Abstract

Following and imitating others’ digital innovation decisions is not always grounded in rational judgment; it may also arise from blind conformity, reflecting a “herding behavior”. Drawing on a panel dataset of Chinese listed firms from 2010 to 2022, this study takes firms in the same industry as the reference group to investigate the existence, driving mechanisms, and economic consequences of corporate digital innovation convergence. The findings show that both breakthrough and incremental digital innovation exhibit convergence at the firm level and are jointly driven by information transmission, market competition, and resource dependence. However, the economic consequences of these two types of innovation convergence differ significantly. The convergence of breakthrough digital innovation enhances firms’ total factor productivity, return on equity, and capital market value, representing a positive peer effect, whereas the convergence of incremental digital innovation weakens these core indicators, reflecting a herding behavior. The heterogeneity analysis indicates that breakthrough digital innovation convergence is more pronounced in regions with stronger intellectual property protection and in industries with higher technology intensity, while incremental digital innovation convergence is more pronounced among private firms and in industries with lower technology intensity. Our findings provide valuable insights into the interactive dynamics of corporate digital innovation decisions and carry important implications for both theory and practice.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of following and imitating peers is widespread in both social and economic behavior, yet whether it truly yields economic returns remains debatable. According to existing literature [1,2], herding behavior essentially reflects a situation in which decision makers, under conditions of information asymmetry, abandon reliance on proprietary information and instead blindly conform to group behavior. In the field of behavioral economics, scholars attribute decision makers’ neglect of proprietary information to informational cascades and reputational concerns [3,4]. The former emphasizes that individuals, in uncertain environments, may disregard their own information due to the influence of others’ actions, while the latter argues that decision makers tend to conform to the majority in order to preserve their reputation.

However, in a complex and dynamic economic environment, firms relying solely on their limited information often struggle to sustain long-term development. Manski (1993) was among the first to systematically propose the “peer effect” hypothesis, which explains behavioral convergence arising from mutual influence between focal actors and their peers [5]. Under this hypothesis, decision convergence at the firm level does not necessarily embody blind herding behavior, but rather can be viewed as a rational, learning-based organizational strategy. By drawing on the decisions of industry peers, firms can not only reduce information costs and trial-and-error risks but also enhance legitimacy and recognition within the institutional environment.

Against the backdrop of the rapidly evolving global digital economy, digital innovation has become a critical engine for enhancing national competitiveness and driving sustainable growth. As the primary agents of digital innovation, firms do not make digital innovation decisions in isolation but rather within the context of diverse social networks. For example, industry peers, which often operate under common technological standards, quality norms, and market conditions, naturally serve as key reference points. Compared with relying solely on internal knowledge, drawing on external experiences from industry peers may be more effective in advancing the application of digital technologies from initial feasibility assessments to full operational integration [6]. However, in the context of corporate digital innovation, the boundary between herding behavior and peer effects becomes particularly blurred. Compared with traditional investment or technology diffusion processes, corporate digital innovation is characterized by network interconnection, dynamic evolution, and institutional embeddedness, which cause rational and irrational imitation among firms to intertwine.

First, the network interconnection feature of corporate digital innovation enhances the referential nature of corporate behavior. Unlike traditional technology diffusion, corporate digital innovation often occurs within cross-platform and cross-industry technology ecosystems [7]. Firms share algorithmic frameworks, data interfaces, and platform standards, making innovation activities highly interconnected and observable. This network linkage not only improves the efficiency of experiential and technological imitation but also aligns the pace of digital innovation among firms. As a result, rational and irrational imitation appear strikingly similar in external observation, potentially driven either by knowledge learning or by conformity pressure. Within such a tightly connected innovation network, herding behavior and peer effects become nearly indistinguishable at the observable level.

Second, the dynamic evolution feature of corporate digital innovation causes rational and irrational imitation to alternate frequently over time. Corporate digital innovation is characterized by continuous renewal and rapid iteration, with new technologies and business models spreading much faster than traditional innovation cycles [8,9]. As firms continuously experiment, adjust, and reinvest, the boundary between herding behavior and peer effects gradually becomes blurred over time. Early-stage active learning may evolve into passive conformity under market feedback and competitive pressure, while the rapid responses of latecomers may, in turn, be absorbed and reflected by pioneers, creating a cyclical feedback loop. As the pace of technology evolution and market response accelerates, firms’ cognitive references and competitive benchmarks are constantly redefined, making it increasingly difficult to distinguish rational learning from irrational conformity over time.

Third, the institutional embeddedness feature of corporate digital innovation amplifies the dual nature of corporate decision convergence. In the digital economy era, corporate digital innovation is not only a technological choice but also a policy response and a social symbol. When undertaking digital transformation, firms must develop capabilities through collaboration and resource complementarity [10], while also projecting a digitalized image to gain legitimacy and attract capital recognition [11,12]. As policy guidance, public scrutiny, and capital evaluation elevate the social significance of corporate digital innovation, capability-driven rational imitation and reputation-oriented irrational imitation coexist, further blurring the boundary between herding behavior and peer effects.

Although herding behavior and peer effects appear highly similar in both manifestation and underlying logic, the outcomes of active learning and blind imitation of peers’ digital innovation practices may differ considerably. Existing literature has demonstrated that corporate digital innovation exerts significant positive effects on measurable outcomes such as improving corporate social responsibility [13], enhancing firms’ total factor productivity [14], and promoting corporate sustainability [15]. However, these findings largely assume independent corporate decision-making, and empirical evidence on whether following and imitating others in corporate digital innovation activities can generate the expected “social multiplier effects” remains limited. As peer-driven activities expand beyond firm boundaries, following and imitation may generate positive externalities like knowledge sharing and technological synergy, but also negative outcomes such as resource congestion and path dependence.

Based on the above considerations, this paper uses data from Chinese A-share listed firms in Shanghai and Shenzhen during 2010–2022 to examine the existence, driving mechanisms, and economic consequences of convergence of corporate digital innovation. First, given that innovation is not homogeneous but varies by type, we distinguish between the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation and incremental digital innovation. Specifically, the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation refers to alignment with peers in the pursuit of originality, while the convergence of incremental digital innovation refers to alignment with peers in the pursuit of practical value. On this basis, we investigate the existence of convergence of corporate digital innovation and whether it can be divided into the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation and incremental digital innovation. Second, we explore how information transmission, market competition, and resource dependence influence the convergence of corporate digital innovation. Finally, we analyze the economic consequences of such convergence.

Our study makes the following contributions. First, we enrich the study of the determinants of corporate digital innovation by adopting a social interaction perspective. Existing research mainly rests on the assumption of independent corporate decision-making and pays limited attention to the influence of external actors on corporate digital innovation. By shifting the focus to the impact of industry peers’ digital innovation decisions, this paper provides new insights into the phenomenon of decision convergence among firms embedded in social networks. Second, we reveal the consistency between herding behavior and peer effects in both manifestation and driving mechanisms within the context of corporate digital innovation. Based on patent types, corporate digital innovation is classified into breakthrough and incremental categories, aligning with the practical pattern of digital patent applications among Chinese listed firms. The analysis shows that both types of corporate digital innovation exhibit significant convergence at the firm level and are jointly driven by mechanisms of information transmission, market competition, and resource dependence. Thus, our study provides empirical evidence for understanding the blurred and diverse nature of corporate digital innovation convergence. Third, we demonstrate the fundamental distinction between herding behavior and peer effects in the economic consequences of corporate digital innovation. Existing research has primarily focused on the advantages brought by corporate digital innovation itself, while little attention has been paid to the potential outcomes of the convergence of corporate digital innovation. The analysis shows that peer effects driven by rational imitation, which generate positive outcomes, are fundamentally different from herding behavior driven by irrational imitation, which produces negative outcomes. This distinction provides theoretical and practical insights for avoiding conformity in digital innovation.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

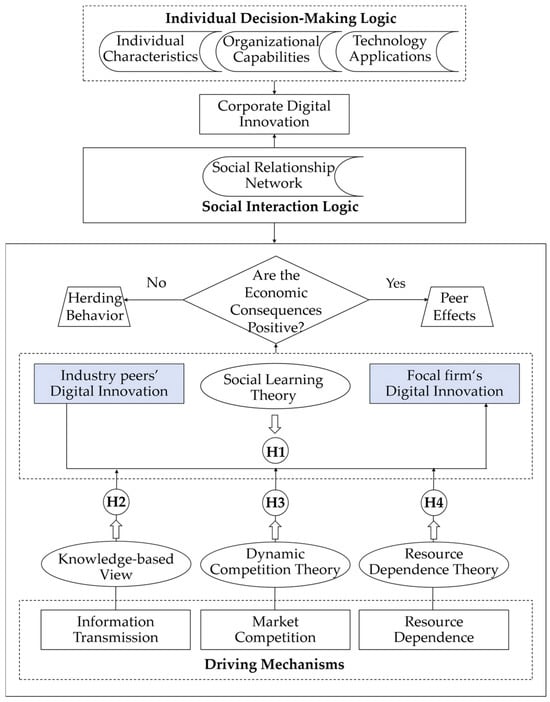

To enhance the logical coherence of the literature review, we first establish a theoretical analytical framework, as illustrated in Figure 1. The framework integrates the key factors influencing corporate digital innovation, the theoretical distinction between herding behavior and peer effects, and the logical progression of hypothesis development. Solid arrows represent causal relationships or process flows, while hollow arrows indicate theoretical support. Specifically, corporate digital innovation is shaped by both an individual decision-making logic and a social interaction logic. The former emphasizes the influence of internal factors such as individual characteristics, organizational capabilities, and technology applications on corporate digital innovation, while the latter focuses on the impact of peers within external relationship networks. When social interactions with peers lead to positive outcomes, they manifest as peer effects rooted in rational learning, whereas when social interactions with peers lead to adverse outcomes, they manifest as herding behavior driven by irrational conformity. Building on this framework, our study subsequently develops its research hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Theoretical analytical framework.

2.1. Influencing Factors of Corporate Digital Innovation

Existing studies mainly categorize the determinants of corporate digital innovation into three dimensions: individual characteristics, organizational capabilities, and technological applications. This categorization provides a solid foundation for understanding how firms improve their digital innovation performance. However, most of these studies have been conducted under the assumption of independent corporate decision-making, with limited attention to the interactions and linkages among firms in digital innovation activities.

Focusing on individual characteristics, existing research mainly involves executives with IT backgrounds, including the influence of newly established positions like Chief Information Officer (CIO) and Chief Digital Officer (CDO) on corporate digital innovation [16,17]. Executives with an IT background play a critical role in identifying corporate digital innovation opportunities, from integrating key elements to overcoming technological shortsightedness. Tumbas et al. (2018) and Scuotto et al. (2022) consistently found that companies assigning different individuals to oversee their digital strategies achieve diverse outcomes [18,19]. The CDO can leverage employees’ original expressions and interactions on digital platforms as guidance, directing the path of corporate digital innovation and promoting the sharing of digital knowledge.

Focusing on organizational capabilities, existing research mainly examines the impacts of big data capabilities and dynamic capabilities on corporate digital innovation [20,21]. In the digital economy era, the ability to extract and analyze key information from complex data resources is crucial for a company’s adaptability to market changes and its innovation conversion rate. Jiao et al. (2021) argued that effectively sensing and utilizing digital technology to manage data throughout its entire lifecycle is crucial for business and process innovation [22]. Wang et al. (2023) further classified dynamic capabilities into digital sensing, seizing, resource integration, and organizational transformation, emphasizing the role of dynamic capabilities in enhancing the quality of corporate digital innovation [23].

Focusing on technology application, existing research mainly discusses the potential and integrative nature of digital technology and its impact on corporate digital innovation. Cheng et al. (2022) and Liu et al. (2023) confirmed the positive impact of digital technology affordance on corporate digital innovation, with consistency and agility in search strategies playing a positive moderating role [24,25]. Unlike individual characteristics and organizational capabilities, technology application does not always promote corporate digital innovation. Wang et al. (2023) argued that the application of digital technology to drive technological innovation represents breakthrough organizational transformations, which must address challenges related to cost control, cybersecurity, and institutional legitimacy [26].

In summary, existing studies have provided substantial insights into how internal factors influence corporate digital innovation, but have paid less attention to the convergence of innovation decisions driven by interaction and imitation among firms. Therefore, by examining the existence, driving mechanisms, and economic consequences of convergence of corporate digital innovation, this study contributes to enriching the research framework on the influencing factors of corporate digital innovation.

2.2. Herding Behavior and Peer Effects

Herding behavior and peer effects are often discussed together, but they are not equivalent concepts. Herding behavior mainly emphasizes blind conformity under conditions of information asymmetry, which often results in efficiency losses or resource misallocation. In contrast, peer effects are grounded in the interaction logic of rational actors, highlighting the potential positive externalities generated by learning, imitation, and information transmission.

Peer effects originate from social network theory, which initially explored whether individuals’ behavioral decisions are influenced by the same social group or by others of similar status [27]. Compared with herding behavior, peer effects are rooted in the rational-choice framework of economics, emphasizing the internal logic of learning and imitation as well as the bidirectional nature of individual interactions [28]. Manski (1993) further noted in psychological studies that the “individual” in peer effects is not limited to persons, but also extends to firms, government agencies, and even nonprofit social service organizations [5]. Existing research has shown that firms exhibit pronounced peer effects in financial decisions [29], IPO [30], capital structure [31], and environmental and social responsibility [32]. These effects often rely on direct connections within industries or across firms in the same region. However, little systematic research has been conducted on peer effects in corporate digital innovation.

In summary, although both herding behavior and peer effects manifest as convergence of corporate decision-making, their consequences differ fundamentally. The former often leads to irrational conformity and negative outcomes, whereas the latter may generate positive results through information sharing and knowledge spillovers. Building on this distinction, this paper examines whether convergence of corporate digital innovation reflects a positive peer effect or a negative herding behavior.

2.3. Existence of the Convergence of Corporate Digital Innovation

According to social learning theory [33], corporate decision-making does not occur in isolation but is embedded within specific social relationship networks. In uncertain environments, firms observe and imitate the behaviors of others to reduce decision-making risks [34]. From the perspective of behavioral economics, this process reflects the behavioral logic whereby firms, constrained by bounded rationality, rely on external experience to update their cognition and adjust their decisions. In the context of corporate digital innovation, as more peers take the lead in adopting digital technologies, digital innovation gradually becomes socialized as an industry norm or ideal practice, thereby fostering the convergence of corporate digital innovation.

Driven by the motives of seeking benefits and avoiding losses, firms tend to imitate practices that have already been implemented and proven effective [35]. Specifically, when evaluating whether to invest in digital innovation, corporate decision makers simultaneously weigh two types of expected utilities: the opportunity cost of forgoing potential gains and the risk cost of avoiding potential losses. As more firms within the same social network take the lead in adopting digital innovation, the structure of these costs and benefits changes accordingly, thereby inducing convergence of corporate digital innovation. The logic can be summarized as follows:

First, from the perspective of benefit-seeking, corporate digital innovation is not only an essential path for modern firms to create value but also a key factor in achieving long-term competitive advantage. Specifically, through advanced digital tools and platforms, firms can enhance their capacity for product and service innovation and achieve process automation, thereby improving the data-driven nature of decision-making [36]. In addition, corporate digital innovation can also open up new business models and revenue streams [37], such as subscription-based services, predictive data analytics, and personalized marketing, all of which provide new avenues for growth. When firms observe their industry peers increasing digital investment and gaining market recognition, they tend to interpret these signals as positive effects of digital innovation, thereby increasing their own digital investment. This creates a rolling reinforcement of benefit-seeking incentives at the group level.

Second, from the perspective of loss-avoidance, the costs and risks of making digital innovation decisions independently are relatively high. Corporate digital innovation activities place substantial demands on firms’ technology, equipment, and talent allocation, while also involving long-term capital commitments and exposure to market instability [38]. By learning from and imitating peers that have succeeded in digital innovation, firms can reduce uncertainty in innovation investment and mitigate competitive threats, thereby improving technology implementation efficiency and lowering trial-and-error costs. As the number of pioneering firms increases, the opportunity costs faced by laggards accumulate more rapidly. To avoid marginalization in market competition, latecomer firms are often compelled to accelerate their digital innovation investments, thus creating a form of “passive synchronization” driven by loss-avoidance.

In summary, whether prompted by expected returns or risk aversion, firms’ decision adjustments reflect an organizational manifestation of social learning theory, which emphasizes reducing uncertainty by observing peers. Thus, the first hypothesis emerges as follows:

H1.

Corporate digital innovation exhibits significant convergence.

2.4. Driving Mechanisms of the Convergence of Corporate Digital Innovation

2.4.1. Information Transmission Mechanism

Information transmission constitutes the fundamental condition for the convergence of corporate decision-making. When certain firms possess relatively sufficient or superior information, their behaviors become important references for the decisions of other firms [39]. Particularly under high information noise, learning from peers can enhance the effectiveness of decision-making [40]. According to the knowledge-based view (KBV) [41], such informational learning reflects the process through which firms acquire, integrate, and apply external knowledge to compensate for internal cognitive deficiencies. Given the high uncertainty and complexity of digital innovation decisions, individual firms often find it difficult to identify optimal technological paths in an environment of information asymmetry. In this context, information such as peers’ investment orientations, R&D progress, changes in user demand, and market feedback constitutes key knowledge sources for learning and imitation. The flow of such external knowledge enhances firms’ adaptability and innovative capacity in the digital development environment by improving transparency and responsiveness in the decision-making process. Therefore, efficient information transmission enables firms to optimize existing products or adopt new technologies in a timely manner, thereby seizing market opportunities and maintaining industry positions. Moreover, efficient information transmission also fosters strategic cooperation and knowledge sharing among firms, which further strengthens innovation convergence within the industry. Thus, the second hypothesis emerges as follows:

H2.

Greater efficiency in information transmission leads to more pronounced convergence of corporate digital innovation.

2.4.2. Market Competition Mechanism

According to dynamic competition theory [42], market competition constitutes a non-equilibrium state shaped by the continuous strategic interactions among firms. Firms constantly adjust their strategic choices in response to competitors’ actions, forming an ongoing dynamic game relationship [43]. Schumpeter (1942) [42] emphasized that the continuous emergence of product and process innovation disrupts existing market structures, enabling leading firms to obtain temporary monopoly profits while forcing laggards to exit. The alternating cycle of innovation and imitation thus serves as the fundamental driving force of market vitality and industrial evolution. In the digital economy era, this cycle of innovation and imitation occurs with higher frequency and shorter duration. When peers take the lead in introducing and implementing new digital technologies, they can quickly secure excess profits and stronger market recognition. Therefore, imitating competitors’ actions becomes an effective way to prevent rivals from establishing competitive barriers and to maintain market position [44]. As the digital innovation outcomes of peers are continually validated by the market, observers realize that delaying investment only increases the marginal and learning costs of digital innovation. To avoid losing ground in dynamic competition, firms tend to rapidly imitate the digital innovation paths of their peers, thereby reinforcing the convergence of corporate digital innovation within the evolving competitive process. Thus, the third hypothesis emerges as follows:

H3.

Greater market competition leads to more pronounced convergence of corporate digital innovation.

2.4.3. Resource Dependence Mechanism

According to resource dependence theory [45], firms are not isolated or self-contained entities but are embedded in an external environment structured by resource exchange relationships. To obtain critical resources, firms inevitably depend on external actors such as suppliers, customers, and financial institutions. Under such conditions, firms that can reduce their resource dependence tend to maintain a higher level of strategic autonomy in dynamic environments [46]. In the domain of corporate digital innovation, such autonomy is particularly critical, as the rapid iteration of digital technologies requires firms to continuously acquire and integrate the latest hardware and software. For example, reducing resource dependence on suppliers allows firms to more flexibly select and integrate cutting-edge digital technologies and lowers the risk of innovation delays caused by the procurement of raw materials and technological components. Likewise, reducing resource dependence on customers frees firms from overly adjusting each step of innovation according to existing feedback, enabling more testing of user-centered products and services. However, once power asymmetry arises within resource-dependent relationships, a firm’s bargaining power is weakened, exposing it to greater uncertainty and external constraints [47]. Ultimately, high resource dependence not only undermines a firm’s strategic autonomy but also compels it to adopt risk-minimizing and imitative decisions in uncertain environments, thereby fostering convergence of corporate digital innovation. Thus, the fourth hypothesis emerges as follows:

H4.

Greater dependence on external resources leads to more pronounced convergence of corporate digital innovation.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data and Sample

In 2012, the Chinese government established digitalization as a strategic direction for promoting economic and social transformation. The National Informatization Development Strategy Outline issued in 2016 further proposed the goal of building a “Digital China”. By 2020, the added value of core digital economy industries had reached 7.8% of GDP. These top-level designs and policy initiatives have provided systematic institutional support and policy incentives for corporate digital innovation. Based on the principles of data availability and continuity, our study period is set from 2010 to 2022.

Our study takes Chinese A-share listed firms in Shanghai and Shenzhen as the research sample. On the one hand, listed firms are subject to standardized information disclosure requirements, and their financial and patent data are relatively complete, providing a solid basis for constructing large-scale firm-level panel data. On the other hand, corporate digital innovation is characterized by high investment and high risk, placing greater demands on firms’ resource endowment and governance capabilities. Listed firms, with their strong capital base and well-structured governance systems, are better equipped to undertake digital innovation activities, thereby offering suitable conditions for examining the convergence of corporate digital innovation.

The data used in this paper are primarily divided into patent data and listed firm data. The patent data are sourced from the IncoPat database, covering fields such as publication date, application date, patent type, patent validity, current legal status, and IPC (International Patent Classification). Listed firm data are obtained from the CSMAR database, the Wind database, corporate annual reports, and the official websites of listed firms, while the macro-level data are primarily drawn from provincial statistical yearbooks of China.

To ensure the reliability of the empirical analysis, the following data are excluded: (1) samples from the finance and insurance industries; (2) ST and *ST samples; (3) samples that were delisted during the period or had missing data. To reduce the impact of outliers, the top and bottom 1% of extreme values in the listed firm data are treated with Winsorization. Ultimately, the collected data are matched to the corresponding listed firm codes, yielding an unbalanced panel dataset comprising 22,358 firm-year observations from 3126 listed firms.

3.2. Variable Definition

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

Corporate digital innovation (DI). Following Pesch et al. (2021) and Zheng et al. (2023), the measurement of corporate digital innovation should focus more on outcomes rather than processes [48,49]. Accordingly, we use the number of digital patents filed by listed firms as a proxy for corporate digital innovation. Patent data, as a tangible manifestation of firms’ technological innovation achievements, is highly quantifiable and objective, thereby effectively avoiding subjective bias when examining the convergence of corporate digital innovation. Furthermore, since innovation is not homogeneous, we distinguish between breakthrough digital innovation (BTDI) and incremental digital innovation (INDI) in order to capture the internal heterogeneity of convergence of corporate digital innovation more clearly.

The IPC classification provides precise information on the technological domains of innovation activities. We identify firms’ digital patents through the following three steps: First, defining the IPC codes for digital patents. Based on the Statistical Classification of the Digital Economy and Its Core Industries (2021) issued by the National Bureau of Statistics and the Reference Table of International Patent Classification and National Economic Industry Classification (2018), we construct a three-level mapping system of “core industry codes of the digital economy—four-digit industry codes of the national economy (SIC4)—IPC codes (Subgroup)”. Through this procedure, we systematically identify the major technological domains involved in digital innovation and their corresponding IPC subgroup codes. In total, 899 IPC codes are selected, covering typical branches of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and blockchain.

Second, identifying digital patents. After determining the target IPC codes, we use them as keywords to retrieve information on digital patents filed by Chinese listed firms between 2010 and 2022 from the IncoPat global patent database, based on fields such as application date and patent type. Given the large volume of data, we developed a Python-based web crawler (Python 3.12) to automate data collection. After screening, we obtained approximately 490,000 digital invention patents and 220,000 digital utility model patents filed.

Third, constructing firm-level indicators of digital innovation. After obtaining the patent data, this paper further matches each patent with the stock code of its applicant firm and compiles the number of identified digital patents at the firm-year level. Invention patents generally represent firms’ exploration of entirely new products, processes, or business models, while utility model patents emphasize the optimization and refinement of existing technologies or products [50,51]. Therefore, this paper measures breakthrough digital innovation (BTDI) and incremental digital innovation (INDI) by using the log-transformed counts of digital invention patents and digital utility model patents, respectively.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

Industry peers’ digital innovation (M_DI). Following the approach of Manski (1993) [5], we measure industry peers’ breakthrough digital innovation (M_BTDI) and incremental digital innovation (M_INDI), constructing Equations (1) and (2) as follows:

where M_BTDI−i,j,t represents the average value of BTDI among peers (excluding company i) in industry j during year t, M_INDI−i,j,t represents the average value of INDI among peers (excluding company i) in industry j during year t. The industry classification is based on the secondary industry classification guidelines issued by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) in 2012.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Drawing on references on similar themes [35,52,53], we control for a range of other variables that might affect the empirical results, including firms’ size, age, profitability, growth rate, cash flow, debt-to-asset ratio, and liquidity ratio. Given the characteristics of research on peer effects, we also control for the aforementioned characteristics of industry peers. Moreover, as some firms experienced industry changes during the observation period, we further include firm, year, industry, and province fixed effects. The codes and definitions of the control variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of variables.

3.3. Model Specification

Drawing on the research approach of Leary (2014) [34], the baseline regression models (3) and (4) are constructed as follows:

where Controlsi,j,t represents the characteristic variables of the focal firm; M_Controls−i,j,t represents the average characteristic variables of industry peers; Firm, Year, Industry, and Province represent firm, time, industry, and regional fixed effects, respectively; εi,j,t represents the random disturbance term. Specifically, we test the existence of convergence of corporate digital innovation through the positive and negative signs of α1 and β1. If α1 > 0 and statistically significant, it indicates the existence of the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation. If β1 > 0 and statistically significant, it indicates the existence of the convergence of incremental digital innovation.

4. Empirical Tests

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of this study. Regarding the dependent variables, the mean of BTDI is 1.0461 with a standard deviation of 1.3311, while the mean of DI is 0.8817 with a standard deviation of 1.1999. The common feature that the standard deviation exceeds the mean suggests substantial variation in digital innovation across sample firms. The wide gap between the maximum and minimum values indicates that the sample includes both firms that conducted no digital innovation activities during the observation period and firms that actively invested in and achieved significant outcomes in digital innovation. Regarding the independent variables, the mean of M_BTDI is 1.0389 with a standard deviation of 0.6589, and the mean of M_INDI is 1.0417 with a standard deviation of 0.3726. It can be observed that the means of M_BTDI and BTDI, as well as those of M_INDI and INDI, are at roughly the same level, providing preliminary support for the hypothesis of convergence of corporate digital innovation.

Table 2.

Results of descriptive statistics.

4.2. Baseline Regression

Table 3 reports the regression results of the baseline model. We employ a multiple fixed effects model and a stepwise regression strategy, sequentially adding firm-level and industry-level control variables to verify the robustness of the regressions. In columns (1)–(3), the regression coefficients of industry peers’ breakthrough digital innovation (M_BTDI) remain significantly positive at the 1% level; in columns (4)–(6), the regression coefficients of industry peers’ incremental digital innovation (M_INDI) also remain significantly positive at the 1% level. These results indicate the existence of the convergence of both breakthrough and incremental digital innovation. In terms of economic significance (see columns (3) and (6)), a one–standard deviation increase in M_BTDI raises BTDI by approximately 0.27 units (=0.4157 × 0.6589), equivalent to 26.18% of the sample mean (=0.2739/1.0461); a one–standard deviation increase in M_INDI raises INDI by approximately 0.22 units (=0.3591 × 0.6212), equivalent to 25.30% of the sample mean (=0.2231/0.8817). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is confirmed.

Table 3.

Results of baseline regression.

Real-world cases also reflect convergence of corporate digital innovation. Taking the home appliance industry as an example, Midea took the lead in 2016 by launching the “M-Smart Home Strategy”, which demonstrated new forms of products and services driven by digital technologies through the construction of an IoT platform and intelligent manufacturing system. Subsequently, Haier accelerated the rollout of the “Cosmoplat Industrial Internet Platform”, achieving cross-firm and cross-industry platform-based innovation in areas such as smart homes and intelligent manufacturing. Gree Electric, in turn, established a self-developed intelligent production system, enabling full-process digital monitoring of its core component production lines and enhancing quality traceability and energy management capabilities with the support of big data. Combined with the econometric results of our study, these cases suggest that convergence of corporate digital innovation is not only statistically and economically significant but also concretely observable in practice.

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Replacing Core Variables

In the baseline regression model, corporate digital innovation (DI) is measured by the number of digital patent applications. In this section, we use two alternative measures: (i) the proportion of digital patent applications in total patent applications, (ii) the number of granted digital invention patents. Based on these alternative measures, we recalculate industry peers’ breakthrough digital innovation (M_BTDI) and incremental digital innovation (M_INDI) according to Equations (1) and (2) to further test the robustness of the baseline regression. Table 4 reports the corresponding regression results. It can be observed that the regression coefficients of M_BTDI and M_INDI remain significantly positive at least at the 5% level. Therefore, the basic conclusion of “convergence of corporate digital innovation” continues to hold.

Table 4.

Results of replacing core variables.

4.3.2. Replacing Econometric Models

In terms of model specification, this section further employs Tobit and Negative Binomial regression models to verify the robustness of the baseline results. First, when measured by the number of patent applications, the dependent variable has some zero observations (firms that did not apply for any digital patents in a given year). Therefore, the significance of the regression results may be affected by a left-censored distribution of the dependent variable. To address this issue, we re-estimate the baseline model using a Tobit regression. Columns (1) and (3) of Table 5 report the corresponding results, showing that the coefficients of M_BTDI and M_INDI remain significantly positive at least at the 5% level.

Table 5.

Results of replacing econometric models.

Second, the dependent variable, measured by the number of patent applications, is a typical count variable. Statistical tests indicate that its variance is substantially greater than its mean, reflecting overdispersion, which may lead to underestimated standard errors or biased coefficient estimates. To address this concern, we re-estimate the baseline model using a Negative Binomial regression. Columns (2) and (4) of Table 5 report the corresponding results, showing that the coefficients of M_BTDI and M_INDI remain significantly positive at the 1% level. Therefore, the basic conclusion of “convergence of corporate digital innovation” is not altered by changes in model specification.

4.3.3. Replacing Social Relationship Network

This section introduces regional peers to further test the robustness of the baseline results from a spatial linkage perspective. As Li and Wang (2022) [54] found, the level of corporate social responsibility (CSR) engagement of listed firms tends to align with that of other listed firms headquartered nearby. The convergence of corporate digital innovation among firms within the same region may rest on three fundamental aspects. First, spatial proximity facilitates the local spillover of digital innovation knowledge. Compared with firms in the same industry, geographic closeness can more effectively reduce information acquisition costs among local firms and enhance the timeliness of problem-solving. Second, corporate digital innovation relies heavily on regional digital infrastructure, such as computing power platforms, industrial internet systems, and data centers. These infrastructures are typically developed under the leadership of local governments or major firms, possessing strong regional attributes and externalities. Third, local policy orientation shapes a shared direction for corporate digital innovation. Unlike institutional or regulatory arrangements at the industry level, local policies do not aim to establish uniform standards but rather to directly foster a coordinated pattern of regional development.

Under the premise of keeping the original model and variable settings unchanged, we redefine firms located within the same province as regional peers. Accordingly, we recalculate regional peers’ breakthrough digital innovation (R_BTDI), incremental digital innovation (R_INDI), and relevant characteristics (R_Controls). Table 6 reports the corresponding stepwise regression results. As shown, in columns (1)–(3), the coefficients of R_BTDI are significantly positive at least at the 5% level, while in columns (4)–(6), the coefficients of R_INDI remain significantly positive at the 1% level. Therefore, even when our study is conducted within a spatial linkage network, corporate digital innovation decisions still exhibit a significant convergence pattern.

Table 6.

Results of replacing social relationship network.

4.3.4. Placebo Test

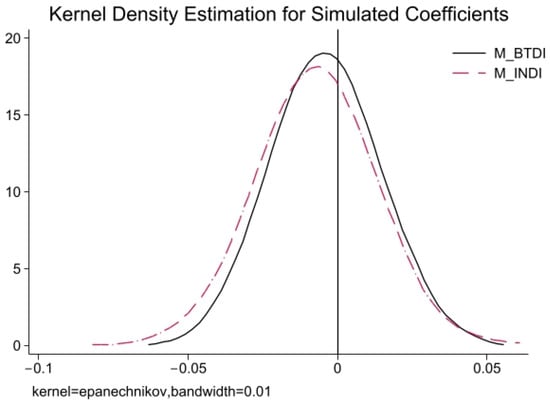

Omitted variables may distort the causal relationship between industry peers’ digital innovation and the focal firm’s digital innovation, thereby affecting the observed results of decision convergence. Since it is impossible to exhaust all control variables, this section constructs two sets of placebo samples with no real economic meaning, such that any convergence observed in the simulated samples is entirely driven by random assignment. This allows us to assess whether the baseline regression suffers from omitted variable bias.

Specifically, while keeping the control variables unchanged, we randomly reassign industry peers’ digital innovation indicators within the same firm and then re-estimate the model on the simulated samples. This process is repeated 1000 times. If the simulated coefficients of M_BTDI and M_INDI remain significantly positive, it would suggest that the baseline regression omitted important variables. Otherwise, it would indicate that convergence of corporate digital innovation truly exists at the industry level.

Figure 2 presents the kernel density distributions of the simulated coefficients of M_BTDI and M_INDI. It can be observed that all 1000 simulated coefficients of M_BTDI and M_INDI are far from the baseline regression results and approximately follow a normal distribution centered around zero, implying that convergence of corporate digital innovation cannot be observed under random allocation. Moreover, the simulated coefficients are consistently much smaller than the actual regression coefficients (see Table 7), suggesting that the convergence observed in the baseline regression is not driven by unobservable factors, thereby further reinforcing the robustness of the baseline results.

Figure 2.

Kernel density distributions of simulated coefficients.

Table 7.

Results of placebo test.

4.4. Endogeneity Tests

4.4.1. Instrumental Variable Test

Following the studies of Liu et al. (2023) and Li & Ding (2024) [55,56], we adopt industry peers’ stock idiosyncratic returns (M_SIR) and the one-period lagged independent variables (L1.M_BTDI and L1.M_INDI) as instrumental variables and conduct two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation.

The validity of the instrumental variables is reflected in two main aspects. First, regarding relevance, the industry peers’ idiosyncratic stock returns can effectively capture market expectation changes induced by industry peers’ digital innovation. When industry peers increase their investment in digital innovation, investors adjust their pricing decisions based on innovation-related information, leading to an excess reaction reflected in the idiosyncratic returns. Therefore, the industry peers’ idiosyncratic stock returns are significantly and positively correlated with industry peers’ digital innovation, satisfying the relevance requirement of the instrumental variables. Second, regarding exogeneity, the industry peers’ idiosyncratic stock returns reflect the non-systematic market performance of industry peers and are not directly related to an individual firm’s digital innovation. Unlike overall stock returns, idiosyncratic returns exclude systematic factors such as market and industry effects, and thus do not influence an individual firm’s innovation decision through common channels. This satisfies the exogeneity requirement of the instrumental variables. In addition, the one-period lagged peers’ digital innovation captures the dynamic persistence of digital innovation activities. It is highly correlated with current peers’ digital innovation but does not directly affect an individual firm’s current decision-making, and therefore serves as a supplementary instrumental variable.

In China’s capital market, stock liquidity exerts a particularly significant effect on stock prices, especially during periods of market volatility and economic uncertainty. Therefore, we construct industry peers’ stock idiosyncratic returns with further consideration of stock liquidity risk. Specifically, we first build a five-factor model that incorporates market, size, book-to-market ratio, trading volume, and turnover, as shown in Equation (5):

where Ri,j,t represents the stock return of company i in industry j during month t; Rft represents the risk-free rate during month t; M_R−i,j,t represents the stock return of industry peers of company i during month t; MKTt, SMBt, HMLt, VOLt, and TORt represent the market, size, book-to-market ratio, trading volume, and turnover factors, respectively.

Second, at the beginning of each year, we use data from the preceding 36 months to estimate the regression coefficients according to Equation (5). Subsequently, in each month of that year, we apply the estimated coefficients to compute the expected value of monthly excess returns () and the idiosyncratic returns of each stock (), as shown in Equations (6) and (7):

Finally, based on individual stock idiosyncratic returns, we calculate the stock idiosyncratic returns of industry peers (M_SIR). Together with the one-period lagged independent variables (L1.M_BTDI and L1.M_INDI), these serve as the instrumental variables in our study, and we estimate the model using 2SLS. Table 8 reports the corresponding regression results.

Table 8.

Result of instrumental variable test.

It can be observed that in columns (1) and (3), the instrumental variables are all significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating a strong correlation between the instruments and the endogenous variables, thus satisfying the relevance condition of instrumental variable selection. In columns (2) and (4), the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistics (LM = 7075.3480/4617.9080, p < 0.01) reject the null hypothesis of underidentification, confirming that the model is identifiable. Meanwhile, the Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistics (F = 14000/5900) are far above the 10% critical value of the Stock-Yogo test (critical value = 16.38), rejecting the weak instrument hypothesis and demonstrating that the instruments have sufficient explanatory power. More importantly, the independent variables (M_BTDI and M_INDI) remain significantly positive at the 1% level, further confirming the robustness of the main findings.

4.4.2. System GMM Model

Although substantial effort has been devoted to constructing instrumental variables that align with the Chinese context, these variables may still have certain limitations. For instance, an individual firm’s digital innovation also exhibits dynamic persistence and may have a bidirectional causal relationship with firm-specific characteristics such as profitability and growth.

Therefore, this section further addresses the potential endogeneity of the baseline regressions by employing the two-step System GMM model. Specifically, we construct a dynamic panel model by including the one-period lagged dependent variable in the baseline regression. Table 9 reports the corresponding regression results.

Table 9.

Results of system GMM model.

First, we test the validity of the System GMM model. The differenced error terms show first-order autocorrelation (AR(1) = 0.0000 < 0.01) but no second-order autocorrelation (AR(2) = 0.6500/0.3800 > 0.01), which satisfies the GMM requirement regarding serial correlation in the residuals. Second, the Hansen overidentification test (J = 0.8140/0.6990 > 0.01) fails to reject the null hypothesis that all instrumental variables are exogenous, supporting the validity of the instruments. Therefore, the choice of regression method is appropriate.

Finally, the one-period lagged dependent variables (L1.BTDI and L1.INDI) are both significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating dynamic persistence in corporate digital innovation. The independent variables (M_BTDI and M_INDI) are significantly positive at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively, further confirming the robustness of the baseline findings.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Intellectual Property Protection

We construct an index of intellectual property protection (IPP) based on the National Intellectual Property Development Status Report issued by the China National Intellectual Property Administration. Using the median value of the index, we divide the full sample into a strong IPP group and a weak IPP group. Table 10 reports the corresponding subgroup regression results. The findings show that in the strong IPP group, the regression coefficient of M_BTDI is 0.4551 and significant at the 1% level. In the weak IPP group, the coefficient of M_BTDI is 0.2411 and significant at the 5% level. Furthermore, the empirical p-values derived from 1000 Bootstrap replications indicate that the regression coefficients of M_BTDI differ across the two groups at the 5% significance level. These results suggest that the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation is more pronounced under strong intellectual property protection.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity results based on intellectual property protection.

A potential explanation is that strong intellectual property protection effectively reduces firms’ potential losses in high-risk and high-cost innovation activities, while enhancing the exclusivity of technological returns, thereby incentivizing industry peers to engage in breakthrough digital innovation. In contrast, under weak intellectual property protection, breakthrough digital innovation fails to establish solid property-rights barriers, leaving firms exposed to higher risks of free-riding. Consequently, firms are more inclined to pursue incremental digital innovation, which requires lower implementation costs and technological thresholds, in order to maintain consistency with their industry peers.

4.5.2. Technology Intensity

Based on the high-technology industry classification standards defined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the High-Technology Industry (Manufacturing) Classification (2017) issued by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, we divide the full sample into a high technology intensity (TIN) group and a low technology intensity group. High-technology-intensity industries include computer, communication and other electronic equipment manufacturing; electrical machinery and equipment manufacturing; pharmaceutical manufacturing; automobile manufacturing; railway, ship, aerospace and other transportation equipment manufacturing; specialized equipment manufacturing; and instrumentation manufacturing. Others are classified as low-technology-intensity industries. Table 11 reports the corresponding subgroup regression results. The findings show that in the high TIN group, the regression coefficient of M_BTDI is 0.5231 and significant at the 1% level, while that of M_INDI is 0.2386 and significant at the 5% level. In the low TIN group, the regression coefficient of M_BTDI is 0.2765 and significant at the 5% level, whereas that of M_INDI is 0.4618 and significant at the 1% level. Furthermore, the empirical p-values derived from 1000 Bootstrap replications indicate that the regression coefficients of M_BTDI and M_INDI both differ across the two groups at the 5% significance level. These results suggest that the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation is more pronounced in high-technology-intensity industries, whereas the convergence of incremental digital innovation is more pronounced in low-technology-intensity industries.

Table 11.

Heterogeneity results based on technology intensity.

A potential explanation is that, in high-technology-intensity industries, firms’ competitive advantages rely on continuous breakthroughs in digital technologies. Breakthrough digital innovation can fundamentally transform production methods, business models, and even industrial structures, becoming a crucial force reshaping industrial dynamics. In addition, firms in high-technology-intensity industries usually possess strong R&D capabilities and accumulated technical expertise, enabling them to undertake high-risk and high-investment breakthrough digital innovation. In contrast, firms in low-technology-intensity industries tend to focus on the continuous improvement of existing technologies and processes. In such contexts, incremental digital innovation helps enhance operational efficiency and improve service quality to meet stable and mature market demands.

4.5.3. Ownership Type

Based on ownership type, we divide the full sample into state-owned firms (SOEs) and privately owned firms (POEs). Table 12 reports the corresponding subgroup regression results. The findings show that in the SOE group, the regression coefficient of M_INDI is 0.1955 and significant at the 1% level, while in the POE group, the coefficient of M_INDI is 0.4026 and also significant at the 1% level. Moreover, the empirical p-values derived from 1000 Bootstrap replications indicate that the regression coefficients of M_INDI differ between the two groups at the 5% significance level. These results suggest that the convergence of incremental digital innovation is more pronounced among private firms.

Table 12.

Heterogeneity results based on ownership type.

A potential explanation is that private firms face stronger resource constraints and financing pressures in the process of digital innovation. Incremental digital innovation, given its lower costs and easier implementation, can generate tangible returns in a relatively short period, making it a more attractive choice for private firms seeking to respond quickly to market changes and consumer demand. In contrast, state-owned firms benefit from more stable funding and policy support, and their digital innovation activities are more long-term and strategically oriented, thereby reducing their reliance on incremental digital innovation.

5. Further Analyses

5.1. Driving Mechanism Analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the complex drivers behind the convergence of corporate digital innovation, this section further examines how industry peers’ digital innovation influences a focal firm’s digital innovation. Specifically, we discuss the driving mechanisms from three perspectives: information transmission, market competition, and resource dependence. Accordingly, we construct the regression models (8) and (9) as follows:

where DMV represents the driving mechanism variable; and represent the interaction terms between the driving mechanism variables and industry peers’ digital innovation. and are the regression coefficients we focus on in the mechanism analysis. If > 0 and statistically significant, it indicates that the factor promotes the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation. Similarly, if > 0 and statistically significant, it indicates that the factor promotes the convergence of incremental digital innovation. Conversely, a negative and significant value suggests that it hinders convergence.

5.1.1. Analysis of Information Transmission Mechanism

Following the approach of Arduino et al. (2024) [57], we use the shareholding ratio of institutional investors as a proxy variable for the information transmission, denoted as PII. A higher proportion of institutional ownership is generally regarded as a symbol of greater information transmission efficiency. Institutional investors, such as pension funds, insurance companies, and mutual funds, typically have professional investment management teams and strong information analysis capabilities. They tend to invest in firms with more comprehensive information disclosure in order to reduce investment risk. In addition, institutional investors usually pay closer attention to firms’ operational activities and financial conditions, and they exercise their monitoring rights through channels such as shareholder meetings and boards of directors, thereby encouraging firms to further enhance their information transparency. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 11 report the corresponding regression results. It can be observed that the coefficient of M_BTDI × PII is 0.2694 and significant at the 1% level, while the coefficient of M_INDI × PII is 0.2956 and also significant at the 1% level. These findings suggest that information transmission promotes convergence of corporate digital innovation, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2.

5.1.2. Analysis of Market Competition Mechanism

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index is a commonly used indicator for measuring the intensity of market competition [58]. It evaluates the competitive landscape within an industry by reflecting market concentration, denoted as HHI. In this section, we calculate the HHI using the share of operating revenue, which better captures firms’ market power since firms with higher revenues typically possess stronger market influence and pricing power, thereby occupying a dominant position in market competition. A higher value of HHI indicates that the market tends toward monopoly or oligopoly, whereas a smaller value of HHI suggests that the market is closer to perfect competition. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 11 report the corresponding regression results. It can be observed that the coefficient of M_BTDI × HHI is 0.4641 and significant at the 1% level, while the coefficient of M_INDI × HHI is 0.4031 and also significant at the 1% level. These findings suggest that market competition promotes convergence of corporate digital innovation, thereby supporting Hypothesis 3.

5.1.3. Analysis of Resource Dependence Mechanism

Following the approach of He et al. (2024) [59], we measure firms’ dependence on external resources using supply chain concentration. Specifically, customer concentration is measured by the sales share of the top five customers, supplier concentration is measured by the purchase share of the top five suppliers, and the average of the two is used to measure overall supply chain concentration, denoted as SCC. A higher level of supply chain concentration indicates that a firm is highly dependent on a small number of partners, thereby increasing operational risks and market uncertainty. Columns (5) and (6) of Table 13 report the corresponding regression results. It can be observed that the coefficient of M_BTDI × SCC is 0.7643 and significant at the 1% level, while the coefficient of M_INDI × SCC is 0.5826 and also significant at the 1% level. These findings suggest that resource dependence promotes convergence of corporate digital innovation, thereby supporting Hypothesis 4.

Table 13.

Results of driving mechanism test.

5.2. Economic Consequence Analysis

We examine the economic consequences of convergence of corporate digital innovation by selecting total factor productivity, return on equity, and capital market value as outcome variables, in order to test whether such convergence can truly achieve cost reduction and efficiency improvement. The testing procedure is as follows:

First, calculating proxy variables for economic consequences. Following the approaches of Krishnan et al. (2015) and Giannetti et al. (2015) [60,61], we start with the Cobb–Douglas production function and use Equation (10) as the basis for computing firm’s total factor productivity. Specifically, Y represents operating revenue, K represents the net value of fixed assets, L represents the number of employees, and M represents the cash paid for purchasing goods and services. The residual term obtained from the regression is denoted as TFP, return on equity is measured by the ratio of net profit to shareholders’ equity and capital market value is measured by the ratio of market value to total assets, denoted as ROE and Tobin’s Q, respectively.

Second, calculating proxy variables for convergence of corporate digital innovation. We take α1 × M_BTDI−i,j,t and β1 × M_INDI−i,j,t from the baseline regression as the proxy variables for the convergence of breakthrough and incremental digital innovation, denoted as Peer_BTDI−i,j,t and Peer_INDI−i,j,t, respectively. Third, constructing Equations (11) and (12) for economic consequences analysis. We separately assess the economic consequences of the convergence of breakthrough and incremental digital innovation through and , while keeping the control variables and fixed effects consistent with the baseline regression.

Columns (1)–(3) of Table 14 report the economic consequences of the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation. It can be observed that the regression coefficients of Peer_BTDI are all positively significant at the 1% level, indicating that the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation improves firms’ total factor productivity, return on equity, and capital market value. Specifically, by aligning with industry peers in breakthrough digital innovation decisions, firms are able to mitigate efficiency losses in production and enhance profitability. Investors tend to interpret such convergence as a signal of firms’ growth potential and forward-looking strategy, thereby granting them higher valuation premiums. Accordingly, the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation can be regarded as a rational “peer effect”.

Table 14.

Results of economic consequence test.

Columns (4)–(6) report the economic consequences of the convergence of incremental digital innovation. It can be observed that in Column (4), the regression coefficient of Peer_INDI is negatively significant at the 10% level. In Column (5), it is negatively significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the convergence of incremental digital innovation reduces firms’ total factor productivity and return on equity. Specifically, by aligning with industry peers in incremental digital innovation decisions, firms not only fail to obtain substantial returns but also weaken the efficiency and effectiveness of digital innovation. Accordingly, the convergence of incremental digital innovation can be regarded as a conformity-driven “herding behavior”.

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion

Whether manifested as irrational herding behavior or rational peer effects, the convergence of corporate digital innovation essentially reflects the outcome of firms imitating and following their peers in a highly interconnected informational environment. Unlike traditional investment decisions or technology diffusion, corporate digital innovation operates through a logic characterized by network interconnection, dynamic evolution, and institutional embeddedness. These features blur the boundary between herding behavior and peer effects. Thus, this study takes corporate digital innovation as its research context and explores the formation and economic consequences of digital innovation convergence.

First, based on firms’ innovation motives, this study distinguishes between breakthrough and incremental digital innovation, and verifies the existence of convergence in both types. This finding resonates with the conclusions of Li et al. (2023) [62] and Ma et al. (2025) [63] on the peer effects of corporate digital innovation, while further providing empirical evidence for understanding the ambiguity and diversity of corporate digital innovation. From the perspective of social learning theory, firms operating in uncertain environments continuously observe and refer to the innovation activities of their peers to obtain information on technological trajectories and market responses. In the pursuit of originality through breakthrough digital innovation, peer experiences expand firms’ cognitive boundaries and help identify potential technological pathways. In the pursuit of practicality through incremental digital innovation, peer experiences guide firms in optimizing production processes and improving resource efficiency. Consequently, regardless of whether the innovation motive is to pursue breakthrough or incremental digital innovation, peer decisions play a crucial role in shaping the direction of firms’ digital innovation.

Second, this study identifies information transmission, market competition, and resource dependence as the three primary mechanisms driving the convergence of corporate digital innovation. The information transmission mechanism, grounded in the knowledge-based view (KBV), emphasizes that firms acquire external knowledge and update cognitive structures through learning from and imitating the digital innovation decisions of peers [64]. The market competition mechanism, consistent with dynamic competition theory, suggests that under market pressure, firms imitate the digital innovation decisions of peers to maintain legitimacy and competitive advantage [44]. The empirical evidence for both mechanisms aligns with the findings of Lieberman and Asaba (2006) [65], who demonstrated that information learning and industry competition are critical forces driving imitation in innovation decisions. The resource dependence mechanism draws on resource dependence theory. Compared with traditional technological innovation, the rapid iteration of digital technologies makes corporate digital innovation more reliant on external resources such as data, algorithms, platforms, and talent. To access these essential resources, firms inevitably depend on external actors such as suppliers and customers. This finding echoes the argument of Xue et al. (2024) [66], who identified resource scarcity as a key determinant of convergence in corporate decision-making.

Finally, this study finds that the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation significantly enhances firms’ total factor productivity, return on equity, and market valuation. This finding indicates that imitating breakthrough digital innovation enables firms to accumulate capabilities and create value by restructuring their knowledge bases and technological paths. In contrast, the convergence of incremental digital innovation reduces firms’ total factor productivity and return on equity, suggesting that imitation of incremental digital innovation is more likely to evolve into destructive and blind conformity. This finding departs from Wu et al. (2023) [67] and Yang et al. (2024) [68], who generally recognize the positive effects of decision convergence, and reveals a fundamental divergence between herding behavior and peer effects in the digital innovation context. The latter embodies rational learning and knowledge absorption, whereas the former reflects irrational imitation and institutional pressure. Therefore, this study not only challenges the linear assumption that collective behavior is necessarily beneficial or harmful but also provides a realistic context for distinguishing herding behavior from peer effects.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

The theoretical implications of our study are as follows.

First, we situate corporate digital innovation within social networks. Unlike prior studies that assume firms make decisions independently, we show that corporate digital innovation does not exist in isolation but is embedded in collective interactions and institutional environments. This perspective extends the analytical boundary of corporate digital innovation research from individualized rational choice to network-based interactive processes.

Second, we extend peer effect research by introducing corporate digital innovation. Furthermore, by distinguishing between the convergence of breakthrough and incremental digital innovation, we demonstrate that corporate digital innovation and inter-firm collective behavior are not homogeneous. This provides theoretical insights for exploring the decision-making logic and diversity of corporate digital innovation under conditions of uncertainty.

Third, we distinguish rational peer effects from irrational herding behavior and challenge the linear view that collective behavior is beneficial or harmful by comparing the economic consequences of the convergence of breakthrough and incremental digital innovation. Therefore, convergence of corporate digital innovation not only reflects the complexity of collective behavior but also provides a concrete and distinctive application scenario for distinguishing between peer effects and herding behavior.

6.3. Practical Implications

The practical implications of our study are as follows.

First, listed firms and their managers need to clearly distinguish rational peer learning from irrational herding, as the two lead to very different economic outcomes. Our empirical evidence shows that peer decisions can offer useful aggregated information and professional insight. These signals help firms react more quickly to market changes and better evaluate the risks of new technologies. However, blindly copying others’ digital innovation practices may still cause economic losses, particularly for firms with weaker technological capabilities. Before adopting new digital technologies, firms should therefore examine whether these technologies are compatible with their existing business processes and organizational structures. Strategic choices should strike a balance between technological progress and operational practicality, rather than adopting digital tools simply because they are fashionable. Firms also need internal evaluation mechanisms that help them judge whether a peer’s practice genuinely fits their own situation, instead of following it just because “others are doing it.” Such mechanisms ensure that peer learning remains evidence-based and aligned with firm-specific goals, which in turn reduces the risk of non-value-creating herding.

Second, for the government and its market regulatory departments, it is essential to build a sound and professional innovation ecosystem. On the one hand, the government should actively implement intellectual property protection policies and antitrust regulations to ensure fair market competition. For example, when developing industry technical standards, policymakers should gather input from a wide range of firms to ensure that both follower firms and private firms can innovate on an equal footing. They should also offer stronger R&D incentives in regions with stronger intellectual property protection, and strengthen law enforcement in regions with weaker protection. On the other hand, the government should enhance its professional role in supporting corporate digital innovation. For example, investing in the construction of public digital innovation centers and providing specialized digital R&D, testing, and evaluation services can lower the barriers and risks associated with digital innovation. Furthermore, the government should regulate the market behavior of technology providers and media to prevent misleading promotion of digital technology capabilities.

Beyond the specific measures discussed above, the policy implications of this study lie in fully recognizing the ambiguity and diversity inherent in corporate digital innovation convergence. Policymakers should encourage firms to share specialized knowledge to strengthen the positive externalities of convergence in breakthrough digital innovation. At the same time, they should remain alert to the negative externalities that may arise from convergence in incremental digital innovation, such as technological homogenization and resource misallocation. Accordingly, digital innovation policies should no longer focus solely on expanding digital adoption. Instead, they should aim to balance innovation quality with structural differences across industries and firms, allowing diverse and distinctive paths of digital innovation to emerge in an open and dynamic environment.

7. Conclusions

Faced with the practical challenges of integrating the digital and real economies, this study systematically investigates the convergence of digital innovation among listed firms along the logical chain of “existence-driving mechanisms-economic consequences”. Adopting this logical chain helps to understand the critical role of social networks in driving corporate digital innovation and the actual effects of following and imitating peers’ digital innovation decisions. The core findings can be summarized in three aspects:

First, convergence of corporate digital innovation includes both the convergence of breakthrough and incremental digital innovation. The former is more pronounced under strong intellectual property protection, while the latter is more evident among private firms. Second, information transmission, market competition, and resource dependence consistently serve as the main driving mechanisms of convergence of corporate digital innovation. Third, the convergence of breakthrough digital innovation largely reflects a rational peer effect, significantly enhancing firms’ total factor productivity, return on equity, and capital market value. In contrast, the convergence of incremental digital innovation tends to embody a herding behavior characterized by a lack of differentiation and foresight, thereby exerting negative impacts on firm development.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study advances theoretical understanding and provides robust empirical evidence, several limitations remain that warrant deeper exploration in future research. To ensure logical coherence and analytical precision, three directions for further investigation are proposed.

First, regarding sample selection, our study focuses on Chinese listed firms to ensure data reliability and the robustness of conclusions. However, this focus also constrains the applicability of the findings to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and other economic systems. Despite their numerical dominance, SMEs are often excluded from systematic analysis due to limitations in data availability and completeness. Future research could extend the analytical framework to the SMEs as data quality improves, thereby revealing how firm size shapes patterns of digital innovation convergence. Moreover, incorporating cross-country samples could help examine how variations in institutional environments and digital infrastructure influence corporate digital innovation convergence, thereby building a more generalizable analytical framework.

Second, in identifying social relational networks, this study primarily examines industry-level and region-level peer networks. These networks provide clear and quantifiable analytical units under conditions of technological homogeneity, institutional similarity, and observable information flows. However, many social relationship networks can be more complex, such as executive interlocking, equity linkages, supply chain collaborations, or digital platform ecosystems. Future research could conduct comparative analyses to explore how peer firms at the centers of these networks influence the innovation direction and quality of focal firms.

Third, in assessing the consequences of corporate digital innovation convergence, this study mainly considers its economic implications, reflecting changes in firms’ operational and financial performance. However, corporate digital innovation inherently offers advantages in improving resource utilization efficiency, optimizing production processes, and reducing environmental burdens. Therefore, convergence of corporate digital innovation may also influence firms’ carbon reduction efficiency and ESG performance. Future research could integrate the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into the analytical framework to systematically evaluate the role of corporate digital innovation convergence in promoting green transformation and sustainable corporate governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.M., A.S. and S.D.; methodology, Z.M.; software, Z.M.; validation, Z.M., A.S. and S.D.; formal analysis, Z.M.; investigation, Z.M.; resources, Z.M. and Z.S.; data curation, Z.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.M.; writing—review and editing, Z.M., A.S., S.D. and Z.S.; visualization, Z.M. and S.D.; supervision, A.S. and Z.S.; project administration, Z.M., A.S. and Z.S.; funding acquisition, Z.M. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding