Abstract

The Napoleon–Barlotti theorem belongs to the family of theorems related to the Petr–Douglas–Neumann theorem. The Napoleon–Barlotti theorem states: On the sides of an affine-regular n-gon construct regular n-gons. Then the centers of these regular n-gons form a regular n-gon. In the paper we give a generalization of this theorem.

MSC:

51M04; 51M15

1. Introduction

The Napoleon–Barlotti theorem (NBT) [1,2] is related to the Petr–Douglas–Neumann theorem [3,4,5,6,7]. It states that if one erects regular n-gons on the sides of an affine regular n-gon, then their centers form a regular n-gon. The special case of NBT is Thébault’s theorem [8]: If one erects squares on the sides of a parallelogram (), all either outside or inside of the parallelogram, then their centers form another square. See also Van Aubel theorem [9] and its generalization by J.R. Silvester [10].

In the paper, we prove a more general theorem, of which NBT is a special case.

Theorem 1.

Consider an arbitrary n-gon and a fixed point Construct an affine image of the n-gon and an affine image of Next, construct mutually similar n-gons on the sides of the affine polygon such that

where the similarities, except the first one, are all direct (the first similarity may be direct or indirect). Therefore, there are only two ways to construct these n polygons. Let us construct points that have the same relative position with respect to the vertices of polygons with indices as the point P with respect to the polygon . Finally, construct feet of perpendiculars dropped from the point P to the sides of the original polygon. Then, the similarity

holds. Moreover, this similarity has the same coefficient regardless of the choice of the point P. The position of the point relative to the polygon is the same as the position of the point P relative to the polygon

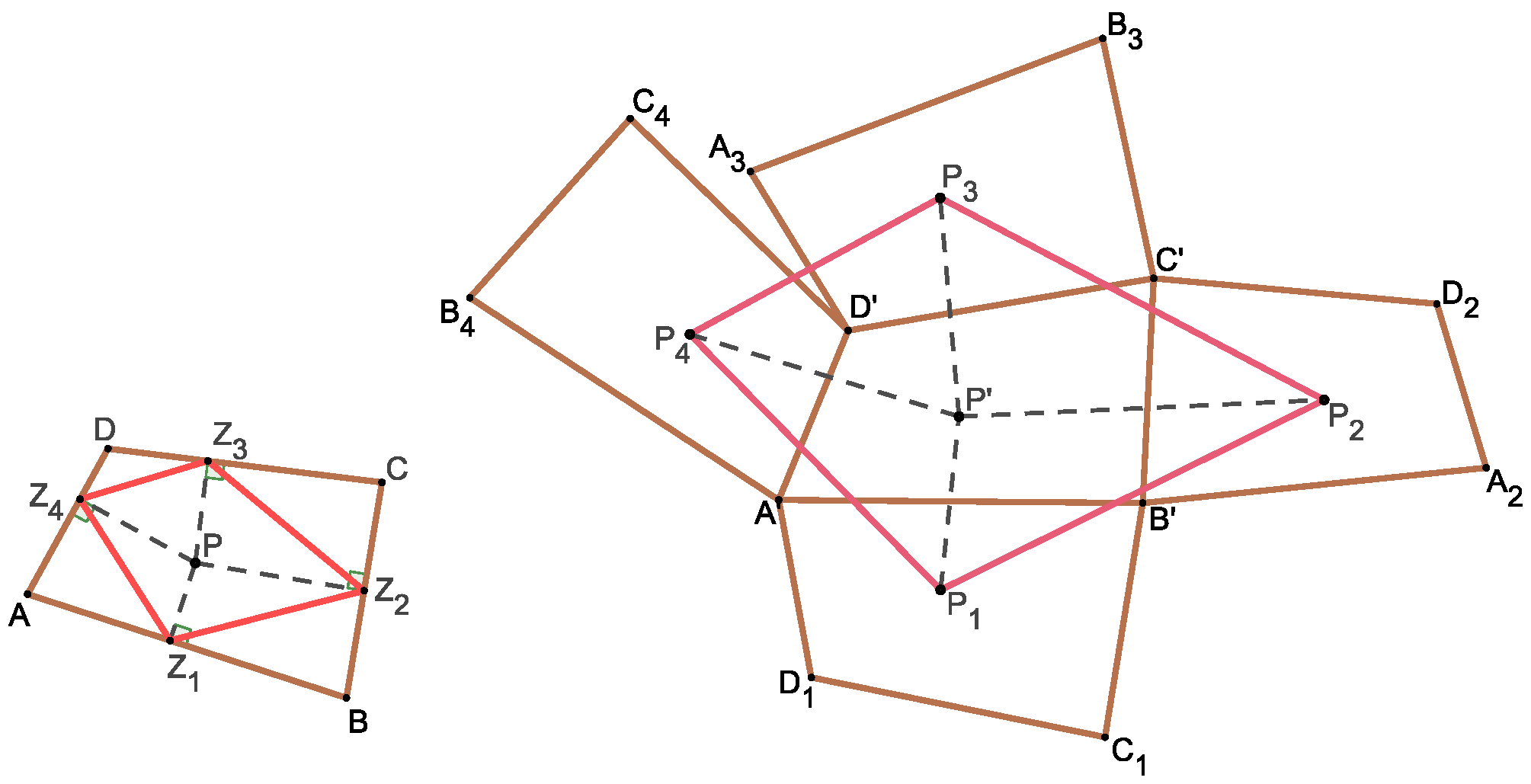

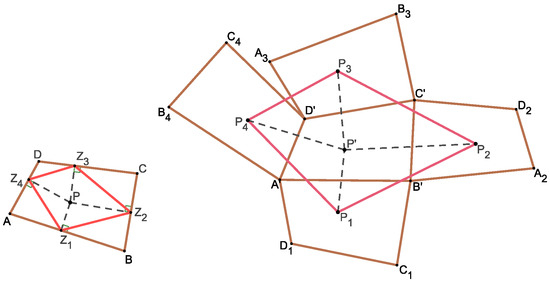

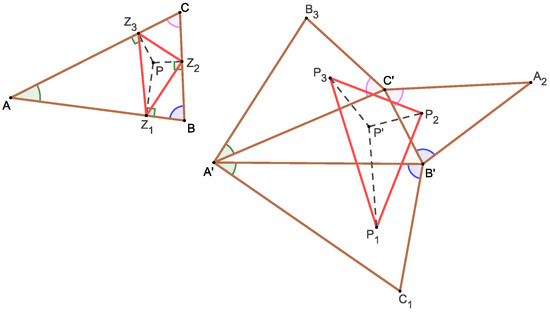

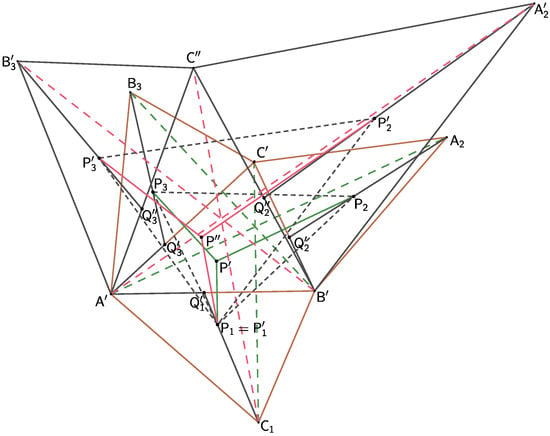

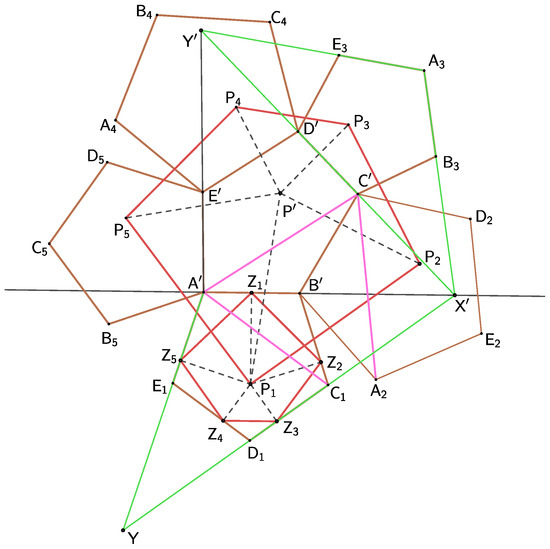

The theorem applied to a quadrilateral is illustrated in Figure 1. It is obvious that NBT is a special case of Theorem 1, since the feet of the perpendiculars that dropped from the center of a regular n-gon to its sides form a regular n-gon.

Figure 1.

Theorem 1 for a square. The position of the point P with respect to the quadrilateral is same as the position of with respect to .

The proof will be carried out in three steps: first, we prove Theorem 1 for an arbitrary triangle (Section 2, Theorem 2); then, we show that the validity of the theorem for a triangle can be used to prove that a certain mapping is a similarity (Section 3, Theorem 3). A direct consequence of this fact is the validity of Theorem 1 (Section 3).

2. Step One: Proof of Theorem 1 for an Arbitrary Triangle

Theorem 2.

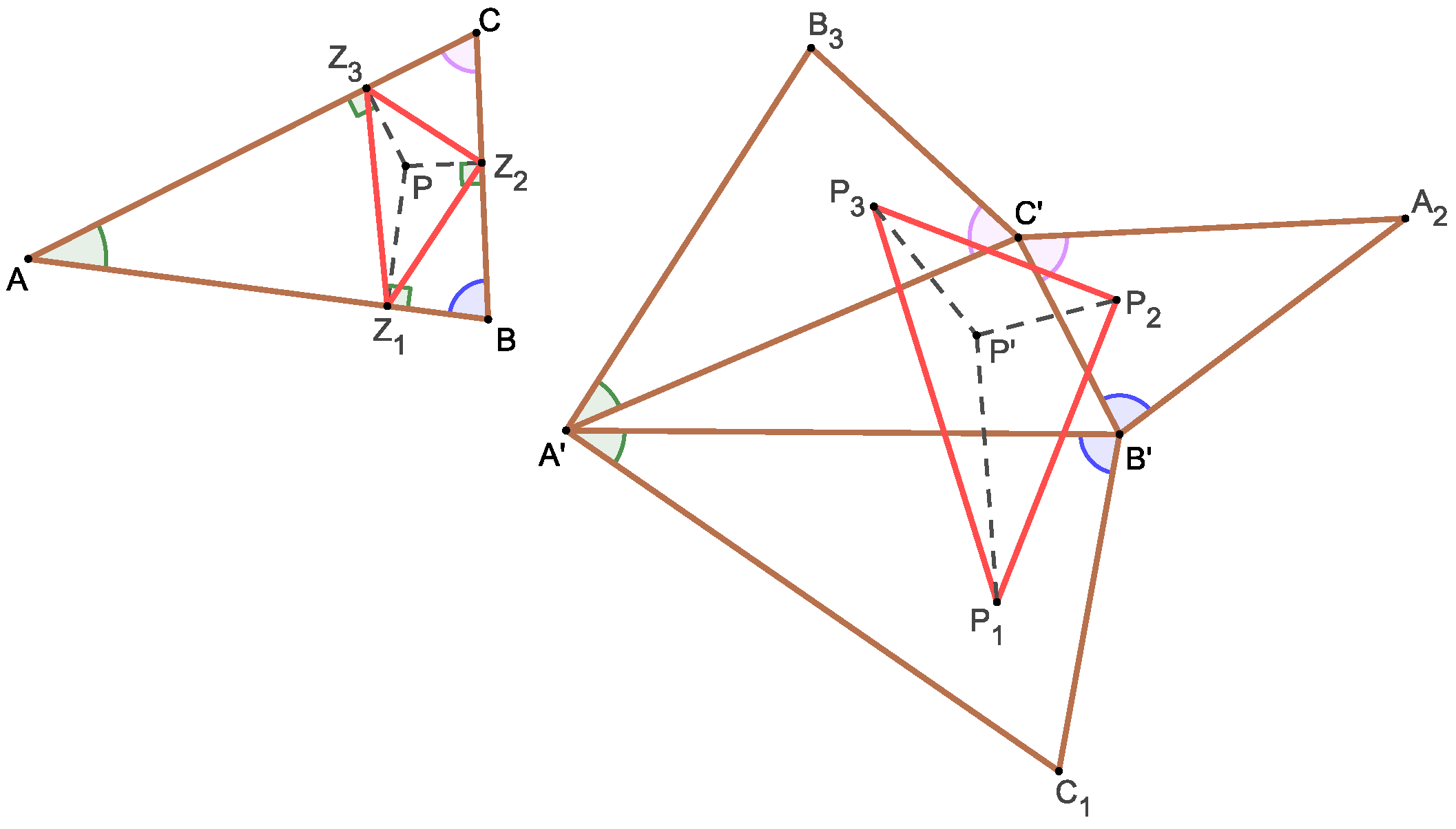

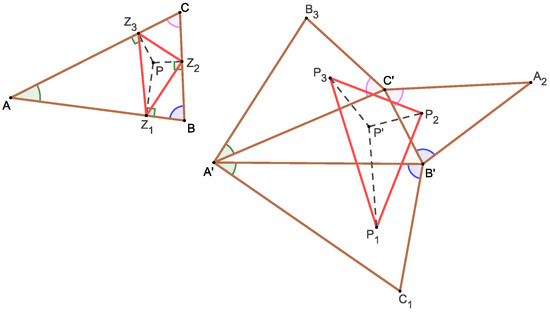

Consider an arbitrary triangle and a point P. Construct an affine image of the triangle and an affine image of the point P. Construct mutually similar triangles on the sides such that (Figure 2)

where the last three triangles are related to each other by direct similarity. Therefore, either none of the triangles overlap with triangle or they have a non-empty intersection. Let points have the same relative position with respect to the triangles , , as is the position of the point P with respect to the triangle . Finally, let us denote that feet of perpendiculars dropped from the point P to the sides , respectively. Then, the similarity

holds, where the similarity coefficient does not depend on the position of the point P.

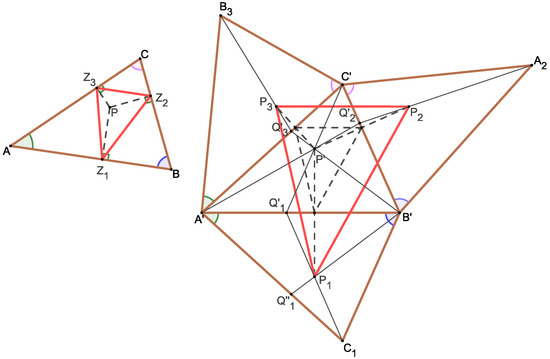

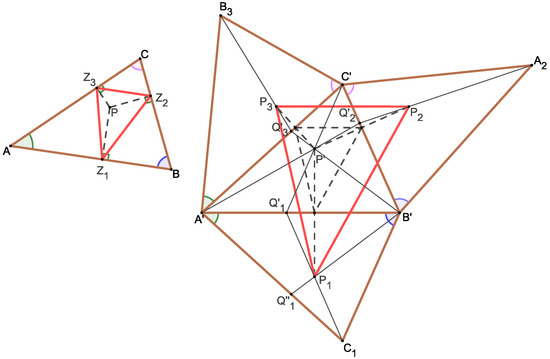

Figure 2.

Theorem 1 for a triangle. The position of the point P with respect to the triangle is the same as the position of with respect to triangle .

Moreover, the position of the point P with respect to the triangle is the same as the position of the point with respect to the triangle

Proof.

(For an alternative proof of this special case, see Theorem 2 in [11]). Let us start with a simple observation: if the triangles and are similar, then the statement of the theorem is obviously true (Figure 3), since, in this case, the points are reflections of the point over sides , and therefore, the pedal triangle of the point with respect to the triangle is similar to the triangle with the ratio of 1:2. However, the pedal triangle is similar to the triangle with a ratio of 1:k, where k is the coefficient of the similarity between triangles and Thus, the similarity coefficient of triangles and is k:2.

Figure 3.

This figure refers to two facts: (i) Theorem 1 holds if triangles and are similar, and (ii) lines and intersect in the affine image of the point whether the triangles are similar or not.

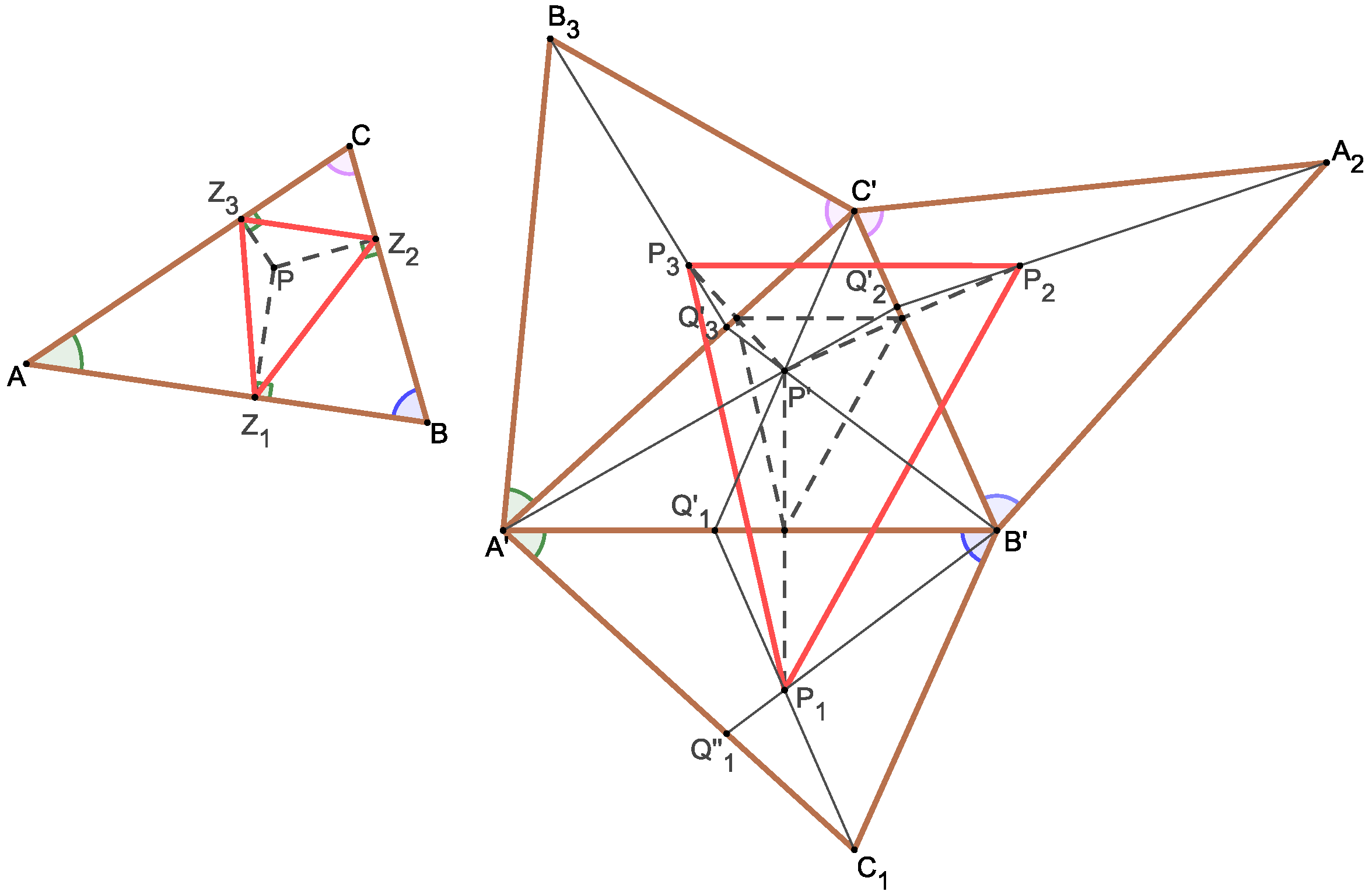

Let us now leave the assumption that triangles and are similar. Denote , and as the intersections of lines , and with lines , and (Figure 3). We will show that lines , and intersect at the point

Let be the intersection of lines and . Now, consider the affinity that transforms the triangle to the triangle This affinity maps the point onto the point onto itself, and the point onto since

It is due to the fact that the triangles and are similar, and points and have the same relative position with respect to their vertices. Therefore, the line passes through the point

Similarly, the line passes through the point . Moreover, the properties of the affine mapping imply that and

The symmetry implies

and

(Figure 4).

Figure 4.

For the similar triangle , Theorem 1 holds. It follows that this theorem holds for any triangle .

Based on the findings that Theorem 1 holds for similar triangles and that the lines , , and intersect in the affine image of the point P for arbitrary triangles and , we now prove the validity of the theorem in its entirety. We will consider triangle then triangle , which, as noted above, will be similar to the triangle , and finally an arbitrary triangle for which we will show that the theorem is also true.

All new points in the configuration of triangle are distinguished from points in the original configuration of the similar triangle by adding a dash (Figure 4).

We know that the line is parallel to the line , and the line is parallel to the line Furthermore,

Therefore,

By analogy, we arrive at the equalities

and parallelism of segments

Thus, to prove that the pattern formed by the points is similar to the pattern formed by the points it is sufficient to show that the pairs of segments , , and are in the same ratio and make the same angle. In other words, it is enough to prove the similarity of the triangles

It is sufficient to prove only the first similarity; the second one follows from symmetry. The similarity of triangles

follows from the fact that they have the same angle at the vertex and due to the similarity

the equality of ratios

is valid.

By analogy, we arrive at the similarity

It remains to show that the similarity coefficient of the triangle and the pedal triangle of the point P does not depend on the position of the point We know that this is true for but the similarity of triangles and is determined by the coefficient

which is fixed by the affinity converting the triangle into the triangle

Since the triangle is determined by its side and the original triangle we can conclude the following: Given triangles and the affinity and ratio (4) are determined uniquely, and therefore, the similarity coefficients of triangles and are the same for all points □

3. Step Two: Generalization of Theorem 1 to an Arbitrary n-gon

As shown in the previous step, the mapping between the points

is a similarity. For the next considerations, we will identify the triangle with the triangle We define the mapping as follows.

Let an affinity F be given by an axis a point , and its image Consider all triangles and related to the given affinity F. That is, all sides of the variable triangles lie on the given axis g. Now, we fix the point Denote the foot of the perpendicular from to the g-axis by and the feet of perpendiculars to other sides of any by with n given by the number of triangles taken into account.

For arbitrary triangles and related to the given affinity, construct triangles and to be directly similar to the triangle Let points and be in the same relative position with respect to these triangles as the point is with respect to the triangle As proven in Theorem 2, there is a similar mapping that transforms the points

to the points

Let us emphasize that this mapping is the same for all points because, for any triple, it is a similar mapping

with a common coefficient (4). In accordance with the current notation, we rewrite this coefficient in the following form:

The coefficient is constant for a given affinity. The points and their images are fixed by the assumption. The similarity is therefore either direct or indirect, but it cannot alternate; otherwise, we would get into a contradiction with the relation (5).

Note: Direct or indirect similarity depends on affinity, presumably on whether the point and its image lie on the same side or on opposite sides of the axis. We will not consider this question here.

Let us summarize the previous considerations in a theorem:

Theorem 3.

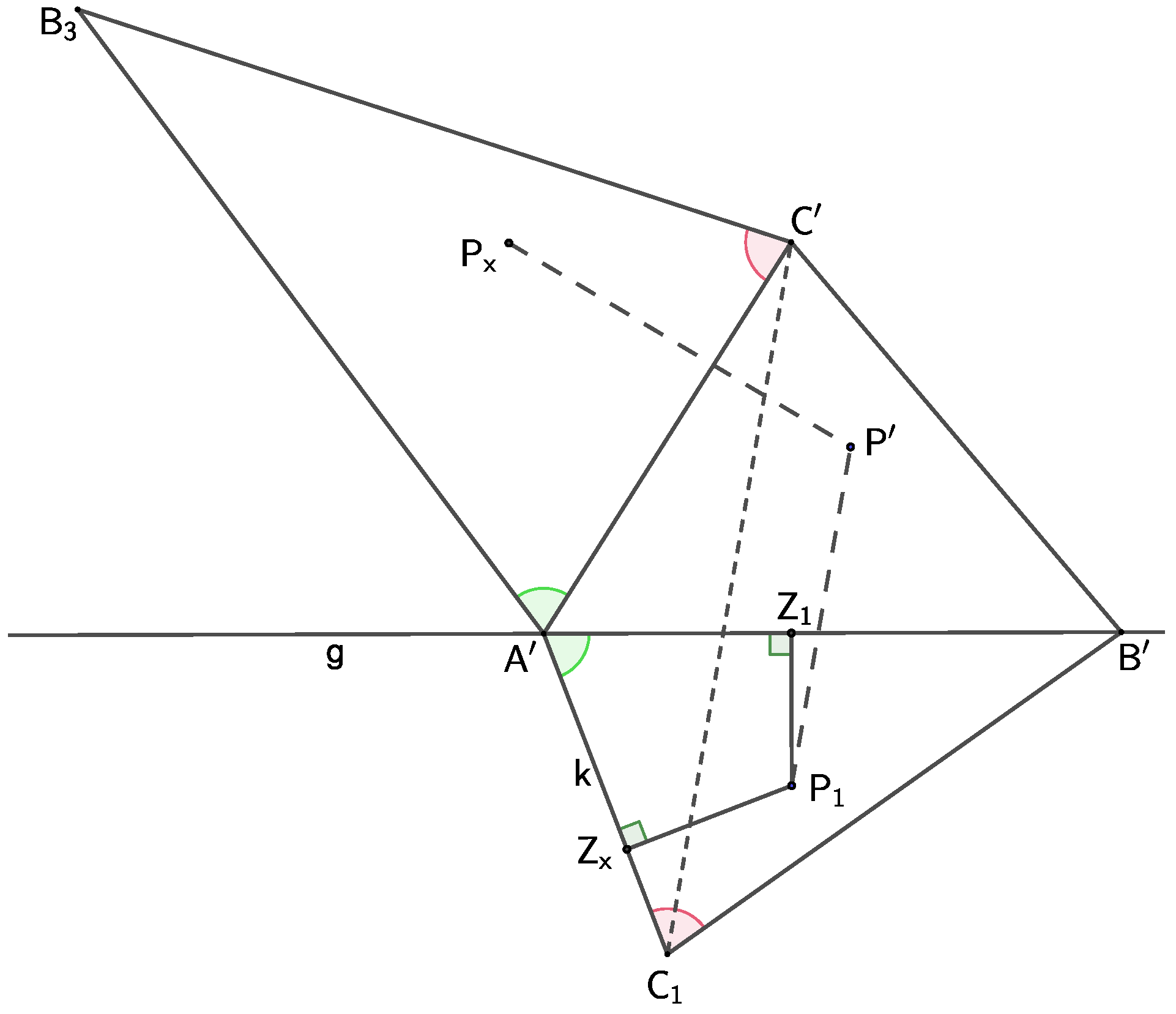

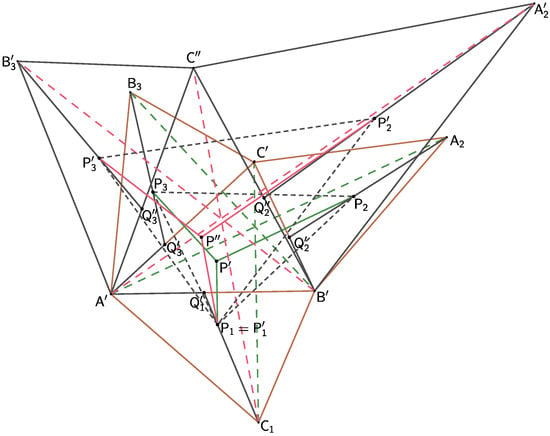

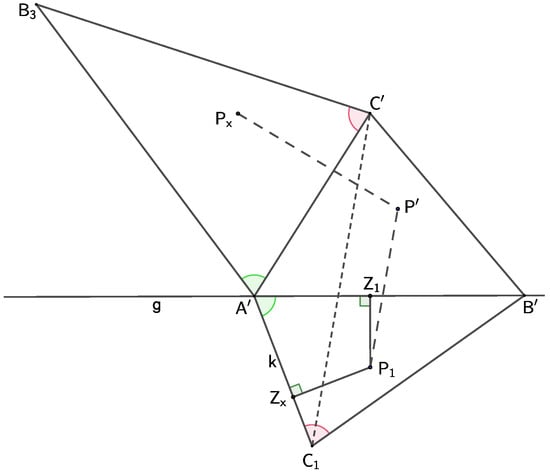

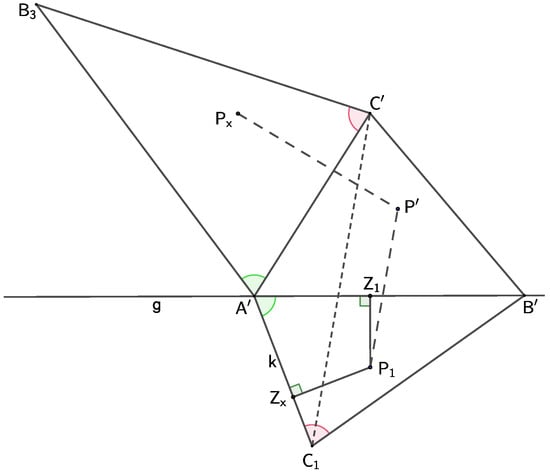

Consider the affinity F and its axis Given a point and its image in the affinity let the mapping assign to each point a point by the following algorithm (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Mapping . The affinity F and the point are given. Then, the construction procedure is a similarity.

- Construct a perpendicular k to the segment passing through the point Let it intersect the axis g at the point (or ).

- Choose any point on the line k and any point (or ) on the axis It determines

- Construct the affine image of the

- Construct (or ) directly similar to the

- Construct the point in the same relative position with respect to as the position of the point with respect to

- Definition: the image of the point (the foot of the perpendicular from to the line g) is the point

The mapping between points

defined in this way is a similarity. Moreover, no matter which point we choose, assuming a fixed affinity, the similarity coefficient given by

is constant, as implied by the affine-mapping property.

4. Step Three: Final Completion of Theorem 1

The proof of Theorem 1 is a corollary of Theorem 3. This is because the affinity F between the polygons and is given, and every point can be constructed using the point by the algorithm described in Theorem 3. Therefore, the mapping is a similarity. As is obvious, the pedal polygon of the point with respect to the polygon is similar to the pedal polygon of the point P with respect to the original polygon The theorem is proven for an arbitrary n-gon.

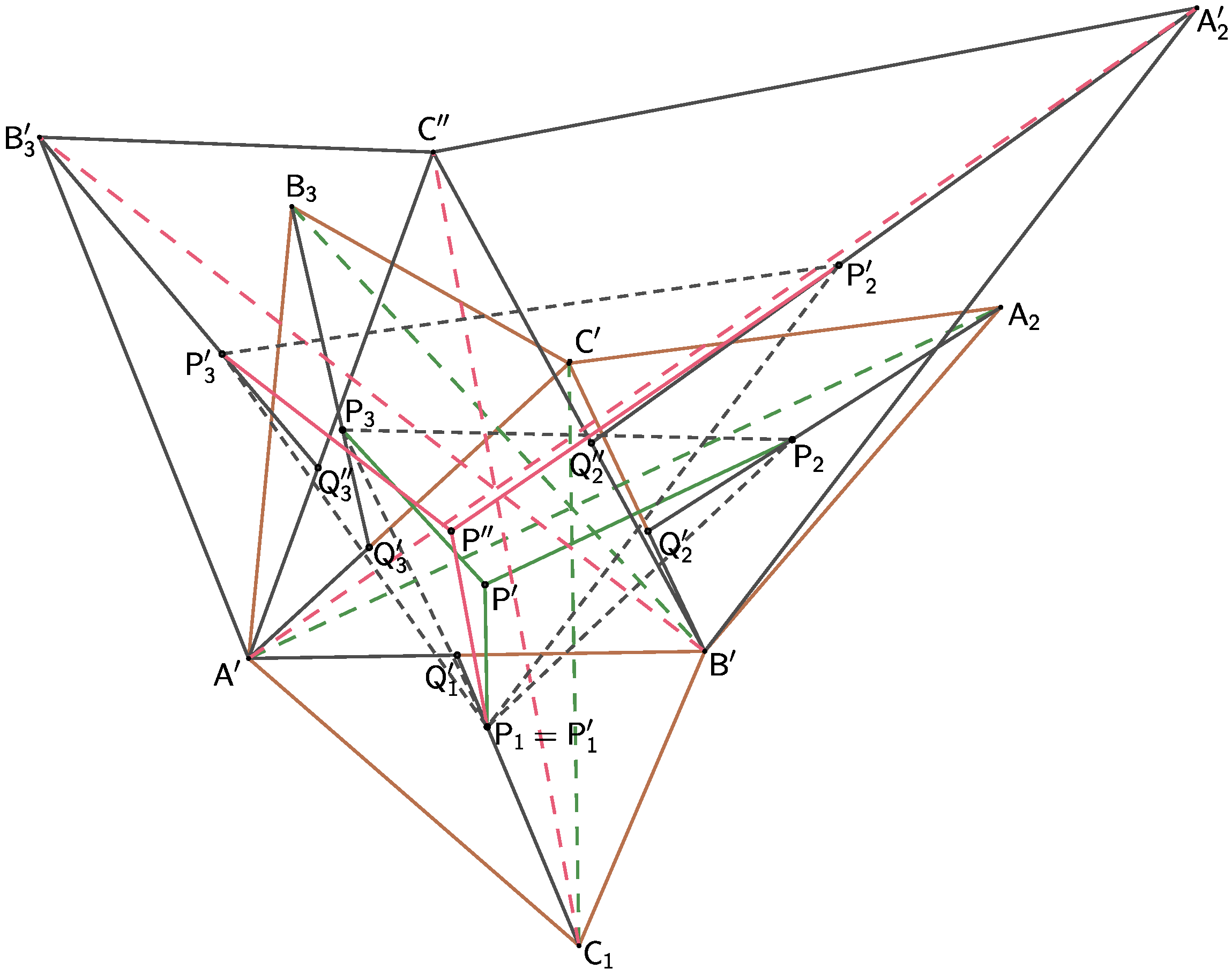

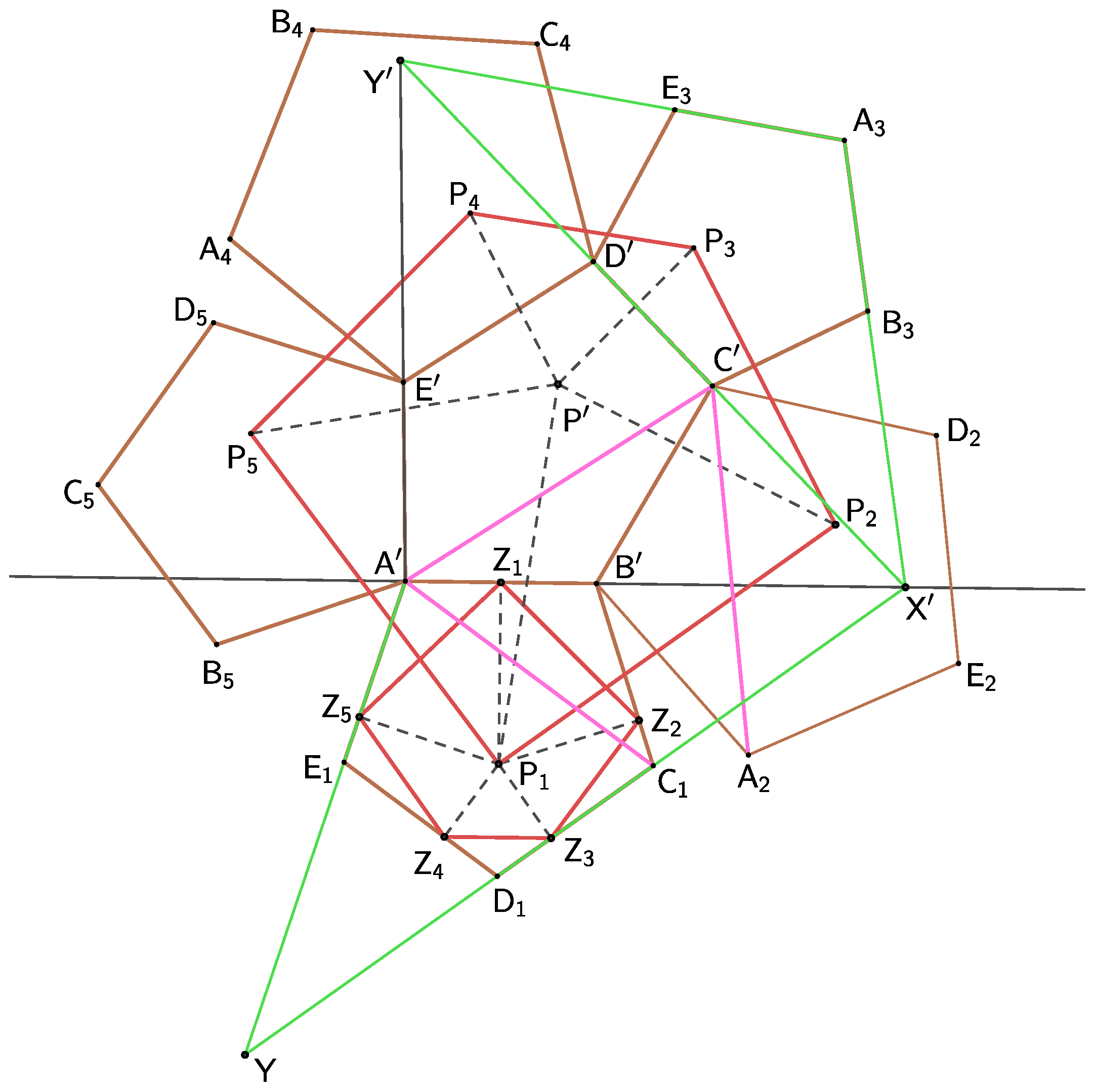

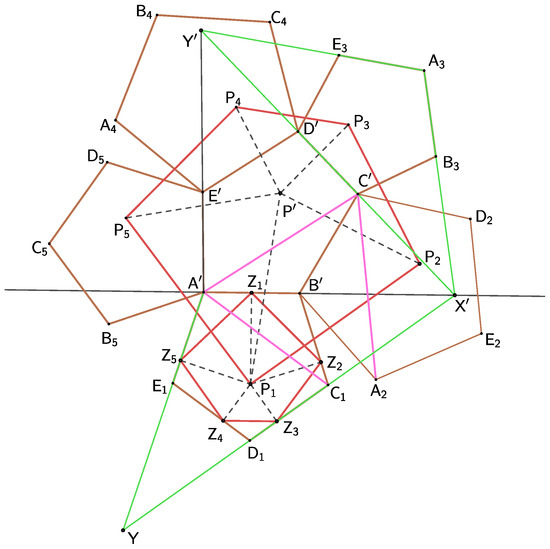

Let us show a concrete example for a regular pentagon and an arbitrary point

Example 1.

Consider a regular pentagon and its affine image . Let the affine axis be the line (Figure 6). Next, consider a point and feet of perpendiculars dropped from to the sides , and , respectively.

Figure 6.

Theorem 1 for a regular pentagon and its affine image The points can be constructed in two equivalent ways: as points with the same relative position with respect to their actual pentagon or using the algorithm described in Theorem 3.

The construction of the point corresponding to the pentagon is carried out as follows: consider and point then consider the affine image of the triangle, and then construct the and the point which has the same relative position with respect to as point has to . However, it is the mapping defined in Theorem 3 that maps the point to the point

By analogy, consider the pentagon and its corresponding point It is the same point that we obtain by the following procedure. By extending the segments and , we get Let the point lie on the axis. In the same way, by extending the segments and we achieve the The point is the foot of the perpendicular dropped from the point to the line . Now, construct the to be directly similar to the and its corresponding point It is not difficult to verify that We have arrived at the same map (affinity is the same); now, map the point to the point We can therefore conclude that the pedal polygon is similar to the polygon

The Napoleon-Barlotti theorem is a direct consequence of Theorem 1.

5. Conclusions

In this article we have proven a theorem of which the Napoleon–Barlotti theorem is a special case.

Note that most theorems belonging to the family of the Petr–Douglas–Neumann theorems are proven by algebraic methods. In this paper, we proved NBT and its generalization for arbitrary n using classical geometry. Although this classical geometric proof may seem rather long, we hope that this approach will enrich the proof techniques for this family of theorems.

Author Contributions

J.B. and P.P. have made a significant contribution to the conception, design, investigation, analysis and interpretation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barlotti, A. Una proprieta degli n-agoni che si ottengono transformando in una affinita un n-agono regolare. Boll. Un. Mat. Ital. 1955, 10, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, L. Napoleon’s theorem and the parallelogram inequality for affine-regular polygons. Am. Math. Mon. 1980, 87, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J. Geometry of polygons in the complex plane. J. Math. Phys. 1940, 19, 93–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.B. Generalizing the Petr-Douglas-Neumann theorem on n-gons. Am. Math. Mon. 2003, 110, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, B.H. Some remarks on polygons. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 1941, 16, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, P. The harmonic analysis of polygons and Napoleon’s theorem. J. Geom. Graph. 2001, 5, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Petr, K. O jedné větě pro mnohoúhelníky rovinné. Čas. Pěst. Mat. Fyz. 1905, 34, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thébault, V. Solution to problem 169. Natl. Math. Mag. 1937, 12, 92–194. [Google Scholar]

- Van Aubel, H. Note concernant les centres de carrés construits sur les côtés d’un polygon quelconque. Nouv. Corresp. Mathématique 1878, 4, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Silvester, J.R. Extensions of a theorem of van Aubel. Math. Gaz. 2006, 90, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažek, J.; Pech, P. Generalization of Napoleon’s Theorem: Similar Triangles. Math. Reflections 2024, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).