Abstract

This study investigates the implementation of an attached-growth pilot-scale biofilter for the biological treatment of mixed dairy wastewater derived from real industrial effluents, consisting of equal proportions of raw second cheese whey (SCW) and pudding dessert wastewater (PDW). The biofilter was inoculated with indigenous microorganisms derived from the mixed wastewater stream with initial dissolved Chemical Oxygen Demand (d-COD) concentrations ranged from 1000 to 12,500 mg/L. The removal performance of organic and inorganic components was evaluated at a recirculation rate of 1.0 L/min, resulting in d-COD reductions of up to 92.3% and removal rates reaching 194.6 mg/(L·h). High removal rates were recorded for ammonium (up to 99.9%) and TKN (92.2–98.7%), while nitrate removal varied (29.4–89.3%) and solids removal exceeded 92%. d-COD concentrations of treated effluent consistently met discharge or municipal disposal legislation values, demonstrating the system’s efficiency and stability and proposing it as an ideal solution for wastewater treatment in dairy facilities.

1. Introduction

The dairy and confectionery production units are important branches of the food industry, using raw materials like milk, eggs, flour and sugar, to produce various products such as bakery goods, puddings, desserts, cheese, and yogurt [1]. Large volumes of wastewater are generated alongside these products, characterized by biodegradable organic matter, nitrogen, and other components. Although, confectionery wastewater is less toxic than other agro-industrial effluents, it contains high concentrations of biodegradable materials and other substances, like organic and inorganic forms of carbon and nitrogen, suspended and dissolved solids, oil and grease, starch, and sugar content [2], appointing it unsuitable for direct disposal without treatment. Similarly, milk-derived wastewater, particularly cheese whey (CW) and secondary cheese whey (SCW), contain high levels of organic matter, solids, and salts, and has an acidic pH [3]. Therefore, companies are forced to apply treatment to their produced wastewater in order to comply with the legislation, while illegal uncontrolled discharge of dairy wastewater into natural water bodies leads to eutrophication and unbalanced ecosystems.

In recent years, there has been extensive research into treatment technologies for confectionery and dairy wastewater, including physicochemical [4,5], electrochemical [6,7], and biological [2,8] methods. Another well known approach is the multi-stage hybrid systems [9,10], which combine the benefits of different methods to optimize results. The application of physicochemical coagulation, flocculation, or adsorption often results in the production of large amounts of sludge and insufficient reduction in the organic load [1]. Electrocoagulation methods and membrane reactors are more efficient at reducing pollutants, but they require high energy and maintenance costs [11,12].

The biological approach to dairy treatment has been studied for a long time [11]. Specifically, anaerobic biological reactors have been studied extensively because they effectively biodegrade organic content and generate valuable biogas [13,14]. As for aerobic biological systems, attached-growth systems demonstrate advantages compared to conventional activated sludge processes, such as stability under variable hydraulic and organic loadings, operational resilience, and reduced sludge production. Specifically, biofilters seem to be a promising approach based on attached-growth microorganisms that colonize a solid support medium [3]. This results in the formation of a dynamic biofilm capable of effective degradation. Biofilters present resistance and tolerance under wastewater composition and environmental conditions which are factors that must be taken into account when designing and implementing biofilters [3,15]. In addition, they are relatively simple to operate and maintain, suggesting a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable solution, especially for small- and medium-sized confectionery and dairy plants.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the performance of a pilot-scale attached-growth biological system for the treatment of real mixed dairy wastewater consisting of two distinct effluent streams: second cheese whey and pudding dessert wastewater. This biofilter employed in this study has previously demonstrated high treatment efficiency for second cheese whey, even under elevated organic load [3]. Subsequently, the same system was successfully applied to the treatment of wastewater generated from pudding dessert production, achieving high removal efficiencies for organic load and nutrients [15]. However, to date, the application of an attached-growth biological system for the co-treatment of these two dairy wastewater streams in a single integrated process has not been investigated. The present study addresses this research gap by assessing the feasibility, efficiency, and operational stability of an integrated treatment approach. Co-treatment of the combined effluents is expected to provide significant advantages, including dilution of pollutant loads, improved biodegradability, enhanced process stability, and reduced overall treatment costs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Set Up of Biological Pilot-Scale Attached-Growth Reactor

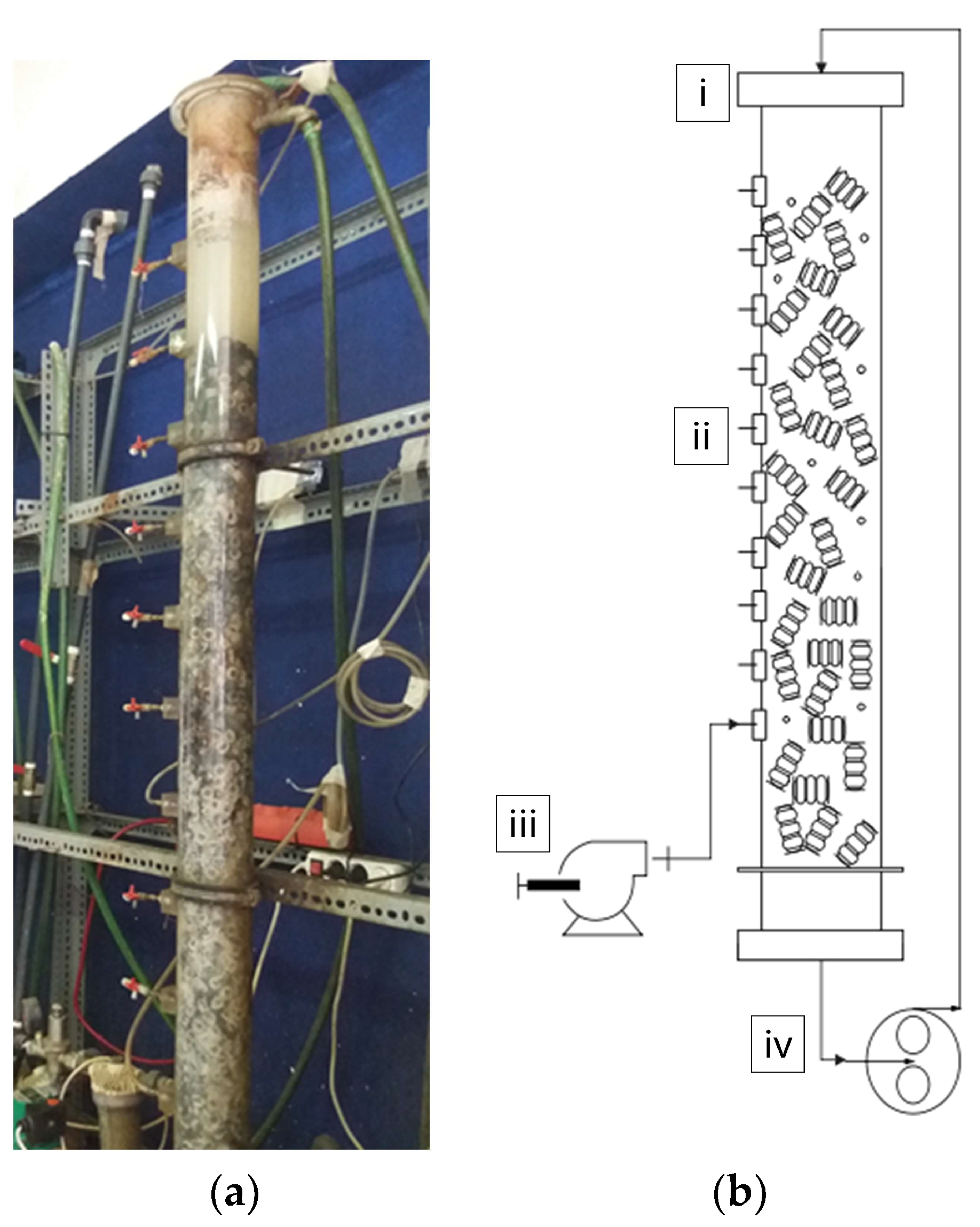

The column pilot-scale bioreactor, constructed from Plexiglas (160 cm height, 9 cm internal diameter, total volume 10.1 L) was positioned vertically on a wooden base and equipped with ten evenly spaced sampling points (Figure 1a). Hydraulic connections, including piping and valves, were located beneath the base to facilitate integration with a recirculation pump, water supply, sewage network, and a mechanical aeration pump. The system was operated in batch mode with recirculation (1.0 L/min) and aerobic conditions maintained via the mechanical air pump installed at the lowest sampling point (Figure 1b). The working volume of the reactor was 7.0 L, with hollow plastic tubes providing a specific surface area of 500 m2/m3 and porosity of 0.8 [3]. The reactor was initially operated in batch mode with mixed dairy wastewater, and following attachment and growth of indigenous microorganisms, experiments were conducted under non-sterile conditions at room temperature without pH control. It should be mentioned that no external inorganic or organic nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, were added during the experiments.

Figure 1.

The attached-growth bioreactor as (a) realistic and (b) schematic presentation ((i) the plexiglass tube, (ii) sampling points, (iii) air pump, (iv) recirculation pump).

2.2. Wastewater Characteristics

The wastewater examined in this research work consisted of equal parts by second cheese whey (SCW) and pudding dessert wastewater (PDW) from a local dairy factory and confectionery industry, respectively, both located near the city of Agrinio, Greece. SCW derives from the production of “feta” cheese, while PDW comprises the washing waters from the equipment cleaning (using only water without cleaning chemicals) during the preparation of traditional Greek Pudding Dessert.

As previously described by Patsialou et al. [15,16], both PDW and SCW were characterized by a high organic load, elevated solids concentration, and a neutral to slightly acidic pH. The wastewater was collected immediately after production and stored at 2 °C in opaque plastic bottles for a few days prior to use. Variations in the composition of SCW and PDW were observed each time the wastewater was collected and attributed to different quantities of water used during the washing process of tanks and pipelines after cheese production and Pudding Dessert processing. Consequently, different proportions of SCW, PDW and tap water were mixed to obtain target d-COD concentrations of the mixed dairy wastewater of about 1000, 2500, 5500, 7500, and 12,500 (corresponding to experiments C1000, C2500, C5500, C7500 and C12,500). Table 1 presents the main characteristics of the mixed dairy wastewater used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Initial concentrations for all parameters investigated for all experiments.

2.3. Analytical Methods and Procedures

Daily samples were collected for analysis during the experiments from the recirculation flow. Physicochemical parameters, including pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and salinity were measured to ensure the correct operation of the biofilter, using a pH meter (Hanna pH 211, with HI1131 electrode; Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA), a DO analyzer (Hanna HI9146, with HI76407 electrode; Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA), and an analog refractometer (Type ORA 1SA; KERN & SOHN GmbH, Balingen, Germany), respectively. All samples were filtered prior to analysis with 0.45 μm-Millipore filters (GN-6 Metricel Grid 47 mm, Pall Corporation (Port Washington, NY, USA)), except for solids and BOD5 determination.

Total Suspended Solids (TSS) and Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) were evaluated using a 0.45 μm pre-weighted membrane filter and with a precise sample of well known volume being filtered. The respirometric Method 5210 D (Continuous Oxygen Uptake), following the principles given by the WTW OxiTop system, was used for BOD5 determination, in the dark, with stable temperature (20 °C) and continuous stirring. Organic components, like dissolved Chemical Oxygen Demand (d-COD) and Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN), were measured following the Closed Reflux, Colorimetric Method 5220 D and the Persulfate Digestion method SM 4500-N C, respectively. Total sugar content was quantified using the DuBois method [17]. Inorganic forms of nitrogen (NO3−-N, NH4+-N), as well as orthophosphates (PO43−) were determined using Method 4500-ΝO3− Β, the Salicylate method [18], and the Ascorbic acid method 4500-P E, respectively. All the aforementioned methods were used as described in ‘Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater’ [19].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biotreatment of Mixed Dairy Wastewater Under Different Initial d-COD Concentrations

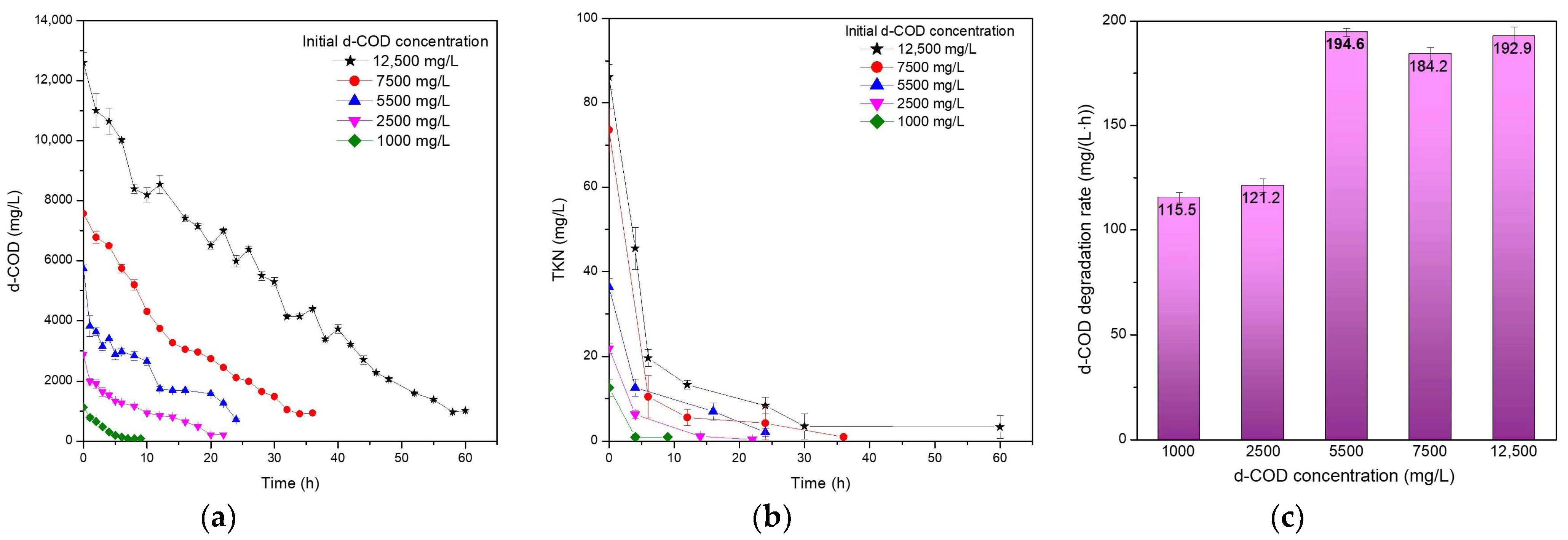

Five different initial d-COD concentrations were examined, approximately 1000, 2500, 5500, 7500, and 12,500 mg/L. Figure 2a presents the d-COD removal over time for all experimental conditions. The shortest operation cycle (9 h) was achieved in the C1000 experiment, while the required processing time was comparable for C2500 and C5500 experiments (20 and 24 h, respectively). A further increase in initial concentration prolonged the operation cycle, reaching 36 and 60 h for C7500 and C12,500, respectively.

Figure 2.

Removal of (a) d-COD and (b) TKN over time and (c) d-COD degradation rate as a function of the initial d-COD concentration for all experimental conditions examined.

Despite the variation in treatment duration, d-COD removal remained consistently high in all experimental series, ranging between 87.4% and 92.3%. Notably, in the C1000 experiment the final d-COD concentration was 88 mg d-COD/L, well below the limit for the disposal of treated wastewater to aquatic bodies (120 mg/L COD, [20]). Comparable findings were reported by Carta et al. [21] and Silva et al. [8], although their studies achieved such low effluent COD concentrations at considerably lower initial d-COD levels. Carta et al. [21] employed an attached-growth bioreactor for real dairy wastewater, a system with notable similarities to the present study, while Silva et al. [8] achieved final concentration below 100 mg COD/L using a hybrid biological anaerobic-aerobic system treating artificial dairy wastewater. It is worth mentioning that results meeting the legislation criteria for safe disposal are not usually reported in the literature, making these methods valuable for industrial applications. For higher initial concentrations, C5500, C7500 and C12,500, the final effluent d-COD values recorded were 724.3, 938.4, and 1021.5 mg d-COD/L, respectively. These concentrations approach the legislative limit for disposal to the sewage system (1000 mg/L COD, [20]).

TKN removal was also high in all cases studied, ranging from 92.2% to 98.7%. Organic forms of nitrogen and ammonia proved to be highly biodegradable by mixed dairy microorganisms, with sharp removal in all experiments within the first hours (Figure 2b). These results exceed the TKN removal that have been recorded by Rezaee et al. [22], despite that the biological configuration presented by them consisted of a combination of aerobic/anaerobic/anoxic steps. Similarly, Hamdani et al. [23], using a vertical-flow fixed bed bioreactor, succeeded the optimum TKN removal of 87.5% after 96 h operating cycle of two anoxic/aerobic phases. This study’s TKN removal rates confirm the system’s high effectiveness, although it is a single-step method.

Regarding the d-COD degradation rate (Figure 2c), the maximum value of 194.6 mg/(L·h) was observed in the C5500 experiment. The degradation rates at C7500 and C12,500 were very close to this maximum, reaching approximately 184 mg/(L·h) and 193 mg/(L·h), respectively. This indicates that beyond the initial d-COD concentration of 5500 mg/L, no appreciable variations in the degradation rate were observed. A maximum degradation rate at an initial d-COD of 5500 mg/L was also reported by Patsialou et al. [15] using an identical bioreactor configuration for PDW treatment. The degradations rates achieved in the present study also fall within the range reported by Tatoulis et al. [3], (i.e., 110–267 mg/(L·h), where the same type of reactor was applied for the treatment of SCW.

Salinity measurements of filtrated samples were also performed at both the beginning and end of each experiment, using an analog refractometer, as a NaCl range (‰). High salinity, up to 9‰, was recorded in the C12,500 experiment, whereas initial salinities in the remaining experiments ranged from 1‰ to 6‰ (Table 1), reflecting the naturally high salt content of SCW. At the end of all runs, salinity was completely removed, even in the case of the highest initial value of 9‰. This reduction appears to be correlated with the substantial removal of solids (Table 2), given the well established interrelation between TDS, conductivity, and salinity [24,25]. Similar observation regarding correlation between TDS removal and salinity reduction was recorded by Velmurugan and Pandian [26], using a microbial consortium treatment for dairy effluents. Also, biological processes contribute to salinity reduction by NaCl removal, like assimilation of dissolved minerals incorporated into new biomass or adsorption of ions Na+ on EPS. Dairy-associated bacteria can produce Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) containing anionic functional groups with strong tendency to bio-sorb Na+. EPS production and composition change under salt stress, supporting bacterial communities to bind dissolved sodium in dairy systems [27,28].

Table 2.

Final removal efficiencies (%) for all investigated pollutants for all experimental conditions.

3.2. Removal Efficiencies of Various Pollutants at the Initial d-COD Concentration of 5500 mg/L

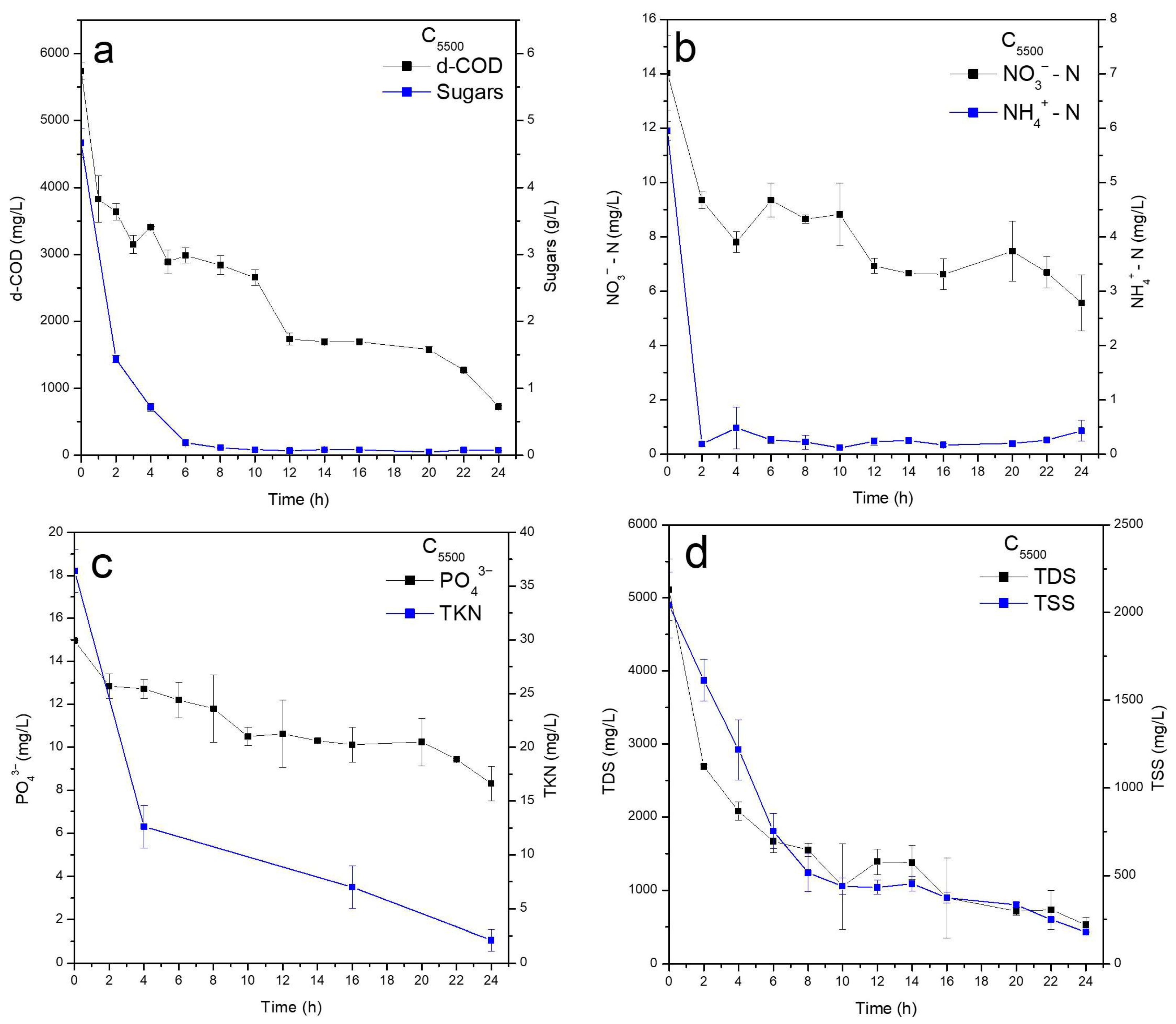

As the degradation rates observed at initial d-COD concentrations of 5500, 7500, and 12,500 mg/L were comparable, the C5500 condition was chosen for further study (kinetic experiments), owing to its high degradation performance and shorter operational cycle. On this basis, kinetic studies of various parameters were conducted. Figure 3a,b show the removal profiles of organic carbon forms (d-COD and sugars) and inorganic nitrogen forms (nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen). Although high removals were achieved for all parameters sugars and ammonium nitrogen were rapidly depleted within the initial hours of the experiment, indicating their higher biodegradability and preferential utilization by the indigenous microbial community. Comparable findings for d-COD and sugar removal were reported by Patsialou et al. [16], in the treatment of raw SCW with marine microalgae and cyanobacteria.

Figure 3.

Removal of (a) d-COD and sugars, (b) NO3−-N and NH4+-Ν, (c) PO43− and TKN, and (d) TDS and TSS for experiment with initial d-COD concentration of 5500 mg/L (C5500).

BOD5 removal was also substantial, reaching 97.1%, confirming the high biodegradability of this mixed wastewater stream. This value exceeds those reported by Patsialou et al. [15], who achieved 86.8% and 78.7% removal during PDW treatment with a biofilter. Organic nitrogen (measured as Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen, TKN) exhibited removal up to 94% (Figure 3c), higher than those recorded by Kushwaha et al. [6], 76.6%, at the same operational time of 24 h using an aerobic sequential batch reactor for artificial dairy wastewater treatment. In contrast, orthophosphate removal was limited to 44.5%, considerably lower than the PO43− removals recorded in the other experimental series, which ranged between 77.1% and 99.3% (Table 2).

Finally, solids removal was consistently high, with values of 91.2% and 89.6% for TSS and TDS, respectively (Figure 3d). These values were comparable across all experiments (Table 2), demonstrating the robustness of the system in achieving efficient solids removal irrespectively of the initial organic loading. Patsialou et al. [15] similarly reports high TSS removal (93–96%) for PDW treatment with the same bioreactor, further confirming system’s reliability.

4. Conclusions

This research study evaluated the degradation efficiency of an attached-growth biological filter for the treatment of mixed dairy wastewater, including second cheese whey and pudding dessert wastewater. The filter was inoculated with indigenous microorganisms derived from the same wastewater stream. The aerobic system was operated in batch mode with recirculation under five different initial d-COD concentrations. In the C5500 experiment, the highest d-COD degradation rate of 194.6 mg d-COD/(L·h) was observed, occurring within the shorter operating cycle of 24 h. Under the same conditions, substantial removals of d-COD (87.4%), BOD5 (97.1%), TSS (91.2%), and TDS (89.6%, respectively, were achieved. A similarly high degradation rate (192.9 mg d-COD/(L·h)) was recorded for the C12,500 experiment, albeit over a longer operation cycle of 60 h, resulting in a d-COD removal of up to 92%.

Importantly, the final d-COD concentrations in all experiments were below the regulatory limit for discharge to the sewage system (COD < 1000 mg/L), with the C1000 experiment achieving an exceptionally low effluent concentration of 88 mg/L, meeting the stricter standards for direct discharge into natural water bodies (COD < 120 mg/L). Also, the total salinity removal works in addition to safe disposal of treated effluents. Thus, the proposed attached-growth biological system can be considered a sustainable and effective treatment solution for small-scale plants handling mixed dairy wastewater streams. The high removal efficiencies achieved for organic and inorganic compounds, combined with the low operational cost of the system, indicate an economically viable and environmentally friendly treatment option for dairy–confectionery industries.

Future research should focus on the further optimization and integration of the proposed biological system with complementary post-treatment processes in order to develop an efficient hybrid treatment scheme. The combination of the attached-growth biofilter with advanced polishing methods, such as adsorption or constructed wetlands, could enhance effluent quality and broaden the range of potential reuse or discharge options. In addition, molecular characterization of the indigenous microbial communities using metagenomic approaches would provide valuable insight into the microbial structure and functional dynamics governing system performance under varying operating conditions. Finally, a comprehensive assessment of all by-products generated during the biological treatment process is essential for the development of integrated waste management strategies and the sustainable valorization of residual streams.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.T. and D.V.V.; methodology, S.P., A.G.T. and D.V.V.; validation, S.P., A.G.T. and D.V.V.; formal analysis, S.P., I.P. and A.G.T.; investigation, S.P. and I.P.; data curation, S.P., A.G.T. and D.V.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and A.G.T.; writing—review and editing, A.G.T. and D.V.V.; supervision, A.G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the local dairy and confectionery factories for their collaboration providing the dairy wastewater.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zajda, M.; Aleksander-Kwaterczak, U. Wastewater Treatment Methods for Effluents from the Confectionery Industry—An Overview. J. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 20, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Pradyut, K.; Mukherjee, J.; Mukherjee, S. Kinetics study of a suspended growth system for biological treatment of bakery and confectionery wastewater. In Advances in Bioprocess Engineering and Technology; Lecture Notes in Bioengineering; Ramkrishna, D., Sengupta, S., Bandyopadhyay, S.D., Ghosh, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 339–348. ISBN 978-981-15-7408-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatoulis, T.I.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Akratos, C.S.; Pavlou, S.; Vayenas, D.V. Aerobic Biological Treatment of Second Cheese Whey in Suspended and Attached Growth Reactors. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 90, 2040–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolakovic, S.; Stefanovic, D.; Milicevic, D.; Trajkovic, S.; Milenkovic, S.; Kolakovic, S.; Andjelkovic, L. Effects of Reactive Filters Based on Modified Zeolite in Dairy Industry Wastewater Treatment Process. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2013, 19, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotoulas, A.; Agathou, D.; Triantaphyllidou, I.E.; Tatoulis, T.I.; Akratos, C.S.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Vayenas, D.V. Zeolite as a Potential Medium for Ammonium Recovery and Second Cheese Whey Treatment. Water 2019, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, J.P.; Srivastava, V.C.; Mall, I.D. Organics Removal from Dairy Wastewater by Electrochemical Treatment and Residue Disposal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 76, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchamango, S.; Nanseu-Njiki, C.P.; Ngameni, E.; Hadjiev, D.; Darchen, A. Treatment of Dairy Effluents by Electrocoagulation Using Aluminium Electrodes. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.F.; Silva, J.R.; Santos, A.D.; Vicente, C.; Dries, J.; Castro, L.M. Continuous-Flow Aerobic Granular Sludge Treatment of Dairy Wastewater. Water 2023, 15, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlyssides, A.G.; Tsimas, E.S.; Barampouti, E.M.P.; Mai, S.T. Anaerobic Digestion of Cheese Dairy Wastewater Following Chemical Oxidation. Biosyst. Eng. 2012, 113, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremouli, A.; Antonopoulou, G.; Bebelis, S.; Lyberatos, G. Operation and Characterization of a Microbial Fuel Cell Fed with Pretreated Cheese Whey at Different Organic Loads. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.H.P. Aerobic Treatment of Dairy Wastewater. Biotechnol. Tech. 1990, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Enander, R.; Barnett, S.M.; Lee, C. Pollution Prevention and Biochemical Oxygen Demand Reduction in a Squid Processing Facility. J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 9, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannoun, H.; Khelifi, E.; Bouallagui, H.; Touhami, Y.; Hamdi, M. Ecological Clarification of Cheese Whey Prior to Anaerobic Digestion in Upflow Anaerobic Filter. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 6105–6111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetsaneas, N.; Antonopoulou, G.; Stamatelatou, K.; Kornaros, M.; Lyberatos, G. Using Cheese Whey for Hydrogen and Methane Generation in a Two-Stage Continuous Process with Alternative pH Controlling Approaches. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3713–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsialou, S.; Politou, E.; Nousis, S.; Liakopoulou, P.; Vayenas, D.V.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G. Hybrid Treatment of Confectionery Wastewater Using a Biofilter and a Cyanobacteria-Based System with Simultaneous Valuable Metabolic Compounds Production. Algal Res. 2024, 79, 103483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsialou, S.; Tsakona, I.A.; Vayenas, D.V.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G. Biological Treatment of Second Cheese Whey Using Marine Microalgae/Cyanobacteria-Based Systems. Eng. Proc. 2024, 81, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, H.; Van Echteld, C.J.A.; Dekkers, E.M.J. Ammonia Determination Based on Indophenol Formation with Sodium Salicylate. Water Res. 1978, 12, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association (APHA); American Water Works Association; Water Environment Federation. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 24th ed.; Lipps, W.C., Braun-Howland, E.B., Baxter, T.E., Eds.; APHA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Government Gazette (GR). Concerning the Disposal in the Marine Area of Keratsini of Wastewater Originated from Industrial Activities in Greater Athens Area, Through the Sewer System and Streams That Are Supervised by OAP. Gazette of the Government of the Hellenic Republic, Issue 582B, 2 July 1979. 1979. Available online: https://www.et.gr (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Carta, F.; Alvarez, P.; Romero, F.; Pereda, J. Aerobic Purification of Dairy Wastewater in Continuous Regime; Reactor with Support. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, S.; Zinatizadeh, A.A.L.; Asadi, A. High Rate CNP Removal from a Milk Processing Wastewater in a Single Ultrasound Augmented Up-Flow Anaerobic/Aerobic/Anoxic Bioreactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 23, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, A.; Amrane, A.; Kader Yettefti, I.; Mountadar, M.; Assobhei, O. Carbon and Nitrogen Removal from a Synthetic Dairy Effluent in a Vertical-Flow Fixed Bed Bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 12, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.S.; Mo, K.; Kim, M. A Case Study on the Relationship between Conductivity and Dissolved Solids to Evaluate the Potential for Reuse of Reclaimed Industrial Wastewater. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2012, 16, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusydi, A.F. Correlation between Conductivity and Total Dissolved Solid in Various Type of Water: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 118, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, L.; Pandian, K.D. Enhancing Physico-Chemical Water Quality in Recycled Dairy Effluent through Microbial Consortium Treatment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurášková, D.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Silva, C.C.G. Exopolysaccharides Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria: From Biosynthesis to Health-Promoting Properties. Foods 2022, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Peng, S.; Zhao, D.; Miao, L. Autotrophic Biological Nitrogen Removal in a Bacterial-Algal Symbiosis System: Formation of Integrated Algae/Partial-Nitrification/Anammox Biofilm and Metagenomic Analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 439, 135689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.