Effects of Mesoscale Eddies on Acoustic Propagation with Preliminary Analysis of Topographic Influences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Ocean Mesoscale Eddy and Acoustic Field Calculation Models

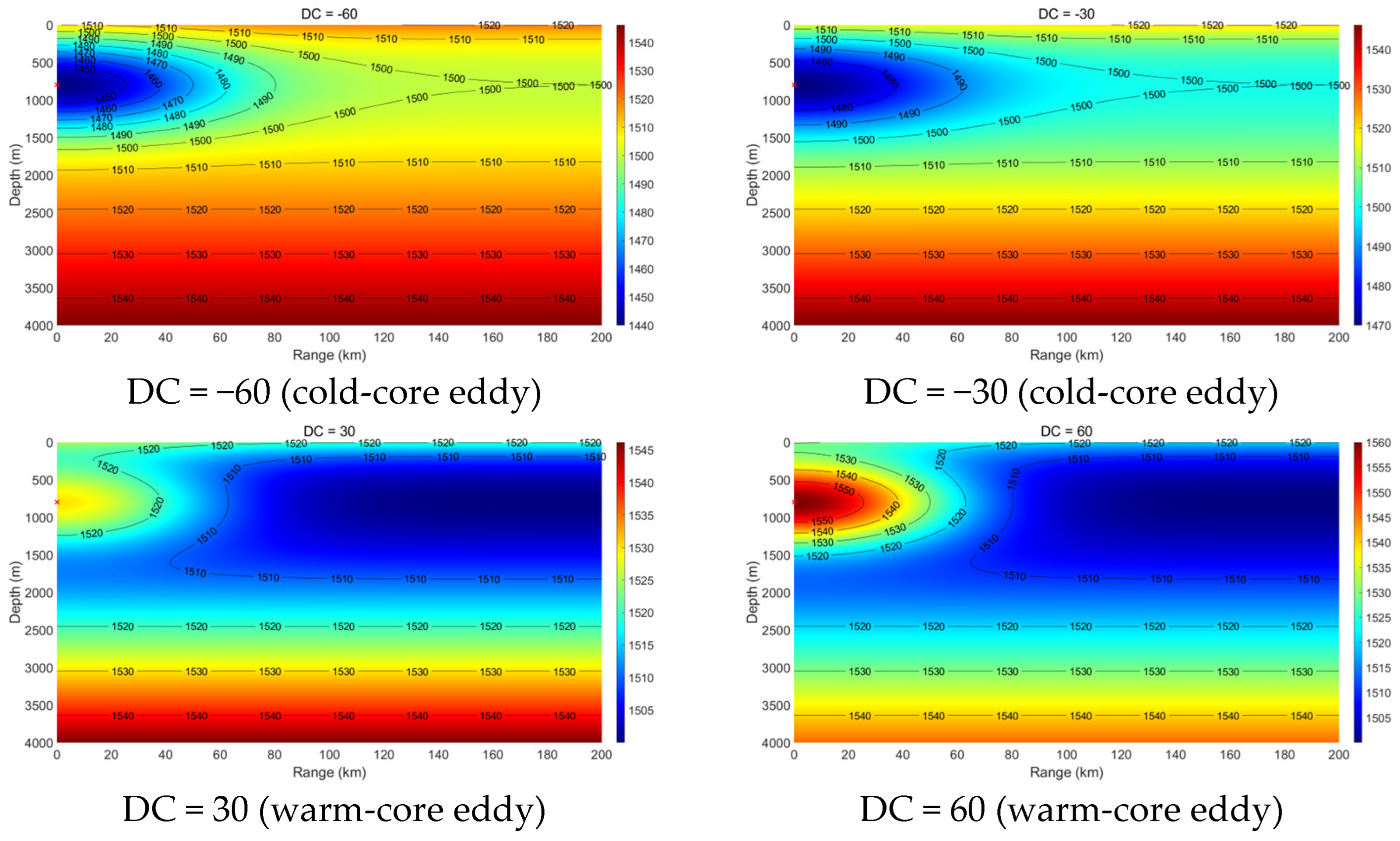

2.1. Ocean Mesoscale Eddy Model

2.2. Acoustic Field Calculation Model

3. Study on the Influence of Mesoscale Eddies on Sound Propagation in the Ocean

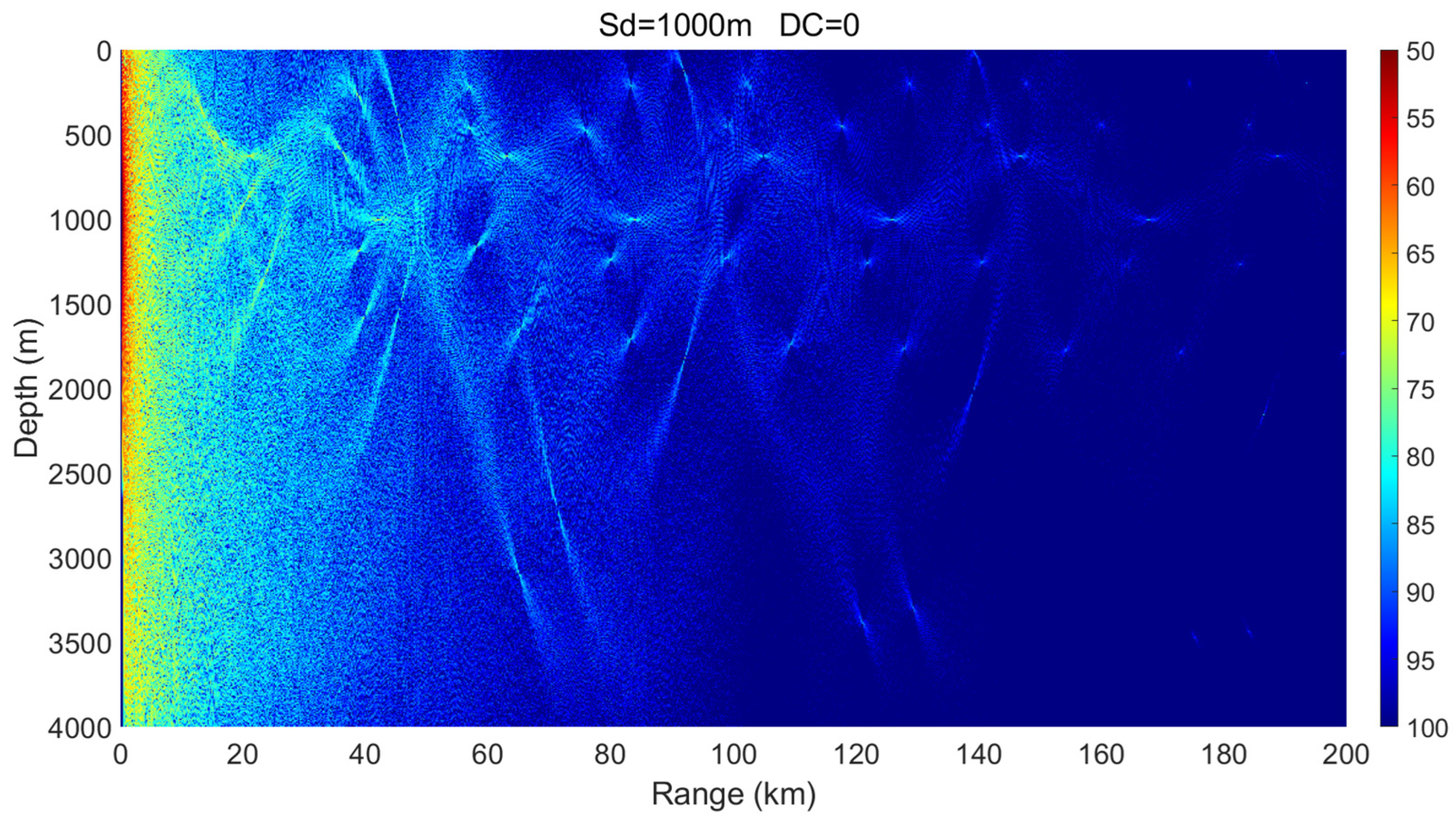

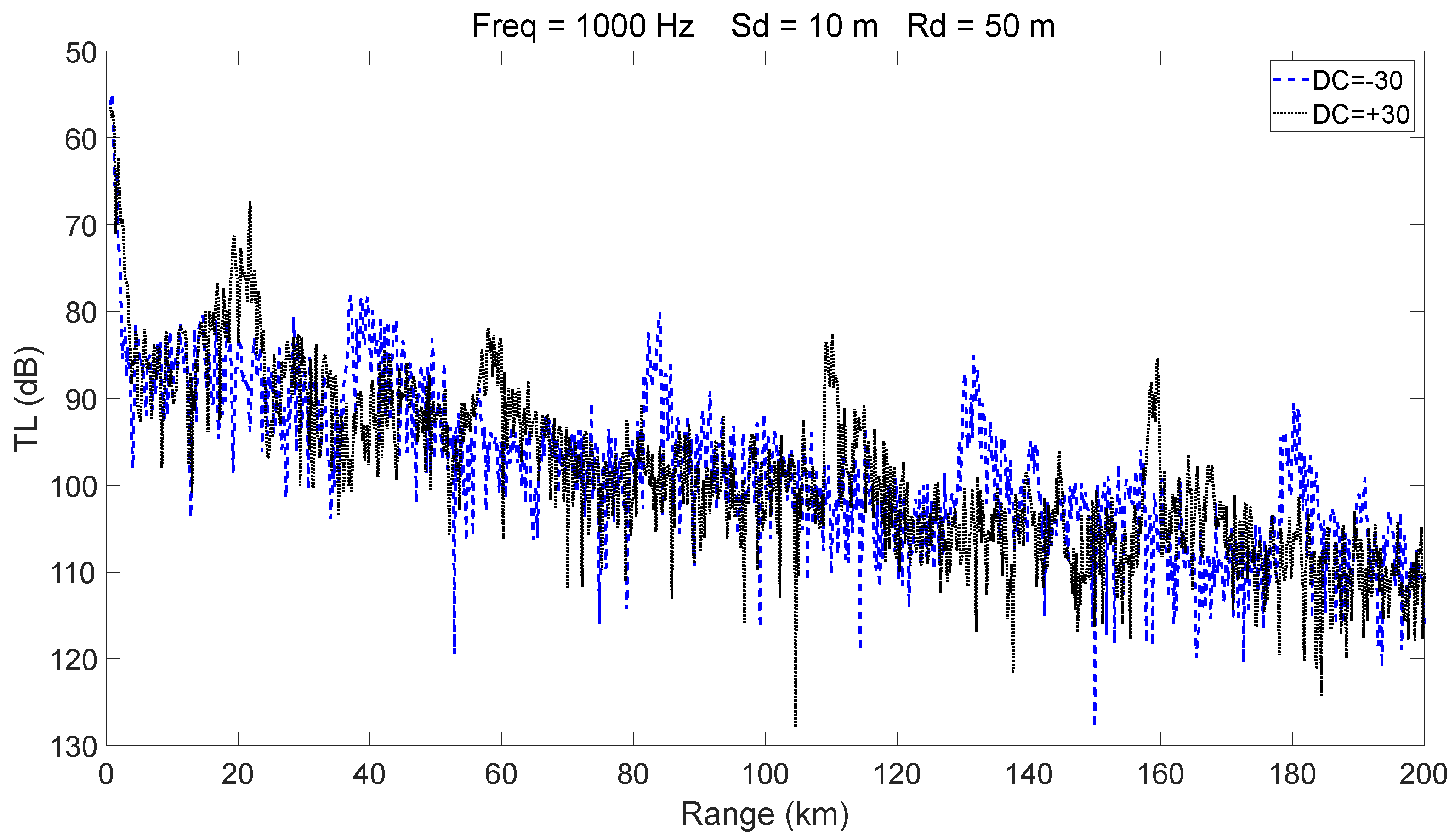

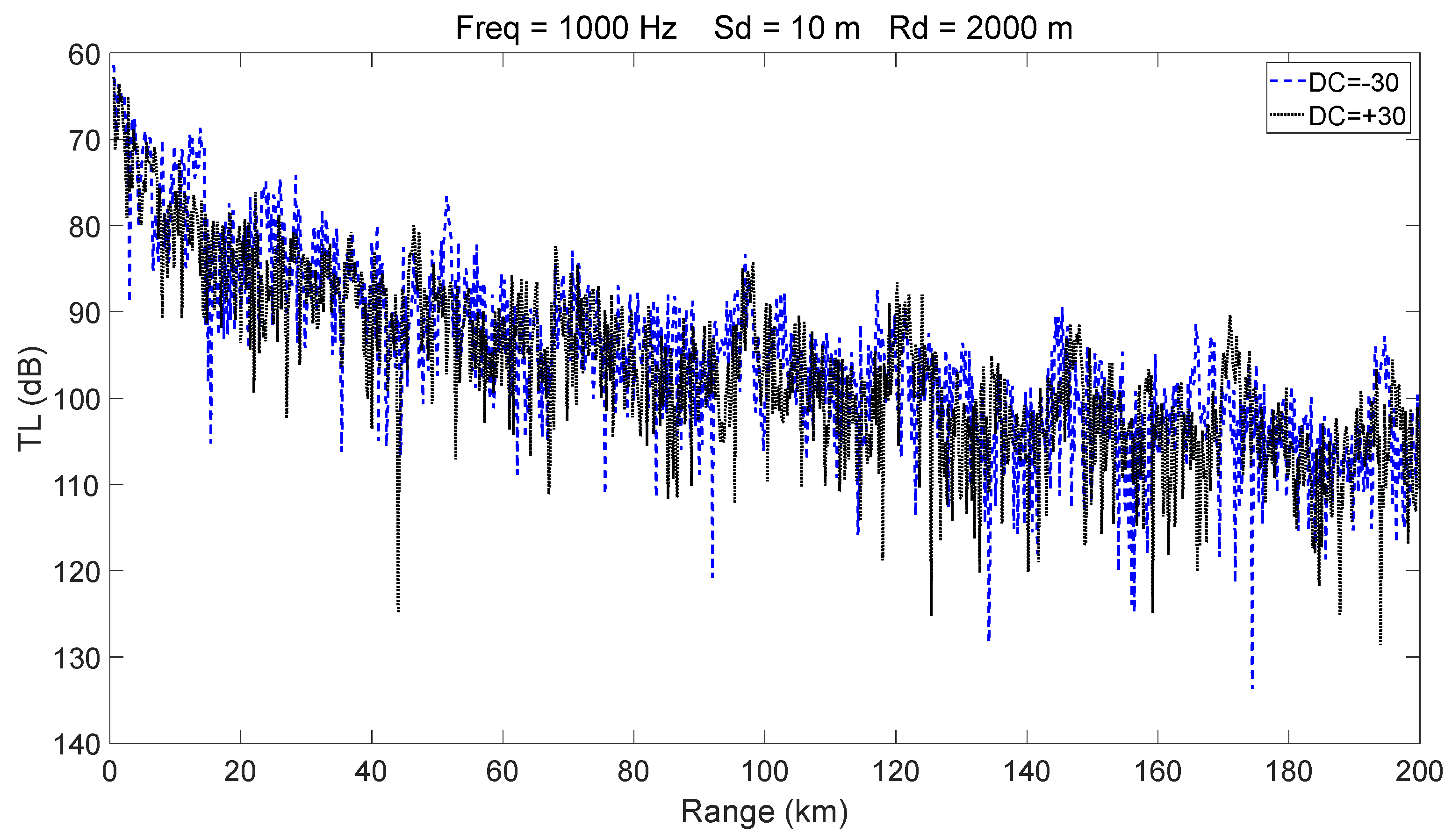

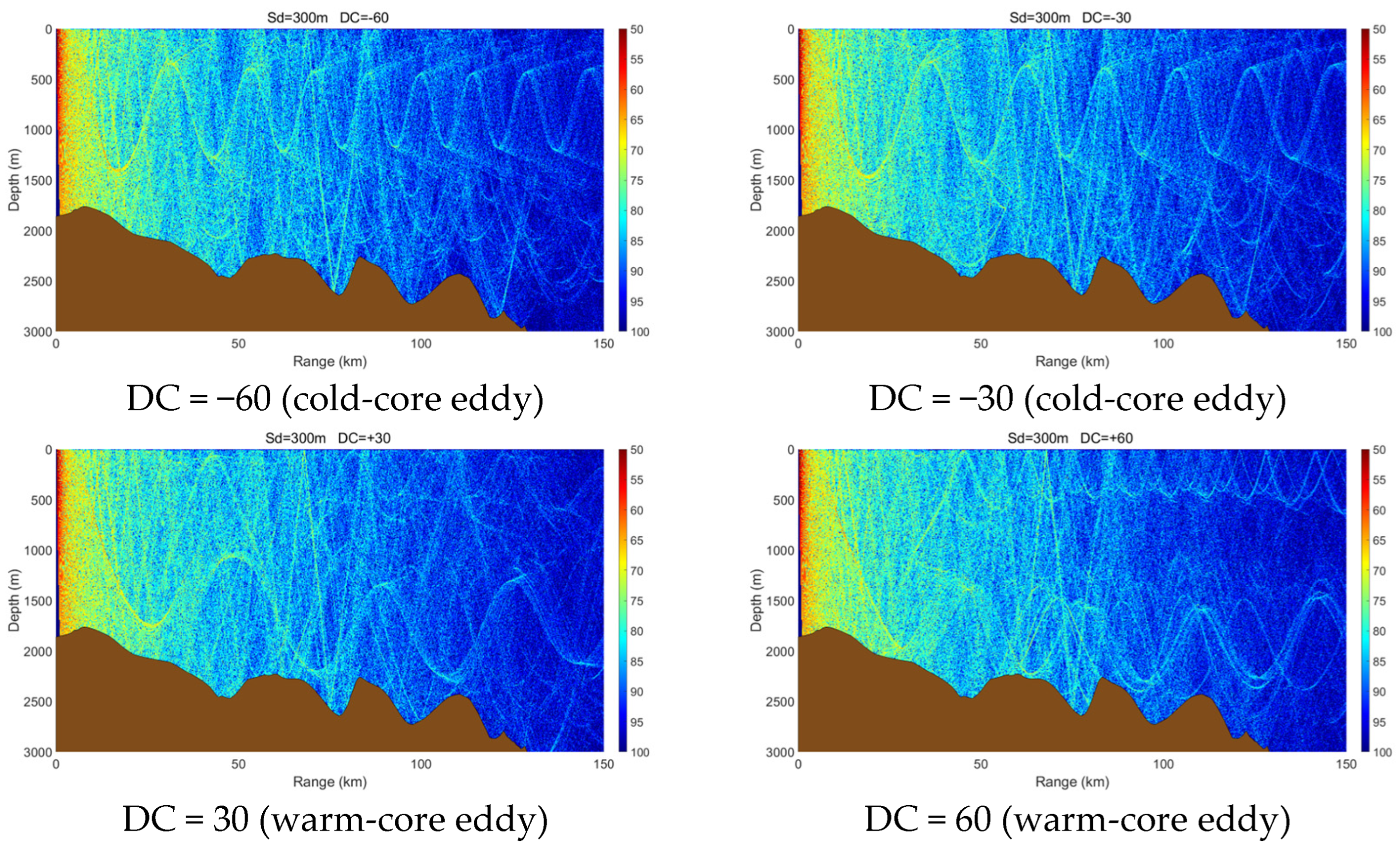

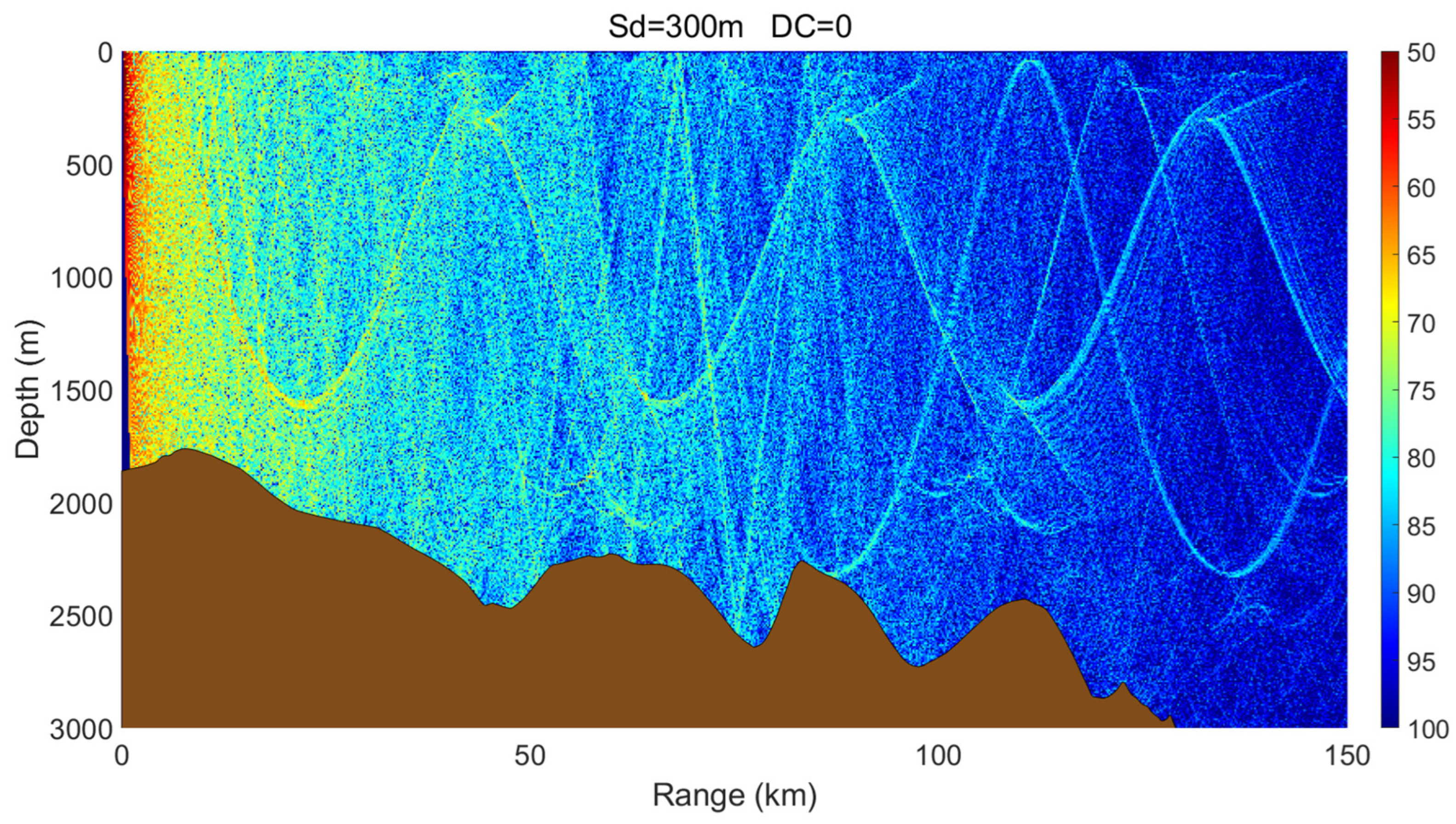

3.1. Sound Source Located Outside an Eddy

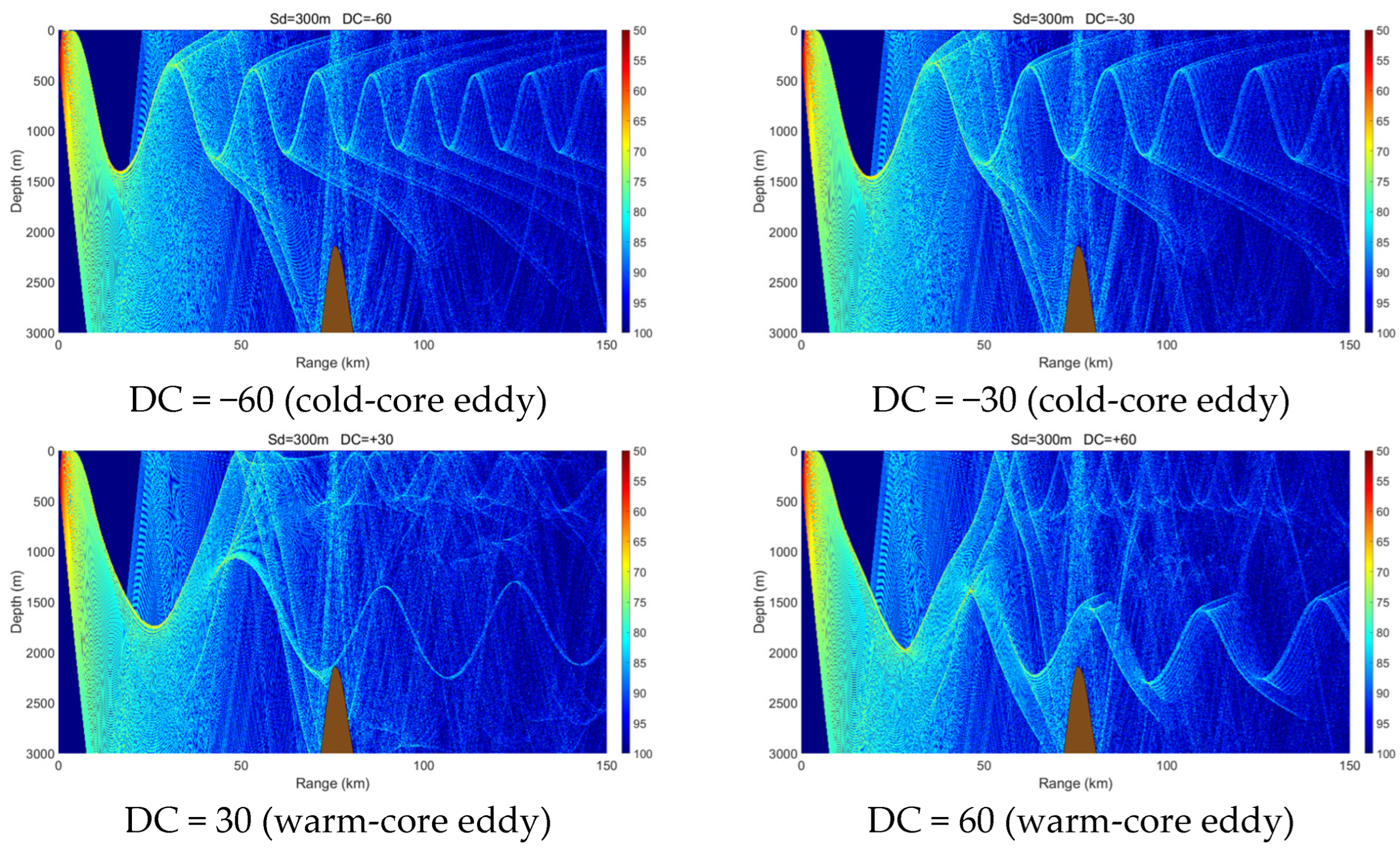

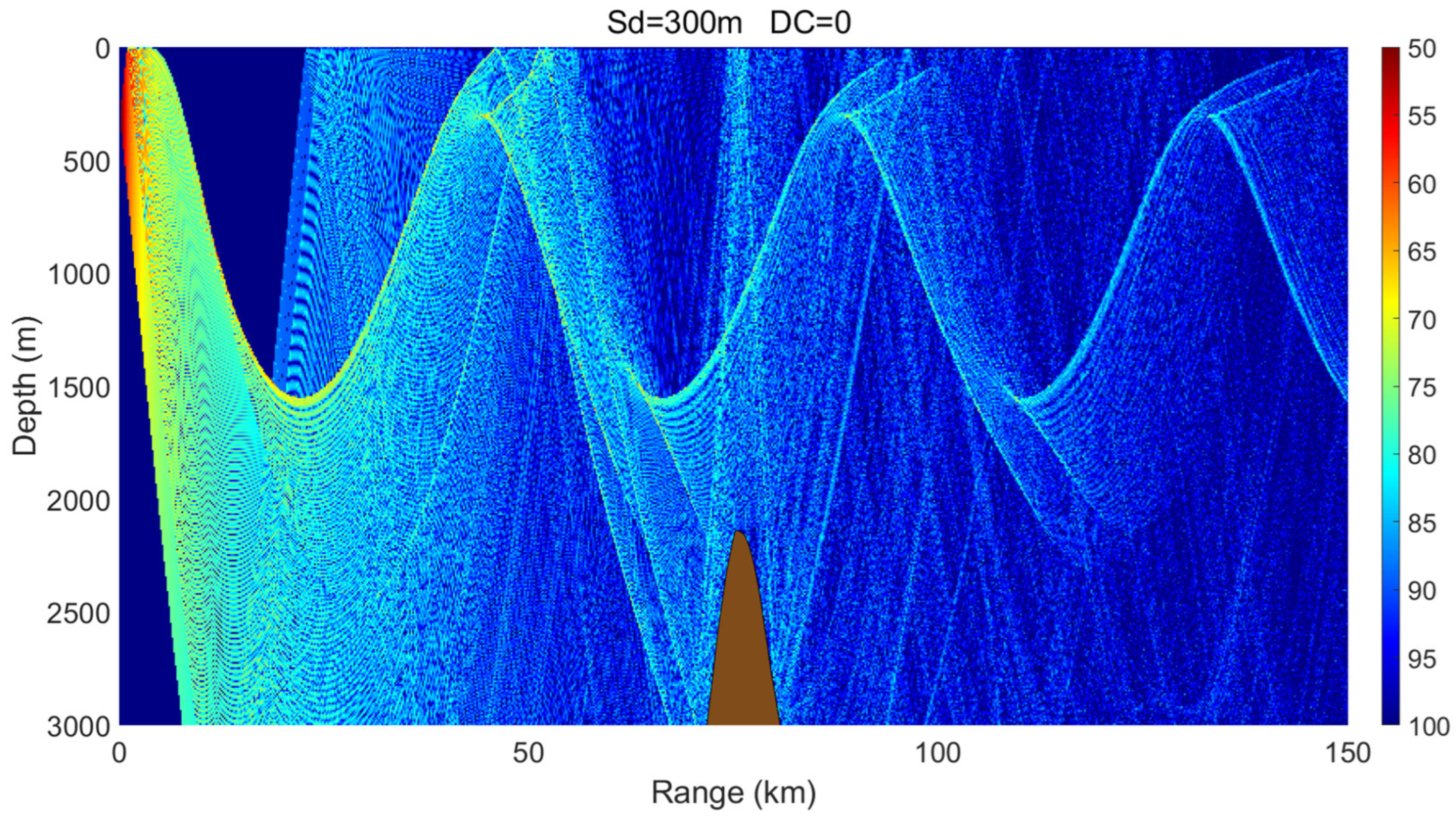

3.2. Sound Source Located at the Eddy Center

3.3. Effects of Variable Seabed Topography

3.3.1. Up-Slope Propagation

3.3.2. Down-Slope Propagation

3.3.3. Seamount-Affected Propagation

4. Conclusions

- Mesoscale eddies alter the vertical sound speed distribution, and such alterations—particularly when modifying sound channel properties such as the surface channel or the deep sound channel—can lead to significant changes in acoustic propagation behavior. Warm-core and cold-core eddies exhibit distinctly different propagation mechanisms.

- Within a certain depth range, cold-core eddies shift the convergence zone forward, reduce its width, and elevate its depth, whereas warm-core eddies displace it backward and broaden its width. The magnitude of these effects is positively correlated with eddy intensity.

- The presence of a warm-core eddy in the convergence region weakens the convergence gain and leads to noticeable convergence zone splitting beyond a certain range. In contrast, a cold-core eddy enhances the convergence gain under the same conditions.

- Under warm-core eddy conditions, influenced by variations in both source depth and seawater depth, a surface duct structure analogous to the deep-water sound channel axis may form. This structure can effectively trap and guide acoustic energy with minimal leakage.

- A cold-core eddy behaves as an upward-focusing acoustic lens, refracting sound rays upward and concentrating acoustic energy in the upper ocean, which makes propagation relatively insensitive to seabed topography. In contrast, a warm-core eddy acts as a downward-focusing acoustic lens, enhancing downward refraction and increasing acoustic interaction with the seabed. As a result, its propagation characteristics are strongly modulated by seabed variations, exciting complex phenomena such as surface ducts, dual-channel propagation, or significant acoustic loss in different topographic settings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheney, R.E.; Winfrey, D.E. Distribution and Classification of Ocean Fronts; US Naval Oceanographic Office: Bay St. Louis, MS, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Etter, P.C. Underwater Acoustic Modeling and Simulation; Spon Press (Tay & Francis Group): London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, L.; Han, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, P.; Guo, W. Modulation of Deep-Sea Acoustic Field Interference Patterns by Mesoscale Eddies. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.N. Propagation through a three-dimensional eddy including effects on an array. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1981, 69, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, C.; Qiu, R.G. An analysis of acoustic propagation variability in a convergence zone influenced by a Western Pacific cold eddy. Mar. Sci. Bull. 2015, 34, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S.L.; Zhang, R.; Gao, F.; Hong, M.; Pan, Z.L.; Liu, K.F. Diagnosis of acoustic propagation characteristics in convergence zones of mesoscale cold eddies based on in-situ oceanographic survey data. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2016, 34, 523–531. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.Q.; Zhang, H.G.; Qu, K. Influence of mesoscale warm eddy on acoustic propagation in the northeastern South China Sea. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2021, 42, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, K. Observation of a mesoscale warm eddy impacts acoustic propagation in the slope of the South China Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1086799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S.; Qin, J.X.; Li, Z.L.; Wu, S.; Wang, M.; Li, W.; Guo, Y. Warm-core eddy effects on sound propagation in the South China sea. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 211, 109551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, M.A.; Petrov, P.S.; Kaplunenko, D.D.; Golov, A.A.; Morgunov, Y.N. Predicting Effective Propagation Velocities of Acoustic Signals using an Ocean Circulation Model. Acoust. Phys. 2021, 67, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, M.; Petrov, P.; Budyansky, M.; Fayman, P.; Didov, A.; Golov, A.; Morgunov, Y. On the Effect of Horizontal Refraction Caused by an Anticyclonic Eddy in the Case of Long-Range Sound Propagation in the Sea of Japan. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, W.; Sun, D.; Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Tian, K. Research on High-Precision Long-Range Positioning Technology in the Deep Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yu, Y. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Sonar Detection Range in Luzon Strait. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.N. Calculations of sound propagation through an eddy. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1980, 67, 1180–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrick, R.F. General analysis of ocean eddy effects for sound transmission application. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1977, 62, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, M.; Gudimenko, A.; Luchin, V.; Tyschenko, A.; Petrov, P. The Parameterization of the Sound Speed Profile in the Sea of Japan and Its Perturbation Caused by a Synoptic Eddy. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.B. Gaussian beam tracing for computing ocean acoustic fields. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1987, 82, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucker, H.P. A simple 3-D Gaussian beam sound propagation model for shallow water. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998, 95, 2437–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, H.; Keenan, R.E. Gaussian ray bundles for modeling high-frequency propagation loss under shallow-water conditions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1996, 100, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.D.; Lei, B.; Lu, Y.Y. Principles and Applications of Typical Acoustic Field Models in Marine Acoustics; Northwestern Polytechnical University Press: Xi’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Urick, R.; Kuperman, W.A. Sound Propagation in the Sea. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1989, 86, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F.B.; Kuperman, W.A.; Porter, M.B.; Schmidt, H. Computational Ocean Acoustics (13.853). Comput. Phys. 2003, 9, 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.H.F.; Sandwell, D.T. Global Sea Floor Topography from Satellite Altimetry and Ship Depth Soundings. Science 1997, 277, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soong, Y.S.; Hu, J.H.; Ho, C.R.; Niiler, P.P. Cold-Core Eddy Detected in South China Sea; Eos Transactions American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Nowlin, W.D.; Jilan, S. Anticyclonic rings from the Kuroshio in the South China Sea. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1998, 45, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEBCO Compilation Group. GEBCO_2020 Grid. 2020. Available online: https://www.gebco.net/data-products/gridded-bathymetry-data/gebco-2020 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Lou, C.; Jia, Y.; Yang, K.; Yu, X. Effects of Mesoscale Eddies on Acoustic Propagation with Preliminary Analysis of Topographic Influences. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2390. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122390

Zhang X, Lou C, Jia Y, Yang K, Yu X. Effects of Mesoscale Eddies on Acoustic Propagation with Preliminary Analysis of Topographic Influences. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2390. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122390

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xueqin, Cheng Lou, Yusheng Jia, Kunde Yang, and Xiaolin Yu. 2025. "Effects of Mesoscale Eddies on Acoustic Propagation with Preliminary Analysis of Topographic Influences" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2390. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122390

APA StyleZhang, X., Lou, C., Jia, Y., Yang, K., & Yu, X. (2025). Effects of Mesoscale Eddies on Acoustic Propagation with Preliminary Analysis of Topographic Influences. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2390. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122390