Abstract

Through the actions and interactions of video platform users, talent shows have expanded from the entertainment sphere to the social sphere and become an everyday part of life. Watching talent shows on online platforms, especially through participation in multi-platform interaction, is an ever developing and innovative field in many regions. This study adopts a multiple case analysis approach. We analyze and compare three cases of talent shows, examining aspects of their value co-creation, digital platform, dynamic capability and value network through an exploration of a series of creative activities on digital video platforms. Talent shows provide a unique environment in which different actors interact, co-exist and co-create value, i.e., another form of O2O marketing. These actors include producers, entertainment companies, sponsors and fans, and fan value co-creation currently takes many different forms, which are experienced, engaged and interacted with through different platforms. The findings contribute to examining the underlying dynamics of TV talent shows, in addition to explaining how they are achieving sustainable advantages in the media market. Furthermore, this study aims to understand the service ecosystem of network talent shows from the perspective of industrial innovation strategy; consequently, this research can help to promote the implications of this new form of digital content services and its innovation strategies.

1. Introduction

The video has not only become a tool for daily communication and entertainment for the public, but also activates the audience’s visual and auditory perceptions, resulting in spatial and cultural meaning [1]. According to the 2022 Chinese Fans Economic Overview by Leadleo Research, the benefits generated by the fan economy are gradually becoming apparent with the rise of talent shows. The market size generated by variety shows is projected to grow to 6.33 billion Yuan by 2026. The number of paid members on streaming service platforms has increased by nearly 10 million in just three months, while online sales for titleholders have increased 500 times. Hong Kong TV platforms have seen a 66% increase in advertising revenue in six months through talent shows, and the advertising endorsements of talent groups account for 70% of all advertising in Hong Kong. The technologies and business practices of television have changed with them, and the felt experience of engaging with television has also shifted [2].

With the rise of digitization, changing demand patterns and the fragmentation of value chains, there is a need to examine the value creation process across value chain networks operating in multiple locations. It is essential to gain a clear understanding of the key characteristics of digital platforms and how they generate value [3]. Conducting research in multiple locations is essential because different regions have diverse cultures, economies and social contexts that can impact the research topic differently. By comparing these areas, researchers can understand the factors influencing a phenomenon more comprehensively, leading to universally applicable conclusions [4].

The present research adds to our understanding of customer-to-customer (C2C) value co-creation by identifying where (platforms) and how (practices) fans create value with one another. Co-creation of fan value has been examined in relevant studies [5,6]. At this point in the academic investigation of the subject, theorizing and conceptualizing the relationships and constructs seem to be appropriate [7].

Previous research has indeed confirmed the role of digital platforms in facilitating collaborative value creation; there remains a relative scarcity of explanations regarding the specific factors involved and how participants derive value through collaborative efforts within the ecosystem [8,9,10]. From this perspective, this study aims to gain a deeper understanding of the service ecosystem of online talent shows, particularly focusing on the role of fan participation. This emphasizes the importance of collaboration, interactions and contributions from diverse individuals and groups. It underscores the crucial role of human connections in shaping and energizing digital platforms, highlighting the significant impact of participants with multiple roles in driving platform vitality [11]. It explores the following questions:

- (1)

- How are the service ecosystems of online talent shows created and operated in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan? How do members of these ecosystems derive value through collaborative creation?

- (2)

- What are the capabilities required to sustain the popularity of online talent shows?

- (3)

- How does the level of fan engagement impact online talent shows?

The next sections address the phenomenon of co-creation in multiple case studies and the innovation strategy adopted by the three enterprises in the face of competitors. Secondly, the specific characteristics of TV talent shows on digital platforms are explained to show how actors can experience and produce innovative TV talent shows to achieve co-creation on digital platforms. Thirdly, based on the relationship between the dynamic capabilities of organizations and the value creation of fans, specific suggestions can be provided for managers to distinguish themselves from other competitive platforms and expand their own value.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. SDL Service Ecosystem

Service ecosystems have become a key concept in S-D logic, providing an analytical organization for value co-creation activities in which participants combine resources and exchange services in a dynamic network [12]. Service ecosystem value creation includes co-integration and exchange support, creating shared value through service exchange [13]. The value of co-creation comes from experience of the organization’s services and interaction with other actors [14]. The resources invested by stakeholders in the service ecosystem include money, time, space, cognition, emotions, physical energy and even knowledge, collaboration and other stakeholders [15]. Through interaction, the actor’s resources are transformed into capabilities that are valuable to other actors forming interdependent relationships [16].

Value co-creation in service ecosystems enables participants to integrate resources into multiple dynamic interactions to jointly create value outcomes. The network enables two-way interactions between customers and service providers but also supports and enables value co-creation interactions between different participants in the network [17]. Thus, fan value co-creation activities cannot be fully supported by goods-dominant logic (GDL1); a service-dominant logic (SDL2) approach is needed [18].

Interactive platforms are composed of heterogeneous relations of artefacts, processes, interfaces and persons. Aided by digitalized technologies, interactive platforms afford a multiplicity of interactive system environments that connect creational interactions with how experienced outcomes emerge from their underlying resourced capabilities [19]. The process of constructing a somewhat elevated or bounded field as a relational intersection of different groups changes the way in which creation and diffusion are achieved [20]. Customers are digitally connected to the Internet of Materials through touchpoints, allowing for a seamless customer experience [21]. The foundation is to provide a platform for fans and other actors to co-create value that is logically compatible with the SDL [18]. Value co-creation, as the result of interaction, may be influenced by consumer participation. Participation and value co-creation improve the growth and profitability of organizations [22].

Service design activities can help companies to engage multiple stakeholders in a platform to motivate them to participate and share resources to enhance value creation [23]. The essence of a platform is to connect, interact and transact, and the essence of value co-creation is for stakeholders to interact through a platform to continuously co-create value [24]. The penetration of economic and infrastructural extensions of online platforms into the web affects the production, distribution and circulation of cultural content [25]. Many traditional cultural patterns are different from the previous ones under the reconstruction of digital and interactive video, attracting a large number of audiences and redefining the labor mode, income source and production rules of the cultural industry as well [26].

2.2. Value Co-Creation and Actor’s “Engagement”

The service-oriented logic, developed by Vargo and Lusch [27], is no longer just about the product itself, but the entire process from pre-purchase to post-purchase, emphasizing the importance of customer involvement and moving away from production to an emphasis on value co-creation. Grönroos and Voima [28] suggest three areas of value creation where companies are responsible for providing service processes (as design, development, manufacturing, delivery, back and front processes) and where active customers may provide input as co-developers or co-designers, or even as co-producers. These three areas include cognitive, emotional and behavioral aspects, with consumers’ cognitive, emotional and behavioral engagement driving consumers’ ongoing search behavior and purchase intentions [29]. Fan knowledge facilitates fan co-creation, which in turn leads to team identification. Additionally, fan engagement had a moderating effect on the mediating role of fan co-creation in the association between fan knowledge and team identification [30].

Value creation agrees that value is a joint function of the actions of the supplier and the customer and always results from co-creation [31]. McDonald et al.’s [32] work in sport organization found it to be the naturally strong interactivity between the various actors involved, such as fans, clubs, media and sponsors for engagement. Arguably, celebrity human brand identity co-creation is a social assemblage of a web of actors, both humans (i.e., celebrities, consumers, fans and other spectators) and “non-humans”, including organization and service entities (i.e., media outfits and commercial firms). Successful co-creation of human brands depends upon the translation of social interaction and participation. The actor–network theory provides a theoretical backdrop explaining how a social project such as a celebrity human brand identity is a collaboration of all actors, both human and non-human (i.e., organizations and businesses) [33]. Fan (value) co-creation refers to “the benefits realized from the integration of resources through interactions with other fans” [34].

The influence of pop culture has been reflected in the everyday life of society, and social media services have increased the interpretation of pop culture [35]). Zhao et al. [36] find that the effect of image richness on customer engagement is more pronounced for experience goods and posters with greater social influence. For companies, it is important to create experience value for consumers to increase interaction and enhance the willingness to buy a particular brand [37]. The literature explores the concept of value co-creation within value networks through digital platforms, emphasizing the varied approaches of different actors. While extensive research exists on Western multimedia platforms like YouTube, there is limited understanding of East Asian portals [38]. Social media platforms such as YouTube primarily aim to entertain users and promote social interaction, thereby increasing content appeal and user engagement [39]. This underscores the potential for films to enhance audience engagement through interactive experiences.

Service providers control the majority of the customer experience. Platforms must provide a unique customer experience in order to differentiate their brands in the marketplace [40]. An enterprise with strong dynamic capabilities will be able to profitably build and renew resources, assets and ordinary capabilities, reconfiguring them as needed to innovate and respond to (or bring about) changes in the market. The firm’s resources must be orchestrated astutely and coordinated with the activities of partner firms to deliver value to customers [41]. Brands (manufacturers) themselves attempt to engage directly with the end consumer. They are able to build powerful brand ecosystems that interact with consumers, create entirely new value propositions and make brands experiential [42].

2.3. TV Talent Shows Dynamic Capabilities

An enterprise with strong dynamic capabilities will be able to profitably build and renew resources, assets and ordinary capabilities, reconfiguring them as needed to innovate and respond to (or bring about) changes in the market. The firm’s resources must be orchestrated astutely and coordinated with the activities of partner firms to deliver value to customers [43]. Sensing and learning capabilities are essential to pursue proper digital transformation, and the entrepreneurs or the family owners drive these capabilities [44]. They are able to build powerful brand ecosystems that interact with consumers via IoT applications, direct selling, engagement and experience talent shows and personalized communication, which create entirely new value propositions and make brands experiential [42] The findings reveal that co-creation is considered a process of interaction and influencing between various participating parties. From a C2C standpoint, most studies on co-creation in branding are conducted in the context of social media. In these digital spaces, stakeholders may generate content [45]. Organizations endeavor to engage customers in the co-creation of new services and product development [46].

The value loops linking performers and fans have developed most rapidly within the idol industries of East Asia, due to the influence of J-pop, K-pop and the growth of social media platforms, and facilitated by investment in the digital economy and mobile communications [47]. Fans interact with organizations through online platforms, leading to a variety of active engagement activities, such as buying products and accessing and sharing information [48]. Platform-based business networks can connect users who are eager to interact and co-exist, enabling many previously non-interactive businesses to interact [49]. Social media provides an opportunity for fans to develop their identity, while also providing organizations with the opportunity to better understand fan motivations and strengthen fan relationships [50].

The current literature has pointed out the importance of creating an experience for customers and customers’ joint participation in creation. It is necessary to provide customers with a new brand experience in order to occupy a leading position in the market. This study facilitates a better understanding of the innovation strategy for TV talent shows in various locations. The essence of a platform is to connect, interact and transact, and the essence of value creation is for stakeholders to interact through the platform and continue to create value together [24]. We need more research to understand value creation in complex environments where customers co-create their experience by combining the service offerings of several companies in the customer value architecture [51].

3. Research Methods

3.1. Case Study

This study adopted a multiple case analysis approach, where case studies examine and understand current situations and practical phenomena in real-life settings, using multiple data collection methods to obtain information on one or more case entities (people, groups or organizations) [52]. Extensive and in-depth discussion and description of the problems of social phenomena were produced through multiple case studies [4]. An attempt was made to formulate a theory and conceptual framework to explain and understand new and emerging phenomena [53] This study has a “how” type of research question, and it was appropriate to adopt multiple cases as the method of research analysis [54]. Ozcan and Eisenhardt [55] suggest that case studies can be theoretically based on cross-case comparisons of multiple cases to identify possible relationships between cases, which not only makes the findings more convincing but also allows for generalization to the industry as a whole [56].

3.2. Case Selection

The idol economy has drawn attention from all over the world. Talent shows are a popular trend at the moment and cater to the emotional and spiritual needs of people in different places. They have been successful in various places by selecting around 100 participants and training them as idols over a period of about three months. Idol training TV shows have formed an industry. The emerging trend in television talent shows is now being discussed in academic studies and there are already comparative studies of talent shows from Korea and China, and Taiwan and China [57,58].

Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan are all well-developed countries in East Asia in terms of cultural transmission and share the same language system. Hong Kong’s TV stars have a higher international profile. Mainland China’s idols are able to generate the most economic value, while Taiwan is able to produce excellent TV dramas and films and collaborate with Netflix platforms to develop globally.

According to the network data, more than 20 talent shows are expected to be launched in Asia in 2021. With the emergence of new shows and the multilateral competition among original competitors, the shows in the three regions have changed in their content in comparison to the first season. Three case studies from mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan were selected for this research. The comparison of the three regions provided a more comprehensive insight that will be of great significance to the field of television talent shows and media.

3.3. Data Collection

In the paper, a total of 6 episodes of TV talent shows from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan were collected from the internet and selected as the research cases. The themes of the episodes were expressed in terms of platform establishment, value creation, dynamic capability and experience innovation. As for the method of analysis and discussion, the first episode of the first season and the first episode of the latest season were selected as the analysis units for the content analysis, so as to analyze the trend of the innovation strategies of TV talent shows in different places.

The main data were sourced based on primary and secondary data; content analysis and interviews were the main sources of the primary data, and secondary data were collected for official websites and internet news media. This study adopted a purposive sampling method. Purposive sampling is commonly used in qualitative research, where researchers select individuals with specific knowledge or experience relevant to the research objectives to provide information [59]. The principles of interviewee selection include: (1) key ecosystem participants, (2) individuals from different regions and (3) different actors in the ecosystem. A total of 9 interviewees were interviewed for this study, including 2 participants, 3 staff members, 1 cooperative platform staff member and 3 fan club representatives (Table 1). These participants encompassed various roles, enabling our research to gain in-depth insights into the talent show television program ecosystem. In order to ensure the soundness of the data analysis, the findings were discussed with the interviewees and corrected according to their opinions, in the process identifying and eliminating methodological flaws, data or surveyor bias [60].

Table 1.

Profile of respondents and dates of interviews.

The case study method involves linking, comparing and synthesizing data from multiple sources. These data sources are integrated with practical applications, leading to hypotheses and theories that are more viable [61]. Interviews are a process in which both interviewer and interviewee collaboratively establish understanding [62]. This approach aids in extensive and in-depth discussions and descriptions of social phenomena issues in case studies [4].

3.4. Data Analysis

This study is a qualitative study and adopted a grounded theory and case study in qualitative research, using cross-case analysis for a richer theoretical construction to discuss and describe the problems of social phenomena in a broad and in-depth manner [63,64]. It employed semi-structured interviews with participants and content analysis as a case study [65,66,67]. In addition to the outline of the interviews listed in Appendix A, we asked additional questions based on the positions and responses of the interviewees.

In terms of data analysis, this study adopted the method of content analysis and in-depth interviews. In the classification and coding section, two PhD students performed the content classification after viewing the shows. According to the method suggested by Graneheim et al. [66], this information was sorted into a table for subsequent content analysis.

Firstly, the content of the project based on the theoretical basis in three places was divided into four dimensions. The second-order code was established through interview collation. The last open code was the class that was repeatedly mentioned in the interviews in connection with the second-order code (Table 2).

Table 2.

Material categories.

After the classification was completed, the results of the data analysis were reviewed and the classified inconsistencies were communicated to determine the accuracy of the data through regular weekly interviews with experts. In the process of content analysis and classification, based on Krippendorff [65], as long as the contents can be related, they will be added to the count of the category. Cross-validation is conducted with 1 researcher; discussion is continued until a consensus is reached. This study used “intentional sampling” for the selection of interviewees. The respondents were coded as (A1–A9). Table 1 lists the categories of the respondents surveyed in this study.

4. Case Profile

4.1. Produce 101 China

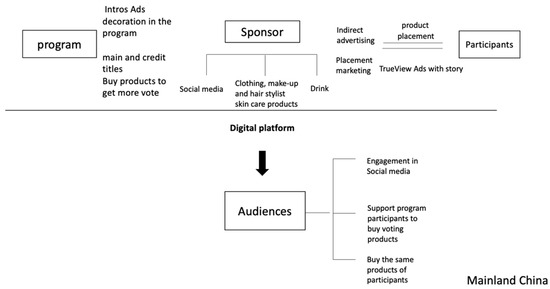

Produce 101 China is China’s first idol girl group reality show, produced by Tencent Video. The show includes a total of 101 participants from 43 companies. The talent show was officially licensed by Korea’s Produce 101 and was filmed over a period of four months (Figure 1). According to the analysis report of China’s variety show market, among the top 10 network variety shows in 2020, Produce 101 season three ranked second with 47.04. In addition, the top four were all talent shows. By the end of 2018, the playback volume of Produce 101 had reached 4.67 billion. At the same time, the number of super words read on Weibo, China’s largest social platform, had reached 15.81 billion. Based on the final online open OWHAT fundraising and Modian fundraising, the champion raised 12.852 million Yuan, and eight contestants raised more than one million Yuan.

Figure 1.

Talent show: a relational graph (mainland China).

4.2. Good Night Show—King Maker

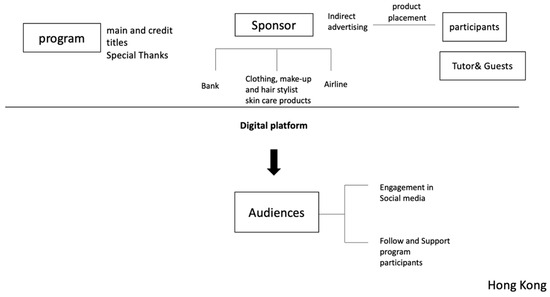

This is a talent show produced by VIU TV, in which 99 boys compete in different types of songs and dances, and the winner of the show wins HK$1,000,000. The talent show was never intended to be an idol group show, but only intended to sign contracts with the participants who won the championship. Finally, 12 participants were selected from the show to form a male idol group “MIRROR” (Figure 2). MIRROR has been involved in more than 180 brand campaigns on Instagram and nearly half of the top 10 brands with the highest advertising expenditure are promoted by MIRROR. MIRROR accounts for 70% of the advertising volume in Hong Kong. “MIRROR”, on 6 May 2021, held six consecutive concerts in Hong Kong, for which tickets were all sold out. One ticket was even sold at the price of HK$231,800. PCCW announced that VIU TV revenue rose 27 percent to 259 million Yuan by the end of 2019, representing an 11 percent increase in advertising revenue as viewing increased during the year.

Figure 2.

Talent show: a relational graph (Hong Kong).

4.3. Dancing Diamond 52

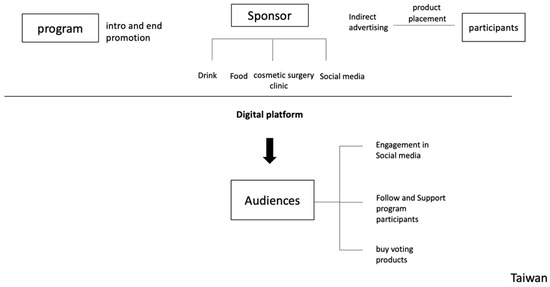

This is a 2020 Taiwan girls’ idol talent show. The 104 participants, mostly from Taiwan, were selected to form an eight-member girls’ idol group, and the contestants were voted on to form a popular group to debut (Figure 3). Since the fourth episode, Dancing Diamond 52 (DD52 for short) has been on PTT for eight consecutive weeks, producing prolonged and heated discussions. It won the “Best Elected Variety Show” award in the “2018 YAHOO! Search Popularity Award List—Popular Variety Show” and “Best variety show” in the 56th Golden Bell Awards (one of the major annual awards presented in Taiwan). The number of pre-orders for DD52 champion G.O.F.’s album topped the blogs and Eslite Bookstore within one week. In addition, 5000 tickets for the Start Taipei concert were sold out in just nine minutes.

Figure 3.

Talent show: a relational graph (Taiwan).

A comparison is conducted on the elements of talent show broadcast platforms, fans rating, click rate, etc. The talent show features of the three regions have been collated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of characteristics of individual enterprises.

5. Research Findings

5.1. Fans’ Participation and Value Creation

Talent shows attract customers to pay for them by providing additional services and the opportunity to obtain values beyond the talent shows, such as VIP extras and co-branded merchandise (Table 4). Fans can gain more voting rights through extra payment. There are a variety of voting channels to reach users of different platforms. Users can participate in the talent show interaction through the platform they are familiar with, thus having more chances to vote for their favorite contestants. In this way, digital platform partners strengthen traffic to digital platforms and increase media visibility because of the popularity of the shows. The management in mainland China will also use this resource sharing and realization for their own newly launched e-commerce app, using a low cost and high effectiveness strategy (A3). In addition, the fans need to participate in the multi-platform voting to provide more votes for the contestants. The fan groups interviewed are involved in all the voting platforms and they remind each other to vote. The DD52 voting facility was paired with a social platform, which helps the long-running participants on the platform. In the digital age, there is a greater opportunity for fans to participate in the experience and spend money on their products [68].

Table 4.

Forms of fan interaction.

Traditional TV channels have started to shift to online platforms in the past two years because of the advantages of time-free and repeatable viewing (A5). New digital platforms driven by shows and the existing digital platform can create more opportunities for participants and an untapped customer base. The type of collaboration is not limited to media-based platforms and the effects of collaboration have been shown to be beneficial in this research. However, Chinese TV channels still have a certain number of fans because they trust this method more. TV channels have more restrictions from the government than online platforms. Therefore, we can see that TV talent shows on digital platforms have more freedom and space for creativity, and the repeatable feature helps to increase fans’ stickiness.

5.2. Talent Show System and Process Create Differentiated Value

The new talent show process will give the contestants more opportunities to make their debut, creating a mutually beneficial effect. Continued innovation of the system will bring greater economic benefits (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of differences in the systems and processes of individual talent shows.

Among the three talent shows, Produce 101 began the earliest. It was licensed as a Korean show, using the Korean version’s basic process. Fans interact by participating in the talent show and voting, which lasts for three months and involves 101 contestants. Of these, 11 are selected to debut as a group for two years. Partners include 43 talent agencies and five judging tutors. In the first round, 11 candidates are selected in the form of a team or individual grading assessment. There are five levels, from A to F, and participants can progress through the competition by completing song and dance training, with special benefits for A-level participants.

Good Night Show only has six talent agencies and 99 contestants as participants. As well as selecting one group for singing/dancing, one comedy team of four participants is added. Elimination is conducted from the first round. To be specific, 50 contestants are eliminated in the first round, and 90 s of the time is given to each individual performance.

DD52 involves a total of 23 talent agencies and 104 contestants as participants over three months. By combining with the systems and processes of the other two places, it selects eight participants to become the champion team and the talent group through voting. The contract duration is 3~5 years. Furthermore, they provide training for the girls selected in the talent show who are not yet 18 years old. There are four tutors, a talent show assistant and a host. This creates the form of group competition. For each number, four contestants are selected, and half are eliminated. The ones who select the same number compete. Moreover, the team with the worst result in each episode needs to degrade his/her member to a joker. The joker mechanism gives the eliminated players a chance to continue to participate. Our interviewee revealed that the format and system of the second season are better than that of the first season and, therefore, the participants of the second season have gained more popularity. The opportunities offered by the talent show team have an impact on the economic value. With the experience of the first season and continuous innovation, the talent show has achieved even greater results in the following years.

5.3. Creating C2C Interaction

Tencent’s video platform has the function of community sharing and real-time pop-up. VIUTV has real-time discussions, AR interactive games and talent show lists on its mobile app, while DD52 adopts the functions of messages, likes and sharing on YouTube. Fans create groups on social media platforms because they like the same person or team. Businesses need the co-creation of their customers and benefit from customer-to-customer interaction [69]

The fans are attracted to the participants who continue to improve and those who are very strong singers or dancers. The talent showrunners also give more opportunities to unique participants; our interviewees were given the opportunity to perform because they were the oldest in the underage group, taller and good at dancing. The two participants we interviewed who were not featured in many talent shows, and who were not popular, still received more work and fan interest after the competition. In a TV show interview with the producer of DD52, he explained that it is important for a girl group to show team power in order to be successful, and to have good song and dance skills to stand out as an individual. The fan group responded that they could feel the emotion and growth part of the clip, but that they felt it was necessary and that the team selection needed to have a grind to make it grow. This is consistent with previous research, suggesting that fan engagement includes the components of fan-to-fan relationship, team-to-fan relationship and fan co-creation [34].

5.4. Bringing in Foreign Resources for Local Innovation

They have all added new aspects to the competition process. Produce 101, for example, has added links in the basic process, battle, challenge, filling and elsewhere. The elimination and re-animation mechanism of DD52 and Good Night Show were added. The mainland China runner develops content based on current trends, market demand, etc., and sometimes modifies the content to suit the personalities of the artists. DD52 provides 50 songs, all of which are original, including lyrics and music copyright, production and arrangement. The original song makes the participants feel that the song belongs to them and they are thus more involved in the performance. The talent show team can also release the album directly after the competition for quicker realization. Life sessions are considered important; when only filming the performance sessions, the fans did not know much about the participants, and their character and potential were not highlighted (A2). With these changes, the fans are able to empathize with the participants and grow with the talent show (A7).

Produce 101 has found this opportunity. Derivative shows have more planning in terms of contents, rather than in the form of talent show trivia, such as game reality shows, derivative shows and live broadcasts of contestants. In terms of derivative talent shows, Good Night Show adopts the form of derivative talent shows formed together with the contestants of previous seasons.

6. Discussion

Mainland China’s rapid economic development has led to a rise in people’s living standards, resulting in more spiritual and emotional needs. After years of internal turmoil and struggle in Hong Kong, local idol groups have emerged to give the people a place to live. The people of Taiwan are in pursuit of their own culture and love for their land, and there are currently no young idol groups in the Taiwanese music market. The emergence of idol groups has met the demand and become a part of young people’s lives (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of the heat creation methods of programs.

6.1. Digital Platforms and the Service Ecosystem

6.1.1. Talent Shows Are Developing as a Touch Point in the Social Sphere

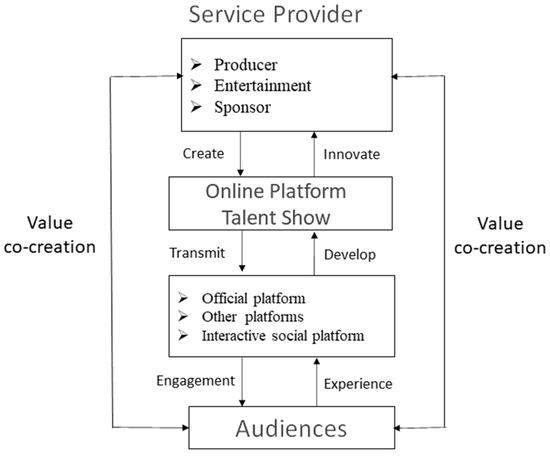

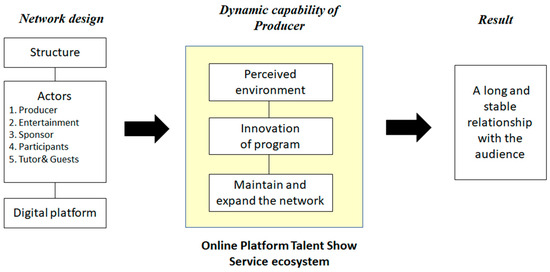

Talent shows provide a unique environment in which different actors interact, co-exist and co-create value, i.e., another form of O2O marketing. These actors include producers, entertainment companies, sponsors and fans, and fan value co-creation currently takes many different forms, which are experienced, engaged and interacted with through different platforms (Figure 4). With more and more fan participation, they have developed into a community. Through the network of talent shows, the fans and the platform, the fans and the sponsors and the fans and the fans have a new point of contact. Fans join the voting platform in order to vote and are reminded to vote regularly in the fan group. Consequently, collaboration with popular social media platforms maximizes the bilateral diversion effect, such as with DD52 and TikTok. Not only does this increase the impact of the talent show but it also facilitates greater fan participation. The platform extends the entertainment sphere of young people to the entire data chain of the social sphere through online behavior and the accessible interaction of users [70]. Specifically, fans have a special or unique nature that makes their engagement behavior more vivid and richer than other types of customers, as they are more passionate and loyal to their team than other types of customers are to any product/service [71].

Figure 4.

Relational graph of TV Talent shows.

6.1.2. Diversified Services Form a Digital Platform Ecosystem

This study found that the development of talent shows has seen a growing number of cross-platform participants, leading to a diversification of their services. Fans have access to e-commerce platforms to purchase celebrity and advertising products and receive further personalized services after membership registration. They can access personalized information to facilitate the ongoing promotion of the show. The firm’s resources must be orchestrated astutely and coordinated with the activities of partner firms to deliver value to customers [43], branding (manufacturers) themselves in an attempt to engage directly with the end consumer. They are able to build powerful brand ecosystems that interact with consumers via IoT applications, direct selling, engagement and experience talent shows and personalized communication, which create entirely new value propositions and make brands experiential [42]. Accordingly, this study proposes the following proposition:

Proposition 1.

If the TV talent shows can be developed into an integrated service ecosystem, the benefit of fans will be maximized.

6.2. Value Co-Creation and Engagement

6.2.1. Partners in Different Countries and Sectors Complement and Enhance Value

Both Produce 101 and Good Night Show in this case study innovate the fan experience by using new partnerships (Table 7). Produce 101 increases the number of overseas contestants and allows management and overseas agencies to share the value of the show. The management finds a new positioning in the highly competitive environment of talent shows, and overseas agencies introduce contestants to the mainland Chinese market through the talent show. In its first season, Good Night Show implemented a cross-disciplinary panel of judges, allowing the fans of well-known partners in the field to follow and even interact with the show. Cross-disciplinary judges can enhance the popularity of TV talent shows. According to the study, foreign talent is an important factor in attracting viewers, but in Chinese shows, there is a general bias toward local talent and hidden restrictions on the number of debutants from China and foreign countries, which affects the fairness of the competition. The results of talent shows are seemingly fan-driven but are actually controlled by the talent show team. TV talent shows provide a platform for manufacturers to promote their products at a lower cost. The sponsors conduct indirect publicity and direct publicity in the talent show. The mainland China and Taiwan shows are the main sponsors of drinks; the main reason is that these companies are large in volume and the lower prices of individual products are more acceptable to fans. The Hong Kong and Taiwan shows appeared in advertisements for banks, airlines, medical beauty clinics and houses; these are high-priced products, but they still have a good advertising effect.

Table 7.

Value connotation and participants.

6.2.2. The Influence of Talent Show Planning on Enhancing Fans Interaction

In the talent shows from the three locations, contestants’ personal interview footage of themselves and other contestants’ performance and personal family and experiences are presented. Fans are keen to participate in group activities to build emotional bonding with their idols [72]. Management constantly adds more derivative shows to the mix that showcase the contestants’ personalities, perhaps as a form of interaction with the fans. We found a significant positive impact of interactive participation on cross-interactive customer co-creation. The impact of fan active participation goes beyond the interaction itself. As customers understand specific products or services, they are usually able to more effectively integrate resources to achieve product/service-related goals, and their knowledge sharing ability also improves [30]. This is similar to the findings of Pandita and Vapiwala’s [5] study on fans, which shows that organizations can effectively leverage fan engagement and experience through reward incentives and enrichment of the fan experience.

Fans are interested in what the participants can do beyond the performance, and they are happy to grow with them and pay for it. While the personality and individuality of the participants are the keys to gaining the support of the fans, this finding echoes that fan engagement creates benefits in fan resource development and fan value co-creation [6]

6.2.3. Data Ranking Will Serve as an Incentive

Fans are motivated to engage with organizations on social media for information, empowerment through influencing other consumers, social interaction, passion and emotional attachment [73] The emotional connection between fans and their chosen object allows for the demonstration of deep knowledge and exceptional expertise about the object [74]. The management gives the fans the right to make their own choices and encourages the fans to constantly interact with the platform. The final result depends on the efforts of the fans themselves. Interviewees’ perceptions of Chinese talent shows would have a large number of fans voting sessions and a greater sense of interaction with the fans during the process.

Rankings are the key to attracting fans, and they temporarily determine how to motivate fans to participate and profit from them [75]. Accordingly, this study presents the following proposition:

Proposition 2.

A more intimate relationship with the fans would generate loyalty.

6.3. TV Talent Show Dynamic Capabilities

6.3.1. The Dynamic Capability of the Organization Affects the Market Share of the Talent Show

Tencent was the first company to import South Korean shows and has become the industry leader by pioneering new formats. Their talent show will also be the first to develop foreign talent to join the competition and gain more attention (A4).

According to the network data, more than 20 talent shows are expected to be launched in East Asia in 2021. With the emergence of new shows and the multilateral competition among original competitors, the shows in the three regions have changed in their contents in comparison to the first season. Most fans are very engaged and, for many, the shows play an important role in their everyday lives [76].

Due to the popularity of social media, organizations increasingly invest significant time and resources to drive online engagement, leveraging the highly involved nature of their fans [77]. The study found that innovations in the talent show would attract more strong participants and gain more attention, with all three regions gaining more visibility and attention in the new season. Management needs to keep innovating in order to maintain customer engagement in a highly competitive market [78]. Top management plays a vital role in improving the ability for sustainable development of enterprises. Top management invests heavily in diversification to support business sustainability [79].

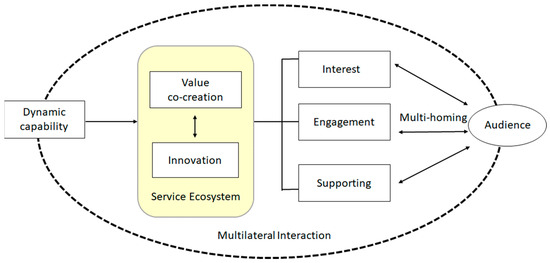

The talent shows in all three places have undergone a process of experiential innovation to maintain their existing audiences and expand their audience base. Global accessibility through digital platforms has increased the number of “products” to “audiences” (Figure 5). Thus, dynamic capabilities include the sensing, capture and transformation needed to design and implement business models. The management designs and implements the sensing, capture and transformation required by the talent show based on the environment and fan preferences, which confirms the viewpoints of Petricevic et al. [41].

Figure 5.

Dynamic Capability Value Network.

6.3.2. Multilateral Effects Spread by the Fan’s Voluntary Behavior

A group of fans who share the same interests through a digital platform put a lot of effort into voting and developing other ways of giving back economically, such as fundraising, development and sales of related products and cooperation with physical shops. They produce a wide range of products such as red packets, spring scrolls, folders, posters, mirrors, postcards, etc., depending on the participants’ current work. They also set up different groups by region, such as a fan group in Taiwan for a Hong Kong talent show, and they exchange resources with each other. This is multi-point connectivity and multilateral communication through digital platforms. This is common with the characteristics of digital platforms found by Biagioli [20], Kotler [21] and Van Alstyne et al. [24], and the multi-lateral effects of participants’ expanded actions through digital platforms found in this study are of interest. Accordingly, this study presents the following proposition:

Proposition 3.

The follow-up behavior of the fans through digital platforms will extend the values, including resource creation and resource integration.

The dynamic capabilities of management will have an impact on co-creation and innovation. As a vehicle for communication, TV talent shows form an ecosystem by linking actors through digital platforms. The co-creation of these participants generates innovation, fan interest, continuous participation and support for spontaneity, generating multiple economic effects including online support and down-line collaborative promotion, thus extending the effect (Figure 6). Fans gain additional knowledge and skills through interaction with the show and use them; the application of skills and knowledge occurs both at the live venue and on other platforms. They will form groups on social media to share information about the voting on different platforms and produce their own support products. This promotes the industrialization of culture and creativity, the creation of cultural elements and the sharing of resources to other industries, increasing the possibilities of promotion. The cultural significance of an idol’s image is transferred to the products endorsed fans’ admiration for their idols, making them unconsciously glorify everything associated with them and love the brands and products associated with them [72]. The introduction, sharing and engagement with the knowledge and expertise further contribute to the social connection and capitalization between fans and the fan communities [6]).

Figure 6.

Digital platform ecosystem for a talent show.

7. Conclusions

Watching talent shows on online platforms, especially through participation in multi-platform interaction, is an ever developing and innovative field in many regions. However, there has been a lack of theoretical basis and multi-site research results to analyze value co-creation and dynamic capabilities. In this paper, we analyze and compare three cases from aspects of value co-creation, digital platform and dynamic capability, through an exploration of a series of creative activities on digital video platforms. The findings can contribute to examining the underlying dynamics of TV talent shows and explain how achieving sustainable advantages in the media market can be achieved. Our research extends the scope of the study to include concepts of online, offline and traditional TV management, such as online multi-platform integration and more integrated theoretical applications.

The main findings of this study are the following: Ways to gain an advantage from talent show production, including innovative processes to attract strong and recognizable participants. Quick realizations can be achieved by taking advantage of the popularity of the show to launch the product quickly and by having access to the songs and contestants. Life and growth sessions can help the contestants to express their personalities and thus attract more fan participation, and the design of the sessions can help sponsors to better express their products. Voting platforms are a cost-effective way of working together and can act as a bilateral traffic magnet. Joining multinational or cross-sector partners is identified as a new strategy that can outperform local and foreign competitors and sustainably gain market share in a competitive environment through dynamic capabilities. A co-creation relationship between continuous innovation and enhanced fan value is also identified. Therefore, our research can help to promote the research on this new form of digital content service and its innovation strategies.

The findings of the study revealed that the fans of the talent shows are actively engaged in subsequent consumption behavior and expanding the show’s reach to new fans, which is an interesting phenomenon that can be addressed in subsequent studies.

7.1. Theoretical Implications

This study further understands the service ecosystem of network talent shows from the perspective of an industrial innovation strategy. Previous related studies have confirmed that digital platforms are conducive to value co-creation [44,76,80], but there are relatively few explanations for specific factors.

Currently, the network performance talent shows are mainly analyzed using the content analysis method. When it comes the main contributions of this study, from the perspectives of industry innovation strategy, ecosystem services and dynamic capability, it points out the innovation strategy of online show talent shows in many locations, as well as management’s dynamic capabilities in the digital platform environment, and their impact on fan participation. In particular, TV talent shows are a new hot spot that has emerged in the past two years. As far as we know, this is the first attempt to conduct comparative analysis on the digital platforms in three regions.

The research results are summarized in Figure 6. Previous studies on service ecosystems and value co-creation all focus on the driving factors. By comparison, this study analyzes the application scope of the service ecosystem from the perspective of the actor role of the service ecosystem. Rather than being limited to talent shows on online platforms, our analysis extends to digital platforms and value networks, such as the relationship between value co-creators, and increasing interaction through multiple digital platforms.

Furthermore, this study also makes a contribution to the related research on dynamic capabilities. In particular, for planners, it is determined that dynamic capabilities are quite significant to the value of talent shows. Through these capabilities, the management can effectively design and plan talent shows on the network platform, and then integrate and coordinate network value links to create value for participants. According to the research results, the talent shows on the three network platforms have established network value links on the digital platform, and their interactive functions and social media can help to enhance the value co-creation of the fans and generate more network links, thus creating a closer relationship with fans. Taking into account the different contexts in which platformization is studied and the accompanying creative video commercialization in non-Western contexts, such as China, can also help us to go beyond the Western normative theories that have been posited in this field [81].

Sugihartati et al. [68] discuss the influence of fans’ participation in the digital era.

This study specifically discusses the methods of fan participation and the factors that can increase participation. For instance, in this study, the fans in the three locations enter the link of value creation through voting. Setting different voting rights on different platforms is a way to enhance value creation. Therefore, innovation mechanisms can help to discover platform services and expand platform value [79]. In our opinion, against the background of online platforms of talent shows, value creation is mainly driven by the fans’ interactions, and produces influence through the other star participants and sponsors’ resources. The management needs to create experience value for consumers, and it is very important to increase the consumers’ interaction and willingness to buy a specific brand [37]. We have contributed to the discussion of the service ecosystem by bringing “producers” into it. “Producer” is a word often used to describe a service provider [82,83]. We discuss the actor’s role in order to study service ecosystems and understand how service ecosystems are created and operate, and examine co-creation among ecosystem members by using network values and dynamic capabilities. He et al. [84] explored the social and psychological motives driving online data production among Chinese fans, focusing on collective action. They found that fan communities on social media blend social psychology and data production. This study further illuminated the collaborative benefits generated by such behaviors.

7.2. Managerial Implications

This research is of great management significance. With mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan representing the analysis background, and based on the content analysis of talent shows on three network platforms, it can be seen that talent shows on network platforms mainly use digital platforms to create value co-creation. In particular, the management’s connection to different platforms helps to enhance the fans’ participation and attract more new participants, which can work hand-in-hand to make culturally marked phenomena accessible to the international target [85].

The findings of the case study illustrate the importance of fans’ continuous participation for the management of network talent shows to maintain competitive advantages. These cases of TV talent shows in three places show that the management can maintain the sustainability of shows by innovating against other new shows of the same type. Hence, the insights from the perspectives of dynamic capability and value network can help management to consider these aspects when developing innovative strategies. To increase customers’ active participation in value co- creation, such as feedback and tolerance, they need to provide innovative strategies [86]. The cases in this study started to look for market gaps from their first season and changed their positioning and planning with the changing environment. Obviously, the dynamic ability of the management has a very significant influence on the talent show’s contents. In the environment of digital platforms, the management needs to effectively respond to the rapidly changing market, as can be seen from the actions currently being taken in China to manage the fan behavior of idol shows; other countries can limit fan excesses through process changes.

The Chinese mainland program’s production should engage in more collaborations with international actors to mitigate the challenges imposed by policies. The previous seasons of the program have already garnered audiences from both domestic and international regions. Therefore, designing program services tailored to overseas viewers would be a promising direction for development. Diverse experiments in participant selection in the Hong Kong’s programs have been well-received by the audience, especially the latest mixed-gender format. Hong Kong program viewers are primarily local, so a localized design that caters to the preferences of Hong Kong viewers may increase audience engagement. The Taiwan show has gained a lot of audience support during its latest season; how to maintain the success of the debutantes and how to design the new season are the main issues, and they should maybe consider letting the popular contestants continue to participate in the new season to bring about a continuity effect.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study explores the innovation strategies of network talent shows in three places through multiple case study methods. There were limitations to data collection due to objective factors such as time and research environment. The sample size and number of interviewees can be increased for more in-depth studies in the future. As more and more network talent shows emerge, there may be greater innovation in the future, which is worthy of further verification and research. Now, it is difficult to imagine an informed conversation about the global media or about world cinema that will not turn to East Asia. East Asia is, after all, a massive and vibrant element of the world we share [87].

In the future, quantitative research can be conducted to cross-verify the survey of consumers in the three countries using the qualitative research content analysis method of this research. From the aspect of globalization, the results from these three places may not be generalized and can be verified by more studies in different places. However, the model proposed in this study can be used as an empirical research basis to consider the relationship between management and fans’ value co-creation. The ongoing changes in talent show systems in different countries include the influence of policies, social events and ethical issues of the contestants, which will have a significant impact on the subsequent effects generated by the talent shows, and therefore the findings of this study can be carried forward for ongoing research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-K.N. and C.-L.C.; data curation, W.-K.N. and C.-L.C.; methodology, W.-K.N. and C.-L.C.; project administration, C.-M.Y. and C.-L.C.; writing review and editing, C.-M.Y. and C.-L.C.; writing—original draft, W.-K.N.; funding acquisition, investigation and supervision, W.-K.N. and C.-M.Y.; formal analysis, W.-K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Outline of interviews with TV producers

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Outline of interviews with cooperative platform staff

|

|

|

|

Outline of interviews with participants

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Outline of interviews with fan club

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. News Narration, Local Visibility and Public Life in Chinese Short Videos. J. Pract. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.; Lotz, A.D. Television Studies, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- de Reuver, M.; Sørensen, C.; Basole, R.C. The Digital Platform: A Research Agenda. J. Inf. Technol. 2018, 33, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pandita, D.; Vapiwala, F. Waving the flames of fan engagement: Strategies for coping with the digital transformation in sports organizations. J. Strategy Manag. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huettermann, M.; Uhrich, S.; Koenigstorfer, J. Components and Outcomes of Fan Engagement in Team Sports: The Perspective of Managers and Fans. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2022, 7, 447–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Harwood, T.; Bogicevic, V.; Viglia, G.; Beldona, S.; Hofacker, C. Technological disruptions in services: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-Y.; Lo, R.-A. Factors Affecting Customers’ Purchase Intentions in Live Streaming Shopping. J. Manag. Decis. Sci. 2020, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.; Kroschke, M.; Schmitt, B.; Kraume, K.; Shankar, V. Transforming the Customer Experience through New Technologies. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 51, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, J.-H.; Li, Q. What drives consumer shopping behavior in live streaming commerce? J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 21, 144–167. [Google Scholar]

- Heyder, T.; Passlack, N.; Posegga, O. Ethical management of human-AI interaction: Theory development review. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VVargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic 2025. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2017, 34, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, I.C.L.; Vargo, S.L. Service-dominant logic, service ecosystems and institutions: An editorial. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 29, 518–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmefalk, M.; Palmquist, A.; Rosenlund, J. Understanding the mechanisms of household and stakeholder engagement in a recycling ecosystem: The SDL perspective. Waste Manag. 2023, 160, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, D.; Redwood, M. Making sense of network dynamics through network pictures: A longitudinal case study. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2005, 34, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirão, G.; Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P. Value cocreation in service ecosystems. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyperas, D.; Maglaras, G.; Sparks, L. Sport fans’ roles in value co-creation. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 19, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V.; Ozcan, K. What is co-creation? An interactional creation framework and its implications for value creation. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Biagioli, M.; Sunder, M. Academic Brands; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Kartajaya, H.; Setiawan, I. Marketing 5.0: Technology for Humanity; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Islam, J.U. Tourism-based customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 39, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, A.; Blažević, V. A service design perspective on the stakeholder engagement journey during B2B innovation: Challenges and future research agenda. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 95, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alstyne, M.W.; Parker, G.G.; Choudary, S.P. Pipelines, platforms, and the new rules of strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 94, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nieborg, D.B.; Poell, T. The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 4275–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Infrastructuralization of Tik Tok: Transformation, power relationships, and platformization of video entertainment in China. Media Cult. Soc. 2021, 43, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C.; Voima, P. Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J.; Leung, W.K.S.; Salehhuddin Sharipudin, M.-N. The role of consumer-consumer interaction and consumer-brand interaction in driving consumer-brand engagement and behavioral intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnam, M.; Dickson, G.; Delshab, V.; Gerke, A.; Savari Nikou, P. The moderating effect of fan engagement on the relationship between fan knowledge and fan co-creation in social media. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2023, 24, 606–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.; Vargo, S.; Tanniru, M. Service, Value Networks and Learning. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 38, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, H.; Biscaia, R.; Yoshida, M.; Conduit, J.; Doyle, J.P. Customer Engagement in Sport: An Updated Review and Research Agenda. J. Sport Manag. 2022, 36, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, D.; Wang, J.J. Celebrities as human brands: An inquiry on stakeholder-actor co-creation of brand identities. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 74, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.O.; Correia, A.; Biscaia, R.; Pegoraro, A. Examining fan engagement through social networking sites. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2019, 20, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steve Fong, C.C. Strategic management accounting of social networking site service company in China. J. Technol. Manag. China 2011, 6, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, M.; Ming, Y.; Niu, T.; Wang, Y. The effect of image richness on customer engagement: Evidence from Sina Weibo. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J.; Smith, A.N. Augmented reality: Designing immersive experiences that maximize consumer engagement. Bus. Horizons 2016, 59, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.T.; Cassany, D. The ‘danmu’ phenomenon and media participation: Intercultural understanding and language learning through ‘The Ministry of Time’. Comunicar 2019, 58, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHasan, A.J.M.S. The Power of YouTube Videos for Surgical Journals. Surgery 2023, 174, 744–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Richthofen, G.; von Wangenheim, F. Managing service providers in the sharing economy: Insights from Airbnb’s host management. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petricevic, O.; Teece, D.J. The structural reshaping of globalization: Implications for strategic sectors, profiting from innovation, and the multinational enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 1487–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.; Wiegand, N.; Imschloss, M. The impact of digital transformation on the retailing value chain. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: Enabling technologies, standards, and licensing models in the wireless world. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1367–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, M.; Penco, L.; Profumo, G.; Quaglia, R. Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvuo, S.; Rindell, A.; Kovalchuk, M. Toward a conceptual understanding of co-creation in branding. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 139, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.R.; Read, S. Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 290–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Negus, K. East Asian pop music idol production and the emergence of data fandom in China. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2020, 23, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.; Ahn, K.; Kim, M. Building brand loyalty through managing brand community commitment. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1194–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, D.P.; Srinivasan, A. Networks, platforms, and strategy: Emerging views and next steps. Strat. Manag. J. 2016, 38, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StStavros, C.; Meng, M.D.; Westberg, K.; Farrelly, F. Understanding fan motivation for interacting on social media. Sport Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P.; Cunha, J.F.; Constantine, L. Multilevel Service Design: From Customer Value Constellation to Service Experience Blueprinting. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbasat, I.; Goldstein, D.K.; Mead, M. The Case Research Strategy in Studies of Information Systems. MIS Q. 1987, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, H.-G. The theory contribution of case study research designs. Bus. Res. 2017, 10, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan, P.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Origin of Alliance Portfolios: Entrepreneurs, Network Strategies, and Firm Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 246–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herriott, R.E.; Firestone, W.A. Multisite Qualitative Policy Research: Optimizing Description and Generalizability. Educ. Res. 1983, 12, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, Y.O. The Influence of Mainland China’s Cultural Soft Power on Taiwan’s Political Security: A Case Study on Idol Survival Variety Programmes; Nanyang Technological University: Nanyang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Chung, N. The impact of customers’ prior online experience on future hotel usage behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Triangulation—A methodological discussion. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, E.G. Research Interviewing: Context and Narrative; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990; p. 532. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, C. Processes of a case study methodology for postgraduate research in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 1998, 32, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; p. 472. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.-M.; Lundman, B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 56, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugihartati, R.; Suyanto, B.; Sirry, M. The Shift from Consumers to Prosumers: Susceptibility of Young Adults to Radicalization. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-S.; Kerr, D.; Chou, C.Y.; Ang, C. Business co-creation for service innovation in the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1522–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gerlowski, D.; Acs, Z. Working from home: Small business performance and the COVID-19 pandemic. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 58, 611–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, D.; Elsharnouby, M.H.; AbouAish, E. Fans behave as buyers? Assimilate fan-based and team-based drivers of fan engagement. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Li, T.; Chen, R.; Yang, K.; Li, P.; Wen, S. Converting idol worship into destination loyalty: A study of “idol pilgrimage tour” in China. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Rowley, J.; Keegan, B.J. Social media marketing strategy in English football clubs. Soccer Soc. 2022, 23, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.; Guo, Y. Ubiquitous Love or Not? Animal Welfare and Animal-Informed Consent in Giant Panda Tourism. Animals 2023, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Fu, P. Love your idol in a ‘cleaned’ way: Fans, fundraising platform, and fandom governance in China. Media Int. Aust. 2022, 185, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrer, J.A.; Woratschek, H.; Brodie, R.J. A systemic logic for platform business models. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 29, 546–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L.; Fernandes, T. Social media and sports: Driving fan engagement with football clubs on Facebook. J. Strateg. Mark. 2018, 26, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.; Kim, S.J.; Wang, H. Understanding the role of service innovation behavior on business customer performance and loyalty. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, M.; Sjödin, D.; Parida, V. Co-evolution of platform architecture, platform services, and platform governance: Expanding the platform value of industrial digital platforms. Technovation 2021, 118, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, F.; Mancini, D.; Leone, D.; Lavorato, D. Digital business models and ridesharing for value co-creation in healthcare: A multi-stakeholder ecosystem analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z. Commercialization of Creative Videos in China in the Digital Platform Age. Telev. New Media 2020, 22, 152747642095358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, S. Donald Trump, the Reality Show: Populism as Performance and Spectacle Donald Trump, die Reality-Show: Populismusals Performanz und Schauspiel. Z. Lit. Linguist. 2020, 50, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D. An(un)romantic journey: Authentic performance in a Chinese dating show. Glob. Media China 2020, 5, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Li, Y. Civic Engagement Intention and the Data-Driven Fan Community: Investigating the Motivation behind Chinese Fans’ Online Data-Making Behavior from a Collective Action Perspective. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 9, 20563051221150409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locher, M.A.; Messerli, T.C. Translating the other: Communal TV watching of Korean TV drama. J. Pragmat. 2020, 170, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L.; Bosselman, R. Customer Perceptions of Innovativeness: An Accelerator for Value Co-Creation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 807–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorfinkel, L. Chinese Television and National Identity Construction: The Cultural Politics of Music-Entertainment Talent Showmes, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).