Abstract

Objectives: This study analyzes the results of empirical studies on the impact of hospital competition (rivalry and market pressure) on the quality of care in European countries. Methods: A systematic review has been conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviewing and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, using the following online databases: PubMed, ScienceDirect, Wiley Online Library, and Google Scholar. The search protocol covers studies published in English between January 2015 and mid-April 2024. Results: Eight out of 14 eligible studies document significant positive associations, at least in the short term, between hospital competition and the quality of care measured through objective outcome indicators. Of the other six, one study demonstrates a negative relationship in a specific context. The findings of the remaining five studies are heterogeneous and context-dependent (two out of five) or suggest no discernible association between the two examined phenomena (three out of five). The respective contexts with positive, negative, or no statistically significant associations have been identified. Conclusions: The most essential impacts of competition on the quality of hospital care have been summarized, and avenues for future research and policy implications have been discussed.

1. Introduction

In accordance with economic theory, competition effectively mobilizes production []. Competitive markets create the necessity for manufacturers to constantly improve technologies and processes in a relentless pursuit to lower costs. New technologies catalyze competition by diffusing widely and quickly among manufacturers []. As a result, less successful competitors will be gradually driven out, leading to declining value-adjusted prices []. This theory generally holds true for industries, such as information technologies, mobile communications, and banking []. Therefore, it is believed that competition is efficient in addressing healthcare challenges [].

Nevertheless, the unique characteristics of healthcare markets complicate the application of traditional economic theory in assessing the impact of competition, given the absence of conditions for perfect competition [,]. Firstly, healthcare services are considered as differentiated products [,], as preferences and disease patterns vary based on region and scale [,]. Consequently, patients receive different healthcare services at different hospitals, even in a market-clearing scenario. This makes the healthcare market monopolistically competitive. Secondly, information asymmetry is prevalent in healthcare, potentially leading to market inefficiencies. Suppliers often possess more knowledge about diseases, treatments, and demand compared to patients, giving them a dominant position. Intensified competition among hospitals in such markets could trigger a cycle of escalating medical services, resulting in higher costs for patients and unnecessary utilization of services due to supplier-induced demand [,,,]. The role of competition in the healthcare market remains under-investigated [,].

Traditionally, healthcare systems have been heavily regulated by national governments with very few exceptions, such as the US. Nevertheless, pro-competitive reforms have been introduced in many countries since the beginning of the 21st century, which include, for example, the corporatization of public providers, prospective payment schemes, pay-for-performance schemes, patient choice of provider, and the entry of private providers []. For example, in 2000, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) changed the reimbursement system for outpatient care at Federally Qualified Health Centers to include a prospective payment system for Medicaid and Medicare in the US []. In addition, see a scoping review by Turner and Wright for details on the corporatization of public providers [].

Examples of national regulation include the following policy measures. In 2001, after the “patient choice” reform in Norway, patients were allowed to select any national health service (NHS) hospital across the whole country for non-acute treatments []. In 2002–2011, a series of changes in the market for NHS-funded hospital care were introduced in the UK with the intention of stimulating competition to improve quality and reduce waiting times []. In France, in 2004/2005, a payment reform where all hospitals are paid by fixed diagnosis-related group-based prices was introduced. This payment reform promoted benchmarking competition between public and private hospitals because hospital revenues were linked to patient volume []. In addition, since 2008/2009, minimum activity thresholds were used for regulating access to the cancer market []. In 2006, the healthcare system in the Netherlands underwent extensive reform when managed competition was introduced, “to reduce costs, increase the quality and accessibility of healthcare and, at the same time, to maintain an equitable healthcare system” [] (p. 5). In Germany, public reporting was implemented in 2008 for all acute care hospitals to foster fair competition for the best quality of care []. In many national healthcare markets, integrated care and competition have emerged simultaneously. Examples include the introduction of an integrated delivery system [] and managed care [] in the US under a framework of privatization and competition and the introduction of integrated care in quasi-market or regulated markets in the UK [,], Sweden, and Germany []. These reforms provide a basis for hospital competition, especially by quality of care.

This study addresses the research question: How does hospital competition affect the quality of care? Additional questions are: Which contexts are associated with positive and negative effects of hospital competition on the quality of care? What are the differences in these effects across different time spans? In which areas, e.g., composition of services, quality, price, costs, and for which types of medical care services, is competition stronger/weaker, and why?

2. Defining Key Terms

This review covers the following key concepts. The first concept is ‘competition’, and, in our context, ‘hospital competition’. Competition refers to choice of medical care providers, when the choice is made by payers or consumers of medical care []. In these situations, care providers have an opportunity to influence the results of this choice, and the results of the choice determine the amount of financial or other material resources received by providers from payers. There are six types of choice situations in which competition among healthcare providers might simultaneously occur []. The first group refers to the selection of healthcare providers by the payer of healthcare in the public health financing system. It includes (1a) administrative competition when the payer is a healthcare regulatory body to which providers are administratively subordinated; (1b) competition in the internal market when payers are healthcare authorities to which providers are not administratively subordinated, and (1c) competition in a quasi-market when the payer is (are) an insurer (or several insurers). The second group of choice situations refers to (2) patients’ choice of healthcare providers in the public health financing system. The third group refers to healthcare payer selection of healthcare providers in private healthcare financing systems. These situations include (3a) competition for patients in private healthcare systems when the payer is a voluntary health insurer, and (3b) competition for patients in the medical services market when the payers are patients. Another major category of hospital competition, which considers the supply side, is cost competition [].

Typically, researchers measure hospital competition using the following indicators: (market) concentration [], usually measured by the Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI) [,,,,], and the number of hospitals in the market [,,,]. In some studies, competition is proxied by physician density [], doctor-to-population ratio [], distance to other general practitioners [], the degree of perceived competition [], or even instrumented by, for example, the marginality of local English Parliamentary seats []. In their study, Wong et al. examined whether different hospital competition measures matter in empirical investigations of hospital behavior []. As most of the measures are highly correlated, they cautioned against using arbitrarily selected competition measures if the magnitude of the estimates is important.

Hospitals can be classified by size (small hospitals with fewer than 100 beds, medium hospitals with 100 to 499 beds, large hospitals with at least 500 beds), by duration of care provided (acute vs. long-term care hospitals), by ownership type (for-profit, not-for-profit, government-owned hospitals), by location (rural vs. urban hospitals), by university affiliation (academic/university/teaching vs. general/non-teaching hospitals), by funding source (federal, state/region, or local hospitals), etc. []. These characteristics affect supply-side care and hospital competitive strategies, as clarified later in this section.

The second concept is ‘quality of care’. It includes the following categories: input quality, process quality, and output quality []. Researchers usually assess quality of care using objective indicators including, but not limited to, the number of tertiary hospitals, the number of hospital health personnel per 1000 population, and the private share of hospital beds []. Objective output quality indicators include: mortality following acute myocardial infarction (AMI mortality) [], pneumonia mortality [], hip fracture mortality and stroke mortality [], risk-adjusted stroke mortality [], all-cause mortality of emergency patients and hospital readmission rates [], emergency readmissions (for hip and knee replacement), and emergency readmissions (for coronary bypass) [], the mean number of outpatient revisits [], (a) the risk of in-hospital death and (b) ambulatory care sensitive condition hospitalization (for patients with hypertension) []. Notably, Wadhera et al. consider patient revisit numbers as an important measure of both process care quality and output care quality []. Similarly, Martsolf et al. argue that patients’ revisits indicate the healthcare needs that were not met during the initial visit or follow-up visit, and a high number of revisits exacerbates the resource constraints of healthcare institutions []. Additional objective output quality indicators include length of stay [], pre-operative length of stay (for hip and knee replacement patients) [], inpatient complications [,,], wait times [], and the number of violations and penalties []. In a few studies, subjective output quality indicators, such as patient-reported health outcomes (PROMs) (before and after the non-emergency surgery) are utilized [,]. Proxies of ‘process quality’ at hospital level include the likelihood of providing innovative surgical procedures [] and aggregated indices calculated in accordance with a system of quality indicators from the ‘Dutch Healthcare Transparency Program’ []. In this systematic review, we focus on non-price competition and all dimensions of care quality.

Previous research identified four major factors that may moderate the relationship between hospital competition and care quality (cf. Berta et al.) []: the institutional settings of hospital care, i.e., market supply side [,,,], the degree of information on hospital care quality [,], the degree of patient freedom of choice [,,,,,], and hospitals’ competitive strategies [,,].

3. Overview of the Relevant Reviews

Supplementary Table S1 summarizes the main characteristics of 12 recently published systematic reviews. These characteristics include the type of review, focus, countries covered, sample period, the number of studies reviewed, databases searched, and main results. These reviews cover evidence coming mainly from high-income countries.

Ghiasi et al. reviewed the impact of hospital competition on the strategies and outcomes of US hospitals in 1996–2016 exploring 143 relationships from 65 studies. Their results concerning statistical associations are mixed: “almost half of them found [a] significant relationship between hospital competition and various outcome measures (35 positive and 38 negative), whereas the remaining 70 (or 49%) did not find any significant association” [] (p. 23).

Shen et al. focused on the potential implications to care for senior patients in their systematic review and meta-analysis, which covered the studies published between 2003 and 2013. According to their results, hospital competition was associated with a slight, but not statistically significant, increase in AMI mortality rates in Australia, the Netherlands, the UK, and the US. They conclude that, “older patients with complex care needs may be at risk for poorer quality of care related to hospital competition” [] (p. 263).

Jamalabadi et al. provided a synthesis of research published between 1990 and March 2019 concerning the relationship between hospital cost/price and the quality of care in 15 OECD countries, which demonstrated no general relationship [].

Jiang et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published before September 2019 to assess the impact of hospital-market competition on unplanned readmission in Australia, South Korea, Taiwan, and the US. The pooled results of three heterogeneous studies demonstrated that it was uncertain whether hospital competition reduces readmission, while inconsistent results were found in the remaining six eligible studies [].

Mariani et al. conducted a systematic review of studies published before January 2020 to assess the impact of hospital mergers on healthcare quality measures in Czechia, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, the UK, and the US. They documented “inconsistent findings and few statistically significant results” [] (p. 191). In addition, the analyzed measures demonstrated “an insufficient strength of evidence to achieve conclusive results” [] (p. 191). Nevertheless, their results identified a tendency for a decrease in the number of beds, hospital personnel, and inpatient admissions, and an increase in mortality and the readmission rate for AMI and stroke [] (p. 191). Similarly, Mills et al. [], Mullens et al. [], and Stansberry et al. reviewed the impact of hospital closures on rural communities in the US. Predictably, “as hospitals close, travel times increase cumulatively, reduce access to care, and, in turn, increase the risks associated with time-sensitive health events. [...] The loss of rural hospitals may also increase mortality and morbidity in vulnerable communities and the overall health system through interrelated effects on bystander hospitals, the availability of healthcare providers, individual and community socioeconomic status, and community well-being” [] (p. 13).

Reviews by Zander et al. [], Ahmed et al. [], Bradow et al. [], and Yang et al. [] are less relevant to our research question as they focus on competition among physicians, general practitioners, maternity units, and nursing homes, respectively (rather than hospital competition per se). Thus, there is a research gap resulting from a lack of empirical studies published within the last 10 years on the impact of hospital competition on quality of care in Europe.

4. Methods and Data

Following the PRISMA reporting guidelines [], we employed a systematic review to identify and classify all the literature that is related to our research questions. The protocol of this systematic review was published in the Open Science Framework (OSF) with the following digital object identifier (DOI): 10.17605/OSF.IO/AW3XJ. The databases used in the study are ScienceDirect, PubMed, Wiley Online Library, and Google Scholar. The search used the following key terms and/or MeSH terms: {“competition” OR “competitiveness” OR “market pressure” OR “rivalry” OR “physician density” OR “physician supply” OR “merger” OR “closure”} AND {“care”} AND {“hospital” OR “health facility” OR “medical organization”} AND {“quality of care” OR “hospital performance”} AND {“regression” OR “correlation”}. We focused our search on articles in English, published between January 2015 and mid-April 2024.

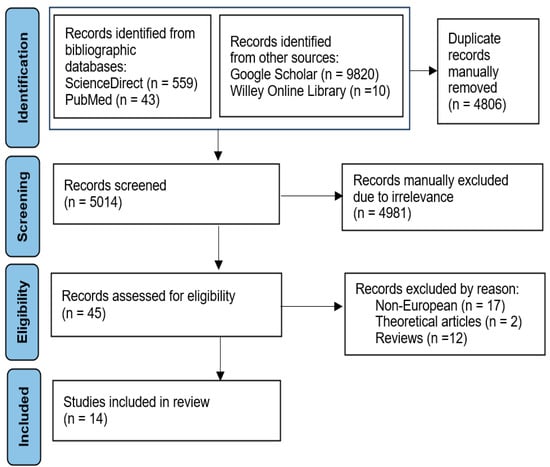

We included publications if they were peer reviewed, they included empirical data, they had extractable data related to hospital or medical care, and they could be classified as either “research article” or “original research”. We excluded publications of the following types: expert opinion, single or multiple case studies, conceptual theoretical study, editorial, commentary, letter to the editor, short communication, study protocol, and policy paper. We also excluded studies based on qualitative data, data from laboratory experiments, or data from outside of Europe. The PRISMA diagram demonstrates details of our search for eligible studies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selecting articles for review.

The literature was reviewed independently by two researchers (M.J. and Y.T.) using the criteria outlined above, and queries on the suitability of individual studies were discussed with their colleagues (V.G. and E.M). Reference lists of selected publications were screened for any further potentially relevant resources. AMSTAR Checklist, a 16-question measurement tool to assess systematic reviews, was used for quality assessment of the studies. In addition, insights on search procedure from a recent study on hospital efficiency [] guided our selection process.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

The initial search returned 9820, 559, 43, and 10 papers in Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Wiley Online Library, respectively. The removal of duplicates yielded 5014 articles. The selected papers were screened by title and subsequently screened on their abstract or full text. In total, 14 studies were selected for review based on the criteria listed above, covering France (2), Germany (1), Italy (3), the Netherlands (2), Norway (1), Sweden (2), and the UK (3). In eight articles, HHI is used among hospital competition measures. Objective output indicators dominate among the indicators of care quality (in 11 articles), with two instances of objective process indicators, and one study with subjective output indicators. (There are instances of simultaneous use of two types of indicators). In 13 studies, parametric methods, including difference-in-differences design (5) and multilevel models (5) are employed, while one study utilizes non-parametric tests only. Table 1 summarizes the articles, which were included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of empirical research on the effects of competition on quality of care among hospitals.

5.2. The Effects of Hospital Competition on Care Quality in Europe

The first group of results is based on applying econometric models with relatively standard sets of proxy variables for hospital competition and care quality to the data from the respective counties.

5.2.1. Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Italy

#1. A study by Strumann et al. considered the relationship between the examined phenomena through a lens of public reporting (PR) on healthcare quality as PR aimed to steer patients towards high-quality providers and promote fair competition based on quality []. The researchers focused on the impact of the initial public release of performance data in Germany in 2008. Given the intricate nature of stroke patient care, overall hospital quality was proxied by the 30-day risk-adjusted mortality rate for stroke treatment. Market competitiveness was computed using predicted market shares derived solely from exogenous factors to allow for a causal understanding of the impact of the reform. The study revealed a homogenous positive relationship between competition and care quality. The observed effect was mostly determined by not-for-profit hospitals specializing in a narrow range of services and for-profit hospitals offering a medium range of services. In addition, the results suggested that non-specialized hospitals, which play a crucial role for local emergency and acute care, might not be systematically able to increase their quality in response to the competitive pressure of PR. In contrast, the highest-quality improvement effects were attributed to medium private for-profit and highly specialized not-for-profit hospitals. This difference might be explained by the distinct necessities and opportunities of the various hospital types to enhance their quality. The different ownership types and degrees of specialization potentially determine the hospitals’ flexibility and resources (allocated to maintain their competitive position).

Despite this homogenous effect, several structural reasons potentially limit quality competition in Germany (although legally free patient choice of hospitals exists). They include: (a) limited patient mobility; (b) patient “path-dependence” (i.e., a fact that patients often choose hospitals that they have previously attended or their outpatient physicians have recommended); (c) patient choice can be exercised if they have an option among different hospitals offering the necessary medical service. In general, the findings demonstrate the significance of outcome transparency in improving hospital quality competition.

#2. Or et al. analyzed shifts in market competitiveness and treatment patterns within the realm of breast cancer surgeries done in 2005 and 2012 []. They focused on the adoption of technology as an indicator of procedural excellence, investigating the probability of providing immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) post mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). Employing a competition index derived from a multinomial logit model of hospital selection, which mitigates endogeneity bias, they assessed its influence on the likelihood of administering IBR and SLNB through multilevel models that considered both observable patient and hospital attributes. The probability of undergoing these interventions is notably elevated in hospitals situated in more competitive markets. Nevertheless, hospital caseloads continue to serve as a significant metric of quality, thereby suggesting that the advantages of competition are contingent on the evaluations of caseload impact on treatment protocols. In France, the implementation of a centralization policy, with specified minimum activity thresholds, has played a role in enhancing the treatment of breast cancer during the observed period. The results revealed that markets bordering on monopolistic structure do not foster advancements or excellence in cancer therapy. However, excessively competitive markets characterized by numerous hospitals with minimal activity levels also present issues as the quality of hospital services is positively correlated with the number of patients.

#3. Goro et al. conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study from 2015 to 2019 utilizing data from a National Health Database []. Patients operated on for colorectal cancer in hospitals in mainland France were included. The results demonstrated that increasing hospital competition independently decreased the 30-day mortality rate after colorectal cancer surgery. Other factors significantly associated with mortality included age, gender, patient comorbidity index, malnutrition, neo-adjuvant treatment, the emergency admission, type of surgical procedures, and hospital caseload. The findings were robust when alternative competition measures were used. However, future research would benefit from controlling for surgeon and hospital quality to avoid a potential omitted variable bias.

#4. Croes et al. examined the correlation between quality assessments for three specific diagnosis groups and hospital market share []. The analysis focused on assessing the effect of competition on quality within a context of deregulated pricing. The investigation leveraged distinct pricing and output data pertaining to the three diagnosis groups (cataract, adenoid and tonsil, and bladder tumor) provided by Dutch hospitals between 2008 and 2011. Quality metrics associated with these diagnosis groups were also utilized. For cataract and bladder tumor, the relationship between hospital competition and quality scores was significant and robust. For adenoid and tonsils, no significant associations were found. One possible explanation is that the patient group for adenoid and tonsil is less complex: It is mainly children under 11. This type of patient has fewer additional diagnoses compared to patients with, for example, bladder tumor. Endogeneity concerns prevent price from being included as an independent variable in the quality indicator models, suggesting the absence of the relationship between price and quality scores: hospitals with higher-quality scores do not have higher prices. Summing up, the findings indicated an inverse relationship between market share and quality assessment for two out of the three diagnosis categories, suggesting that hospitals operating in competitive environments exhibited superior quality assessments.

#5. Van der Schors et al. utilized data from Cancer Registry in the Netherlands to examine the impact of hospital volume and competition on outcomes for invasive breast cancer (IBC) surgery patients between 2004 and 2014 []. According to the results, treatment types, patient, and tumor characteristics mainly explained variations in outcomes. Hospital volume and competition did not significantly affect surgical margins or re-excision rates after adjusting for variables. Survival was slightly higher for patients in hospitals with higher annual surgery volumes and more competitors nearby. However, the effect of hospital competition on survival did not remain consistent after adjusting the proxy. Hospital volume and regional competition play a limited role in explaining variations in IBC surgery outcomes in Dutch hospitals. The study suggested two theoretical explanations for the absence of a robust relationship between hospital competition and care quality. First, in the Netherlands, “the role of competition among hospitals in breast cancer care is limited through the rare use of selective contracting by health purchasers” [] (p.11). Competition in this market segment is not strengthened by active patient choice: most breast cancer patients agree to be referred to the nearest hospital by their general practitioner. Second, due to the potential co-existence of competition and collaboration in health systems, “the competition-effect might be mitigated by an unobserved collaboration-effect” [] (p.11).

#6. Lisi et al. explored the geographical extent of the impact of hospital competition on quality, utilizing data from the Lombardy region of Italy that encompasses over 207,000 patients from 2008 to 2014 []. The researchers introduced an economic framework that took into account not only local forms of quality competition among hospitals, but also global aspects. Global competition arises from periodic releases of hospital performance rankings. Within this framework, they deduced the hospital reaction functions and subsequently characterized the interdependence among the quality of hospitals. This might be explained by the fact that hospital managers’ decisions on care quality are also affected by hospital outcomes from outside their local market. In line with their theoretical predictions, the empirical results revealed a significant positive degree of short- and long-term dependence. In addition, these findings indicated the presence of local and global competition dynamics among hospitals. In general, while the findings were in line with other studies (e.g., Bloom et al. []; Cooper et al. []), they also suggested that healthcare systems could benefit not only from more competitive local hospital markets, but also from making their institutional environment more competitive for hospital management.

#7. A study by Guida et al. quantified the level of competition among Italian healthcare providers and assessed the potential correlation with hospital mortality rates []. The sample comprised individuals discharged in 2015 after CHF or AMI, as well as those discharged in 2014 and 2015 following cardiac surgery. The findings indicated that competition indicators exhibited variability across different medical conditions and were notably sensitive to the methodology employed for defining the geographical market boundaries. Notably, neither the quantity of hospitals nor HHI demonstrated significant correlations with outcomes for CHF cases. The hospital competition measures fluctuated depending on the definition of the local market, leading to varying mortality correlations for different medical conditions. The inverse correlations between competition measures risk-adjusted mortality ratios (RAMRs) suggested the possible role of case volumes on outcomes. The study documented that “[a] hospital’s RAMR for valve surgery increased in more competitive areas at the analyses for fixed cases volume and fixed number of hospitals” [] (p. 601). This inverse relation was mainly explained by the possible positive effect of high volumes. Mortality and hospital volume, being proxies for care quality, might drive patient choice of cardiac surgery center and, consequently, strengthen the relationship between these indicators. Larger volumes were possible in areas with lower competition. Consequently, high-volume hospitals were more likely to have high-volume surgeons and demonstrate better outcomes. Patients tended to choose better hospitals, as they are sensitive to care quality. In contrast to valve surgery, lower RAMRs in more competitive areas of fixed size was observed. The latter findings were similar to those observed in the English NHS: competition can raise the quality of CABG surgery [].

#8. Berta et al. explored the influence of competition on adverse health outcomes in hospitals within an environment where information on hospital quality is not publicly disclosed []. The study utilized data from patients admitted to hospitals in the Lombardy region of Italy, where annual risk-adjusted hospital rankings are exclusively available to hospital administrators. Consequently, patients might base their hospital selection on factors such as proximity, local network recommendations, and general practitioner referrals. Through the estimation of patient-predicted choice probabilities, a series of competition indices were constructed to evaluate their impact on a composite index encompassing mortality and readmission rates as indicators of hospital quality. The results suggested no discernible link between adverse events and hospital competition, potentially attributed to information asymmetry (i.e., a lack of publicly available information on the quality of hospitals) and the complexities associated with developing reliable health quality indicators.

Thus, the results from Germany and partly from the Netherlands suggested the existence of a positive relationship between hospital competition and care quality. The evidence from Italy was contradictory (positive only; positive and negative; and no associations), while the findings from France was inconclusive with some evidence of a positive relationship.

5.2.2. Scandinavia

#9. Brekke et al. examined the effects of introducing non-price competition to hospitals within an NHS setting, through the implementation of patient choice reform in Norway in 2001 []. This reform enabled the application of a difference-in-differences approach due to the plausibly exogenous (geographical) variations in the pre-reform market structure. By utilizing comprehensive administrative data encompassing all hospital admissions from 1998 to 2005, the study employed models with fixed effects for hospitals and treatments/DRG, focusing solely on emergency admissions to mitigate potential patient-selection biases. The findings indicated that hospitals in more competitive regions experienced a notable decrease in AMI mortality rates (although it is sensitive to alternative competition measures), while observing no impact on stroke mortality. Additionally, exposure to competition was associated with lower all-cause mortality rates, reduced lengths of hospital stay, and increased readmissions, albeit with minor effects. Interestingly, higher DRG prices reinforced the identified effects of competition, which appeared to reduce wait times and increase admissions. Although these findings were in line with the results from the UK (see e.g., Cooper et al. [] and Gaynor et al. []), interpretation should be done with caution as elective treatments were included in the analysis, while a full welfare analysis was not conducted.

#10. A study by Goude et al. examined the effect of a pro-competitive reform that was implemented in 2009, specifically targeting elective hip replacement surgeries in Stockholm, Sweden []. The impact of this reform on the quality of hip replacement surgeries was assessed using various patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) related to health improvement, pain alleviation, and patient satisfaction, 1 and 6 years after the surgery. The data encompassed elective primary total hip replacements conducted from 2008 to 2012. The adoption of entropy balancing mitigates divergences in observable characteristics and to harmonizes all covariates across the treatment groups. However, no statistically significant effects of the reform on any of the targeted PROMs at the 1- and 6-year follow-ups were identified. Notably, the introduction of competition and bundled payment schemes did not yield any discernible improvements in the quality of hip replacement surgeries, proxied by the post-surgery PROMs. Within the bundled payment model (the spine surgery program), two types of outcomes with differences in the strength of financial incentives were considered that potentially explain the lack of hospital competition effects on PROMs. First, providers are responsible for covering healthcare costs related to the hip replacement surgery, including complications such as infection and revision surgery within 2 years after surgery. Second, the performance payment, which is partly based on PROMs, is only a small percentage of the bundled payment in magnitude. Even if both outcomes are observable, healthcare providers have more financial incentives to avoid negative outcomes, e.g., complications, rather than to focus on PROMs. The findings somewhat contradicted the results of Skellern et al. [] related to the pro-competition reform in the English NHS in 2006, who document lowered care quality measured by PROMs of health gain for hip and knee replacement. This discrepancy was explained by differences in the setting (e.g., the level of competition and design of economic incentives, and sample) and methodology.

#11. Avdic investigated how the geographical proximity to an emergency hospital affected the likelihood of surviving an AMI, while considering health-related spatial sorting and data constraints related to out-of-hospital mortality in Sweden []. Leveraging policy-induced shifts in hospital distances due to emergency hospital closures and extensive mortality data spanning 2 decades, the results revealed a substantial decrease in the likelihood of surviving an AMI as the residential distance from a hospital increases in the year following a closure. Nonetheless, this effect diminished in subsequent years, indicating a swift patient adaptation to the altered circumstances. The latter finding might be explained by compensatory strategies adopted by prospective patients and the healthcare administration to accommodate any distance effects following hospital closures. For example, patients with poor health who experienced reduced access to emergency healthcare might decide to move closer to the new home hospital, while healthcare authorities might ex post invest more in emergency healthcare. In addition, distance changes are exogenous only just after the closure because patients, and healthcare authorities, can react and adapt to the changes over time. Finally, the temporary increase in AMI mortality caused by hospital closures might be compensated for by productivity gains from the subsequent consolidation of inpatient care at the remaining hospitals.

Thus, the evidence from Norway and Sweden based on objective quality indicators suggested the existence of a significant positive association between hospital competition and care quality. In contrast, the findings from Sweden did not reveal any effects, when subjective PROMs were used to measure care quality with respect to hip replacement surgeries, which are less dangerous compared to AMI.

5.2.3. The United Kingdom

#12. Moscelli et al. examined the impact of a policy reform that relaxed constraints on patient selection of hospitals on the quality of three high-volume non-emergency medical treatments in the UK []. The quasi difference-in-differences strategy and integrate control functions that allow for the possibility of patient self-selection into providers, which might be correlated with unobservable morbidity factors. The sample comprised patients funded by the NHS who received treatment in NHS-affiliated hospitals. The analysis revealed that public hospitals operating in environments with heightened competition experienced a decline in quality, prolonged wait times, and reduced lengths of stay specifically in the context of hip and knee replacement surgeries. This phenomenon was attributed to regulated pricing mechanisms that resulted in larger financial losses for these procedures compared to coronary artery bypass grafts, where no discernible effects were observed. Importantly, the findings exhibited robustness across different estimation methods and competition metrics, even when accounting for the entry of private healthcare providers into the market. The results for elective care were also compatible with those for emergency care, which use a similar identification strategy, although they found that the choice reform reduced mortality for AMI [,] and hip fracture [] for hospitals with more competitors. If emergency mortality was used as a reliable indicator of overall hospital quality by patients undergoing elective treatments, then patient choice could increase emergency quality and reduce elective care quality as the result of diverted effort. In addition, the reductions in mortality were likely to have generated health benefits that were larger than the health losses for patients undergoing elective treatments as measured by higher emergency readmissions for hip and knee replacement patients. The observed reductions in quality for knee and hip replacement surgeries do not mean that the 2006 choice reform is welfare reducing overall. Patients undergoing elective procedures might benefit from an opportunity to switch to previously unobtainable providers of better quality.

#13. The primary objective of the national longitudinal study conducted by Aggarwal et al. was to analyze the association between patient choice and hospital competition in relation to post-operative outcomes following prostate cancer surgery []. The study encompassed the entire male population who underwent prostate cancer surgery in the UK from 2008 to 2011. The study assessed the impact of a radical prostatectomy center’s placement in a competitive setting and its effectiveness in attracting patients from other healthcare facilities on three patient-centered metrics. The findings indicated that, even after adjusting for individual patient attributes, males who underwent surgery at centers in more intensely competitive environments exhibited a reduced likelihood of experiencing a 30-day emergency readmission, regardless of the nature or quantity of procedures conducted at each respective center. Furthermore, individuals receiving care at centers that attract patients from other hospitals were less likely to have a length of hospital stay more than 3 days. The findings suggested that hospital competition contributes positively to short-term post-operative outcomes following prostate cancer surgery. The association between being a successful competitor and a reduction in hospital length of stay might be explained by two main factors. First, these specialized medical centers are more likely to be higher-volume centers compared with unsuccessful rivals. Second, during the period of analysis, successful competitors adopted robot-assisted radical prostatectomy more rapidly, which was likely to determine better outcomes.

#14. Moscelli et al. analyzed the consequences of relaxing constraints on patient choice of hospitals within the NHS in 2006, particularly focusing on its influence on mortality rates []. The research utilized a comprehensive data set spanning from 2002 to 2010, encompassing three critical emergency conditions associated with high mortality risks: AMI, hip fracture, and stroke. Given the varying mortality risks associated with different sub-diagnoses of AMI and stroke, the analysis incorporated indicators for sub-diagnoses within the covariates. In addition, the study accounted for potential variations in the impact of covariates on mortality rates before and after the 2006 choice reform. The findings revealed that the choice reform resulted in a slight reduction of mortality risk for patients with hip fractures. However, the reform exhibited statistically insignificant negative effects on mortality rates for patients with AMI and stroke. The study highlighted heterogeneous effects across different sub-diagnoses of AMI and stroke. The decline in mortality rates for hip fracture cases was more pronounced among more deprived patients. These findings were in line with the results of the previous studies on this reform [,] and highlighted the nuanced nature of pro-competition policies, emphasizing the importance of considering the interplay between patient sample and institutional setting. Theoretical models offered additional explanations for the difference in the results across type of condition. They demonstrated that higher competition and patient choice could either increase or decrease care quality, depending on the characteristics of supply and demand, the hospital objectives, and the level of price regulation.

Thus, the results from the UK are heterogeneous and contradictory: in two studies, positive and no relation between competition and objective care quality indicators are documented, while the most recent article argues in favor of a negative association between the examined phenomena in certain contexts.

Summing up, eight out of the 14 reviewed studies documented significant positive associations, at least in the short term, between hospital competition and quality of care (measured through objective outcome indicators). Of the other six, one study demonstrated a negative relationship in a specific context. The findings of the remaining five studies were heterogeneous and context-dependent (two) or suggested no discernible association between the two examined phenomena (three). The results should be treated with caution as our sample is small, and the measures of competition and care quality vary among these studies.

The following contexts were associated with a positive relationship between hospital competition and quality of care: stroke in Germany, in 2006 and 2010; colorectal cancer in a hospital in mainland France between 2015 and 2019; breast cancer treatment in France between 2005 and 2012; adenoid and tonsils, bladder tumor, and cataract in the Netherlands between 2008 and 2011; ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, hip fracture, hip replacement, and knee replacement in Lombardy (Italy) between 2008 and 2014; AMI, stroke, and all-cause mortality in Norway between 1998 and 2005; AMI in Sweden between 1990 and 2010; and prostate cancer surgery in the UK between 2008 and 2011; in an area with a fixed radius of 100–150 km, after isolated-coronary artery bypass graft procedures in Italy in 2015; and AMI, stroke, and hip fracture in the UK between 2002 and 2010. In contrast, a negative association was observed in the following contexts: hip replacement, knee replacement, and coronary artery bypass grafts in the UK between 2002 and 2011; and after AMI and valve surgery in areas identified by the variable-radius method in Italy in 2015. No statistically significant associations were found in the following contexts: invasive breast cancer in the Netherlands between 2004 and 2014; cardiac surgery, cardiology, and general medicine in Lombardy (Italy) in 2012; hip replacements in Sweden between 2008 and 2012; chronic heart failure in Italy in 2015; and AMI and stroke in the UK between 2002 and 2010.

6. Discussion

To begin with, the relatively low number of eligible articles does not allow any statistical assessments regarding the examined effect of hospital competition on care quality to be made. A formal meta-analysis is hindered by the overrepresentation of studies from Italy and the UK and by the heterogeneity in the methods used in the studies. Second, identified contexts, which are associated with positive, negative, heterogeneous, or no associations between hospital competition and care quality, do not reveal the reasons behind these relationships. Third, our results cannot be directly compared with the results of previous studies as they differ in several major characteristics.

Brekke et al. report that there is “a lack of rigorous empirical evidence on the causal effects of exposing health care providers to competition, especially from outside the US and the UK, and the existing evidence on the impact of competition is generally mixed” [] (p. 2). This review provides new evidence from European countries documenting instances of conflicting results in within- and between-country dimensions.

In general, the findings of earlier studies from Germany [,], the Netherlands [,,], and Russian-speaking countries [] are in line with our results. For example, Sundmacher and Busse document that, “better accessibility or quality of care might have linked increased physician density with improved health outcomes” [] (p. 60). Jürges and Pohl found weak and insignificant effects of physician density on care quality measured as the degree of adherence to medical guidelines []. Bijlsma, Koning, and Shestalova demonstrated that Dutch “hospitals facing more competition organize diagnostic processes more efficiently” [] (p. 121). Ikkersheim and Koolman provided evidence that, “hospitals that faced more competition from geographically close competitors showed a more pronounced improvement [of Consumer Quality Index scores]” [] (p. 1). Heijink, Mosca, and Westert found “limited between-hospital variation in quality and there was no clear-cut relation between prices and quality” [] (p. 142).

Similarly to the results of our review, evidence of previous studies from the UK is mixed. Cookson, Laudicella, and Donni found a negative association between market competition and elective admissions in deprived areas: “The effect of pro-competition reform was to reduce this negative association slightly, suggesting that competition did not undermine equity” [] (p. 410). Cooper et al. documented that “after the reforms were implemented, mortality fell (i.e., quality improved) for patients living in more competitive markets” [] (p. F228). Propper, Burgess, and Green report that, “the relationship between competition and quality of care appears to be negative. However, the estimated impact of competition is small” [] (p. 1247).

The results of empirical studies from Africa and Asia, which utilize objective output quality indicators, are fragmentary and inconclusive, suggesting a positive association for hypertension patients in Ghana [] and for participants with haemorrhoids in South Korea [,], a negative association for pneumonia patients in China [], a negligible negative effect for stroke patients in Taiwan [], and an insignificant correlation with AMI in-hospital mortality in China []. A rapidly rising number of large Chinese hospitals with a capacity of more than 2000 beds [] might explain recently documented heterogeneous effects of hospital competition on inpatient quality in this country [].

In general, according to theoretical predictions, the following factors might explain the variability in the relationship between hospital competition and care quality: the institutional settings of hospital care [,,,], the degree of information on hospital care quality [,], the degree of patient freedom of choice [,,,,,], and hospitals’ competitive strategies [,,].

In addition, our results suggest that there are countries, such as France, Germany, and Norway, where only one type of relationship (positive) between hospital competition and care quality is observed regardless of the context. Therefore, it might be hypothesized that healthcare systems in which patients are free to choose their provider (France, Germany) and where hospitals are very heterogeneous in terms of type and the range of services (France, Germany) are likely to experience positive effects of hospital competition on quality of care. The same might be true for systems with universal public health insurance with 95% to 100% of the hospital expenditure covered by taxes (France, Norway).

Finally, theoretical predictions suggest the following. “[…] Quality levels seem to be highly dependent on the market structures that are in place. Hospitals providing comparable health services may vary in the level of price-quality provided. [...] In price-regulated markets, quality is the only dimension on which one can compete. In this setting, quality levels depend on whether price-cost margins are positive or negative (Gaynor and Town, 2011). In non-price-regulated markets, where providers are able to determine price and quality level, quality levels depend on elasticities of demand for price and quality. If quality information is not transparent, competition will focus on the price dimension (Propper et al., 2004)” [] (p. 7). In countries where hospitals and insurers bargain with each other (e.g., The Netherlands), the bargaining framework introduced by Gaynor and Town is the most useful theoretical model for analyzing the relation between competition and quality [].

7. Conclusions

More than half of the analyzed studies document significant positive association, at least in the short term, between hospital competition and the quality of care. The findings of the remaining six studies are heterogeneous and context-dependent or suggest no identifiable association between the two examined phenomena. Recall that the observed contradictions with the results of previous studies are explained by differences in institutional settings (for example, the level of competition and/or the design of economic incentives), samples, and methods.

Policymakers should understand that regulatory impact assessment (RIA) is necessary before a pro-competitive policy intervention to get a clear vision of its benefits and drawbacks for all stakeholders. At country level, the requirements to conduct RIA varies. For instance, in the UK, impact assessments are compulsory for all new policy initiatives and interventions, both regulatory and non-regulatory []. Yet, there is a room for improvement in RIA in Europe because only Austria, Estonia, France, Italy, Poland, and the UK have strong ex ante requirements in place to ensure that achievement of the regulation’s goals are assessed []. Furthermore, evidence-based policymaking can be useful for performing a periodic assessment of outcomes and processes and for adopting the appropriate corrective measures, if necessary []. In addition, enhancing service transparency can stimulate improvements in care quality. In Germany, for example, several websites, such as Weisse-Liste.de, report structural information on inpatient numbers, diagnoses, procedures, and risk-adjusted quality indicators in a publicly accessible and user-friendly manner, imposing potential pressure on competing hospitals []. Similar websites exist in almost every European country, although the extent of available information on hospital quality varies significantly among countries. To avoid cost-cutting decisions by hospital management in response to excessive competition, a balance between pro-competitive policy initiatives and regulation is essential for optimal healthcare outcomes.

We see the following directions for future research to overcome the limitations of our study. First, although quality indicators published for emergency treatments are considered as good clinical quality markers [] (p. 10), similar research with the simultaneous use of alternative quality indicators which cover multiple dimensions would shed light on the relationship between hospital competition and quality of care. Second, inconclusive findings might be “due to the use of different methodologies, hospital competition measures, and hospital quality measures” [] (p. 263). In this respect, testing alternative measures, such as the number of competitors per distance or per region (for local and global competition, respectively), geographical or time distance from the home of a patient and a hospital, along with traditional HHI, would be beneficial in shedding more light on the examined relationship as potentially more robust results might be obtained. Combining these two directions would be the most insightful, methodologically and practically. Third, further research on the impact of competition in different types of specialized care is necessary to identify the nuances of competition effects in this sector. Fourth, a meta-analysis could provide robust quantitative evidence when more data become available. Finally, relevant evidence from countries of the Global South [] would uncover the specific effects of competition on quality of care in this region.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12222218/s1, Table S1: Summary of reviews on the effects of competition among healthcare facilities on quality of care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, supervision, project administration, Y.T.; writing—review and editing, V.G., E.M. and M.J.; funding acquisition, Y.T. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article is an output of a research project implemented as part of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The search results are available at the following hyperlinks: Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Wiley Online Library.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Bank Group. World Bank Group. World Development Report 1991: The Challenge of Development (English). In World Development Report; World Development Indicators: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/888891468322730000/World-development-report-1991-the-challenge-of-development (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Porter, M.E.; Teisberg, E.O. Redefining competition in health care. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 64–77. Available online: https://hbr.org/2004/06/redefining-competition-in-health-care (accessed on 5 March 2024). [PubMed]

- Porter, M. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Teisberg, E.O. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grand, J.; Propper, C.; Robinson, R.V. Economics of Social Problems; Springer: London, UK, 1992; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-349-21930-8 (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Dranove, D. Health care markets, regulators, and certifiers. In Handbook of Health Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 639–690. [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor, M.; Town, R.J. Competition in health care markets. In Handbook of Health Economics; Pauly, M.V., McGuire, T.G., Barros, P.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 499–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.C.; Luft, H.S. The impact of hospital market structure on patient volume, average length of stay, and the cost of care. J. Health Econ. 1985, 4, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaynor, M.; Vogt, W.B. Antitrust and competition in health care markets. In Handbook of Health Economics; Culyer, A.J., Newhouse, J.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 1405–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, M.A. Consumer information, equilibrium industry price, and the number of sellers. Bell J. Econ. 1979, 10, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamater, P.L.; Messina, J.P.; Grady, S.C.; WinklerPrins, V.; Shortridge, A.M. Do more hospital beds lead to higher hospitalization rates? A spatial examination of Roemer’s law. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, H.S.; Robinson, J.C.; Garnick, D.W.; Maerki, S.C.; McPhee, S.J. The role of specialized clinical services in competition among hospitals. Inquiry 1986, 23, 83–94. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/29771762 (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Ikegami, K.; Onishi, K.; Wakamori, N. Competition-driven physician-induced demand. J. Health Econ. 2021, 79, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Qin, X.; Li, Q.; Messina, J.P.; Delamater, P.L. Does hospital competition improve health care delivery in China? China Econ. Rev. 2015, 33, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekke, K.R.; Canta, C.; Siciliani, L.; Straume, O.R. Hospital competition in a national health service: Evidence from a patient choice reform. J. Health Econ. 2021, 79, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Overview Prospective Payment Systems. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/prospective-payment-systems?redirect=/prospmedicarefeesvcpmtgen/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Turner, S.; Wright, J.S. The corporatization of healthcare organizations internationally: A scoping review of processes, impacts, and mediators. Public Adm. 2022, 100, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscelli, G.; Gravelle, H.; Siciliani, L. Hospital competition and quality for non-emergency patients in the English NHS. RAND J. Econ. 2021, 52, 382–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranabhat, C.L.; Jakovljevic, M.; Dhimal, M.; Kim, C.B. Structural factors responsible for universal health coverage in low-and middle-income countries: Results from 118 countries. Front. Public Health 2020, 7, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Or, Z.; Rococco, E.; Touré, M.; Bonastre, J. Impact of competition versus centralisation of hospital care on process quality: A multilevel analysis of breast cancer surgery in France. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croes, R.R.; Krabbe-Alkemade, Y.J.; Mikkers, M.C. Competition and quality indicators in the health care sector: Empirical evidence from the Dutch hospital sector. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2018, 19, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pross, C.; Averdunk, L.H.; Stjepanovic, J.; Busse, R.; Geissler, A. Health care public reporting utilization–user clusters, web trails, and usage barriers on Germany’s public reporting portal Weisse-Liste.de. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, P.W.; Dryer, R.D.; Hegeman-Dingle, R.; Mardekian, J.; Zlateva, G.; Wolff, G.G.; Lamerato, L.E. Cost burden of chronic pain patients in a large integrated delivery system in the United States. Pain Pract. 2016, 16, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, N. Do competition and managed care improve quality? Health Econ. 2002, 11, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B. Competition and Collaboration in the New NHS; Centre for Health and the Public Interest: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.Q. More reform of the English National Health Service: From competition back to planning? Int. J. Health Serv. 2019, 49, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichsenring, K.; Rodrigues, R.; Winkelmann, J.; Falk, R. Integrated Care, Competition and Choice-Removing barriers to care coordination in the context of market-oriented governance in Germany and Sweden. Int. J. Integr. Care. 2016, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishkin, S. Competition in Russian Healthcare. In HSE Working Paper; HSE University: Moscow, Russia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel, D.B.; Zwanziger, J.; Tomaszewski, K.J. HMO penetration, competition, and risk-adjusted hospital mortality. Health Serv. Res. 2001, 36 Pt 1, 1019–1035. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11775665/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Haley, D.R.; Zhao, M.; Spaulding, A.; Hamadi, H.; Xu, J.; Yeomans, K. The influence of hospital market competition on patient mortality and total performance score. Health Care Manager. 2016, 35, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strumann, C.; Geissler, A.; Busse, R.; Pross, C. Can competition improve hospital quality of care? A difference-in-differences approach to evaluate the effect of increasing quality transparency on hospital quality. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.C. The effect of financial pressure on the quality of care in hospitals. J. Health Econ. 2003, 22, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schors, W.; Kemp, R.; Van Hoeve, J.; Tjan-Heijnen, V.; Maduro, J.; Peeters, M.J.; Siesling, S.; Varkevisser, M. Associations of hospital volume and hospital competition with short-term, middle-term and long-term patient outcomes after breast cancer surgery: A retrospective population-based study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jürges, H.; Pohl, V. Medical guidelines, physician density, and quality of care: Evidence from German SHARE data. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2012, 13, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzampe, A.K.; Takahashi, S. Competition and quality of care under regulated fees: Evidence from Ghana. Health Econ. Rev. 2022, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Li, J.; Gravelle, H.; McGrail, M. Physician competition and low-value health care. Am. J. Health Econ. 2022, 8, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Jian, W.; Yip, W.; Pan, J. Perceived competition and process of care in rural China. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Propper, C.; Seiler, S.; van Reenen, J. The impact of competition on management quality: Evidence from public hospitals. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2015, 82, 457–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.S.; Zhan, C.; Mutter, R. Do different measures of hospital competition matter in empirical investigations of hospital behavior. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2005, 26, 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advin House. Types of Hospitals. Available online: https://advinhealthcare.com/types-of-hospitals (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Dranove, D.; White, W.D. Recent theory and evidence on competition in hospital markets. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 1994, 3, 169–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Pan, J. Does hospital competition lead to medical equipment expansion? Evidence on the medical arms race. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2021, 24, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, D.P.; McClellan, M.B. Is hospital competition socially wasteful? Q. J. Econ. 2000, 115, 577–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowrisankaran, G.; Town, R.J. Competition, payers, and hospital quality. Health Serv. Res. 2003, 38, 1403–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscelli, G.; Gravelle, H.; Siciliani, L.; Santos, R. Heterogeneous effects of patient choice and hospital competition on mortality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 216, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, F.; Jianping, Z.; Zhenjie, L.; Wenxing, L.; Li, Y. Does competition support integrated care to improve quality? Heliyon 2024, 10, e24836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhera, R.K.; Maddox, K.E.; Kazi, D.; Shen, C.; Yeh, R.W. Hospital revisits within 30 days after discharge for medical conditions targeted by the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in the United States: National retrospective analysis. BMJ 2019, 366, I4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martsolf, G.R.; Nuckols, T.K.; Fingar, K.R.; Barrett, M.L.; Stocks, C.; Owens, P.L. Nonspecific chest pain and hospital revisits within 7 days of care: Variation across emergency department, observation and inpatient visits. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, M.; Moreno-Serra, R.; Propper, C. Death by market power: Reform, competition, and patient outcomes in the National Health Service. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2013, 5, 134–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Z.; Gibbons, S.; Skellern, M. Does competition from private surgical centres improve public hospitals’ performance? Evidence from the English National Health Service. J. Public Econ. 2018, 166, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.K.; Sujenthiran, A.; Lewis, D.; Walker, K.; Cathcart, P.; Clarke, N.; Sullivan, R.; van der Meulen, J.H. Impact of patient choice and hospital competition on patient outcomes after prostate cancer surgery: A national population-based study. Cancer 2019, 125, 1898–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, M.; Sheckter, C.C.; Canner, J.K.; Rogers, S.O.; Offodile, A.C. Is bigger better?: The effect of hospital consolidation on index hospitalization costs and outcomes among privately insured recipients of immediate breast reconstruction. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brekke, K.R.; Straume, O.R. Competition policy for health care provision in Norway. Health Policy 2017, 121, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, V.; Dilmaghani, M. Competition and childcare quality: Evidence from Quebec. J. Soc. Policy 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Pistollato, M.; Charlesworth, A.; Devlin, N.; Propper, C.; Sussex, J. Association between market concentration of hospitals and patient health gain following hip replacement surgery. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 2015, 20, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skellern, M. The Effect of Hospital Competition on Value-Added Indicators of Elective Surgery Quality; Centre for Economic Performance: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://cep.lse.ac.uk/_new/publications/abstract.asp?index=5440 (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Berta, P.; Martini, G.; Moscone, F.; Vittadini, G. The association between asymmetric information, hospital competition and quality of healthcare: Evidence from Italy. J. R. Stat. Soc. A Stat. Soc. 2016, 179, 907–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, A. Assessing competition in hospital care markets: The importance of accounting for quality differentiation. RAND J. Econ. 2003, 34, 786–814. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1593788 (accessed on 5 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Propper, C.; Burgess, S.; Green, K. Does competition between hospitals improve the quality of care?: Hospital death rates and the NHS internal market. J. Pub. Econ. 2004, 88, 1247–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, M.; Propper, C.; Seiler, S. Free to choose: Reform and demand response in the British National Health Service. In CEP Discussion Paper No 1179; Centre for Economic Performance: London, UK, 2012; Available online: https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp1179.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Dranove, D.; Kessler, D.; McClellan, M.; Satterthwaite, M. Is more information better? The effects of “report cards” on health care providers. J. Polit. Econ. 2003, 111, 555–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranove, D.; Sfekas, A. Start spreading the news: A structural estimate of the effects of New York hospital report cards. J. Health Econ. 2008, 27, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, H.S.; Garnick, D.W.; Mark, D.H.; Peltzman, D.J.; Phibbs, C.S.; Lichtenberg, E.; McPhee, S.J. Does quality influence choice of hospital? JAMA 1990, 263, 2899–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.H. Quality and consumer choice in healthcare: Evidence from kidney transplantation. B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2006, 5, 0000101515153806531349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Z.; Gibbons, S.; Jones, S.; McGuire, A. Does hospital competition save lives? Evidence from the English NHS patient choice reforms. Econ. J. 2011, 121, F228–F260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckert, W.; Christensen, M.; Collyer, K. Choice of NHS-Funded hospital services in England. Econ. J. 2012, 122, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkevisser, M.; van der Geest, S.A.; Schut, F.T. Do patients choose hospitals with high quality ratings? Empirical evidence from the market for angioplasty in the Netherlands. J. Health Econ. 2012, 31, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, A.; Zengul, F.D.; Ozaydin, B.; Oner, N.; Breland, B.K. The impact of hospital competition on strategies and outcomes of hospitals: A systematic review of the US hospitals 1996–2016. J. Health Care Finance 2018, 44, 22–42. Available online: https://healthfinancejournal.com/index.php/johcf/article/view/142 (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Shen, V.C.; Ward, W.J., Jr.; Chen, L.K. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of hospital competition on quality of care: Implications for senior care. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 83, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalabadi, S.; Winter, V.; Schreyögg, J. A systematic review of the association between hospital cost/price and the quality of care. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2020, 18, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Tian, F.; Liu, Z.; Pan, J. Hospital competition and unplanned readmission: Evidence from a systematic review. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Sisti, L.G.; Isonne, C.; Nardi, A.; Mete, R.; Ricciardi, W.; Villari, P.; De Vito, C.; Damiani, G. Impact of hospital mergers: A systematic review focusing on healthcare quality measures. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.A.; Yeager, V.A.; Unroe, K.T.; Holmes, A.; Blackburn, J. The impact of rural general hospital closures on communities—A systematic review of the literature. J. Rural Health 2024, 40, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullens, C.L.; Hernandez, J.A.; Murthy, J.; Hendren, S.; Zahnd, W.E.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Scott, J.W. Understanding the impacts of rural hospital closures: A scoping review. J. Rural Health 2024, 40, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansberry, T.T.; Roberson, P.N.; Myers, C.R. US rural hospital care quality and the effects of hospital closures on the health status of rural vulnerable populations: An integrative literature review. Nurs. Forum 2023, 1, 3928966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, N.; Dukart, J.; van den Berg, N.; Augustin, J. Identifying determinants for traveled distance and bypassing in outpatient care: A scoping review. Inquiry 2019, 56, 46958019865434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, K.; Hashim, S.; Khankhara, M.; Said, I.; Shandakumar, A.T.; Zaman, S.; Veiga, A. What drives general practitioners in the UK to improve the quality of care? A systematic literature review. BMJ Open Qual. 2021, 10, e001127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradow, J.; Smith, S.D.; Davis, D.; Atchan, M. A systematic integrative review examining the impact of Australian rural and remote maternity unit closures. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, O.; Yong, J.; Scott, A. Nursing home competition, prices, and quality: A scoping review and policy lessons. Gerontologist 2022, 62, e384–e401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakovljevic, M.; Timofeyev, Y.; Zhuravleva, T. The impact of pandemic-driven care redesign on hospital efficiency. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2024, 17, 1477–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goro, S.; Challine, A.; Lefèvre, J.H.; Epaud, S.; Lazzati, A. Impact of interhospital competition on mortality of patients operated on for colorectal cancer faced to hospital volume and rurality: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0291672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, D.; Moscone, F.; Tosetti, E.; Vinciotti, V. Hospital quality interdependence in a competitive institutional environment: Evidence from Italy. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 89, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, P.; Iacoviello, M.; Passantino, A.; Scrutinio, D. Measures of hospital competition and their impact on early mortality for congestive heart failure, acute myocardial infarction and cardiac surgery. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2019, 31, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goude, F.; Kittelsen, S.A.; Malchau, H.; Mohaddes, M.; Rehnberg, C. The effects of competition and bundled payment on patient reported outcome measures after hip replacement surgery. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avdic, D. Improving efficiency or impairing access? Health care consolidation and quality of care: Evidence from emergency hospital closures in Sweden. J. Health Econ. 2016, 48, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundmacher, L.; Busse, R. The impact of physician supply on avoidable cancer deaths in Germany. A spatial analysis. Health Policy 2011, 103, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijlsma, M.J.; Koning, P.W.; Shestalova, V. The effect of competition on process and outcome quality of hospital care in the Netherlands. De Econ. 2013, 161, 121–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikkersheim, D.E.; Koolman, X. Dutch healthcare reform: Did it result in better patient experiences in hospitals? A comparison of the consumer quality index over time. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heijink, R.; Mosca, I.; Westert, G. Effects of regulated competition on key outcomes of care: Cataract surgeries in the Netherlands. Health Policy 2013, 113, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenova, Y.; Lim, L.; Salpynov, Z.; Gaipov, A.; Jakovljevic, M. Historical evolution of healthcare systems of post-soviet Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan: A scoping review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, R.; Laudicella, M.; Donni, P.L. Does hospital competition harm equity? Evidence from the English National Health Service. J. Health Econ. 2013, 32, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, E.C.; Kim, S.J.; Han, K.T.; Jang, S.I. How did market competition affect outpatient utilization under the diagnosis-related group-based payment system? Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, E.C.; Kim, S.J.; Han, K.T.; Han, E.; Jang, S.I.; Kim, T.H. The effect of competition on the relationship between the introduction of the DRG system and quality of care in Korea. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Cai, M.; Fu, Q.; He, K.; Jiang, T.; Lu, W.; Ni, Z.; Tao, H. Does hospital competition harm inpatient quality? Empirical evidence from Shanxi, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.H.; Lu, N.; Tang, C.H.; Chang, H.C.; Huang, K.C. Assessing the relationship between healthcare market competition and medical care quality under Taiwan’s National Health Insurance programme. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, D.R.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, H.; Wang, S.; Ju, K.; Chen, C.; Yang, L.; Jian, W.; Chen, L.; et al. Development of the China’s list of ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs): A study protocol. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2024, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Lin, X.; Pan, J. Heterogeneous effects of hospital competition on inpatient quality: An analysis of five common diseases in China. Health Econ. Rev. 2024, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Impact Assessment of Occupational Safety and Health Policy; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2012; Available online: https://oshwiki.osha.europa.eu/en/themes/impact-assessment-occupational-safety-and-health-policy (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- OECD. Regulatory Impact Assessment Across the European Union in Better Regulation Practices Across the European Union; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutter, R.L.; Wong, H.S.; Goldfarb, M.G. The effects of hospital competition on inpatient quality of care. Inquiry 2008, 45, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, M.; Liu, Y.; Cerda, A.; Simonyan, M.; Correia, T.; Mariita, R.M.; Kumara, A.S.; Garcia, L.; Krstic, K.; Osabohienj, R.; et al. The Global South political economy of health financing and spending landscape–history and presence. J. Med. Econ. 2021, 24 (Suppl. S1), 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).