Simple Summary

The Pampas fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus) is a widely distributed canid in Southern South America, inhabiting grasslands, agricultural lands, and human-modified environments. Despite over 150 studies from Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia, information remains fragmented and requires synthesis. This review reveals that the Pampas fox serves as a predator, seed disperser, and scavenger, while facing significant threats, including road mortality, hunting, persecution, and conflicts with domestic dogs. It is also recognised as a reservoir for pathogens affecting humans, livestock, and companion animals, underscoring critical intersections between conservation and public health. By integrating ecological roles, health considerations, and sources of conflict, this review provides a regional synthesis and supports evidence-based management strategies.

Abstract

The Pampas fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus) is a widespread meso-predator in Southern South America, present in grasslands, agroecosystems, and human-modified landscapes. Although numerous studies have examined its diet, parasites, distribution, and behaviour, knowledge remains fragmented without an integrative synthesis. This review compiles over 150 documents from Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia to unify dispersed information. Key findings highlight unresolved taxonomy, population structure, and biogeography (based on genetic, morphological, and phylogeographic data), the species’ ecological roles as a meso-predator, seed disperser, and scavenger, and major threats (including road mortality, hunting, persecution, and interactions with domestic dogs). The Pampas fox also harbours pathogens—including zoonotic agents and those threatening livestock and pets—and is frequently stigmatised as a pest, persecuted without substantiated evidence. By integrating ecological, health, and conflict perspectives, this review provides a regional baseline, reframing its importance and guiding more effective management.

1. Introduction

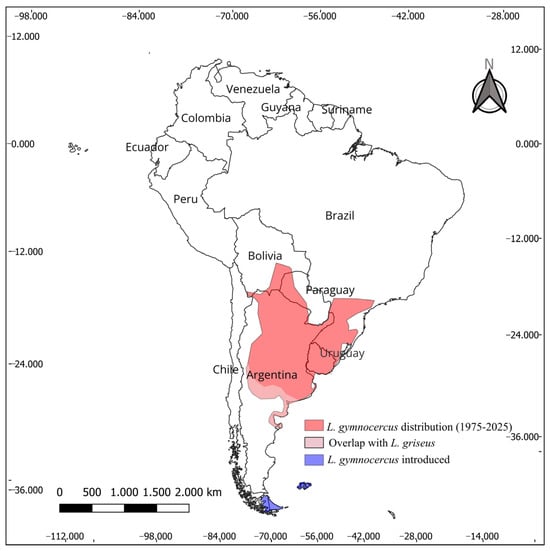

The Pampas fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus) is a medium-sized canid distributed across southern South America (SSA), found in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil, and Bolivia (Figure 1). It inhabits grasslands, scrublands, open woodlands, and anthropogenic habitats such as croplands and pastures, showing marked ecological adaptability [1,2,3]. With reddish flanks, a grey back, and a black-tipped tail, it thrives in the Pampas, Chaco, Espinal, and Monte ecoregions, and regularly overlaps with Cerdocyon thous in open habitats [2]. Its omnivorous and opportunistic diet includes rodents, hares, birds, insects, fruits, carrion, and occasionally small livestock [1,3]. Breeding occurs in spring, with litters typically comprising around three cubs [3]. Despite persistent threats, including hunting, road mortality, persecution by ranchers, and habitat loss, the Pampas fox remains relatively common in the region. It is currently listed in CITES Appendix II and assessed as Least Concern by the IUCN [1,2].

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of Lycalopex gymnocercus (1975–2025) in South America, showing its confirmed range, areas of overlap with L. griseus, and introduced populations in Tierra del Fuego and the Falkland/Malvinas Islands. Data derived from GBIF occurrence records (DOI: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.kyexx4 accessed on 2 December 2025) [4], processed in QGIS (Concave Hull with manual ecological refinement).

Recent contributions have expanded knowledge of its distribution, including new records in eastern Paraguay and observations on mortality, local perceptions, diseases, and potential play behaviour [5]. At the same time, the Pampas fox has been used to illustrate the value of structured research approaches in advancing knowledge of wild carnivores [6]. Together, these findings underscore the importance of ongoing ecological, behavioural, and conservation-focused studies on this resilient yet threatened species. Although ecologically adaptable, the Pampas fox (Figure 2) is often perceived negatively due to its sporadic predation on livestock and its potential role in disease transmission, which can lead to rural conflict and increased hunting pressure. Previous research has mainly addressed isolated topics, lacking interdisciplinary integration. This review synthesises over 150 documents from five South American countries, consolidating information on ecological, health, and human–wildlife conflict. It establishes the first regional baseline from a One Welfare, One Health, and Planetary Health perspective. The Pampas fox exemplifies the complex interplay between biodiversity conservation, rural livelihoods, and disease ecology in South American agroecosystems. Recognising the species as a sentinel, rather than a pest, is essential for guiding future policy development.

Figure 2.

Pampas fox (L. gymnocercus) emerging from native rock formations in Uruguay. A discreet and intelligent carnivore, it embodies both resilience and fragility in changing rural landscapes. Photo: Alexandra Cravino.

2. Materials and Methods

Given its ecological role as a meso-predator, seed disperser, and potential disease reservoir, understanding its interactions with human-modified landscapes is crucial for conservation efforts. To compile and analyse the current body of knowledge on the Pampas fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus), we conducted a systematic literature review focused on ecological, health, and conflict aspects of the species. We structured our analysis around three guiding research questions:

- What is the ecological role and importance of the Pampas fox in South American ecosystems?

- What is the significance of the Pampas fox in the circulation of pathogens at the wildlife–domestic animal–human interface?

- How do human activities and perceptions shape the coexistence between Pampas foxes and people?

The review followed PRISMA guidelines, with searches conducted in Google Scholar, SciELO, and PubMed, prioritising Google Scholar due to its comprehensive coverage of both peer-reviewed publications and grey literature. We used a combination of title-restricted and general keyword searches to maximise coverage. For older studies, we included the Pseudalopex variant within the intitle restriction to specifically target fox-related research and avoid incidental mentions in outdated literature.

- Google Scholar (all years, no citations filter):

- ➢

- Intitle: “Lycalopex gymnocercus”

- ➢

- Intitle: “Pseudalopex gymnocercus”

These filters identified core articles with minimal noise. Using the Pseudalopex variant within the intitle restriction ensured inclusion of older fox-specific studies while avoiding incidental references in outdated literature.

- SciELO and PubMed:

- ➢

- “Lycalopex gymnocercus”

- ➢

- “Pseudalopex gymnocercus”

These searches imposed no title restrictions to capture a broader range of publications. While there was substantial overlap with Google Scholar, PubMed contributed distinct health-focused studies of central relevance. To ensure the inclusion of ecological studies that may have been overlooked due to search filters, we manually reviewed the first 300 results of unrestricted Google Scholar searches for “Lycalopex gymnocercus,” selecting studies that met the eligibility criteria.

Eligibility criteria (Table 1) encompassed academic articles, regional journals, theses, and both qualitative and quantitative studies explicitly focused on the Pampas fox. We only included sources that provided original and analysable information (e.g., diet, health, behaviour, conservation, or ecological patterns). Studies merely listing the species—such as inventories or checklists without analytical depth—were excluded, as were clinical veterinary reports, drug dosages, or surgical techniques not directly relevant to ecology or health.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

This methodology enabled us to assemble a comprehensive, multidisciplinary body of literature on the Pampas fox, spanning ecological, health, and conflict research from both mainstream and local sources. The heterogeneity of methodologies and research emphases precluded a meta-analytic approach. However, the integrative strategy of this review provides a robust basis for identifying patterns, revealing knowledge gaps, and contextualising the ecological and health significance of the Pampas fox in SSA. The review narrowed the extensive corpus of health-related literature (over 80 studies) to retain only those that were representative of the sanitary relevance of L. gymnocercus, such as zoonotic agents, parasitological surveys, or epidemiologically significant case reports.

Conceptual and symbolic figures were designed using Microsoft Word SmartArt and enhanced with custom digital illustrations to convey both clarity and empathy. Beyond their informative purpose, these visuals sought to humanise a frequently misunderstood species, inviting readers to perceive the Pampas fox not merely as a data point, but as a living presence within its ecosystems. The aim was to make the manuscript visually engaging and emotionally resonant, helping readers from diverse backgrounds connect with the species’ ecological and symbolic significance.

3. Results

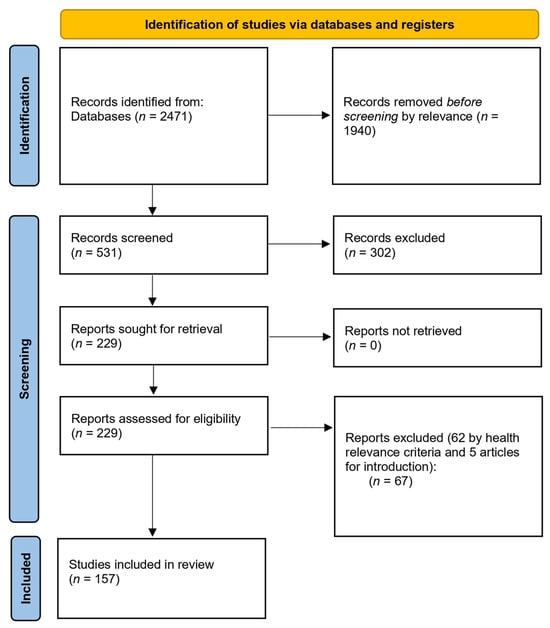

Figure 3 summarizes data inclusion.

Figure 3.

PRISMA flowchart illustrating the identification, screening, and inclusion of studies on L. gymnocercus.

A total of 2471 records were retrieved from Google Scholar, SciELO, and PubMed (Figure 3). After preliminary filtering to remove irrelevant records (n = 1940), 531 were screened in detail. Of these, 229 were retained for eligibility assessment, and 162 met the inclusion criteria. Excluded articles were mainly unrelated to the health or ecological context of L. gymnocercus.

3.1. Fossil Record and Ecology

3.1.1. From Deep-Time to Anatomy: Evolutionary and Morphological Insights

The Pampas fox (L. gymnocercus) has been an integral part of Southern South American (SSA) ecosystems for more than a million years, leaving traces in both ecological and cultural contexts (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Lycalopex gymnocercus (Pampas fox) photographed in the native grasslands of Uruguay, illustrating its natural camouflage and adaptive behaviour within Southern South American ecosystems. This species has coexisted with local realities for over a million years, leaving its mark in both ecological and anthropological contexts. Photo: Alexandra Cravino.

The oldest fossils of the genus Lycalopex date back to the Pliocene (3.0–2.5 million years ago) in north-central Chile, while the earliest record of L. gymnocercus itself belongs to the late Pliocene to early Pleistocene (2.5–1.5 million years ago) in Argentina [2]. Fossil records from Uruguay’s Santa Regina site associate it with extinct megafauna such as Lestodon armatus and Notiomastodon platensis in the Dolores Formation (Late Pleistocene) [7]. At the same time, the Sopas Formation indicates a rodent-based diet in open grasslands [8]. In Argentina, a specimen from Buenos Aires supports the validity of Lycalopex cf. L. ensenadensis, expanding fox diversity in the Lujanian Age [9]. Zooarchaeological findings further reveal its integration into human lifeways. Remains at Río Negro’s Carriqueo site indicate processing and consumption with guanacos, skunks and armadillos [10]. Zooarchaeological records from the Paraná wetlands place it within riparian economies, both as a subsistence and symbolic resource [11]. Assemblages in northeastern Chubut list it among nine carnivore species [12], and faunal analyses in the Limay River basin show its inclusion in diversified pre-Hispanic diets [13].

In that way, paleo-ecological and archaeological evidence places the Pampas fox as both a persistent faunal element and an active participant in long-term human–animal relationships. Remains in cultural contexts indicate that Indigenous groups recognised it as a resource, symbol, or companion, embedding it within ecological continuity and evolving practices [10,11,12,13]. From the Late Pleistocene to the Holocene, it endured climatic shifts, extinctions, and cultural transformations—emerging as a resilient cohabitant of human landscapes and a quiet witness to South America’s ecological history (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Chronological integration of paleo-ecological and archaeological records of L. gymnocercus in southern South America (BsAs = Buenos Aires, Argentina).

Genetic and phylogeographic studies mirror this deep-time continuity, revealing a lineage shaped by evolutionary legacies and contemporary pressures. Cytogenetic analyses define its karyotype as 2n = 74, NF = 76, distinct from that of Canis spp. and Vulpes spp. [14], with C-banding and FISH showing heterochromatin amplification linked to chromosomal evolution [15]. Molecular tools, including microsatellite markers from roadkill samples, reveal high diversity and gene flow in Argentina and Uruguay [16,17,18]. Hybridisation with L. vetulus occurs in Brazilian ecotones [19], while the detection of L. griseus and L. culpaeus haplotypes in morphologically identified L. gymnocercus suggests introgression near overlapping ranges [20,21,22]. Broader mtDNA and nuclear datasets confirm monophyly but highlight admixture and blurred boundaries, as echoed in the Fuegian dog—an extinct domesticate that clusters closer to L. culpaeus than to domestic dogs [23,24,25]. Morphometric studies reinforce this plasticity: analyses of more than 150 skulls and pelage samples revealed no diagnostic traits that separate L. griseus from L. gymnocercus [26]. At the same time, geometric morphometrics revealed clinal gradients linked to allometry and climate [27,28], with skull and body size shifting along environmental and thermal axes rather than at strict taxonomic boundaries [27,28,29]. Sexual dimorphism is moderate, with males being larger in southeastern Buenos Aires [30]. Pigmentation anomalies, such as leucism and piebaldism, add further variability [31,32]. Beyond external morphology, detailed anatomical work on skeletal design, musculature, peripheral innervation, viscera, vasculature, sensory structures, and reproductive systems shows that L. gymnocercus largely conserves the generalised canid plan but expresses its own ecological and functional profile—e.g., cursorial forelimb architecture, proximally concentrated limb musculature, modified lumbosacral plexus inputs, and a fibroelastic penile structure shared with C. thous [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. A synthetic comparative summary of these traits, including contrasts with L. griseus, C. thous, and domestic dogs, is provided in Table 2 [1,2,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

Table 2.

Comparative anatomical profile of the Pampas fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus) across major systems (cranial, axial, appendicular, neuromuscular, visceral, sensory, reproductive), contrasted with other South American canids (L. griseus, Cerdocyon thous) and domestic dogs.

Altogether, these findings portray the Pampas fox as a meso-carnivore shaped by evolutionary lineage, ecological pressures, and habitat use. Subtle morphological nuances highlight its affinities within South American canids while underscoring its distinctiveness. Each anatomical detail (Figure 6) thus enriches not only our understanding of L. gymnocercus but also broader patterns of adaptation and clinical practice across Neotropical canids.

Figure 6.

L. gymnocercus photographed in the rocky grasslands of Uruguay, showing its characteristic morphology—slender muzzle, dark dorsal stripe, and dense, bushy tail. These traits reflect the evolutionary and environmental pressures that have shaped the species’ adaptation to open and semi-open habitats across southern South America. Photo: Alexandra Cravino.

3.1.2. Distribution, Habitat, Breeding Ecology and Ecological Flexibility

The Pampas fox (L. gymnocercus) occurs across Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia. Its distribution shows both consolidated presences and striking gaps shaped by habitat, human activity, and survey bias. Across the Southern Cone, foxes are classified into two groups: Cerdocyon (found in forested northern areas) and Lycalopex (predominant in most of the region, except for the Paranaean and Atlantic forests) [3,22]. Within Lycalopex, L. gymnocercus dominates wetter central–eastern areas, whereas L. griseus is associated with drier western and Patagonian habitats; both may occur in contact zones in western and northwestern Argentina [3,22]. Current syntheses map L. gymnocercus from eastern Bolivia and western Paraguay to central Argentina and southern Brazil, while L. vetulus is restricted to the Cerrado and L. sechurae to the Pacific Peru–Ecuador coast [25]. Genetic data confirm high heterozygosity, gene flow, and moderate differentiation in Argentina, as well as hybridisation with L. vetulus in Brazilian ecotones [17,18,19]. This is accompanied by non-reciprocal mtDNA structure between L. gymnocercus and L. griseus in contact areas, consistent with secondary hybridisation and introgression rather than full reciprocal monophyly [22,25].

Regionally, L. gymnocercus is present in the Paraguayan Chaco but absent from the Oriental region, except for low-density records on Isla Yacyretá [48]. Abundance increases westwards into drier Chaco habitats, whereas Cerdocyon thous, which dominates humid zones, is absent. Most Oriental records appear to be misidentifications [48]. New records from eastern Paraguay expand its range and document mortality, behaviour, and local perceptions [5]. In the Dry Chaco, it is also more frequent in open habitats [49]. In Brazil, it inhabits the Campos de Palmas grasslands [50], is now recorded in north-central Paraná State [51], and is common at Taim Ecological Station, as well as in dunes and marshes [52,53]. Three subspecies have been proposed (gymnocercus, antiquus, lordi), but their limits are imprecise, likely intergrade, and remain uncertain in areas such as Entre Ríos (NE Argentina) and southeastern Bolivia [1,2]. In Argentina, the species uses diverse environments: protected areas in Entre Ríos [54], livestock farms in La Paz [55], Mar Chiquita Reserve where it faces poaching and road threats [56], and Península Valdés (Patagonia Argentina), where it coexists and partially overlaps in habitat with the introduced European hare (Lepus europaeus) [57], remaining frequent in a region dominated by extensive sheep ranching and associated poisoning conflicts [58,59,60]; in Talampaya (La Rioja Province), it also interacts with the endemic lesser grison (Lyncodon patagonicus) [61]. The species is recognised as an introduced exotic in the Malvinas/Falkland Islands and Tierra del Fuego, where its presence is considered well established.

Its distribution shows both consolidated presences and striking gaps shaped by habitat, human activity, and survey bias. New records from eastern Paraguay expand its range and highlight mortality, behaviour, and local perceptions [5].

Habitat studies confirm that L. gymnocercus consistently prefers open environments—such as grasslands, pastures, dunes, and savannas—while avoiding dense forests or intensive croplands (Figure 7); yet it tolerates moderately disturbed zones near settlements [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. Large-scale surveys reveal higher detectability in open areas, with forest strips and water bodies contributing to enhanced carnivore richness [73]. Behaviour is mainly nocturnal–crepuscular but shifts in response to prey availability, sympatric species, and hunting pressure. In Uruguay and Iberá, it partitions activity with C. thous [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71], while diurnality declines in hunted landscapes [74]. Reports from Paraguay and Brazil indicate that L. gymnocercus can remain active throughout the entire 24 h cycle.

Figure 7.

L. gymnocercus in representative Uruguayan landscapes showing its affinity for open and semi-open habitats. The sequence illustrates (from top to bottom) the use of grasslands, rocky open fields, and lightly wooded slopes with scattered cover—typical of transitional zones between grasslands and forests. Photos: Alexandra Cravino.

In contrast, in central Argentina, radio-collared individuals spent most of their time resting. They exhibited peak activity at night, with secondary peaks at dusk and dawn, and reduced daytime movement. Activity was most significant during the summer–autumn period [2]. The fox also shows cathemeral activity with a nocturnal bias in the Yungas [75].

Home ranges average ~213 ha, often structured around monogamous pairs, with extensive den use—up to 16 reused annually near livestock areas [70,71]—and opportunistic use of Priodontes maximus burrows [71]. Field studies in central Argentina estimated an average adult home range of 263 ha (55–461 ha) and showed that Pampas foxes use latrines as communication sites, sometimes shared with Leopardus geoffroyi and Conepatus chinga. Dens occur in natural shelters such as rock cavities, hollow trunks, or burrows of armadillos and viscachas; pups (Figure 8) stay below ground for about three months while both parents guard and feed them, and dens are rarely reused [2].

Figure 8.

L. gymnocercus cubs/juveniles interacting in a grassland area of Uruguay. Their lighter, more uniform pelage and close physical proximity reflect social recognition and affiliative behaviour typical of early developmental stages. Photo: Alexandra Cravino.

Breeding in L. gymnocercus takes place mainly in spring, following a gestation period of roughly two months and producing small litters of around three to five cubs. The species shows a single annual reproductive cycle, with most adult females breeding each year and reaching sexual maturity within the first year of life [1,2]. Dens are typically established in sheltered sites such as tree hollows, armadillo burrows, or rock cavities, and litters may occasionally be moved between refuges [1]. Parental care involves both adults, which use long-distance and alarm calls to maintain contact and defend offspring during the breeding season. Field observations suggest a predominantly monogamous social structure, with pairs remaining together until juveniles disperse, although individuals forage mostly alone [2]. Despite individuals living up to 14 years in captivity, most survive only a few years in the wild, with annual survival around 7% in adults and 22% in juveniles, reflecting strong mortality pressures [1,2].

Altogether, these patterns highlight a species of remarkable ecological breadth: resilient across grasslands, wetlands, dunes, forests, and agroecosystems, yet still vulnerable to fragmentation, hunting, and survey gaps. Figure 9 illustrates this adaptability, depicting representative landscapes where the Pampas fox has been recorded, which challenges the narrow association with grasslands and underscores its broader ecological reality.

Figure 9.

Representative landscapes where L. gymnocercus has been recorded, showing its remarkable ecological plasticity across grasslands, wetlands, dunes, diverse agroecosystems, and fragmented or continuous forests (“montes”). Despite its common name (“Pampas fox”), the species thrives beyond grasslands.

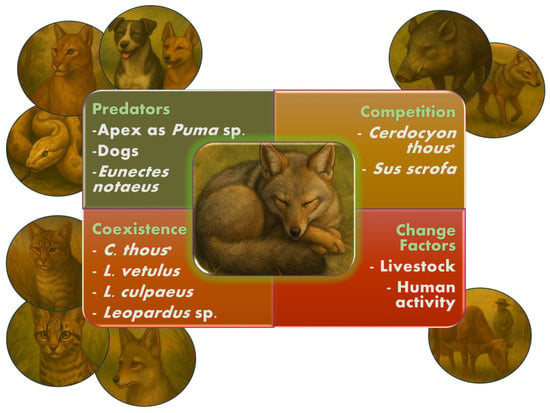

Ecological relations further underline its resilience. In the Espinal ecoregion and coastal dunes, L. gymnocercus overlaps temporally with Leopardus geoffroyi and Conepatus chinga, but spatial partitioning reduces conflict [76,77,78]. Mosaics of forest, water, and fields sustain carnivore diversity [79,80]. Scavenging experiments show delayed but significant participation [81]. Predation pressures include Puma concolor, free-ranging dogs, and species like Eunectes notaeus [82,83,84], with relations to C. thous and L. culpaeus ranging from competition to coexistence [85,86]. Foraging dynamics are further shaped by invasive Sus scrofa and human-driven changes such as livestock and land conversion [87,88]. Considered as a whole, these pathways (Figure 10) reveal the Pampas fox not only as resilient but as a mediator within evolving ecological networks.

Figure 10.

Ecological interactions of L. gymnocercus across its range, including predation (e.g., Puma concolor, dogs), coexistence with C. thous, overlap with Sus scrofa and L. geoffroyi. Grazing and habitat change also influence its dynamics.

Contrasts mark the distribution of the Pampas fox: broad yet fragmented, frequent yet under documented, adaptable yet vulnerable. Its persistence across grasslands, dunes, pastures, and disturbed mosaics highlights remarkable plasticity, but habitat fragmentation, hunting, and survey gaps still obscure key aspects of its ecology. Closing these gaps is essential to clarify its role and refine conservation priorities in a rapidly changing South American landscape.

3.1.3. Diet and Trophic Habits

Pampas foxes are adaptable meso-carnivores that combine active predation, scavenging, and fruit intake, and their diet spans wild and domestic vertebrates (including rodents, hares, viscachas, armadillos, birds, and livestock remains), invertebrates, fleshy fruits, native and exotic plants, carrion, and even refuse [2,5]. In central Argentina, dietary evidence indicates overlap with larger carnivores: both L. gymnocercus and Puma concolor consume armadillos, viscachas, small rodents, and European hares. Although the puma likely acts primarily as a predator, the fox functions as both a predator and a carrion user [1,2]. Trophic overlap is also reported with other mid-sized carnivores such as the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous), Geoffroy’s cat (Leopardus geoffroyi), and possibly the Pampas cat, indicating potential competition for small vertebrates and lagomorphs in shared habitats [2].

Feeding is opportunistic but patterned, coupling predation, scavenging and frugivory in ways that connect terrestrial food webs with plant recruitment. In Argentine grasslands, it relies on carrion and hares in modified areas but shifts to native prey in less disturbed sites; farmland diets emphasise livestock remains and rodents, whereas pristine areas favour insects and small mammals [74,89]. A taphonomic study from the Espinal and Dry Chaco (180 scats) reported the presence of plant matter, invertebrates, Lagostomus maximus, and Ovis aries, with bone breakage and digestion marks providing an archaeological signature [90]. In sympatry with C. thous (Brazilian Pampa), both species are generalist omnivores; however, L. gymnocercus consumes more insects and rodents while C. thous takes more fruits and amphibians (Ojk = 0.58) [91], a pattern consistent with integrated evidence of habitat use—L. gymnocercus in open areas and C. thous in forests [92]. In Bahía San Blas and Isla Gama Reserve, diets included mammals, insects, and fruits, with Lepus europaeus dominating vertebrate prey, and little evidence of livestock or fishing discards [93]. In Corrientes, diet was tracked to assess vegetation structure across protected areas [94]. In southern Brazil, both foxes fed on invertebrates, vertebrates, and fruits (e.g., Syagrus romanzoffiana), with a high annual diet overlap (Pianka’s index); yet habitat partitioning persisted—C. thous in forests, L. gymnocercus in open areas—driven chiefly by seasonal fruit abundance [95].

Ontogenetic and regional contrasts refine this picture. Cubs consume more vertebrates (rodents, hares, birds), while adults feed more on insects, fruits, and carrion—consistent with central-place foraging at dens [96]. In Salta’s Dry Chaco, year-round scat analysis (n = 431) revealed a predominantly frugivorous diet dominated by Ziziphus mistol (69% frequency, 91% volume) [97]. In Rio Grande do Sul, seasonal frugivory tracked phenology (e.g., Syagrus romanzoffiana, Hovenia dulcis), highlighting the fox’s role as a seed disperser (12 plant species identified) [98]. Region-wide assessments confirm its generalist omnivory—rodents, hares, birds, insects, fruits, carrion, and occasional small livestock—across pampas, scrublands, wetlands, Cerrado margins, and agroecosystems [99] (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Pampas fox in contrasting habitats of the Cuchilla Grande ecoregion, near Nico Pérez, Florida, Uruguay: (A) three individuals in an agro-pastoral landscape with fences, feeding on fallen Butia sp. fruits; (B) one individual foraging in rocky natural terrain. Photos: B. Vidal.

Altogether, L. gymnocercus emerges as a versatile meso-carnivore—predator, scavenger, seed disperser, and competitor—capable of adjusting to age, season, habitat, and human influence. This dietary versatility persists in transformed landscapes while reinforcing its ecological role in stabilising food webs, mediating interactions, and informing regionally tailored conservation strategies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Main diet components of L. gymnocercus across different regions and ecosystems of SSA, illustrating its dietary plasticity and context-specific trophic behaviour.

Animal Dietary Profile

Although often labelled an omnivorous generalist, the Pampas fox displays a dynamic, context-sensitive carnivorous profile that continually expands its prey spectrum. In Mendoza’s Payunia Reserve, it was observed that Phymaturus roigorum was being carried, marking the first record of predation on this endemic lizard [100]. In the Córdoba caves, modern bone assemblages revealed inputs from L. gymnocercus, L. culpaeus smithersi, and Leopardus geoffroyi, with wildfire exposure shaping burnt remains and underscoring the interplay between carnivore activity and fire regimes [101]. Feeding trials with rabbit carcasses showed both L. gymnocercus and L. geoffroyi produce strong bone destruction; however, foxes leave over twice the number of tooth marks, making modification frequency a more reliable indicator of their activity in fossil records [102,103].

In southern Brazil, diet studies position the species as a key predator within rodent-based food webs (alongside small cats and grisons). At the same time, raccoons and skunks specialise in aquatic prey and arthropods [104]. Field experiments revealed that both Pampas and crab-eating foxes predate artificial turtle nests at similar rates, guided by soil-disturbance cues—behaviour that increases chelonian vulnerability in modified landscapes [105]. Opportunistic predation further expanded the documented prey base, as evidenced by a calling Rhinella major toad in Bolivia, likely located by acoustic cues [106], and egg removal from artificial nests in Bahía Samborombón, likely to provision pups—contrasting with Sus scrofa consuming eggs on-site [107].

Rodents remain dietary cornerstones. In southern Brazil, analyses of 222 faecal samples and mammal surveys revealed a firm reliance on Akodon spp., a partial preference for Holochilus brasiliensis, and limited use of Oligoryzomys spp. [108]. Complementary stomach analyses (n = 70) confirmed murid rodents as the most frequent prey, with caviomorphs, lagomorphs, and carrion dominating biomass. Espinal populations showed higher dietary diversity, yet overall similarity across regions suggests a homogenised foraging ecology shaped by agricultural landscapes [109].

In Patagonia, the species has also been observed preying on chicks of several bird species, including early chicks of Darwin’s Rhea, as well as seabird chicks and eggs (e.g., penguins and gulls) in coastal colonies of northeastern Patagonia (M. G. Frixione, unpublished data).

Viewed together, these feeding patterns position L. gymnocercus as both an ecological mediator and a historical marker, its omnivory weaving links between prey regulation, cultural records, and present-day conservation challenges.

Plant Dietary Profile and Seed Dispersion

Despite its status as an omnivorous meso-carnivore, the Pampas fox contributes to processes commonly associated with herbivores and frugivores—most notably seed dispersal. Evidence from across Argentina highlights a dual role in regenerating native vegetation and facilitating the expansion of exotic species. For native flora, viable seeds of Prosopis flexuosa, Schinus johnstonii, Condalia microphylla, Celtis ehrenbergiana, and Acacia aroma have been dispersed, with gut passage enhancing germination, reducing latency, or enabling long-distance transport—particularly relevant in arid and fragmented habitats [110,111,112,113,114,115,116]. Conversely, it also disperses invasive plants such as Morus nigra and Pyracantha atalantioides, with seeds remaining viable and, in the latter, even showing improved germination [112,113]. Beyond plants, L. gymnocercus disperses exotic ectomycorrhizal fungi, inoculating Pinus elliottii seedlings with Suillus granulatus and Rhizopogon pseudoroseolus in mountain grasslands, underscoring an overlooked role as a fungal vector [117].

Together, these studies reveal the Pampas fox as an ecological mediator that bridges the plant and fungal life cycles. Its gut passage not only transports but also alters the performance of propagules, shaping the recruitment of both native and exotic species. By enhancing shrubs in degraded habitats, spreading invasive flora, and even carrying fungi across landscapes, L. gymnocercus emerges as a non-traditional but influential agent of ecological connectivity and transformation. This functional versatility, especially evident in transition or disturbed systems, warrants a re-evaluation of its role in ecosystem functioning and restoration (Table 4).

Table 4.

Examples of seed dispersal records of L. gymnocercus.

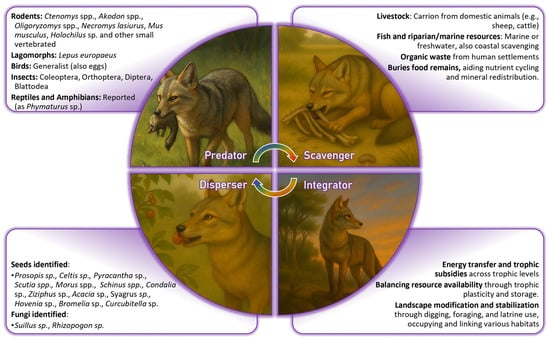

3.1.4. Final Ecological Aspects

Together, the evidence portrays the Pampas fox as an exceptionally versatile meso-carnivore, navigating shifting landscapes, prey availability, seasonal fluctuations, interspecific interactions, and human disturbance without compromising ecological relevance. It balances predation, scavenging, frugivory, insectivory, and seed dispersal—embodying adaptive trophic plasticity. Ontogenetic differences reinforce this profile, with cubs being provisioned with protein-rich prey and adults relying more on opportunistic foraging. In some contexts, it acts as a top predator of rodents, while in others, it shifts to feeding on fruit or carrion.

Its influence extends beyond consumption: by dispersing seeds and fungal propagules, the fox aids in vegetation regeneration, yet can also promote invasive species—acting as both a restorative and transformative agent. These dualities highlight the importance of context and the need for regionally nuanced management. Overall, the Pampas fox serves as a pivotal ecological node, functioning as both predator and scavenger, while also acting as a disperser and mediator, thereby contributing to energy transfer, nutrient cycling, seed germination, and ecological connectivity across natural and human-modified environments. Behaviours such as bone burial and seed dispersal stabilise fragmented habitats and reshape food webs. Figure 12 summarises these roles, presenting the Pampas fox as a dynamic agent of ecological balance.

Figure 12.

Trophic roles of L. gymnocercus. The circular diagram illustrates its main ecological functions—predator, scavenger, disperser, and trophic mediator—each contributing to energy flow, matter cycling, and ecosystem balance through prey regulation, carrion consumption, and seed or spore dispersal.

3.2. Health

The health of L. gymnocercus underscores its dual role as a resilient carnivore and a vulnerable host in anthropogenic landscapes. Documented ectoparasites include multiple flea taxa (Pulex irritans, Ctenocephalides felis, Hectopsylla broscus, Malacopsylla grossiventris, Tiamastus cavicola, Polygenis spp.) [1,2]. Internal parasites include cestodes (Taenia pisiformis, Dipylidium caninum, Joyeuxiella spp.) and the trematode Athesmia foxi in the small intestine [1,2]. Reported nematodes include Molineus spp. (incl. M. felineus), Physaloptera spp., Rictularia spp., Uncinaria stenocephala, Pterygodermatites affinis, Syphacia sp., Eucaleus sp., and occasional Ascaridia sp. [1,2,6]. High-prevalence trematodes such as Alaria alata indicate exposure via amphibian or paratenic hosts, and protozoa like Eimeria spp. and Sarcocystis spp. have also been detected [7].

Coinfections illustrate this complexity: an Argentine fox with severe incoordination carried both Canine distemper virus (CDV) and a Hepatozoon sp. (99% match to H. felis), with necrotising pneumonia and muscular cysts [118]. In southern Brazil, 40 wild canids (22 Pampas foxes) were universally parasitised by nematodes, cestodes, ticks, and protozoa, including the first record of Babesia sp. in this species [119]. Spillover is evident: Canine Parvocirus-2 (CPV-2) was detected in a Pampas fox among 37 mammals tested for canine pathogens [120]. Helminth surveys in Argentina and Uruguay revealed trematodes, cestodes, nematodes, and coinfections linked to aquatic prey, with zoonotic taxa such as Spirometra sp., Toxocara canis, Ancylostoma buckleyi, and Lagochilascaris sp. [121,122].

Multi-parasite cases continue: In Brazil, fatal rangeliosis involved Rangelia vitalii, Hepatozoon canis, and Capillaria hepatica [123]. In Bolivia, foxes harboured nematodes, cestodes, protozoa, ticks, and fleas, while antibodies to T. gondii were common [124]. In Brazil, serology to T. gondii (23%), T. cruzi (28%), and Leptospira (44%) confirmed a reservoir role [125]. Ectoparasites include the first record of sarcoptic mange in Pampas foxes (Bolivia) [126], and repeated infestations with Amblyomma spp., Rhipicephalus sanguineus, lice, and botfly larvae [127,128]. Cestode surveys in Buenos Aires revealed Echinococcus granulosus s.s. at a low prevalence (~1%), yet epidemiologically relevant given the species’ abundance [128]. Nematodes, such as Capillaria hepatica, reached a prevalence of 28.6% [129]. Molecular surveys detected Neospora caninum DNA in 74% of fox brains [130]. Additionally, other nematodes, including Angiostrongylus spp., were identified, with infections histologically confirmed in pampas foxes [131].

Viral dynamics add further concern. In Brazil, serological evidence of rabies virus exposure was confirmed in 13.3% of wild carnivores (13/98 individuals), including the first non-lethal case detected in a Pampas fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus) [132]. This percentage refers to the total sample; specific rates for L. gymnocercus are not available in official reports. Virome sequencing of five foxes revealed CPV-2, bocaparvoviruses, anelloviruses, and CRESS-DNA viruses clustering with domestic dog strains [133]. Faecal surveys detected human adenovirus (82%), canine adenovirus (5 cases), and rotavirus (41%), indicating anthropogenic contamination [134]. A CDV outbreak in a Brazilian reserve resulted in two fox deaths and ~90% seropositivity among 22 live-trapped individuals, with neurological signs linked to dog-derived strains [135].

The bacteriological dimension reinforces their sentinel role. In Brazil, Rickettsia parkeri DNA was found in 7.5% of ticks, with 62% of foxes seropositive [136]. In Argentina, the prevalence of antibodies to Brucella abortus reached 17.1% [137]. Enterococci from fox faeces showed 66% multidrug resistance, harbouring resistance genes (tetM, ermB) and virulence factors (gelE, esp, ace), marking the first such report in the biome [138].

Summarising, L. gymnocercus harbours a mosaic of parasites, viruses, and bacteria—many of which are zoonotic—that expose the fragility of fragmented landscapes and the porous interfaces among wildlife, domestic animals, and people. Sarcoptic mange, rangeliosis, helminths, protozoa (T. gondii, N. caninum, R. vitalii), viral exposures (rabies, CDV, CPV-2, adenoviruses), and bacterial threats (Brucella spp., Rickettsia spp., multidrug-resistant Enterococcus spp.) reveal its constant role as reservoir, victim, and bridge in multi-host cycles. The parasite community associated with this fox is dominated by taxa with indirect (multi-host) life cycles, which mirrors its omnivorous and opportunistic foraging. Patterns also vary between major ecoregions (e.g., Pampa vs. Espinal), suggesting that trophic breadth and habitat fragmentation actively reshape parasite assemblages, and that this plasticity can generate new host–parasite pairings of zoonotic relevance [6]. That ecology links aquatic prey, livestock environments, synanthropic scavenging, and domestic dogs into the same infection network, turning the species into both a sentinel and a conduit for pathogens of veterinary and public health concern.

Far from incidental, the Pampas fox emerges as a living bioindicator of anthropogenic impact and a warning system for emerging diseases. Its pathogen profile mirrors ecological fragmentation and underscores the urgency of integrated One Health surveillance. Protecting and monitoring this adaptable canid strengthens both conservation outcomes and public health defences. Figure 13 illustrates the range of parasites, bacteria, and viruses detected in Pampas foxes, underlining their sentinel role for One Health in fragmented ecosystems.

Figure 13.

Pathogens of the Pampas fox (L. gymnocercus): parasites (Hepatozoon spp., Toxocara spp., Sarcoptes spp.), bacteria (Rickettsia spp., Brucella spp.), and viruses (RABV, CDV, CPV-2, CAV, HAdV, RV). The species is a key host at the wildlife–domestic–human interface, relevant to One Health.

3.3. Socioenvironmental Conflicts

The Pampas fox (L. gymnocercus) inhabits a complex mosaic of human-altered ecosystems where agriculture, livestock, roads, dogs, and hunting converge. Abundance is generally higher in preserved grasslands than in croplands, where prey decline and legal hunting intensify pressures, and carrion fails to offset habitat loss [139]. Historically, persecution has been intense: in Argentina and southern Brazil, the species has long been labelled a predator of sheep and goats and actively eliminated by ranchers; L. gymnocercus was removed at scale (>360,000 individuals, 1949–early 1970s) in La Pampa, Buenos Aires and San Luis using traps, toxic cartridges, shooting, dogs and baits; bounty programs ran in other provinces, and fox pelts ranked among Argentina’s main fur exports in 1975–1985, with trade declining later but persisting illegally in Uruguay [1].

In Buenos Aires Province—one of the most fragmented, intensively farmed, and densely populated regions of Argentina—the species faces high hunting pressure linked to livestock conflicts, in a landscape characterised by severely degraded native grasslands and ongoing habitat loss, fragmentation, and persecution for allegedly predating on lambs [70,76]. Carnivores in these agroecosystems are especially vulnerable, with conflicts driven by extensive ranching and reduced natural prey; both foxes and pumas are considered priority targets by producers [76]. Camera-trap data show reduced detectability during hunting seasons, with dusk activity shifts reflecting behavioural plasticity in response to ecological traps [139,140]. In Buenos Aires Province, carnivores are particularly vulnerable, with pumas and Pampas foxes being the primary targets of conflict [70,76]. However, persecution persists: in Península Valdés, carnivores (and other mammals) continue to be poisoned despite legal bans [141].

Conflicts with dogs further complicate coexistence. In Río Negro, semi-feral dogs chase foxes and disturb prey populations [142]. In Brazil, the first recorded hybrid between L. gymnocercus and domestic dogs raised genetic and epidemiological concerns [143]. Free-ranging dogs attack/kill foxes and act as sources of pathogens (parvovirus, distemper, coronavirus, brucellosis, hemoparasites), reinforcing disease spillover risks in parts of Brazil [99]. Even in protected areas such as Ibirapuitã, foxes are still persecuted as pests [144]. Rural use and perceptions are ambivalent: fox fat has medicinal uses, and pelts were historically used for clothing. In contrast, in the arid Chaco, L. gymnocercus is hunted and perceived as a pest, despite its role as a provider of ecosystem services [1,110].

Roadkill is a significant mortality factor: between 2000 and 2015, 349 foxes were reported road-killed in Rio Grande do Sul [145], and they ranked second among mammals in Santa Fe (29.8% of a total of 154 records) [146]. Frequent collisions have also been recorded in the Araucaria Plateau [147], Jujuy (where foxes are the most affected animals) [148], and Corrientes. Seasonal peaks were reported in winter [149] and during wetter months [150], with foxes having generalist diets that expose them to road margins [151]. Proximity to highways and rural roads creates chronic mortality risk; landscape bio-corridors that connect wetlands, forest strips and productive lands can maintain connectivity and reduce roadkill risk in fragmented matrices [74].

Despite these threats, ecological plasticity enables persistence in agroecosystems. Foxes adjust activity, space use, and behaviour in response to human pressures [152], and unlike native deer, they tolerate livestock presence [153]. Activity is versatile across the range—predominantly nocturnal in Patagonia, cathemeral in northwestern Argentina, and more evenly distributed (nocturnal/crepuscular/diurnal) in protected areas of Buenos Aires—and shifts toward nocturnality under disturbance or hunting, tracking prey availability and perceived human risk while potentially reducing overlap with dogs [74].

Non-lethal strategies—such as livestock guardian dogs (LGDs)—reduce predation without causing adverse effects on Pampas fox ecology [154]. Sheep display aversive responses to predator cues (including the species) even in predator-free areas [155], while in Buenos Aires, Radio-tracking shows temporal avoidance of grazing zones (with minimal overlapping with sheep grazing areas, less than 4%) [156]; deterrents such as fox lights showed limited effectiveness in sheep farming systems in Uruguay [157]. Surveys in northern Uruguay indicate that producers perceive high predation levels from foxes, dogs, falcons, and wild boars, but losses decrease with the use of electric fencing and regular inspections [158]. Spatial models instead link conflict hotspots to roads and livestock density, while predation accounted for only 5.6% of livestock mortality, with pumas and foxes being the main reported predators [159]. In Buenos Aires, some deterrents (fox lights and flags) paradoxically increased fox activity in some cases, underscoring the need for integrated strategies [160]. Negative perceptions persist, especially in the Humid Chaco, where most livestock losses are attributed to climatic and sanitary factors rather than predation [161].

Across modified landscapes, L. gymnocercus shows strong ecological and behavioural plasticity: in the Dry Chaco, higher cattle grazing intensity lowers small-mammal abundance and richness, weakens the fox–prey link, and can force higher fox activity to meet energetic demands, indicating that reducing stocking rates could align ranching with carnivore conservation [88]; at fine spatial scales, human-modified mosaics subsidise foxes with livestock carrion and introduced prey (e.g., hares) while altering native prey availability, revealing trophic resilience with direct management value [89]. In the coastal dunes of southern Buenos Aires, Pampas foxes (found more inland) and Geoffroy’s cats (closer to the shore) coexist with limited spatial/temporal segregation, and these dune–scrub systems are considered compatible with carefully planned ecotourism and restricted infrastructure [77]. In productive Chaco systems, conserving waterholes, retaining trees in pastures, and maintaining forest strips/corridors support biodiversity: detectability of L. gymnocercus and C. thous decreases with forest cover, mammal diversity falls with distance from forest, and roads and nearby residences reduce corridor use, highlighting the need to manage structural landscape elements to sustain native fauna [73].

Cognition studies reveal underestimated abilities: Pampas foxes can discriminate between human attentional states and respond to human pointing and gaze direction, demonstrating social-communicative plasticity typically associated with domestic dogs [162,163]. This is not trivial behavioural tolerance—it means they are reading us, adjusting to us, and, in many rural contexts, actively negotiating space with us. The same animal that is trapped, shot, poisoned, or blamed for lamb losses is also capable of interpreting human signals, altering its activity to avoid risk, and coexisting in working landscapes. That places it in a culturally loaded position across the Southern Cone: pest, resource, omen, healer, livestock thief, seed disperser, and silent neighbour [1,110,162,163].

In summary, the Pampas fox occupies a precarious position at the edge of coexistence and conflict. It persists under persecution, habitat fragmentation, dogs, highways, and grazing shifts; it alters its diet, space use, and schedule to survive; it moves energy, seeds, and pathogens across systems; and it can read us. However, it is still routinely exterminated in response to perceived threat or written off as disposable. This tension reveals a deeper issue: the problem is not only technical but also cultural. True coexistence will depend on treating L. gymnocercus not as vermin to be managed, but as a species to be respected. However, as an ecological partner embedded in the same shared and fragmented landscapes, it helps hold together.

4. Discussion

The ecological trajectory of the Pampas fox is not a passive survival, but a constant negotiation that balances adaptation and disturbance, resilience and vulnerability. As SSA undergoes rapid transformation through agricultural expansion, urbanisation, and climatic pressures, this meso-carnivore occupies a pivotal yet precarious role in fragmented ecosystems. Its ecological functions, health dynamics, and recurring conflicts with humans expose the complex realities of wildlife persisting at the human–nature interface. The following discussion synthesises these dimensions, underscoring emergent patterns, conservation trade-offs, and the pressing need for integrative, cross-disciplinary frameworks.

4.1. Ecology

The Pampas fox is a longstanding participant in the socio-ecologies of southern South America. Fossil material attributable to L. gymnocercus itself appears by the late Pliocene–early Pleistocene (~2.5–1.5 Ma) in Argentina, anchoring the lineage well before the human record [2]. By the late Pleistocene–Holocene, zooarchaeological finds from Uruguay, Patagonia, the Paraná wetlands, and central Argentina already place it within human spheres—used, consumed, and symbolically integrated into daily life [1,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. This long coexistence persists biologically, characterised by high genetic diversity, clinal skull and body shifts across climates, and admixture with other Lycalopex spp. (L. vetulus, L. culpaeus, L. griseus) show a lineage shaped by permeability rather than strict taxonomic walls, with implications for identification, management, and health surveillance [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Anatomical and functional traits underline the same principle: a cursorial, diet-generalist body plan built for ecological patchiness [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

Landscape use reads less like preference than negotiation. The fox inhabits open and semi-open systems, including grasslands, dunes, wetlands, forest edges, ranch lands, and agroecosystems, across Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia [5,17,18,19,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. It depends more on the permeability and connectivity of mosaics than on single habitats [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. It persists amid threats with life-history traits tuned to pressure: cathemeral rhythms, small ranges centred on monogamous pairs, burrow reuse, biparental care, early maturity, and low survival rates (~22% juveniles, 7% adults) [1,2,56,58,59,60,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,146]. Trophically, it is an adaptable omnivore balancing predation, scavenging, and fruit intake—rodents, hares, birds, insects, carrion, livestock remains, or near-pure frugivory (Ziziphus spp., Syagrus spp.) [74,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109]—while dispersing seeds of native and invasive plants (Prosopis spp., Celtis spp., Condalia spp., Pyracantha spp., Morus spp.) and transporting mycorrhizal fungi [110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117]. Cognitively, it possesses a high socio-communicative plasticity, capable of discriminating human attentional states and following pointing cues [162,163].

Together, these traits define L. gymnocercus as an ecological mediator—predator, scavenger, disperser, and strategist—stabilising processes such as rodent control, seed regeneration, and nutrient cycling, yet also propagating invasive species and contributing to human–wildlife conflict. Conservation must recognise it not as a marginal pest but as a shaper of the dynamic mosaics it inhabits.

4.2. Health

Health patterns in L. gymnocercus reflect the same permeability that defines its ecology—a continuum of exposure rather than isolated events. The key signal is syndemics, which refers to overlapping infections and stressors that push individuals beyond physiological thresholds. Reports of multi-parasite and viral co-infections, such as CDV–Hepatozoon or rangeliosis complexes, illustrate how this species operates within a fluid pathogen landscape shaped by contact with dogs, livestock, and contaminated environments [118,123,126]. These patterns reveal a porous health interface, where pathogens and vectors move freely between wild, domestic, and human hosts, blurring the notion of boundaries that traditional epidemiology often assumes.

From a One Health perspective, the Pampas fox acts less as a simple reservoir and more as an indicator of ecological dysfunction. The recurrence of protozoa (T. gondii, N. caninum), bacteria (Leptospira spp., Brucella spp., antimicrobial-resistant Enterococcus spp.), and viruses (CDV, CPV-2, rabies) signals that health risks emerge from structural imbalances—habitat fragmentation, waste mismanagement, and uncontrolled domestic animal populations—rather than from the species itself [120,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138]. High CDV seroprevalence and rabies exposure, coupled with detection of human adenovirus and rotavirus in faeces, underscore the deep entanglement of wildlife and human sanitary networks [133,134].

In this light, L. gymnocercus embodies both vulnerability and diagnostic value. Its wide diet, scavenging behaviour, and tolerance for disturbed habitats make it a natural sentinel for cross-species transmission and antimicrobial resistance hotspots. Recognising the fox as a health integrator—not merely a passive carrier—reframes conservation and public health alike: monitoring its pathogens becomes a way to trace failures in environmental governance.

4.3. Conflicts

Conflicts are less about a “problem animal” than about problem structures. In croplands, prey decline, legal hunting, and carrion’s failure to compensate converge to elevate risk [139]; the fox’s behavioural shifts (lower detectability during hunting seasons, crepuscular tilts) read as plastic responses to ecological traps rather than simple tolerance [140]. Poisoning persists despite bans [58,59,60,61,141] and extends across regions, where limited monitoring and producer reluctance may hinder practical evaluation and enforcement. The Pampas fox has a long record of persecution: thousands were killed in central Argentina between 1949 and the early 1970s through traps, baits, dogs, and bounties, and it remains portrayed as a “lamb killer” across provinces like Buenos Aires, where grasslands are degraded, hunting persists, and foxes and pumas are still targeted [1,70,76,139,140,141].

Dog interactions intensify exposure—harassment, prey disruption, and even a documented dog–fox hybrid in Brazil, which reframes conflict as a genetic and epidemiological issue, not merely a depredation one [142,143,144]. Free-ranging and semi-feral dogs also serve as sources of pathogens (parvovirus, distemper, brucellosis, and hemoparasites), exporting domestic-dog disease pressure into fox populations and thereby tightening the dog–livestock–fox health interface [99]. Roads add another layer: mortality shows seasonal peaks and spatial clusters along watercourses, barrier-poor croplands, and corridor-bisecting routes [145,146,147,148,149,150,151]. Hundreds of Pampas foxes have been recorded as roadkill in provinces of Argentina and southern Brazil, and even protected or nominally conserved areas (e.g., Ibirapuitã) are not immune to direct persecution or collision-driven losses [144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151].

Despite these conflicts, the same permeability enables coexistence. Non-lethal husbandry—guardian dogs, adjusted timing and grazing patterns—can curb predation without altering fox behaviour [154,155,156]. Electric fencing and routine inspection outperform visual or light-based deterrents [157,158]. Telemetry shows foxes avoid active grazing zones (<4% overlap) and shift to nocturnal activity under hunting or dog pressure, reducing encounters [74,156]. Management should prioritise structural drivers—climate, disease, husbandry gaps—over predator control [159,160]. In northern Uruguay, electric fencing and inspection lower losses [158], while in Buenos Aires, superficial deterrents can backfire [157,160]. Yet, perceptions lag evidence, sustaining punitive attitudes in regions like the Humid Chaco [161].

Cognitive studies add nuance: foxes discriminate between human attention and follow pointing cues, unsettling simplistic “vermin” narratives and opening possibilities for community engagement rooted in animal cognition and rural culture [162,163]. In other words, the same animal, being trapped, shot, or poisoned, is also actively reading human signals and modulating its behaviour to avoid conflict, which turns coexistence into a communicative problem as much as an ecological one [140,162,163]. In short, durable coexistence hinges on aligning infrastructure, husbandry, and culture rather than relying on any single technological fix.

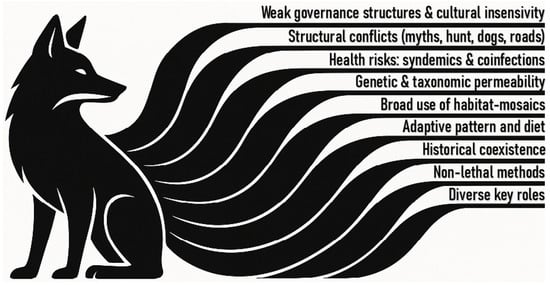

In this framework, the conflict surrounding the fox is no longer seen as a sum of isolated threats but rather as an interconnected system. To make this visible, we distilled the review into nine critical dimensions—the “nine-tails fox” blueprint—encompassing governance and cultural frameworks, structural conflicts, health syndemics, genetic permeability, functional traits, habitat mosaic use, historical co-occupation, non-lethal tools, and ecosystem roles (Figure 14). This synthesis explicitly incorporates persecution history, dog-mediated pathogen spillover, roadkill corridors, ranching structures, and adaptive space use by the fox, framing conflict as an emergent property of shared, human-dominated mosaics rather than an individual predator’s behaviour [1,74,99,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151]. More than an illustration, the scheme functions as an operational map, suggesting that in Southern South American landscapes, lasting solutions will emerge from aligning infrastructure, management, and culture under a One Health approach, rather than relying on a single technological fix.

Figure 14.

The “Nine-tailed fox” framework is applied to Lycalopex gymnocercus, where each tail represents a key dimension: governance and cultural failures, structural conflicts, health risks, genetic permeability, adaptive patterns, land-mosaic use, historical coexistence, non-lethal strategies, and multiple ecosystem roles.

4.4. Beyond the Species: Socio-Ecological and Ethical Dimensions of the Pampas Fox Paradigm

Public attitudes toward the Pampas fox are far from biologically neutral—they are cultural, intergenerational, political, and deeply semantic-linguistic in nature. Across the region, and even globally, derogatory uses of “zorro/zorra,” “perro/perra,” “yegua,” or “gato/gata” (fox, bitch, mare, cat) [164,165,166,167,168] normalise harm: they are common insults meaning untrustworthy, sneaky, dirty, promiscuous, disposable. That gendered and often misogynistic framing seeps into animal treatment itself—when a being is culturally coded as trash or thief, killing becomes ordinary. Language shapes violence.

Ethically, the fox is diagnostic: neither predator nor livestock, it reveals how societies treat what is merely inconvenient. Native fauna often adorns national symbols—as in Uruguay (the only country with full Pampas fox distribution), Argentina, or Brazil—yet the Pampas fox, as emblematic of el campo as the wire fence or the open pasture, is absent. These countries have issued coins or banknotes depicting native species such as the armadillo, capybara, puma, rhea, ovenbird, jaguar, whale, taruca deer, Andean condor, guanaco, hawksbill turtle, great egret, scarlet macaw, golden lion tamarin, and dusky grouper [169,170,171,172], but never the fox (any fox). Conserving it is therefore an act of cultural memory as much as it is a biodiversity policy.

Historically, persecution followed industry—fur, bounties, carcass control—and persists [1,70,76,139,140,141] because conflict is privatised: few plans, no compensation, scarce non-lethal tools. Enforcement is weak, even where hunting and the use of poison are banned; fragmented governance across five countries means there is no shared monitoring. Enforcement collapses into “everyone does what they want,” and the fox pays for that gap.

Institutions fail at One Health/One Welfare: dogs go unmanaged, welfare is ignored, and agencies are uncoordinated [173]. Public knowledge is limited—rural myths persist, and schools often overlook the species. Ethically, the question remains: how much inconvenience will we tolerate for another species to exist? The fox clears carrion, disperses seeds (studies recorded over 70 species dispersed across Córdoba, Argentina [174]), eats rodents—yet we answer with poison and bullets, a broken social contract passed on as “just what one does.”

Beyond conflict, evidence suggests that humans and foxes in the Southern Cone once shared bonds of coexistence and even companionship. Archaeogenetic findings from Mendoza, Argentina, reveal that about 1500 years ago hunter-gatherers buried an extinct fox (Dusicyon avus) in a human mortuary context, with the fox’s isotopic diet matching that of its human companions—pointing to an affectionate rather than utilitarian bond [175]. The already mentioned records of fox remains as ornaments or grave goods indicate that these canids held ritual, economic, and emotional value within pre-Hispanic societies. Far from constant conflict, foxes likely lived in partial synanthropy—helping control pests or serving as companions—evidence of a long, complex coexistence that still echoes in rural traditions of caring for orphaned pups and admiring their intelligence.

Superstitions and symbolic legacies have shaped the fox’s image across cultures and generations. Myths travelled with colonization: in medieval Christianity the fox embodied deceit and heresy, while in Greek, Roman and Asian traditions it shifted between divine and demonic roles, from helper to tempter or shapeshifting “foxy lady” [176]. Passed down through time, these beliefs turned fear into custom, legitimising persecution as a moral crusade. Yet, folklore remains ambivalent: the same trickster once condemned for deceit is also admired for wit and resilience, a duality that, if reframed, could restore the fox as a native emblem of intelligence and endurance.

Because rejection is partly moral and religious—“good” animals serve us, “bad” ones steal—policies that argue only with numbers (“lamb loss is low”) will keep failing if they ignore the inherited idea of impurity and threat. The conflict is not fox versus lamb but whether agriculture accepts ecological limits or insists on a morally sanitised landscape. This reflects speciesist and anthropocentric biases: animals perceived as useful are partially protected or tolerated, while those deemed pests—like foxes—are denied moral worth. A more ethical approach, rooted in compassionate conservation, calls for minimizing suffering even in abundant or conflictive species.

As a counter-narrative, the Pampas fox—common, familiar, charismatic, and locally “ours”—can be a flagship for a rapidly eroding biome. In Europe (for example), canids such as the wolf have become a respected national symbol [177]; here, no native meso-carnivore fills that role, and that silence is political. Naming the Pampas fox as a territorial species—part of what defines rural Uruguay, Argentina, and southern Brazil—is an act of biocultural recognition. The goal is not to romanticise the animal but to prove coexistence achievable once killing stops being the reflex.

On the ground, conflict is structural [139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163] and the fox adapts to a matrix of livestock, roads, dogs, crops, tourism, and hunting—shifting to crepuscular habits, denning near production zones, and tolerating livestock. Overgrazing, a continental problem [173] exemplified in the Chaco, degrades soils and vegetation, reduces livestock welfare, suppresses small mammals, and forces greater fox activity; it disrupts edaphic fauna, erodes trophic networks, and amplifies conflict across the Southern Cone [88,173], but remains unattended.

Along dune–scrub coasts, the fox shares space with other meso-carnivores (e.g., Geoffroy’s cat) [76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86], showing that restricting vehicles and infrastructure can preserve multi-carnivore landscapes without harming tourism. Collision hotspots—such as watercourses, fencelines, cropland edges, and highways—remain a significant, yet overlooked, mortality source [74,145,146,147,148,149,150,151]; roadkill and off-road tourism are governance choices, not background noise. The species thrives in porous, interconnected habitats but collapses under the impact of intensive agriculture, roads, dogs, and pesticides [70,76,77,88,141]. Regionally, it highlights the silent defaunation of South America: generalists persist, specialists decline, trophic webs erode, and fragmented reserves are unable to offset habitat loss.

Dogs compound risk by harassing, killing cubs, competing for carrion, spreading disease, and hybridising [1,99,110,142,143,144], yet vaccination, sterilisation and pack control remain absent from wildlife policy [99,173]. The belief that “the fox kills all the lambs” is false [159,160]; real solutions are preventive and structural, involving well-trained guardian dogs, electric fencing, supervised lambing, adaptive paddock rotation and reduced stocking [154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,173]. Resorting to shooting is convenient, but it only avoids addressing the deeper issues of fencing, carcass disposal, poison, dog control and corridor design.

Coexistence must also be fair. When costs fall on smallholders—vet bills, fencing, social blame—resistance is rational and the fox is shot. A just model combines non-lethal tools, technical and veterinary support, and public recognition that the fox has standing in the landscape—One Welfare in practice for people, livestock, dogs and wildlife [173]. Culturally, the shift is already visible: in other regions, younger generations are increasingly approaching wild carnivores—including foxes—with curiosity rather than hostility, reflecting a broader social revaluation of wildlife and coexistence in shared landscapes [178]; perception itself becomes an infrastructure. If the fox is seen as worthless, no policy endures. If it symbolises shared land health, mitigation, fencing subsidies, and roadkill corridors gain legitimacy. Its presence breaks the pastoral illusion of a domesticated countryside. It exposes the dominant agro model for what it is: territorial control disguised as order, ecological domination presented as care, and destruction justified as management.

The Pampas fox is not vermin at the production edge but a co-engineer of working landscapes [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117]. It already provides measurable ecosystem services [89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117]: pairs suppress rodents (reducing grain loss and zoonotic risk), scavenging lowers sanitation costs, endozoochory aids regeneration, and roadkills/scats function as pathogen sentinels while its space use informs landscape models. Economically, killing foxes can be costlier than coexistence; the absence of metrics licenses elimination—counting these functions is economic ecology, not advocacy. Beyond function, its cognitive flexibility shows an ability to read human attention and adapt behaviour [162,163]: an intelligence that negotiates rather than merely survives, grounded in social and ecological cognition that enables persistence in human-dominated mosaics. Across the Southern Cone, that awareness places the fox in a culturally charged position—pest, resource, omen, healer, livestock thief, seed disperser, and quiet neighbor [1,110,162,163].

The Pampas fox shares prey, parasites, and diseases with other meso-carnivores [1,2,6,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138], underscoring the need for management to evolve into landscape governance under an integrated One Health–One Welfare transboundary framework. Then, management stops being about erasing a problem animal and becomes landscape governance, aligning coordinated dog control, welfare-based deterrence, and habitat retention within shared monitoring systems. Taxonomic boundaries remain unresolved with L. griseus, and hybridisation with L. vetulus, C. thous, and domestic dogs persists, still lacking genetic baselines essential for effective conservation planning.

Countries of the region, such as Uruguay, illustrate how fragile animal welfare governance undermines both biodiversity protection and zoonotic resilience, exposing the deeper One Health–One Welfare gap across the Southern Cone. Despite progressive laws, enforcement remains fragmented and anthropocentric—dogs go unmanaged, wildlife lacks welfare frameworks, and education rarely integrates coexistence ethics [173]. These cultural and institutional voids fuel cycles of neglect and persecution that mirror the broader structural failures behind human–fox conflict: myth-driven violence, policy inertia disguised as pragmatism, and the absence of welfare-based governance linking human, animal, and ecosystem health. Embedding the Pampas fox within such a framework would not only protect a keystone species but also anchor a more ethical and resilient model of coexistence across shared landscapes.

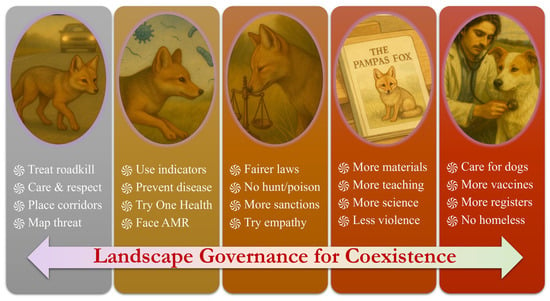

Conservation must shift from control to care: ban poisons, reduce roadkill, manage dogs, and promote coexistence under a genuine One Health–One Welfare vision that integrates human, animal, and environmental health through regional surveillance, shared laboratories, and early-warning systems. This requires systematic monitoring of parasites, viruses, bacteria, and antimicrobial resistance using non-invasive sampling—roadkill, faeces, and hair—and open databases supported by binding cross-border plans, budgets, and ethical standards prioritising welfare and community participation. Without such data, states will continue to hide behind ignorance to justify inaction. Coexistence (Figure 15) is not an optional ideal but the last honest path in a collapsing grassland biome, where persecution has become routine and a single mid-sized canid carries, largely unseen, the ecological and social work of balance.

Figure 15.

Five systemic levers align infrastructure, One Health operations, policy incentives, shared data, and culture to replace eradication with landscape governance. Each lever includes measurable targets, making coexistence accountable rather than rhetorical.

The Pampas fox is not an abstraction; it is a pair of steady eyes at the fence line, a parent caching fruit, a youngster already reading our gaze and learning our roads by sound. It understands enough to avoid us, not enough to outrun us. To kill such a mind for convenience brutalises the very landscape we depend on. Where the fox endures, margins seed, carrion clears, and children meet a native with curiosity; where it disappears, the country grows poorer—ecologically, culturally, morally. Coexistence is not a favour to wildlife but the least decent thing we can do for a neighbour that has negotiated with us for millennia. What remains to decide is not whether the fox can live beside us, but whether we can still live with dignity before what its gaze asks of us.

5. Conclusions

Lycalopex gymnocercus is more than a widespread canid; it stitches food webs, carries seeds and warnings, and meets our gaze with a dog-like intelligence: curious, attentive, capable of reading us even as it learns to avoid us. Across Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia, this “common” fox has held together the edges of a breaking biome—predator, scavenger, frugivore, and disperser, shaping regeneration in mosaics now sealed by fragmentation, from dunes and grasslands to forest edges and ranch lands. Health signals tell the same story of permeability: viruses, bacteria, parasites, and antimicrobial resistance track our waste, our dogs, our governance, making One Health surveillance a necessity rather than an option, and revealing where baselines are missing the very seams where policy and sanitation fail. Conflict is real (poison, hunt, roads, hybridization) but the species’ plasticity and documented cognition show that coexistence is not naive; it is practical and already workable on the ground, especially when structures match the evidence (trained guardian dogs, maintained fencing, supervised lambing, honest attribution of losses). What we decide about the fox declares the countryside we are willing to build: a landscape that tolerates complexity and limit, or one that mistakes control for care. Its decline would confess that we cannot keep land, health, and culture in conversation, that we chose speed and silence over responsibility. Its persistence would say the opposite: that we chose compassion over cruelty, fairness over convenience, truth over the pastoral illusion of dominion, and that we accepted the presence of another resilient will in our fields. Saving the Pampas fox is not sentimentality; it is a test of our capacity to govern shared life honestly, to keep ecological function and public health aligned, and to inherit a future we are willing to inhabit, with another aware, resisting mind moving through the fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.V.; Investigation, B.V.; Data Curation, B.V., L.V. and G.J.N.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, B.V.; Writing—Review & Editing, B.V., L.V. and G.J.N.; Validation, L.V. and G.J.N.; Supervision, G.J.N.; Funding Acquisition, B.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANII (Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación), grant number POS_NAC_2023_1_178487, and by the Programa de Posgrado en Ciencias Ambientales, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Uruguay.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available within the article and its cited references.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the generous photographic contributions of Alexandra Cravino, whose field images of Lycalopex gymnocercus greatly enriched the visual and scientific quality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-4 and O1 Preview to support the writing process (improving readability). The authors reviewed and edited the content and take full responsibility for the final text.

References

- Lucherini, M.; Pessino, M.; Farias, A. Pampas fox (Pseudalopex gymnocercus). In Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals, and Dogs: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan; Sillero-Zubiri, C., Hoffmann, M., Macdonald, D.W., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 63–68. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ariel-Farias-4/publication/256802919_Pampas_fox_Pseudalopex_gymnocercus/links/0c960523c6e256c9f5000000/Pampas-fox-Pseudalopex-gymnocercus.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Lucherini, M.; Luengos-Vidal, E.M. Lycalopex Gymnocercus (Carnivora: Canidae). Mamm. Species 2008, 820, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucherini, M. Lycalopex gymnocercus, Pampas Fox. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; ISSN 2307-8235. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mauro-Lucherini/publication/307512657_Lycalopex_gymnocercus/links/57c72da708aefc4af34c7c67/Lycalopex-gymnocercus.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/download/0008828-251025141854904 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Smith, P.; Louise-Smith, R. Natural history notes on Pampas Fox Lycalopex gymnocercus (Mammalia: Carnivora: Canidae) in the Paraguayan Chaco. Sitientibus Sér. Ciênc. Biol. 2023, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioscia, N.; Beldoménico, P.; Denegri, G. Contrastación de un Programa de Investigación Científica Progresivo en Parasitología: Los Endoparásitos del Zorro Gris Pampeano Lycalopex gymnocercus; Philosophy and History of Biology: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016; Volume 11, pp. 107–120. Available online: https://scholar.googleusercontent.com/scholar?q=cache:Z1v1k_z4OWMJ:scholar.google.com/&hl=es&as_sdt=0,5 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Perea, D.; Badín, A.; Manzuetti, A. Una fauna local lujanense (pleistoceno superior–holoceno inferior) del sur de Uruguay: Santa Regina, departamento de Colonia. Rev. Bras. Paleontol. 2021, 24, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzuetti, A.; Ubilla, M.; Rinderknecht, A.; Perea, D. The pampas fox Lycalopex gymnocercus (Carnivora, Canidae) in the late pleistocene of northern Uruguay. Ameghiniana 2020, 57, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]