Abstract

Cloud computing has rapidly penetrated enterprise and user computing markets with three prominent service models: software as a service (SaaS), platform as a service (PaaS), and infrastructure as a service (IaaS). Cloud computing has also proven to be one of the most important environmentally sustainable technological innovations in the year of Industrial Revolution 4.0. While SaaS and IaaS are the two largest revenue generating services in the cloud service market, the pricing and profit generating mechanisms of the SaaS and IaaS providers have not yet been well understood. Unless the SaaS providers’ profit-maximizing decision is considered, any pricing decision by the IaaS providers is likely to be suboptimal. Hence, this paper proposes a Stackelberg game pricing decision model with the aim of maximizing the profit of the IaaS provider, given the best response of the SaaS provider. This paper develops an analytical closed-form solution to the pricing problem and presents sensitivity analyses to give valuable insights into the pricing dynamics and negotiation between the SaaS provider and IaaS provider. Finally, implications of these findings and future research directions are discussed.

1. Introduction

Cloud computing is one of the most paradigm-shifting Internet technology developments. With the development of hyper-speed Internet, cloud computing has become the central computing resource in almost every industry. Cloud computing makes it possible for companies to use IT resources as a service without upfront investment costs, and is expected to grow at a rapid speed primarily because of the flexibility to satisfy fluctuating demands [1,2]. Cloud computing has the potential to shift business to business (B2B) e-commerce toward more open, loosely-coupled electronic exchanges [3]. Additionally, countries around the world have been adopting new energy-efficient technologies that help create a more sustainable economy [4]. Cloud computing is energy efficient and an environmentally sustainable innovation that offers rich opportunities for innovating existing services and introducing creative new ones [5]. Cloud computing also helps companies achieve rapid process and product innovations designed for sustainable economic, social, and environmental growth [6].

The pricing clarity and transparency to cloud customers are two of the key success factors for the growth of cloud services [7]. Cloud customers often commit more for services than needed when the cloud providers’ pricing strategies are designed to maximize their own profit and revenue [8]. However, proper pricing can not only increase their profit but also help customers purchase cloud services efficiently [9]. To meet the fluctuating demands of cloud customers created by peak and seasonal demands, cloud providers charge services via on-demand pricing and reserve pricing [10]. The software industry is also heavily affected by cloud computing. Moving from on-premise software to cloud-based SaaS affects all business model components including the customer value proposition, resource base, value configuration, and financial flows [11].

According to Gartner [12], SaaS will remain the largest market segment in the future. The second-largest market segment is IaaS, which will reach $50 billion in 2020. While major cloud providers provide all types of services, many SaaS providers depend on the IaaS providers. Many specialized niche software applications have been developed by relatively small/medium-sized software vendors and have been offered as SaaS with infrastructure support from IaaS providers. For example, HubSpot’s CRM is hosted on Amazon Web Services (AWS) and the Google Cloud Platform (GCP) [13].

SaaS provides the opportunity to not only lower cost, but also deliver software applications to end-users over the Internet, providing a much more flexible experience regarding time and location of access [14]. While SaaS providers are software providers to users, most of them are customers of IaaS providers, which provide infrastructure hosting services to customers. Pricing and performance of IaaS are important factors for the sustainable revenues and profits of the SaaS providers and the IaaS providers. Despite potential benefits of mixing the on-demand instance, spot instance, and reserved instance under a highly fluctuating demand, there has been no study on how the pricing of the IaaS provider affects the SaaS provider’s purchasing decision on the three pricing options.

In light of the gap in the prior studies, this paper investigates the pricing and purchasing dynamics between SaaS providers and IaaS providers. This paper develops a Stackelberg game pricing decision model in which the IaaS provider is a leader and the SaaS provider is a follower in the pricing and purchasing decisions. In Section 2, prior studies are reviewed. In Section 3, a Stackelberg game pricing decision model is proposed which maximizes the profit of the IaaS provider given the best response of the SaaS provider. An optimal solution to the pricing problem is derived using a backward induction process and the Newton Raphson root-finding algorithm. In Section 4, sensitivity analyses of pricing decisions are conducted. In Section 5, implications for researchers and managers, limitations of the study, and future research directions are discussed.

2. Related Works

This section reviews prior works on pricing models with the aim of assessing the current status of research and practices and identifying gaps. While there exist pricing studies in the software industry [15], pricing and profit management between the IaaS providers and the SaaS providers has not been well investigated. Research on business-to-business (B2B) marketing emphasizes the importance of pricing for every firm’s profitability and long-term survival [16]. Likewise, the sustainable success of cloud providers in large part depends on achieving profit maximization through superior cloud services and competitive prices. Market-based, value-based, and cost-based approaches are the three main pricing approaches that have been widely used [17]. Table 1 summarizes pricing approaches, pricing models, pricing schemes, research methods, and the key findings of the studies.

Table 1.

Pricing Approaches, Pricing Models, Pricing Schemes, Research Methods, and Key Findings of Select Studies.

A number of researchers apply value-based pricing to cloud services. A reinforcement learning (RL)-based dynamic cloud pricing scheme is proposed to optimize both cloud provider’s profit and the costs of users with distinct personalities [18]. A stochastic dynamic program is developed to solve the cloud provider’s pricing problem [19,20]. Game theory is also used to analyze pricing schemes [21]. Lu et al. [22] propose a QoS-based auction approach that can efficiently allocate resources according to customers’ QoS preferences. Song and Guérin [23] focus on exploiting heterogeneity across jobs in terms of value and sensitivity to execution delay, with a joint distribution that determines their relationship across the user population. Wu et al. [24] demonstrate that the extrinsic values of the cloud services would not only become one of the competitive advantages for cloud providers to lead the cloud market but also increase the profit margin. Dimitri [25] presents a mathematical model to determine the relevant parameters of pricing schemes for on-demand instances, reserved instances, and spot instances to maximize the provider’s revenue.

Cost-based pricing is a pricing approach where the actual cost of producing and offering the cloud service unit such as virtual machine (VM) instances is the basis for prices. When the cloud providers pursue cost-based pricing as their competitive advantage, they try to become the lowest cost provider with a good quality service and the effort is made to reduce cost as much as possible. An in-depth understanding of the cost components of cloud services is necessary for cost-based pricing [26]. Cost categories of cloud services include data centers, services, hardware, software, network, and development. The specific weights of the individual cost elements would vary, depending on the types of the cloud services such as SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS.

Lee [26] develops a Stackelberg game decision model from the perspectives of both the IaaS providers and the corporate cloud customers for the IaaS provider’s profit maximization, given the best response of the corporate cloud customers to minimize their cloud cost. The analytical results show the effectiveness of the decision model in achieving a sustainable profit for both the IaaS providers and the corporate cloud customers, and that discrimination pricing for multiple customers generates a slightly larger profit than a uniform price. Nasiriani et al. [27] note that the costs incurred by cloud providers for the operation of their datacenters are often determined in large part by the peak demands. Assessing the cost incurred at the peak demands, they develop a pricing scheme to more fairly distribute a cloud’s costs among its tenants.

Market-based pricing is competition-based as the demand and supply of cloud services determines the price. Market-based pricing applies when services are commodity-type or there exist many buyers and sellers in a market. Rohitratana and Altmann [28] use simulation to investigate market-based pricing in SaaS and perpetual software (PS) license markets. They find that the demand-driven pricing scheme is best, but difficult to use due to imperfect knowledge about customers and competitors. As an alternative, they suggest penetration pricing and price skimming as an easy-to-implement solution. Jin et al. [29] also use simulation to develop a dynamically optimized fine-grained pricing scheme to solve the partial usage waste issue with a virtual machine-maintenance overhead. They show the proposed fine-grained pricing scheme increases social welfare significantly compared to the classic coarse-grained hourly pricing scheme.

Game theory has been widely used in many disciplines, such as economics, computer science, and political science, to develop mathematical models of interactions among rational decision-makers and measure payoffs at the equilibrium if any exists. Game theory has also been applied to study pricing and payoffs among cloud providers and customers as rational decision-makers. Pal and Hui [30] develop a non-cooperative game model where public cloud providers compete on price and quality of service (QoS) levels related to a particular application type and show the existence and convergence of price in Nash equilibria. Tang and Chen [31] develop a Stackelberg game model to investigate pricing in the IaaS provider market with a set of SaaS providers and derive the conditions under which there exists a unique Nash equilibrium. Chen, Lee, and Moinzadeh [32] also use game theory to evaluate reserved pricing and on-demand pricing. They show that customers with lower demand volatility would prefer reserved pricing, while those with higher demand volatility would prefer on-demand pricing.

Spot pricing is a dynamic market-based pricing scheme to sell computing capacity. The spot instances are interruptible if other prioritized instances require access to the computing resources. Huang, Kauffman, and Ma [33] investigate whether interruptible spot instances are valuable to cloud providers. They note that the presence of interruptions serves as a quality differentiator between spot instance services and reserved instance services. A dynamic demand-based pricing model for on-demand IaaS cloud service instances is developed to determine the price of provisioning the cloud services by considering the provider’s and users’ utility concurrently [34]. IaaS providers are offering various types of spot services with different service names, such as Amazon EC2 spot instances [35], Google’s preemptible virtual machines [36], and Microsoft Azure’s low-priority virtual machines [37].

The review of prior studies on cloud pricing reveal that the majority of studies focus on value-based pricing. Value-based pricing is used to charge customers according to the value created for the customer [38]. Value-based pricing is a potentially powerful tool to capture a fair share of the value created [39] and to gain a competitive advantage [40]. Based on the perceived value customers are willing to pay for cloud services, cloud providers will set the price to maximize their profit [41]. However, while customers’ perceived value is the fundamental basis for all marketing activities [42], subjective value perception makes the valuation of the service very challenging.

The cost-based pricing model is the least investigated. On-demand, spot, and reserved instance pricing are widely used pricing schemes for either the goal of revenue or profit maximization. Most studies develop mathematical models to analyze the pricing dynamics. Most studies focus on the pricing of IaaS. Based on the literature review, it was clear that pricing and profit management among different types of cloud providers have not received a proper attention. For example, pricing and profit interactions between IaaS providers and SaaS providers have not been investigated.

This gap in the prior studies motivates us to develop a Stackelberg game pricing decision model in which the IaaS provider is a leader and the SaaS provider is a follower in the pricing and purchasing decisions. The Stackelberg game was originally developed by Heinrich Freiherr von Stackelberg in 1934 in the context of static competition games [43]. In the Stackelberg game, the leader announces his/her decision first to maximize the leader’s profit given the knowledge of the best response of the follower. Next, the follower observes the leader’s decision and makes the best response to it. In the cloud service market, pricing and purchasing interactions between the IaaS provider and the SaaS provider can be captured through the Stackelberg game. The IaaS provider is the leader who decides on the price to maximize the leader’s profit with the knowledge of the best response of the SaaS provider who is the follower. Once the SaaS provide learns the price of the IaaS provider, he/she makes the best purchasing decision.

This type of relationship is quite commonly observed in the cloud market where the IaaS provider has a dominant market position and a small/medium-sized SaaS provider has few choices of reliable IaaS providers. In addition, major IaaS providers are willing to negotiate mutually agreeable prices with strategic partners. For example, Amazon AWS is known to negotiate service prices with large corporate customers for large volume cloud services through the AWS Enterprise Discount Program (EDP) [44]. Understanding the pricing and profit dynamics between the SaaS provider and the IaaS provider and negotiating mutually agreeable pricing will create a sustainable business relationship.

3. Determining Optimal Pricing of IaaS with a Stackelberg Game

This section discusses the development of a pricing and profit management model based on a Stackelberg game in which the IaaS provider determines the price of IaaS, given the knowledge of the best response of the SaaS provider to the prices of the three instance types. The IaaS provider considers the best response functions of the SaaS provider through a backward induction process. Currently, the three popular pricing schemes are reserved instance pricing, on-demand pricing, and spot instance pricing. This model helps cloud providers understand how the pricing of the IaaS provider affects the SaaS provider’s purchasing decision on the three pricing options. The nomenclature used for the Stackelberg game pricing and profit management models is given at the end of this paper.

In the following, the decision model of the SaaS provider is discussed first and the decision model of the IaaS provider follows.

3.1. SaaS Provider’s Decision Model

The SaaS provider’s decision is to choose the best mix of the reserved instances and autoscaling group of the on-demand instances and the spot instances to maximize his/her profit given the prices of the three instance types. Autoscaling monitors the computing demand of SaaS users and automatically adjusts capacity to maintain steady, predictable performance at the lowest possible cost. While a proper autoscaling of the on-demand instances and the spot instances gives a reduced expense for the SaaS provider, spot instances suffer from frequent service interruptions when the resources are short and allocated to other tasks. The SaaS provider chooses their autoscaling ratio between the on-demand instances and the spot instances. While the price of the spot instance is typically 10% of the price of the on-demand instance, the interruption rate of the spot instances should be taken into account in determining the autoscaling ratio of the on-demand instances and the spot instances. For example, assume that the spot instance has a 10% interruption rate. The autoscaling group of 50% for spot instances and 50% for on-demand instances would result in a 5% overall interruption rate for the autoscaling group.

Given the price differential, the SaaS provider attempts to maximize his/her profit with an optimal mix of the reserved instances, the on-demand instances, and the spot instances. The purchase of the on-demand instances and the spot instances is made in an autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance (e.g., 50% for the on-demand instances and the remaining 50% for the spot instances). The optimal number of reserved instances, s*, and the autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance, a*, are obtained from the following profit function of the SaaS provider:

where is the SaaS subscription revenue, is the total cost for the IaaS reserved instances, is the interruption rate for the autoscaling group (i.e., for both the on-demand instances and the spot instances), is the total cost of the on-demand instances, is the total cost of the spot instances, and is the revenue loss related to a service outage due to the interruption of the spot instances.

In the SaaS providers’ decision model, the number of reserved instances, s, and the autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance, a, are the decision variables. Equation (1) assumes that if the actual computing need exceeds the number of the reserved instances, the autoscaling group of the on-demand and spot instances is used to meet the shortage of the IaaS instances, . However, if the actual computing need is lower than the number of the reserve instances purchased, there will be underutilized reserved instances, , unless the idle portion is allowed to be sold to the cloud marketplace. In this model, an exponential distribution of the computing demand is assumed. However, it is possible to extend the model with other types of probabilistic distributions.

Applying integration techniques, Equation (1) is transformed into Equation (2).

Differentiating in terms of s leads to:

Then, the optimal number of IaaS reserved instances, s*, is:

Next, differentiating in terms of a leads to:

Then, the optimal autoscaling weight of the on-demand instances, a*, is:

Equation (6) shows that a* is independent of the optimal number of reserved instances, s*. Equation (7) is the second derivative of Equation (2) in terms of s. Given a is fixed, the second derivative is always negative for positive values of s, indicating concave down with a local maximum at s*.

Equation (8) is the second derivative of Equation (2) in terms of a. The second derivative is negative, indicating concave down, for all values of a with the maximum at a*.

3.2. IaaS Provider’s Decision Model

Depending on the way the SaaS provider chooses the autoscaling group and the reserve instances, the IaaS provider will offer different prices for the instance types to maximize his/her profit. Currently, the price of the on-demand instance is comparable among IaaS cloud providers, but the discount rates of their reserved instances vary widely. For example, Microsoft offers customers 40–70% discount for one- or two-year reserved instances compared to the price of the on-demand instance. Amazon offers a 75% discount to some of EC2’s reserved instance compared to the price of their on-demand instance. In this decision model, the IaaS provider makes a pricing decision on the reserve instance with the knowledge of the best response of the SaaS provider, while fixing the price of the on-demand instance. Discounting the price of the reserved instance would encourage the SaaS provider to purchase more reserved instances over the autoscaling group up to the point where the marginal profit from the use of the reserved instance is equal to marginal profit from the use of the autoscaling group.

For the IaaS provider, finding the optimal price of the reserved instance is a complicated task, since the IaaS provider needs to know the best response of the SaaS provider. This situation is modeled as a Stackelberg game in which the IaaS provider is the leader, whose strategy is determining the optimal pricing of the reserved instance, k*, and the SaaS provider is the follower whose strategy is determining the optimal number of the reserved instances, s*, and the optimal autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance, a*. The Stackelberg equilibrium is defined as:

Applying integration techniques, Equation (9) is transformed into Equation (10).

To get the optimal price of the IaaS provider, differentiate with respect to k:

Note that .

Equation (12) is the second derivative of Equation (10) in terms of k. Since , it is proven that there is a maximum profit in the positive price range.

Since there is no closed-form optimal value of k, the Newton Raphson root-finding algorithm is used to find k* of the IaaS provider’s Stackelberg game.

3.3. An Illustration of the Stackelberg Equilibrium for the SaaS Provider and the IaaS Provider

Table 2 lists assumptions for an illustration of the Stackelberg equilibrium with the IaaS provider as the leader and the SaaS provider as the follower. Table 3 shows the three decision variables and their optimal values.

Table 2.

Assumptions for the Illustration.

Table 3.

Decision Variables and Their Optimal Values.

Applying the Newton Raphson method and Stackelberg game’s backward induction process, the optimal decision by the IaaS provider for the optimal reserved instance price, k*, is $246.67 which is about a 39% discount from the price of the on-demand instance. Then, the best response of the SaaS provider for the optimal number of the reserved instances, s*, is 919. The best response of the SaaS provider for the optimal autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance, a*, is 0.58333 determined by .

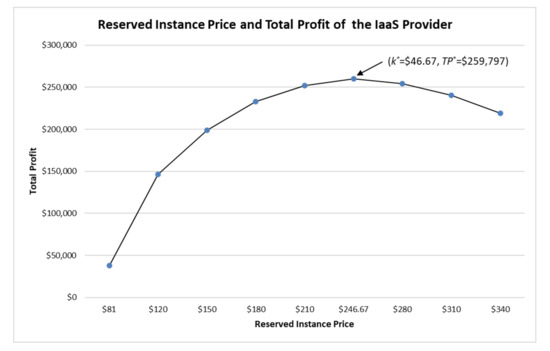

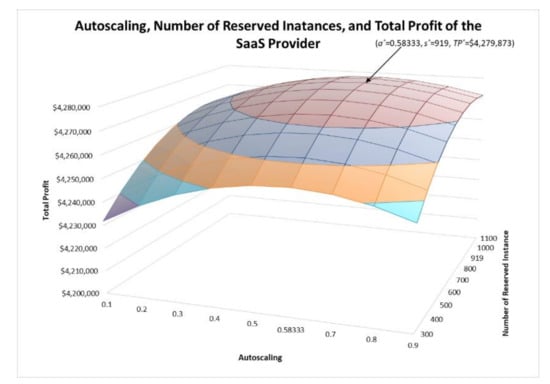

Figure 1 shows that the total profit function of the IaaS provider is concave down with the optimal profit at the price of $246.67 for the reserved instance, given the SaaS provider’s best response. The best response (s* = 919, a* = 0.58333) of the SaaS provider is shown in Figure 2, given the price of $246.67 for the reserved instance. At the Stackelberg equilibrium, the total profit of the IaaS provider is $259,797 and the total profit of the SaaS provider is $ 4,279,873. Deviating from the Stackelberg equilibrium would render either provider a less total profit.

Figure 1.

Reserved Instance Price and the Total Profit of the IaaS Provider.

Figure 2.

Autoscaling Weight of On-demand by the SaaS Provider and the Total Profit.

It is noted that in the Stackelberg game, the leader has an advantage over the follower. The follower makes the best response given the leader’s strategy. While the Stackelberg game shows there exists an equilibrium between the two providers, the leader may want to deviate from the equilibrium at his own expense to have a sustainable strategic relationship with the follower. For example, despite the reduced total profit, the IaaS provider may want to offer to the SaaS provider a deeper price discount of the reserved instance in order to build a strategic partnership (e.g., a strategic partnership between HubSpot and Amazon AWS). Figure 1 shows that a price decrease (i.e., to the left of the optimal price) will lower the total profit of the IaaS provider. However, the price decrease of the reserved instance will increase the total profit of the SaaS provider. Raising the price of the reserved instance beyond $246.67 (i.e., to the right of the optimal price) will decrease not only the total profit of the IaaS provider, but also that of the SaaS provider. The Stackelberg game proves to be a powerful tool for the IaaS provider in negotiating volume discounts with major SaaS providers.

4. Sensitivity Analyses of Pricing Decisions

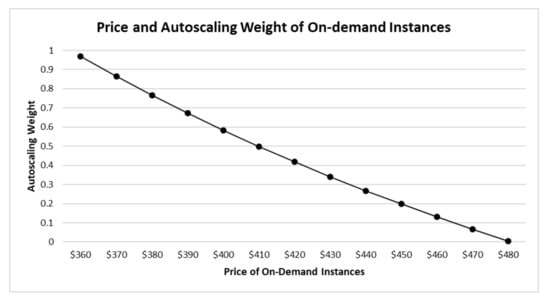

This section conducts sensitivity analyses of the Stackelberg game to understand the model’s behavior when changing the parameter values of the decision models. The parameter values in Table 2 are used in the sensitivity analyses. Figure 3 shows the impact of the price of the on-demand instance on the autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance. The result shows that the increase of the price of the on-demand instance lowers the autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance. The autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance is nearly 100% at $360 for the on-demand instance and declines to nearly 0% at $480. A further analysis reveals the upper bound price to include the on-demand instance to the autoscaling group is $480.76.

Figure 3.

Price of On-demand Instance and Autoscaling Weight of On-demand Instances.

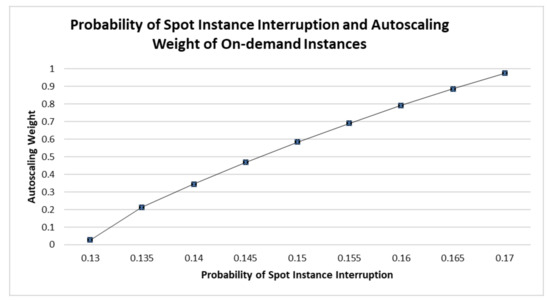

On the other hand, an increase of the probability of spot instance interruptions increases the autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance (Figure 4). The autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance goes down to nearly 0% at a 0.13 probability of a spot instance interruption and increases to nearly 100% at a probability 0.17. Further analysis reveals a lower bound probability of a spot instance interruption to include any amount of on-demand instance to the autoscaling group is 0.12766.

Figure 4.

Probability of Spot Instance Interruption and Autoscaling Weight of On-demand Instances.

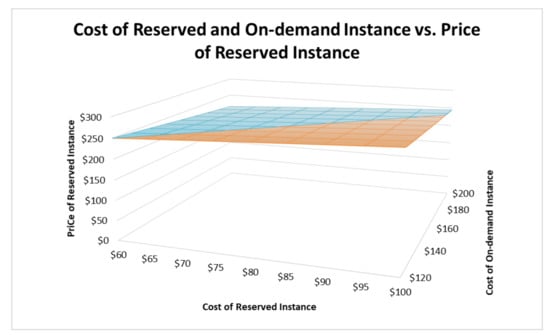

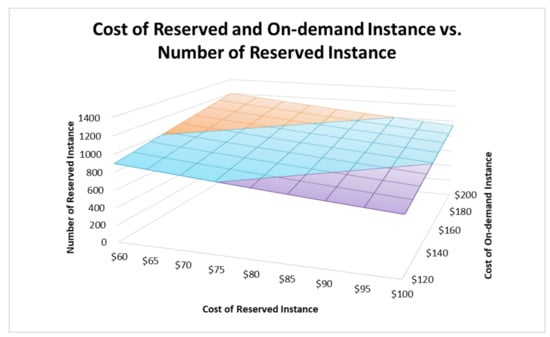

This section continues the sensitivity analyses by varying values of the IaaS providers’ cost per reserved instance, c, and the cost per on-demand/spot instance of the IaaS provider, g. When there is an increase in the cost of the reserved instance and a decrease in the cost of the on-demand instance, the IaaS provider should increase the price of the reserved instances (Figure 5), and the SaaS provider should decrease the number of the reserved instances, but increase the autoscaling group (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Costs of Reserved Instance and On-demand Instance vs. Price of Reserved Instance.

Figure 6.

Costs of Reserved Instance and On-demand Instance vs. Number of Reserved Instance.

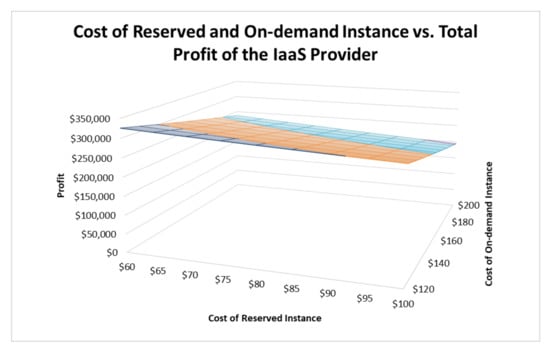

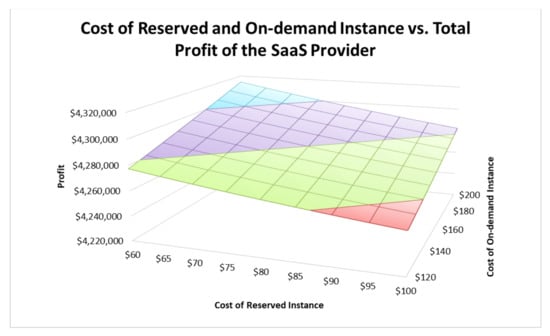

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show how the changes in the cost of the reserved instance and the cost of the on-demand instance affect the profits of the IaaS provider and the SaaS provider. As the cost of the reserved instance and the cost of the on-demand instance increase, the optimal total profit of the IaaS provider decreases due to the declining margin of the cloud services. However, contrary to conventional wisdom, while an increase in the cost of the reserved instance decreases the profit of the SaaS provider, an increase in the cost of the on-demand instance increases the profit of the SaaS provider. This is explained by the fact that an increase in the cost of the on-demand instance encourages the IaaS provider to sell more reserved instances by lowering the price of the reserved instance, given the price of the on-demand instance is fixed. Therefore, the profit of the SaaS provider increases, but the profit of the IaaS provider decreases. These results provide valuable insights on the impact of the costs of IaaS on the profits of both providers.

Figure 7.

Cost of Reserved Instance and On-demand Instance vs. Total Profit of IaaS Provider.

Figure 8.

Cost of Reserved Instance and On-demand Instance vs. Total Profit of SaaS Provider.

5. Conclusions

While a well-developed pricing strategy increases cloud providers’ profits and revenues, most previous studies focus on the technological aspects of cloud computing such as resource allocation and scheduling. However, understanding pricing dynamics between different types of cloud providers is critical to improving their profits and revenues. For example, without taking into account the SaaS providers’ profit-maximizing decision, any pricing decision of the IaaS providers is likely to be suboptimal. Based on the literature review on pricing of cloud services, this paper proposes a Stackelberg game pricing decision model. In the proposed Stackelberg game, the IaaS provider identifies the optimal price of the reserved instance price given the knowledge of the SaaS provider’s best response to the prices of the reserved instance, on-demand instance, and spot instance. The Stackelberg equilibrium was derived from the game pricing decision model.

This study found that for the SaaS provider, the optimal autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance is independent of the optimal number of reserved instances. The price increase of the on-demand instance lowers the autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance. On the other hand, an increased probability of spot instance interruptions increases the autoscaling weight of the on-demand instance. When there is an increase in the cost of the reserved instance and a decrease in the cost of the on-demand instance, the IaaS provider should increase the price of the reserved instances. Contrary to conventional wisdom, while a cost increase of the reserved instance decreases the profit of the SaaS provider, a cost increase of the on-demand instance increases the profit of the SaaS provider.

This paper has a few implications for cloud providers. First, cloud providers need to understand complex interactions among costs and prices of multiple service categories. The cost increase of the on-demand instance encourages the IaaS provider to sell more reserved instances by lowering the price of the reserved instance, given the price of the on-demand instance is fixed. Therefore, the profit of the SaaS provider increases due to the price decrease of the reserved instance, but the profit of the IaaS provider decreases. Second, SaaS providers need to carefully decide the autoscaling weight between the on-demand instance and the spot instance. They need to measure the complex interactions among the on-demand price, the spot price, and the interruption rate of the spot instances. Third, the insights gained from this Stackelberg game decision model can also be used for negotiating volume discounts with the SaaS provider. For example, if the IaaS provider wants to deviate from the Stackelberg equilibrium at his own expense to have a sustainable strategic relationship with the SaaS provider, the Stackelberg equilibrium of the proposed decision model provides a starting point for the price negotiation. The IaaS provider needs to decide how much discount is necessary beyond the Stackelberg equilibrium price in order to have s sustainable relationship with the SaaS provider in a competitive market.

Like many studies, this study has limitations. First, it is noted that the successful use of these models would require accurate estimation of the model parameters and the use of various modeling techniques. Future research may explore various estimation techniques of the model parameters to develop more realistic models. Second, future studies need to investigate additional variables for the pricing model. For example, different IaaS providers employ different pricing schemes. Each SaaS may have a different level of QoS preference and a different willingness to pay for the service (i.e., reservation price). Future research may include these variables for model enhancement. The SaaS is a useful application for inter-organizational supply chain management (SCM). It would be interesting to investigate how an organization’s technological maturity and its capabilities of SaaS SCM affect their adoption.

Author Contributions

In Lee is the sole author. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| x | an actual SaaS demand in terms of IaaS instances |

| λe−λx | an exponential probability distribution function for the demand of IaaS instances |

| 1-e−λx | a cumulative exponential distribution function for the demand of IaaS instances |

| 1/λ | mean value of the demand of IaaS instances |

| n | the number of SaaS subscriptions |

| m | the subscription fee per SaaS subscription |

| k | price per reserved instance; decision variable of the IaaS provider |

| s | the number of the reserved instances purchased by the SaaS provider; decision variable of the SaaS provider |

| a | autoscaling weight of the on-demand instances; decision variable of the SaaS provider |

| (1-a) | autoscaling weight of spot instance |

| p | price per on-demand instance |

| o | discounted rate |

| o·p | price per spot instance |

| r | the probability of spot instance interruption |

| c | cost per reserved instance |

| g | cost per on-demand and spot instance |

| (1-a)·r | the expected rate of interruption for the entire autoscaling group |

| n·m·λ | revenue loss per instance of spot instance interruption |

References

- Makela, T.; Luukkainen, S. Incentives to apply green cloud computing. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 8, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Basu, S.; Sharma, M. Pricing Infrastructure-as-a-Service for online two-sided platform providers. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2014, 13, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, L. The logic of electronic hybrids: A conceptual analysis of the influence of cloud computing on electronic commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cheng, Y.; Awan, U.; Ahmad, S.; Tan, Z. How do technological innovation and fiscal decentralization affect the environment? A story of the fourth industrial revolution and sustainable growth. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Warren, D.; Mathiassen, L. Cloud-based business services innovation: A risk management model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U. Steering for sustainable development goals: A typology of sustainable innovation. In Innovation and Infrastructure. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhardt, C.; Anandasivam, A.; Blau, B.; Meini, T.; Michalk, W.; Stosser, J. Cloud computing—A classification, business models, and research directions. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2009, 1, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mireslami, S.; Rakai, L.; Far, B.H.; Wang, M. Simultaneous cost and QoS optimization for cloud resource allocation. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2017, 14, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Leung, V.C.M.; Shami, A. A fairness-aware pricing methodology for revenue enhancement in service cloud infrastructure. IEEE Syst. J. 2017, 11, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppel, E.; Roth, S. Consequences of usage-based pricing in industrial markets. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2015, 14, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boillat, T.; Legner, C. From on-premise software to cloud services: The impact of cloud computing on enterprise software vendors′ business models. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 8, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner. Gartner Forecasts Worldwide Public Cloud Revenue to Grow 17% in 2020. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2019-11-13-gartner-forecasts-worldwide-public-cloud-revenue-to-grow-17-percent-in-2020 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Hotspot.com HubSpot Cloud Infrastructure Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: https://knowledge.hubspot.com/account/hubspot-cloud-infrastructure-frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Gonçalves, V.; Ballon, P. Adding value to the network: Mobile operators′ experiments with Software-as-a-Service and Platform-as-a-Service models. Telemat. Inform. 2011, 28, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrankić, I.; Bach, M.P.; Krpan, M. Stackelberg equilibrium of the client and the producer of embedded software. Bus. Syst. Res. Int. J. Soc. Adv. Innov. Res. Econ. 2014, 5, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancioni, R. A strategic approach to industrial product pricing: The pricing plan. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2005, 34, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterhuber, A. Customer value-based pricing strategies: Why companies resist. J. Bus. Strategy 2008, 29, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, P.; Zhou, J.; Chen, M.; Wei, T. Personality-guided cloud pricing via reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahandideh, H.; Drew, J.W.; Balestrieri, F.; McCardle, K. Individualized pricing for a cloud provider hosting interactive applications. Serv. Sci. 2020, 12, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, B. Dynamic cloud pricing for revenue maximization. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2013, 1, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.-H.; Choi, B.-S. Service models and pricing schemes for cloud computing. Clust. Comput. 2014, 17, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Xu, L.D. Pricing the cloud: A QoS-based auction approach. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 14, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Guérin, R. Pricing (and bidding) strategies for delay differentiated cloud services. ACM Trans. Econ. Comput. 2020, 8, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Nadjaran Toosi, A.; Buyya, R.; Ramamohanarao, K. Hedonic pricing of cloud computing services. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitri, N. Pricing cloud IaaS computing services. J. Cloud Comput. Adv. Syst. Appl. 2020, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. Pricing schemes and profit-maximizing pricing for cloud services. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2019, 18, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiriani, N.; Wang, C.; Kesidis, G.; Urgaonkar, B.; Chen, L.Y.; Birke, R. On fair attribution of costs under peak-based pricing to cloud tenants. ACM Trans. Model. Perform. Eval. Comput. Syst. 2016, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohitratana, J.; Altmann, J. Impact of pricing schemes on a market for software-as-a-service and perpetual software. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2012, 28, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Di, S.; Shi, X. Towards optimized fine-grained pricing of IaaS cloud platform. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2015, 3, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Hui, P. Economic models for cloud service markets: Pricing and capacity planning. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2013, 496, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Chen, H. Joint pricing and capacity planning in the IaaS cloud market. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2017, 5, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lee, H.; Moinzadeh, K. Pricing schemes in cloud computing: Utilization-based vs. reservation-based. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 28, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kauffman, R.J.; Ma, D. Pricing strategy for cloud computing: A damaged services perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 78, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, S.; Kumar, H.; Kaushal, S.; Sangaiah, A.K. Genetic algorithm-based cost minimization pricing model for on-demand IaaS cloud service. J. Supercomput. 2020, 76, 1536–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazon. Amazon EC2 Spot Instances. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/cn/ec2/spot/pricing (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Google. Google Preemptible Virtual Machines. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/preemptible-vms (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Microsoft. Use Low-Priority VMs with Batch. Available online: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/batch/batch-low-pri-vms (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Reen, N.; Hellström, M.; Wikström, K.; Perminova-Harikoski, O. Towards value-driven strategies in pricing IT solutions. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2017, 16, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterhuber, A. Towards value-based pricing—An integrative framework for decision making. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Zbaracki, M.J.; Bergen, M. Pricing process as a capability: A resource-based perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Buyya, R.; Ramamohanarao, K. Cloud pricing models: Taxonomy, survey, and interdisciplinary challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppaniemi, M.; Karjaluoto, H.; Saarijarvi, H. Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: The role of willingness to share information. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Stackelberg, H. The Theory of the Market Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Chapel, J. How to Use an AWS EDP for Discounted Cloud Resources. Available online: https://www.parkmycloud.com/blog/aws-edp/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).