Abstract

As voice user interfaces (VUIs) rapidly transform the landscape of human–computer interaction, their potential to revolutionize user engagement is becoming increasingly evident. This paper aims to advance the field of human–computer interaction by conducting a bibliometric analysis of the user experience associated with VUIs. It proposes a classification framework comprising six research categories to systematically organize the existing literature, analyzes the primary research streams, and identifies future research directions within each category. This systematic literature review provides a comprehensive analysis of the development and effectiveness of VUIs in facilitating natural human–machine interaction. It offers critical insights into the user experience of VUIs, contributing to the refinement of VUI design to optimize overall user interaction and satisfaction.

1. Introduction

User Interface (UI) defines the way humans interact with the information systems. Currently, different types of UIs are being used depending on the context, including Graphical User Interfaces (GUI), Command-Line Interfaces (CLI), Voice User Interfaces (VUI), Touchscreen User Interfaces, Augmented Reality (AR) User Interfaces, and Virtual Reality (VR) User Interfaces.

Voice User Interfaces are artificial intelligence-enabled conversational user interfaces that enable interaction through spoken commands and responses [1]. They are increasingly being used by individuals in their day-to-day lives to fulfil diverse needs (e.g., utility, hedonic, and social).

Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs), Command-Line Interfaces (CLIs), Touchscreen Interfaces, and other traditional UIs are increasingly being supplanted by Voice User Interfaces (VUIs) across various applications, owing to their ability to substitute text-based or written input with speech-based interaction [2,3]. The unique benefits of mobile and hands-free engagement are provided by VUIs [4].

However, VUIs are frequently associated with usability problems that result in bad user experiences [5,6]. Usability is defined by the ISO as an “extent to which a system, product or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use”. Usability can be considered as a part of user experience (UX), which is defined by ISO as “user’s perceptions (including the users’ emotions, beliefs, preferences, perceptions, comfort, behaviors, and accomplishments that occur before, during and after use) and responses that result from the use and/or anticipated use of a system, product or service”.

In order to evaluate the efficiency and user-friendliness of VUIs, the study of user experiences is essential [7]; and to provide a seamless and gratifying user experience, it is crucial to assess VUIs’ usability [8].

A variety of procedures can be used to evaluate user experience and usability of VUIs [9,10]. Examining variables like learnability, effectiveness, satisfaction, and error prevention in VUIs is a part of usability evaluation [11]. Therefore, to fully comprehend how successfully VUIs satisfy user wants and expectations, it is essential to grasp these mechanisms.

However, two main research gaps can be identified in this field. First, the literature remains dispersed, making it difficult to keep track of the various findings. Therefore, it is necessary to synthesize the main findings of these studies, as they offer valuable knowledge for academics and practitioners [12]. Second, it is necessary to discern important underexamined areas in this field [13], providing a strategic platform for future scholarship. Therefore, academics and practitioners can develop novel and interesting research questions, ideas, theories, and empirical studies [14]

To address the aforementioned research gaps, the study proposes three research objectives:

- Identification of the top contributing countries, authors, institutions, and sources in the area of user experience, usability, and voice user interfaces;

- Development of a classification framework to classify user experience, usability, and voice user interface research papers on the basis of relevant commonalities;

- Development of a future research agenda in the field.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the research methods and tools employed for the systematic literature review and category identification. Section 3 details the findings of the bibliometric analysis. Section 4 introduces the proposed classification framework. Section 5 delineates the future research agenda. Section 6 discusses the implications of the findings. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper, addressing research limitations.

2. Research Methodology

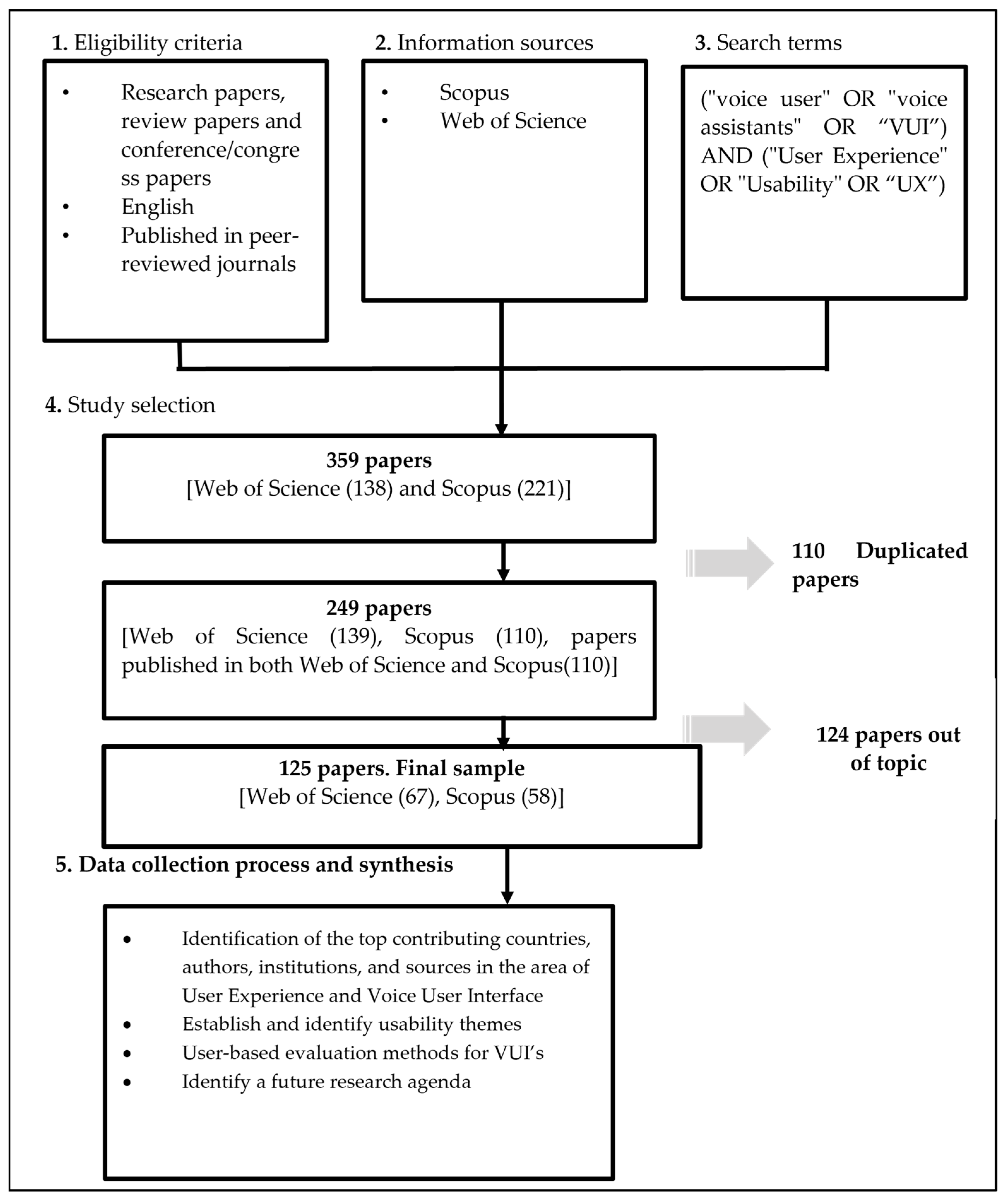

The research was conducted following the criteria of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) [15]. These include the following steps: (1) eligibility criteria; (2) information sources; (3) search terms; (4) study selection; and (5) data collection process and synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research methodology steps.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were research papers; review papers and conference/congress papers, since they are regarded as true knowledge [16]; directly relevant to sustainable customer relationship management; written in English; or published in peer-reviewed journals.

We excluded studies if they were not written in English; books, thesis, and conference proceedings; or papers that focused more on the direction of speech technologies and acoustics.

2.2. Information Sources

We performed a structured, systematic, and comprehensive search across two prominent online databases: Web of Science and Scopus. These databases were chosen for their rigorous selection criteria and extensive interdisciplinary coverage. Consequently, they are the primary sources of bibliographic citations employed in bibliometric analyses [17].

2.3. Search Terms

The collection of papers was carried out by selecting those that contained specific keywords pertinent to our research aims and questions in the title, abstract, or keywords section (Table 1). The keywords used included voice user interfaces (VUIs), usability evaluation, natural language, evaluation methods, VUI development, and user experience optimization.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

Logical operators were connected with different sets of keywords and designed as follows: (“voice user” OR “voice assistants” OR “VUI”) AND (“User Experience” OR “Usability” OR “UX”).

2.4. Study Selection

The study selection process aimed to analyze, evaluate, and identify relevant articles in alignment with the goals of our systematic review. This process was conducted independently by the two co-authors of this study to ensure objectivity and reduce potential bias.

First, records were identified through various information sources, specifically online databases, using predefined keywords. This initial search yielded a comprehensive list of potential studies.

Second, the retrieved records were scrutinized to remove duplicates, following the method outlined by [14]. This step ensured that each study was unique and avoided redundant analysis.

Third, the remaining records were screened based on their titles, abstracts, and keywords. This screening process aimed to exclude studies that did not meet the predefined eligibility criteria.

Finally, a full-text review of the remaining studies was performed to ensure a thorough evaluation. During this stage, the co-authors convened to discuss and reach a consensus on the final set of studies to be included in the systematic review. This collaborative discussion was essential to ensure that the included studies were rigorously selected and relevant to our research objectives.

2.5. Data Collection Process and Synthesis

The search focused on research and review papers published up to 10 July 2024. Initially, we identified 359 papers (138 from Web of Science and 221 from Scopus). After removing 110 duplicate papers, we applied eligibility criteria by screening titles, abstracts, and keywords. Papers where the acronym UX was associated with interpretations such as universal exchange, ultimate experience, utility exchange, unified execution, etc., were excluded, as were those where VUI could be interpreted as virtual user interface, vector unit instruction, etc. Subsequently, papers were further screened based on a full-text review. As a result, the final dataset comprised 125 papers (67 from Web of Science and 58 from Scopus).

The analysis of the data collection allowed us to develop a bibliometric analysis, identifying the top contributing countries, authors, institutions, and sources in the area of user experience and voice user interfaces to establish a classification framework composed of research categories, and to identify a future research agenda.

The bibliometric analysis followed established methodologies as demonstrated in several studies [18]. Initially, relevant papers were extracted from Scopus and Web of Science in BIB format. These files were merged into a consolidated dataset using the Bibliometrix (version 4.1) package in R [18,19]. Duplicates were systematically removed, and the cleaned dataset was exported to Excel (Version 2406 Build 16.0.17726.20206) for further analysis. Titles and abstracts underwent rigorous screening to eliminate papers unrelated to the study’s focus.

The refined dataset was imported back into Bibliometrix to compute key metrics such as top authors, journals, and sources [20]. Data merging, cleaning, and analysis stages were conducted using RStudio alongside the Bibliometrix package. For visualizing trends and patterns, we utilized the Biblioshiny package. Through these steps, a comprehensive bibliometric analysis was conducted, and the final results were exported for subsequent analysis.

Basic publication data such as publication date, title, authors, publisher, DOI, URL, pages, volume, issues, and keywords were collected using Microsoft Excel. The analysis of this data allowed us to identify the top contributing countries, authors, institutions, and sources in user experience and voice user interface (VUI) research.

For the research categories identification, the comparative method proposed by [21] was used. This method enables the identification of common points shared by the papers through a content analysis, so that the categories emerge. Content analysis is “an effective tool for analysing a sample of research documents in a systematic and rule-governed way” [22]. It allows an objective identification of the content in a data set, such as selected articles [23].

A first categories classification was performed, taking into account the aim of the paper and its contribution to the state of the art. Then, the capacity of the categories classification to arrange all the papers was checked paper by paper. If a paper did not fit into any research category, the classification was redesigned to integrate the incompatible paper. The categories classification was reconsidered several times until all the papers in the sample were properly distributed.

As a result, six main research categories, as well as a future research agenda in the field, were identified. We also created a qualitative and quantitative evidential narrative summary for each research category.

Any disagreements between the co-authors of this study were settled through consensus.

3. Bibliometric Analysis

3.1. Trend in Annual Scientific Publications

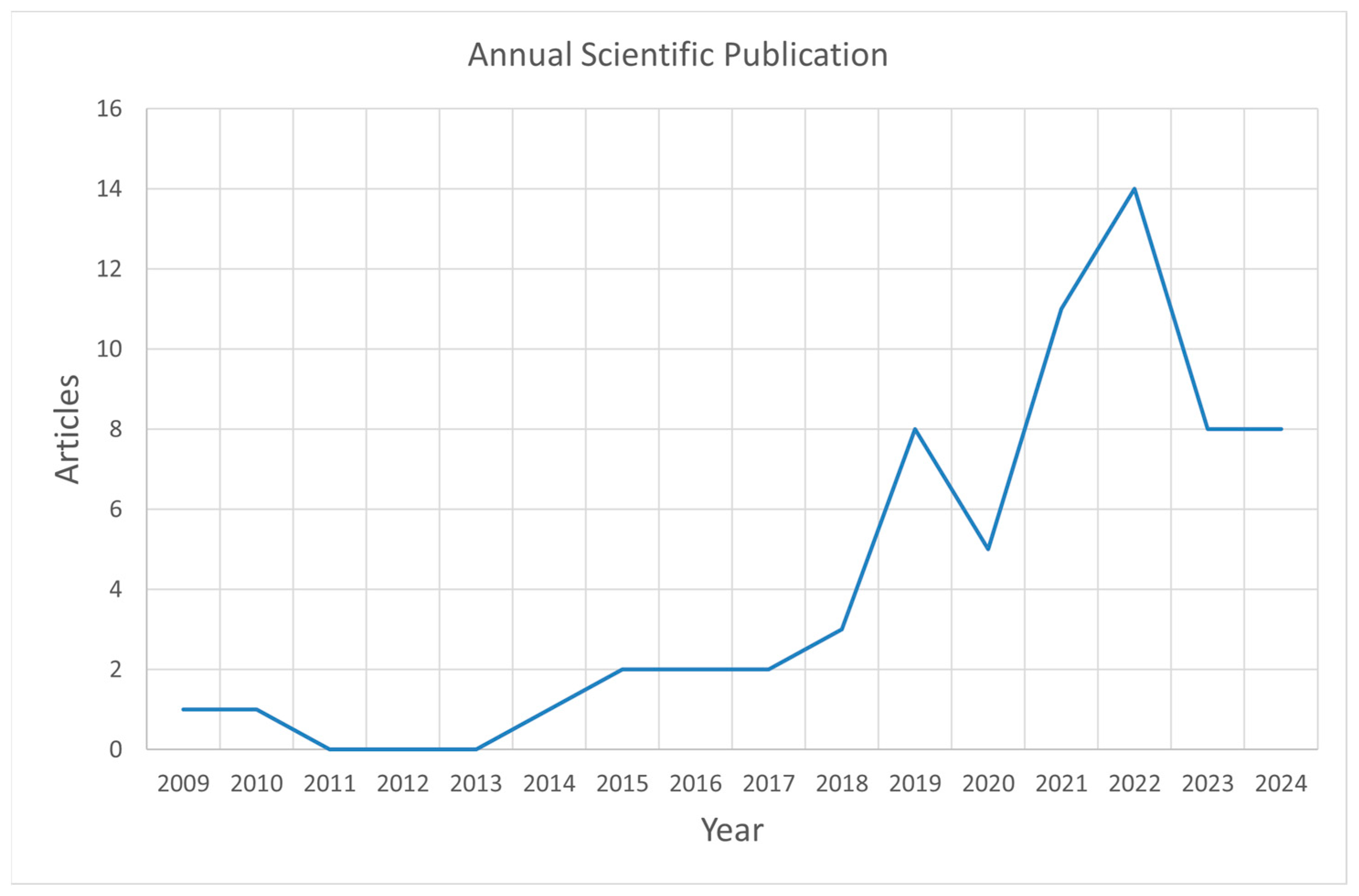

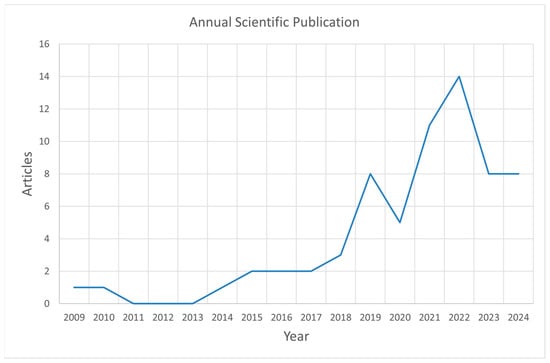

Since the inception of the systematic literature review in 2009, the evolution of publications has been notable, as illustrated in Figure 2. The trend shows significant growth over time, culminating in a peak of approximately 14 papers in 2022. As of the current year, the publication rate has shown a slight decrease, with fewer than 10 papers published to date. This trend highlights a dynamic landscape of research activity in the field, reflecting periods of intensified scholarly output followed by potential fluctuations in publication rates.

Figure 2.

Trend in annual scientific publication.

3.2. Most Influential Authors

In the bibliometric analysis of authors within the research domain, several key contributors have been identified based on their publications and citation metrics. Author Klein A. has contributed four publications with a total of seven citations. Similarly, author Munteanu C. also has four publications but with a higher citation count of 16. Notably, author Myers C. has made significant contributions, with three publications that have amassed a total of 150 citations. These findings underscore the varying levels of impact and productivity among authors within the field, reflecting their respective influence and scholarly contributions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Top contributing authors.

The top 10 authors in this analysis, ranked by their citation impact and productivity, include authors such as Myers C., Munteanu C., and Klein A., as well as others with comparable or higher metrics. Each author’s h-index, g-index, m-index, total citations, number of publications, and start of publication year were considered to assess their scholarly impact comprehensively. These metrics provide insights into the research influence and contribution of each author, highlighting the diverse contributions and impact levels within the research domain.

The h-index reflects a researcher’s productivity and impact, with a h-index of h meaning h papers have each been cited at least h times, which is widely used to assess research influence [24]. The g-index identifies highly cited papers, defined as the largest number of top papers that together accumulate g2 citations, complementing the h-index [25]). The m-index evaluates individual contributions in collaborative research by considering co-authorship, aiming to quantify unique scholarly output [26].

3.3. Most Influential Countries

The table below depicts the research output of the top 10 contributing countries in the field. The United States leads with 55 publications, followed by Germany with 24, and Canada with 21. China and India each contributed 16 and 13 publications, respectively, while Spain and South Korea also recorded 13 publications each. Australia, Japan, and Thailand each contributed seven publications. This distribution underscores the global engagement and varying levels of research activity across nations, illustrating their significant roles in shaping scholarly discourse within this research domain (Table 3).

Table 3.

Top 10 contributing countries.

3.4. Top Contributing Institutions

The table below presents the top 10 universities contributing to research within the specified topic. Leading the list is the University of Toronto with 10 publications, followed by King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi and the University of Seville, each with seven publications. Drexel University ranks next with six publications, while the University of Waterloo, Samsung R&D Institute, Seoul National University, Tokyo Institute of Technology, University of Applied Sciences Emden Leer, and Kookmin University each have four to three publications. This distribution underscores the active participation of these academic institutions in advancing scholarly discourse and research advancements within the field (Table 4).

Table 4.

Top contributing institutions.

3.5. Most-Cited Papers

Regarding the citation analysis of the papers, the most cited paper has 113 citations, which stands out significantly from the rest of the citations. Table 5 shows the ten most cited papers and their main contribution.

Table 5.

Ten most-cited papers.

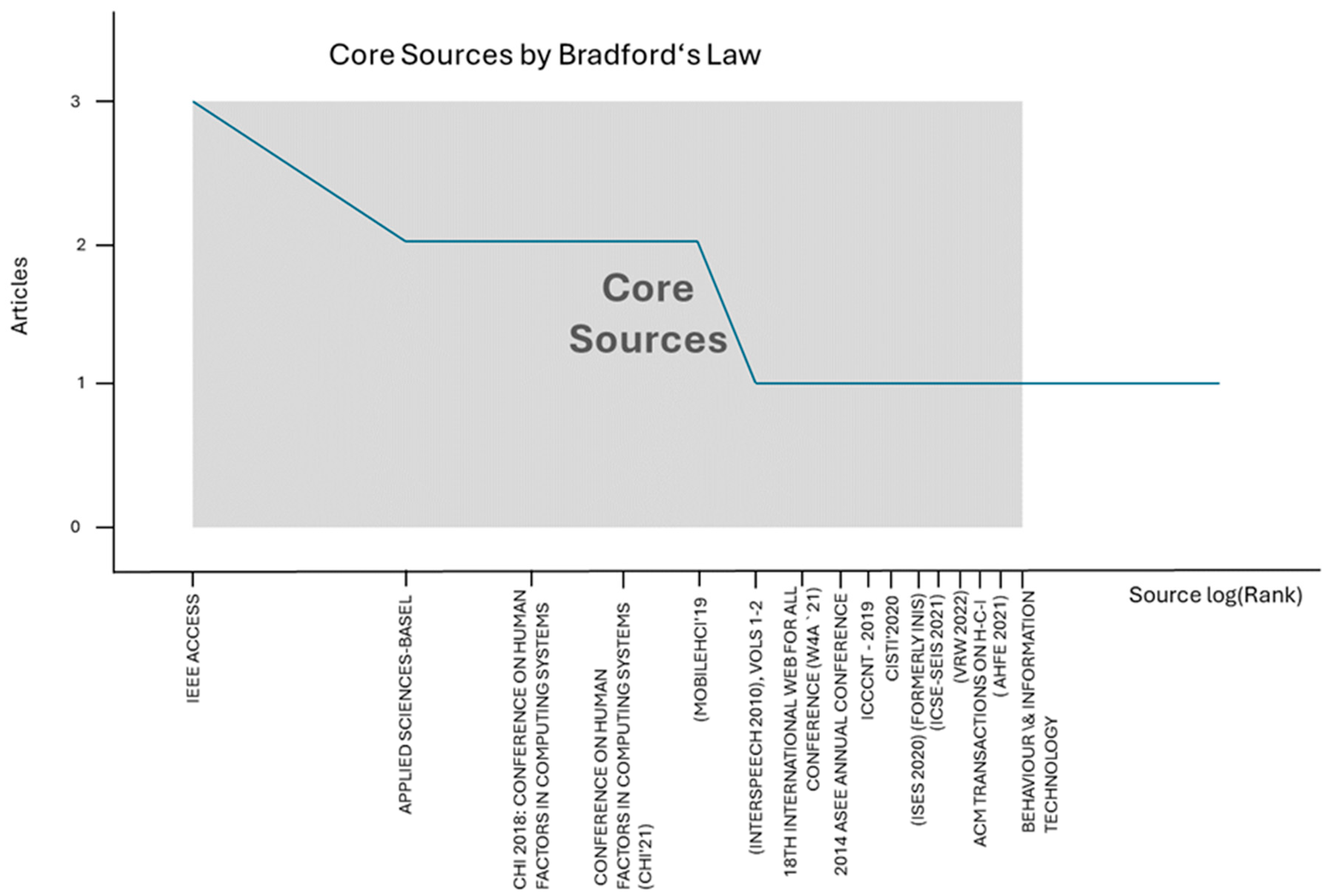

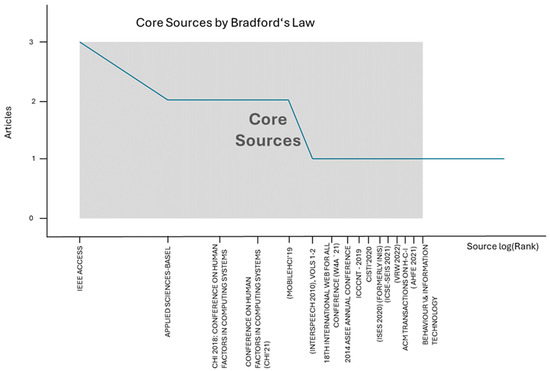

3.6. Source Analysis through Bradford’s Law

Understanding citation patterns through Bradford’s law provides valuable insights into the distribution of citations across publications. Bradford’s law, proposed by Samuel C. Bradford in 1934 [36], posits that scholarly journals can be categorized into core, secondary, and tertiary groups based on their citation frequencies. This law suggests that a small number of journals (or papers) receive a disproportionately large number of citations, while the majority of papers receive fewer citations, following an exponential distribution. By applying Bradford’s law to bibliometric analyses, researchers can identify seminal papers that have significantly influenced the field, elucidating trends in research impact and scholarly communication [36]. This approach facilitates a deeper understanding of the intellectual structure and impact dynamics within specific research domains. Figure 3 shows the Source Analysis through Bradford’s Law.

Figure 3.

Core sources analysis using Bradford’s law.

4. Classification Framework

A content analysis of the 125 articles was carried out to identify (1) a classification framework composed of six research categories that organizes papers according to common issues, and (2) a future research agenda in user experience and voice user interfaces.

The research categories obtained and their main contributions are shown in Table 6. The number of papers in each category is showed in brackets in the first column.

Table 6.

Research categories.

5. Future Research Agenda

Voice user interfaces (VUIs) are becoming increasingly prevalent, yet the study of the user experience of VUIs present several limitations and challenges. Addressing these issues is crucial for advancing VUI technology and enhancing user experiences.

This systematic literature review has allowed us to define a future research agenda in the field (Table 7).

Table 7.

Future research agenda.

6. Discussion

This study has applied the PRISMA systematic literature review approach, which categorized the existing literature in a systematic and valid manner, but also identified the main potential areas for future research. PRISMA allows a replicable, scientific, and transparent process to minimize bias and provides an audit trail of the reviewer’s decisions, procedures, and conclusions, which is a necessary requirement in systematic reviews [83].

The findings shown in this paper contribute to the theory on user experience and voice user interface theory as follows:

- (1)

- According to [12,84] a systematic literature review should be written when there is a substantial body of work in the domain (at least 40 articles for review) and no systematic literature review has been conducted in the field in recent years (within the last 5 years). Therefore, this paper covers a gap in the domain of user experience and voice user interfaces, because this is the first systematic review in the field. Other systematic reviews related to user experience and voice user interfaces focused on different subjects, such as the identification of the scales used for measuring UX of voice assistants, as well as assessing the rigor of operationalization during the development of these scales [44], the synthesis of current knowledge on how proactive behavior has been implemented in voice assistants and under what conditions proactivity has been found more or less suitable [85], or the identification of the usability measures currently used for voice assistants [86];

- (2)

- According to [14], descriptive statistics (e.g., frequency tables) should be used to summarize the basic information on the topic gathered over time in systematic reviews. This paper uses bibliometric statistical analysis techniques to show significant information in the user experience and voice user interface theory domain, such as the top contributing countries, authors, institutions, and sources;

- (3)

- According to [14,87] to make a theoretical contribution, it is not enough to merely report on the previous literature. Systematic literature reviews should focus on identifying new frameworks, promoting the objective discovery of knowledge clusters, or identifying major research streams. Through a content analysis, this paper proposes a classification framework composed of six research categories that shows different ways of contributing to the current state of knowledge on the topic: user experience and usability measurement and evaluation; usability engineering and human–computer interaction; voice assistant design and personalization; privacy, security, and ethical issues; cross-cultural usability and demographic studies; and technological challenges and applications;

- (4)

- According to [12], to make a theoretical contribution, systematic literature reviews can focus on identifying a research agenda. However, this research agenda should follow and accompany another form of synthesis, such as a taxonomy or framework. This paper synthesizes the future research challenges in each research category of the proposed classification framework.

7. Conclusions

To advance in the state of the art in user experience and voice user interface theory, in this paper, a systematic literature review in this field has been carried out. A sample of 125 papers were analyzed to assess the trend of the number of papers published and the number of citations of these papers; to identify the top contributing countries, authors, institutions, and sources; to reveal the findings of the ten most cited papers; and to establish research categories and future research challenges in the area.

This in-depth review focused on the user experience study on VUIs. The review covered the creation of VUIs, the identification of research categories related to user experience in the literature, and considerations of restrictions, difficulties, and research gaps. The results highlight the constant need for VUI design, evaluation, and improvement to enable seamless and positive user experiences.

This review did note a number of gaps and difficulties in the area that offer chances for further research. The lack of standardized evaluation techniques, the scant attention paid to user variety and context, the absence of guidelines for user-centered design, the accuracy of speech recognition, the handling and recovery of errors, the cross-cultural usability evaluation, and the inclusivity and accessibility considerations are a few of them.

Researchers and practitioners can improve the design and evaluation of VUIs and produce voice interactions that are more efficient and user-friendly by bridging these research gaps. In the end, this enhances the human–machine connection and helps VUI technology blend seamlessly into our daily lives. In summary, this review emphasizes the importance of usability evaluation for VUIs and offers helpful tips for the field’s researchers, designers, and developers. We can realize the full potential of VUIs and produce logical and interesting voice interactions that improve user experiences by constantly assessing and enhancing VUIs.

Finally, it is important to highlight the limitations of this work: (1) Only two bibliographical databases have been studied, Scopus and Web of Science. Other databases could be analyzed to extend and contrast the findings; (2) there is a language bias, due to the fact that the search was carried out only in English; (3) other keywords could have been used and might have produced other findings; (4) the comparative method proposed by [21] was used. Other methods, such as network analysis or latent dirichlet allocation (LDA), might be used for research categories identification and may result in other classifications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.D. and R.C.; methodology, A.M.D. and R.C.; software, A.M.D.; validation, A.M.D. and R.C.; formal analysis, A.M.D.; investigation, A.M.D. and R.Ch; data curation, A.M.D. and R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.D. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, A.M.D. and R.C.; visualization, A.M.D. and R.C.; supervision, R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jain, S.; Basu, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kaur, S. Interactive voice assistants–Does brand credibility assuage privacy risks? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.C.; Kim, H.C.; Ji, Y.G. The unit and size of information supporting auditory feedback for voice user interface. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 3071–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Oh, J.; Moon, W.K. Adopting Voice Assistants in Online Shopping: Examining the Role of Social Presence, Performance Risk, and Machine Heuristic. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 2978–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Raju, M.; Selvamuthukumaran, N.; Pramod, M.; Krishna Kumar, B.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Mallik, S. HaCk: Hand Gesture Classification Using a Convolutional Neural Network and Generative Adversarial Network-Based Data Generation Model. Information 2024, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulfagar, L.; Gupta, A.; Mathur, A.; Shrivastava, A. Development and evaluation of usability heuristics for voice user interfaces. In Design for Tomorrow—Volume 1: Proceedings of ICoRD 2021; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 375–385. [Google Scholar]

- Simor, F.W.; Brum, M.R.; Schmidt, J.D.E.; Rieder, R.; De Marchi, A.C.B. Usability evaluation methods for gesture-based games: A systematic review. JMIR Serious Games 2016, 4, e5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.M.; Kölln, K.; Deutschländer, J.; Rauschenberger, M. Design and Evaluation of Voice User Interfaces: What Should One Consider? In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Alrumayh, A.S.; Tan, C.C. VORI: A framework for testing voice user interface interactability. High-Confid. Comput. 2022, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniguez-Carrillo, A.L.; Gaytan-Lugo, L.S.; Garcia-Ruiz, M.A.; Maciel-Arellano, R. Usability Questionnaires to Evaluate Voice User Interfaces. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2021, 19, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A. Toward a user experience tool selector for voice user interfaces. In Proceedings of the 18th International Web for All Conference (W4A ‘21), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–20 April 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.M.; Chalmeta, R. Validation of System Usability Scale as a usability metric to evaluate voice user interfaces. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 10, e1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, M.D.; Visvizi, A.; Daniela, L.; Sarirete, A.; Ordonez De Pablos, P. Social networks research for sustainable smart education. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Marrone, M.; Singh, A.K. A Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R.; Ruíz-Navarro, J. Changes in the intellectual structure of strategic management research: A bibliometric study of the Strategic Management Journal, 1980–2000. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 981–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, F.J.; Merigó, J.M.; Valenzuela-Fernández, L.; Nicolás, C. Fifty years of the European Journal of Marketing: a bibliometric analysis. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 439–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derviş, H. Bibliometric analysis using bibliometrix an R package. J. Scientometr. Res. 2019, 8, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, D. Comparative method in the 1990s. CP Newsl. Comp. Politics Organ. Sect. Am. Political Sci. Assoc. 1998, 9, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Seuring, S.; Gold, S. Conducting content analysis-based literature reviews in supply chain management. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmeta, R.; Barbeito-Caamaño, A.M. Framework for using online social networks for sustainability awareness. Online Inf. Rev. 2024, 48, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egghe, L. Theory and Practise of the g-Index; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, P.D.; Campiteli, M.G.; Kinouchi, O. Is it possible to compare researchers with different scientific interests? Scientometrics 2006, 68, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, C.; Furqan, A.; Nebolsky, J.; Caro, K.; Zhu, J. Patterns for how users overcome obstacles in voice user interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Alepis, E.; Patsakis, C. Monkey says, monkey does: Security and privacy on voice assistants. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 17841–17851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, E.; Weber, A. What can I say? addressing user experience challenges of a mobile voice user interface for accessibility. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Florence, Italy, 6–9 September 2016; pp. 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sayago, S.; Neves, B.B.; Cowan, B.R. Voice assistants and older people: some open issues. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, Dublin Ireland, 22–23 August 2019; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, C.M.; Furqan, A.; Zhu, J. The impact of user characteristics and preferences on performance with an unfamiliar voice user interface. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, H. Effects of user experience on user resistance to change to the voice user interface of an in-vehicle infotainment system: Implications for platform and standards competition. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Roy, P.; Arpnikanondt, C.; Thapliyal, H. The effect of trust and its antecedents towards determining users’ behavioral intention with voice-based consumer electronic devices. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, S.; Porcheron, M.; Fischer, J.E.; Candello, H.; McMillan, D.; McGregor, M.; Moore, R.J.; Sikveland, R.; Taylor, A.S.; Velkovska, J.; et al. Voice-based conversational ux studies and design. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Seaborn, K.; Urakami, J. Measuring voice UX quantitatively: A rapid review. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, S.C. Sources of information on specific subjects. Engineering 1934, 137, 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A.M.; Kollmorgen, J.; Hinderks, A.; Schrepp, M.; Rauschenberger, M.; Escalona, M.J. Validation of the Ueq+ Scales for Voice Quality. SSRN 2024, preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo, R.; Friel, M.; Grassia, M.G.; Marino, M.; Zavarrone, E. Importance Performance Matrix Analysis for Assessing User Experience with Intelligent Voice Assistants: A Strategic Evaluation. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bala, P.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Behera, R.K. Exploring antecedents impacting user satisfaction with voice assistant app: A text mining-based analysis on Alexa services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, G. Towards Auditory Interaction: An Analysis of Computer-Based Auditory Interfaces in Three Settings. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Ulm, Ulm, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mont’Alvão, C.; Maués, M. Personified Virtual Assistants: Evaluating Users’ Perception of Usability and UX. In Handbook of Usability and User-Experience; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 269–288. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W.; Shao, B.; Zhang, Y. How Does Interactivity Shape Users’ Continuance Intention of Intelligent Voice Assistants? Evidence from SEM and fsQCA. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 867–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.M.; Deutschländer, J.; Kölln, K.; Rauschenberger, M.; Escalona, M.J. Exploring the context of use for voice user interfaces: Toward context-dependent user experience quality testing. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2024, 36, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, L.I.D.; Babakerkhell, M.D.; Mongkolnam, P.; Chongsuphajaisiddhi, V.; Funilkul, S.; Pal, D. A review of subjective scales measuring the user experience of voice assistants. IEEE Access. 2024, 12, 14893–14917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, T.; Fitzmaurice, G.; Attar, R. A survey of software learnability: metrics, methodologies and guidelines. In Proceedings of the Sigchi Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 4–9 April 2009; pp. 649–658. [Google Scholar]

- Zargham, N.; Bonfert, M.; Porzel, R.; Doring, T.; Malaka, R. Multi-agent voice assistants: An investigation of user experience. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, Leuven, Belgium, 5–8 December 2021; pp. 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Faden, R.R.; Beauchamp, T.L.; Kass, N.E. Informed consent, comparative effectiveness, and learning health care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Rough, D.; Bleakley, A.; Edwards, J.; Cooney, O.; Doyle, P.R.; Clark, L.; Cowan, B.R. October. See what I’m saying? Comparing intelligent personal assistant use for native and non-native language speakers. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Oldenburg, Germany, 5–8 October 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Murad, C.; Tasnim, H.; Munteanu, C. Voice-First Interfaces in a GUI-First Design World”: Barriers and Opportunities to Supporting VUI Designers On-the-Job. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, Glasgow, UK, 26–28 July 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jannach, D.; Manzoor, A.; Cai, W.; Chen, L. A survey on conversational recommender systems. ACM Comput. Surv. CSUR 2021, 54–55, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ham, S.; Promann, M.; Devarapalli, H.; Kwarteng, V.; Bihani, G.; Ringenberg, T.; Bilionis, I.; Braun, J.E.; Rayz, J.T.; et al. MySmartE-A Cloud-Based Smart Home Energy Application for Energy-Aware Multi-unit Residential Buildings. ASHRAE Trans. 2023, 129, 667–675. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Ham, S.; Promann, M.; Devarapalli, H.; Bihani, G.; Ringenberg, T.; Kwarteng, V.; Bilionis, I.; Braun, J.E.; Rayz, J.T.; et al. MySmartE–An eco-feedback and gaming platform to promote energy conserving thermostat-adjustment behaviors in multi-unit residential buildings. Build. Environ. 2022, 221, 109252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowdermilk, T. User-Centered Design: A Developer’s Guide to Building User-Friendly Applications; O‘Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dirin, A.; Laine, T.H. User experience in mobile augmented reality: emotions, challenges, opportunities and best practices. Computers 2018, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, M.; Bevacqua, E. A review of virtual assistants’ characteristics: Recommendations for designing an optimal human–machine cooperation. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2022, 22, 050904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Finn, K. Designing User Interfaces for an Aging Population: Towards Universal Design; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.; Epley, N. Who sees human? The stability and importance of individual differences in anthropomorphism. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völkel, S.T.; Schoedel, R.; Kaya, L.; Mayer, S. User perceptions of extraversion in chatbots after repeated use. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke, K.; Bernstein, A. Improving performance, perceived usability, and aesthetics with culturally adaptive user interfaces. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. TOCHI 2011, 18, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Nebe, K.; Lallemand, C. Sentence Completion as a User Experience Research Method: Recommendations From an Experimental Study. Interact. Comput. 2024, 36, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, T.; Akbar, M.S.; Ahmed, S.; Sarfraz, A.; Sarfraz, Z.; Sarfraz, M.; Felix, M.; Cherrez-Ojeda, I. A systematic review of internet of things in clinical laboratories: Opportunities, advantages, and challenges. Sensors 2022, 22, 8051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, R.; Fahim, M.F.H.; Hassan, M.A.M.; Rai, C.; Islam, M.M.; Sah, R.K. Analyzing the Effectiveness of Voice-Based User Interfaces in Enhancing Accessibility in Human-Computer Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 13th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT), Jabalpur, India, 6–7 April 2024; pp. 777–781. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Xia, C.; Xu, S.; Zhang, X. StealthyIMU: Stealing Permission-protected Private Information From Smartphone Voice Assistant Using Zero-Permission Sensors; Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium: San Diego, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Consumer trust, perceived security and privacy policy: three basic elements of loyalty to a web site. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2006, 106, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; Munteanu, C.; Ramanand, N.; Tan, Y.R. VUI influencers: How the media portrays voice user interfaces for older adults. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, Bilbao, Spain, 27–29 July 2021; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pyae, A.; Scifleet, P. Investigating differences between native English and non-native English speakers in interacting with a voice user interface: A case of Google Home. In Proceedings of the 30th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction, Melbourne, Australia, 4–7 December 2018; pp. 548–553. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, C. Designing Voice User Interfaces: Principles of Conversational Experiences; O‘Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Terzopoulos, G.; Satratzemi, M. Voice assistants and smart speakers in everyday life and in education. Inform. Educ. 2020, 19, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. Exploring the User Experience of an AI-based Smartphone Navigation Assistant for People with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the 15th Biannual Conference of the Italian SIGCHI Chapter, Torino, Italy, 20–22 September 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pyae, A. A usability evaluation of the Google Home with non-native English speakers using the system usability scale. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 2022, 26, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.L.; Beygi, S.; Fazel-Zarandi, M.; Gao, Q.; Cervone, A.; Wang, W.Y. Towards large-scale interpretable knowledge graph reasoning for dialogue systems. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.10610. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y. Emotion-Aware Voice Interfaces Based on Speech Signal Processing. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Ulm, Ulm, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, L.; Chaudhuri, B.; Bhalla, A. Understanding technology as situated practice: everyday use of voice user interfaces among diverse groups of users in urban India. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, A.K.; Fu, J.; Zygouras, V.; Park, H.W.; Breazeal, C. Speed dating with voice user interfaces: understanding how families interact and perceive voice user interfaces in a group setting. Front. Robot. AI 2022, 8, 730992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, J.J.; Fischer, J.; Hong, J.; Bentley, F.R.; Munteanu, C.; Hiniker, A.; Tsai, J.Y.; Ammari, T. Panel: voice assistants, UX design and research. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sekkat, C.; Leroy, F.; Mdhaffar, S.; Smith, B.P.; Estève, Y.; Dureau, J.; Coucke, A. Sonos Voice Control Bias Assessment Dataset: A Methodology for Demographic Bias Assessment in Voice Assistants. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.19342. [Google Scholar]

- Varsha, P.S.; Akter, S.; Kumar, A.; Gochhait, S.; Patagundi, B. The impact of artificial intelligence on branding: a bibliometric analysis (1982–2019). J. Glob. Inf. Manag. JGIM 2021, 29, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karat, C.M.; Vergo, J.; Nahamoo, D. Conversational interface technologies. In The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, R. Supporting Caregivers in Complex Home Care: Towards Designing a Voice User Interface. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, A.; Thompson, H.; Demiris, G. A systematic review of the use of technology for reminiscence therapy. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41 (Suppl. S1), 51S–61S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, M.T.; Penney, S.P.; Landman, A.; Elias, J.; Mullen, B.; Sipe, H.; Hartog, B.; Richard, E.; Xu, C.; Solomon, D.H. User experience with a voice-enabled smartphone app to collect patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2022, 40, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederich, S.; Brendel, A.B.; Morana, S.; Kolbe, L. On the design of and interaction with conversational agents: An organizing and assessing review of human-computer interaction research. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2022, 23, 96–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Lim, W.M.; O’Cass, A.; Hao, A.W.; Bresciani, S. Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, O1–O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérubé, C.; Nißen, M.; Vinay, R.; Geiger, A.; Budig, T.; Bhandari, A.; Kocaballi, A.B. Proactive behavior in voice assistants: A systematic review and conceptual model. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 14, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutsinma, F.L.I.; Pal, D.; Funilkul, S.; Chan, J.H. A systematic review of voice assistant usability: An ISO 9241–11 approach. SN Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Marc, W.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).