Abstract

Cholera outbreaks are prevalent in coastal regions, where hydroclimatic factors play a critical role. However, evidence on their associations with different genotypes remains limited, and global projection remains lacking. We compiled cholera data from EnteroBase and WHO weekly reports covering 110 coastal countries from 1980 to 2022. A generalized additive model was used to examine the associations between hydroclimatic factors and different cholera serotypes and genotypes. We further projected future cholera occurrences for each coastal country under three climate change scenarios from 2025 to 2100. During the study period, Wave 3 of O1 replaced Wave 1 as the predominant genotype of cholera, while cholera O139 remained at low levels and only occurred in Asia. At the country–year level, each 1 °C increase in sea surface temperature (SST) was significantly associated with cholera occurrence (OR: 1.032, 95% CI: 1.023 to 1.040) and Wave 3 of O1 (OR: 1.149, 95% CI: 1.097 to 1.203). Drainage density (m/km2) and coastline ratio (%) were positively related to cholera, with ORs of 1.067 (95% CI: 1.046 to 1.087) and 1.022 (95% CI: 1.019 to 1.027). For future projections, five trend patterns were identified under different emission scenarios, with most countries showing increased cholera risk due to global hydroclimatic changes, peaking under the SSP585 scenario. Our findings reveal associations between hydroclimatic factors and different cholera genotypes and project future cholera risk across coastal countries, thereby providing evidence to inform genotype-specific surveillance and targeted prevention strategies at the global scale.

1. Introduction

Cholera is a severe, dehydrating diarrheal disease with a high fatality rate. Seven global pandemics of cholera have been documented over the past two centuries [1]. Vibrio cholerae genotypes O1 and O139 are responsible for cholera epidemics, which inhabit various aquatic environments including marine and freshwater [2]. It is estimated that up to 4 million cholera cases are reported worldwide annually, leading to a severe global health burden [3], with nearly three-quarters of the cholera cases reported in Africa during the past 10 years located in coastal countries [4,5].

Studies have suggested that hydroclimatic environments govern the distribution and growth of V. cholerae while also contributing to genetic diversity and epidemics [6]. Additionally, growing evidence has suggested that V. cholerae typically increases following unusually warm weather and sea temperature [7]. For instance, one study suggested that a warmer ocean could lead to the aggregation of cholera vectors such as copepods, crustaceans, fish, and waterbirds, thereby increasing the transmission of V. cholerae and prolonging its seasonal abundance [8]. Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) also emphasized the exacerbating impact of climate change on the situation [9]. However, little consensus has been reached on the magnitude of the effect of hydroclimatic factors on cholera, primarily due to the scarcity of long-term analyses and comprehensive global data [10,11]. Moreover, existing evidence is lacking regarding analyses conducted on different cholera serogroups and genotypes or on further projecting the future cholera trend globally.

To bridge these knowledge gaps, we collected the genome data from EnteroBase and the weekly epidemiology report from WHO to explore the associations between hydroclimatic factors and the occurrence of different cholera genotypes among 110 global coastal countries and further projected the future likelihood of cholera occurrence for each coastal country worldwide.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Areas

Coastal countries with a history of cholera were included in the study, which were selected and excluded based on the following criteria: (1) countries with coastlines shorter than one SST grid pixel (0.25 × 0.25 degree), for which no SST grid could be assigned and no reliable ocean temperature could be calculated, such as Jordan and Bahrain, were excluded from the analysis; (2) countries with territories that were less than one total precipitation or humidity grid pixel (0.25 × 0.25 degree), such as Singapore, Bahrain and the Federated States of Micronesia, were excluded; (3) unincorporated territories of countries, such as Puerto Rico, Saint Martin, Pitcairn Islands, etc., were excluded.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. EnteroBase Data, WHO Data and the Definition of Cholera Occurrence

EnteroBase has constructed a biobank containing 8687 isolates of V. cholera El Tor from 1956 to 2022 [12]. Among these isolates, we selected strains grouped under HC400_122, which carry information such as time and location (belonging to the pandemic lineage L2 of V. cholera El Tor), and subjected them to screening and cleaning of epidemiological data and genome data (including removal of outbreak strains with identical sequences and time–location, as well as strains lacking time–location information).

To explore the genomic diversity of V. cholera, we aligned the isolates against the reference genome N16961, identifying 7642 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Using the EToKi tool for alignment and filtering, we excluded SNPs from non-phage and recombination regions, as well as SNPs from read segments not mapped in the reference genome. Based on phylogenetic trees and population genetics methods (BAPS), we defined 9 evolutionary branches and 42 sub-branches, summarized into three major clusters, each with bootstrap support exceeding 99%.

We adopted the Wave classification method and employed a numerical hierarchical naming system, such as subdividing Cluster 1 into Branches 1.1 and 1.2, with Branch 1.1 further divided into sub-branches 1.1.1, 1.1.2, and so forth, a method which not only maintains backward scalability but also possesses forward compatibility [13]. Based on this classification method, we divided the total genome data into cholera O139 and cholera O1, as well as the 1–3 Wave of cholera O1 (1.X.X for Wave 1, 2.X.X for Wave 2, and 3.X.X for Wave 3). Ultimately, according to the study period, we retained 1983 genomes, covering 110 countries from 1980 to 2022.

This study further collected the weekly epidemiology reports of the WHO from 1980 to 2022 and extracted information on the time and country of cholera incidences around the world [14]. Notably, the time and location of weekly epidemiological reports and EnteroBase data were voluntarily uploaded by countries or laboratories and were not mandatory. Therefore, combining these two databases allows us to link epidemiological trends with underlying genomic features, thereby enhancing the robustness and interpretability of the analysis and providing a more comprehensive representation of global cholera incidence trends. In this study, cholera was considered to have occurred in a given country and time period if either a WHO report or an EnteroBase record was available for that country and time. However, considering that the WHO data did not provide the genome information corresponding to a cholera report, the stratified analysis by genotype in this study was only based on EnteroBase records.

2.2.2. Hydroclimatic and Socioeconomic Data

We also obtained the hydroclimatic data from several databases covering the period from 1980 to 2022, including SST, precipitation, humidity, length of coastline and the drainage density (Supplementary Material S1), as well as the social factors such as the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and population density for each coastal country (Supplementary Material S1). Additionally, we further collected the future scenarios of these factors (Supplementary Material S1) under three climate change Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), including SSP126 (represents a scenario where humans choose sustainable, low-carbon lifestyles, resulting in a decrease in global warming by 2100), SSP585 (means high emissions, rapid population growth, increased fossil fuel consumption, and worsened air pollution, leading to relentless global warming) and SSP370 (which is considered moderately placed between SSP126 and SSP585), up to 2100.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Relationships Between Hydroclimatic Factors and Cholera Occurrence

To investigate the potential impact of hydroclimatic and socioeconomic factors on cholera occurrence, this analysis constructed a general additive model (GAM), where the observation (Y) represented whether cholera occurred or not. Considering the subsequent prediction of different SSP scenarios, we set the binomial as the distribution and logit as the link function to estimate the odds ratio (OR) for each factor (Equation (1)):

where represents the intercept. is the sea surface temperature of country i in year t with regression coefficient . means the natural logarithm of GDP with coefficient . indicates the population density of country i in year t, while and are defined as the drainage density and coastline percentage of country i. Since the effects of relative humidity and total precipitation on cholera are often non-linear, the penalty smoothing spline functions and are used to fit the effects of relative humidity and total precipitation in country i and year t, respectively, with the df2 and df3 set as 3. We included , the unstructured random effects for each year t of country i, to account for the year random effect. Similarly, the random effect term of countries is indicated by . Furthermore, for the total cholera occurrence, we estimated the impact of those factors on the occurrence of cholera O139 and cholera O1, as well as Waves 1–3 of cholera O1, which was based on our genome analysis.

Due to the prevalence of cholera being higher than 10% (32.7%), we further corrected the origin OR (Equation (2)) [15]:

where are the odd ratios calculated through regression coefficients in our GAM. indicates the global incidence ratio of cholera among study countries from 1980 to 2022. represents the corrected OR and is more approximate of the RR value.

2.3.2. Projection of Future Cholera Trend

Using the yearly SST, relative humidity, total precipitation, GDP and population density output from each SSP scenario for the future, we calculated the possibility of cholera occurrence per year from 2025 to 2100 for each studied country, based on the parameters in the historical association (Equation (1)).

2.3.3. Sensitive Analysis

Given that several cholera records were attributed to population migration, where isolates share a common ancestor with recent strains from distant locations, such occurrences may introduce bias into our model estimates. For instance, the 2010 cholera outbreak in Haiti was caused by Nepalese peacekeeping troops of the United Nations after the earthquake. Therefore, we removed such cholera incidences that were clearly confirmed to have been caused by military action or aid and made further estimates. We also changed the df of relative humidity and total precipitation in the range of df from 2 to 5.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

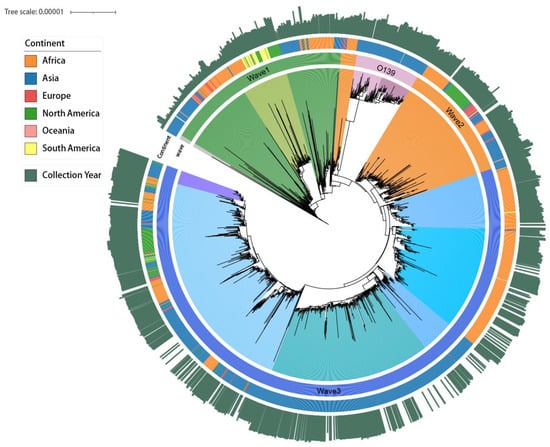

In this study, a total of 5069 strains were collected from EnteroBase between 1956 and 2022. After excluding duplicate bacterial strains, these were categorized into cholera O1, cholera O139, and O1 Waves 1–3 (Figure 1). According to the study period (1980 to 2022), 2554 strains were further selected for subsequent analysis after supplementing the missing upload time of some strains based on genetic similarity and excluding strains with reported times that did not match their genetic characteristics (74 strains). The highest number of strains was from Asia, reaching 1287 (50.39% of the total), followed by Africa (876 strains, 34.30% of the total). For specific strain information, please refer to Supplementary Material S2.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood tree of the seventh pandemic cholera strain, 1956–2022. The length of the collection year is the distance between the other strains and the earliest strains in 1956.

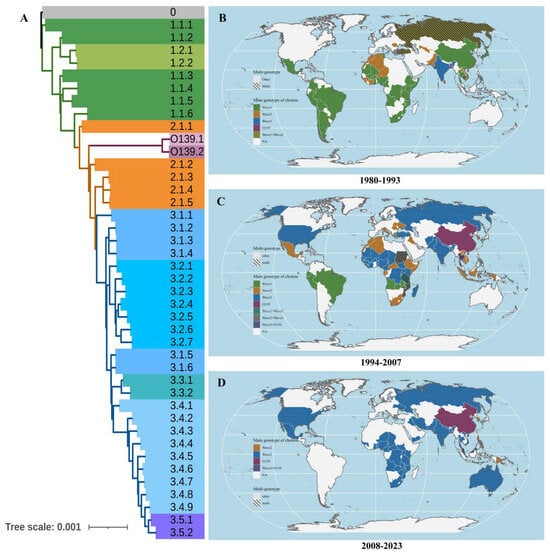

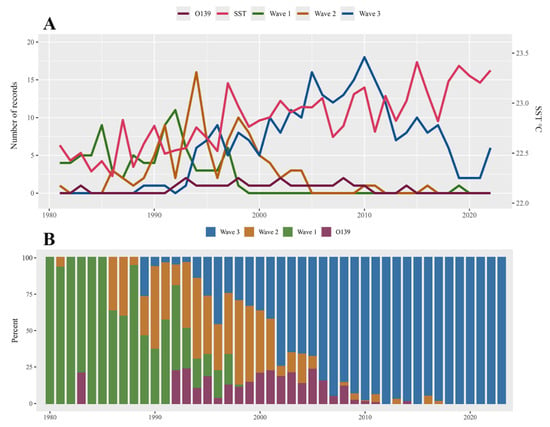

During our study period, after first emerging in the Bay of Bengal, Wave 3 gradually replaced Wave 1 of O1 as the most widespread and predominant genotype of cholera in Africa, Asia, and North America (Figure 2 and Figure S1), while cholera O139 remained at low levels and was observed only in Asia, particularly in China (Figure 3B). Additionally, the average SST of each country showed a fluctuating upward trend.

Figure 2.

The global distribution of different V. cholera genotypes around the world, 1980–2022. (A): The different genotypes of V. cholera; (B): The main genotypes of V. cholera around the world, 1980–1993; (C): The main genotypes of V. cholera around the world, 1994–2007 (D): The main genotypes of V. cholera around the world, 2008–2023. Note: The different colors above represent the cholera genotypes recorded most frequently in a certain country during a certain period, while the shading indicates an equal number of records for two or more genotypes.

Figure 3.

The trends in the number of records, proportion, and sea surface temperature of cholera O1, cholera O139, and Waves 1–3 of cholera O1 globally from 1980 to 2022; (A) The trends of records number of main genotypes of V. cholera, as well as sea surface temperature; (B) The percentage composition of main genotypes of V. cholera.

For a more detailed analysis, subtypes 3.1 to 3.2 of Wave 3 were primarily distributed in Africa (498 strains, 81.77%), and subtypes 3.3 to 3.5 mainly occurred in Asia (831 strains, 70.36%) (Figure 3B). Moreover, the primary pathogens causing cholera in Europe were Wave 3 (42 strains, 41.58%) and Wave 2 (54 strains, 53.47%) of cholera O1 (Figure S1A). For South America, the main pathogen was Wave 1 of O1, while the cholera occurrences have consistently remained at a low level in Oceania (Figure S1B).

3.2. Associations Between Hydroclimatic Factors and Cholera Occurrence

We identified a significant positive relationship between SST and cholera occurrence (Table 1). Specifically, we estimated that each 1 °C increase in sea surface temperature was associated with increased odds of cholera incidence, with an odds ratio of 1.032 (95% CI: 1.023–1.040). Likewise, for total cholera, the occurrence of cholera O1 demonstrated a positive relationship with SST increment (OR: 1.062, 95% CI: 1.035 to 1.091). For Waves 1–3 of cholera O1, we observed that rising SST was associated with a higher risk of Wave 3 (OR: 1.149, 95% CI: 1.097 to 1.203). Furthermore, we observed a negative association between SST and the risk of cholera O139 (OR: 0.787, 95% CI: 0.687 to 0.901), while no significant impact of SST on Wave 1 and Wave 2 was found (Table 2).

Table 1.

The impact of hydroclimatic and social factors on the occurrence of cholera, cholera O1 and cholera O139.

Table 2.

The impact of hydroclimatic and social factors on the occurrence of cholera O1 Waves 1–3.

We also found a non-linear association between total precipitation and cholera occurrence (Figure S2). Specifically, the impact of precipitation on cholera occurrence exhibited an overall inverted U-shaped pattern between 0 m and 0.1 m. Within the range of 0 m to 0.05 m, the effect shifted from protective to harmful and gradually intensified with increasing precipitation, while for the 0.05–0.10 m range, the effect demonstrated a decreasing trend. For cholera O1 and Wave 3 of O1, similar inverted U-shaped trends were observed (Figure S3).

3.3. Associations Between Other Covariates and Cholera Occurrence

We observed a significant positive relationship between coastline ratio and occurrence of cholera (OR: 1.022, 95% CI: 1.019 to 1.027), as well as for cholera O1 (OR: 1.028, 95% CI: 1.018 to 1.036) and Wave 3 (OR: 1.067, 95% CI: 1.050 to 1.083). Drainage density was found to be positively associated with cholera (OR: 1.067, 95% CI: 1.046 to 1.087), cholera O1 (OR: 1.089, 95% CI: 1.044 to 1.136), and Wave 2 (OR: 1.106, 95% CI: 1.021 to 1.198) and 3 (OR: 1.222, 95% CI: 1.152 to 1.297). Moreover, we found a negative association between GDP and cholera (OR: 0.859, 95% CI: 0.829 to 0.888), as well as for cholera O1 and Waves 1–3. For population density, our model revealed a significant positive association with cholera and Wave 3 of cholera O1.

3.4. Projection of Future Cholera

The risk of cholera showed strong spatial heterogeneity under three SSP scenarios. Specifically, the risk of cholera was relatively higher in coastal countries of Latin America, the east and west coasts of Africa, the Bay of Bengal and eastern Asia (Figure S4). In contrast, countries in Oceania, Europe, and northern North America demonstrated lower risks.

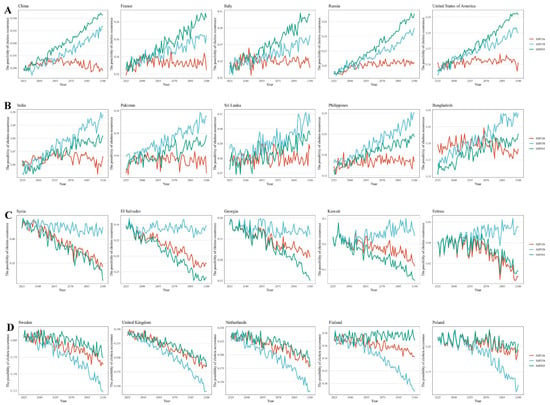

Furthermore, under different emission scenarios, trends in future cholera risk varied among countries, and five distinct trend patterns were identified (Figure 4, Supplementary Material S3). Firstly, we found that the risk of cholera occurrence for most countries gradually increased from 2025 to 2100, with higher risks under the SSP585 scenario, including 48 countries such as China, the United States, and Italy. Secondly, among countries where cholera risk was on the rise, a few exhibited the highest risk under the SSP370 scenario and were mainly situated in Southeast Asia and West Africa such as India, Bangladesh, Philippines, etc. Additionally, several countries showed a decreasing trend in cholera risk. Among them, 11 European countries, including Switzerland, Finland, and Germany, showed the slowest decrease under SSP585. In comparison, 29 countries, such as Guyana, Guinea, and the Republic of the Congo, showed a slight decrease in non-SSP585 scenarios. Finally, a few countries did not exhibit obvious differences across different SSP scenarios.

Figure 4.

The future risk predictions of cholera occurrence in coastal countries worldwide under different scenarios (SSP585, SSP370 and SSP126), including four trend types labeled (A–D). (A). The SSP585 scenario (the green lines) corresponds to the highest risk, and the future risk of cholera incidence increases. (B). The non-SSP585 scenario (the red and blue lines) corresponds to the highest risk, and the future risk of cholera incidence increases. (C). The non-SSP585 scenario (the red and blue lines) corresponds to the highest risk, and the future risk of cholera incidence decreases. (D). The SSP585 scenario (the green lines) corresponds to the highest risk, and the future risk of cholera incidence decreases.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses indicated that our results remained robust across different conditions. Firstly, the results of the sensitivity analyses excluding the isolates that share a common ancestor with recent strains from distant locations were similar to our main findings (Tables S1 and S2). Secondly, adjusting the degrees of freedom for humidity and precipitation did not significantly alter our main results (Table S3).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first global and long-term study to evaluate the associations between hydroclimatic factors and different genotypes of cholera and further project the future cholera trend globally. We summarized the spatiotemporal distribution of each O1 Wave and O139 during 1980–2022. We further observed that higher SST, coastal ratio and drainage density were positively associated with cholera occurrence, especially for Wave 3 of cholera O1. Additionally, we project that a high-emissions scenario could lead to higher risk of cholera in most coastal countries.

Our results demonstrated that Wave 3 gradually replaced Wave 1 and Wave 2 as the most widespread and predominant genotype of O1 around the world during 1980–2022. The phenomenon of Wave 1 being replaced might be attributed to the lack of an SXT/R391 family Integrative and Conjugative Element (ICE) encoding multiple antibiotic resistance [16,17], while the transition from Wave 2 to Wave 3 is considered to be the natural evolution of the strain [13]. In addition, serogroup O139 has been confined to Asia, possibly due to the weaker intestinal attachment capacity of O139 compared to O1, which was discovered by our previous intestinal attachment test [18], making it difficult to spread to other continents by human means like O1.

Similarly to many infectious diseases that dynamically evolve under the influence of multiple hydroclimatic factors [19,20], our results indicate that there are significant associations between SST and the occurrence of total cholera and O1 Wave 3, suggesting hydroclimatic factors like SST drive cholera genotype distributions. Although the potential of hydrogen (pH) of seawater is not suitable for the survival of V. cholerae, the bacteria are more commonly found within plankton blooms [21], copepods, zooplankton [22], and chironomids [23]. The warmer ocean temperatures could promote plankton blooms and encourage these organisms to congregate, thus facilitating the direct transmission of V. cholerae to humans or through intermediaries such as fish and waterfowl [8,24]. This also explained why many cholera outbreaks can be traced back to seafood markets. While the inverse association between O139 and SST observed in this study might be attributed to the fact that O139 occurred only in a few countries, such as China, Bangladesh, and Thailand, limited geographic distribution resulted in a small sample size. Further research could investigate ecological niches, such as O139’s adaptation to lower-salinity estuarine systems less influenced by SST variations.

For the coastal ratio, longer coastlines often meant more complex marine environments, which were more hospitable to V. cholerae [25]. Additionally, a greater coastline ratio implied a higher dependence of a country on the ocean, thereby increasing the opportunities for contact with cholera or its carriers, leading to a higher risk of cholera outbreaks [26]. Moreover, higher drainage density was related to a higher risk of cholera occurrence. This could be attributed to the fact that higher drainage density often indicates more intensive human activities, complicating wastewater management and increasing the risk of cholera outbreaks through the further spread of wastewater.

We also observed an inverted U-shape association between precipitation and occurrence of total cholera and O1, which could be supported by current evidence. For instance, studies in Haiti observed that higher precipitation could increase the risk of cholera outbreak [6], while heavy precipitation was negatively associated with cholera transmission [27]. Several mechanisms could explain the inverted U-shape relationship. For conditions with little precipitation, there were fewer surface and shallow rivers in the natural environment, which narrows the environment for cholera transmission [28]. With the increase in precipitation, appropriate rainfall could increase the risk of raw or treated water being contaminated by wastewater [29]. Notably, even though intense rainfall events could cause surface runoff to flow into streams and rivers, leading to an excess water supply and increased nutrient runoff, the simultaneous increase in river flow could reduce the tidal intrusion of coastal waters carrying plankton into inland water bodies, which could significantly lower the risk of cholera in countries where the marine environment is the primary source of V. cholerae [27]. Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the positive linear association between O139 and precipitation might be attributed to two factors. First, in countries where O139 is distributed, such as China and India, the primary source of V. cholerae is more likely to be freshwater rather than tidal intrusion from coastal waters. Second, different social habits in these countries, such as the use of river water for domestic and sanitation purposes, may also contribute to this association.

Additionally, we found that per capita GDP and population density were also important factors in O1 Waves 1–3 occurrence. Specifically, per capita GDP indirectly reflected a country’s water sanitation level, such as the hygiene of toilets and drinking water [30], and thus exhibited a significant protective effect [31]. In contrast, higher population density often imposed increased contact between individuals, as well as greater sanitary pressure on a country, thereby demonstrating a significant harmful effect [32].

For the projection of future cholera occurrences under different scenarios, most countries demonstrated the strongest increase in cholera risk under the SSP585 scenario. This might be attributed to changes in hydroclimatic factors under high-emission scenarios, such as excessive greenhouse gas emissions leading to increased coastal sea temperatures [8], which had a greater impact on cholera than the protective effects brought by higher economic levels, suggesting that controlling emissions could reduce the risk of cholera. Additionally, targeted interventions in high-risk regions could prioritize adaptive water sanitation under moderate-to-high emission scenarios. However, unlike the main pattern, several developing countries demonstrated the highest risk of cholera occurrence under the SSP370 scenario, not SSP585, and they were mainly concentrated in Southeast Asia and Africa. This difference could be explained by the fact that, under the SSP585 scenario, even though hydroclimatic factors varied more sharply than in the SSP370 scenario, these countries experienced faster economic growth, leading to more advanced water sanitation systems [31]. However, under the SSP370 scenario, GDP grew slowly, but SST and population density continued to rise, thus exhibiting the highest risk of cholera occurrence. Intriguingly, we also estimated a decreasing trend in the risk of cholera occurrence in a few developed countries, with the slowest reduction in the case of SSP585, and the countries were all situated in Europe. The future economic levels of these countries were predicted to be relatively stable, and the decline in population density might decrease the risk of cholera occurrence [32]. The differences between SSP scenarios in this pattern could be attributed to higher risks under high-emission scenarios, caused by factors such as changes in sea temperature and other hydroclimatic factors.

There were several limitations in this study. Firstly, the WHO weekly epidemiological reports and genome data from EnteroBase are reported nationally. Therefore, the individual units of analysis in this study are countries, which makes it difficult to establish more precise correlations between cholera and its influencing factors. Secondly, given the fact that WHO’s weekly epidemiological reports and the EnteroBase data were voluntarily uploaded by countries or laboratories, missing data on cholera information was hard to avoid. Thirdly, natural disasters and conflicts were also factors of cholera occurrence. However, since these factors cannot be predicted for the future, this study did not include them in the analysis. Fourth, due to the difficulty of obtaining accurate and detailed data on population migration via ships, this study only included the annual average population of coastal countries as a covariate and did not account for dynamic population movement. Fifth, by using national-level aggregates for coastal countries, the analysis may overlook significant within-country climatic and demographic variability (e.g., in Andean nations like Peru or Colombia, where up to 50% of the population lives inland, potentially weakening associations with SST and coastal factors).

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate the association between hydroclimatic factors and different cholera genotypes, as well as the future cholera risk for each coastal country. This study offers crucial evidence and predictive information on a global scale and over a long-term period, which is essential for effectively controlling cholera outbreaks now and in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/greenhealth2010005/s1, Supplementary Material S1 (References [25,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] are cited in the Supplementary Material S1); Supplementary Material S2; Supplementary Material S3; Figure S1: The distribution of different serotype and genotype of V. cholerae from 1980 to 2022; Figure S2: The relationships between precipitation and relative humidity with cholera, cholera O1, and cholera O139; Figure S3: The association of Wave 1–3 O1 with precipitation and relative humidity; Figure S4: The spatial distribution of future cholera under three SSP scenarios. Table S1: The impact of hydrological and social factors on the occurrence of cholera, cholera O1 and cholera O139 after removing cholera incidence that were clearly confirmed to have been caused by military action or aid; Table S2 The impact of hydrological and social factors on the occurrence of cholera O1 Wave 1–3 after removing cholera incidence that were clearly confirmed to have been caused by military action or aid; Table S3: The impact of hydrological and social factors on the occurrence of cholera, cholera O1 and cholera O139 after changing the df of relative humidity, and total precipitation in the range of df from 2 to 5.

Author Contributions

B.K., B.P. and H.L. supervised the entire project and designed the study; D.Z., W.W. and H.L. accessed and verified the data; D.Z. performed the main analysis and wrote the original draft; D.Z., W.W., W.Z., J.C., B.P., H.Z., L.T. and H.L. contributed to the discussion and data interpretation and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China [Grant Number: 2022YFC2305305].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data used in this study are anonymous and aggregated, without personally identifiable information, and no ethical approval was required for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors in this study are grateful to those who participated in data collection and the management of this study. All the authors have reviewed the manuscript and approved its submission to this journal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oprea, M.; Njamkepo, E.; Cristea, D.; Zhukova, A.; Clark, C.G.; Kravetz, A.N.; Monakhova, E.; Ciontea, A.S.; Cojocaru, R.; Rauzier, J.; et al. The seventh pandemic of cholera in Europe revisited by microbial genomics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, M.; Izhaki, I. Fish as Hosts of Vibrio cholerae. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Nelson, A.R.; Lopez, A.L.; Sack, D.A. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluda, M.C.M.; Johnson, E.; Robinson, F.; Jikal, M.; Fong, S.Y.; Saffree, M.J.; Fornace, K.M.; Ahmed, K. The incidence, and spatial trends of cholera in Sabah over 15 years: Repeated outbreaks in coastal areas. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebaudet, S.; Sudre, B.; Faucher, B.; Piarroux, R. Cholera in coastal Africa: A systematic review of its heterogeneous environmental determinants. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 208, S98–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavian, C.; Paisie, T.K.; Alam, M.T.; Browne, C.; Beau De Rochars, V.M.; Nembrini, S.; Cash, M.N.; Nelson, E.J.; Azarian, T.; Ali, A.; et al. Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae evolution and establishment of reservoirs in aquatic ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7897–7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Trinanes, J.A.; Salmenlinna, S.; Löfdahl, M.; Siitonen, A.; Taylor, N.G.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Heat Wave-Associated Vibriosis, Sweden and Finland, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1216–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, D.; Memon, F.A.; Nichols, G.; Phalkey, R.; Chen, A.S. Mechanisms of cholera transmission via environment in India and Bangladesh: State of the science review. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 39, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferschmidt, K. A time of cholera. Science 2023, 381, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Saez, J.; Lessler, J.; Lee, E.C.; Luquero, F.J.; Malembaka, E.B.; Finger, F.; Langa, J.P.; Yennan, S.; Zaitchik, B.; Azman, A.S. The seasonality of cholera in sub-Saharan Africa: A statistical modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e831–e839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azman, A.S.; Perez-Saez, J. Cholera and Climate: What do we know? Rev. Med. Suisse 2023, 19, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtman, M.; Zhou, Z.; Charlesworth, J.; Baxter, L. EnteroBase: Hierarchical clustering of 100 000s of bacterial genomes into species/subspecies and populations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 377, 20210240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutreja, A.; Kim, D.W.; Thomson, N.R.; Connor, T.R.; Lee, J.H.; Kariuki, S.; Croucher, N.J.; Choi, S.Y.; Harris, S.R.; Lebens, M.; et al. Evidence for several waves of global transmission in the seventh cholera pandemic. Nature 2011, 477, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL NOTES: CHOLERA = INFORMATIONS ÉPIDÉMIOLOGIQUES: CHOLÉRA. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. Relev. Épidémiologique Hebd. 1963, 38, 440–442. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, K.F. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998, 280, 1690–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garriss, G.; Waldor, M.K.; Burrus, V. Mobile antibiotic resistance encoding elements promote their own diversity. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, R.A.; Fouts, D.E.; Spagnoletti, M.; Colombo, M.M.; Ceccarelli, D.; Garriss, G.; Déry, C.; Burrus, V.; Waldor, M.K. Comparative ICE genomics: Insights into the evolution of the SXT/R391 family of ICEs. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhao, W.; Han, Y.; Chen, J.; Kan, B.; Feng, B. Effects of nucleotide polymorphisms of tcpA gene on environmental adaptability of toxigenic strains of Vibrio cholerae O139 strain. Chin. Prev. Med. 2024, 25, 553–557. [Google Scholar]

- Vezzulli, L.; Colwell, R.R.; Pruzzo, C. Ocean warming and spread of pathogenic vibrios in the aquatic environment. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 65, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandelacy, T.M.; Vincente-González, M.F.; Grillet, M.E.; ColomA-Hidalgo, M.; Herrera, D.; Torres Aponte, J.M.; MarzA¡n RodrA guez, M.; Adams, L.E.; Paz-Bailey, G.; Rodriguez, D.M.; et al. Synchronized dynamics of dengue across the Americas. Sci. Transl. Med. 2025, 17, eadq4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.R. Global climate and infectious disease: The cholera paradigm. Science 1996, 274, 2025–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, A.; Small, E.B.; West, P.A.; Huq, M.I.; Rahman, R.; Colwell, R.R. Ecological relationships between Vibrio cholerae and planktonic crustacean copepods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 45, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broza, M.; Halpern, M. Pathogen reservoirs. Chironomid egg masses and Vibrio cholerae. Nature 2001, 412, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutla, A.S.; Akanda, A.S.; Griffiths, J.K.; Colwell, R.; Islam, S. Warming oceans, phytoplankton, and river discharge: Implications for cholera outbreaks. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 85, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinanes, J.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Future scenarios of risk of Vibrio infections in a warming planet: A global mapping study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e426–e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezzulli, L.; Baker-Austin, C.; Kirschner, A.; Pruzzo, C.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Global emergence of environmental non-O1/O139 Vibrio cholerae infections linked with climate change: A neglected research field? Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 4342–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin de Magny, G.; Murtugudde, R.; Sapiano, M.R.; Nizam, A.; Brown, C.W.; Busalacchi, A.J.; Yunus, M.; Nair, G.B.; Gil, A.I.; Lanata, C.F.; et al. Environmental signatures associated with cholera epidemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17676–17681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, J.; Dawson, T. Climate and cholera in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: The role of environmental factors and implications for epidemic preparedness. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2008, 211, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Moreno, D.; Pascual, M.; Bouma, M.; Dobson, A.P.; Cash, B.A.D. Cholera Seasonality in Madras (1901–1940): Dual Role for Rainfall in Endemic and Epidemic Regions. EcoHealth 2007, 4, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, E.D.; Rodd, J.; Yunus, M.; Emch, M. The role of socioeconomic status in longitudinal trends of cholera in Matlab, Bangladesh, 1993–2007. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Clemens, J.D.; Qadri, F. Cholera control and prevention in Bangladesh: An evaluation of the situation and solutions. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, S171–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Emch, M.; Donnay, J.P.; Yunus, M.; Sack, R.B. Identifying environmental risk factors for endemic cholera: A raster GIS approach. Health Place 2002, 8, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, R.W.; Smith, T.M.; Liu, C.; Chelton, D.B.; Casey, K.S.; Schlax, M.G. Daily High-Resolution-Blended Analyses for Sea Surface Temperature. J. Clim. 2007, 20, 5473–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warszawski, L.; Frieler, K.; Huber, V.; Piontek, F.; Serdeczny, O.; Schewe, J. The Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISI–MIP): Project framework. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 111, 3228–3232. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher, B.; Wang, W.; Michaelis, A.; Melton, F.; Lee, T.; Nemani, R. NASA Global Daily Downscaled Projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Li, P.; Feng, Z.; Yang, Y.; You, Z.; Xiao, C. Which Gridded Population Data Product Is Better? Evidences from Mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inform. 2021, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, X.; Long, Y. Projecting 1 km-grid population distributions from 2020 to 2100 globally under shared socioeconomic pathways. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Sun, F. Global gridded GDP data set consistent with the shared socioeconomic pathways. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.E. Drainage-basin characteristics. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1932, 13, 350–361. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/drainage-basin-characteristics-kovdyx0n78 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.