Abstract

Advances in experimental psychology have provided evidence for the presence of attentional and approach biases in individuals with substance use disorders. Traditionally, reaction time tasks, such as the Stroop or the Visual Probe Task, are commonly used in the assessment of attention biases. The Visual Probe Task has been criticized for its poor reliability, and other research has highlighted that variations remain in the paradigms adopted. However, a gap remains in the published literature, as there have not been any prior studies that have reviewed stimulus timings for different substance use disorders. Such a review is pertinent, as the nature of the task might affect its effectiveness. The aim of this paper was in comparing the different methods used in the Visual Probe Task, by focusing on tasks that have been used for the most highly prevalent substance disorders—that of opiate use, cannabis use and stimulant use disorders. A total of eight published articles were identified for opioid use disorders, three for cannabis use disorders and four for stimulant use disorders. As evident from the synthesis, there is great variability in the paradigm adopted, with most articles including only information about the nature of the stimulus, the number of trials, the timings for the fixation cross and the timings for the stimulus set. Future research examining attentional biases among individuals with substance use disorders should take into consideration the paradigms that are commonly used and evaluate the optimal stimulus and stimulus-onset asynchrony timings.

1. Overview of Attention Bias Assessment and Modification

Advances in experimental psychology have provided evidence for the presence of attentional and approach biases in individuals with substance use disorders. Attentional biases result in individuals having a preferential allocation of their attentional processes to substance-related stimuli [1], while approach biases result in individuals having automatic action tendencies in reaching out for substance-related cues [2]. Various theories have provided explanations for the presence of these biases, including that of the incentive-sensitization theory, the classical conditioning theory and that of the dual-process theory [3]. The dual-process theory is most commonly used in the justification of the presence of attentional biases. It postulates that the repeated use of a substance would result in increased automatic processing and increased automatic tendencies to approach substance-specific cues, with the inhibition of normal cognitive control processes [3]. The discovery and the understanding of these unconscious, automatic biases are of importance clinically, as they help to account for the lapses and relapses among individuals with substance use disorders [4]. Recent neuroimaging studies have highlighted that attentional biases are associated with increased activation in several neuroanatomical regions, including that of the anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, insula, nucleus accumbens and amygdala [5,6].

Traditionally, reaction time tasks, such as the Stroop or the Visual Probe Task, are commonly used in the assessment of attention biases [1]. In the Stroop task, individuals are required to name the colours of both the neutral and the drug-related words. In the Visual Probe Task, participants are required to respond readily to a probe that would replace either the neutral or the drug image. Attentional biases are deemed to be present if individuals respond more readily to a probe or words that replace substance-related images, as compared to the neutral word or images [1]. Ataya et al. (2012) [7] previously reported that both these tasks (the Stroop and Visual Probe Task) are associated with poor internal reliability. Field et al. (2012) [8] have postulated that one of the factors that could account for the poor reliability of the Visual Probe Task pertains to the type of stimulus used. Thus, the authors proposed the use of a personalised stimulus and images that participants could readily identify with. In turn, this could then result in a more demonstrable change in biases [8]. In a review by Lopes et al. (2015) [9], they reported that the Visual Probe Task was effective—in 88% of the studies involving individuals with substance use disorders, there was successful retraining of attentional biases. Jones et al. (2018) [10], in their recent study, have explored methods to improve the internal reliability of the Visual Probe Task. The authors examined the nature of the stimulus included, adopting the previous suggestion of having a personalised stimulus and reported that the inclusion of a personalised stimulus did help to improve the internal consistency of the Visual Probe Task.

Nevertheless, the authors still report the Visual Probe Task to be unreliable and that reliabilities were acceptable if the stimulus cues were presented for short intervals. Jones et al. (2018) [10], in their review, highlighted that there is great variation in the timings of the stimulus intervals used in published studies involving addiction. However, a gap remains in the published literature, as there have not been any prior studies that have reviewed the stimulus timings for the different substance use disorders. Such a review is pertinent, as the nature of the task might affect its effectiveness. Given this, our aim was to compare the different task paradigms and methods for the Visual Probe Tasks used for the most highly prevalent substance disorders—that of opiate use, cannabis use and stimulant use disorders.

2. Visual Probe Trask Paradigms in Published Studies

Two recent reviews have synthesised the evidence for attentional biases among substance users. Maclean et al. (2018) [11] identified 21 studies that have previously examined attentional biases in opioid using individuals. Zhang et al. (2018) [4] identified 11 articles involving participants with opioid use disorder, 16 articles with participants with stimulant use disorders and nine articles involving participants with cannabis use disorders. In order to fulfil our aim, we will describe the Visual Probe Task paradigms (the methods of the Visual Probe Tasks) that have been used in each of the published studies.

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of the Visual Probe Task that were utilized in previous studies involving individuals with opioid use disorders. From both Maclean et al. (2018)’s [11] and Zhang et al. (2018)’s [4] review, we managed to identify a total of eight articles that specified the use of the Visual Probe Task for attention bias assessment or modification. We were unable to access the full text of one of the journals as it was published in a Chinese Journal. In the identified articles, there was great variability in the number of stimulus included, ranging from 12 to 44 picture pairs. Some studies included as few as 64 trials [12,13], while others included as many as 512 trials [14]. Across the studies, there was great variation in the Visual Probe Task. Most of the studies presented the fixation cross for 500 ms, except Frankland et al. (2016) [15] and Zhao et al. (2017) [16], who presented the fixation cross for 1000 ms. Several studies have presented the stimulus and neutral image set for both a short and long duration [12,13,14,15,17,18]. The short stimulus timing was commonly that of 200 ms, and the long stimulus timing was that of 2000 ms, though, in Frankland et al. (2016)’s [15] study, they presented the images for 500 and 1500 ms as well.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Visual Probe Task used in previous studies involving individuals with opioid dependence (n = 8).

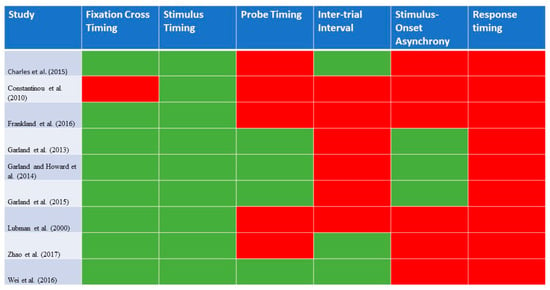

While all the studies explicitly stated that they were based on the Visual Probe Task, there were variations in the nature of the task. Some studies [12,13,18] have included an interstimulus interval, before the presentation of the probe. Also, in some studies, the probe remained on the screen until the participant made a response [14,16,17], while in other studies, the probe only appeared for 100 ms, before disappearing [12,13,18]. Some studies also included an inter-trial interval, but there was variation in the timing of this interval (from 250 to 2000 ms). Some of the studies [15,16,19] have included practice trials. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the details of the Visual Probe Task that were reported in each of the identified studies for opioid use disorder.

Figure 1.

A graphical representation of the details of the Visual Probe Task that were reported in each of the identified studies for opioid use disorder (n = 8). Green highlights: reported in study; red highlights: not reported in study.

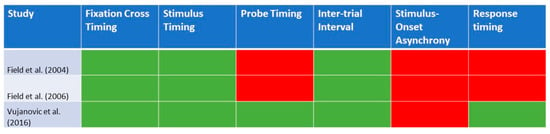

Table 2 provides an overview of the characteristics of the Visual Probe Task that was utilized in previous studies involving individuals with cannabis use disorders. A total of three articles from Zhang et al. (2018)’s [4] prior review were included, as they have reported the use of the Visual Probe Task. For the stimulus, Field et al. (2004) [21] included words instead of pictorial stimuli. In terms of the Visual Probe Task, two studies [21,22] presented the fixation cross for 500 ms, whereas Field et al. (2006) [23] presented it for 1000 ms. There was again variation in the timings for the stimuli cues, with two studies [21,22] presenting the stimulus cue for 500 ms, whereas that of Field et al. (2006) [23] presented it for 2000 ms. In terms of probe presentation, two studies presented the probe [21,22] until a response was made. Vujanovic et al. (2016) [22], presented the probe for 125 or 250 ms. Across all the studies, they have included an inter-trial interval, which ranged from 1000 to 1500 ms. In terms of the number of trials, it ranged between 72 and 96. All the studies included practice trials for participants. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the details of the Visual Probe Task that were reported in each of the identified studies for cannabis use disorder.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Visual Probe Task used in previous studies involving individuals with cannabis dependence.

Figure 2.

A graphical representation of the details of the Visual Probe Task that were reported in each of the identified studies for cannabis use disorder (n = 3). Green highlights: reported in study; red highlights: not reported in study.

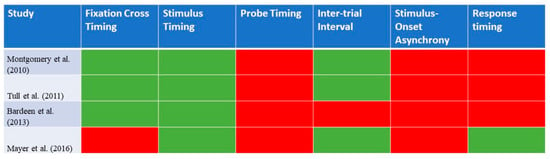

Table 3 provides an overview of the characteristics of the Visual Probe Task that were utilized in the previous studies involving individuals with stimulant use disorders—that of cocaine use disorders. A total of four articles from Zhang et al. (2018)’s [4] prior review was included. While all the studies have their basis in the Visual Probe Task, there was variability in the paradigms. Some studies included 10 sets of images [24], while others [25,26] included up to 20 sets of images. There was variation in the number of trials individuals had to undertake, ranging from 80 to 240 trials. Two studies [25,26] reported the inclusion of practice trials. Three out of the four studies reported that they presented a fixation cross for 500 ms. In terms of stimulus timings, they were presented for 500 ms in three studies [24,25,26] and for a short (200 ms) and long (500 ms) interval in Mayer et al. (2016)’s study [27]. In all of the studies, the probe appeared up until a response was made. Only two of the four identified studies allowed for an inter-trial interval [24,27]. There was variation in the inter-trial interval, as it ranged from 500 to 1500 ms. Figure 3 provides a graphical representation of the details of the Visual Probe Task that were reported in each of the identified studies for stimulant use disorder.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the Visual Probe Task used in previous studies involving individuals with stimulant dependence.

Figure 3.

A graphical representation of the details of the Visual Probe Task that were reported in each of the identified studies for stimulant use disorder (n = 4). Green highlights: reported in study; red highlights: not reported in study.

3. Implications for Future Research

It is apparent that there is great variability in the paradigm of the Visual Probe Task. In addition, there is also a varied amount of information shared about the nature of the paradigm. Most of the articles included information about the nature of the stimulus, the number of trials, the timings for the fixation cross and the timings for the stimulus set. However, information is missing in some studies, with regards to the inter-stimulus interval, the time that the probe appears for, the inter-trial interview and the time allocated for the individual to response. The absence of this information limits the reproducibility of the Visual Probe Task by others. For future research, it is essential that the intervention is described in full, carefully specifying the full methodology of the Visual Probe Task used, in order to allow for the replication of studies.

While there were clear variations in the paradigms, there were some common elements across all the studies. For studies involving participants with opioid use disorders, most of the studies presented the fixation cross for 500 ms and presented the set of stimulus images for both a short and long stimulus duration. A shorter stimulus duration would allow for the evaluation of the initial, automatic detection attentional processes, while a longer stimulus duration would allow for the evaluation of the engagement stages of attention [9]. In contrast, for studies involving participants with cannabis use or stimulant use disorders, the stimulus pair was most commonly presented for 500 ms. Most of the studies utilizing these timings have provided positive findings for attentional biases, except for Charles et al. (2015) [14] and Mayer et al. (2016) [27].

This evidence synthesis has direct implications for future research. We propose that future studies assessing and modifying attentional biases among individuals with opioid use disorders should consider the use of both a short and long stimulus timing, whereas studies evaluating attentional processes among people using cannabis or with stimulant disorders could use a single stimulus interval. To date, there is only a single study (Mayer et al., 2016) [27] that has examined a varying timing stimulus for individuals with stimulant use disorder. Future research should also examine whether the presence of a varying stimulus timing interval will enhance the detection and modification of attentional biases among individuals with cannabis and stimulant use disorders.

From the studies that we have included, there were a limited number of studies that have reported the stimulus-onset asynchrony timings. Lopes et al. (2015) [9], in their prior review exploring the Visual Probe Task for various disorders, have reported that there was variation in the timings for the different psychiatric disorders. For substance use disorders, it ranged from 50 to 500 ms; for depressive disorders, it ranged from 500 to 2000 ms; and for anxiety disorders, it ranged from 200 to 1500 ms. Lopes et al. (2015) [9] have previously highlighted that a relatively longer stimulus duration is advantageous as it allows for participants to fully process the nature of the stimuli. However, as evident from this evidence synthesis, there are few studies that report on this timing, and this is indeed an area that future research should evaluate to determine the optimal interval for the different substance use disorders.

Our article is perhaps the first article that has reviewed the task paradigms that have been adopted in previously published studies, involving individuals with substance use disorders. We managed to systematically extract information, primarily from the methods section of each manuscript, to ascertain the details of the visual probe paradigms that were utilized. However, there were limitations in our current study. We were unable to access the full text of one of the published articles, as it was published in a Chinese Journal. We have also attempted to contact each of the authors for further details about the Visual Probe Task they have previously used but, to date, we have only managed to receive replies from a single author, who stated that all the details have already been cited in the methods section of the published manuscript.

4. Conclusions

Our article has reviewed all the visual probe paradigms that have been applied previously for addiction and substance research. While there are variations in the underlying paradigms, there are some commonalities as well. Future research examining attentional biases among individuals with substance use disorders should take into consideration the paradigms that are commonly used and evaluate the optimal stimulus and stimulus-onset asynchrony timings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z., D.S.S.F., and H.S.; data collation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, D.S.S.F. and H.S. All authors read and approved of the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding

M.Z. is supported by a grant under the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council (grant number NMRC/Fellowship/0048/2017) for PhD training. The funding source was not involved in any part of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any competing interests.

References

- Field, M.; Cox, W.M. Attentional bias in addictive behaviors: A review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 97, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberl, C.; Wiers, R.W.; Pawelczack, S.; Rinck, M.; Becker, E.S.; Lindenmeyer, J. Approach bias modification in alcohol dependence: Do clinical effects replicate and for whom does it work best? Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacy, A.W.; Wiers, R.W. Implicit cognition and addiction: A tool for explaining paradoxical behavior. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melvyn, Z.W.; Ying, J.; Wing, T.; Guo, S.; Fung, D.S.; Smith, H. Cognitive Biases in Cannabis, Opioid, and Stimulant Disorders: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 376. [Google Scholar]

- Vollstädt-Klein, S.; Loeber, S.; Richter, A.; Kirsch, M.; Bach, P.; von der Goltz, C.; Hermann, D.; Mann, K.; Kiefer, F. Validating incentive salience with functional magnetic resonance imaging: Association between mesolimbic cue reactivity and attentional bias in alcohol-dependent patients. Addict. Biol. 2012, 17, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, R.; Garavan, H. Neural mechanisms underlying drug-related cue distraction in active cocaine users. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2009, 93, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataya, A.F.; Adams, S.; Mullings, E.; Cooper, R.M.; Attwood, A.S.; Munafo, M.R. Internal reliability of measures of substance-related cognitive bias. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 121, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, M.; Christiansen, P. Commentary on, ‘Internal reliability of measures of substance-related cognitive bias’. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 124, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.M.; Viacava, K.R.; Bizarro, L. Attentional bias modification based on visual probe task: Methodological issues, results and clinical relevance. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2015, 37, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Christiansen, P.; Field, M. Failed attempts to improve the reliability of the alcohol visual probe task following empirical recommendations. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2018, 32, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, R.R.; Sofuoglu, M.; Brede, E.; Robinson, C.; Waters, A.J. Attentional bias in opioid users: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 191, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, E.L.; Howard, M.O. Opioid attentional bias and cue-elicited craving predict future risk of prescription opioid misuse among chronic pain patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 144, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, E.L.; Froeliger, B.E.; Passik, S.D.; Howard, M.O. Attentional bias for prescription opioid cues among opioid dependent chronic pain patients. J. Behav. Med. 2013, 36, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, M.; Wellington, C.E.; Mokrysz, C.; Freeman, T.P.; O’Ryan, D.; Curran, H.V. Attentional bias and treatment adherence in substitute-prescribed opiate users. Addict. Behav. 2015, 46, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankland, L.; Bradley, B.P.; Mogg, K. Time course of attentional bias to drug cues in opioid dependence. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016, 30, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yang, B.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Z. Eye Movement Evidence of Attentional Bias for Substance-Related Cues in Heroin Dependents on Methadone Maintenance Therapy. Subst. Use Misuse 2017, 52, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, N.; Morgan, C.J.; Battistella, S.; O’Ryan, D.; Davis, P.; Curran, H.V. Attentional bias, inhibitory control and acute stress in current and former opiate addicts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010, 109, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Froeliger, B.; Howard, M.O. Allostatic dysregulation of natural reward processing in prescription opioid misuse: Autonomic and attentional evidence. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 105, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubman, D.I.; Peters, L.A.; Mogg, K.; Bradley, B.P.; Deakin, J.F.W. Attentional bias for drug cues in opiate dependence. Psychol. Med. 2000, 30, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tull, M.T.; McDermott, M.J.; Gratz, K.L.; Coffey, S.F.; Lejuez, C.W. Cocaine-related attentional bias following trauma cue exposure among cocaine dependent in-patients with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Addiction 2011, 106, 1810–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, M.; Mogg, K.; Bradley, B.P. Cognitive bias and drug craving in recreational cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004, 74, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujanovic, A.A.; Wardle, M.C.; Liu, S.; Dias, N.R.; Lane, S.D. Attentional bias in adults with cannabis use disorders. J. Addict. Dis. 2016, 35, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Field, M. Cannabis ‘dependence’ and attentional bias for cannabis-related words. Behav. Pharmacol. 2005, 16, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C.; Field, M.; Atkinson, A.M.; Cole, J.C.; Goudie, A.J.; Sumnall, H.R. Effects of alcohol preload on attentional bias towards cocaine-related cues. Psychopharmacology 2010, 210, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bardeen, J.R.; Dixon-Gordon, L.K.; Tull, M.T.; Lyons, J.A.; Gratz, K.L. An investigation of the relationship between borderline personality disorder and cocaine-related attentional bias following trauma cue exposure: The moderating role of gender. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.R.; Wilcox, C.E.; Dodd, A.B.; Klimaj, S.D.; Dekonenko, C.J.; Claus, E.D.; Bogenschutz, M. The efficacy of attention bias modification therapy in cocaine use disorders. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2016, 42, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Cai, H.; Zhao, Q.; Han, Q.; Ma, E.; Zhao, G.; Peng, H. An ERP Study of Attentional Bias to Drug Cues in Heroin Dependence by Using Dot-Probe Task. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human Centered Computing, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 7–9 January 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 794–799. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).