Abstract

The ‘Parents as Partners’ (PasP) coparenting programme was delivered to heterosexual parents of infants they described as showing a highly reactive temperament (HRT) following the completion of the Infant Behaviour Questionnaire–Revised (IBQ-R) during a standard post-natal visit in their local Health Centre Well Baby Clinic in Malta. Fifty-two participating Maltese couples, all coparenting a highly reactive infant of 8 to 12 months, were randomly assigned into an experimental (n = 30 couples) or control group (n = 25). The IBQ-R, Coparenting Relationship Scale (CRS), and Parental Stress Index (PSI-4 SF) at pre- and post-intervention periods were filled out by randomised participants. Intervention group couples followed the 16-week PasP programme. All randomised couples were followed by a case manager monthly. Post-intervention results compared with controls showed reduced couple conflict occurring in front of the child, reduced parent–child dysfunctional interaction, and a reduction in negative child reactivity. Implications point to the importance of including fathers and reducing coparenting conflict in interventions designed to reduce behavioural difficulties in infants and young children.

1. Introduction

Temperament is considered as the child’s disposition, which is not expressed all the time, but interacts with their environment (Rothbart, 2011). It exists as an interactional system between the parents and infant/child. Parents’ ability to adapt and sensitively relate to their child’s temperament is a crucial predictor of how well the child learns to self-regulate, and the long-term implications on the child’s future adjustment and well-being (Bornstein et al., 2014; Kozlova et al., 2019). An infant/child that is harder to soothe, becomes easily irritable, slower to adapt, reacts intensely to stimuli, becomes easily startled, and is more tearful and negative may be considered as showing a HRT (Putnam et al., 2014).

Infants with a highly reactive temperament (HRT) are more at risk of developing anxiety, hyperactivity, and autism over time (Buss & Kiel, 2013). In fact, such infants may evoke an interactional exchange between the parents as co-parents, and in interaction with their child. Each parent’s response to their infant helps to soothe or aggravate him/her in a reciprocal and interactive exchange (Hong et al., 2015). In the context of a strained or conflictual couple/parental relationship, where there is disagreement about how best to respond to their highly reactive child, their child’s level of negative reactivity will likely increase (Cook et al., 2009). Considering the interactional nature and impact on the couple’s relationship and the quality of the parent–child relationships, and its implications on future child development and well-being, the importance of supporting parents of infants with a HRT is high.

Most programmes addressing difficulties in infant/child behaviour focus on what parents (mostly mothers) can do to affect the child. Only a handful include fathers and address issues involved in the couple relationship context in which parenting occurs. Two programmes that do, namely, the Family Foundations Programme (Feinberg, 2002) and Supporting Father Involvement (SFI) (Pruett et al., 2017; Pruett et al., 2019) have provided evidence that improvements in couple relationship quality lead to improvements in parenting quality, followed by positive effects on the child’s behaviour. SFI was later used in the UK and renamed Parents as Partners (Casey et al., 2017). The PasP programme was chosen for the present intervention because of its extensive body of validation studies (Cowan & Cowan, 2018). It also reflects an understanding that a child’s ability to develop healthily is predominantly based on the parents’ relationship quality, existing across relational interactions in five family-life domains (Cowan & Cowan, 2008). These domains include the parent–child relationship, the parent’s relationship as a couple, the transgenerational relationships, the individual parents’ well-being, and external family support and stress (Cowan & Cowan, 2008).

The theoretical framework adopted for this study is systemic. It is informed by several studies pointing out how the quality of the couple relationship transitioning to parenthood impacts parental well-being, their offspring, and the other children forming part of the family (Grevenstein et al., 2019; McHale & Lindahl, 2011; Redshaw & Martin, 2014). Furthermore, parenting an infant with a HRT takes place in a system of bi-directional relationships. Thus, whereas couple relationships affect parenting, which has an effect on the child’s development in terms of temperament, ability to self-regulate (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981), and the child’s cognitive abilities over time (Suor et al., 2017), a child’s unique temperament can present a challenge for parents who find it difficult to recognise and adapt to their child accordingly, potentially straining the parent–child relationship and negatively impacting the couple relationship. Coparenting an infant with a HRT involves a complex interplay of relationships. The parents’ relationship is an interconnected system that influences the infant, while the infant’s development in turn impacts the parents’ dynamics (Brown, 2008).

Considering the importance of the coparenting relationship and its interaction with the child’s emotional regulation and well-being (Suor et al., 2017), this research sought to evaluate, through a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) parallel group design, whether offering parents of highly reactive infants the opportunity to follow the PasP coparenting programme enabled them to parent more effectively together, and whether this resulted in the infant/child’s behavioural change. The first hypothesis was that participation in the PasP would support parents to coparent more effectively, positively impacting their infant’s behaviour. A second, more exploratory hypothesis based on systemic theory (Cowan & Cowan, 2018) was that there would be indirect effects of the intervention on the infant’s behaviour through the impact of PasP participation on the quality of the couple and coparenting relationships.

This research presents a randomised controlled study using the coparenting programme ‘Parents as Partners’ (PasP) (Casey et al., 2017) to examine whether it would support more effective parenting of infants with a HRT. This is the first study using PasP as an intervention with parents of infants described as having a HRT, making it unique.

2. Materials and Methods

The 2018 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials—Social and Psychological Interventions (CONSORT-SPI 2018) (Montgomery et al., 2018) was followed for transparency and clarity in reporting the details of this RCT. The published research protocol can be accessed in full on https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN55209338, registered on 25 September 2017. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee within the Faculty for Social Wellbeing, at the UNIVERSITY OF MALTA (SWB 220/2016—approved on 21 March 2017).

2.1. Participants

The study was open to couples parenting an infant aged 8 months at the time of recruitment, since this age is considered to be the time when temperament emerges more clearly (Rothbart, 1981). The child did not necessarily need to be a first or only child, and parents could have been parenting other children. For inclusion parents needed to be either living together or caring for their infant together, when attending their routine 2nd post-natal Well Baby Clinic visit for 8–12-month-old infants. All available eligible couples who responded were heterosexual.

2.2. Target Sample

Considering the Maltese context, and statistics reflecting that only 3.8% of all Maltese infants were born to widowed, separated/divorced mothers according to the National Obstetric Information System annual report for 2017 (Gatt & Cardona, 2019), only couples with young infants living and/or parenting their infant together were included in the study. Another inclusion criterion was for either parent to describe their infant as showing a HRT (obtaining a score of 4.78+ on the negative affect scale of the IBQ-R). The 4.78 score was determined following a sample average based on the first 100 parents completing the IBQ-R, rendering a mean score of 3.82 on the negative affect scale, and a standard deviation of 0.96. Parents who scored a standard deviation higher (3.82 + 0.96 = 4.78) than the average on the scale were included (S. Putnam, personal communication, 9 July 2017).

Parents needed to speak and/or understood the Maltese language, since the majority of parents attending state-run Well Baby Clinics were Maltese, and the PasP intervention group was being carried out in Maltese. Parents eligible for participation and randomisation were both required to have completed the IBQ-R, the Parenting Stress Index—Short Form (PSI-4-SF), and the Coparenting Relationship Scale (CRS) separately.

2.3. Recruitment

Recruitment took place by the principal researcher across all Well Baby Clinics in Malta over an 18-month period. There were three recruitment phases, working up towards each PasP group cluster randomisation, resulting in a total of 4 PasP groups of 8 couples in each with the same aged infants, alongside their respective control group.

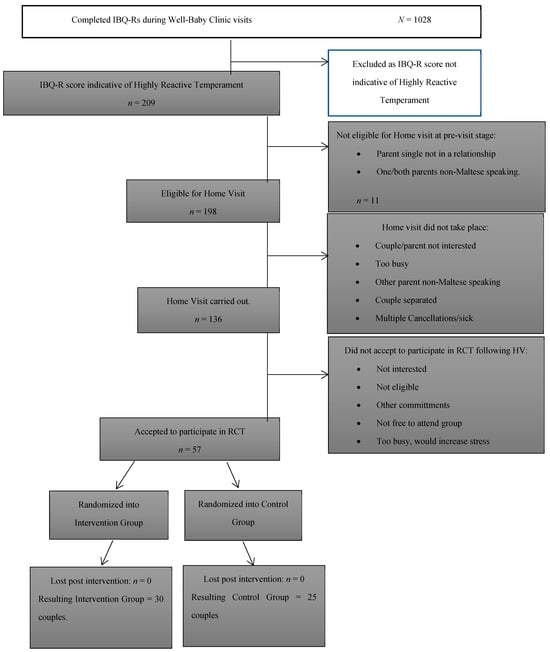

Phase 1: Parents (mostly mothers) attending their routine 2nd post-natal appointment were invited to fill in the IBQ-R whilst in the waiting area. They were told that they would be contacted by phone, email, or post, to be given feedback about their child’s behaviour/temperament according to their descriptions on the questionnaires. A total of 1028 parents consented to filling the IBQ-R at phase one.

Phase 2: Parents whose infant obtained a score of 4.78+ on the IBQ-R were invited for a feedback meeting through a home visit with both parents present. From 209 questionnaires obtaining the 4.78+ score, n = 198 were eligible for a home visit. Those excluded were either parenting alone or non-Maltese speaking. Those scoring 4.78−, including non-eligible parents, were given feedback through a written descriptive summary reflecting their responses (819 + 11 = n = 830). A total of 136 home visits were carried out from the 198 eligible.

Phase 3: Parents consenting to a home visit (n = 136) were given feedback together as a couple. The visit lasted approximately an hour. Parents were invited to participate in the randomisation and were given information about PasP, its duration, and that, if randomised into the programme, they would be supported with free childcare. On consent, parents were invited to fill in additional measures separately, namely the PSI-4-SF and the CRS. A total of 57 couples accepted participation by filling in questionnaires and being included in the randomisation.

Every PasP group held a maximum number of 8 couples because of effectiveness, management of group experience, and the intimate nature of the group (Wheelan, 2009). This was also the average size of previous SFI and PasP groups held in the USA (Pruett et al., 2019) and the UK (Casey et al., 2017).

Consenting couples were randomised into an intervention or control group. Every couple was assigned a numerical code at recruitment stage, and numbers were drawn by an uninvolved third party by randomisation sequencing. This method of randomisation was specifically used to avoid any risk of bias, going into great lengths to ensure allocation was performed blindly, considering that the principal researcher was conducting the research single-handedly, and leaving all to chance (Dynarski & Del Grosso, 2008). Figure 1 shows recruitment progression and randomisation.

Figure 1.

Trial flow chart: Recruitment progression and randomisation.

2.4. Procedure

Given that this was a pilot RCT with a limited time-frame, we predetermined the number of participating couples to 60, thus ending the trial with 4 PasP groups once the participant number was reached. A total of 32 couples were originally randomised into the intervention group and 25 into the control group. Of the 32 intervention group couples, 2 failed to fill in all their questionnaires at pre-test, were no longer reachable, and were removed from the study, leaving 30 couples in the intervention group. These couples attended a 2 h long meeting with their PasP group facilitators, following the Group Worker Interview structure used at the Tavistock Relationships, UK. This meeting served as an opportunity to connect with participants before the start of the PasP programme, and to establish the safety of working with them as a couple. The PasP programme consisted of sixteen 2 h sessions, held weekly in a group context. Each session followed a precise outline/procedure adhering to the ‘PasP Groupwork Manual’ (Tavistock Relationships, 2017). Sessions allowed couples to discuss and practice different concepts presented in the group programme, including parenting styles, emotional well-being, couple communication and conflict management/styles, amongst other concepts.

Four PasP groups were co-facilitated by male/female group leaders trained specifically by the Tavistock Relationships staff in the UK. Co-facilitators, including the first author, were experienced therapists. They were supervised regularly by an accredited supervisor from Tavistock Relationships, UK, to support PasP consistency and model fidelity. Complementary to the PasP programme, participants were supported by a case manager who called parents in the intervention and control groups monthly, and spoke to them briefly, separately and together, in order to check-in with them and to offer support when needed.

The intervention and control group participants revealed that a majority of the mothers had a tertiary level education, and a majority of fathers were predominantly educated at post-secondary level. Data describing sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

2.5. Measures

A number of measures were used at pre- and post-intervention. Recruitment measures started with the IBQ-R, followed by the PSI-4 SF and CRS during home visits before randomisation. The PSI-4 SF and CRS were completed by all intervention and control group participants at pre- and post-intervention stages.

Measures were translated into the Maltese language and validated by the researcher, so participants opted for either an English or Maltese version questionnaire, considering that Malta is bi-lingual. The same questionnaires were repeated two months post-intervention, with the exception of the Early Childhood Behaviour Questionnaire (ECBQ) follow-up replacing the IBQ-R for age-appropriate reasons, since children were aged on average 1.5 years at the post-intervention period.

The Coparenting Relationship Scale (CRS), a 35-item self-report measure with questions about the coparenting relationship, is used across varying contexts and parenting dyads, and was developed on the concept of coparenting, as developed by Feinberg (2003), and presents with a Cronbach Alpha ranging between >0.91 and >0.94 (Feinberg, 2003). The translated Maltese version of this scale rendered a Cronbach Alpha of >0.82. The CRS is structured around 4 predominant scales focusing on the parents’ agreement on childrearing, their level of support/undermining, division of labour, and their dynamics as a couple. Parents were separately asked to indicate their response on a 7-point Likert Scale from 0 (not true of us) to 6 (very true of us).

The Parenting Stress Index—4th Edition—Short Form (PSI-4 SF) consists of 36 items, which measure stress in the parent–child relationship and possesses a Cronbach Alpha of >0.92 (Aracena et al., 2016). The validated Maltese translation of the measure rendered a Cronbach Alpha of >0.75. The PSI-4 SF can identify problems in the parent–child relationship amongst parents of children from 0 to 12 months (Abidin, 2012). Questions in the PSI-4-SF are organised around three principle domains, covering parental distress, an interaction between parent and child that is dysfunctional, and questions that highlight ‘difficult’ child behaviour (Abidin, 2012). Parents were separately asked to indicate their responses to the questions on a 5-point Likert Scale from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree.

The Infant Behaviour Questionnaire–Revised (IBQ-R) is designed to measure infant temperament (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003) and possesses a Cronbach Alpha of >0.70. The validation of the Maltese translation of the measure rendered a Cronbach Alpha of >0.85. This questionnaire consists of 37 items and is used specifically with infants between 3 and 12 months, measuring different dimensions of surgency, negative affect, and effortful control (Putnam et al., 2014). Parents were separately asked to read the different items on the questionnaire, which reflected descriptions of infant behaviour. They were asked to indicate the frequency of the particular description of behaviour on a 7-point Likert Scale ranging from never to always. The questionnaire took on average 12 min to complete, following which a score was calculated, indicating whether or not subsequent measures would be carried out based on the 4.78-point threshold for inclusion on the negative affect scale.

The Early Childhood Behaviour Questionnaire (ECBQ) (Putnam et al., 2008) developed for use with children aged 1–3 years, was used at post-intervention stage and served as a stable longitudinal assessment of child temperament between measures from pre- to post-intervention periods (Putnam et al., 2008). The 36-item questionnaire carries a Cronbach Alpha of >0.71 (Putnam et al., 2010), with the Maltese translated version rendering a >0.61 Cronbach Alpha. Similarly to the IBQ-R, the ECBQ was also represented by the same three-factor structures of surgency, negative affect, and effortful control, with questions that were more appropriate to children older than 1 year. Of the 36 items, 12 focus particularly on negative affectivity and include similar dimensions to the IBQ-R. Parents were asked to score the questionnaire separately on its 8-point Likert Scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always) or NA (not applicable).

2.6. Analysis

Data from pre- and post-intervention questionnaires were inputted into Version 25 of IBM SPSS according to respective participants’ numerical codes assigned at the recruitment stage. Means and standard deviations for all measures at pre- and post-intervention were compared across groups (Table 2 and Table 3). All data was analysed, including missing measures from the original couples who dropped out post-randomisation, forming part of an ‘Intention-To-Treat’ analysis (McCoy, 2017).

Table 2.

Pre-test baseline means and standard deviations of mothers and fathers across measures for all groups.

Table 3.

Post-test means and standard deviations of mothers and fathers across measures for all groups.

To assess the impact of the intervention we used a mixed model three-way analysis of variance (intervention condition × time × gender). In this model, the intervention condition assessed between-group differences, while both time (pre/post) and gender (mother/father) differences were treated as within-group effects. The impact of the intervention was assessed by the condition × time interaction term—when the positive pre/post change in the PasP participants was statistically significantly greater than the pre/post change in the controls.

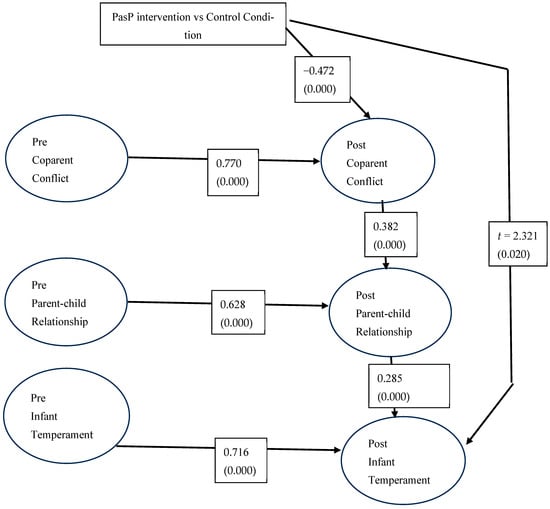

SmartPls software (Hair et al., 2016) was used to determine the links between intervention participation and each of the latent variables representing both parents’ reports of couple, coparenting, and infant behaviour. Latent variable measures were created including both parents’ reports of (a) the infant’s exposure to coparenting conflict, (b) parent–child relationship quality, and (c) infant temperament. In the model for this study, coparenting behaviour was measured by parents’ reported conflict in front of the child. The latent variable representing the quality of parent–child relationships included both parents’ reports of father involvement, parenting stress, and dysfunctional parent–child relationships. Finally, the latent variable measure of infant temperament included the dysfunctional parenting scale from the PSI-4 SF and the temperament measures from pre- and post-test. In Figure 2, the paths linking pre-test and post-test latent variables can be interpreted as measures of change over time.

Figure 2.

Direct and indirect effects of PasP on coparenting, parenting, and infant temperament. Path weights and significance levels.

Considering the small sample size we did not test for child gender effects.

3. Results

3.1. Statistically Significant Interventions

Table 4 presents a summary of the analyses of the impact of the Malta PasP on self-reports of couple conflict, parent–child relationship quality, and infant behaviour at pre- and post-intervention assessments.

Table 4.

Summary of statistically significant intervention effects.

3.1.1. Couple/Coparenting Effects

Compared with controls, intervention participants reported greater reductions in their infant’s exposure to their conflict (F(2,95) = 4.443, p = 0.032). Moreover, PasP intervention mothers were more likely to report less exposure to conflict (ETC) happening in front of the child (F = 5.747, p = 0.004), unlike control groups mothers where ETC increased.

Also, in comparison to change in the control, PasP participants improved in coparenting closeness (F(2,99) = 3.462, p = 0.035). They also reported increased endorsement (F(2,99) = 2.047, p = 0.035) and less undermining (F(2,99 = 8.193, p < 0.001) of each other’s coparenting behaviour.

Intervention mothers and fathers reported significantly different intervention effects on two measures: In comparison with controls, PasP mothers reported more coparenting agreement than fathers did (F(1,99) = 4.880, p = 0.029). PasP fathers, on the other hand, reported more reductions in parental distress than mothers did (F(1,99) = 7.183, p = 0.009).

Parenting effects: Intervention group parents were more likely to report that their division of labour was shared than parents in the control group, and increases in involvement over time were larger in fathers’ reports than mothers’ reports (condition × time × gender: F(1,98) = 11.641, p = 001). PasP parents also reported a condition × time × gender effect on parenting stress (F = 7.183 p < 0.000). There were, however, no direct effects of group participation on parents’ ratings of dysfunctional parent–child interaction.

3.1.2. Child Effects

Post hoc tests showed that intervention mothers and especially fathers described their infants’ behaviour more positively at post (F = 4.443, p = 0.014), whereas control group parents’ descriptions remained stable. Similarly, PasP group fathers were more likely to report less ETC, compared with only a minimal decrease in conflict in the control group.

According to the conventions of interpreting the magnitude of Cohen’s d effect sizes (Cohen, 1988), the intervention effects were small to medium in size, ranging from 0.29 to 0.69 (see Table 4), but the intervention effects obtained here are substantially larger than those usually obtained in couples-focused parenting interventions (Cowan et al., 2022), reflecting meaningful changes in PasP family systems.

3.1.3. Indirect Effects of the Intervention

Analyses of variance assess the direct impact of the intervention on one variable at a time. Fathers’ involvement in the daily tasks of caring for the children was the only measure to show a direct intervention impact in the parenting domain.

The intervention has a direct effect on reducing couple conflict, and accounts for a significant portion of the variances in parenting, as well as for a significant amount of the variance in child behaviour. These indirect effects were examined by using SmartPls software (Hair et al., 2016) to create a Structural Equation Model (SEM) that traced pathways linking the intervention effect with latent variable connections among coparenting quality, parenting quality, and infant temperament (See Figure 2).

First, in parallel with the analyses of variance, the SmartPls analysis found that the intervention had a direct effect on reducing negative couple conflict (t = 3.135; p = 0.002). Other direct links between participation in PasP and parenting quality, or direct links between intervention and the infant’s behaviour were not statistically significant, so the paths were not included in Figure 2; all paths included in the figure represented statistically significant connections between latent variables.

The SmartPls SEM enables us to test for statistically significant indirect paths—whether the impact of the intervention on the infant’s behaviour occurs in a cascading fashion from participation in the intervention to couple relationship qualities to parenting quality to child outcome. Apart from the direct impact on couple conflict, the indirect effect was statistically significant (t = 2.34; p = 0.020). Intervention participants who reduced their conflict when the child was present reported that fathers were more involved and both parents had less stressful, less dysfunctional relationships with their infants. In turn, their infants were less temperamentally reactive after parental participation in PasP.

Given the known risks to the child’s development and the tenor of the parents’ couple relationship of having a child with a HRT, the positive results of this intervention with the parents of challenging young children seem noteworthy. The fact that attention to both the parents’ relationship as a couple and to strategies for supportive parenting in the early years of the children’s development had the potential to change the risks to mothers, fathers, and their young children suggests that such work with new parents can make important strides in our support of family relationship quality.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mothers, Fathers, and Their Infants Affected Positively by the PasP

The salient findings from this RCT were that supporting parents through the PasP reduced couple conflict happening in front of the child, along with other coparenting improvements, less dysfunctional parent–child interactions, and a reduction in child’s negative reactivity. These transformative changes within the family are a reflection of interaction within the system (Meadows, 2008) (See Figure 2). The Structural Equation Model analysis helped us trace such interaction pathways that were systemic in nature.

The changes were only evident in the intervention group parents, with only a slight non-significant change in the control group parents who reported minimal decline in their child’s negative reactive behaviour.

Despite case manager support offered to all parents, mothers in the control group reported a slight but nonsignificant increase in the child’s exposure to conflict. Mothers in the control group did not have the same opportunity to be supported along with fathers as were intervention group mothers. The lack of support for the couple might also explain the increase in the child’s exposure to conflict as reported by mothers in the control group. These results suggest that the case manager’s support did not suffice to minimise conflict between parents in this group.

4.2. Generalisability and Relevance of Findings to Existing Research on Supporting Couples

The findings from this RCT are consistent with evaluations of similar couple-focused parenting interventions. PasP was carried out in the UK with 97 low-income couples by Casey et al. (2017) and the SFI Programme’ was carried out in California in the US with almost 1000 parents in three different studies by Pruett et al. (2019). Both sets of studies had similar effects. The main focus of PasP was that of supporting fathers to be more involved in parenting, nourishing the relationship of the couple and their respective relationships with their child (Cowan & Cowan, 2018). PasP helped link parents’ behaviour toward each other in a systemic way so that effects were seen in their behaviour with their children and in their children’s behaviour (Pruett et al., 2019, p. 63). The SFI study with a curriculum almost identical to the Malta PasP, showed a reduction in reported conflict in the intervention group parents from baseline to 6 months post-baseline. Moreover, SFI also had a direct effect on further reductions in conflict at 18 months post-baseline and significant indirect effects on reductions in harsh parenting, and children’s behaviour problems.

4.3. Impact of Stress on Parenting

Risk factors resulting from daily stressors and challenges, coupled with relationship difficulties and a highly reactive child, are considered to be detrimental for coparenting relationship quality (McDaniel et al., 2018) and to influence the way parents perceive their child. A study by Burney and Leerkes (2010) showed that when mothers are dissatisfied with the quality of the coparenting relationship, and fathers are dissatisfied with the quality of the marital relationship, there was a tendency to perceive the child more negatively. In the present study, harsh and critical interactions decreased for those couples who participated in the group programme. The tendency for parents to use harsher parenting practices increases in the presence of higher relationship conflict, which has serious implications for the couple’s well-being and places the child at greater risk of maltreatment, and mental health/behaviour problems (Hong et al., 2015).

4.4. Increasing Support by Increasing Father Involvement

Most PasP group parents in this study reported an increased level of support from their respective partners. Existing literature shows that men parent effectively once they are given increased opportunity to be involved in parenting. This involvement is linked to a positive father–child relationship, increased maternal and couple relationship support, and ultimately positive child development and well-being (McHale & Lindahl, 2011). Unfortunately, fathers continue to be excluded or peripheral in most family-related services (Norman, 2017). Fathers’ participation in parenting programmes is still low (Tully et al., 2017). Part of the explanation for the latter may be related to mothers’ gatekeeping, as well as to that of professionals (Glynn & Dale, 2016).

4.5. Limitations

This randomised controlled trial using PasP in the current study used a very small sample. Nevertheless, even with low power, a number of statistically significant intervention effects were detected.

Consistent with systemic views of the family, it is conceivable that a positive improvement in the child’s behaviour reported by the intervention group parents could have been the result of the infant’s normal maturational process (Bornstein et al., 2015). What contradicts this interpretation is that parents in the control group, over the same number of months did not report improvements in their infant’s behaviour.

We recognise that the data in this study came from parent reports. It is possible that participating in PasP helped to make the parents more comfortable and less negative in their descriptions of their infants, especially as they found that others had similar challenges. Further studies are needed that include observations of coparents, parent–child interaction, and the children themselves.

The results of the SEM analysis, presented in Figure 2, suggest that supporting participants as parents and partners through the PasP helped to modify their tendency to engage in conflict in front of their child, and to become more supportive, collaborative partners in parenting, and that these changes led to a reduction in their infant’s negative reactive behaviour. Given that all the post-intervention measures were taken at the same time, we cannot be certain that the ordering of the changes represents a causal chain of influence from couple to parenting to child effects. Studies are needed that track post-intervention trajectories over at least three time periods, so that we can see whether earlier intervention-induced reductions in couple conflict lead to later improvements in parent–child relationship quality and reductions in negative aspects of temperament.

4.6. Implications for Practice

Early intervention is crucial, particularly in circumstances where parents face challenging and stressful situations, including having an infant with a HRT. With greater potential risks for parents and children in difficult and challenging circumstances, timely intervention becomes necessary to offer support and avoid relationship breakdown. Findings of this research reflect the importance of targeting an intervention when parents transition into parenthood, especially if there are already signs of couple relationship distress and challenging infant temperaments.

Attending PasP supported parents of highly reactive infants in that through their participation, their relationship and their infants directly benefitted through a positive behaviour change. A reduction in risk of child maltreatment because of improved behaviour implies fewer demands on services managing child protection. The long-term risks for infants with a HRT that include hyperactivity, high anxiety, and autism (Buss & Kiel, 2013; Clifford et al., 2013) also point towards the preventive value of the programme.

Whilst certainly a robust programme, PasP is not without challenges: it is expensive to run considering the involvement of professionals and childcare support, and its duration involves time, effort, planning, and commitment for facilitators and participants. Yet, despite parents’ initial apprehension, because of the duration and good attendance, the retention rate was very high.

5. Conclusions

Salient findings from this research show that when parents are supported, this results in a reduction in conflict occurring in front of their child, and subsequently fewer behavioural problems in the children. An intervention such as PasP, which focuses specifically on the couple relationship, helps the couple to improve their relationship and consider more effective parenting strategies, with the potential of benefitting children’s outcomes in the long-term.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.L., A.A., P.A.C. and C.P.C.; methodology, I.M.L., A.A., P.A.C. and C.P.C.; software, P.A.C.; validation, I.M.L., P.A.C. and C.P.C.; formal analysis, P.A.C. and C.P.C.; investigation, I.M.L.; resources, I.M.L.; data curation, I.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.L.; writing—review and editing, I.M.L., A.A., P.A.C. and C.P.C.; visualization, I.M.L.; supervision, A.A., P.A.C. and C.P.C.; project administration, I.M.L.; funding acquisition, I.M.L. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by HSBC MALTA and Endeavour Scholarships—Malta.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee within the Faculty for Social Well-being, within the University of Malta, on the 21 March 2017, reference SWB/2016.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Permission for accessibility to participants within Well Baby Clinics in Malta was granted through the Primary Health Care division in March 2017. Informed signed consent for participation in the RCT across all stages was given by all participants. And written informed consent was also obtained from the parents for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HRT | Highly reactive temperament |

| SFI | Supporting Father Involvement |

| PasP | Parents as Partners |

| RCT | Randomised Controlled Trial |

References

- Abidin, R. R. (2012). Parenting stress index—PSI-4-SF (4th ed.). Available online: https://www.parinc.com/products/PSI-4 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Aracena, M., Gomez Muzzio, E. A., Undurraga, C., Leiva, L., Marinkovic, K., & Molina, Y. (2016). Validity and reliability of the Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF) applied to a Chilean sample. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3554–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M. H., Arterberry, M. E., & Lamb, M. E. (2014). Development in infancy: A contemporary introduction (5th ed.). Taylor & Francis Group, Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M. H., Putnick, D. L., Gartstein, M. A., Hahn, C.-S., Auestad, N., & O’Connor, D. L. (2015). Infant temperament: Stability by age, gender, birth order, term status and SES. Child Development, 86(3), 844–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. (2008). An evaluation of a new post-separation and divorce parenting program. Family Matters, 78, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Burney, R. V., & Leerkes, E. M. (2010). Links between mothers’ and fathers’ perception of infant temperament and coparenting. Infant Behaviour and Development, 33, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, K. A., & Kiel, E. J. (2013). Temperamental risk factors for pediatric anxiety disorders. Current Clinical Psychiatry, 2013, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, P., Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Draper, L., Mwamba, N., & Hewison, D. (2017). Parents as partners: A U.K. trial of a U.S. couples-based parenting intervention for at risk low-income families. Family Process, 56(3), 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, S. M., Hudry, K., Elsabbagh, M., Charman, T., Johnson, M. H., & The BASIS Team. (2013). Temperament in the first 2 years of life in infants at high risk for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorder, 43(3), 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J. C., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Buckley, C. K., & Davis, E. F. (2009). Are some children harder to co-parent than others? Children’s negative emotionality and coparenting relationship quality. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(4), 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2008). Diverging family policies to promote children’s well-being in the UK and US: Some relevant data from family research and intervention studies. Journal of Children’s Services, 3(4), 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2018). Enhancing parenting effectiveness, fathers’ involvement, couple relationship quality, and children’s development: Breaking down silos in family policy making and service delivery. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 11(1), 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., & Gillett, P. F. (2022). TRUE dads: The impact of a couples-based fatherhood intervention on family relationships, child outcomes, and economic self-sufficiency. Family Process, 61(3), 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynarski, M., & Del Grosso, P. (2008). Random assignment in programme evaluation and intervention research: Questions and answers. Journal of Children’s Services, 3, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M. E. (2002). Coparenting and the transition to parenthood: A framework for prevention. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(3), 172–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3, 95–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein, M. A., & Rothbart, M. K. (2003). Studying infant temperament via the revised infant behaviour questionnaire. Infant Behaviour & Development, 26(1), 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, M., & Cardona, T. (2019). NOIS annual report 2018. National Obstatric Information System, Directorate for Health Information and Research. Available online: https://dhir.gov.mt/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NOIS-Annual-Report-2018.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Glynn, L., & Dale, M. (2016). Engaging dads: Enhancing support for fathers through parenting programmes. AOTEAROA New Zealand Social Work, 27(1–2), 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevenstein, D., Bluemke, M., & Schweitzer, J. (2019). Better family relationships–higher wellbeing: The connection between relationship quality and health-related resources. Mental Health & Prevention, 14, 200160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). The primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, R. Y., Tan, C. S., Lee, S. S. M., Tan, S.-H., Tsai, F.-F., Poh, X.-T., Zhou, Y., Sum, E. L., & Zhou, Y. (2015). Interactive effects of parental personality and child temperament with parenting and family cohesion. Parenting: Science and Practice, 15(2), 92–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, E. Q., Slobodskaya, H., & Gartstein, M. A. (2019). Early temperament as a predictor of child mental health. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(6), 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, C. E. (2017). Understanding the intentions-to-treat principle in randomised controlled trials. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(6), 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, B. T., Teti, D. M., & Feinberg, M. E. (2018). Predicting coparenting quality in daily life in mothers and fathers. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(7), 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, J. P., & Lindahl, K. M. (2011). Coparenting: A conceptual and clinical examination of family systems. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems. Chelsea Green Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, P., Grant, S., Mayo-Wilson, E., Macdonald, G., Michie, S., Hopewell, S., & Moher, D. (2018). Reporting randomised trials of social and psychological interventions: The CONSORT-SPI 2018 extension. Trials, 19, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, H. (2017). Paternal involvement in childcare: How can it be classified and what are the key influences? Families, Relationships and Societies, 6(1), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M. K., Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Gillette, P., & Pruett, K. (2019). Supporting father involvement: A group intervention for low-income community and child welfare referred couples. Family Relations, 68(1), 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (2017). Enhancing father involvement in low-income families: A couples group approach to preventive intervention. Child Development, 88(2), 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S. P., Helbig, A. L., Gartstein, M. A., Rothbart, M. K., & Leerkes, E. (2014). Development and assessment of short and very short forms of the infant behaviour questionnaire-revised. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S. P., Jacobs, J. F., Gartstein, M. A., & Rothbart, M. K. (2010, March 11–14). Development and assessment of short and very short forms of the early childhood behaviour questionnaire. International Conference on Infant Studies, Baltimore, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, S. P., Rothbart, M. K., & Gartstein, M. A. (2008). Homotypic and heterotypic continuity of fine-grained temperament during infancy, toddlerhood, and early childhood. Infant & Child Development, 17, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redshaw, M., & Martin, C. (2014). The couple relationship before and during transition to parenthood [Editorial]. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 32(2), 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M. K. (1981). Measure of temperament in infancy. Child Development, 52(2), 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M. K. (2011). Becoming who we are: Temperament and personality in development. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart, M. K., & Derryberry, D. (1981). Development of individual differences in temperament. In M. E. Lamb, & A. L. Brown (Eds.), Advances in developmental psychology (1st ed., Vol. 1). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suor, J. H., Sturge-Apple, M. L., Davies, P. T., & Cicchetti, D. (2017). A life history approach to delineating how harsh environments and hawk temperament traits differentially shape children’s problem-solving skills. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(8), 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavistock Relationships. (2017). Parents as partners groupwork manual. Tavistock Relationships. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, L. A., Piotrowska, P. J., Collins, D. A. J., Mairet, K. S., Black, N., Kimonis, E. R., Hawes, D. J., Moul, C., Lenroot, R. K., Frick, P. J., Anderson, V., & Dadds, M. R. (2017). Optimising child outcomes from parenting interventions: Fathers’ experiences, preferences and barriers to participation. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheelan, S. (2009). Group size, group development, and group productivity. Small Group Research, 40(2), 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).