Abstract

The visually impaired suffer greatly while moving from one place to another. They face challenges in going outdoors and in protecting themselves from moving and stationary objects, and they also lack confidence due to restricted mobility. Due to the recent rapid rise in the number of visually impaired persons, the development of assistive devices has emerged as a significant research field. This review study introduces several techniques to help the visually impaired with their mobility and presents the state-of-the-art of recent assistive technologies that facilitate their everyday life. It also analyses comprehensive multiple mobility assistive technologies for indoor and outdoor environments and describes the different location and feedback methods for the visually impaired using assistive tools based on recent technologies. The navigation tools used for the visually impaired are discussed in detail in subsequent sections. Finally, a detailed analysis of various methods is also carried out, with future recommendations.

1. Introduction

Vision-based methods are a specialized method of allowing people to observe and infer knowledge elicited from the environment. The environment may not only be restricted indoors but may extend outdoors as well. A visually impaired person usually faces several challenges for safe and independent movement both indoors and outdoors. These challenges may be more considerable while navigating through an outdoor environment if a person is unfamiliar with the new background and context due to reduced and contracted vision. To overcome mobility restrictions such as walking, shopping, playing, or moving in an outdoor environment, many assistive tools and technologies have been proposed as wearable devices, allowing users to interact with the environment without triggering any risk. These assistive tools improve the quality of life of the visually impaired and make them sufficiently capable to navigate indoors and outdoors [1].

Statistics published by the World Health Organization (WHO) have revealed that one-sixth of the world population is visually impaired, and that figure is sharply increasing [2]. Becoming visually impaired or blind does not imply that a person cannot travel to and from locations at any time they desire. These individuals with visual deficits and diseases require support to complete everyday tasks, which include walking and investigating new areas, just as an average person without disabilities does. Insecure and ineffective navigating ranks among the most significant barriers to freedom for visually impaired and blind persons and assisting these visually impaired users is an important research area. Traditionally, guide dogs and white canes have served as travel assistants. However, they can only partially provide independent and safe mobility. Recent advances in technologies, however, have broadened the spectrum of solutions. From solutions based on radars in the mid-20th century to the current Artificial Intelligence (A.I.), emerging assistive techniques have played a vital role in designing wearable devices for the visually impaired. State-of-the-art techniques in these primary wearable assistive devices incorporate Global Systems for GSM mobile communication along with G.P.S. tools and techniques that automatically identify the location of the wearer and transfer that location to their guardian device [3].

Similarly, Electronic Travel Aids are based on sensors such as infrared, ultrasonic, Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), and G.P.S. to perceive the environment, process the information, and detect objects [4]. Further, many persons are unable to play video games because of visual impairments and have restricted accessibility while interacting with video games and taking part in various educational, social, and physical activities [5]. Game-based approaches to training in navigation systems in unfamiliar environments can help the players build a reliable spatial cognitive map of the surroundings, while audio cues processed by sonification can help players recognize objects in the gaming environment. For example, verbal notifications can help players grasp their location and tell them which task must be accomplished. On the other hand, non-verbal cues can indicate the meta-level of knowledge regarding the target object’s location, direction, and distance to build spatial cognitive maps [6].

While considering the popularity of smart devices among the visually impaired, an optimized solution using a smartphone does not yet exist [7,8,9]. This review study addresses various solutions that allow visually impaired users to walk more confidently across a street. Moreover, smartphone-based solutions are extended to both indoor and outdoor environments. However, no efficient solution for a real-time indoor navigation system exists yet either. A comparison of current navigation systems is shown in Table 1, which also allows a subjective evaluation of the technologies based on user needs.

Table 1.

Comparison of Existing Technologies Based on Different Technologies.

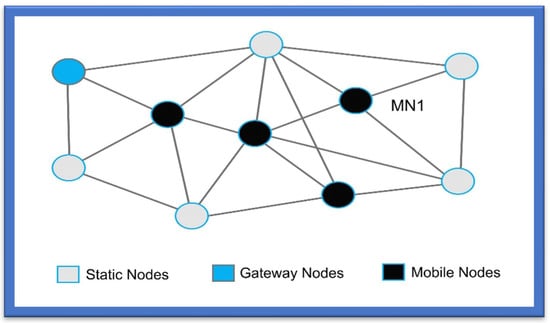

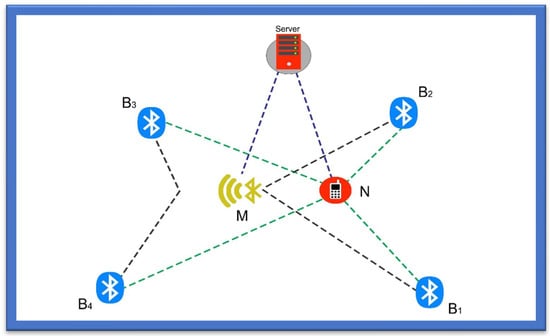

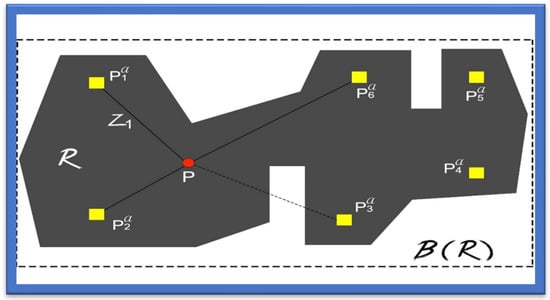

In contrast with the indoor environment, the GPS-based navigation systems consume more power in the outdoor environment than proposed technologies such as Zigbee and Bluetooth [10]. Bluetooth is not comparable with ZigBee due to its power consumption. If an application is operated for an extended period on a battery, e.g., using G.P.S., Bluetooth will not be adequate. Bluetooth design recommends one watt of power consumption. Still, when combined with wireless G.P.S. applications, the power consumption of both Bluetooth and ZigBee is between 10 and 100 milliwatts (mW), which is 100 times less than previous Bluetooth designs [11]. With Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) technology, tracking and navigation have become more accessible and convenient. In fact, WSN has progressed as a dominant field of research. Thus, multiple tools and technologies have been proposed in the literature and incorporated into natural environments to assist visually impaired users. Similarly, several surveys and reviews have summarized state-of-the-art assistive technologies for visually impaired users. These technologies provide a broad spectrum of techniques that could further progress [12,13,14].

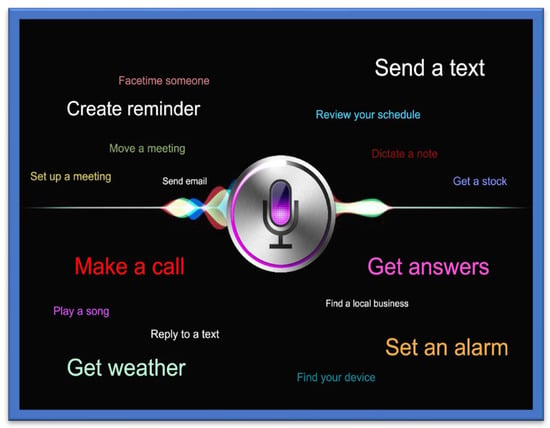

Various experiments conducted by researchers used an audio screen linked with N.V.D.A.D.A. screen reading software. The audio screen allowed a blind user to move the fingers, pen, or mouse on the picture shown on the screen and hear information about the part they touched. The user could explore the maps of countries, colors of the rainbow, and cartoon characters. The audio screen allowed the user to hear the description of the text (font, size, and color) The audio screen was further divided into two output modes. The first was “pitch stereo grey”, which was helpful in the description of images, maps, and diagrams. The second one was “HSV Colors,” which described the variations in colors of photographs [15].

Multiple articles were reviewed in detail while formulating this survey article. The obstacle recognition method, feedback methods, and navigation technologies for the visually impaired are briefly explained in Section 2. Different navigation and feedback tools are discussed in Section 3, while Section 4 contains discussions about the papers. Section 5 concludes the research survey, provides future directions for researchers, and presents the pros and cons from the perspective of visually impaired users.

4. Discussion

Several research studies were conducted on various navigational systems that have been created over time to assist the visually impaired and blind, but of which only a few remain in use. Although most of the methods make sense in theory, in practice they may be excessively complicated or laborious for the user. This evaluation analysis has been divided into sections according to specific characteristics, including recording methods, smart response to objects, physical hardware, transmission range, detection limit, size, and cost efficiency. These preselected standards described in this study are chosen because they assess system performance. Navigating through various situations is difficult for those with vision impairments, who must be aware of the objects and landscape in the immediate environment, such as people, tables, and dividers. Likewise, the inability to deal with such circumstances itself adversely affects the sense of freedom of the visually impaired, who have little opportunity to find their way in a new environment.

A guide is always needed for the outdoor environment. However, it is not a good solution due to dependency on others. One can request directions for a limited time at some place but asking people for direction every time causes difficulties to move freely. Numerous tools have been developed and effectively deployed to help impaired individuals avoid obstacles outdoors, such as intelligent canes and seeing-eye dogs, Braille signs, and G.P.S. systems. One approach to navigation systems is the adoption of neural networks. To help the visually impaired to move around, researchers have presented two deep Convolutional Neural Network models. However, this approach is not very efficient in terms of time complexity [90].

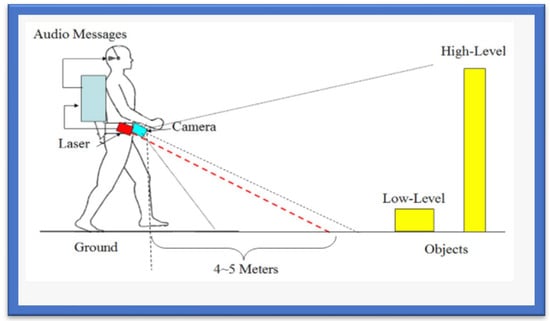

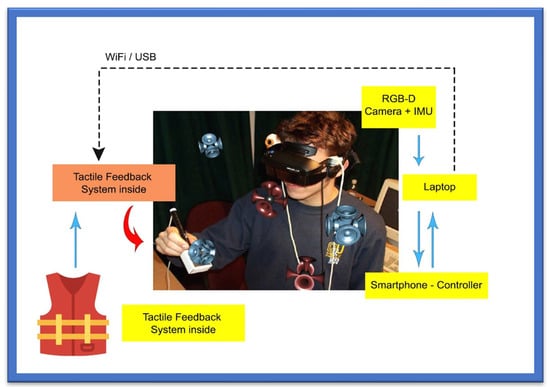

Some of the approaches for navigation systems have adopted sensory substitution methods, such as one based on LIDARs [87] or a vibrotactile stimulation [88] applied to the palms of the hand to direct users through a temporal sequence of stimuli. A vibrating belt with time-of-flight distance sensors and cameras was used to acquire better navigation [109]. An outdoor navigation system based on vision positioning to direct blind people was proposed in [115]. Image processing is used for identifying the path and obstacles in the path. An assistive-guide robot called an eye dog has been designed as an alternative to guide dogs for blind people [116].

In [90], the author designed an intelligent blind stick outfitted with an ultrasonic sensor and piezo buzzer that sounds an alarm when the user approaches an obstacle. A fusion of depth and vision sensors was proposed in [26], by which obstacles are detected using corner detection. At the same time, the corresponding distance is calculated using input received from the depth sensor. Further, the main problems for the visually impaired and blind are in finding their way in unfamiliar environments. While they strive to orient themselves in places where they had previously been, places such as shopping malls, train stations, and airports change almost daily. Blind people must orient themselves in a vast place full of distractions such as background music, announcement, various kinds of scents and moving people, etc. They cannot rely totally on their senses in such a place, and they cannot easily find help at any time, for example, by finding a clothing store on the fifth floor.

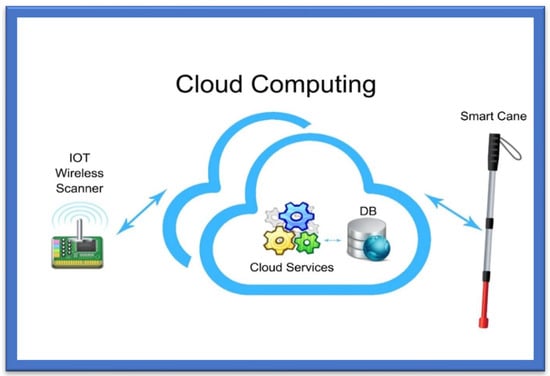

Although assistive technologies allow the visually impaired to navigate their surroundings freely and confidently, a significant concern that is usually neglected is the power consumption and charging time of such devices. Preferably, images of paths and pedestrians can be stored on mobiles to overcome these problems. Doing so will allow visually impaired users to identify the obstacles and routes automatically, thus consuming less power for capturing and processing. However, this solution takes up memory; shifting from mobile devices to the cloud, therefore, will ease this issue of memory consumption and sharing of updated data between devices [117]. Moreover, the fully charged device should last significantly more than 48 h to prevent difficulties with daily charging. Proper training should also be incorporated into the orientation and mobility of the visually impaired, as programs scheduled to train the blind and visually impaired to travel safely help in daily routine tasks and to fit into their community. Considering our previous work on serious games, we think that they may help in the training [118,119,120].

The training sessions helped the students to understand and learn different techniques for street crossings and public transportation with the help of a cane. Visually impaired students who are comfortable with having dog assistance are trained with the help of the application process. This training program is usually applied one-on-one in the student community, home, school, and workplace.

Most instructions and tasks are completed in group discussions and class settings. When organizing the plan for orientation and mobility assistive technologies for the visually impaired, the focus on training should not be neglected.

Some major categories of assistive technologies are:

(1) Public transportation crossing assistive technology, which allows the visually impaired to learn the door-to-door bus service or the public bus transport systems in their area. Training is required to understand assistive maps to reach the bus transport or understand routes according to the needs of the visually impaired user;

(2) Another assistive technology is the Sighted Guide, which allows visually impaired users to practice the skills required for traveling with the aid of a sighted person and gain the ability to train any sighted person to guide them safely through any environment;

(3) Similarly, Safe Travel assistive technology allows visually impaired users to travel safely in an unfamiliar environment. These assistive technologies help in detecting obstacles;

(4) Orientation-based assistive technology allows visually impaired users to become familiar with both indoor and outdoor environments with the help of an experienced instructor. Haptic and auditory feedbacks may help in guiding users [121,122,123].

(5) Cane Skills assistive technology allows visually impaired users to become familiar with canes and to identify objects without restricting their mobility. Orientation and mobility training for assistive technologies are therefore essential for visually impaired users because, without mobility, a user becomes homebound. With necessary training sessions, a visually impaired user learns the required skills and confidently navigates indoors and outdoors.

The evaluation gives a set of essential guidelines for detailing technological devices and the characteristics that must be incorporated into the methods to improve effectiveness. These criteria are described as follows:

- Basic: a method can be used relatively quickly without additional equipment assistance;

- Minimal cost: an affordable model must be built. Consequently, this design will be inaccessible to most individuals;

- Compactness: a compact size allows the device to be used by those with limited mobility;

- Reliable: the hardware and software requirements for the gadget must be compliant;

- Covering region: This gadget must meet the wireless needs of the individual both indoors as well as outside.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Several of the latest assistive technologies for the visually impaired in the fields of computer vision, integrated devices, and mobile platforms have been presented in this paper. Even though many techniques under examination have been in relatively initial phases, most are being incorporated into daily life using state-of technology (i.e., smart devices). The proposed device aims to create an audio input and vibrations in the vicinity of obstructions in outdoor and indoor areas.

Our research review has comprehensively studied visually impaired users’ indoor and outdoor assistive navigation methods and has provided an in-depth analysis of multiple tools and techniques used as assistive measures for visually impaired users. It has also covered a detailed investigation of former research and reviews presented in the same domain and rendered highly accessible data for other researchers to evaluate the scope of former studies conducted in the same field. We have investigated multiple algorithms, datasets, and limitations of the former studies. In addition to the state-of-the-art tools and techniques, we have also provided application-based and subjective evaluations of those techniques that allow visually impaired users to navigate confidently indoors and outdoors.

In summary, detailed work is required to provide a reliable and comprehensive technology based on a Machine Learning algorithm. We have also emphasized knowledge transfer from one domain to another, such as driver assistance, automated cars, cane skills, and robot navigation. We also have insisted on training in assistive technology for visually impaired users. We have categorized assistive technologies and individually identified how training in each category could make a difference. However, previous work has ignored other factors involved in assistive technology, such as power consumption, feedback, and wearability. A technology that requires batteries and fast processing also require power consumption solutions relative to the device type. The researcher must determine the feasibility of running real-time obstacle detection through wearable camera devices. Various methods in the literature are “lab-based”, focusing on achieving accurate results rather than dealing with issues of power consumption and device deployment. Therefore, technologies that consume less power and are easy to wear in the future must be incorporated. These techniques should also be efficient enough to allow user to navigate effectively and confidently.

Author Contributions

Writing—initial draft preparation and final version: M.D.M.; writing—review and editing: B.-A.J.M. and H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Grant number from NSERC is RGPIN-2019-07169.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zafar, S.; Asif, M.; Bin Ahmad, M.; Ghazal, T.M.; Faiz, T.; Ahmad, M.; Khan, M.A. Assistive Devices Analysis for Visually Impaired Persons: A Review on Taxonomy. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 13354–13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, N.A.; Legge, G.E. Blind Navigation and the Role of Technology. In The Engineering Handbook of Smart Technology for Aging, Disability, and Independence; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Surendran, D.; Janet, J.; Prabha, D.; Anisha, E. A Study on Devices for Assisting Alzheimer Patients. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC)I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Palladam, India, 30–31 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, A.D.P.; Suzuki, A.H.G.; Medola, F.O.; Vaezipour, A. A Systematic Review of Wearable Devices for Orientation and Mobility of Adults with Visual Impairment and Blindness. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 162306–162324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhavat, Y.A.; Azadehfar, M.R.; Zarei, H.; Roohi, S. Sonification and interaction design in computer games for visually impaired individuals. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 7847–7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theil, A.; Buchweitz, L.; Schulz, A.S.; Korn, O. Understanding the perceptions and experiences of the deafblind community about digital games. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Wu, C.-K.; Liu, P.-Y. Assistive technology in smart cities: A case of street crossing for the visually-impaired. Technol. Soc. 2021, 68, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kafaji, R.D.; Gharghan, S.K.; Mahdi, S.Q. Localization Techniques for Blind People in Outdoor/Indoor Environments: Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 745, 12103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, W.C.S.S.; Machado, G.S.; Sales, A.M.A.; De Lucena, M.M.; Jazdi, N.; De Lucena, V.F. A Review of Technologies and Techniques for Indoor Navigation Systems for the Visually Impaired. Sensors 2020, 20, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayalakshmi, A.; Jose, D.V.; Unnisa, S. Internet of Things: Immersive Healthcare Technologies. In Immersive Technology in Smart Cities; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Singh, S. A Survey on the ZigBee Protocol, It’s Security in Internet of Things (IoT) and Comparison of ZigBee with Bluetooth and Wi-Fi. In Algorithms for Intelligent Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Walle, H.; De Runz, C.; Serres, B.; Venturini, G. A Survey on Recent Advances in AI and Vision-Based Methods for Helping and Guiding Visually Impaired People. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapu, R.; Mocanu, B.; Zaharia, T. Wearable assistive devices for visually impaired: A state of the art survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2018, 137, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmannai, W.; Elleithy, K. Sensor-Based Assistive Devices for Visually-Impaired People: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions. Sensors 2017, 17, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halimah, B.Z.; Azlina, A.; Behrang, P.; Choo, W.O. Voice Recognition System for the Visually Impaired: Virtual Cognitive Approach. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Symposium on Information Technology, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 23–26 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Plikynas, D.; Žvironas, A.; Budrionis, A.; Gudauskis, M. Indoor Navigation Systems for Visually Impaired Persons: Mapping the Features of Existing Technologies to User Needs. Sensors 2020, 20, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, H.; Costa, P.; Filipe, V.; Paredes, H.; Barroso, J. A review of assistive spatial orientation and navigation technologies for the visually impaired. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2017, 18, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, A.J. Wearable Smart System for Visually Impaired People. Sensors 2018, 18, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzschmann, R.K.; Araki, B.; Rus, D. Safe Local Navigation for Visually Impaired Users with a Time-of-Flight and Haptic Feedback Device. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecílio, J.; Duarte, K.; Furtado, P. BlindeDroid: An Information Tracking System for Real-time Guiding of Blind People. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 52, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J.; Farcy, R. Optical Device Indicating a Safe Free Path to Blind People. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2011, 61, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalo, G.; Helena, S. Indoor Location System Using ZigBee Technology. In Proceedings of the 2009 Third International Conference on Sensor Technologies and Applications, Glyfada, Greece, 18–23 June 2009; pp. 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Karchňák, J.; Šimšík, D.; Jobbágy, B.; Onofrejová, D. Feasibility Evaluation of Wearable Sensors for Homecare Systems. Acta Mech. Slovaca 2015, 19, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeamwatthanachai, W.; Wald, M.; Wills, G. Indoor navigation by blind people: Behaviors and challenges in unfamiliar spaces and buildings. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 2019, 37, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yi, Y.; Ni, L.M. A Survey on Wireless Indoor Localization from the Device Perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 49, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.; Kouroupetroglou, G. Speech technologies for blind and low vision persons. Technol. Disabil. 2008, 20, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andò, B.; Baglio, S.; Lombardo, C.O.; Marletta, V. RESIMA—An Assistive System for Visual Impaired in Indoor Environment. In Biosystems & Biorobotics; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Qi, L.; El-Sheimy, N. Smartphone-Based Indoor Localization with Bluetooth Low Energy Beacons. Sensors 2016, 16, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaccour, K.; Eid, J.; Darazi, R.; el Hassani, A.H.; Andres, E. Multisensor Guided Walker for Visually Impaired Elderly People. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Advances in Biomedical Engineering (ICABME), Beirut, Lebanon, 16–18 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal, N.; Bostanci, E.; Currie, K.; Clark, A.F. A Navigation System for the Visually Impaired: A Fusion of Vision and Depth Sensor. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2015, 2015, 479857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Geng, E.; Ye, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lin, J.; Pang, Y. Indoor Positioning Algorithm Based on the Improved RSSI Distance Model. Sensors 2018, 18, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.-H.; Wan, Y.; Ng, B.-P.; See, C.-M.S. A Real-Time Indoor WiFi Localization System Utilizing Smart Antennas. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2007, 53, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, P.; Gang, H.-S.; Pyun, J.-Y. Bluetooth Based Indoor Positioning Using Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics—Asia (ICCE-Asia), Jeju, Korea, 24–26 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kanan, R.; Elhassan, O. A Combined Batteryless Radio and WiFi Indoor Positioning for Hospital Nursing. J. Commun. Softw. Syst. 2016, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.P.; Sousa, J.P.; Cunha, C.R.; Morais, E.P. An Indoor Navigation Architecture Using Variable Data Sources for Blind and Visually Impaired Persons. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Cáceres, Spain, 13–16 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marco, L.; Farinella, G.M. Computer Vision for Assistive Healthcare; Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780128134450. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, K.; Parmar, B. Assistive device using computer vision and image processing for visually impaired; review and current status. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, 17, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldini, A.; Fanfani, M.; Colombo, C. Smartphone-Based Obstacle Detection for the Visually Impaired. In Image Analysis and Processing ICIAP 2015; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 480–488. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-C.; Katzschmann, R.K.; Teng, S.; Araki, B.; Giarre, L.; Rus, D. Enabling independent navigation for visually impaired people through a wearable vision-based feedback system. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, R.; Tan, X.; Wang, R.; Qin, T.; Li, J.; Zhao, S.; Chen, E.; Liu, T.-Y. Lightspeech: Lightweight and Fast Text to Speech with Neural Architecture Search. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 5699–5703. [Google Scholar]

- Yusro, M.; Hou, K.-M.; Pissaloux, E.; Ramli, K.; Sudiana, D.; Zhang, L.-Z.; Shi, H.-L. Concept and Design of SEES (Smart Environment Explorer Stick) for Visually Impaired Person Mobility Assistance. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Karkar, A.; Al-Maadeed, S. Mobile Assistive Technologies for Visual Impaired Users: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computer and Applications (ICCA), Beirut, Lebanon, 25–26 August 2018; pp. 427–433. [Google Scholar]

- Phung, S.L.; Le, M.C.; Bouzerdoum, A. Pedestrian lane detection in unstructured scenes for assistive navigation. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2016, 149, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.S.; Mazumder, P.B.; Sharma, G.D. Comparison of drug susceptibility pattern of Mycobacterium tuberculosis assayed by MODS (Microscopic-observation drug-susceptibility) with that of PM (proportion method) from clinical isolates of North East India. IOSR J. Pharm. IOSRPHR 2014, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossé, P.S. A Plant Identification Game. Am. Biol. Teach. 1977, 39, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, L. Air Sonars with Acoustical Display of Spatial Information. In Animal Sonar Systems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 769–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.A.; Lightman, A. Talking Braille. In Proceedings of the 7th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility—Assets ’05, Baltimore, MD, USA, 9–12 October 2005; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Kuc, R. Binaural sonar electronic travel aid provides vibrotactile cues for landmark, reflector motion and surface texture classification. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2002, 49, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, I.; Borenstein, J. The GuideCane-applying mobile robot technologies to assist the visually impaired. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 2001, 31, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Abdoun, D.I.; Alsyouf, I.; Mushtaha, E.; Ibrahim, I.; Al-Ali, M. Developing and Designing an Innovative Assistive Product for Visually Impaired People: Smart Cane. In Proceedings of the 2022 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–24 February 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, K.L. Citation Precision. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1982, 36, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, B.; Waters, D. Mobility AT: The Batcane (UltraCane). In Assistive Technology for Visually Impaired and Blind People; Springer: London, UK, 2008; pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Villamizar, L.H.; Gualdron, M.; Gonzalez, F.; Aceros, J.; Rizzo-Sierra, C.V. A Necklace Sonar with Adjustable Scope Range for Assisting the Visually Impaired. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Osaka, Japan, 3–7 July 2013; pp. 1450–1453. [Google Scholar]

- Cardin, S.; Thalmann, D.; Vexo, F. A wearable system for mobility improvement of visually impaired people. Vis. Comput. 2006, 23, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, J.; Komatsu, T.; Ito, K.; Ono, T.; Okamoto, M. CyARM: Haptic Sensing Device for Spatial Localization on Basis of Exploration by Arms. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2009, 2009, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifukube, T.; Peng, C.; Sasaki, T. A blind mobility aid modeled after echolocation of bats. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1991, 38, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, S.; Borenstein, J.; Koren, Y. Mobile Robot Obstacle Avoidance in a Computerized Travel Aid for the Blind. In Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–13 May 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, P. An experimental system for auditory image representations. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1992, 39, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hub, A.; Diepstraten, J.; Ertl, T. Design and development of an indoor navigation and object identification system for the blind. ACM SIGACCESS Access. Comput. 2003, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.H.; Aguerrevere, D.; Barreto, A.B. A Pocket-PC Based Navigational Aid for Blind Individuals. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE Symposium on Virtual Environments, Human-Computer Interfaces and Measurement Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 12–14 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- González-Mora, J.L.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A.; Rodríguez-Ramos, L.F.; Díaz-Saco, L.; Sosa, N. Development of a New Space Perception System for Blind People, Based on the Creation of a Virtual Acoustic Space. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Sainarayanan, G.; Nagarajan, R.; Yaacob, S. Fuzzy image processing scheme for autonomous navigation of human blind. Appl. Soft Comput. 2007, 7, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, K.; Yang, K. Improving RealSense by Fusing Color Stereo Vision and Infrared Stereo Vision for the Visually Impaired. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information Science and System, Zhengzhou, China, 20–22 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. Tools and Technologies for Blind and Visually Impaired Navigation Support: A Review. IETE Tech. Rev. 2020, 39, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, R.; Freitas, D.; Coelho, A. Blind and Visually Impaired Visitors’ Experiences in Museums: Increasing Accessibility through Assistive Technologies. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2020, 13, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dian, Z.; Kezhong, L.; Rui, M. A precise RFID indoor localization system with sensor network assistance. China Commun. 2015, 12, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, I.-M.; Kim, S.-S.; Kim, S.-M. A portable mid-range localization system using infrared LEDs for visually impaired people. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2014, 67, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairuman, I.F.B.; Foong, O.-M. OCR Signage Recognition with Skew & Slant Correction for Visually Impaired People. In Proceedings of the 2011 11th International Conference on Hybrid Intelligent Systems (HIS), Melacca, Malaysia, 5–8 December 2011; pp. 306–310. [Google Scholar]

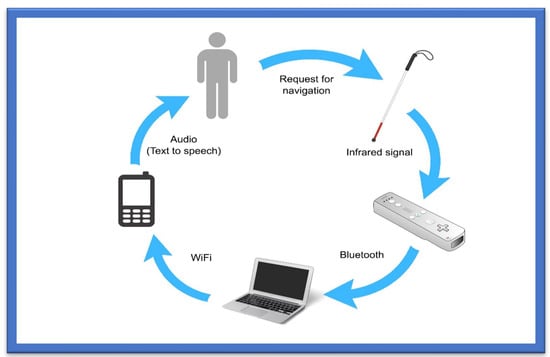

- Messaoudi, M.D.; Menelas, B.-A.J.; Mcheick, H. Autonomous Smart White Cane Navigation System for Indoor Usage. Technologies 2020, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Liu, D.; Su, G.; Fu, Z. A Cloud and Vision-Based Navigation System Used for Blind People. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Automation and Control Technologies—AIACT 17, Wuhan, China, 7–9 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oladayo, O.O. A Multidimensional Walking Aid for Visually Impaired Using Ultrasonic Sensors Network with Voice Guidance. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2014, 6, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, C.; Andrea, B.; Giovanni, M.; Paolo, M. Experiencing Indoor Navigation on Mobile Devices. IT Prof. 2013, 16, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, N.; Lin, H.-W.; Chang, Y.-H. Design and Implementation of a Walking Stick Aid for Visually Challenged People. Sensors 2019, 19, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, S.S.; Sasiprabha, T.; Jeberson, R. BLI-NAV Embedded Navigation System for Blind People. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Space Technology Services and Climate Change 2010 (RSTS & CC-2010), Chennai, India, 13–15 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aladren, A.; Lopez-Nicolas, G.; Puig, L.; Guerrero, J.J. Navigation Assistance for the Visually Impaired Using RGB-D Sensor with Range Expansion. IEEE Syst. J. 2014, 10, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-F.; Chen, Y.-L. Syndrome-Enabled Unsupervised Learning for Neural Network-Based Polar Decoder and Jointly Optimized Blind Equalizer. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2020, 10, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Wu, D.; Dai, W.; Geng, S.; Ding, Q. A Wireless Sensor Network Based Personnel Positioning Scheme in Coal Mines with Blind Areas. Sensors 2010, 10, 9891–9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatlawande, S.S.; Mukhopadhyay, J.; Mahadevappa, M. Ultrasonic Spectacles and Waist-Belt for Visually Impaired and Blind Person. In Proceedings of the 2012 National Conference on Communications (NCC), Kharagpur, India, 3–5 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, A.D.P.; Medola, F.O.; Cinelli, M.J.; Ramirez, A.R.G.; Sandnes, F.E. Are electronic white canes better than traditional canes? A comparative study with blind and blindfolded participants. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 20, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicab Inc. BrainPort Technology Tongue Interface Characterization Tactical Underwater Navigation System (TUNS); Wicab Inc.: Middleton, WI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, H.; Harada, A.; Iwahashi, T.; Usui, S.; Sawamoto, J.; Kanda, J.; Wakimoto, K.; Tanaka, S. Network-Based Nationwide RTK-GPS and Indoor Navigation Intended for Seamless Location Based Services. In Proceedings of the 2004 National Technical Meeting of The Institute of Navigation, San Diego, CA, USA, 26–28 January 2004; pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Caffery, J.; Stuber, G. Overview of radiolocation in CDMA cellular systems. IEEE Commun. Mag. 1998, 36, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.A.; Vasquez, F.; Ochoa, S.F. An Indoor Navigation System for the Visually Impaired. Sensors 2012, 12, 8236–8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nivishna, S.; Vivek, C. Smart Indoor and Outdoor Guiding System for Blind People using Android and IOT. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, N.; Saha, R.K.; Zafar, R.B.; Bhuian, M.B.H.; Sarwar, S.S. Vibration and Voice Operated Navigation System for Visually Impaired Person. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Informatics, Electronics & Vision (ICIEV), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 23–24 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, P.W.; Thomsen, P.R.; Hoxie, T.; Wright, G. Filing a Patent Application. In Patents for Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals, and Biotechnology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rehrl, K.; Göll, N.; Leitinger, S.; Bruntsch, S.; Mentz, H.-J. Smartphone-Based Information and Navigation Aids for Public Transport Travellers. In Location Based Services and TeleCartography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 525–544. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Yeung, W.M.-C.; Ng, J.K.-Y. Enhancing Indoor Positioning Accuracy by Utilizing Signals from Both the Mobile Phone Network and the Wireless Local Area Network. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications (AINA 2008), Gino-Wan, Japan, 25–28 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rehrl, K.; Leitinger, S.; Bruntsch, S.; Mentz, H. Assisting orientation and guidance for multimodal travelers in situations of modal change. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems, Vienna, Austria, 13–16 September 2005; pp. 407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, V.; Olmschenk, G.; Seiple, W.H.; Zhu, Z. ASSIST: Evaluating the usability and performance of an indoor navigation assistant for blind and visually impaired people. Assist. Technol. 2020, 34, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.V.J.; Visu, A.; Raj, S.M.; Prabhu, T.M.; Kalaiselvi, V.K.G. Penpal-Electronic Pen Aiding Visually Impaired in Reading and Visualizing Textual Contents. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Technology for Education, Chennai, India, 14–16 July 2011; pp. 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis, J.M.; Klatzky, R.L.; Golledge, A.R.G. Navigating without Vision: Basic and Applied Research. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2001, 78, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, K.G.; Porkodi, C.M.; Kanimozhi, K. Image Recognition for Visually Impaired People by Sound. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing, Melmaruvathur, India, 3–5 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Geetha, M.N.; Sheethal, H.V.; Sindhu, S.; Siddiqa, J.A.; Chandan, H.C. Survey on Smart Reader for Blind and Visually Impaired (BVI). Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latha, L.; Geethani, V.; Divyadharshini, M.; Thangam, P. A Smart Reader for Blind People. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2019, 8, 1566–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Gill, H.; Ou, S.; Lee, J. CCVoice: Voice to Text Conversion and Management Program Implementation of Google Cloud Speech API. KIISE Trans. Comput. Pr. 2019, 25, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Haruyama, S. New indoor navigation system for visually impaired people using visible light communication. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2013, 2013, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction to Amazon Web Services. In Machine Learning in the AWS Cloud; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 133–149.

- Khan, A.; Khusro, S. An insight into smartphone-based assistive solutions for visually impaired and blind people: Issues, challenges and opportunities. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 20, 265–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; Gao, F.; Zhao, X.; Xun, X.; Zhao, B.; Kang, Z.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, Y. Information accessibility oriented self-powered and ripple-inspired fingertip interactors with auditory feedback. Nano Energy 2021, 87, 106117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ishikawa, M.; Yamakawa, Y. An Active Assistant Robotic System Based on High-Speed Vision and Haptic Feedback for Human-Robot Collaboration. In Proceedings of the IECON 2018—44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Washington, DC, USA, 21–23 October 2018; pp. 3649–3654. [Google Scholar]

- Mon, C.S.; Yap, K.M.; Ahmad, A. A Preliminary Study on Requirements of Olfactory, Haptic and Audio Enabled Application for Visually Impaired in Edutainment. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th Symposium on Computer Applications & Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 27–28 April 2019; pp. 249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Core77.Com. Choice Rev. Online 2007, 44, 44–3669. [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.E. Soundscape. In Oxford Music Online; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, R. IBM SmartCloud Cost Management with IBM Cloud Orchestrator Cost Management on the Cloud. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing in Emerging Markets (CCEM), Bangalore, India, 19–21 October 2016; pp. 170–172. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Khan, M.; Tsangouri, C.; Yang, C.; Li, B.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, Z. CCNY Smart Cane. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 7th Annual International Conference on CYBER Technology in Automation, Control and Intelligent Systems (CYBER), Honolulu, HI, USA, 31 July–4 August 2017; pp. 1246–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Catalogue: In Les Pratiques Funéraires en Pannonie de l’époque Augustéenne à la fin du 3e Siècle; Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2020; p. 526.

- Dávila, J. Iterative Learning for Human Activity Recognition from Wearable Sensor Data. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Electronic Conference on Sensors and Applications, Online, 15–30 November 2016; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2016; p. 7. Available online: https://sciforum.net/conference/ecsa-3 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Kumpf, M. A new electronic mobility aid for the blind—A field evaluation. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 1987, 10, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, R. Evaluation of a Compact Helmet-Based Laser Scanning System for Aboveground and Underground 3d Mapping. ISPRS Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, XLIII-B2-2022, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, E.; Li, B.; Gallagher, T.; Dempster, A.G.; Rizos, C.; Ramsey-Stewart, E.; Woo, D. Indoor Navigation for the Blind and Vision Impaired: Where Are We and Where Are We Going? In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Sydney, Australia, 13–15 November 2012; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Satani, N.; Patel, S.; Patel, S. AI Powered Glasses for Visually Impaired Person. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2020, 9, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart object detector for visually impaired. Spéc. Issue 2017, 3, 192–195. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-E.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Wang, I.-F. BlindNavi: A Navigation App for the Visually Impaired Smartphone User. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI EA ’15, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. Female Genital Mutilation Awareness, CFAB, London, 2014. Available online: http://www.safeandsecureinfo.com/fgm_awareness/fgm_read_section1.html Female Genital Mutilation: Recognising and Preventing FGM, Home Office, London, 2014. Available free: http://www.safeguardingchildrenea.co.uk/resources/female-genital-mutilation-recognising-preventing-fgm-free-online-training. Child Abus. Rev. 2015, 24, 463–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolesa, L.D.; Chala, T.F.; Abdi, G.F.; Geleta, T.K. Assessment of Quality of Commercially Available Some Selected Edible Oils Accessed in Ethiopia. Arch. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, K. Working With Parents of School Aged Children: Staying in Step While Keeping a Step Ahead. Perspect. Hear. Hear. Disord. Child. 2000, 10, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, B.; Imbeault, F.; Bouzouane, A.; Menelas, B.A.J. Developing serious games specifically adapted to people suffering from Alzheimer. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Serious Games Development and Applications, Bremen, Germany, 26–29 September 2012; pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Menelas, B.A.J.; Otis, M.J.D. Design of a serious game for learning vibrotactile messages. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Workshop on Haptic Audio Visual Environments and Games (HAVE 2012), Munich, Germany, 8–9 October 2012; pp. 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Menelas, B.A.J.; Benaoudia, R.S. Use of haptics to promote learning outcomes in serious games. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2017, 1, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménélas, B.; Picinalli, L.; Katz, B.F.; Bourdot, P. Audio haptic feedbacks for an acquisition task in a multi-target context. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces (3DUI), Waltham, MA, USA, 20–21 March 2010; pp. 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Menelas, B.A.J.; Picinali, L.; Bourdot, P.; Katz, B.F. Non-visual identification, localization, and selection of entities of interest in a 3D environment. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2014, 8, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchakouté, L.D.C.; Gagnon, D.; Ménélas, B.A.J. Use of tactons to communicate a risk level through an enactive shoe. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2018, 12, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).