Abstract

“Tourism for all” is based on three main aspects: accessible tourism, sustainable tourism and social tourism. Accessibility is an essential part of responsible and sustainable tourism. A sizable segment of the population comprises people who have a type of disability or people who are older and, as a result of age, experience diminished physical and/or mental abilities. The aim of this study is to analyze whether the mobile applications and websites of Portuguese and Spanish Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) are accessible. For this purpose, accessible destinations listed by the Tur4all project were taken as a sample for a quantitative exploratory study. Several tools related to accessibility were used to determine their level of compliance with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. The results reveal that the percentage of non-compliance with accessibility criteria is very high in DMOs in Portugal and especially in Spain. In conclusion, tourism for all is important, including its digital tools. The practical implications include guidance on accessibility for institutions and companies, as well as a need to raise awareness of its importance in the tourism sector. This is the only study that analyzes the accessibility of both apps and websites of the same institution according to the requirements in WCAG 2.1.

1. Introduction

According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), “Accessibility for all to tourism facilities, products, and services should be a central part of any responsible and sustainable tourism policy. Accessibility is not only about human rights. It is a business opportunity for destinations and companies to embrace all visitors and enhance their revenues” [1]. Accessibility to tourism is therefore an international concept that is reflected in the different policies of each country.

The World Tourism Organization also highlights three aspects that characterize the concept of tourism for all: “(1) Accessible tourism: it guarantees the use and enjoyment of tourism irrespective of the capabilities, status or condition of people; (2) Sustainable tourism: it is involved in the protection of environmental and cultural resources and the wellbeing of communities; (3) Social tourism: it aims to guarantee access to tourism to people with low income, families, seniors, or people with disabilities” [2] (p. 24). Thus, “Tourism for all” takes on a special importance for public and private companies within the tourism sector.

In addition, the equal status of all persons with disabilities is recognized in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) based on human rights and fundamental freedoms [3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) [4], at the international level, 15% of the world population is estimated to have one or more disabilities. Therefore, people with disabilities represent a significant segment of the tourism market because, according to the European Commission [5], it is a multi-client segment (they usually travel with a companion) that provides opportunities to promote off-season travel and improve the company’s reputation.

Previous research related to accessibility and tourism includes studies based on the importance of this segment within the tourism sector market [6,7,8,9], as well as those focused on the digital analysis of websites or apps in the tourism sector [10,11,12]. However, no studies were found that evaluated both the apps and websites of the same institution or company, whether public or private. Moreover, from the perspective of digital accessibility, two studies in sectors related to tourism stand out in particular: The first is on the accessibility of India’s e-governance mobile apps [13], and the second is on air quality monitoring apps (focused on clean air) [14], but both are based on the analysis of mobile accessibility through the implementation of Google’s Accessibility Scanner tool.

The Internet plays an important function in the tourism sector: it is used to search for and purchase services related to the travels of individuals. If web pages or consultation apps do not meet the minimum criteria established for digital accessibility, seniors and people with disabilities may be excluded, creating a digital barrier for this segment of the population [2]. The older population is an important group of people who benefit from web accessibility as their skills decline as a result of age [15].

As illustrated above, accessibility is an essential part of responsible and sustainable tourism. Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) create and promote a brand image to influence tourists by generating the idea that their destination is one of the best options to visit [16,17]. With the advancement of the Internet, websites and applications are also becoming more important as a source of tourist information [18,19,20] that DMOs should take into account as part of their branding strategy and informational content. For this reason, this study analyzes a sample from the project Tur4all.com [21], an important organization promoted in Portugal and Spain (two of the main tourist destinations in Europe) [22], where the offer of accessible tourism applies to both destinations. For this purpose, the official digital tools that are represented as accessible for destinations in both countries on the Tur4all platform are analyzed to determine their level of compliance with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1, established by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) [23]. Based on available studies [10,11,12,13,14], this analysis of Portuguese and Spanish DMOs’ accessibility apps and websites is a crucial contribution because both forms of media for an institution or company have never been analyzed at the same time. Analyzing both aspects leads to more reliable conclusions about their compliance with respect to digital accessibility.

This research is structured in the following sections: First, an introduction is presented with a theoretical framework of accessible tourism and web pages and the accessibility of mobile applications. A quantitative methodology was used by applying two tools to measure WCAG 2.1 accessibility. The results obtained from each digital medium are compared. In the discussion section, we examine the results with other studies based on similar analysis methodologies. Finally, in the conclusion, limitations and future research lines are also described.

2. Theorical Framework

2.1. Accessible Tourism

Accessible tourism is an important concept at the international level that has markedly evolved in recent years. According to the World Tourism Organization, “Accessibility is a central element of any responsible and sustainable tourism policy. It is both a human rights imperative and an exceptional business opportunity” [2] (p. 19). Moreover, tourism does not only benefit persons with disabilities or special needs; it benefits us all [2].

This concept has evolved towards quality tourism for all rather than accommodation for people with disabilities with a focus on tourism [2]. According to Buhalis and Darcy [24], accessible tourism means that people who have some type of limitation, such as those in the mobility, vision, hearing and cognitive access dimensions, have the same opportunities as the rest of the population to enjoy everything that a destination offers. Therefore, a city that adapts to “Tourism for all” benefits all involved groups, both tourists and the citizens who live in that destination. For example, people with vision problems comprise one of the most neglected groups of tourists with disabilities [25]. A tourism policy for all represents an innovative response to the challenges of social exclusion and inequality while improving the economy of the tourism sector through job creation and regional development [26].

The Organization of Social Tourism (ISTO) was created in 1963 with the aim of promoting the development of social tourism at the international level. For ISTO and the social tourism sector, tourism for all is an ongoing priority. They define “Tourism for all” as the inclusion of the largest possible number of people in leisure and tourism services. The most important segment for a social tourism policy comprises young people, families, senior citizens and persons with a disability [27]. However, in the welfare state of European countries, government policies need to take into account not only social tourism but also additional proposals that allow other people to travel for tourism purposes by overcoming their economic difficulties or lack of free time [28].

Moreover, data from the European Union Tourism Trends indicate that tourism contributes 10% of the GDP [22]. The World Tourism Organization, in collaboration with the ONCE Foundation (Spanish National Organization of the Blind) for Cooperation and Social Integration of Persons with Disabilities and the European Network for Accessible Tourism (ENAT), developed a manual that highlights the importance of the principles, tools and best practices of accessible tourism for all [2].

In the European context, 14% of the total population between the ages of 15 and 64 has some type of disability [29]. At the international level, the growth rate of the total number of people with special needs exceeds the population growth; these data are mainly due to the aging of a relatively large proportion of the European population, as well as a global increase in chronic health problems associated with disabilities [30]. Taking into account that Portugal and Spain are two of the main tourist destinations in Europe [22], the following research question is posed for the analysis of digital accessibility:

RQ1: Which country best meets the accessibility digital criteria?

Among the studies that have been carried out on accessibility, several investigations have focused on the importance of this segment for the tourism sector [6,7,8,9]. Research related to accessible tourism has concluded that despite policies that intend to meet the requirements of accessible tourism in different countries, greater awareness is needed so that more effective measures are implemented in different destinations.

2.2. Mobile App and Website Accessibility

Internet consumption has increased considerably in recent years: around 60% of the world’s population is already online. At the beginning of 2020, the number of people who were using the Internet exceeded 4.5 billion [18]. In January 2020, Internet penetration in Spain and Portugal stood at 91% and 83%, respectively, with 42.40 million Internet users in Spain and 8.52 million in Portugal. Between 2019 and 2020, the number of Internet users increased by around 4.3% in Spain and by 3.0% in Portugal [19,20].

According to data from October 2020, Android devices led the global market share with respect to other mobile devices, such as iOS, at 72.92% [31]. Of the countries examined in this study, the data indicate that Android device usage was higher in Spain than that in Portugal in October 2020, at 78.45% and 73.27%, respectively [32,33]. On a global level, the market share of Desktop vs. Mobile vs. Tablet is 48.88%, 48.62% and 2.5%, respectively. If the percentages of Mobile and Tablet are combined, they constitute 51.12% of the market share vs. Desktop. Therefore, it can be deduced that the share of mobile devices is equal to and even surpasses the participation of the desktop market [34]. Continuing with the data for the month of October 2020, in Portugal, the Desktop vs. Mobile vs. Tablet data are 71.36%, 26.91% and 1.73%, respectively. However, in Spain, these values are 54.73%, 42.78% and 2.48%, respectively [35,36]. The data for Portugal differ more from the global statistics than those for Spain, but both countries follow the same trend in which the use of mobile phones and tablets increases over time.

It is important to highlight that from the point of view of the user, both accessibility and usability are integral in the browsing process, as well as factors and attributes that directly influence the user experience of e-tourism websites [37]. The Internet is a medium that many users employ to plan a trip, but if a web or mobile application is not accessible, both seniors and people who have some type of disability are excluded from enjoying the advantages of tourist consultation and reservations. It is important to highlight the barriers that usually occur in the digital field: the information is incorrect, lacking detail, outdated, inaccessible and not adapted to all types of users [2].

Given that Internet penetration facilitates access to information and increases the level of information that each person has, the following research question is raised:

RQ2: Are the mobile applications and official websites of Portuguese and Spanish tourist destinations promoted through the Tur4all platform accessible?

The most important technology companies, such as Google and Apple, have introduced design and development guidelines for digital accessibility to facilitate mobile technology [38,39]. Notably, these companies have launched accessibility scanners that can be used to check the level of accessibility of mobile applications, whether Android or iOS [40,41]. Technology makes life easier for citizens through, for example, apps, in what is known as the concept of smart cities [42]. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) develops international standards for digital accessibility [23].

There are several notable studies on digital accessibility: empirical research based on a quantitative study of Norway’s tourism websites using the Website Accessibility Test (TAW) is among the most recent studies that analyzed the accessibility of tourism websites [10]. Other studies have also examined mobile application accessibility in the context of the tourism sector and smart cities [11,12]. Finally, research in sectors other than tourism that stand out include studies on the accessibility of India’s e-governance mobile apps [13] and air quality monitoring apps (focused on clean air) [14], both of which analyzed mobile accessibility through Google’s Accessibility Scanner tool.

From a legal perspective, Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 levels A and AA were approved based on EN 301 549 V3.1.1 (2019-11) by the European Commission. This international standard sets the current requirements that web pages must meet. In the case of mobile applications, they will be valid as of 23 June 2021. The Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 are based on four basic principles: Perceivable (Information and user interface components), Operable (User interface components and navigation), Understandable (Information and the operation of user interface) and Robust (Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents) [43]. Based on the criteria established by WCAG 2.1, the following research question is posed:

RQ3: What aspects of the content of websites and applications could be improved with respect to the WCAG 2.1, established by the W3C?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Setting

According to the World Tourism Organization, tourism is becoming increasingly important within the European economy [22]. Europe is the most visited region, receiving half of the world’s international tourist arrivals. The 28 countries of the European Union account for the majority of international arrivals in the region, about 81% of the total in Europe, which constitutes 40% of the global numbers [22].

This study focuses on analyzing the accessible destinations of Portugal and Spain since these two countries experience significant tourism. From the statistics, Spain, one of the countries under study, is the third most visited country in the world after France and the United States. The fourth largest destination is Portugal, which continued to boast strong growth following already-robust results. It was estimated to have 18 million overnight visitors [22]. These data from both Iberian countries were taken into account; in Spain, a survey on disability determined that there were 3,847,900 people who were disabled (about 8.5% of the inhabitants) according to data from the National Statistical Institute (INE) in Spain [44].

Furthermore, both countries are involved in a major project on accessible tourism called Tur4all [21]. This is a project promoted by different institutions in Portugal and Spain whose initial objective is to be the first accessible tourism platform managed by accessibility experts. Tur4all aims to reach other countries in the future. In Portugal, one of the members of the Tur4all.pt project, the “Accessible Portugal” organization, founded in 2006, is worth highlighting. This organization has its main origin in covering the need to promote accessible tourism because of the considerable increase in the aging of the population, which, together with their desire to travel, means that the public needs tourist destinations that offer services, facilities, routes and experiences adapted for everyone [45]. From Tur4all.es in Spain, the main institution that promotes this project is Predif, founded in 1996, which has also pledged accessible, inclusive and socially responsible tourism [21,46].

Therefore, it is clear that in recent years, as a result of the concept of accessible tourism and tourism for all, various tourism projects have been developed that focus on meeting the needs of the population segment under study and the overall market. In Spain, for example, Valencia launched in 2019, and it was the first accessible tourist guide for the visually impaired, allowing travelers to download different audio-guided routes around the city on mobile devices [47]. Another very interesting project to highlight from the point of view of accessible tourism is “Ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad”, where users can consult accessible routes that are available [48]. The Spanish Center for Subtitling and Audio Description (CESyA) organizes MUSEAC: the accessible museum congress, where professionals from the museum area and other public and private organizations meet to create a dialogue to find solutions that avoid barriers and ensure that museums are accessible to all types of users [49]. Additionally, of the two countries analyzed, Portugal was the first to receive the “Accessible Tourist Destination 2019” award from the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) [50]. This suggests that Portugal is highly oriented to this segment of the tourism market. In fact, it has launched the Accessible Beach and + Accessible Festivals program, which is inclusive of pregnant women, seniors and people in wheelchairs or with vision impairment, among others [51].

3.2. Sample

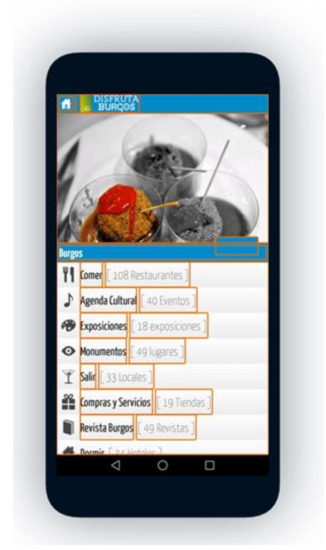

This research analyzes Portuguese and Spanish DMOs’ accessibility apps and websites that the Tur4all.com project lists as some of the most accessible destinations in these countries. Tur4all provides information on the conditions relating to the accessibility of different establishments in the tourism sector of different cities in both countries, such as hotels, restaurants, museums and monuments, adapted transport, etc. Therefore, the information must be up-to-date and reliable while being based on dynamic content [21]. In addition to its web version, it has a mobile app in which users visiting a destination can consult the most accessible routes, as well as all kinds of services that are integral in tourism for all (Figure 1). Through the web, a user can also carry out a specific search by destination and according to the required services, both in Spain and in Portugal (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Mobile app of the platform to find the most accessible services and establishments of the tourist destination selected by the user. Source: Tur4all [52,53].

Figure 2.

Web site from Tur4all Portugal and Spain with the search engine where the user can select and view the most accessible tourist destinations.

In this exploratory research work, based on a quantitative study, 39 home web pages of accessible destinations listed on the Tur4all platform were evaluated; 33 apps were analyzed because 6 Spanish destinations did not have an official app: Benidorm, Navarra, Gijón, Ibiza, Córdoba and Mallorca (Appendix A: Table A1 and Table A2). The rest of the destinations that were evaluated with their apps can be seen in Appendix A: Table A3 and Table A4.

3.3. Measures and Instrument

This exploratory research was carried out on the basis of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1. In June 2018, these latest W3C recommendations were approved, with a total of 13 guidelines and 78 compliance criteria [43], which are distributed among the four basic principles mentioned above. In turn, the WCAG 2.1 presents different levels of compliance, as can be seen in Appendix A: Table A5.

This study analyzed the fulfilment of a total of 50 success criteria in the case of websites (since levels A and double-A were considered in the assessment) and a total of 24 in the case of mobile apps (levels A, double-A and triple-A) (Appendix A: Table A6 and Table A7).

3.4. Data Collection

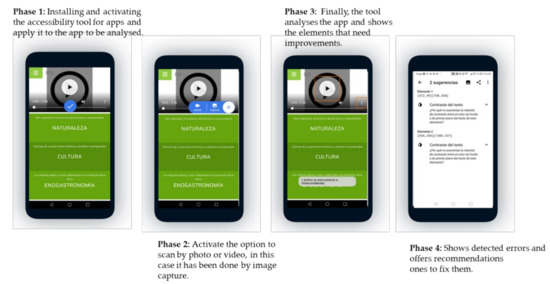

The analysis was carried out in the summer period, from the end of June to the beginning of September 2020. The methodology involved two types of accessibility evaluation tools. In the case of website analysis, the Wave tool [54], developed by Webaim, one of the main accessibility organizations, was used. For the analysis of mobile applications, the Google tool called Accessibility Scanner was used.

The smartphone used to install the analyzed applications had the Android version 7.0 operating system. Once these applications (from the Google Play Store) were installed on the smartphone, Google´s Accessibility Scanner was activated. This tool makes it possible to evaluate the accessibility of the mobile applications of these tourist destinations by applying the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 standard. This tool, once activated, requests permission from the user to capture screens. Once the user activates the blue button to perform the evaluation, it analyzes the accessibility of different areas of the apps, and the results are presented with recommendations for improvements (Appendix B: Figure A1 and Figure A2).

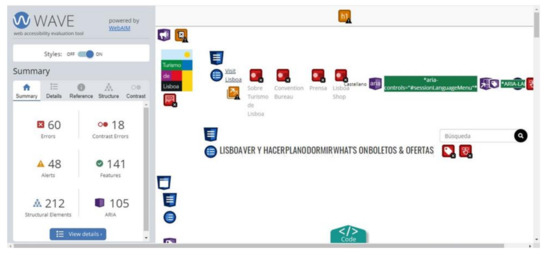

The Wave accessibility tool, which was used for the analysis of the 39 home pages of the studied websites, is an online analysis platform that shows indicators as it analyzes each of the URLs while applying the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1. The results of the tool that were taken into account for this analysis include the following parameters [54], as also shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Example of the accessibility analysis of the official Lisboa Tourism website (www.visitlisboa.com) using the Wave tool. Source: own elaboration from Wave [54].

Red “Errors” icons: These are errors that must be solved since they do not comply with WCAG 2.1.; recommendations on possible solutions are provided.

Red “Contrast Errors” icons: These indicate contrast errors with respect to the background and the text; the tool even indicates possible color solutions.

Yellow “Alerts” icons: These indicate elements that must be reviewed because they probably do not fully comply with the requirements of WCAG 2.1; they should be modified if they are erroneous or maintained if they are correct.

In addition, for a more thorough evaluation of the compliance of websites and official tourism apps, the tools in Table 1 were used. The table shows the tools that were used to screen both the web pages and apps to verify compliance with certain variables.

Table 1.

Tools used in a complementary way to Wave [54] and Google´s Accessibility Scanner [41].

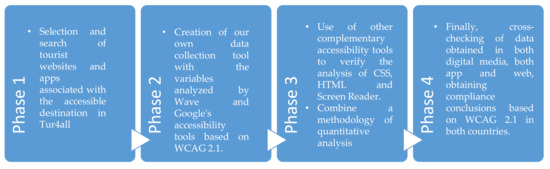

3.5. Data Analysis

Despite the quantitative approach, it is important to ensure the soundness of a methodological design developed as a new analysis system that includes different phases of the investigation (Figure 4). Therefore, other studies that have been carried out using Wave’s and Google´s Accessibility Scanner tools are used for comparison, which increases the robustness and reliability of this study [10,13,55,56].

Figure 4.

Selection, creation, complementary and checking (SCCC) model. Source: Own elaboration.

4. Results

The results are divided into two main subsections: first, the results for the websites of the DMOs analyzed in Portugal and Spain are presented, followed by the results of the associated apps.

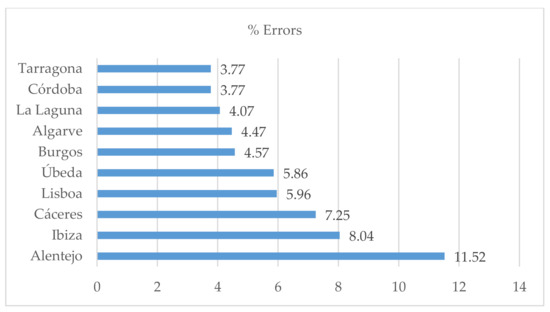

4.1. Results from the Aanalysis of Websites

As can be seen in Figure 5, among the analyzed destinations, the location with the highest percentage of accessibility errors is in Portugal. Of the 10 destinations with the highest percentages of accessibility errors on their official tourism websites, Alentejo has the most, followed by Ibiza, Cáceres, Lisboa, Úbeda, Burgos, Algarve, La Laguna, Córdoba and Tarragona. However, it should be noted that three of the analyzed websites do not present any accessibility errors, namely, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Mallorca and Gijón. Notably, among the results obtained, of the total of six tourism web pages analyzed from the accessible destinations of Tur4all Portugal, two of them belong to the Top 10 destinations with the most errors. In other words, 33% of the evaluated Portuguese destinations have a high percentage of errors.

Figure 5.

Percentage of errors in the official tourism websites of the Tur4all accessible destinations analyzed in Spain and Portugal. Source: own elaboration from Wave [54].

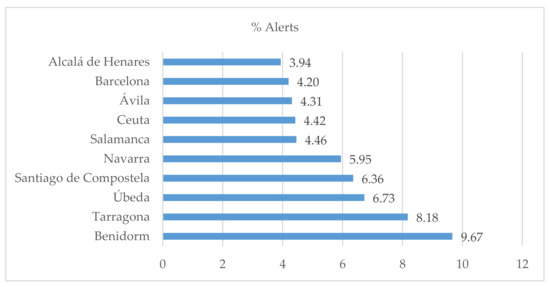

The alerts detected for the analyzed tourism web pages are shown in Figure 6. The top 10 web pages that present the most alerts all belong to Spanish destinations. Benidorm is the destination that presents the highest percentage with 9.67%, followed by Tarragona, Úbeda, Santiago de Compostela, Navarra, Salamanca, Ceuta, Ávila, Barcelona and Alcalá de Henares. In this case, it should be noted that there is no analyzed destination whose official tourism website does not present any alerts; although the percentages are small for some web pages, all of them present some type of alert that must be reviewed. The percentages of alerts for the tourism websites of Portuguese destinations are all below 3%, starting with Porto e Norte with 2.75% detected alerts and ending with Alentejo with 0.82%.

Figure 6.

Percentage of alerts in the official tourism websites of the Tur4all accessible destinations analyzed in Spain and Portugal. Source: own elaboration from Wave [54].

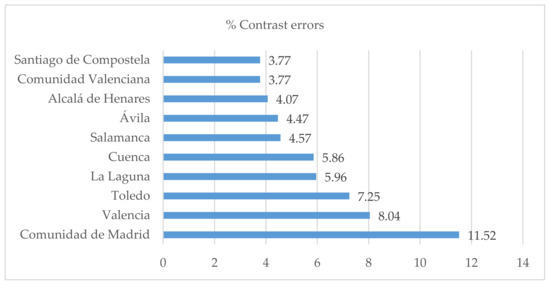

Figure 7 shows the percentage of contrast errors for the analyzed destination web pages. Spanish destinations again stand out among the 10 destinations with the highest percentages, starting with the Comunidad de Madrid with 11.52%, followed by Valencia, Toledo, La laguna, Cuenca, Salamanca, Ávila, Alcalá de Henares and the Comunidad Valenciana. In this case, some of the analyzed Portuguese destinations do not present any contrast errors: Madeira, Lisboa and Açores. The rest of the analyzed Portuguese destinations also have very small percentages of contrast errors, with only 0.20% for Porto e Norte, Algarve and Alentejo.

Figure 7.

Percentage of contrast errors in the official tourism websites of the Tur4all accessible destinations analyzed in Spain and Portugal. Source: own elaboration from Wave [54].

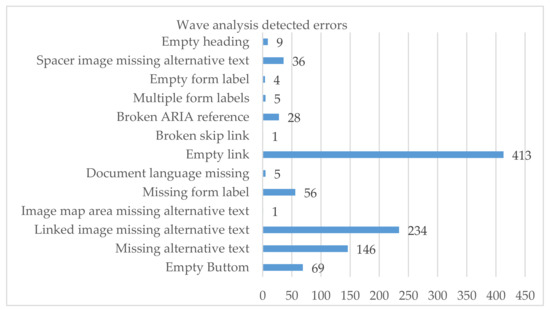

The details of several errors are presented in more detail in Figure 8. Of the analyzed sample, a total of 413 errors are related to “Empty link”, followed by “Linked image missing alternative text” and “Missing alternative text” (Figure 8). As a result, screen readers will not be able to access the content of an image, and in the case of links, there is no content to present to the user with respect to the function of the link, which is especially relevant for users who have vision problems. Additionally, if connection problems occur and the image cannot be displayed, its content is represented by means of text.

Figure 8.

Errors that do not comply with WCAG 2.1 detected in the analyzed sample. Source: own elaboration from Wave [54].

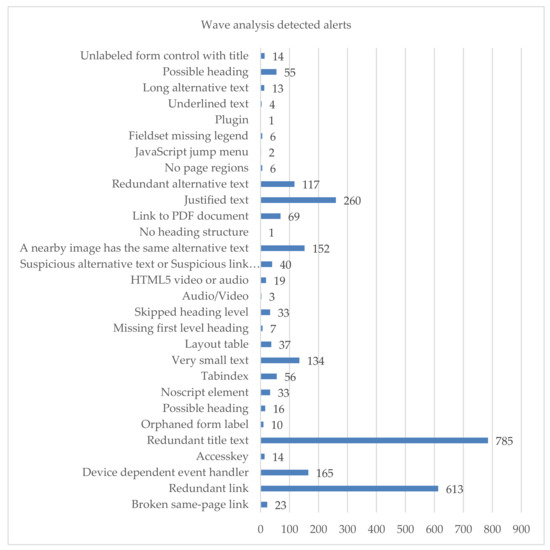

The alerts that were detected in the greatest numbers are “Redundant Title Text” (in most cases, the title attribute can be removed or modified to provide guidance, but redundant information is not recommended); “Redundant Link” (if possible, redundant links are combined into one link, and any redundant text or alternative text is removed); and “Justified text” (large blocks of justified text can have a negative impact on readability) (Figure 9). Furthermore, 5 of the 39 analyzed web pages contain embedded software to facilitate accessibility, specifically the software insuit (www.insuit.net). The official tourism websites that contained this program correspond to the Spanish destinations Ávila, Benidorm, Navarra, Cartagena and Cuenca (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Alerts that do not comply with WCAG 2.1 detected in the analyzed sample. Source: own elaboration from Wave [54].

Figure 10.

Example of one of the analyzed websites showing the presence of an accessible embedded software that allows it to be activated by users. Source: own elaboration.

4.2. Results from the Analysis of Apps

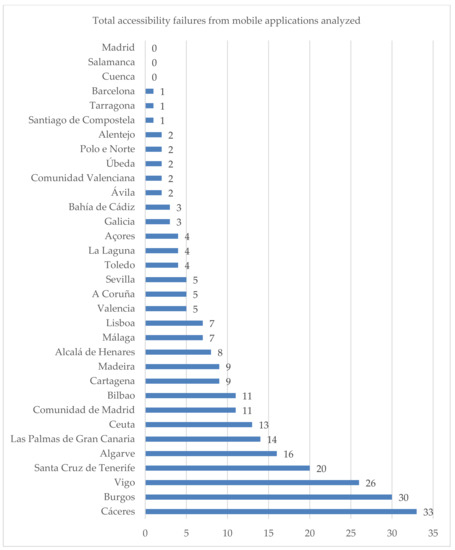

Of the total number of mobile applications analyzed (Figure 11), the accessible tourist destinations of the Tur4all program that have the greatest number of errors are the following: Cáceres, Burgos, Vigo, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Algarve, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Ceuta, Comunidad de Madrid and Bilbao. The rest of the accessible destination apps analyzed by this program have fewer than 10 errors. Notably, in Portugal, only one destination’s app that was deemed accessible has more than 10 errors. Madrid, a local destination, does not present any errors in its official tourism app; however, in the case of the Comunidad de Madrid, more at the regional level of travel, the app does exceed the threshold of 10 errors.

Figure 11.

Total analyzed mobile app accessibility failures. Source: own elaboration from Google´s Accessibility Scanner [41].

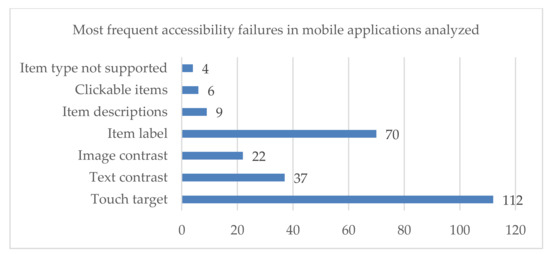

Figure 11 shows the detected accessibility errors, among which the most predominant are “Touch Target” with a total of 112 errors and “Item Label” with 70. As the Google´s Accessibility Scanner tool explains, a Touch Target error implies that the user cannot easily interact with elements that need to be clicked since they are not large enough for the user to activate. Item Label indicates the absence of such a label, which can prevent a user from reading the content on the screen; thus, this presents a barrier to accessibility to the content by users with vision problems. The same scenario applies for “Item Descriptions”. As can be seen in Figure 12, other errors that occur are related to contrast. Among contrast errors, more are related to text contrast than image contrast. Text contrast is important not only for users with vision problems but also for those who are in environments with too little or too much lighting (for example, low screen brightness or a light from the sun that hits the screen directly).

Figure 12.

Most frequent errors in the analyzed sample. Source: own elaboration from Google´s Accessibility Scanner [41].

The data are also broken down by the destination in terms of each of the detected errors. In this case, only destinations that have presented errors for each of the analyzed variables are shown, and they are grouped as follows to facilitate analysis, based on the criteria determined by the Google´s Accessibility Scanner tool [41]: “Touch Target Size”, “Low Contrast” (Image contrast and text contrast), “Content Labeling” (Item Label and Item Description) and “Implementation” (Clickable Items and Item type not supported). From these data, Cáceres stands out as one of the destinations that presents the most errors in the categories “Touch Target Size”, “Low Contrast” and “Implementation”. However, in terms of “Content Labeling”, the Vigo app presents the most errors.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to identify whether the DMOs in Portugal and Spain are digitally accessible according to W3C [57] as stated in WCAG 2.1, based on a sample selected from the Tur4all accessible destinations project. The review found studies based on the importance of this segment within the tourism sector market [6,7,8,9] but, from the point of view of the analysis of digital accessibility, no studies have been found that analyze web pages and applications in the same institution. Therefore, the results have been compared with the few existing studies on the web’s accessibility of the tourism sector [10,11,12]. The review found no author or journal with extensive publication in the field of the accessible addressing app mobile and websites, despite the increasing number of articles published in high-impact journals within the tourism field that have taken an interest in the topic. Therefore, other studies on websites [55,56,58] and mobile applications in other sectors have been taken into account [13,14,59,60,61,62,63,64]. No similar studies have been found directly related to Spain and Portugal. Moreover, the findings revealed three important contributions to the study of the topic, namely.

5.1. Accessibility Digital Criteria of Spanish and Portuguese DMOs

This study’s findings show that regarding the first research question (Which country best meets the accessibility digital criteria?), more than 70% of the detected accessibility errors are concentrated in DMOs from Spain. In addition, this investigation also shows that the only three destinations that are fully accessible are Spanish; that is, they do not present any errors. The opposite occurs for the percentage of contrast errors on the web-sites: the only three destinations that do not present any type of contrast error are Portuguese. The percentage of contrast errors on the websites of the evaluated Spanish destinations are much higher: 99.4%. From the results for the apps studied, the percentage of errors in Spanish destinations is higher than that of Portuguese locations, with more than 84% of detected errors for DMOs from Spain (Figure 11). Therefore, it is concluded that both the websites and mobile applications of the analyzed Portuguese destinations present better compliance with the digital accessibility criteria of WCAG 2.1 than those of the Spanish destinations. These findings are important because they highlight the need to comply with the digital accessibility regulations approved internationally by the W3C based on WCAG 2.1. Even in countries with strong disability rules and regulations, studies have shown that the results are very poor in terms of compliance with digital accessibility criteria [10,11,12].

5.2. Level of Accessibility of Mobile Applications and Official Websites of the Portuguese and Spanish DMOs

The findings of the study can also be used to explore the second research question: Are the mobile applications and official websites of the Portuguese and Spanish tourist destinations promoted through the Tur4all platform accessible? Our results show that the mobile applications and official websites of the Portuguese and Spanish tourist destinations promoted through the Tur4all platform are not fully accessible according to W3C [57] as stated in WCAG 2.1. Figure 5 and Figure 7 show the percentage of accessibility and contrast errors for the home pages of the evaluated websites, and Figure 11 shows the errors detected in the evaluated mobile applications. Only 3 of the 33 analyzed mobile applications are accessible, and in the case of the analyzed websites, only 3 of 39 are accessible.

Moreover, similarly to other studies [10,11,12], despite the growing importance of electronic commerce and digital platforms, companies in the tourism sector still face significant challenges in their implementation, particularly in terms of the organization and internal structure of human resources, which requires changes in attitude. Thus, tourism companies need to strengthen these areas [64].

5.3. Most Common Errors in the Analyzed Websites and Mobile Applications

Regarding the third research question (What aspects of the content analysis of web-sites and applications could be improved with respect to the WCAG 2.1 established by the W3C?): We conclude that, with regard to content, most of the errors and alerts on websites are related to the text or empty links, as seen in Figure 8 and Figure 9. These types of errors in the content can be solved by, for example, adding an alt attribute to the image or providing the text within the relationship that describes the functionality and/or the destination of the link. For mobile applications, improvements should be applied to the content in relation to “Touch Target Size” and “Content Labeling” (Figure 12). In these two cases, the main recommendation is to increase the width of the touch element of the application or associate a label with the element in question so that it can be read from the screen.

Our findings highlight that these errors must be taken into account by marketing and communication professionals who lead digital projects, since they are responsible for ensuring that the digital content of their organization (public or private) is accessible to all users, regardless of their disability. In a similar study on the official tourism websites of Norway, Sweden, Iceland, the United Kingdom and Germany, the results revealed an alarming number of warnings, although in this case, the analysis was carried out with the TAW accessibility tool [10]. In this study, the results for mobile applications coincide with those of Acosta-Vargas et al. [14], who identified “Touch target” as one of the indicators associated with the most errors, although their analysis was carried out in a different sector related to environmental apps. A similar result is found for errors associated with “item label” in the apps [59]. Therefore, there are still significant accessibility barriers within applications [60,61,62,63,64] and websites [55,56,58].

The results obtained in this study suggest that the level of accessibility compliance is low. Therefore, greater awareness of its importance is required to improve compliance. In addition, many of the detected errors must be corrected.

6. Conclusions

This study’s goal was to identify whether the DMOs in Portugal and Spain are digitally accessible. Despite previous studies focusing on this line of research (digital accessibility), none provided a global vision about its compliance, both on the websites and mobile applications of the same institution. Our research has found how the percentage of non-compliance with accessibility criteria is very high in DMOs in Portugal and, especially, Spain. In particular, we found that compliance must be improved so that tourism is accessible to everyone, not only for the physical destinations promoted by the Tur4all.com platform but also for the associated digital tools. Thus, we consider that improving accessibility requires not only emphasizing the need to ensure compliance with existing laws and regulations on digital accessibility, but also raising awareness of its importance among the stakeholders responsible for marketing and communication compliance in both public and private institutions. Therefore, this study fills a gap in the recent literature on digital accessibility, since this is the only one that analyzes the apps and official tourism websites of Portugal and Spain based on WCAG 2.1. Furthermore, we developed an analysis and data collection methodology for both tools, as there is an absence of similar studies that analyze both forms of digital media in other countries. Additionally, previous works conducted in different sectors, either from an institutional or private point of view, have stated that compliance with accessibility criteria must be reinforced [55,56,58]. Our study has shown that the results are very poor in terms of compliance with digital accessibility criteria, promoting the need that even in countries with strong disability rules and regulations there is much to improve in terms of accessibility and tourism for all [10,11,12].

6.1. Managerial and Theoretical Implications

One of the main practical and general implications of this study is the recommendations on how to solve the errors that were detected in the analysis, which can serve as a guide for communication experts who lead this type of project, including programmers, designers or marketing or communication directors in public or private companies. This study specifically provides clues on the crucial aspects in the planning and designing of websites, which can help DMO’s increase users’ interaction and consequently may help to increase user’s engagement and experience when accessing the websites. This research also serves to raise theoretical awareness about the importance of digital accessibility, especially in the tourism sector, whether at a public or private level. Moreover, the technologies behind DMO’s websites need to be explored in more details for a better symbiosis between the technological and theoretical framework.

6.2. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

The main limitations of this study are primarily based on the fact that the analyzed sample includes only Portuguese and Spanish DMOs. Furthermore, the apps were analyzed using only the Android system because it is the most widely used by the population worldwide [31]. Thus, future research should also run tests using the iOS system. This analysis methodology can also be extended to other official tourism websites and apps in European countries, where the results can be compared with those obtained in this study for Spain and Portugal. From the conclusions drawn from this future line of research based on both operating systems that comprise a wider geographic range of countries, a manual of good practices for digital accessibility in the tourism sector is needed in order to raise awareness of its importance and reduce digital barriers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F.-D.; Funding acquisition, M.B.C. and N.d.M.; Investigation, E.F.-D.; Methodology, E.F.-D., M.B.C. and N.d.M. Supervision, E.F.-D., M.B.C. and N.d.M.; Visualization, E.F.-D., M.B.C.; Writing—review and editing, E.F.-D., M.B.C. and N.d.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Funds provided by FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology through projects UIDB/04470/2020 and UIDB/04020/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data is available from the authors with permission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample of official tourism websites of accessible Spanish destinations shown in Tur4all.es.

Table A1.

Sample of official tourism websites of accessible Spanish destinations shown in Tur4all.es.

Source: own elaboration. Accessed on 1 June 2020.

Table A2.

Sample of official tourism websites of accessible destinations Portuguese shown in Tur4all.pt.

Table A2.

Sample of official tourism websites of accessible destinations Portuguese shown in Tur4all.pt.

| Tur4all.Pt/Destinations | Main URL Analyzed Year 2020 | With App |

|---|---|---|

| Porto e Norte | http://www.portoenorte.pt/es/ | Yes |

| Alentejo | https://www.visitalentejo.pt/es/ | Yes |

| Algarve | https://www.visitalgarve.pt/ | Yes |

| Açores | https://www.visitazores.com/ | Yes |

| Madeira | http://www.visitmadeira.pt/es-es/homepage | Yes |

| Lisboa | https://www.visitlisboa.com/es | Yes |

Source: own elaboration. Accessed on 1 June 2020.

Table A3.

Spanish accessible destinations from the Tur4all.es platform analyzed as a sample from the accessibility point of view of their mobile tourism applications.

Table A3.

Spanish accessible destinations from the Tur4all.es platform analyzed as a sample from the accessibility point of view of their mobile tourism applications.

| Accessible Tourist Destination from Tur4all Programme | APP Analyzed (Name) | Logotype | Last Update | APP Version | Android Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comunidad de Madrid | Guía Madrid 5D |  | 6 Feb 2017 | 1.04 | 4.0.3 and later |

| Valencia | Visit Valencia Guía oficial |  | 18 Jun 2020 | 1.0.0-b9822d0-pro | 5.0 and later |

| Toledo | Toledo |  | 25 Jan 2017 | 1.0 | 4.0 and later |

| La Laguna (Sta. Cruz de Tenerife) Canarias | Turismo la Laguna/Santa Cruz de Tenerife |  | 31 July 2020 | 8.0.2 | 4.3 and later |

| Cuenca | Cuenca |  | 17 April 2015 | 2 | 2.3 and later |

| Salamanca | Salamanca Turismo |  | 10 Aug 2020 | 2.6.9 | 5.0 and later |

| Ávila | Ávila Te Toca Guía Turismo |  | 9 Jun 2020 | 10.0.0 | 5.0 and later |

| Alcalá de Henares | Visita Alcalá-Guía oficial |  | 11 Jun 2020 | 1.0 | 4.0.3 and later |

| Santiago de Compostela | Santiago de Compostela |  | 1 Marz 2017 | 1.23 | 4.1 and later |

| Comunidad Valenciana | Experiencias CV |  | 8 May 2018 | 0.5.73 | 4.1 and later |

| Ceuta | Ceuta Guía Oficial |  | 7 Jun 2020 | 7.0.0 | 4.1 and later |

| Úbeda | Cartel Guía Oficial de Úbeda |  | 29 Jan 2020 | 2.0.0 | 4.4 and later |

| Burgos | Disfruta Burgos |  | 20 July 2016 | 1.1.2 | 4.0.3 and later |

| Madrid | Guía Bienvenidos a Madrid |  | 4 Oct 2016 | 1.2.2 | 4.1 and later |

| Galicia | Turismo Galicia |  | 10 Marz 2017 | 1.0.1 | 4.1 and later |

| Cáceres | Cáceres View |  | 9 May 2019 | 3.2 | 5.0 and later |

| Tarragona | Imageen Tarragona |  | 17 July 2019 | 5 | 4.4 and later |

| Barcelona | Barcelona. Guía oficial |  | 23 Oct 2019 | 2.7.0 | 4.0.3 and later |

| A Coruña | Rutas Coruña |  | 26 Jan 2016 | 2.0.2 | 4.0.3 and later |

| Bahía de Cádiz | App Oficial Turismo de Cádiz |  | 14 Marz 2019 | 2.2 | 4.1 and later |

| Cartagena | Consejería Cartagena de Indias |  | 16 May 2020 | 2.1.2 | 4.0 and later |

| Bilbao | InfoBilbao. Agenda Oficial |  | 3 Dec 2019 | 1.3.2 | 4.4 and later |

| Málaga | Malaga Turismo |  | 14 Dec 2018 | 1.1.0 | 4.4 and later |

| Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | LPGC Tu Ciudad |  | 14 Jun 2019 | 2.0.2 | 4.4 and later |

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Cultura Santa Cruz |  | 11 Feb 2019 | 100 | 4.4 and later |

| Sevilla | Turismo Provincia de Sevilla |  | 6 Feb 2020 | 2.0.0 | 4.4 and later |

| Vigo | Turismo de Vigo |  | 23 May 2016 | 1.0.4 | 2.1 and later |

Source: own elaboration from Google Play Store [65].

Table A4.

Portuguese accessible destinations from the Tur4all.pt platform analyzed as a sample from the accessibility point of view of their mobile tourism applications.

Table A4.

Portuguese accessible destinations from the Tur4all.pt platform analyzed as a sample from the accessibility point of view of their mobile tourism applications.

| Accessible Tourist Destination from Tur4all Programme | APP Analyzed (Name) | Logotype | Last Update | APP Version | Android Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porto e Norte | Porto e Norte |  | 18 Jul 2017 | 1.2 | 4.1 and later |

| Alentejo | Turismo do Alentejo |  | 8 Oct 2017 | 1.0.1 | 4.0 and later |

| Algarve | Algarve Eventos—Events |  | 30 Jan 2019 | 1.1.4 | 4.0.3 and later |

| Açores | VisitAzores |  | 7 Feb 2019 | 02.02.02.0003 | 2.3 and later |

| Madeira | Feeling Madeira |  | 20 Oct 2014 | 1.15 | 2.3 and later |

| Lisboa | Visit Lisboa |  | 28 Oct 2017 | 1.2.1 | 0 |

Source: own elaboration from Google Play Store [65].

Table A5.

Suitability levels according to the level of compliance (A, double A or triple A).

Table A5.

Suitability levels according to the level of compliance (A, double A or triple A).

| Conformance Level | Web Content Accessibility Guidelines | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Conformance Level A | WCAG 1.0: all Priority 1 checkpoints are satisfied. | W3C [66] |

| WCAG 2.0: all level A compliance criteria are satisfied. | W3C [67] | |

| WCAG 2.1: all level A compliance criteria are satisfied. | Revilla Muñoz & Carreras Montoto [68] | |

| Conformance Level AA | WCAG 1.0: all Priority 1 and 2 checkpoints are satisfied. | W3C [66] |

| WCAG 2.0: all level A and AA compliance criteria are satisfied. | W3C [67] | |

| WCAG 2.1: all level A and AA compliance criteria are satisfied. | Revilla Muñoz & Carreras Montoto [68] | |

| Conformance Level AAA | WCAG 1.0: all Priority 1, 2, and 3 checkpoints are satisfied. | W3C [66] |

| WCAG 2.0: all level A, AA and AAA compliance criteria are satisfied. | W3C [67] | |

| WCAG 2.1: all level A, AA and AAA compliance criteria are satisfied. | Revilla Muñoz & Carreras Montoto [68] |

Source: own elaboration.

Table A6.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (level A) and other W3C/WAI Guidelines apply to mobile.

Table A6.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (level A) and other W3C/WAI Guidelines apply to mobile.

| Principle | Guidelines WCAG 2.1 | Checkpoints WCAG 2.1 | Success Criteria for Mobile Applications | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Perceivable | Guideline 1.1: Text Alternatives | 1.1.1 Non-text Content | A | |

| 1.2.1 Prerecorded Audio-only and Video-only | A | |||

| Guideline 1.2: Time-based Media | 1.2.2 Captions (Prerecorded) | A | ||

| 1.2.3 Audio Description or Media Alternative (Prerecorded) | A | |||

| 1.3.1 Info and Relationships | A | |||

| Guideline 1.3: Adaptable | 1.3.2 Meaningful Sequence | A | ||

| 1.3.3 Sensory Characteristics | A | |||

| Guideline 1.4: Distinguishable | 1.4.1 Use of Color | A | ||

| 1.4.2 Audio Control | A | |||

| 2—Operable | Placing buttons where they are easy to access | |||

| Guideline 2.1: Keyboard Accessible | 2.1.1 Keyboard | Device manipulation gestures/Keyboard control for touchscreen devices | A | |

| 2.1.2 No Keyboard Trap | Keyboard control for touchscreen devices | A | ||

| 2.1.4 Character Key Shortcuts (Added in 2.1) | A | |||

| Guideline 2.2: Enough Time | 2.2.1 Timing Adjustable | A | ||

| 2.2.2 Pause, Stop, Hide | A | |||

| Guideline 2.3: Seizures and Physical Reactions | 2.3.1 Three Flashes or Below Threshold | A | ||

| Guideline 2.4: Navigable | 2.4.1 Bypass Blocks | A | ||

| 2.4.2 Page Titled | A | |||

| 2.4.3 Focus Order | Keyboard control for touchscreen devices | A | ||

| 2.4.4 Link Purpose (In Context) | Grouping operable elements that perform the same action | A | ||

| Guideline 2.5: Input Modalities | 2.5.1 Pointer Gestures (Added in 2.1) | A | ||

| 2.5.2 Pointer Cancellation (Added in 2.1) | A | |||

| 2.5.3 Label in Name (Added in 2.1) | A | |||

| 2.5.4 Motion Actuation (Added in 2.1) | A | |||

| 3—Understandable | Guideline 3.1: Readable | 3.1.1 Language of Page | A | |

| Guideline 3.2: Predictable | 3.2.1 On Focus | A | ||

| 3.2.2 On Input | A | |||

| Guideline 3.3: Input Assistance | 3.3.1 Error Identification | A | ||

| 3.3.2 Labels or Instructions | A | |||

| 4—Robust | Set the virtual keyboard to the type of data entry required | |||

| Provide natural methods for data entry | ||||

| Support the characteristic properties of the platform | ||||

| Guideline 4.1: Compatible | 4.1.1 Parsing | A | ||

| 4.1.2 Name, Role, Value | A |

Source: own elaboration from W3C [57] and W3C [69].

Table A7.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (level double A and triple A) and other W3C/WAI Guidelines apply to mobile.

Table A7.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (level double A and triple A) and other W3C/WAI Guidelines apply to mobile.

| Principle | Guidelines WCAG 2.1 | Checkpoints WCAG 2.1 | Success Criteria for Mobile Applications | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Perceivable | Small screen size | |||

| Guideline 1.2: Time-based Media | 1.2.4 Captions (Live) | AA | ||

| 1.2.5 Audio Description (Prerecorded) | AA | |||

| Guideline 1.3: Adaptable | 1.3.4 Orientation (Added in 2.1) | AA | ||

| Guideline 1.4: Distinguishable | 1.4.3 Contrast (Minimum) | 1.4.3 Contrast which requires a contrast of at least 4.5:1 (or 3:1 for large-scale text) and | AA | |

| 1.4.4 Resize text | Zoom/magnification | AA | ||

| 1.4.5 Images of Text | AA | |||

| 1.4.6 Contrast (Enhanced) | 1.4.6 Contrast which requires a contrast of at least 7:1 (or 4.5:1 for large-scale text) | AAA | ||

| 1.4.10 Reflow (Added in 2.1) | AA | |||

| 1.4.11 Non-text Contrast (Added in 2.1) | AA | |||

| 1.4.12 Text Spacing (Added in 2.1) | AA | |||

| 1.4.13 Content on Hover or Focus (Added in 2.1) | AA | |||

| 2—Operable | Touchscreen gestures | |||

| Guideline 2.4: Navigable | 2.4.5 Multiple Ways | AA | ||

| 2.4.6 Headings and Labels | AA | |||

| 2.4.7 Focus Visible | Keyboard control for touchscreen devices | AA | ||

| 2.4.9 Link Purpose (Link Only) | Grouping operable elements that perform the same action | AAA | ||

| Guideline 2.5 Input Modalities | 2.5.5 Target Size | Touch target size and spacing | AAA | |

| 3—Understandable | Changing screen orientation (portrait/landscape) | |||

| Positioning essential page elements before the page scroll | ||||

| Provide clear indication that elements are actionable | ||||

| Guideline 3.1: Readable | 3.1.2 Language of Parts | AA | ||

| Guideline 3.2: Predictable | 3.2.3 Consistent Navigation | Consistent layout/Provide instructions for custom touchscreen and device manipulation gestures | AA | |

| 3.2.4 Consistent Identification | AA | |||

| Guideline 3.3: Input Assistance | 3.3.3 Error Suggestion | AA | ||

| 3.3.4 Error Prevention (Legal, Financial, Data) | AA | |||

| 4—Robust | Guideline 4.1: Compatible | 4.1.3 Status Messages (Added in 2.1) | AA | |

Source: own elaboration from W3C [57] and W3C [69].

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Phases from evaluation of accessibility in mobile applications [41]. Source: own elaboration.

Figure A2.

Example of the accessibility analysis of the official Burgos app using Google´s Accessibility Scanner [41]. Source: own elaboration.

References

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Accessible Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/accessibility (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Manual on Accessible Tourism for All: Principles, Tools and Best Practices–Module I: Accessible Tourism–Definition and Context; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Report on Disability; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 1–350. Available online: https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- European Comission. Tourism for All. Benefits of Physical Accessibility for Your Business. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/tourism/business-portal/accessibility_en (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Domínguez, T.; Fraiz, J.A.; Alen, E. Economic profitability of accessible tourism for the tourism sector in Spain. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özogul, G.; Baran, G.G. Accessible tourism: The golden key in the future for the specialized travel agencies. J. Tour. Futures 2016, 2, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, R. The contribution of holiday trips to life satisfaction: The case of people with disabilities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsarnoczky, M. Accessible tourism in the European Union. In Proceedings of the 6th Central European Conference in Regional Science, Engines of Urban and Regional Development, Budapest, Hungary, 1–2 September 2017; pp. 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, D.T.; González, A.E.; Darcy, S. Accessible tourism online resources: A Northern European perspective. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.D.; Aarnoutse, S.J.C.; Gea, D.d.J.M.; Berná, G.J.A.; Alemán, F.J.L.; Mateos, G.G. Design and Development of a Mobile App for Accessible Beach Tourism Information for People with Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.A.; Olmedo, E.; Tadeu, P.; Batanero, F.J.M. Propuesta de las condiciones de las Aplicaciones móviles, para la construcción de un Entorno de Accesibilidad Personal para usuarios con discapacidad visual en las Smart Cities. Aula Abierta 2019, 48, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, V.; Kuppusamy, K.S. Accessibility analysis of e-governance oriented mobile applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Accessibility to Digital World (ICADW), Guwahati, India, 16–18 December 2016; pp. 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.P.; Zalakeviciute, R.; Mora, L.S.; Hernandez, W. Accessibility Evaluation of Mobile Applications for Monitoring Air Quality. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. In Information Technology and Systems (ICITS); Rocha, Á., Ferrás, C., Paredes, M., Eds.; Francisco José de Caldas District University: Bogota, Columbia, 2019; Volume 918, pp. 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Introducción a la Accesibilidad Web. ¿Qué es la Accesibilidad Web? Available online: https://www.w3c.es/Traducciones/es/WAI/intro/accessibility (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Peters, K.; Chen, Y.; Kaplan, A.M.; Ognibeni, B.; Pauwels, K. Social media metrics: A framework and guidelines for managing social media. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Li, X. Destination image: Do top-of-mind associations say it all? Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 45, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datareportal. Digital 2020: Global digital overview. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Datareportal. Digital 2020: Portugal. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-portugal?rq=portugal (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Datareportal. Digital 2020: Spain. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-spain?rq=spain (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Tur4all. Home Page Oficial. Available online: https://www.tur4all.com (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). European Union Tourism Trends; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 1–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W3C. About w3c. Available online: https://www.w3.org/Consortium (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Buhalis, D.; Darcy, S. Accessible Tourism: Concepts and Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2010; pp. 1–336. [Google Scholar]

- Loi, L.K.; Kong, H.W. Tourism for All: Challenges and Issues Faced by People with Vision Impairment. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K.; Stacey, J. Towards a ‘tourism for all’ policy for Ireland: Achieving real sustainability in Irish tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, E.C.; Jolin, L. The International Organisation of Social Tourism (ISTO) working towards a right to holidays and tourism for all. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.A. The welfare state and tourism for all. Reasons why people do not travel. Cuad. Tur. 2018, 41, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Employment of disabled people. In Statistical Analysis of the 2011 Labour Force Survey ad Hoc Module; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2015; pp. 1–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación ACS and Organización Mundial del Turismo (OMT). Manual de Turismo Accesible para Todos: Alianzas Público-Privadas y Buenas Practices; OMT: Madrid, Spain, 2014; pp. 1–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statcounter GlobalStats. Mobile Operating System Market Share Worldwide. October 2019–October 2020. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/worldwide (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Statcounter GlobalStats. Mobile Operating System Market Share Spain. October 2019–October 2020. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/spain (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Statcounter GlobalStats. Mobile Operating System Market Share Portugal. October 2019–October 2020. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/portugal (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Statcounter GlobalStats. Desktop vs. Mobile vs. Tablet Market Share Worldwide. October 2019–October 2020. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/platform-market-share/desktop-mobile-tablet (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Statcounter GlobalStats. Desktop vs. Mobile vs. Tablet Market Share Spain. October 2019–October 2020. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/platform-market-share/desktop-mobile-tablet/spain (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Statcounter GlobalStats. Desktop vs. Mobile vs. Tablet Market Share Portugal. October 2019–October 2020. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/platform-market-share/desktop-mobile-tablet/portugal (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Vila, D.T.; González, A.E.; Vila, A.N.; Brea, F.J.A. Indicators of Website Features in the User Experience of E-Tourism Search and Metasearch Engines. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apple. Accessibility on iOS. Available online: https://developer.apple.com/accessibility/ios (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Google. Build More Accessible Apps. Available online: https://developer.android.com/guide/topics/ui/accessibility (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Apple. Testing for Accessibility on OS X. Available online: https://developer.apple.com/library/archive/documentation/Accessibility/Conceptual/AccessibilityMacOSX/OSXAXTestingApps.html (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Google. Accessibility Scanner. v 2.0.0.291991417. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.google.android.apps.accessibility.auditor (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Moreno, O.E.V.; Delgado, L.A. From smart cities to smart human cities: Digital inclusion in app’s. Rev. Fuentes 2015, 17, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W3C. Introduction to Understanding WCAG 2.1. Available online: https://www.w3.org/WAI/WCAG21/Understanding/intro (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- INE. Survey on Disability, Independence and Dependence Situations. 2008. Available online: http://www.ine.es/jaxiPx/tabla.do?type=pcaxis&path=/t15/p418/a2008/hogares/p01/modulo1/l0/&file=01010.px&L=1 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Accessibleportugal. Quem Somos. Available online: http://accessibleportugal.com (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Predif. Quiénes somos. Available online: https://www.predif.org/quienes-somos (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Europapress. Valencia Edita la Primera Guía de Turismo Accesible Para Invidentes. 2019. Available online: https://www.europapress.es/turismo/destino-espana/costa-blanca/noticia-ayuntamiento-valencia-edita-primera-guia-turismo-accesible-personas-invidentes-20190201171436.html (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad. Rutas Accesibles. 2020. Available online: https://www.ciudadespatrimonio.org/accesibilidad/?idioma=en (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Discapnet. Jornada de Museos Accesibles (MUSEAC). 2019. Available online: https://www.discapnet.es/actualidad-y-eventos/agenda/jornada-museos-accesibles-museac (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). UNWTO and Fundación ONCE Deliver International Recognition of ‘Accessible Tourist Destinations’ at FITUR. 2020. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/unwto-and-fundacion-once-deliver-international-recognition-of-accessible-tourist-destinations-at-fitur (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Smarttravel. Portugal Gana el Premio “Destino Turístico Accesible” de la OMT. 2020. Available online: https://www.smarttravel.news/portugal-gana-premio-inedito-destino-turistico-accesible-la-omt/#:~:text=Portugal%20es%20el%20primer%20pa%C3%ADs,celebr%C3%B3%20en%20San%20Petersburgo%2C%20Rusia (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Tur4all. Aplicaciones-Moviles. Available online: https://www.tur4all.es/es/aplicaciones-moviles/app-tur4all (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Tur4all. Aplicacoes-Moveis. Available online: https://www.tur4all.pt/pt/aplicacoes-moveis (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Wave. Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool. Available online: https://wave.webaim.org (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Vargas, A.P.; Acosta, T.; Mora, L.S. Challenges to assess Accessibility in Higher Education Websites: A comparative Study of Latin America Universities. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 36500–36508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Kuppusamy, K. Accessibility of Indian universities’ homepages: An exploratory study. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2018, 30, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W3C. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Mora, L.S.; Navarrete, R.; Peñafiel, M. Egovernment and web accessibility in South America, 2014. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment (ICEDEG), Quito, Equador, 24–25 April 2014; pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.S.; Zhang, X.; Fogarty, J.; Wobbrock, J.O. Examining Image-Based Button Labeling for Accessibility in Android Apps through Large-Scale Analysis. In Proceedings of the 20th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ‘18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–2 October 2018; pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinell, C.R.; Bailey, C.; Gkatzidou, V. Investigating the Appropriateness and Relevance of Mobile Web Accessibility Guidelines. In Proceedings of the 11th Web for All Conference (W4A ‘14), Seoul, Korea, 7–9 April 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Ramachandran, P.G. The Current Status of Accessibility in Mobile Apps. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2019, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, C.L.; Carvalho, P.L.; Ferreira, P.L.; Vaz, B.S.J.; Freire, A.P. Accessibility Evaluation of E-Government Mobile Applications in Brazil. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 67, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.L.; Peruzza, P.M.B.; Santos, F.; Ferreira, P.L.; Freire, P.A. Accessible Smart Cities? Inspecting the Accessibility of Brazilian Municipalities’ Mobile Applications. In Proceedings of the 15th Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computer Systems-IHC ‘16, São Paulo, Brazil, 4–7 October 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondović, B.; Djuričković, T.; Kašćelan, L. Drivers of E-Business Diffusion in Tourism: A Decision Tree Approach. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 14, s0718–s18762019000100104. [Google Scholar]

- Google Play Store. Apps. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps?hl=es_419&gl=US (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- W3C. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WAI-WEBCONTENT (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- W3C. Comprender las WCAG 2.0. Available online: http://www.sidar.org/traducciones/wcag20/es/comprender-wcag20/conformance.html (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Muñoz, R.O.; Montoto, C.O. Accesibilidad Web. In WCAG 2.1 de Forma Sencilla; Itákora Pres: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 1–264. [Google Scholar]

- W3C. Mobile Accessibility: How WCAG 2.0 and Other W3C/WAI Guidelines Apply to Mobile. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/mobile-accessibility-mapping/#contrast (accessed on 1 June 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).