Abstract

Persea americana, commonly known as avocado, has recently gained substantial popularity and is often marketed as a “superfood” because of its unique nutritional composition, antioxidant content, and biochemical profile. However, the term “superfood” can be vague and misleading, as it is often associated with unrealistic health claims. This review draws a comprehensive summary and assessment of research performed in the last few decades to understand the nutritional and therapeutic properties of avocado and its bioactive compounds. In particular, studies reporting the major metabolites of avocado, their antioxidant as well as bioavailability and pharmacokinetic properties, are summarized and assessed. Furthermore, the potential of avocado in novel drug discovery for the prevention and treatment of cancer, microbial, inflammatory, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases is highlighted. This review also proposes several interesting future directions for avocado research.

1. Introduction

Persea americana (commonly known as avocado, avocado pear, or alligator pear) is native to Mexico and Central America, and a member of the flowering plant family Lauraceae [1,2]. Botanically, avocado fruit is a berry with a single large seed [3]. Mexico is the leading producer of avocados worldwide [2]. The term “superfood” refers to foods that are beneficial to human health due to their high levels of nutrients and/or bioactive phytochemicals such as antioxidants [4]. In particular, avocado has recently gained dramatic popularity [5] and is often referred to as a “superfood” because of its unique nutritional and phytochemical composition compared to other fruits. This has led to an exponential increase in avocado consumption from 2.23 pounds per capita in 2000 to 7.1 pounds per capita in 2016 in the United States [6]. However, the term “superfood” has been used ambiguously in popular media, and often marketed with misleading health claims of preventing and curing ailments. Considering their immense popularity and diverse biochemical content, avocados have also been extensively used in the food, nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. In addition, their health-benefiting properties have been investigated in a number of preclinical and clinical studies in the last few decades. The present review article is focused on the comprehensive summary and assessment of research performed to understand the role of avocado and its bioactive compounds in the prevention and treatment of various ailments, including cancer, microbial, inflammatory, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. The studies emphasizing the nutritional composition of avocado, its major metabolites, and their pharmacokinetic properties are also reviewed and summarized. Furthermore, this review highlights several interesting aspects for future research on avocado.

1.1. The Vast Array of Secondary Metabolites of Avocado and Their Biological Significance

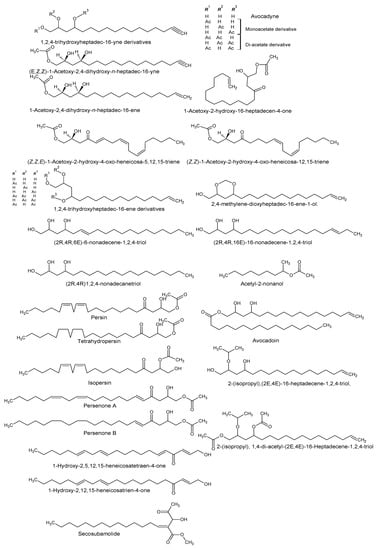

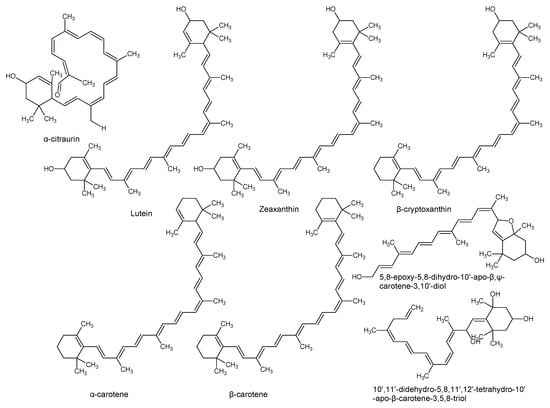

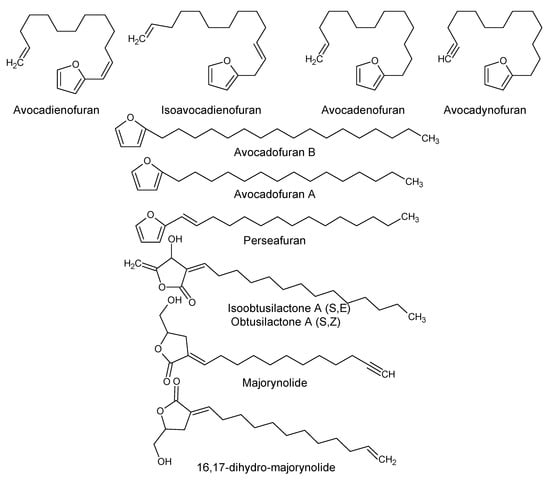

Using “Avocado” and “Persea” as search descriptors with a focus for pharmacologically active metabolites, various avocado metabolites were retrieved from Combined Chemical Dictionary v23.1 (CCD) [7] and The Human Metabolite Database (HMDB) [8]. In addition to the P. americana, the search strategy also covered other Persea species such as P. mexicana, P. indica, P. gratissima, P. obovatifolia, and P. borbonia (Table 1). As per the literature, most bioactive compounds were isolated predominantly from P. americana. Other synonyms of P. americana are P. gratissima, Laurus persea, P. drymifolia, and P. nubigena [9]. The metabolite arsenal can be classified chemically into eight main classes, including fatty alcohols, furan derivatives, carotenoids, carbohydrate, diterpenoids, lignan derivatives, and miscellaneous compounds, as shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, and Table 1. In brief, fatty alcohols isolated from avocado showed different degrees of unsaturation and alkyl chain length with several levels of hydroxylation and subsequent acetylation (Figure 1). These fatty alcohols have been reported to exhibit antiviral, cytotoxic, antifungal, trypanocidal, and antioxidant activity [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Phenolic compounds (Figure 2, and Table 1) of different chemical classes from simple organic acids such as gallic acid to larger flavonoids, anthocyanidins, and tocopherols were isolated from Persea species with significant antioxidant, neuroprotective and cardioprotective activities [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The antioxidant properties of avocado were also ascribed to their carotenoid content in many studies [24,28,29,30] (Figure 3). Moreover, sugar alcohol and ketoses with variable carbon chain length were isolated from avocado (Figure 4). Notable insecticidal, cytotoxic, and antifungal activities were also reported for the furan and furanone derivatives isolated from Persea species [18,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] (Figure 5), where the saturation of the furan ring was detrimental for the insecticidal activity [38]. The insecticidal activity of the furan derivatives was augmented by the diterpenoids compounds [39,40,41,42,43], especially in P. indica (Figure 6). Overall, avocado contains a vast array of secondary metabolites of different chemical classes which may attribute to its diverse biological activities.

Table 1.

Metabolites isolated from Persea species.

Figure 1.

Fatty alcohols isolated from avocado.

Figure 2.

Phenolic compounds isolated from avocado.

Figure 3.

Carotenoids isolated from avocado.

Figure 4.

Sugars and sugar alcohol isolated from avocado.

Figure 5.

Furan and furanone derivatives isolated from avocado.

Figure 6.

Diterpenoids isolated from avocado.

Figure 7.

Norlignans, neolignans, and lignans isolated from avocado.

Figure 8.

Miscellaneous compounds isolated from avocado.

1.2. Nutritional Composition of P. americana

Avocados have been recognized for their high nutritional value and therapeutic importance for centuries. The nutritional composition of avocado is shown in Table 2 according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) [61]. A whole avocado is reported to contain 140 to 228 kcal (~585–1000 kJ) of energy depending on the size and variety [62]. The variety, grade of ripening, climate, the composition of the soil, and fertilizers are the major factors that largely influence the nutritional profiles of avocados [63].

Table 2.

Pulp composition of Persea americana (avocado) [61].

Fiber constitutes most of its carbohydrate content (~9 g of fiber and 12 g of carbohydrate per avocado) (Table 2) and can reach up to 13.5 g in larger avocados. Higher quantities of insoluble and soluble fibers (70% and 30%, respectively) are found in the pulp [3]. A single serving can provide about 2 g protein and 2 g of fiber with a glycemic index of 1 ± 1 [64]. A high-fiber diet is often linked with a healthy digestive system. Moreover, it may help lower blood cholesterol levels and prevent constipation by improving bowel movement. In particular, avocados have been shown to improve the microflora of the intestines by working as a prebiotic [65]. In addition to fat, avocados are rich in protein (highest among fruits), sugars including sucrose and 7-carbon carbohydrates (d-mannoheptulose), antioxidants, pigments, tannins, and phytoestrogens [66].

Fat contributes to most of the calories in an avocado. A 1000-kJ portion of avocado contains about 25 g of fat, most of which are healthier monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) [64]. The lipid content in avocados is higher than in other fruits. Most lipids found in avocados are polar lipids (glycolipids and phospholipids), which play a fundamental role in various cellular processes such as the functioning of the cell membranes as second messengers [67]. These lipids are also used to make emulsions of water and lipids, and have a wide variety of applications in food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics industries [68]. Compared to other vegetable oils, avocado oils are high in MUFA (oleic and palmitoleic acids) and low in polyunsaturated fatty acids (linoleic acid and linolenic acid) [3]. Oleic acid is the principal fatty acid in avocado, comprising 45% of its total fatty acids [69], and during the ripening process, palmitic acid content decreases and oleic acid content increases [70]. In terms of its total fat content and fatty acid composition, avocado oil is considered to be similar to olive oil [71]. Other fatty acids present include palmitic and palmitoleic acids with smaller [64] amounts of myristic, stearic, cinolenic, and arachidonic acids [62]. However, the compositions of these fatty acids largely depend on the cultivars, stage of maturity, and part of the fruit and geographic location of plant growth [62]. Avocado spread instead of other fatty alternatives such as butter, cream cheese, and mayonnaise on sandwiches can help significantly reduce the intake of calories, saturated fat, sodium, and cholesterol.

Avocados are notable for their potassium content (>500 mg/100 g of fresh weight), and it provides 60% more than an equal serving of banana [72]. Potassium intake helps to maintain cardiovascular health and muscle function by regulating the blood pressure through the modulation of liquid retention in the body [65]. In addition, potassium regulates the electrolyte balance in the body, which is important for the conduction of electrical signals in the heart (i.e., a steady, healthy heart rate) [65]. The high potassium and low sodium contents in the diet are shown to protect against cardiovascular diseases [3]. Moreover, avocados contain a number of other minerals, including phosphorus, magnesium, calcium, sodium, iron, and zinc (<1 mg/g of fresh weight) [73].

Vitamins such as β-carotene, tocopherol, retinol, ascorbic acid, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pyridoxine, and folic acid are also abundantly found in avocado, which are of great importance for overall health and well-being (Table 2) [62,74]. Carotenoids, including lutein, zeaxanthin, and α- and β-carotene found in the pulp of the avocado are potent free radical scavengers [65,74]. The lutein content of avocado is higher than any other fruit, which comprises about 70% of its total carotenoid content [65]. The color of avocado pulp is predominantly attributed to the higher content of xanthophylls (lutein and zeaxanthin). Seasonal variations in the phytochemical profile of avocado especially carotenoids, tocopherol, and fatty acid content have also been reported [65]. Due to their fat-soluble nature, these bioactive compounds have been shown to promote vascular health [65]. Xanthophylls suppress the damage of blood vessels by decreasing the amount of oxidized low-density lipoproteins (LDL) [75]. Additionally, lutein and zeaxanthin have been reported to slow down the progression of age-related macular degeneration, cataracts, and cartilage deterioration [74,76]. Carotenoids in general were demonstrated to protect the skin from ultraviolet radiation-associated oxidation and inflammation [62]. Furthermore, a 68 g serving of Hass avocado contains about 57 mg of phytosterols, which is significantly higher compared to other fruits (about 3 mg per serving) [65]. Avocado phytosterols have been reported to reduce the risks of coronary heart disease [65]. The American Heart Association recommends the consumption of 2–3 g of sterols and stanols per day to promote heart health [65,77]. They are the plant analogues of cholesterol and can be classified into three major groups consisting of β-sitosterol, campesterol, and stigmasterol [78]. The most abundant phytosterol present in avocado is β-sitosterol (76.4 mg/100g), followed by campesterol (5.1 mg/100g) and stigmasterol (<3 mg/100g) [79]. In addition to its cholesterol-lowering activity, β-sitosterol has been demonstrated to inhibit the production of carcinogenic compounds, alleviate symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia, and strengthen the immune system [79]. In summary, these compounds have been hypothesized to work in conjunction in the prevention of oxidative stress and age-related degenerative diseases [80].

1.3. Antioxidant Properties of P. americana

Considering the health risks associated with synthetic antioxidants, the extraction, isolation, and identification of antioxidants from natural sources have become primary research focuses of the food, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical industries in the recent years [81,82,83]. Annually, over three million tons of avocados are produced worldwide, with only the pulp being used, while the seeds and peel are discarded [2]. Waste utilization by exploiting the phytochemical content of avocado by-products such as seeds and peel will add more value to the avocado industry and may lead to novel product development [84]. Table 3 represents the studies currently available in the literature emphasizing the role of P. Americana plant as the source of potent antioxidants. Different parts of the plant, including the leaf, fruit pulp, peel, and seed have been widely studied for their antioxidant properties using conventional spectroscopic assays such as 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid diammonium salt (ABTS), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC), cupric-reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC), and ferric-reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as well as more sensitive analytical techniques including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and gas chromatography-flame ionization detector (GC-FID). Hass is the most explored avocado variety in terms of its antioxidant properties, which can perhaps be attributed to the popularity and easier availability of this variety. It is evident from the studies performed so far that phenolic compounds (including phenolic and hydroxycinnamic acids, flavonoids, and condensed tannins), carotenoids, α, β, γ, and δ-tocopherols, acetogenins, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids are the key antioxidants found in avocado. Moreover, most of these studies have reported significant positive correlations between the phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of avocado extracts [84,85,86,87,88]. Phenolic compounds found in avocado were shown to reduce oxidation, inflammation, and platelet aggregation [65]. Several studies have reported that different parts of the avocado plants contain potent phenolic antioxidants such as chlorogenic-, quinic-, succinic-, pantothenic-, abscisic-, ferulic-, gallic-, sinapinic-, p-coumaric-, gentisic-, protocatechuic-, 4-hydroxybenzoic-, and benzoic- acids, quercetin, quercetin-3-glucoside, quercetin-3-rhamnoside, vanillin, p-coumaroyl-D-glucose, catechins, (−)-epicatechin, and procyanidins (Table 3) [2,28,84,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97]. Among the different parts of avocado investigated in several studies, leaf, peel, and seed extracts have shown consistently greater antioxidant capacity compared to that of the pulp [84,91,94,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106]. Due to the presence of higher catechin, epicatechin, leucoanthocyanidin, triterpenes, furoic acid, and proanthocyanidin contents, avocado seed extracts have been reported to display greater antioxidant capacity [62,74]. Additionally, the ripening process was also shown to influence the phenolic contents of different parts of the avocado plant [96,107,108]. For example, a study by López-Cobo et al. [96] found a higher content of phenolics in the pulp and seed extracts of overripe avocados compared to their optimally ripe counterparts. It was hypothesized that the increase in the total phenolic content in the overripe fruit was mediated by higher phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity associated with the ripening process [96]. They also observed an increased concentration of procyanidins in the overripe parts of the avocado, which was probably a result of the hydrolysis of complex tannins after ripening. Avocado peel, seed, and leaf, as the major by-products of the avocado industry, have been demonstrated as rich sources of polyphenolics and antioxidants. More studies developing robust, green, and economical extraction techniques are fundamental to obtain greater yields of potent antioxidants. In vivo and clinical studies to understand the bioavailability of these antioxidants and their potential toxicity are also crucial.

Table 3.

Antioxidant properties of Persea Americana (avocado).

1.4. Anticancer Properties of P. americana

Cancer causes more deaths than acquired immune deficiency syndrome, tuberculosis, malaria, and diabetes combined [131]. The greatest challenges of anticancer regimens are attributed to the complex mutational landscapes of cancer, late diagnoses, expensive therapeutic options, and the development of resistance to chemo and radiation therapies [132,133]. Chemotherapy-associated side effects and toxicity also make cancer one of the most challenging diseases to treat [133]. Natural products or their derivatives comprised over 45% of the FDA-approved anticancer drugs between 1981–2010 [134]. In the United States, several plant-derived products, either alone or in conjunction with mainstream chemo and radiation therapies are used by approximately 50–60% of cancer patients [132,135]. Therefore, the search for safer alternatives to be used either as mono or adjunct therapy with the standard drugs is becoming a priority in anticancer research [136]. The in vitro cytotoxic properties of avocado against different types of cancer cell lines including breast, colon, liver, lungs, larynx, leukemia, oesophageal, oral, ovary, and prostate have been extensively reported in the literature (Table 4). These properties have also been investigated in preclinical animal models. Interestingly, these in vitro and in vivo studies have not only explored the pulp, the most edible part of the fruit, but also the leaves, peel, and seeds of avocado. Table 4 depicts the major preclinical and clinical studies currently found in the literature emphasizing the potential anticancer activity of avocados. The chemical profiles of different parts of avocado vary among the varieties [84,137]. Therefore, rationally, depending on the chemical profiles, the bioactivities also vary accordingly. Many studies assessing the anti-proliferative activity of avocado did not report the varieties used. However, based on the limited studies that reported the varieties tested, Hass is perhaps the most explored cultivar for its anticancer properties. Molecular mechanistic studies in various cancer cell lines have reported the regulation of different signal transduction pathways, especially the induction of caspase-mediated apoptosis and the involvement of cell cycle arrest by different avocado extracts, their fractions, and isolated compounds (Figure 9, Table 4) [24,26,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145]. For instance, Dabas et al. [140] recently found out that the methanol extract of Hass avocado seeds induced caspase 3-mediated apoptosis, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage, and cell cycle arrest at G0/G1, as well as reduced the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and downregulated the cyclin D1 and E2 in lymph node carcinoma of the prostate (LNCaP) cells. Parallel observations were made earlier by Lee et al. [144] in MDA-MB-231 (MD Anderson metastasis breast cancer) cells using methanol extracts of avocado seeds and peel. They observed the activation of caspase-3 and its target protein- PARP, in MDA-MB-231 cells. Bonilla-Porras et al. [138] found out that ethanol extracts of avocado endocarp, seeds, whole seeds, and leaves activated transcription factor p53, caspase-3, apoptosis-inducing factor, and oxidative stress-dependent apoptosis via mitochondrial membrane depolarization in Jurkat lymphoblastic leukaemia cells. The acetone extract of avocado pulp rich in lutein, zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, α-carotene, β-carotene, α-tocopherol, and γ-tocopherol was shown to arrest the PC-3 prostate cancer cells at the G2/M phase and increase the expression of p27 protein [24]. The cytotoxic properties of different classes of compounds contribute to the cumulative anticancer activity of avocado. For example, the anticancer effects of the fatty alcohols, carotenoids, and phenolics were further augmented by the potential anticancer effect of norlignans/neolignans (Figure 7) from P. obovatifolia [48,49,50,51,52,53].

Table 4.

Preclinical and clinical studies highlighting the anticancer properties of Persea americana (avocado).

Figure 9.

Effect of Persea americana (avocado) and its components on different cellular signal transduction pathways. The molecular targets highlighted in yellow play key roles in the proliferation, survival, migration/invasion, and apoptosis of cancer cells. Purple stars indicate the molecular targets involved in inflammatory response.

Scopoletin, a plant coumarin and phytoalexin found in avocado, reduced the carcinogens-induced toxicity and the size of skin papilloma in vivo [26]. Further mechanistic study revealed the modulation of various key cell cycle, apoptotic and tumor invasion markers by scopoletin. Notably, the downregulation of AhR (aryl hydrocarbon receptor), CYP1A1 (cytochrome P450 1A1), PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen), stat-3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3), survivin, MMP-2 (matrix metalloproteinase-2), cyclin D1 and c-myc (avian myelocytomatosis virus oncogene cellular homolog); and the upregulation of p53, caspase-3 and TIMP-2 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2) by scopoletin were demonstrated [26]. Of note, the expression of p53 and its target genes (~500) regulate a wide range of cellular processes, including apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and DNA repair [146]. Additionally, the upregulation of TIMP-2 inhibits MMP-2 expression, which consecutively leads to the reduction of cellular migration and invasion (metastasis) [147,148]. Therefore, MMP-2 upregulation has been correlated with poor prognosis and relapse in cancer patients [147]. Another study by Roberts et al. [149] also indicated synergistic interaction between the breast cancer standard drug—tamoxifen—and persin isolated from avocado leaves against MCF-7 (Michigan cancer foundation-7), T-47D, and SK-Br3 breast cancer cells in vitro. The authors reported a significant reduction of tamoxifen IC50 values when it was combined with avocado persin. The synergistic interaction was Bim-dependent and mediated by the modulation of ceramide metabolism [149]. Bim is a member of the Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) family of proteins that play a key role in the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway of apoptosis [150,151]. In particular, Bim is linked with microtubule-stabilizing properties, which mediate the formation of microtubule bundles with subsequent mitotic arrest and apoptosis [139,152].

Chemical synthesis of the most potent anticancer compounds found in avocado has also been carried out in a number of studies [143,145,153,154]. Similar to avocado crude extracts, chemically synthesized avocado peptide PaDef defensin was recently found to induce apoptosis via caspase 7, 8, and 9 expressions in K562 chronic myeloid leukaemia and MCF-7 breast cancer cells in two studies by the same research group [143,153]. Moreover, PaDef defensin was previously demonstrated to have antimicrobial properties [155,156]. The induction of apoptosis and abrogation of the cell cycle were also observed earlier in the human breast, lung, ovarian, and colorectal cancer cells when treated with chemically synthesized avocado β-hydroxy-α,β-unsaturated ketones by Leon et al. [145]. Although many preclinical studies were performed to elucidate the cytotoxicity of extracts derived from different parts of the avocado plant and their components, very few of them have investigated their molecular mechanisms of action. Interestingly, contradicting information regarding avocado extract-induced genotoxicity is also available. For instance, Kulkarn et al. [157] found out that avocado fruit and leaf extracts can induce chromosomal aberrations in human peripheral lymphocytes, with leaf extract being more genotoxic. The same research group later reported that avocado fruit extract can reduce cyclophosphamide-mediated chromosomal aberrations in human lymphocytes [158], which was perhaps due to the antagonistic effects of the extract on cyclophosphamide.

Traditionally, an avocado leaf decoction is used for the treatment of tumors and tumor-related diseases in Nigeria [159]. Despite their health benefits highlighted in numerous reports, clinical studies examining the direct correlation between avocado consumption and the prevention and treatment of cancer are scarce. Only one case-control study involving 243 men with prostate cancer and 273 controls in Jamaica demonstrated that MUFA from avocado may reduce the risk of prostate cancer [160]. However, it should be noted that bioactive compounds that are also commonly found in avocados such as α-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin were found to have inverse associations with cancers of the mouth, larynx, pharynx, and breast in few clinical trials, as highlighted in Table 5 [161,162,163]. According to the USDA, avocados contain a significantly higher amount of glutathione per average serving compared to other fruits [61]. Glutathione is a potent tripeptide antioxidant that plays a major role in detoxification pathways and the reduction of oxidative stress and risk of cancer [62,65]. Notably, it has been linked with the reduction of chemotherapy-associated toxicity and risks of oral cancer in a few clinical studies [57,58,59,164]. Nonetheless, the molecular mechanism of how glutathione reduces the side effects of chemotherapeutic regimens remains largely speculative. In order to precisely understand the anticancer mechanisms of action of avocado extracts and their bioactive compounds, more in vitro and in vivo studies are warranted. As very few studies have identified the solitary bioactive compounds responsible for the growth inhibition of different cancer cells, more research should be undertaken to gain a comprehensive understanding of the chemical profiles of the active extracts. Notably, bioassay-guided fractionation and the subsequent isolation and characterization of biologically active compounds from different parts of the avocado plant may lead to the identification of many novel anticancer compounds. Randomized controlled trials should be designed to evaluate the efficacy of bioactive compounds derived from avocado in the prevention and treatment of different cancer types. Furthermore, the chemoprotective properties of avocado and the possibility of using its bioactive compounds as an adjunct therapy for cancer should also be explored.

Table 5.

Clinical studies demonstrating the anticancer activity of bioactive compounds that are also commonly found in Persea americana (avocado).

1.5. Antimicrobial Properties of P. americana

Currently, there is a growing interest in finding alternatives to the synthetic antimicrobial agents that are commonly used in the food and pharmaceutical industries. This is due to the concerns of the consumers regarding the safety of products containing synthetic chemicals and their associated health risks [174]. Seeds (endocarp) and peels (exocarp) being the by-products of the avocado industry are generally disposed of as wastes [175] and have been investigated for their antimicrobial properties. Most of the studies conducted thus far have noted the antimicrobial activity of the extracts derived from different avocado varieties [104,176,177,178], while only a few have reported insignificant antimicrobial activity [101,179]. The antimicrobial activity of avocado extracts might be influenced by (i) the variety of the avocado, (ii) the parts used for investigation (i.e., exocarp, endocarp, or mesocarp), (iii) the solvent type used for extraction, and iv) the bacterial species examined [104,176]. Raymond and Dykes [176] investigated the antimicrobial activity of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of seeds and peels of three different avocado varieties (Table 6). The authors reported that ethanolic extracts had antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (except for Escherichia coli) ranging from 104.2 to 416.7 μg/mL, while aqueous extracts exhibited activity against Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Rodriguez-Carpena et al. [104] investigated the antibacterial activity of the extracts derived from different avocado parts (peel, seed, and pulp) of a number of varieties against Bacillus cereus, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, E. coli, Pseudomonas spp., and Yarrowia lipolytica. The highest inhibitory activity against the Gram-positive bacteria- B. cereus and L. monocytogenes was observed, while E. coli was the most sensitive among the tested Gram-negative bacterial species. The authors mentioned that all avocado parts had antimicrobial properties, with pulp (mesocarp) showing the highest activity. In addition, authors reported that the Gram-positive bacteria were more sensitive in comparison to the Gram-negative bacteria [104]. The Gram-negative bacteria have an extra protective outer membrane, which makes them more resistant to antibacterial agents compared to the Gram-positive bacteria [104,180]. β-sitosterol in avocados was also shown to play a key role in strengthening the immune system and the suppression of human immunodeficiency virus and other infections [181]. In particular, it has been found to enhance the proliferation of lymphocytes and natural killer cell activity for invading pathogens [181]. Salinas-Salazar et al. [177] investigated the antimicrobial activity of seed extracts of avocado enriched with acetogenin against L. monocytogenes and reported growth inhibition at 37 °C and 4 °C with MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) values of 15.6 and 7.8 mg/L, respectively. Acetogenins of avocados are fatty acid derivatives with a long unsaturated aliphatic chain (C19–C23) [182,183]. Owing to the structural similarities between acetogenins and fatty acids, authors hypothesized that acetogenins may penetrate the cell membranes of bacteria and physically disrupt their functionality [177]. Indeed, several compounds might be associated in the antimicrobial activity of avocado extracts. Polyphenols have been previously reported for their antimicrobial properties [184]. However, the contribution of the phenolic compounds toward the antimicrobial activity of avocado extracts needs to be investigated. Rodriguez-Carpena et al. [104] found that avocado pulp extract had a higher antimicrobial activity than peel and seed extracts, despite having lower polyphenol content. Future studies should be conducted to isolate individual phenolic compounds from different parts of avocado and investigate their antimicrobial properties.

Table 6.

Summary of studies that have been conducted that investigated the antimicrobial activity of Persea americana (avocado).

1.6. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of P. americana

Several studies have investigated the anti-inflammatory properties of avocado via modulation of inflammatory responses (Figure 9, Table 7). The aqueous extract of avocado leaves showed an anti-inflammatory effect in vivo by inhibiting carrageenan-induced rat paw oedema [185]. Persenone A, an active constituent of avocado, reduced inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in murine macrophages [173]. Similarly, (2R)-(12Z,15Z)-2-hydroxy-4-oxoheneicosa-12,15-dien-1-yl acetate, persenone A and B isolated from the avocado fruit, decreased the generation of nitric oxide in mouse macrophages [19]. Avocado oil contains a high amount of oleic acid and essential fatty acids. A study by [186] highlighted the wound-healing properties of avocado fruit oil by increasing collagen synthesis and decreasing inflammation in Wistar rats. They also reported that oleic acid was the predominant unsaturated fatty acid (47.20%) present in the fruit oil [186].

Table 7.

Anti-inflammatory properties of Persea americana (avocado) extracts, compounds, and combinations.

Inflammation in joints causes damage to the joint cartilage due to degenerative changes leading to a loss of joint function and stability [187]. Even though osteoarthritis (OA) is considered a non-inflammatory disease, recent studies have shown that inflammation is a leading cause for the initiation and continuation of the disease process [188]. Non-pharmacological agents that modulate the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators are highly promising as safe and effective ways to treat OA [189]. Avocado–soybean unsaponifiable (ASU) combination represents one of the most commonly used treatments for symptomatic OA [190]. ASU is a combination of avocado oil and soybean oil, which has been accepted as a medication/food supplement in many countries [191]. Three ratios of avocado (A) and soybean (S) unsaponifiable combinations (A:S = 1:2, 2:1, and 1:1) were studied for their anti-inflammatory properties on chondrocyte cells [192]. All the ratios showed significant inhibition compared to the individual extracts on collagenase, stromelysin, interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 8 (IL-8), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) release. In particular, 1:2 was found to be the most effective combination that exhibited chondroprotective effects in vivo by stimulating glycosaminoglycan and hydroxyproline synthesis and inhibiting the production of hydroxyproline in the granulomatous tissue [192]. In another study, the unsaponifiables of avocado alone indicated a significant chondroprotective effect [193]. Several preclinical and clinical studies conducted in the last few decades have revealed the modulation of different pathways and molecular targets associated with OA pathogenesis by ASU [194]. For instance, the anti-OA properties of ASU are mediated via the suppression of critical regulators of the inflammatory response such as iNOS/COX-2, and PGE-2 [195], and the reduction of catabolic enzymes (matrix metalloproteinases-3 and -13) and [190,196]. Gabay et al. [190] demonstrated the inactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases such as the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK 1/2) and NF-κB as the molecular mechanism of action for the anti-inflammatory effects of ASU. A recent study showed the potential bone repair properties of ASU by the modulation of molecular targets Rankl and Il1β, RANKL, and TRAP using a rat model [197]. Sterols, the major bioactive components of ASU, have also shown anti-inflammatory activity in articular chondrocytes [198].

A significant reduction of articular cartilage erosion and synovial hemorrhage compared to placebo was observed in horses using ASU extracts [199]. However, the extracts did not reduce signs of pain or lameness in horses. In humans, NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) consumption was reduced in patients with lower limb OA after six weeks of ASU consumption [200]. Furthermore, ASU significantly reduced the progression of joint space loss in patients with hip OA [201]. Another study by Maheu et al. [202] demonstrated slow radiographic progression in hip OA using ASU treatment. They also reported that the treatment was well tolerated by patients, even though the clinical outcome did not change. Interestingly, a recent study showed that the intake of ASU extract decreased the pain symptoms and an improved the quality of life in patients with OA of the temporomandibular joint [203].

Other studies have combined ASU with bioactive compounds such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and α-lipoic acid (LA) [189,204,205]. Interestingly, contrary to previous research, Heinecke et al. [204] reported a slight inhibition of COX-2 expression and PGE2 production in activated chondrocytes. However, when ASU was combined with EGCG, both mediators were more significantly inhibited than their mono treatments [204]. Another study by Ownby et al. demonstrated that this combination inhibited the gene expression of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor- α (TNF-α), IL-6, COX-2, and IL-8 in activated chondrocytes [189]. The combination of ASU with LA showed a more significant suppression of PGE2 production in activated chondrocytes than ASU or LA alone [205].

The implementation of ASU in the treatment of other inflammatory diseases has also been explored. In particular, ASU has shown efficacy against periodontal disease by modulating the expression of transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1), TGF-β2, and bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) [206]. Additionally, a recent study demonstrated that ASU can repair periodontal disease within seven days [207]. These results underline the significant anti-inflammatory properties of avocado mediated via multiple signal transduction pathways and their role in the potential treatment of various inflammatory diseases.

1.7. Effect of P. americana on Cardiovascular Health and Diabetes

Clinical have shown a positive effect on cardiovascular health and lipid profiles with the presence of avocado in the diet [65,208]. It has been observed that the intake of avocado in a balanced diet had a great impact on preventing cardiovascular diseases as a result of the low cholesterol levels. Grant in 1959 [209] conducted the first avocado clinical trial where 0.5 to 1.5 avocados were incorporated in the diet of 16 male patients, and showed a significant decrease or the same total serum cholesterol level with no increase in weight. In particular, avocado phytosterols were found to inhibit cholesterol absorption and synthesis by mimicking its molecular structure, which resulted in lowered total cholesterol levels in the body [210]. A randomized, controlled trial was conducted on 45 obese patients where the patients were categorized into three major groups—(i) moderate-fat diet, (ii) low-fat diet, and (iii) moderate-fat diet with the incorporation of one avocado (AV). A major decrease in the total cholesterol levels in all the groups was observed from the baseline, while the AV group had a greater reduction in LDL-C and non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL) [67]. According to the results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), people who consumed avocados had an improved diet quality due to increased vegetable intake and reduced sugar consumption [211]. Therefore, vascular damage and heart diseases can be reduced to a great extent by the inclusion of avocados in a diet [211]. In another study, the inclusion of avocado in a meal increased satisfaction with a decrease in actual eating in obese adults, which indirectly had a positive effect on the body mass index (BMI) and reduced the chances of cardiovascular diseases [212]. An increase in the satisfaction (by 23%), decrease in eating (by 28%), and blood insulin were observed in comparison to the control group [212]. A systematic review was conducted by Silva Caldas et al. [213] to study the effects of avocado on the cardiovascular health of adults, and after including eight articles from the initial 234 studies, they concluded that the presence of MUFA, specifically oleic fatty acid in avocado has been linked with its cardioprotective effects.

A study done by Carvajal-Zarrabal et al. [214] found out that avocado oil had a significant contribution toward the metabolic syndrome, as it reduced the inflammatory events and exhibited positive results in the biochemical indicators when they administered avocado oil in 25 rats divided into various groups such as a control group, a basic diet group with 30% sucrose, and a basic diet plus olive oil and avocado oil. Extensive biochemical markers were studied, and the presence of avocado oil seemed to have reduced the triglycerides and LDL levels, which reduced the cardiovascular risks [214]. Cohort studies performed recently on the BMI of individuals after the intake of avocados showed a considerable reduction in weight gain compared to the control, which consecutively lowered various cardiovascular problems associated with obesity [215]. Another report in 2018 [216] analyzed studies on the intake of avocado and cardiovascular risks from MEDLINE, Cochrane Central, and the Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau, and found a significant increase in HDL cholesterol concentration with heterogeneity associated with avocado intake. However, no significant reduction in LDL cholesterol and serum total cholesterol was mentioned in this report [216].

The indigestible carbohydrates abundantly found in avocado are reported to prevent diabetes and regulate blood cholesterol [217]. The glycemic index can be defined as a comparative ranking of carbohydrate in foods according to their effect on blood sugar levels [218]. Despite its carbohydrate content, the glycemic index rating of avocado is quite low. In rats, various aqueous concentrations of P. americana seed extract exhibited hypoglycemic and antihyperglycemic effects by significantly decreasing the blood glucose levels [219], highlighting its potential in the management of diabetes mellitus. Another study conducted to investigate the effect of avocado paste on rats with a hypercholesterolemic diet with high fructose showed lower levels of blood sugar and significant reduction of fat accumulation in the liver, which was attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds (polyphenols, fiber, and carotenoids) [220]. Investigation on the inhibitory effects of phenolic extract from the avocado pulp, leaves, and seed on various type 2 diabetes enzymes (α-amylase and α-glucosidase) was also performed [221]. The peel extract exhibited the highest inhibition against α-amylase and α-glucosidase, while the leaf extract significantly inhibited the α-glucosidase. In a recent study, the glycemic and lipoprotein profiles of the obese middle-aged adult were improved when the carbohydrate was replaced with avocados in a meal [222]. The participants were divided into three different groups: control group (0 g), half avocado (half-A, 68 g), and whole avocado (whole-A, 136 g). In comparison to the control group, the half-A and whole-A group showed decreased glycemic and insulinemic response over 6 h [222].

1.8. Bioavailability and Pharmacokinetic of Compounds from P. americana

Avocado is a relatively unique fruit, containing high levels of water and fat-soluble vitamins, plant sterols, MUFA, and phytochemicals [223]. Avocado has been shown to improve the absorption of nutrients when used in combination with other foods and supplements [224]; however, research on the pharmacokinetics of the avocado components alone is limited.

Vitamin A is fat-soluble in nature and present in many foods as retinol and in its provitamin A form (carotenes). In particular, liver, fish, and cheese are rich sources of vitamin A. Carotenes (provitamin A) are converted to vitamin A in the body. However, plant-based foods typically present a challenging matrix for the utilization of vitamin A, hindering the absorption and conversion of provitamin A to vitamin A [225]. Many commonly consumed plant-based foods contain higher levels of provitamin A such as sweet potato (709 µg/100 g), carrots (835 µg/100 g), and spinach (469 µg/100 g), especially compared to avocado (7 µg/100 g) [223]. Nevertheless, the levels of vitamins in the food are trivial if not absorbed and converted to their active chemical forms for the body to utilize. The absorption of provitamin A from plant sources is typically poor. In an in vitro digestion model, the accessibility of β-carotene in raw carrots was 1–3% and lycopene was <1% [226]. The consumption of lipid-rich food has been shown to improve the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, including vitamin A [227]. The presence of soluble fats during digestion facilitates the formations of mixed micelles, which facilitate absorption [228].

The absorptions of provitamin A including β-carotene, α-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein, and zeaxanthin were enhanced when co-consumed with avocado. This can perhaps be attributed to the high MUFA content of avocado. In salsa, the absorption of lycopene and β-carotene was increased by 4.4 and 2.6 times respectively when avocado was added. In salad (150 g), the addition of avocado (24 g) increased the absorption of α and β-carotene and lutein by 7.2, 15.3, and 5.1 times, respectively [224]. In addition to the improved absorption, avocados were shown to enhance the utilization of provitamin A by increasing the conversion rate to vitamin A in participants with low conversion efficacy [229]. The enhanced absorption of provitamin A has been attributed to the improved formation of mixed micelles in the lumen, increasing solubility and facilitating uptake by enterocytes. Improved vitamin A uptake has been observed with other high lipid foods such as eggs and oil [230]. Likewise, the consumption of salad rich in carotenes, with canola oil, resulted in significantly higher carotene concentrations in chylomicrons [231]. As avocado is a rich source of fat and high in monosaturated fatty acids, it presents an alternative from sources high in unsaturated fats.

Avocado is the most concentrated source of β-sitosterol in commonly consumed Western fruits [79]. Plant sterols share similar chemical structures with cholesterol; however, they are poorly absorbed compared to cholesterol, (with about 10% systematically absorbed compared to 50–60% for cholesterol) [232]. Similar to other lipophilic compounds, phytosterols are incorporated into mixed micelles before being taken up by enterocytes [233]. Plant steroids may assist in lowering cholesterol absorption by acting as a competitive inhibitor. Interestingly, plant sterols have also been observed to lower dietary carotene plasma levels by 10–20% [234]. As avocados have been reported to increase carotene absorption and subsequent plasma levels, this effect may be overcome by the benefit of the other lipid components present. Due to its unique fruit matrix high in plant sterols and MUFA, avocados may provide an enhanced absorption of lipophilic compounds compared to other fruits and vegetables. As established for vitamin A and carotene, it is likely that the absorption of other lipophilic compounds may similarly be enhanced by consumption with avocado. Within avocado, this may apply to vitamin E, vitamin K, chlorophylls, and phytochemicals such as acetogenins. Further pharmacokinetic research is necessary to determine if the absorption of other lipophilic compounds is enhanced in combination with avocado. The current literature does not provide any information regarding the effect of avocado matrix on the absorption of water-soluble vitamins and phytochemicals. Moreover, further pharmacokinetic research should be directed to understand the bioavailability of pharmaceutically promising phytochemicals such as acetogenins from avocado.

2. Conclusions and Future Direction

Several preclinical studies performed in the last few decades lay emphasis on the unique nutritional and phytochemical composition of avocado and their potential in the treatment and prevention of different diseases. Some studies have underlined its importance as the source of lead molecules for drug discovery due to the abundance of novel chemical skeletons. The cumulative effects of avocado components in the prevention and treatment of oxidative stress and age-related degenerative diseases are also indicated in a few studies. However, more comprehensive in vitro, in vivo, and clinical investigations are fundamental to significantly expand the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of action of its phytochemicals for developing subsequent therapeutic and nutritional interventions against cancer, diabetes, inflammatory, microbial, and cardiovascular diseases. Interestingly, despite its popularity as a “superfood”, clinical studies evaluating the therapeutic potential of avocado for the prevention and management of different ailments are limited in the literature. More investigations to understand the bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of avocado phytochemicals and antioxidants are also crucial to determine their clinical efficacy and potential toxicity. Regardless of the recent food trends and marketing gimmicks of “superfoods”, variety is fundamental for a balanced healthy diet. As many studies have revealed the complex synergistic interactions among different phytochemicals present in food matrices, studies to understand the possible synergy between bioactive compounds from avocado and other fruit and vegetables will help formulate diet-based preventive strategies for many diseases. A few reports have indicated the role of avocado in improving the bioavailability of nutrients from other plant-based foods. Therefore, consuming avocados with other fruit and vegetables as a part of the diet can be beneficial to human health.

Author Contributions

D.J.B., conceptualization, writing, review and editing, supervision; M.A.A., conceptualization and writing; S.P., conceptualization and writing; M.L., conceptualization and writing; A.B., conceptualization and writing; O.A.D., conceptualization and writing; M.S.B. conceptualization and writing; C.G.L., writing, review and editing; K.P., conceptualization, writing, review and editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

As a medical research institute, the NICM Health Research Institute receives research grants and donations from foundations, universities, government agencies, individuals, and industry. Sponsors and donors also provide untied funding for work to advance the vision and mission of the institute. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bergh, B.; Ellstrand, N. Taxonomy of the avocado. Calif. Avocado Soc. Yearb. 1986, 70, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia, F.J.; Hidalgo, G.I.; Villasante, J.; Ramis, X.; Almajano, M.P. Avocado seed: A comparative study of antioxidant content and capacity in protecting oil models from oxidation. Molecules 2018, 23, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, A.K.; Wolstenholme, B.N. Avocado. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Taulavuori, K.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R.; Hyöky, V.; Taulavuori, E. Blue Mood for Superfood. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 1934578X1300800627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, G.; Martin-Smith, J.; Sullivan, P. The Avocado Hand. Ir. Med. J. 2017, 110, 658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Avocados; Iowa State University in Ames: Ames, IA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Combined Chemical Dictionary 23.1; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; Available online: http://ccd.chemnetbase.com/faces/chemical/ChemicalSearch.xhtml;jsessionid=7B7405700267BD91E58E52C6333BF438 (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- The Human Metabolome Database. 2019. Available online: http://www.hmdb.ca/ (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Yasir, M.; Das, S.; Kharya, M.D. The phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Persea americana Mill. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.H.; Tseng, C.K.; Wu, H.C.; Wei, C.K.; Lin, C.K.; Chen, I.S.; Chang, H.S.; Lee, J.C. Avocado (Persea americana) fruit extract (2R,4R)-1,2,4-trihydroxyheptadec-16-yne inhibits dengue virus replication via upregulation of NF-kappaB-dependent induction of antiviral interferon responses. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adikaram, N.K.B.; Ewing, D.F.; Karunaratne, A.M.; Wijeratne, E.M.K. Antifungal Compounds from Immature Avocado Fruit Peel. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, F.; Nagafuji, S.; Okawa, M.; Kinjo, J.; Akahane, H.; Ogura, T.; Martinez-Alfaro, M.A.; Reyes-Chilpa, R. Trypanocidal Constituents in Plants 5. Evaluation of some mexican plants for their trypanocidal activity and active constituents in the seeds of Persea americana. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 1314–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.C.; Chang, H.S.; Peng, C.F.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, I.S. Secondary metabolites from the unripe pulp of Persea americana and their antimycobacterial activities. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 2904–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domergue, F.; Helms, G.L.; Prusky, D.; Browse, J. Antifungal compounds from idioblast cells isolated from avocado fruits. Phytochemistry 2000, 54, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-H.; Tsai, Y.-F.; Huang, T.-T.; Chen, P.-Y.; Liang, W.-L.; Lee, C.-K. Heptadecanols from the leaves of Persea americana var. americana. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, S.D.; Carman, R.M. Synthesis of the Avocado Antifungal,(Z, Z)-2-Hydroxy-4-oxohenicosa-12, 15-dien-1-yl Acetate. Aust. J. Chem. 1994, 47, 1661–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Millar, J.G.; Trumble, J.T. Isolation, Identification, and Biological Activity of Isopersin, a New Compound from Avocado Idioblast Oil Cells. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 1168–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashman, Y.; Néeman, I.; Lifshitz, A. New compounds from avocado pear. Tetrahedron 1969, 25, 4617–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.K.; Murakami, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Takeda, N.; Yoshizumi, H.; Ohigashi, H. Novel Nitric Oxide and Superoxide Generation Inhibitors, Persenone A and B, from Avocado Fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1557–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Wong, C.-H.; Liu, Y.-W.; Lin, Y.-S.; Wang, Y.-D.; Hsui, Y.-R. Cytotoxic Constituents of the Stems of Cinnamomum subavenium. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberlies, N.H.; Rogers, L.L.; Martin, J.M.; McLaughlin, J.L. Cytotoxic and insecticidal constituents of the unripe fruit of Persea americana. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Arellano, H.F.; Jimenez-Del-Rio, M.; Velez-Pardo, C. Neuroprotective effects of methanolic extract of avocado Persea americana (var. Colinred) peel on paraquat-induced locomotor impairment, lipid peroxidation and shortage of life span in transgenic knockdown parkin drosophila melanogaster. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 1986–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Jerz Mdel, R.; Villanueva, S.; Jerz, G.; Winterhalter, P.; Deters, A.M. Persea americana Mill. Seed: Fractionation, Characterization, and Effects on Human Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 391247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.Y.; Arteaga, J.R.; Zhang, Q.; Huerta, S.; Go, V.L.; Heber, D. Inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth by an avocado extract: Role of lipid-soluble bioactive substances. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2005, 16, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Hejazi, V.; Abbas, M.; Kamboh, A.A.; Khan, G.J.; Shumzaid, M.; Ahmad, F.; Babazadeh, D.; FangFang, X.; Modarresi-Ghazani, F.; et al. Chlorogenic acid (CGA): A pharmacological review and call for further research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Paul, S.; Dutta, S.; Boujedaini, N.; Khuda-Bukhsh, A.R. Anti-oncogenic potentials of a plant coumarin (7-hydroxy-6-methoxy coumarin) against 7,12-dimethylbenz [a] anthracene-induced skin papilloma in mice: The possible role of several key signal proteins. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2010, 8, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Kunesch, G.; Martin-Tanguy, J.; Negrel, J.; Paynot, M.; Carre, M. Effect of cinnamoyl putrescines on in vitro cell multiplication and differentiation of tobacco explants. Plant Cell. Rep. 1985, 4, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, I.; Castelo-Branco, V.N.; Guimarães, B.M.; Silva, L.d.O.; Peixoto, V.O.D.S.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Freitas, S.P.; Torres, A.G. Hass avocado (Persea americana Mill.) oil enriched in phenolic compounds and tocopherols by expeller-pressing the unpeeled microwave dried fruit. Food Chem. 2019, 286, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.; Gabai, M.; Lifshitz, A.; Sklarz, B. Structures of some carotenoids from the pulp of Persea americana. Phytochemistry 1974, 13, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.; Gabai, M.; Lifshitz, A.; Sklarz, B. Carotenoids in pulp, peel and leaves of Persea americana. Phytochemistry 1973, 12, 2259–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Saona, C.R.; Maynard, D.F.; Phillips, S.; Trumble, J.T. Alkylfurans: Effects of Alkyl Side-Chain Length on Insecticidal Activity. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Millar, J.G.; Maynard, D.F.; Trumble, J.T. Novel Antifeedant and Insecticidal Compounds from Avocado Idioblast Cell Oil. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 867–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, B.M.; Terrero, D. Alkene-γ-lactones and avocadofurans from Persea indica: A revision of the structure of majorenolide and related lactones. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblat, G.; Kagan, H.M.; Shah, M.A.; Spiteller, G.; Neeman, I. Chemical characterization of lysyl oxidase inhibitor from avocado seed oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1995, 72, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.; Zentmyer, G.; Pettus, J.; Sills, J.; Keen, N.; Sing, V. Borbonol from Persea spp.-chemical properties and antifungal activity against Phytophthora cinnamomi. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 1980, 16, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falodun, A.; Engel, N.; Kragl, U.; Nebe, B.; Langer, P. Novel anticancer alkene lactone from Persea americana. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 51, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Lo, Y.-C.; Wu, B.-N.; Wang, H.-M.; Lo, W.-L.; Yen, C.-M.; Lin, R.-J. Anticancer Activity of Isoobtusilactone A from Cinnamomum kotoense: Involvement of Apoptosis, Cell-Cycle Dysregulation, Mitochondria Regulation, and Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Maynard, D.F.; Phillips, S.; Trumble, J.T. Avocadofurans and their tetrahydrofuran analogues: Comparison of growth inhibitory and insecticidal activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3642–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, B.M.; González-Coloma, A.; Gutiérrez, C.; Terrero, D. Insect Antifeedant Isoryanodane Diterpenes from Persea indica. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Tao, Y.; Reisman, S.E. 16-Step Synthesis of the Isoryanodane Diterpene (+)-Perseanol. ChemRxiv. Preprint. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Coloma, A.; Hernandez, M.G.; Perales, A.; Fraga, B.M. Chemical ecology of canarian laurel forest: Toxic diterpenes from Persea indica (Lauraceae). J. Chem. Ecol. 1990, 16, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, B.M.; Terrero, D.; Gutiérrez, C.; González-Coloma, A. Minor diterpenes from Persea indica: Their antifeedant activity. Phytochemistry 2001, 56, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzĺez-Coloma, A.; Cabrera, R.; Socorro Monzón, A.R.; Frag, B.M. Persea indica as a natural source of the insecticide ryanodol. Phytochemistry 1993, 34, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, R.M.; Hudson, C.S. Proof of the Structure and Configuration of Perseulose (L-Galaheptulose). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1939, 61, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephton, H.H.; Richtmyer, N.K. The isolation of D-erythro-L-galacto-nonulose from the avocado, together with its synthesis and proof of structure through reduction to D-arabino-D-manno-nonitol and D-arabino-D-gluco-nonitol. Carbohyd. Res. 1966, 2, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephton, H.H.; Richtmyer, N.K. Isolation of D-erythro-L-gluco-Nonulose from the Avocado1. J. Org. Chem. 1963, 28, 2388–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, A.J.; Richtmyer, N.K. The Isolation of an octulose and an octitol from natural sources: D-glycero-D-manno-Octulose and D-erythro-D-galacto-octitol from the avocado and D-glycero-D-manno-octulose from Sedum species1,2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 3428–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ian-Lih, T.; Chih-Feng, H.; Chang-Yih, D.; Ih-Sheng, C. Cytotoxic neolignans from Persea obovatifolia. Phytochemistry 1996, 43, 1261–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, W. Asymmetric synthesis of machilin C and its analogue. Chem. Pap. 2010, 64, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.S. Lignans neolignans, and related compounds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1993, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.-L.; Hsieh, C.-F.; Duh, C.-Y.; Chen, I.-S. Further study on the chemical constituents and their cytotoxicity from the leaves of Persea obovatifolia. Chin. Pharm. J. 1999, 51, 335–346. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, I.-L.; Hsieh, C.-F.; Duh, C.-Y. Additional cytotoxic neolignans from Persea obovatifolia. Phytochemistry 1998, 48, 1371–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda-Boza, S.; Delhvi, S.; Cassels, B.K. An aryltetralin lignan from Persea lingue. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 2357–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-F.; Isogai, A.; Kamikado, T.; Murakoshi, S.; Sakurai, A.; Tamura, S. Isolation and structure elucidation of growth inhibitors for silkworm larvae from avocado leaves. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1975, 39, 1167–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kharrassi, Y.; Samadi, M.; Lopez, T.; Nury, T.; El Kebbaj, R.; Andreoletti, P.; El Hajj, H.I.; Vamecq, J.; Moustaid, K.; Latruffe, N.; et al. Biological activities of Schottenol and Spinasterol, two natural phytosterols present in argan oil and in cactus pear seed oil, on murine miroglial BV2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohsaki, A.; Kubota, T.; Asaka, Y. Perseapicroside A, hexanorcucurbitacin-type glucopyranoside from Persea mexicana. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 1330–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascinu, S.; Catalano, V.; Cordella, L.; Labianca, R.; Giordani, P.; Baldelli, A.M.; Beretta, G.D.; Ubiali, E.; Catalano, G. Neuroprotective effect of reduced glutathione on oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 3478–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, J.F.; Bowman, A.; Perren, T.; Wilkinson, P.; Prescott, R.J.; Quinn, K.J.; Tedeschi, M. Glutathione reduces the toxicity and improves quality of life of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer treated with cisplatin: Results of a double-blind, randomised trial. Ann. Oncol. 1997, 8, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flagg, E.W.; Coates, R.J.; Jones, D.P.; Byers, T.E.; Greenberg, R.S.; Gridley, G.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Blot, W.J.; Haber, M.; Preston-Martin, S.; et al. Dietary Glutathione Intake and the Risk of Oral and Pharyngeal Cancer. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1994, 139, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, S.; Vajczikova, I. Variations in the essential oil composition of Persea bombycina (King ex Hook. f.) Kost and its effect on muga silkworm (Antheraea assama Ww)—A new report. Indian J. Chem. B 2003, 42B, 641–647. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Avocados, Raw, California. FoodData Central. 2019. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/171706/nutrients (accessed on 22 September 2019).

- Duarte, P.F.; Chaves, M.A.; Borges, C.D.; Mendonça, C.R.B. Avocado: Characteristics, health benefits and uses. Cienc. Rural 2016, 46, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duester, K.C. Avocados a look beyond basic nutrition for one of nature’s whole foods. Nutr. Today 2000, 35, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Atkinson, F.; Petocz, P.; Willett, W.C.; Brand-Miller, J.C. Prediction of postprandial glycemia and insulinemia in lean, young, healthy adults: Glycemic load compared with carbohydrate content alone. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, M.L.; Davenport, A.J. Hass avocado composition and potential health effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landahl, S.; Meyer, M.D.; Terry, L.A. Spatial and temporal analysis of textural and biochemical changes of imported avocado cv. Hass during fruit ripening. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 7039–7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Bordi, P.L.; Fleming, J.A.; Hill, A.M.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Effect of a moderate fat diet with and without avocados on lipoprotein particle number, size and subclasses in overweight and obese adults: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e001355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranade, S.S.; Thiagarajan, P. A review on Persea americana Mill.(avocado)-its fruits and oil. Int. J. Pharmtech Res. 2015, 8, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- de Melo, M.F.F.T.; Pereira, D.E.; Moura, R.d.L.; da Silva, E.B.; de Melo, F.A.L.T.; Dias, C.d.C.Q.; Silva, M.d.C.A.; de Oliveira, M.E.G.; Viera, V.B.; Pintado, M.M.E.; et al. Maternal supplementation with avocado (Persea americana Mill.) pulp and oil alters reflex maturation, physical development, and offspring memory in rats. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, C.P.; Bernal, E.J.; Velásquez, M.A.; Cartagena, V.J.R. Fatty acid content of avocados (Persea americana Mill. cv. Hass) in relation to orchard altitude and fruit maturity stage. Agron. Colomb. 2015, 33, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swisher, H.E. Avocado oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1988, 65, 1704–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.T.; Pizzorno, J. The Encyclopedia of Healing Foods; Simon and Schuster: NewYork, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lidia, D.-A.; Alicia, O.-M.; Felipe, G.-O. Avocado. In Tropical and Subtropical Fruits; Muhammad, S., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 435–454. [Google Scholar]

- Dabas, D.; Shegog, R.M.; Ziegler, G.R.; Lambert, J.D. Avocado (Persea americana) seed as a source of bioactive phytochemicals. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 6133–6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, H.; Moyer, T. Food as Medicine: Avocado (Persea americana, Lauraceae). In HerbalEGram; American Botanical Council: Austin, TX, USA, 2017; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer, B.; Natoli, S.; Liew, G.; Flood, V.M. Lutein and Zeaxanthin-Food Sources, Bioavailability and Dietary Variety in Age-Related Macular Degeneration Protection. Nutrients 2017, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein Alice, H.; Deckelbaum Richard, J. Stanol/Sterol Ester–Containing Foods and Blood Cholesterol Levels. Circulation 2001, 103, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weihrauch, J.L.; Gardner, J.M. Sterol content of foods of plant origin. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1978, 73, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duester, K.C. Avocado fruit is a rich source of beta-sitosterol. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2001, 101, 404–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarbakhsh, S.; Schachter, M. Vitamins and cardiovascular disease. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuyan, D.J.; Vuong, Q.V.; Chalmers, A.C.; van Altena, I.A.; Bowyer, M.C.; Scarlett, C.J. Investigation of phytochemicals and antioxidant capacity of selected Eucalyptus species using conventional extraction. Chem. Pap. 2016, 70, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Xu, B.T.; Xu, X.R.; Qin, X.S.; Gan, R.Y.; Li, H.B. Antioxidant capacities and total phenolic contents of 56 wild fruits from South China. Molecules 2010, 15, 8602–8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, G.; Santos, J.; Freire, M.S.; Antorrena, G.; González-Álvarez, J. Extraction of antioxidants from eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) bark. Wood Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bostic, T.R.; Gu, L. Antioxidant capacities, procyanidins and pigments in avocados of different strains and cultivars. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Khuong, T.; Lovatt, C.J. Effect of harvest date on the nutritional quality and antioxidant capacity in ‘Hass’ avocado during storage. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, F.J.; Corral-Pérez, J.J.; Almajano, M.P. Avocado seed: Modeling extraction of bioactive compounds. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 85, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyadzhieva, S.; Georgieva, S.; Angelov, G. Optimization of the extraction of natural antioxidants from avocado seeds. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 50, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Boyadzhieva, S.; Georgieva, S.; Angelov, G. Recovery of antioxidant phenolic compounds from avocado peels by solvent extraction. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 50, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano, V.; Avellone, G.; Bongiorno, D.; Indelicato, S.; Massenti, R.; Lo Bianco, R. Quantitative evaluation of the phenolic profile in fruits of six avocado (Persea americana) cultivars by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-heated electrospray-mass spectrometry. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1302–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.G.; Borrás-Linares, I.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Segura-Carretero, A. Comprehensive identification of bioactive compounds of avocado peel by liquid chromatography coupled to ultra-high-definition accurate-mass Q-TOF. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, J.G.; Borrás-Linares, I.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Segura-Carretero, A. Comprehensive characterization of phenolic and other polar compounds in the seed and seed coat of avocado by HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 752–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado-Fernandez, E.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, A. Profiling LC-DAD-ESI-TOF MS method for the determination of phenolic metabolites from avocado (Persea americana). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2255–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado-Fernández, E.; Pacchiarotta, T.; Mayboroda, O.A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A. Quantitative characterization of important metabolites of avocado fruit by gas chromatography coupled to different detectors (APCI-TOF MS and FID). Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosińska, A.; Karamać, M.; Estrella, I.; Hernández, T.; Bartolomé, B.; Dykes, G.A. Phenolic Compound Profiles and Antioxidant Capacity of Persea americana Mill. Peels and Seeds of Two Varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 4613–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, C.R.; Vasconcelos, C.F.; Costa-Silva, J.H.; Maranhao, C.A.; Costa, J.; Batista, T.M.; Carneiro, E.M.; Soares, L.A.; Ferreira, F.; Wanderley, A.G. Anti-diabetic activity of extract from Persea americana Mill. leaf via the activation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cobo, A.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Pasini, F.; Caboni, M.F.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS and HPLC-FLD-MS as valuable tools for the determination of phenolic and other polar compounds in the edible part and by-products of avocado. Lwt Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremocoldi, M.A.; Rosalen, P.L.; Franchin, M.; Massarioli, A.P.; Denny, C.; Daiuto, É.R.; Paschoal, J.A.R.; Melo, P.S.; Alencar, S.M.d. Exploration of avocado by-products as natural sources of bioactive compounds. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalf, M.I.; Alansari, W.S.; Ibrahim, E.A.; Elhalwagy, M.E.A. Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of avocado (Persea americana) fruit and seed extract. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, D.A.V.; Helmann, G.A.B.; Detoni, A.M.; Carvalho, S.L.C.D.; Aguiar, C.M.D.; Martin, C.A.; Tiuman, T.S.; Cottica, S.M. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity and preliminary toxicity analysis of four varieties of avocado (Persea americana Mill.). Braz. J. Food Technol. 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertling, I.; Tesfay, S.; Bower, J. Antioxidants in ‘Hass’ avocado. South Afr. Avocado Grow. Assoc. Yearb. 2007, 30, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Oliver, M.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Pedroza-Islas, R.; Ponce-Alquicira, E. Optimization of the antioxidant and antimicrobial response of the combined effect of nisin and avocado byproducts. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiuto, É.R.; Tremocoldi, M.A.; Alencar, S.M.D.; Vieites, R.L.; Minarelli, P.H. Composição química e atividade antioxidante da polpa e resíduos de abacate ‘Hass’. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2014, 36, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, G.; Adelusi, T.; Akinyemi, A. Inhibitory effect of phenolic extract from leaf and fruit of avocado pear (Persea americana) on Fe2+ induced lipid peroxidation in rats’pancreas in vitro. Futa J. Res. Sci. 2013, 2, 276–286. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Carpena, J.G.; Morcuende, D.; Andrade, M.J.; Kylli, P.; Estevez, M. Avocado (Persea americana Mill.) phenolics, in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, and inhibition of lipid and protein oxidation in porcine patties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 5625–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soong, Y.-Y.; Barlow, P.J. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of selected fruit seeds. Food Chem. 2004, 88, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinha, A.F.; Moreira, J.; Barreira, S.V. Physicochemical parameters, phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of the algarvian avocado (Persea americana Mill.). J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 5, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-Fernández, E.; Pacchiarotta, T.; Gómez-Romero, M.; Schoenmaker, B.; Derks, R.; Deelder, A.M.; Mayboroda, O.A.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Ultra high performance liquid chromatography-time of flight mass spectrometry for analysis of avocado fruit metabolites: Method evaluation and applicability to the analysis of ripening degrees. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 7723–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Rodríguez, J.A.; Molina-Corral, F.J.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Olivas, G.I.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Effect of maturity stage on the content of fatty acids and antioxidant activity of ‘Hass’ avocado. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, N.; Amarillo, M.; Martinez, N.; Grompone, M. Improvement in the extraction of Hass avocado virgin oil by ultrasound application. J. Food Res. 2018, 7, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Lee, R.P.; Gao, K.; Byrns, R.; Heber, D. California Hass avocado: Profiling of carotenoids, tocopherol, fatty acid, and fat content during maturation and from different growing areas. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10408–10413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza, L.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; de Pascual-Teresa, S.; de Ancos, B.; Cano, M.P. Fatty Acids, Sterols, and Antioxidant Activity in Minimally Processed Avocados during Refrigerated Storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 3204–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Huber, D.J.; Rao, J. Antioxidant systems of ripening avocado (Persea americana Mill.) fruit following treatment at the preclimacteric stage with aqueous 1-methylcyclopropene. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 76, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.S.; Marques, L.G.; Gomes, E.d.B.; Narain, N. Lyophilization of Avocado (Persea americana Mill.): Effect of Freezing and Lyophilization Pressure on Antioxidant Activity, Texture, and Browning of Pulp. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldera-Silva, A.; Seyfried, M.; Campestrini, L.H.; Zawadzki-Baggio, S.F.; Minho, A.P.; Molento, M.B.; Maurer, J.B.B. Assessment of anthelmintic activity and bio-guided chemical analysis of Persea americana seed extracts. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 251, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaide, E.R.; Zabot, G.L.; Tres, M.V.; Martins, R.F.; Fagundez, J.L.; Nunes, L.F.; Druzian, S.; Soares, J.F.; Dal Prá, V.; Silva, J.R.F.; et al. Yield, composition, and antioxidant activity of avocado pulp oil extracted by pressurized fluids. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 102, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, M.A.Z.; Alicieo, T.V.R.; Pereira, C.M.P.; Ramis-Ramos, G.; Mendonça, C.R.B. Profile of Bioactive Compounds in Avocado Pulp Oil: Influence of the Drying Processes and Extraction Methods. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabath Pathirana, U.; Sekozawa, Y.; Sugaya, S.; Gemma, H. Changes in lipid oxidation stability and antioxidant properties of avocado in response to 1-MCP and low oxygen treatment under low-temperature storage. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Foudjo, B.U.S.; Kansci, G.; Fokou, E.; Genot, C. Prediction of critical times for water-extracted avocado oil heated at high temperatures. Int. J.Biol. Chem. Sci. 2018, 12, 2053–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales-García, J.E.; del Rosario García-Mateos, M.; Martínez-López, E.; Barrientos-Priego, A.F.; Ybarra-Moncada, M.C.; Ibarra-Estrada, E.; Méndez-Zúñiga, S.M.; Becerra-Morales, D. Anthocyanin and Oil Contents, Fatty Acids Profiles and Antioxidant Activity of Mexican Landrace Avocado Fruits. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2019, 74, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corzzini, S.C.S.; Barros, H.D.F.Q.; Grimaldi, R.; Cabral, F.A. Extraction of edible avocado oil using supercritical CO2 and a CO2/ethanol mixture as solvents. J. Food Eng. 2017, 194, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumreich, F.D.; Borges, C.D.; Mendonça, C.R.B.; Jansen-Alves, C.; Zambiazi, R.C. Bioactive compounds and quality parameters of avocado oil obtained by different processes. Food Chem. 2018, 257, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Sanchez, D.; Silva-Platas, C.; Rojo, R.P.; Garcia, N.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Garcia-Rivas, G.; Hernandez-Brenes, C. Activity-guided identification of acetogenins as novel lipophilic antioxidants present in avocado pulp (Persea americana). J. Chromatogr. B 2013, 942–943, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, F.S.; Sánchez, S.P.; Iradi, M.G.G.; Azman, N.A.M.; Almajano, M.P. Avocado Seeds: Extraction Optimization and Possible Use as Antioxidant in Food. Antioxidants 2014, 3, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingne, F.K.; Tsafack, H.D.; Boungo, G.T.; Mboukap, A.; Azia, A. Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Young and Mature Mango (Mangifera indica) and Avocado (Persea americana) Leaves Extracts. J. Food. Stab. 2018, 1, 14–27. [Google Scholar]