in the case of state recoverability, the recoverable dynamical system trajectory need not involve an involutive transformation of the system trajectory, nor is it required to retrace the original system trajectory in recovering the original dynamic state. It should be noted here that state recoverability is not implied by the concepts of reachability and controllability, which play a central role in control theory [1]. For example, one might envision, albeit with a considerable stretch of the imagination, perfectly controlled inputs that could reassemble a broken egg or even fuse water into solid cubes of ice. However, in all such cases, an external source of energy from the environment would be required to operate such an immaculate state recoverable mechanism and would violate Equation (9). Clearly, state recoverability is a weaker notion than that of state reversibility since state reversibility implies state recoverability; the converse, however, is not true. Conversely, state irrecoverability is a logically stronger notion than state irreversibility since state irrecoverability implies state irreversibility. However, as we see in Section 8, these notions are equivalent for thermodynamic systems.

4. Reversible Dynamical Systems, Volume-Preserving Flows and Poincaré Recurrence

The notion of R-state reversibility introduced in Section 3 is one of the fundamental symmetries that arises in natural science. This notion can also be characterized by the flow of a dynamical system. In particular, consider the dynamical system given by

where , , is the system state vector, is an open subset of , is locally Lipschitz continuous on , and , , is the maximal interval of existence for the solution of Equation (14). Note that since is locally Lipschitz continuous on , it follows from Theorem 3.1 of ([23], p. 18) that the solution to Equation (14) is unique for every initial condition in and jointly continuous in t and . In this case, the semigroup property , , and the continuity of on , , hold. Given , we denote the flow of Equation (14) by for , and given , we denote the trajectory of Equation (14) by . Now, in terms of the flow of Equation (14), the consistency and semigroup properties of Equation (14) can be equivalently written as and , where “∘" denotes the composition operator. Next, it follows from continuity of solutions and the semigroup property that the map is a continuous function with a continuous inverse . Thus, , , generates a one-parameter family of homeomorphisms on forming a commutative group under composition.

To show that R-state reversibility can be characterized by the flow of Equation (14), let be a continuous map of Equation (14) such that

Now, it follows from Equation (15) that

Equation (16), with satisfying Equation (15), defines an R-reversed trajectory of Equation (14) in the sense of Definition 3.1 with .

In the context of classical mechanics involving the configuration manifold (space of generalized positions) , with governing equations given by

where denotes generalized system positions, denotes generalized system momenta, is the system Hamiltonian given by , is the system Lagrangian, [24,25] and , the reversing symmetry is such that and satisfies Equation (15). In this case, is an involution. This implies that if , , is a solution to Equations (17) and (18), then , , is also a solution to Equations (17) and (18) with initial condition . In the configuration space this clearly shows the time-reversal nature of lossless mechanical systems.

Reversible dynamical systems tend to exhibit a phenomenon known as Poincaré recurrence [26]. Poincaré recurrence states that if a dynamical system has a fixed total energy that restricts its dynamics to bounded subsets of its state space, then the dynamical system will eventually return arbitrarily close to its initial system state infinitely often. More precisely, Poincaré [27] established the fact that if the flow of a dynamical system preserves volume and has only bounded orbits, then for each open set there exist orbits that intersect the set infinitely often. In order to state the Poincaré recurrence theorem, the following definitions are needed.

Definition 4.1

Let be a bounded set. The volume of is defined as

where the integration in Equation (19) is the Lebesgue integral over .

Definition 4.2

Let be a bounded set. A map , where , is volume preserving if for every , the volume of is equal to the volume of .

The following theorem, known as Liouville’s theorem [26], establishes sufficient conditions for volume-preserving flows. For the statement of this theorem, consider the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) and define the divergence of by

where ∇ denotes the nabla operator, denotes the dot product in , and denotes the ith component of x.

Theorem 4.1

Proof.

Let be a compact set such that its image at time t under the mapping is given by . In addition, let denote an infinitesimal surface element of the boundary of the set and let , denote an outward normal vector to the boundary of . Then the change in volume of at is given by

which, using the divergence theorem, implies that

Hence, if , then is a volume-preserving map. ☐

Volume preservation is the key conservation law underlying statistical mechanics. The flows of volume-preserving dynamical systems belong to one of the Lie pseudogroups [28] of diffeomorphisms. These systems arise in incompressible fluid dynamics, classical mechanics, and acoustics. Next, we state the well-known Poincaré recurrence theorem. For this result, let , denote the n-time composition operator of with itself and define .

Theorem 4.2

Let be an open bounded set, and let be a continuous, volume-preserving bijective (one-to-one and onto) map. Then for every open set , there exists such that . Furthermore, there exists a point which returns to , that is, for some .

Proof.

The proof of this result is standard; see for example ([26], p. 72). For completeness of exposition, however, we provide a proof here. First, note that the images , , under the mapping of the neighborhood have the same volume and are all contained in . Next, define the union of all the images of by

Since the volume of a union of disjoint sets is the sum of the individual set volumes, it follows that if are disjoint, then . However, and is a bounded set by assumption. Hence, there exist , with , such that . Now, applying the inverse to this relation l times and using the fact that is a bijective map, it follows that . Thus, , where . Hence, there exists a point such that . ☐

The next result establishes the existence of a point x in such that for some sequence , with as , under a continuous, volume-preserving bijective mapping which maps a bounded region of a Euclidean space onto itself. Hence, x returns infinitely often to any open neighborhood of itself under the mapping .

Theorem 4.3

Let be an open bounded set, and let be a continuous, volume-preserving bijective map. Then for every open neighborhood , there exists a point such that for some sequence , with as . Hence, returns to infinitely often, that is, there exists a sequence , with as , such that for all .

Proof.

Let be an open set, and let be such that for some and . Applying Theorem 4.2, with replaced by , it follows that there exists such that , which implies that . Now, let be such that for some and . Repeating the above arguments it follows that there exists , , such that and . Repeating this process recursively, it follows that there exist sequences and , with as , as , and , , such that , , and , where for some and where and . Now, since , , it follows from the Cantor intersection theorem ([29], p. 56) that . Furthermore, since as , it follows that is a singleton. Next, let , and since for every , , it follows that , . Now, note that for all , which implies that , . Hence, since as , it follows that . ☐

The next theorem strengthens Poincaré’s theorem by showing that for every open neighborhood of , there exists a subset of that is dense [30] in so that almost every moving point in returns repeatedly to the vicinity of its initial position under a continuous, volume-preserving bijective mapping which maps the bounded region onto itself.

Theorem 4.4

Let be an open bounded set, and let be a continuous, volume-preserving bijective map. Then for every open neighborhood , there exists a dense subset such that for every point , for some sequence , with as .

Proof.

Let be an open neighborhood and define by

Now, let and let be a strictly decreasing positive sequence with as and . It follows from Theorem 4.3 that for every , there exists such that for some sequence , with as , which implies that , . Next, since , it follows that , which implies that , and hence, is a dense subset of . ☐

It follows from Theorem 4.4 that almost every point in will return infinitely many times to any open neighborhood of itself under a continuous, volume-preserving bijective mapping which maps a bounded region of a Euclidean space onto itself. The following theorem provides several equivalent statements for establishing Poincaré recurrence.

Theorem 4.5

Let be an open bounded set, and let be a continuous, bijective map. Then the following statements are equivalent:

- (i)

- For every open set , there exists a dense subset such that, for every point , for some sequence , with as .

- (ii)

- For every open set , there exists a point such that for some sequence , with as .

- (iii)

- For every open set , there exists a point which returns to infinitely often, that is, , , for some sequence , with as .

- (iv)

- For every open set , there exists a point which returns to , that is, for some .

- (v)

- For every open set , there exists such that .

Proof.

The implication (i) implies (ii) follows trivially and the proof of (ii) implies (i) is identical to that of Theorem 4.4. The implications (ii) implies (iii), (iii) implies (iv), and (iv) implies (v) follow trivially. The proof of (v) implies (ii) is identical to that of Theorem 4.3. ☐

Note that it follows from Theorems 4.2, 4.3, and 4.4 that a continuous, bijective map exhibits Poincaré recurrence (that is, the statements in Theorem 4.5 hold) if is volume preserving. For the remainder of this section we consider the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) and assume that the solutions to Equation (14) are defined for all . Recall that if all solutions to Equation (14) are bounded, then it follows from the Peano–Cauchy theorem ([23], pp. 16–17) that . The following theorem shows that if a dynamical system preserves volume, then almost all trajectories return arbitrarily close to their initial position infinitely often.

Theorem 4.6

Consider the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14). Assume that the flow of Equation (14) is volume preserving and maps an open bounded set onto itself, that is, is an invariant set with respect to Equation (14). Then the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) exhibits Poincaré recurrence, that is, almost every point returns to every open neighborhood of x infinitely many times.

Proof.

Since is locally Lipschitz continuous on and maps an open bounded set onto itself, it follows that the solutions to Equation (14) are bounded and unique for all and . Thus, the mapping is bijective. Furthermore, since the solutions of Equation (14) are continuously dependent on the system’s initial conditions, it follows that is continuous. Now, the result follows as a direct consequence of Theorem 4.4 with for every . ☐

It follows from Theorem 4.6 that a nonlinear dynamical system exhibits Poincaré recurrence if one of the statements in Theorem 4.5 holds with for every . Note that in this case it follows from (ii) of Theorem 4.5 that Poincaré recurrence is equivalent to the existence of a point such that x belongs to its positive limit set , that is, .

All Hamiltonian dynamical systems of the form given by Equations (17) and (18) exhibit Poincaré recurrence since they possess volume-preserving flows and are conservative in the sense that the Hamiltonian function remains constant along system trajectories. To see this, note that with , Equations (17) and (18) can be rewritten as

where and

Now, since

the Hamiltonian function is conserved along the flow of Equation (25). If is bounded from below and is radially unbounded, then every trajectory of the Hamiltonian system given by Equation (25) is bounded. Hence, by choosing the bounded region , where and , it follows that the flow of Equation (25) maps the bounded region onto itself. Since is arbitrary, the region can be chosen arbitrarily large. Furthermore, since Equation (25) possesses unique solutions over , it follows that the mapping is one-to-one and onto. Moreover,

which, by Theorem 4.1, shows that the flow of Equation (25) is volume preserving. Finally, since the flow of Equation (25) is volume preserving, continuous, and bijective, and maps a bounded region of a Euclidean space onto itself, it follows from Theorem 4.6 that the Hamiltonian dynamical system given by Equation (25) exhibits Poincaré recurrence. That is, in every open neighborhood of every point there exists a point such that the trajectory , of Equation (25) will return to infinitely many times.

Poincaré recurrence has been the main source for the long and fierce debate between the microscopic and macroscopic points of view of thermodynamics [1]. In thermodynamic models predicated on statistical mechanics, an isolated dynamical system will return arbitrarily close to its initial state of molecular positions and velocities infinitely often. If the system entropy is determined by the state variables, then it must also return arbitrarily close to its original value, and hence, undergo cyclical changes. This apparent contradiction between the behavior of a mechanical system of particles and the second law of thermodynamics remains one of the hardest and most controversial problems in statistical physics. The resolution of this paradox lies in the controversial statement that as system dimensionality increases, the recurrence time increases at an extremely fast rate. Nevertheless, the shortcoming of the mechanistic world view of thermodynamics is the absence of the emergence of damping in lossless mechanical systems. The emergence of damping is, however, ubiquitous in isolated [31] thermodynamic systems. Hence, the development of a viable dynamical system model for thermodynamics must guarantee the absence of Poincaré recurrence. The next set of results presents sufficient conditions for the absence of Poincaré recurrence for the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14). First, however, define the set of equilibria for the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) in by .

Theorem 4.7

Consider the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) and assume that . Assume that there exists a continuous function such that for every , , , is a strictly increasing (respectively, decreasing) function of time. Then the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) does not exhibit Poincaré recurrence on . That is, for some , there exists a neighborhood such that for every , .

Proof.

Suppose, ad absurdum, there exists such that for every open neighborhood containing x, there exists a point such that . Now, let be such that as and as . Since is continuous, it follows that . However, since is strictly increasing, it follows that , , which is a contradiction. The proof for the case where is strictly decreasing is identical. ☐

For the remainder of this section let be a closed invariant set with respect to the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14). The following definition for convergence is needed.

Definition 4.3

The nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) is convergent with respect to if exists for every .

If the system given by Equation (14) is convergent with respect to , then the ω-limit set of Equation (14) for the trajectory starting at is a singleton. Furthermore, it follows from continuity of solutions that for every , . Thus, and hence is an equilibrium point of Equation (14) for all . The next result relates the continuity of the function at a point x to the stability of the equilibrium point .

Proposition 4.1

Suppose the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) is convergent with respect to . If is a Lyapunov stable equilibrium point for some , then is continuous at x.

Proof.

A proof of this result appears in [32]. For completeness of exposition, we provide an alternative proof here. Suppose is Lyapunov stable for some , and let be an open neighborhood of . Moreover, choose open neighborhoods and of such that and for all , and let be a sequence in converging to x. The existence of such neighborhoods follows from the Lyapunov stability of . Next, there exists such that and, since the solutions to Equation (14) are continuously dependent on the system initial conditions, it follows that there exists an open neighborhood , of x such that for all . Furthermore, it follows from the Lyapunov stability of that , , , and hence, , , which proves that is continuous at x. ☐

The next result gives an alternative sufficient condition for the absence of Poincaré recurrence in a dynamical system.

Theorem 4.8

Consider the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14). Assume that and assume Equation (14) is convergent and semistable in . Then the nonlinear dynamical system given by Equation (14) does not exhibit Poincaré recurrence in . That is, for some , there exists an open neighborhood such that for every the trajectory , , does not return to infinitely many times.

Proof.

Let and let be a limiting point for the trajectory , so that . Since Equation (14) is convergent and semistable, it follows from Proposition 4.1 that , is continuous. Hence, for every there exists such that for all . Choose and such that . Furthermore, choose to be sufficiently small such that

Since the dynamical system given by Equation (14) is convergent in , it follows that for all and , there exists such that for all . Moreover, it follows from Equation (29) that, for all , , , does not return to infinitely many times, which proves the result with . ☐

5. Finite-Time Semistability of Nonlinear Dynamical Systems

The notion of semistability addressed in Section 2 implies convergence of the system trajectories to an equilibrium state over the infinite horizon. In physical thermodynamic systems, however, the dynamical system possesses the property that trajectories converge to a Lyapunov stable equilibrium in finite time rather than merely asymptotically. The key in achieving finite-time convergence versus asymptotic convergence of the system trajectories can be traced back to the structure of the thermodynamic system vector field characterizing energy flow between subsystem interconnections.

In particular, if the system vector field is Lipschitz continuous, which implies uniqueness of system solutions in forward and backward times, then convergence to an equilibrium state is achieved over an infinite time interval. Alternatively, in order to achieve convergence in finite time, the system dynamics need to be non-Lipschitzian giving rise to non-uniqueness of solutions in backward time. Uniqueness of solutions in forward time, however, can be preserved in the case of finite-time convergence. Sufficient conditions that ensure uniqueness of solutions in forward time in the absence of Lipschitz continuity are given in [33,34]. In addition, it is shown in ([35], Theorem 4.3, p. 59) that uniqueness of solutions in forward time along with continuity of the system dynamics ensure that the system solutions are continuous functions of the system initial conditions even when the dynamics are not Lipschitz continuous.

In this section, we merge the theories of semistability and finite-time stability developed in [20,21,22] to allow us to develop a rigorous framework for finite-time thermodynamics. First, we present the notions of finite-time convergence and finite-time semistability for nonlinear dynamical systems, and develop several sufficient Lyapunov stability theorems for finite-time semistability. Following [36], we exploit homogeneity as a means for verifying finite-time convergence. Our main result in this direction asserts that a homogeneous system is finite-time semistable if and only if it is semistable and has a negative degree of homogeneity. This main result depends on a converse Lyapunov result for homogeneous semistable systems, which we develop. While our converse result resembles a related result for asymptotically stable systems given in [36,37], the proof of our result is rendered more difficult by the fact that it does not hold under the notions of homogeneity considered in [36,37].

More specifically, while previous treatments of homogeneity involved Euler vector fields representing asymptotically stable dynamics, our results involve homogeneity with respect to a semi-Euler vector field representing a semistable system having the same equilibria as the dynamics of interest. Consequently, our theory precludes the use of dilations commonly used in the literature on homogeneous systems (such as [37]), and requires us to adopt a more geometric description of homogeneity (see [36] and references therein).

In this section, we consider nonlinear dynamical systems of the form

where , , is the system state vector, is a relatively open set with respect to , is continuous and essentially nonnegative on , that is, for all and , such that , is nonempty, and , , is the maximal interval of existence for the solution of Equation (30). The continuity of f implies that, for every , there exist and a solution of Equation (30) defined on such that . A solution x is said to be right maximally defined if x cannot be extended on the right (either uniquely or non-uniquely) to a solution of Equation (30). Here, we assume that for every initial condition , Equation (30) has a unique right maximally defined solution, and this unique solution is defined on .

Under these assumptions, the solutions of Equation (30) define a continuous global semiflow on , that is, is a jointly continuous function satisfying the consistency property and the semigroup property for every and . Furthermore, we assume that for every initial condition , Equation (30) has a local unique solution for negative time. The image of under the flow is defined as all . Finally, a set is connected if and only if every pair of open sets , , satisfying and , , has a nonempty intersection. A connected component of the set is a connected subset of that is not properly contained in any connected subset of .

Next, we establish the notion of finite-time semistability and develop sufficient Lyapunov stability theorems for finite-time semistability.

Definition 5.1

An equilibrium point of Equation (30) is said to be finite-time semistable if there exist a relatively open neighborhood of and a function , called the settling-time function, such that the following statements hold:

- (i)

- For every , for all , and exists and is contained in .

- (ii)

- is semistable.

It is easy to see from Definition 5.1 that, for all ,

where .

Lemma 5.1

Proof.

Necessity is immediate. To prove sufficiency, suppose that T is continuous at each . Let and consider a sequence in that converges to z. Let and . Note that both and are in and

Next, let be a subsequence of such that as . The sequence converges in to . By continuity and

for all and , as , where . Since T is assumed to be continuous at each , as . Note that

for all and . Using Equation (34) with and , we obtain as . Hence, , that is,

Now, let be a subsequence of such that as . It follows from Equations (32) and (35) that . Therefore, the sequence converges in to . Since s is continuous, it follows that as . Equation (33) implies that for each l. Hence, , and, by Equation (31),

It follows from Equations (32), (35), and (36) that , and hence, as . ☐

Next, we introduce a new definition which is weaker than finite-time semistability and is needed for the next result.

Definition 5.2

The system given by Equation (30) is said to be finite-time convergent to for if, for every , there exists a finite-time such that for all .

The next result gives a sufficient condition for characterizing finite-time convergence. For the statement of this result, define

for a given continuous function and for every such that the limit in Equation (37) exists.

Proposition 5.1

Let be positively invariant and . Assume that there exists a continuous function such that is defined everywhere on , if and only if , and

where and . Then Equation (30) is finite-time convergent to for . Alternatively, if V is nonnegative and

where , then Equation (30) is finite-time convergent to for .

The next result establishes a relationship between finite-time convergence and finite-time semistability.

Theorem 5.1

Assume that there exists a continuous nonnegative function such that is defined everywhere on , , and there exists a relatively open neighborhood such that is nonempty and

where is continuous, , and

has a unique solution in forward time. If Equation (42) is finite-time convergent to the origin for and every point in is a Lyapunov stable equilibrium point of Equation (30), then every point in is finite-time semistable. Moreover, the settling-time function of Equation (30) is continuous on a relatively open neighborhood of . Finally, if , then Equation (30) is finite-time semistable.

Proof.

Consider . Since is Lyapunov stable, it follows that there exists a relatively open positively invariant set containing . Next, it follows from Equation (41) that

Now, application of the comparison lemma (Theorem 4.1 of [34]) to the inequality Equation (43) with the comparison system given by Equation (42) yields

where is the global semiflow of Equation (42). Since Equation (42) is finite-time convergent to the origin for , it follows from Equation (44) and the nonnegativity of that

where denotes the settling-time function of Equation (42).

Next, since , is jointly continuous, and is equivalent to on , it follows that for . Furthermore, it follows from Equation (45) that for . Define by . Then it follows that every point in is finite-time semistable and T is the settling-time function on . Furthermore, it follows from Equation (45) that , . Since the settling-time function of a one-dimensional finite-time stable system is continuous at the equilibrium, it follows that T is continuous at each point in . Since was chosen arbitrarily, it follows that every point in is finite-time semistable, while Lemma 5.1 implies that T is continuous on a relatively open neighborhood of .

The last statement follows by noting that, if , then is positively invariant by our assumptions on Equation (30), and hence, the preceding arguments hold with . ☐

Theorem 5.2

Assume that there exists a continuous nonnegative function such that is defined everywhere on , , and there exists a relatively open neighborhood such that is nonempty and Equation (39) holds for all . Furthermore, assume that there exists a continuous nonnegative function such that is defined everywhere on , , and

where . Then every point in is finite-time semistable.

Proof.

For any , since for all , it follows from (i) of Theorem 5.2 of [20] that is a Lyapunov stable equilibrium and, hence, every point in is Lyapunov stable. Now, it follows from the second assertion of Proposition 5.1 and Theorem 5.1, with , that every point in is finite-time semistable. ☐

6. Homogeneity and Finite-Time Semistability

In this section, we develop necessary and sufficient conditions for finite-time semistability of homogeneous dynamical systems. In the sequel, we will need to consider a complete vector field ν on such that the solutions of the differential equation define a continuous global flow on , where . For each , the map is a homeomorphism and . We define a function to be homogeneous of degree with respect to ν if and only if , , . Our assumptions imply that every connected component of is invariant under ν. The Lie derivative of a continuous function with respect to ν is given by , whenever the limit on the right-hand side exists. If V is a continuous homogeneous function of degree , then is defined everywhere and satisfies . We assume that the vector field ν is a semi-Euler vector field, that is, the dynamical system

is globally semistable with respect to . Thus, for each , , and for each , there exists such that . Finally, we say that the vector field f is homogeneous of degree with respect to ν if and only if and, for every and ,

Note that if is a homogeneous function of degree l such that is defined everywhere, then is a homogeneous function of degree [37,38]. Finally, note that if ν and f are continuously differentiable in a neighborhood of , then Equation (48) holds at x for sufficiently small t and τ if and only if in a neighborhood of , where the Lie bracket of ν and f can be computed by using .

The following lemmas are needed for the main results of this section.

Lemma 6.1

Consider the dynamical system given by Equation (47). Let be a relatively compact set satisfying . Then for every relatively open set satisfying , there exist such that for all and for all .

Proof.

Let be a relatively open neighborhood of with respect to . Since every is Lyapunov stable under ν, it follows that there exists a relatively open neighborhood containing z such that for all . Hence, is relatively open and for all . Next, consider the collection of nested sets , where , . For each , is a relatively compact set. Therefore, if is nonempty for each , then there exists , that is, there exists such that for all , which contradicts the fact that the domain of semistability [39] of Equation (47) is . Hence, there exists such that , that is, . Therefore, for every , . The second conclusion follows using similar arguments as above. ☐

Lemma 6.2

Proof.

Let be the domain of semistability [39] and . Note that is a relatively open neighborhood of with respect to . Since every point in is a globally semistable equilibrium under with respect to , there exists such that . Then it follows from Equation (48) that . Since , it follows that , which implies that . Since is arbitrary, . ☐

The following theorem presents a converse Lyapunov result for homogenous semistable systems.

Theorem 6.1

Suppose is homogeneous of degree with respect to ν and Equation (30) is semistable. Then for every , there exists a continuous nonnegative function that is homogeneous of degree l with respect to ν, continuously differentiable on , and satisfies , , , and for each and each bounded, relatively open neighborhood containing with respect to , there exist such that

Proof.

Choose . First, we prove that there exists a continuous Lyapunov function V on that is homogeneous of degree l with respect to ν, continuously differentiable on , and for . Choose any nondecreasing smooth function such that for , for , and on , where are constants. It follows from Theorem 4.21 of [40] and Lemma 6.2 that there exists a continuously differentiable Lyapunov function on satisfying all of the properties in Theorem 4.21 of [40].

Next, define

Let be a bounded, relatively open set satisfying . Since every point in is a globally semistable equilibrium point under with respect to , it follows that for each , and . Now, it follows from Lemma 6.1 that there exist time instants such that for each , for all and for all . Hence,

which implies that V is well defined, positive, and continuously differentiable on .

Next, since satisfies (i) and (ii) of Theorem 4.21 of [40] it follows from Equations (50) and (51) that . Since for any and ,

by definition, V is homogeneous of degree l. In addition, it follows from Equations (48) and (51) that

which implies that is negative and continuous on . Now, since is arbitrary, it follows that V is well defined and continuously differentiable, and is negative and continuous on .

Next, to show continuity at points in , we define by , and note that the continuity of U implies that for all . Let , and consider a sequence in converging to . We claim that the sequence has no bounded subsequence so that . To prove our claim by contradiction, suppose, ad absurdum, that is a bounded subsequence. Without loss of generality, we may assume that the sequence converges to . Then, by joint continuity of ψ, , so that . However, this contradicts our observation above that for all . The contradiction leads us to conclude that . Now, for each it follows that

so that . Since was chosen arbitrarily, it follows that V is continuous at every .

To show that V possesses the last property, let , and choose a bounded, relatively open neighborhood of with respect to . Let . For every , denote . For every , define the continuous map by , and note that, for every , if and only if . Next, define by . Note that, for every , is continuous, and for every .

Consider . is the union of the images of connected components of under the continuous map . Since every connected component of is invariant under ν, it follows that the image of each connected component of under is contained in itself. In particular, the images of connected components of under are all disjoint. Thus, each connected component of is the image of exactly one connected component of under . Finally, if ε is small enough so that is nonempty, then , and hence, every connected component of has a nonempty intersection with .

We claim that is bounded for every . It is easy to verify that, for every , with . Hence, it suffices to prove that there exists such that is bounded. To arrive at a contradiction, suppose, ad absurdum, that is unbounded for every . Choose a bounded relatively open neighborhood of and a sequence in converging to 0. By our assumption, for every , at least one connected component of must contain a point in . On the other hand, for i sufficiently large, every connected component of has a nonempty intersection with . It follows that has a nonempty intersection with the boundary of for every i sufficiently large. Hence, there exists a sequence in , and a sequence in such that for every . Since is bounded, we can assume that the sequence converges to . Continuity implies that . Since , it follows that y is Lyapunov stable under . Since , there exists a relatively open neighborhood of y such that . The sequence converges to y while , which contradicts Lyapunov stability. This contradiction implies that there exists such that is bounded. It now follows that is bounded for every .

Finally, consider . Choose and note that . Furthermore, note that for all , is continuous on , and . Then, by homogeneity, , and hence,

Since is homogeneous of degree , it follows that

Let and . Note that and are positive and well defined since is compact. Hence, the theorem is proved. ☐

The following result represents the main application of homogeneity [36] to finite-time semistability.

Theorem 6.2

Suppose f is homogeneous of degree with respect to ν. Then Equation (30) is finite-time semistable if and only if Equation (30) is semistable and . In addition, if Equation (30) is finite-time semistable, then the settling-time function is homogeneous of degree with respect to ν and is continuous on .

Proof.

Since finite-time semistability implies semistability, it suffices to prove that if Equation (30) is semistable, then Equation (30) is finite-time semistable if and only if . Suppose Equation (30) is finite-time semistable and let . Then for each , it follows from Theorem 6.1 that there exist a bounded, relatively open, and positively invariant set containing , and a continuous nonnegative function that is homogeneous of degree and is such that is continuous, negative on , homogeneous of degree , and Equation (49) holds. Now, ad absurdum, if and , then application of the comparison lemma (Theorem 4.2 in [34]) to the first inequality in Equation (49) yields , where π is given by

and where , , and , with . Since, in this case, for all , we have for every ; that is, is not a finite-time semistable equilibrium under f, which is a contradiction. Hence, .

Conversely, if , choose and choose a relatively open neighborhood of such that Equation (50) holds. Next, is chosen to be a bounded, positively invariant neighborhood of contained in . Then it follows from Theorem 6.1 that there exists a continuous nonnegative function such that Equation (49) holds on . Now, with , , , and , it follows from Proposition 5.1 and Theorem 5.1 that is finite-time semistable on . Define . Then is a relatively open neighborhood of such that every solution in converges in finite time to a Lyapunov stable equilibrium. Hence, Equation (30) is finite-time semistable. Lemma 6.2 then implies that Equation (30) is globally finite-time semistable, and is defined on . By Proposition 5.1 with , and Theorem 5.1, it follows that is continuous on . Next, since was chosen arbitrarily, it follows from Lemma 5.1 that is continuous on .

Finally, let and note that, since every point in is a globally semistable equilibrium under with respect to , there exists such that . Then it follows from Equation (48) that , and hence, if and only if . Now, it follows that for , . By definition, it follows that is homogeneous of degree with respect to ν. ☐

In order to use Theorem 6.2 to prove finite-time semistability of a homogeneous system, a priori information of semistability for the system is needed, which is not easy to obtain. To overcome this, we need to develop some sufficient conditions to establish finite-time semistability. Recall that a function is said to be weakly proper if and only if for every , every connected component of the set is compact [21]. Furthermore, the following lemma giving a sufficient condition for a trajectory of Equation (30) to converge to a limit is needed.

Lemma 6.3

Proof.

Suppose is Lyapunov stable with respect to and let be a relatively open neighborhood of y. Since y is Lyapunov stable with respect to , there exists a relatively open neighborhood of y such that for every . Now, since , it follows that there exists such that . Hence, for every . Since is arbitrary, it follows that . Thus, for every sequence , and hence, . ☐

Proposition 6.1

Assume f is homogeneous of degree with respect to ν. Furthermore, assume that there exists a weakly proper, continuous function such that is defined on and satisfies for all . If every point in the largest invariant subset of is a Lyapunov stable equilibrium point of Equation (30), then Equation (30) is finite-time semistable.

Proof.

Since is weakly proper, it follows from Proposition 3.1 of [21] that the positive orbit of is bounded in . Since every solution is bounded, it follows from the hypotheses on that for every , the omega limit set is nonempty and contained in the largest invariant subset of . Since every point in is a Lyapunov stable equilibrium point, it follows from Lemma 6.3 that the omega limit set contains a single point for every . And since is Lyapunov stable for every , by definition, the system given by Equation (30) is semistable. Hence, it follows from Theorem 6.2 that Equation (30) is finite-time semistable. ☐

7. A State Space Formalism for Thermodynamics

The fundamental and unifying concept in the analysis of thermodynamic systems is the concept of energy. The energy of a state of a dynamical system is the measure of its ability to produce changes (motion) in its own system state as well as changes in the system states of its surroundings. These changes occur as a direct consequence of the energy flow between different subsystems within the dynamical system. Heat (energy) is a fundamental concept of thermodynamics involving the capacity of hot bodies (more energetic subsystems) to produce work. As in thermodynamic systems, dynamical systems can exhibit energy (due to friction) that becomes unavailable to do useful work. This in turn contributes to an increase in system entropy, a measure of the tendency of a system to lose the ability to do useful work. In this section, we use the state space formalism to construct a mathematical model of a thermodynamic system that is consistent with basic thermodynamic principles.

Specifically, we consider a large-scale system model with a combination of subsystems (compartments or parts) that is perceived as a single entity. For each subsystem (compartment) making up the system, we postulate the existence of an energy state variable such that the knowledge of these subsystem state variables at any given time , together with the knowledge of any inputs (heat fluxes) to each of the subsystems for time , completely determines the behavior of the system for any given time . Hence, the (energy) state of our dynamical system at time t is uniquely determined by the state at time and any external inputs for time and is independent of the state and inputs before time .

More precisely, we consider a large-scale dynamical system composed of a large number of units with aggregated (or lumped) energy variables representing homogenous groups of these units. If all the units comprising the system are identical (that is, the system is perfectly homogeneous), then the behavior of the dynamical system can be captured by that of a single plenipotentiary unit. Alternatively, if every interacting system unit is distinct, then the resulting model constitutes a microscopic system. To develop a middle-ground thermodynamic model placed between complete aggregation (classical thermodynamics) and complete disaggregation (statistical thermodynamics), we subdivide the large-scale dynamical system into a finite number of compartments, each formed by a large number of homogeneous units. Each compartment represents the energy content of the different parts of the dynamical system, and different compartments interact by exchanging heat. Thus, our compartmental thermodynamic model utilizes subsystems or compartments to describe the energy distribution among distinct regions in space with intercompartmental flows representing the heat transfer between these regions. Decreasing the number of compartments results in a more aggregated or homogeneous model, whereas increasing the number of compartments leads to a higher degree of disaggregation resulting in a heterogeneous model.

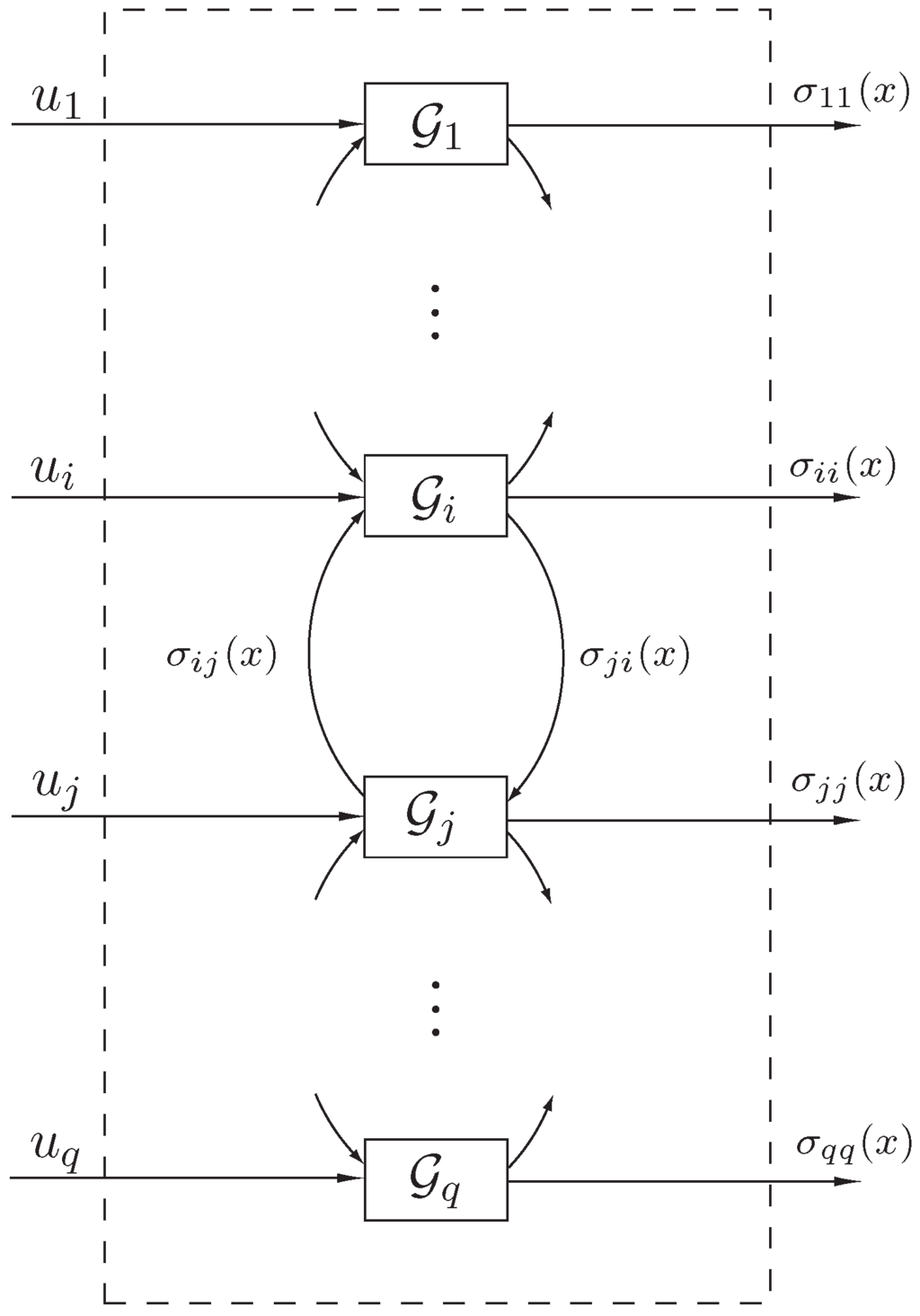

To formulate our state space thermodynamic model, consider the large-scale dynamical system shown in Figure 1 involving energy exchange between q interconnected subsystems. Let denote the energy (and hence a nonnegative quantity) of the ith subsystem, let denote the external power (heat flux) supplied to (or extracted from) the ith subsystem, let , , denote the instantaneous rate of energy (heat) flow from the jth subsystem to the ith subsystem, and let , denote the instantaneous rate of energy (heat) dissipation from the ith subsystem to the environment. In this and the next two sections, we assume that , are locally Lipschitz continuous on and are bounded piecewise continuous functions of time.

Figure 1.

Large-scale dynamical system .

An energy balance for the ith subsystem yields

or, equivalently, in vector form,

where , , , , and is such that

It is important to note that the exchange of energy between subsystems in Equation (56) is assumed to be a nonlinear function of all the subsystems, that is, . This assumption is made for generality and would depend on the complexity of the diffusion process. For example, thermal processes may include evaporative and radiative heat transfer as well as thermal conduction giving rise to complex heat transport mechanisms. However, for simple diffusion processes it suffices to assume that , wherein the energy flow from the jth subsystem to the ith subsystem is only dependent (possibly nonlinearly) on the energy in the jth subsystem, resulting in a donor-controlled compartmental model. Similar comments apply to system dissipation.

Note that Equation (56) yields a conservation of energy equation and implies that the energy stored in the ith subsystem is equal to the external energy supplied to (or extracted from) the ith subsystem plus the energy gained by the ith subsystem from all other subsystems due to subsystem coupling minus the energy dissipated from the ith subsystem to the environment. Equivalently, Equation (56) can be rewritten as

or, in vector form,

where , yielding a power balance equation that characterizes energy flow between subsystems of the large-scale dynamical system . Equation (59) shows that the rate of change of energy, or power, in the ith subsystem is equal to the power input (heat flux) to the ith subsystem plus the energy (heat) flow to the ith subsystem from all other subsystems minus the power dissipated from the ith subsystem to the environment. Furthermore, since is locally Lipschitz continuous on and is a bounded piecewise continuous function of time, it follows that Equation (60) has a unique solution over the finite time interval . If, in addition, the power balance Equation (60) is input-to-state stable [40], then .

Equation (57) or, equivalently, Equation (60) is a statement of the first law of thermodynamics as applied to isochoric transformations (i.e., constant subsystem volume transformations) for each of the subsystems , with , , , and , playing the role of the ith subsystem internal energy, rate of heat supplied to (or extracted from) the ith subsystem, heat flow between subsystems due to coupling, and the rate of energy (heat) dissipated to the environment, respectively. To further elucidate that Equation (57) is essentially the statement of the principle of the conservation of energy, let the total energy in the large-scale dynamical system be given by , where and , and let the net energy received by the large-scale dynamical system over the time interval be given by

where , is the solution to Equation (60). Then, premultiplying Equation (57) by and using the fact that , it follows that

where denotes the variation in the total energy of the large-scale dynamical system over the time interval . This is a statement of the first law of thermodynamics for isochoric transformations of the large-scale dynamical system and gives a precise formulation of the equivalence between the variation in system internal energy and heat.

It is important to note that the large-scale dynamical system model given by Equation (60) does not consider work done by the system on the environment nor work done by the environment on the system. Hence, Q can be physically interpreted as the net amount of energy that is received by the system in forms other than work. The extension of addressing work performed by and on the system can be easily addressed by including an additional state equation, coupled to the power balance Equation (60), involving volume (deformation) states for each subsystem. Since this extension does not alter any of the conceptual results of this paper, it is not considered here for simplicity of exposition. Work performed by the system on the environment and work done by the environment on the system is addressed in [1,41].

For our large-scale dynamical system model , we assume that , whenever. In this case, , is essentially nonnegative, that is, for all and such that . The above constraint implies that if the energy of the jth subsystem of is zero, then this subsystem cannot supply any energy to its surroundings nor dissipate energy to the environment. Moreover, we assume that whenever , , , which implies that when the energy of the ith subsystem is zero, then no energy can be extracted from this subsystem. Under these assumptions, it can be shown (see [1] for details) that the solution , , to Equation (60) is nonnegative for all nonnegative initial conditions .

8. Entropy and Irreversibility

The nonlinear power balance Equation (60) can exhibit a full range of nonlinear behavior, including bifurcations, limit cycles, and even chaos. However, a thermodynamically consistent energy flow model should ensure that the evolution of the system energy is diffusive (parabolic) in character with convergent subsystem energies. As established in Section 4, such a system model would guarantee the absence of Poincaré recurrence. Otherwise, the thermodynamic model would violate the second law of thermodynamics, since subsystem energies (temperatures) would be allowed to return to their starting state and thereby subverting the diffusive character of the dynamical system. Hence, to ensure a thermodynamically consistent energy flow model, we require the following axioms. For the statement of these axioms [42], we first recall the following graph-theoretic notions.

Definition 8.1

([43]) A directed graph associated with the connectivity matrix has vertices and an arc from vertex i to vertex j, , if and only if . A graph associated with the connectivity matrix is a directed graph for which the arc set is symmetric, that is, . We say that is strongly connected if for any ordered pair of vertices , , there exists a path (i.e., a sequence of arcs) leading from i to j.

Recall that the connectivity matrix is irreducible, that is, there does not exist a permutation matrix such that is cogradient to a lower-block triangular matrix, if and only if is strongly connected (see Theorem 2.7 of [43]). Let , denote the net energy flow from the jth subsystem to the ith subsystem of the large-scale dynamical system .

Axiom (i) The connectivity matrix associated with the large-scale dynamical system is defined by

and

and satisfies rank . Moreover, for every such that , if and only if .

Axiom (ii) For , , .

The fact that if and only if , implies that subsystems and of are connected; alternatively, implies that and are disconnected. Axiom (i) implies that if the energies in the connected subsystems and are equal, then energy exchange between these subsystems is not possible. This statement is consistent with the zeroth law of thermodynamics, which postulates that temperature equality is a necessary and sufficient condition for thermal equilibrium. Furthermore, it follows from the fact that and rank that the connectivity matrix is irreducible, which implies that for every pair of subsystems and , , of there exists a sequence of connectors (arcs) of that connect and . Axiom (ii) implies that energy flows from more energetic subsystems to less energetic subsystems and is consistent with the second law of thermodynamics, which states that heat (energy) must flow in the direction of lower temperatures [44]. Furthermore, note that , , which implies conservation of energy between lossless subsystems. With , Axioms (i) and (ii) along with the fact that , , imply that at a given instant of time, energy can only be transported, stored, or dissipated but not created, and the maximum amount of energy that can be transported and/or dissipated from a subsystem cannot exceed the energy in the subsystem.

Next, we show that the classical Clausius equality and inequality for reversible and irreversible thermodynamics over cyclic motions are satisfied for our thermodynamically consistent energy flow model. For this result ∮ denotes a cyclic integral evaluated along an arbitrary closed path of Equation (60) in ; that is, with and such that .

Proposition 8.1

Consider the large-scale dynamical system with power balance Equation (60), and assume that Axioms (i) and (ii) hold. Then, for all , , and such that ,

where , , , is the amount of net energy (heat) received or dissipated by the ith subsystem over the infinitesimal time interval , and , , is the solution to Equation (60) with initial condition . Furthermore,

if and only if there exists a continuous function such that , .

Proof.