Abstract

Heritage education is understood to be multifaceted. The way it is approached and conceived in formal educational contexts can differ according to the emphasis policy makers wish to establish. In Flanders, a region within Belgium, a curriculum reform took shape over the last seven years. This paper explores the recently introduced curriculum in Flemish secondary education, in light of Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. The main aim is to investigate how heritage education and sustainability fit into the newly developed curriculum framework, and the way they are interlinked on a conceptual level. The qualitative research draws on a screening of policy texts, learning outcomes, and additional interviews with policy advisors. The results show that heritage education is implicitly present. Cross-curricular opportunities are built-in and can be linked to (a) cultural awareness and expression; (b) historical consciousness; (c) citizenship; and (d) intercultural communication. Sustainable development, and more specific ESD, anchored itself firmly and more explicitly into the framework as a transversal key competence as well. However, clear connections to heritage education are not set up in the learning outcomes.

1. Introduction

When reflecting on the use of heritage in educational contexts, it is mostly linked to history education. However, heritage is not about the past, but about the present, according to David Lowenthal [1]. Instead, it can be interpreted as a social construct. Communities in the present preserve and give meaning to certain (local) aspects of the past. Therefore, in educational contexts, the dichotomy between history and heritage does not need to be problematic or conflicting. Heritage can be conceived as a didactic instrument. For example, in history lessons, it could be used when critically assessing historical sources. Nonetheless, its value as an instrument may not be limited to one subject, or be recognised as useful only for the cognitive domain. When heritage is interpreted as a social construct in the present, other aspects could come to mind, such as sustainability issues. Herein, the affective domain could play a valuable role as well.

Heritage education is understood to be multifaceted, which means there are many aspects to explore. By introducing the use of heritage into educational curricula, students could get acquainted not only with temporal changes but also with spatial ones [2]. It ranges from small objects, monuments or local traditions to large-scale expressions, practices, buildings or landscapes. From this diverse perspective, it contains a variety of possibilities to sharpen the minds and shape the behaviour of students on many relevant aspects of human life, such as sociocultural, economic, civic, or environmental issues [3,4,5,6,7].

Therefore, in the spectrum of educational opportunities, heritage mostly encompasses links to concepts like citizenship, cultural awareness, intercultural communication, sustainability, or historical thinking [8,9]. However, heritage, and the way it is approached and conceived into formal educational contexts, can differ according to the emphasis policy makers wish to establish.

In 1998, the Council of Europe (CoE) defined heritage education as “a teaching approach based on cultural heritage, incorporating active educational methods, cross-curricular approaches, a partnership between the fields of education and culture and employing the widest variety of modes of communication and expression [10] (p. 31).” Moreover, concerning its implementation, the recommendation of the CoE stated that heritage education is cross-curricular by its very nature and should be promoted into different school subjects at all levels and in all types of teaching. An ambitious aspiration, at the least.

Over the last two decades, heritage education—and scientific research about it—has evolved significantly, and it gradually succeeded in consolidating itself as a discipline [11]. Nevertheless, as Van Boxtel, Grever, and Klein pointed out in 2016, the way heritage education is practiced in European Countries remains mostly unknown [12].

By creating curricula, policy makers can select to what extent the aforementioned spectrum of heritage education comes into play and relates to other subjects. More importantly, it needs to be stressed that the conceptual choices made on this level significantly affect the way heritage education is operationalised on lower levels by schools and teachers. For example, in Spain, research revealed that official curricula and textbooks for teachers deal with heritage in an unconnected manner [13]. This could render students to believe the study of heritage as something residual [14]. In Slovenia, attempts were made to examine the curricular connections between heritage education and fine art, after which they were put to the test in classroom practice in primary education [15].

Moreover, policy makers also have to keep the international frameworks from above in mind. From this perspective, the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, which came into effect on 1 January 2016, poses a new challenge [16]. It has to be implemented at the policy level by the governments of the member states [17]. Thus, not only a coherent and well-balanced vision on heritage education has to be elaborated, but, in addition, it ideally needs to be connected to the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) as well.

The main research question is to investigate how heritage education and sustainability fit into the newly developed curriculum framework for secondary education in Flanders, and in what way they are interlinked on a conceptual level. Moreover, in order to pursue qualitative heritage education, this paper wants to go further and makes recommendations to operationalise the conceptual framework into classroom practice by the educational providers, schools, and teachers.

Traditionally in Flanders, the choice of study is delayed until the start of the second grade of secondary education. This means that between the age of 14 to 16 years old, students need to make a choice that will determine their further school career. So the first grade consists of a basic formation in which students, usually from 12 to 14 years old, receive more or less the same fundamentals [18]. This paper investigates the recently introduced curriculum in Flanders secondary education, in light of Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. The new learning outcomes for the first year of the first grade of secondary education came into effect on 1 September 2019. The second year followed precisely one year later. This means only the learning outcomes for the first grade, which form a coherent set, could be examined in this paper. The ones meant for the second and third grade were drafted by the government but had yet to be approved by the Flemish Parliament. They will be involved in this study when relevant, for example, to explore the vertical integration of sustainability issues or heritage into the curriculum. However, due to their preliminary status, no definitive conclusions can be drawn for the second and third grade. Consequently, the scope of this study is limited to this broad first grade.

2. Literature Review

2.1. General Context

Belgium became independent in 1830, with its secession from the Netherlands. A few months later, the national congress adopted a constitution, which turned the new-made state into a parliamentary monarchy. Despite favouring the Catholic Church, the constitution was considered, at that time, to be progressive as it enclosed considerate liberal aspects. Leopold I, of the dynasty of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, was appointed to fulfil the role of king. The country kept this state structure until 1970, when tensions between the two primary language communities led to the first state reform. Three cultural communities were established: a Dutch, French, and German-speaking community, each with its own cultural autonomy. During the second and third reform, and in response to the request for more economic autonomy, three regions were added: The Flemish, the Walloon, and the Brussels-Capital regions [19].

In the present, and after additional reforms in 1993, 2001, and 2011, Belgium has a federal state structure consisting of three regions and three communities, each with its own legislative body and government. In Flanders, the community and the region were combined straight away into one entity, thus creating one Flemish parliament and one Flemish government. Decisions on compulsory education, such as the minimum and maximum age of pupils, are taken by the federal government. In compulsory education, the minimum age is set at five years old and the maximum age at 18 years old. However, the Flemish community has competence for cultural affairs and education, which makes them legal responsibilities within the geographical boundaries of the Dutch-language area and the bilingual area Brussels-Capital [18]. The implementation of heritage policies lies in the hands of the Flemish government and its administrations. However, due to the prior division into regions and communities, immovable heritage (such as monuments, archaeological sites and landscapes) in Flanders is accommodated under the supervision of the department of environment, while cultural heritage (tangible/moveable and intangible cultural heritage) falls under the department of culture, youth and media.

The policy area of education and training comprises various departments and agencies. Developing learning outcomes is the responsibility of the Agency for Higher Education, Adult Education, Qualifications, and Study Grants (AHOVOKS), according to the framework adopted by the Flemish government and parliament. Nonetheless, putting them into practice rests in the hands of the educational providers. They have the ability to expand these learning outcomes, which are conceived as minimum goals, and provide them with their personal operational emphasis.

In the formal public education system, secondary education usually takes place after six years of primary education and starts from the age of 12 years old. It consists of three stages, each divided into two school years. The first grade commences with two possible inflows (A or B), based on the received certificate at the end of primary education. It provides a broad basic education. The main objective is to orient students and prepare them for a well-considered choice in the second grade.

According to the newly approved structure of the formal education system, the study options in the second (14–16 years old) and third grade (16–18 years old) are divided into three finalities. The first prepares pupils for higher education, be it academic or professional. The second leads up to the job market. The last can be seen as an intermediate choice and focuses both on preparation for higher education or the job market. Pupils can select a specific field of study based on a matrix, wherein the eight study domains, educational forms, and finalities are organised [20]. The eight study domains are:

- Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)

- Economy and organization

- Art and creation

- Language and culture

- Society and wellbeing

- Sports

- Agriculture and horticulture

- Food and hospitality

2.2. Context of Heritage Education in Flanders

In the case of Flanders, only a few studies have been carried out on the implementation of heritage education. In 2007, a large-scale field study on heritage education was carried out by the Xios Hogeschool Limburg and the University of Antwerp. The report described heritage education as “any form of education that is based on ‘traces in the present from the past’ and which embed these in a context that is based on knowledge and/or can bring about an experience that refers to the past, in other words, a heritage experience [21] (p. 27).” A definition that not only emphasises a link with the cognitive domain, but with the affective domain—specific to heritage education—as well.

The conclusion stated that heritage education was incorporated in the learning objectives set up by the Flemish Government, especially in primary and secondary education. However, significantly less attention was paid to it in pre-primary and special education. More importantly, the study revealed a lack of knowledge about heritage (education) among school teachers and an inconsistent cross-curricular approach. The CoE’s ambitious aspirations from ten years earlier seemed not yet embedded.

These recommendations acted as a starting point for future policy. Furthermore, during the school year 2006–2007, Anne Bamford, then professor at the Wimbledon School of Arts, was appointed by the ministers of education and culture [22]. The aim was to chart the scope and quality of arts and cultural education in Flanders. In a broad sense, cultural education refers to reflecting on cultural expressions in an educational context. Heritage education, together with art-, literature-, and media education, is part of this inclusive term [23]. The results of the evaluative study showed that cultural education was insufficiently integrated into the formal education system. Specifically on heritage education, which is conceptually embedded into cultural education, the report stated it received relatively little attention and was marginalised in the curriculum [22].

These studies were based on previous curricula and learning outcomes. Although, at that time, education for sustainable development (ESD) had made its appearance, neither reports mention any traces of sustainability issues [21,22]. This means heritage education and ESD were not yet interconnected, at least not on a conceptual level in Flanders. Nonetheless, heritage and its dynamic nature can play a crucial role in developing a critical mind [24].

More specifically, one of its main interests is enabling young people to link local and familiar problems to more global issues. In educational contexts (formal, nonformal, or informal) it can contribute to shaping attitudes, such as learning to respect, appreciate, and reflect on what is passed on by previous generations. From this perspective, cultural aspects of life can lie at the base of environmental issues. Nevertheless, heritage is inherited from the past but shaped by the present. Learning to look at it as a dynamic social construct means accepting it is continuously in motion and negotiable. It is not only about learning to ask questions, such as “Why do people in our neighbourhood value certain aspects of the past and why?” but also “How can we come up with solutions to preserve this valuable heritage with respect for the environment and each other?” Therefore, achieving a sustainable and inclusive environment, both locally and globally, and overcoming social, economic, or environmental inequalities through dialogue based on well-argued opinions is at the heart of heritage education. Have these opportunities been seized in the recent curriculum reform in Flanders?

2.3. The Curriculum Reform

2.3.1. The Sixteen Decretal Key Competences

Over the course of the last eight years, the Flemish Government took the initiative to reform secondary education. At the base lies a masterplan, submitted and discussed in June 2013 in the Flemish parliament [25]. In the following years, a new curriculum framework and associated learning outcomes were elaborated. The output of these reform plans is gradually being introduced into the formal secondary education system.

Prior to developing the curriculum reform at the end of 2015, the education committee of the Flemish parliament called in Levuur, an organisation that consists of consultants and coaches specialised in citizen participation and stakeholder management [26]. The aim was to create a broad social debate about the learning outcomes. What should be taught at school? Teachers, pupils, parents, and the education sector in general were involved in this participative process. Moreover, strategic advisory councils debated on additional recommendations. The final report drew together all the input and formed the base for the curriculum reform. Inspiration was also sought in the Netherlands, with a hearing in the Flemish parliament on the Dutch Platform 2032 on educational recommendations and the SLO, the national centre of the Netherlands for curriculum development [27]. Finally, on 17 January 2018, the plenary meeting approved the decree on the reform of secondary education.

The decree provided a general framework in which the new learning outcomes could take shape. The curriculum reform was structured around a set of key competences, roughly inspired by the recommendations on key competences for lifelong learning by the European parliament and council in 2006. Within this framework, competences were conceived as a combination of knowledge, skills, and attitudes and acted as a reference for future policy of its member states [28]. However, the Flemish community not only followed these recommendations, it also expanded the European key competences to sixteen, which, in their turn, formed the base for the new learning outcomes for secondary education.

Decretal key competences (kc):

- Competences in the field of physical, mental and emotional awareness, and in the field of physical, mental and emotional health

- Competences in Dutch

- Competences in other languages

- Digital competence and media literacy

- Social-relational competences

- Competences in mathematics, exact sciences and technology

- Citizenship competences including competences for living together

- Competences related to historical consciousness

- Competences related to spatial awareness

- Competences in sustainability

- Economic and financial competences

- Juridical competences

- Learning competences including research competences, innovative thinking, creativity, problem solving and critical thinking, systems thinking, information processing and collaboration

- Self-awareness and self-expression, self-direction and flexibility

- Development of initiative, ambition, entrepreneurship, and career competences

- Cultural awareness and expression

These sixteen key competences act as a conceptual framework for building up the learning outcomes. However, it has to be stated that the key competences and learning outcomes are not directly linked to courses. In Flanders, the educational providers decide which competences have to be achieved in a course or cluster of courses. They also have the authority to expand or reformulate the learning outcomes set out by the Flemish government, according to their own identity and educational emphasis. On a lower level, it is the school boards (organising bodies) that make the connection between the expected learning outcomes and the (cluster of) courses [29]. Teachers have to follow the curriculum elaborated by the educational provider under which their school operates. How the curriculum is transferred into classroom practice, for example, which didactic choices and evaluation methods to use, remains the responsibility of the teachers.

2.3.2. The Development Process of the Learning Outcomes

The Flemish government takes on the responsibility of developing learning outcomes valid for primary (6–12 years old) and secondary education (12–18 years old). After the parliamentary approval in January 2018, it appointed seven separate committees, staffed by experts in a particular field, university professors, policy workers, researchers, representatives of the educational providers, and experienced teachers. Their aim was to create learning outcomes for secondary education that could be fitted into the framework of these sixteen key competences.

In order to increase the social relevance, the public debate and inquiry ‘Van LeRensbelang’ was taken into account. Here, in the section ‘approaching art and culture’, the societal relevance of cultural expressions and its connections with (collective) cultural identities was underscored. Nonetheless, the need for heritage education in particular, did not come forward. Consequently, relevant stakeholder organisations concerning heritage were not involved during the development process of learning outcomes [26].

On the other hand, an entire section was dedicated to sustainable development. When sustainability issues came to mind, the report mostly mentioned links with the physical world and how to deal with it with care. According to the survey, this should be addressed mainly in the subject of geography. Possible connections between heritage education and sustainable development are not highlighted.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Phases

In light of the question and aims, a qualitative research design was selected. First, the curriculum analysis was performed to identify indicators of heritage education in the curriculum framework. Hence the reform has just recently been introduced, no prior research on the role of heritage education in it has been conducted. The portal website established by the Flemish administration provided the official learning outcomes and guidance notes for the screening process [19]. The indicators were systematically recorded. In a second step, the same process was followed for sustainable development.

In order to contextualise the findings and to fully comprehend the curriculum framework and the reform, interviews were set up with educational policy advisors (N = 4) and members of the development committee of the learning outcomes (N = 2). In addition, staff members of FARO were interviewed (N = 4). In Flanders, this organisation acts as an interface centre for the heritage sector, mediating between local, provincial, regional, and national governments, and local and national heritage organisations, international networks, the academic world, and civil society. FARO is active in the field of heritage education, and recently set up projects to promote local heritage and partnership in primary (6–12 years old) and secondary schools (12–18 years old). For these (pilot) projects, they worked in collaboration with the team responsible for education for sustainable development (Flemish department of environment), and CANON Cultuurcel (Flemish department of education and training), which is a liaison agency between the cultural and educational policy areas [30,31]. Members of the steering group responsible for this project were included in the interviews (N = 3) as well.

The selection of the participants was nonprobabilistic sampling, since they were selected by the researcher based on their relevant policy domain or expertise (purposive sampling). A much raised concern of purposive sampling is its inherent bias. However, despite the intentional bias, it can provide reliable data [32]. The participants took part in a semistructured online interview between 6 April and 26 May 2020. The answers were manually processed, incorporated into the previous findings of the curriculum analysis, and presented again to the participants within a short time frame, in order to provide feedback on the interpretation of the research results.

In a final step, possible connections between heritage education and sustainable development were explored based on the theoretical framework, and recommendations that proved to be relevant were presented.

3.2. Overall Research Design

This study is part of a research project that aims to investigate the didactic potential and challenges of heritage education in secondary education in Flanders, and specifically its relation to history education. A literature review and curriculum analysis, included in this study, is a starting point. In the next phase of the project, the theoretical framework will be explored and discussed with relevant stakeholders and experts. Finally, good practices will be collected, developed, and tested in various classroom settings through an action research approach, contributing to an evidence based practice.

4. Results

4.1. In Search of Heritage Education

The concept of heritage could be dispersed over multiple key competences. Historical consciousness (kc 8) and cultural awareness and expression (kc 16) seem to be the most obvious ones to look for traces of heritage education in the new curriculum. At least, when the approach used in Dutch research contexts of Van Boxtel, Grever, and Klein is pursued. According to them, heritage education refers to “educational practices in which heritage is a primary instructional resource for teaching and learning with the aim to improve students’ understanding of history and culture [12] (p. 6).”

After a thorough analysis of the learning outcomes of the first grade of secondary education for the key competence on cultural awareness and expression, it appears that heritage, in any form, is not explicitly included. Instead, the generic concept of ‘art and cultural expressions’ is used [19]. In terms of content, the guidance note does not set any specific conditions. It does, however, mention several didactic and thematic suggestions: “Art and cultural expressions such as landscape, dance, song, game, film, clothing, graffiti. (…). In any case, the number of subjects of art and cultural expressions is endless: birth, death, love, history, the everyday, rituals, art itself [33].”

To implement the above suggestions on cultural education (of which art and heritage education are part), the cultural theory proposed by Dutch cognitive researcher Barend Van Heusden is employed. This learning theory, ‘culture in the mirror’, uses four cognitive strategies: perception, imagination, conceptualisation, and analysis. It centres around reflecting on one’s own cultural expressions as well as of others. Thus, the theory focuses on the importance of cultural (self-) consciousness and awareness and its place at the heart of art and cultural education [34]. Here, the learning outcomes that could be related to heritage education seem to mainly focus on attitudes and skills:

- The students recognise the importance of art and cultural expressions for themselves and their own environment.

- The students express their thoughts and feelings when perceiving art and cultural expressions.

The learning theory and its potential in formal education have been intensively studied during the last decade, stimulated by the Flemish administration. These research programs aimed to develop and test a theory-driven framework for the integration of culture into the curricula of precompulsory and compulsory education [34,35]. To familiarise schools and teachers with its implementation, a training and learning network was set up by the liaison agency (between the policy areas of culture and education), CANON Cultuurcel. Although the theory is undoubtedly suitable for cultural awareness, the social, historical, or environmental aspects of heritage education seem to remain somewhat underexposed within this learning theory.

Consequently, heritage education could also be integrated into the decretal key competence related to kc 8. Here, the development committee elaborated four fundamentals, wherein the specific outcomes concerning historical consciousness were conceived:

- Situating historical phenomena in a historical frame of reference

- Reflecting critically with and about historical sources

- Creating a substantiated historical image based on different perspectives

- Reflecting on and interpreting the complex relationship between past, present, and future

These four generic objectives [36] form the core of the key competence on historical consciousness and are continued throughout the three grades of secondary education. The more specific learning outcomes and associated content are appointed to each of these fundamentals. They differ according to the possible inflows or finalities in the formal education system in Flanders. Heritage education, as conceived in the Dutch (and in some cases English) interpretation of the term, could be addressed in all four fundamentals. Both key competences constitute an adequate framework wherein cultural heritage is used as a means or instrument to improve students’ understanding of culture and history.

The fundamentals can be related to the concept of ‘historical thinking’. Although historical inquiry, which can be seen as a starting point of historical thinking, seems not included, it is certainly present [37]. Moreover, the fundamentals lend themselves to an inquiry-based approach, and can also be linked to the six historical concepts developed by Seixas and Morton, which, according to them, form the basics of historical inquiry [8]. Consequently, various studies have shown that heritage can be of significant value in developing historical thinking [38,39]. The concept is about insight into and reflection on the complex relationship between the present, the past and the future. This requires insight into the past itself as well as into the way perceptions about the past are formed in the present. The aim is to teach students to deal critically and in a nuanced way with historical sources and (mis)perception, and to show respect for well-argued opinions. From this perspective, historical thinking, and thus heritage education, can be linked to (critical) citizenship.

Another aspect of heritage is its significant relevance for civic education, due to a strong identity component [5]. Cultural heritage can be used or misused for national identity construction. It is, therefore, necessary to acquire a critical approach from an early age. For the key competence on citizenship including competences for living together (kc 7 in the first grade), seven fundamentals were elaborated:

- To explain the dynamics and the layers of (own) identities

- To deal with diversity in living together and working together

- To participate in an informed and substantiated dialogue with each other

- To participate actively in society, taking into account the rights and obligations of everyone within the rule of law

- To approach critically the mutual influence between social domains and developments and their impact on (global) society and the individual

- To interpret democratic decision-making at local, national, and international level

- To explain democratic principles and democratic culture as part of the modern rule of law

When analysing the learning outcomes, the ones associated with the first three fundamentals seem to be relevant for heritage education:

- The students explain the layers and dynamics of identities and their possible consequences for relationships with others. (transversal)

- The students deal respectfully and constructively with individuals and groups in a diverse society. (transversal—attitudinal)

- Students adopt strategies to deal respectfully and constructively with individuals and groups in a diverse society. (transversal)

- The students explain the mechanisms of prejudice, stereotyping, abuse of power, and peer pressure. (transversal)

- The students use strategies to arrive at constructive solutions for conflict situations. (transversal)

- The students distinguish intolerance as well as discrimination in society. (transversal)

- The students substantiate their own opinion about social events, themes, and trends with reliable information and valid arguments. (transversal)

These learning outcomes are marked as transversal, which means they acquire their value in relation to other key competences. Noteworthy however, is that the key competences on historical consciousness (kc 8) and on citizenship (kc 7) were elaborated independently from each other. Since heritage can be seen as something dynamic and negotiable, entering into a dialogue with others seems a skill of great value and relevance [24]. Besides the inherent identity and attitudinal component, these learning outcomes can also be linked to the aspect of intercultural communication in heritage education. References to it, albeit implicit, can be found in kc 2 and kc 3. Here, the significant role of language as a medium is stressed. The students are expected to have insight into language, Dutch or foreign, as a part of culture and society.

- The students act respectfully towards similarities and differences in language utterances, language varieties, and languages. (attitudinal)

- The students show an interest in cultural contexts in which foreign languages are used. (attitudinal)

The open framework was constituted in which heritage education can be integrated, based on cross-curricular approaches. However, the interviews show that relevant stakeholders of the heritage sector were not involved during the development process of the learning outcomes. Therefore, the implicit references to heritage education were conceived without the advice or expertise of heritage partners on any level. Furthermore, the key competences were elaborated independently from each other. Will the strength of heritage education, which relies on its transversal applications, be fully covered?

For example, by addressing the overcommercialisation of heritage sites, or the associated unsustainable tourism that threatens cultural practices and expressions or biodiversity, different key competences can be interlinked. Moreover, heritage educations’ spatial and temporal versatility needs to be underscored. It can be used to demonstrate cultural evolutions or introduce multiperspectivity in the past; to reflect on contemporary local or global social issues, such as cohesion and inclusion; or to contribute to a sustainable mindset for the future. In this paper, the focus lies on its connection with sustainable development. How is this relationship incorporated into the curriculum framework?

4.2. Linking Heritage Education to Sustainable Development

On the International and National Level

None of the SDGs centres around culture in an exclusive way [34]. The role of cultural heritage seems limited or underdeveloped. However, a reference can be found in SDG 11, where it is mentioned in 11.4: “Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage [40].”

As Francesca Nocca has highlighted, it is a relatively weak reference because it is not specific to cultural heritage. It deals only with the protection and safeguarding of it [41]. Here, cultural heritage is conceived as a goal. Its potential to be employed as a means in (formal, nonformal, or informal) educational contexts is ignored. Nevertheless, according to the conceptual framework of the SDGs, culture can act both as a driver and as an enabler [42]. It is recognised as a means to accelerate and achieve various development objectives.

The SDG that seems most relevant in this research on heritage education is target 4.7: “By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and nonviolence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development [43].”

Target 4.7 underpins the role of education in contributing to how a sustainable way of life and appreciation of cultural diversity has developed in the minds of students. Nonetheless, this target remains challenging to measure. The indicators mentioned are national education policies, curricula, teacher education, and student assessment. In other words, mapping the learning outcomes and the content of school curricula could prove to be useful. But unlike math or reading results, these attitudes are tough to measure. How are cultural heritage and its relation to sustainable development incorporated into the curriculum framework?

When transferring the sustainable development goals to its own policy level, the Flemish government developed a long-term strategy aligned to the SDGs, namely Vision 2050. In addition, in March 2018, the government set intermediate goals to be achieved by 2030. This framework bundles 49 objectives, in line with Agenda 2030. The Flemish government also developed transition priorities. These will function as accelerators in the realisation of Vision 2050 in the long term and also contribute to the 2030 objectives framework in the short term. Here, education is seen as an essential lever for realising this long-term perspective. Did the SDGs, and more specifically SDG 4, find their way into the development process of the learning outcomes as well?

In Curriculum Reform

The new curriculum is built around the decretal key competences, inspired by the European framework. However, the Flemish community opted to expand the European recommendations of 2006 consisting of eight competences, into a conceptual framework of sixteen competences [28]. In response to the changes in society and economy, the Council of Europe revised and updated the previous set of recommendations, highlighting the ambitions of the SDGs, and in particular SDG 4.7. This target aims to “ensure that, by 2030, all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and nonviolence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development [43]”. For the policy area of education and training, the Education 2030 Framework for Action, as adopted at the World Education Forum in May 2015, gives guidance when implementing SDG 4 in Flanders [44].

In contrast to the past, the simultaneous development of the learning outcomes within the conceptual framework offered the opportunity to focus on a coherent curriculum in Flanders. Some key competences can therefore be regarded as transversal. This means they acquire their value in relation to other key competences. How did sustainable development find its way into the framework?

Sustainability was not integrated on its own into the framework of the European key competences for lifelong learning of 2006, which served as inspiration for the task that was at hand [28]. Instead, it was incorporated into ‘social and civic competences’, ‘mathematical competence and basic competences in science and technology’, and in ‘sense of initiative and entrepreneurship’. By creating a separate key competence on sustainability (kc 10), the Flemish Community seemed to consider this a priority for students within its language area. It was conceived to function as a transversal competence. In the social debate prior to the development of the learning outcomes, considerable attention on learning about the physical world and how to carefully deal with it, came to the surface [26]. Thus, according to public opinion, schools should play a vital role in learning about our planet and its limitations in order to make responsible decisions. These expectations coincide with education for sustainable development (ESD).

Between 2009 and 2015, the Flemish Government already formulated a strategic plan to implement ESD into formal, nonformal, and informal learning [45]. An important initiative was the establishment of an ESD platform as a coordinating body to support the actors in the field, as an interface between policy and practice. Moreover, it had the ambition to stimulate all relevant partners to develop educational initiatives concerning sustainable development [45]. To further enhance the implementation of the new curriculum, a policy seminar was held in 2016. The Global Action Programme (GAP) on education for sustainable development (2015–2030) served as a reference framework. Strategic priorities were set on all five areas of the GAP. Noteworthy are the initiatives beyond formal education, which address and support communities to take on responsibility in shaping and accelerating sustainable solutions on a local scale. This priority action area proves to be relevant since heritage education relies strongly on the local contextual environment. Here, introducing familiar cultural heritage as a means to classroom practices could act as a lever to increase the relevance of the curriculum for local communities on the one hand. On the other hand, by promoting a greater sense of involvement, the quality of ESD itself will improve. The social and civic aspects of heritage education form a common ground and starting point to link local heritage manifestations and familiar sustainability challenges to more global issues. In the same way, this could also be the case for global citizenship education (GCED).

The guidance note of the reformed curriculum refers to possible connections with five key competences [33]:

- Competences in mathematics, exact sciences, and technology (kc 6)

- Citizenship competences including competences for living together (kc 7)

- Competences related to spatial awareness (kc 9)

- Economic and financial competences (kc 11)

- Development of initiative, ambition, entrepreneurship, and career competences (kc 15)

Based on these connections, sustainability appears not to be linked on a conceptual level to competences relevant for heritage education, such as cultural awareness and expression or historical consciousness.

When screening the learning outcomes on sustainability for the first grade (inflow A and B), nine learning outcomes are listed. As expected, they all fit into one of the above key competences. Cultural aspects, or heritage in particular, are not explicitly mentioned. One of the outcomes in citizenship competences including competences for living together (kc 7) states:

Critically approach the mutual influence between social domains and developments and their impact on (global) society and the individual:

- The students act sustainably in a school context. (transversal—attitudinal)

- The students explain the complexity and interdependence of sustainability issues. (transversal)

The additional information on these outcomes only stresses the relationship of sustainable development with consumption, energy, and mobility. Sustainability appears to be approached solely from an economic, scientific, spatial, and technological point of view, which corresponds to the aforementioned guidance note. Therefore, the conceptual framework does not establish a link between cultural heritage and the possible threat of technological progress. For instance, the disappearing of traditional craftsmanship duo to mass-production.

Moreover, the screening shows that the learning outcomes for the first grade refer to the three Ps (planet, profit, and people) on sustainability issues, conceived by the United Nations. However, this model underwent an international reconceptualisation and was transformed into a model with five Ps (people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership). The provisional learning outcomes for the second and third grade, which were developed in 2019 and 2020, evidently seem to be more adapted to the SDG framework. References to it are made explicitly, and the five-part model on sustainability issues is introduced. Nevertheless, the goals here remain vague and open as well. For example, in the key competence on citizenship and competences for living together, goal 7.12 is ‘expanded’:

- The students act considering sustainable development. (attitudinal)

The students are expected to act sustainably, no longer only in a school context. Nevertheless, what exactly does this encompass? The somewhat broad formulation is part of a deliberate action to conceive an open framework, due to the specific case of curriculum development in Flanders formal education system.

5. Discussion and Recommendations

Based on the screening of the curriculum of the first grade in Flanders’ secondary education, the multifaceted potential of heritage appears, at first sight, to be underdeveloped in the framework due to its lack of clear references. These results have been derived during a theoretical study of the learning outcomes. However, the additional interviews with policy advisors, members of the development committee, FARO, and CANON Cultuurcel provided more insight into the development process and opportunities of the curriculum framework. They were solely carried out to contextualise the above findings and to receive feedback from relevant experts and stakeholders in the education and heritage sector. No further analysis was implemented in this stage of the research process. The interviews showed that possibilities for heritage education are implicitly present. On the conceptual level, opportunities are built-in to integrate heritage education in a transversal way. It can be linked to (a) cultural awareness and expression; (b) historical consciousness; (c) citizenship; and (d) intercultural communication. Although in the key competence on spatial awareness the references to sustainability issues have the potential to introduce immovable heritage (such as monuments or landscapes), it seems not closely linked to heritage education, at least when assessing the learning outcomes developed for the first grade. This connection will depend on the way the geography curricula are worked out on a lower level.

Sustainable development, and more specific ESD, seems to have found its way into the reformed curriculum in Flanders secondary education. It anchored itself strongly into the framework as a transversal key competence and, therefore, can be employed in multiple disciplines and subjects. However, clear links to heritage education are not set up in the learning outcomes. On a conceptual level, sustainability is connected to (a) mathematics, exact sciences and technology; (b) citizenship; (c) spatial awareness; (d) economic and financial competences, and (e) entrepreneurship. The absence of a connection between sustainable development and cultural heritage is in line with Agenda 2030. Focusing mainly on a keyword analysis in the Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs), the report ‘Culture in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda’ stated that the cultural dimension of sustainable development lags significantly behind (between one eighth to one fifth of) the other three recognised dimensions (the social, economic and environmental) [42].

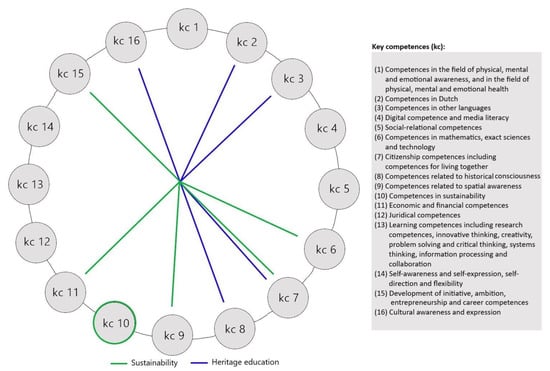

Both heritage education (implicit) and sustainability (explicit) are conceptualised as transversal in the curriculum. Figure 1 presents a visualisation of their mutual relation. They are not interlinked on this conceptual level. However, it has to be stressed, the ESD portal of the Flemish administration mentions the possible connections to cultural and heritage education. In the curriculum framework, overlap can be found in the key competence on citizenship and living together (kc 7) as well, which is elaborated—albeit without references to cultural heritage—in a clear manner.

Figure 1.

Sustainability and heritage education in the curriculum framework.

Besides the cross-curricular transversality, another characteristic of heritage education in Flanders’ secondary education can be found in its procedural and attitudinal focus. The relevant learning outcomes are mainly suitable for valuing and respecting of and reflecting on heritage manifestations. The latter is also the case for sustainable development, but, specifically for heritage education, this approach can be beneficial. The Flemish government did not determine what heritage should be addressed nor stipulate any conditions on its implementation. The intention of the development committees was to construct an open curriculum framework on which the educational providers, schools, and teachers could build further. In this way, they can connect content to the curriculum framework that is adapted to the regional or local cultural diversity and contextual environment, thus improving involvement and relevance for students. Teachers can find support in textbooks from educational publishers. However, these mostly rely on generic didactic examples instead of responding to cultural or local diversity. A sense of belonging and knowledge of the local area can contribute to acquiring social and civic competences and forming critical citizenship [46,47]. Furthermore, local heritage is also seen as a fundamental pillar in developing historical thinking.

On the other hand, the openness of the curriculum has a downside as well, specifically in Flanders’ formal education system. On a lower level, these learning outcomes need to be transformed into curricula by the educational providers, according to their own pedagogical emphasis and cultural background. Additionally, they possess the right to expand the outcomes of the Flemish government, which are constituted as minimum goals. The question at hand is how the educational providers will make this transfer? Do the broadly defined learning outcomes suffice to create valid and operational curricula? Which relevant stakeholders will be involved?

Furthermore, schools in Flanders are autonomous in interpreting the given framework from the educational providers and setting up a valuable learning environment. Since the curricula seldom explicitly refer to heritage, its integration by schools and teachers can be a difficult task. When the transversal potential of heritage education remains implicit for lower levels, not every teacher will see and apply the cross-curricular opportunities.

Leaving the focus on conceptual connections between heritage education and sustainable development behind, a few recommendations can be made to operationalise them in an interlinked manner.

To start, they share two interesting aspects. As conceptually made clear, on the one hand, the key competence on citizenship and living together (kc 7) provides overlap. On the other hand, they rely strongly on the local environment. When combining both, the local context, containing heritage manifestations, specific sustainability issues, and social and civic challenges, forms a common ground and starting point. In this way, it enables young people to link local and familiar problems gradually to more global issues, thus working on the concept of global citizenship education (GCED) in SDG 4, target 4.7.

Second, achieving a sustainable and inclusive environment aimed at in SDG 11, starts locally. Therefore, including regional or local content regarding cultural heritage or sustainability is ideally not worked out at the national level (in the case of Flanders, by the Flemish government or by the educational providers). A more bottom-up and participative process should take place. On the one hand, this provides the teachers, as final implementers of curricular ideas, a way to identify themselves with these ideas [48]. Besides ownership for schools and teachers, it can be, on the other hand, beneficial for students as well. Including local content brings a sense of relevance and involvement in the curriculum [14].

Third, schools, local cultural communities, and all related actors and agents should grow closer together. In this light, the report ‘Culture in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda’ considers culture as an invaluable driver and enabler to help communities thrive and be sustainable. The call for partnership is embedded in SDG 17, which emphasises the need to engage in partnerships to achieve all other goals. From this perspective, Benavot stresses the need for policy makers to develop cross-sectoral strategies [49]. The SDGs are based on interconnectivity. According to Kamau, Chasek, and O’Connor, partnership is not merely a condition to achieve the goals, but an integral part of what sustainability encompasses [50].

Nonetheless, the masterplan at the start of the curriculum reform in Flanders in 2013 stated that: “the exchange of knowledge between schools and the local communities and external organisations was limited until then [25] (p. 14). Consequently, this forms a significant challenge and can be a suggestion for future research in light of the SDGs. Recent research of Castro-Calviño, Rodríguez-Medina, and López-Facal shows that designing and operationalising educational heritage content, with the aim of creating links between the school and the local community, is considered to be relevant [14].

Finally, when closing the distance between the conceptual frameworks and classroom practice, it is the task of the centralised level to provide sufficient didactic suggestions, inspiration guides, and clear cross-curricular connections. However, the professional freedom and creativity of teachers should not be limited. The difficulty lies in finding a balance between openness and concreteness. In addition, to find usable and deployable teaching methods, more synergies between academic research and teachers need to be set up, for example, through (participative) action research. In this way, the gap between the conceptualization of heritage education in curricula and classroom practice, as issued by Van Boxtel, Grever, and Klein in 2016 [12], could be addressed.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Returning to the initial objective, the results show that heritage education is implicitly present in the newly adopted curriculum of the first grade of secondary education in Flanders. Cross-curricular opportunities are built-in and can be linked to (a) cultural awareness and expression; (b) historical consciousness; (c) citizenship; and (d) intercultural communication. Sustainable development, and more specific ESD, anchored itself firmly and explicitly into the framework as a transversal key competence as well. Nevertheless, clear connections to heritage education are not set up in the learning outcomes for the first grade of secondary education. Here, it can be noticed that relevant stakeholders of the heritage sector were not involved during the development process.

Regarding the limitations of the approach in this study, it can be stated that the absence of connections in the curriculum framework and the omission of explicit references remain primarily conceptual. However, the interviews with the members of the development committee revealed that an open curriculum framework was deliberately pursued. Conceptually, the framework offers sufficient support. Nevertheless, connections have to be elaborated at lower levels, preferably in relation to the local contextual environment of students. Thus, the challenge at hand is to transfer it into classroom practice. Here, a more bottom-up and participative process should take place. Including local content and partnership with communities and stakeholders brings a sense of relevance and involvement in the curriculum. The social and civic aspects of heritage education form a common ground and starting point to link local heritage manifestations and familiar sustainability challenges to more global issues. On a more practical level, it has to be noted that the ESD portal of the Flemish administration mentions possible connections to cultural and heritage education, and that recently innovative and collaborative pilot projects are worked out to connect local heritage with primary and secondary schools.

Besides the strong conceptual focus of this study, a second limitation can be found in its scope. Only the learning outcomes for the first grade, which form a coherent set, could be examined. The ones meant for the second and third grade were drafted by the government but had yet to be approved by the Flemish parliament.

Future research could further examine how heritage education and sustainable development are conceptually interlinked. For example, the way schools, local communities, and heritage organisations exchange knowledge and (could) cooperate in light of the SDGs remains mostly unknown. However, in the end, teachers benefit most from research that closes the distance between the curriculum and classroom practice. The multifaceted concept of heritage education could be further deconstructed, so that separate studies could explore each interlinked aspect in a more comprehensive manner. In this way, concrete didactic suggestions, quality criteria, evaluation methods, and inspiration guides could be developed and dispersed for classroom practice in Flanders.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons of the interviewees. The interviews were carried out in Dutch.

Acknowledgments

This paper is the result of two research projects: First, the master’s thesis Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage through Formal Education in Flanders: The Implementation of the UNESCO 2003 Convention. This research came about with the support of the Workshop intangible heritage in Flanders. Prof Dr Marc Jacobs, coordinator of the UNESCO chair on critical heritage studies and safeguarding the intangible cultural heritage at Free University of Brussels (VUB) and professor critical heritage studies at Antwerp University (UA), acted as promoter. Jorijn Neyrinck, director of the Workshop intangible heritage (WIE) in Flanders, took on the role of co-promoter. Second, the results are part of a current doctoral dissertation Inherited from the past, shaped by the present? Investigating the didactic potential of heritage in history education in Flanders. It is carried out at Ghent University and supervised by Bruno De Wever (promoter).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- Lowenthal, D. The Past Is a Foreign Country–Revisited; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Pérez, R.; Cuenca López, J.M.; Ferreras Listán, D.M. Heritage Education: Exploring the Conceptions of Teachers and Administrators from the Perspective of Experimental and Social Science Teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocal, T. Necessity of Cultural Historical Heritage Education in Social Studies Teaching. Creat. Educ. 2016, 7, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gómez-Carrasco, C.J.; Miralles-Martinez, P.; Fontal, O.; Ibañez-Etxeberria, A. Cultural Heritage and Methodological Approaches: An Analysis through Initial Training of History Teachers (Spain–England). Sustainability 2020, 12, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felices-De la Fuente, M.d.M.; Chaparro-Sainz, Á.; Rodríguez-Pérez, R.A. Perceptions on the use of heritage to teach history in Secondary Education teachers in training. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Valencia, G.; Massip Sabater, M.; Castellví Mata, J. Heritage Education and Global Citizenship. In Handbook of Research on Citizenship and Heritage Education; Delgado-Algarra, E.J., Cuenca-López, J.M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estepa Giménez, J.; Ávila Ruiz, R.M.; Ferreras Listán, M. Primary and Secondary Teachers’ Conceptions about Heritage and Heritage Education: A Comparative Analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 2095–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, P.; Morton, T. The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts; Nelson Education: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kokko, S.; Kyritsi, A. Cultural Heritage Education for Intercultural Communication. Int. J. Herit. Digital Era 2012, 1, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Recommendation No. R(98) 5, of the Committee of Ministers to Member States Concerning Heritage Education, Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 17 March 1998 at the 623rd meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies. Available online: http://rm.coe.int/16804f1ca1 (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Emiliani, M.D. Cultural Heritage Education in Italy and other European Countries. In Heritage Education for Europe: Outcome and Perspective; Branchesi, L., Ed.; Armando Editore: Rome, Italy, 2007; pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boxtel, C.; Grever, M.; Klein, S. Introduction: The Appeal of Heritage in Education. In Sensitive Pasts: Questioning Heritage in Education; van Boxtel, C., Grever, M., Klein, S., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-López, J.M.; Estepa-Giménez, J.; Martín-Cáceres, M.J. Heritage, education, identity and citizenship. Teachers and textbooks in compulsory education. Rev. Educ. 2017, 375, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Calviño, L.; Rodríguez-Medina, J.; López-Facal, R. Heritage Education under Evaluation: The Usefulness, Efficiency and Effectiveness of Heritage Education Programmes. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, R. Effective Approaches to Heritage Education: Raising Awareness through Fine Art Practice. Int. J. Educ. Through Art 2017, 13, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.; Kanie, N. The Transformative Potential of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Volume 16, pp. 393–396. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, N.K.; Mishra, I. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 and Environmental Sustainability: Race against Time. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 2, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standaert, R.; Valcke, M. Onderwijsbeleid in Vlaanderen—Second Revised Edition; Acco: Lake Zurich, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, E.; Craeybeckx, J.; Meynen, A. Political History of Belgium: From 1830 Onwards; Asp—Vubpress—Upa: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flemish Parliament. 1469 (2017–2018)—No. 3, Text of the Decree Adopted by the Plenary Session: Van Het Ontwerp van Decreet tot Wijziging van de Codex Secundair Onderwijs van 17 December 2010, Wat Betreft de Modernisering van de Structuur en de Organisatie van het Secundair Onderwijs. 2018. Available online: http://docs.vlaamsparlement.be/pfile?id=1385966 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Van Der Auwera, S.; Schramme, A.; Jeurissen, R. Erfgoededucatie in het Vlaamse Onderwijs: Erfgoed en Onderwijs in Dialoog; CANON Cultuurcel: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bamford, A. Kwaliteit en Consistentie: Arts and Cultural Education in Flanders; Flemish Ministry of Education and Training, CANON Cultuurcel: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Auwera, S. Erfgoededucatie in het Vlaamse Onderwijs. Cult. Educ. 2007, 19, 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Grever, M.; Van Boxtel, C. Verlangen naar Tastbaar Verleden; Uitgeverij Verloren: Torenlaan, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flemish Parliament. Nota van de Vlaamse Regering: Masterplan Hervorming Secundair Onderwijs, Submitted on June 5th 2013; p. 14. Available online: http://docs.vlaamsparlement.be/pfile?id=1039084 (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Levuur, Indiville, Tree Company. Onsonderwijs.be–Van LeRensbelang. Participatief publiek debat over de eindtermen. Brussels, Belgium, 2016. Available online: https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Van-Lerensbelang-eindrapport.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Flemish Parliament. 671 (2015–2016)—No. 1, Report of the Hearing: In het kader van het maatschappelijk debat over de eindtermen, over de werkwijze van het Nederlandse Platform Onderwijs2032 en het Eindadvies over een Toekomstgericht Curriculum voor het Primair en Voortgezet Onderwijs. 2016. Available online: http://docs.vlaamsparlement.be/pfile?id=1166247 (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- European Union, Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of December 18th, 2006, on the key competences for lifelong learning. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, L394. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/nl/oj/2006/l_394/l_39420061230nl00100018.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Vlaamse Overheid. Onderwijsdoelen: Secundair Onderwijs, 1e graad, A-stroom/B-stroom, uitgangspunten. Available online: http://onderwijsdoelen.be/uitgangspunten/4647 (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- FARO. Mission and Service. Available online: http://faro.be/en/faro-flemish-institution-cultural-heritage (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- CANON Cultuurcel. Mission and Vision. Available online: http://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/canon/missie-visie (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods, 3rd ed; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Flemish Administration. Education Goals. Available online: http://www.onderwijsdoelen.be (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Publications Office of the European Union. Cultural Awareness and Expression Handbook; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeersch, L.; Vandenbroucke, A.; De Backer, F.; Lombaerts, K.; Elias, W.; Groenez, S. Culturele Basisvaardigheden: Een Ontwikkelingslijn op Basis van de Cultuurtheorie ‘Cultuur in de Spiegel’; CANON Cultuurcel: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Flemish Parliament. 1752 (2018–2019)—No. 1, Design of the Decree: Betreffende de Onderwijsdoelen voor de Eerste Graad van het Secundair Onderwijs. 2018. Available online: http://docs.vlaamsparlement.be/pfile?id=1430279 (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Puttevils, T.; Vanmontfort, B.; Van Nieuwenhuyse, K.; Van Peer, P. Ons Verste Verleden: Historisch Denken over de Prehistorische Mens in de Oude Wereld; Leuven University Press: Leuven, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz-Serrano, J.; Gómez-Carrasco, C.J.; López-Facal, R. National Narratives and Historical Competencies in Spanish Initial Teacher Training. Tempo E Argum. 2017, 9, 174–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, R. Understanding Historical Evidence. Teaching and learning challenges. In Debates in History Teaching; Davies, I., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Petti, L.; Trillo, C.; Makore Busisiwe, N. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development Targets: A Possible Harmonisation? Insights from the European Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Culture 2030 Goal Campaign. Culture in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda. 2019. Available online: http://www.ifla.org/files/assets/hq/topics/libraries-development/documents/culture2030goal.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals, SDG 4. Available online: http://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Flemish Parliament. Written Question No. 45, on October 17th, 2016; p. 17. Available online: http://docs.vlaamsparlement.be/pfile?id=1220405 (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Flemish Administration. Leren voor een Leefbare Toekomst: Vlaams Implementatieplan voor Educatie voor Duurzame Ontwikkeling. 2009. Available online: http://www2.omgeving.vlaanderen.be/display/EDOP/Vlaamse+overheid#Vlaamseoverheid-VlaamsimplementatieplanEDO(2009-2015) (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Fuentes-Moreno, C.; Sabariego-Puig, M.; Ambrós-Pallarés, A. Developing Social and Civic Competence in Secondary Education through the Implementation and Evaluation of Teaching Units and Education Environments. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabajo-Rite, M.; Cuenca-López, J.M. Student Concepts after a Didactic Experiment in Heritage Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikser, R.; Kärner, A.; Krull, E. Enhancing Teachers’ Curriculum Ownership via Teacher Engagement in State-based Curriculum-making: The Estonian case. J. Curric. Stud. 2016, 48, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavot, A. The SDG Framework and Reflections on Accountability in Education, Presentation given at the Flemish Education Council Conference, 26 February 2019. Available online: http://www.vlor.be/activiteiten/verslagen/studiedag-internationale-beleidskaders-voor-onderwijs (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Kamau, M.; Chasek, P.; O’Connor, D. Transforming Multilateral Diplomacy: The Inside Story of the SDG’s; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).