Abstract

In the socio-institutional framework of the Minangkabau society in West Sumatra, Indonesia—where women are typically assumed to have full power over land due to the matrilineal system of land ownership—this study asks: To what extent do women actually exercise power over land ownership and decision-making, and what factors influence this power? Comprising 212 households, a methodical household survey carried out in 2024 across the regencies of Lima Puluh Kota and Padang Pariaman employed quantitative approaches and comparative analysis across rural and peri-urban areas. The survey results confirm the initial hypothesis, showing high rates of land ownership among women in West Sumatra, largely attributed to the matrilineal system. Land ownership by itself, though, does not significantly increase women’s influence in households. Rather, women’s decision-making in Lima Puluh Kota is strongly influenced by other assets such as ownership of cattle, poultry, and electronic items; in Padang Pariaman, time allocated to farming and social events has more influence. These findings underline the complex reality behind nominal land rights and practical empowerment, thereby stressing the need to consider broader socioeconomic factors. The report advises more research on how religious interpretations and modernization are altering West Sumatra’s customary matrilineal customs and women’s empowerment.

1. Introduction

Women’s access to and control over land resources remains significantly lower than men’s globally, with less than 15% of all landholders being women [1]. This gender gap is exacerbated by customary land tenure, the most common form of land governance in many regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Traditional rules and practices, often unwritten and not formally enshrined in statutory law, shape the landscape of land tenure and often reflect patriarchal values [2]. Rural women are particularly vulnerable under customary systems, such as in Rwanda, where customary law often undermines their right to inherit land and imposes restrictions on accessing dispute resolution institutions. Certain groups of women face compounded disadvantages in accessing land rights, such as women in polygamous and unofficial unions, who often lack protection under current legal frameworks [2].

Certain groups of women face compounded disadvantages in accessing land rights. Study by Evans in Senegal women in polygamous and unofficial unions, for instance, often lack protection under current legal frameworks [3]. This legal invisibility makes them particularly vulnerable to dispossession and economic insecurity. Similarly, women in fragile and conflict-affected settings experience heightened land tenure insecurity, which can perpetuate broader conditions of fragility and potentially escalate into violent conflict [2].

Indonesian land ownership is based on customary, Islamic, and civil law. The Agrarian Reform Law gives men and women equal land rights, although customary practices prevail, especially in rural areas [4,5,6,7,8]. In West Sumatra, Indonesia, the matrilineal Minangkabau society’s intricate customary rules and traditions shape this region’s economy and politics [5]. In this matrilineal system, women have traditionally served as the main landowners and have played a crucial role in agricultural activities. The Minangkabau people of West Sumatra follow a matrilineal system where land inheritance, known as pusako tinggi [high heritage] and pusako rendah [low heritage], passes through the female lineage [6,7]. Pusako tinggi denotes hereditary inheritance transmitted through the maternal lineage across generations. It includes common resources such as rice fields, burial places, and tanah ulayat (tribal land), which are collectively held and administered by the clan. Women serve as symbolic stewards to preserve the continuity of these assets within the maternal lineage. Conversely, pusako rendah comprises personally acquired assets—whether obtained through labour or received as a gift—that are inherited in accordance with bilateral Islamic inheritance laws (faraid), permitting sale or transfer at the owner’s discretion.

In this system, daughters inherit land ownership, while sons only have usage rights [6]. This matrilineal–matrilocal land tenure pattern has persisted despite historical prejudices against it [8]. However, the implementation of inheritance often involves male relatives in decision-making [7].

In the Minangkabau matrilineal system, male guardianship especially through roles such as ninik mamak (male elders) and mamak kepala waris (lead the whole community members, to handle, to manage, to observe and to be responsible to the community’s high ancestral inheritance) is crucial in regulating women’s land rights [9]. Although these male relatives are conventionally regarded as guardians responsible for the stewardship of land for the maternal lineage, they frequently wield considerable power over land utilization in practice [9,10]. This situation highlights the “matrilineal paradox,” in which women’s land rights are robust in theory but frequently compromised in practice by established male dominance and decision-making authority.

The studies by Azima (2019), Villamor et al. (2015), and Tamrin et al. (2024) reveal several persistent barriers to women’s economic empowerment in the Minangkabau matrilineal context. Although women may formally inherit land, they often lack the practical control necessary to make independent decisions about leasing, selling, or investing in it. This limited agency also affects their ability to access credit or financial support, as bureaucratic systems typically do not recognize women as legitimate land managers due to their marginal decision-making role [4,10,11].

The study conducted by Idris [12], using a qualitative approach in West Sumatra and data collection through written sources, in-depth interviews, personal observations, case studies, and participant observation, found that decision-making in the Minangkabau society takes place through musyawarah mufakat, a democratic process which takes place in the rumah gadang. Arifin [9] found a paradox in matrilineal societies like Minangkabau and Semende, where women are traditionally given power and control over resources, but men are still able to assert authority and control over these matters. Because of this paradox, males have started political initiatives to change social standards in an effort to recover power and influence.

Although the Minangkabau matrilineal system in West Sumatra is widely acknowledged in academic circles, there is a lack of empirical evidence regarding the impact of land ownership on women’s decision-making power. Many current studies are either conceptual or qualitative in nature, or they are geographically misaligned [13], concentrating on Sundanese and Madurese or other patrilineal contexts, which restricts their applicability to matrilineal societies [14,15,16]. Moreover, prior studies infrequently differentiate the impact of particular asset categories, including poultry, livestock, or mobile technology, on women’s agency. This research fills a significant gap by providing the inaugural quantitative analysis at the household level, utilising data from 212 respondents in both rural and peri-urban Minangkabau regions. The research employs a regression framework based on the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) to illustrate that land ownership does not inherently confer decision-making power, moving beyond the symbolic interpretation of land inheritance. Economic participation via movable assets and time dedicated to off-farm labour serves as a more significant predictor of women’s influence in agriculture and household matters. The specific research objectives are as follows:

- To describe women’s land ownership in farm households and analyse its determinants in West Sumatra’s matrilineal society.

- To determine if West Sumatra women’s land ownership strengthens decision-making.

- To identify other elements influencing farm women’s decision-making, discuss ways to improve women’s status, and compare urban and rural areas.

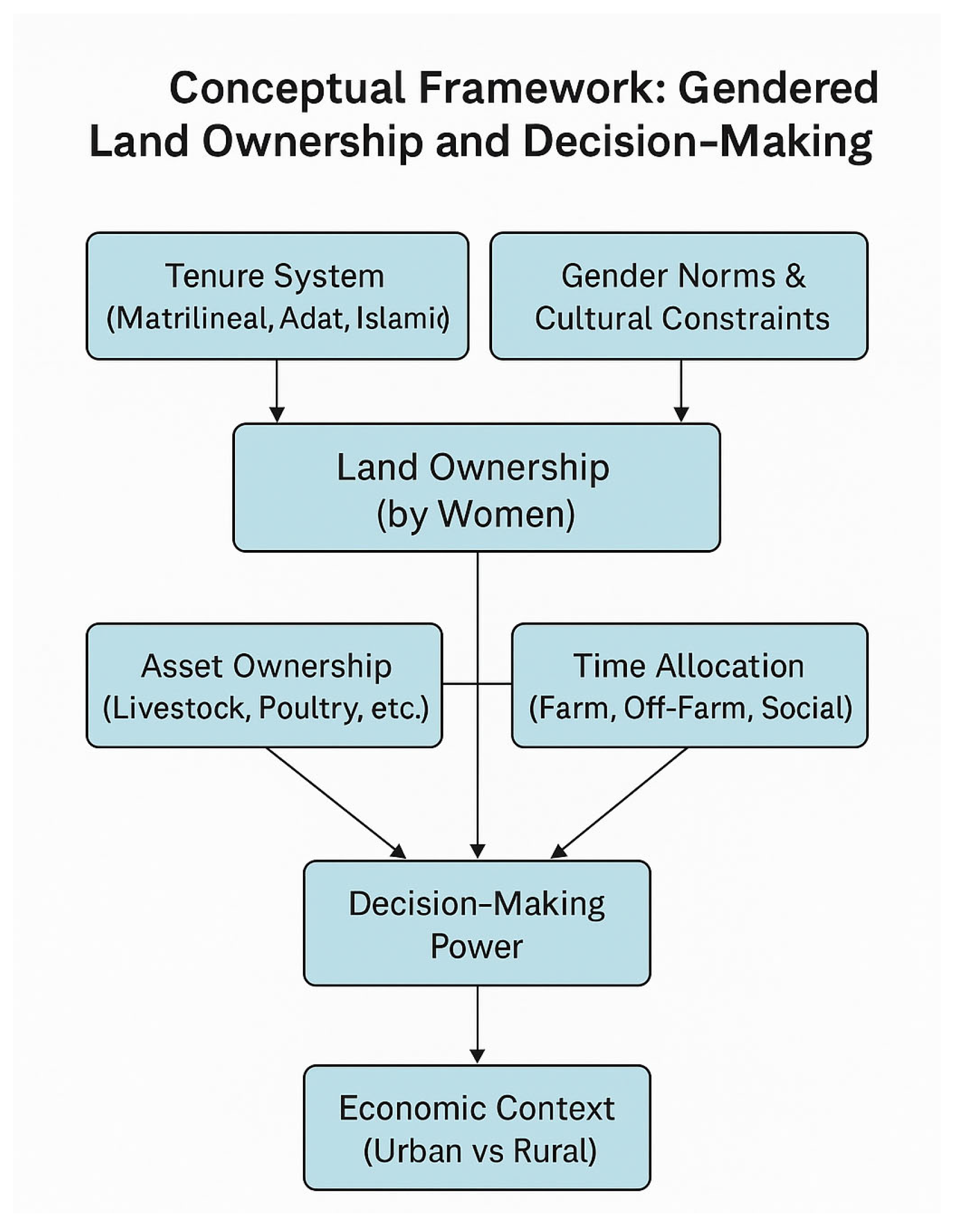

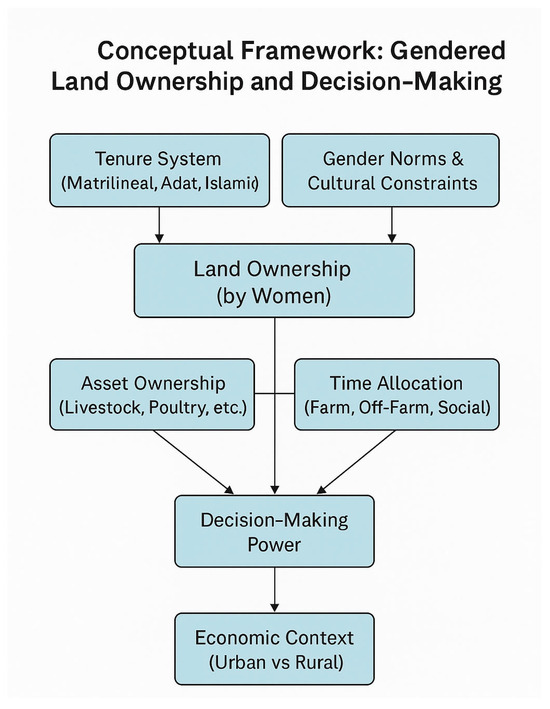

Figure 1 depicts the interrelated factors affecting women’s land ownership and decision-making authority, especially in matrilineal and customary contexts like Minangkabau society. Tenure systems, including matrilineal, adat, and Islamic legal norms, alongside gender norms and cultural constraints, serve as foundational conditions influencing women’s land ownership.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of research.

These structural elements dictate the formal inheritance and ownership of land by women, yet do not ensure their control over it. Following the establishment of land ownership, women’s empowerment is affected by two intermediary elements: asset ownership (including livestock, poultry, or agricultural tools) and time allocation (the distribution of women’s labour across farm work, off-farm work, and social obligations). The two factors significantly affect women’s decision-making power, indicating their ability to control resources and make strategic choices regarding land use and livelihood activities. Ultimately, decision-making authority is influenced by the wider economic context, distinguishing between urban and rural settings, which either limits or enhances women’s practical capacity to exert control over land and associated resources. The framework indicates that although women may have formal land ownership, various social, cultural, and economic factors influence their true empowerment and agency in land-related decisions.

This study employed multiple linear regression models to analyse the relationship between women’s decision-making power and various individual, household, and asset-related factors. The choice of multiple linear regression was appropriate given the continuous nature of the dependent variable (decision-making score) and the need to control for multiple explanatory variables simultaneously. The models were applied separately for the overall sample and the sub-samples from the Lima Puluh Kota and Pariaman regencies to explore regional variations. Standard diagnostic checks for linear regression assumptions, including normality of residuals, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity, were conducted to validate the robustness of the models. Based on the above conceptual framework, independent variables were selected related to asset ownership (land, livestock, poultry, home, phone, vehicle) and time allocation (working on/off farm, child-rearing, rest hours). Furthermore, based on empirical findings from previous studies, educational background was also included as an independent variable.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Kabupaten Lima Puluh Kota is known for its agricultural potential and diverse landscape. The district is a key player in plantation crops and horticulture, with citrus orchards covering 9584.41 ha and producing 39,593.23 tons in 2019. Agriculture forms the backbone of the district’s economy, with coffee, citrus fruits, chilli peppers, and shallots being its major products [17,18].

Lima Puluh Kota Regency is part of West Sumatra’s west–east corridor, which encompasses urban, desa-kota (village-city), and rural districts. Payakumbuh and sections of Harau may have more peri-urban characteristics due to their proximity to urban areas and economic activities [16].

Kabupaten Padang Pariaman is known for its agricultural potential, including food crops, plantations, and horticultural items. With its favourable natural conditions and large land, the district has become a major contributor to the agricultural sector, particularly in rice production and coconut farming. A town surrounded by rural Padang Pariaman Regency, Pariaman is a semi-enclave. With 79% of land utilized for farming, Pariaman’s economy is agricultural.

GRDP, or Gross Regional Domestic Product, is a crucial indicator for distinguishing between rural and urban areas, as it reflects the concentration of economic activity, productivity differences, and sectoral composition. Urban areas generate more economic output due to the concentration of industries, services, and businesses. Higher GRDP is often associated with more urbanized areas, making it a useful metric for classifying regions as rural or urban. It also highlights economic linkages between urban and rural areas. The Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) in Lima Puluh Kota District increased from IDR 17.90 trillion in 2022 to IDR 19.60 trillion in 2023, a rise of IDR 1703.59 billion. Kabupaten Lima Puluh Kota demonstrates a superior GRDP value, with a higher economic growth rate of 4.55% compared to Kabupaten Padang Pariaman’s 3.87% average growth rate. Both districts show positive growth, with the agricultural sector significantly contributing to the GRDP [18].

2.2. Questionnaire Design

A systematic household survey was conducted in 2024 in rural West Sumatra Province, Sumatra, Indonesia. Survey participants were randomly selected using multi-stage sampling. The West Sumatra regencies of Lima Puluh Kota and Pariaman were chosen purposefully.

Second, five villages were randomly selected from these two regencies using government village lists. Third, twenty residences of women were randomly selected in each of the five villages, adjusted to match community size. Our dataset represents West Sumatra regions and includes 212 families. A local team conducted face-to-face interviews in Bahasa Indonesia using standardized questions. All household demographics and economic activities, including agricultural and non-agricultural ones, were collected. Survey questions were adapted from the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) framework to systematically assess dimensions of decision-making authority and land ownership among respondents. The questions included: “Who typically makes decisions? How much input do individuals have? How much do they feel they can participate in decision-making? How much access do they have to important information? How much input do they have in decision-making?” Prior to data collection, the local team of enumerators underwent standardized training on survey techniques, questionnaire content, and the interpretation of essential concepts, such as “decision-making power”, to guarantee uniformity. Training materials based on the WEAI guidelines were disseminated, and simulated interviews were performed for practice. This technique mitigated interviewer bias and ensured standardized data collection procedures across study sites. The local team was directed to explain to respondents that “decision-making” refers to having a significant voice or ultimate influence in agricultural, financial, and household affairs, as delineated in the WEAI framework. The extent of the woman’s involvement in joint decisions was evaluated according to her reported impact on the final conclusion.

In this study, land ownership was measured using a binary indicator (1 = owns land, 0 = does not own land), based on a yes/no self-reported response to the question: “Do you own land under your name or via family inheritance (pusako)?” This approach was chosen for two reasons: first, it reflects how ownership is most commonly understood in local discourse, primarily as formal or customary inheritance entitlement; and second, the survey aimed to cover a broad range of empowerment variables within a limited interview time, necessitating a parsimonious design.

Age, education, family composition, working hours, relaxation hours, child rearing, farm equipment, land ownership, livestock, and mobile phone ownership were surveyed (Table 1). The survey had 16 parts with 4–5 items each. If respondents answered “yes” to an initial question, follow-up subquestions were administered; otherwise, they proceeded directly to the next section. The parameters were selected to capture the gendered dimensions of land access, ownership, use, and investment. Land ownership and decision-making indicators directly reflect women’s control over land. Asset ownership, working hours, and social participation provide insight into women’s economic roles and agency within agricultural households.

Table 1.

Variable description.

Table 2 shows descriptive basic information about respondents. The average respondent age is 44.5 years, ranging from 31 to 59. The data distribution is symmetrical, with a modest skew (0.04). The mean years of schooling is 11.2, with high kurtosis (5.67), implying extreme values. The average household size is 4.75, ranging from 4 to 7. Generally, respondents sleep/rest 7.58 h per day (low skew and kurtosis). The respondents labour 4.18 h off-farm and 5.16 h on-farm, demonstrating diversified livelihoods. Despite the low mean number of livestock hours (0.79), the considerable standard deviation and range indicate variety in livestock ownership. The standard deviation of 3.82 indicates substantial variability in child-rearing activities, while social activity participation is more uniform.

Table 2.

Basic information of respondents.

3. Results

3.1. Factors Influencing Land Ownership in West Sumatra

Table 3 presents asset ownership among respondents. The survey revealed that 175 respondents owned land. There were high ownership rates for homes (96%) and mobile phones (91%), while poultry (46%) and livestock (38%) had lower ownership rates. The high percentage of women landowners was attributed to the unique matrilineal system practised by the Minangkabau ethnic group. This system, the largest surviving matrilineal society globally, grants women significant rights and responsibilities in land ownership and management. Key contributing factors include matrilineal inheritance, matrilocal marriage customs, women as effective heads of households, cultural norms, and legal recognition. In contrast, other regions in Indonesia often follow patriarchal systems or customary laws that limit women’s land ownership [4].

Table 3.

Asset ownership of respondents.

Table 4 presents the results of a linear regression analysis exploring the determinants of women’s land ownership in West Sumatra. Land ownership serves as the dependent variable, while the independent variables reflect individual and household characteristics that may influence women’s ability to own land. Land ownership is a significant aspect of the matrilineal concept in this study. The independent variables included age, education, household size, asset ownership, labour time allocation, and social activity, aiming to capture a wide range of socio-economic factors potentially affecting women’s decision-making. While some variables were not statistically significant, their inclusion allowed for a comprehensive analysis. Working on-farm hours exhibited a positive and statistically significant relationship with land ownership (p = 0.04840). Time allocating to working with livestock demonstrated a statistically significant positive correlation (0.01039), indicating that livestock time allocation significantly influences land ownership in West Sumatra. Studies show that women spend more total hours working when both paid and unpaid work are considered. Social activity among women in West Sumatra likewise had a significant effect on land ownership (0.00281). By contrast, age had no significant effect on land ownership; education also showed no significant relationship. Household size had a positive estimate. Livestock ownership had a correlation with land ownership but was not significant, while child-rearing had no significant association. The model’s residual standard error was 0.3878 on 158 degrees of freedom, with approximately 18.37% of the variance explained by the model. The adjusted R-squared was 0.101, and the F-statistic was 2.222 on 16 and 158 degrees of freedom, with a p-value of 0.006441, indicating that the model as a whole was statistically significant.

Table 4.

Relationship between land ownership and related factors influencing decision-making.

3.2. Analysis Model of Decision-Making West Sumatra

Table 5 explains the respondents’ scores on decision-making across various variables. Land, working off-farm, and vehicle ownership categories have a perfect score of 16, as each was assessed with four questions: “Who has decision-making power? How much participation do you have in the process of decision-making? How do you access information about decision-making in this area? How is income from this decision process used?” Livestock, working on-farm, and farm equipment have a perfect score of 20, based on five questions: “Who typically makes decisions? How much input do individuals have? How much do they feel they can participate in decision-making? How much access do they have to important information? How much input do they have in decision-making?”

Table 5.

Respondents’ scores on decision-making by variable.

The mean score represents the average score for each variable across all respondents, calculated by summing all variable scores and dividing by the number of respondents. A variable’s mean score indicates the level of decision-making capacity or engagement. For instance, “Land” averaged 10.95; “Poultry,” 6.606; “Livestock,” 4.42; “Working on-farm,” 8.24; “Working off-farm,” 6.76; “Farm Equipment,” 6.08; and “Vehicle,” 5.33.

Low mean scores suggest inadequate decision-making ability for a variable among respondents. For example, the low mean score of 4.42 for “Livestock” indicates that respondents had limited involvement in livestock-related decisions. These interpretations are not based on specific survey questions but rather represent an interpretative analysis based on abductive reasoning, drawing on the patterns observed in the quantitative data and supported by the existing literature on gender roles and decision-making in matrilineal and rural agricultural contexts. While the structured questionnaire focused on measurable factors such as asset ownership and time allocation, broader socio-cultural influences, such as traditional norms limiting women’s agency or resource constraints, were inferred from the survey patterns and prior qualitative studies on Minangkabau society.

3.2.1. Linear Regression of Decision-Making in West Sumatra

Table 6 shows how all independent variables affect decision making. Based on the results, land ownership did not have a significant correlation with decision-making in West Sumatra (0.88820). Women in West Sumatra, particularly among the Minangkabau ethnic group, have land ownership rights but lack decision-making power due to traditional gender roles and customary law. Poultry and animal ownership are positively correlated (p-value: 8.94 × 10−7 *** and 0.00675 **). This suggests that livestock and poultry are key assets for decision-making power among women in West Sumatra. Decision-making is also strongly linked to home ownership (0.02340) and electronic device ownership. Rural property ownership is affected by legal, cultural, and economic factors. Sleep time allocation has a significant negative relationship with decision-making (0.00379). Rural women may have less time for activities outside their daily routines; the correlation between sleep and rest hours reveals a negative and statistically significant relationship (p < 0.05), suggesting that an overabundance of rest may be linked to diminished activity or efficacy in decision-making processes.

Table 6.

Linear regression of decision-making.

Time allocation for working on-farm and off-farm shows a positive and significant relationship (0.01788 and 0.00702), indicating that reduced time in agriculture and greater decision-making authority may serve as mediators. This study found that age and education were not significantly linked with decision-making (−0.66683 and 0.84547).

Social activity was positively but not significantly associated. Farm equipment ownership had a negative estimate (−1.917) with a borderline p-value (0.05670), suggesting a possible 10% association. The statistical output indicates that the residual standard error (RSE) of the model is 0.1487, which reflects the average deviation of observed data points from the predicted regression line, measured in the units of the dependent variable. The model has 194 degrees of freedom, which is the number of observations minus the number of estimated parameters. The multiple R-squared value is 0.3312, indicating that approximately 33.12% of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the model. After accounting for the number of predictors, the adjusted R-squared is 0.2726, providing a more reliable measure of the model’s performance. The F-statistic of 5.65 with 17 and 194 degrees of freedom and a p-value of 2.629 × 10−10, indicates that the model is highly significant, with predictors collectively exerting a substantial influence on decision-making."

3.2.2. Linear Regression of Decision-Making in Lima Puluh Kota

Table 7 shows the results of a linear regression analysis from Lima Puluh Kota Regency regarding factors influencing decision-making among women. The table presents the results of a linear regression analysis on decision-making in Lima Puluh Kota Regency. Among the independent variables, livestock ownership, poultry ownership, and electronic device ownership are significantly correlated with the dependent variable. Specifically, livestock ownership has a positive and statistically significant effect (p = 0.02592, marked as *), indicating that owning livestock contributes to decision-making. Poultry ownership shows a highly significant positive effect (p = 0.00103, marked as **), suggesting an even stronger relationship. Similarly, electronic device ownership is positively associated with decision-making and is also highly significant (p = 0.00333, marked as **).

Table 7.

Linear regression of decision-making in Lima Puluh Kota Regency.

On the other hand, several variables do not show statistically significant relationships with decision-making, including age, educational level, household membership, farm equipment ownership, home ownership, mobile phone ownership, vehicle ownership, sleep and rest hours, working off-farm, working on-farm, livestock hours, child rearing, social activity, and land ownership. The p-values for these variables exceed 0.05, indicating insufficient evidence to conclude that they significantly influence decision-making within this model.

The statistical output indicates that the model’s residual standard error (RSE) is 0.1431, which reflects the average deviation of observed values from the predicted values. The multiple R-squared is 0.4321, meaning that 43.21% of the variation in the dependent variable is explained by the model. The adjusted R-squared of 0.3129 accounts for the number of predictors and provides a more conservative measure of model fit. The F-statistic of 3.625 and its associated p-value of 4.542 × 10−5 indicate that the overall model is statistically significant, suggesting that the predictors collectively contribute to explaining the variability in decision-making.

3.2.3. Linear Regression of Decision-Making in Pariaman

Table 8 shows the results of a linear regression analysis examining the factors influencing decision-making in Pariaman Regency. The dependent variable is likely related to decision-making abilities, while the independent variables include demographic, ownership, and activity-related characteristics. The overall model is statistically significant, as indicated by the F-statistic (p = 0.002183). However, the adjusted R-squared value of 0.1903 suggests that only about 19% of the variability in decision-making is explained by the model, indicating that other unmeasured factors may also play a significant role.

Table 8.

Linear regression of decision-making in Pariaman Regency.

Key predictors with significant effects include poultry ownership, working off-farm, and sleep and rest hours. Poultry ownership has a strong positive impact on decision-making (p < 0.001), suggesting that households owning poultry may experience greater financial stability or responsibility, enhancing their decision-making capacity. Working off-farm also shows a positive and significant effect (p < 0.05), likely reflecting the benefits of additional income or diverse work experience on decision-making. Conversely, sleep and rest hours have a negative and significant association (p < 0.05), implying that excessive rest might correlate with less active or effective decision-making.

Other variables, including age, education, household size, and various types of asset ownership, such as farm equipment, electronics, land ownership, and vehicles, are not statistically significant in this analysis. This indicates that these factors may have less direct or negligible effects on decision-making in the context of Pariaman Regency. The model highlights the importance of specific forms of economic engagement (like poultry farming and off-farm work) in shaping decision-making outcomes.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Disconnect Between Land Ownership and Decision-Making Power

The regression analysis indicates that land ownership is statistically insignificant in forecasting women’s decision-making authority. This reinforces the notion of the “matrilineal paradox,” wherein women serve as symbolic guardians of land, although decision-making predominantly resides with male relatives, such as ninik mamak or household leaders. The continued dominance of male-led musyawarah (customary deliberation processes) perpetuates patriarchal interpretations of adat, thereby further marginalizing women’s views. This result suggests that while women inherit and legally hold land assets, they are often not the primary decision-makers regarding how the land is used or managed.

Conversely, the largest determinants of decision-making capacity are ownership of productive, mobile assets and labour participation. Ownership of poultry and livestock markedly enhances decision-making scores; utilization of electronic devices further augments decision agency, presumably via enhanced access to information and market involvement. Engagement in off-farm employment and on-farm labour hours indicates economic participation that correlates significantly with empowerment. This illustrates that women’s economic participation, rather than fixed land ownership, is the most effective route to agency. Assets that are immediately controllable, tradable, or utilized for production enhance empowerment more significantly than land that is culturally constrained or governed communally.

The findings of this study clearly show that women’s decision-making power is not determined by the legal status of land ownership, but rather by their control over income-generating assets and productive activities. Thus, focusing solely on legal land rights without ensuring women’s access to and control over productive resources risks reinforcing the existing gender gap in decision-making power. The evidence from this study underlines the importance of promoting women’s access to economic resources and leadership opportunities, rather than relying solely on land rights to achieve gender equity in decision-making.

Lastly, the fact that there is no strong link between education level and the ability to make decisions suggests that formal education alone is not sufficient to overcome the cultural and institutional barriers to empowerment in a matrilineal society.

4.2. Rural vs. Peri-Urban Decision-Making Dynamics

The regression analysis highlights significant differences between urban and rural areas in terms of women’s decision-making. The statistics indicate a distinct geographic disparity in the elements influencing women’s decision-making authority.

In Lima Puluh Kota, a peri-urban environment, women’s decision-making is significantly impacted by the possession of market-related, mobile assets, including poultry, livestock, and gadgets. These findings demonstrate the impact of enhanced market access, service availability, and infrastructure, which empower women to utilize resources autonomously and engage more actively in household economic decisions. Conversely, Padang Pariaman, exemplifying a more rural and agriculturally reliant environment, exhibits a distinct pattern. In this context, time allocation variables, specifically participation in off-farm labour and diminished rest hours, exhibit a stronger correlation with women’s decision-making scores. This indicates that in rural regions, where asset mobility and market access are constrained, labour contribution emerges as the primary avenue to agency.

These trends underscore that empowerment efforts must be spatially adaptive—what facilitates agency in peri-urban regions (resources and technology) may differ from that in rural areas (labour and time utilization dynamics).

4.3. Academic Contribution to Scientific Knowledge

This study provides a unique empirical contribution to the understanding of gender and land tenure systems by presenting the first household-level quantitative examination of women’s land ownership and decision-making within a matrilineal society in Indonesia. This research offers substantial data from the Minangkabau community, the biggest extant matrilineal society, contrasting with the predominant literature on women’s land rights that emphasizes patrilineal contexts or theoretical discourse. It contests the dominant belief that land inheritance automatically confers authority on women, demonstrating that mobile assets and labour involvement are more substantial indicators of empowerment. This study enhances the academic literature by showing that women’s decision-making authority is more accurately predicted by asset ownership and time allocation than by formal land ownership in matrilineal contexts. Decision-making is particularly effective when women possess productive movable assets like poultry (p = 8.94 × 10−7) and participate in off-farm labour activities (p = 0.00702), highlighting the significance of economic engagement and control over income-generating assets. The results indicate a spatial disparity: in rural regions (Padang Pariaman), decision-making is more significantly affected by labour time factors, especially off-farm work involvement and diminished rest periods, which illustrate women’s direct commitment to household sustenance. Conversely, in peri-urban regions (Lima Puluh Kota), decision-making is more effectively associated with varied asset ownership, including poultry, livestock, and electronic gadgets, highlighting the increasing influence of market access and technology resources on women’s agency. These findings challenge fixed concepts of land empowerment and provide novel empirical insights into the interplay between gender, tenure systems, and economic transition in Southeast Asia. Additionally, employing a multivariable regression model based on the WEAI framework enhances methodological techniques to accurately assess rural women’s agency at the intersection of customary, Islamic, and contemporary land systems.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the disconnect between women’s land ownership and decision-making power within the matrilineal Minangkabau society of West Sumatra, using quantitative approaches and household survey data from two regencies: Lima Puluh Kota and Padang Pariaman. The findings confirmed high rates of women’s land ownership, attributed to the matrilineal system. However, land ownership alone did not significantly enhance women’s decision-making authority over household and agricultural matters.

Although women inherit and legally hold land assets, decisions on how to use and manage the land are dominated by men. On the other hand, it was found that women’s decision-making power is strengthened by ownership of mobile assets, including poultry, livestock, and gadgets, and by labour participation. Therefore, it is desirable to promote women’s access to mobile assets and their engagement in the labour force.

The comparative analysis between Lima Puluh Kota (a peri-urban area) and Padang Pariaman (a rural area) revealed differences in the factors influencing women’s decision-making power. In Lima Puluh Kota, ownership of assets such as livestock, poultry, and electronics was more strongly associated with decision-making capacity, whereas in Padang Pariaman, time allocation to off-farm work and resting hours played a more significant role. These differences should be understood in the context of the two specific study areas and not generalized to all urban and rural settings in West Sumatra or Indonesia.

The results indicate that land titling reforms alone are insufficient to promote meaningful empowerment for women in matrilineal systems. Although formal land ownership rates among women are high—particularly through inheritance under customary law—this does not translate into significant control over land use or strategic decision-making. This gap is largely attributable to patriarchal interpretations of adat and male-dominated musyawarah processes, which continue to dominate local land governance structures. To address this, policy interventions must go beyond formal legal recognition and support women’s access to productive, movable assets such as poultry, livestock, and mobile devices, which have demonstrated a stronger link to agency. Additionally, investing in initiatives that expand women’s participation in off-farm labour will enhance their economic autonomy and bargaining power. Equally important is the need to establish participatory land governance mechanisms that ensure women’s voices are included in customary decision-making forums. Finally, land policy should promote the disaggregation of land rights, including use, control, and transfer, within national surveys and land administration systems to more accurately reflect the realities of women’s tenure security and functional empowerment.

This study provides important insights into women’s land ownership and decision-making power in the Minangkabau society of West Sumatra; however, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the survey design primarily focused on household-level dynamics and day-to-day land use decisions, and did not capture strategic land governance processes such as land subdivision, leasing, or inheritance negotiations, which often involve extended family members living outside the immediate household or region. Second, while differences between Lima Puluh Kota and Pariaman regencies were observed, the study’s findings should not be generalized to a broader urban–rural dichotomy, as only two areas were included, and both have unique socio-economic and cultural characteristics. Third, although Islamic inheritance practices (faraid) may influence women’s land rights over time, this study did not directly measure respondents’ perceptions of religious influences on customary land ownership. Thus, any conclusions regarding the interaction between Islamic law and adat practices must be interpreted cautiously and supported by external literature rather than primary data.

A key methodological limitation of this study lies in the use of a binary land ownership variable. While this approach was analytically convenient and aligned with how respondents commonly interpret landholding (especially under pusako rights), it fails to unpack the multiple dimensions of tenure embedded in the concept of land ownership. In reality, individuals may possess rights of use without transfer, or management without the ability to sell or mortgage. The use of a binary “yes/no” variable therefore masks important variations in land control, authority, and security. This may partly explain why land ownership was not significantly correlated with women’s decision-making power, because not all forms of “ownership” confer the same level of agency. Future research should address this issue by employing a multi-item or disaggregated scale to measure distinct rights within the land tenure bundle, such as control over use, investment, transfer, or leasing decisions. This would allow for a more precise understanding of which dimensions of land rights matter most for women’s empowerment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.N. and A.M.; methodology, B.N. and A.M.; software, B.N.; validation, B.N. and A.M.; formal analysis, B.N.; investigation, B.N.; resources, B.N. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.N.; writing—review and editing, A.M.; supervision, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. And The APC was funded by Atsushi Matsuoka.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kaaria, S.; Martha, O. The Gender Gap in Land Rights; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, D.M.; Groussard, H.; Khaitina, V.; Shen, L. Women’s Land Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa: Where Do We Stand in Practice? World Bank Group Global Indicators Brief No 23; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R. Gendered struggles over land: Shifting inheritance practices among the Serer in rural Senegal. Gend. Place Cult. 2016, 23, 1360–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamor, G.B.; Akiefnawati, R.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Desrianti, F.; Pradhan, U. Landuse change and shifts in gender roles in central Sumatra, Indonesia. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mutolib, A.; Mahd, Y.; Ismono, H. Gender Inequality and the Oppression of Women within Minangkabau Matrilineal Society. Asian Women 2016, 32, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudi, W.A. Perempuan Minangkabau dari Konsepsi Ideal-Tradisional, Modernisasi, sampai Kehilangan Identitas. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328292441_Perempuan_Minangkabau_dari_Konsepsi_Ideal-Tradisional_Modernisasi_sampai_Kehilangan_Identitas (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Iasra, R.F.; Yaswirman, Y.; Yasniwati, Y. Penyelesaian Sengketa Waris Tanah Pusako Tinggi sebagai Tanah Adat melalui Pengadilan Agama Kelas 1a Padang. UNES Law Rev. 2023, 6, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.E. Our daughters inherit our land, but our sons use their wives’ fields: Matrilineal-matrilocal land tenure and the New Land Policy in Malawi. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2010, 4, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, Z. Matrilineal paradox in Semende and Minangkabau culture. Komunitas 2019, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azima, A. Pemberdayaan Wanita Dan Tanah Adat Minang. Humanisma J. Gend. Stud. 2019, 2, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrin, T.; Afrizal, A.; Asril, A. Women’s Role in Conflict Management of Social Forestry: A Case of Sungai Buluh Village. KnE Soc. Sci. 2004, 9, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, N. Kedudukan Perempuan dan Aktualisasi Politik dalam Masyarakat Matrilinial Minangkabau. Dalam J. Masy. Kebud. Dan Polit. Tahun. 2012, 25, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Song, T.; Luo, X.; Li, X. Clustering of Basic Educational Resources and Urban Resilience Development in the Central Region of China—An Empirical Study Based on POI Data. Reg. Sci. Environ. Econ. 2024, 1, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qanti, S.R.; Peralta, A.; Zeng, D. Social norms and perceptions drive women’s participation in agricultural decisions in West Java, Indonesia. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 39, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supraptiningsih, U.; Jubba, H.; Hariyanto, E.; Rahmawati, T. Inequality as a cultural construction: Women’s access to land rights in Madurese society. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, G.A.; Saptomo, A. Customary Land Tenure Values in Nagari Kayu Tanam, West Sumatra. Cosmop. Civ. Soc. Interdiscip. J. 2022, 14, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Indonesia. Agriculture Indicator 2021. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2022/10/10/6bf975b9cd623dc14c4b1bbc/indikator-pertanian-2021.html (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Katadata. PDRB ADHB per Kapita Kota Padang Rp.84,53 Juta Data per 2023. Available online: https://databoks.katadata.co.id/pdb/statistik/76bba6c1efec973/pdrb-adhb-per-kapita-kota-padang-rp-84-53-juta-data-per-2023 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).