Abstract

Seagrass meadows are essential coastal ecosystems that provide key ecological services, including carbon sequestration, sediment stabilization, and shoreline protection. Increasing threats from natural and anthropogenic stressors highlight the need for efficient, reproducible, and non-invasive monitoring solutions. This study evaluates the performance of low-cost commercial drones for seagrass assessment in shallow coastal waters, with an emphasis on freely accessible mission-planning and photogrammetric workflows. Field surveys were conducted along the Calabrian coast (southern Italy), where automated flight paths were generated using the software WaypointMap, and high-resolution orthophotos were generated using the WebODM software and subsequently analyzed in QGIS for seagrass patch detection, mapping, and surface estimation. The methodological pipeline is described in detail to facilitate full reproducibility. Compared with traditional diver-based methods, this workflow offers faster data collection, broader spatial coverage, and minimal environmental disturbance. Although some limitations remain, the results demonstrate that combining low-cost drones with open-source tools provides a practical and scalable solution for routine monitoring. This approach has strong potential for integration into routine coastal habitat assessment, supports early impact detection, and contributes to evidence-based conservation and management strategies.

1. Introduction

Seagrass meadows are among the most productive and ecologically significant marine ecosystems on Earth [1]. They play a pivotal role in maintaining coastal biodiversity and environmental stability in shallow coastal waters [2]. Seagrasses provide numerous ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration, sediment stabilization, and nutrient cycling, and serve as nursery habitat for commercially important fish and invertebrate species [3,4,5,6]. Despite their importance, seagrass ecosystems remain among the least protected coastal habitats and are severely threatened [7]. Global assessment reports alarming declines, with losses exceeding 10% per decade between 1970 and 2000, primarily due to human activities [3,7,8,9].

Key threats to seagrass meadows include eutrophication, dredging, coastal development, climate change, and direct mechanical damage caused by anchoring and trawling [10]. The detection and quantification of such impacts are crucial for designing effective seagrass conservation and restoration strategies [11,12,13]. Over the past decades, awareness of the need to monitor the health status of seagrass beds has rapidly increased, and several monitoring programs have been established. The most commonly used indicators are seagrass cover and density, which are essential to assess abundance and detect temporal changes. However, traditional monitoring methods based on direct underwater observations are time-consuming, costly, and often limited by water turbidity, accessibility constraints, and safety issues in deep or hazardous zones [14]. Recent advances in remote sensing techniques and high-resolution satellite imagery have significantly contributed to seagrass monitoring and mapping, especially at a regional to global scale [15,16,17]. However, many monitoring programs require detailed, small-scale assessment of seagrass cover at resolutions that even the most advanced satellite platforms cannot consistently provide.

In this context, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, have gained increasing attention in marine ecology [18]. They offer a promising alternative by enabling high-resolution, repeatable, and non-invasive monitoring across spatial and temporal scales [19]. While satellite remote sensing, such as Landsat 8 OLI (spectral bands: 9 bands VIS, NIR and SWIR; spatial resolution 30 m), Landsat 8 TIRS (spectral bands: 2 thermal infrared bands; spatial resolution 100 m), ASTER (spectral bands: 14 bands VIS, NIR, SWIR and TIR; spatial resolution 15–90 m), or Sentinel-2 MSI (spectral bands: 13 bands VIS, NIR and SWIR; spatial resolution 10–60 m), has a relatively raw resolution of 10 to 100 m [20,21], image sensors on UAVs can capture higher resolution imagery (<0.1 m) [22]. Equipped with advanced imaging sensors, ranging from RGB to multispectral, hyperspectral, and LiDAR sensors, UAVs can capture detailed imagery that supports habitat mapping, change detection, and ecological assessments [23,24,25].

UAVs have been used to successfully map seagrass habitats in intertidal and shallow coastal waters at fine scales all around the globe [12,13,18,23,26,27,28,29,30], as well as for the identification of anthropogenic [31] and natural disturbances [12,13]. Training initiatives for UAV-based seagrass monitoring have also been developed [32]. UAV-based monitoring can complement traditional field surveys by providing high-resolution and repeatable data when conducted with standardized survey protocols and appropriate quality control measures. Nonetheless, the widespread adoption of these technologies remains limited by financial and accessibility constraints. These include not only the expenses of UAV hardware but also the high prices of commercial photogrammetry and image-processing software, which are often unaffordable for local conservation groups, NGOs, and research institutions with limited resources. This technological and economic divide restricts the implementation of drone-based monitoring approaches, particularly in regions where data on seagrass dynamics are most needed.

In addition to economic barriers, regulatory constraints represent a practical limitation for the deployment of UAVs in coastal and marine environments, particularly within protected areas. Aviation regulations often impose restrictions on flight operations, pilot certification, and aircraft weight, which can hinder the use of conventional UAV platforms. In the European context, lightweight drones with a takeoff mass below 250 g are subject to fewer operational constraints and can be more easily deployed for scientific monitoring, provided that safety and privacy requirements are met. These regulatory advantages make sub-250 g UAVs particularly suitable for localized monitoring activities in marine protected areas, where minimizing disturbance and ensuring compliance with legal frameworks are essential.

To address these combined technical, economic, and regulatory challenges and promote the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) science principles [33], this study presents a fully documented, low-cost workflow for seagrass monitoring using a lightweight, sub-250g drone (DJI Mini 4 Pro) and freely accessible mission-planning and photogrammetric tools. The aim is to test the feasibility and technical performance of this workflow in generating high-resolution spatial products suitable for ecological assessments of seagrass meadows while keeping operational and computational costs minimal. The central hypothesis is that affordable UAV-based monitoring can deliver accuracy levels adequate for local-scale habitat evaluation, enabling broader adoption of standardized monitoring practices and supporting community-driven and citizen science initiatives in coastal management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

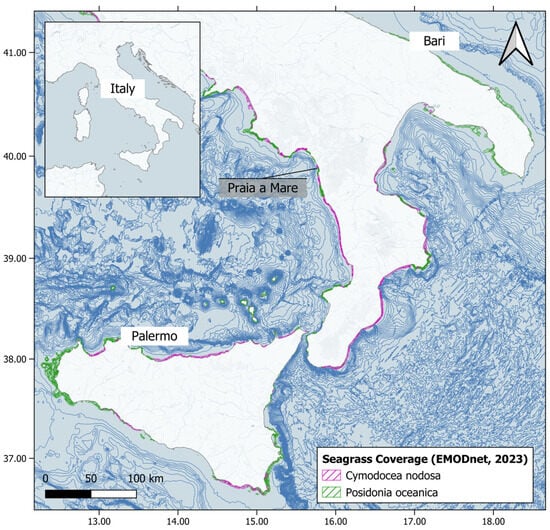

The field survey was conducted along the Tyrrhenian Calabrian coastline in southern Italy, where extensive seagrass meadows are known to occur. Along the Calabrian coast, Posidonia oceanica meadows are relatively continuous but are increasingly affected by human activities, particularly coastal development, anchoring, and unregulated boating, which can lead to fragmentation and meadow regression. The area chosen for the field survey, Praia a Mare (Cosenza, Italy), is characterized by shallow, clear waters, making it suitable for aerial surveys (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the field survey, Praia a Mare (Cosenza, Italy). Cymodocea nodosa and Posidonia oceanica coverage is reported in the map (source: EMODnet, 2023 [34]). Bathymetry data were obtained from the 1 min Gridded Global Relief Data ETOPO1 (2009, https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/global.html (accessed on 1 July 2025)). The map was generated using QGIS software (Version 3.44.0).

The surveyed area was intentionally limited in spatial extent and located along the coastline, where the presence of heterogeneous features such as shoreline morphology, seabed texture, and fixed reference elements supports reliable image matching and orthomosaic reconstruction. This design choice was adopted to mitigate known limitations of photogrammetric processing over homogeneous open-water surfaces.

2.2. UAV Platform and Sensor

A commercially available UAV quadcopter drone, DJI Mini 4 Pro (Shenzhen, China) was used. The DJI Mini 4 Pro is a compact, ultra-light drone with a takeoff weight of approximately 249 g, designed to comply with sub-250g European regulatory requirements (EU Regulation 2019/945 and EU Regulation 2019/947). It offers a maximum flight time of up to 34 min under ideal conditions. The drone features a three-axis mechanical gimbal that stabilizes a 1/1.3 inch CMOS camera with RGB sensor (spectral bands: RGB VIS; spatial resolution <1 cm) capable of capturing 4K/60fps HDR video and 48 MP still images, with ground control over tilt, pan, and roll via the DJI RC 2 controller. The gimbal offers stabilized nadir-view capture, enhancing image alignment for orthophoto reconstruction.

The Mini 4 Pro is equipped with DJI’s OcuSync 4.0 transmission system, offering a stable live video feed up to 20 km. It includes an onboard GNSS receiver supporting GPS, Galileo, and BeiDou satellite systems for precise positioning.

The aircraft includes an integrated Advanced Pilot Assistance System (APAS 5.0) and omnidirectional obstacle sensing for enhanced safety. Data such as altitude, velocity, distance from home, and satellite count are continuously relayed to the ground station via a DJI RC 2 controller.

2.3. Flight Planning

Flight planning is a crucial step in aerial monitoring, as it allows consistent and repeatable data acquisition over time and space. Small commercial UAVs, such as the DJI Mini 4 Pro, do not always include advanced waypoint planning features in their native apps. Therefore, to enable automated missions and improve data standardization, it is often necessary to integrate third-party mission planning tools.

To identify suitable software for sub-250g drones, an online search was conducted to systematically evaluate available flight planning software compatible with the DJI Mini 4 Pro and similar lightweight UAVs. The review included both desktop and mobile-based platforms and assessed key features such as waypoint automation, altitude and overlap settings, area mapping capability, and ease of integration with drone hardware and software. Tools were compared based on functionality, compatibility, and pricing.

Based on this analysis, the most cost-effective and functionally suitable software option was selected and tested during the field survey. All UAV flights were conducted following a standardized survey design, with pre-defined flight altitudes, image overlap, and ground control point placement, and orthomosaic reconstruction included quality control checks to ensure accurate, reproducible, and scientifically robust mapping of seagrass meadows.

Three automatic flights were planned at an altitude of 45 m to achieve a Ground Sample Distance (GSD) of less than 1.5 cm with a speed of 2.5 m/s and a 90° gimbal angle. Flight altitude was selected to balance spatial resolution, coverage area, and flight stability. The planned altitude is sufficient to resolve fine-scale seagrass features and meadow boundaries in shallow coastal waters. Lower altitudes would marginally improve spatial resolution but at the expense of increased flight time and reduced spatial coverage, while higher altitudes would reduce the ability to detect small-scale spatial heterogeneity. Images were acquired in nadir orientation to minimize geometric distortions and sun glint effects, thereby improving photogrammetric accuracy. To ensure sufficient overlap for image alignment, front and side overlaps of 70% and 80%, respectively, were applied, allowing reliable identification of common features across adjacent images [28]. Flight missions were conducted under low wind conditions to minimize platform instability and motion blur, which can adversely affect image sharpness and georeferencing accuracy. Weather conditions were dry with wind speeds averaging 4.5 ms−1, and the sky was clear and cloudless.

2.4. Ground Control Points and Ground-Truth Survey

During each flight, 10 ground control points (GCPs) were deployed along the shoreline using large, high-contrast markers easily identified in the drone images. The coordinate location of each GCP was recorded using a Garmin Etrex 22x (New Taipei City, Taiwan), providing sub-meter positional accuracy. GCP locations were chosen considering accessibility, even spacing across the survey area, and avoidance of locations subject to strong currents or wave action to minimize potential displacement. When possible, GCPs were anchored or placed in areas with minimal water motion during image acquisition.

A ground-truthing campaign was also carried out at the same time as the field survey. Shallow-water snorkeling was conducted, and the presence or absence of seagrass was recorded, and georeferenced photographs were taken using a GoPro Hero 12 camera (San Mateo, California, United States) to provide reference images.

2.5. Photogrammetric Processing and Orthophoto Reconstruction

To process the collected imagery, generate georeferenced orthomosaics, and support the interpretation of habitat features, an online review was conducted to identify both open-source and commercial photogrammetry software compatible with UAV-geotagged images. Each software was assessed based on cost, supported OS, system requirements, processing capabilities, and key features. Based on this review, the most cost-effective and functionally adequate software option was selected and tested for image alignment and orthomosaic construction.

Final orthomosaics were exported and manually interpreted using the free and open-source QGIS software (Version 3.44.0). Seagrass patches were digitized as vector layers based on visual inspection of color and shape in the aerial imagery, allowing spatial delineation of seagrass areas and comparison with ground-truth points. Manual visual interpretation was deliberately adopted to provide a conservative and transparent baseline assessment of seagrass detectability from low-cost UAV-derived orthomosaics. While supervised classification techniques can improve efficiency and scalability, they introduce additional sources of uncertainty related to training data selection, class definition, and algorithm performance, particularly in optically complex shallow coastal environments. Establishing a visually validated reference map, therefore, represents a necessary first step for evaluating and benchmarking automated or machine learning-based classification approaches in future applications.

3. Results

3.1. Flight Planning and Executing

The online search identified six mission planning software compatible with the DJI Mini 4 Pro and similar sub-250g UAVs (Table 1). It is important to note that the results of the software evaluation are valid only at the time of the online search (July 2025) and to the best of the authors’ knowledge. Software availability, pricing models, and drone compatibility may change over time. The tools were evaluated based on their compatibility with lightweight drones, availability of desktop mission planning, waypoint automation, altitude and overlap settings, automatic flight height adjustment, automatic mission installer, and finally, pricing structure. Among the reviewed tools, WaypointMap, Pixpro Waypoints, and Dronelink offered the most complete functionalities, with a range of prices going from free (basic version of WaypointMap) to ~€19 per month (starter version of Dronelink).

Table 1.

Comparison of mission planning software tools compatible with the DJI Mini 4 Pro and other sub-250g drones, including supported features, settings, and pricing. Note: Currency conversions to euros are approximate and may vary based on exchange rates (date of evaluation: July 2025); feature availability may vary between free and paid versions. ✓/- Included/Not included in the software version. * Only in the premium version.

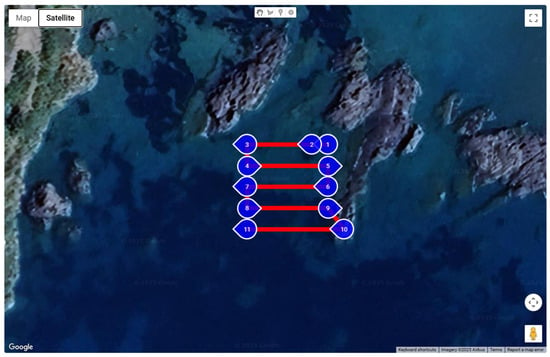

Following the comparative assessment and considering the associated costs, DJI Fly and WaypointMap (Basic version) (http://www.waypointmap.com (accessed on 1 July 2025) were selected. Unfortunately, DJI Fly does not allow for automatic mission planning but only for manual identification of waypoints. WaypointMap provides active support for the DJI Mini 4 Pro and includes essential features such as mission planning, altitude control, overlap settings, and flight path visualization. Although the premium version offers advanced features such as height auto-adjustment and automatic mission installer, the free version proved sufficient for the needs of this study, allowing the creation of pre-programmed flight paths with user-defined parameters. WaypointMap was ultimately used to plan the mission for automated flights to be carried out over the selected seagrass monitoring area at Praia a Mare (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flight planning using the WaypointMap software (Basic version) (http://www.waypointmap.com (accessed on 1 July 2025)) over the Praia a Mare study site (see Figure 1). The figure illustrates the pre-programmed flight path over (turned points in blue and path lines in red) the study site. The basic version of WaypointMap uses the Basemap provided by Google. Google Earth Mapping Service is a trademark of Google LLC.

The application provided stable and consistent mission execution, ensuring full coverage of the designated area. Mission repeatability was achieved across different days under comparable weather and light conditions, facilitating temporal comparability of orthophotos.

3.2. Photogrammetric Processing

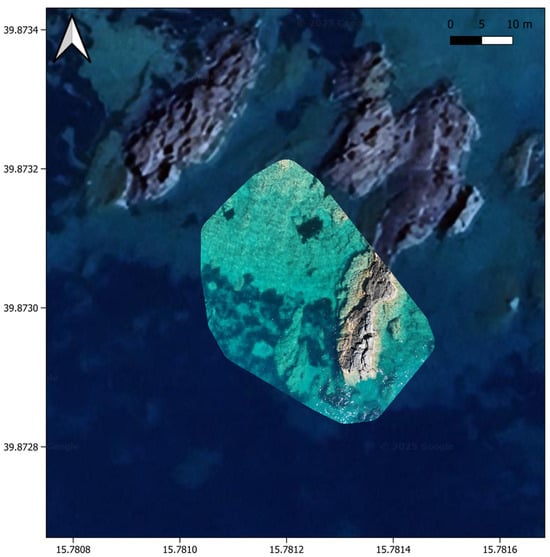

Photogrammetric software tools identified and reviewed included both open-source and commercial solutions (Table 2). It is important to note that the software selection and evaluation reflect the tools available and accessible at the time of the study (July 2025) and to the best of the authors’ knowledge. Among the eight software identified, all provide advanced features such as orthomosaic reconstruction and 3D model generation, with some of them able to process multispectral data. All the software, except DroneDeploy, requires a certain level of technical proficiency to operate. Taking into consideration the different features, the skills required, and the costs of the different software, WebODM (https://webodm.net/ (accessed on 1 July 2025)) was selected as the testing processing platform for this study due to its open-source nature, compatibility with geotagged drone imagery, and zero licensing cost (when self-hosted). Captured images were imported into WebODM and processed using the standard workflow with orthophoto reconstruction (no image resizes, fast orthophoto reconstruction). Processing was conducted on a mid-range laptop (Intel i5 processor, NVIDIA GeForce GT 710, 32 Gb RAM, 512 Gb SSD storage), with average processing times of approximately 1–2 h per flight, depending on the number of images. Orthomosaic reconstruction and image alignment included systematic quality control, including visual inspection of tie points, GCP checks, and coverage completeness, to ensure accurate and reproducible geospatial outputs. The resulting georeferenced orthomosaics were then exported as GeoTIFF for further analysis (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of photogrammetry software tools (accessed on 1 July 2025) compatible with DJI Mini 4 Pro and other sub-250g drones, including supported features and pricing. Note: Currency conversions are approximate and may vary based on exchange rates (date of evaluation: July 2025); feature availability may vary between free and paid versions; proficiency scale (1–5): 1 = very low (graphical interface, minimal configuration), 5 = advanced (command line usage, scripting).

Figure 3.

Example of an orthophoto mosaic generated using WebODM (self-hosted) of a seagrass meadow in the Praia a Mare study site (see Figure 1), exported as a GeoTIFF and imported into QGIS. The Basemap is provided by Google. Google Earth Mapping Service is a trademark of Google LLC. The map was generated using QGIS software (Version 3.44.0).

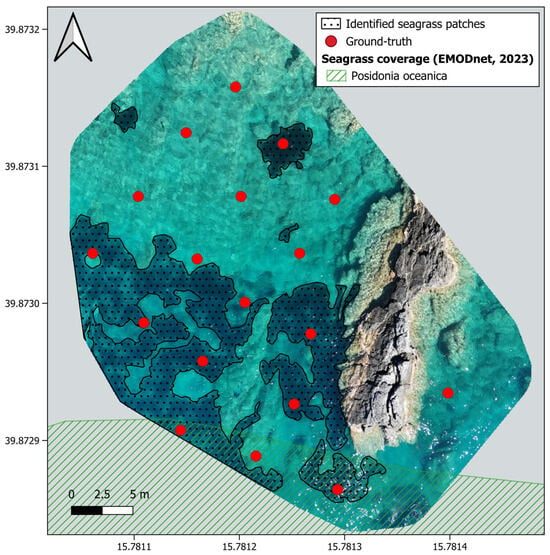

3.3. Seagrass Patches Identification and Analysis

Processed orthophotos were imported into QGIS software (Version 3.44.0) for manual interpretation. Seagrass meadows were manually digitized as vector layers based on visible texture, color, and canopy continuity, allowing the measurement of their position and size (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Manually digitized seagrass patches (dotted polygons) and corresponding ground-truth validation points (red dots) over the orthophoto mosaic generated using WebODM (self-hosted) of a seagrass meadow in the Praia a Mare study site (see Figure 1). The last report of Posidonia oceanica in the area is reported on the map (source: EMODnet, 2023 [34]). The map was generated using QGIS 3.44.0.

4. Discussion

This study reinforces the utility of UAVs as a fast, accurate, and scalable tool for seagrass habitat monitoring. Compared to traditional snorkel or diver-based surveys, drone-based monitoring provided broader spatial coverage in a fraction of the time with minimal ecological footprint. The ability to detect fine-scale meadows and eventually localize disturbances, such as anchor scars, is difficult to achieve with satellite or aerial imaging from higher altitudes. Satellite remote sensing approaches remain essential for regional- to basin-scale seagrass monitoring; however, their spatial resolution and sensitivity to environmental complexity can limit their effectiveness for detailed site-scale assessments. In this context, UAV-based monitoring is best suited to complement satellite observations by supporting high-resolution mapping in spatially constrained or protected coastal areas.

Low-cost UAV monitoring protocols, such as the workflow tested in this study using open-source or free/freemium software, may represent a democratization of ecosystem monitoring, particularly useful for NGOs, local managers, and citizen science initiatives. Our results align with recent findings [23,35], which demonstrated that UAVs equipped with RGB and multispectral sensors provided robust mapping of benthic habitats, offering a viable alternative to expensive boat-based and satellite-derived monitoring approaches. Even without multispectral sensors, standard RGB imagery proved sufficient for effective seagrass mapping under favorable water conditions [36]. However, detection accuracy may vary with water turbidity, sun glint, and deeper habitats beyond ~3 m. Additionally, while manual image classification remains labor-intensive, the combination of RGB drone images with open-source GIS tools demonstrated strong potential for low-cost monitoring workflows.

4.1. Integrated Workflow for Reproducible Seagrass Mapping

This study tested an end-to-end workflow that integrates mission planning, aerial data acquisition, photogrammetric processing, and habitat identification using freely available software tools. The workflow is designed to be fully reproducible and deployable with minimal computational resources, enabling broader adoption by small research groups, local agencies, and NGOs.

Mission Planning and Aerial Data Acquisition

The comparative analysis of flight planning tools revealed that while multiple commercial and subscription-based platforms support lightweight UAVs, only a few offer advanced waypoint automation compatible with the DJI Mini 4 Pro (and other small drones). Among these options, the basic version of WaypointMap was selected due to its full functionality for altitude setting, front/side image overlap configuration, and detailed waypoint creation, all at zero cost.

To ensure reproducibility, the mission planning workflow involved the following steps:

- Defining a polygon representing the extent of the target seagrass meadow, including the planned position of the GCPs.

- Setting flight altitude to 45 m above ground level to balance resolution with flight time, speed to 2.5 m/s, and gimbal angle to −90°.

- Generate mission flight.

- Exporting the waypoint file and uploading it to the UAV controller.

Field deployment confirmed the reliability of the software for repeatable, autonomous flights over the study site. Despite lacking advanced features such as automatic terrain following, the software allowed precise planning and coverage of the seagrass meadow with consistent image acquisition. The successful use of WaypointMap demonstrates that free mission-planning tools can offer viable alternatives to costly commercial platforms, especially when paired with drones under 250 g that lack native planning flexibility.

Photogrammetric Processing, GCPs Integration, and Seagrass Identification

The results of the photogrammetry software evaluation confirmed that WebODM, an open-source and self-hosted processing suite, was fully capable of generating orthophotos from RGB imagery captured during survey missions. GCPs deployed across the study area support accurate georeferencing during orthomosaic reconstruction.

For reproducibility, the processing workflow followed these steps:

- Uploading the image dataset (JPEG format) into a new WebODM project.

- Applying the default “High Resolution” processing preset.

- Activating the “Fast Orthophoto” option to optimize mosaic blending.

- Running the reconstruction using CPU-only computation on a mid-range laptop.

- Exporting the final orthomosaic as a GeoTIFF file for use in GIS.

High front and side image overlap ensured sufficient redundancy for robust image alignment and stitching, even in areas characterized by limited textural contrast. Manual inspection of the orthomosaics was conducted to verify alignment accuracy and identify potential artifacts.

The performance of WebODM on moderate hardware confirmed that high-end computational resources are not required for small-area coastal monitoring. Although WebODM lacks some advanced automation, such as cloud-based collaboration features found in commercial platforms such as Pix4Dmapper or DroneDeploy, its zero cost and functionality make it particularly well-suited for small organizations and NGOs. The outputs, high-resolution orthophotos suitable for vectorization (GeoTIFF format), enabled clear identification of seagrass patches in QGIS. Manual digitization of polygons was performed at sub-meter scales, enabling accurate habitat mapping.

Artifacts caused by water glare or cloud shadows were minimal and did not impede manual interpretation. Overall, the use of free, self-hosted software, when paired with low-cost UAVs, provides a fully reproducible, accessible, and scalable strategy for coastal habitat monitoring.

4.2. Limitations and Considerations

While the proposed workflow demonstrated success in seagrass monitoring, several limitations should be acknowledged:

- -

- Dynamic software landscape: The tools assessed in this study were evaluated based on availability and functionality as of July 2025. Software availability, feature sets, pricing models, and drone compatibility may change at any time. Therefore, replicability of this exact workflow in the future may require adjustments and updated tool reviews.

- -

- Open-source installation: Software like WebODM, while cost-free and highly customizable, often needs manual installation and configuration, requiring a certain level of technical proficiency to operate. This can be a barrier for users without technical expertise.

- -

- Hardware limitations: The study employed a sub-250g UAV (DJI Mini 4 Pro), which, while beneficial from a cost perspective, is more sensitive to environmental conditions such as wind gusts, precipitation, and low-light scenarios. Small drones are less stable in strong winds and may be unable to complete planned missions in adverse weather, potentially affecting data consistency and operational feasibility.

- -

- Sensor limitations: The study was conducted using a standard RGB camera, providing information limited to the visible spectrum, which, although adequate under optimal water clarity, does not explicitly discriminate based on narrow spectral bands that could be used for detailed seagrass health assessments. Compared to commonly used satellite sensors for seagrass monitoring (e.g., Sentinel-2 or Landsat 8 OLI), which include multiple visible and near-infrared bands, UAV RGB sensors offer reduced spectral sensitivity but substantially finer spatial resolution.

- -

- Environmental variability: Water clarity, sunlight angle, and sea surface reflection all can affect image quality. While low-cost UAV platforms may exhibit greater sensitivity to environmental conditions compared to professional systems, careful flight planning, high image redundancy, and GCP deployment can substantially mitigate associated uncertainties, although such control is not always feasible in long-term monitoring efforts.

- -

- Manual image interpretation: Visual digitization of seagrass patches can introduce subjectivity and inconsistencies. Automation using AI or supervised classification was beyond the scope of this study but should be pursued in future work to improve efficiency and repeatability.

- -

- Regulatory constraints: UAV operations are subject to national and regional regulations, which vary across countries and protected areas. Even sub-250g platforms may face restrictions, which can limit the broader implementation and adoption of the workflow despite its technical feasibility and cost-effectiveness.

Despite these constraints, this study demonstrates that low-cost UAVs and open-source software can be successfully used for coastal habitat monitoring. The standardized flight design, GCP deployment strategy, and orthomosaic quality control process adopted in this study were selected to ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility.

The study area was intentionally limited in size and characterized by sufficient spatial heterogeneity to support reliable image matching. In environments with reduced spatial heterogeneity, alternative strategies, such as additional artificial targets or mixed land–water flight designs, may be required. Overall, the proposed workflow demonstrates how scientifically robust seagrass mapping can be achieved at local scales, highlighting the trade-offs between accessibility and data accuracy, while providing a scalable and replicable model for institutions and organizations with limited financial and technical resources, contributing meaningfully to the democratization of marine ecosystem monitoring.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that commercial drones offer a practical and effective approach for monitoring seagrass meadows in shallow coastal environments. Their ability to capture high-resolution imagery of both intact and disturbed habitats makes them an ideal complement to traditional monitoring methods. By integrating drones into routine conservation workflows, coastal managers can improve impact detection, enhance temporal monitoring, and better inform policy decisions. Future work should explore the combination of RGB drones with free and open-source AI-driven classification to improve habitat discrimination under diverse environmental conditions.

By demonstrating a cost-effective and operationally simple workflow in a Mediterranean setting, this work supports the broader integration of UAVs into routine conservation practices, especially in contexts with limited resources.

Author Contributions

V.C.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, and funding acquisition. T.R.: supervision and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the British Ecological Society’s “Small Research Grant”, Grant number: SR23\1434.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Unsworth, R.K.F.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.C. Seagrass Meadows. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R443–R445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemminga, M.A.; Duarte, C.M. Seagrass Ecology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Waycott, M.; Duarte, C.M.; Carruthers, T.J.B.; Orth, R.J.; Dennison, W.C.; Olyarnik, S.; Calladine, A.; Fourqurean, J.W.; Heck, K.L.; Hughes, A.R.; et al. Accelerating Loss of Seagrasses across the Globe Threatens Coastal Ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 12377–12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, J. Biodiversity and the Functioning of Seagrass Ecosystems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 311, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, R.K.F.; Nordlund, L.M.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.C. Seagrass Meadows Support Global Fisheries Production. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 12, e12566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potouroglou, M.; Bull, J.C.; Krauss, K.W.; Kennedy, H.A.; Fusi, M.; Daffonchio, D.; Mangora, M.M.; Githaiga, M.N.; Diele, K.; Huxham, M. Measuring the Role of Seagrasses in Regulating Sediment Surface Elevation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Enironment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC); Short, F.T. Global Distribution of Seagrasses; Version 6.0; Sixth Update to the Data Layer Used in Green Short; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, R.J.; Carruthers, T.J.B.; Dennison, W.C.; Duarte, C.M.; Fourqurean, J.W.; Heck, K.L.; Hughes, A.R.; Kendrick, G.A.; Kenworthy, W.J.; Olyarnik, S.; et al. A Global Crisis for Seagrass Ecosystems. BioScience 2006, 56, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Short, F.T.; Polidoro, B.; Livingstone, S.R.; Carpenter, K.E.; Bandeira, S.; Bujang, J.S.; Calumpong, H.P.; Carruthers, T.J.B.; Coles, R.G.; Dennison, W.C.; et al. Extinction Risk Assessment of the World’s Seagrass Species. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 1961–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, S.C.; Raskin, K.N.; Hazell, J.E.; Morera, M.C.; Monaghan, P.F. Evaluation of Interventions Focused on Reducing Propeller Scarring by Recreational Boaters in Florida, USA. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 186, 105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Davies, K.P.; Barber, P.; Bruce, E. Mapping Fine-Scale Seagrass Disturbance Using Bi-Temporal UAV-Acquired Images and Multivariate Alteration Detection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, L.R.; Yang, B.; Graham, O.J.; Gomes, C.; Rappazzo, B.; Hawthorne, T.L.; Duffy, J.E.; Harvell, D. UAV High-Resolution Imaging and Disease Surveys Combine to Quantify Climate-Related Decline in Seagrass Meadows. Oceanography 2023, 36, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, F.T.; Coles, R.G.; Short, C.A. Global Seagrass Research Methods; Elsevier Science B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Topouzelis, K.; Makri, D.; Stoupas, N.; Papakonstantinou, A.; Katsanevakis, S. Seagrass Mapping in Greek Territorial Waters Using Landsat-8 Satellite Images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 67, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelfsema, C.; Kovacs, E.M.; Saunders, M.I.; Phinn, S.; Lyons, M.; Maxwell, P. Challenges of Remote Sensing for Quantifying Changes in Large Complex Seagrass Environments. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 133, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traganos, D.; Aggarwal, B.; Poursanidis, D.; Topouzelis, K.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Reinartz, P. Towards Global-Scale Seagrass Mapping and Monitoring Using Sentinel-2 on Google Earth Engine: The Case Study of the Aegean and Ionian Seas. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Gaston, K.J. Lightweight Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Will Revolutionize Spatial Ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, P.; Silva, M.; Quelhas, M.; Adão, H. Precision Mapping of Seagrass Habitats Using Multispectral Drones and Machine Learning. Preprints 2024, 2024110297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and Photographic Infrared Linear Combinations for Monitoring Vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.T.; Ostrovsky, M. From Space to Species: Ecological Applications for Remote Sensing. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomina, I.; Molina, P. Unmanned Aerial Systems for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing: A Review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 92, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elma, E.; Gaulton, R.; Chudley, T.R.; Scott, C.L.; East, H.K.; Westoby, H.; Fitzsimmons, C. Evaluating UAV-Based Multispectral Imagery for Mapping an Intertidal Seagrass Environment. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2024, 34, e4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oiry, S.; Davies, B.F.R.; Sousa, A.I.; Rosa, P.; Zoffoli, M.L.; Brunier, G.; Gernez, P.; Barillé, L. Discriminating Seagrasses from Green Macroalgae in European Intertidal Areas Using High-Resolution Multispectral Drone Imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, A.; Tovar-Sánchez, A.; Olivé, I.; Navarro, G. Using a UAV-Mounted Multispectral Camera for the Monitoring of Marine Macrophytes. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 722698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riniatsih, I.; Ambariyanto, A.; Yudiati, E.; Redjeki, S.; Hartati, R. Monitoring the Seagrass Ecosystem Using the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) in Coastal Water of Jepara. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 674, 012075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gundersen, H.; Poulsen, R.N.; Xie, L.; Ge, Z.; Hancke, K. Quantifying Seaweed and Seagrass Beach Deposits Using High-Resolution UAV Imagery. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 331, 117171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, J.P.; Pratt, L.; Anderson, K.; Land, P.E.; Shutler, J.D. Spatial Assessment of Intertidal Seagrass Meadows Using Optical Imaging Systems and a Lightweight Drone. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 200, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, S.; Sudo, K.; Yamakita, T.; Nakaoka, M. Species Level Mapping of a Seagrass Bed Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Deep Learning Technique. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.; Collin, A.; Houet, T.; Mury, A.; Gloria, H.; Poulain, N.L. Towards Better Mapping of Seagrass Meadows Using UAV Multispectral and Topographic Data. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 95, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karang, I.W.G.A.; Pravitha, N.L.P.R.; Nuarsa, I.W.; Basheer Ahammed, K.K.; Wicaksono, P. High-Resolution Seagrass Species Mapping and Propeller Scars Detection in Tanjung Benoa, Bali through UAV Imagery. J. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 25, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Hawthorne, T.L.; Hessing-Lewis, M.; Duffy, E.J.; Reshitnyk, L.Y.; Feinman, M.; Searson, H. Developing an Introductory UAV/Drone Mapping Training Program for Seagrass Monitoring and Research. Drones 2020, 4, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMODnet Seabed Habitats Product. Contains Data from the Global Distribution of Seagrasses (v7.1 March 2021). UNEP-WCMC, Short FT (2021). Global Distribution of Seagrasses (Version 7.1). Seventh Update to the Data Layer Used in Green and Short (2003); UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.; Papagiannopoulos, N.; Clewley, D.; Groom, S.; Raitsos, D.E.; Hoteit, I. Mapping Coastal Marine Habitats Using UAV and Multispectral Satellite Imagery in the NEOM Region, Northern Red Sea. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, J.; Wallin, D.; Yang, S.; Rybczyk, J. Using Drone-Captured Imagery and a Digital Elevation Model to Differentiate Eelgrass Species: Padilla Bay, Washington. J. Coast. Res. 2024, 41, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.