Abstract

Digital platforms offer cost-effective, accessible tools for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). However, the mechanisms through which resource-constrained SMEs should participate in these platforms remain underexplored. By distinguishing participation breadth from participation depth and introducing value co-creation and external resource abundance as the mediating mechanism and boundary condition, respectively, this study offers an integrated account of how digital platform participation (DPP) relates to SME performance. Drawing on the theory of resource bricolage, this study conducted an online survey of 321 owners or managers, using small and medium-sized travel agencies in China as the empirical setting. This study develops an integrated mediation and moderation model and tests the hypotheses using confirmatory factor analysis, hierarchical regression, and bootstrapping analysis. The results show that both breadth and depth are positively associated with performance, with depth showing a significantly stronger association than breadth. Participation that combines transaction-oriented platforms with information-oriented platforms is associated with the largest performance gains. Value co-creation mediates the effect of depth on performance, whereas the mediation via breadth is not significant. External resource abundance weakens the performance returns to DPP. These findings inform resource-constrained SMEs’ platform strategies, particularly how to allocate scarce attention and resources between deepening and broadening participation and how to configure platform portfolios in relation to performance outcomes.

1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are key drivers of national economic growth [1] and significant contributors to employment [2]. However, due to challenges such as talent shortages and financial constraints [3], SMEs are currently facing challenges of low operational efficiency, weak innovation capability, and insufficient marketing capacity [4,5]. The resource-based view (RBV) argues that firms need to continuously accumulate core resources to gain competitive advantages [6]. However, SMEs, constrained by limited resources, find it difficult to obtain or build such advantages [7]. In today’s highly competitive and uncertain environment [8], SMEs urgently need to seek new resources and strategies to navigate challenges related to survival and growth.

Resource bricolage theory offers an alternative perspective, focusing on firms’ ability to recombine “resources at hand” at minimal cost to achieve innovation and performance improvement [9]. This theory is particularly relevant for resource-constrained SMEs, as it emphasizes leveraging available resources creatively to drive growth and overcome limitations [10].

In the digital era, digital platforms that are characterized by low entry barriers, high accessibility, and interactivity [11] have emerged as valuable resources for SMEs, helping them to compensate for resource disadvantages and promote growth [12]. Research has shown that digital platform participation (DPP) can significantly improve SME performance outcomes [13]. Regarding the specific pathways through which DPP enhances SME performance, it can reshape SMEs’ business models [14], stimulate their innovation [15], and at the same time facilitate interactions with platform operators, customers, and other partners, thereby achieving value co-creation [16].

Although prior studies generally report positive associations between digital platform participation and SME performance [13], the evidence remains fragmented and the underlying explanations are not yet fully integrated. Existing work has predominantly emphasized internal factors, such as firms’ capabilities and capital [15,17], and has often been framed through the resource based view [6], which focuses on resource endowments as key determinants of platform related outcomes. In contrast, less attention has been paid to how resource constrained SMEs can optimize their participation behavior when resources and managerial attention are limited. In particular, many studies operationalize platform participation as a single composite construct, which obscures the potentially distinct roles of participation breadth and participation depth as different resource allocation strategies [15,17]. Moreover, the boundary conditions of the platform participation performance relationship remain underexplored, especially the extent to which external resource environments may substitute for platform enabled resource bricolage [9].

Moreover, prior research often treats digital platforms as a homogeneous category [18] or focuses on a single platform type [19], which limits understanding of whether different platform types and their combinations offer distinct resource bundles and performance implications for SMEs. Digital platforms can be categorized into transaction-oriented, information-oriented, and government-oriented platforms [20,21,22], each offering distinct resources. Transaction-oriented platforms (e.g., Meituan, Amazon) provide SMEs with cross-regional network models and expanded sales opportunities [23,24], while information-oriented platforms (e.g., REDnote, TikTok, Sina News) help manage customer relationships and identify potential customers [25,26]. Government-oriented platforms (e.g., China National Financing Credit Service Platform) offer regulatory data and legal updates, enhancing SMEs’ operational efficiency [27]. Given these differences across platform types, it remains unclear whether resource constrained SMEs benefit more from engaging broadly across platform types or from selectively focusing on particular types, and whether certain platform portfolios are more strongly associated with performance.

To address this research gap, this study applies resource bricolage theory to examine how the breadth and depth of DPP, along with external resource abundance, affect SMEs’ value co-creation and performance. The study focuses on small and medium-sized travel agencies (SMTAs) in China as the research sample. China is chosen as the empirical setting since tourism is one of its key industries; tens of thousands of travel agencies operate nationwide, and participation in digital platforms is widespread [28]. In addition, the tourism service industry, characterized by high intangibility and significant co-creation [29], is an ideal context for studying DPP in SMEs. Moreover, the tourism resources, which are critical external assets for SMEs in this sector [30], are regionally distinct and measurable, facilitating the analysis of the moderating effects of external resource abundance [31].

The findings of this study reveal that the effect of depth on SME performance is significantly stronger than that of breadth. The depth of DPP also promotes value co-creation, which indirectly boosts performance, whereas breadth is not significantly associated with co-creation. Furthermore, participation in both transaction-oriented and information-oriented platforms shows the best performance outcomes. Additionally, higher levels of external resource abundance weaken the positive effects of DPP on SME performance.

This study makes three key theoretical contributions. First, it advances the literature on digital platform participation (DPP) by distinguishing the effects of participation breadth and depth on SME performance, and categorizing platform types (transaction-oriented, information-oriented, and government-oriented), offering a strategic framework for SMEs. Second, it extends resource bricolage theory by applying it to the digital context, showing how SMEs leverage digital platforms as valuable “resources at hand” to overcome constraints and drive performance. Third, it introduces external resource abundance as a moderating factor, expanding resource-based theories by highlighting the role of external resources in shaping DPP outcomes, thus addressing a gap in research that focuses primarily on internal resources.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Digital Platform Participation and SME Performance

Baker and Nelson systematically proposed the resource bricolage theory in their study of how entrepreneurial firms cope with resource scarcity. The resource bricolage theory suggests that the success of firms depends not only on their specific resources but also on their ability to identify and utilize all “resources at hand,” to “make do” (that is, innovatively use internal and external resources), and to “recombine” (that is, reorganize and adjust these resources) in order to create new opportunities [9]. Since SMEs face significant internal resource constraints [32], the resource bricolage theory emphasizes the potential of actively and innovatively leveraging external resources [33] to achieve growth. An increasing number of SMEs are engaging in digital platform participation (DPP) [34] to realize the value advocated by resource bricolage behavior.

In existing studies, the breadth of DPP and the depth of DPP are regarded as two key dimensions for measuring firms’ digital platform participation behaviors, reflecting differences in the diversity of platform types in which firms participate [12,35] and in the degree of resource input [35], respectively. The literature shows that the breadth of DPP emphasizes firms’ participation in multiple platforms to expand information sources [36] and their contact with stakeholders [37], thereby enabling them to accumulate resources such as suppliers [4] and customers [38]. Customer resources can be directly transformed into consumption potential, while broad engagement with different suppliers helps foster cooperative relationships among multiple parties [39], share knowledge resources, accelerate innovation by participating firms [40], and develop market-oriented products [41], thus achieving performance growth.

The depth of DPP focuses on firms’ continuous investment and deep interaction within a single platform [35,42]. The depth of DPP is related to the extent to which firms maintain relationships with stakeholders on the platform, such as suppliers and customers. By devoting more time and resources to maintaining these relationships and frequently interacting with customers, SMEs can strengthen their ties with customers. For example, SMEs can use customer data collected on digital platforms (such as reviews, browsing histories, and purchase records) to better understand customers’ needs and expectations [43]. At the same time, through deep participation in digital platforms, SMEs can enhance their relationships with suppliers and competitors [44]. The depth of DPP increases the timeliness of information exchange and the frequency of business interactions, thereby promoting better cooperation among suppliers, product development, and knowledge sharing [8,45]. Deep participation in digital platforms is crucial for fully utilizing and integrating platform resources to achieve performance growth [45,46,47].

Although both the breadth of DPP and the depth of DPP help firms achieve performance improvement, they do not have equivalent effects on performance enhancement for resource-constrained SMEs. The resource bricolage theory provides an important perspective for understanding this difference. The theory further distinguishes bricolage behaviors into parallel bricolage and selective bricolage: the former refers to firms simultaneously acquiring resources in multiple contexts, which is likely to result in problems of resource dispersion and coordination complexity, while the latter refers to firms focusing on a key context, where concentrated investment enables the maximization of resource bricolage and utilization [48,49].

For resource-constrained SMEs, deeply engaging in a single or a limited number of platforms and strengthening continuous interactions with stakeholders is more conducive to identifying, integrating, and recombining platform resources, thereby enhancing customer insights, product feedback, and innovation capabilities, which in turn generate higher performance returns [49]. In contrast, while the breadth of DPP expands contact scope, in practice, due to the limited internal resources of SMEs [3], their human and financial resources are likely to become overly dispersed, leading to insufficient investment in each platform. Ultimately, participation across multiple platforms is not highly efficient and may even increase coordination costs due to inconsistencies in strategies among platforms [50], thereby constraining performance growth. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

The depth of DPP has a more significant positive impact on SME performance than the breadth of DPP.

2.2. Mediating Effect of Value Co-Creation

Value co-creation refers to the process by which firms transcend traditional organizational boundaries and interact and collaborate with other stakeholders to create new value [51]. Digital platforms help SMEs overcome geographical, temporal, and organizational constraints, enabling them to establish cooperative relationships with other stakeholders participating in digital platforms and facilitating resource sharing and recombination among different stakeholders [52]. Therefore, SMEs’ DPP promotes the realization of value co-creation.

As the breadth of DPP increases, SMEs can seek resource complementarities with customers or suppliers across a more diverse set of platforms [53], thereby enlarging the pool of potential resources and opportunities that may support value co-creation. For instance, engaging with customers on different platforms enables SMEs to obtain diversified market insights and feedback, which can inform subsequent product development and optimization and, in turn, contribute to improved performance [54]. In addition, establishing cooperative relationships with suppliers across platforms can help SMEs secure a stable supply of resources while benefiting from horizontal price comparisons and enhanced bargaining power [55]. Such advantages may further facilitate the development of more competitive products [56] and support performance outcomes. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2.

Value co-creation mediates the relationship between the breadth of DPP and SME’ performance.

In addition, increasing the depth of DPP can enhance value co-creation between SMEs and key stakeholders. Frequent participation of SMEs in business activities on digital platforms facilitates the exchange of detailed information with stakeholders [57], thereby strengthening connections with platform participants and promoting resource sharing [58]. Through deep participation, SMEs can recombine bricolaged resources (such as information and opportunities) into valuable assets, such as trust, innovation, and risk mitigation. For example, frequently responding to customer reviews not only strengthens relationships but also generates electronic word of mouth, enhancing trust and consumer acceptance [59,60], thereby creating sustainable competitive advantages for SMEs. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

Value co-creation mediates the relationship between the depth of DPP and SME performance.

While expanding the breadth of DPP may increase SMEs’ exposure to multiple stakeholders and create opportunities for interaction and value co-creation across platforms, participation across many platforms may also entail resource dispersion and higher coordination demands [9]. As SMEs spread limited resources and managerial attention across platforms, sustained engagement and relational investment on any single platform may become more difficult to maintain. Because effective value co-creation typically requires sufficient and continuous resource inputs and coordinated processes [61], broader participation alone may not reliably translate into a stable and enduring value co-creation mechanism.

In contrast, the emergence of value co-creation is closely tied to the strength of stakeholder relationships and the quality and frequency of interactions [62]. By deepening DPP, SMEs are more likely to engage in high-frequency interactions with stakeholders, fostering closer and more reciprocal relationships. Such relational embeddedness can strengthen trust [63] and generate multiple benefits, including improved performance, reduced conflict, and greater relationship satisfaction [64]. Accordingly, compared with participation breadth, participation depth is more likely to transform platform engagement into realized value co-creation outcomes. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

The depth of DPP has a more significant positive effect on value co-creation than the breadth of DPP.

2.3. Moderating Effect of External Resource Abundance

SMEs’ operations are constrained not only by internal resources but also profoundly influenced by external resources, especially local external resources [65]. Examples include local market traffic, industrial clusters and collaboration networks, and public services and policy support [66,67,68]. SMEs often need to rely on these offline resources to conduct their business [69]. However, due to imbalances in regional development and factor endowments, there are significant differences in the abundance of local external resources faced by SMEs across regions [31].

From the perspective of the resource bricolage theory, abundant local external resources also provide SMEs with a large number of “resources at hand.” Accordingly, external resources and online resources available via digital platforms exhibit a certain degree of substitutability. When external resources are already abundant, firms can rely less on platform-based resources to accomplish customer acquisition, partnership formation, and transaction matchmaking; in other words, the more abundant the external resources, the lower the necessity for SMEs to participate in digital platforms to obtain resources, and the weaker the effectiveness of attracting and retaining customers through platforms.

When external resources are abundant, they can themselves provide local SMEs with a baseline level of customer inflow, and some SMEs can essentially meet their survival needs by relying on rich local resources [70]. Viewed through the lens of resource bricolage, this logic is consistent with parallel bricolage, in which expanding participation breadth mainly increases resource reach but also accelerates redundancy and diminishing marginal returns when local resources are already plentiful. Moreover, they increase the number of platform presences (i.e., the breadth of DPP), their capacity to provide services is already close to saturation, and redundant resources cannot be further converted into revenue [71]. In addition, expanding participation breadth also increases managerial attention and coordination requirements across platforms. When external resources are abundant, SMEs may prioritize integrating offline opportunities and relationships, making it harder to sustain effective multi-platform operations, which in turn weakens the association between participation breadth and performance. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5.

When external resources are abundant, the positive effect of the breadth of DPP on SME performance is weakened.

Moreover, when external resources are abundant, SMEs can draw on a broader and more accessible set of offline resources, such as local customer traffic, supplier networks, and public services and policy support [65,66,67,68,69]. From a resource bricolage perspective, richer local resources expand firms’ resources at hand and may substitute for platform enabled resources in fulfilling core operational needs [9]. In such contexts, SMEs may rationally reallocate scarce managerial attention, time, manpower, and budget toward integrating local opportunities [72]. This attention reallocation is particularly consequential for participation depth because deep platform engagement typically requires sustained operational inputs, including continuous content maintenance, frequent stakeholder interaction, and ongoing monitoring and analysis of platform data [72]. As these platform specific inputs decline, SMEs’ participation depth is likely to weaken, which in turn constrains the accumulation of platform based informational and relational resources that are often needed for performance relevant benefits [9]. Therefore, the positive association between participation depth and SME performance is expected to be weaker when external resources are abundant. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6.

When external resources are abundant, the positive effect of the depth of DPP on SME performance is weakened.

Although the above assumptions suggest that external resource abundance weakens the performance-enhancing effects of both the breadth of DPP and the depth of DPP for SMEs, a closer examination reveals that the pathways and magnitudes of these influences are not the same. From the perspective of resource bricolage, SMEs increase the breadth of DPP by accessing multiple types of platforms to expand the resources they can reach. However, when external resource abundance is high, resources such as customer inflow provided by platforms are directly superimposed, making the outcome of parallel bricolage redundant and causing the marginal contribution to decline rapidly. By contrast, the relational capital (such as trust and reputation) established through the depth of DPP constitutes intangible resources that exert long-term effects on SMEs’ development. These are different from externally accessible abundant resources and are thus less sensitive to the influence of external resource abundance than the breadth of DPP. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7.

When external resources are abundant, the positive effect of the breadth of DPP on SME performance is weakened more than that of the depth of DPP.

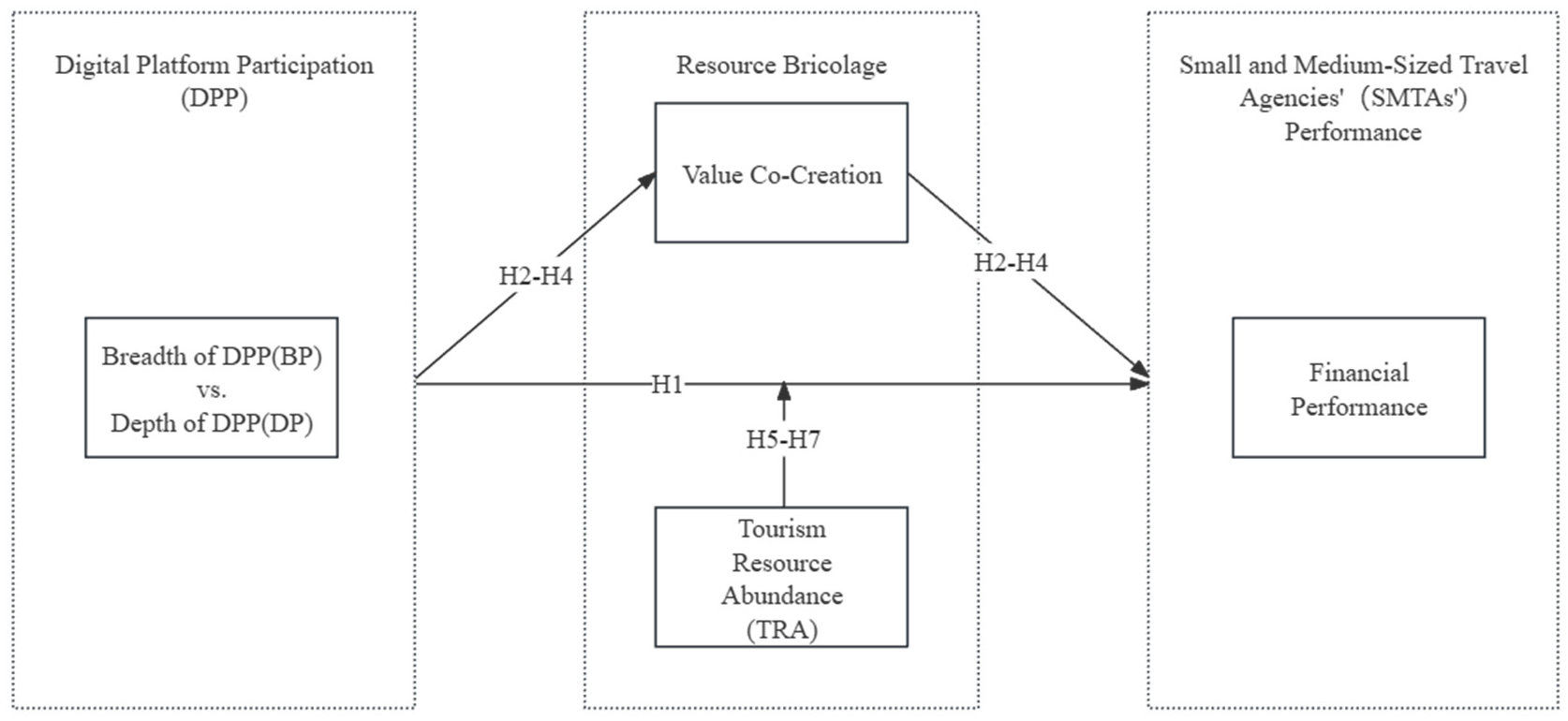

In summary, a conceptual model has been put forth as Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.1.1. Data Sample Selection

Since there are a considerable number of small and medium-sized enterprises across various industries, this study selects small and medium-sized travel agencies (SMTAs) as a typical representative of SMEs for three reasons. First, in the service industry, especially in tourism services, SMEs account for a very high proportion [56]. For example, SMEs constitute 60–80% of travel agencies in Romania [73]. The large number of SMTAs facilitates sample collection. Second, as part of SMEs, SMTAs are increasingly using digital platforms to cope with the performance crisis brought about by the disintermediation of the tourism industry [28], which fits the research context of this study focusing on digital platforms. Third, SMTAs are regarded as a key link in the tourism industry [74]. As intermediaries, they help distribute tourism products and services from suppliers to travelers [75]. Their business content integrates multiple aspects, including the connection of tourism resources (such as hotels, scenic spots, and transportation), service delivery, and customer relationship management. This makes them suitable for investigating the mechanism by which resource-constrained SMEs participate in digital platforms to bricolage resources and improve performance. In sum, choosing SMTAs as the sample for this study provides both representative industry characteristics and a typical real-world scenario.

3.1.2. Data Collection Procedure

An online survey was conducted in early August 2024 via the professional research platform Credamo. Owners or primary managers of SMTAs were contacted and snowball sampling was employed on social media to recruit participants who met the survey’s eligibility criteria. The data collection process lasted for 14 days, resulting in 750 responses. To ensure survey data quality, following prior recommendations on online survey data screening and the identification of careless responding [76,77], a stepwise screening procedure was applied to the 750 returned questionnaires. First, 98 responses were excluded because the respondent’s role or the firm type did not meet the study’s target criteria. Second, 68 questionnaires were removed due to abnormal completion times, defined as less than 3 min or more than 60 min. Third, 183 responses were excluded due to low-quality response patterns, such as repetitive selection of the same option across consecutive items. Finally, 80 questionnaires were excluded because reverse-coded items indicated inconsistent responses. After completing these screening steps, 321 valid questionnaires were retained, yielding an effective response rate of 42.8%.

3.1.3. Sample Characteristics

As detailed in Table A1 in Appendix A, SMTAs in the sample are located across 22 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, and 4 municipalities in mainland China, covering a wide geographical range. 297 of the sampled SMTAs were privately owned (92.56%). 312 of the sampled SMTAs were classified as small or micro-sized businesses (97.19%). The majority operate for fewer than five years (77.57%).

3.1.4. Common Method Bias

Since most of the questionnaire data were self-reported by the owners or managers of SMTAs, there may be potential common method bias. To address this concern procedurally, the study employed two data collection channels, an online research platform and private social media, and incorporated reverse-coded items into the questionnaire design to reduce potential common method bias. In addition, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The exploratory factor analysis showed that the first unrotated principal component explained 47.478% of the total variance, which is below the critical threshold of 50% [78]. In addition to Harman’s single-factor test, a CFA one-factor model was estimated in which all measurement items were specified to load on a single latent factor. The one-factor model exhibited poor fit (χ2/df = 4.144, GFI = 0.804, CFI = 0.853, RMR = 0.147), suggesting that a single common factor is unlikely to account for the covariance among the measurement items [78]. Accordingly, common method bias is unlikely to be a major concern in this study.

3.2. Variables and Measures

3.2.1. Measures

Breadth of DPP (BP): Digital platforms were first classified into seven general types: online travel agencies, e-commerce platforms, social media platforms, government-led platforms, lifestyle service platforms, news and information platforms, and attraction operation platforms [12,79]. Respondents were asked to indicate their participation in every platform category via binary-choice questions, with “yes” coded as 1 and “no” coded as 0. BP was measured by the sum of all scores.

Depth of DPP (DP): DP was measured by five items adapted from the degree of tourism enterprises’ participation in digital platforms [80]. Respondents were asked to report the frequency of conducting activities such as launching new products, updating content, browsing news, interacting with stakeholders, and monitoring and analyzing platform data on digital platforms. In this study, DP is defined as the extent to which SMEs engage in sustained and frequent use of platform functionalities. The above items correspond to core aspects of platform use, including product management, information acquisition, relational interaction, and data monitoring and analysis. Together, they capture SMEs’ intensive use of digital platform functions from multiple facets and reflect the depth of DPP.

Financial Performance (FP): SMTAs’ performance was measured by their financial performance [81]. Respondents were asked to assess three items related to financial performance: revenue, profit, and market share [82].

Value Co-Creation (VC): VC was measured by 11 items related to goal alignment, resource complementarity, conflict resolution, risk sharing, and cost sharing [83].

External Resource Abundance (ERA): In the tourism industry, SMTAs rely on external tourism resources to develop their tourism products and services [30]. According to China’s Tourist Attraction Quality Grading Standards, attractions are classified into five levels from 1A to 5A, with higher levels indicating better construction and management standards [31]. By means of Equation (1), based on the number and grades of A-level attractions, it is possible to effectively calculate the external tourism resource abundance (TRA) accessible to SMTAs within a given region [22]:

TRAi = 5.0N5 + 2.5N4 + 1.75N3 + 0.5N2 + 0.25N1

Note: TRAi represents TRA of region i; N1 to N5 represent the number of scenic spots rated 1A~5A, respectively.

Respondents were asked to report the province or municipality where their enterprises are located. Using the TRA formula and data from the 2023 China Statistical Yearbook accessed from National Bureau of Statistics of China (https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/) (accessed on 23 September 2024)), TRA values for each province, autonomous region, or municipality were calculated (the minimum value was 172.5 for Hainan Province while the maximum value was 2394.25 for Zhejiang Province, and the median value was 1014 for Yunnan Province). To standardize the data for subsequent hypothesis testing and facilitate the observation of coefficients, TRA values were scaled down by a factor of 250, resulting in a range from 0.69 to 9.577.

Control variables: Previous studies have indicated that factors such as the size, nature, and years of operation of tourism enterprises can influence their financial performance [84]. Therefore, Enterprise Size (ES), Enterprise Nature (EN), and Enterprise Age (EA) were measured as control variables.

3.2.2. Construct Reliability and Validity

As shown in Table 1, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for each variable range from 0.794 to 0.923, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7, indicating strong internal consistency of the model. The KMO value is 0.945 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity is significant, suggesting that these variables are suitable for factor analysis. On this basis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the model. The standardized factor loadings of all items range from 0.613 to 0.882, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.5. In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for each construct range from 0.524 to 0.572, exceeding the threshold of 0.5, while the composite reliability (CR) values range from 0.798 to 0.924, all of which exceed the acceptable standard of 0.7. The square root of the AVE for each construct is greater than the absolute value of its correlations with other constructs, further confirming the discriminant validity of the model. Taken together, these criteria indicate that the model exhibits satisfactory reliability and validity [85].

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

4. Analysis and Results

Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations of each variable, as well as the correlations among variables. The absolute values of the correlation coefficients between variables are less than 0.8, the VIF values are below 10, and the tolerance levels are above 0.1. These results indicate that there is no multicollinearity issue [86].

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

4.1. DPP and SME Performance

Model 1 in Table 3 shows that the breadth of DPP (β = 0.156, p < 0.05, 95% CI: [0.050, 0.278]) and the depth of DPP (β = 0.452, p < 0.01, 95% CI: [0.365, 0.609]) have significant positive effects on the performance of SMTAs, which supports prior research [12]. A further t-test indicates (|t| = 3.80, p < 0.01) that, compared with breadth, the depth of DPP has a significantly larger impact on the performance of SMTAs, thereby supporting Hypothesis H1. This pattern is consistent with resource bricolage theory, which suggests that focused and sustained engagement helps resource constrained SMEs more effectively identify, integrate, and recombine resources at hand [3,9,48,49]. By contrast, broader participation may disperse limited managerial attention across platforms and increase coordination demands, thereby weakening the conversion of platform engagement into performance relevant outcomes [50].

Table 3.

Regression analysis results.

4.2. Mediating Role of Value Co-Creation

According to Model 2 in Table 3, the breadth of DPP (β = 0.048, p > 0.05) has a positive but insignificant effect on value co-creation. Therefore, the bootstrap method of the PROCESS procedure shows that the 95% confidence interval of value co-creation in Table 4 contains zero, indicating that it is not a mediating variable between the breadth of DPP and the performance of SMTAs (β = 0.018, SE = 0.017, 95% CI: [−0.014, 0.052]). Thus, Hypothesis H2 is not supported. This null mediation is theoretically plausible because participation breadth may primarily expand exposure and potential opportunities, yet resource constrained SMEs may struggle to sustain the relational investment and coordination required to translate dispersed platform interactions into realized value co-creation outcomes [3,9,61].

Table 4.

Bootstrap test results of the mediating effect.

In contrast, as shown in Model 2 of Table 3, the depth of DPP (β = 0.643, p < 0.01) has a significant positive effect on value co-creation. Furthermore, Model 3 shows that value co-creation has a positive effect on the performance of SMTAs (β = 0.547, p < 0.01). A further bootstrap analysis indicates that, through the path “depth of DPP → value co-creation → financial performance,” the indirect effect is significant, as shown in Table 4 (β = 0.249, SE = 0.048, 95% CI: [0.140, 0.329]). Therefore, Hypothesis H3 is supported. This pattern aligns with resource bricolage logic in that deeper participation facilitates sustained interaction and resource recombination with key stakeholders, which is conducive to realized value co-creation and performance outcomes [9,57,61].

To compare the differing effects of the breadth and depth of DPP on value co-creation, a t-test was conducted on the standardized regression coefficients for the breadth of DPP (β = 0.048, p > 0.05) and the depth of DPP (β = 0.643, p < 0.01). The results (|t| = 8.96, p < 0.01) indicate that the effect of the depth of DPP on value co-creation is significantly greater than that of the breadth of DPP, which supports Hypothesis H4. This finding is consistent with prior work suggesting that value co-creation depends on sustained interaction and relational investment, which aligns more closely with the depth of DPP [61,62].

4.3. Moderating Role of External Resource Abundance

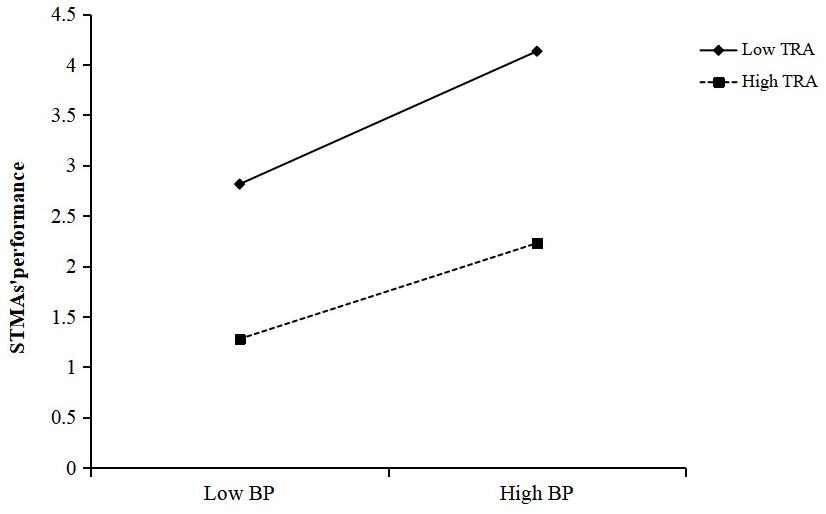

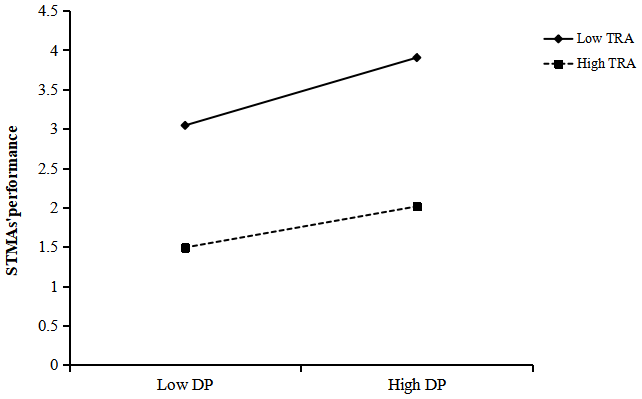

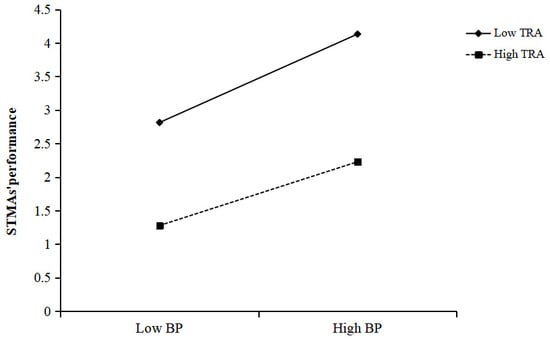

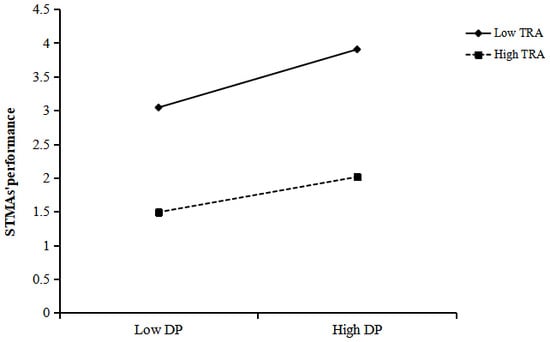

As shown in Model 5 of Table 3, the interaction effect between the breadth of DPP and tourism resource abundance has a significant negative impact on the performance of SMTAs (β = −0.067, p < 0.05). Similarly, the interaction effect between the depth of DPP and tourism resource abundance also has a significant negative impact on SMTAs’ performance (β = −0.066, p < 0.05). These findings indicate that tourism resource abundance plays a negative moderating role in the relationships between both the breadth and depth of DPP and the performance of SMTAs, supporting Hypotheses H5 and H6. This pattern is consistent with the substitution logic in resource bricolage, whereby richer local resources reduce SMEs’ reliance on platform enabled resource mobilization [9,65,66,67,68,69].

A t-test on the standardized regression coefficients (|t| = 0.086, p > 0.05) shows that, although both the breadth and depth of DPP are negatively moderated by tourism resource abundance, there is no significant difference in the strength of moderation between them. Therefore, Hypothesis H7 is not supported. In the travel-agency context, both participation breadth and participation depth are closely tied to accessing external tourism resources and coordinating with the supply chain. As a result, TRA may attenuate the performance returns to both forms of participation in a similar manner. Moreover, because TRA is operationalized at the provincial level, this measure is relatively coarse and cannot capture within-province city-level differences or seasonality in tourism activity. This may introduce measurement error and, statistically, attenuate the estimated difference between the two interaction effects.

To more clearly reflect the moderating effect of tourism resource abundance in the relationships between the breadth and depth of DPP and the performance of SMTAs, simple slope plots were drawn (see Figure 2 and Figure 3), where high and low levels of tourism resource abundance are represented by the mean plus or minus one standard deviation, respectively, and high and low levels of the breadth and depth of DPP are also represented accordingly. As tourism resource abundance increases, the effects of both the breadth and depth of DPP on SMTAs’ performance gradually weaken. This indicates that tourism resource abundance has a negative moderating effect on the relationships between the breadth and depth of DPP and the performance of SMTAs.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of tourism resource abundance on the relationship between the breadth of DPP and SMTAs’ performance.

Figure 3.

Moderating effects of tourism resource abundance on the relationship between the depth of DPP and SMTAs’ performance.

4.4. Further Analysis: Platform Participation Combinations and SME Performance

Given the relatively low entry barriers of digital platforms, Chinese SMTAs typically participate in multiple types of platforms and tend to combine platforms with different functions to achieve the combined utilization of resources. Prior research indicates that selective bricolage—i.e., participating in specific digital platforms and increasing the depth of DPP—is more effective than parallel bricolage—i.e., engaging more in multiple types of digital platforms [48]. Therefore, this section further explores the impact of platform participation portfolios on the performance of SMTAs, which helps SMEs identify which combinations of platforms are more effective for deep participation.

Referring to the Classification and Grading Guidelines for Internet Platforms issued by the China State Administration for Market Regulation (https://www.samr.gov.cn/) (accessed on 27 September 2024) and considering the similarities in the resources bricolaged across different digital platforms, this study categorizes digital platforms into three major types:

Transaction-Oriented Platforms: Transaction-oriented platforms include online travel agency platforms, e-commerce platforms, and lifestyle service platforms. These platforms provide technical and algorithmic resources to enhance transaction efficiency and expand transaction channels for SMTAs [87].

Information-Oriented Platforms: Information-oriented platforms comprise social media platforms and news and information platforms. These platforms help SMTAs expand their consumer reach and promote products and services [59,88].

Government-Oriented Platforms: Given the significant role of the Chinese government in the ownership and operation of scenic spots, government-oriented platforms include attraction operation platforms and government-led platforms.

Among the sample, 53.6% of SMTAs engaged in all three platform types above, 45.1% participated in two types, and only about 1% participated in a single platform type. For the subset of SMTAs participating in two platform types (N = 145), combination analysis was conducted to create three dummy variables: transaction and information-oriented platforms, information and government-oriented platforms, and transaction and government-oriented platforms.

According to Model 7 in Table 5, simultaneous participation in transaction-oriented and information-oriented platforms significantly improves the performance of SMTAs (β = 0.323, p < 0.01). However, Models 8 and 9 show that the combination of information-oriented and government-oriented platforms (β = −0.158, p > 0.05) and the combination of transaction-oriented and government-oriented platforms (β = −0.117, p > 0.05) do not have significant effects on the performance of SMTAs.

Table 5.

Regression analysis results.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

Digital platforms can serve as readily accessible “resources at hand” for resource constrained SMEs, helping them partially compensate for resource disadvantages [9]. Drawing on resource bricolage theory, this study examines how digital platform participation is associated with SME performance in the context of small and medium-sized travel agencies. The results indicate that both participation breadth and participation depth are positively associated with performance, while the association for depth is significantly stronger. Interpreted through the bricolage lens, this pattern suggests that a more focused participation strategy, characterized by sustained engagement and concentrated inputs, is more conducive to identifying, integrating, and recombining platform enabled resources than a strategy that spreads scarce resources across many platforms [9,48,49].

Second, the findings provide evidence that value co-creation is an important mechanism linking participation depth to performance. In contrast, the indirect association via breadth is not significant, which is theoretically plausible in resource constrained SMEs: broader participation may expand exposure and potential interaction opportunities, yet it can disperse managerial attention and operational inputs, making it difficult to sustain relational investment and coordinated co-creation activities across platforms [3,9,61,89]. By comparison, deeper participation is more closely aligned with frequent interaction and relational embeddedness, which facilitates the accumulation and recombination of informational and relational resources and is thus more likely to translate platform engagement into realized co-creation outcomes and performance benefits [62,63,64,90].

Third, external resource abundance weakens the positive association between digital platform participation and performance for both breadth and depth. This pattern is consistent with a substitution logic in which richer local resources reduce SMEs’ reliance on platform enabled resource mobilization and relationship building [65,66,67,68,69,91]. In the travel agency context, both breadth and depth are closely tied to accessing external tourism resources and coordinating with the supply chain, which may lead resource abundance to attenuate the two associations in a broadly similar manner. Moreover, because tourism resource abundance is measured at the provincial level, the relatively coarse operationalization may introduce measurement noise and make differences between moderation effects harder to detect.

Finally, the associations of platform participation portfolios with performance vary across platform type combinations. It is worth noting that these portfolio regressions are estimated on a subsample and do not simultaneously control for participation depth; therefore, the results should be interpreted as associational evidence rather than causal effects. Participation in both transaction oriented and information oriented platforms is associated with higher performance, which may reflect complementarity between transaction functions and information and marketing functions [92,93]. By contrast, portfolio combinations involving government oriented platforms show negative but insignificant associations. A plausible explanation is that many government platforms are designed primarily for regulatory and information disclosure purposes, so their use may support compliance and procedural efficiency but is less directly linked to short-term revenue outcomes [94]. In addition, limited operational capacity and service design constraints on some government platforms may reduce their usefulness for SMEs and weaken their association with performance outcomes [95,96].

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, prior research has established that SMEs can benefit from participating in digital platforms, yet platform participation is often operationalized as a single construct and digital platforms are frequently treated as a homogeneous category or examined within a single platform type [18,19]. By distinguishing participation breadth from participation depth and further differentiating platform types into transaction-oriented, information-oriented, and government-oriented categories [20,21,22], this study provides a more fine-grained account of how SMEs’ platform participation is associated with performance. In doing so, the study extends existing work on DPP and SME performance by showing that different participation dimensions and platform portfolios may exhibit systematically different performance implications.

Second, building on resource bricolage theory [9], this study elucidates a theoretically grounded mechanism through which DPP is linked to SME performance by highlighting the mediating role of value co-creation [51,52]. While prior studies have emphasized digital platforms mainly from perspectives such as transaction cost economics and efficiency oriented explanations, the bricolage lens focuses on how resource constrained SMEs “make do” with resources at hand and recombine them to create value [9]. Our findings indicate that deeper participation is more strongly associated with realized value co-creation and performance, which helps clarify when and how platform engagement is translated into performance relevant outcomes. This distinction between broad versus deep participation also refines the application of bricolage logic to digital contexts by linking participation patterns to different resource mobilization and recombination processes.

Finally, this study advances understanding of boundary conditions by incorporating external resource abundance as a moderator of the DPP performance relationship. Prior research suggests that SMEs’ outcomes are shaped not only by internal resource constraints but also by the availability of external resources that vary across regions [31,65,66,67,68,69]. Our results support a substitution based interpretation in which abundant local external resources can reduce SMEs’ reliance on platform enabled resource mobilization, thereby weakening the performance relevance of DPP. By theorizing and testing this external resource boundary condition, the study extends the resource bricolage perspective beyond a purely firm level focus and offers new insights into how local resource environments shape the effectiveness of platform based bricolage.

5.3. Managerial Implications

First, SME managers should treat digital platforms as strategic operational infrastructures rather than as optional marketing channels, and prioritize deepening participation in a limited set of focal platforms. In practice, this implies establishing clear ownership and routines for platform operations, such as a fixed content-update schedule, standardized response procedures for customer inquiries and reviews, and periodic monitoring of key platform analytics to guide iterative adjustments. Given resource constraints, SMEs should allocate scarce managerial attention and budget to activities that strengthen sustained engagement, rather than spreading effort thinly across many platforms.

Second, SMEs should configure their platform portfolios in a more deliberate manner. Consistent with the portfolio results, combining transaction oriented platforms with information oriented platforms is likely to be more beneficial than using either type in isolation, because these platforms complement each other in converting marketing exposure into transactions. Accordingly, SMEs can use information oriented platforms to generate demand and customer leads, and transaction oriented platforms to facilitate booking, payment, and service delivery, while tracking simple funnel metrics such as lead conversion and repeat purchase rates to evaluate effectiveness. By contrast, engagement with government oriented platforms may be maintained primarily for compliance and information access, and SMEs should avoid allocating disproportionate operational resources to these platforms when the primary objective is revenue growth.

Third, SME managers should actively build value co-creation routines with key stakeholders on platforms. Because realized value co-creation depends on sustained interaction, SMEs should move beyond one off communication and implement concrete collaborative practices, such as collecting structured customer feedback for service redesign, co-developing service bundles with upstream suppliers, and coordinating with complementary agencies for joint promotions during peak seasons. These practices can help translate platform engagement into trust, service improvement, and relationship based resources, thereby supporting performance outcomes.

Fourth, the results suggest that external resource conditions should inform platform strategy. In resource scarce regions, SMEs may rely more heavily on digital platforms to overcome local limitations in market traffic and partner access; therefore, deep participation and cross-platform coordination can be particularly important. In resource abundant regions, SMEs should be more selective and focus on differentiating services and improving operational efficiency on focal platforms, rather than simply expanding platform presence.

Finally, the findings also imply opportunities for policymakers and platform providers. Policymakers can improve the usefulness of government oriented platforms by strengthening service functions that SMEs can directly use, such as standardized digital onboarding, training programs on platform operations, and integration with mature commercial platforms for traffic and transaction support. Platform providers can support SME development by lowering operational barriers, offering lightweight analytics and customer management tools, and designing features that facilitate value co-creation, such as supplier matching, co-marketing functions, and structured feedback modules.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, the research sample is based only on data from Chinese SMTAs. Moreover, the travel agency context has distinctive platform-use logics, including intensive customer interaction, supply chain coordination, and pronounced seasonality, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other sectors. Although China is one of the world’s major tourist destinations and has tens of thousands of SMTAs, cross-country differences in platform ecosystem maturity and governance, institutional and regulatory environments for SMEs, and the role of government-oriented platforms may constrain the external validity of the results beyond China. Future research could replicate and extend this study using cross-country comparative designs across different institutional contexts and platform governance regimes, and further test whether the relative roles of participation breadth and depth vary across sectors.

Second, the data are mainly self-reported by SME owners or managers. This cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish temporal ordering and to capture dynamic changes in SMEs’ digital platform participation and related outcomes, and it constrains causal interpretation. Although procedural and statistical remedies were implemented to diagnose common method bias, residual single-source bias cannot be fully ruled out. In addition, the study does not incorporate multi-source evidence, such as platform analytics, customer engagement indicators, objective performance records, or archival data, nor does it use multi-informant assessments from different organizational roles. These complementary sources could strengthen construct validation and reduce the influence of respondents’ perceptual biases. Future research could adopt longitudinal designs that separate the measurement of key constructs over time, for example, by measuring digital platform participation first and capturing value co-creation and performance at later points, to better assess lagged effects and the proposed mechanism. Future work could also triangulate survey responses with objective indicators, such as sales growth, booking conversion rates, platform traffic, or customer ratings, and collect outcomes from secondary sources where feasible. Moreover, combining large-sample analyses with qualitative case studies and mixed-method triangulation could provide richer process evidence, clarify why certain effects differ across platform portfolios, and offer stronger support for both theory and practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and F.Y.; methodology, F.Y.; software, S.M.; validation, S.M. and F.Y.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M.; resources, S.M.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and F.Y.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, F.Y.; project administration, S.M. and F.Y.; funding acquisition, F.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 20BGL008.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of the Business School at Hohai University (protocol code 24050702and date of approval 7 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Sample.

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Sample.

| Category | Options | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Cumulative Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise Nature | State-owned enterprises (including state-controlled enterprises) | 3 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Foreign-funded enterprises (including Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan investment) | 7 | 2.18 | 3.12 | |

| Private enterprises | 297 | 92.52 | 95.64 | |

| Collective enterprises | 14 | 4.36 | 100.00 | |

| Enterprise Size | Medium | 9 | 2.80 | 2.80 |

| Small | 245 | 76.32 | 79.13 | |

| Micro | 67 | 20.87 | 100.00 | |

| Enterprise Age | Less than 3 years | 45 | 14.02 | 14.02 |

| 3~5 years | 204 | 63.55 | 77.57 | |

| 5~8 years | 53 | 16.51 | 94.08 | |

| More than 8 years | 19 | 5.92 | 100.00 | |

| Region | Northeast China | 26 | 8.10 | 8.10 |

| East China | 78 | 24.30 | 32.40 | |

| Central China | 24 | 7.48 | 39.88 | |

| North China | 60 | 18.69 | 58.57 | |

| South China | 47 | 14.64 | 73.21 | |

| Northwest China | 38 | 11.84 | 85.05 | |

| Southwest China | 48 | 14.95 | 100.00 | |

| Total | 321 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Notes: Medium-sized enterprises: Fewer than 300 employees Small enterprises: Fewer than 100 employees Micro-enterprises: Fewer than 10 employees.

References

- Zhang, F.; Yang, B.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, L. Does bricolage serve as a path to disruptive innovation for SMEs in dynamic environments? The contradictory roles of managerial ties. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2025, 125, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inegbedion, H.E.; Thikan, P.R.; David, J.O.; Ajani, J.O.; Peter, F.O. Small and medium enterprise (SME) competitiveness and employment creation: The mediating role of SME growth. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shouk, M.A.; Lim, W.M.; Megicks, P. Using competing models to evaluate the role of environmental pressures in ecommerce adoption by small and medium sized travel agents in a developing country. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, S.; Chaudhary, M. Are small travel agencies ready for digital marketing? Views of travel agency managers. Tour. Manag. 2020, 79, 104078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Knowledge complexity and firm performance: Evidence from the European SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nemar, S.; El-Chaarani, H.; Dandachi, I.; Castellano, S. Resource-based view and sustainable advantage: A framework for SMEs. J. Strateg. Mark. 2025, 33, 798–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Yan, R.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X. Supply chain specific investments and enterprise performance of SMEs: A resource orchestration perspective. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 5487–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chan, H.K.; Cai, Z. Towards a theoretical framework of co-development in supply chains: Role of platform affordances and supply chain relationship capital. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2024, 39, 1029–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quansah, E.; Moghaddam, K.; Solansky, S.; Wang, Y. Strategic leadership in SMEs: The mediating role of dynamic capabilities. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022, 43, 1308–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhai, X. The performance improvement mechanism of cross-border E-commerce grassroots entrepreneurship empowered by the internet platform. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Huang, H.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, H. Investigating the effects of digital platform participation on B&B performance: An organizational learning perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 121, 103806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballerini, J.; Herhausen, D.; Ferraris, A. How commitment and platform adoption drive the e-commerce performance of SMEs: A mixed-method inquiry into e-commerce affordances. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 72, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Han, Y.; Anderson, A.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. Digital platforms and SMEs’ business model innovation: Exploring the mediating mechanisms of capability reconfiguration. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 65, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yang, J.; Gai, J. How digital platform capability affects the innovation performance of SMEs-Evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaithambi, S.; Ravi, L.; Devarajan, M.; Almazyad, A.S.; Xiong, G.; Mohamed, A.W. Enhancing enterprises trust mechanism through integrating blockchain technology into e-commerce platform for SMEs. Egypt. Inform. J. 2024, 25, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Quan Chau, T.L.; Vo Nhu, Q.P.; Ferreira, J.J. Digital platforms and SMEs’ performance: The moderating effect of intellectual capital and environmental dynamism. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 3155–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, A.A.; Sheng, M.L. The digitalization of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs): An institutional theory perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2022, 60, 1288–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Yang, Y.S.; Ghauri, P.N.; Park, B.I. The impact of social media and digital platforms experience on SME international orientation: The moderating role of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Manag. 2022, 28, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonina, C.; Koskinen, K.; Eaton, B.; Gawer, A. Digital platforms for development: Foundations and research agenda. Inf. Syst. J. 2021, 31, 869–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.G.; Kang, C.M.; Jeon, S.M. An innovative framework to classify online platforms. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 31, 59–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, X.; Fang, Y. Evolution of spatial mismatch between tourism resource abundance and tourism network attention in Sichuan Province and analysis of influencing factors. Tour. Sci. 2023, 37, 43–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y. Interaction between the introduction strategy of the third-party online channel and the choice of online sales format. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2022, 29, 2448–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Ma, H.; Zhao, M.; Fan, T. Group Buying Pricing Strategies of O2O Restaurants in Meituan Considering Service Levels. Systems 2023, 11, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozak, H.A.; Adhiatma, A.; Fachrunnisa, O.; Rahayu, T. Social media engagement, organizational agility and digitalization strategic plan to improve SMEs’ performance. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 3766–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Sotiriadis, M.; Shen, S. Using TikTok in tourism destination choice: A young Chinese tourists’ perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 20230166173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Lin, Y.C.; Chen, W.H.; Chao, C.F.; Pandia, H. Role of government to enhance digital transformation in small service business. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.; Oliveira, F. The tourism intermediaries’ profitability in Portugal and Spain-differences and similarities. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 5, 1101–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mansilla, O.L.; Serra-Cantallops, A.; Berenguer-Contri, G. Effect of value co-creation on customer satisfaction: The mediating role of brand equity. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.W.; Zhang, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, T.C.; Tsai, C.L. The effect of tourism core competence on entrepreneurial orientation and service innovation performance in tourism small and medium enterprises. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikirya, B.; Zhou, C. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of high-level tourist attractions in China: A case study of 9296 A-level tourist attractions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, R.; Yarnold, J.; Pushpamali, N.N.C. Circular economy 4 business: A program and framework for small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) with three case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Su, X.; Zhu, R. The role of bricolage in countering resource constraints and uncertainty in start-up business model innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 2862–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, R.; Morris, W. Digital entrepreneurship in agrifood business: A resource bricolage perspective. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2024, 30, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, C.; Liu, X. Rethinking value co-creation and loyalty in virtual travel communities: How and when they develop. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 69, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.L.; Chen, K.Y.; Wang, L.H.; Yeh, S.S.; Huan, T.C. Exploring the impact of social media platform image on hotel customers’ visit intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 4206–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G. The importance of digital marketing in the tourism industry. Int. J. Res.-Granthaalayah 2017, 5, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeloni, S.; Rossi, C. Online search engines and online travel agencies: A Comparative Approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 720–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, P.; Henfridsson, O.; Parker, G.G. Introduction-platforms and infrastructures in the digital age. Inf. Syst. Res. 2018, 29, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Pesämaa, O.; Wincent, J.; Westerberg, M. Network capability, innovativeness, and performance: A multidimensional extension for entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Huan, T.C. Explore how SME family businesses of travel service industry use market knowledge for product innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 151, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, T.; Stangl, B.; Schegg, R.; Liebrich, A. The return on tourism organizations’ social media investments: Preliminary evidence from Belgium, France, and Switzerland. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2017, 17, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, F.Y.; Chien, Y.Y. Digital Internationalization of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises: Online Comments and Ratings on Amazon Platform. J. Compet. 2024, 16, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, B.; Martinsuo, M.; Härkälä, J. Small and medium-sized manufacturers’ ways of involving suppliers in digitally-enabled services. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 36, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Hui, X.; Lyu, C. The more engagement, the better? The influence of supplier engagement on new product design in the social media context. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 64, 102475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, C.; Dowling, M. Firm networks: External relationships as sources for the growth and competitiveness of entrepreneurial firms. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2003, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Li, Z. Is there any difference in the impact of digital transformation on the quantity and efficiency of enterprise technological innovation? Taking China’s agricultural listed companies as an example. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, S.; Sarkar, S. Bricolage-A systematic review, conceptualization, and research agenda. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2024, 36, 833–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, T.E.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Decision weaving: Forming novel, complex strategy in entrepreneurial settings. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 2275–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, F.; Wang, N. Strategic orchestration in sharing economies: A configurational analysis of platform differentiation and governance alignment. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, V.; Kohli, R. Cocreating IT value: New capabilities and metrics for multifirm environments. Mis Q. 2012, 36, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglia, G.; Pera, R.; Bigné, E. The determinants of stakeholder engagement in digital platforms. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkarainen, M.; Kemppainen, L.; Xu, Y.; Jansson, M.; Ahokangas, P.; Koivumäki, T.; Gu, H.H.; Gomes, J.F. Resource integration capabilities to enable platform complementarity in healthcare service ecosystem co-creation. Balt. J. Manag. 2022, 17, 688–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissemann, U.S.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.W.; Fu, H.P.; Lin, A.J. Critical success factors and implementation strategies for B2B electronic procurement systems in the travel industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2023, 14, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.L.; Shen, C.C.; Lin, C.N. Effects of internet technology on the innovation performance of small-scale travel agencies: Organizational learning innovation and competitive advantage as mediators. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 1830–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvily, B.; Zaheer, A. Bridging ties: A source of firm heterogeneity in competitive capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D. Alliance portfolios and firm performance: A study of value creation and appropriation in the US software industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1187–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Deng, L.; Deng, Q.; Law, R. How consumers react to online reviews and managerial responses from marked source channels on an accommodation-sharing platform? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2025, 55, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, C.; Russo Spena, T.; Colurcio, M. Co-creating value innovation through resource integration. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2010, 2, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Takahashi, V.P. Analysis of front end dynamic in the value co-creation with multiple stakeholders. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2022, 15, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B.; Lancaster, R. Relational embeddedness and learning: The case of bank loan managers and their clients. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partouche-Sebban, J.; Rezaee Vessal, S.; Bernhard, F. When co-creation pays off: The effect of co-creation on well-being, work performance and team resilience. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 1640–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appio, F.P.; Cacciatore, E.; Cesaroni, F.; Crupi, A.; Marozzo, V. Open innovation at the digital frontier: Unraveling the paradoxes and roadmaps for SMEs’ successful digital transformation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, R.J.B.; Kim, D.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Cavusgil, E. The effect of business model innovation on SMEs’ international performance: The contingent roles of foreign institutional voids and entrepreneurial orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 175, 114449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Qi, Y.; Yu, B. Effects of Domestic and International External Collaboration on New Product Development Performance in SMEs: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Yang, Q. Policy involvement and policy consistency identification of supportive policies for SMEs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2024, 20, 2901–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeh, J.; Nuhu, N.; Tajeddin, M.; Simba, A. Dealing with adversity: Innovation among small and medium-sized enterprises in developing economies. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2024, 30, 2578–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Martinez, L.J.; Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Kallmuenzer, A. Untangling the relationship between small and medium-sized enterprises and growth: A review of extant literature. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Tabares, S.; Parida, V. Small and medium-sized enterprises and the circular economy: Leveraging ecosystem strategies for circular business model implementation. Organ. Environ. 2025, 38, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, J.; Zhao, W. Building dynamic capabilities of small and medium-sized enterprises through relational embeddedness: Evidence from China. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 2859–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunghez, C.L. Marketing strategies of travel agencies: A quantitative approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J. Response of travel agencies in China to COVID-19: Disaster sensemaking, adaptation, and resilience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 3381–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Leung, R.; Lo, A.; Leung, D.; Fong, L.H.N. Distribution channel in hospitality and tourism: Revisiting disintermediation from the perspectives of hotels and travel agencies. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Craig, S.B. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.K.; Meade, A.W. Dealing with careless responding in survey data: Prevention, identification, and recommended best practices. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. Nudging interactive cocreation behaviors in live-streaming travel commerce: The visualization of real-time danmaku. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 52, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Opreana, A. Measuring customer engagement in social media marketing: A higher-order model. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2633–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmawla, M.; Imperiale, F.; Fasiello, R. Fetching the ‘exterior’ ‘in’: Effects of an alliance’s collaborative governance and collaborative accountability on hotel innovation performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 122, 103848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poretti, C.; Weisskopf, J.P.; de Régie, P.D.V. Innovative business strategies, corporate performance, and firm value in the travel and leisure industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 118, 103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnins, A. Multicollinearity: How common factors cause Type 1 errors in multivariate regression. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2362–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Exploring the determinants of E-loyalty among travel agencies. Serv. Ind. J. 2008, 28, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Ma, J. Online platform use and performance among listed tourism companies in China. J. Travel Res. 2024, 63, 1709–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo-Vela, M.; Frau, M.; Ferrer, A. The role of value co-creation in building trust and reputation in the digital banking era. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2375405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, P.R.; Baker, T.; Davidsson, P.; Senyard, J.M. When is less more? Boundary conditions of effective entrepreneurial bricolage. J. Manag. 2023, 49, 1277–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Peng, A.Y. Why do people choose different social media platforms? Linking use motives with social media affordances and personalities. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2023, 41, 330–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Rowe, F.; Branagan, E. Going digital? The impact of social media marketing on retail website traffic, orders and sales. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Huang, C.; Duan, L. The concept of smart tourism in the context of tourism information services. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y. Whether the construction of digital government alleviate resource curse? Empirical evidence from Chinese cities. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhong, R.; Wei, C. Measuring digital government service performance: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 83, 102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.