Abstract

Today, hepatitis C virus infection affects up to 1.5 million people per year and is responsible for 29 thousand deaths per year. In the 1970s, the clinical observation of unclear, transfusion-related cases of hepatitis ignited scientific curiosity, and after years of intensive, basic research, the hepatitis C virus was discovered and described as the causative agent for these cases of unclear hepatitis in 1989. Even before the description of the hepatitis C virus, clinicians had started treating infected individuals with interferon. However, intense side effects and limited antiviral efficacy have been major challenges, shaping the aim for the development of more suitable and specific treatments. Before direct-acting antiviral agents could be developed, a detailed understanding of viral properties was necessary. In the years after the discovery of the new virus, several research groups had been working on the hepatitis C virus biology and finally revealed the replication cycle. This knowledge was the basis for the later development of specific antiviral drugs referred to as direct-acting antiviral agents. In 2011, roughly 22 years after the discovery of the hepatitis C virus, the first two drugs became available and paved the way for a revolution in hepatitis C therapy. Today, the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection does not rely on interferon anymore, and the treatment response rate is above 90% in most cases, including those with unsuccessful pretreatments. Regardless of the clinical and scientific success story, some challenges remain until the HCV elimination goals announced by the World Health Organization are met.

1. Introduction

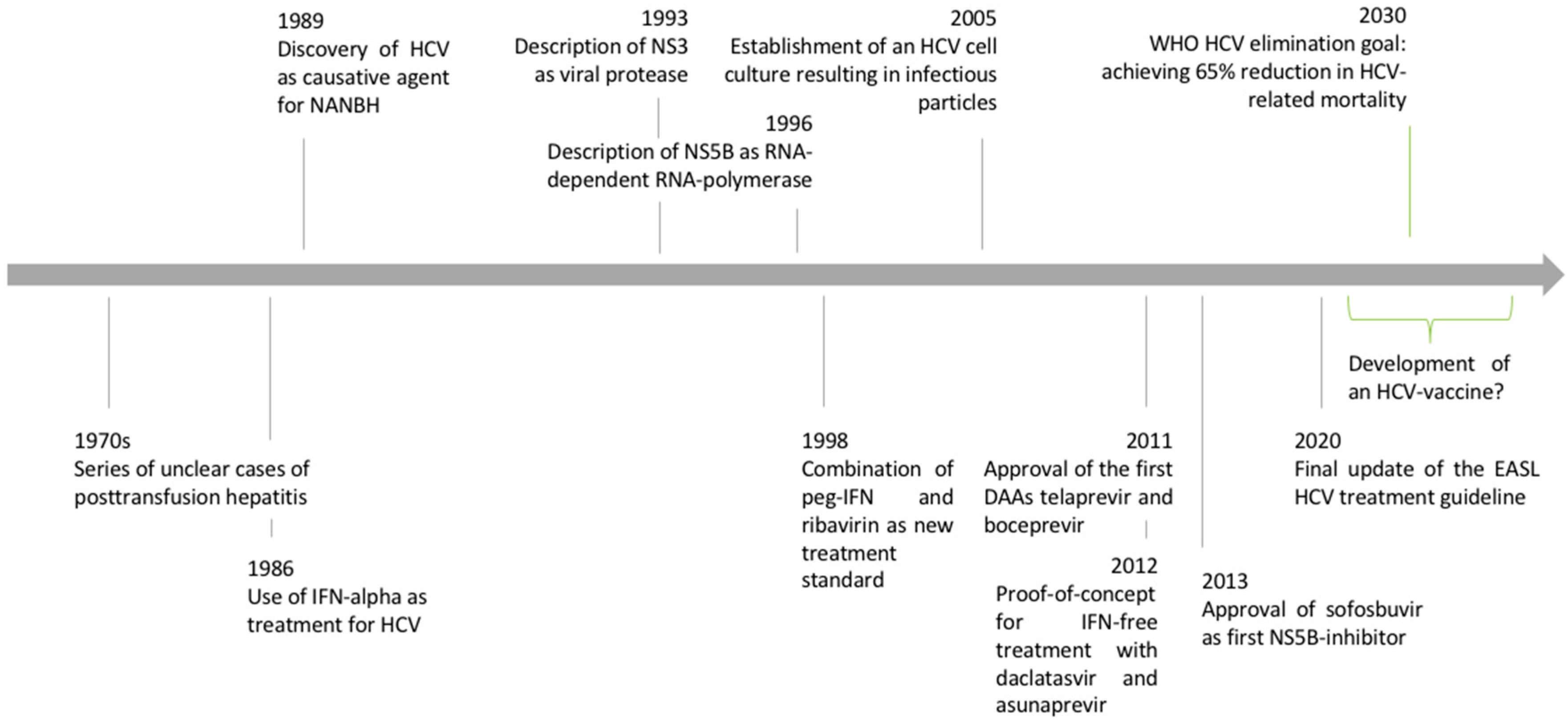

The history of hepatitis C research is a success story where the interplay of applied clinical research and basic science led to the discovery of a new virus and the establishment of a curative treatment within little more than twenty years (Figure 1). The tremendous impact of hepatitis C virus (HCV) research became even clearer when HCV researchers were awarded the 2016 Lasker award and the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine [1]. The scientific advances in HCV research were based on a “bedside-to-bench-to-bedside” approach that can serve as a role model for other fields of biomedical research. In the following article, we review the important steps of the HCV discovery and the characterization of viral properties that finally led to the development of direct-acting antiviral agents as cures for HCV infection.

Figure 1.

Timeline of HCV discovery and advances in clinical and basic virologic research. Adapted from [2].

1.1. Discovery of the Hepatitis C Virus

In the 1970s, transfusion-associated cases of hepatitis were frequently reported, resulting in the descriptive term of post-transfusion hepatitis. Soon, it was found that known hepatotropic viruses such as hepatitis A and B viruses were not responsible for the new type of hepatitis. Consequently, it was named non-A-non-B hepatitis (NANBH) [3]. After this clinical observation of NANBH, years of extensive basic research followed. In 1989, two papers were published in the same Science edition that described the isolation of viral cDNA clones [4] that allowed for the identification of NANBH antibodies, finally resulting in the discovery of HCV [5].

1.2. Epidemiology and Natural History of Hepatitis C Virus Infection

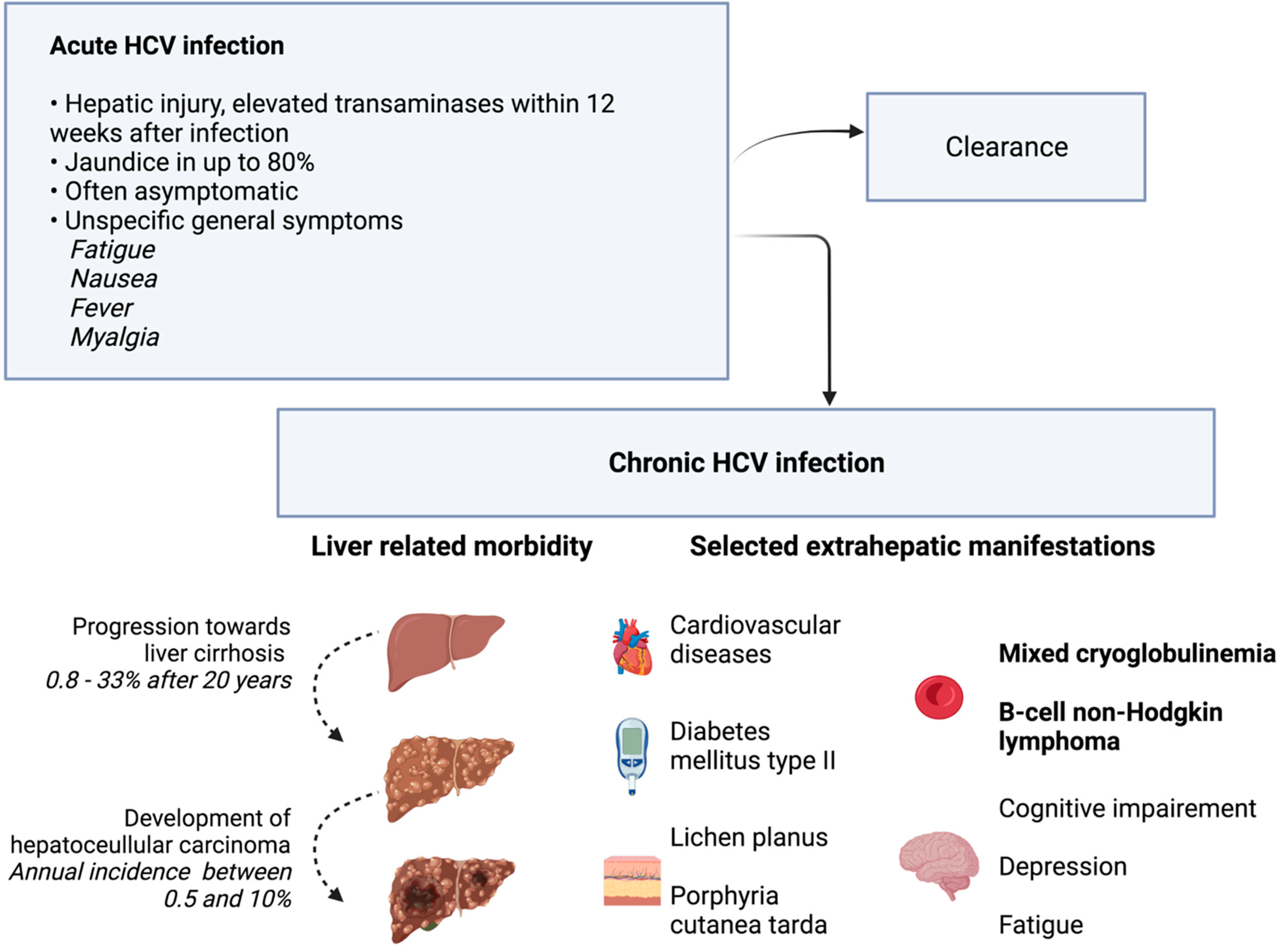

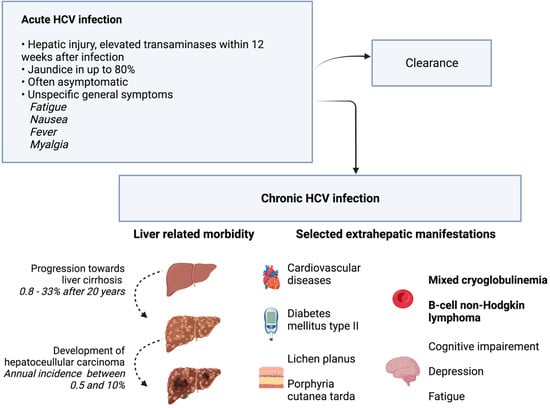

Acute hepatitis develops within four to twelve weeks after HCV infection [6]. A rise in bilirubin leading to clinically visible jaundice is possible. However, the symptoms are often unspecific, and asymptomatic disease courses are common. Consequently, individuals can be infected unknowingly. In up to 80% of cases, acute hepatitis C develops into chronic HCV infection [7]. Chronic hepatitis with ongoing hepatic damage bears the risk of liver cirrhosis. In a large meta-analysis, liver cirrhosis was present in 16% of individuals after 20 years of chronic HCV infection. Risk factors for the development of liver cirrhosis include the presence of chronic hepatitis with elevated ALT levels, large amounts of alcohol intake, or coinfection with the hepatitis B virus [7]. In addition, chronic HCV infection is a major risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Typically, HCC develops in cirrhotic liver tissue. Estimates of annual HCC incidence range from 0.5% to 10% [8]. In addition to hepatic involvement, HCV infection can also be linked to extrahepatic manifestations, as summarized in Figure 2. However, a causal relationship has not been demonstrated for all the extrahepatic symptoms that have been described in the past [9]. HCV is transmitted via parenteral pathways. In fact, contaminated blood products are a major source of infection, which led to the initial descriptive term of post-transfusion hepatitis. Today, with improved safety measures in transfusion medicine, infections are caused by intravenous drug abuse and the associated needle sharing [10]. Medical staff is another risk group, as injuries with contaminated instruments such as canula can transmit HCV [11].

Figure 2.

Clinical presentation and natural course of HCV infection. In addition to the acute and chronic clinical picture, selected extrahepatic manifestations are shown. Phenomena with the strongest evidence for association with chronic HCV infection are printed in bold font. The other phenomena were observed with higher prevalence in HCV-infected individuals than in controls, but evidence was less strong [9]. Additional references [7,8]. Created with BioRender.com.

Worldwide, 1.5 million new HCV infections and 29,000 HCV-related deaths per year are assumed by the World Health Organization (WHO) [12]. The substantial health burden caused by HCV infection and viral hepatitis in general prompted the formulation of the hepatitis extinction goals by the WHO in 2016. In detail, the WHO pursues the ambitious goal of an 80% reduction in new HCV infections by the year 2030 [13].

1.3. Discovery of the HCV Replication Cycle

After the clinical description of NANBH and the discovery of its causative agent, HCV viral properties and the HCV replication cycle were subjects of intensive research. It was found that HCV is a positive single-stranded RNA virus that likely belongs to the family of Flaviviridae [4]. After internalization of the virus, the ssRNA(+) is released into the cytoplasm where host ribosomes on the endoplasmic reticulum translate the genetic material into the HCV polyprotein [14]. The viral proteins can be divided into structural and nonstructural (NS) proteins. Nonstructural proteins are needed for viral amplification and were seen as potential drug targets [14].

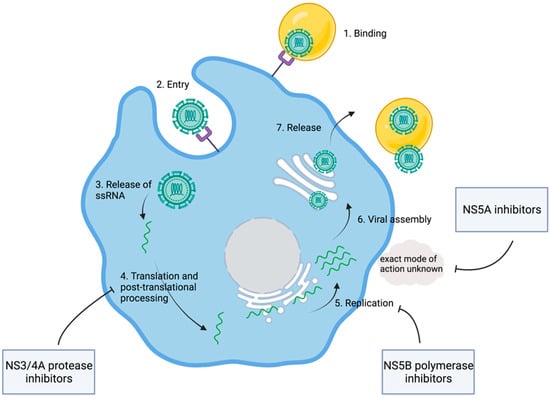

Even though HCV had been discovered, a cell culture was not available for the coming years. Consequently, cDNA clones generated from viral RNA extracted from the sera of infected individuals served as models for detailed analysis of the genome structure. It was suggested that an HCV polyprotein containing approximately 3000 amino acids is translated from a single open reading frame [15]. Comparisons to the genetic features of other viruses soon made it clear that HCV is related to pestiviruses, as well as flaviviruses, both genera of the family of Flaviviridae. HCV was deemed an unusual virus. However, the relative proximity to flaviviruses suggested that the HCV genome might be organized in a similar way. Flaviviridae are characterized by hydrophobic polyproteins that are cleaved by viral and host proteases into structural and nonstructural proteins [16]. In analogy, an HCV polyprotein was assumed. Computer-based approaches suggested potential cleavage sites, further promoting the understanding of potential structural and nonstructural proteins in HCV [15,16]. In a next step, in vitro protein expression assays allowed for a deeper insight into the actual structure of viral proteins. Therefore, expression plasmids were generated from HCV cDNA clones. These plasmids encoded 980 amino-terminal amino acid residues of the open reading frame. This work by Hijikata led to the identification of the two proteins, p22 and p19, as well as two glycoproteins named gp35 and gp70. It was suggested that the cleavage between the proteins depended on signal peptidases in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, with the exception of gp70 and p19. Finally, gp35 and gp60 were characterized as major viral envelope proteins [17]. Similarly, additional cleavage products of HCV polyprotein, including the nonstructural proteins NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B, were discovered (Table 1) [18]. The detailed description of viral proteins was complemented through research into the according molecular function. NS3 was identified as a viral protease catalyzing the cleavage between NS3 and NS4. This became evident in experiments where the replacement of a serine residue within the NS3 genome area blocked the cleavage between NS3/4 and NS4/5 [19]. Soon, it was found that, in addition to NS3, NS4A is also involved in the cleavage of the link between NS3/4A and NS5A/5B [20,21]. With viral proteases, a first potential therapeutic target was discovered (Figure 3). However, the exact mechanisms behind viral RNA synthesis were still hidden. In 1990, it was postulated that NS5B might be the responsible RNA polymerase [22]. In fact, six years later, Behrens et al. confirmed that NS5B was acting as an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [23].

Table 1.

Nonstructural proteins of the hepatitis C virus with according molecular functions and targeting by currently recommended direct-acting antiviral drugs.

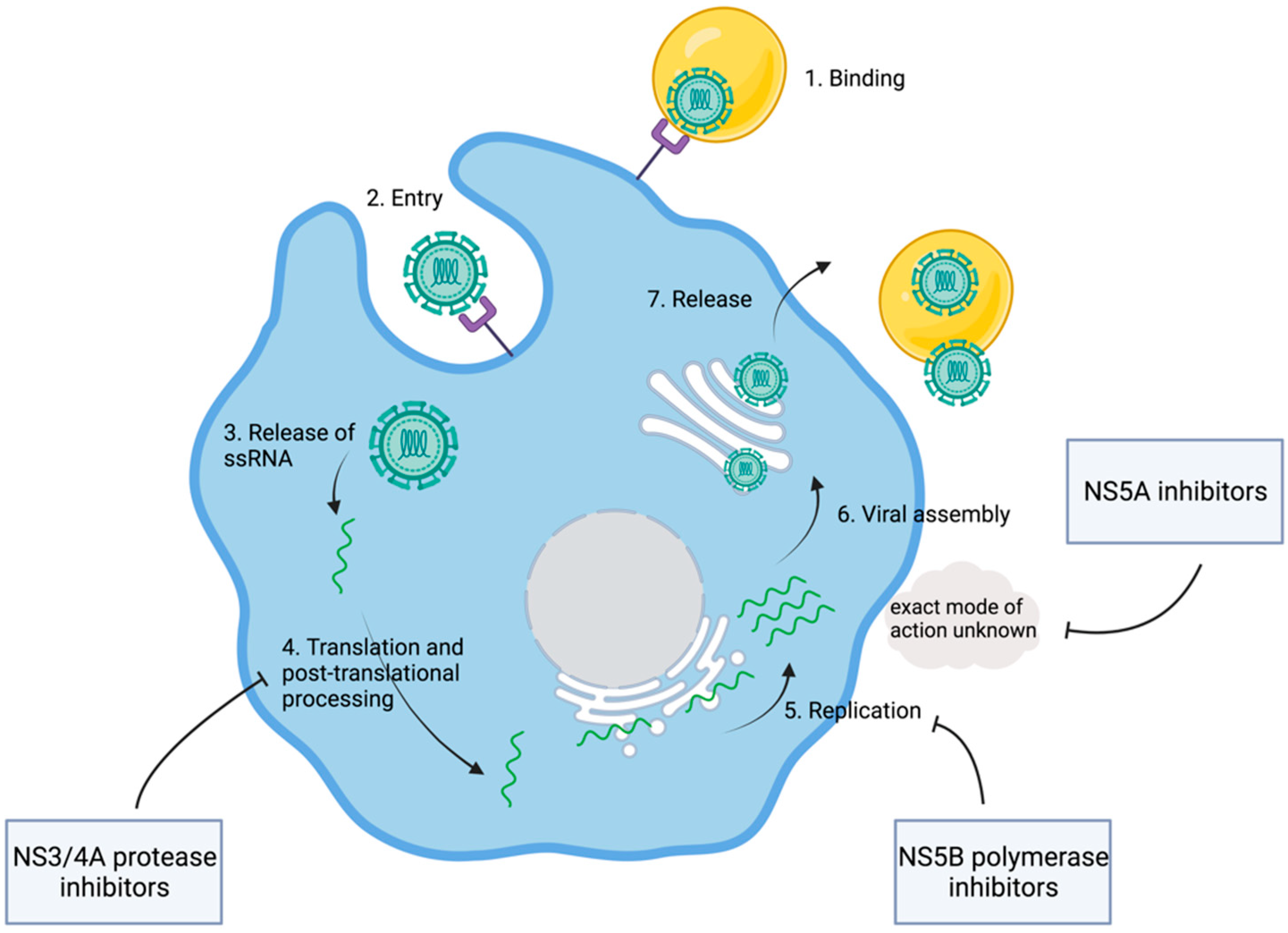

Figure 3.

Viral replication and points of attack of direct-acting antiviral agents. Shown are key steps of viral replication and the modes of action of different DAAs. After binding and cellular entry of the viral particle, the ssRNA is released and translated into the HCV polyprotein. DAAs interfere with the viral replication at different stages. NS3/4A protease inhibitors block the processing of the HCV polyprotein. NS5B inhibitors interfere with the viral RNA polymerase. For NS5A inhibitors, an interaction with viral and host proteins is assumed, while the exact mode of action is unknown. Adapted from [44]. Created with BioRender.com.

In parallel to intensive research on HCV polyprotein processing and viral replication, the key mechanisms of viral entry into hepatocytes were unraveled. First, CD81 was described as a ligand of the envelope protein E2, formerly known as gp70 [24]. HCV endocytosis was also found to be dependent on the LDL receptor [25]. Further steps of viral entry were attributed to the human scavenger receptor class B type 1 [26], as well as claudin-1 [27] and occludin [28].

The establishment of in vitro replication models was the next essential achievement, enabling the evaluation of antiviral agents and their potencies. Using RNA isolated from an HCV-infected individual, replicons were generated. These replicons were transfected into a human hepatoma cell line where autonomous replication was observed [29]. Another group was able to create replicons from different HCV genotypes that replicated in hepatoma cell lines. They also showed the suppression of viral replication by exposing cell cultures to interferon alpha, emphasizing the value of such replication models [30]. Finally, cell culture systems were successfully used to generate viral replicates that were infectious for chimpanzees [31].

3. Conclusions

The development of DAAs as cures for HCV infection was a milestone in biomedical research. The fruitful interplay of applied clinical science and basic research was remarkable. The initial observation of unclear cases of post-transfusion hepatitis at the bedside of patients stimulated scientific curiosity and led to the description of HCV as the causative agent. The in-depth characterization of viral properties resulted in the discovery of potential therapeutic targets. While the quest for efficient, direct-acting antiviral agents had begun, clinicians were still using interferon with limited antiviral efficacy to protect patients from HCV-related chronic liver disease. Finally, the first DAA-containing treatment regimen was approved in 2011. However, IFN was still part of that treatment regimen, and clinicians, as well as scientists, were aiming for IFN-free HCV treatments. In 2013, the approval of SOF finally marked the beginning of an IFN-free era with excellent antiviral efficacy and SVR rates above 90%, even in those with unsuccessful IFN pretreatments. As of today, the remaining challenges include the detection of HCV-infected individuals and the referral to treatment, especially in low-income countries and communities with difficult access to health care. Ultimately, the development of a working HCV vaccine can help achieve the WHO HCV extinction goals in the coming years.

Author Contributions

C.D. and B.M. studied the literature and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

C.D. has no conflict of interest to declare. B.M. has received speaker and consulting fees from Abbott Molecular, Astellas, Intercept, Falk, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Fujirebio, Janssen-Cilag, Merck/MSD, and Roche. He also received research support from Abbott Molecular and Roche.

References

- Ghany, M.G.; Lok, A.S.F.; Dienstag, J.L.; Feinstone, S.M.; Hoofnagle, J.H.; Jake Liang, T.; Seeff, L.B.; Cohen, D.E.; Bezerra, J.A.; Chung, R.T. The 2020 Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology for the Discovery of Hepatitis C Virus: A Triumph of Curiosity and Persistence. Hepatology 2021, 74, 2813–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manns, M.; Maasoumy, B. Breakthroughs in hepatitis C research: From discovery to cure. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 11, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinstone, S.M.; Kapikian, A.Z.; Purcell, R.H.; Alter, H.J.; Holland, P.V. Transfusion-Associated Hepatitis Not Due to Viral Hepatitis Type A or B. N. Engl. J. Med. 1975, 292, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Q.L.; Kuo, G.; Weiner, A.J.; Overby, L.R.; Bradley, D.W.; Houghton, M. Isol. a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 1989, 244, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, G.; Choo, Q.L.; Alter, H.J.; Gitnick, G.L.; Redeker, A.G.; Purcell, R.H.; Miyamura, T.; Dienstag, J.L.; Alter, M.J.; Stevens, C.E.; et al. An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science 1989, 244, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoletti, A.; Ferrari, C. Kinetics of the immune response during HBV and HCV infection. Hepatology 2003, 38, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasoumy, B.; Wedemeyer, H. Natural history of acute and chronic hepatitis C. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, L.; El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 477–491.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacoub, P.; Gragnani, L.; Comarmond, C.; Zignego, A.L. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, S165–S173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larney, S.; Peacock, A.; Leung, J.; Colledge, S.; Hickman, M.; Vickerman, P.; Grebely, J.; Dumchev, K.V.; Griffiths, P.; Hines, L.; et al. Global, regional, and country-level coverage of interventions to prevent and manage HIV and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e1208–e1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebely, J.; Prins, M.; Hellard, M.; Cox, A.L.; Osburn, W.O.; Lauer, G.; Page, K.; Lloyd, A.R.; Dore, G.J. Hepatitis C virus clearance, reinfection, and persistence, with insights from studies of injecting drug users: Towards a vaccine. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Progress Report on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027077 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- WHO. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021–Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis. 2016. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/246177 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Lohmann, V. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 369, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takamizawa, A.; Mori, C.; Fuke, I.; Manabe, S.; Murakami, S.; Fujita, J.; Onishi, E.; Andoh, T.; Yoshida, I.; Okayama, H. Structure and organization of the hepatitis C virus genome isolated from human carriers. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, Q.L.; Richman, K.H.; Han, J.H.; Berger, K.; Lee, C.; Dong, C.; Gallegos, C.; Coit, D.; Medina-Selby, R.; Barr, P.J.; et al. Genetic organization and diversity of the hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 2451–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijikata, M.; Kato, N.; Ootsuyama, Y.; Nakagawa, M.; Shimotohno, K. Gene mapping of the putative structural region of the hepatitis C virus genome by in vitro processing analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 5547–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grakoui, A.; Wychowski, C.; Lin, C.; Feinstone, S.M.; Rice, C.M. Expression and identification of hepatitis C virus polyprotein cleavage products. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartenschlager, R.; Ahlborn-Laake, L.; Mous, J.; Jacobsen, H. Nonstructural protein 3 of the hepatitis C virus encodes a serine-type proteinase required for cleavage at the NS3/4 and NS4/5 junctions. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 3835–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failla, C.; Tomei, L.; De Francesco, R. Both NS3 and NS4A are required for proteolytic processing of hepatitis C virus nonstructural proteins. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 3753–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartenschlager, R.; Ahlborn-Laake, L.; Mous, J.; Jacobsen, H. Kinetic and structural analyses of hepatitis C virus polyprotein processing. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 5045–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.H.; Purcell, R.H. Hepatitis C virus shares amino acid sequence similarity with pestiviruses and flaviviruses as well as members of two plant virus supergroups. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 2057–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, S.E.; Tomei, L.; De Francesco, R. Identification and properties of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pileri, P.; Uematsu, Y.; Campagnoli, S.; Galli, G.; Falugi, F.; Petracca, R.; Weiner, A.J.; Houghton, M.; Rosa, D.; Grandi, G.; et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 1998, 282, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnello, V.; Abel, G.; Elfahal, M.; Knight, G.B.; Zhang, Q.X. Hepatitis C virus and other flaviviridae viruses enter cells via low density lipoprotein receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 12766–12771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, E.; Ansuini, H.; Cerino, R.; Roccasecca, R.M.; Acali, S.; Filocamo, G.; Traboni, C.; Nicosia, A.; Cortese, R.; Vitelli, A. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 5017–5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.J.; Von Hahn, T.; Tscherne, D.M.; Syder, A.J.; Panis, M.; Wölk, B.; Hatziioannou, T.; McKeating, J.A.; Bieniasz, P.D.; Rice, C.M. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature 2007, 446, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploss, A.; Evans, M.J.; Gaysinskaya, V.A.; Panis, M.; You, H.; De Jong, Y.P.; Rice, C.M. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature 2009, 457, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, V.; Körner, F.; Koch, J.; Herian, U.; Theilmann, L.; Bartenschlager, R. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 1999, 285, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blight, K.J.; Kolykhalov, A.A.; Rice, C.M. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science 2000, 290, 1972–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakita, T.; Pietschmann, T.; Kato, T.; Date, T.; Miyamoto, M.; Zhao, Z.; Murthy, K.; Habermann, A.; Krausslich, H.G.; Mizokami, M.; et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarre, D.; Anderson, P.C.; Bailey, M.; Beaulieu, P.; Bolger, G.; Bonneau, P.; Bös, M.; Cameron, D.R.; Cartier, M.; Cordingley, M.G.; et al. An NS3 protease inhibitor with antiviral effects in humans infected with hepatitis C virus. Nature 2003, 426, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichsen, H.; Benhamou, Y.; Wedemeyer, H.; Reiser, M.; Sentjens, R.E.; Calleja, J.L.; Forns, X.; Erhardt, A.; Cronlein, J.; Chaves, R.L.; et al. Short-term antiviral efficacy of BILN 2061, a hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitor, in hepatitis C genotype 1 patients. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiser, M.; Hinrichsen, H.; Benhamou, Y.; Reesink, H.W.; Wedemeyer, H.; Avendano, C.; Riba, N.; Yong, C.L.; Nehmiz, G.; Steinmann, G.G. Antiviral efficacy of NS3-serine protease inhibitor BILN-2061 in patients with chronic genotype 2 and 3 hepatitis C. Hepatology 2005, 41, 832–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanwolleghem, T.; Meuleman, P.; Libbrecht, L.; Roskams, T.; De Vos, R.; Leroux-Roels, G. Ultra-rapid cardiotoxicity of the hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor BILN 2061 in the urokinase-type plasminogen activator mouse. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, K.E.; Flamm, S.L.; Afdhal, N.H.; Nelson, D.R.; Sulkowski, M.S.; Everson, G.T.; Fried, M.W.; Adler, M.; Reesink, H.W.; Martin, M.; et al. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHutchison, J.G.; Manns, M.P.; Muir, A.J.; Terrault, N.A.; Jacobson, I.M.; Afdhal, N.H.; Heathcote, E.J.; Zeuzem, S.; Reesink, H.W.; Garg, J.; et al. Telaprevir for previously treated chronic HCV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeuzem, S.; Andreone, P.; Pol, S.; Lawitz, E.; Diago, M.; Roberts, S.; Focaccia, R.; Younossi, Z.; Foster, G.R.; Horban, A.; et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2417–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poordad, F.; McCone, J., Jr.; Bacon, B.R.; Bruno, S.; Manns, M.P.; Sulkowski, M.S.; Jacobson, I.M.; Reddy, K.R.; Goodman, Z.D.; Boparai, N.; et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, B.R.; Gordon, S.C.; Lawitz, E.; Marcellin, P.; Vierling, J.M.; Zeuzem, S.; Poordad, F.; Goodman, Z.D.; Sings, H.L.; Boparai, N.; et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesudian, A.B.; Jacobson, I.M. Optimal treatment with telaprevir for chronic HCV infection. Liver Int. 2013, 33, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierling, J.M.; Zeuzem, S.; Poordad, F.; Bronowicki, J.P.; Manns, M.P.; Bacon, B.R.; Esteban, R.; Flamm, S.L.; Kwo, P.Y.; Pedicone, L.D.; et al. Safety and efficacy of boceprevir/peginterferon/ribavirin for HCV G1 compensated cirrhotics: Meta-analysis of 5 trials. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasoumy, B.; Port, K.; Markova, A.A.; Serrano, B.C.; Rogalska-Taranta, M.; Sollik, L.; Mix, C.; Kirschner, J.; Manns, M.P.; Wedemeyer, H.; et al. Eligibility and safety of triple therapy for hepatitis C: Lessons learned from the first experience in a real world setting. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55285. [Google Scholar]

- Manns, M.P.; Cornberg, M. Sofosbuvir: The final nail in the coffin for hepatitis C? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 378–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.O.; Treitel, M.; Graham, D.J.; Curry, S.; Frontera, M.J.; McMonagle, P.; Gupta, S.; Hughes, E.; Chase, R.; Lahser, F.; et al. Antiviral activity of boceprevir monotherapy in treatment-naive subjects with chronic hepatitis C genotype 2/3. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, J.P.; Humphreys, I.; Flaxman, A.; Brown, A.; Cooke, G.S.; Pybus, O.G.; Barnes, E. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 2015, 61, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Kramer, J.R.; Ilyas, J.; Duan, Z.; El-Serag, H.B. HCV genotype 3 is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer in a national sample of U.S. Veterans with HCV. Hepatology 2014, 60, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.G.; Sablon, E.; Chamberland, J.; Fournier, E.; Dandavino, R.; Tremblay, C.L. Hepatitis C virus genotype 7, a new genotype originating from central Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemm, J.A.; O’Boyle, D., 2nd; Liu, M.; Nower, P.T.; Colonno, R.; Deshpande, M.S.; Snyder, L.B.; Martin, S.W.; St Laurent, D.R.; Serrano-Wu, M.H.; et al. Identification of hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitors. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Nettles, R.E.; Belema, M.; Snyder, L.B.; Nguyen, V.N.; Fridell, R.A.; Serrano-Wu, M.H.; Langley, D.R.; Sun, J.H.; O’Boyle, D.R., 2nd; et al. Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature 2010, 465, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manns, M.; Pol, S.; Jacobson, I.M.; Marcellin, P.; Gordon, S.C.; Peng, C.Y.; Chang, T.T.; Everson, G.T.; Heo, J.; Gerken, G.; et al. All-oral daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: A multinational, phase 3, multicohort study. Lancet 2014, 384, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludmerer, S.W.; Graham, D.J.; Boots, E.; Murray, E.M.; Simcoe, A.; Markel, E.J.; Grobler, J.A.; Flores, O.A.; Olsen, D.B.; Hazuda, D.J.; et al. Replication fitness and NS5B drug sensitivity of diverse hepatitis C virus isolates characterized by using a transient replication assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abraham, G.M.; Spooner, L.M. Sofosbuvir in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: New dog, new tricks. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gane, E.J.; Stedman, C.A.; Hyland, R.H.; Ding, X.; Svarovskaia, E.; Symonds, W.T.; Hindes, R.G.; Berrey, M.M. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honer Zu Siederdissen, C.; Maasoumy, B.; Marra, F.; Deterding, K.; Port, K.; Manns, M.P.; Cornberg, M.; Back, D.; Wedemeyer, H. Drug-Drug Interactions with Novel All Oral Interferon-Free Antiviral Agents in a Large Real-World Cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puoti, M.; Panzeri, C.; Rossotti, R.; Baiguera, C. Efficacy of sofosbuvir-based therapies in HIV/HCV infected patients and persons who inject drugs. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, S206–S211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sulkowski, M.S.; Naggie, S.; Lalezari, J.; Fessel, W.J.; Mounzer, K.; Shuhart, M.; Luetkemeyer, A.F.; Asmuth, D.; Gaggar, A.; Ni, L.; et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients with HIV coinfection. JAMA 2014, 312, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C: Final Update of the Series. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1170–1218. [CrossRef]

- Kirby, B.J.; Symonds, W.T.; Kearney, B.P.; Mathias, A.A. Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacodynamic, and Drug-Interaction Profile of the Hepatitis C Virus NS5B Polymerase Inhibitor Sofosbuvir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2015, 54, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogalian, E.; German, P.; Kearney, B.P.; Yang, C.Y.; Brainard, D.; McNally, J.; Moorehead, L.; Mathias, A. Use of Multiple Probes to Assess. Transporter- and Cytochrome P450-Mediated Drug-Drug Interaction Potential of the Pangenotypic HCV NS5A Inhibitor Velpatasvir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2016, 55, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, J.J.; Jacobson, I.M.; Hezode, C.; Asselah, T.; Ruane, P.J.; Gruener, N.; Abergel, A.; Mangia, A.; Lai, C.L.; Chan, H.L.; et al. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV Genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 333, 2599–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.R.; Afdhal, N.; Roberts, S.K.; Brau, N.; Gane, E.J.; Pianko, S.; Lawitz, E.; Thompson, A.; Shiffman, M.L.; Cooper, C.; et al. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV Genotype 2 and 3 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2608–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, M.P.; O’Leary, J.G.; Bzowej, N.; Muir, A.J.; Korenblat, K.M.; Fenkel, J.M.; Reddy, K.R.; Lawitz, E.; Flamm, S.L.; Schiano, T.; et al. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV in Patients with Decompensated Cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2618–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyles, D.; Brau, N.; Kottilil, S.; Daar, E.S.; Ruane, P.; Workowski, K.; Luetkemeyer, A.; Adeyemi, O.; Kim, A.Y.; Doehle, B.; et al. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for the Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus in Patients Coinfected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1: An Open-Label, Phase 3 Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puoti, M.; Foster, G.R.; Wang, S.; Mutimer, D.; Gane, E.; Moreno, C.; Chang, T.T.; Lee, S.S.; Marinho, R.; Dufour, J.F.; et al. High SVR12 with 8-week and 12-week glecaprevir/pibrentasvir therapy: An integrated analysis of HCV genotype 1–6 patients without cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ambrosio, R.; Pasulo, L.; Puoti, M.; Vinci, M.; Schiavini, M.; Lazzaroni, S.; Soria, A.; Gatti, F.; Menzaghi, B.; Aghemo, A.; et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in 723 patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, T.; Naumann, U.; Stoehr, A.; Sick, C.; John, C.; Teuber, G.; Schiffelholz, W.; Mauss, S.; Lohmann, K.; König, B.; et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection: Data from the German Hepatitis C-Registry. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 49, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeuzem, S.; Serfaty, L.; Vierling, J.; Cheng, W.; George, J.; Sperl, J.; Strasser, S.; Kumada, H.; Hwang, P.; Robertson, M.; et al. The safety and efficacy of elbasvir and grazoprevir in participants with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, I.M.; Lawitz, E.; Kwo, P.Y.; Hezode, C.; Peng, C.Y.; Howe, A.Y.M.; Hwang, P.; Wahl, J.; Robertson, M.; Barr, E.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Elbasvir/Grazoprevir in Patients with Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Compensated Cirrhosis: An Integrated Analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1372–1382.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourliere, M.; Gordon, S.C.; Flamm, S.L.; Cooper, C.L.; Ramji, A.; Tong, M.; Ravendhran, N.; Vierling, J.M.; Tran, T.T.; Pianko, S.; et al. Sofosbuvir, Velpatasvir, and Voxilaprevir for Previously Treated HCV Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2134–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belperio, P.S.; Shahoumian, T.A.; Loomis, T.P.; Backus, L.I. Real-world effectiveness of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in 573 direct-acting antiviral experienced hepatitis C patients. J. Viral Hepat. 2019, 26, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degasperi, E.; Spinetti, A.; Lombardi, A.; Landonio, S.; Rossi, M.C.; Pasulo, L.; Pozzoni, P.; Giorgini, A.; Fabris, P.; Romano, A.; et al. Real-life effectiveness and safety of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in hepatitis C patients with previous DAA failure. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.R.; Irving, W.L.; Cheung, M.C.; Walker, A.J.; Hudson, B.E.; Verma, S.; McLauchlan, J.; Mutimer, D.J.; Brown, A.; Gelson, W.T.; et al. Impact of direct acting antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C and decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belli, L.S.; Berenguer, M.; Cortesi, P.A.; Strazzabosco, M.; Rockenschaub, S.R.; Martini, S.; Morelli, C.; Donato, F.; Volpes, R.; Pageaux, G.P.; et al. Delisting of liver transplant candidates with chronic hepatitis C after viral eradication: A European study. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, G.; Trota, N.; Londoño, M.C.; Mauro, E.; Baliellas, C.; Castells, L.; Castellote, J.; Tort, J.; Forns, X.; Navasa, M. The efficacy of direct anti-HCV drugs improves early post-liver transplant survival and induces significant changes in waiting list composition. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waked, I.; Esmat, G.; Elsharkawy, A.; El-Serafy, M.; Abdel-Razek, W.; Ghalab, R.; Elshishiney, G.; Salah, A.; Abdel Megid, S.; Kabil, K.; et al. Screening and Treatment Program to Eliminate Hepatitis C in Egypt. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-L.; Chang, M.-H.; Ni, Y.-H.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Lee, P.-l.; Lee, C.-Y.; Chen, D.-S. Seroepidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Children: Ten Years of Mass Vaccination in Taiwan. JAMA 1996, 276, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.H.; Chen, C.J.; Lai, M.S.; Hsu, H.M.; Wu, T.C.; Kong, M.S.; Liang, D.C.; Shau, W.Y.; Chen, D.S. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 1855–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Maruyama, T.; Lewis, J.; Giang, E.; Tarr, A.W.; Stamataki, Z.; Gastaminza, P.; Chisari, F.V.; Jones, I.M.; Fox, R.I.; et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies protect against hepatitis C virus quasispecies challenge. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, K.; Melia, M.T.; Veenhuis, R.T.; Winter, M.; Rousseau, K.E.; Massaccesi, G.; Osburn, W.O.; Forman, M.; Thomas, E.; Thornton, K.; et al. Randomized Trial of a Vaccine Regimen to Prevent Chronic HCV Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda-Crespo, D.; Resino, S.; Martinez, I. Hepatitis C virus vaccine design: Focus on the humoral immune response. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).