Abstract

Sedimentary dynamics in the Palamós Canyon are influenced by river inputs and storm resuspension, as well as by bottom trawling on the canyon flanks. In this study, we estimate recent sediment deposition patterns along the canyon axis using the excess activity concentration of the short-lived radiotracer 234Th (half-life of 24.1 days). Sediment cores were obtained at various locations along the canyon axis from a depth of approximately 800 m to 2100 m in June 2023 and August 2024. Excess 234Th (234Thxs) was detected in all sampled sites with variable penetration depths (0.5–3.5 cm). 234Thxs-derived estimations of mixing rates decreased downcanyon from up to 15.6 cm2 y−1 at the canyon head (~800 m) to negligible mixing at the canyon mouth (~2100 m). 234Thxs inventories, a proxy of recent sediment deposition, were high (1800–3490 Bq m−2) at the canyon head and at the upper canyon (~1400 m) close to fishing grounds and decreased downcanyon (82–694 Bq m−2) at the lower canyon (~1800 m) and canyon mouth. Inventories varied 2-fold across years presumably attributed to enhanced riverine and bottom trawling sediment fluxes. Similar 234Th-derived sediment deposition patterns can be found in submarine canyons worldwide, highlighting the value of this radiotracer for sedimentary dynamics studies in such complex environments.

1. Introduction

Submarine canyons incise the continental margins and can favor transport of particles from continental shelves and upper slope regions towards the deep sea [1]. While near 6000 canyons have been mapped globally [2], they differ in topography and location, which has implications for the connectivity and efficiency of these canyons as across-margin conduits of particulate matter [3,4]. Although particle fluxes in canyons are variable, a general decreasing trend of particle flux and sedimentation rates, with increasing distance from coastal particle sources and water depth is expected. Particle transfer into submarine canyons can be intensified by high-energy hydrodynamic natural events, such as seasonal storms and dense shelf water cascading [1], or through sediment resuspension by anthropogenic activities, such as bottom trawling (e.g., [5]). Depending, among others, on the frequency and strength of such sediment transport events, particulate matter is preferentially deposited in the upper- and middle-canyon regions or remobilized and transported further downslope along the canyon axis, towards the adjacent basin [1].

Canyons are among the most biologically productive ecosystems on the planet (e.g., [6,7]) and can sequester large quantities of particulate organic carbon (POC), primarily due to the high fluxes of particulate matter occurring in these systems [8,9]. Vertical export of POC through the water column, from surface waters to the canyon seabed, can be enhanced during marine algae blooms [10]. Also, terrigenous POC discharged by rivers can reach the canyon by lateral advection from the shelf during energetic sediment transport events [11,12]. Benthic communities within canyons may benefit from increased POC fluxes, depending on the quality of the organic fraction reaching the seafloor [13,14].

Subject of this study, the Palamós Canyon, is located on the northwestern Mediterranean margin (Figure 1). Sediment transport is active in this submarine canyon and importantly influenced by natural and anthropogenic resuspension events [15,16]. Shelf sediment resuspension is efficiently induced during easterly storms occurring in this region in autumn and winter [15], which can be enhanced by the presence of dense shelf waters loaded with particles, which can cascade into the Palamós canyon head [17,18]. Bottom trawling on the Palamós canyon flanks also produces sediment gravity flows channelized through canyon tributaries towards the canyon axis, although the magnitude of trawling-derived sediment gravity flow generally decreases as the fishing season advances [16,18]. In this way, sediment resuspension by bottom trawling has increased sedimentation rates within the Palamós canyon axis on a decadal scale, as provided by lead-210 (210Pb) chronology [19]. However, the spatio-temporal variations in recent sediment deposition in Palamós Canyon have not yet been studied on seasonal time scales and will be addressed in this study using the naturally occurring radionuclide thorium-234 (234Th).

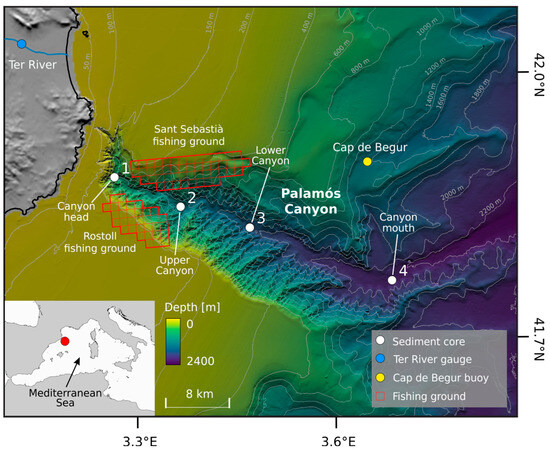

Figure 1.

Bathymetric map showing the sampling locations along the axis of the Palamós Canyon. The coring sites are shown as white circles. The Ter River gauging site and Cap de Begur buoy are indicated with blue and yellow markers, respectively. The main bottom trawling fishing grounds along both canyon flanks are shown as red-outlined areas, with grid cells based on vessel monitoring system (VMS) fishing effort data. Inset: The study area within the northwestern Mediterranean is indicated by a red marker. Map created using QGIS 3.34.

210Pb (T1/2 = 22.3 years) has been extensively used to study sedimentation processes in the marine environment, providing average sedimentation rates over decadal timescales [20]. However, short-term sediment fluxes to the seafloor and seasonal and interannual variability in sediment deposition needs to be resolved using radionuclides with a shorter half-life, such as 234Th (T1/2 = 24.1 days). This radionuclide allows to estimate recent sedimentation processes over the last months, such as depositional pulses due to tidal influence, river flooding, or environmental pollution among others [21,22,23].

234Th is produced by the decay of the ubiquitous, long-lived uranium-238 (238U; T1/2 = 4.5·109 years). Given its high particle-reactivity, 234Th in the water column is adsorbed onto sinking particles and reaches the seafloor via particle transport, leading to an excess 234Th (234Thxs) signal in surface sediment with respect to 234Th in secular equilibrium with 238U found naturally in marine sediments [24,25]. Due to its relatively short half-life, the 234Thxs signal limits the time frame in which the particles forming the sediment layer were deposited on the seabed to approximately the last 120 days (five half-lives of 234Th). Analyzing 234Thxs inventories can be used to assess relative changes in seasonal or episodic transport and deposition of sediment, where higher 234Thxs inventories relate to higher recent sediment accumulation by vertical and lateral inputs [25,26]. With time, the 234Thxs activity concentration in sediments decreases due to radioactive decay, as well as by diffusive mixing of particles across sediment layers [25,27]. Thus, 234Thxs should mainly be present in recently deposited surface sediments. The detection of 234Thxs deep in the sediment therefore indicates diffusive mixing of sediment caused by biological [24,28] or physical [26,29] processes. Based on the 234Thxs concentration profile, the mixing intensity (Db), also referred to as a bioturbation coefficient when benthic bioturbating organisms are present, can be estimated [27,28].

In this study, we used 234Thxs to assess short-term sediment deposition patterns in the Palamós Canyon. We report surface 234Thxs activity concentrations, penetration depths, inventories and mixing rates based on 234Thxs profiles from sediment cores collected along the canyon axis in the summer of 2023 and 2024. Excess 234Th inventories are interpreted as a proxy for the magnitude of recent sediment deposition and further evaluated considering the magnitude of both natural and trawling-derived sediment transport events that may have influenced sediment distribution during the spring-summer season. Additionally, we present a compilation of studies that have used 234Th to investigate short-term sedimentary deposition in submarine canyons, collectively enhancing our understanding of particle transport on continental margins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The Palamós canyon head has an approximate N-S orientation and cuts into the continental shelf at a distance of 3 km from the coastline (Figure 1). The canyon axis is oriented in a WNW-ESE direction with the Liguro-Provençal-Catalan Current (or Northern Current) flowing almost perpendicular to the canyon in a mean NE-SW direction [30]. The canyon axis spans up to 40 km, being characterized by two distinct domains: an inner domain incising the continental margin until the canyon axis reaches approximately 1200 m water depth, experiencing higher sediment load than the outer domain below 1200 m water depth [15]. The mouth of the Ter River is located 10 km north from the Palamós canyon head and represents an important source of sediment into the canyon during events of flooding [15,31]. The mean water discharge was 9 ± 30 m3 s−1 over the five most recent years (2019–2024) including the sampling periods, with maximum annual flows of 9 m3 s−1 in 2023 and 18 m3 s−1 in 2024 (hydrological data available on the ACA website [32]). However, peak flows of >100 m3 s−1 during flood events have been recorded for Ter River (e.g., [31,33]). Furthermore, this canyon supports an industrialized fleet of trawl fishing vessels targeting almost exclusively the coveted red-and-blue deep-sea shrimp (Aristeus antennatus) trawling a depth range of 400–800 m along the canyon flanks, namely the Sant Sebastià fishing ground on the northern flank and the Rostoll fishing ground on the southern flank [19] (Figure 1).

2.2. Sample Collection

Sediment cores preserving the sediment–water interface were collected along the Palamós canyon axis on 29 June 2023 (ARCO-1 cruise) and from 16 to 22 August 2024 (ARCO-2 cruise) using a KC Denmark 6-tube multicorer (KC Denmark A/S, Silkeborg, Denmark) (Figure 1). Sediment sampling took place along the canyon axis with station 1 at the canyon head (~800 m), station 2 at the upper canyon in the vicinity of the fishing grounds (~1400 m), station 3 at the lower canyon (~1800 m) and station 4 at the canyon mouth (~2100 m). Station 4 could not be sampled in 2023 due to unfavorable weather conditions and limited cruise time, whereas all four stations were sampled in 2024. Within 24 h of retrieval, the cores were sliced at 0.5 cm intervals from surface until 10 cm depth on deck using a core extruder. Each section was sealed in plastic bags and frozen at −20 °C until further processing. Sediment samples were weighed before (wet weight), as well as after drying (dry weight) in an oven at 60 °C to a constant weight (ARCO-1) or via freeze-drying (ARCO-2). Dry weight was corrected for salt content assuming a pore-water salinity of 38. Dry bulk density (in g cm−3) was calculated as dry weight divided by total sample volume, estimated from seawater and sediment grain densities of 1.025 g cm−3 and 2.65 g cm−3, respectively [34].

2.3. Gamma Spectrometry and 234Th Quantification

Approximately 5.5 g of sediments was ground and homogenized with a ceramic mortar and pestle, and then sealed in vials for gamma measurements. 234Th gamma emissions (63.3 keV) were measured within 10 weeks (<3 half-lives of 234Th) of sample collection using well-type high-purity germanium detectors for 8 h to 4 days until reaching a minimum of 400 counts. The gamma-spectra were analyzed using the Genie 2000 software (v2.1A) to calculate net peak areas while accounting for background and associated counting uncertainties (Canberra Industries, Inc., Meriden, CT, USA). Detectors were calibrated for the vial geometry by measuring a commercial standard solution (MCR-2009-018) of known gamma activities (60–1836 keV). In addition, the laboratory participates regularly in IAEA intercomparisons obtaining successful results for 234Th in solid materials. For each station, sediment samples from surface (0–0.5 cm), intermediate (4.5–5.0 cm) and deep (9.5–10 cm) layers were remeasured >5 months after sample collection to obtain a mean supported activity concentration of 234Th (234Theq; Supplementary Table S1) equivalent to its parent radionuclide 238U after reaching secular equilibrium.

2.4. Excess 234Th-Derived Calculations of Inventories and Mixing Rates

The excess 234Th activity concentration (234Thxs) of each sediment core section was determined by subtracting 234Theq from the measured 234Th activity concentration (234Thmeas), and correcting for the decay occurred during the time (t) elapsed between sampling and the midpoint of counting, with referring to the decay constant of 234Th:

The 234Thxs penetration depth is defined as the deeper boundary of the core section where negligible 234Thxs activity concentrations were observed when considering their uncertainties. 234Thxs inventories were calculated as the sum of products of 234Thxs activity concentrations in the core sections, its corresponding dry bulk density and sampling section height:

234Thxs of sections excluded from measurement were extrapolated as the mean of the adjacent upper and lower measured sections (Supplementary Table S1).

Although sedimentation rates in the Palamós canyon axis can be high (2.4 cm y−1; [19]), they are still sufficiently low relative to the exponential decrease of 234Thxs activity concentration in the sediment so that the 234Thxs profile should be driven by diffusive mixing [35]. Hence, mixing rates (Db) were calculated for each core as described by Schmidt et al. [28], which assumes negligible influence of sedimentation rates in the 234Thxs activity concentration profile:

where z is the midpoint depth of each sediment section, 234 refers to the 234Thxs activity concentration at the sediment–water interface, and denotes the decay constant of 234Th. The data were analyzed and visualized in Python (version 3.10.) using the packages pandas (v1.5.2), NumPy (v1.23.5), SciPy (v1.10.1), and Matplotlib (v3.6.2). Weighted least squares regression was performed on natural log-transformed 234Thxs activity concentrations versus z, with weights assigned based on the associated uncertainties of the measurements using the statsmodels package (v0.14.4) (see regression metrics in Supplementary Table S1). Db values for each station were calculated using Equation (2) with propagated slope uncertainties.

2.5. Evaluation of Riverine Discharge, Storm Occurrence, and Fishing Effort

Discharge data from the nearby Ter River (see gauging site in Figure 1), monitored daily and published online by the Agència Catalana de l’Aigua [32], was used to compare timings and intensity of potential riverine sediment input to the Palamós canyon head region during the four months (~120 days) prior to the midpoint of sampling (1 March 2023–29 June 2023 for ARCO-1; 22 April 2024–20 August 2024 for ARCO-2).

Significant wave height (Hs) data was retrieved from hourly logging at the Cap de Begur buoy (3.65° E, 41.90° N; Figure 1) collected and made publicly available within the Puertos del Estado monitoring network [36]. Storms within the same timeframe as the river discharge data were identified by prolonged sustained Hs of >2 m for a duration of >6 h [37]. Based on previous studies [17,18], easterly storms influence sediment transport in the study region more than the more frequent northerly storms. Therefore, storms were divided into easterly (60–120°) and northerly (330–30°) storm events based on their mean wave direction.

The cumulative fishing effort during the ~120 days preceding the midpoint of sampling, analogous to the time periods analyzed for river discharge and Hs, was obtained over the same region for 2023 and 2024, and used to evaluate the resuspension impacts by trawling activities along the canyon flanks (Figure 1). Monthly fishing effort (in h km−2) in the surroundings was analyzed and provided by ICATMAR based on vessel monitoring system (VMS) data of bottom trawlers of Palamós harbor for 2023 and 2024 [38]. A speed filter between 1.5 and 4.5 knots was applied to identify fishing activities, and their tracks were interpolated to 10 min using 2-hourly VMS data, considering the direction of navigation. Monthly fishing effort was obtained from 1 × 1 km grid cells on each flank (see grid cell size in Figure 1). The cells with the highest total fishing effort over the four months prior to sampling (>92 h km−2) on both fishing grounds revealed the main trajectory of fishing vessels. Seven cells per fishing ground, following these trajectories, were selected across years to calculate the cumulative effort for both flanks, accounting for the fraction of monthly data corresponding to the respective time period.

2.6. Global Compilation of 234Thxs Parameters from Submarine Canyons

A global compilation was generated to explore the application of 234Th as a tracer for recent sedimentation in submarine canyons [39]. We conducted a search across Google Scholar up until 08 September 2025 for periods encompassing 1979–2025, and obtained 123 search results using the terms: (“Excess 234Th” OR “Excess 234 Th” OR “Excess Th-234” OR “Excess Thorium-234”) AND (“submarine canyon” OR “canyon” OR “off-shelf”) AND (“sediment core” OR “sediment samples” OR “core” OR “gamma spectrometry” OR “gamma spectroscopy” OR “gamma counting” OR “radiochemical analysis” OR “radioisotopic”). After duplicate removal, 121 publications were thoroughly inspected for content. Publications reporting sedimentary 234Th data in canyon environments were selected, resulting in a compilation of data from 25 publications. Data on 234Thxs parameters, sampling methodology, and contextual information of sediment cores obtained in submarine canyon environments were carefully extracted using the information given in the main text, tables, figures, and supplementary files. Latitude, longitude, and sampling dates were assigned to the midpoint or the sampling month when not explicitly stated. Gamma spectrometry was applied as the counting method, with one exception measured by beta counting. In 12 studies, data was also provided from the shelf, slope, or abyssal plain near the canyon. If the data were not provided in tables, a web-tool was used for manual extraction [40]. The compilation includes surface 234Thxs activity concentrations, 234Thxs penetration depths, 234Thxs inventories, and Db from canyon studies with coring sites inside canyons and, additionally, near those canyons. The surface 234Thxs activity concentrations correspond to mean values of the surface sediment section of a given thickness (0.1–2 cm) as reported in the original publication. If full profiles of 234Thxs activity concentrations were given, but not the 234Thxs penetration depth, this value was approximated using the criteria described above (see Section 2.4).

3. Results

3.1. Excess 234Th Profiles, Inventories and Mixing Rates

Surface 234Thxs activity concentrations, penetration depths, inventories, and mixing rates (Db) for all the collected cores are provided in Table 1 and described below in detail. Data show a general downslope decrease for all these variables. Comparing the cores from stations 1 to 3 across years revealed interannual variations in the 234Thxs parameters, particularly at station 2 at the upper canyon (except for surface activity concentration), whereas the cores from station 1 at the canyon head and station 3 at the lower canyon showed comparatively smaller differences between years.

Table 1.

Sampling information and 234Th data of sediment cores, including surface 234Thxs activity concentration (0–0.5 cm section), 234Thxs penetration depth, 234Thxs inventories and mixing rates (Db).

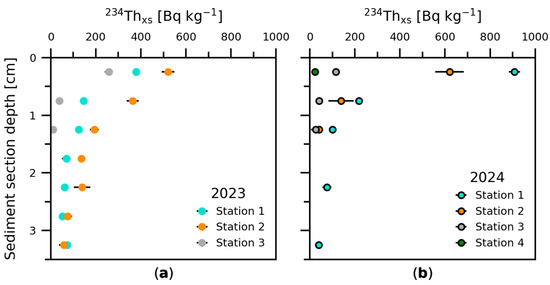

234Thxs activity concentration was detected in the surface layer of all collected sediment cores and ranged between 908 ± 25 and 23 ± 8 Bq kg−1 with the highest value recorded at station 1 and the lowest at station 4, located at the canyon mouth (Table 1; Figure 2). The decrease in surface 234Thxs activity concentrations of the cores from station 1 to station 3 was 30% in 2023 and almost 90% in 2024. Comparing the two cruises, higher surface 234Thxs activity concentrations were recorded in 2024 at station 1 (2.4-fold increase) and station 2 (1.2-fold increase) in comparison to 2023, whereas station 3 showed a lower surface 234Thxs activity concentration in 2024 (2.2-fold decrease) compared to 2023.

Figure 2.

Depth profiles of 234Thxs activity concentrations for sediment cores collected (a) in 2023 and (b) in 2024.

Following the general downslope decreasing pattern, 234Thxs penetration depths in the cores were greatest at station 1, reaching 3.5 cm depth, and then became shallower in the cores located further downcanyon, with depths of 1.5 cm at station 3 and 0.5 cm at station 4 (Table 1). The 234Thxs penetration depth at station 2 varied between years, reaching 3.5 cm in 2023 and 1.5 cm in 2024. 238U activity concentrations (equal to supported 234Th activity concentrations; 234Theq), remeasured after the decay of 234Thxs, varied between 18 ± 2 and 25 ± 3 Bq kg−1 across all cores (Supplementary Table S1). In the 2023 station 2 core, first measurements of 234Th activity concentrations stabilized below 3.5 cm at a mean value of 41 ± 6 Bq kg−1, which was used as 234Theq for this core (Supplementary Table S1).

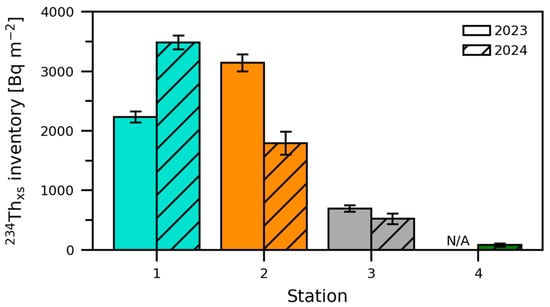

Inventories of 234Thxs showed a clear downcanyon decrease, ranging from 3490 ± 120 Bq m−2 at station 1 to 82 ± 26 Bq m−2 at station 4 (Table 1; Figure 3). Similar to surface 234Thxs activity concentrations, 234Thxs inventories were highest at stations 1 or 2 and lowest at stations 3 and 4. Higher 234Thxs inventories were recorded in 2024 at station 1 (1.6-fold increase), whereas cores at station 2 (1.7-fold decrease) and station 3 (1.3-fold decrease) showed lower 234Thxs inventories that year compared to 2023.

Figure 3.

234Thxs inventories at stations 1 to 4 in 2023 (open bars) and 2024 (hatched bars). Error bars represent the inventory uncertainty of individual core measurements.

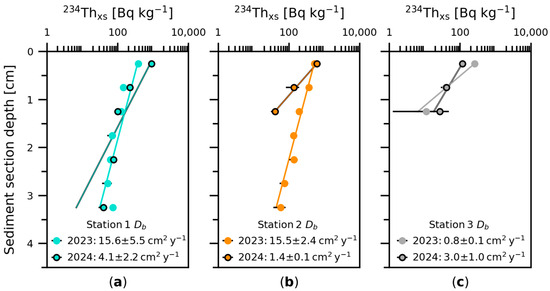

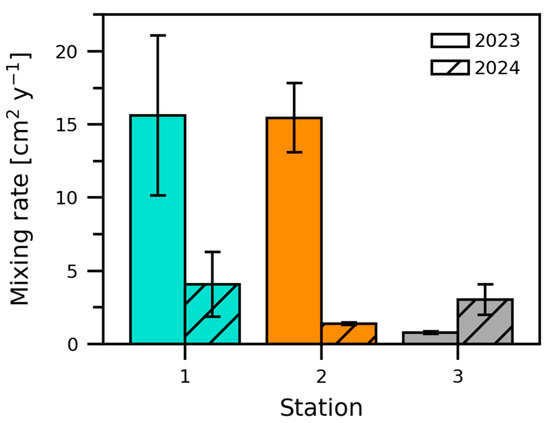

In both sampling cruises, stations 1 to 3 exhibited an exponential downcore decrease in 234Thxs activity concentrations, which was used to calculate Db (Table 1; Figure 4 and Figure 5; R2 values provided in Supplementary Table S1). At station 4, no 234Thxs signal was detected below 0.5 cm, and therefore Db could not be determined. Across cores in both years, the highest Db values were recorded in 2023 at station 1 (15.6 ± 5.5 cm2 y−1) and station 2 (15.5 ± 2.4 cm2 y−1). Compared to these, the Db value at station 3 that same year was an order of magnitude lower (0.8 ± 0.1 cm2 y−1), mirroring the general downslope decreasing trend observed in the other 234Thxs parameters. In 2024, Db values at stations 1 and 2 (4.1 ± 2.2 and 1.4 ± 0.1 cm2 y−1, respectively) exhibited a 4- to 11-fold decrease compared to 2023. In contrast, at station 3, Db increased 4-fold compared to 2023, reaching 3.0 ± 1.0 cm2 y−1 in 2024. That year, the along-canyon pattern of Db was marked by its lowest mixing rate at station 2.

Figure 4.

Depth profiles of exponential decrease of 234Thxs activity concentration on log-scale used for the calculation of mixing rates (Db) for 2023 and 2024 sampling campaigns showing (a) station 1, (b) station 2, and (c) station 3. Station 4 could not be sampled in 2023 and the sediment core collected in 2024 only presented detectable 234Thxs activity concentration in the upper 0.5 cm, hindering the calculation of mixing rate.

Figure 5.

234Thxs-derived mixing rates at stations 1 to 3 in 2023 (open bars) and 2024 (hatched bars). Error bars represent the rate uncertainty of individual core measurements. Station 4 could not be sampled in 2023 and in 2024 only presented detectable 234Thxs activity concentration in the upper 0.5 cm, hindering the calculation of mixing rate.

3.2. River Discharge, Storms and Fishing Effort

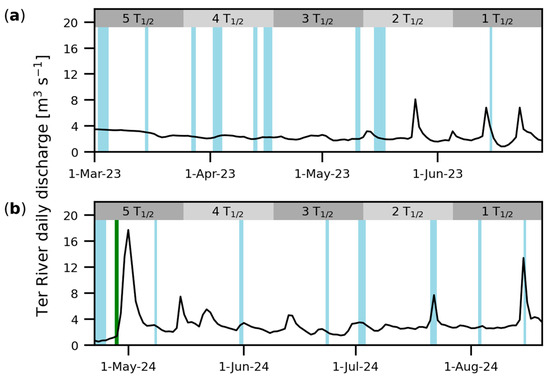

Within a timeframe of ~120 days, equivalent to approximately five half-lives of 234Th prior to sampling, the Ter River discharge in 2023 reached maximum values of approximately 9 m3 s−1 at the end of May and approximately 8 m3 s−1 during June, in the weeks before sampling (Figure 6a). In 2023, numerous northerly storms were recorded from March to June, with maximum Hs of 4.2 m recorded at the beginning of March (Figure 6a). No easterly storms occurred during the studied period in 2023. During the same relative period in 2024, a maximum Ter river discharge of approximately 18 m3 s−1 was registered at the beginning of May (Figure 6b); twice as high than the year before. More peaks of river discharge of approximately 7 m3 s−1 occurred mid-May and at the end of July, whereas river discharge peaked again (~13 m3 s−1) in the week leading up to sampling. Prolonged high easterly Hs were observed shortly before the highest peak in river discharge at the end of April 2024, comprising 10 h of elevated Hs of 2.0–2.5 m within a total time span of 13 h (Figure 6b). Northerly storms were observed from the end of April through August, with maximum Hs of 3.9 m at the end of April.

Figure 6.

Ter River daily discharge and the occurrence of storms during the ~120 days prior to sampling (a) in June 2023 and (b) in August 2024. Storm events are indicated according to their duration by vertical shadowed areas in the timelines: easterly storms in green, northerly storms in light blue. A striped horizontal gray bar shows the timeframe of five half-lives of 234Th prior to sampling to differentiate more recent events.

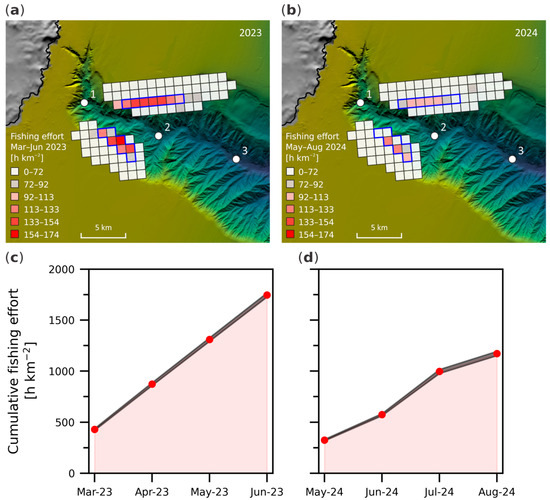

The mean fishing effort over the ~120 days before sampling in 2023 (437 ± 6 h km−2) was considerably higher than that before sampling in 2024 (293 ± 105 h km−2). Also, the cumulative fishing effort along the canyon flanks prior to sampling was 33% higher in 2023 than 2024 (Figure 7). Comparing fishing effort in May and June, shared months within the studied periods and fishing seasons, shows that the fishing pressure was about twice as high on both flanks in 2023 as in 2024 (Figure 7c,d).

Figure 7.

Fishing effort on the main trawling grounds along the flanks of the Palamós Canyon, shown as the sum of computed effort at 1 × 1 km resolution prior to samplings: (a) March–June 2023 and (b) May–August 2024. Sediment coring sites (1–3) are marked as white circles. Cumulative monthly fishing effort over the ~120 days prior to sampling (c) in June 2023 and (d) in August 2024, summed over cells outlined in blue in (a,b). Black shading indicates uncertainty from error propagation of sums.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial and Temporal Variations in Short-Term Sediment Deposition in Palamós Canyon

234Thxs activity concentrations were detected in the surface sediment layer from all sampled sites along the canyon axis at water depths ranging from ~800 to ~2100 m, which confirms the recent deposition of sediment along the entire canyon axis and an active sediment supply to the canyon. The surface 234Thxs activity concentrations and 234Thxs inventories generally decreased downcanyon in both cruises (Figure 2 and Figure 3; Table 1) with the cores of the inner domain (stations 1 and 2) having higher values than those of the outer domain (stations 3 and 4; Figure 1). Unfortunately, some of the inherent fine spatial scale variability could not be accounted for in the reported 234Thxs results due to the lack of analysis in the replicate cores of the multicorer deployments. According to the 234Thxs inventories, the accumulation at the canyon mouth (station 4; ~2100 m) constitutes only 2% of the recent deposition registered at the canyon head (station 1; ~800 m) (Figure 3; Table 1). At the lower canyon (station 3; ~1800 m), the 234Thxs inventories were lower by factors of up to 5 and 7 in 2023 and 2024, respectively, compared to the inner domain (Figure 3; Table 1). A previous study [41] has shown that the average total mass flux near the seafloor in the Palamós Canyon decreased downcanyon, agreeing with the data presented here.

While all sampled stations may receive particles both from horizontal advective fluxes through along-canyon transport and from vertical fluxes of particle settling through the water column, the intensity of these fluxes could impact recent sediment deposition. At the lower canyon, the 234Thxs inventories showed lower interannual variability than the shallower stations of the inner domain. Interannual variability was observed at station 1, with a 36% lower 234Thxs inventory in 2023 than in 2024 (Figure 3). This difference in 234Thxs inventory between years at the head of the canyon, could have been caused by changes in riverine discharge or storms, but not by bottom trawling since the fishing grounds are found further offshore from station 1 (Figure 1). The maximal Ter river discharges within the four months before samplings were similar (9 m3 s−1 in 2023; 18 m3 s−1 in 2024; Figure 6) to the average annual mean value of 9 ± 30 m3 s−1 over 2019–2024 [32], hence we consider that no major flooding occurred within those time periods. An easterly storm was recorded solely in the studied time period in 2024 (maximum Hs of 2.5 m), coinciding within a window of 5 days with the maximum peak in riverine discharge in that time period (~18 m3 s−1). This combined storm and fluvial discharge peak event occurred approximately five half-lives of 234Th before sampling (Figure 6) and could have enhanced shelf resuspension and sediment transport to the canyon, which may have provided higher surface 234Thxs activity concentrations and inventories in 2024 compared to 2023, particularly at station 1 due to its relatively short distance from the coast (Table 1). Yet, it remains unclear whether this event occurred too far back in time with respect to sampling to have had a measurable impact on 234Thxs inventories, and whether shelf sediment transport into the canyon was efficient during the time before sampling. However, the second-highest peak of river discharge before sampling in 2024 (~13 m3 s−1), which still exceeded the maximum discharge recorded during the previous year, occurred in the week leading up to our sampling cruise in mid-August, coinciding with a northerly storm event (Figure 6). This combination of increased riverine discharge and northerly storms could have provided a much larger measurable impact on 234Thxs inventories at station 1, despite the absence of a concurrent easterly storm.

The upper canyon (station 2, ~1400 m) also showed interannual variability with a 234Thxs inventory 1.7-fold higher in 2023 than in 2024 (Table 1). Contrary to the generally decreasing deposition with distance to the shelf observed in 2024, 234Thxs inventories in 2023 suggest that sediment deposition was higher at station 2 than at station 1, thus disrupting the general along-axis decreasing trend in 2023 (Figure 3). In this occasion, the potential causes of interannual variability include bottom trawling activities, since in the Palamós Canyon this practice takes place in fishing grounds distributed along the northern and southern canyon flanks adjacent to station 2 (Figure 1). Fishing activities in the area have been shown to trigger nearly daily sediment gravity flows during the spring and summer months [16,19], thus potentially overruling the typically calm downslope sediment transport characterized by a lack of highly energetic hydrodynamic events. Indeed, these trawling-derived sediment gravity flows have led to an increase in sedimentation rates in the canyon axis at mid-canyon in the 1970s and the early 2000s [19]. This is especially evidenced at approximately 1200 m, at depths overlying station 2, given the presence of tributaries that can channel sediment into the canyon [16]. The higher cumulative fishing effort four months prior to sampling in 2023 in comparison to 2024 (Figure 7) could have transferred higher sediment fluxes from the fishing grounds towards the canyon axis, leading to higher 234Thxs inventories in 2023 than in 2024 at station 2.

Based on VMS data, the fishing effort was higher by ~570 h km−2 (1.5-fold higher) in the four months before sampling in 2023 than during the respective time period in 2024 (Figure 7), similar to the 1.8-fold enhanced 234Thxs inventory at station 2 in 2023 compared to 2024 (Figure 3). The enhanced sediment deposition recorded in 2023 at station 2 could have also been influenced by the time passed between the opening of the fishing season (early March) and sampling (June 2023 vs. August 2024), as the progressive erosion of sediments along the flanks due to trawling reduces the magnitude and intensity of sediment gravity flows as the fishing season advances [16,18]. In addition, the fishing effort indicates that, during the four months before each sampling, the same area was consistently more intensely trawled in 2023 than in 2024 (Figure 7c,d).

4.2. Spatial and Temporal Variation in Mixing Rates in Palamós Canyon

The sedimentation rate in the Palamós canyon axis derived from 210Pb measurements in a sediment core retrieved in 2011 nearby station 3 at 1820 m has been previously reported to range between 1.1 and 2.4 cm y−1 [19]. Despite these relatively high sedimentation rates, given the short half-life of 234Th (24.1 days), a 234Thxs signal should only be detectable at the surface (<1.0 cm) in the absence of mixing. If the 234Thxs penetration depths of 1.5–3.5 cm at stations 1 to 3 were an indicator solely of sediment accumulation, the sedimentation rate over the last four months would be higher (4.5–10.5 cm y−1) than the sedimentation rate derived from 210Pb. Hence, the 234Thxs profiles mainly reflect downward vertical mixing of varying intensity, potentially generated by the activity of burrowing organisms in the surface sediment [25]. Indeed, meiofaunal analyses [42], as well as burrowing tracks detected in the X-radiographs from that same sediment core retrieved nearby station 3 in 2011 [19] indicate that diverse burrowing fauna, capable of mixing the sediment, is inhabiting the Palamós canyon axis surface sediments.

In 2023, 234Thxs penetration depths of 3.5 cm and mixing rates of ~16 cm2 y−1 were equally high at stations 1 and 2, and then lowered to ~1 cm2 y−1 at station 3 (Table 1). This downslope reduction in mixing rates may reflect a gradient of benthic activity along the canyon axis, aligning with earlier reports, which observed a decrease in meiofaunal assemblages with increasing water depth [42].

As observed with the 234Thxs inventories, mixing rates also presented interannual variability. Compared to 2023, mixing rates in 2024 were lower by factors of 4 and 11 at stations 1 and 2, respectively, regardless of showing similarly deep 234Thxs penetration depths (Table 1). Located below active fishing grounds, the 11-fold variability of mixing rates at station 2 between years may be influenced by variable inputs of sediment originating from the flanks’ regions and remobilized through trawling. At station 3, similar inventories were recorded in both years, while the mixing rate was approximately 4-fold higher in 2024 than in 2023 (Table 1; Figure 3 and Figure 5). Indeed, the quality of organic matter delivered into the canyon strongly impacts the magnitude of surface mixing [43]. In Cap-Ferret Canyon (Bay of Biscay), an elevated mixing rate (68.7 cm2 y−1) was observed at mid-canyon at 1035 m water depth, more than four times higher than the values reported here at similar depths, which was attributed to the input of fresh organic material from a spring bloom [44].

4.3. Comparison of Short-Term Deposition in the Canyon Axis with the Adjacent Flanks

234Thxs inventories have been studied on the flanks of the Palamós Canyon in a recent study [33], suggesting that their magnitude is driven primarily by seasonal variations, rather than by the effect of bottom trawling activities. To assess the capacity of this canyon to focus sediment within its axis based on differences in 234Thxs inventories between the axis and the flanks, it is therefore necessary to exclude the influence of seasonality. We hereafter compare our along-axis 234Thxs data with previously published data from flank coring sites at ~500 m water depth, sampled slightly northward from our station 2 in June 2017 [33]. The flank cores were collected at approximately 15 km from the coast, at a similar distance from the coast as our station 2. Although the water depth in the axis site is about 900 m deeper than on the adjacent flank, the 234Thxs inventories reported on the flanks (from 2320 ± 70 to 3182 ± 110 Bq m−2 [33]) are within the range of values observed at ~1400 m water depth at station 2 in the canyon axis (from 1800 ± 190 to 3140 ± 140 Bq m−2, Table 1). The deeper water depth and location below fishing grounds, would allow settling particulate matter to scavenge more 234Th during its downward transport through the water column at station 2, as well as additional scavenging of 234Th when particles are transported from the flank to the axis. However, considering the interannual variability in 234Thxs inventories observed in the present study, quantitative comparisons of inventories at nearby locations may not be reliable, when measured in different years. In contrast to the seemingly similar inventories in this canyon in comparison with the flank, Schmidt et al. [28] found enhanced inventories inside Nazaré Canyon compared to just outside the canyon in the same sampling year.

Interestingly, in a study across the Poverty margin (New Zealand), Alexander et al. [45] found lower 234Thxs inventories in surface sediments than expected based on the overlying water-column concentrations of the parent nuclide, 238U, once the water depth exceeded 600 m. While 234Th scavenging by particles depends largely on the amount of particulate matter available in the water column, other processes, such as lateral fluxes, may modulate the relationship between the water column 234Th flux and the 234Thxs found in the seabed, and therefore ultimately influence the net amount of 234Thxs in the sediment.

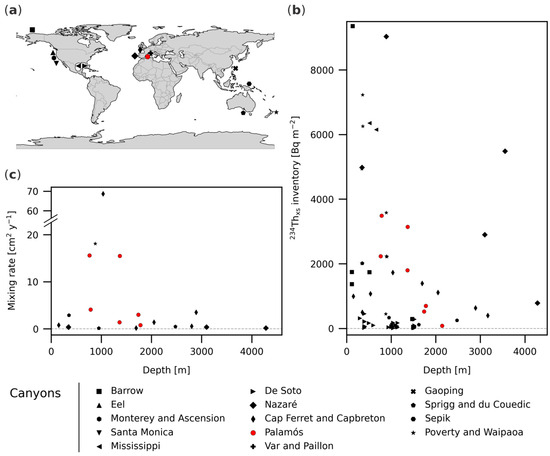

4.4. 234Th Studies in Submarine Canyons

Despite the numerous submarine canyons that incise continental margins on a global scale, the 234Th tracer has seldomly been used to improve our understanding of short-term sedimentary processes in and near canyons around the globe. A global compilation of studies that have used this tracer to assess recent sedimentation processes in submarine canyons identified a total of 26 studies since 1979 [39] including the present work. The compiled studies focus on canyons located along the continental margins of the Arctic, North America (Pacific Ocean), Gulf of Mexico, northeastern Atlantic, northwestern Mediterranean, southern Australia, and western and southwestern Pacific (locations shown in Figure 8a [21,22,23,28,29,33,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]).

Figure 8.

Overview of a global compilation of sedimentary 234Th data in canyons since 1979. (a) Location of canyons. (b) 234Thxs inventories [23,28,44,45,50,52,54,55,61] and (c) 234Thxs-derived mixing rates [28,44,45,58,61] reported from canyons. Note that the mixing rates y-axis in (c) has a scale break. The Palamós Canyon is highlighted in red. Compiled data set available under https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.987505 [39].

A total of 329 234Thxs data values have been collected across four 234Thxs parameters: surface activity concentration, penetration depth, inventory, and mixing rate. Thereof, 243 values were obtained from sediments within the canyons, spanning a depth range from 120 to 4280 m, and 86 values were obtained from their immediate surroundings. In canyons, the most frequently provided parameter is the surface 234Thxs activity concentration (19 of 26 studies) ranging from 20 to 4040 Bq kg−1 with a mean value of 520 Bq kg−1. 10 of 26 studies reported 234Thxs inventories, showing high variability with a range of values between 10 and 50,700 Bq m−2 and a mean value of 2860 Bq m−2 (Figure 8b). 10 of 26 studies reported or provided enough data for extraction of 234Thxs penetration depths (mean of 2 cm, ranging from 0.4 to 24 cm). The least frequently reported 234Thxs parameter is mixing rate (6 of 26 studies) yet encompassing a large range of values from 0.2 to 68.7 cm2 y−1 with a mean of 6.9 cm2 y−1 (Figure 8c). The range of surface 234Thxs activity concentrations (116–908 Bq kg−1), 234Thxs penetration depths (0.5–3.5 cm), 234Thxs inventories (82–3490 Bq m−2) and mixing rates (0.8–15.6 cm2 y−1) recorded in Palamós Canyon at ~800–2100 m depth fall within the values reported in the compiled studies.

Canyons have different sedimentary settings due to their geomorphology, as well as their natural and anthropogenic influences. The accumulation of sediment in canyons or specific parts of canyons on the timescale of 234Th can be caused by various processes [1]. Important seasonal drivers of sedimentation were observed in the compiled studies and include flooding events, storms, typhoons and hurricanes, while anthropogenic influence, such as contamination, caused by a petrogenic blowout, and bottom trawling, was also reported [23,33]. Events leading to enhanced particle flux and greater deposition of sediments in the canyon are expected to produce an increase in 234Thxs inventories due to thorium’s high particle affinity. Comparing inside-canyon 234Thxs inventories with those from adjacent margin sites, when studied simultaneously, can provide estimates of the relative input of fresh particles into the canyon [28].

Studying sedimentary 234Thxs in canyons may reveal patterns of recent sediment deposition across the diverse geomorphologies and sediment transport mechanisms that occur in canyons across the globe. Most studies do not examine in detail the different 234Thxs parameters (surface activity concentration, penetration depth, inventory and mixing rate) and usually focus on only two of them, indicating that the applicability of 234Thxs as a tracer has not been fully explored. Despite the limited number of studies that have used 234Th in submarine canyons, the dynamic nature of the sedimentary processes taking place in these deep-sea environments warrants its applicability and shows the value of this tracer in understanding short-term sedimentation patterns that could otherwise potentially be missed.

5. Conclusions

234Th radiotracer-based analysis in the Palamós Canyon indicated a downslope decreasing trend of recent sediment deposition and mixing rates from the canyon head toward the canyon mouth over the spring and summer of 2023 and 2024. Short-term sediment fluxes and mixing rates appear to be strongly modulated by bottom trawling activities around the canyon flanks, as well as by discharge from the Ter River and by shelf sediment resuspension during storm events, as evidenced by the observed interannual variability in recent sediment deposition. This pronounced interannual variability complicates direct comparisons of 234Thxs inventories and mixing rates among sediment cores collected in different years. Nevertheless, the short half-life of 234Th makes it a powerful tracer for capturing temporal variability in sediment fluxes within submarine canyons, where hydrodynamic forcing is highly variable across event to interannual timescales. In a broader context, the global compilation of 234Th studies in submarine canyons presented here demonstrates the value of this tracer in assessing short-term sediment deposition patterns within them, capturing the wide range of dynamic fluxes that characterize these complex deep-sea canyon environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmse13122383/s1, Table S1: Downcore dry bulk density and 234Th data, including mid-point measurement date, measured activity concentration (234Thmeas, 1st measurement), supported activity concentration (238U, 2nd measurement where 234Theq is equal to 238U) and mean value (±standard deviation) per station, excess activity concentration (234Thxs), excess inventory and weighted least squares (WLS) regression metrics used to calculate mixing rates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, P.P., V.P., M.R.-M. and S.P.; sample processing and data analysis M.S., M.R.-M. and S.P.; data curation, visualization and writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; funding acquisition, P.P. and V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through the ARCO project (TED2021-129426B-I00) led by P.P. and the LOFATE project (PID2023-151302NA-I00) led by V.P. The COCSABO provided additional ship-time under the CONPART project, led by V.P. Additional funds were provided by the BACRAD project (LCF/BQ/PI21/11830020), funded by the “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434) and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie (grant agreement no. 847648). M.S. received funds from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (fellowship CEX2019-000928-S-20-2). S.P. acknowledges support from a SNSF Ambizione project (PZ00P2_223468). M.R.-M. acknowledges support from the Beatriu de Pinós fellowship (2021-BP-00109), the “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434, fellowship code LCF/BQ/PI24/12040022) and the Ramón y Cajal Program (RYC2023-045355-I). V.P. also acknowledges support from the Beatriu de Pinós fellowship (2022-BP-00112) and the Ramón y Cajal Program (RYC2023-045093-I). This work contributes to the ICM-CSIC “Severo Ochoa” Excellence Program (Grant CEX2024-001494-S) and the ICTA-UAB “María de Maeztu” Program for Units of Excellence (Grant CEX2024-001506-M) both funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). Support was also provided by the grants 2021 SGR-433 and 2021 SGR-640 provided by the Generalitat de Catalunya.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and its Supplementary Material. The compilation data set is publicly archived on the data repository PANGAEA® (www.pangaea.de) under the following doi: https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.987505 [39]. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the crews of the B/O García del Cid and B/O Ramón Margalef, as well as the Marine Technology Unit (UTM-CSIC) for their work and support at sea. The authors are grateful to Paula Sabaté, Daniel Romano, Silvia Bianchelli, Anna Salvatori, Berta Sala, Margot White and Ana Manrique-Hernández, who contributed to the collection of samples. The authors thank the members of the Grup de Recerca de Radioactivitat Ambiental de Barcelona (GRAB) at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, particularly Joan Manel Bruach, who assisted with gamma measurements. Cecilia Cabrera and Ruth Durán are acknowledged for their kind support in creating the bathymetric map, and Joan Batista and Joan Salas for providing VMS data to assess fishing effort. The authors also thank Elena Martinez and Silvia de Diago for their support with cruise preparation and sediment samples treatment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Puig, P.; Palanques, A.; Martín, J. Contemporary Sediment-Transport Processes in Submarine Canyons. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2014, 6, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.T.; Whiteway, T. Global Distribution of Large Submarine Canyons: Geomorphic Differences between Active and Passive Continental Margins. Mar. Geol. 2011, 285, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Nichol, S.L.; Harris, P.T.; Caley, M.J. Classification of Submarine Canyons of the Australian Continental Margin. Mar. Geol. 2014, 357, 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, A.; Schwanghart, W. Where and Why Do Submarine Canyons Remain Connected to the Shore During Sea-Level Rise? Insights from Global Topographic Analysis and Bayesian Regression. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL092234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.M.; Kiriakoulakis, K.; Raine, R.; Gerritsen, H.D.; Blackbird, S.; Allcock, A.L.; White, M. Anthropogenic Influence on Sediment Transport in the Whittard Canyon, NE Atlantic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 101, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Arcaya, U.; Ramirez-Llodra, E.; Aguzzi, J.; Allcock, A.L.; Davies, J.S.; Dissanayake, A.; Harris, P.; Howell, K.; Huvenne, V.A.I.; Macmillan-Lawler, M.; et al. Ecological Role of Submarine Canyons and Need for Canyon Conservation: A Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.M.; Demopoulos, A.W.J.; Bourque, J.R.; Mienis, F.; Duineveld, G.C.A.; Lavaleye, M.S.S.; Koivisto, R.K.K.; Brooke, S.D.; Ross, S.W.; Rhode, M.; et al. Submarine Canyons Influence Macrofaunal Diversity and Density Patterns in the Deep-Sea Benthos. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2020, 159, 103249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, D.G.; Huvenne, V.A.I.; De Stigter, H.C.; Wolff, G.A.; Kiriakoulakis, K.; Arzola, R.G.; Blackbird, S. Efficient Burial of Carbon in a Submarine Canyon. Geology 2010, 38, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, K.L.; Rosenberger, K.J.; Paull, C.K.; Gwiazda, R.; Gales, J.; Lorenson, T.; Barry, J.P.; Talling, P.J.; McGann, M.; Xu, J.; et al. Sediment and Organic Carbon Transport and Deposition Driven by Internal Tides along Monterey Canyon, Offshore California. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2019, 153, 103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, L.; Aguzzi, J.; Costa, C.; De Leo, F.; Ogston, A.; Purser, A. The Oceanic Biological Pump: Rapid Carbon Transfer to Depth at Continental Margins during Winter. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M.; Leduc, D.; Nodder, S.D.; Kingston, A.; Swales, A.; Rowden, A.A.; Mountjoy, J.; Olsen, G.; Ovenden, R.; Brown, J.; et al. Novel Application of a Compound-Specific Stable Isotope (CSSI) Tracking Technique Demonstrates Connectivity Between Terrestrial and Deep-Sea Ecosystems via Submarine Canyons. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, S.; Gies, H.; Moccia, D.; Lattaud, J.; Bröder, L.; Haghipour, N.; Pusceddu, A.; Palanques, A.; Puig, P.; Lo Iacono, C.; et al. Distribution and Sources of Organic Matter in Submarine Canyons Incising the Gulf of Palermo, Sicily: A Multi-Parameter Investigation. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 5921–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusceddu, A.; Bianchelli, S.; Canals, M.; Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Durrieu De Madron, X.; Heussner, S.; Lykousis, V.; De Stigter, H.; Trincardi, F.; Danovaro, R. Organic Matter in Sediments of Canyons and Open Slopes of the Portuguese, Catalan, Southern Adriatic and Cretan Sea Margins. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2010, 57, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prouty, N.G.; Mienis, F.; Campbell-Swarzenski, P.; Roark, E.B.; Davies, A.J.; Robertson, C.M.; Duineveld, G.; Ross, S.W.; Rhode, M.; Demopoulos, A.W.J. Seasonal Variability in the Source and Composition of Particulate Matter in the Depositional Zone of Baltimore Canyon, U.S. Mid-Atlantic Bight. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2017, 127, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanques, A.; García-Ladona, E.; Gomis, D.; Martín, J.; Marcos, M.; Pascual, A.; Puig, P.; Gili, J.-M.; Emelianov, M.; Monserrat, S.; et al. General Patterns of Circulation, Sediment Fluxes and Ecology of the Palamós (La Fonera) Submarine Canyon, Northwestern Mediterranean. Prog. Oceanogr. 2005, 66, 89–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, S.; Arjona-Camas, M.; Goñi, M.; Palanques, A.; Masqué, P.; Puig, P. Contrasting Particle Fluxes and Composition in a Submarine Canyon Affected by Natural Sediment Transport Events and Bottom Trawling. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1017052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribó, M.; Puig, P.; Palanques, A.; Lo Iacono, C. Dense Shelf Water Cascades in the Cap de Creus and Palamós Submarine Canyons during Winters 2007 and 2008. Mar. Geol. 2011, 284, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arjona-Camas, M.; Puig, P.; Palanques, A.; Durán, R.; White, M.; Paradis, S.; Emelianov, M. Natural vs. Trawling-Induced Water Turbidity and Suspended Sediment Transport Variability within the Palamós Canyon (NW Mediterranean). Mar. Geophys. Res. 2021, 42, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, P.; Martín, J.; Masqué, P.; Palanques, A. Increasing Sediment Accumulation Rates in La Fonera (Palamós) Submarine Canyon Axis and Their Relationship with Bottom Trawling Activities. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 8106–8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Ortiz, A.; Masqué, P.; Garcia-Orellana, J.; Serrano, O.; Mazarrasa, I.; Marbà, N.; Lovelock, C.E.; Lavery, P.S.; Duarte, C.M. Reviews and Syntheses: 210Pb-Derived Sediment and Carbon Accumulation Rates in Vegetated Coastal Ecosystems—Setting the Record Straight. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 6791–6818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullenbach, B.L.; Nittrouer, C.A. Decadal Record of Sediment Export to the Deep Sea via Eel Canyon. Cont. Shelf Res. 2006, 26, 2157–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, C.-A.; Liu, J.T.; Lin, H.-L.; Xu, J.P. Tidal and Flood Signatures of Settling Particles in the Gaoping Submarine Canyon (SW Taiwan) Revealed from Radionuclide and Flow Measurements. Mar. Geol. 2009, 267, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.R.; Larson, R.A.; Schwing, P.T.; Romero, I.; Moore, C.; Reichart, G.-J.; Jilbert, T.; Chanton, J.P.; Hastings, D.W.; Overholt, W.A.; et al. Sedimentation Pulse in the NE Gulf of Mexico Following the 2010 DWH Blowout. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aller, R.C.; Cochran, J.K. 234Th/238U Disequilibrium in near-Shore Sediment: Particle Reworking and Diagenetic Time Scales. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1976, 29, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller, R.C.; Benninger, L.K.; Cochran, J.K. Tracking Particle-Associated Processes in Nearshore Environments by Use of 234Th/238U Disequilibrium. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1980, 47, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Annett, A.L.; Jones, R.L.; Middag, R.; Mason, R.P. Benthic Deposition and Burial of Total Mercury and Methylmercury Estimated Using Thorium Isotopes in the High-Latitude North Atlantic. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2025, 399, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller, R.C.; Cochran, J.K. The Critical Role of Bioturbation for Particle Dynamics, Priming Potential, and Organic C Remineralization in Marine Sediments: Local and Basin Scales. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; de Stigter, H.C.; van Weering, T.C.E. Enhanced Short-Term Sediment Deposition within the Nazaré Canyon, North-East Atlantic. Mar. Geol. 2001, 173, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.P.; Nittrouer, C.A. Contrasting Styles of Off-Shelf Sediment Accumulation in New Guinea. Mar. Geol. 2003, 196, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, J.; Salat, J.; Tintoré, J. Permanent Features of the Circulation in the Catalan Sea. Ocean. Acta 1988, 9, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Higueras, M.; Martí, E.; Liquete, C.; Calafat, A.; Kerhervé, P.; Canals, M. Riverine Transport of Terrestrial Organic Matter to the North Catalan Margin, NW Mediterranean Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 2013, 118, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agència Catalana de l’Aigua. Available online: https://aplicacions.aca.gencat.cat/sdim21/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Paradis, S.; Goñi, M.; Masqué, P.; Durán, R.; Arjona-Camas, M.; Palanques, A.; Puig, P. Persistence of Biogeochemical Alterations of Deep-Sea Sediments by Bottom Trawling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL091279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdige, D.J. Physical Properties of Sediments. In Geochemistry of Marine Sediments; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nittrouer, C.A.; DeMaster, D.J.; McKee, B.A.; Cutshall, N.H.; Larsen, I.L. The Effect of Sediment Mixing on Pb-210 Accumulation Rates for the Washington Continental Shelf. Mar. Geol. 1984, 54, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertos del Estado. Available online: https://portus.puertos.es/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Mendoza, E.T.; Jiménez, J.A. Vulnerability Assessment to Coastal Storms at a Regional Scale. In Coastal Engineering 2008; World Scientific: Singapore, 2009; Volume 5, pp. 4154–4166. [Google Scholar]

- Ribera-Altimir, J.; Llorach-Tó, G.; Sala-Coromina, J.; Company, J.B.; Galimany, E. Fisheries Data Management Systems in the NW Mediterranean: From Data Collection to Web Visualization. Database 2023, 2023, baad067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierks, M.; Paradis, S.; Roca-Martí, M.; Puigcorbé, V.; Puig, P. Global Database of Sedimentary Excess Thorium-234 (Th-234) in and near Submarine Canyons [Dataset]. PANGAEA 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer Version 4.8. 2024. Available online: https://Automeris.Io/WebPlotDigitizer (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Martín, J.; Palanques, A.; Puig, P. Composition and Variability of Downward Particulate Matter Fluxes in the Palamós Submarine Canyon (NW Mediterranean). J. Mar. Syst. 2006, 60, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pusceddu, A.; Bianchelli, S.; Martín, J.; Puig, P.; Palanques, A.; Masqué, P.; Danovaro, R. Chronic and Intensive Bottom Trawling Impairs Deep-Sea Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8861–8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.; Thomsen, L.; de Stigter, H.C.; Epping, E.; Soetaert, K.; Koning, E.; de Jesus Mendes, P.A. Sediment Bioavailable Organic Matter, Deposition Rates and Mixing Intensity in the Setúbal–Lisbon Canyon and Adjacent Slope (Western Iberian Margin). Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2010, 57, 1012–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Howa, H.; Diallo, A.; Martín, J.; Cremer, M.; Duros, P.; Fontanier, C.; Deflandre, B.; Metzger, E.; Mulder, T. Recent Sediment Transport and Deposition in the Cap-Ferret Canyon, South-East Margin of Bay of Biscay. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2014, 104, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.R.; Walsh, J.P.; Orpin, A.R. Modern Sediment Dispersal and Accumulation on the Outer Poverty Continental Margin. Mar. Geol. 2010, 270, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.R.; Venherm, C. Modern Sedimentary Processes in the Santa Monica, California Continental Margin: Sediment Accumulation, Mixing and Budget. Mar. Environ. Res. 2003, 56, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolliet, T.; Jorissen, F.; Schmidt, S.; Howa, H. Benthic Foraminifera from Capbreton Canyon Revisited; Faunal Evolution after Repetitive Sediment Disturbance. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2014, 104, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaillou, G.; Schäfer, J.; Blanc, G.; Anschutz, P. Mobility of Mo, U, As, and Sb within Modern Turbidites. Mar. Geol. 2008, 254, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, D.R.; McKee, B.; Duncan, D. An Evaluation of Mobile Mud Dynamics in the Mississippi River Deltaic Region. Mar. Geol. 2004, 209, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dail, M.B.; Corbett, D.R.; Walsh, J. Assessing the Importance of Tropical Cyclones on Continental Margin Sedimentation in the Mississippi Delta Region. Cont. Shelf Res. 2007, 27, 1857–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, M.A.; Alleau, Y.; Corbett, R.; Walsh, J.; Mallinson, D.; Allison, M.A.; Gordon, E.; Petsch, S.; Dellapenna, T.M. The Effects of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita on the Seabed of the Louisiana Shelf. Sediment. Rec. 2007, 5, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagstrom, K. Particle Dynamics and Shelf-Basin Interactions in the Western Arctic Ocean Investigated Using Radiochemical Tracers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heimbürger, L.-E.; Cossa, D.; Thibodeau, B.; Khripounoff, A.; Mas, V.; Chiffoleau, J.-F.; Schmidt, S.; Migon, C. Natural and An-thropogenic Trace Metals in Sediments of the Ligurian Sea (Northwestern Mediterranean). Chem. Geol. 2012, 291, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiker, J.M. Spatial and Temporal Variability in Surficial Seabed Character, Waipaoa River Margin, New Zealand. Master’s Thesis, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R.A.; Brooks, G.R.; Schwing, P.T.; Holmes, C.W.; Carter, S.R.; Hollander, D.J. High-Resolution Investigation of Event Driven Sedimentation: Northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Anthropocene 2018, 24, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.C.; Coale, K.H.; Edwards, B.D.; Marot, M.; Douglas, J.N.; Burton, E.J. Accumulation Rate and Mixing of Shelf Sediments in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Mar. Geol. 2002, 181, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouret, A. Biogéochimie Benthique: Processus Communs et Divergences Entre Les Sédiments Littoraux et Ceux Des Marges Continentales. Comparaison Entre Le Bassin d’Arcachon et Le Golfe de Gascogne. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Bordeaux 1, Bordeaux, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mouret, A.; Anschutz, P.; Lecroart, P.; Chaillou, G.; Hyacinthe, C.; Deborde, J.; Jorissen, F.J.; Deflandre, B.; Schmidt, S.; Jouanneau, J.-M. Benthic Geochemistry of Manganese in the Bay of Biscay, and Sediment Mass Accumulation Rate. Geo-Mar. Lett. 2009, 29, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, T.; Weber, O.; Anschutz, P.; Jorissen, F.; Jouanneau, J.-M. A Few Months-Old Storm-Generated Turbidite Deposited in the Capbreton Canyon (Bay of Biscay, SW France). Geo-Mar. Lett. 2001, 21, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, I.C.; Schwing, P.T.; Brooks, G.R.; Larson, R.A.; Hastings, D.W.; Ellis, G.; Goddard, E.A.; Hollander, D.J. Hydrocarbons in Deep-Sea Sediments Following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Blowout in the Northeast Gulf of Mexico. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; De Deckker, P.; Etcheber, H.; Caradec, S. Are the Murray Canyons Offshore Southern Australia Still Active for Sediment Transport? Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2010, 346, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.R. Examination of the 2011 Mississippi River Flood Deposit on the Louisiana Continental Shelf. Master’s Thesis, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).