Abstract

Bedridden patients usually stay in bed for long periods, presenting several problems caused by immobility, leading to a long recovery process. Thus, identifying physical rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility requires urgent research. Therefore, this scoping review aimed to map existing physical rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility, the rehabilitation domains, the devices used, the parameters accessed, and the context in which these programs were performed. This scoping review, guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) methodology and conducted in different databases (including grey literature), identified 475 articles, of which 27 were included in this review. The observed contexts included research institutes, hospitals, rehabilitation units, nursing homes, long-term units, and palliative care units. Most of the programs were directed to the musculoskeletal domain, predominantly toward the lower limbs. The devices used included lower limb mobilization, electrical stimulation, inclined planes, and cycle ergometers. Most of the evaluated parameters were musculoskeletal, cardiorespiratory, or vital signs. The variability of the programs, domains, devices and parameters found in this scoping review revealed no uniformity, a consequence of the personalization and individualization of care, which makes the development of a standard intervention program challenging.

1. Introduction

The developed societies currently face a severe demographic change: the world is aging at an unprecedented rate [,]. In 2050, the world population over 65 years old will near 1500 million people, about 22 percent of the world population []. With the increase in the average human lifespan, the number of older persons with mobility impairment, namely bedridden patients, is growing. In addition, bedridden patients caused by accidents and chronic progressive conditions are increasing yearly [,,]. Recent studies have evidenced the economic impact on the institutions, highlighting that 25% of the resources might be used to care for bedridden patients [,] mainly due to the increased ventilator use and bed occupancy, which is why institutions are led to rethink recovery processes, namely seeking alternatives for acute care contexts.

Bedridden patients are usually kept in bed for long periods, slowly evidencing several problems caused by immobility []. Prolonged bed rest is the leading risk factor for the development of disuse syndrome, which causes significant systemic and organic pathological changes []. This is mainly due to the decompensation of the bedridden persons’ precarious physiological balance, after a significant reduction in their usual daily activities. Some manifestations are spatial-temporal disorientation, confusion, loss of automatic postural control, gait, and anatomic functional abnormalities. The latter involves all organs and apparatus and has psychological and metabolic repercussions [,].

The disuse syndrome, in the long term, increases the risk for the development of several conditions at a metabolic and systemic level. Some clinical entities to monitor and treat are joint contractures, sarcopenia, pressure sores, respiratory complications, and bone demineralization, which significantly decrease patients’ quality of life and delay the recovery process []. Many studies have shown that these complications are associated with increased morbidity and mortality [,], namely suggesting that 20 h of bed rest is sufficient to promote postural hypotension, and following 72 h, there is between 14 and 17% atrophy of muscle fibers [].

Moreover, the impact of complications of immobility on patients’ overall well-being and functioning is a topic of growing interest in clinical research and practice [,,]. Providing effective care, such as early rehabilitation, appears to hold promise in preventing disuse syndrome. This would involve early identification of the clinical signs associated with the development of immobilization syndrome and targeted interventions stressing mobilization, such as the prescription of simple exercises integrated into rehabilitation programs []. According to the available evidence, rehabilitation treatment can improve independence in patients with disuse syndrome; irrespective of the underlying cause [,]. Early mobilization is also an essential intervention among these patients. Although programs focusing on specific populations evidence positive effects [], adequate, structured, and efficient programs seem to be lacking [], considering that rehabilitation would be performed underlining personal goals and should be tailored to the main problem of the patient.

A shortage of those appropriately trained, a lack of demand, and a lack of human resources for rehabilitation constitute a severe strategic bottleneck for developing efficient institution and community-based services [,]. Therefore, providing human personnel with appropriate mechatronic devices or specialists with robots (integrating mechanics, electronics, sensors, intelligent control, actuators, and communication networks through integrated design) could reduce physicians’ physical and mental workloads []. Additionally, robots in rehabilitation therapies bring advantages over traditional treatments. They allow extensive practice in patients with substantial disabilities, reduce the effort required of therapists during the exercises, and provide a quantitative assessment of the patient’s motor function []. Ideally, these devices may allow the patient to do rehabilitation exercise training directly in bed without changing position, take up little space, and allow the patient to do rehabilitation in the hospital and at home [].

Therefore, this scoping review’s main objective is to map the existing physical rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility. More specifically, the research questions are:

- What are the physical rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients (e.g., neurological, orthopedic, and cardiorespiratory) with prolonged immobility?

- What is the context where the physical rehabilitation programs are implemented (e.g., institutions, community care, and outpatient)?

- What are the rehabilitation domains of the physical rehabilitation programs (motor, respiratory, and cardiorespiratory)?

- What kind of devices are used for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility (e.g., elastics, weights, crankset, and EMS)?

- What are the parameters assessed during the implementation of physical rehabilitation programs (e.g., muscle mass and oxygen saturation)?

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review follows the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [,,] and complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews guidelines (PRISMA-ScR) []. A protocol for this review has been previously published (Parola et al. []).

2.1. Search Strategy

The databases searched included: MEDLINE (via PubMed), CINAHL complete (via EBSCOhost), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (via EBSCOhost), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (via EBSCOhost), SciELO, Scopus, PEDro, SPORTDiscus with Full Text (via EBSCOhost), and Rehabilitation & Sports Medicine Source (via EBSCOhost). The search for unpublished studies included: DART-Europe and OpenGrey. The studies’ languages were limited to the ones mastered by the authors: English, Portuguese, and Spanish.

An initial limited search was undertaken on MEDLINE (via PubMed) and CINAHL Complete (via EBSCOhost) to identify articles on the topic. Consequently, the text words/expressions in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to develop a complete search strategy across all the databases. Additionally, the reference list of all included papers was hand-searched for additional studies. The inclusion criteria of this scoping review were based on the “PCC” mnemonic: Population, Concept, and Context. Accordingly, this review considered studies: that included programs for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility (Population) that explored physical rehabilitation programs (Concept) conducted in any setting independently of the country of the study (Context). We also considered quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods study designs for inclusion. Additionally, all types of systematic reviews were considered for inclusion independently of the publication date. The search strategy used in this scoping review can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

2.2. Data Extraction

All the records identified through database searching were retrieved and stored using Mendeley® V1.19.8 software (Mendeley Ltd., Elsevier, The Netherlands), and any duplications were removed. All identified articles were accessed for relevance according to the title and abstract. The full text of the selected citations was assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by two independent reviewers. The data were extracted from the articles and included in the review independently by two reviewers, using a data extraction table aligned with the objectives and research questions. The data extracted included: the author, year and country of the study, population characteristics, physical rehabilitation programs, accessed parameters, setting, and devices used. In the case of missing data, the study authors were contacted. Any disagreements regarding what data was relevant for extraction were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics, Settings, and Sample

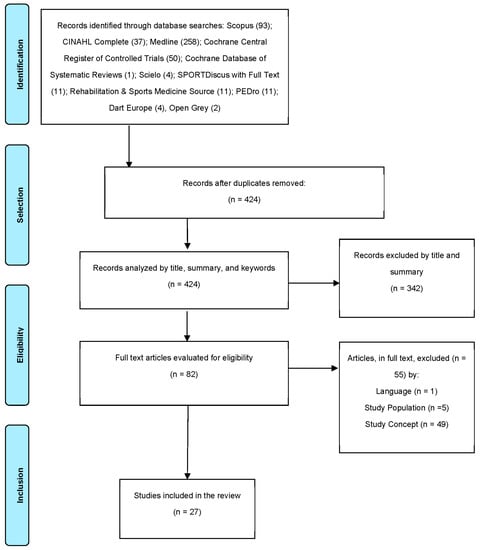

A total of 424 potentially relevant studies (after duplicates were removed) were identified for study selection, and a total of 342 studies were excluded by evaluation of the title and abstract. The full-text versions of the remaining 82 articles were read, and 27 were found to fulfill the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). These 27 articles were published between 1999 and 2020 and, combined, represented intervention studies on 1476 subjects. The mean age reported in the included studies ranged from 21.6 to 85.4 years old, and most patients represented were male. The studies took place in Belgium (n = 1), Brazil (n = 1), China (n = 2), Croatia (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), France (n = 2), Germany (n = 2), Italy (n = 3), Japan (n = 5), The Netherlands (n = 1), Poland (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 2), and USA (n = 2) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review process.

Table 2.

Articles including physical rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility.

3.2. Context

Most studies were performed in research institutes (n = 10) and hospital contexts (n = 10), followed on rehabilitation units (n = 3), welfare or nursing homes (n = 2), one long-term care facility (LTC) and one hospice. Studies performed in hospital context involved multiple conditions such as multi-trauma [], hip fracture [], sarcopenia [], older patients with unspecified conditions [,,], patients with COPD mechanical ventilated [], or other mechanical ventilated patients [], namely in the ICU [,]. Rehabilitation units involved patients with stroke [], patients with multiple sclerosis [], and one patient with head trauma caused by a car accident []. LTC facilities treated bedridden older stroke survivors []. In the welfare home, the programs were applied to bedridden patients with disuse syndrome [] and in nursing homes for bedridden patients with multiple conditions but mainly stroke []. Finally, one study described a rehabilitation program in a hospice setting for palliative patients with fewer than three months’ life expectancy (mainly due to cancer diagnosis) [].

3.3. Programs and Domains

Most rehabilitation programs were directed to the musculoskeletal domain (n = 14). The other seven were directed to the cardiorespiratory domain and six to mixed/other domains. Most of the programs included in this scoping were applied only to lower limbs [,,,,,,], also including [], which only focused on toe joints. On the other hand, two studies [,] worked on both upper and lower limbs, and three studies [,,] worked on the upper and lower body. Regarding the programs in the cardiorespiratory domain, three studies [,,] mainly focused on respiratory rehabilitation: one [] was primarily cardiovascular, whereas three [,,] worked on both the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. The other six [,,,,,] were classified as mixed or other domains because multiple domains were present, and the programs were not explicit or focused on other rehabilitation domains, such as [], which combined nutrition, exercise, and pharmacotherapy. Given its variability from study to study, and that not all studies have this information, the aspects related to the duration of the study and sessions: frequency, intensity, and progressivity, are presented in Table 2.

3.4. Devices

More than half (n = 17; ~63%) of the above-described rehabilitation programs used rehabilitation devices. Of those devices, 11 were commercial devices, and the remaining 6 were prototypes. In the musculoskeletal programs, devices of different nature were used. Four studies [,,,] used devices for lower limb mobilization with different typologies (flywheel ergometer, leg press, and ankle or leg mobilizer), whereas one [] used elastic bands, and [] used a device for passive mobilization of toe joints. Devices for electrical stimulation were also widely used in the musculoskeletal [,,], cardiorespiratory [,,], and other/mixed domains []. Tilt tables for verticalization were also used in both musculoskeletal [], cardiorespiratory [], and mixed domains []. Two studies [,] used the commercial ERIGO tilt table, whereas the brand of this device used in one of the studies [] was not specified. In the cardiorespiratory domain, the cycle ergometer was also common [,].

3.5. Clinical Parameters

A huge variety of parameters were accessed in the selected studies of this scoping to access the efficacy and safety of the above-described rehabilitation programs as the devices used in these programs. Most of the evaluated parameters were musculoskeletal, cardiorespiratory, or vital signs. In the musculoskeletal domain, the principal parameters accessed were muscular volume (using MRI) []. muscle strength [,,] (mainly using the MRC scale), handgrip strength (using a dynamometer) [], and force power (using a load cell) []. Still, in this domain, range of motion (ROM) [,], joint angular velocity [], and angle measures [] were also evaluated. Other techniques, such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry to measure bone mineral density [] and EMG [], were used.

In the cardiorespiratory domain, the main parameters evaluated for the cardiovascular system were electrocardiogram [] and cardiac output using cardiac Doppler ultrasound [], and lower limb blood flow [,]. For the respiratory system, the main parameters were tidal volume [], forced vital capacity (FVC) [,], cough efficacy (pulmonary index) [], peak cough flow (PCF) [], and respiratory muscle strength using spirometry and maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressure (PImax and PEmax) measured with a manometer [].

Vital signs [] such as HR [,,], RR [,,], blood pressure: mean [] systolic and diastolic blood pressure [], SpO2 [], and body temperature [] were also frequently accessed. Two studies also evaluated neurological parameters such as brain activity using Electroencephalography (EEG) [] and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) [,] and the memory performance using MRI and fMRI []. A variety of biomarkers were also accessed in some studies, such as urine and blood biomarkers of bone metabolism (e.g., 25-hydroxy- and 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, calcium, and osteocalcin) []; nutritional biomarkers (albumin) []; inflammatory biomarkers such as interleukins [] and c-reactive protein [,]; and renal function biomarkers such as creatinine and cystatin []. Other clinical information such as the history of weight loss, triceps skinfold, dietary records [], calf and arm circumferences [], and BMI [,,] was also recorded in some studies.

4. Discussion

This scoping review mapped the different rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients described in 27 primary studies elaborated between 1999 and 2020, specifically including the domains studied, devices used, parameters accessed, and the context in which these programs were performed.

4.1. Context

Regarding the context, we observed that a large number of studies were performed in research institutes with healthy controls; thus, at the time of publication of these studies, the respective programs were not yet implemented in a clinical context. On the other hand, this also demonstrates the importance of performing preclinical and clinical studies with healthy individuals [,] to access the rehabilitation program’s safety, since bedridden persons are often in a great state of fragility with a considerable variety of diseases and comorbidities [,]. A large number of studies were also performed in a hospital context. In this context, we observed that programs were applied to people with very different diseases (from hip fracture to stroke). On the other hand, other studies in the hospital context [,] and welfare/nursing homes [,] included patients (mostly older) with disuse syndrome, irrespective of the underlying cause [,]. Two studies [,] were specifically applied in the ICU context, demonstrating the importance of rehabilitation in intensive care to be performed as soon as possible [,]. Since rehabilitation is a continuous process [], it can be started in the hospital but continued in rehabilitation centers and LTC, as observed in [,,,]. We also noticed a lack of studies on rehabilitation programs applied at home, possibly due to some barriers to implementing rehabilitation programs at home [,].

4.2. Domains

In this scoping review, we observed that most of the programs were directed to the musculoskeletal domain and, more specifically, the lower limbs. A lack of motor ability in the lower extremity affects walking ability balance and increases the risk of a fall []; on the other hand, it is the primary determinant of an independent and productive life and ADL [,]. Regarding the programs in the cardiorespiratory domain, two studies mainly focused on respiratory rehabilitation in ventilated persons [,]. This is especially important in this time of COVID-19 due to the number of persons that must be mechanically ventilated. Siddiq et al. [] conducted a scoping review based on 40 recent publications demonstrating pulmonary rehabilitation’s importance. In this article, Siddiq et al. argued that survivors weaned from mechanical ventilation are at a higher risk of developing post-intensive care syndrome and that respiratory rehabilitation should be started at the earliest possible opportunity []. However, we must stress that persons admitted to ICU due to COVID-19 or other causes will also need musculoskeletal rehabilitation since people who stay in the ICU are also at risk of developing post-intensive care syndromes, which are defined as “physical, cognition, and mental impairments that occur during ICU stay, after ICU discharge or hospital discharge, as well as in the long-term follow up of ICU patients” []. Indeed, the programs classified as mixed domains in Table 2 demonstrate the need in certain cases of rehabilitation that comprise different domains.

4.3. Devices

Evidence shows us how devices can be an essential complement to the care provided to bedridden users [,,,]. In fact, in this scoping review, more than 60% of the included studies used devices as a compliment. Of those, 11 were commercial, and the remaining 6 were prototypes. Thus, although professionals already use commercial devices, an investment in the development of new devices adjusted to the population’s specific needs continues to be necessary. These devices are intended to fill gaps to which existing devices cannot yet respond []. In this scoping review, we also found that studies in the aerospatial scope [,] can be transported to the reality of clinical practice, even though their use was in a different scope. These studies focus on muscle and bone loss, which is a reality observed in long-duration missions in orbit and bedridden patients.

4.4. Parameters

This study observed a significant variability of parameters used to evaluate the implemented programs. The use of different parameters is often due to the study’s specific objectives, the contexts where they are implemented, the specificities of the population being studied, and the available resources. It is important to emphasize the adequacy of using the selected parameters concerning what is intended to be evaluated. However, the significant variability of the evaluated parameters may severely impair study comparison. This can pose a challenge for the development of, for example, systematic reviews of effectiveness, as there is no homogeneity between studies to carry out a meta-analysis []. The parameters most used in the different studies concern vital signs, namely the heart and the respiratory rates. Their use is essential for monitoring the safety of studies that focus on interventions for bedridden patients. Another observed aspect was the absence of specific information regarding muscular and osteoarticular risks, specifically in the control of joint stability during movement, a relevant aspect, especially when talking about complementary/robotic devices [].

4.5. Limitations

In this scoping review, we subdivided the programs into musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory domains. However, the line that separates them can be thin, because programs directed to the musculoskeletal domain can also benefit the cardiorespiratory domain and vice versa. Another limitation was that some studies did not present part of the information we intended to map, such as a complete characterization of the population, rehabilitation programs, or devices used, making it difficult to obtain all the information intended from the studies individually. Despite this limitation, we tried to extract as much information as possible from different studies to map all the available evidence. Another potential limitation of this scoping review was that only studies published in English, Portuguese, and Spanish were included. Articles published in other languages may potentially add information to the results of this review. Furthermore, since the objective of this scoping review was to map the physical rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility, no rating of the methodological quality was used. Although a critical appraisal of the included studies was not evaluated, since it was not relevant for the scoping review, some limitations were reported to provide valuable information to future research studies/systematic reviews.

5. Conclusions

To date, no previous scoping reviews addressing this purpose have been found. Therefore, this scoping review constitutes a valuable starting point for analyzing and systematizing the rehabilitation programs used for bedridden patients. Additionally, which devices were used, the implementation context and the parameters accessed were analyzed.

There is a great diversity of programs with different structures and variability in both devices and parameters to be evaluated. This review revealed no standardization of these components, making developing a standard intervention program challenging. This occurs since the programs and their components are adjusted to the specificities of the population under study, requiring individualization to meet the individual needs of specific patients. According to this evidence, rehabilitation treatment can improve independence in patients with immobilization syndrome, irrespective of the underlying cause, as described previously by Bocciogne et al. [].

Mapping the evidence about physical rehabilitation programs for bedridden patients with prolonged immobility contributes to understanding this phenomenon, helping health professionals and stakeholders develop more adjusted programs and which parameters should be considered. Therefore, this mapping contributed to the identification of relevant issues to help advance evidence-based rehabilitation interventions, construct knowledge, identify gaps, and inform systematic reviews.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C., V.P., H.N., R.A.B., F.M.D., P.C., F.P., C.A., L.B.S., P.P., J.A. and A.C.; funding acquisition, V.P., L.B.S., C.M., R.D., W.X., P.P., J.A. and A.C.; supervision, R.C., V.P., H.N., R.A.B., P.C., F.P., C.A., C.M., R.D., W.X., P.P., J.A. and A.C.; visualization, R.C., V.P., H.N., F.M.D., R.A.B., C.A.M., M.P. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation R.C., V.P., H.N., R.A.B., C.A.M., M.P., P.P. and A.C.; and writing—review and editing, R.C., V.P., H.N., R.A.B., F.M.D., C.A.M., M.P., P.C., F.P., C.A., L.B.S., C.M., R.D., W.X., P.P. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the partnership agreement Portugal 2020—Operational Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalization (COMPETE2020) under the project POCI-01-0247-FEDER-047087 ABLEFIT: Desenvolvimento de um Sistema avançado para Reabilitação.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing (UICISA: E), Nursing School of Coimbra, Portugal, and the Portugal Centre for Evidence-Based Practice: a Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Portugal (PCEBP).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pereira, F.; Carvalho, V.; Soares, F.; Machado, J.; Bezerra, K.; Silva, R.; Matos, D. Development of a mechatronic system for bedridden people support. In Advances in Engineering Research; Nova Science Publisher: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Andone, I.; Popescu, C.; Spinu, A.; Daia, C.; Stoica, S.; Onose, L.; Anghel, I.; Onose, G. Current aspects regarding “smart homes”/ambient assisted living (AAL) including rehabilitation specific devices, for people with disabilities/special needs. Balneo Res. J. 2020, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orun, B.; Roesler, C.; Martins, D. Review of Assistive Technologies for Bedridden Persons. ResearchGate. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bilal-Orun/publication/283459329_Review_of_assistive_technologies_for_bedridden_persons/links/5638bbda08ae78d01d39fa44/Review-of-assistive-technologies-for-bedridden-persons.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Jiang, C.; Xiang, Z. A Novel Gait Training Device for Bedridden Patients’ Rehabilitation. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zongxing, L.; Xiangwen, W.; Shengxian, Y. The effect of sitting position changes from pedaling rehabilitation on muscle activity. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 24, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Wang, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Jiao, J.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Liu, H.; et al. Factors associated with death in bedridden patients in China: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salz, I.W.; Carmeli, Y.; Levin, A.; Fallach, N.; Braun, T.; Amit, S. Elderly bedridden patients with dementia use over one-quarter of resources in internal medicine wards in an Israeli hospital. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2020, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Cao, J.; Jia, Z.; Wan, X.; Jiao, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; et al. Nursing resources and major immobility complications among bedridden patients: A multicenter descriptive study in China. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.; Cortés, E.; Martins, D.; Ferre, M.; Contreras, A. Development of a flexible rehabilitation system for bedridden patients. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, L.P.C.M.; De Oliveira, M.L.C.; Carvalho, G.D.A. Deleterious effects of prolonged bed rest on the body systems of the elderly. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2018, 21, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.N.; Smeuninx, B.; Morgan, P.T.; Breen, L. Nutritional Strategies to Offset Disuse-Induced Skeletal Muscle Atrophy and Anabolic Resistance in Older Adults: From Whole-Foods to Isolated Ingredients. Nutrition 2020, 12, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, H.; Ikegawa, N.; Nozoe, M.; Kamiya, K.; Matsumoto, S. Association between Skeletal Muscle Mass Index and Convalescent Rehabilitation Ward Achievement Index in Older Patients. Prog. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 7, 20220003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Cao, J.; Jiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Song, B.; Jin, J.; et al. The association between major complications of immobility during hospitalization and quality of life among bedridden patients: A 3 month prospective multi-center study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Cao, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Zhu, C.; Song, B.; Jin, J.; et al. Risk factors for 3-month mortality in bedridden patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia: A multicentre prospective study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousignant-Laflamme, Y.; Beaudoin, A.-M.; Renaud, A.-M.; Lauzon, S.; Charest-Bossé, M.-C.; Leblanc, L.; Grégoire, M. Adding physical therapy services in the emergency department to prevent immobilization syndrome—A feasibility study in a university hospital. BMC Emerg. Med. 2015, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, R.; Watanabe, H.; Tsutsumi, M.; Kanamori, T.; Maeno, T.; Yanagi, H. Factors associated with the recovery of activities of daily living after hospitalization for acute medical illness: A prospective cohort study. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 2763–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rocha, A.M.; Martinez, B.; da Silva, V.M.; Junior, L.F. Early mobilization: Why, what for and how? Med. Intensiv. 2017, 41, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlinchey, M.P.; James, J.; McKevitt, C.; Douiri, A.; Sackley, C. The effect of rehabilitation interventions on physical function and immobility-related complications in severe stroke: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-León, J.F.; Chaparro-Rico, B.D.M.; Russo, M.; Cafolla, D. An Autotuning Cable-Driven Device for Home Rehabilitation. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6680762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, B.; MacLachlan, M.; McVeigh, J.; McClean, C.; Carr, S.; Duttine, A.; Mannan, H.; McAuliffe, E.; Mji, G.; Eide, A.H.; et al. A study of human resource competencies required to implement community rehabilitation in less resourced settings. Hum. Resour. Health 2017, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaj, J.; Klimasara, W.J.; Pilat, Z.; Rycerski, W. Human-Robot Communication in Rehabilitation Devices. J. Autom. Mob. Robot. Intell. Syst. 2015, 9, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Garcia, L.; Kilby, J.; McNair, P. Robotic devices for pediatric rehabilitation: A review of design features. Biomed. Eng. Online 2021, 20, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; Mcinerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H.; Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Parker, D. An Evidence-Based Approach to Scoping Reviews. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parola, V.; Neves, H.; Duque, F.M.; Bernardes, R.A.; Cardoso, R.; Mendes, C.A.; Sousa, L.B.; Santos-Costa, P.; Malça, C.; Durães, R.; et al. Rehabilitation Programs for Bedridden Patients with Prolonged Immobility: A Scoping Review Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkner, B.A.; Tesch, P.A. Efficacy of a gravity-independent resistance exercise device as a countermeasure to muscle atrophy during 29-day bed rest. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2004, 181, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, B.S. Regulating artificial gravity forces in space exploration. In Proceedings of the 47th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, Orlando, FL, USA, 5–8 January 2009; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Inc.: Reston, VA, USA; School of Architecture, Marvin Hall, University of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc-Bisson, C.; Dechamps, A.; Gouspillou, G.; Dehail, P.; Bourdel-Marchasson, I. A randomized controlled trial on early physiotherapy intervention versus usual care in acute car unit for elderly: Potential benefits in light of dietary intakes. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2008, 12, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, R.S.; Naro, A.; Russo, M.; Leo, A.; Balletta, T.; Saccá, I.; De Luca, R.; Bramanti, P.; RS, C.; Naro, A.; et al. Do post-stroke patients benefit from robotic verticalization? A pilot-study focusing on a novel neurophysiological approach. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2015, 33, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, K.L.; Loehr, J.A.; Lee, S.M.C.; Smith, S.M. Early-phase musculoskeletal adaptations to different levels of eccentric resistance after 8 weeks of lower body training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 114, 2263–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golčić, M.; Dobrila-Dintinjana, R.; Golčić, G.; Gović-Golčić, L.; Čubranić, A. Physical Exercise: An Evaluation of a New Clinical Biomarker of Survival in Hospice Patients. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2018, 35, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ino, S.; Hosono, M.; Sato, M.; Nakajima, S.; Yamashita, K.; Izumi, T. A Preliminary Study of a Power Assist System for Toe Exercise Using a Metal Hydride Actuator; Springer: Tsukuba, Japan, 2009; Volume 25, pp. 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- Maimaiti, P.; Sen, L.F.; Aisilahong, G.; Maimaiti, R.; Yun, W.Y. Retracted: Statistical analysis with Kruskal Wallis test for patients with joint contracture. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 92, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaccio, S.; Garavaglia, L.; Molteni, E.; Guanziroli, E.; Zappasodi, F.; Beretta, E.; Strazzer, S.; Molteni, F.; Villa, E.; Passaretti, F. Can passive mobilization provide clinically-relevant brain stimulation? A pilot EEG and NIRS study on healthy subjects. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. Annu. Int. Conf. 2013, 2013, 3547–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Kamada, H.; Sakane, M.; Aikawa, S.; Mutsuzaki, H.; Tanaka, K.; Mishima, H.; Kanamori, A.; Nishino, T.; Ochiai, N.; et al. A novel exercise device for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis improves venous flow in bed versus ankle movement exercises in healthy volunteers. J. Orthop. Surg. 2017, 25, 2309499017739477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talar, J. Rehabilitation outcome in a patient awakened from prolonged coma. Med. Sci. Monit. 2002, 8, CS31–CS38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.-N.; Chen, C.-H.; Wu, S.-C.; Lin, L.-C. Effects of a range-of-motion exercise programme. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 57, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinstrup, J.; Skals, S.; Calatayud, J.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Sundstrup, E.; Pinto, M.D.; Izquierdo, M.; Wang, Y.; Zebis, M.K.; Andersen, L.L. Electromyographic evaluation of high-intensity elastic resistance exercises for lower extremity muscles during bed rest. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 2017, 178, 261–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, H.; Nakashima, S.; Aoki, H.; Goto, K.; Yamashita, J.; Honda, Y.; Kondo, Y.; Hirase, T.; Sakamoto, J.; Okita, M. Electrical Stimulation in Addition to Passive Exercise Has a Small Effect on Spasticity and Range of Motion in Bedridden Elderly Patients: A Pilot Randomized Crossover Study. Health 2019, 11, 1072–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Akar, O.; Günay, E.; Sarinc Ulasli, S.; Ulasli, A.M.; Kacar, E.; Sariaydin, M.; Solak, Ö.; Celik, S.; Ünlü, M. Efficacy of neuromuscular electrical stimulation in patients with COPD followed in intensive care unit. Clin. Respir. J. 2017, 11, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Lin, H.-L.; Hsiao, H.-F.; Chou, L.-T.; Kao, K.-C.; Huang, C.-C.; Tsai, Y.-H. Effects of Exercise Training on Pulmonary Mechanics and Functional Status in Patients with Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation. Respir. Care 2012, 57, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselink, R.; Kovacs, L.; Ketelaer, P.; Carton, H.; Decramer, M. Respiratory muscle weakness and respiratory muscle training in severely disabled multiple sclerosis patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Gao, C.; Xin, H.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Wei, Z.; Yue, Y. The application of “upper-body yoga” in elderly patients with acute hip fracture: A prospective, randomized, and single-blind study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafreshi, A.S.; Okle, J.; Klamroth-Marganska, V.; Riener, R. Modeling the effect of tilting, passive leg exercise, and functional electrical stimulation on the human cardiovascular system. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2017, 55, 1693–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedl-Werner, A.; Brauns, K.; Gunga, H.-C.; Kühn, S.; Stahn, A.C. Exercise-induced changes in brain activity during memory encoding and retrieval after long-term bed rest. NeuroImage 2020, 223, 117359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrinal, C.; Combret, Y.; Prieur, G.; Quesada, A.R.; Bonnevie, T.; Gravier, F.E.; Frenoy, É.; Contal, O.; Lamia, B. Effects of different early rehabilitation techniques on haemodynamic and metabolic parameters in sedated patients: Protocol for a randomised, single-bind, cross-over trial. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2017, 4, e000173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccignone, A.; Abelli, S.; Ortolani, L.; Ortolani, M. Functional outcomes following the rehabilitation of hospitalized patients with immobilization syndromes. Eura. Medicophys. 1999, 35, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Masuda, Y.; Kimata, T.; Uemura, K.; Kuzuya, M.; Iguchi, A. Effects of home massage rehabilitation therapy for the bed-ridden elderly: A pilot trial with a three-month follow-up. Clin. Rehabil. 2005, 19, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.A.; Osaku, E.F.; Albert, J.; Costa, C.R.L.D.M.; Garcia, A.M.; Czapiesvski, F.D.N.; Ogasawara, S.M.; Bertolini, G.R.F.; Jorge, A.C.; Duarte, P.A.D. Effects of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation of the Quadriceps and Diaphragm in Critically Ill Patients: A Pilot Study. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendt, S.; Gunga, H.-C.; Felsenberg, D.; Belavy, D.L.; Steinach, M.; Stahn, A.C. Regular exercise counteracts circadian shifts in core body temperature during long-duration bed rest. Npj Microgravity 2021, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, M.; Kumagai, S.; Abe, T.; Murakami, S.; Takeda, H.; Shichinohe, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Katayama, S.; Hirai, S.; Honda, A.; et al. Sarcopenia in a patient with most serious complications after highly invasive surgeries treated with nutrition, rehabilitation, and pharmacotherapy: A case report. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2021, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, A.I.E.; Hemmen, B.; Evers, S.M.A.A.; Van De Meent, H.; Ambergen, T.; Vos, P.E.; Brink, P.R.G.; Seelen, H.A.M. Effects of an Integrated ‘Fast Track’ Rehabilitation Service for Multi-Trauma Patients: A Non-Randomized Clinical Trial in the Netherlands. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresser, R. First-in-Human Trial Participants: Not a Vulnerable Population, but Vulnerable Nonetheless. J. Law Med. Ethic 2009, 37, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakunnel, J.J.; Bui, N.; Palaniappan, L.; Schmidt, K.T.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Morrison, B.; Figg, W.D.; Kummar, S. Reviewing the role of healthy volunteer studies in drug development. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiq, M.A.B.; Rathore, F.A.; Clegg, D.; Rasker, J.J. Pulmonary Rehabilitation in COVID-19 patients: A scoping review of current practice and its application during the pandemic. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 66, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stam, H.J.; Stucki, G.; Bickenbach, J. COVID-19 and Post Intensive Care Syndrome: A Call for Action. J. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 52, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagin, R.; Hagani, N.; Levy, I.; Norman, D. There Is No Place Like Home: A Survey on Satisfaction and Reported Outcomes of a Home-Based Rehabilitation Program Among Orthopedic Surgery Patients. J. Patient Exp. 2019, 7, 1715–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, C.; Klinger, E.; Dorner, V.; Kadri, A.; Thierry, O.; Boumenir, Y.; Martin, W.; Poiraudeau, S.; Ville, I. Barriers to home-based exercise program adherence with chronic low back pain: Patient expectations regarding new technologies. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 59, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Veen, D.J.; Döpp, C.M.E.; Siemonsma, P.C.; Der Sanden, M.W.G.N.-V.; De Swart, B.J.M.; Steultjens, E.M. Factors Influencing the Implementation of Home-Based Stroke Rehabilitation: Professionals’ Perspective. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Gong, W.; Kim, S.G. The Effects of Lower Extremitiy Muscle Strengthening Exercise and Treadmill Walking Exercise on the Gait and Balance of Stroke Patients. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2011, 23, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscedere, J.; Sinuff, T.; Heyland, D.K.; Dodek, P.M.; Keenan, S.P.; Wood, G.; Jiang, X.; Day, A.G.; Laporta, D.; Klompas, M.; et al. The Clinical Impact and Preventability of Ventilator-Associated Conditions in Critically Ill Patients Who Are Mechanically Ventilated. Chest 2013, 144, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, R.A.; Santos-Costa, P.; Sousa, L.B.; Graveto, J.; Salgueiro-Oliveira, A.; Serambeque, B.; Marques, I.; Cruz, A.; Parreira, P. Innovative devices for bedridden older adults upper and lower limb rehabilitation: Key characteristics and features. Int. Workshop Gerontechnol. 2020, 1185 CCIS, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 3: Systematic Reviews of Effectiveness. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; ISBN 978-0-648-84880-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chapter 12—Regional Complications in Joint Hypermobility Syndrome. In Grahame Fibromyalgia and Chronic Pain; Hakim, A.J., Keer, R., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 2010; pp. 197–280. ISBN 978-0-7020-3005-5. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).