Abstract

(1) Background: Comorbidity between Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD), mood, and anxiety disorders represents a significant health burden, yet its neurobiological underpinnings are elusive. The current paper reviews all genome-wide association studies conducted in the past ten years, sampling patients with AUD and co-occurring mood or anxiety disorder(s). (2) Methods: In keeping with PRISMA guidelines, we searched EMBASE, Medline/PUBMED, and PsycINFO databases (January 2010 to December 2020), including references of enrolled studies. Study selection was based on predefined criteria and data underwent a multistep revision process. (3) Results: 15 studies were included. Some of them explored dual diagnoses phenotypes directly while others employed correlational analysis based on polygenic risk score approach. Their results support the significant overlap of genetic factors involved in AUDs and mood and anxiety disorders. Comorbidity risk seems to be conveyed by genes engaged in neuronal development, connectivity, and signaling although the precise neuronal pathways and mechanisms remain unclear. (4) Conclusion: given that genes associated with complex traits including comorbid clinical presentations are of small effect, and individually responsible for a very low proportion of the total variance, larger samples consisting of multiple refined comorbid combinations and confirmed by re-sequencing approaches will be necessary to disentangle the genetic architecture of dual diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) affected >100 million people in 2016 [1], whereas, a year earlier, 322 million lived with depression and 264 million suffered from anxiety disorders [2]. In addition to being globally significant health problems in their own right, these disorders occur together much more frequently than expected by chance, confirming a phenomenon known as comorbidity or dual diagnosis which has been verified by a number of population- [3,4,5,6,7,8,9] and clinically [10,11,12,13,14] based studies over the past three decades. Generally estimated, odds ratios (OR) for the association are 1.64 and 1.53 for the combination anxiety disorder–AUD and depression–AUD respectively [15].

Co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders increase the severity of AUD and associated disability [16] whereas AUD negatively impacts anxiety and mood disorder by worsening symptoms [17], magnifying suicide risk [18], and compromising treatment efficacy [17,19]. Thus, advances in understanding the mechanisms underlying comorbidity will ultimately result in better treatment outcomes. The variety of explanation hypotheses of comorbidity [20] may be broken down to two groups [21]. According to the causal or illness-mediated theories [22], a primary alcohol, mood, or anxiety disorder directly or indirectly causes the secondary condition. The theories on shared etiological factors, on the other hand, assume that one or more common causal factor(s) drive the development of both disorders. While causal theories are outside the scope of this paper, common neurobiological etiology, particularly the research on the genetic basis of comorbidity, will be discussed below in detail.

In the past several decades, twin and other behavioral genetic studies have shown a substantial genetic overlap between internalizing disorders of the mood and anxiety spectrum and externalizing disorders encompassing alcohol and drug dependence [23,24,25]. Subsequently, a more comprehensive exploration of the genetic basis of comorbidity was provided by linkage studies [26] which examine families with multiple affected members to detect chromosomal regions with genetic risk variants [27]. In a landmark linkage mapping study on alcohol–depression comorbidity, Nurnberger et al. [28] reanalyzed dataset from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) [29,30], consisting of 1295 individuals from families affected by alcoholism, confirming a locus on chromosome 1 (near the 120 cm region) containing gene(s) that significantly predispose individuals to alcoholism, depression, or both. Notably, several subsequent studies [31,32,33] have confirmed at least two linkage regions at around 70 and 120 cM of chromosome 1 as substantially associated with neuroticism—a personality trait intimately related to a broad array of anxiety symptoms, depression, and alcoholism [34].

Over the past 15 years, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have become technically as well as economically affordable and as a consequence of that, they are gradually displacing linkage and other candidate gene studies in the field of psychiatric genetics [35]. GWAS entail screening hundreds of thousands to a million genomic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) in a case-control design allowing for statistical calculation of each particular variant’s association with the phenotype of interest expressed as an odds ratio of increased or decreased risk [36]. Initially successful with the detection of genes involved in age-related macular degeneration in 2005 [37], the GWAS design has now been broadened to numerous complex traits, including neuropsychiatric illnesses. Spotting a large number of disease-associated risk loci across the human genome for every phenotype of interest, GWAS confirm the pre-existing assumption that rather than single causal genes (according to the Mendelian pattern of inheritance), hundreds to thousands of genetic variants widely spread in the population may confer small accretions of risk for a common disease [38]. In complex genetic disorders such as mental illnesses, the GWAS approach is much more powerful in distinguishing meaningful illness-associated genetic loci as compared to the traditional twin and linkage studies discussed above. While in the most common type of GWAS sampling individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder the attributable risk to each genome-wide significant SNP is small (OR < 1.2), the accumulation of multiple risk SNPs allows for the development of the composite weighted sum of the effects of all common variants, known as the polygenic risk score (PRS) [36]. The latter might be able to aid diagnostics of psychiatric disorders in the near future [39].

Although the current large GWAS databases are focusing on single diagnoses—mostly schizophrenia [36], major depression or bipolar disorder [40], an increasing number of studies in the past 10 years have addressed dual diagnosis phenotypes with a GWAS approach. The current paper attempts to summarize and discuss the results of all the published GWAS exploring samples with alcohol misuse and anxiety or mood disorders comorbidity. In doing so, outlining some possible neurobiological mechanisms and pathways connecting both groups of disorders will be attempted.

2. Materials and Methods

We implemented a systematic literature review based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [41].

2.1. Search Algorithm

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Articles written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals;

- Studies performed in humans (animal models relevant to human findings were allowed);

- Studies of samples with phenotypes of interest—MDD/AUD, BPD/AUD or Anxiety/Anxiety Disorder/AUD identifying the presence of SNPs with a genome-wide level of significance (p < 5 × 10−8) or suggestive genome-wide level of significance (p < 1 × 10−4);

- Papers reporting statistically significant correlation between MDD-PRS, BPD-PRS or Anxiety/Neuroticism PRS and alcohol phenotypes—DSM-IV alcohol dependence or alcohol abuse.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies including alcohol phenotypes that are not based on DSM-IV/5 or ICD-10 criteria, but on screening or other tools for assessment of alcohol use instead—e.g., Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [42].

2.2. Data Sources and Keywords

EMBASE, Medline/PUBMED, and PsycINFO databases were searched for a period of 10 years—from 01/01/2010 to 31/12/2020 with the following keywords:” Co-occurring disorders”, “Comorbidity”, “Dual Diagnosis”, “Mood disorder(s)”, “Major Depression (MDD)”, “Bipolar Disorder”, “Anxiety Disorder(s)”, Alcohol Use Disorder”, “Alcohol Abuse”, “Alcohol Dependence” and “Genome-wide association study(ies) (GWAS)”. While analyzing articles identified by this search, all papers indexed in the reference sections were explored and included in the review if eligible.

2.3. Selection of Studies

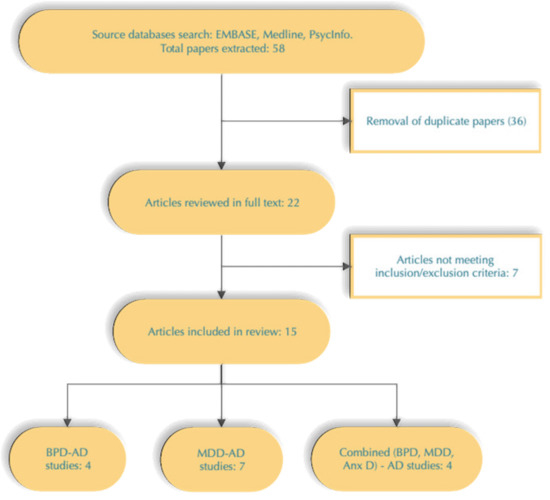

A total of 58 studies were detected by the initial search performed by one author (EN). After the removal of duplicates, 22 articles remained. All of them were reviewed in full text by three authors—K.S. and D.D. (psychiatrists) and Z.K. (specialist in medical genetics) to assess their final eligibility for this paper (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

3. Results

This review includes 15 articles focusing on GWAS in samples with AUD and co-occurring mood or anxiety disorders. Both a narrative approach and statistical measures (as presented by authors) were used to summarize results which are presented on Table 1. In the studies looking for a correlation between PRS for MDD and BPD and AUD phenotype, the former was obtained from the following discovery samples: Psychiatric Genetic Consortium (PGC) MDD-PRS1 [43] and MDD-PRS2 [44] and PGC BPD-PRS1 [45]. The majority of studies included subjects of White/Caucasian adults of European-American (EA), African-American (AA) or European ancestry.

Table 1.

Overview of GWAS focusing on comorbid mood, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders.

4. Discussion

The present paper aims to summarize studies applying the genome-wide association approach in the search of shared genetic diathesis of mood and anxiety disorders with AUDs. GWAS have brought a massive advance in the understanding of genetic mechanisms that underlie mental disorders and the expansion of insight is being now gradually translated from “pure” diagnoses (i.e., schizophrenia, MDD, etc.) to comorbid phenotypes. In one of the first GWAS analyses of high-risk polymorphisms in BPD and SUD, Johnson et al. (2009) [78] established an overlap of the genetic diathesis for both groups of conditions compatible with the polygenic disorders model. Extracting data from several samples with BPD (n = 1461) and SUD (n = 400), these authors identified nominally significant SNPs in 69 high-risk genes that were common between the BPD samples and 23 of them were also associated with higher risk of SUD. Some of the spotted high-risk loci have been replicated by later studies included in this review—for instance, SNPs in the COLLA2 gene [46] found to be associated with BPD-AD phenotype, or CDH13 gene involved in the MDD-AD association according to Edwards et al. [49] study. In addition, genes belonging to gene families later found to be associated with AUD-mood disorders comorbidity were also identified in Johnson et al.’s pivotal study—for example semaphorins which are a group of transmembrane proteins engaged in axonal guidance during neural development. An SNP within the semaphorin 3A gene was confirmed in 2017 by Zhou et al. [63] to be involved in MDD-AD comorbidity.

It appears that the majority of significant risk-associated SNPs detected in samples with mood and anxiety disorders and co-occurring AUD are located in genome regions primarily engaged in the processes of neural growth, development, and differentiation as well as in the coding of neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels controlled by them. In this respect, a comparison of the results of GWAS with that of the first-generation genetic studies on alcoholism (linkage and candidate gene studies) which emphasize genes involved in alcohol metabolism—e.g., alcohol-dehydrogenase (ADH) gene cluster [79] or genes coding targets of alcohol pharmacodynamic activity—e.g., GABRA2 (GABA-A receptor subunit α-2) [80] is very characteristic. Indeed, some of these early studies have correctly identified genes that were later found to markedly increase the risk of alcoholism being comorbid with mood or anxiety disorders. For example, the early candidate gene for alcoholism DRD2 (dopamine type 2 receptor) [81] was linked through several SNPs to state and trait levels of anxiety in a Korean sample of AD patients (n = 573) by Joe et al. in 2008 [82], only to be confirmed as a genome-wide significant locus for shared vulnerability to both alcoholism and BPD (Levey et al. 2014 [51] and anxiety disorder-problem alcohol use (Colbert et al. 2020 [74]). Interestingly, this same gene along with ANKK1 was recently confirmed by a meta-analysis of the three largest GWAS on depression as having a key role in MDD [83]. Such a finding supports the significant pleiotropic effects of genes underlying mental disorders and the multifunctional nature or neuronal circuits in which the products of these genes are involved.

Other genetic loci captured by first-generation studies have only shown their role in comorbidity by broadening of the initial phenotype. Thus, in the COGA study previously mentioned [29,30], enriching the phenotype of interest from alcoholism only to alcoholism and ADHD, allowed for a recognition (by a Lod score > 3.0) of a locus on chromosome 2 harboring tachykinin receptor gene (TACR1). Subsequently, this gene which codes a receptor for the Substance P neurotransmitter and modulator peptide, involved in stress response and mood and anxiety regulation, has been confirmed as being implicated in BPD–AD phenotype in the GWAS study of Sharp et al. (2014) [50]. It may be expected, therefore, that future GWAS employing broader phenotype definitions (e.g., BPD + ADHD + AUD), could identify yet other, previously unknown or considered alcoholism “specific” genes, as relevant to AUD–mood and/or anxiety disorder comorbidity.

It should be noted however that some promising genetic regions marked by recent genetic studies in comorbid AUD–mood disorder or AUD–anxiety disorder samples, have not been so far replicated by the genome-wide approach. In the MDD-AUD association for example, Procopio et al. (2013) [84] studied a sample of 333 AD women in Austria of which 51 had a combination of MDD and AD known as Type III alcoholism according to the classification of Lesch et al. [85]. The authors found a significant association of the MDD–alcoholism phenotype with haplotypes (i.e., SNPs) within ADCY5 (type 5 adenylyl cyclase protein gene) on chr. 3, ADCY2 (chr. 5), and ADCY8 (chr. 8) that could discriminate type III alcoholism patients from type I and II. The ADCY trans-membrane protein family is intimately related to the functioning of G-protein coupled receptors and is engaged in procedural learning, synaptic plasticity, and neurodegeneration. In addition to that, it has been linked to the vulnerability to alcohol dependence by previous GWAS studies. [86]. However, no study as yet has replicated ADCY protein family’s relevance to the comorbid phenotype of AD and mood or anxiety disorder. Similarly, in the BPD-alcohol abuse phenotype Mosheva et al. (2019) [87] have recently reported a SNP (rs1034936) within the CACNA1C gene which codes the α1-subunit of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel and has been implicated in various mental disorders (including MDD and BPD) but also in alcohol effects on CNS. However, not a single GWAS has identified it as directly contributing to BPD–AUD comorbidity so far. In the anxiety disorder(s)–AD phenotype, a recent study by Hodgson et al. (2016) [88] in a sample of 1284 Mexican-Americans from 75 pedigrees reported significant bivariate linkage peaks for alcohol dependence–anxiety at chromosome 9 (9q33.1-q33.2). In addition to hosting rare copy number variants (CNV) that have been linked to autistic spectrum disorders, ADHD, and OCD by a large GWAS [89], this locus also contains the astroactin-2 (ASTN2) and tri-component motif protein 32 (TRIM32). The former encodes the homonymous transmembrane protein, which along with related astroactin-1 (ASTN1) (1q25.2) has a key role in glial-directed neuronal migration during the embryonal formation of the neocortex [89] while the latter is engaged in functional control of dysbindin—a protein intimately involved in the genetics of schizophrenia [90] and influencing glutamate and dopamine signalization [91]. It remains to see whether future GWAS with AUD-anxiety disorders phenotypes will replicate the preliminary significant pleiotropic signals for alcohol dependence–anxiety found in 9q33.1-q33.2 locus.

Further, in the context of causal theories of comorbidity mentioned above (22) it should be noted that some GWAS studies support a causal role of one of the associated disorders on the other. Thus, Polimanti et al. (2019) [71], analyzing large datasets of PGC-MDD-PRS2, PGC-AD-PRS, and UK-Biobank, found evidence for the causal influence of MDD on AD (i.e., mediated pleiotropy) but not the opposite. A possible neurobiological mechanism substantiating such a finding could be an inherited dysfunction of the DRD2 gene (discussed above) translated into lower activity of the D2 receptors resulting in anhedonia and compensatory drug or alcohol consumption. Similarly, in the background of anxiety disorders–alcoholism comorbidity, some of the available GWAS data support the occurrence of alcohol misuse in an attempt to alleviate anxiety compatible with the self-medication hypothesis of comorbidity [92]. For instance, Colbert et al. (2020) in the study reviewed above observed a negative correlation between anxiety and alcohol consumption at chromosome 7:68 562 932-69 806 895 which contains the AUTS2 (autism susceptibility candidate 2 gene). AUTS2, involved in activation of gene transcription as well as in neuronal migration during embryonal development, is an important candidate gene for autism spectrum and intellectual disability disorders; along with being expressed in amygdala and frontal cortex, it also influences alcohol consumption in humans [93]. Besides, its downregulation in Drosophila reduces sensitivity to alcohol, thus possibly increasing consumption [93], while in mice deficient in AUTS2, a decrease in anxiety-related behaviors is evident [94]. Hence, it may be speculated that AUTS2 not only affects anxiety and alcohol consumption in inverse directions, but, as a result of altered function, produces higher anxiety levels and subsequent alcohol misuse induced by the self-medication mechanism. Obviously, to validate or reject the hypothesis of mediated pleiotropy in mood and anxiety disorders comorbid with alcohol misuse, future studies with much larger and refined discovery and target samples will be needed.

Finally, several potential target genes and respective neural mechanisms contributing to comorbidity will be outlined. First in the list is glutamate neurotransmission with its probable role in dual diagnosis supported by recent GWAS implicating the glutamate receptor gene GRIA4 in nicotine dependence–MDD phenotype [95] as well as by the finding that alcohol exposure changes the expression of this and other glutamatergic genes [96]. Besides, impaired NMDA receptor functioning seen in BPD may contribute to the increased tolerance to alcohol resulting in alcohol misuse [97]. Another gene with a high likelihood of contributing to dual diagnosis phenotypes is the α-endommanosidase gene MANEA which, despite its unclarified biological function, has variants found to increase anxiety disorder risk in samples recruited from genetic studies of alcohol and drug dependence [98]. Further in the line are genes participating in circadian clock function such as ARNT, ARNT2, and PER2 which have been implicated in anxiety disorders–alcohol dependence comorbidity [99,100] and D-box binding protein gene (Dbp) supposedly influencing the risk for both bipolar disorder and alcoholism [101].

An inherent limitation of genome-wide association design pertinent to its applicability to co-occurring AUD, mood, and anxiety disorders is the inability to link identified high-risk polymorphisms with meaningful neurobiological pathways, thus paving the way for more successful treatment and prevention strategies. Another major restriction of the currently available GWAS focusing on comorbidity is that discovery samples used for identification of high-risk SNPs are of Western European and North-American ancestry only (see table) which substantially limits the generalization of findings across other populations, given that PRS are very sensitive to ethnic background [102]. This implies that variability in a PRS can be seriously affected by allele frequency differences, divergences in estimated effect sizes, and dissimilarities in population structure across various ethnic groups. For example, the 19 G/C (rs1800883) SNP in the serotonin 5A gene (5-HT5A) was found to have a protective role in relation to BPD risk in a British sample (n = 374) [103] whereas this same variant was significantly associated with BPD risk in a Bulgarian candidate gene study (n = 450) [104]. Furthermore, PRS usually measures only the contribution of common SNPs in an individual not accounting for other classes of variation which may also influence genetic risk. For instance, copy number variants known to exert a large impact on disease risk are not included in a typical PRS. For the same reason, rare pathogenic alleles are quite often eliminated from PRSs derived from a GWAS summary statistics, because GWASs by definition only include “common” variants with a population prevalence ≥ 1%. Finally, as mentioned by some [49], the discovery samples from which MDD and BPD-PRS are extracted (like for example the PGC-MDD-PRS and PGC-BPD-PRS) might include a high number of alcohol or other substance-induced mood episode cases which significantly confounds the results of studies exploring shared genetic diathesis between alcohol use disorders and mood and anxiety disorders based on PRS.

5. Conclusions

In summary, GWAS exploring the genetic background of comorbid AUD, mood, and anxiety disorders demonstrate that multiple genetic variants with different directions and magnitudes influence the development, manifestation, and variation of these dual diagnosis phenotypes. Comorbidity risk is probably conveyed by genes engaged in neuronal development, connectivity, and signaling. It may therefore be hypothesized that comorbidity might represent an expression of a neurodevelopmental disruption that affects cortical and other areas involved in executive functioning, and emotional, and reward processing. In turn, that renders affected individuals susceptible to the occurrence of both mental disorder and SUD, including alcohol [22].

In addition to the intrinsic restriction of GWAS design, a significant barrier to eliciting the role of genetic variants involved in comorbidity is that they supposedly interact with one another (epistasis), may be involved in multiple phenotypes (pleiotropy), and are subject to complex epigenetic influences which are currently largely unknown.

Given that genes associated with complex traits including comorbid clinical presentations are of small effect, and are individually responsible for a very low proportion of total variance, larger samples consisting of multiple refined comorbid combinations and confirmed by re-sequencing approaches will be necessary to disentangle the genetic nature of dual diagnosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.; methodology, K.S., D.D., E.N.; investigation, E.N., K.S.; data curation, K.S., D.D., Z.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S., E.N.; writing—review and editing, K.S., E.N., D.D., Z.K.; project administration, K.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Griswold, M.G.; Fullman, N.; Hawley, C.; Arian, N.; Zimsen, S.R.M.; Tymeson, H.D.; Venkateswaran, V.; Tapp, A.D.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Salama, J.S.; et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders; WHO: Geneve, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, B.F.; Stinson, F.S.; Dawson, D.A.; Chou, P.; Dufour, M.C.; Compton, W.; Pickenberg, R.F.; Kaplan, K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschloo, L.; Vogelzangs, N.; Van den Brink, W.; Smit, J.; Veltman, D.; Beekman, A.T.; Pennix, B.W. Alcohol use disorders and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 200, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, K.; Mills, K.; Ross, J.; Teesson, M. Substance use disorders comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders in the Australian general population. Drug Alc. Rev. 2016, 36, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Crum, R.M.; Warner, L.A.; Nelson, C.B.; Schulenberg, J.; Anthony, J.C. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offord, D.R.; Boyle, M.H.; Campbell, D.; Goering, P.; Lin, E.; Wong, M.; Racine, Y.A. One-year prevalence of psychiatric disorder in Ontarians 15 to 64 years of age. Can. J. Psychiatry 1996, 41, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graaf, R.; Bijl, R.V.; Smit, F.; Vollebergh, W.A.; Spijker, J. Risk factors for 12-month comorbidity of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders: Findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasin, D.S.; Stinson, F.S.; Ogburn, E.; Grant, B.F. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, K.P.; Compton, W.; Stinson, F.S.; Grant, B.F. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 67, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuria, M.W.; Ndetei, D.M.; Obot, I.S.; Khasakhala, L.I.; Bagaka, B.M.; Mbugua, M.N.; Kamau, J. The association between alcohol dependence and depression before and after treatment for alcohol dependence. ISRN Psychiatry 2012, 482802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriels, C.M.; Macharia, M.; Weich, L. Psychiatric comorbidity among alcohol-dependent individuals seeking treatment at the Alcohol Rehabilitation Unit, Stikland Hospital. S. Afr. J. Psychiatr. 2019, 25, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardose, B.M.; Sant’Anna, M..K.; Dias, V.D.; Andreazza, A.C.; Ceresér, K.M.; Kapczinski, F. The-impact of co-morbid alcohol use disorder in bipolar patients. Alcohol 2008, 42, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuckit, M.A.; Hesselbrock, V. Alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders: What is the relationship. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 1723–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, H.M.; Cleary, M.; Sitharthan, T.; Hunt, G.E. Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990-2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 154, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.; Teesson, M. Alcohol use disorders comorbid with anxiety, depression and drug use disorders. Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well Being. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002, 68, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; Randall, C.L. Anxiety and alcohol use disorders: Comorbidity and treatment considerations. Alcohol Res. 2012, 34, 414–431. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.; Uezato, A.; Newell, J.M.; Frazier, E. Major depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2008, 21, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulds, J.A.; Adamson, S.J.; Boden, J.M.; Williman, J.A.; Mulder, R.T. Depression in patients with alcohol use disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes for independent and substance-induced disorders. J. Affect. Disord 2015, 185, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueser, K.T.; Drake, R.E.; Wallach, M.A. Dual diagnosis: A review of etiological theories. Addict. Behav. 1998, 23, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, T.; Mann, K. Comorbidity in alcohol use disorders: Focus on mod, anxiety and personality. In Dual Diagnosis: The Evolving Conceptual Framework; Stohler, R., Rösler, W., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2005; pp. 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Stoychev, K.R. Neuroimaging studies in patients with mental disorder and co-occurring substance use disorder: Summary of findings. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.F. The structure of common mental disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1999, 56, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, R.F.; McGue, M.; Iacono, W.G. The higher-order structure of common DSM mental disorders: Internalization, externalization, and their connections to personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001, 30, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Prescott, C.A.; Myers, J.; Neale, M.C. The Structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawa, E.A.; Hall, S.D.; Lohoff, F.W. Overview of the genetics of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016, 51, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappalained, J. Genetic basis of dual diagnosis. In Dual Diagnosis and Psychiatric Treatment; Kranzler, J.R., Tinsley, J.A., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger, J.I., Jr.; Foroud, T.; Flury, L.; Su, J.; Meyer, E.T.; Hu, K.; Crowe, R.; Edenberg, H.; Goate, A.; Bierut, L.; et al. Evidence for a locus on chromosome 1 that influences vulnerability to alcoholism and affective disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, T.; Edenberg, H.J.; Goate, A.; Williams, J.T.; Rice, J.P.; Van Eerdewegh, P.; Foroud, T.; Hesselbrock, V.; Schuckit, M.A.; Bucholz, K.; et al. Genome-wide search for genes affecting the risk for alcohol dependence. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998, 81, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroud, T.; Edenberg, H.J.; Goate, A.; Rice, J.; Flury, L.; Koller, D.L.; Bierut, L.J.; Conneally, P.M.; Nurnberger, J.I.; Bucholz, K.K.; et al. Alcoholism susceptibility loci: Confirmation studies in a replicate sample and further mapping. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, J.; Cubin, M.; Tiwari, H.; Wang, C.; Bomhra, A.; Davidson, S.; Miller, S.; Fairburn, C.; Goodwin, G.; Neale, M.C.; et al. Linkage analysis of extremely discordant and concordant sibling pairs identifies quantitative-trait loci that influence variation in the human personality trait neuroticism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 72, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gelernter, J.; Page, G.P.; Bonvicini, K.; Woods, S.W.; Pauls, D.L.; Kruger, S. A chromosome 14 risk locus for simple phobia: Results from a genomewide linkage scan. Mol. Psychiatry 2003, 8, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.W.; Huezo-Diaz, P.; Williamson, R.J.; Sterne, A.; Purcell, S.; Hoda, F.; Cherny, S.S.; Abecasis, C.R.; Prince, M.; Gray, J.A.; et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis of a composite index of neuroticism and mood-related scales in extreme selected sibships. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Donadon, M.F.; Osório, F.L. Personality traits and psychiatric comorbidities in alcohol dependence. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2016, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L.E.; Ostacher, M.; Ballon, J. How genome-wide association studies (GWAS) made traditional candidate gene studies obsolete. Neuropsychopharmacol 2019, 44, 1518–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnbaum, R.; Weinberger, D.R. Pharmacological implications of emerging schizophrenia genetics. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol 2020, 40, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.J.; Zeiss, C.; Chew, E.Y.; Tsai, J.Y.; Sackler, R.S.; Haynes, C.; Henning, A.K.; SanGiovanni, J.P.; Mane, S.M.; Bracken, M.B.; et al. Complement factor H polymorphism in age- related macular degeneration. Science 2005, 308, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visscher, P.M.; Wray, N.R.; Zhang, Q.; Sklar, P.; McCarthy, M.I.; Brown, M.A.; Yang, J. 10 years of GWAS discovery: Biology, function, and translation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palk, A.C.; Dalvie, S.; de Vries, J.; Martin, A.R.; Stein, D.J. Potential use of clinical polygenic risk scores in psychiatry—ethical implications and communicating high polygenic risk. Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.R.I.; Gaspar, H.A.; Bryois, J. The genetics of the mood disorder spectrum: Genome-wide association analyses of over 185,000 cases and 439,000 controls. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 88, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Terzlaf, J.M.; Alk, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.B.; Aasland, O.G.; Babor, T.F.; de la Fuente, J.R.; Grant, M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption—II. Addiction 1993, 88, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripke, S.; Wray, N.R.; Lewis, C.M.; Hamilton, S.P.; Weissman, M.M.; Breen, G.; Byrne, E.M.; Blackwood, D.H.R.; Boomsma, D.I.; Cichon, S.; et al. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, N.R.; Ripke, S.; Mettheisen, M.; Trzaskowski, M.; Byrne, E.M.; Abdellaoui, A.; Adams, M.J.; Agerbo, E.; Air, T.M.; Andlauer, T.M.F.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklar, P.; Ripke, S.; Scott, L.J.; Andreassen, O.A.; Cichon, S.; Craddock, N.; Edenberg, H.J., Jr.; Nurnberger, J.I.; Rietschel, M.; Blackwood, D.; et al. Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydall, J.; Bass, N.J.; McQuillin, A.; Lawrence, J.; Anjorin, A.; Kandaswamy, R.; Pereira, A.; Guerrini, I.; Curtis, D.; Vine, A.E.; et al. Confirmation of prior evidence of genetic susceptibility to alcoholism in a genome-wide association study of comorbid alcoholism and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr. Genet. 2011, 21, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.; Drgon, T.; Liu, Q.R.; Walther, D.; Edenberg, H.; Rice, J.; Foroud, T.; Uhl, G.R. Pooled association genome scanning for alcohol dependence using 104 268 SNPs: Validation and use to identify alcoholism vulnerability loci in unrelated individuals from the collaborative study on the genetics of alcoholism. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2006, 141B, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerner, B.; Lambert, C.G.; Muthén, B.O. Genome-wide association study in bipolar patients stratified by co-morbidity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, A.C.; Aliev, F.; Bierut, L.J.; Bucholz, K.K.; Edenberg, H.; Hesselbrock, V.; Kramer, J.; Kuperman, S.; Nurnberger, J.I.; Schuckit, M.A.; et al. Genome-wide association study of comorbid depressive syndrome and alcohol dependence. Psychiatr. Genet. 2012, 22, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, S.I.; McQuillin, A.; Marks, M.; Hunt, S.P.; Stanford, S.C.; Lydall, G.J.; Morgan, M.Y.; Asherson, P.; Curtis, D.; Gurling, H.M.D. Genetic association of the Tachykinin Receptor 1 TACR1 gene in bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and the alcohol dependence syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet.Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2014, 165B, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, D.F.; Le-Niculescu, H.; Frank, J.; Ayalew, M.; Jain, N.; Kirlin, B.; Learman, R.; Winiger, E.; Rodd, Z.; Shekhar, A.; et al. Genetic risk prediction and neurobiological understanding of alcoholism. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treutlein, J.; Cichon, S.; Ridinger, M.; Wodarz, N.; Soyka, M.; Zill, P.; Maier, W.; Moessner, R.; Gaebel, W.; Dahmen, N.; et al. Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.; Cichon, S.; Treutlein, J.; Ridinger, M.; Mattheisen, M.; Hoffmann, P.; Herms, S.; Wodarz, N.; Soyka, M.; Zill, P.; et al. Genome-wide significant association between alcohol dependence and a variant in the ADH gene cluster. Addict. Biol 2012, 17, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.D.; Le-Niculescu, H.; Koller, D.L.; Green, S.D.; Lahiri, D.K.; McMahon, F.J.; Nurnberger, J.I., Jr.; Niculescu, A.B., III. Coming to grips with complex disorders: Genetic risk prediction in bipolar disorder using panels of genes identified through convergent functional genomics. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 153B, 850–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le-Niculescu, H.; Case, N.J.; Hulvershorn, L.; Patel, S.D.; Bowker, D.; Gupta, J.; Bell, R.; Edenberg, H.J.; Tsuang, M.T.; Kuczenski, R.; et al. Convergent functional genomic studies of omega-3 fatty acids in stress reactivity, bipolar disorder and alcoholism. Transl. Psychiatry 2011, 1, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.E.; Agrawal, A.; Bucholz, K.K.; Hartz, S.M.; Lynskey, M.T.; Nelson, E.C.; Bierut, L.J.; Bogdan, R. Associations between polygenic risk for psychiatric disorders and substance involvement. Front. Genet. 2016, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierut, L.J.; Agrawal, A.; Bucholz, K.K.; Doheny, K.F.; Laurie, C.; Pugh, E.; Fisher, S.; Fox, L.; Howells, L.; Bertelsen, S.; et al. A genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5082–5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierut, L.J.; Madden, P.A.; Breslau, N.; Johnson, E.O.; Hatsukami, D.; Pomerleau, O.F.; Swan, G.E.; Rutter, J.; Bertelsen, S.; Fox, L.; et al. Novel genes identified in a high-density genome wide association study for nicotine dependence. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierut, L.J.; Strickland, J.R.; Thompson, J.R.; Afful, S.E.; Cottler, L.B. Drug use and dependence in cocaine dependent subjects, community-based individuals, and their siblings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 95, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.M.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Kranzler, H.R.; Ma, L.; Zhou, H.; Liu, X.; Kramer, J.; Kuperman, S.; Edenberg, H.J.; Rice, J.O.; et al. Polygenic scores for major depressive disorder and risk of alcohol dependence. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelernter, J.; Sherva, R.; Koesterer, R.; Almasy, L.; Zhao, H.; Kranzler, H.R.; Farrer, L. Genome-wide association study of cocaine dependence and related traits: FAM53B identified as a risk gene. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuehrlein, B.S.; Mota, N.; Arias, A.J.; Trevisan, L.A.; Kachadouran, L.K.; Krystal, J.H.; Southwick, S.M.; Pietrzak, T.H. The burden of alcohol use disorders in US military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Addiction 2016, 111, 1786–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Polimanti, R.; Yang, B.; Wang, Q.; Shizhong, H.; Sherva, R.; Nuñez, Y.Z.; Zhao, H.; Farrer, L.A.; Kranzler, H.R.; et al. Genetic risk variants associated with comorbid alcohol dependence and major depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okbay, A.; Baselmans, B.; De Neve, J.E.; Turley, P.; Nivard, M.G.; Fontana, M.A.; Meddens, F.W.; Linner, R.K.; Rietveld, C.A.; Derringer, J.; et al. Genetic variants associated with subjective well-being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome-wide analyses. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginsson, G.R.; Inganson, A.; Euesden, J.; Bjornsdottir, G.; Olafsson, S.; Sigurdson, E.; Oskarsson, H.; Tyrfingsson, T.; Runarsodottir, V.; Hansdottir, I.; et al. Polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder associate with addiction. Addict. Biol. 2018, 23, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014, 511, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muench, C.; Schwandt, M.; Jung, J.; Cortes, C.R.; Momenan, R.; Lohoff, F.W. The major depressive disorder GWAS-supported variant rs10514299 in TMEM161B-MEF2C predicts putamen activation during reward processing in alcohol dependence. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otowa, T.; Hek, K.; Lee, M.; Byrne, E.M.; Mirza, S.S.; Nivard, M.G.; Bigdeli, T.; Aggen, S.H.; Adkins, D.; Wolen, A.; et al. Metaanalysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, J.C.; Streit, F.; Treutlein, J.; Ripke, S.; Witt, S.H.; Strohmaier, J.; Degenhardt, F.; Forstner, A.J.; Hoffmann, P.; Soyka, M.; et al. Shared genetic etiology between alcohol dependence and major depressive disorder. Psychiatr. Genet. 2018, 28, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, R.K.; Polimanti, R.; Johnson, E.C.; McClintick, J.N.; Adams, M.J.; Adkins, A.E.; Aliev, F.; Bacanu, S.A.; Batzler, A.; Bertelsen, S.; et al. Transancestral GWAS of alcohol dependence reveals common genetic underpinnings with psychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1656–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polimanti, R.; Peterson, R.E.; Ong, J.S.; MacGregor, S.; Edwards, A.; Clarke, T.K.; Frank, J.; Gerring, Z.; Gillespie, N.A.; Lind, P.A.; et al. Evidence of causal effect of major depression on alcohol dependence: Findings from the psychiatric genomics consortium. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.; Sudlow, C.; Downey, P.; Peakman, T.; Danesh, J.; Elliott, P.; Callacher, J.; Green, J.; Matthews, P.; Pell, J.; et al. UK Biobank: Current status and what it means for epidemiology. Health Policy Technol. 2012, 1, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Magaña, J.J.; Gonzalez-Castro, T.B.; Genís-Mendoza, A.D.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; Saucedo-Uribe, E.; Rodriguez-Mayoral, O.; Lanzagorta, N.; Escamilla, M.; Macías-Kauffer, L.; et al. Exploratory analysis of polygenic risk scores for psychiatric disorders: Applied to dual diagnosis. Rev. Invest. Clin. 2019, 71, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, S.M.C.; Funkhouser, S.A.; Johnson, E.C.; Hoeffer, C.; Ehringer, M.A.; Evans, L.M. Differential shared genetic influences on anxiety with problematic alcohol use compared to alcohol consumption. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purves, K.L.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Meier, S.M.; Rayner, C.; Davis, K.A.S.; Cheesman, R.; Bækvad-Hansen, M.; Børglum, A.D.; Cho, S.W.; Deckert, J.J.; et al. A major role for common genetic variation in anxiety disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 3292–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Roige, S.; Palmer, A.A.; Fontanillas, P.; Elson, S.L.; Adams, M.J.; Howard, D.M.; Mclntosh, A.M.; Clarke, T.K. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in two population-based cohorts. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Jiang, Y.; Wedow, R.; Li, Y.; Brazel, D.M.; Chen, F.; Vrieze, S. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Drgon, T.; McMahon, F.J.; Uhl, G.R. Convergent genome wide association results for bipolar disorder and substance dependence. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2009, 150B, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenberg, H.J.; Xuei, X.; Chen, H.; Tian, H.; Wetherill, L.F.; Dick, D.M.; Almasy, L.; Bierut, L.; Bucholz, K.K.; Goate, A.; et al. Association of alcohol dehydrogenase genes with alcohol dependence: A comprehensive analysis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoch, M.A.; Hodgkinson, C.A.; Yuan, Q.; Shen, P.H.; Goldman, D.; Roy, A. The influence of GABRA2, childhood trauma, and their interaction on alcohol, heroin, and cocaine dependence. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Gurling, H. The D2 dopamine receptor gene and alcoholism: A genetic effect on the liability of alcoholism. J. R. Soc. Med. 1994, 87, 400–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joe, K.H.; Kim, D.J.; Park, B.L.; Yoon, S.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, T.S.; Cheon, Y.H.; Gwon, D.H.; Cho, S.N.; Lee, H.W.; et al. Genetic association of DRD2 polymorphisms with anxiety scores among alcohol-dependent patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 371, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.M.; Adams, M.J.; Clarke, T.K.; Hafferty, J.D.; Gibson, J.; Shiali, M.; McIntosh, A.M. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci 2019, 22, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procopio, D.O.; Saba, L.M.; Walter, H.; Lesch, O.; Skala, K.; Schlaff, G.; Tabakoff, B. Genetic markers of comorbid depression and alcoholism in women. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesch, O.M.; Walter, H. Subtypes of alcoholism and their role in therapy. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl 1996, 31, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenberg, H.D.; Koller, D.L.; Xiaoling, X.; Wetherill, L.; McClintick, J.N.; Almasy, L.; Bierut, L.J.; Bucholz, K.K.; Goate, A.; Aliev, F.; et al. Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence implicates a region on chromosome 11. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 34, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosheva, M.; Serretti, A.; Stukalin, Y.; Fabbri, C.; Hagin, M.; Horev, S.; Mantovani, V.; Bin, S.; Matticcio, A.; Nivoli, A.; et al. Association between CANCA1C Gene rs1034936 polymorphism and alcohol dependence in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 261, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, K.; Almasy, L.; Knowles, E.E.M.; Kent, J.W.; Curran, J.E.; Dyer, T.D.; Göring, H.H.H.; Olvera, R.L.; Fox, P.T.; Pearlson, G.D.; et al. Genome-wide significant loci for addiction and anxiety. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 36, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionel, A.C.; Tammimies, K.; Vaags, A.K.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Ahn, J.W.; Merico, D.; Noor, A.; Runke, C.K.; Pillalamirri, V.K.; Carter, M.T.; et al. Disruption of the ASTN2/TRIM32 locus at 9q33.1 is a risk factor in males for autism spectrum disorders, ADHD and other neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 2752–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, M.; Tinsley, C.L.; Benson, M.A.; Blake, D.J. TRIM32 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for dysbindin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 2344–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaleo, F.; Weinberger, D.R. Dysbindin and schizophrenia: It’s dopamine and glutamate all over again. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khantzian, E.J. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 1985, 142, 1959–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, G.; Coin, L.J.; Lourdusamy, A.; Charoen, P.; Berger, K.H.; Stacey, D.; Desrivières, S.; Aliev, F.; Khan, A.A.; Amin, N.; et al. Genome-wide association and genetic functional studies identidy autism susceptibility candidate 2 gene (AUTS2) in the regulation of alcohol consumption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7119–7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, K.; Nagai, T.; Shan, W.; Sakamoto, A.; Abe, M.; Yamazaki, M.; Sakimura, K.; Yamada, K.; Hoshini, M. Heterozygous disruption of autism susceptibility candidate 2 causes impaired emotional control and cognitive memory. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Cheng, Z.; Bass, N.; Krystal, J.H.; Farrer, A.; Kranzler, H.R.; Gelernter, J. Genome-wide association study identifies glutamate ionotropic receptor GRIA4 as a risk gene for comorbid nicotine dependence and major depression. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enoch, M.A.; Rosser, A.A.; Zhou, Z.; Mash, D.C.; Yuan, Q.; Goldman, D. Expression of glutamatergic genes in healthy humans across 16 brain regions; altered expression in the hippocampus after chronic exposure to alcohol or cocaine. Genes Brain Behav. 2014, 13, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nicola, M.; Moccia, L.; Ferri, V.L.; Panaccione, I.; Janiri, L. Alcoholism in bipolar disorder: An overview of epidemiology, common pathogenic pathways, course of disease, and implications for treatment. In Neuroscience of Alcohol; Preedy, V.R., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.P.; Stein, M.B.; Kranzler, H.R.; Yang, B.Z.; Farrer, L.A.; Gelernter, J. The α-endommanosidase gene (MANEA) is associated with panic disorder and social anxiety disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipilä, T.; Kananen, L.; Greco, D.; Donner, J.; Silander, K.; Terwilliger, J.D.; Auvinen, P.; Peltonen, L.; Lönnqvist, J.; Pirkola, S.; et al. An association analysis of circadian genes in anxiety disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanagel, R.; Pendyala, G.; Abarca, C.; Zghoul, T.; Sanchis-Segura, C.; Magnone, M.C.; Lascorz, J.; Depner, M.; Holzberg, D.; Soyka, M.; et al. The clock gene Per2 influences the glutamatergic system and modulates alcohol consumption. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Niculescu, H.; McFarland, M.J.; Ogden, C.A.; Balaraman, Y.; Patel, S.; Tan, J.; Rodd, Z.A.; Paulus, M.; Geyer, M.A.; Edenberg, H.J.; et al. Phenomic, convergent functional genomic, and biomarker studies in a stress-reactive genetic animal model of bipolar disorder and co-morbid alcoholism. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008, 147B, 134–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, J.M.; Nurnberger, J.L. Polygenic risk scores in psychiatry: Will they be useful for clinicians? F1000Research 2019, 8, F1000 Faculty Rev-1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett, J.T.; Arranz, M.J.; Munro, J.; Osbourn, S.; Kerwin, R.W.; Collier, D.A. Association analysis of the 5-HT5A gene in depression, psychosis and antipsychotic response. Neuro Rep. 2000, 11, 2017–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosifova, A.; Mushiroda, T.; Stoianov, D.; Vazharova, R.; Dimova, I.; Karachanak, S.; Zaharieva, I.; Milanova, V.; Madjirova, N.; Gerdjikov, I.; et al. Case-control association study of 65 candidate genes revealed a possible association of a SNP of HTR5A to be a factor susceptible to bipolar disease in Bulgarian population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 117, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).