Abstract

Background: After the invasion of Ukraine, neighbouring countries were forced to find systemic solutions to provide medical care to those fleeing the war, including children, as soon as possible. In order to do this, it is necessary to know the communication problems with refugee minors and find proposals for their solutions. Methods: A systematic review of the literature from 2016 to 2022 was conducted according to PRISMA criteria. Results: Linguistic diversity and lack of professional readiness of teachers are the main constraints hindering the assistance of refugee children in schools. Problems during hospitalization include lack of continuity of medical care and lack of retained medical records. Solutions include the use of the 3C model (Communication, Continuity of care, Confidence) and the concept of a group psychological support program. Conclusions: In order to provide effective assistance to refugee minors, it is necessary to create a multidisciplinary system of care. It is hoped that the lessons learned from previous experiences will provide a resource to help refugee host countries prepare for a situation in which they are forced to provide emergency assistance to children fleeing war.

1. Introduction

1.1. An Outline of the Escape of Refugees after the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

After weeks of tension and an escalation of the conflict in eastern Ukraine that began in 2014, Russian troops invaded Ukrainian territory on 24 February 2022. The escalation of the conflict has transformed the country’s already unstable situation into a full-scale state of emergency [1]. Major military attacks have been reported across Ukraine, including in the capital, Kyiv, and the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, among others. The situation remains extremely dangerous for everyone living in Ukraine, and the number of people forced to flee is rapidly increasing [2]. According to the 1 May 2022 update, it is estimated that more than 5.5 million refugees have fled to neighbouring countries since 24 February, and there is a continuing upward trend in this phenomenon. Additionally, more than 7 million Ukrainians are internally displaced within their country [3]. The majority of refugees are women and children (the latter group accounting for 40% of the refugee population), the majority of adult men crossing the border appear to be from outside Ukraine due to the ban on men with Ukrainian citizenship leaving the country. There are also reports of vulnerable and marginalized refugee groups, including the elderly, people with disabilities and ethnic minorities [4]. In the face of the refugee crisis resulting from the aforementioned conflict, several countries have had to confront the refugee crisis for the first time, including Poland, Romania, Moldova and Slovakia (Figure 1) [3]. Particular attention should be paid in the case of minors, for whom the situation of fleeing a country is often the first moment of losing a sense of security in their lives.

Figure 1.

Polulation movement and displacement of refugees from Ukraine to neightbouring countries (as of 15 March 2022) (Reprinted from [3]).

1.2. General Information on the Role of Communication in Medicine

The role of communication in medicine was studied and described back in the 20th century. The results of a 1995 systematic review showed a correlation between effective doctor–patient communication and improved patient health outcomes [5]. Later studies confirmed that both trust and communication in medicine were positively associated with patient satisfaction and perceived quality of healthcare services in terms of better adherence to medical recommendations, leading to better therapeutic outcomes of treatment and better perceived quality of healthcare services [6]. Practitioners who work to improve the way they express empathy and communicate positive messages are likely to result in improvements in the mental and physical state of many patients and improve their overall satisfaction with their care [7].

At the same time, studies have outlined the effects of poor communication. It has been found that poor communication can lead to a variety of negative consequences: lack of continuity of care, compromised patient safety, patient dissatisfaction and inefficient use of valuable resources, both in unnecessary research and physician time and economic consequences [8]. For example, communication difficulties played a role in the vast majority of medical accidents experienced by participants in a 2004 study [9]. Furthermore, the problem of communication may relate to the provision of continuity of medical care. Nurses participating in one study noted many deficiencies in transitions from hospital to specialised care facilities required repeated telephone explanations, caused delays in care (including delays in pain control), increased staff stress, frustrated individuals and family members, and directly contributed to a negative image of the specialised care facility and increased risk of hospital readmission [10]. In turn, inadequate coordination between institutions involved in assisting victims in an extreme situation, including health care, results in loss of resources, increased expenditure on assistance and often poor quality of healthcare [11].

With reference to the benefits of proper communication in medicine and the negative consequences in the case of poor and uncoordinated communication, systemic solutions should be sought to simultaneously provide medical assistance to fleeing refugees while preventing a reduction in the quality of the services provided to citizens of countries receiving refugees. With the sudden influx of such a large number of people in such a short space of time, it is essential to develop a management strategy to help as many people as possible in the most effective way. Particular care should be given to fleeing children, for whom the war situation will leave long-term consequences in terms of physical and mental health [12]. By having countries that have had to deal with the refugee crisis in the 21st century, their experiences should be used to outline the most important pillars for helping refugee minors.

In order to achieve good communication in medical facilities during the influx of paediatric refugees into the host country, it is additionally necessary to learn about the differences in the characteristics of the psychological profile between refugee minors and their peers from a war-affected country, and to find out what challenges the health system of the host country faces and what role non-medical facilities close to the refugee can play in assisting medical facilities in their activities. We believe that the knowledge gained will allow institutions to prepare in advance to effectively assist paediatric refugees, as they will know in advance what health and psychological problems underage refugees may present with, and will allow the better coordination of healthcare activities between the institutions themselves, increasing the quality of medical services and reducing hospitalisation times.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this paper is to report on the topic of communication between refugee minors and health care workers and other public actors from countries experiencing a refugee crisis. A systematic review of the scientific literature from 2016 to 2022 was conducted using PubMed and ResearchGate search engines, followed by a selection according to PRISMA-S Checklist criteria [13].

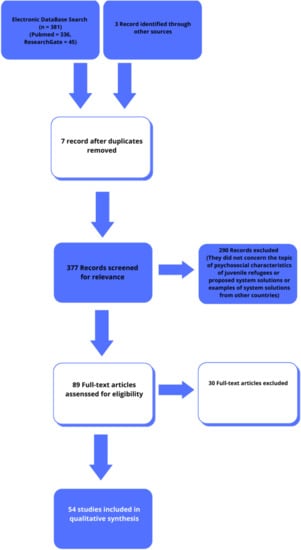

The thematic search involved finding scientific articles in the PubMed database from the years 2016 to 2022 (a period of increased number of papers emerging on paediatric refugee patients) meeting the criteria: [health care] AND [paediatric refugee], for ResearchGate: [paediatric] AND [refugee] AND [health care] in order to find articles meeting the article’s objectives as accurately as possible. In addition, 3 articles meeting the topic of the paper from other sources (Google Scholar) were included in the review. The search was restricted to English-language articles. Duplicate articles were removed and the abstracts of the received articles were reviewed. The co-authors selected papers containing relevant data on one of the three topics addressed in the paper: issues and characteristics of the health and psychological profile of refugee minors, difficulties related to the refugee crisis in different countries of the world, and proposals for systemic solutions to prepare a country at risk of a sudden influx of refugee minors. The article proposal lists were presented to the other co-authors dealing with the relevant subsections of the thesis, who decided to include a number of articles finally selected for review of the full versions of the articles contributing relevant content to the thesis. Detailed numerical information is provided in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Table 1.

Summary of scientific articles used in the systematic review.

Figure 2.

Figures from the systematic review (based on [13]).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Health and Psychosocial Situation of the Refugee Minor

The general health status of refugee children is worse than that of non-immigrant children. Infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, measles, malaria, hepatitis B, HIV and intestinal parasites are considered to be among the more serious health problems. An increased prevalence of syphilis and polio virus has also been reported [14,15]. In the study group, 33% of which were Syrian refugees, followed by Afghan and Egyptian refugees, it was found that only 35.8% of children were fully vaccinated against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and MMR. Vaccination rates against hepatitis B, pneumococcal, polio, chickenpox and HIB were much lower, not exceeding 17% [16].

A positive correlation was observed between the incidence of tuberculosis and the percentage of immigrants living in the region [17].

Infections are the most common cause of hospitalisation of refugee minors, and among children, respiratory infections are the most common (Syrian refugees) [18,19]. Studies on children permanently migrating to European countries have shown low vaccination rates against hepatitis B, chickenpox, measles, mumps, rubella and low immunity to tetanus and diphtheria. Additionally, many newborns born on the move may not have access to the screening for birth defects that is widely offered in European countries (mainly refugees from Afghanistan, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey) [20].

The high proportion of children with severe nutritional problems is also a significant problem. Lack of access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food results in a low intake of micronutrients, fibre, fruit and vegetables and a higher incidence of both overweight and obesity and malnutrition resulting in developmental disorders (refugees from Myanmar, Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran) [21,22].

Refugee children are at high risk of toxic stress, i.e., extreme, frequent and persistent adverse events without the presence of a supportive carer. These events include, but are not limited to, the death of a family member, a life-threatening illness, a natural or man-made disaster or a terrorist incident. There is often social isolation, discrimination and isolation from family members, which greatly affects the child’s mental health. The prevalence of mental illness among this group is high. Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety disorders are the most common [23,24]; 25% of refugee respondents (mainly Somalis, followed by Eritreans, Afghans and Syrians) experienced symptoms of PTSD [25].

Post-traumatic stress was also observed in 33% of Syrian children living in a refugee camp in Germany [26] (as of 2015). The average prevalence of anxiety disorders and major depression in conflict-affected populations is estimated to be two to four times higher than the estimated global prevalence. Minor refugees affected by armed conflict are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, sexual violence and the breakdown of family structures [27]. They may also exhibit a wide range of stress reactions including specific anxiety, prolonged crying, lack of interest in their surroundings, psychosomatic symptoms and aggressive behaviour [28].

In a refugee camp in Turkey, the rate of depression was 60%, and symptoms such as aggressive behaviour also appeared (22%). Similar disorders are observed in Bangladesh, which received Rohingya fleeing the genocide in 2017. Of the 342 children assessed, 97% were hyperactive and 85% had behavioural problems. Half of the respondents were unable to build relationships with their peers [29].

Children may also experience acculturative stress related to the difficulties that may arise in maintaining their own traditions in a foreign environment and religious customs including, but not limited to, preparation for prayer (Afghan refugees) [30].

In studies, refugee minors also indicated negative perceptions of mental illness, the stigma that goes with it, and fear of the social consequences of having such an illness [31].

Among newly arrived refugees, almost 30% of patients were diagnosed with two or more conditions, demonstrating the complex diversity of conditions. The important role of family physicians in the ongoing care, as well as the comprehensive assessment of the health status of immigrants upon arrival in a new country (mainly refugees from Burma, Sudan, Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Thailand) is highlighted [32]. The quality of life of refugee children is largely affected by the high number of uncorrected visual impairments, which in the long term may affect their development and success in school. Parents are less likely to have their children’s eyesight checked, through limited information about the medical care available to them, as well as limited access to expert eye care and literature on eye problems (Syrian refugees, Burmese refugees) [30,33].

Inadequate oral hygiene and resulting tooth decay is also a serious problem among refugee and immigrant children. The main factors influencing its development are cultural differences and lack of knowledge of protective factors, but also financial constraints. Language and dental experience in the home country are also barriers [14,34]. The diagnosis of diabetes and its treatment among paediatric refugees has also become a challenge for Europe. Compared to the native population, refugees have been reported to have higher rates of severe hypoglycaemia, poorer diabetes control, and a higher incidence of long-term complications: microalbuminuria and diabetic retinopathy (mainly refugees from Africa, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan) [35].

In addition to the aforementioned health problems, one of the reasons for the need for urgent medical care is unintentional injuries. Refugee immigrants have a 20% higher rate of unintentional injuries compared to non-refugee immigrants [36]. Surgical care in refugee children also includes routine surgical problems such as inguinal hernia and appendicitis, non-war-related injuries and gynaecological problems [16].

Among paediatric refugees, there is also a group of patients suffering from rare genetic diseases including Noonan syndrome, Laron syndrome, mitochondriopathy, Turner syndrome and arthrogryposis. They constitute a small but equally important group requiring regular medical consultations (Syrian, Eritrean, Afghan, Armenian, Somali, Algerian and Russian refugees) [37].

Another aspect is skin diseases, which are common among displaced populations. There may also be few or largely limited access to dermatologists in the host country, due to the distance of specialists from the refugee camp and thus the cost of transport [38]. Within weeks or even months of delays from medical diagnosis, skin infections may progress to a generalised form or cause an epidemic among the local community (African refugees) [39].

The specialised care of refugee patients is quite challenging due to the communication and language barrier, but also the lack of previous medical records, reports of past illnesses and surgical procedures (Syrian refugees) [40]. Another emerging difficulty is the many moves that often prevent continuity and accurate planning of further treatment [41]. Other stressors that inhibit the health-seeking behaviour of refugees are unfavourable housing and neighbourhood conditions, the challenges of interpreter services, the difficulty of navigating medical facilities, and the transportation to them themselves. These factors, as well as parents’ increasing depression and anxiety, prevent them from providing adequate medical care for their own children (Syrian refugees) [42].

3.2. Experiences from Recent Refugee Crises

Almost 85% of the world’s refugee population has been hosted in low- and middle-income developing countries. These countries, Lebanon, Jordan and Bangladesh among others, are unable to provide adequate living conditions for such a large number of admitted refugees and face a heavy burden on their health systems [43].

Data from Lebanon indicate that Syrian refugee children are very often injured while living in refugee camps. The most common type of injury was burns, which have been proven to be clearly due to the low socio-economic status of Syrian refugee families and poor housing conditions (e.g., flammable tents, heating and cooking on open fires, overcrowding). In addition, refugees have limited access to health care, lack insurance and the ability to cover medical costs. In Lebanon, there is a lack of systemic interventions to improve this situation, in contrast to numerous high-income countries where significant funding has been allocated for prevention, burns treatment and aftercare [44].

Statistics show that around 83% of refugee families in Lebanon have at least one person who suffers from a chronic illness, putting a significant strain on Lebanon’s already underfunded health system. One study analysed data on Syrian refugee children with heart defects. It noted that there is an increased rate of severe CHD among refugee children due to lack of access to health care, with only children with severe symptoms being able to receive medical attention. In developing countries, fewer patients reach adulthood due to delayed diagnosis, and inability to start or complete treatment. All costs associated with this examination and treatment of Syrian children with heart defects have been covered by non-governmental organisations (UNHCR, Brave Heart Fund, and GOLI), and medical professionals have often waived their salaries [45].

Another form of assistance to refugees is NGO-organised medical missions in Jordan such as the short-term SAMS medical mission in a camp for underage Syrian refugees. Infectious diseases and GDO infections were most common among the children treated. This was facilitated by the living conditions in the camp, including overcrowding, lack of access to drinking water and hygiene products. Typically, infections were severe due to delayed diagnosis and difficult treatment conditions—doctors received patients in tents without specialised equipment [46].

One study in Bangladesh highlighted the widespread lack of palliative care for refugees in humanitarian relief, an essential component during a humanitarian crisis. Many patients are experiencing pain and suffering due to severe injuries and illnesses, yet national regulations limit access to powerful painkillers. Neither the government nor NGOs are showing action to improve this situation. Among the refugees surveyed, as many as 62% (n = 96) experienced significant pain (62%, n = 96) and in 70% (n = 58), the prescribed treatments were ineffective (70%, n = 58). A total of 39.1% reported a need for medication and only 52.5% (n = 32) among them received their medication; 52.6% reported needing medical equipment and 72.0% (n = 59) of these patients did not have access to it [47].

In contrast to developing countries, highly developed countries face, usually, quite different problems regarding refugees. As a rule, they are provided with decent living conditions and care, but systemic solutions that are not fully effective are a problem.

According to the 2016 Australian guidelines, every arriving refugee must undergo a comprehensive health assessment. A medical examination is mandatory for all refugees and asylum seekers and should be conducted within 1 month of arrival in Australia. TB and Hepatitis B screening and booster vaccinations are also part of this procedure. These comprehensive screenings are carried out within the primary health care setting and with the assistance of nurses from the Special Refugee Health Program, who are also tasked with facilitating access to health care for newly arrived refugees. Refugees with confirmed active TB are treated prior to travel, and those with early or latent TB are referred to TB centres for follow-up in separate health facilities [48]. However, any asylum seeker must initially be placed in a special guarded facility and after an unspecified period of time be transferred to community custody. This process delays diagnosis and treatment (the median duration of detention was 7 months); moreover, multiple relocations do not allow for continuity of medical care. During detention, refugees do not have access to medical, psychological and educational services. An important case demonstrating the living conditions in community detention is the result of a 2014 Australian Human Rights Commission investigation. It showed that in detention, the majority of children experience physical and sexual assaults and there are numerous cases of self-harm and suicide [49].

Some inconsistency in health care for asylum seekers has been shown in Finland. The Finnish health care system for refugees is separate from general health care and funded by the immigration service. However, asylum seekers under the age of 18 have the same access to health services as Finnish children, including school health care. Despite this, the municipal authorities managing the medical facilities in their area have not provided services to refugees, have not been involved in combating infectious disease outbreaks and have denied public health services to refugee children. As a consequence, immigration services were forced to organise and pay for medical services in private facilities, where they were often incomplete or of poor quality. Even the introduction of further guidelines by the Finnish government did not influence the decisions of municipal authorities [50].

An important aspect concerning the lives of refugees in highly developed countries is marginalisation, discrimination and racism. In European countries, i.e., Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands, the risk of immigrants being assaulted was much higher than in Canada or the USA [51].

Using Spain as an example, it can be concluded that unstable living situations and frequent relocation, limit access to healthcare and prevent continuity of treatment. In the study conducted, approximately 83% of the immigrants surveyed completed the entire treatment process, while only 22% completed the hepatitis B vaccination schedule. It should be noted that the medical care and vaccination offered were free of charge, and the failure of the treatment process was most likely due to the unfavourable factors mentioned earlier [52].

3.3. Systemic Solutions for Refugee Care

Adapting the Health Care System

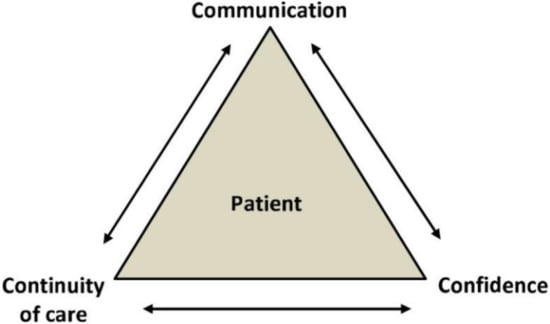

Migrants and refugees have specific health needs while facing a number of barriers to accessing the health care system. Research indicates that language and cultural barriers have a negative impact on the healthcare of people with limited knowledge of the language spoken in the country, resulting in limited access, higher hospital admissions, increased risk of permanent damage and limited health knowledge due to communication difficulties [53]. In this context, it is important that medical professionals are adapted to work with migrants and refugees. A working model based on the 3C Model is useful for this purpose (Figure 3) [54]. Of the three, proper communication is identified as the most important. It is required to understand the patient’s problem and allows for the exchange of information about symptoms, presumed diagnosis, required diagnostic tests, treatment and prognosis [55]. In a pan-European survey of paediatric emergency workers, 60% indicated that language and translation problems are one of the most important barriers to providing care to immigrant children [56]. A second important factor is the continuity of health care dependent on refugees being informed and educated about the health care system of the country they are in, the ease of access to health care system facilities, the inclusion of medical appointments in the refugees’ personal schedule and the cooperation of different institutions and providers [54]. Concepts such as ‘family doctor’ and ‘preventive health care’ may be incomprehensible to some people, so clarification of such terms is necessary to ensure continuity of health care [57]. As refugees may have limited access to transport, it is beneficial to integrate medical visits with other visits related to the asylum process or education [58]. The last component of the model is trust. There are two main components: the development of trust in someone or something and the ability to control the situation. It is important to remember that establishing a trusting relationship is a two-way process and requires mutual education. In order to be in control of healthcare decisions, it is necessary to understand the facts and apply one’s own health beliefs and priorities to decision making. The ability to feel self-efficacy and anticipate decisions has been described as particularly important in refugee mental health [54].

Figure 3.

Diagram of model 3C [54].

Interpreter services play a key role in the healthcare system. An interpreter is a communication specialist trained to translate everything that is said, maintain confidentiality, ensure transparency and point out cultural differences that impede communication [54]. The use of professional interpreters in person results in a shorter total emergency department time compared to the use of professional interpreters over the phone [59].

Refugees, especially children, are exposed to multiple mental health risks. Repeated trauma in turn puts the refugee child at high risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, somatisation disorder and depression [60]. To address mental health problems such as PTSD, depression, behavioural problems and anxiety among refugee minors, the effectiveness of a psychological support programme was tested in a group of 32 participants. Each session lasted 70–90 min, the students were divided 8–10 to two teachers. An improvement in trauma-related symptoms was noted. The greatest reduction in symptoms was observed on the anxiety and intrusive symptoms scale. No significant changes in the categories of peer problems, behaviour and hyperactivity (Table 2) [61].

Table 2.

Class topics of the Turkish psychological support programme for refugees [61].

3.4. Medical Innovations in Working with Refugees

Estimates of the prevalence of PTSD among adolescent refugees range from 11 to 75 percent, while depression ranges from 4 to 47% [62]. In order to provide help for a condition as severe as depression, it is important to diagnose it early. Advances in medical information technology (health-IT) are enabling the development of multifaceted interventions that include provider training, screening and notification, and clinical decision support, which may be more effective than any single intervention to improve mental health outcomes in primary care [63]. Modern technologies can be adapted and used for any patient group with limited native language skills, but it is worth ensuring that the application is compatible with the patient’s cultural code.

It is also beneficial to include the targeted community in the development of solutions. This was demonstrated by the example of developing, according to the community-based participatory research (CBPR) model, an innovative vaccine education technology using virtual reality. The project targeted Somali refugees. The community was involved through a series of discussions, interviews with Somali parents, workshops and the use of virtual reality techniques in teaching [64].

3.5. Integration of School-Age Children

Refugee children often have learning and developmental problems, but come for help too late, failing to take advantage of early intervention or school and social support available in developed countries. Risk factors for problems at school include the experience of trauma (before or after migration), interrupted learning, low teacher expectations of school achievement, financial problems in the household, while protective factors include knowledge of the language of instruction in the new country, adequate recognition of the child’s educational experience by the school team, appropriate assessments and expectations, parental support in the education process and a high level of parental education [65].

The Turkish General Directorate of Teacher Training and Education has launched a series of national in-service training workshops on inclusive education, specifically the education of Syrian refugee children, children with disabilities and children affected by violence, immigration or natural disasters. The introduction of visuals, games or stories for Syrian children with Turkish subtitles has been shown to assist their integration into their new school environment [66]. In order to avoid Syrian children being ignored by Turkish children, it has been shown that educational efforts should be focused on integrating children of both nationalities, and that the work of a school psychologist is effective in removing any prejudice in Turkish children [67].

The health status of children and adolescents is significantly influenced by school nurses, who are the first of the health professionals to encounter refugee children and adolescents. Therefore, they may have a particular role in supporting them during such a difficult time. A qualitative study conducted in 2019 among Swedish nurses found that they need to expand their skills in recognising the needs of people in crisis and after traumatic events, expanding their knowledge of the culture of the refugee child’s country of origin [66].

4. Discussion

The fluctuating situation and the increasing number of displaced persons pose humanitarian and logistical challenges to the health systems of refugee-hosting countries. For example, Ukrainian refugees may face barriers to healthcare upon arrival in both transit and destination countries.

This review highlights the importance of changing the mindset between a paediatric refugee patient and a patient who has not experienced fleeing war. The authors of the study repeatedly highlighted the situation where, together with the arriving patient, the local health system had to face de facto problems of the health system of the country from which the refugee came, if only in the context of immunization [14,15,16]. Contrary to appearances, problems resulting from the lack of primary prevention do not only concern the poorest countries such as Syria or Afghanistan [20]. In addition, in the case of Ukrainian refugees, as a result of the low vaccination rate of the population compared to richer countries, patients may arrive with diseases already marginally diagnosed, such as measles or polio, as there were outbreaks of these diseases in Ukraine before the Russian invasion (in 2019 and 2021, respectively) [68,69,70,71]. There is also a risk of more patients with more advanced and less prognosis chronic diseases. Therefore, in our opinion, it is extremely important to review epidemiological reports from refugee countries so as to be ready for the need to combat diseases that are less common in the native population or the need to treat various diseases that are much less promising.

The experience of countries that have had to deal with the need to take in refugees in the past decade shows that there is a large spectrum of problems in providing assistance to displaced persons depending on the wealth of the country. While elementary health care needs, i.e., prevention, burn and post-burn care, availability of doctors or palliative care, are not being met in the poorest countries [44,46,47], in rich countries, attention has been drawn to difficulties in maintaining continuity of health care, availability of interpreters for displaced persons or lack of retained medical records [40,49,52]. The examples given highlight the complexity of the problem and the need to develop effective systemic solutions to improve the effectiveness of assistance to minors in both the poorest and richest regions of the world.

In order to provide effective assistance, it is necessary both to ensure rapid communication within the ward and between hospital departments, which requires financial outlays for, among other things, hiring interpreters, and to create a system in which the patients’ records are available in other facilities in the country or region, e.g., the European Union [59]. It is worthwhile to use such simple practice models as the 3Cs, through which priorities and the basis for building good relationships with foreign-speaking patients can be established more quickly [44]. It is also worthwhile to improve the Turkish psychological support programme for refugees so that it also addresses the issues of peer problems and hyperactivity of refugee minors [61].

The important role of the school in the process of integrating students must not be forgotten. The involvement of medical professionals working there, e.g., school psychologists and nurses, should be used to break down barriers between children speaking different languages to each other [66,67]. In addition, the role of teachers should be emphasised, as frontline workers, who could refer children in need of psychological help to facilities and places specialised in therapies for traumatised patients (e.g., psychological offices). As a result, refugee minors would gain more trust in state institutions, including those dealing with health care, so that they would report their health complaints more quickly and obtain professional medical help more quickly, which would ultimately lead to a bottom-up improvement in the communication of the refugee minor with the health care professional. Combined with the top-down facilities in hospital wards mentioned in the paragraph above, it would become possible to create a three-tier system that maximises the aspects of effective and rapid health assistance to refugee minors (Figure 4) [41,54,60,61,67,72].

Figure 4.

Proposal for a three-step system to improve communication between paediatric patients and medical facilities.

5. Conclusions

The problem raised calls for systemic changes that are necessary to effectively help refugees. Let us not forget that today’s young patients are a group of intelligent and valuable people who, in a few years or so, may repay the societies that receive them in an emergency situation with their work, for example, filling jobs in professions that are understaffed in the country that has duly taken them in. We believe that the effort made to improve communication in medicine will bring with it long-term positive effects in every country where minors are helped.

Author Contributions

J.K.—conception of the scientific paper, systematic review in accordance with PRISMA criteria, writing—author of the abstract, discussion and summary; N.K., A.G. (Aleksandra Grzywacz), A.G. (Arkadiusz Grunwald), K.K. and M.M.—writing—authors of the introduction and results of the systematic review; M.S.—drafting the outline and scheme of the paper, reviewing and editing, substantive supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Jolanta Klas for verifying the linguistic correctness of the content of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haukkala, H. From Cooperative to Contested Europe? The Conflict in Ukraine as a Culmination of a Long-Term Crisis in EU–Russia Relations. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 2015, 23, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevel, O. Migration, Refugee Policy, and State Building in Postcommunist Europe; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 134–194. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization—Regional Office for Europe. Ukraine Crisis Public Health Situation Analysis—Refugee-Hosting Countries 17 March 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2022. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/352494/WHO-EURO-2022-5169-44932-63918-eng.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Additional UNICEF Supplies on Their Way to Ukraine as Number of Child Refugees Exceeds 1 Million Mark. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/additional-unicef-supplies-their-way-ukraine-number-child-refugees-exceeds-1-million (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Stewart, M.A. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1995, 152, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Mohaammadnezhad, M.; Ward, P. Trust and Communication in a Doctor-Patient Relationship: A Literature Review. J. Healthc. Commun. 2018, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.; Moscrop, A.; Mebius, A.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Lewith, G.; Bishop, F.L.; Mistiaen, P.; Roberts, N.W.; Dieninytė, E.; Hu, X.-Y.; et al. Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. R. Soc. Med. 2018, 111, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeir, P.; Vandijck, D.; Degroote, S.; Peleman, R.; Verhaeghe, R.; Mortier, E.; Hallaert, G.; Van Daele, S.; Buylaert, W.; Vogelaers, D. Communication in healthcare: A narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 69, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Lewton, E.; Rosenthal, M.M. Communication Failures: An Insidious Contributor to Medical Mishaps. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.J.; Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A.; Roiland, R.A.; Polnaszek, B.E.; Bowers, B.; Kind, A. The Consequences of Poor Communication During Transitions from Hospital to Skilled Nursing Facility: A Qualitative Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, R.; Norris, T.; Parry, D. Pinpointing What is Wrong with Cross-Agency Collaboration in Disaster Healthcare. J. Int. Soc. Telemed. eHealth 2018, 6, e3. Available online: https://ojstest.ukzn.ac.za/index.php/JISfTeH/article/view/354 (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Rizkalla, N.; Mallat, N.K.; Arafa, R.; Adi, S.; Soudi, L.; Segal, S.P. “Children Are Not Children Anymore; They Are a Lost Generation”: Adverse Physical and Mental Health Consequences on Syrian Refugee Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Sanz, A.; Leiva-Gea, I.; Martin-Alvarez, L.; del Torso, S.; van Esso, D.; Hadjipanayis, A.; Kadir, A.; Ruiz-Canela, J.; Perez-Gonzalez, O.; Grossman, Z. Migrant children’s health problems, care needs, and inequalities: European primary care paediatricians’ perspective. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 44, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbl, R.; Grois, N.; Popow, C.; Somekh, E.; Ehrich, J. Pediatric Healthcare for Refugee Minors in Europe: Steps for Better Insight and Appropriate Treatment. J. Pediatr. 2018, 197, 323–324.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucas, M.; Loucas, R.; Muensterer, O.J.; Hampel, A.; Solbach, P.; Cornberg, M.; Schmidt, E.R.; Behrens, G.M.; Jablonka, A.; Wu, V.K.; et al. Surgical Health Needs of Minor Refugees in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 28, 060–066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritschi, N.; Schmidt, A.J.; Hammer, J.; Ritz, N.; Swiss Pediatric Surveillance Unit. Pediatric Tuberculosis Disease during Years of High Refugee Arrivals: A 6-Year National Prospective Surveillance Study. Respiration 2021, 100, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, H.; Akcaboy, M.; Oztek-Celebi, F.Z.; Polat, E.; Sari, E.; Acoglu, E.A.; Oguz, M.M.; Kesici, S.; Senel, S. Analysis of Refugee Children Hospitalized in a Tertiary Pediatric Hospital. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 23, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampouras, A.; Tzikos, G.; Partsanakis, E.; Roukas, K.; Tsiamitros, S.; Deligeorgakis, D.; Chorafa, E.; Schoina, M.; Iosifidis, E. Child Morbidity and Disease Burden in Refugee Camps in Mainland Greece. Children 2019, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, A.; Battersby, A.; Spencer, N.; Hjern, A. Children on the move in Europe: A narrative review of the evidence on the health risks, health needs and health policy for asylum seeking, refugee and undocumented children. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2019, 3, bmjpo-2018-000364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroening, A.L.; Dawson-Hahn, E. Health Considerations for Immigrant and Refugee Children. Adv. Pediatr. 2019, 66, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.; O’Donovan, K.; Bear, N.; Robertson, A.; Mutch, R.; Cherian, S. Nutritional assessment of resettled paediatric refugees in Western Australia. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 55, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkensee, C.; Andrew, R. Health needs of accompanied refugee and asylum-seeking children in a UK specialist clinic. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2396–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.S. Toxic stress and child refugees. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 23, e12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloning, T.; Nowotny, T.; Alberer, M.; Hoelscher, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Froeschl, G. Morbidity profile and sociodemographic characteristics of unaccompanied refugee minors seen by paediatric practices between October 2014 and February 2016 in Bavaria, Germany. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yayan, E.H.; Düken, M.E.; Özdemir, A.A.; Çelebioğlu, A. Mental Health Problems of Syrian Refugee Children: Post-Traumatic Stress, Depression and Anxiety. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 51, e27–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendavid, E.; Boerma, T.; Akseer, N.; Langer, A.; Malembaka, E.B.; Okiro, A.E.; Wise, P.H.; Heft-Neal, S.; Black, R.E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; et al. The effects of armed conflict on the health of women and children. Lancet 2021, 397, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgin, D.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Doyle, M.; Eliez, S.; Fegert, J.M.; Fuentes, J.; Hebebrand, J.; Hillegers, M.; Karwautz, A.; Kiss, E.; et al. Impact of war and forced displacement on children’s mental health—Multilevel, needs-oriented, and trauma-informed approaches. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.Z.; Shilpi, A.B.; Sultana, R.; Sarker, S.; Razia, S.; Roy, B.; Arif, A.; Ahmed, M.U.; Saha, S.C.; McConachie, H. Displaced Rohingya children at high risk for mental health problems: Findings from refugee camps within Bangladesh. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 45, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J.; Leung, J.K.; Harris, K.; Abdullah, A.; Rohbar, A.; Brown, C.; Rosenthal, M.S. Recently-Arrived Afghan Refugee Parents’ Perspectives about Parenting, Education and Pediatric Medical and Mental Health Care Services. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 24, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Yameen, T.A.; Abadeh, A.; Lichter, M. Visual impairment and unmet eye care needs among a Syrian pediatric refugee population in a Canadian city. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 54, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, P.J.; Lanfranco, P.J.; Sneath, E.; Wade, A.J.; Huffam, S.; Pollard, J.; Standish, J.; McCloskey, K.; Athan, E.; O’Brien, D.P.; et al. Health issues of refugees attending an infectious disease refugee health clinic in a regional Australian hospital. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 47, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.E.; Al Azdi, Z.; Islam, K.; Kabir, A.E.; Huque, R. Prevalence of Eye Problems among Young Infants of Rohingya Refugee Camps: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, E. The Importance of Oral Health in Immigrant and Refugee Children. Children 2019, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, N.; Konrad, K.; Brack, C.; Hahn, E.; Herbst, A.; Icks, A.; Grulich-Henn, J.; Jorch, N.; Kastendieck, C.; Mönkemöller, K.; et al. Diabetes care in pediatric refugees from Africa or Middle East: Experiences from Germany and Austria based on real-world data from the DPV registry. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, N.R.; MacPherson, A.; Guan, J.; Guttmann, A. Unintentional injuries among refugee and immigrant children and youth in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cross-sectional study. Inj. Prev. 2017, 24, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buser, S.; Brandenberger, J.; Gmünder, M.; Pohl, C.; Ritz, N. Asylum-Seeking Children with Medical Complexity and Rare Diseases in a Tertiary Hospital in Switzerland. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 23, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, A.P.; Rehmus, W.; Chang, A.Y. Skin diseases in displaced populations: A review of contributing factors, challenges, and approaches to care. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, R.; Shemesh, Y.; Nitzan, O.; Azrad, M.; Peretz, A. Tinea capitis in an immigrant pediatric community; a clinical signs-based treatment approach. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- User, I.R.; Ozokutan, B.H. Common pediatric surgical diseases of refugee children: Health around warzone. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2019, 35, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baauw, A.; Rosiek, S.; Slattery, B.; Chinapaw, M.; van Hensbroek, M.B.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Holthe, J.K.-V. Pediatrician-experienced barriers in the medical care for refugee children in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, R.M.; Schumacher, D.J.; Cicek-Okay, S.; Jernigan, S.; Beydoun, A.; Salem, T.; Vaughn, L.M. Beliefs, perceptions, and behaviors impacting healthcare utilization of Syrian refugee children. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joury, E.; Meer, R.; Chedid, J.C.A.; Shibly, O. Burden of oral diseases and impact of protracted displacement: A cross-sectional study on Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, S.; Pike, I.; Oneissi, A.; Zheng, A.; Abu-Sittah, G. Pediatric Burns among Refugee Communities in Lebanon: Evidence to Inform Policies and Programs. J. Burn Care Res. 2019, 40, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.; Rashed, M.; Azzo, M.; Tabbakh, A.; El Sedawi, O.; Hussein, H.B.; Khalil, A.; Bulbul, Z.; Bitar, F.; El Rassi, I.; et al. Congenital Heart Disease in Syrian Refugee Children: The Experience at a Tertiary Care Center in a Developing Country. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2021, 42, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.H.; Razeq, N.M.A.; AbdulHaq, B.; Arabiat, D.; Khalil, A.A. Displaced Syrian children’s reported physical and mental wellbeing. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2017, 22, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, M.; Power, L.; Petrova, M.; Gunn, S.; Powell, R.; Coghlan, R.; Grant, L.; Sutton, B.; Khan, F. Illness-related suffering and need for palliative care in Rohingya refugees and caregivers in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heenan, R.C.; Volkman, T.; Stokes, S.; Tosif, S.; Graham, H.R.; Smith, A.; Tran, D.; Paxton, G. ‘I think we’ve had a health screen’: New offshore screening, new refugee health guidelines, new Syrian and Iraqi cohorts: Recommendations, reality, results and Review. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 55, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanes, G.; Chee, J.; Mutch, R.; Cherian, S. Paediatric asylum seekers in Western Australia: Identification of adversity and complex needs through comprehensive refugee health assessment. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2019, 55, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, K.; Tiittala, P.; Keskimäki, I.; Helve, O. Refugee crisis in Finland: Challenges to safeguarding the right to health for asylum seekers. Health Policy 2019, 123, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.R.; Guan, J.; MacPherson, A.; Lu, H.; Guttmann, A. Association of Immigrant and Refugee Status with Risk Factors for Exposure to Violent Assault Among Youths and Young Adults in Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serre-Delcor, N.; Treviño-Maruri, B.; Collazos-Sanchez, F.; Pou-Ciruelo, D.; Soriano-Arandes, A.; Sulleiro, E.; Molina-Romero, I.; Ascaso, C.; Bocanegra-Garcia, C. Health Status of Asylum Seekers, Spain. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.K.; Jaffe, J.; Mutch, R. Overcoming Communication Barriers in Refugee Health Care. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 66, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberger, J.; Tylleskär, T.; Sontag, K.; Peterhans, B.; Ritz, N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries—The 3C model. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.A. Rising up to the challenge: Strategies to improve Health care delivery for resettled Syrian refugees in Canada. Univ. Tor. Med. J. 2016, 94, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schrier, L.; Wyder, C.; del Torso, S.; Stiris, T.; von Both, U.; Brandenberger, J.; Ritz, N. Medical care for migrant children in Europe: A practical recommendation for first and follow-up appointments. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, 178, 1449–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worabo, H.J.; Hsueh, K.-H.; Yakimo, R.; Worabo, E.; Burgess, P.A.; Farberman, S.M. Understanding Refugees’ Perceptions of Health Care in the United States. JNP J. Nurse Pract. 2016, 12, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Garcia, J.; Stein, A. The right location? Experiences of refugee adolescents seen by school-based mental health services. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylen, S.; Cherian, S.; Gill, F.; Leslie, G.D.; Wilson, S. Impact of professional interpreters on outcomes for hospitalized children from migrant and refugee families with limited English proficiency: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 1360–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodes, M.; Vostanis, P. Practitioner Review: Mental health problems of refugee children and adolescents and their management. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 60, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormez, V.; Kılıç, H.N.; Orengul, A.C.; Demir, M.N.; Mert, E.B.; Makhlouta, B.; Kınık, K.; Semerci, B. Evaluation of a school-based, teacher-delivered psychological intervention group program for trauma-affected syrian refugee children in Istanbul, Turkey. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.E.; Weinberger, S.J.; Harder, V.S. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a Mental Health Screening Tool for Newly Arrived Pediatric Refugees. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 23, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, D.H.; Rizzo, S.; Biegler, K.; Sim, S.E.; Nicholas, E.; Chandler, M.; Ngo-Metzger, Q.; Paigne, K.; Nguyen, D.V.; Mollica, R. Novel Health Information Technology to Aid Provider Recognition and Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Primary Care. Med. Care 2019, 57, S190–S196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streuli, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Mohamed, A.; Sharma, M.; Esmailian, M.; Sezan, I.; Farrell, C.; Sawyer, M.; Meyer, D.; El-Maleh, K.; et al. Development of a culturally and linguistically sensitive virtual reality educational platform to improve vaccine acceptance within a refugee population: The SHIFA community engagement-public health innovation programme. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minhas, M.F.F.R.S.; Graham, H.R.; Jegathesan, H.M.T.; Huber, M.P.M.F.J.; Young, F.E.; Barozzino, F.T. Supporting the developmental health of refugee children and youth. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 22, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musliu, E.; Vasic, S.; Clausson, E.K.; Garmy, P. School Nurses’ Experiences Working with Unaccompanied Refugee Children and Adolescents: A Qualitative Study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5, 2377960819843713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsli-Calamak, E.; Kilinc, S. Becoming the teacher of a refugee child: Teachers’ evolving experiences in Turkey. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 25, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO EpiBrief—A Report on the Epidemiology of Selected Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the European Region. 2018. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/370656/epibrief-1-2018-eng.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- WHO EpiData—A Monthly Summary of the Epidemiological Data on Selected Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the WHO European Region. 2019. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/394060/2019_01_Epi_Data_EN_Jan-Dec2018.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Roberts, L. Surge of HIV, tuberculosis and COVID feared amid war in Ukraine. Nature 2022, 603, 557–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Operational Public Health Considerations for the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in the Context of Russia’s Aggression towards Ukraine; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koller, S.H.; Verma, S. Commentary on cross-cultural perspectives on positive youth development with implications for intervention research. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).