1. Introduction

With rapid global economic growth and accelerated industrialization, the world is facing a series of resource and environmental challenges, culminating in a continuous deterioration of the ecological environment [

1,

2,

3]. China, as the most populous developing nation, is also facing progressively worsening environmental issues amid sustained rapid socio-economic development, industrialization, and urbanization. The transition to a “consumer society” has heightened the importance of environmental governance from the consumption side. Research findings indicate that individual consumption behavior accounts for over 30% of environmental damage [

4,

5], and experts posit that ecological deterioration might escalate should unsustainable consumption patterns persist [

6,

7]. Concurrently, environmentally conscious consumers are emerging as an increasingly significant market force, prompting a rising number of enterprises to actively expand their green product offerings and leverage social media platforms (i.e., Weibo, WeChat, and Twitter—now X) for green marketing. Social media advertising not only significantly shapes consumers’ perceptions and attitudes toward green products [

8] but also serves as a crucial channel for companies to expand their market share. Clarifying the strategic significance of eco-friendly marketing within social media ecosystems and investigating how digital advertising and interpersonal networks influence consumers’ green purchasing behaviors therefore hold substantial theoretical and practical value.

Content optimization and effectiveness mechanisms of social media green advertising represent the primary focuses of current research efforts, exploring how it attracts consumers and builds trust [

9,

10]. Research is also directed toward the factors influencing consumer attitudes toward green advertising and their potential effects [

11,

12]. The results of studies on social media interpersonal influence indicate that online interactions can accelerate consumers’ purchasing decisions [

13,

14] and enhance consumers’ sense of group identity and belonging by promoting information sharing and trust-building [

15,

16]. Notably, green advertising skepticism suggests that consumers often do not fully trust advertisements and instead seek other references [

12]. The perspectives provided by social media interpersonal influence, which are more easily accepted, precisely meet this need. Therefore, establishing a theoretical connection between green advertising, social media interpersonal influence, and green consumption is of particular importance.

Influencer marketing has gained traction as an innovative approach, demonstrating significant sales effectiveness through live streaming and short videos that showcase and recommend products on shopping platforms [

17]. Previous studies provide evidence that influencer endorsements rely not only on appeal and professionalism but are also closely tied to personal character and social responsibility [

18]. Although the effectiveness of influencer endorsements in the field of green consumption remains inconclusive, their promotion of green products as a form of social responsibility enhances their own image and strengthens consumer trust and reliance [

19]. Therefore, exploring the impact of influencer endorsements on green purchasing decisions holds significant guiding importance for businesses in formulating related marketing and green development strategies.

Members of Generation Z (born between 1995 and 2010), referred to as “digital natives,” grew up during the rapid development of Internet technology and possess an inherent affinity for digital media [

20]. They spend considerable time daily on social media, frequently encountering advertisements and engaging in online social interactions. Research findings indicate that this group exhibits a stronger sense of responsibility and ethical awareness, holds stronger environmental values, and is more inclined to make green purchasing decisions [

21,

22]. Additionally, the enthusiasm and impulsiveness displayed by Generation Z in celebrity fandom contribute to their higher acceptance of influencer endorsements [

23,

24]. As Generation Z gradually becomes a significant force in the consumer market [

21], in-depth analysis of their consumption characteristics and market impact is crucial.

At present, research on how social media green advertising and online interpersonal influence jointly affect green consumption behaviors remains insufficient. Three critical research gaps persist in the existing literature. First, although social media green advertising and online interpersonal influence have been individually demonstrated to independently affect green consumption, their synergistic impact mechanisms within the digital marketing ecosystem have yet to be systematically elucidated. Second, while online celebrity endorsement has proven influential in the broader e-commerce context, its theoretical positioning as a conditional moderating variable in green consumption scenarios remains ambiguous. Third, although researchers have examined the consumption characteristics of Generation Z, empirical evidence on how this cohort differentially responds to green influencer marketing remains lacking.

In response to these gaps, in this study, we aim to address several pivotal research questions within the context of Chinese social media: How do green advertising and online interpersonal influence drive green consumption behaviors through the mediating role of attitude? How does online celebrity endorsement moderate the conversion of attitudes into behavioral intentions? Do Generation Z consumers amplify this moderating effect, and if so, through what mechanisms?

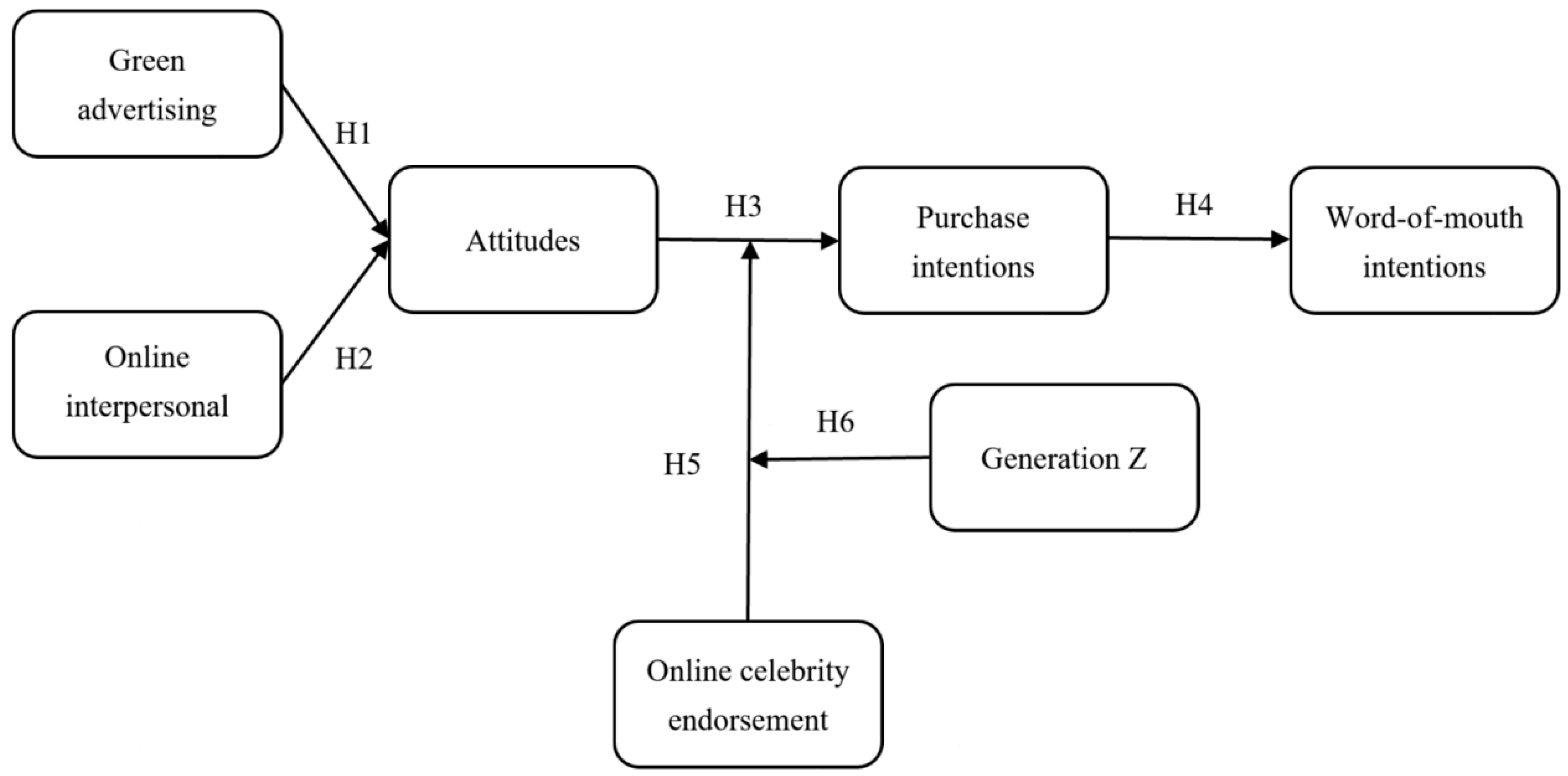

Grounded in the SOR framework, while its applicability to green consumption contexts has been supported by existing studies [

12], this study is conducted within the context of Chinese social media ecosystems (e.g., WeChat and Weibo) with the aim of achieving three primary analytical objectives: First, to empirically examine the mechanism through which social media stimuli (green advertising and online interpersonal influence) affect consumer responses (green purchase and word-of-mouth intentions) via the organismic state (attitude). Second, to investigate the conditional role of online celebrity endorsement in moderating the attitude–purchase intention link. Third, to explore the generational boundary effect by examining whether Generation Z consumers amplify the aforementioned moderating effect.

The findings of this study contribute to digital green marketing as follows. First, we empirically test an integrated Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) mechanism within the social media context, simultaneously modeling green advertising and online interpersonal influence as stimuli and tracing their sequential impact through attitudes to purchase and word-of-mouth intentions, offering a more holistic understanding of digital pathways to green consumption. Second, we clarify the conditional role of online celebrity endorsement by demonstrating that the attitude–purchase intention link strengthens with higher levels of influencer endorsement, positioning it as a key boundary condition in converting attitudes into behavioral intent. Third, we identify a generational boundary effect, showing that Generation Z consumers significantly amplify this moderating effect, underscoring the need for segment-specific models and strategies in green marketing and advancing the understanding of consumer heterogeneity in sustainable consumption.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

To test the research hypotheses within the Chinese social media context, we employed stratified random sampling to ensure demographic diversity. The stratification was based on three key demographic variables reported by the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC): geographic region (East, Central, or West), age group (18–24, 25–35, or 36–45), and gender (male or female). Quotas were set proportionally to the latest CNNIC Internet user statistics. The electronic questionnaire was administered through China’s leading professional survey platform, Questionnaire Star, from June 20 to August 20, 2025. The platform’s built-in sampling tool was used to recruit participants from its panel based on the predefined strata. To broaden reach, survey links were also disseminated through social media (Weibo

https://www.weibo.com, accessed on 20 June 2025 and WeChat Moments

https://wx.qq.com, accessed on 20 June 2025); however, primary data collection was channeled through the Questionnaire Star panel (

https://www.wjx.cn, accessed on 20 June 2025) to maintain randomization and minimize self-selection bias. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged between 18 and 45, (2) self-reported daily use of social media (e.g., Weibo, WeChat, and Xiaohongshu

https://www.xiaohongshu.com, accessed on 20 June 2025) for more than 3 years, and (3) residency in mainland China. Exclusion criteria included incomplete responses and patterned answering (e.g., straight-lining). An initial screening question in the survey verified the social media usage criterion.

First, prior to administering the survey, respondents received a brief introduction to green products, defined in this study as products whose manufacturing processes pose no risk to environmental health or human well-being. To facilitate comprehension, specific examples—such as eco-friendly tissues—were provided. Second, a screening question was included to verify that participants were regular social media users with at least three years of experience on platforms such as Sina Weibo. Only those who answered affirmatively were permitted to proceed with the full questionnaire. A total of 650 responses were collected, and after removing submissions with omitted or outlier values, 527 valid questionnaires were retained for analysis, yielding a final response rate of 81.07% (527/650).

Prior to commencing the survey, participants were briefed on its primary purpose and provided with an estimated duration for completion. To reduce potential common method bias, they were explicitly assured that the questions had no right or wrong answers and that all data would be treated with strict confidentiality. As an incentive for participation, each respondent received a monetary reward ranging from 2 to 5 yuan upon successful submission.

The demographic profile of the participants is detailed in

Appendix A Table A1, with a comparative overview of key attributes relative to the broader Chinese online population provided in

Table 1. Among participants, 53.89% were female, compared with a national Internet user gender distribution of 51.2% male and 48.8% female participants, as reported by the China Internet Network Information Center (2024), indicating reasonable representativeness. Approximately 39.47% of respondents belonged to Generation Z (ages 15–30). This figure aligns with the age profile of Chinese Internet users, among whom the 20–29 and 30–39 age groups account for 13.7% and 19.2%, respectively. The median reported household income was approximately 9000 yuan per month. Based on China’s seventh national population census, the average household size is 2.62 persons, and the most recent monthly per capita disposable income is 3278.67 yuan, corresponding to an average household income of roughly 8600 yuan—consistent with the income distribution observed in this sample. Relevant data are sourced from the China Internet Network Information Center, China’s seventh national population census, and the report on “Income and Consumption Expenditure of the Population in the First Half of 2023.”

Additionally, an independent samples t-test was performed to assess potential nonresponse bias by comparing early respondents (those who completed the questionnaire within the first 10 days of data collection) with late respondents (those who responded in the final 10 days). The analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the two groups, indicating that nonresponse bias is unlikely to be a major issue in this study.

3.2. Measures

The survey instrument consisted of two sections: The first involved collecting demographic information from participants (see

Table A1), and the second involved measuring the underlying theoretical constructs (see

Table A2). All latent constructs were evaluated using multi-item Likert scales, which were adapted from well-established measures in the existing literature, with slight modification to suit the specific context of this research. Responses were collected using a scale that ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Scale items were drawn from the following sources: green advertising on social media was derived from the study of Borah et al. [

46]; assessments of eco-friendly product perceptions and purchase intentions were based on the study of Bi et al. [

47]; online interpersonal influence was adopted from the study of Akram et al. [

48]; word-of-mouth intentions were sourced from the study of Yang and Ha [

49]; and online celebrity endorsement items were derived from the study of K. V. et al. [

50]. Statistical results for each item are shown in

Table A3.

To ensure the appropriateness and clarity of the survey, three subject-matter experts were invited to review a preliminary version of the instrument. They evaluated the questionnaire in terms of conceptual clarity, wording precision, length, and overall layout. Incorporating their feedback, we refined item wording to enhance clarity and conciseness, reduced technical jargon, and corrected potential ambiguities, resulting in the final version of the questionnaire.

In addition, a pre-test (n = 32) was conducted with two objectives: (1) to select a representative green product for the main study scenario, and (2) to assess the clarity and face validity of the questionnaire items. For product selection, participants were presented with descriptions and images of six common green products: eco-friendly tissues, energy-saving lamps, zinc–air batteries, energy-saving refrigerators, new energy vehicles, and biodegradable tableware. They evaluated each product on a 7-point scale regarding perceived environmental friendliness, familiarity, and likelihood of online purchase. Eco-friendly tissues scored highest on familiarity and mid-range on environmental friendliness and online purchase likelihood, making them a suitable, relatable product for the diverse sample, and were thus selected. Based on verbal feedback regarding the initial draft questionnaire, minor adjustments were made to the wording of several items to enhance comprehension.

5. Discussion

In terms of the findings on the SOR mechanism and core pathways, the results validate the integrated SOR framework proposed in this study. In support of H1 and H2, both green advertising (β = 0.44) and online interpersonal influence (β = 0.35) were found to be significant stimuli that positively shape consumers’ attitudes toward green products. These findings broaden the applicability of the SOR model within the field of green consumption research [

9,

12] by simultaneously modeling two dominant yet distinct social media stimuli. Consistent with findings presented in the existing literature, both green advertising and online interpersonal influence serve as key informational sources that shape consumers’ attitudes toward green products [

16,

47], particularly given consumers’ susceptibility to external influence in online environments [

23]. Extending prior findings, our findings further demonstrate that green advertising exerts the strongest effect on attitude formation, underscoring its primary role as an information channel on social media—a platform perceived as relatively reliable—thereby effectively fostering both purchase and word-of-mouth intentions.

Furthermore, the sequential chain of organismic and response states was validated. H3 and H4 were supported, demonstrating that positive attitudes strongly translate into purchase intentions (β = 0.74), which in turn drive word-of-mouth intentions (β = 0.63). This sequential validation (attitude → intention → WOM) reinforces the hierarchical logic of the SOR model in the digital domain and aligns with findings on the social diffusion of sustainable behaviors [

14,

29]. It underscores that purchase intention is not an endpoint but a pivotal conduit leading to broader advocacy. Consistent with prior research [

14,

56,

57], when consumers are influenced by social media, they develop positive product attitudes, enhancing perceived product greenness and need fulfillment, thereby increasing purchase likelihood. Positive attitudes also contribute to a more pleasant online shopping experience, further strengthening purchase willingness [

58]. Additionally, social media offers multiple channels for consumers to express opinions about green products, satisfying post-purchase sharing needs and enabling electronic word-of-mouth communication that fosters consensus-building, social connection, and group belonging [

59]. Consequently, purchase intentions positively influence word-of-mouth intentions.

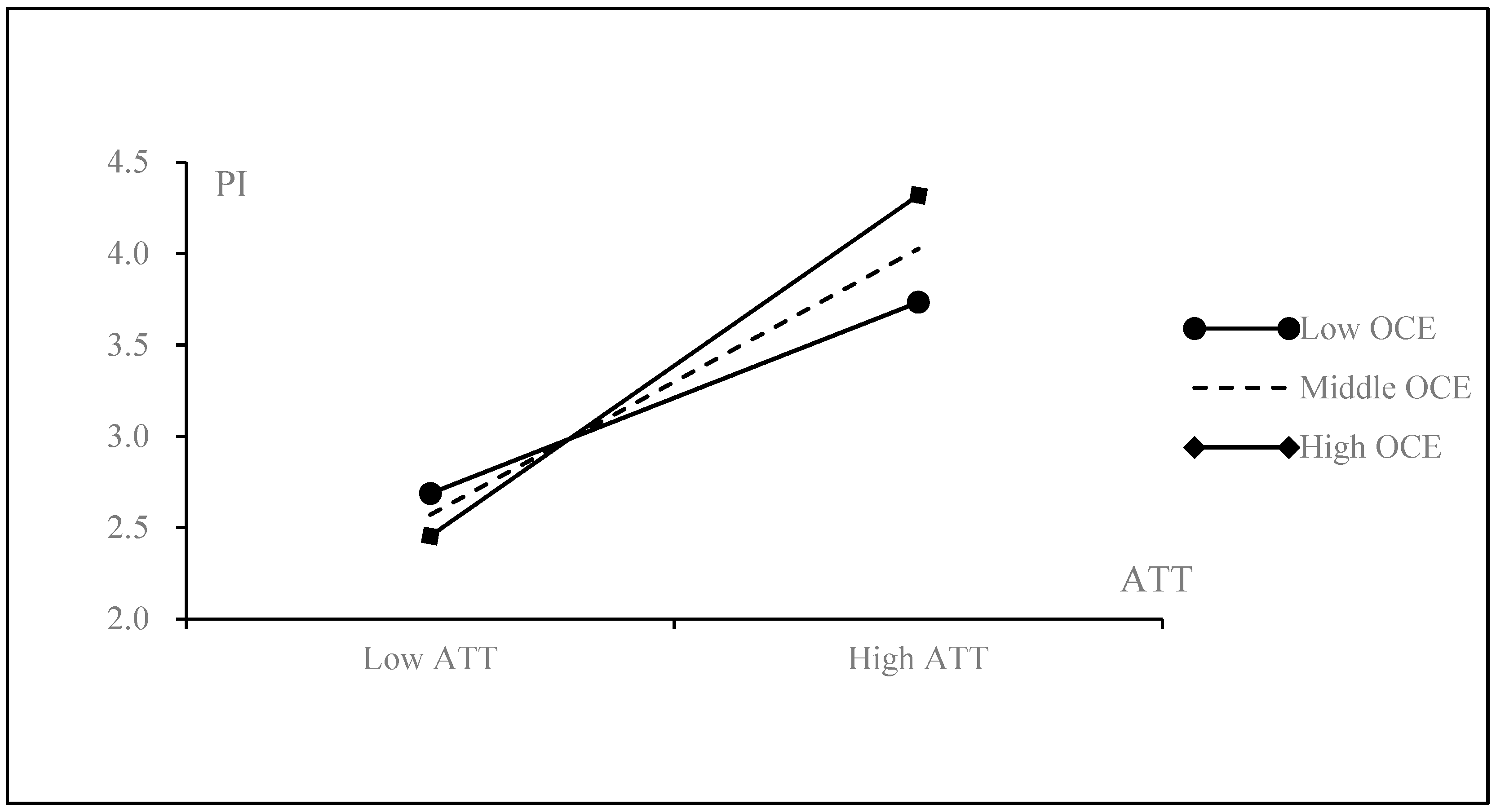

In terms of the conditional role of online celebrity endorsement, our results validated H5, revealing that online celebrity endorsement acts as a significant positive moderator. The simple slope analysis results indicate a 76% (calculated as (0.97–0.55)/0.55 × 100% ≈ 76%) increase in the strength of the attitude–purchase intention link under high versus low endorsement conditions (β_high = 0.97 vs. β_low = 0.55). This finding critically positions online celebrity endorsement not merely as another stimulus, but as a crucial boundary condition that amplifies the conversion of internal evaluations into behavioral intent. Our findings confirm that online celebrity endorsement significantly enhances the relationship between attitudes and purchase intentions. By establishing trust, influencers make consumers more receptive to their recommendations. Specifically, their comprehensive and persuasive product presentations effectively guide hesitant consumers toward purchase decisions [

17]. Consequently, favorable attitudes toward green products are more readily converted into actual purchases, aligning with findings that online celebrity endorsement plays a significant moderating role in consumer decision-making processes [

60].

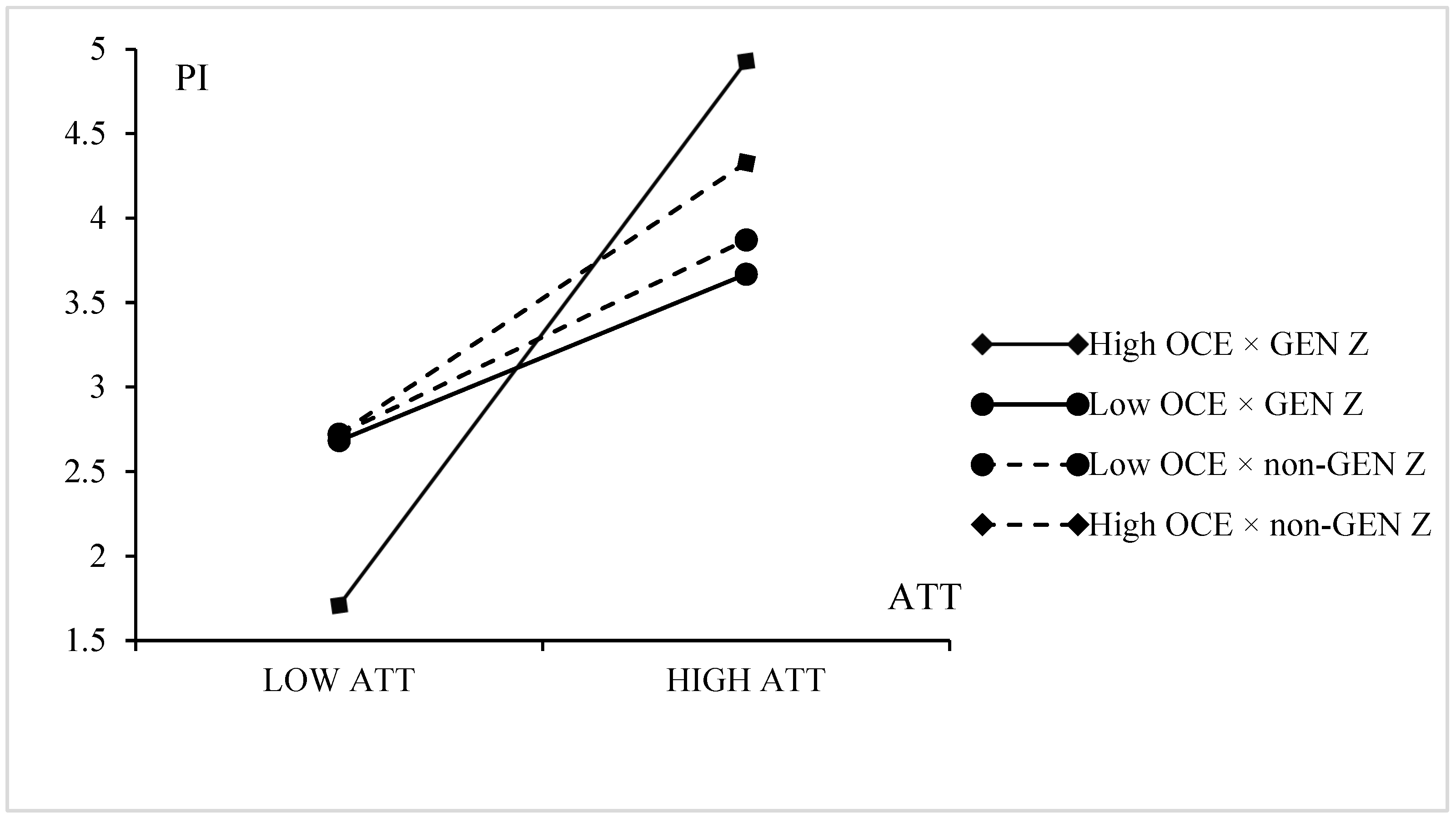

Lastly, in terms of the generational boundary effect, our findings provide support for H6, identifying a significant generational boundary. The moderating effect of online celebrity endorsement was substantially stronger among Generation Z consumers. This finding specifies the “for whom” condition of the proposed mechanism, highlighting that the potency of influencer marketing in green contexts is not universal but contingent upon audience characteristics. It integrates the literature on Generation Z’s digital nativity and social susceptibility [

20,

23] with green consumption research, offering a more nuanced understanding of consumer heterogeneity. The moderating effect of online celebrity endorsement is significantly amplified among Generation Z consumers due to their distinct profile as digital natives and highly engaged social media users. Having matured alongside the concurrent rise of e-commerce and the influencer economy, this cohort exhibits greater social susceptibility and stronger parasocial attachments in digital environments, enhancing their receptiveness to persuasive endorsements from online celebrities [

20]. Their inclination to express affinity for admired figures through consumption further strengthens their responsiveness to influencer-endorsed green products [

61]. Consequently, the conditioning role of online celebrity endorsement on the attitude–purchase intention link is markedly strengthened within this demographic.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Validating and Extending the Integrated SOR Model in the Social Media Context: Supported by empirical evidence for H1–H4, our results confirm the effectiveness of an integrated pathway in which green advertising and online interpersonal influence serve as synergistic stimuli that, mediated by attitude, sequentially drive purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention. The above addresses the limitation of prior research that often focuses on isolated stimuli, providing a more realistic and systematic theoretical framework for understanding how multiple information flows jointly shape green consumption behavior on social media.

Clarifying the Conditional Role of Online Celebrity Endorsement in Green Consumption: The verification of H5 demonstrates that online celebrity endorsement functions not as an independent main-effect stimulus but as a key boundary condition that substantially moderates the strength of the core relationship between attitude and purchase intention (with a moderating effect reaching 76%). This finding precisely redefines the theoretical role of online celebrity endorsement from a general “source of influence” to a “conversion amplifier,” thereby enriching green persuasion theory and filling a research gap regarding the mechanisms of influencer marketing in the domain of sustainable consumption.

Revealing the Generational Boundary Effect of Consumer Heterogeneity: Support for H6 highlights an important generational boundary: the moderating effect of online celebrity endorsement is significantly stronger among Generation Z consumers. This finding moves beyond the traditional view of consumers as a homogeneous group by integrating generational characteristics such as digital nativity and social susceptibility into the green consumption behavior model. It advances theory toward greater segmentation and explanatory power, highlighting the importance of the “for whom” condition in digital marketing theory.

6.2. Practical Implications

The findings offer evidence-based guidance for relevant practitioners. In terms of corporate marketing strategy, it is recommended to strengthen integrated content planning. Given that both green advertising and online interpersonal influence effectively shape attitudes, firms should pursue a dual-track content investment on social media: producing high-quality, credible green advertisements to build product awareness while actively curating and guiding user-generated content to foster positive community interaction. Enterprises should also leverage the amplifying effect of online celebrity endorsement. Since such endorsement substantially enhances the attitude-to-purchase conversion rate, it should be treated as a core conversion tool rather than merely an exposure channel. Prioritizing collaborations with influencers whose values align with the brand’s green ethos and designing in-depth, trustworthy product narratives can maximize this moderating effect. Furthermore, implementing Generation Z-targeted communication is essential. Given this cohort’s pronounced responsiveness to influencer endorsements, green marketing aimed at Gen Z should center on influencers as key touchpoints. Such efforts require a deep understanding of their cultural preferences and communication styles, combined with mechanisms to collect feedback for iteratively refining influencer partnership models and product strategies.

For platforms and policymakers, governance recommendations include empowering constructive green engagement. Social platforms can design features that encourage consumers to share authentic experiences with green products, while also improving mechanisms to identify and manage misleading “greenwashing” information and inappropriate marketing, thereby protecting consumers from misinformation and sustaining a healthy environment for green consumption discourse. Additionally, policy attention should focus on regulating and protecting influencer marketing. In light of the considerable impact of online celebrity endorsements on susceptible groups such as Gen Z, regulators should advance more transparent rules for influencer advertising disclosure and authenticity verification. Concurrently, enhanced protection for minors and young consumers in the digital marketing environment is needed to steer the influencer economy toward responsible influence in the green consumption domain.

6.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be addressed. First, the data are derived from a cross-sectional study. The authors of future studies may benefit from employing longitudinal designs to better capture temporal dynamics among the variables. Second, the study was conducted in China, a cultural setting characterized by strong collectivist values. In subsequent studies, researchers could extend the investigation to other countries to examine whether the current findings are generalizable across different cultural contexts. Third, in the present research, we focus exclusively on consumers’ intentions rather than actual behaviors. While the results of prior studies suggest that intentions can serve as reliable predictors of behavior, self-reported intentions do not equate to observed actions. Thus, the authors of future studies should seek to bridge this gap by examining consumers’ actual engagement in green consumption behaviors.