Abstract

Background/Objectives: Vulvovaginal candidosis (VVC) is a common condition among women, with current diagnostic methods relying on clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. These traditional methods are often limited by the need for specialized training, variable performance, and lengthy diagnostic processes, leading to delayed treatment and inappropriate antifungal use. This review evaluates the efficacy of molecular diagnostic tools for VVC and provides guidance on their application in clinical practice. Methods: A literature search was conducted using PubMed to identify studies evaluating rapid diagnostic tests specifically for vulvovaginal Candida isolates. Inclusion criteria focused on studies utilizing molecular diagnostics for the detection of Candida species in VVC. Articles discussing non-vaginal Candida infections, non-English studies, and animal or in vitro research were excluded. Results: Twenty-three studies met the inclusion criteria, predominantly evaluating nucleid acid amplification tests/polymerase chain reaction (NAAT/PCR) assays and DNA probes. PCR/NAAT assays demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity (>86%) for VVC diagnosis, outperforming conventional diagnostic methods. Comparatively, DNA probes, while simpler, exhibited lower sensitivity. The included studies were mostly observational, with only one randomized controlled trial. Emerging diagnostic technologies, including artificial intelligence and integrated testing models, show promise for improving diagnostic precision and clinical outcomes. Conclusions: Molecular diagnostics offer a significant improvement in VVC management, though traditional methods remain valuable in resource-limited settings.

1. Introduction

Vulvovaginal candidosis (VVC) remains a significant health concern among women. It is estimated that 75% of women of reproductive age will have at least one episode of VVC. Approximately 7% of European women will have recurrent infections, and 9% of women between 25 and 34 years of age [1,2]. The most common symptoms include vulvar itching, pain, sometimes also dysuria or dyspareunia, and abnormal vaginal discharge. The feeling of discomfort in combination with a lack of severe physical disability, a general lack of readily available and properly trained physicians, in the current era of readily available internet information, discourages women from seeking medical advice, rather often leading to inappropriate over-the-counter treatments [3].

Compared to the microbiological diagnosis, the clinical diagnosis exhibits a sensitivity of 70.3% and a specificity of 83.7% [4]. The collection of a vaginal swab for testing, pH assessment, an odor test, and wet mount microscopy is recommended by the current guidelines for the management of abnormal vaginal discharge [5,6]. According to these guidelines, VVC should be suspected in the presence of a normal vaginal pH (<4.5) together with the clinical symptoms [7], but we disagree with this, as pH can vary from low to very high in the presence of Candida [8,9]. Microscopic examination of the vagina with saline or 10% KOH using light or phase-contrast microscopy is a very easy, rapid tool to confirm Candida infection [10,11,12]. Furthermore, the skills to master fresh wet mount microscopy can be mastered to an excellent level in a short training time [11] of only 10 h. When budding yeast or hyphae/pseudohyphae are noted, then a diagnosis of VVC can be confirmed [13,14]. Nonetheless, sensitivity can be very low in the case that too few microorganisms are present [10].

A lack of willingness to perform respective tests or proper training in the preparation and interpretation of a wet mount may also result in insufficient clinical evaluation [15]. A recent study has shown that, among women with respective symptoms, microscopy was conducted in only 17.4% of patients [16]. Microscopic assessment of vaginal discharge was not conducted in 37% of 150 clinic visits, and 42% of 50 physicians did not use microscopy in their evaluation of vulvovaginal disease, while, in over 90% of office visits, even the pH measurement of vaginal discharge was omitted [17]. A review of 149,934 American patients’ records indicated that over 60% lacked procedure codes for any type of vaginitis diagnostic testing [18]. In the Netherlands, only 16% (61/380) of general practitioners reported “always” or “often” using microscopy to diagnose VVC, and merely 7.9% (30/380) reported “always” or “often” using culture for this purpose [19]. Other studies identified high misdiagnosis rates of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and VVC, regardless of the use of microscopy, suggesting that inadequate use of microscopy might be a contributing factor [20]. The underutilization of these straightforward in-clinic tests often results in inadequate treatment, with up to 47% of patients receiving one or more inappropriate prescriptions, and 54% of visits involving treatment without sufficient evaluation [16,17,21], indicating that appropriate treatment occurs in less than half of the cases, contributing to the growing problem of antifungal resistance mirrored in increasing azole refractory symptoms and recurrent disease (rVVC) [4,20]. According to a recent survey conducted to measure awareness of vaginitis clinical guidelines and use of in-office diagnostic tools, physicians demonstrated limited awareness of the recommended diagnostic practice guidelines and had limited access to point-of-care diagnostic tools [22].

Self-diagnosis is equally inaccurate. In a previous study administering a questionnaire to 600 women to assess their knowledge of the symptoms and signs of VVC, only 11% of women correctly diagnosed this infection, although women who had experienced a prior episode were more often correct (35%) [23]. Self-sampling at moments of symptoms, however, can dramatically increase the sensitivity of the diagnosis of rVVC [24].

Despite the established value of microscopy in the diagnosis of VVC, cultures still seem to be the gold standard. However, cultivation of Candida species takes approximately 24–48 h, and even longer depending on species, which can lead to a delay in the correct diagnosis and treatment of a patient. Thus, prompt and accurate diagnosis is pivotal to achieving better outcomes. At the moment, extremely accurate and sensitive diagnostic tools are being developed, allowing physicians to diagnose VVC with substantially increased precision. Furthermore, various types of these rapid diagnostic tests have become so broadly available and affordable that self-sampling and self-testing are within reach. We aimed to summarize the current literature focusing on molecular diagnostic tools for VVC in a comprehensive review, and aim to focus on conclusive advice on proper testing today.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted using PubMed. The search was designed to retrieve studies focused on rapid diagnostic tests, specifically applied to vulvovaginal isolates of Candida species, focusing particularly on studies assessing and/or comparing the diagnostic parameters of molecular methods in VVC.

The search query was structured as follows:

(“vulvovaginal candidiasis” OR “vaginal candidiasis” or “vulvovaginal candidosis” OR “vaginal candidosis” OR “vaginal yeast infection” OR “Candida vaginitis” OR “yeast vaginitis” OR “Candida albicans” OR “vaginal Candida” OR “vaginitis” OR “vaginosis”) AND (“rapid diagnostic tests” OR “point of care testing” OR “PCR” OR “polymerase chain reaction” OR “DNA probes” OR “molecular diagnostics”) AND (“specificity” OR “sensitivity” OR “predictive value” OR “diagnostic accuracy”).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Studies specifically addressing VVC, excluding other forms of Candida infections such as oral or invasive candidosis.

- Studies employing molecular diagnostic techniques (e.g., PCR, DNA probes) directly related to the identification and characterization of Candida species in vaginitis.

- Studies assessing the predictive value of rapid detection methods in diagnosing VVC.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Articles focusing on Candida infections of non-vaginal sites, such as blood or systemic infections.

- Studies that discuss molecular diagnostics in the context of other vaginal infections that do not specifically include or differentiate Candida species.

- Articles published in languages other than English.

- Research involving animal models or in vitro studies without direct clinical relevance to human populations.

2.3. Screening and Selection Process

Articles retrieved from the initial search were first subjected to title and abstract screening to assess their relevance based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, we expanded our search to include relevant studies identified through reference checks of included articles and by reviewing similar articles suggested by PubMed. Subsequent full-text reviews were performed for selected studies to further evaluate their suitability for inclusion in the review.

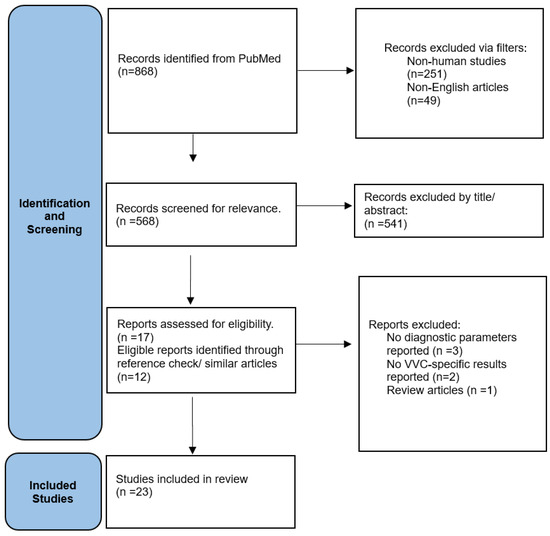

The selection process was visualized using a flowchart which detailed the number of records identified, included, and excluded, and the reasons for exclusions during the different phases of the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of study selection.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

Data from the included studies were systematically extracted using standardized tables to ensure consistent data collection and facilitate comparative analysis. The extraction process focused on study design, population characteristics, specific diagnostic methods/techniques employed, outcomes measured and/or the predictive accuracy of these methods. These data were then synthesized narratively to highlight the efficacy and practicality of various rapid diagnostic tests in clinical settings for the diagnosis of vaginal Candida infections.

3. Results

In total, 23 studies were finally included in this review [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] (Table 1), mostly assessing NAAT/PCR assays and DNA probes. Of note, both assays represent molecular techniques used to detect specific nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) in a sample, but they differ in their principles, sensitivity, and applications. Briefly, PCR/NAAT assays amplify nucleic acids to detect very small amounts of DNA/RNA with high sensitivity, have a broad spectrum of applications and require specialized equipment (thermal cycler). On the other hand, DNA probes bind directly to a target sequence without amplification, and their spectrum of application is more limited but includes gene detection and chromosome analysis, making them less sensitive but simpler in terms of detection.

Table 1.

Overview of Studies Evaluating the Diagnostic Performance of Molecular Methods for Vulvovaginal Candidosis.

Of those 23 studies above, 12 examined the diagnostic accuracy of NAAT/PCR assays [25,26,27,28,30,34,36,40,43,44,46,47], and 6 the diagnostic accuracy of DNA probes [31,32,35,38,39,42]; 3 compared PCR with DNA probes [33,41,45], and 2 referred to other assays [29,37]. Most studies came from the US or Europe and only 5 included Asian countries or Australia [25,27,29,32,37]. Of note, only one study was a randomized controlled trial [27], the majority of the rest being of observational or cross-sectional design [26,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,40,41,43,46,47]. In most studies, sensitivity and specificity for VVC diagnosis using molecular diagnostics was over 86% [25,26,28,29,33,34,36,43,44,45,46], way over conventional methods of diagnosis [26,27,34,43,46].

4. Discussion

This review aimed at exploring currently available rapid molecular diagnostic methods in VVC. A number of studies were identified including NAAT/PCR and DNA probing. We found that in most cases, molecular rapid diagnostic tests significantly outperform conventional diagnostic methods, including culture and wet mount microscopy, in terms of specificity and sensitivity in the diagnosis of VVC. However, current guidelines for the diagnosis of vaginitis include clinical evaluation, vaginal pH assessment, the “whiff” test and wet mount microscopy. Nonetheless, the current approach for the management of vaginal infections seems to provide suboptimal care [16]. In this context, molecular tests provide for rapid turnaround time, identification of NACs, and automation and standardization, avoiding human error and ensuring consistent results among laboratories. However, despite their high diagnostic capacity, their limited availability, need for technical expertise, increased cost, risk of overdiagnosis, and the lack of sensitivity data for antifungals demands caution be maintained in their use, so that rapid molecular diagnostic misuse is avoided. Vaginal candidosis should be analyzed in the context of the accompanying microbiota detected, so as to ensure if it is really candidosis, and if so, if it is a simple, complicated or recurrent case. The question of colonization without a need fortreatment, or invasive infection requiring intervention, calls for integration of different methods guided by clinical judgment, especially in settings involving mixed infections, but also in the case of increased antimicrobial resistance.

4.1. NAATs/PCR Assays

Two preliminary studies have demonstrated the superior sensitivity of PCR in detecting Candida species compared to yeast cultures. PCR identified higher percentages of both symptomatic (42.3% versus 29.8% with culture) and asymptomatic patients (7.3% versus 4.9%) [47]. However, partial concordance was observed between the two methods in detecting Candida sp., indicating that sole reliance on one method could lead to inaccurate diagnosis of VVC [40]. NAATs have shown high sensitivity rates (92.4%) in contrast with culture (83.3%) and microscopy (48.5%), although clinical correlation is required since NAAT may identify innocent colonization with Candida spp. [34]. This low sensitivity for microscopy can have several reasons. One is the failure to use phase contrast microscopy as opposed to normal light transmission microscopy. Indeed, the addition of phase contrast dramatically increased the diagnostic accuracy, even amongst highly experienced experts in microscopy [48]. Also, proper training in microscopy is often lacking in currently educational programs. Still, the high-level accuracy of phase contrast microscopy can be achieved by an intensive training of only 10 h [48]. These shortcomings, amongst others, like lack of time for and lack of availability of microscopes at the location where the patient is being examined, all induce a false low performance for microscopy.

A more recent study evaluated the performance of PCR coupled with quantum dot fluorescence analysis (QDFA) for the diagnosis of Candida strains in leukorrhea samples from patients with suspected VVC [25]. The sensitivity and specificity of PCR-QDFA was 89.01% and 93.69% for C. albicans, 85.88% and 99.37% for C. glabrata, 81.25% and 99.71% for C. tropicalis, and 92.86% and 99.57% for C. krusei, respectively, suggesting that this technique can be used as a rapid (approximately 4 h) diagnostic tool for identification of the most common Candida strains [25]. Another study compared the conventional method of cultures to PCR for Candida species in women with post-antibiotic candidosis [27]. PCR was more sensitive than culture, particularly among asymptomatic women; however, whether a positive PCR result represented colonization or a true infection warranting treatment remained difficult to distinguished. PCR was not able to detect significantly more cases of VVC in symptomatic patients compared to conventional cultures, suggesting that other yeast species, rather than Candida, could be implicated in post-antibiotic vulvovaginitis [27].

The BD MAX Vaginal Panel for the BD MAX system is a multiplex real-time PCR-based assay for specific VVC DNA targets [38]. Several studies have compared the performance of the BD MAXTM vaginal panel with conventional methods for the diagnosis of VVC. The BD MAXTM vaginal panel had higher sensitivity and specificity in detecting Candida spp. compared to KOH preparation and clinical diagnosis [26]. No significant differences were noted between clinician-collected samples and self-swabs, reporting sensitivity of 90.9% and specificity of 94.1%, respectively [36]. Analogous rates were reported by other authors who found a sensitivity and specificity of 97.4% and 96.8% for the diagnosis of VVC [28]. In a study conducted in UK, the sensitivity and specificity of the BD MAXTM vaginal panel for all Candida species was 86.4% and 86.0%, respectively, indicating that this method offers benefits in settings where immediate microscopy is unavailable [44]. When the BD MAXTM vaginal panel was compared to clinical diagnosis for VVC, authors reported a positive agreement of 53.5% suggesting that the clinical diagnosis missed nearly half of the cases detected by the vaginal panel assay; however, clinical diagnosis was efficient for confirming negative results with a negative percent agreement of 77.0% (false-positive rate 23.0%) [30]. Another study compared an Aptima Candida/Trichomonas vaginitis assay with yeast cultures and DNA sequencing for VVC. Sensitivity and specificity estimates were 91.7% and 94.9% for the investigational test, with similar rates for both clinician-collected samples and patient-collected samples, suggesting that this method was more predictive of infection than traditional diagnostic methods [43]. Moreover, the performance of the Seegene Allplex™ Vaginitis assay in the diagnosis of candidiasis was recently investigated. The sensitivity and specificity of the assay test compared to yeast cultures was 91.1% and 95.6% for any Candida spp., 88.1% and 98.2% for C. albicans, and 100% and 97.5% for non-albicans Candida. The presence of multiple infections did not interfere with the performance of the test; nonetheless, within the subgroup of symptomatic women, a syndromic approach led to under-diagnosis (Sensitivity: 66%), and therefore we would not recommend it, even in populations at high risk for sexually transmitted diseases [46]. This observation came in line with a recent study testing a new vaginal formulation for the treatment of VVC, showing that the Seegene test for Candida detection had an unacceptably low sensitivity when compared to culture, microscopy, and another PCR test (unpublished results, data on file). Hence, laboratory confirmation is necessary in all settings [49].

4.2. DNA Probes

A DNA probe analysis of vaginal fluid provides a point-of-care option for the three common causes of acute vulvovaginal symptoms [39]. The BD Affirm VPIII microbial identification test is a multianalyte, nucleic acid probe-based assay system designed to enable the identification and differentiation of organisms associated with vaginitis [33]. The sensitivity and specificity of clinician microscopically diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis were 39.6% and 90.4, respectively, while the sensitivity and specificity of the DNA probe diagnosis for the same type of vaginitis were 75.0% and 95.7% [35]. Another study also documented that the Affirm assay was significantly more likely to identify Candida than wet mount (11% were positive by Affirm compared to 7% by wet mount). Additionally, asymptomatic women were significantly more likely to test negative by Affirm (43% versus 5% by wet mount) [31]. The detection rate achieved by the Affirm assay did not significantly differ from that of vaginal culture (13.33% versus 14.87%) with a sensitivity and specificity rate of 82.76% and 98.80% for the Affirm test compared to the diagnostic standard [32]. When compared to Pap test, Affirm VPIII was more sensitive for the detection and identification of candidiasis (16.2% by Affirm assay versus 13.9% by Pap test) [38]. In a study conducted in Greece, the sensitivity and specificity of the Affirm assay was compared to those of Gram-stain, KOH preparation, and Sabouraud culture for Candida spp. detection [42]. Affirm VPIII showed very satisfactory rates in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients compared to the standard methods [42]. Of importance, several authors noted that the Affirm assay was more efficient and accurate for the diagnosis of multiple infections compared to other methods [32,35,38].

4.3. DNA Probes vs. PCR Tests

There are few studies comparing DNA probes (BD Affirm™ VPIII) to PCR-based methods. A recent study demonstrated that BD Max MVP detected VVC more frequently in contrast to the BD Affirm, with detection rates of 13.5% and 6%, respectively [41]. Another study reported that BD MAX vaginal panel sensitivity and specificity for detecting Candida spp. were 98.4% and 95.4% compared with 69.4% and 100% of the DNA probe method [45]. BD Affirm compared to CAN-PCR, a detection system that specifically detects C. albicans and C. glabrata, and showed lower sensitivity (58.1% versus 97.7%) but high specificity for Candida vaginitis [33].

4.4. Other Molecular Methods/Comparisons

Various alternative methods have been evaluated for the identification of Candida species and other yeast pathogens. MALDI-TOF MSs have shown high accuracy and speed for the identification of 98.3% of opportunistic yeast species and successful detection of all five top Candida species (C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and P. kudriavzveii). Even though its application requires a culture-positive sample, its use can significantly reduce time to diagnosis. API 20C AUX identified 97.26% of the most prevalent Candida species; however, a few clinically rare species were misidentified. The 21-plex PCR correctly identified 87.3% of all included yeast species (100% of the most prevalent Candida species) with a high specificity rate of 98.7% [29]. Lastly, a novel method based on gold nanoparticles has been developed and has been under investigation for rapid diagnosis of vaginal infections. In an experimental study, the method showed 100% sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of Candida vaginitis [37]

4.5. Study Limitations

While the reviewed studies offer significant insights into the diagnostic methods for vaginal infections, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations. Some of the included studies had small sample sizes and limited representation of certain ethnic groups. Similarly, our search was limited to English language papers and the Pubmed database, potentially missing a number of studies. Additionally, in some cases, the investigational test may have resulted in overdiagnosis of vaginitis since it could not distinguish colonization from pathogenic growth. A side-by-side comparison between the investigational test and the standard diagnostic method is not always performed, and even though extrapolation of results, while feasible, may lack precision. Lastly, although more sensitive and specific diagnostic tools have been developed, there is a notable absence of studies evaluating guidance for treatment based on these advanced methods and the impact of treatment selection on clinical outcomes [50]. To this end, future research should focus on addressing those limitations.

4.6. Future Perspectives

Overall, it seems that currently available and tested molecular rapid tests for the diagnosis of VVC perform quite satisfactorily. Nonetheless, the problem of concurrent presences of various infections and different types of vaginal diseases (BV, aerobic vaginitis, vaginal atrophy, or cytolytic vaginosis) persists. In this sense, tools that combine inputs such as automated microscopy, automated pH measurement, and patient-reported symptoms can enhance patient evaluation and treatment, irrespective of the caregiver’s training and skills that can be helpful [15]. Moreover, the use of artificial intelligence and neural network models in healthcare has proven to be an excellent alternative for various tasks such as risk stratification, diagnosis, prognosis, and appropriate treatment, hence an opportunity in VVC diagnosis and management [51]. These technologies enable rapid data analysis with considerably satisfactory sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional methods. Integrating such technological models with diagnostic methods has shown potential for early diagnosis and treatment in patients with VVC or candidemia [52,53].

Despite these advancements, it is important to note that molecular tests, while rapid and effective, should not yet be considered as point-of-care tests for VVC diagnosis. Alternative, cheaper, and less complex methods, including wet mount microscopy in the hands of an experienced user, could provide a definite diagnosis within minutes for a symptomatic VVC [11] and should not be abandoned without careful consideration.

Author Contributions

K.A. and G.D. designed study; G.S., E.P., Z.M., and S.O. performed literature searches, analyzed data, and drew Figures and Tables; K.A., D.P., and G.S. drafted original manuscript; F.D. and G.D. corrected manuscript; K.A. and G.D. oversaw study; K.A. revised manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sobel, J.D. Candidal vulvovaginitis. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 36, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W.; Kneale, M.; Sobel, J.D.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, e339–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donders, G.G.G.; Ravel, J.; Vitali, B.; Netea, M.G.; Salumets, A.; Unemo, M. Role of Molecular Biology in Diagnosis and Characterization of Vulvo-Vaginitis in Clinical Practice. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2017, 82, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aniebue, U.U.; Nwankwo, T.O.; Nwafor, M.I. Vulvovaginal candidiasis in reproductive age women in Enugu Nigeria, clinical versus laboratory-assisted diagnosis. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrard, J.; Wilson, J.; Donders, G.; Mendling, W.; Jensen, J.S. 2023 update to 2018 European (IUSTI/WHO) guideline on the management of vaginal discharge. Int. J. STD AIDS 2023, 34, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infections Guidelines 2021: Diseases Characterized by Vulvovaginal Itching, Burning, Irritation, Odor or Discharge. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/vaginal-discharge.htm (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Farr, A.; Effendy, I.; Frey Tirri, B.; Hof, H.; Mayser, P.; Petricevic, L.; Ruhnke, M.; Schaller, M.; Schaefer, A.P.A.; Sustr, V.; et al. Guideline: Vulvovaginal candidosis (AWMF 015/072, level S2k). Mycoses 2021, 64, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G.G.; Grinceviciene, S.; Ruban, K.; Bellen, G. Vaginal pH and microbiota during fluconazole maintenance treatment for recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis (RVVC). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 97, 115024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G.; Bellen, G.; Byttebier, G.; Verguts, L.; Hinoul, P.; Walckiers, R.; Stalpaert, M.; Vereecken, A.; Van Eldere, J. Individualized decreasing-dose maintenance fluconazole regimen for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (ReCiDiF trial). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, 613 e611–e619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglik, J.R.; Gaffen, S.L.; Hube, B. Candidalysin: Discovery and function in Candida albicans infections. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 52, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G.G.; Marconi, C.; Bellen, G.; Donders, F.; Michiels, T. Effect of short training on vaginal fluid microscopy (wet mount) learning. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2015, 19, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G.G.G. Definition and Definition and classification of abnormal vaginal flora. In Subclinical Infections and Perinatal Outcomes, Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology Editor-in-Chief; Arulkumaran, S., Ed.; Rapid Medical Media: East Sussex, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jafarzadeh, L.; Ranjbar, M.; Nazari, T.; Naeimi Eshkaleti, M.; Aghaei Gharehbolagh, S.; Sobel, J.D.; Mahmoudi, S. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: An overview of mycological, clinical, and immunological aspects. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 1546–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J.D. Vaginitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lev-Sagie, A.; Strauss, D.; Ben Chetrit, A. Diagnostic performance of an automated microscopy and pH test for diagnosis of vaginitis. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillier, S.L.; Austin, M.; MacIo, I.; Meyn, L.A.; Badway, D.; Beigi, R. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vaginal Discharge Syndromes in Community Practice Settings. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1538–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesenfeld, H.C.; Macio, I. The infrequent use of office-based diagnostic tests for vaginitis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 181, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, K.; Lyman, M.; Jackson, B.R. Possible misdiagnosis, inappropriate empiric treatment, and opportunities for increased diagnostic testing for patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis-United States, 2018. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberts, M.K.; Korporaal, H.; Vinkers, M.; van Belkum, A.; van Binsbergen, J.; Lagro-Janssen, T.; Helmerhorst, T.; van der Meijden, W. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches used by Dutch general practitioners. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2008, 14, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwiertz, A.; Taras, D.; Rusch, K.; Rusch, V. Throwing the dice for the diagnosis of vaginal complaints? Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2006, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, D.V.; Wiesenfeld, H.C.; Heine, R.P.; Krohn, M.A.; Hillier, S.L. Predictive value of the clinical diagnosis of lower genital tract infection in women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 190, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirjesy, P.; Banker, W.M.; Bonus, T.M. Physician Awareness and Adherence to Clinical Practice Guidelines in the Diagnosis of Vaginitis Patients: A Retrospective Chart Review. Popul. Health Manag. 2020, 23, S13–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D.G.; Dekle, C.; Litaker, M.S. Women’s use of over-the-counter antifungal medications for gynecologic symptoms. J. Fam. Pract. 1996, 42, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vergers-Spooren, H.C.; van der Meijden, W.I.; Luijendijk, A.; Donders, G. Self-sampling in the diagnosis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2013, 17, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Wu, W.; Li, X.; Zhong, W.; Pan, H. Clinical Evaluation of Polymerase Chain Reaction Coupled with Quantum Dot Fluorescence Analysis for Diagnosis of Candida Infection in Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Practice. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 4857–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwebke, J.R.; Gaydos, C.A.; Nyirjesy, P.; Paradis, S.; Kodsi, S.; Cooper, C.K. Diagnostic Performance of a Molecular Test versus Clinician Assessment of Vaginitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00252-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, S.N.; Pirotta, M.V.; Rudland, E.; Garland, S.M. Detection of Candida species by PCR in self-collected vaginal swabs of women after taking antibiotics. Mycoses 2006, 49, 523–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Quiñonero, A.; Castillo-Sedano, I.S.; Calvo-Muro, F.; Canut-Blasco, A. Accuracy of the BD MAX™ vaginal panel in the diagnosis of infectious vaginitis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 38, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arastehfar, A.; Daneshnia, F.; Kord, M.; Roudbary, M.; Zarrinfar, H.; Fang, W.; Hashemi, S.J.; Najafzadeh, M.J.; Khodavaisy, S.; Pan, W.; et al. Comparison of 21-Plex PCR and API 20C AUX, MALDI-TOF MS, and rDNA Sequencing for a Wide Range of Clinically Isolated Yeast Species: Improved Identification by Combining 21-Plex PCR and API 20C AUX as an Alternative Strategy for Developing Countries. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broache, M.; Cammarata, C.L.; Stonebraker, E.; Eckert, K.; Van Der Pol, B.; Taylor, S.N. Performance of a Vaginal Panel Assay Compared with the Clinical Diagnosis of Vaginitis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 138, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.L.; Fuller, D.D.; Jasper, L.T.; Davis, T.E.; Wright, J.D. Clinical Evaluation of Affirm VPIII in the Detection and Identification of Trichomonas vaginalis, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Candida Species in Vaginitis/Vaginosis. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 12, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.W.; Park, Y.J.; Hur, S.Y. Affirm VPIII microbial identification test can be used to detect gardnerella vaginalis, Candida albicans and trichomonas vaginalis microbial infections in Korean women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2016, 42, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, C.P.; Lembke, B.D.; Ramachandran, K.; Body, B.A.; Nye, M.B.; Rivers, C.A.; Schwebke, J.R. Comparison of nucleic acid amplification assays with BD affirm VPIII for diagnosis of vaginitis in symptomatic women. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 3694–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danby, C.S.; Althouse, A.D.; Hillier, S.L.; Wiesenfeld, H.C. Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing Compared with Cultures, Gram Stain, and Microscopy in the Diagnosis of Vaginitis. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2021, 25, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, D.G.; Hendrich, J.; Payne, P.M.; Getts, A.; Rassekh, R.; Mathis, D.; Litaker, M.S. Office laboratory diagnosis of vaginitis. Clinician-performed tests compared with a rapid nucleic acid hybridization test. J. Fam. Pract. 1995, 41, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaydos, C.A.; Beqaj, S.; Schwebke, J.R.; Lebed, J.; Smith, B.; Davis, T.E.; Fife, K.H.; Nyirjesy, P.; Spurrell, T.; Furgerson, D.; et al. Clinical Validation of a Test for the Diagnosis of Vaginitis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, H.; Varshosaz, J.; Fazeli, H.; Sharafi, S.M.; Mirhendi, H.; Chadeganipour, M.; Yousefi, H.A.; Manoochehri, K.; Chermahini, Z.A.; Jafarzadeh, L.; et al. Rapid differential diagnosis of vaginal infections using gold nanoparticles coated with specific antibodies. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 208, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, A.W.; Harigopal, M.; Hui, P.; Schofield, K.; Chhieng, D.C. Comparison of Affirm VPIII and Papanicolaou tests in the detection of infectious vaginitis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 135, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, N.K.; Neal, J.L.; Ryan-Wenger, N.A. Accuracy of the Clinical Diagnosis of Vaginitis Compared to a DNA Probe Laboratory Standard. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 113, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårdh, P.A.; Novikova, N.; Witkin, S.S.; Korneeva, I.; Rodriques, A.R. Detection of candida by polymerase chain reaction vs microscopy and culture in women diagnosed as recurrent vulvovaginal cases. Int. J. STD AIDS 2003, 14, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarathna, D.H.; Lukey, J.; Coppin, J.D.; Jinadatha, C. Diagnostic performance of DNA probe-based and PCR-based molecular vaginitis testing. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0162823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrikkos, G.; Makrilakis, K.; Pappas, S. Affirm VP III in the detection and identification of Candida species in vaginitis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ. Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2007, 96, 39–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwebke, J.R.; Taylor, S.N.; Ackerman, R.; Schlaberg, R.; Quigley, N.B.; Gaydos, C.A.; Chavoustie, S.E.; Nyirjesy, P.; Remillard, C.V.; Estes, P.; et al. Clinical Validation of the Aptima Bacterial Vaginosis and Aptima Candida/Trichomonas Vaginitis Assays: Results from a Prospective Multicenter Clinical Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01643-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrard, J. Evaluation of the BD MAX™ Vaginal Panel for the detection of vaginal infections in a sexual health service in the UK. Int. J. STD AIDS 2019, 30, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Timm, K.; Borders, N.; Montoya, L.; Culbreath, K. Diagnostic performance of two molecular assays for the detection of vaginitis in symptomatic women. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 39, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira-Baptista, P.; Silva, A.R.; Costa, M.; Aguiar, T.; Saldanha, C.; Sousa, C. Clinical validation of a new molecular test (Seegene Allplex™ Vaginitis) for the diagnosis of vaginitis: A cross-sectional study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenbacher, T.; Witkin, S.S.; Ledger, W.J.; Tolbert, V.; Gingelmaier, A.; Scholz, C.; Weissenbacher, E.R.; Friese, K.; Mylonas, I. Relationship between clinical diagnosis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis and detection of Candida species by culture and polymerase chain reaction. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2009, 279, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G.G.; Larsson, P.G.; Platz-Christensen, J.J.; Hallen, A.; van der Meijden, W.; Wolner-Hanssen, P. Variability in diagnosis of clue cells, lactobacillary grading and white blood cells in vaginal wet smears with conventional bright light and phase contrast microscopy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2009, 145, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, I.; Paul, B.; Das, N.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Chakrabarti, M.K. Etiology of Vaginal/Cervical Discharge Syndrome: Analysis of Data from a Referral Laboratory in Eastern India. Indian J. Dermatol. 2018, 63, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.H.; Hong, S.K.; Cho, S.I.; Ra, E.; Han, K.H.; Kang, S.B.; Kim, E.C.; Park, S.S.; Seong, M.W. Analysis of the Vaginal Microbiome by Next-Generation Sequencing and Evaluation of its Performance as a Clinical Diagnostic Tool in Vaginitis. Ann. Lab. Med. 2016, 36, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidaki, M.Z.; Allahyari, E.; Ghanbarzadeh, N.; Nikoomanesh, F. Using Artificial Neural Network to Predict Predisposing to Vulvovaginal Candidiasis among Vaginitis Cases. Mod. Care J. 2024, 21, e135173. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, M.L.; Benevides, C.A.; Zanchettin, C.; Menezes, F.D.; Inacio, C.P.; de Lima Neto, R.G.; Filho, J.; Neves, R.P.; Almeida, L.M. Breaking barriers in Candida spp. detection with Electronic Noses and artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, D.R.; Marelli, C.; Mora, S.; Guastavino, S.; Russo, C.; Brucci, G.; Limongelli, A.; Vena, A.; Mikulska, M.; Tayefi, M.; et al. Early diagnosis of candidemia with explainable machine learning on automatically extracted laboratory and microbiological data: Results of the AUTO-CAND project. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2285454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).