Abstract

(1) Background: Indwelling pleural catheters (IPCs) with vacuum-based drainage can cause pain, especially in patients with a non-expandable lung (NEL). This evaluation assessed whether the Passio™ digital drainage system offers a viable alternative for patients experiencing pain during IPC drainage. (2) Methods: All IPC patients between November 2023 and April 2024 completed questionnaires assessing pain severity on a 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS) at four points during drainage. Patients reporting drainage-related pain at the 2-week post-IPC appointment had their existing valve replaced with a Passio™ valve (n = 5). (3) Results: Twenty-seven patients (59% male) were included in this analysis. The mean VAS scores for pain with a standard vacuum bottle were not statistically different at mid-drainage and the end of drainage compared with pre-drainage. Patients who experienced pain with the vacuum bottle (n = 5) had higher mean VAS scores at mid-drainage (51.68 mm ± 16.29; p = 0.13), end of drainage (46.68 mm ± 19.45; p = 0.19), and 10 min post-drainage (61.38 mm ± 9.81; p = 0.06) compared with pre-drainage (9.16 mm ± 4.01). Post-Passio™ valve replacement (n = 5), patients had a lower VAS pain score mid-drainage (20.15 mm ± 9.34; p = 0.25), end of drainage (27.28 mm ± 12.69; p = 0.84), and 10 min post-drainage (14.81 mm ± 3.33; p = 0.0079) when compared with vacuum bottle drainage. There were no complications with the Passio™ drainage system. (4) Conclusions: Controlled pleural drainage using a digital drainage device such as Passio™ may have a role in IPC patients who experience pain with vacuum bottle drainage, especially in those with an NEL.

1. Introduction

Pleural effusions are common, with approximately 1 to 1.5 million new cases diagnosed annually in the United States and 200,000 to 250,000 in the United Kingdom [1]. A total of 15% of all cancer patients will have a malignant pleural effusion (MPE), and the incidence and prevalence are increasing [2,3,4,5]. Talc slurry pleurodesis (via chest drain) or talc poudrage (during thoracoscopy) has been the preferred treatment for recurrent MPEs for many decades; however, to achieve successful pleurodesis, the visceral and parietal pleural surfaces should be “apposed”, and there should not be any evidence of a non-expandable lung (NEL). Approximately 30% of patients with symptomatic MPEs present with an NEL, where the lung is unable to expand more than 75% of the chest cavity after drainage of pleural fluid [6]. American Thoracic Society guidelines advocate for the use of indwelling pleural catheters (IPCs) in the context of an NEL as opposed to talc pleurodesis, given the rare clinical effectiveness [7].

IPCs represent a significant advancement in the management of recurrent pleural effusions, offering an alternative to repeated thoracentesis or talc pleurodesis. Historically, IPCs were primarily used in patients with MPEs considered unsuitable for talc pleurodesis, MPEs with failed talc pleurodesis, or in the context of an NEL [8,9]. The TIME-2 study, which was a landmark randomised controlled trial (RCT), showed that in patients with malignant pleural effusions (MPEs), there was no difference in dyspnoea between IPCs and talc pleurodesis [10]. The Australasian MPE Trial (AMPLE-1) showed that patients who had an IPC inserted required significantly fewer days in hospital compared with patients who had talc pleurodesis [3]. With new emerging data on the safety and efficacy of IPCs, recently updated British Thoracic Society pleural disease guidelines advocate using IPCs as a first-line treatment option in patients with MPEs without known NEL [6].

The increasing use of IPCs has revolutionised the treatment of recurrent symptomatic pleural effusions [11]. In the context of MPEs, the ASAP trial and the AMPLE-2 trial showed that aggressive daily drainage with an IPC promotes spontaneous autopleurodesis, much quicker than symptom-based drainage [12,13]. IPCs can also be utilised in benign effusions if the pleural effusions are recurrent despite optimum medical management. Pleural effusions that are refractory to treatment may arise from benign conditions such as cardiac failure, hepatic hydrothorax, chylothorax, yellow nail syndrome, empyema, and inflammatory pleuritis [14,15].

IPCs are tunnelled silicone chest tubes inserted under local anaesthesia as a day-case procedure. These tubes enable frequent, tailored fluid drainage through a detachable vacuum bottle, which applies variable vacuum pressures modulated by a roller valve or a push button. Fluid can be drained in a few minutes and performed at home by district nurses, relatives, or patients. Titrating the vacuum pressure and fluid removal rate can be challenging and is not a straightforward process.

While IPCs provide effective palliation of shortness of breath and improve quality of life, repeated fluid drainages can be painful, impacting patient comfort and adherence to therapy [16]. Awareness of the mechanisms, risk factors and management strategies for pain during IPC drainage is important for optimising patient outcomes [16]. Pain during IPC drainage can be due to several factors, including changes in pressure within the pleural space, patient-related factors such as chronic pain, anxiety, and heightened pain sensitivity. Pain experienced during IPC drainage should be distinguished from tumour-related chest wall pain [17].

Pain can be alleviated by administering analgesia pre-drainage, slowing down the rate, stopping the drainage (at a volume slightly lower than that known to cause pain previously) [18] or attaching the drain to an underwater seal bottle, thereby eliminating the vacuum. Severe intractable pain during drainage requiring IPC removal is rare, occurring only in 0.6% of cases [19].

We conducted a real-world prospective analysis to evaluate the pain outcomes of patients undergoing IPC drainage with vacuum bottles and to determine whether the Passio™ digital drainage system could be a viable alternative for patients who experience pain during drainage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. What Is the Passio™ Digital Drainage System?

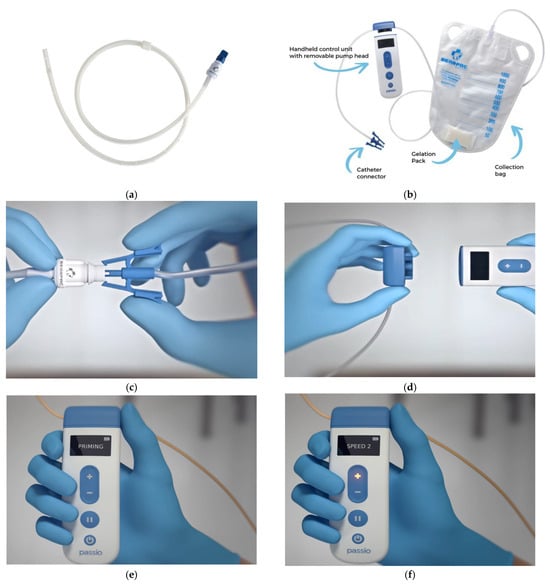

The Passio™ drainage system is a digitally controlled low-level suction system with a handheld control unit to regulate the speed at which an IPC can be drained. This is manufactured by Bearpac Medical (Moultonborough, NH, USA). This drainage system consists of a Passio™ catheter, a battery-controlled handheld control unit, and a fluid collection bag with a pump head (Figure 1). The drainage system can be used with any other IPC catheter by replacing the native IPC valve with a Passio™ valve, which would attach to the catheter connector in the drainage system. The battery-controlled handheld unit has 4 speeds corresponding to various flow rates and can be appropriately selected by the patient as per their comfort levels (Table 1). The handheld unit has a battery-operated motor that drives a cogwheel mechanism when attached to the removable pump head, which regulates the flow rate.

Figure 1.

(a) Passio™ IPC Catheter, (b) Passio™ Digital Drainage System, (c) how to attach the catheter connector to the valve, (d) attaching the removable pump head to the handheld control unit, (e) “Priming” phase of the handheld control unit, and (f) selection of speeds 1–4 using the +/− buttons on the handheld control unit (images obtained from Bearpac Medical with permission).

Table 1.

Flow rates (mL/min) that correspond to different speeds in the handheld unit.

This analysis investigated the pain levels patients experience during IPC drainage using a standard vacuum bottle. We also evaluated whether the Passio™ digital drainage system could effectively reduce chest pain during IPC fluid drainage and would be a viable alternative instead of the standard vacuum bottle.

2.2. Analysis Design

This analysis was conducted as a service evaluation project to improve the quality of care within our tertiary care centre, which is a part of a university hospital. Our analysis was registered as a quality improvement project with the local clinical audit team in the hospital (Audit No. 12067). In accordance with local research governance policy, formal ethical approval was not required. This was a single-centre, prospective, feasibility analysis with 2 interventional arms. All components of this analysis were conducted at our tertiary care centre for respiratory diseases. All patients with an IPC inserted between November 2023 and April 2024 were included in this analysis. The local distributor provided 10 Passio™ IPC starter kits but was not involved with the evaluation.

2.3. IPC Insertion, Follow-Up, and Switching over to Passio™

Our pleural service used the 16-French size IPC catheter by Rocket Medical (Washington, UK). Pre-identified patients indicated to have an IPC undergo IPC insertion as a day-case procedure under local anaesthesia. Procedures were performed by adequately competent doctors or pleural nurse specialists (PNSs) in the day-case procedure room. As standard practice, post-procedure, patients and relatives were given verbal and written information regarding the IPC and the contact details of the PNS team to contact if necessary. District nurses were appropriately referred to perform IPC drainage at home using a standard vacuum drainage bottle, as required. The patient’s general practitioner would receive a letter detailing the procedure and instructions for ordering the necessary vacuum drainage bottle supplies through the patient’s repeat prescription.

As standard practice, all patients were given a questionnaire to complete at each drainage session at home regarding any pain they experienced (Appendix A). Pain severity was assessed using a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) at five points during drainage (before drainage, mid-drainage, end of drainage, 10 min after end of drainage, and 1 h after end of drainage).

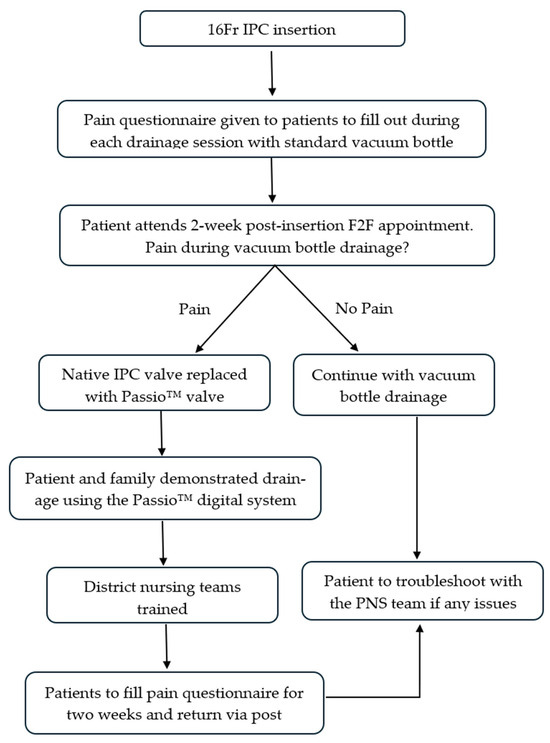

As standard practice, patients were reviewed face-to-face (F2F) 2 weeks post-IPC insertion by the PNS team to remove sutures placed during insertion and troubleshoot any issues patients might have. The pain questionnaires were reviewed at this appointment. If the patients complained of significant pain during drainage with a standard vacuum bottle, the native IPC valve was replaced with a Passio™ valve, and patients were shown how to perform a drainage with the Passio™ digital drainage system. Relevant district nursing teams were trained to operate the new digital drainage system facilitated by the local distributor. Patients were able to increase or decrease the speeds as per their comfort levels using the handheld unit (Table 1). A similar pain score questionnaire was given to patients to complete during each drainage session over the next two weeks with the new digital drainage system and was returned via post (Appendix B). Post-Passio™ pain scores were analysed and compared with baseline pain scores. Figure 2 summarises the evaluation protocol.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram highlighting the evaluation protocol. F2F—face-to-face; PNS—pleural nurse specialist.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was pain severity, assessed using a 100 mm visual analogue scale at four points during drainage (before drainage, mid-drainage, end of drainage, 10 min after end of drainage, and 1 h after end of drainage) with vacuum drainage +/− Passio™ digital drainage. Data were collected prospectively.

Secondary outcomes were analgesia use, coughing during drainage, and whether slowing down drainage improved pain and coughing. For patients who used the Passio™ digital drainage system, data were collected on any form of complications, pump/valve failures, and admissions directly linked to Passio™ malfunction.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism version 9.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard error of the means, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between unpaired non-parametric data were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test, while paired non-parametric data comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Characteristics

During the evaluation period (between November 2023 and April 2024), a total of 27 patients (n = 27) opted to have an IPC as first line. Baseline demographics (Table 2) showed that there was a male preponderance (male = 16 (59%)) with a mean age of 70 years. Most of the patients had a diagnosis of lung cancer (n = 8) or mesothelioma (n = 6). Approximately a third of the cohort had evidence of an NEL (n = 10 (37%)), determined using post-IPC drainage chest radiograph. A total of 70% of patients (n = 19) had >75% pleural apposition.

Table 2.

Baseline demographics.

3.2. Vacuum Bottle Drainage

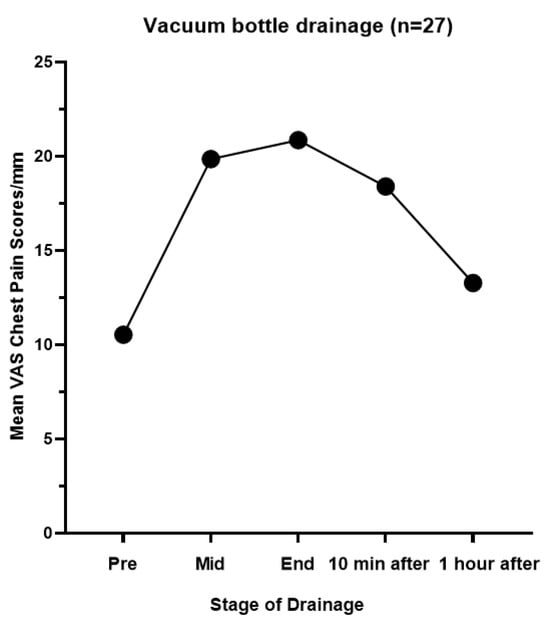

All patients (n = 27) had drainage with a standard vacuum bottle for the first 2 weeks after IPC insertion, followed by a routine F2F clinical review by the PNS. Patients reported a mean baseline chest pain VAS of 10.53 mm ± 2.73. Pain levels increased during drainage, with mean scores of 19.86 mm ± 5.15 at mid-drainage and 20.86 mm ± 5.87 at the end of drainage (p = 0.29 for both). Ten minutes after drainage, pain decreased to a mean of 18.40 mm ± 4.82 (p = 0.32), and 1 h after drainage, pain decreased to a mean of 13.28 mm ± 3.97 (p = 0.77) (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Chest pain mean VAS scores (mm) in all patients with vacuum bottle drainage.

Figure 3.

Chest pain mean VAS scores (mm) in all patients with vacuum bottle drainage.

A total of 59% (n = 16) of patients used analgesia, and 41% (n = 11) of patients experienced coughing during drainage. Among those who attempted to slow down the drainage process (n = 11), a large majority, 82% (9 out of 11), found it improved their pain and coughing symptoms, while 18% (2 patients) did not experience any benefit.

3.3. Passio™ Digital Drainage

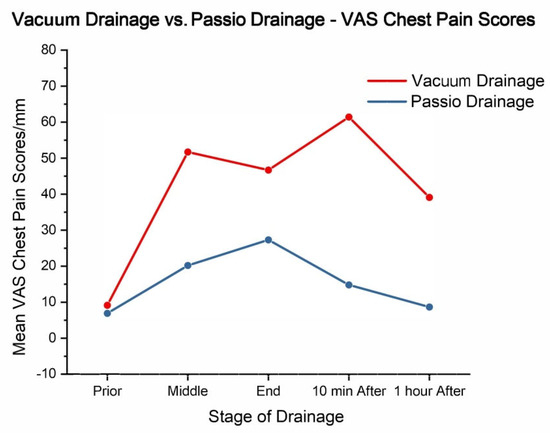

Five patients who experienced unbearable pain during drainage with a standard vacuum bottle had their native IPC valve replaced with a Passio™ valve and continued drainage with the Passio™ digital drainage system. All five patients had evidence of an NEL. Three patients had pleural effusions secondary to lung cancer, and two were secondary to breast cancer. When these patients were switched to the Passio™ digital drainage system, chest pain scores generally decreased compared with the standard vacuum drainage method (Table 4 and Figure 4). The mean VAS scores before drainage were similar (6.91 mm ± 2.45 vs. 9.16 mm ± 4.01; p = 0.79; Passio™ vs. vacuum). The Passio™ digital drainage system showed lower scores at mid-drainage (20.15 mm ± 9.34 vs. 51.68 mm ± 16.29 (p = 0.25); Passio™ vs. vacuum) and end-of-drainage (27.28 mm ± 12.69 vs. 46.68 mm ± 19.45 (p = 0.84); Passio™ vs. vacuum). The most pronounced difference was observed 10 min post-drainage, with Passio™ drainage reporting a significantly lower mean VAS score of 14.81 mm ± 3.33 compared with 61.38 mm ± 9.81 with vacuum drainage (p = 0.0079). Only one patient complained of coughing during drainage. These findings suggest a potential benefit of the Passio™ digital drainage system in alleviating drainage-related pain, particularly in patients with an NEL.

Table 4.

Chest pain mean VAS scores (mm) in patients who complained of pain with vacuum bottle drainage and switched on to the Passio™ digital drainage system (n = 5).

Figure 4.

Vacuum drainage vs. Passio™ drainage: VAS chest pain scores (mm).

3.4. Complications

The use of the Passio™ digital drainage system was associated with no complications. No pump or valve failures were reported. Furthermore, no hospital admissions were linked to complications arising from the Passio™ system. Notably, the patient satisfaction rate was 100%, and patients would recommend others to use the Passio™ digital drainage system if the standard vacuum drainage bottle causes pain.

4. Discussion

This analysis at our tertiary care centre has shown the potential of the Passio™ digital drainage system in improving patient comfort during IPC drainage. When VAS chest pain scores were compared with standard vacuum drainage, patients reported decreased pain with the Passio™ system. Notably, the Passio™ digital drainage system showed lower scores at mid-drainage and end-of-drainage, but the most significant difference was observed 10 min post-drainage, where the Passio™ drainage group reported a significantly lower mean VAS score compared with the vacuum drainage group. These findings suggest that the Passio™ digital drainage system may be particularly effective in alleviating drainage-related pain, especially in patients with an NEL. Furthermore, the absence of complications or pump or valve failures in this cohort of patients highlights the safety and reliability of the Passio™ system. The AMPLE-2 study compared the differences in breathlessness in aggressive daily drainage of IPCs vs. symptom-guided drainage and found no difference between the two groups, further suggesting the concept that Passio™ patient-controlled digital drainage would not result in worsening breathlessness [12].

The rapid drainage of pleural fluid via an IPC can create significant negative pressure within the pleural space, which has the potential to exert traction on the pleural surfaces and intercostal structures, potentially leading to pain. The standard vacuum drainage bottle can generate a starting pressure of −950 cm H2O at the onset of drainage [20]. This rapid increase in negative pressure on the pleura can cause considerable discomfort and irritation to the pleural surfaces, resulting in patients experiencing sharp chest pain.

MPEs in the presence of trapped lung remain notoriously difficult to treat. This pain may be more intense in the context of an NEL [9]. Approximately 5% of patients report pain during IPC drainage, likely due to disease in the visceral pleura impeding lung re-expansion. A recent multi-centre survey study in Canada found that 36% of patients experienced discomfort with home drainage, typically towards the end, when most of the fluid had been removed; this was more common among patients with an NEL [18]. Interestingly, our analysis showed that all patients who used the Passio™ digital drainage system exhibited evidence of an NEL, and 80% (4/5 patients) had evidence of <25% pleural apposition.

To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no peer-reviewed literature exploring the outcomes and efficacy of the Passio™ digital drainage system. The only available literature was conveyed through a conference abstract authored by Thakkar et al., where they presented their respective findings on the facilitation of pleural manometry during controlled drainage with the Passio™ digital drainage system, followed by a comparison of the pressure in the pleural space with the volume of pleural fluid drained [20]. The highest negative pressure noted was during the “priming” phase of the system, on average, −82.5 cmH2O (−69 to −117 cmH2O). The average pressure at the end of drainage was −45.5 cmH2O (−20 to −69 cmH2O). The authors reported that the patients had a degree of chest discomfort but improved much quicker than with the standard vacuum bottle drainage.

Moreover, another digital drainage system, Geyser (Tintron laboratories), has been evaluated by Welch et al. and showed promising signals of causing significantly less pain during IPC drainage [21]. The post-drainage visual analogue pain scores in the Geyser group were 9.1 mm (10.2) and 21.9 mm (22.8) in the standard group (95% CI: 1.7–24.0; p = 0.027).

Digital chest drainage systems have also been used in the field of cardiac surgery with improved pressure control, compared with traditional wall-suction systems. These digital systems are as reliable as conventional systems with no safety concerns, serving as a proof of concept for their effectiveness [22].

Whilst a digital drainage system may not be necessary for every patient with an IPC, it may be useful in a subset of patients who have intolerable pain or heightened pain-sensitivity on drainage and those who have an NEL and experience persistent pain. As clinicians, we should realise that “one size may not fit all” and it is always beneficial to have different options in the armoury to deliver patient-centred individualistic care.

While this analysis at our tertiary care centre shows that the Passio™ digital drainage system may improve patient comfort, several limitations should be considered. We acknowledge that a limited number of participants recruited from a single centre potentially impacts the generalisability of these results to the wider population. Additionally, the aforementioned limitation likely contributes to a type II error in our evaluation findings. We also recognise that studies such as these run the risk of having unintentional pro-intervention bias. While the absence of complications is encouraging, a greater longitudinal period would be beneficial in further evaluating the safety and efficacy of the Passio™ system. Whilst our evaluation focused primarily on chest pain VAS scores, we recognise the importance of comprehensively assessing other relevant outcomes, such as overall healthcare costs and length of drainage. Despite these limitations, the positive trends observed in patient-reported pain scores warrant further investigation in larger, multi-centred, controlled studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our analysis provides promising preliminary evidence for the potential benefits of the Passio™ digital drainage system in improving patient comfort during IPC drainage, particularly in the presence of an NEL. Furthermore, the absence of device-related complications highlights the safety and reliability of the Passio™ digital drainage system. While acknowledging the limitations of a small sample size and non-randomised design, these findings encourage the consideration of larger, controlled trials to further evaluate the impact of the Passio™ digital drainage system on patient outcomes and healthcare resource utilisation.

Author Contributions

R.K.P. was the service evaluation lead. R.K.P. and T.W. developed the concept and evaluation protocol. T.W., A.M., F.H. and S.J. collected data and carried out data analysis. T.W., A.M., F.H., S.J., R.C.S. and R.K.P. drafted this manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This evaluation was registered as a quality improvement project with the local clinical audit team in the hospital (Audit No. 12067). In accordance with local research governance policy, formal ethical approval was not required. The local New Interventional Procedures Advisory Group (NIPAG) was also consulted, and a full NIPAG application was not required as the digital drainage was considered a minor modification to existing IPC practice, and the digital device was considered intuitive from the user’s point of view.

Informed Consent Statement

This project did not have a separate consent form, and consent was obtained with the standard consent form that the institution used for clinical encounters.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We want to extend our sincere gratitude to Bearpac Medical for providing 10 Passio™ IPC starter kits through the local distributor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Bearpac Medical provided 10 Passio™ IPC starter kits through the local distributor, but was not involved with the evaluation. Bearpac Medical had no role in the design of this evaluation; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of this manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations were used in this manuscript:

| MPEs | Malignant Pleural Effusions |

| NEL | Non-Expandable Lung |

| IPCs | Indwelling Pleural Catheters |

| PNS | Pleural Nurse Specialist |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| F2F | Face-to-Face |

Appendix A. Baseline Questionnaire Given to All Patients after IPC Insertion

Name: S number:

Date: Time of drainage:

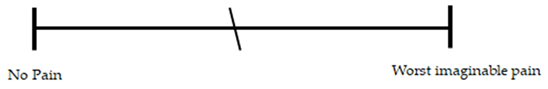

- Please place a mark on the line (as shown in example below), to indicate your level of breathlessness or chest pain related to your Indwelling Pleural Catheter (IPC) drainage. Please do this at the times specified in parts (a) to (g) below.

- This is an example of how we would like you to mark your score.

- Please, also record here any pain relief medication you have taken on this day, including the time which you took it:

- (a)

- Please score your chest pain before you start to drain your IPC.

- (b)

- Please score your breathlessness before you start to drain your IPC.

- (c)

- Please score your chest pain during the middle of your IPC drainage process.

- (d)

- Please score your chest pain at the end of your drainage, when the fluid stops coming.

- (e)

- Please score your chest pain 10 minutes after the end of your drainage.

- (f)

- Please score your chest pain 1 hour after the end of your drainage.

- (g)

- Please score your breathlessness 1 hour after the end of your drainage.

- Please now answer the following questions:

- (1)

- Please state here, by circling YES or NO, if you experienced coughing during drainage of your IPC today:

YES NO

- (2)

- If you experienced pain or coughing during drainage of you IPC, did your nurse or you slow down the speed of drainage?

YES NO

- (3)

- Did slowing down the speed of drainage improve your pain and/or coughing?

YES NO N/A

- (4)

- Please state here, the amount of fluid you drained from your IPC on this occasion:

mls

mls- (5)

- How long did it take to complete your IPC drainage today?

Minutes

Minutes- Please bring this back to your next appointment with the Pleural Nurses. If you have any questions, please contact the Pleural Nurses on 0116 2583975.

- Thank you.

Appendix B. Post-Passio IPC Digital Drainage Questionnaire

Name: S number:

Date: Time of drainage:

- Please place a mark on the line (as shown in example below), to indicate your level of breathlessness or chest pain related to your Indwelling Pleural Catheter (IPC) drainage today. Please do this at the times specified in parts (a) to (g) below.

- This is an example of how we would like you to mark your score.

- Please, also record here any pain relief medication you have taken on this day, including the time which you took it:

- (a)

- Please score your chest pain before you start to drain your IPC.

- (b)

- Please score your breathlessness before you start to drain your IPC.

- (c)

- Please score your chest pain during the middle of your IPC drainage process.

- (d)

- Please score your chest pain at the end of your drainage, when the fluid stops coming.

- (e)

- Please score your chest pain 10 minutes after the end of your drainage.

- (f)

- Please score your chest pain 1 hour after the end of your drainage.

- (g)

- Please score your breathlessness 1 hour after the end of your drainage.

- Please now answer the following questions:

- (1)

- Please circle YES or NO, if you experienced coughing during drainage of your IPC today:

YES NO

- (2)

- If you did experienced pain or coughing during drainage today, did your nurse or you slow down the speed of drainage?

YES NO

- (3)

- Did slowing down the speed of drainage improve your pain and/or coughing?

PAIN YES NO N/A

COUGH YES NO N/A

- (4)

- Please circle the maximum drainage speed on your Passio pump which you used for today’s drainage.

1 2 3 4

- (5)

- At any point during your drainage today, did you reduce the drainage speed on your Passio pump?

YES NO

- (6)

- If applicable, please state the reason for reducing the drainage speed.

PAIN COUGHING OTHER (please state below)

- (7)

- Which drainage speed were you most comfortable using today?

1 2 3 4

- (8)

- Please state here, the amount of fluid you drained from your IPC today:

mls

mls - (9)

- How long did it take to complete your IPC drainage today?

minutes

minutes- Please bring this back to your next appointment with the Pleural Nurses at Glenfield Hospital. If you have any questions, please contact the Pleural Nurses on 0116 2583975.

- Thank you.

References

- Bhatnagar, R.; Maskell, N. The modern diagnosis and management of pleural effusions. BMJ 2015, 351, h4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piggott, L.M.; Hayes, C.; Greene, J.; Fitzgerald, D.B. Malignant pleural disease. Breathe 2023, 19, 230145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.; Fysh, E.T.H.; Smith, N.A.; Lee, P.; Kwan, B.C.H.; Yap, E.; Horwood, F.C.; Piccolo, F.; Lam, D.C.L.; Garske, L.A.; et al. Effect of an Indwelling Pleural Catheter vs Talc Pleurodesis on Hospitalization Days in Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusion: The AMPLE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibby, A.C.; Dorn, P.; Psallidas, I.; Porcel, J.M.; Janssen, J.; Froudarakis, M.; Subotic, D.; Astoul, P.; Licht, P.; Schmid, R.; et al. ERS/EACTS statement on the management of malignant pleural effusions. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1800349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodtger, U.; Hallifax, R.J. Epidemiology: Why is pleural disease becoming more common? In Pleural Disease (ERS Monograph); Maskell, N.A., Laursen, C.B., Lee, Y.C.G., Rahman, N.M., Eds.; European Respiratory Society: Sheffield, UK, 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.E.; Rahman, N.M.; Maskell, N.A.; Bibby, A.C.; Blyth, K.G.; Corcoran, J.P.; Edey, A.; Evison, M.; de Fonseka, D.; Hallifax, R.; et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023, 78, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller-Kopman, D.J.; Reddy, C.B.; DeCamp, M.M.; Diekemper, R.L.; Gould, M.K.; Henry, T.; Iyer, N.P.; Lee, Y.C.G.; Lewis, S.Z.; Maskell, N.A.; et al. Management of Malignant Pleural Effusions. An Official ATS/STS/STR Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolaccini, L.; Viti, A.; Terzi, A. Management of malignant pleural effusions in patients with trapped lung with indwelling pleural catheter: How to do it. J. Vis. Surg. 2016, 2, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, C.A.; Masudi, T.; Thorpe, J.A.; Papagiannopoulos, K. Malignant pleural effusion in the presence of trapped lung. Five-year experience of PleurX tunnelled catheters. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 9, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.E.; Mishra, E.K.; Kahan, B.C.; Wrightson, J.M.; Stanton, A.E.; Guhan, A.; Davies, C.W.H.; Grayez, J.; Harrison, R.; Prasad, A.; et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: The TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012, 307, 2383–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asciak, R.; Mercer, R.M.; Hallifax, R.J.; Hassan, M.; Bedawi, E.; McCracken, D.; Kanellakis, N.I.; Wrightson, J.M.; Psallidas, I.; Rahman, N.M. Does attempting talc pleurodesis affect subsequent indwelling pleural catheter (IPC)-related non-draining septated pleural effusion and IPC-related spontaneous pleurodesis? ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00208–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganandan, S.; Azzopardi, M.; Fitzgerald, D.B.; Shrestha, R.; Kwan, B.C.H.; Lam, D.C.L.; De Chaneet, C.C.; Ali, M.R.S.R.; Yap, E.; Tobin, C.L.; et al. Aggressive versus symptom-guided drainage of malignant pleural effusion via indwelling pleural catheters (AMPLE-2): An open-label randomised trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahidi, M.M.; Reddy, C.; Yarmus, L.; Feller-Kopman, D.; Musani, A.; Shepherd, R.W.; Lee, H.; Bechara, R.; Lamb, C.; Shofer, S.; et al. Randomized Trial of Pleural Fluid Drainage Frequency in Patients with Malignant Pleural Effusions. The ASAP Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, R.; Reid, E.D.; Corcoran, J.P.; Bagenal, J.D.; Pope, S.; Clive, A.O.; Zahan-Evans, N.; Froeschle, P.O.; West, D.; Rahman, N.M.; et al. Indwelling pleural catheters for non-malignant effusions: A multicentre review of practice. Thorax 2014, 69, 959–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, M.; Dhillon, S.S.; Attwood, K.; Saoud, M.; Alraiyes, A.H.; Harris, K. Management of Benign Pleural Effusions Using Indwelling Pleural Catheters: A Sys-tematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest 2017, 151, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub, M.; Saqib, A.; Castellano, M. Indwelling pleural catheters: Complications and management strategies. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 4659–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, C.; Davies, H.E.; Muruganandan, S.; Lui, M.M.S.; Lau, E.P.M.; Lee, Y.C.G. Indwelling Pleural Catheter: Management of Complications. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 44, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.A.; Deschner, E.; Dhaliwal, I.; Robinson, M.; Li, P.; Kwok, C.; Cake, L.; Dawson, E.; Veenstra, J.; Stollery, D.; et al. Patient perspectives on the use of indwelling pleural catheters in malignant pleural effusions. Thorax 2023, 78, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrightson, J.M.; Fysh, E.; Maskell, N.A.; Lee, Y.C. Risk reduction in pleural procedures: Sonography, simulation and supervision. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2010, 16, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, D.; Lamb, C.R.; Quadri, S.M. Using a Novel Digital Pleural Drainage Device: A Proof of Concept. C23. PLEURAL DISEASE, CF, AND OTHER MAGICAL CREATURES. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, A4338. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, H.; Barton, E.; Beech, E.; Patole, S.; Stadon, L.; Maskell, N. Does a novel Indwelling Pleural Catheter drainage system improve patient experience? Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 62, OA1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barozzi, L.; Biagio, L.S.; Meneguzzi, M.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Walpoth, B.H.; Faggian, G. Novel, digital, chest drainage system in cardiac surgery. J. Card. Surg. 2020, 35, 1492–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.