Abstract

Advertising research highlights the crucial role of creative strategy in shaping consumer behavior. Yet, limited attention has been paid to how creative appeal and message strategy jointly influence persuasion in social media contexts. This study examines the interactive effects of informational versus transformational appeals and personal versus social-experience message strategies on consumer attitudes and purchase intentions. A 2 (creative appeal) × 2 (message strategy) experimental design was implemented using Facebook post advertisements for a fictitious beer brand. Data was collected from 231 participants randomly assigned to one of four ad conditions. Results show that informational appeals outperform transformational appeals in generating immediate purchase intentions. Attitudes toward the ad and attitude toward the brand mediated these effects, consistent with the Dual Mediation Hypothesis. Moreover, in accordance with the Construal Level Theory, message strategy moderates the relationship: informational appeals were most effective when paired with personal strategies but lost persuasive power under social-experience strategies. These findings advance the theoretical understanding of digital advertising persuasion by explicating how creative appeal and message strategy jointly shape both attitudinal and behavioral responses. Practically, the results suggest that advertisers seeking short-term conversions should combine informational appeals with personal strategies.

1. Introduction

Despite the remarkable growth of social media advertising, with global spending surpassing $200 billion in 2024, advertisers are increasingly frustrated with disappointing engagement and conversion outcomes [1,2]. While sponsored posts achieve high visibility, they often fall short in terms of generating meaningful interactions, leading to relatively low click-through and purchase rates [3]. This disconnect highlights the challenges brands face in effectively connecting with their audience in an era where social media is a dominant force in brand communication. In this context, advertisers continue to struggle with a persistent dilemma: whether to emphasize factual, utilitarian benefits to prompt immediate purchase decisions or rely on emotional, experiential messaging to build long-term brand attitudes [4]. Recent research suggests that this is not a simple dichotomy between logic and emotion but rather a dynamic interplay of cognitive and affective processes that jointly shape persuasion [5].

This challenge is particularly acute in social media, where billions of branded messages compete for attention and where success depends not only on the creative appeal of an ad but also on how its message is strategically framed to resonate with personal or social motivations [6,7]. Social platforms amplify both rational and emotional cues, inviting consumers to process advertising messages through both immediate, heuristic responses and reflective evaluations. In such emotionally charged environments, the balance between information and feeling becomes crucial for effective persuasion [3,8].

Consequently, understanding how creative execution and message framing interact in shaping persuasion outcomes remains a central and unresolved question for both advertising theory and practice [8,9].

A central focus in advertising research is to explicate the mechanisms through which advertising influences consumer intentions and behaviors. The process of creating an advertisement typically involves two complementary components: the message strategy, which conveys the brand’s key benefit to the target audience, and the creative appeal, which determines how this benefit is delivered through executional styles [10,11]. Creative appeals are generally classified into two main types: informational and transformational [6,10]. Informational creative appeals provide objective, fact-based content about products, promoting cognitive engagement, while transformational appeals evoke emotions and associations, fostering affective engagement [12]. However, growing evidence suggests that emotional content, when integrated thoughtfully rather than used as a mere attention grabber, can strengthen brand–customer relationships by stimulating identification, empathy, and even mild forms of irrational behavior [5] From this perspective, creative appeal becomes not only a vehicle of persuasion but also a social and emotional connector between the consumer and the brand.

From the consumer’s perspective, the sequence of processing advertising elements is often reversed. Whereas advertisers first develop the message and then design the creative appeal, consumers usually encounter the advertisement through its creative execution, which initially captures their attention [10]. Following the Hierarchy of Effects Model’s [13,14], when creative appeal succeeds in drawing attention and raising awareness, it can trigger deeper cognitive engagement with the advertisement and encourage an evaluation of the product’s benefits. At the same time, emotional cues can shortcut this sequence, eliciting intuitive judgments that precede rational evaluation and later serve to justify it [5]. Thus, creative appeal functions as both an attention mechanism and an emotional cognitive gateway that shapes consumer attitudes and decisions [8].

While extensive literature discusses how creative appeal influences consumer behavior, it is essential to recognize that its effectiveness depends on the underlying message strategy. Despite the centrality of both components in advertising effectiveness, relatively few studies have examined their interaction and its impact on persuasion [6,11]. These insights highlight a critical gap in advertising research: while creative appeal captures attention and elicits emotional response, its persuasive power is contingent upon the underlying message strategy [6]. Therefore, this study investigates the interactive effects of message strategy and creative appeal, providing a deeper understanding of their combined impact on consumer attitudes and behavior.

This study contributes to advertising theory and practice by connecting cognitive–affective mechanisms with strategic message framing in digital persuasion. Drawing on the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) [15], Cognitive Response Theory [16], and the Dual Mediation Hypothesis (DMH) [17], it examines how creative appeal and message strategy jointly shape consumer responses in social media advertising. Whereas prior research has typically investigated these elements in isolation, the present study demonstrates how their interaction shapes both attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. By integrating these perspectives, this research advances theoretical understanding of persuasion in digital environments and offers actionable guidance for advertisers seeking to align message framing and creative execution to optimize effectiveness.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Advertising Creative Appeal

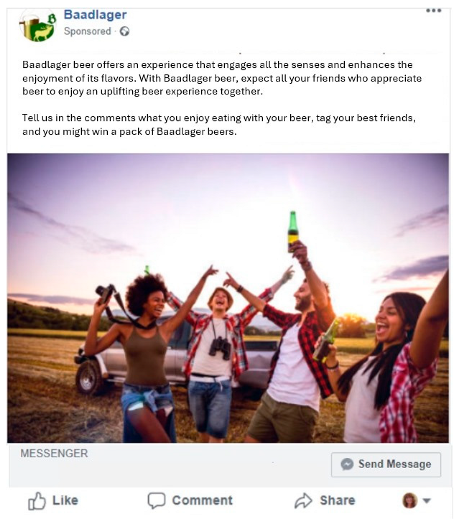

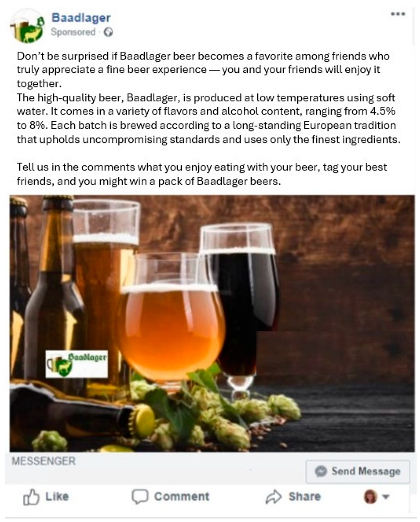

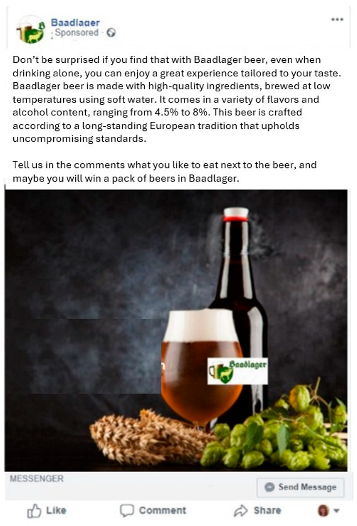

Creative appeal refers to the executional factors of the ad, i.e., the creative way that the advertising message is delivered, which draws attention to the advertisement. This is done by using elements such as graphic design, imagery, text, and sound [18]. Traditionally, these appeals are classified into two categories: informational appeal, which is adjusted to fact-based thinking, and transformational appeal, which is adjusted to value-based thinking [4,19]. Accordingly, informational appeal will include details showing a product’s quality, price, ingredients, and performance [20], while transformational appeal appeals to the associative system, minimizes the information about the product, and uses the ad text and visuals to create either aesthetic, hedonic, or sensational pleasure [6]. For example, an ad using informational creative appeal might feature a close-up image of a chilled beer bottle with condensation droplets, placed on a wooden table alongside a full glass showing the beer’s golden color and foamy head. The text would provide factual details such as the brewing process, range of flavors, alcohol content, and use of high-quality ingredients. The overall composition emphasizes clarity, precision, and product quality. Conversely, a transformational creative appeal in an ad might depict a lively evening scene with friends gathered around an outdoor table, clinking glasses of beer under warm, festive lighting, or a single person relaxing on a cozy couch with soft, ambient light, holding a glass of beer while enjoying a quiet moment. The accompanying text would be minimal, focusing on evoking the desired emotional response by emphasizing moments of joy, relaxation, or togetherness, thereby reinforcing the sensory and experiential aspects presented in the visuals.

2.2. Creative Appeal and Purchase Intention

Advertising creative appeal exerts its influence on consumer behavior through complex psychological processes. Two influential frameworks that explain these processes are the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM; [15]) and Cognitive Response Theory [16]. The ELM posits two main persuasion routes: the central route, which involves careful and thoughtful consideration of the ad content, and the peripheral route, which relies on cues such as emotional tone, imagery, music, aesthetics, and heuristics. In the central route, consumers engage in deliberate and systematic evaluation of the arguments and factual information presented in the ad. This route is typically activated when both motivation and the ability to process the information are high, and it often results in more enduring attitude formation and direct behavioral change. Informational appeals, by providing concrete and utilitarian information, are therefore more likely to stimulate central-route processing and the formation of stronger, more stable attitudes, which may, under certain conditions, translate into immediate purchase decisions [15,21]. In contrast, transformational (emotional) appeals often operate via the peripheral route, shaping positive effects and brand associations through emotional engagement, eliciting affective and heuristic responses that may generate quick, low-effort impressions but do not consistently translate into strong or immediate purchase intention [15,21].

Cognitive Response Theory [16] complements these insights by emphasizing that persuasion depends on the thoughts generated during message processing. Informational appeals tend to elicit supportive cognitive responses, such as agreement with product claims, which increase the likelihood of purchase. Transformational appeals, while effective in generating affective and experiential responses that deepen brand connections, may have a weaker direct influence on purchase intention because the affective impressions they generate are less diagnostic for utilitarian decision making. Observations from practice also suggest that marketers often favor rational over emotional appeals in digital campaigns, reflecting a belief in their greater effectiveness for generating measurable consumer actions, even in contexts where emotional messaging is theoretically recommended [9].

Empirical evidence reinforces these theoretical distinctions by showing consistent advantages for rational, information-rich content in driving immediate behavioral outcomes. Content high in informativeness and creative execution not only attracts attention but also fosters engagement that translates into purchase intention, whereas purely emotional cues often generate weaker or less consistent effects in high-involvement settings [3,22]. Moreover, rational and emotional appeals activate fundamentally different psychological mechanisms. Informational content elicits cognitive, utility-oriented evaluations that support stronger and more stable attitudes, whereas emotional content strengthens affective associations that contribute more to long-term brand meaning [4,23].

Taken together, prior theory and empirical evidence provide a strong rationale for expecting informational appeals to have an immediate advantage in driving purchase intentions. Informational appeals stimulate systematic, central-route processing that generates supportive cognitive responses [15,16], leading to more thoughtful evaluations and increased purchase intentions in digital environments, where perceived utility and clarity are key drivers of action [3,9,20]. In contrast, transformational appeals typically rely on peripheral cues and affective associations, which contribute more to enduring attitudes than to immediate behavioral responses. Hence, despite the potential influence of interacting factors, the theoretical and empirical foundations justify the expectation that informational appeals will outperform transformational appeals in generating purchase intention. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1.

Informational creative appeal is more likely to positively influence purchase intention compared to transformational appeal.

2.3. Dual Mediation Hypothesis

While the previous discussion emphasized the potential direct effect of informational versus transformational appeals on purchase intention, substantial evidence suggests that these appeals may also influence behavior indirectly, operating through a hierarchical attitudinal process. The Dual Mediation Hypothesis (DMH) [17] offers a well-established framework for understanding this process. It posits that advertising influences purchase intention primarily by shaping the attitude toward the ad (Aad), which then affects the attitude toward the brand (Ab), ultimately determining behavioral intentions. In this model, Aad functions as a pivotal mediator, channeling both cognitive and affective reactions toward brand attitudes and subsequent purchase behavior.

Beyond their direct influence on purchase intention (as established in H1), informational appeals can also operate through this indirect, hierarchical pathway. When rational messages are executed in ways that not only convey factual, utilitarian benefits but also generate a positive effect toward the ad, they can enhance the ad’s appeal (Aad), which then strengthens Ab and increases the likelihood of purchase. This indirect route is particularly evident in contexts where consumers are not fully engaged in central processing, or where the emotional resonance of the execution complements its cognitive content [15,17]. Thus, informational appeals can leverage both cognitive and affective responses, although they rely less exclusively on the hierarchical Aad-Ab pathway than transformational appeals.

By contrast, transformational appeals, which aim to evoke emotional resonance, experiential associations, and psychological connections, tend to depend far more heavily on the peripheral route. Their effect on purchase intention is predominantly indirect, operating through the enhancement of Aad, which then transfers to Ab. This pattern is consistently supported in the literature: emotional appeals foster enjoyment, affective engagement, and a favorable psychological response to the ad, which subsequently shapes brand attitudes [15,16,17]. In digital and social media environments, emotionally rich creative executions have been found to elevate Aad and subsequently Ab, even when they do little to alter cognitive brand beliefs [18,24].

Taken together, these insights suggest that while informational appeals can influence purchase intentions through both direct and indirect routes, transformational appeals are more dependent on the hierarchical process, in which the attitude toward the ad influences the attitude toward the brand, which in turn drives purchase intention, as described by the DMH. Recognizing these distinctions helps clarify not only whether an appeal will be effective, but also the psychological mechanisms through which it exerts its influence. Accordingly, our hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2.

The relationship between Creative Appeal (Informational/Transformational) and purchase intention will be mediated by attitudes (i.e., attitude toward the Ad and attitude toward the brand).

2.4. Message Strategy Approach as a Moderator

Advertising effectiveness is shaped not only by the ad’s creative appeal but also by how the message is framed, namely, message strategy. In practice, message strategy functions as a blueprint that connects the product’s benefit to the consumer motives (comfort, safety, esteem), guiding what the ad asks people to focus on and why it matters [10].

In social media advertising, recent work proposed a new message strategy framework from a social media perspective, distinguishing personal message strategy (self-focused “for me”) from social experience message (collective enjoyment, interaction, “for us”) [25]. This strategic perspective was further found to interact with creative appeals (informational vs. transformational) in driving consumer engagement with the ad [6,7].

Construal Level Theory (CLT) provides a theoretical foundation for articulating the relationship between individual/social message strategies and the effects of creative appeal on consumer hierarchical behavior. Psychological distance encompasses how individuals perceive different aspects of events or tasks, including when they take place (temporal distance), where they occur (spatial distance), who is involved (social distance), and the likelihood of their occurrence (hypotheticality) [24]. When psychological distance is low, individuals engage in concrete, feasibility-focused thinking; when distance is high, they adopt abstract, desirability-focused construals.

In advertising and consumer behavior, CLT has been repeatedly applied to show that message strategy can serve as a psychological distance cue (e.g., [26,27]). Personal benefit is perceived as having a low social psychological distance, while social benefit is seen as having a high social psychological distance [28]. Furthermore, research suggests that a lower social psychological distance can have a more positive impact on consumer behavior than a higher psychological distance [29,30]. From this perspective, we suggest that personal message strategies emphasizing self-relevance (“for me”) reduce psychological distance and promote concrete processing, aligning with informational appeals. In contrast, the social-experience strategy, which focuses on collective enjoyment (“for us”), increases psychological distance and encourages abstract thinking, a trait compatible with transformational appeals.

In digital advertising contexts, the applicability of CLT extends beyond its traditional formulation and must be considered in light of the unique affordances of social media. Recent CLT-based research in digital contexts suggests that message-level cues embedded in online advertising content can be interpreted through the lens of psychological distance. For example, Yang [29] shows that social commerce platforms with strong-tie interactions reduce social distance and increase purchase intentions, while Yang and Hu [30] find that temporal distance influences consumer preferences for concrete versus abstract advertising messages. Similarly, Septianto et al. [31] highlight how affective states such as awe activate higher-level construals that enhance persuasion in digital contexts, and Yu et al. [26] demonstrate that concrete versus abstract information framing in online advertising systematically shifts consumer responses. Taken together, this stream of research positions CLT as a useful theoretical framework for interpreting how message strategies (personal vs. social) may interact with creative appeals (informational vs. transformational) in digital advertising contexts, particularly at the level of message framing and consumer interpretation.

Consequently, the message strategy (personal versus social) influences how the type of creative appeal (informational versus transformational) affects consumer responses. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a.

Message strategy approach (personal/social experience) will moderate the direct relationship between creative appeal and purchase intention, such that a personal message strategy will have a stronger positive effect on purchase intention.

Hypothesis 3b.

The message strategy approach (personal/social experience) will moderate the indirect relationship between creative appeal and purchase intention through attitudes, such that a personal message strategy will have a positive effect on attitudes toward the ad.

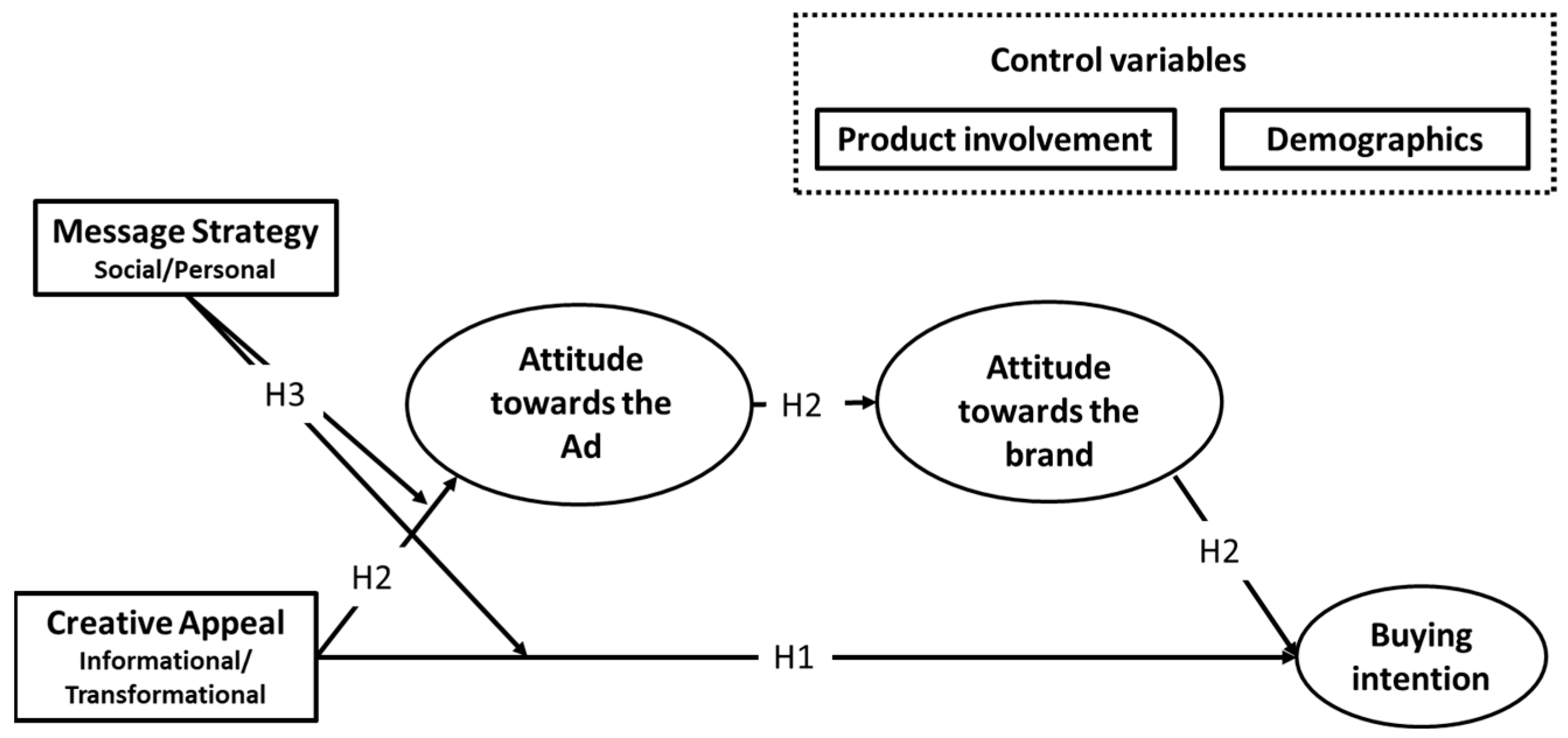

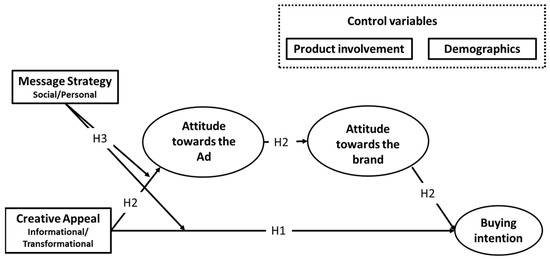

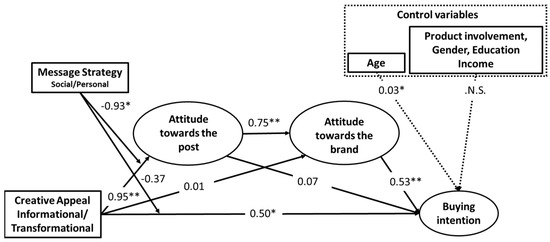

In summary, in the conceptual framework, the ELM [15,21] clarifies the dual processing routes underlying responses to informational versus transformational appeals. The DMH [17] explains the mediating role of Aad and Ab in linking ad exposure to purchase intention, and CLT [24] captures the moderating function of message strategy through psychological distance. Together, these theories complement one another and jointly frame the mechanisms examined in our study. Figure 1 displays the conceptual framework and hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Suggested conceptual framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Design and Procedure

An experimental factorial design with two conditions (creative appeal: informational vs. transformational) and two further conditions (message strategy: social-experience vs. personal) was employed to conform to the research framework. The Facebook advertising post formats were utilized for the experiments (see Appendix A). A pilot study was conducted to identify and select a product that offers both perceived social experience and personal benefits. In this pilot, participants were exposed to eight different generic products (TV, laptop, perfume, frozen pizza, beer, ice cream, glasses, and toothpaste) one at a time. For each product, participants were first asked a yes-or-no question regarding their experience with buying the product. Answering “yes” led them to a series of questions about their latest product purchase. Next, they were asked to rate their agreement with statements on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 7 (definitely agree). The statements were: one item for the social-experience attribute (i.e., “When I consider buying the product, it is mainly important to me to enjoy the product in a social-experience with my friends or family”), and one item for the personal attribute (i.e., “When I consider buying the product, my personal enjoyment or benefit from the product is most important to me”). Following this procedure, the product beer met the conditions (In the social-experience attribute, M = 5.62, SD = 1.71, t = 6.32, p < 0.01 and in the personal attribute, M = 5.59, SD = 1.54, t = 5.78, p < 0.01; n = 37, 4 midpoints of the scale) and was chosen for the study. Additionally, the ad featured a product belonging to a fictitious brand name, “Baadlager”. Unfamiliarity with the brand was confirmed in the main experiment (M = 2.18, SD = 1.69, t = −16.33, p < 0.01; 4 midpoints of the scale).

Creative appeal conditions (Informational/Transformational) were manipulated using a script consisting of a message paragraph with relevant claims concerning the product. Additionally, in the informational condition, the product was the center of the picture, whereas in the transformational condition, the image displayed enjoyment projected during group or private consumption. Message strategy conditions (social-experience/personal) were manipulated in both text and visual forms, using a visual representation of the product with a group of presenters/one presenter (see Appendix A). The message was designed to capture both group/personal benefits.

In the main experiment, participants were randomly assigned to one of the four treatments. They were asked to carefully examine a Facebook-sponsored post, follow the instructions, and answer a survey about their possible reaction to the ad. To avoid demand effect bias, participants were told that their opinions were required for evaluating new content on Facebook. Anonymity and data confidentiality were assured.

3.2. Sample

Facebook users were randomly recruited through the online-panel survey company Blueberries, and data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire. Facebook was selected as the advertising context because it remains the leading social media platform in terms of global reach and cross-demographic adoption [32,33], making it an ecologically valid setting for examining consumer responses to sponsored posts. Consent for participation was obtained from all participants, and the questionnaires were coded to ensure the anonymity of the data analysis. A total of 231 usable responses were analyzed, including fully balanced cell sizes across the four conditions: 57 respondents were exposed to the social-experience informational condition, 58 to the social-experience transformational condition, 58 to the personal–informational condition, and 58 to the personal transformational condition. A power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 [34] indicated that to achieve an 80% chance of detecting a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) in a linear regression analysis (F-test), a minimum sample size of 118 participants is necessary when including ten predictors (which account for three independent variables, two for interaction effects and five control variables) at a significance level of p = 0.05 and two-tailed test. Consequently, the sample size used in this study is considered appropriate.

Participants were all Facebook users with an average of 649 friends. Their age ranged from 24 to 52 (mean age 35.5). Forty-nine percent were female and 51% male. Most participants have a high school education or higher (79%), with 35% having a below-average income, 32% an average income, and 33% an above-average income.

3.3. Variable Measurement

The survey instrument consisted of various items drawn from prior studies, based on reliable and validated scales. Three items measuring the scale of purchase intention were derived from Okazaki et al. [35]. Four items related to attitude toward the brand and four items related to attitude toward the Ad were taken from Choi and Rifon [36]. Brand familiarity was added (one item: “How well do you know the beer brand Baadlager?”). In these measures, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with different statements (a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 7). Lastly, actual product involvement was measured (one item: “Do you drink or buy beer?”, with three options—does not drink and does not buy/does not drink but buys/drink and buy). Demographic data were also collected.

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with Varimax rotation was conducted. In this process, three factors were identified, accounting for 83.49% of the cumulative variance. All items demonstrated high internal validity (acceptable loading, all above 0.5; Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, [37]). Loadings for purchase intention were 0.88–0.91; for attitude toward the brand, 0.75–0.82; and attitude toward the ad, 0.69–0.81.

Next, all items related to the variables were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess construct validity and reliability. The results confirm the construct and show acceptable fit for all measurements (χ2 value (37) = 88.99, p < 0.05 (χ2/df < 3); comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.979; normed fit index (NFI) = 0.966; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.078). The standardized regression estimates for the three constructs were above 0.50, reflecting an acceptable fit of the measures. Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha (Purchase intention: 0.82, 0.93, 0.93; Attitude towards the brand: 0.83, 0.95, 0.95; Attitude towards the ad: 0.71, 0.91, 0.89, respectively) indicated acceptable levels of convergent validity and internal consistency of the measurements. Comparing the squared correlation estimates (Maximum Shared Squared Variance, MSV) between each pair of constructs with AVE values revealed greater values for AVE in all cases, further confirming construct discriminant validity (correlation patterns and MSV are provided in Appendix B). Means were then calculated and examined for each factor.

4.2. Manipulation Check

The experimental conditions were validated during the main experiment. Participants of the four ad conditions rated the extent to which they agree with four statements concerning the ads (“the post expresses social-experience/personal experience” and “the post mostly appeals to my logic/to my feelings”), on a seven-point Likert scale, from 1 (definitely not agree) to 7 (definitely agree).

Paired samples t-tests were conducted to validate these experimental conditions. As expected, in creative appeal conditions participants rated the informational ads as more rational than emotional ads (M = 5.16, SD = 1.28, M = 3.47, SD = 1.73, respectively; t = 8.43, p < 0.01; Cohen’s d = −1.11, CI: −1.39 to −0.83) and rated the transformational Ads as more emotional than rational ads (M = 5.47, SD = 1.28, M = 4.56, SD = 1.78, respectively; t = 4.49, p < 0.01; Cohen’s d = 0.59, CI: 0.33 to 0.85). In the message strategy conditions participants rated the social ads as more social-experience than personal experience ads (M = 5.47, SD = 1.26, M = 3.58, SD = 1.73, respectively; t = 9.50, p < 0.01; Cohen’s d = −1.25, CI: −1.53 to −0.97) and rated the personal ads as more personal experience than social-experience ads (M = 5.42, SD = 1.43, M = 4.48, SD = 1.45, respectively; t = 4.98, p < 0.01; Cohen’s d = 0.66, CI: 0.39 to 0.92).

4.3. Model Testing

First, we examined the main effect of creative appeal on purchase intention. Because Levene’s test indicated unequal variances between conditions (F = 5.96, p = 0.02), we report Welch’s t-test rather than the standard t-test. Participants exposed to the informational appeal reported significantly higher purchase intention (MInformational = 4.71, SDInformational = 1.28) than those exposed to the transformational appeal (MTransformational = 4.17, SDTransformational = 1.58), Welch’s t(220.41) = −2.88, p < 0.01 (Cohen’s d = −0.38, CI: −0.64 to −0.12). A univariate ANOVA with demographic covariates also yielded a significant effect (F = 7.58, p < 0.01); this analysis is reported for completeness, whereas Welch’s test provides the primary estimate of the effect. Given the balanced cell sizes and the large sample, ANOVA and ANCOVA are considered robust to moderate violations of this assumption. More critically, the assumption of homogeneity of regression slopes was tested by including interaction terms between Creative Appeal and each covariate (i.e., age, education, income, and gender). All interactions were non-significant (all p-values > 0.40), indicating that the relationship between the covariates and purchase intention was comparable across groups. This confirms that the key ANCOVA assumption was met, supporting the validity of the adjusted model. Altogether, these results correspond with our hypothesis. Hence, H1 is supported.

Next, we tested the complete model using Hayes’ [38] PROCESS macro (model 86) with 5000 bootstrapped samples. In this model, intention to buy was the dependent variable, and creative appeal was the independent variable. Attitude toward the ad and attitude toward the brand were mediators, while message strategy served as the moderator. Actual product involvement and demographic variables were included as covariates to rule out potential confounding effects.

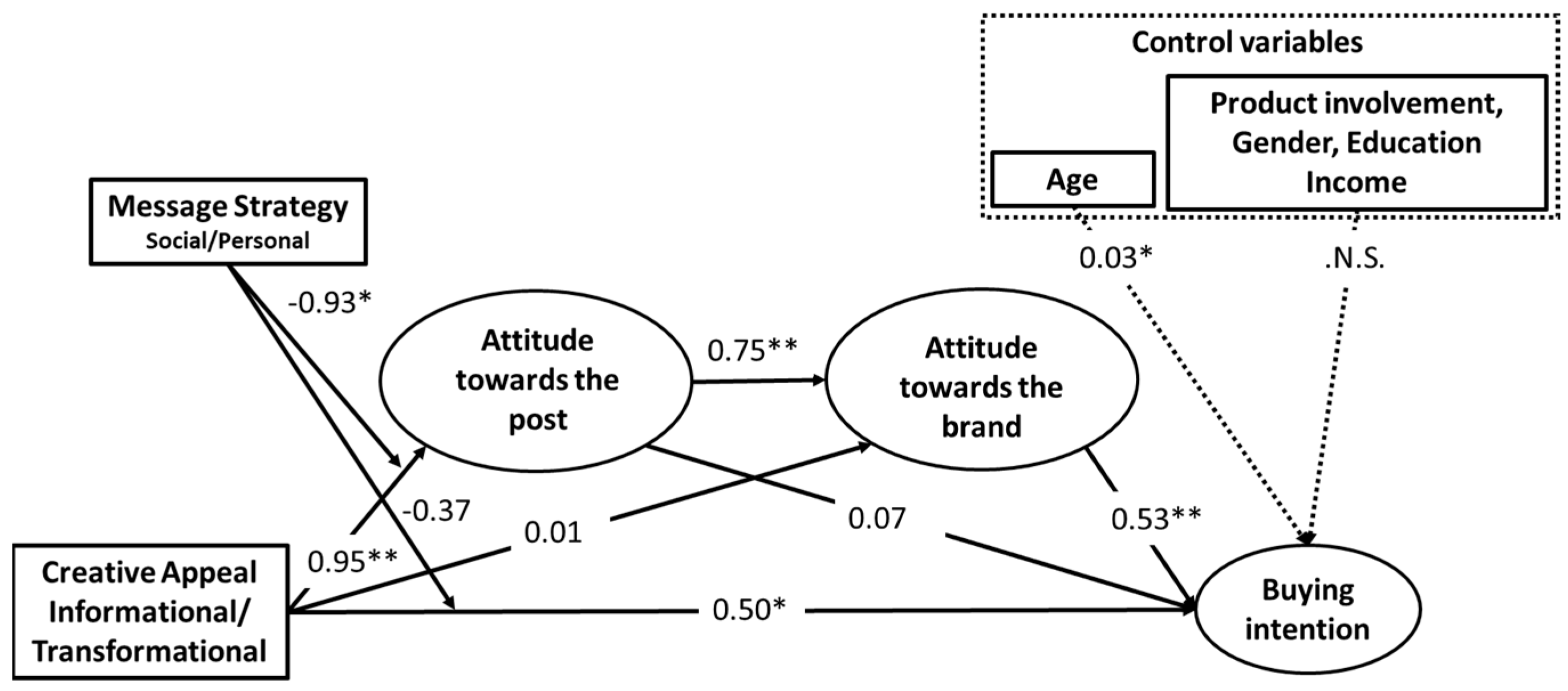

The analysis revealed three significant sequential paths (see Table 1 and Figure 2). Informational creative appeal has a positive relationship with attitude toward the ad (B = 0.95; SE = 0.26; t = 3.66; p < 0.01). Attitude toward the ad was strongly associated with attitude toward the brand (B = 0.75; SE = 0.04; t = 19.88; p < 0.01). Attitude toward the brand was positively associated with intention to buy (B = 0.53; SE = 0.11; t = 4.76; p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Regression Model Coefficients Predicting AAd, Ab, and Purchase Intention.

Figure 2.

Path analysis results. Path parameters are unstandardized parameter estimates. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

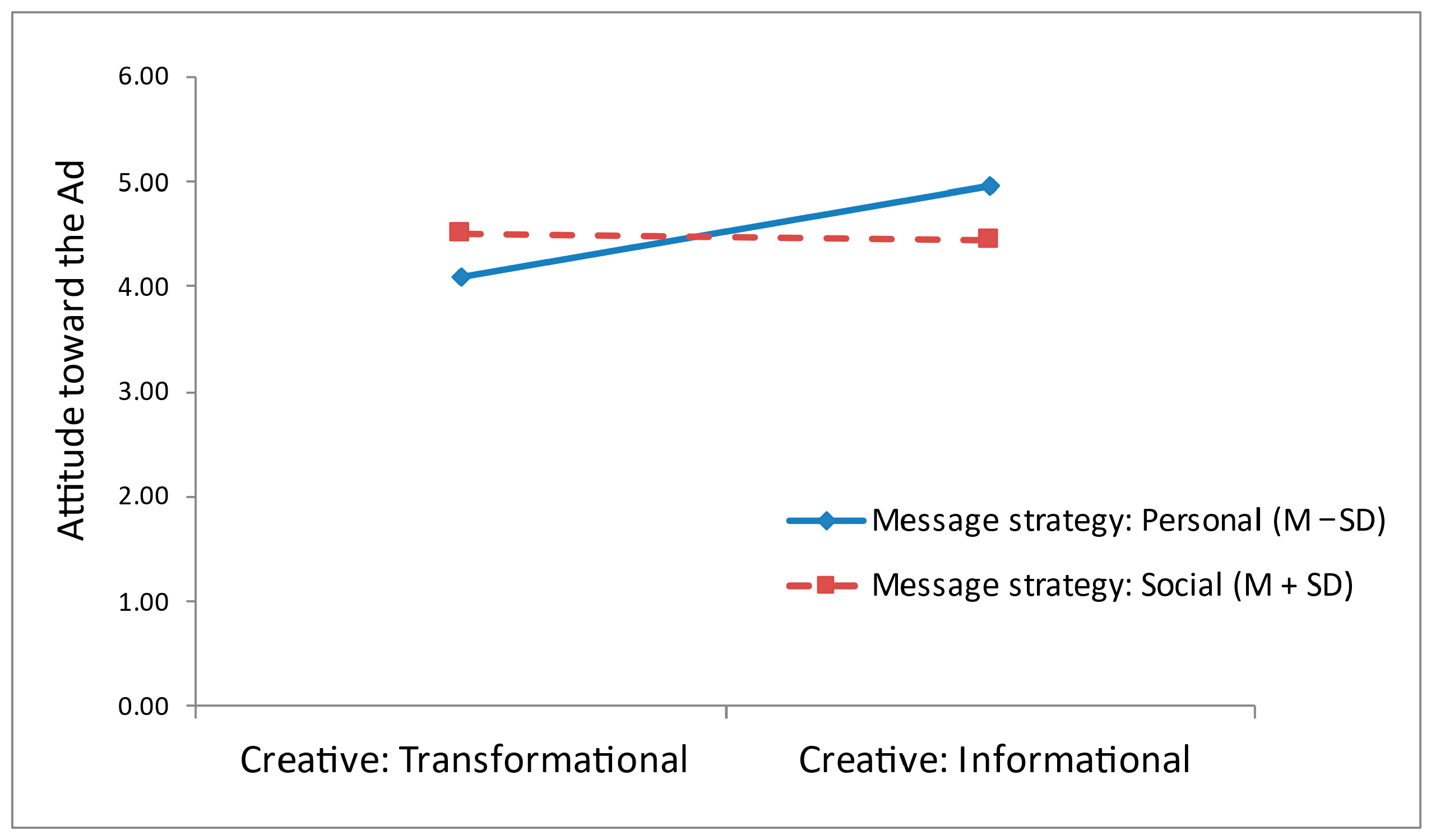

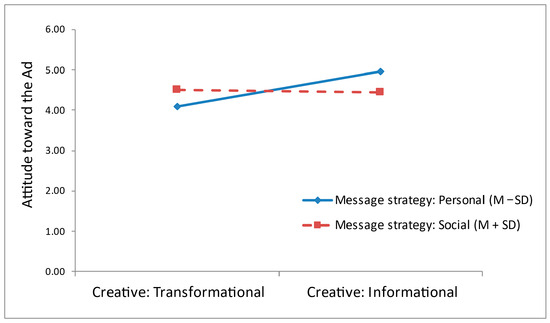

Additionally, the interaction effect of message strategy (i.e., social) and creative appeal (i.e., informational) on attitude toward the Ad was negative and significant (B = −0.93; SE = 0.37; t = −2.52; p < 0.05). Namely, when the message strategy was personal, the positive effect of informational creative appeal on attitude toward the Ad is higher (see Figure 3). Under the personal message strategy, the positive effect is significant (B = 0.95; SE = 0.26; t = 3.66; p < 0.01), though under the social message strategy, the effect is insignificant (B = 0.02; SE = 0.26; t = 0.08; p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of message strategy on the relationship between creative appeal and attitude toward the Ad.

Furthermore, the results support the moderated mediation model (B = −0.37; 95% CI: −0.80 to −0.07). The indirect mediated effect of creative appeal is moderated by message strategy. Nevertheless, the moderation mediation effect of message strategies on the relationships between creative appeal and intention to buy was significant under the personal message strategy (B = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.68) and not under the social message strategy (B = 0.01; 95% CI: −0.24 to 0.22).

To provide greater clarity regarding the moderated mediation structure, we elaborate on the conditional indirect effects. Under the personal message strategy, the indirect effect of creative appeal on intention to buy through Aad and Ab was significant, indicating that the attitudinal pathway operates when the message emphasizes self-relevance. In contrast, under the social-experience strategy, the indirect effect was not significant, suggesting that social framing creates a less self-relevant perspective that weakens the sequential Aad and Ab mechanism. These patterns demonstrate that the persuasive process primarily functions under personal framing, consistent with theoretical accounts that link message relevance to deeper attitudinal processing.

Creative appeal (i.e., informational) also shows a positive direct relationship with intention to buy (B = 0.50; SE = 0.24; t = 2.09; p < 0.05); however, the interaction effect of message strategy (i.e., social) and creative appeal (i.e., informational) on intention to buy was insignificant (B = −0.37; SE = 0.34; t = −1.10; p > 0.05). Thus, H1, H2 and H3b are supported, while H3a is not supported.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion of the Findings

The present study aims to investigate how creative appeals (informational vs. transformational) and message strategies (personal vs. social-experience) interact to influence consumer responses in the context of social media advertising. Drawing upon the Elaboration Likelihood Model [15], Cognitive Response Theory [16], and the Dual Mediation Hypothesis [17], this study provides new insights into both the direct and indirect effects of advertising strategies on attitudes and purchase intentions.

First, the findings confirm that informational creative appeals are more effective in generating immediate purchase intentions than transformational appeals. This result aligns with prior evidence indicating that rational, fact-based content stimulates central-route processing, generates supportive cognitive responses, and leads to direct behavioral outcomes [17,21]. In contrast, transformational appeals, which are theorized to build brand meaning via affect-laden evaluations, showed weaker direct effects on purchase intention, consistent with the notion that consumers rely more heavily on peripheral processing and affective engagement. However, while rational appeals drive short-term persuasion, emotional and symbolic elements embedded in transformational appeals should not be dismissed. Previous research [5] has shown that emotional content strengthens the associative and affective bonds that underlie brand–customer relationships, even when it does not directly lead to immediate purchasing behavior. In this regard, informational and emotional dimensions work in parallel rather than in opposition, forming complementary layers of persuasion.

Second, the study further revealed that attitudes toward the Ad and the brand mediated the effect of creative appeal on purchase intentions. While informational appeals had both direct and mediated effects, transformational appeals were mainly processed by consumers through the hierarchical pathway (Aad then Ab). These findings resonate with the Dual Mediation Hypothesis [17], reinforcing the notion that Aad plays a pivotal role in shaping brand attitudes and subsequent behavioral intentions. Yet, consistent with more recent interpretations of the DMH in digital settings, affective resonance can itself serve as a form of cognitive elaboration, an “emotional reasoning” process through which consumers justify intuitive preferences after exposure to emotionally engaging content [5,8]. This interpretation underscores that emotional responses are not peripheral “noise” but integral to the meaning-making process that sustains persuasion. The results, therefore, confirm a central distinction in the literature: transformational appeals depend primarily on attitudinal mediation, while informational appeals can influence consumer behavior via multiple mechanisms.

Third, the findings also demonstrate the role of message strategy as a moderator. Informational appeals proved more persuasive when combined with personal (self-relevant) message strategies, whereas this effect disappeared when paired with social-experience strategies. This pattern aligns closely with theoretical expectations derived from Construal Level Theory [24], according to which reduced psychological distance facilitates concrete, self-relevant processing. Although the present study did not directly measure psychological distance as a construct, the observed interaction patterns are interpreted through the lens of Construal Level Theory, drawing on prior research linking message framing to distance-related construal processes. At the same time, social-experience framing is theoretically associated with higher psychological distance, which CLT proposes may elicit more abstract thinking and collective imagery. Such processes could help explain why this framing aligns more readily with the affective pathways that transformational appeals typically rely on [30].

Interestingly, our data also reveals that this interaction manifests more strongly in evaluative outcomes (Aad, Ab) than in behavioral intention, suggesting that emotional framing may first consolidate attitude before translating into action. This aligns with evidence from emotional advertising research, which shows that feelings of empathy, belonging, and self-affirmation often precede the rational justification of a purchase decision [3,5]. Thus, while our experiment focused on short-term behavioral outcomes, the observed attitudinal shifts may represent the first stage of longer persuasion trajectories that unfold across repeated exposures in social media environments.

It should be noted that although the study employed a 2 × 2 experimental design, the present analysis deliberately focuses on the hypothesized direct, mediated, and moderated mediation pathways rather than on descriptive post-hoc comparisons between the four experimental cells. Exploratory inspection of the cell means was conducted for descriptive purposes; however, because the revised manuscript does not advance claims regarding the relative superiority of any specific appeal-strategy combination, these cell-level comparisons were intentionally omitted to maintain a theory-driven analytic focus.

Fourth, we observe that differences between personal and social framing were more pronounced for ad and brand attitudes than for purchase intention. One possible interpretation is that such framing may function in ways that resemble psychological-distance cues, potentially shifting construal tendencies and processing depth [27,31]. Advertising manipulations typically show stronger effects on ad/brand attitudes than on purchase intention [8], and abstract–concrete framing often influences intention via advertising attitudes rather than directly [26]. In our experiment, the advertising stimuli did not incorporate any transactional or feasibility cues, such as price, purchasing channel, or timing. As a result, intention judgments likely relied on unmanipulated personal considerations of feasibility, like time availability (e.g., “Do I have time to pick this up today?”) or perceived effort to shop (e.g., “Do they ship to my location?”). These factors are known to moderate immediate purchase intentions, even when attitudes towards the product improve [30,31]. Future studies could extend this framework by adding behavioral cues or real-time interaction features (e.g., “Shop Now” prompts, click-through options) to examine whether these moderations remain stable once immediacy and interactivity are introduced.

Lastly, the regression analyses indicated that certain demographic factors, specifically gender and age, showed significant associations with consumer responses. Female respondents tended to evaluate the ads more positively, and younger participants demonstrated higher purchase intentions. These results are consistent with prior research suggesting that younger consumers are more engaged with digital advertising content and that women may exhibit stronger affective responses in social media contexts [3,39,40,41]. Although these findings were not the primary focus of the present study, they suggest that demographic differences may shape how consumers respond to creative appeals and message strategies, and they warrant further investigation in future research. The gender effect is particularly relevant considering emotional-appeal research demonstrating that women tend to process affective cues more empathically, interpreting social narratives as personally relevant [5,40,42].

5.2. Theoretical Implications

Taken together, these findings make several theoretical contributions to the advertising and persuasion literature. They advance the understanding of persuasion as a multi-layered process where rational and emotional mechanisms co-occur rather than compete. The study extends prior research by confirming the short-term effectiveness of informational appeals in social media advertising, while integrating emotional and relational dynamics that have been largely overlooked in digital persuasion models. The study also empirically validates the mediating role of attitudes, in line with the DMH, and shows that message strategy shapes the attitudinal pathway in a pattern consistent with psychological theory, clarifying how creative appeal influences consumer responses within social media advertising. Integrating these frameworks advances theoretical understanding of how consumers process advertising in digital contexts and highlights the importance of strategic fit in determining advertising effectiveness. Beyond this, this study responds to recent CLT-based research by showing that patterns in consumer responses align with theoretical expectations regarding social distance cues. Because the study focused on message-driven cues rather than environmental features of the platform, the contribution lies in illustrating how distance-related interpretations can emerge from the structure of the advertising message itself within a social media setting. This positions CLT as a useful interpretive lens for understanding how consumers evaluate creative executions in sponsored posts without extending conclusions beyond the scope of the experimental design.

5.3. Practical Implications

In addition to its theoretical contributions, the findings offer several practical insights for advertisers and marketing practitioners operating in social media environments. From a managerial perspective, this study examines how consumers engage with advertising messages on social media. When people encounter an ad that speaks directly to them, highlighting concrete product benefits in a personal frame, they are more likely to pause, process the information, and feel convinced enough to act. In this sense, informational appeals paired with personal strategies work like a “shortcut to action”, giving consumers both relevance (“for me”) and feasibility (“this is useful right now”).

Conversely, when the same informational content is framed socially (“for us”), its persuasive immediacy declines, but the emotional and communal associations it evokes may nurture long-term brand equity. Advertisers can thus view creative appeal and message strategy not as isolated tactics but as co-dependent levers for activating either immediate conversion or gradual relationship building.

In practice, this means that advertisers should conceptualize creative appeal and message strategy not as isolated elements, but as interdependent strategic decisions. Informational appeal, paired with personal framing, produces fast-moving outcomes, such as a direct nudge toward purchase. Understanding these dynamics enables practitioners to determine whether to focus on short-term conversion or plant seeds for long-term brand growth, and to align their creative and strategic choices accordingly.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Beyond its immediate contributions, this study has several limitations that open opportunities for future research. First, the study relied on a single experiment within a single product category (beer), which limits the robustness and generalizability of the findings. Future work could therefore expand the framework by examining additional product categories with varying levels of consumer involvement, as responses may differ across utilitarian versus hedonic goods. Second, the study was conducted on a single platform (Facebook). Comparative studies across platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok, or emerging formats, could also shed light on platform-specific dynamics in consumer responses. Importantly, because the present study was conducted solely within a Facebook context, it does not provide direct empirical evidence regarding how differences between social media platforms or specific platform functionalities dynamically shape psychological distance cues. Accordingly, references to platform-related CLT mechanisms in the discussion are grounded in prior literature rather than in platform-level comparative data from the current study. Third, the research was conducted in a single cultural context, which limits the extent to which the findings can be generalized globally. Cross-cultural investigations would provide valuable insights into whether the observed fit effects between creative appeal and message strategy are consistent across cultural contexts with differing advertising norms and consumer expectations, and social media practices. Fourth, the study examined the interaction of creative appeal with message strategy as the focal mechanism of interest. While this framework is central to our theoretical model, creative appeals may also interact with additional factors such as consumer traits, platform affordances, or cultural settings. Future research could build on this work by examining such interactions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how creative appeals operate across diverse digital environments. Fifth, although the sample size was adequate for detecting the main effects of the magnitude observed, it may not be sufficient for capturing smaller interaction effects. Sixth, the operationalization of psychological distance. Following prior CLT research, we classified personal strategies as low-distance and social strategies as high-distance. While theoretically grounded, this simplification overlooks cases where social experiences may also feel concrete and proximal. Future research should refine this distinction. Seventh, in the present study, we controlled five potential confounds: actual product involvement, gender, age, income, and education. In contrast, future research can incorporate additional controls (e.g., social media usage intensity and perceived ad design quality). Finally, another limitation relates to the use of an online panel. While this approach provided access to a diverse group of social media users and an adequate sample size for hypothesis testing, it may also introduce potential biases, such as the over-representation of heavy users. As a result, the findings should be interpreted with some caution regarding their representativeness, and future studies may benefit from employing probability-based samples or triangulating results with alternative data sources. Addressing these limitations in future research will strengthen the external validity of the framework and provide more comprehensive guidance for advertisers.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the effectiveness of creative appeals in social media advertising cannot be understood in isolation but must be considered in relation to the message strategy with which they are paired. Informational appeals, combined with a personal message strategy, are particularly effective in driving immediate purchase intentions. In contrast, transformational appeals, combined with social framing, appear to operate mainly at the attitudinal level, shaping evaluations of the ad and the brand rather than immediate behavioral intentions. These insights underscore the importance of strategically aligning message strategy and creative execution to maximize advertising outcomes in digital environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.K., D.Z.-S. and S.L.; methodology, O.K., D.Z.-S. and S.L.; software, S.L.; validation, O.K., D.Z.-S. and S.L.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, O.K. and D.Z.-S.; resources, O.K. and D.Z.-S.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, O.K. and D.Z.-S.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; visualization, O.K. and S.L.; supervision, O.K., D.Z.-S. and S.L.; project administration, O.K. and D.Z.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ariel University (protocol code AU-SOC-DZS-20191216; approval date: 16 December 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ELM | Elaboration Likelihood Model |

| DMH | Dual Mediation Hypothesis |

| CLT | Construal Level Theory |

| Aad | Attitude toward the ad |

| Ab | Attitude toward the brand |

Appendix A

Table A1.

The Facebook advertising Ad formats (Translated to English).

Table A1.

The Facebook advertising Ad formats (Translated to English).

| Transformational Creative Appeal | Informational Creative Appeal | |

|---|---|---|

| Social-experience Message Strategy |  |  |

| Personal Message Strategy |  |  |

Appendix B

Table A2 presents descriptive statistics and correlations for all study variables, including MSV and AVE values used to assess discriminant validity.

Table A2.

Variables’ Correlations, Descriptive Statistics, and Maximum Shared Squared Variance (MSV) a.

Table A2.

Variables’ Correlations, Descriptive Statistics, and Maximum Shared Squared Variance (MSV) a.

| Variable | Mean | Std.D | Min | Max | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intention to buy | 4.44 | 1.47 | 1 | 7 | 0.82 | 0.55 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.13 * | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.02 | −0.06 |

| 2. Attitude toward the brand | 4.65 | 1.27 | 1 | 7 | 0.30 | 0.83 | 0.82 ** | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.03 |

| 3. Attitude toward the ad | 4.62 | 1.37 | 1 | 7 | 0.24 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.18 ** | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| 4. Creative appeal | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | -- | −0.00 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.11 | −0.03 |

| 5. Message strategy | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -- | −0.01 | 0.26 ** | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| 6. Actual product involvement | 2.87 | 0.34 | 2 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -- | −0.33 ** | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.17 ** |

| 7. Gender | 1.48 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.11 | -- | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.02 |

| 8. Age | 35.54 | 6.44 | 24 | 52 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -- | 0.19 ** | 0.11 |

| 9. Income | 2.92 | 1.23 | 1 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | -- | 0.24 ** |

| 10. Education | 3.48 | 1.18 | 1 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | -- |

Notes: n = 231; * < 0.05, ** < 0.01; a Correlations are in the upper right side, while the MSV are in the lower left side; AVE are in bold diagonal.

References

- Statista Social Media Advertising—Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/amo/advertising/social-media-advertising/worldwide (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- WARC Global Ad Trends: Social Media Reaches New Peaks. Available online: https://www.warc.com/content/paywall/article/warc-data/global-ad-trends-social-media-reaches-new-peaks/en-gb/155614?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Lee, J.; Hong, I.B. Predicting Positive User Responses to Social Media Advertising: The Roles of Emotional Appeal, Informativeness, and Creativity. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puto, C.P.; Wells, W.D. Informational and Transformational Advertising—The Differential-Effects of Time. Adv. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 638–643. [Google Scholar]

- Vrtana, D.; Krizanova, A. The Power of Emotional Advertising Appeals: Examining Their Influence on Consumer Purchasing Behavior and Brand–Customer Relationship. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimand Sheiner, D.; Kol, O.; Levy, S. Planning Facebook Message Strategy and Creative Appeal for Effective Ad Engagement—An Exploratory Study. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2024, 42, 1195–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Yao, Q.; Wu, X. How Does Self-Construal Influence Green Product Purchase in the Digital Era? The Moderating Role of Advertising Appeal. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, S.; Eisend, M.; Koslow, S.; Dahlen, M. A Meta-Analysis of When and How Advertising Creativity Works. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casais, B.; Pereira, A.C. The Prevalence of Emotional and Rational Tone in Social Advertising Appeals. RAUSP Manag. J. 2021, 56, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belch, G.E.; Belch, M.A. Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, 11th ed.; McGraw-Hill Publishing: Columbus, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Praet, C.L.C. Message Strategy Typologies: A Review, Integration, and Empirical Validation in China. In Advances in Advertising Research (Vol. VI); Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Cadet, F.T.; Aaltonen, P.G.; Kavota, V. The Advertisement Value of Transformational & Informational Appeal on Company Facebook Pages. Mark. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavidge, R.J.; Steiner, G.A. A Model for Predictive Measurements of Advertising Effectiveness. J. Mark. 1961, 25, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Chen, J.; Yang, X. The Impact of Advertising Creativity on the Hierarchy of Effects. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Message Elaboration versus Peripheral Cues. In Communication and Persuasion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A. Cognitive Learning, Cognitive Response to Persuasion, and Attitude Change. In Psychological Foundations of Attitudes; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Lutz, R.J.; Belch, G.E. The Role of Attitude Toward the Ad as a Mediator of Advertising Effectiveness: A Test of Competing Explanations. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.W.; Furse, D.H. Analysis of the Impact of Executional Factors on Advertising Performance. J. Advert. Res. 2000, 40, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, W.F.; Weigold, M.F. M: Advertising, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Albers-Miller, N.D.; Stafford Royne, M. An International Analysis of Emotional and Rational Appeals in Services vs Goods Advertising. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Petty, R.E.; Chuan, F.K.; Rodriguez, R. Central and Peripheral Routes to Persuasion. An Individual Difference Perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1032–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Kang, J.-H.; Byeon, H.-M.; Sung, Y.-T.; Song, Y.-A.; Lee, J.-W.; Yoo, S.-C. Exploring the Motivation for Media Consumption and Attitudes Toward Advertisement in Transition to Ad-Supported OTT Plans: Evidence from South Korea. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ray, M.L. Affective Responses Mediating Acceptance of Advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimand Sheiner, D.; Kol, O.; Levy, S. It Makes a Difference! Impact of Social and Personal Message Appeals on Engagement with Sponsored Posts. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sun, X.; Huang, Y.; Jia, Y. Concrete or Abstract? The Impact of Green Advertising Appeals and Information Framing on Consumer Responses. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.K.; Yoon, S.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y. Text versus Pictures in Advertising: Effects of Psychological Distance and Product Type. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucke, S.; Koenigstorfer, J. Construal-Level Perspective on Consumers’ Donation Preferences in Relation to the Environment and Health. Mark. ZFP J. Res. Manag. 2018, 1, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Consumers’ Purchase Intentions in Social Commerce: The Role of Social Psychological Distance, Perceived Value, and Perceived Cognitive Effort. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hu, J. Seize the Time! How Perceived Busyness Influences Tourists’ Preferences for Destination Advertising Messages. J. Travel Res. 2024, 63, 588–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septianto, F.; Seo, Y.; Li, L.P.; Shi, L. Awe in Advertising: The Mediating Role of an Abstract Mindset. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center Americans’ Social Media Use 2025. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2025/11/20/americans-social-media-use-2025/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Statista Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of February 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/?srsltid=AfmBOoqTd2l7y7fRYkkgghMfGlWcxLx8ym-Bkj0gby800pmk5wxr2dxf (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S.; Mueller, B.; Taylor, C.R. Measuring Soft-Sell versus Hard-Sell Advertising Appeals. J. Advert. 2010, 39, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. It Is a Match: The Impact of Congruence between Celebrity Image and Consumer Ideal Self on Endorsement Effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Upper Saddle River: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kol, O.; Levy, S. Men on a Mission, Women on a Journey—Gender Differences in Consumer Information Search Behavior via SNS: The Perceived Value Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezgin Ediş, L.; Kılıç, S.; Aydın, S. Message Appeals of Social Media Postings: An Experimental Study on Non-Governmental Organization. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2025, 37, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, I.; Phua, P. Generational Advertising: Literature Review and Practitioner Insights on Key Pitfalls and Implications. Int. J. Advert. 2025, 44, 286–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.; McCormick, H.; Warnaby, G. Consumers’ Emotional Responses to the Christmas TV Advertising of Four Retail Brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.