Abstract

Hypertension has traditionally been viewed as a hemodynamic disorder leading to cardiac and renal injury; however, growing evidence suggests that, in many individuals, elevated blood pressure is instead the earliest clinical expression of subtle cardiorenal dysfunction. Early abnormalities—such as low-grade albuminuria, increased renal resistive index, arterial stiffness, and masked or nocturnal hypertension—can appear before estimated glomerular filtration rate decline or elevated office blood pressure, indicating early impairment of pressure–natriuresis, heightened tissue renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) activity, and increased renal microvascular impedance. The aim of this review is to summarize mechanistic, clinical, and phenotypic evidence supporting the concept that hypertension functions as an early biomarker along the cardiorenal continuum. Incorporating vascular and renal biomarkers, ambulatory blood pressure phenotyping, and targeted laboratory indices into routine assessment may identify individuals transitioning from functional disturbances to structural organ damage. These abnormalities reflect a mechanistic triad of arterial stiffening, salt-sensitive RAAS activation, and circadian blood pressure disruption, collectively defining the early cardiorenal–hypertensive phenotype. Viewing hypertension through a cardiorenal lens underscores a critical opportunity for earlier detection and mechanism-oriented intervention, which may modify disease trajectory and prevent progression to overt chronic kidney disease and heart failure.

1. Introduction

Hypertension represents the most prevalent cardiovascular disorder, affecting approximately 30–40% of the adult population worldwide. Its multifactorial nature contributes to the complexity of its etiology, greatly increasing the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1]. Beyond its well-established cardiovascular implications, hypertension has a profound bidirectional relationship with renal disease, both contributing to the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and accelerating its progression [2].

Conversely, deterioration of renal function may adversely affect cardiac structure and function, establishing a bidirectional interaction known as cardiorenal syndrome. Although the bidirectional interaction between the heart and kidneys has long been recognized, the underlying mechanisms remain incompletely understood and are likely to have a composite pathogenesis [3].

Traditionally, hypertension has a pivotal role as a leading cause of both cardiovascular and renal damage. However, growing evidence challenges this unidirectional belief, suggesting instead that hypertension functions as a proximal clinical signature and a potent promoter of underlying cardiorenal dysfunction. While established cardiorenal syndrome is defined by overt renal or cardiac failure, hypertension—especially when associated with arterial stiffness and nocturnal patterns—may reflect the earliest detectable stage of systemic cardiorenal stress [4,5]. Subtle structural and functional changes considering the renal microcirculation, endothelium, and arterial wall often precede the overt rise in blood pressure, inevitably leading to a self-perpetuating cycle of renal sodium retention, sympathetic activation, and vascular stiffening [6].

Common pathophysiology pathways connecting the heart, vasculature and, kidneys characterize the cardiorenal continuum. Within this framework, hypertension should not be viewed solely as an intermediate step, but rather as an early sign of systemic cardiorenal stress. This concept has major implications for prevention and management, as early markers such as microalbuminuria, increased arterial stiffness, or altered renal resistive index may detect subclinical signs of cardiorenal dysfunction well before the onset of overt CKD or heart failure [7,8].

Despite advances in antihypertensive therapy, the global prevalence of hypertension continues to rise, exposing many individuals to increased cardiorenal risk. This observation underscores the need for a more personalized, mechanism-oriented approach that integrates vascular and renal biomarkers may help better contextualize blood pressure elevation within the broader cardiorenal continuum, rather than viewing hypertension solely as isolated hemodynamic stress [9,10].

This review aims to integrate mechanistic insights and clinical evidence to contextualize hypertension within the early stages of the cardiorenal continuum, emphasizing arterial stiffness, salt sensitivity, and ambulatory blood pressure phenotypes as key modifiers of cardiovascular and renal risk.

2. Arterial Stiffness and Renal Function

The role of arterial remodeling and arterial stiffness (AS) as independent cardiovascular risk factors and predictors of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality is revealed by multiple epidemiological and clinical studies [11].

The arterial pressure response to changes in stroke volume is reflected by AS. During ventricular systole, part of the ejected stroke volume is transiently stored within the aorta and central elastic arteries, causing distention of their walls and a corresponding rise in blood pressure (BP). This mechanism allows the arteries to act as a buffer, modulating the pulsatile output of the heart. In this context, increased arterial stiffening precedes the development of hypertension by leading to higher systolic pressures, augmented pulse pressure, and greater cardiac workload [12,13].

Carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity (cfPWV) remains the traditional, gold standard method for noninvasive measurement of arterial stiffness, assessing directly aortic and central elastic artery properties. Brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV), an alternative measurement tool, incorporates the peripheral or muscular arteries, offering greater simplicity, automation, and feasibility for large-scale population studies [4,11]. In practice, cfPWV ≥ 10 m/s or baPWV ≥ 18 m/s indicate high cardiovascular risk, whereas intermediate values represent progressive arterial stiffening and escalating left-ventricular afterload. Both indices correlate strongly with hypertensive complications and cardiovascular risk, including kidney disease [4,14]. Even though some studies suggest that baPWV may predict cardiovascular risk similar to cfPWV, the lack of standardization in measurement methods, and clinical application, and a shortage of large prospective studies emerge the need for further research [11,14].

AS represents a systemic disease characterized by structural and functional vessel wall changes resulting from endothelial dysfunction and remodeling of the tunica media and is followed by a reduction in arterial compliance, especially the aorta that has the greatest elastin content within the arterial system [4,15]. A series of events contribute to the pathophysiology of the disease including not only the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), but also inflammation, calcification, elastin crosslinking, and the accumulation of collagens [15]. Endothelial dysfunction, is characterized by a proinflammatory state with reduced vasodilatory capacity and prothrombotic properties, and is caused mainly by the absence of nitric oxide (NO) which causes vasodilation, and the increased generation of vasoconstrictive substances [12,15]. These factors further contribute to greater stiffness and a downward spiral, leading to end-organ damage [15]. Excessive pulsatile energy increases left ventricular (LV) afterload and promotes the adverse myocardial remodeling towards hypertrophy and fibrosis and, additionally its transmission from the macro- to the microcirculation, as a result of the preferential stiffening of the aorta, promotes microvascular damage in peripheral organs and tissues [4,16]. AS often progresses with age, causing fundamental hemodynamic alterations, significantly contributing to heart and kidney failure, cognitive decline, and other serious end-organ damage [4,15]. Taken together, these vascular abnormalities provide the mechanistic link between arterial remodeling and the early renal microvascular injury characteristic of the initial stages of the cardiorenal continuum [4,15,17].

While arterial stiffness has long been recognized as a key determinant of ventricular–vascular coupling, its impact extends to the microcirculation—particularly within the kidney, which, owing to its high perfusion and low-resistance circulation, is particularly vulnerable to pulsatile stress [16,18]. Preferential stiffening of central elastic arteries increases the transmission of pulsatile pressure and flow to the renal microvasculature, overwhelming its autoregulatory capacity. This macro-to-micro energy transfer initiates endothelial injury, glomerular hypertension, and subsequent nephron loss resulting in renal dysfunction [16,18,19].

This mechanical insult promotes mesangial expansion, afferent arteriolar thickening, and downstream ischemic changes in the renal medulla. Over time, such microvascular remodeling contributes to sodium retention and impaired pressure-natriuresis, reinforcing systemic blood pressure elevation—a vicious cycle characteristic of the early cardiorenal phenotype [20].

Clinical data consistently demonstrate that measures of AS, such as cfPWV and augmentation index, independently predict both the onset and progression of CKD. Additionally, individuals with isolated systolic hypertension or elevated central pulse pressure exhibit higher urinary albumin excretion and reduced estimated GFR long before overt renal disease becomes evident. These findings support the concept that arterial stiffness is not merely a consequence of aging or hypertension but also an initiating factor in renal microvascular injury [21,22,23].

At the same time, the kidney contributes to systemic vascular stiffening through volume overload, uremic toxin accumulation, and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) [24]. The bidirectional reinforcement between arterial stiffness and renal dysfunction thus establishes the “arterial–renal loop”—a self-perpetuating pathophysiological substrate upon which hypertension emerges as the earliest detectable expression of cardiorenal damage [8,18,19].

Beyond being a consequence of aging or hypertension, arterial stiffness may act as an early upstream driver of cardiorenal dysfunction. By increasing pulsatile pressure transmission to the renal microcirculation, central arterial stiffening promotes glomerular hypertension, microvascular injury, and impaired pressure–natriuresis, even in the absence of overt renal disease [19,21]. In this context, arterial stiffness represents a key mechanistic link through which vascular alterations precede and amplify renal vulnerability along the cardiorenal continuum [18,19].

From a clinical and translational perspective, recognizing arterial stiffness and early cardiorenal vulnerability provides an opportunity for intervention before irreversible structural damage develops [25]. Mechanism-oriented strategies that target underlying mechanisms–such as vascular stiffness, sodium handling, and neurohormonal activation-including lifestyle measures, sodium restriction, RAAS blockade, chronotherapy, and sodium-glucose co-transporters 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, may attenuate the self-perpetuating vascular–renal feedback loop [25,26]. Importantly, the potential benefit of these interventions extends beyond simple blood pressure lowering, as they may reduce pulsatile vascular stress and help preserve renal microvascular integrity at an early stage [26].

3. Salt Sensitivity and Tissue Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System

Salt sensitivity, defined as the excessive rise in blood pressure in response to dietary sodium intake, is increasingly recognized as a defining feature of early cardiorenal dysfunction. Normally, the healthy kidney maintains sodium balance and hemodynamic stability by recruiting adaptive mechanisms such as pressure natriuresis and nitric oxide–mediated vasodilation [25,26].

However, these homeostatic responses become blunted when renal microvascular integrity is compromised and leading to sodium retention, volume expansion, and a heightened pressor response. Beyond its hemodynamic dimension, salt sensitivity reflects a complex interaction between vascular, inflammatory, and neurohormonal pathways centered around the kidney [26,27].

Salt loading promotes both extracellular volume expansion and activation of tissue RAAS within the kidney, vasculature, and myocardium [24]. This tissue RAAS acts as a critical regulator of blood volume, electrolyte balance, and systemic vascular resistance, mediating both acute and chronic physiological responses. Operating independently from systemic renin activity, it amplifies the expression of profibrotic mediators such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and connective tissue growth factor, while oxidative stress and inflammation promote vascular stiffening, perivascular fibrosis, and glomerulosclerosis—all key features of subclinical cardiorenal injury [24,27,28].

Clinical evidence supports this paradigm. Individuals of salt-sensitive phenotypes often present with inappropriately elevated aldosterone levels, increased sympathetic tone, and microalbuminuria despite preserved glomerular filtration [29]. These patients exhibit a hemodynamic profile characterized by low-renin hypertension, expanded extracellular volume, and impaired nocturnal pressure dipping [29,30]. Collectively, these features reveal early renal and cardiac dysfunction, and are frequently associated with CKD and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [30,31]. Considering this context, salt sensitivity may serve as an early biomarker of systemic cardiorenal dysregulation [29].

Furthermore, tissue RAAS activation amplifies this process by enhancing sodium reabsorption, vascular remodeling, and myocardial stiffness. Angiotensin II and aldosterone exert direct effects on podocytes, mesangial cells, and cardiomyocytes, promoting collagen deposition and inflammatory signaling [29]. Even in normotensive individuals, these molecular events contribute to diastolic dysfunction, interstitial fibrosis, and progressive nephron loss, gradually manifesting as clinical features of the cardiorenal continuum [29,31].

Therapeutically, inhibition of RAAS overactivation remains a cornerstone, with well-established benefits. By modulating vascular tone, sodium retention, and water balance, RAAS plays a pivotal role in the development of hypertension, heart failure, and various cardiorenal disorders. These insights reinforce the rationale for early RAAS blockade and cautious sodium restriction in patients with high cardiorenal susceptibility, such as those with albuminuria, metabolic syndrome, or family history of hypertension [29]. Emerging data suggest that SGLT2 inhibitors and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) exert pleiotropic renal and cardiovascular effects that extend beyond blood pressure lowering, including modulation of sodium handling, intrarenal hemodynamics, and downstream consequences of RAAS overactivation [32,33]. Clinical suspicion of salt sensitivity, based on surrogate markers such as urinary sodium handling, aldosterone-to-renin patterns, and blood pressure response to dietary sodium intake, may support a more personalized, pathophysiology-driven management approach [26,34].

Overall, multiple biochemical and molecular mechanisms constitute the pathophysiological background of the hypertensive cardiorenal phenotype, mainly represented by salt sensitivity and local RAAS activation. Subtle renal microvascular dysfunction evolves into sustained systemic hypertension, ultimately resulting in vascular and myocardial remodeling. Early recognition of these mechanisms offers the opportunity for targeted intervention during a potentially reversible stage—long before hypertension evolves into overt cardiorenal syndrome [25,35].

From a clinical perspective, salt sensitivity may be clinically suspected in individuals with hypertension characterized by a disproportionate blood pressure response to dietary sodium intake, low-renin profiles, or prominent nocturnal and non-dipping blood pressure patterns. The presence of low-grade albuminuria, subtle volume expansion, or increased arterial stiffness despite preserved renal function may further support a salt-sensitive phenotype. Although direct assessment remains challenging in routine practice, the integration of these clinical and hemodynamic features can raise awareness of underlying salt-sensitive mechanisms early along the cardiorenal continuum [29,34].

4. Masked and Nocturnal Hypertension as a Hidden Cardiorenal Syndrome Signals

Among the most overlooked signs of early cardiorenal dysfunction are masked and nocturnal hypertension. These conditions describe BP patterns that appear normal in the clinic yet remain elevated in daily life or during the night, and frequently escape routine clinical detection as they are only detectable through out-of-office or nighttime measurements [36,37]. Unlike benign variants of hypertension, both represent underlying systemic stress on the heart and kidneys, reflecting a bidirectional interaction, and representing the earliest hemodynamic signature of systemic cardiorenal continuum [38,39].

The term ‘masked hypertension’ was introduced in the early 2000s to describe a difficult to diagnose hypertension phenotype affecting approximately 10–20% of adults, characterized by a discrepancy between normal office BP and elevated out-of-office BP measurements. Masked hypertension refers to untreated individuals, while masked uncontrolled hypertension refers to individuals treated for hypertension [38,40]. Both phenotypes reflect specific BP variability patterns and require confirmation through repeated, standardized office and out-of-office BP evaluations. The diagnosis is established when clinic BP values are normal but elevated via home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). The definitive diagnosis requires confirmation with repeated standardized office and out-of-office BP evaluations [38].

Nocturnal hypertension, a significant but underdiagnosed entity is characterized by persistently high BP during the night, affecting 6–20% of the population globally. Its detection typically involves 24-hour ABPM, the most reliable method to identify abnormal nocturnal BP profiles such as non-dipping and reverse-dipping that increase cardiovascular risk [39].

Both hypertension phenotypes share common pathophysiological pathways including sympathetic overactivity, endothelial dysfunction, increased arterial stiffness, and impaired renal sodium handling. All these components reflect early vascular and renal dysregulation [40,41]. Sustained sympathetic activation and impaired baroreflex sensitivity increase peripheral resistance and blunt nocturnal vasodilation, while subtle renal microvascular injury promotes sodium retention and volume expansion [41,42]. Masked hypertension is predominantly daytime and stress-related, while nocturnal hypertension results from disrupted circadian control and renal dysfunction [40,42]. Despite these differences in time, both phenotypes expose the microcirculation to continuous hemodynamic stress and serve as subclinical markers of the cardiorenal continuum [41,42].

Recognizing these patterns has profound diagnostic and therapeutic implications especially for the evaluation of individuals with high cardiorenal risk. The detection of masked or nocturnal hypertension warrants a broader work-up in order to uncover concurrent subclinical damage including assessment of albuminuria, renal resistive index (RRI), and arterial stiffness [39,43]. Therapeutically, except for lifestyle modifications, pharmacological management and timing is also important. Bedtime administration of antihypertensive agents, defined as chronotherapy, has shown to restore nocturnal dipping and improve renal outcomes in certain populations [44,45]. Additionally, among the agents that target sodium balance, evening diuretic dosing, reduction in dietary sodium, and use of SGLT2 inhibitors could correct the underlying cardiorenal mechanisms that conclude in nocturnal BP elevation [41,45].

In summary, masked and nocturnal hypertension should not be regarded as diagnostic curiosities but as the hemodynamic manifestation of preclinical cardiorenal dysfunction. Their recognition represents an opportunity for early intervention—one that may prevent the transition from functional vascular–renal abnormalities to irreversible structural disease [46].

5. Early Clinical Recognition of the Cardiorenal-Hypertensive Phenotype

Early cardiorenal dysfunction manifests long before overt CKD or structural heart disease develops. In clinical practice, subtle abnormalities such as low-grade albuminuria, mildly elevated RRI, increased AS, and central BP augmentation—along with elevated nighttime or ambulatory BP values—could signal early cardiorenal vulnerability [47,48]. In this context, hypertension should be viewed not as a standalone marker of established syndrome, but as a hemodynamic manifestation of incipient vascular and renal stress. This phenotype identifies individuals at high risk for transitioning from functional disturbances to irreversible structural organ damage [49].These findings often coexist with mechanisms characterizing “primary” hypertension, including altered pressure–natriuresis, reduced renal perfusion reserve, and heightened RAAS or sympathetic activity [48,49].

Importantly, many of these disturbances occur in individuals with normal office BP and preserved eGFR, highlighting the limitations of conventional diagnostic thresholds in detecting early disease. The presence of masked or nocturnal hypertension, for instance, may reveal subclinical vascular and renal stress well before structural remodeling becomes evident [40,50]. Likewise, early albuminuria, subtle increases in RRI, or central hemodynamic alterations can reflect renal microvascular injury at a still reversible stage [48,51].

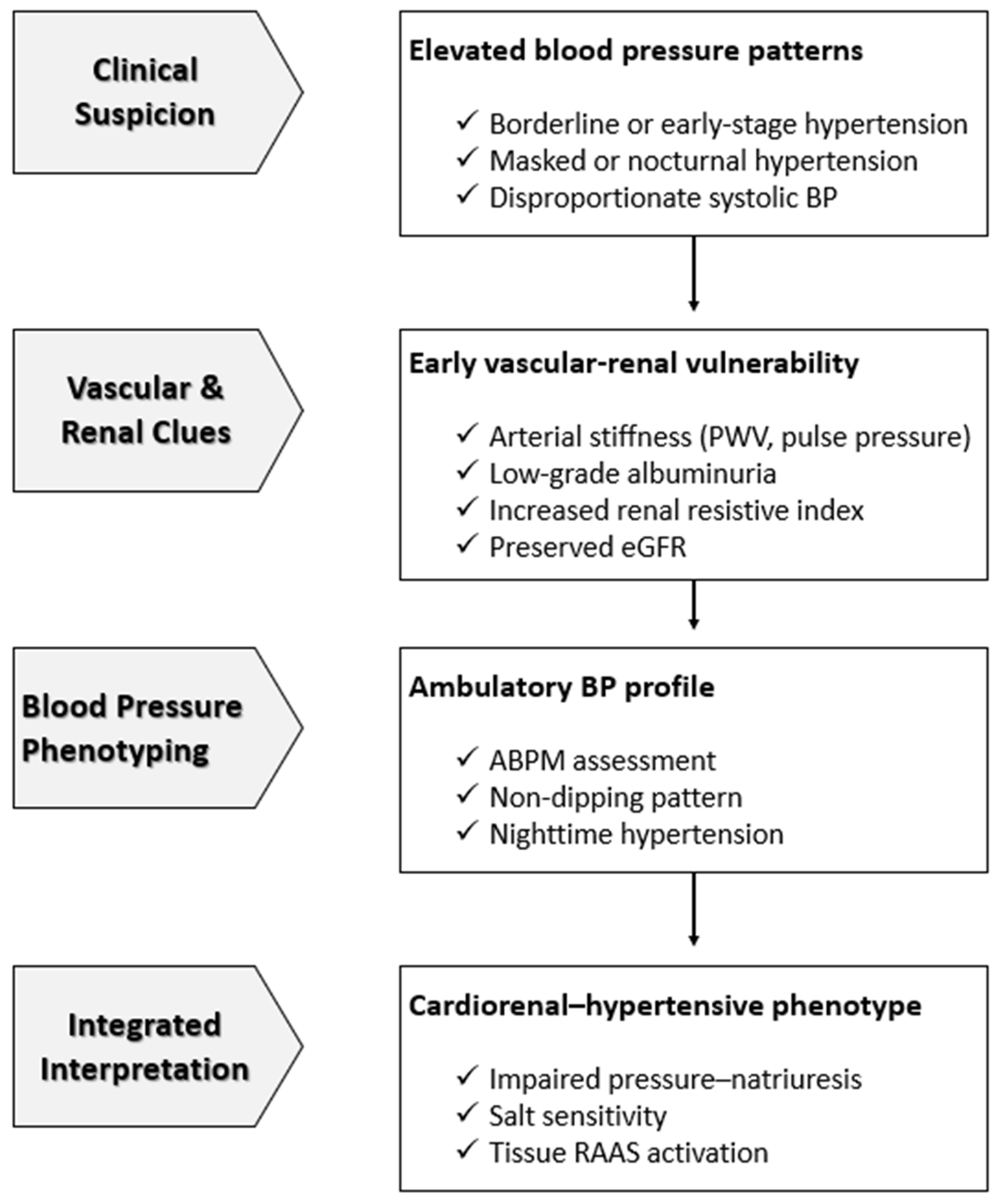

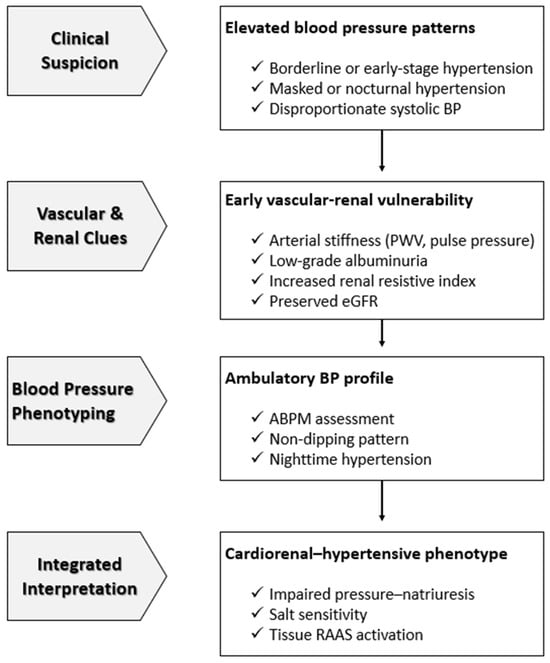

ABPM, home BP monitoring, PWV measurements, and selective use of renal biomarkers could detect these early markers and refine the identification of high-risk individuals across the cardiorenal continuum. Recognizing these early abnormalities provides the chance for targeted, mechanism-oriented intervention that could prevent the progression from functional disturbances to irreversible kidney and heart disease [49,52]. A simplified clinical framework for early recognition of this phenotype is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Early Clinical Recognition of the Cardiorenal–Hypertensive Phenotype. This figure illustrates a simplified, clinically oriented framework for the early identification of cardiorenal vulnerability in individuals with elevated or borderline blood pressure. Initial clinical suspicion based on abnormal blood pressure patterns prompts evaluation of vascular stiffness, renal microvascular signals, and ambulatory blood pressure phenotypes, frequently in the presence of preserved estimated glomerular filtration rate. The integration of these findings allows recognition of a cardiorenal–hypertensive phenotype characterized by salt sensitivity, impaired pressure–natriuresis, and tissue renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system activation, enabling early, mechanism-oriented intervention before overt chronic kidney disease or heart failure develops. Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; PWV, pulse wave velocity; RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system.

6. Age, Obesity and Diabetes as Modifying Factors in Early Cardiorenal–Hypertensive Phenotypes

Age represents a critical modifier of the cardiorenal–hypertensive phenotype and should be carefully considered when interpreting hypertension as an early clinical expression of cardiorenal dysfunction. Advancing age is associated with progressive arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction, and reduced vascular compliance, leading to increased systolic blood pressure, widened pulse pressure, and enhanced transmission of pulsatile energy to the renal microcirculation [12]. In parallel, age-related changes in renal autoregulation, gradual nephron loss, and microvascular rarefaction increase susceptibility to glomerular hypertension, sodium retention, and impaired pressure–natriuresis. These alterations may develop before overt declines in estimated glomerular filtration rate and may contribute to the development of masked or nocturnal hypertension, particularly in older individuals [5,12]. Importantly, aging itself should not be equated with pathological cardiorenal disease; rather, it modulates the threshold at which adaptive vascular and renal changes become maladaptive. Consequently, the interpretation of elevated blood pressure as an early marker along the cardiorenal continuum should be contextualized within age-specific vascular and renal vulnerability, reinforcing the need for personalized risk stratification rather than age diagnostic approach [9,10].

Beyond age, common metabolic conditions such as obesity and type 2 diabetes further contribute to the cardiorenal–hypertensive phenotype by amplifying arterial stiffness, promoting renal sodium retention, and enhancing tissue RAAS activity. These metabolic conditions increase vulnerability to salt sensitivity, masked hypertension, and early microvascular dysfunction, thereby influencing how elevated blood pressure should be interpreted within the cardiorenal continuum and reinforcing the need for individualized risk assessment [22,29,53].

7. Clinical and Translational Implications

The growing recognition of hypertension as the first clinical expression of early cardiorenal dysfunction has profound diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Rather than being solely a hemodynamic disorder, elevated blood pressure represents a heterogeneous phenotype combining vascular, renal, and neurohormonal abnormalities. Identifying these early abnormalities is essential to prevent the transition from functional cardiorenal dysregulation to irreversible structural disease [6,10]. This concept underlines the need for identifying these early abnormalities beyond office blood pressure values, incorporating vascular and renal biomarkers, as well as hypertension phenotypes, to evaluate individuals in whom hypertension signifies preclinical organ injury [10].

From a diagnostic standpoint, biochemical derangements may reveal hemodynamic consequences of hypertension [10]. Integrating microalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), elevated RRI which suggests increased renovascular impedance, and PWV into hypertension assessment may reveal subtle signs of systemic vascular–renal coupling [8,48]. Additionally, advanced renal biomarkers such as cystatin C, NGAL, and KIM-1 can detect early kidney stress before overt GFR loss, enhancing diagnostic sensitivity before structural disease becomes evident [54]. Tissue sodium accumulation detectable by ^23Na-MRI, although not yet used clinically, may also evolve into a powerful imaging biomarker of early cardiorenal pathology [55]. From a metabolic perspective, SSBP is often accompanied by insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, which further elevate cardiovascular risk [53].

This multimodal strategy supports the modern shift for mechanism-driven risk assessment, combining clinical, molecular, and imaging data to sharpen prognosis and guide targeted therapy [9]. Therapeutically, the need for early and aggressive mechanism-based interventions in high-risk patients is underscored, emphasizing RAAS blockade, sodium restriction, and restoration of circadian BP patterns [10,56]. Novel pharmacologic agents including SGLT2 inhibitors, nonsteroidal MRAs, and potentially angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI)-based regimens exhibit pleiotropic vascular and renal benefits beyond blood pressure reduction [33,57,58].

The emerging role of chronotherapy is equally important—individualizing the timing of antihypertensive treatment to align with circadian rhythms and reduce nocturnal BP [44].

Incorporating these insights into clinical practice redefines hypertension classification requiring a paradigm shift toward precision hypertension management, where blood pressure is interpreted as a dynamic biomarker of vascular health rather than an isolated vital sign. Identifying patients in the transition from functional to structural organ damage offers the opportunity for intervention while the process remains potentially reversible [9,59].

8. Mechanistic Pathways Driving the Early Cardiorenal-Hypertensive Phenotype

Building upon the clinical implications outlined above, the underlying mechanisms can be conceptualized within a unified framework integrating vascular, renal, and circadian pathways [6]. Accumulating evidence across vascular biology, renal physiology, and BP phenotyping supports a unifying model in which hypertension represents an early clinical expression of subtle yet progressive cardiorenal injury [60,61]. In this framework, three inter-related mechanisms converge:

- Central arterial stiffening, which increases pulsatile pressure transmitted to the renal microcirculation, resulting in impaired autoregulation, glomerular hypertension, and microvascular rarefaction [19].

- Salt sensitivity and tissue RAAS activation, driving sodium retention, endothelial dysfunction, and fibrosis across vascular, cardiac, and renal tissues [62,63].

- Disrupted circadian blood pressure regulation that is recognized as an independent cardiovascular risk factor, exposing the kidney and heart to sustained hemodynamic stress [64,65].

These mechanisms reinforce one another, establishing an early cardiorenal phenotype characterized by mild albuminuria, reduced renal perfusion reserve, altered pressure–natriuresis, increased arterial stiffness, and abnormal ambulatory BP profiles [6,61]. This intertwined renal–vascular disturbance precedes both eGFR decline and cardiac remodeling, presenting clinically as “primary hypertension” [60,66]. Recognizing hypertension as a downstream marker of these early molecular and microvascular insults underscores its role within the cardiorenal continuum and highlighting the need for early, mechanism-oriented interventions [6,60].

9. Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, main uncertainties persist regarding the temporal sequence and relative contribution of vascular, renal, and neurohormonal pathways in the development of early cardiorenal hypertension [67].

In the era of artificial intelligence and machine-learning approaches, technology may enhance the ability to classify hypertension subtypes by combining hemodynamics, microvascular imaging, and molecular signatures [68,69]. Within this framework, large-scale prospective studies integrating ambulatory BP phenotyping, renal microvascular imaging, and omics-based biomarkers are required and validation of emerging biomarkers (NGAL, KIM-1, cystatin C, and ^23Na tissue sodium) is also essential for predicting early cardiorenal injury [68]. Additionally, ABPM is essential for detecting masked and nocturnal hypertension, but considering its limited use, strategies to increase accessibility and streamline interpretation are urgently needed [70].

Although oscillometric cuff-based devices remain the clinical standard for office, home, and ambulatory BP assessment, their intermittent measurements may miss dynamic patterns relevant to early cardiorenal dysfunction [71]. Cuffless wearable BP sensors offer the promise of continuous monitoring but currently lack accuracy sufficient for clinical use, whereas smartwatch-type cuff-oscillometric devices show emerging potential but require further validation. As these technologies evolve, they may enable more precise BP phenotyping and earlier detection of high-risk cardiorenal trajectories [71,72].

Future trials should also evaluate therapeutic decisions and whether early initiation targeted therapies could prevent progression to overt CKD or HFpEF in high-risk patients [73,74].

Collectively, these research avenues are essential to validate the conceptual model proposed in this review and to translate early cardiorenal detection into routine clinical practice.

10. Conclusions

Increasing evidence indicates that, in many individuals, hypertension represents a critical interplay between being a promoter of organ damage and an early clinical manifestation of subclinical cardiorenal disease, reflecting subtle but meaningful dysfunction in the renal microcirculation, vascular wall, and neurohormonal pathways. Consequently, it should not be considered merely as an isolated cardiovascular condition or a simple hemodynamic abnormality. Recognizing these early phenotypes allows for intervention at a stage where vascular and renal changes may still be reversible. Arterial stiffness, salt sensitivity, tissue RAAS activation, and masked or nocturnal hypertension often emerge before traditional markers of kidney or heart disease. These early abnormalities induce a self-perpetuating cycle of sodium retention, endothelial dysfunction, microvascular damage, and neurohormonal reactions that progressively result in chronic kidney disease and heart failure.

Recognizing hypertension as part of the cardiorenal continuum enforces a more mechanism-based approach to diagnosis and therapy, and understanding pathophysiological background can reveal disease long before overt organ damage becomes apparent.

Therapeutic strategies including RAAS blockade, SGLT2 inhibitors, diuretic use, sodium restriction, chronotherapy, and management of comorbidities represent the pillars of early intervention, indicating that disease modification should dominate BP normalization.

Future perspectives promise to redefine hypertension classification and personalize treatment through precision medicine driven by genetic, biomarker, and digital phenotyping. Intervention of the earliest stages of dysfunction, may prevent the transition from subtle microvascular injury to irreversible kidney and heart disease, altering the natural history of the cardiorenal continuum. Viewing hypertension through a cardiorenal lens offers the opportunity for earlier detection and disease modification before irreversible structural damage ensues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and G.A.; methodology, M.B. and G.A.; software, G.A.; validation, M.B., G.A. and C.L.; formal analysis, G.A.; investigation, M.B., N.V. and E.B.; resources, M.B.; data curation, M.B. and G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B., M.S., E.B. and G.A.; visualization, K.P.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABPM | Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ARNI | Angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor |

| AS | Arterial stiffness |

| baPWV | Brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| cfPWV | Carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| HBPM | Home blood pressure monitoring |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| KIM-1 | Kidney injury molecule-1 |

| LV | Left ventricle / left ventricular |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NGAL | Neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PWV | Pulse wave velocity |

| RAAS | Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system |

| RRI | Renal resistive index |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SGLT2 | Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 |

| SSBP | Salt-sensitive blood pressure |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

References

- Goorani, S.; Zangene, S.; Imig, J.D. Hypertension: A Continuing Public Healthcare Issue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, O.Z. Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease: What Lies behind the Scene. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 949260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, E.J. Functional Insights into the Cardiorenal Syndrome. Hypertens. Res. 2024, 47, 1747–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-L. Arterial Stiffness and Hypertension. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 29, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallamaci, F.; Torino, C.; Tripepi, G. Hypertension Burden in CKD: Is Nocturnal Hypertension the Primary Culprit? Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18, sfaf229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, A.; Mazzapicchi, A.; Baiardo Redaelli, M. Systemic and Cardiac Microvascular Dysfunction in Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noels, H.; van der Vorst, E.P.C.; Rubin, S.; Emmett, A.; Marx, N.; Tomaszewski, M.; Jankowski, J. Renal-Cardiac Crosstalk in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 1306–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanoli, L.; Lentini, P.; Briet, M.; Castellino, P.; House, A.A.; London, G.M.; Malatino, L.; McCullough, P.A.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Boutouyrie, P. Arterial Stiffness in the Heart Disease of CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzau, V.J.; Hodgkinson, C.P. Precision Hypertension. Hypertension 2024, 81, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M.; Damianaki, A. Hypertension as Cardiovascular Risk Factor in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.S.; Kwon, S.U. Arterial Stiffness as a Predisposing Factor for Chronic Kidney Disease. JACC Asia 2024, 4, 454–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P. Arterial Stiffness and Hypertension in the Elderly. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 544302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.S. Arterial Stiffness and Hypertension. Clin. Hypertens. 2018, 24, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Chatellier, G.; Azizi, M.; Calvet, D.; Choukroun, G.; Danchin, N.; Delsart, P.; Girerd, X.; Gosse, P.; Khettab, H.; et al. SPARTE Study: Normalization of Arterial Stiffness and Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Hypertension at Medium to Very High Risk. Hypertension 2021, 78, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, M.J.; Müller, P.; Lechner, K.; Stiebler, M.; Arndt, P.; Kunz, M.; Ahrens, D.; Schmeißer, A.; Schreiber, S.; Braun-Dullaeus, R.C. Arterial Stiffness and Vascular Aging: Mechanisms, Prevention, and Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgianos, P.I.; Pikilidou, M.I.; Liakopoulos, V.; Balaskas, E.V.; Zebekakis, P.E. Arterial Stiffness in End-Stage Renal Disease—Pathogenesis, Clinical Epidemiology, and Therapeutic Potentials. Hypertens. Res. 2018, 41, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querfeld, U.; Mak, R.H.; Pries, A.R. Microvascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: The Base of the Iceberg in Cardiovascular Comorbidity. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 1333–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inserra, F.; Forcada, P.; Castellaro, A.; Castellaro, C. Chronic Kidney Disease and Arterial Stiffness: A Two-Way Path. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 765924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutouyrie, P.; Chowienczyk, P.; Humphrey, J.D.; Mitchell, G.F. Arterial Stiffness and Cardiovascular Risk in Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciunescu, A.; Genovese, L.; de Filippi, C. Cardiovascular Alterations and Structural Changes in the Setting of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Review of Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 4. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2023, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, R.; Yan, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, L. Nonlinear Relationship between Estimated Pulse Wave Velocity and Chronic Kidney Disease: Analyses of NHANES 1999–2020. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1560272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, N.; Thakrar, C.; Patel, K.; Viberti, G.; Gnudi, L.; Karalliedde, J. Increased Arterial Stiffness Is an Independent Predictor of Renal Function Decline in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Younger Than 60 Years. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beros, A.L.; Sluyter, J.D.; Scragg, R. Association of Arterial Stiffness with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2024, 49, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Aroor, A.R.; Hill, M.A.; Sowers, J.R. Role of RAAS Activation in Promoting Cardiovascular Fibrosis and Stiffness. Hypertension 2018, 72, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montomoli, M.; Gonzalez Ricoa, M.; Terue, J.L.G.; Puchades Montesa, M.J.; Nuñez Marín, G.; Lecueder, M.S. Addressing Renal Sodium Avidity in Chronic Heart Failure: There Is Always More than One Way to Skin a Cat. Cardiorenal Med. 2025, 15, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.A.; Dhaun, N. Salt Sensitivity: Causes, Consequences, and Recent Advances. Hypertension 2024, 81, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandes, R.P. Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension. Hypertension 2014, 64, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, G.; Volpe, M.; Savoia, C. Endothelial Dysfunction in Hypertension: Current Concepts and Clinical Implications. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 798958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovée, D.M.; Cuevas, C.A.; Zietse, R.; Danser, A.H.J.; Mirabito Colafella, K.M.; Hoorn, E.J. Salt-Sensitive Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease: Distal Tubular Mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2020, 319, F729–F745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Wu, C.; Xu, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhao, M.; Zu, L. The NO-cGMP-PKG Axis in HFpEF: From Pathological Mechanisms to Potential Therapies. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Wang, L.; d’Ambrosio, L.; Bierschenk, S.; Hamers, J.; Ornek, I.; Sittig, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Merkus, D. Coronary Microvascular Disease in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Physiol. Rep. 2025, 13, e70521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakris, G.L.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Pitt, B.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Schloemer, P.; Joseph, A.; et al. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallon, V.; Verma, S. Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Kidney and Cardiovascular Function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2021, 83, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elijovich, F.; Weinberger, M.H.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Appel, L.J.; Bursztyn, M.; Cook, N.R.; Dart, R.A.; Newton-Cheh, C.H.; Sacks, F.M.; Laffer, C.L.; et al. Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2016, 68, e7–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsioufis, C.; Tsiachris, D.; Kasiakogias, A.; Dimitriadis, K.; Petras, D.; Goumenos, D.; Siamopoulos, K.; Stefanadis, C. Preclinical Cardiorenal Interrelationships in Essential Hypertension. Cardiorenal Med. 2013, 3, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drawz, P.E.; Alper, A.B.; Anderson, A.H.; Brecklin, C.S.; Charleston, J.; Chen, J.; Deo, R.; Fischer, M.J.; He, J.; Hsu, C.; et al. Masked Hypertension and Elevated Nighttime Blood Pressure in CKD: Prevalence and Association with Target Organ Damage. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2016, 11, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, M.; Drawz, P. Masked Hypertension in CKD: Increased Prevalence and Risk for Cardiovascular and Renal Events. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2019, 21, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakoulis, K.G.; Kollias, A.; Stergiou, G.S. Masked Hypertension: How Not to Miss an Even More Silent Killer. Hypertens. Res. 2023, 46, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, H.N.; Shetty, S.; Chopra, A.; Navasundi, G.B.; Mehta, A.; Kumbla, D.; Jain, P.; Baruah, D.K.; Singhal, A.; Kumar, Y.S.; et al. Optimizing the Diagnosis and Management of Nocturnal Hypertension: An Expert Consensus from India. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2025, 73, e24–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuspidi, C.; Gherbesi, E.; Faggiano, A.; Sala, C.; Carugo, S.; Grassi, G.; Tadic, M. Masked Hypertension and Exaggerated Blood Pressure Response to Exercise: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penmatsa, K.R.; Biyani, M.; Gupta, A. Masked Hypertension: Lessons for the Future. Ulster Med. J. 2020, 89, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kario, K. Nocturnal Hypertension. Hypertension 2018, 71, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabia, J.; Torguet, P.; Garcia, I.; Martin, N.; Mate, G.; Marin, A.; Molina, C.; Valles, M. The Relationship Between Renal Resistive Index, Arterial Stiffness, and Atherosclerotic Burden: The Link Between Macrocirculation and Microcirculation. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2014, 16, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Jo, S.-H. Nighttime Administration of Antihypertensive Medication: A Review of Chronotherapy in Hypertension. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kario, K.; Ferdinand, K.C.; O’Keefe, J.H. Control of 24-Hour Blood Pressure with SGLT2 Inhibitors to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habas, E.; Errayes, A.; Habas, E.; Alfitori, G.; Habas, A.; Farfar, K.; Rayani, A.; Habas, A.; Elzouki, A.-N. Masked Phenomenon: Renal and Cardiovascular Complications; Review and Updates. Blood Press. 2024, 33, 2383234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Shim, C.Y.; Hong, G.R.; Park, S.; Cho, I.J.; Chang, H.J.; Ha, J.W.; Chung, N. Impact of Ambulatory Blood Pressure on Early Cardiac and Renal Dysfunction in Hypertensive Patients without Clinically Apparent Target Organ Damage. Yonsei Med. J. 2018, 59, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraci, G.; Ferrara, P.; La Via, L.; Sorce, A.; Calabrese, V.; Cuttone, G.; Paternò, V.; Pallotti, F.; Sambataro, G.; Zanoli, L.; et al. Renal Resistive Index from Renal Hemodynamics to Cardiovascular Risk: Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Implications. Diseases 2025, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kario, K. Home Blood Pressure Monitoring: Current Status and New Developments. Am. J. Hypertens. 2021, 34, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, C.; Sorce, A.; Vario, M.G.; Cirafici, E.; Bologna, D.; Ciuppa, M.E.; Evola, S.; Mulè, G.; Geraci, G. Relationship Between Subclinical Renal Damage and Maximum Rate of Blood Pressure Variation Assessed by Fourier Analysis of 24-h Blood Pressure Curve in Patients with Essential Hypertension. Life 2025, 15, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, K.; Naderi, H.; Thomson, R.J.; Aksentijevic, D.; Jensen, M.T.; Munroe, P.B.; Petersen, S.E.; Aung, N.; Yaqoob, M.M. Prognostic Impact of Albuminuria in Early-Stage Chronic Kidney Disease on Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Cohort Study. Heart Br. Card. Soc. 2025, 111, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Vírgala, J.; Martín-Carro, B.; Fernández-Villabrille, S.; Fernández-Mariño, B.; Astudillo-Cortés, E.; Rodríguez-García, M.; Díaz-Corte, C.; Fernández-Martín, J.L.; Gómez-Alonso, C.; Dusso, A.S.; et al. Non-Invasive Assessment of Vascular Damage Through Pulse Wave Velocity and Superb Microvascular Imaging in Pre-Dialysis Patients. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, V.; Nair, S.; Elfeky, O.; Aguayo, C.; Salomon, C.; Zuñiga, F.A. Association between Insulin Resistance and the Development of Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Kashani, K.B. Beyond Creatinine: New Methods to Measure Renal Function? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 134, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Tan, S.-J.; Toussaint, N.D. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Determination of Tissue Sodium in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrology 2022, 27, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, P.; McEvoy, J.W. Salt Restriction for Treatment of Hypertension—Current State and Future Directions. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2024, 39, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamout, H.; Lazich, I.; Bakris, G.L. Blood Pressure, Hypertension, RAAS Blockade, and Drug Therapy in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014, 21, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Bhatt, D.L.; Cosentino, F.; Marx, N.; Rotstein, O.; Pitt, B.; Pandey, A.; Butler, J.; Verma, S. Non-Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Cardiorenal Disease. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2931–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, N.; Tunis, R.; Ariyo, A.; Yu, H.; Rhee, H.; Radhakrishnan, K. Trends and Gaps in Digital Precision Hypertension Management: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e59841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Mori, T. CKD Progression from Early-Onset Hypertension: On the Unexpected Rapidity within 10 Years of Follow-Up. Hypertens. Res. 2025, 48, 2487–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandait, H.; Sodhi, S.S.; Khandekar, N.; Bhattad, V.B. Cardiorenal Syndrome in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Insights into Pathophysiology and Recent Advances. Cardiorenal Med. 2025, 15, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutengo, K.H.; Ngalamika, O.; Kirabo, A.; Masenga, S.K. Salt Sensitivity and Myocardial Fibrosis: Unraveling the Silent Cardiovascular Remodeling. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1626492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Ren, K. The Multifaceted Impact of a High-Salt Environment on the Immune System and Its Contribution to Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 44, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, R.; Jiang, T.; Yang, G.; Chen, L. Circadian Blood Pressure Rhythm in Cardiovascular and Renal Health and Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuszkiewicz, J.; Rzepka, W.; Markiel, J.; Porzych, M.; Woźniak, A.; Szewczyk-Golec, K. Circadian Rhythm Disruptions and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: The Special Role of Melatonin. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.-H. Primary Role of the Kidney in Pathogenesis of Hypertension. Life 2024, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, U.; Garimella, P.S.; Wettersten, N. Cardiorenal Syndrome-Pathophysiology. Cardiol. Clin. 2019, 37, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaidi, S. Emerging Biomarkers and Advanced Diagnostics in Chronic Kidney Disease: Early Detection Through Multi-Omics and AI. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalidis, I.; Maurizi, N.; Salihu, A.; Fournier, S.; Cook, S.; Iglesias, J.F.; Laforgia, P.; D’Angelo, L.; Garot, P.; Hovasse, T.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Digital Health for Hypertension: Evolving Tools for Precision Cardiovascular Care. Medicina 2025, 61, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.F.; Thongprayoon, C.; Miao, J.; Pham, J.H.; Sheikh, M.S.; Garcia Valencia, O.A.; Schwartz, G.L.; Craici, I.M.; Gonzalez Suarez, M.L.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Advancing Personalized Medicine in Digital Health: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Clinical Interpretation of 24-h Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076251326014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinou, N.; Sinou, N.; Koutroulakis, S.; Filippou, D. The Role of Wearable Devices in Blood Pressure Monitoring and Hypertension Management: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e75050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, G.S.; Menti, A.; Mariglis, D.; Kollias, A. The Quest for Accurate Wearable Blood Pressure Monitors. Hypertens. Res. 2025. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehbe, F.; Elliott, M.; Levin, A. CKDs at the Crossroads: From Failures to Future Therapies. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 4145–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Judge, P.K.; Staplin, N.; Haynes, R.; Herrington, W.G. Design Considerations for Future Renoprotection Trials in the Era of Multiple Therapies for Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, i70–i79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.