Challenges in the Medical and Psychosocial Care of the Paediatric Refugee—A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

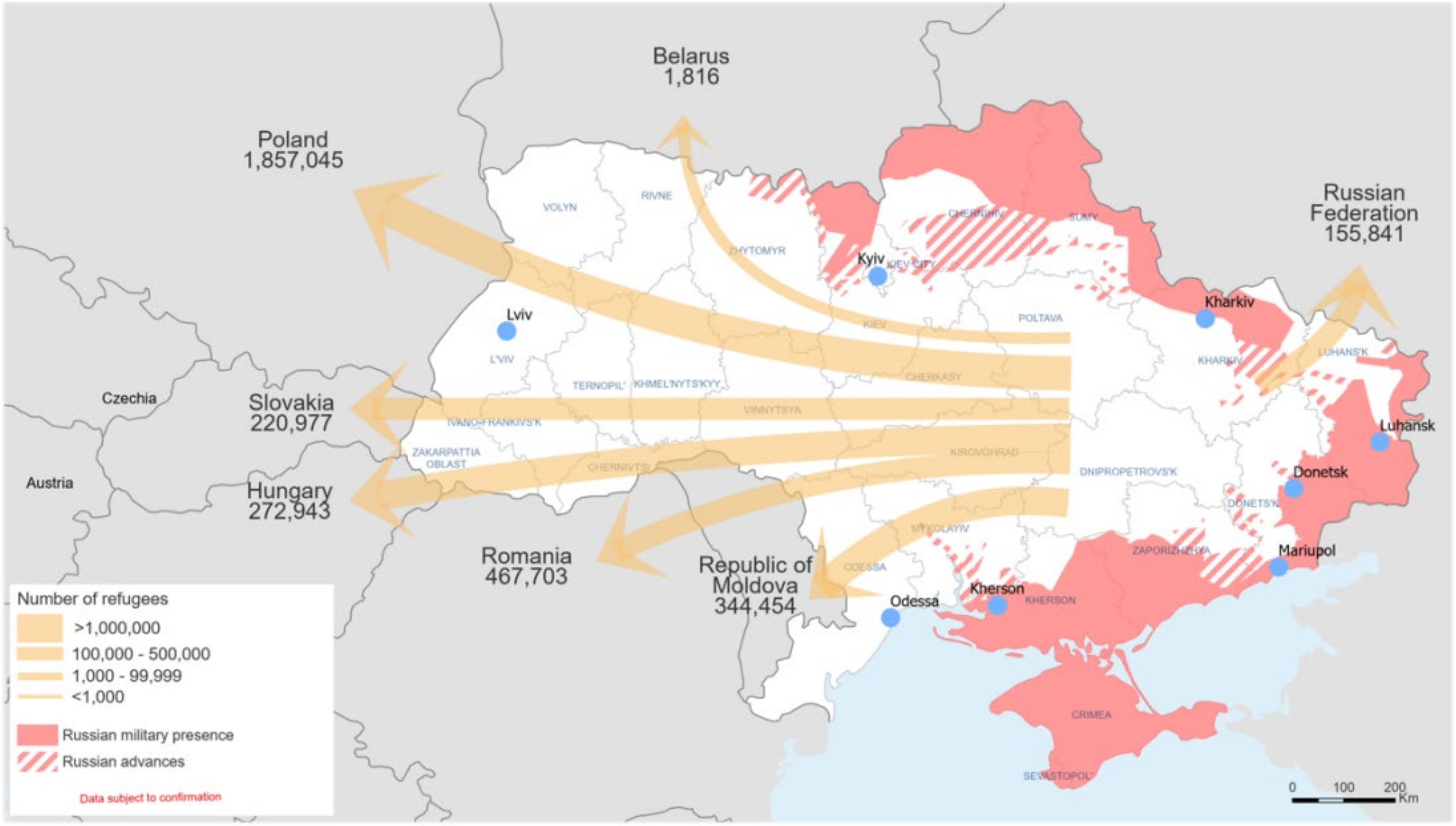

1.1. An Outline of the Escape of Refugees after the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

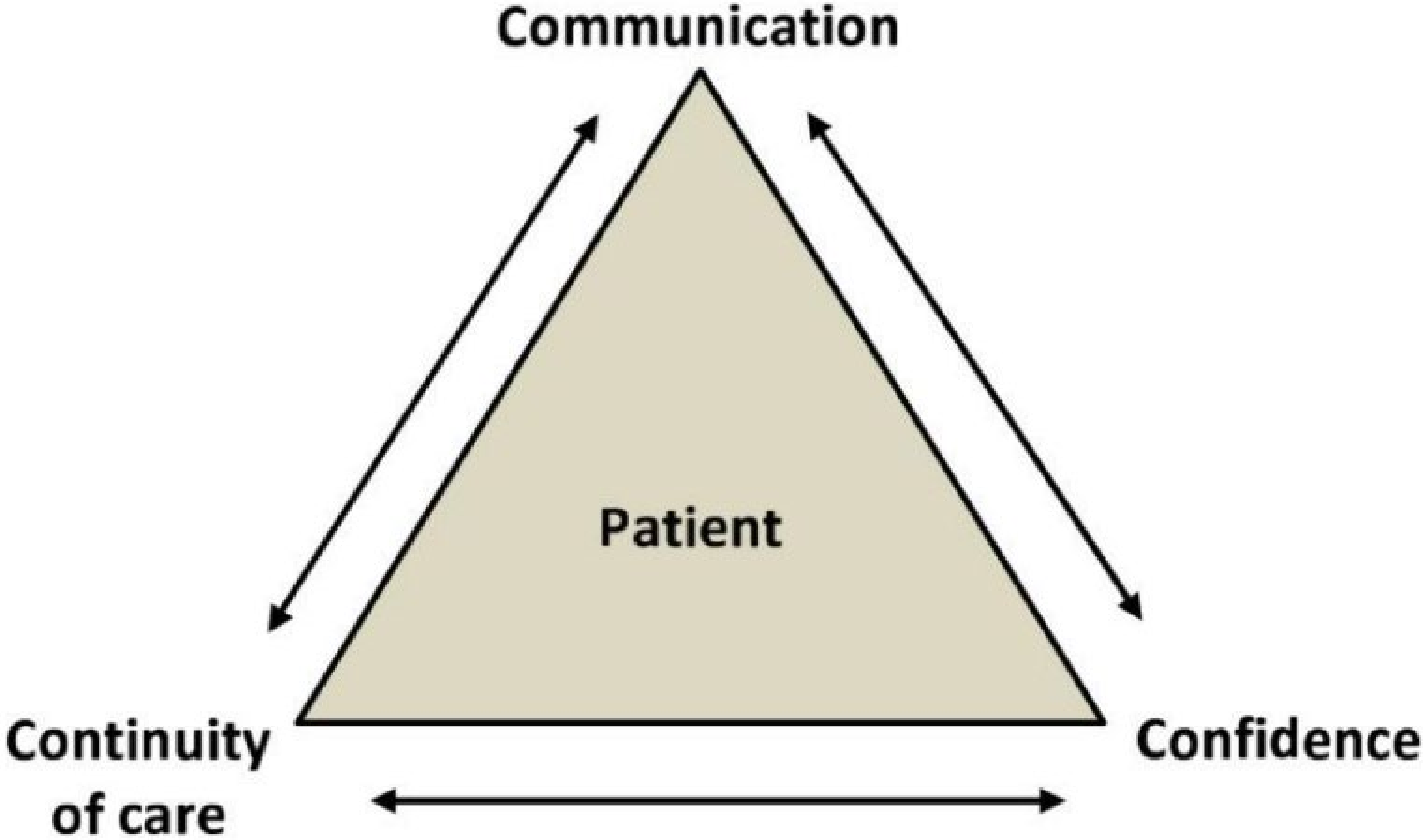

1.2. General Information on the Role of Communication in Medicine

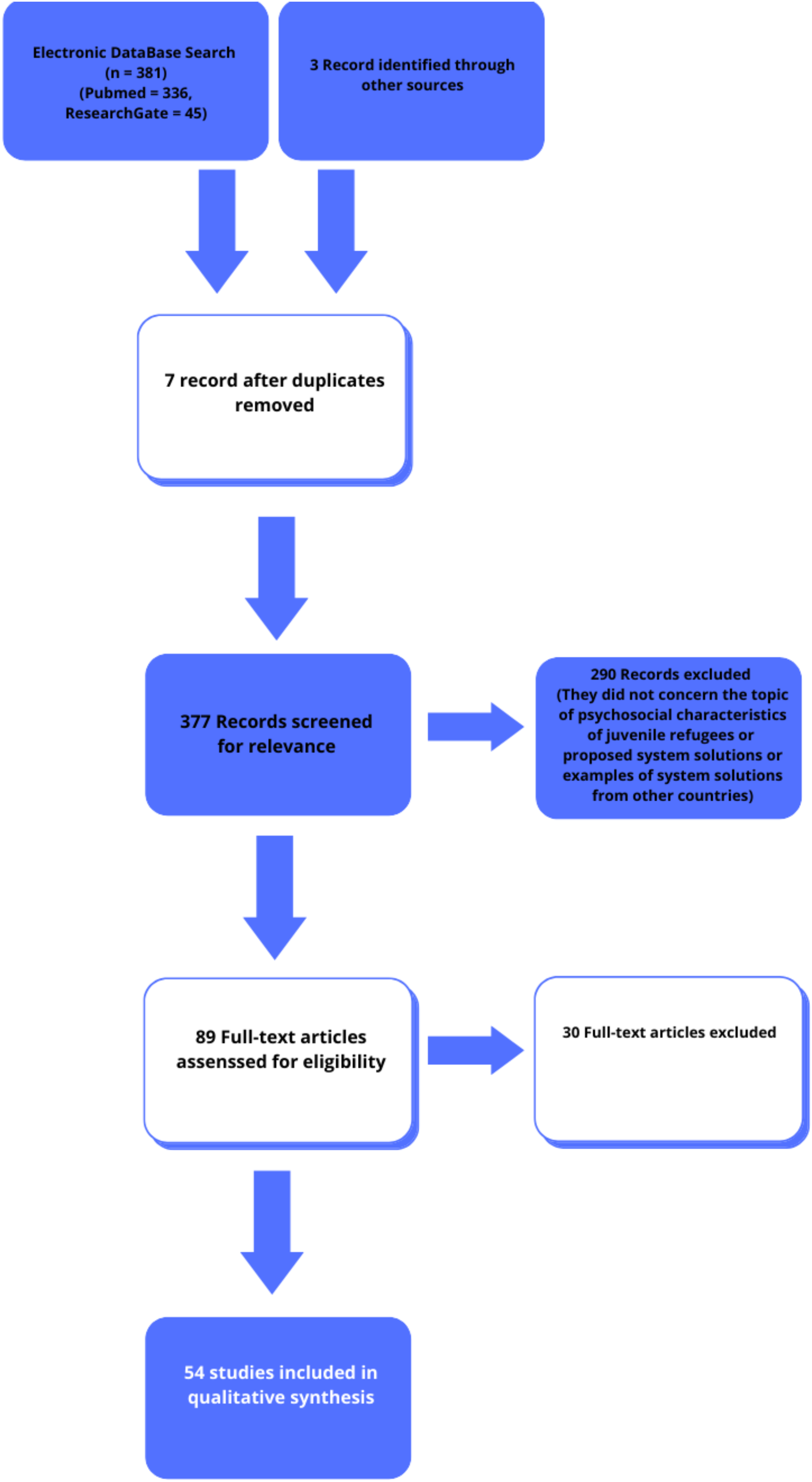

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Health and Psychosocial Situation of the Refugee Minor

3.2. Experiences from Recent Refugee Crises

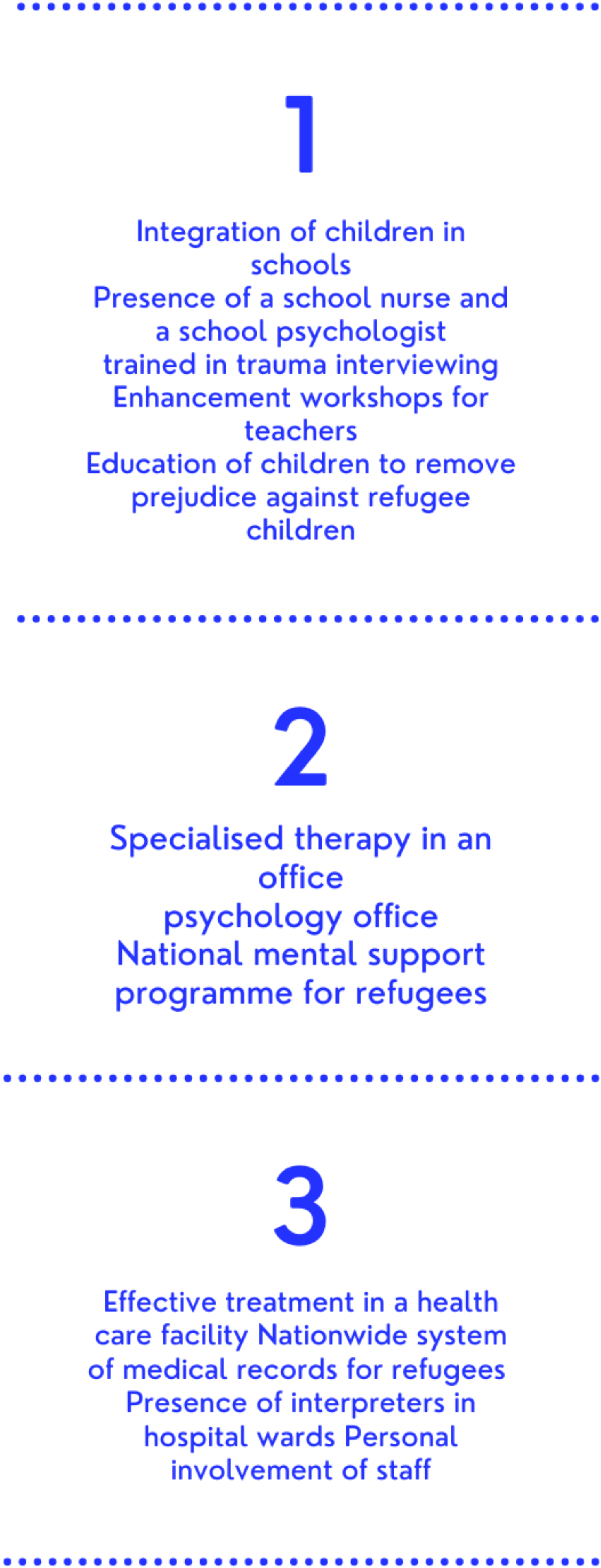

3.3. Systemic Solutions for Refugee Care

Adapting the Health Care System

3.4. Medical Innovations in Working with Refugees

3.5. Integration of School-Age Children

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haukkala, H. From Cooperative to Contested Europe? The Conflict in Ukraine as a Culmination of a Long-Term Crisis in EU–Russia Relations. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 2015, 23, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevel, O. Migration, Refugee Policy, and State Building in Postcommunist Europe; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 134–194. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization—Regional Office for Europe. Ukraine Crisis Public Health Situation Analysis—Refugee-Hosting Countries 17 March 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2022. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/352494/WHO-EURO-2022-5169-44932-63918-eng.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Additional UNICEF Supplies on Their Way to Ukraine as Number of Child Refugees Exceeds 1 Million Mark. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/additional-unicef-supplies-their-way-ukraine-number-child-refugees-exceeds-1-million (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Stewart, M.A. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1995, 152, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Mohaammadnezhad, M.; Ward, P. Trust and Communication in a Doctor-Patient Relationship: A Literature Review. J. Healthc. Commun. 2018, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.; Moscrop, A.; Mebius, A.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Lewith, G.; Bishop, F.L.; Mistiaen, P.; Roberts, N.W.; Dieninytė, E.; Hu, X.-Y.; et al. Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. R. Soc. Med. 2018, 111, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeir, P.; Vandijck, D.; Degroote, S.; Peleman, R.; Verhaeghe, R.; Mortier, E.; Hallaert, G.; Van Daele, S.; Buylaert, W.; Vogelaers, D. Communication in healthcare: A narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 69, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Lewton, E.; Rosenthal, M.M. Communication Failures: An Insidious Contributor to Medical Mishaps. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.J.; Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A.; Roiland, R.A.; Polnaszek, B.E.; Bowers, B.; Kind, A. The Consequences of Poor Communication During Transitions from Hospital to Skilled Nursing Facility: A Qualitative Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, R.; Norris, T.; Parry, D. Pinpointing What is Wrong with Cross-Agency Collaboration in Disaster Healthcare. J. Int. Soc. Telemed. eHealth 2018, 6, e3. Available online: https://ojstest.ukzn.ac.za/index.php/JISfTeH/article/view/354 (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Rizkalla, N.; Mallat, N.K.; Arafa, R.; Adi, S.; Soudi, L.; Segal, S.P. “Children Are Not Children Anymore; They Are a Lost Generation”: Adverse Physical and Mental Health Consequences on Syrian Refugee Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Sanz, A.; Leiva-Gea, I.; Martin-Alvarez, L.; del Torso, S.; van Esso, D.; Hadjipanayis, A.; Kadir, A.; Ruiz-Canela, J.; Perez-Gonzalez, O.; Grossman, Z. Migrant children’s health problems, care needs, and inequalities: European primary care paediatricians’ perspective. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 44, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbl, R.; Grois, N.; Popow, C.; Somekh, E.; Ehrich, J. Pediatric Healthcare for Refugee Minors in Europe: Steps for Better Insight and Appropriate Treatment. J. Pediatr. 2018, 197, 323–324.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucas, M.; Loucas, R.; Muensterer, O.J.; Hampel, A.; Solbach, P.; Cornberg, M.; Schmidt, E.R.; Behrens, G.M.; Jablonka, A.; Wu, V.K.; et al. Surgical Health Needs of Minor Refugees in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 28, 060–066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritschi, N.; Schmidt, A.J.; Hammer, J.; Ritz, N.; Swiss Pediatric Surveillance Unit. Pediatric Tuberculosis Disease during Years of High Refugee Arrivals: A 6-Year National Prospective Surveillance Study. Respiration 2021, 100, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, H.; Akcaboy, M.; Oztek-Celebi, F.Z.; Polat, E.; Sari, E.; Acoglu, E.A.; Oguz, M.M.; Kesici, S.; Senel, S. Analysis of Refugee Children Hospitalized in a Tertiary Pediatric Hospital. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 23, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampouras, A.; Tzikos, G.; Partsanakis, E.; Roukas, K.; Tsiamitros, S.; Deligeorgakis, D.; Chorafa, E.; Schoina, M.; Iosifidis, E. Child Morbidity and Disease Burden in Refugee Camps in Mainland Greece. Children 2019, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, A.; Battersby, A.; Spencer, N.; Hjern, A. Children on the move in Europe: A narrative review of the evidence on the health risks, health needs and health policy for asylum seeking, refugee and undocumented children. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2019, 3, bmjpo-2018-000364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroening, A.L.; Dawson-Hahn, E. Health Considerations for Immigrant and Refugee Children. Adv. Pediatr. 2019, 66, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.; O’Donovan, K.; Bear, N.; Robertson, A.; Mutch, R.; Cherian, S. Nutritional assessment of resettled paediatric refugees in Western Australia. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 55, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkensee, C.; Andrew, R. Health needs of accompanied refugee and asylum-seeking children in a UK specialist clinic. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2396–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.S. Toxic stress and child refugees. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 23, e12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloning, T.; Nowotny, T.; Alberer, M.; Hoelscher, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Froeschl, G. Morbidity profile and sociodemographic characteristics of unaccompanied refugee minors seen by paediatric practices between October 2014 and February 2016 in Bavaria, Germany. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yayan, E.H.; Düken, M.E.; Özdemir, A.A.; Çelebioğlu, A. Mental Health Problems of Syrian Refugee Children: Post-Traumatic Stress, Depression and Anxiety. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 51, e27–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendavid, E.; Boerma, T.; Akseer, N.; Langer, A.; Malembaka, E.B.; Okiro, A.E.; Wise, P.H.; Heft-Neal, S.; Black, R.E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; et al. The effects of armed conflict on the health of women and children. Lancet 2021, 397, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgin, D.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Doyle, M.; Eliez, S.; Fegert, J.M.; Fuentes, J.; Hebebrand, J.; Hillegers, M.; Karwautz, A.; Kiss, E.; et al. Impact of war and forced displacement on children’s mental health—Multilevel, needs-oriented, and trauma-informed approaches. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.Z.; Shilpi, A.B.; Sultana, R.; Sarker, S.; Razia, S.; Roy, B.; Arif, A.; Ahmed, M.U.; Saha, S.C.; McConachie, H. Displaced Rohingya children at high risk for mental health problems: Findings from refugee camps within Bangladesh. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 45, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J.; Leung, J.K.; Harris, K.; Abdullah, A.; Rohbar, A.; Brown, C.; Rosenthal, M.S. Recently-Arrived Afghan Refugee Parents’ Perspectives about Parenting, Education and Pediatric Medical and Mental Health Care Services. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 24, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Yameen, T.A.; Abadeh, A.; Lichter, M. Visual impairment and unmet eye care needs among a Syrian pediatric refugee population in a Canadian city. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 54, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, P.J.; Lanfranco, P.J.; Sneath, E.; Wade, A.J.; Huffam, S.; Pollard, J.; Standish, J.; McCloskey, K.; Athan, E.; O’Brien, D.P.; et al. Health issues of refugees attending an infectious disease refugee health clinic in a regional Australian hospital. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 47, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.E.; Al Azdi, Z.; Islam, K.; Kabir, A.E.; Huque, R. Prevalence of Eye Problems among Young Infants of Rohingya Refugee Camps: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, E. The Importance of Oral Health in Immigrant and Refugee Children. Children 2019, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, N.; Konrad, K.; Brack, C.; Hahn, E.; Herbst, A.; Icks, A.; Grulich-Henn, J.; Jorch, N.; Kastendieck, C.; Mönkemöller, K.; et al. Diabetes care in pediatric refugees from Africa or Middle East: Experiences from Germany and Austria based on real-world data from the DPV registry. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, N.R.; MacPherson, A.; Guan, J.; Guttmann, A. Unintentional injuries among refugee and immigrant children and youth in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cross-sectional study. Inj. Prev. 2017, 24, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buser, S.; Brandenberger, J.; Gmünder, M.; Pohl, C.; Ritz, N. Asylum-Seeking Children with Medical Complexity and Rare Diseases in a Tertiary Hospital in Switzerland. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 23, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, A.P.; Rehmus, W.; Chang, A.Y. Skin diseases in displaced populations: A review of contributing factors, challenges, and approaches to care. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, R.; Shemesh, Y.; Nitzan, O.; Azrad, M.; Peretz, A. Tinea capitis in an immigrant pediatric community; a clinical signs-based treatment approach. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- User, I.R.; Ozokutan, B.H. Common pediatric surgical diseases of refugee children: Health around warzone. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2019, 35, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baauw, A.; Rosiek, S.; Slattery, B.; Chinapaw, M.; van Hensbroek, M.B.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Holthe, J.K.-V. Pediatrician-experienced barriers in the medical care for refugee children in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, R.M.; Schumacher, D.J.; Cicek-Okay, S.; Jernigan, S.; Beydoun, A.; Salem, T.; Vaughn, L.M. Beliefs, perceptions, and behaviors impacting healthcare utilization of Syrian refugee children. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joury, E.; Meer, R.; Chedid, J.C.A.; Shibly, O. Burden of oral diseases and impact of protracted displacement: A cross-sectional study on Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, S.; Pike, I.; Oneissi, A.; Zheng, A.; Abu-Sittah, G. Pediatric Burns among Refugee Communities in Lebanon: Evidence to Inform Policies and Programs. J. Burn Care Res. 2019, 40, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.; Rashed, M.; Azzo, M.; Tabbakh, A.; El Sedawi, O.; Hussein, H.B.; Khalil, A.; Bulbul, Z.; Bitar, F.; El Rassi, I.; et al. Congenital Heart Disease in Syrian Refugee Children: The Experience at a Tertiary Care Center in a Developing Country. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2021, 42, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.H.; Razeq, N.M.A.; AbdulHaq, B.; Arabiat, D.; Khalil, A.A. Displaced Syrian children’s reported physical and mental wellbeing. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2017, 22, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, M.; Power, L.; Petrova, M.; Gunn, S.; Powell, R.; Coghlan, R.; Grant, L.; Sutton, B.; Khan, F. Illness-related suffering and need for palliative care in Rohingya refugees and caregivers in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heenan, R.C.; Volkman, T.; Stokes, S.; Tosif, S.; Graham, H.R.; Smith, A.; Tran, D.; Paxton, G. ‘I think we’ve had a health screen’: New offshore screening, new refugee health guidelines, new Syrian and Iraqi cohorts: Recommendations, reality, results and Review. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 55, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanes, G.; Chee, J.; Mutch, R.; Cherian, S. Paediatric asylum seekers in Western Australia: Identification of adversity and complex needs through comprehensive refugee health assessment. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2019, 55, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, K.; Tiittala, P.; Keskimäki, I.; Helve, O. Refugee crisis in Finland: Challenges to safeguarding the right to health for asylum seekers. Health Policy 2019, 123, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.R.; Guan, J.; MacPherson, A.; Lu, H.; Guttmann, A. Association of Immigrant and Refugee Status with Risk Factors for Exposure to Violent Assault Among Youths and Young Adults in Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serre-Delcor, N.; Treviño-Maruri, B.; Collazos-Sanchez, F.; Pou-Ciruelo, D.; Soriano-Arandes, A.; Sulleiro, E.; Molina-Romero, I.; Ascaso, C.; Bocanegra-Garcia, C. Health Status of Asylum Seekers, Spain. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.K.; Jaffe, J.; Mutch, R. Overcoming Communication Barriers in Refugee Health Care. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 66, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberger, J.; Tylleskär, T.; Sontag, K.; Peterhans, B.; Ritz, N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries—The 3C model. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.A. Rising up to the challenge: Strategies to improve Health care delivery for resettled Syrian refugees in Canada. Univ. Tor. Med. J. 2016, 94, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schrier, L.; Wyder, C.; del Torso, S.; Stiris, T.; von Both, U.; Brandenberger, J.; Ritz, N. Medical care for migrant children in Europe: A practical recommendation for first and follow-up appointments. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, 178, 1449–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worabo, H.J.; Hsueh, K.-H.; Yakimo, R.; Worabo, E.; Burgess, P.A.; Farberman, S.M. Understanding Refugees’ Perceptions of Health Care in the United States. JNP J. Nurse Pract. 2016, 12, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Garcia, J.; Stein, A. The right location? Experiences of refugee adolescents seen by school-based mental health services. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylen, S.; Cherian, S.; Gill, F.; Leslie, G.D.; Wilson, S. Impact of professional interpreters on outcomes for hospitalized children from migrant and refugee families with limited English proficiency: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 1360–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodes, M.; Vostanis, P. Practitioner Review: Mental health problems of refugee children and adolescents and their management. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 60, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormez, V.; Kılıç, H.N.; Orengul, A.C.; Demir, M.N.; Mert, E.B.; Makhlouta, B.; Kınık, K.; Semerci, B. Evaluation of a school-based, teacher-delivered psychological intervention group program for trauma-affected syrian refugee children in Istanbul, Turkey. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.E.; Weinberger, S.J.; Harder, V.S. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a Mental Health Screening Tool for Newly Arrived Pediatric Refugees. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 23, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, D.H.; Rizzo, S.; Biegler, K.; Sim, S.E.; Nicholas, E.; Chandler, M.; Ngo-Metzger, Q.; Paigne, K.; Nguyen, D.V.; Mollica, R. Novel Health Information Technology to Aid Provider Recognition and Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Primary Care. Med. Care 2019, 57, S190–S196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streuli, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Mohamed, A.; Sharma, M.; Esmailian, M.; Sezan, I.; Farrell, C.; Sawyer, M.; Meyer, D.; El-Maleh, K.; et al. Development of a culturally and linguistically sensitive virtual reality educational platform to improve vaccine acceptance within a refugee population: The SHIFA community engagement-public health innovation programme. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minhas, M.F.F.R.S.; Graham, H.R.; Jegathesan, H.M.T.; Huber, M.P.M.F.J.; Young, F.E.; Barozzino, F.T. Supporting the developmental health of refugee children and youth. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 22, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musliu, E.; Vasic, S.; Clausson, E.K.; Garmy, P. School Nurses’ Experiences Working with Unaccompanied Refugee Children and Adolescents: A Qualitative Study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5, 2377960819843713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsli-Calamak, E.; Kilinc, S. Becoming the teacher of a refugee child: Teachers’ evolving experiences in Turkey. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 25, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO EpiBrief—A Report on the Epidemiology of Selected Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the European Region. 2018. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/370656/epibrief-1-2018-eng.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- WHO EpiData—A Monthly Summary of the Epidemiological Data on Selected Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the WHO European Region. 2019. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/394060/2019_01_Epi_Data_EN_Jan-Dec2018.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Roberts, L. Surge of HIV, tuberculosis and COVID feared amid war in Ukraine. Nature 2022, 603, 557–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Operational Public Health Considerations for the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in the Context of Russia’s Aggression towards Ukraine; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koller, S.H.; Verma, S. Commentary on cross-cultural perspectives on positive youth development with implications for intervention research. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors, Publication Year | Number of Respondents/Group of Respondents | What Was Assessed/Country of Origin | Evaluation Methods | Main Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrasco-Sanz A, Leiva-Gea I, Martin-Alvarez L, Del Torso S, van Esso D, Hadjipanayis A, Kadir A, Ruiz-Canela J, Perez-Gonzalez O, Grossman Z, 2018 [14] | n = 492, survey among European pediatricians | Evaluation of health care for migrant children. Survey coverage: member countries of the European Pediatric Research Network | Online survey | The overall health status of migrant children is worse than non-migrant children, with chronic diseases being the most common health problem. Cultural/language factors were reported as the most common barrier (90%) to accessing health care. |

| Kerbl R, Grois N, Popow C, Somekh E, Ehrich J., 2018 [15] | - | Evaluation of paediatric health care for refugee minors in Europe | Systematic review | An increased prevalence of infectious diseases in refugees and a significantly higher prevalence of mental disorders in refugees compared to residents have been described. |

| Loucas M, Loucas R, Muensterer OJ., 2018 [16] | n = 461, study of children aged 0.5–18 years | Surgical health needs of refugee minors/Syria, Afghanistan, Kosovo, Albania, Somalia, Eritrea, Serbia | Questionnaire | Previous surgical interventions were registered in 42.2% of participants. Among girls, genital mutilation was suffered by 11%. The most common mechanism of injury was a fall from a bicycle (38%), followed by burns (7.4%). As many as 20% of the children experienced physical violence during the flight or at their accommodation. Of the participants, only 63% were vaccinated as scheduled. |

| Fritschi N, Schmidt AJ, Hammer J, Ritz N, 2021 [17] | n = 139, survey of children aged 0–15 years | Assessment of childhood tuberculosis incidence and detailed diagnostic and treatment pathways/Eritrea, Somalia, Afghanistan, Brazil, Sudan | Assessment of childhood tuberculosis incidence and detailed diagnostic and treatment pathways/Eritrea, Somalia, Afghanistan, Brazil, Sudan | Among the 64 (46.0%) children born abroad, the incidence rates were higher. They reached a peak in 2016. The incidence rate was 13.7 per 100,000. The median interval between arrival in Switzerland and diagnosis of TB was 5 months, and 80% were diagnosed within 24 months of arrival. In 58% of cases, TB was confirmed by culture or molecular testing. Age >10 years, presence of fever or weight loss were independent factors associated with confirmed TB. |

| Yucel H, Akcaboy M, Oztek-Celebi FZ, Polat E, Sari E, Acoglu EA, Oguz MM, Kesici S, Senel, 2021 [18] | n = 728 survey of children aged 1 month to 18 years | The study aimed to analyse demographic data, clinical outcomes, treatment/management data and mortality data of hospitalised refugee children/Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan | Retrospective evaluation based on electronic medical records | Refugees hospitalised in the paediatric intensive care unit were significantly younger (median age 3.7 years).The most common cause of hospital admission was infection (51.09% of patients), often accompanied by other diseases. Mortality in the general paediatrics department was 16.4% for refugee patients and 8.6% for non-refugee patients. Factors associated with mortality were younger age and being a refugee. |

| Kampouras A, Tzikos G, Partsanakis E, Roukas K, Tsiamitros S, Deligeorgakis D, Chorafa E, Schoina M, Iosifidis E., 2019 [19] | n = 220, study of children <18 years | Assessment of morbidity and overall disease burden of refugee children/Afghanistan, Syria | Register of patients seeking medical advice | The majority of visits by children under 12 years of age were for infectious diseases (80.8%). The most common sites of infectious diseases among children were the respiratory tract (66.8%). Non-communicable diseases were mostly due to gastrointestinal disorders. Infants, toddlers and children were more likely to suffer from respiratory tract infections, while adolescents and adults were more likely to have non-communicable diseases. |

| Kadir A, Battersby A, Spencer N, Hjern A., 2019 [20] | - | The majority of visits by children under 12 years of age were for infectious diseases (80.8%). The most common sites of infectious diseases among children were the respiratory tract (66.8%). Non-communicable diseases were mostly due to gastrointestinal disorders. Infants, toddlers and children were more likely to suffer from respiratory tract infections, while adolescents and adults were more likely to have non-communicable diseases. | Systematic review | Low vaccination rates against hepatitis B, chickenpox, measles, mumps, rubella and low immunity against tetanus and diphtheria have been demonstrated. Additionally, many newborns born on the move may not have access to the screening for birth defects that is widely offered in European countries (mainly refugees from Afghanistan, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey) |

| Kroening ALH, Dawson-Hahn E., 2019 [21] | - | Review article on health considerations of migrant and refugee children | Systematic review | Immigrant and refugee children are at increased risk of physical, emotional and behavioural health problems. Health issues affecting immigrant and refugee children should be framed within an ecological context that includes considerations of family, community and sociocultural influences. It is important to understand the migrant child’s migration history (or their family history), which or their family history), which provides a context for screening for infectious diseases and exposure risk (including trauma). |

| Newman K, O’Donovan K, Bear N, Robertson A, Mutch R, Cherian S., 2019 [22] | n = 1131, study of children aged 2 months to 17.8 years | Assessment of nutritional status and growth of paediatric refugees/Burma, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran | Standardised dietary, medical and socio-demographic assessments of new refugee patients using a multidisciplinary paediatric refugee health service were analysed | Nutritional deficiencies were common, but varied by ethnic group: iron deficiency (12.3%), anaemia (7.3%) and inadequate dairy intake (41.0%). One third of the children did not consume meat. In infants under 12 months of age, breastfeeding was sustained (77.8%). |

| Harkensee C, Andrew R., 2021 [23] | n = 80 survey of children <18 years of age | Identify health needs and barriers to accessing health care/ Syria, Iraq, Nigeria, Albania, El Salvador, Libya, Somalia, Afghanistan, Namibia, Sudan | Mixed methods study (retrospective analysis of routinely collected service data, qualitative data from focus groups) of children attending a hospital-based specialist outpatient clinic | The most common diagnoses given are: anaemia, neurodevelopmental disorders, respiratory diseases. Mild to moderate stunting (23%), overweight and obesity (41%), stunting with obesity (9%) and micronutrient deficiencies (vitamin D (66%), vitamin A (40%) and visible (14%) or latent (25%) iron deficiency anaemia). 62% of children experienced psychological trauma and 39% had abnormal psychosocial wellbeing screening results. 21% of children required Level II or III care, 8% mental health referrals and 47% were observed at this specialist clinic. Unresolved health needs and significant barriers to accessing healthcare were reported. |

| Murray JS., 2018 [24] | - | The aim of this article was to describe the phenomenon of toxic stress and its impact on the physical and mental health of refugee children in Syria | Systematic review | It has been established that the prolonged brutal and traumatising war in Syria is having a profound impact on the physical and mental health of refugee children at an alarming rate. Preventing toxic stress should be a primary goal of all paediatric health professionals working with refugee children. |

| Kloning T, Nowotny T, Alberer M, Hoelscher M, Hoffmann A, Froeschl G., 2018 [25] | n = 154 survey of children aged 10–18 | Investigate the morbidity profile and socio-demographic characteristics of unaccompanied refugee minors/Mainly Somalia, Eritrea, Afghanistan and Syria | Retrospective cross-sectional study including data from medical registries | Only 12.3% of all participants had no clinical symptoms on arrival. The main health symptoms were skin diseases and psychiatric disorders. Hepatitis A immunity was 92.8%, but only 34.5% showed a constellation of hepatitis B immunity. Suspected cases of tuberculosis were found in 5.8%. There were no HIV-infected individuals in the cohort. Two women were found to have undergone genital mutilation. |

| Yayan EH, Düken ME, Özdemir AA, Çelebioğlu A., 2020 [26] | n = 1115 survey of children aged 9–15 | Investigating levels of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety in children living in refugee camps/Syria | Research data were collected using the Posttraumatic Stress Response Index, the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children and the Children’s Depression Inventory | The results of the study showed that refugee children have physical and psychosocial health problems and experience high levels of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety. Most of the participating children (74%) were smokers. Anxiety and depression were statistically significantly related to post-traumatic stress. |

| Bendavid E, Boerma T, Akseer N, Langer A, Malembaka EB, Okiro EA, Wise PH, Heft-Neal S, Black RE, Bhutta ZA., 2021 [27] | - | Article on the impact of armed conflict on the health of women and children | Systematic review | The average prevalence of anxiety disorders and major depression in conflict-affected populations is estimated to be two to four times higher than the estimated global prevalence. Adolescent refugees affected by armed conflict are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, sexual violence and the breakdown of family structures. |

| Bürgin D., 2022 [28] | - | Article on the impact of war and forced displacement on children’s mental health | Systematic review | The experiences that children have to endure during and as a result of war are in sharp contrast to their developmental needs and right to grow up in a physically and emotionally safe and predictable environment. Mental health and psychosocial interventions for children affected by war should be multi-level, child-centred, trauma-informed and strength and resilience oriented. |

| Khan NZ, Shilpi AB, Sultana R, Sarker S, Razia S, Roy B, Arif A, Ahmed MU, Saha SC, McConachie H., 2019 [29] | n = 622 survey of children <16 years of age | Investigating the level of neurodevelopmental and mental disorders in refugee children/Mjanma | Developmental Screening Questionnaire (DSQ; <2 years ) i Ten Questions Plus (TQP) andoraz Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; 2–16 years ). | The number and percentage of children with positive screening results was 6 (4.8%) in children up to 2 years and 36 (7.3%) in children aged 2 to 16 years. 52% of the children were in the abnormal range for emotional symptoms in the SDQ and 25% for problems with peers. Lack of parents and loss of one or more family members in a recent crisis appeared to be significant risk factors. |

| Rosenberg J, Leung JK, Harris K, Abdullah A, Rohbar A, Brown C, Rosenthal MS., 2022 [30] | n = 19 parents | Characterise the experience of parenting, education and health care services/Afghanistan, Pakistan | Interview | The data shows that parents were relieved upon arrival in the US of their previous concerns about safety risks to their children. Many expressed a sense of isolation when they first arrived in the States. Some described a growing local support system. Parents perceived that it was difficult for their children to maintain religious rituals and described difficulties in maintaining traditions. All parents reported that, prior to coming to the US, their families only received health care in emergencies, which differed from the prevention system present in the US. |

| Bin Yameen TA, Abadeh A, Lichter M., 2019 [31] | n = 274 Survey of children <18 years of age | Assessment of eye care and visual impairment among refugee minors/Syria | Surveys, eye screening, eye examinations | The prevalence of uncorrected vision was 17.2 per cent for distance, 4.7 per cent for near and 0.7 per cent for distance and near vision, including loss of vision. Of these, 95.3% had not visited an ophthalmologist in the past year and 25.2% of parents were dissatisfied with their children’s vision. Presenting visual acuity in the better-sighted eye was 20/50 or less in 5.8%. This rate is 32 times higher than the prevalence rate in the average Canadian paediatric population (0.17%). |

| Masters PJ, Lanfranco PJ, Sneath E, Wade AJ, Huffam S, Pollard J, Standish J, McCloskey K, Athan E, O’Brien DP, Friedman ND., 2018 [32] | n = 291 refugees ≥16 years old—165 <16 years old—126 | Review of reasons for referral, prevalence of conditions and outcomes for refugee patients/Mainly Burma, Sudan, Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo | A retrospective review of patients attending the refugee health clinic at Geelong University Hospital | The most common diagnoses were latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) (54.6%), vitamin deficiencies (15.8%), hepatitis B (11%) and schistosomiasis (11%). Less than two-thirds of patients completed LTBI treatment; 35.4% of patients attended all scheduled clinic visits. |

| Hussain AE, Al Azdi Z, Islam K, Kabir AE, Huque R., 2020 [33] | n = 670 neonatal and infant study 0–59 days old | Prevalence of eye problems among infants residing in refugee camps/Mjanma | Screening form, consent form and vision problems questionnaire | The most common problem among infants was tearing of the eye (14.8%). Visual inattention was identified as the second most common problem in infants reported by mothers (5.1%).Eye redness was observed in 4%. No eye problem was related to the gender of the infants. |

| Crespo E., 2019 [34] | - | Article on the importance of oral health in immigrant and refugee children | Systematic review | Poor oral hygiene and resulting tooth decay is also a serious problem among refugee and migrant children. |

| Prinz N, Konrad K, Brack C, Hahn E, Herbst A, Icks A, Grulich-Henn J, Jorch N, Kastendieck C, Mönkemöller K, Razum O, Steigleder-Schweiger C, Witsch M, Holl RW., 2019 [35] | n = 43,137 patients <21 years old n = 365—refugees born in the Middle East n = 175—refugees born in Africa n = 42,597—native-born patients in Germany/Austria | Diabetes care for paediatric refugees/Morocco, Egypt, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Syria, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Germany, Austria | Data were collected during routine care and taken from the standardised diabetes patient follow-up (DPV; “Diabetes-Patienten-Verlaufsdokumentation”—database for people with diabetes) | HbA1c and microalbuminuria were highest among refugees. African children were significantly more likely to experience severe hypoglycaemia. Hypoglycaemia with coma and rethionopathy were significantly more frequent in Middle Eastern children compared to the native population. Insulin pumps were used in a significantly higher proportion of native patients. |

| Saunders NR, Macpherson A, Guan J, Guttmann A., 2018 [36] | n = 999,951—total number of immigrants 153,822—refugees 846,129—non-refugees 0–24 years | Unintentional injuries among immigrant and refugee children/ The majority of immigrants were from South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific. The largest proportion of refugees came from South Asia and Africa | Cross-sectional population-based survey using linked health, administrative and immigration data | There were 6596.0 and 8122.3 emergency department visits per 100,000 non-refugee and refugee migrants, respectively. Hospitalisation rates were 144.9 and 185.2 per 100,000 in each of these groups. Unintentional injury rates among refugees were 20% higher than among non-refugees. j. Young age, male gender and high income were associated with injury risk. Compared to non-refugees, refugees had a higher rate of injury from most causes. |

| Buser S, Brandenberger J, Gmünder M, Pohl C, Ritz N., 2021 [37] | n = 19 children aged 0–16.7 | Assessment of characteristics of asylum-seeking children with medical complexity detailing their underlying medical conditions and management/ Syria, Eritrea, Afghanistan, Somalia, Algeria, Russia | A retrospective cross-sectional study. Patients were identified by administrative electronic records | A total of 34/811(4%) visits were hospital admissions, 66/811 (8%) emergency department visits and 320/811 (39%) outpatient department visits. In children <2 years, genetic diseases and nutritional problems were the most common; in adolescents, orthopaedic diseases and mental health problems. Children with medical complexity seeking asylum represent a small but important group of patients requiring frequent medical consultations. |

| Knapp AP, Rehmus W, Chang AY., 2020 [38] | - | Review article on skin diseases in displaced populations | Systematic review | There may also be few or largely limited access to dermatologists in the host country, due to the distance of specialists from the refugee camp and thus the cost of transport, making it difficult to treat displaced persons effectively. |

| Kassem R, Shemesh Y, Nitzan O, Azrad M, Peretz A., 2021 [39] | n = 76 children aged 0–8 years | Determination of clinical features and response to treatment of tinea capitis among refugee children/Eritrea | Analysis of electronic medical recordsj | The most common clinical sign was peeling skin. Cultures were positive in 64 (84%) and direct examination in 65 (85%) cases, with a positive correlation between methods in 75% of cases. The most common fungal strain was T. violaceum. Treatment with fluconazole failed in 27% of cases. Griseofulvin 50 mg/kg/day was administered to 74 (97%) children and induced a clinical response. No side effects were reported. |

| User IR, Ozokutan BH., 2019 [40] | n = 254 survey of children aged 0–16 | Assessing the sociodemographic and medical characteristics of childhood refugee patients and identifying their health problems/Syria | A retrospective cross-sectional study. Data were based on the records of patients admitted to the paediatric surgery department of a teaching hospital | The most common diagnosis was inguinal urothelial pathology (n = 50, 19.7%), followed by foreign body ingestion (n = 37, 14.6%) and caustic oesophagitis (n = 22, 8.7%). In 24.4% of cases, the cause of admission was preventable trauma. Comorbidities were present in 49 patients (19.3%). Anaemia was detected in 23.2% of cases. Difficulties in communication, lack of previous medical history and advanced disease symptoms were challenges faced by caregivers. |

| Baauw A, Rosiek S, Slattery B, Chinapaw M, van Hensbroek MB, van Goudoever JB, Kist-van Holthe J., 2018 [41] | n = 68—number of reported cases (barriers to health care) | Gain insight into pediatricians’ perceived barriers to health care for refugee children by analyzing logistical issues reported by pediatricians | Analysis of reports obtained through the Dutch Paediatric Surveillance Unit | Paediatricians reported 68 cases of barriers to care, ranging from mild to severe impact on the health of refugee children, reported between November 2015 and January 2017. The frequent transfer of children between refugee centres was mentioned in 28 reports of lack of continuity of care. Unknown medical history (21/68) and poor transfer of medical records resulting in poor communication between health professionals (17/68) contributed to barriers to good medical care for refugee children, as did poor health knowledge (17/68) and cultural differences (5/68). |

| Alwan RM, Schumacher DJ, Cicek-Okay S, Jernigan S, Beydoun A, Salem T, Vaughn LM., 2020 [42] | n = 18—Syrian refugee parents | Exploring refugee parents’ beliefs, perspectives and practices regarding their children’s health/Syria | Interview | The analysis identified the most salient themes: stressors excluded health-promoting behaviours, parents perceived barriers to health and showed dissatisfaction with the health care system. Stressors included poor housing and neighbourhood, reliving traumatic experiences, depression and anxiety, and social isolation. Dissatisfaction included emergency room waiting times, lack of tests and prescriptions. Health barriers included missed appointments and inadequate transport, translation services, health literacy and care coordination. Parents reported resilience through faith, seeking knowledge, using natural resources and utilising community resources. |

| Joury E, Meer R, Chedid JCA, Shibly O., 2021 [43] | n = 910, Syrian refugee children attending 5 primary schools for Syrian refugees in informal settlements in Bekaa, Lebanon | To assess the prevalence of oral diseases in the children of Syrian refugees living in Lebanon and to investigate their association with the duration of displacement | Cross-sectional study, analysis of data from a cross-sectional oral health needs assessment conducted by Global Miles for Smiles | The study highlights the importance of untreated tooth decay and pain in the refugee child population. Children with long-term resettlement had significantly more teeth with untreated caries compared to children who had been resettled for less than five years. |

| Al-Hajj S, Pike I, Oneissi A, Zheng A, Abu-Sittah G., 2019 [44] | n = 347—children of refugees settled in lebanon, age 0–19 years | Analysis of burn cases among Syrian refugee children in Lebanon | Retrospective cohort study | Data from Lebanon shows that Syrian refugee children are very often traumatised already living in refugee camps. In addition, refugees have limited access to healthcare, lacking insurance and the ability to cover medical costs. In Lebanon, there is a lack of systemic interventions to improve this situation, in contrast to numerous high-income countries, where significant funding has been allocated for prevention, burns treatment and aftercare. |

| Mostafa H, Rashed M, Azzo M, Tabbakh A, El Sedawi O, Hussein HB, Khalil A, Bulbul Z, Bitar F, El Rassi I, Arabi M., 2021 [45] | n = 439, Syrian refugees under 18 years of age, mean age 3.97 years | Describing the presentation, diagnoses, treatment, financial burden and outcomes among Syrian refugees with congenital heart disease (CHD) in Lebanon | A retrospective study, reviewing the medical records of all Syrian paediatric patients referred to the Children’s Heart Centre at the American University Medical Centre in Beirut for evaluation between 2012 and 2017 | There is an increased rate of severe CHD among refugee children due to lack of access to health care, with only children with severe symptoms being able to receive medical attention. In developing countries, fewer patients reach adulthood due to delayed diagnosis, inability to start or complete treatment. All costs associated with this screening and treatment of Syrian children with heart defects have been covered by NGOs (UNHCR, Brave Heart Fund, GOLI), and medical workers have often waived their salaries. |

| Hamdan-Mansour AM, Abdel Razeq NM, AbdulHaq B, Arabiat D, Khalil AA., 2017 [46] | n = 250 Syrian refugee children aged 6–18 years | Investigating the physical and psychosocial health of displaced Syrian refugee children in Jordan | Cross-sectional exploratory design, structured questionnaires, data collection through face-to-face interviews | Evidence suggests that Syrian refugee children have been exposed to or witnessed serious traumatic war events. Exposure to these war events has been associated with negative psychological consequences for children, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and somatic disorders. Previous research has shown that children who survived the war continue to suffer from its psychological consequences for many years after the war. Large-scale interventions are therefore needed to address the mental health and physical trauma of refugees. |

| Doherty M, Power L, Petrova M, Gunn S, Powell R, Coghlan R, Grant L, Sutton B, Khan F., 2020 [47] | n = 311 people, including 156 people living with serious health problems and 155 carers | Characteristics of illness-related suffering and palliative care needs in refugees and caregivers settled in Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh | Cross-sectional study | Attention was drawn to the widespread lack of palliative care for refugees in humanitarian assistance, which is an essential component during a humanitarian crisis. Many patients are experiencing pain and suffering due to severe injuries and illnesses, yet national regulations limit access to strong pain medication. Neither the government nor NGOs are showing action to improve this situation. The physical, mental and social needs of patients and their caregivers are not being met by humanitarian aid. They do not have access to medicines and medical care. |

| Heenan RC, Volkman T, Stokes S, Tosif S, Graham H, Smith A, Tran D, Paxton G., 2019 [48] | n = 128, Syrian and Iraqi children aged 0–17 years receiving specialist migrant health care from January 2015 to September 2017 in Australia | To explore the health assessment of refugee children settled in Australia in the context of screening, the refugee primary health care model and the guidelines introduced | Retrospective audit of medical records of refugee children receiving RCH IHS services or outreach clinics | According to the 2016 Australian Guidelines, every arriving refugee should undergo a comprehensive health assessment. A medical examination is mandatory for all refugees and asylum seekers and should be conducted within 1 month of arrival in Australia. This also includes screening for TB and Hepatitis B and booster vaccinations. Despite good access to primary health care and screening, these activities are ineffective, not in line with current guidelines and not well supported by the RHP. |

| Hanes G, Chee J, Mutch R, Cherian S., 2019 [49] | n = 110, refugee children seeking asylum (<16 years), mean age 6 years | Determining the needs of paediatric patients among asylum seekers in Western Australia, the range of health and psychosocial problems they face and the associated challenges facing the Australian health system | Audit of multidisciplinary RHS assessments, medical records and hospital admissions of new asylum seeker patients (<16 years) between July 2012 and June 2016. | Australia’s system of reception and care for refugees, to some extent, hinders their diagnosis and treatment. The process delays diagnosis and treatment (the median duration of detention was 7 months), in addition, multiple relocations do not provide the opportunity to maintain continuity of medical care. During detention, refugees do not have access to medical, psychological and educational services (this is also affected by the visa category held). It has also been shown that in community detention most children experience physical and sexual assaults and there are numerous cases of self-harm and suicide. |

| Tuomisto K, Tiittala P, Keskimäki I, Helve O., 2019 [50] | - | Analysis of problems related to health care and access to medical services among asylum seekers in Finland | Qualitative review | The work identified three main problems in the governance of the asylum seeker health system: (1) Ineffective national coordination and governance; (2) Inadequate legal and supervisory frameworks leading to ineffective governance; (3) Disparities between constitutional health rights, statutory entitlements to benefits and available medical services. |

| Saunders NR, Guan J, Macpherson A, Lu H, Guttmann A., 2020 [51] | n = 22,969,443 (20,012,091 non-immigrants and 2,957,352 immigrants; 51.3% male and 48.7% female) | Exploring the association of immigrant or refugee status with experiences of violence and assault in Ontario, Canada | Population-based cohort study, used linked health and administrative databases | A Canadian study found that refugee youth in the country experienced assault as much as 51% less frequently than Canadian youth. The low rates of experiencing assault by migrants, including refugees, indicate a high level of support for immigrant settlement in Canada and suggest the influence of cultural factors on assault risk. |

| Serre-Delcor N, Ascaso C, Soriano-Arandes A, Collazos-Sanchez F, Treviño-Maruri B, Sulleiro E, Pou-Ciruelo D, Bocanegra-Garcia C, Molina-Romero I., 2018 [52] | n = 303, Median age was 28.0 years | Description of the health status of asylum seekers in Spain | A retrospective population-based study including all asylum seekers who applied for a medical examination at the Vall d’Hebron-Drassanes Tropical Medicine and International Health Unit (Barcelona, Spain) between July 2013 and June 2016. | Unstable living situations and frequent relocation, limit access to healthcare and prevent continuity of treatment. Language and cultural barriers, also hinder effective care. In the survey conducted, about 83% of the immigrants surveyed completed the entire treatment process, while only 22% completed the hepatitis B vaccination schedule. It should be emphasised that the medical care and vaccination offered was free of charge, and that the failure of the treatment process was most likely due to the previously mentioned unfavourable factors. |

| Clarke SK, Jaffe J, Mutch R., 2019 [53] | - | What communication barriers may be encountered when working with refugees? How can these barriers be overcome and what ethical challenges may be encountered when working with interpreters? | Przegląd systematyczny | Training by professional interpreters should be available at medical universities and hospitals, as well as remote access to interpreters. Collaborating as part of an interdisciplinary team can help avoid ethical dilemmas, help reduce disparities and ultimately save time and money. |

| Brandenberger J, Tylleskär T, Sontag K, Peterhans B, Ritz N., 2019 [54] | - | A summary of current knowledge on the provision of health care to migrants and refugees in high-income countries. | A systematic review of the literature from 2000–2017. Of the 185 articles found, 35 were selected for final analysis. | The 3C model provides a simple and comprehensive patient-centred summary of the key challenges in providing healthcare to refugees and migrants. It is supportive of health professionals, but the model itself is influenced by factors such as the specific regional context with legal, financial, geographical and cultural aspects. |

| Rahman A., 2016 [55] | - | Assessing the readiness of Canada’s health care system to accommodate Syrian refugees, Canada | Systematic review | The health system must adapt to meet the health needs of refugees by providing special training and mentoring for medical students and GPs on current health policies related to refugees, providing interpreters, and fostering collaboration between government and community organisations to develop outreach programmes. |

| Schrier L, Wyder C, Del Torso S, Stiris T, von Both U, Brandenberger J, Ritz N., 2019 [56] | - | To obtain consensus on recommendations for medical care for migrant children (asylum seekers and refugees). The work of authors from research centres in 7 countries | Recommendations; Current clinical guidelines and recommendations for the management of migrant children in the EU/EEA area were collected and compared | The document can serve as a tool to ensure basic rights so that migrant children in Europe receive comprehensive, patient-centred health care, access to interpreter services and specific recommendations for the prevention or early detection of communicable and non-communicable diseases. |

| Worabo HJ, Hsueh KH, Yakimo R, Worabo E, Burgess PA, Farberman SM., 2016 [57] | n = 39, (1) clients of an urban refugee resettlement agency in the Midwest in the last 5 years; (2) 18 years of age or older; (3) from Iraq, Eritrea, Bhutan or Somalia | The aim was to better understand newly resettled refugees’ perceptions of US healthcare. The data collected is expected to reduce health disparities and improve the quality of care, as well as provide direction for future solutions.", USA | 4 in-depth interviews, analysis using the Colaizzi approach | Suggested strategies to improve the quality of health services include improving the cultural competence of health care providers, increasing access to English language classes and translation services, providing health materials translated into refugee languages, establishing stronger links between primary health care and resettlement agencies, and adopting innovative models of health care delivery. |

| Fazel M, Garcia J, Stein A., 2016 [58] | n = 40, uchodźcy w wieku nastoletnim | Access to needed mental health services can be particularly difficult for newly arrived refugee and asylum-seeking adolescents, although many are attending school, UK | This study explored young refugees’ impressions and experiences of mental health services integrated into the school system. Semi-structured interviews were conducted | Uncertainty in the asylum process has a negative impact especially on the social functioning and ability of young people to focus in school. Teachers play an important role in the support and integration process of refugee youth. |

| Boylen S, Cherian S, Gill FJ, Leslie GD, Wilson S., 2020 [59] | - | The aim of the review was to identify, critically appraise and synthesise the evidence on the impact of professional interpreters on hospital outcomes for migrant and refugee children with limited English proficiency, Australia | The aim of the review was to identify, critically appraise and synthesise the evidence on the impact of professional interpreters on hospital outcomes for migrant and refugee children with limited English proficiency, Australia | The use of ad hoc interpreters or the absence of an interpreter is inferior to the use of professional interpreters. The way in which interpreters are provided should be based on availability, accessibility, language requirements and patient preferences. |

| Hodes M, Vostanis P., 2019 [60] | - | Review integrates the latest research on risk and protective factors for psychopathology with service and treatment issues, UK | Systematic review | Many refugee children show resilience and function well, even in the face of severe adversity. The most robust findings for psychopathology are that PTSD and post-traumatic and depressive symptoms are more common in those who have been exposed to war experiences. Their severity may decrease over time with displacement, but PTSD in the most exposed may show higher continuity. |

| Gormez V, Kılıç HN, Orengul AC, Demir MN, Mert EB, Makhlouta B, Kınık K, Semerci B., 2017 [61] | 32 participants aged between 10 and 15 years (mean = 12.41, SD = 1.68), mostly female (m/f = 12/20) were randomly selected from a sample of 113 refugee students based on their trauma-related psychopathology as reflected in the total Child Post-Traumatic Stress—Reaction Index score | Evaluation of an innovative group cognitive-behavioral therapy program delivered by trained teachers to reduce emotional distress and improve psychological functioning among war-affected Syrian refugee children living in Istanbul, Turkey | The effectiveness of the intervention was assessed by comparing pre-test/post-test using the CPTS-RI, Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) | Protocol-based interventions need to be tested in controlled projects and larger samples so that a well-established intervention can be created and disseminated to provide psychosocial support to this vulnerable and traumatised population. |

| Green AE, Weinberger SJ, Harder VS, 2020 [62] | The sample included 301 patients aged 0–18 years; one infant was excluded and five 18-year-olds were retained for the final study sample of 300 patients aged 4–18 years | Study aims to conduct mental health screening of refugee children, United States | The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used as a screening tool for childhood mental health problems in primary care | The SDQ is a useful mental health screening tool in primary care for newly arrived refugee children. Doctors should screen on arrival to identify difficulties that may require intervention. |

| Sorkin DH, Rizzo S, Biegler K, Sim SE, Nicholas E, Chandler M, Ngo-Metzger Q, Paigne K, Nguyen DV, Mollica R., 2019 [63] | A randomised group of 18 primary care providers was allocated 390 Cambodian-American patients | A multi-component health information technology screening tool was developed to help providers identify and treat major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in primary care settings, Canada | Group randomised controlled trial | This innovative approach provides an opportunity to train primary care providers to diagnose and treat trauma patients, most of whom seek psychiatric care in primary care. |

| Streuli S, Ibrahim N, Mohamed A, Sharma M, Esmailian M, Sezan I, Farrell C, Sawyer M, Meyer D, El-Maleh K, Thamman R, Marchetti A, Lincoln A, Courchesne E, Sahid A, Bhavnani SP., 2021 [64] | 60 adult refugees from Somalia and seven experts who specialise in healthcare and autism research | Testing the effectiveness of an immunisation education platform using virtual reality (VR) to engage Somali refugee communities. United States | Community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods, including focus group discussions, interviews and surveys, were conducted with Somali community members and counsellors to design the educational content. A co-design approach with community input was used in a phased approach to develop the VR storyline | The CBPR approach can be used effectively to co-design an educational programme. Additionally, cultural and linguistic differences can be incorporated into an educational programme and are important factors for effective community engagement. Finally, effective use of VR requires flexibility so that it can be used among community members with different levels of health and technology awareness. |

| Minhas RS, Graham H, Jegathesan T, Huber J, Young E, Barozzino T., 2017 [65] | - | Designating the role of paediatricians and family physicians in caring for the developmental health of refugee children as a means of supporting their developmental and educational potential, Canada | - | The authors suggest using EMPOWER (Education, Migration, Parents and Family, Outlook, Words, Experience of Trauma and Resources), a mnemonic checklist they developed to assess developmental risk factors in refugee children. EMPOWER can be used in conjunction with online resources, such as Caring For Kids New to Canada, in providing evidence-based care for these children. |

| Musliu E, Vasic S, Clausson EK, Garmy P., 2019 [66] | n = 14, school nurses working with refugee children and young people | The aim of the study was to describe the experiences of school nurses in working with refugee children and adolescents | Semi-structured interviews were conducted with school nurses. | School nurses require development of tailored skills that focus on crisis, trauma and cultural awareness to meet the complex needs of working with refugee children and adolescents. |

| Karsli-Calamak E, Kilinc S., 2019 [67] | n = 5; three early childhood education teachers and two teachers of Turkish as a second language | The study aims to understand the changing experiences of teachers of Syrian refugee students in relation to inclusive education in Turkey | Field research in a public school located in a disadvantaged neighbourhood of the Turkish capital, where there were many Syrian refugee students. Three early childhood teachers and two teachers of Turkish as a second language were interviewed during the semestera | There should be critical conversations about the realities of refugee life resulting from structural obstacles. The process of constructing inclusive education requires prioritisation of all stakeholder claims and potential solutions to problems that directly affect them. There is a need for dialogue, transformative action and shared responsibility within and beyond national borders. |

| Session Numbers | Subject |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introductory activities to get to know each other and integrate into the group |

| 2–3 | Addressing strong emotions, maladaptive thinking styles, and creating alternative explanations for depressive, anxiety and stress-related experiences |

| 4–6 | Experiences of trauma and bereavement |

| 7–8 | Dealing with anxiety relapses, course summary |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klas, J.; Grzywacz, A.; Kulszo, K.; Grunwald, A.; Kluz, N.; Makaryczew, M.; Samardakiewicz, M. Challenges in the Medical and Psychosocial Care of the Paediatric Refugee—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710656

Klas J, Grzywacz A, Kulszo K, Grunwald A, Kluz N, Makaryczew M, Samardakiewicz M. Challenges in the Medical and Psychosocial Care of the Paediatric Refugee—A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710656

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlas, Jakub, Aleksandra Grzywacz, Katarzyna Kulszo, Arkadiusz Grunwald, Natalia Kluz, Mikołaj Makaryczew, and Marzena Samardakiewicz. 2022. "Challenges in the Medical and Psychosocial Care of the Paediatric Refugee—A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710656

APA StyleKlas, J., Grzywacz, A., Kulszo, K., Grunwald, A., Kluz, N., Makaryczew, M., & Samardakiewicz, M. (2022). Challenges in the Medical and Psychosocial Care of the Paediatric Refugee—A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710656