Abstract

The field of probabilistic metric spaces has an intrinsic interest based on a blend of ideas drawn from metric space theory and probability theory. The goal of the present paper is to introduce and study new ideas in this field. In general terms, we investigate the following concepts: linearly ordered families of distances and associated continuity properties, geometric properties of distances, finite range weak probabilistic metric spaces, generalized Menger spaces, and a categorical framework for weak probabilistic metric spaces. Hopefully, the results will contribute to the foundations of the subject.

1. Introduction

1.1. Preliminary Remarks

The original and primary source on probabilistic metric spaces is [1]. Current research in the field appears to fall into three basic areas: (i) foundational topics [2,3,4,5], (ii) fixed point theory [6,7,8], and (iii) models for applications [9,10]. The primary emphasis in current research seems to be on area (ii). We discuss this topic further in the section on Discussion and Future Work. The admittedly lofty aim of the present paper is to rejuvenate the foundations of the subject by reexamining the original concepts before most research was devoted to Menger spaces and triangle functions.

1.2. Organization

The main body of the paper consists of three sections. Section 2 presents background material on weak probabilistic metric spaces (WPMSs) and introduces the notions of finite range WPMSs and linearly ordered families of distances. Section 3 presents results on constructing Menger spaces and approximating them by finite range Menger spaces, as well as characterizing the generalized Menger spaces. Section 4 introduces a categorical framework for WPMSs and establishes several key properties of the category WP. It also shows that the Menger spaces are a reflective subcategory of WP. Section 5 discusses the potential contributions of the work. There is also an Appendix A devoted to an overview of distance-spaces that includes several results used in other sections of the paper.

1.3. Conventions

We use the symbol □ to denote the end of proofs. The symbol N (resp. Z or R) denotes the natural numbers (resp. integers or real numbers), N+ = N\{0}, and R+ = [0, +∞). The symbol I denotes [0, 1]. For each x ∈ R, ⌊x⌋ (resp. ⌈x⌉) denotes the largest integer ≤ x (resp. smallest integer ≥ x). For a set S, idS: S ⟶ S denotes the identity mapping, and for each A ⊆ S, χA: S ⟶ {0, 1} (resp. inclA: A ⟶ S) denotes the characteristic function of A (resp. the inclusion mapping). The symbol P(S) denotes the power-set of S and PF+(S) denotes the family of non-empty finite subsets of S. Given sets S and T, S ∪d T denotes their disjoint union, F(S, T) is the family of mappings S ⟶ T, and for each t ∈ T, constt: S ⟶ T is the constant mapping at t. A mapping φ: R+⟶ R+ is a modulus of continuity if φ is non-decreasing and φ(0+) = φ(0) = 0.

2. Weak Probabilistic Metric Spaces

2.1. Background

Here we present the notion of a weak probabilistic metric space, the associated family of distances, and several examples. The reader familiar with these ideas can skip to Section 2.2.

Define the set of distribution functions

and let ≦ denote the point-wise order on Δ. The symbol H denotes the member of Δ defined by H(x) = 0 if x ≤ 0 and H(x) = 1 if x > 0. Let Δ+ = {F ∈ Δ | F(0) = 0}. If F ∈ Δ+, then F(x) = 0 for each x < 0, so we can assume that R+ is the domain of each member of Δ+.

Δ = {F: R ⟶ I | F is left-continuous, non-decreasing, inf(F) = 0, and sup(F) = 1}

A weak probabilistic metric space (WPMS) consists of a set S and F = {Fpq | p, q ∈ S} ⊆ Δ+ that satisfies the following properties:

(w1) For each p ∈ S, Fpp = H.

(w2) For each p, q ∈ S, Fpq = Fqp.

(w3) For each distinct p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+, Fpq(x) = Fqr(y) = 1 ⟹ Fpr(x + y) = 1.

The standard interpretation is that for p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+, Fpq(x) is the probability that the distance from p to q is less than x. For example, Fpq(0) = 0 implies a zero probability that the distance between points p and q is less than 0. Property (w3) postulates a probabilistic triangle inequality: if the probability that the distance from p to q is less than x and the probability that the distance from q to r is less than y, then the probability that the distance from p to r is less than x + y. We note that (w3) always holds if p, q, and r are not distinct; for instance, if p = q, then Fpr(y) = 1, so since Fpr is non-decreasing, Fpr(x + y) = 1.

The property (w1) is a weaker version of the following property:

(w1′) For each p, q ∈ S, Fpq = H ⇔ p = q.

Otherwise, our definition of a WPMS agrees with the one used in ([1], 1.4.2). (Section 3.1). In the sequel, a pair (S, F) denotes a WPMS. Frequently, we also use the alternate representation (S, F), where F: S × S ⟶ Δ+ is defined by F(p, q) = Fpq.

We distinguish the following types of WPMSs. If (S, F) is a WPMS and (w1′) holds, then we say that (S, F) is a WPMS+. We say that a WPMS (S, F) is trivial if for each p, q ∈ S, Fpq = H. More generally, we say that a WPMS (S, F) is special if for each p, q ∈ S, Fpq−1(1) ≠ ∅.

Example 2.1.1.

The WPMS (S, G) determined by a pseudometric space (S, γ) ([1], 1.2.5).

For p, q ∈ S, define Gpq: R+ ⟶ I by Gpq(x) = H(x − γ(p, q)). Using the standard interpretation, the probability is zero that the distance from p to q is less than γ(p, q).

Since the motivation for a WPMS is to model a probabilistic situation, it is natural to use a distribution function to define the members of F. The next example illustrates this idea.

Example 2.1.2.

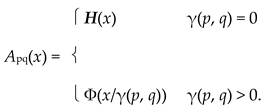

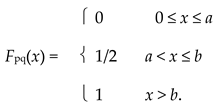

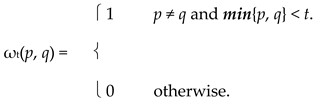

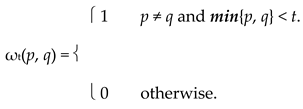

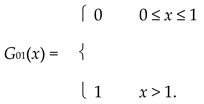

The 1-simple WPMS (S, A, γ, Φ) based on a pseudometric space (S, γ) and a fixed distribution function Φ ∈ Δ+\{H} ([1], 8.6.1). For p, q ∈ S, define Apq: R+ ⟶ I by

|

If γ(p, q) = 0, then the probability is one that the distance from p to q is less than any positive number. If γ(p, q) > 0, then the probability that the distance from p to q is less than x is determined by the choice of Φ. In the same manner, we can define an α-simple WPMS (S, A, γ, Φ, α) for each 0 < α < 1 by using Φ(x/γ(p, q)α) in place of Φ(x/γ(p, q)).

Example 2.1.3.

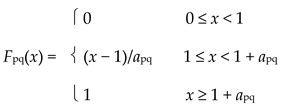

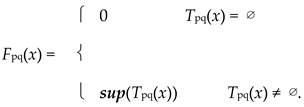

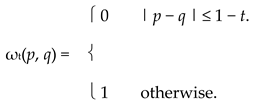

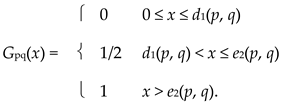

For a distinct pair p, q ∈ S = R+, define Fpq: R+ ⟶ I by

|

Example 2.1.4.

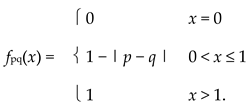

For each p, q ∈ R satisfying | p − q | < 1, define fpq: R+ ⟶ I by

|

Also, for each p, q ∈ R, define Fpq: R+ ⟶ I by

|

Then (R, F) is a WPMS+.

There is a natural way to associate distances with a WPMS. For each F ∈ Δ+, define the non-decreasing mapping F^: (0, 1] ⟶ [0, +∞] by F^(t) = sup(X(t)), where X(t) = {x ∈ R+ | F(x) < t} ([1], Section 4.4). Since F(0) = 0, X(t) ≠ ∅ for each t > 0 and if t < 1, then X(t) is also bounded since sup(F) = 1, so F^(t) is well-defined. If F−1(1) ≠ ∅, then F^(1) is also well-defined.

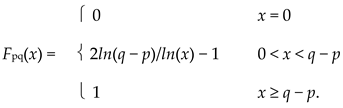

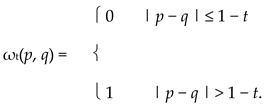

Given a WPMS (S, F) and 0 < t < 1, define ωt: S × S ⟶ R+ by

and define the extended real-valued mapping ω1: S × S ⟶ [0, +∞] by ω1(p, q) = Fpq^(1).

ωt(p, q) = Fpq^(t) = sup{x ∈ R+ | Fpq(x) < t}

The ωt’s correspond to the dc’s introduced in ([1], 8.2.3). For each 0 < t < 1, ωt is a distance, i.e., for each p, q ∈ S, ωt(p, p) = 0 and ωt(p, q) = ωt(q, p) (Appendix A.1). In general, ωt is not a semi-metric; that is, ωt(p, q) = 0 can occur for distinct p and q.

Given a WPMS (S, F), let

denote the set of well-defined distances. Notice that ΩF is a linearly ordered family of distances: if 0 < s < t < 1, then ωs ≤ ωt.

ΩF = {ωt | 0 < t < 1}

For an α-simple space (S, A, γ, Φ, α) (Example 2.1.2), ωt = Φ^(t)γα for each 0 < t ≤ 1 and in Example 2.1.3, ωt(p, q) = 1 + tapq for distinct p, q ∈ S and 0 < t < 1. Notice that in both cases, each ωt is a pseudometric. In the following example, the distances are not pseudometrics.

Example 2.1.5.

For each p, q ∈ R+, define Fpq: R+ ⟶ I by

Fpq(x) = [H(x − | p − q |) + H(x − | p2 − q2 |)]/2.

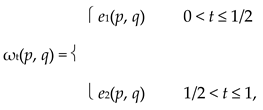

Then (R+, F) is a special WPMS+. As an illustration, if 0 < a = | p − q | < b = | p2 − q2 |, then

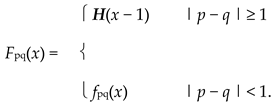

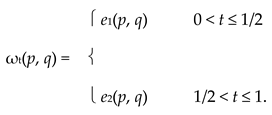

|

The distances fall into two groups:

where e1 and e2 are defined by e1(p, q) = min{a, b} and e2(p, q) = max{a, b}, respectively. The mapping e2 is a metric, but e1 is not a pseudometric since the triangle inequality does not hold. In fact, we can make an even stronger statement. For n ∈ N+, let xn = n + 1/n, yn = n, and zn = -n + 1/n2. Then e1(xn, yn) + e1(yn, zn) = 3/n − 1/n4 ⟶ 0 as n ⟶ +∞, but e1(xn, zn) = 2 + 1/n2 + 2/n − 1/n4 > 2 for each n. Therefore, (R+, e1) does not satisfy the condition (wtc) discussed in Section 3.3.

|

2.2. Preliminary Results

In this subsection, we present some basic results that provide further background for the reader as well as a basis for subsequent sections. In proofs, we often assume that p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+ without explicitly mentioning the sets.

The first result summarizes the relationships between the values of the distribution functions and distances. We use it repeatedly in the text. The proof is elementary, but we include part of it to familiarize the reader with the notation.

Lemma 2.2.1.

The following statements hold for each WPMS (S, F) and 0 < t ≤ 1.

- (a)

- ωt(p, q) < x ⟹ Fpq(x) ≥ t.

- (b)

- Fpq(x) > t ⟹ ωt(p, q) < x.

- (c)

- Fpq(x) ≥ t ⟹ ωt(p, q) ≤ x and ωu(p, q) < x for each 0 < u < t.

Proof.

(b): Suppose y = ωt(p, q) ≥ x. By the left-continuity of Fpq, for each ε > 0, there is yε < y such that Fpq(y) − Fpq(yε) < ε. Hence, Fpq(yε) ≤ t, so Fpq(y) < t + ε. Since the inequality holds for each ε > 0, Fpq(y) ≤ t. Therefore, Fpq(x) ≤ t since Fpq is non-decreasing. □

To check when a member of ΩF is a pseudometric, it is useful to introduce the following predicate. Given a WPMS (S, F) and 0 < t ≤ 1, define

(&t): ∀p, q, r ∈ S, ∀x, y ∈ R+ · Fpq(x) ≥ t and Fqr(y) ≥ t ⟹ Fpr(x + y) ≥ t.

It follows from property (w3) that (&1) always holds. The next result is implicit in the literature.

Prop 2.2.1.

Suppose (S, F) is a WPMS and 0 < t < 1.

- (a)

- If (&t) holds, then ωt is a pseudometric.

- (b)

- If ωs is a pseudometric for each 0 < s < t, then (&t) holds.

Proof.

(a): Let ε > 0 and choose x, y such that ωt(p, q) < x < ωt(p, q) + ε/2 and ωt(q, r) < y < ωt(q, r) + ε/2.

By Lemma 2.2.1(a), Fpq(x) ≥ t and Fqr(y) ≥ t, so by (&t), Fpr(x + y) ≥ t. Hence, by Lemma 2.2.1(c), ωt(p, r) ≤ x + y. Therefore, ωt(p, r) < ωt(p, q) + ωt(q, r) + ε for each ε > 0, so ωt satisfies the triangle inequality.

(b): If (&t) does not hold, then there exists p, q, r, x, and y such that Fpq(x) ≥ Fqr(y) ≥ t > Fpr(x + y). Choose Fpr(x + y) < s < t. By Lemma 2.2.1(b), ωs(p, q) < x and ωs(q, r) < y. Since Fpr(x + y) < s, by Lemma 2.2.1(a), x + y ≤ ωs(p, r). Therefore, ωs(p, q) + ωs(q, r) < x + y ≤ ωs(p, r) shows that ωs does not satisfy the triangle inequality. □

The reader can see from the previous proof that Lemma 2.2.1 might need to be used repeatedly. Therefore, in future proofs, we only use it implicitly.

The following elementary result complements the preceding result.

Lemma 2.2.2.

The following statements are equivalent for a WPMS (S, F).

- (a)

- (S, F) is special.

- (b)

- ω1 is a real-valued mapping.

- (c)

- ω1 is a pseudometric.

Proof.

The implication (a) ⟹ (b) follows from the definition.

(b) ⟹ (c): Let x = ω1(p, q) and y = ω1(q, r). By definition, Fpq(x + ε/2) = 1 and Fqr(y + ε/2) = 1 for each ε > 0, so by (w3), Fpr(x + y + ε) = 1. Hence, ω1(p, r) ≤ x + y + ε for each ε > 0, so ω1 satisfies the triangle inequality.

(c) ⟹ (a): Since ω1(p, q) is finite, Fpq(ω1(p, q) + 1) = 1. Hence, (S, F) is special. □

The next two results present conditions that are equivalent to ΩF being a family of pseudometrics and metrics, respectively.

Prop 2.2.2.

The following statements are equivalent for a WPMS (S, F).

- (a)

- For each 0 < t < 1, ωt is a pseudometric.

- (b)

- For each 0 < t < 1, (&t) holds.

- (c)

- For each p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+, Fpr(x + y) ≥ min{Fpq(x), Fqr(y)}.

Proof.

The implication (c) ⟹ (a) follows from Prop 2.2.1(a) since (c) implies that each (&t) holds. The implication (a) ⟹ (b) follows from Prop 2.2.1(b).

(b) ⟹ (c): Let s = Fpq(x) and t = Fqr(y). Clearly, if s = 0 or t = 0, then the inequality in (c) holds. Otherwise, if s ≤ t, then by (&s), Fpr(x + y) ≥ s = min{s, t}. If s > t, then Fpr(x + y) ≥ t = min{s, t} follows from (&t). □

The following result is not used in the rest of the paper, but it is a natural companion to the previous proposition.

Prop 2.2.3.

The following statements are equivalent for a WPMS (S, F).

- (a)

- For each 0 < t < 1, ωt is a metric.

- (b)

- (i) For each p ≠ q, Fpq is right-continuous at 0.(ii) For each p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+, Fpr(x + y) ≥ min{Fpq(x), Fqr(y)}.

Proof.

(a) ⟹ (b): Suppose p ≠ q and let n ∈ N\{0, 1}. Since ω1/n(p, q) > 0, there is 0 < εn < 1/n such that εn < ω1/n(p, q). Hence, Fpq(εn) ≤ 1/n. Therefore, Fpq(0+) = limh⟶0+Fpq(h) = 0, which establishes (i). Condition (ii) follows from Prop 2.2.2.

(b) ⟹ (a): By Prop 2.2.2 and (ii), each ωt is a pseudometric. Assume that p ≠ q and ωt(p, q) = 0 for some 0 < t < 1. Then each Fpq(1/n) ≥ t, so Fpq is not right-continuous at 0, which contradicts (i). □

We note that right continuity can be characterized by using the interplay between distances and distributions. Given a WPMS (S, F), for each x ∈ R+ and p, q ∈ S, define the predicate

(#x,p,q) ≡ 0 < t ≤ 1 and ωt(p, q) = x ⟹ Fpq(x) = t.

Then (S, F) satisfies (#x,p,q) if and only if Fpq is right-continuous at x. We leave this statement for the reader’s consideration.

The condition stated in ([5], (IV)) is equivalent to (&t) and the equivalence of parts (a) and (b) in Prop 2.2.2 and Prop 2.2.3 is proved in ([5], Lemma 1 and Theorem 1). Also, Prop 2.2.2(a) is proved in ([1], 8.2.3) and Prop 2.2.3 is essentially established in ([11], Theorems 9 and 10).

2.3. Reconstruction and Representation

The first result shows that for any WPMS (S, F), we can always reconstruct the family F = {Fpq} from ΩF.

Prop 2.3.1.

For each WPMS (S, F), p, q

∈ S, and x ∈ R+, Fpq(x) = sup{0 < t < 1 | ωt(p, q) < x}, where ΩF = {ωt}.

Proof.

For the proof, we suppress the pairs (p, q) and subscripts pq.

Let x ∈ R+ and T = {0 < t < 1 | ωt < x}. Define v = 0 if T = ∅ and v = sup(T) if T ≠ ∅. If T = ∅, then ωt ≥ x for each 0 < t < 1, so F(x) ≤ t for each 0 < t < 1. Hence, F(x) = v. If T ≠ ∅, then for each t ∈ T, F(x) ≥ t. Hence, v ≤ F(x). If v < F(x), choose v < r < F(x). Then ωr < x, so r ∈ T. Hence, v ≥ r, which is a contradiction. Therefore, v = F(x). □

We remark that the following definition of ωt is used in ([5], (I)): ωt(p, q) = inf{x | Fpq(x) > t}. Then ([5], (III)) asserts that Fpq(x) = sup{t | ωt(p, q) < x}.

Next, we present the first new idea in the paper. We say that a WPMS (S, F) has finite range if Rng(F) = ∪{Rng(Fpq) | p, q ∈ S} is a finite set. For this type of WPMS, we can establish the following representation theorem. Also, we will revisit these types of WPMSs in Section 3.2.

Theorem 2.3.1.

Assume that the WPMS (S, F) has the finite range Rng(F) = {ti | 0 ≤ i ≤ n}, where t0 = 0 < t1 < … < tn = 1 and ΩF = {ωt}. Then the following statements hold:

- (a)

- ΩF = {ωt(i) | 1 ≤ i ≤ n} and | ΩF | = n.

- (b)

- For each p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+, Fpq(x) = ∑{(ti+1 − ti)H(x − ωt(i+1)(p, q)) | 0 ≤ i < n}.

Proof.

In various places, we write t(i) in place of ti.

(a): Given 0 < t ≤ 1, choose 1 ≤ i ≤ n such that ti−1 < t ≤ ti. Then for p, q ∈ S,

ωt(p, q) = sup{x | Fpq(x) < t} = sup{x | Fpq(x) < ti} = ωt(i)(p, q).

This establishes ωt = ωt(i). Let 1 ≤ i < n and choose p, q, and y such that Fpq(y) = ti. Then z = ωt(i+1)(p, q) ≥ y. Since Fpq is left-continuous, there exists 0 < x < y such that Fpq(x) = ti. If ωt(i)(p, q) ≥ z, then ωt(i)(p, q) > x, so Fpq(x) < ti, which gives a contradiction. Therefore, we have ωt(i)(p, q) < z = ωt(i+1)(p, q). It follows that | ΩF | = n.

(b): For each p, q ∈ S, define Gpq by Gpq(x) = ∑{(ti+1 − ti)H(x − ωt(i+1)(p, q)) | 0 ≤ i < n}.

- (1)

- (S, G) is a WPMS.

[Each Gpq ∈ Δ+ since H is left-continuous and Gpq(x) = 1 for x > ω1(p, q). It is easy to show that (w1) and (w2) hold. Suppose Gpq(x) = Gqr(y) = 1. Since (S, F) is special, by Lemma 2.2.2, ω1 is a pseudometric. Then by definition, x > ω1(p, q) and y > ω1(q, r), so x + y > ω1(p, r). Therefore, Gpr(x + y) = 1, so (w3) holds.]

Let ΩG = {νt}.

- (2)

- νt = ωt for each 0 < t ≤ 1.

[Let p, q ∈ S and choose 1 ≤ i ≤ n such that ti−1 < t ≤ ti. Since {ωt} is linearly ordered, by definition, Rng(G) ⊆ {ti | 0 ≤ i ≤ n}. Hence, νt(p, q) = sup{x | Gpq(x) < t} = sup{x | Gpq(x) < ti} = νt(i)(p, q). By definition, if Gpq(x) ≤ ti−1, then x ≤ ωt(i)(p, q), so νt(i)(p, q) = sup{x | Gpq(x) < ti} ≤ ωt(i)(p, q). If Fpq(x) < ti, then x ≤ ωt(i)(p, q), so Gpq(x) < ti. Therefore,

ωt(i)(p, q) = sup{x | Fpq(x) < ti} ≤ sup{x | Gpq(x) < ti} = νt(i)(p, q).

This establishes ωt(i) = νt(i).]

Since (S, F) is a WPMS and by (1), (S, G) is a WPMS, it follows from (2) and Prop 2.3.1 that F = G. □

The WPMS (S, F) in Example 2.1.5 illustrates Theorem 2.3.1 since

Fpq(x) = [H(x − | p − q |) + H(x − | p2 − q2 |)]/2 = [H(x − e1(a, b)) + H(x − e2(a, b))]/2.

In this case, | ΩF | = {e1, e2} and Rng(e1) = Rng(e2) = R+. Therefore, even for a WPMS with a finite range, the distances may not have finite ranges. In fact, Example 3.1.1 shows that the distances can have the values {0, 1} without the WPMS itself having a finite range.

The following result is an easy consequence of the previous theorem that fits nicely with one’s intuition. We can view it as a “0-1 law”: if the probability is 0 or 1 that the distance from p to q is less than some value, then the distance is described by a unique pseudometric.

Corollary 2.3.1.

The following statements are equivalent for a WPMS (S, F).

- (a)

- Rng(F) = {0, 1}.

- (b)

- (S, F) is determined by a pseudometric.

- (c)

- ΩF = {ω1} and ω1 is a pseudometric.

- (d)

- | ΩF| = 1.

Proof.

(a) ⟹ (b): By Theorem 2.3.1, Fpq(x) = H(x − ω1(p, q)) for each p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+. Since (S, F) is special, by Lemma 2.2.2, ω1 is a pseudometric.

(b) ⟹ (c): Suppose Fpq(x) = H(x − ω(p, q)) for a pseudometric ω and each p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+. Then for each 0 < t ≤ 1, ωt(p, q) = sup{x | Fpq(x) < t} = sup{x | x ≤ ω(p, q)} = ω(p, q).

Clearly, (c) ⟹ (d).

¬(a) ⟹ ¬(d): If 0 < Fpq(x) < 1 for some p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+, choose 0 < s < Fpq(x) < t < 1. Then ωs(p, q) < x ≤ ωt(p, q) shows that ωs ≠ ωt. Hence, | ΩF | > 1. □

2.4. Linearly Ordered Families

Here, we present the second new idea in the paper—the application of linearly ordered families of distances. For clarity, we are referring to a family Ω = {ρt | 0 < t < 1} of distances defined on a set S that satisfies ρs ≤ ρt for each 0 < s < t < 1. We say that Ω satisfies the left-continuity property (lcp) (resp. right-continuity property (rcp)) if ρt = sup{ρs | 0 < s < t} (resp. ρt = inf{ρs | t < s < 1} for each 0 < t < 1.

Prop 2.4.1.

The following statements hold for a WPMS (S, F).

- (a)

- The family ΩF = {ωt | 0 < t < 1} satisfies (lcp) and if (S, F) is a special WPMS, then ω1 = sup{ωt | 0 < t < 1}.

- (b)

- The family ΩF satisfies (rcp) if and only if (#): for each distinct pair p, q ∈ S, Fpq is strictly increasing on Fpq−1(0, 1).

Proof.

(a): Let 0 < t < 1. For p, q ∈ S and ε > 0, there is x ∈ R+ such that ωt(p, q) − ε < x and Fpq(x) < t. If Fpq(x) < s < t, then ωs(p, q) ≥ x > ωt(p, q) − ε. Therefore, ωt = sup{ωs | 0 < s < t}. If (S, F) is special, then by Lemma 2.2.2, ω1 is real-valued, so by a similar argument, we can establish that ω1 = sup{ωt | 0 < t < 1}.

(b): Suppose ΩF satisfies (rcp) and p, q ∈ S is a distinct pair. Suppose 0 < Fpq(x) = Fpq(y) = t < 1 for some 0 ≤ x < y. If t < s < 1, then ωs(p, q) ≥ y and ωt(p, q) ≤ x, so ωt(p, q) < inf{ωs(p, q) | t < s < 1}, which is a contradiction. Therefore, (#) holds. Conversely, if (#) holds and (rcp) does not, then a = ωt(p, q) < b = inf{ωs(p, q) | t < s < 1} for some p and q. By the definition of ωt, Fpq(x) ≥ t for each a < x and for each x < b and t < s < 1, Fpq(x) < s, so Fpq(x) ≤ t. Therefore, Fpq(x) = t for each a < x < b, which is a contradiction. Hence, (rcp) holds. □

The following example describes linearly ordered families of pseudometrics that do not satisfy the (lcp) and (rcp) conditions, respectively.

Example 2.4.1.

- (1)

- ¬(lcp)

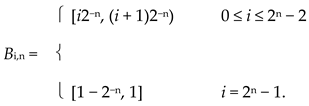

For each n ∈ N and 0 ≤ i < 2n, let

|

Each πn = {Bi,n | 0 ≤ i < 2n} is a partition of I and πn+1 < πn. Define the pseudometric dn on I by dn(p, q) = 0 if p, q ∈ Bi,n for some i and dn(p, q) = 1 otherwise. For each 0 < t < 1, let ρt = dk, where k = ⌊t/(1 − t)⌋ and let ak = k/(k + 1) for k ∈ N. Then ρt = dk if and only if ak ≤ t < ak+1. Suppose 0 < s < t < 1. If s ∈ [am, am+1) and t ∈ [an, an+1), where m < n, then ρs = dm and ρt = dn. Since πn < πm, ρs ≤ ρt, so Ω = {ρt} is a linearly ordered family. However, ρ1/2 = d1 is not the supremum of the family {ρt | 0 < t < 1/2} = {d0}, so (lcp) does not hold.

- (2)

- ¬(rcp)

For each distinct pair p, q ∈ I, define Fpq: R+⟶ I by

and let Fpp = H. Then (I, F) is a WPMS and for each 0 < t ≤ 1,

|

|

If p = 1/2 and q = 3/4, then Fpq = 1/2 on Fpq−1(0, 1), so by Prop 2.4.1(b), (rcp) does not hold. Alternately, ω1/4(1/4, 3/4) = 0, but ωs(1/4, 3/4) = 1 for each 1/4 < s < 1, so (rcp) does not hold.

The characterization stated in Prop 2.4.1(b) suggests yet another unexplored property. We say that a WPMS (S, F) satisfies the collective increasing property (cip) if for each 0 ≤ x < y, there exists p, q ∈ S such that Fpq(x) < Fpq(y). We can characterize this property by using the following set: given a WPMS (S, F), the spectrum of F is spec(F) = ∪{spec(ωt) | 0 < t < 1}, where ΩF = {ωt} and spec(ωt) = {ωt(p, q) | p, q ∈ S}.

The next result shows that the property (cip) is equivalent to a density criterion.

Prop 2.4.2.

A WPMS (S, F) satisfies (cip) if and only if spec(F) is a dense subset of R+.

Proof.

Suppose (S, F) satisfies (cip). Let 0 ≤ x < y and let x < a < b < y. By definition, there is p, q ∈ S such that Fpq(a) < Fpq(b). Choose Fpq(a) < t < Fpq(b). Then 0 < t < 1 and x < a ≤ ωt(p, q) < b, so spec(F) is dense in R+. Conversely, suppose spec(F) is dense in R+ and let 0 ≤ x < y. By assumption, there is 0 < t < 1 and p, q ∈ S such that x < ωt(p, q) < y. Then Fpq(x) < t ≤ Fpq(y), so (cip) holds. □

Because of the similar definitions, we can ask if (rcp) implies (cip). However, this is not the case. In Example 2.1.3, for distinct p and q, Fpq is strictly increasing on Fpq−1(0, 1) = (1, 1 + apq), so by Prop 2.4.1(b), (rcp) holds. However, since each ωt(p, q) = 1 + tapq, spec(F) ⊆ {0} ∪ [1, +∞), so by Prop 2.4.2, (cip) does not hold.

The next result shows that we can easily modify a linearly ordered family of pseudometrics so that (lcp) holds. We leave the proof to the reader.

Lemma 2.4.1.

Let Ω = {ρt | 0 < t < 1} be a linearly ordered family of distances (resp. pseudometrics) on a set S and for each 0 < t < 1, define

ρ′t = sup{ρs | 0 < s < t}. Then Ω′ = {ρt′} is a linearly ordered family of distances (resp. pseudometrics) on S that satisfies (lcp) and

ρt′ ≤

ρt for each t.

Other authors have shown that a WPMS can be reconstructed from its family of distances, but the following question does not seem to have been addressed. What conditions on a family of distances guarantee that it has the form ΩF for some WPMS (S, F)? Based on Prop 2.4.1(a), (lcp) is a necessary condition and as we noted earlier, ΩF is a linearly ordered family. The next result shows how to construct a special WPMS from a linearly ordered family of distances. A companion result for Menger spaces is presented in Section 3.2.

Theorem 2.4.1.

Let Ω = {ρt | 0 < t ≤ 1} be a linearly ordered family of distances on a set S that satisfies the following conditions:

- (a)

- ρ1 is a pseudometric and ρ1 = sup{ρt | 0 < t < 1}.

- (b)

- If p, q ∈ S and ρ1(p, q) > 0, then ρt(p, q) < ρ1(p, q) for each 0 < t < 1.

Then there is a special WPMS (S, F) such that ω1 = ρ1 and ωt ≤ ρt for each 0 < t < 1, where ΩF = {ωt}. If Ω also satisfies (lcp), then ωt = ρt for each 0 < t < 1.

Proof.

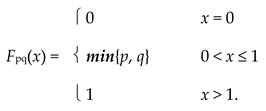

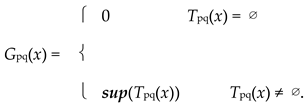

For p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+, let Tpq(x) = {0 < t < 1 | ρt(p, q) < x} and define Fpq: R+ ⟶ I by

|

- (1)

- Each Fpq belongs to Δ+ and Fpq−1(1) ≠ ∅.

[Since Tpq(0) = ∅, Fpq(0) = 0. If x > 0, then Tpp(x) = (0, 1), so Fpp(x) = 1. Therefore, Fpp = H. Suppose p, q ∈ S is a distinct pair and let g = Fpq. It is routine to show that g(0) = 0 and g is non-decreasing. Also, by definition, g(ρ1(p, q) + 1) = 1, so sup(g) = 1. Let x > 0 and let {xn} be a sequence in (0, x) such that xn ⟶ x. Let t = g(x). If t = 0, then g(xn) = 0 since g is non-decreasing, so limn ⟶+∞g(xn) = g(x). If t > 0, choose 0 < ε < t. Since t = sup{0 < s < 1 | ρs(p, q) < x}, there exists t − ε < s < 1 such that ρs(p, q) < x. Then ρt−ε(p, q) ≤ ρs(p, q) < xn for sufficiently large n, so g(xn) ≥ t − ε. Hence, limn ⟶+∞g(xn) = g(x). Therefore, g is left-continuous.]

- (2)

- (S, F) is a special WPMS.

[It is routine to show that (w1) and (w2) hold. Suppose Fpq(x) = Fqr(y) = 1 for distinct p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+. Then x > 0 and y > 0 and since Ω is linearly ordered, Tpq(x) = Tqr(y) = (0, 1). By (a), ρ1(p, q) = sup{ρt(p, q)} ≤ x and, similarly, ρ1(q, r) ≤ y, so ρ1(p, r) ≤ x + y. If ρ1(p, r) = 0, then each ρt(p, r) = 0, so Tpr(x + y) = (0, 1) since x + y > 0. If ρ1(p, r) > 0, then it follows from (b) that ρt(p, r) < ρ1(p, r) ≤ x + y for each 0 < t < 1, so Tpr(x + y) = (0, 1). Hence, in either case, Fpr(x + y) = 1, so (w3) holds. Then by (1), (S, F) is a special WPMS.]

Assume that ΩF = {ωt}. For the rest of the proof, we suppress the pair (p, q) and subscript pq.

- (3)

- For each 0 < t < 1, ωt ≤ ρt and ω1 = ρ1.

[Given ε > 0, choose x > ωt − ε such that F(x) < t. Then t ∉ T(x), so ρt ≥ x. Therefore, ωt ≤ ρt. If x > ω1, then F(x) = 1, so T(x) = (0, 1). Hence, ρt < x for each 0 < t < 1, so by (a), ρ1 ≤ x. This establishes ρ1 ≤ ω1. By (2) and Prop 2.4.1(a), ω1 = sup{ωt} ≤ sup{ρt} = ρ1, so ω1 = ρ1.]

- (4)

- If Ω satisfies (lcp), then ωt = ρt for each 0 < t < 1.

[If ωt < ρt for some 0 < t < 1, then since Ω satisfies (lcp), there is 0 < u < t such that ωt < ρu. Hence, t ≤ F(ρu), so F(ρu) = sup{0 < s < 1 | ρs < ρu} > 0. Since Ω is linearly ordered, if ρs < ρu, then s < u. Hence, F(ρu) ≤ u, which is a contradiction. Therefore, ωt = ρt.] □

Condition (b) in the previous result is only used to show that (S, F) satisfies (w3), so it may not be necessary. It was chosen because it seemed like the simplest condition to add to establish the result. Other assumptions can be made without altering the conclusion. For example, if ρ1 satisfies (a) and (b′): ρ1(p, r) < ρ1(p, q) + ρ1(q, r) for distinct p, q, r ∈ S, then in the proof of statement (2), ρ1(p, r) < ρ1(p, q) + ρ1(q, r) ≤ x + y, so ρ1(p, r) < x + y. Therefore, Fpr(x + y) = 1.

Theorem 2.4.1 is suggested by Prop 2.3.1 and by the work on metrically generated spaces and E-spaces ([1], Section 1.7 and Section 9.2, [12]). The latter topic involves using a probability space and a family of metrics as a base space without referring to a linear order.

The following example illustrates the construction used in Theorem 2.4.1.

Example 2.4.2.

For each 0 < t ≤ 1, define the distance ρt on (0, 1) by ρt(p, q) = | p − q |2/(t+1). Then Ω = {ρt | 0 < t ≤ 1} satisfies the conditions in Theorem 2.4.1 and (lcp) holds, so ωt = ρt for each 0 < t ≤ 1. Therefore, (S, F) is a special WPMS with the following distributions: for 0 < p < q < 1,

|

3. Menger Spaces

In this section, we discuss the families of Menger spaces and generalized Menger spaces.

3.1. Definitions and Examples

Various conditions can be imposed on a WPMS (S, F) that reflect the properties found in standard examples. One well-known condition has the following form: there is a mapping T: I × I ⟶ I such that the following condition holds:

(T) For each p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+, Fpr(x + y) ≥ T(Fpq(x), Fqr(y)).

The mapping T is called a norm and other requirements are usually imposed. For instance, T is a t-norm ([1], 5.6.1) if it is commutative, associative, and satisfies the following conditions: (i) for a ∈ I, T(a, 1) = a and (ii) for a, b, c, d ∈ I, a ≤ c and b ≤ d ⟹ T(a, b) ≤ T(c, d). The standard examples of t-norms are Min(a, b) = min{a, b}, Π(a, b) = ab, and Tm(a, b) = max{a + b − 1, 0} ([1], 11.1.1).

We say that a WPMS (S, F) is a Menger space under T ([1], 8.1.4) if T is a t-norm satisfying (T). If (S, F) is a Menger space under Min, then we simply refer to (S, F) as a Menger space. This is a non-standard use of the term that is appropriate for our purposes. We note that if T is a t-norm satisfying (T), then T ≤ Min, so each Menger space is a Menger space under T.

Based on Prop 2.2.2, a WPMS (S, F) is a Menger space if and only if ΩF consists of pseudometrics; the sufficiency is noted [1], 8.2.3). The WPMSs in Examples 2.1.1 and 2.1.2 are Menger spaces. In Example 2.1.5, some distances are not pseudometrics, so the WPMS is not a Menger space. Here is another example of a Menger space.

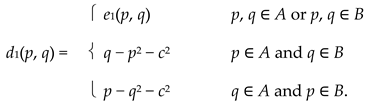

Example 3.1.1.

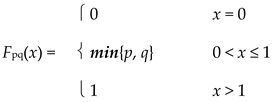

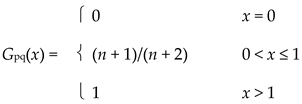

For distinct p, q ∈ I, define Fpq: R+⟶ I by

|

Then (S, F) is a Menger space and for each 0 < t ≤ 1,

|

3.2. Main Results

The first result is the promised companion to Theorem 2.4.1.

Theorem 3.2.1.

Let Ω = {ρt | 0 < t < 1} be a linearly ordered family of pseudometrics on a set S.

- (a)

- There is a Menger space (S, G) such that ωt ≤ ρt for each 0 < t < 1, where ΩG = {ωt}.

- (b)

- (S, G) is a special WPMS ⇔ sup{ρt(p, q) | 0 < t < 1} < +∞ for each p, q ∈ S. In this case, ρ1 is a pseudometric and ω1 ≤ ρ1 = sup{ρt}.

- (c)

- The family Ω satisfies (lcp) ⇔ ωt = ρt for 0 < t < 1. In this case, if (S, G) is special, then ω1 = ρ1.

Proof.

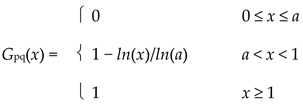

(a): For each p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+, let Tpq(x) = {0 < t < 1 | ρt(p, q) < x} and define Gpq: R+ ⟶ I by

|

- (1)

- Each Gpq belongs to Δ+.

[Since Gpq(ρt(p, q) + 1) ≥ t for each 0 < t < 1, sup(Gpq) = 1. Now the rest of the proof used to establish statement (1) in Theorem 2.4.1 shows that Gpq belongs to Δ+.]

- (2)

- (S, G) is a Menger space.

[It is routine to show that (w1) and (w2) hold. Suppose 0 < s = Gpq(x) ≤ t = Gqr(y) for p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+. Given 0 < ε < s, choose s − ε < s′ < s such that ρs′(p, q) < x and t − ε < t′ < t such that ρt′(q, r) < y. If s′ ≤ t′, then ρs′(p, r) ≤ ρs′(p, q) + ρt′(q, r) < x + y, so Gpr(x + y) ≥ s′ > s − ε. Similarly, if t′ ≤ s′, then Gpr(x + y) ≥ t′ > t − ε ≥ s − ε. Hence, Gpr(x + y) ≥ s = min{Gpq(x), Gqr(y)}, so by (1), (S, G) is a Menger space.]

- (3)

- For each 0 < t < 1, ωt ≤ ρt.

[The same argument used to prove (3) in Theorem 2.4.1 establishes the statement.]

It follows from (2) and Prop 2.2.2 that each member of ΩG = {ωt} is a pseudometric.

(b): Let p, q ∈ S. If (S, G) is special, then Gpq(x) = 1 for some x ∈ R+, so sup{ρt(p, q)} ≤ x. Conversely, if y = sup{ρt(p, q)} < +∞, then Gpq(y + 1) = 1, so (S, G) is special. In addition, if sup{ρt(p, q)} < +∞, then by Prop 2.4.1(a), ρ1 = sup{ρt} is a pseudometric on S.

If Gpq(x) < 1 for p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+, then ρ1(p, q) ≥ ρt(p, q) ≥ x for each Gpq(x) < t < 1, so ω1 ≤ ρ1.

(c): If ωt = ρt for each 0 < t < 1, then by (2) and Prop 2.4.1(a), Ω satisfies (lcp). Conversely, suppose Ω satisfies (lcp). If ωt(p, q) < ρt(p, q) for some 0 < t < 1 and p, q ∈ S, choose u < t that satisfies ωt(p, q) < x = ρu(p, q). Then t ≤ Gpq(x). Since Ω is linearly ordered, if ρs(p, q) < x, then s < u, so Gpq(x) ≤ u. This is a contradiction, so ωt = ρt for each 0 < t < 1.

If (S, G) is special, then by Prop 2.4.1(a) and part (b), ω1 = sup{ωt} = sup{ρt} = ρ1. □

Based on a summary of [13], a result similar to Theorem 3.2.1(b) seems to be established, but I cannot give an exact statement since I have not seen the paper. The following examples illustrate the construction used in the previous result.

Example 3.2.1.

In Example 2.4.1(1), for distinct p, q ∈ I, the distribution function in the corresponding Menger space is

|

Example 3.2.2.

For each 0 < t < 1, define the distance ρt on I by ρt(p, q) = | p − q |1−t. Then Ω = {ρt} is a linearly ordered family of pseudometrics satisfying (lcp). If 0 < a = | p − q | < 1, then

|

|

The WPMS (I, G) is the Menger space referred to in Theorem 3.2.1 that satisfies Ω = ΩG.

In Theorem 2.3.1, we presented a representation result for WPMSs with finite range. Here, we show that the Menger spaces satisfying this condition can be used to approximate any Menger space. We begin with the following preliminary result.

Lemma 3.2.1.

Let (S, F) be a WPMS and V = {v0, …, vn}, where v0 = 0 < v1 < … < vn = 1. For each p, q ∈ S, define FVpq: R+ ⟶ I by FVpq(x) = min{v ∈ V | Fpq(x) ≤ v}. Then the following statements hold:

- (a)

- For p, q ∈ S, FVpq ∈ Δ+ and FVpq−1(1) ≠ ∅.

- (b)

- (S, FV) satisfies (w1) and (w2).

- (c)

- For p, q ∈ S, Fpq ≤ FVpq and || FVpq − Fpq ||∞ ≤ max{vk+1 − vk | 0 ≤ k < n}.

- (d)

- For 0 < t ≤ 1, define ωVt: S × S ⟶ R+ by

ωVt(p, q) = sup{x ∈ R+ | FVpq(x) < t}.

Then ωVt is a distance and ωV1 is a pseudometric.

Proof.

Let p, q ∈ S and let G = FVpq. For x ∈ R+, let A(p, q, x) = {v ∈ V | Fpq(x) ≤ v}.

(a): Since 1 ∈ V, G is well-defined. Since Fpq(0) = 0, G(0) = 0. Since sup(Fpq) = 1, there is x such that Fpq(x) > vn−1, so G(x) = 1. Since Fpq is non-decreasing, if x ≤ y, then A(p, q, y) ⊆ A(p, q, x), so G(x) ≤ G(y). Let x > 0 and suppose G(x) = vk. If k = 0, then G(x) = 0, so G(p) = 0 for 0 < p < x. Hence, G is left-continuous at x. If k > 0, then vk−1 < Fpq(x) ≤ vk. Since Fpq is left-continuous, there exists 0 < h < x such that vk−1 < Fpq(x − h). Therefore, G(p) = vk for each x − h < p < x, so G is left-continuous at x. This shows that G ∈ Δ+.

(b): If p = q and x > 0, then by (w1) for (S, F), G(x) = min(A(p, p, x)) = min{v ∈ V | H(x) ≤ v} = 1. Hence, since G(0) = 0, G = H, so (w1) holds. Since (S, F) satisfies (w2), for p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+, A(p, q, x) = A(q, p, x), so FVpq = FVqp. Hence, (w2) holds.

(c): If G(x) = vk, then Fpq(x) ≤ vk, so Fpq ≤ G. If k = 0, then G(x) = 0 = Fpq(x). Otherwise, k > 0, so vk−1 < Fpq(x) and G(x) − Fpq(x) < vk − vk−1. Hence, || FVpq − Fpq ||∞ ≤ max{vk+1 − vk}.

(d): It follows from part (b) that each ωVt is a distance. Also, by part (a), ωV1 is well-defined, so by Lemma 2.2.2, it is a pseudometric. □

We say that a WPMS (S, F) can be approximated by a family W of WPMSs if for each ε > 0, there exists (S, G) ∈ W such || Fpq − Gpq ||∞ < ε for each p, q ∈ S. Now we can establish the following result.

Theorem 3.2.2.

Each Menger space can be approximated by the family of special Menger spaces with a finite range.

Proof.

Let (S, F) be a Menger space and suppose V = {v0, …, vn} with v0 = 0 < v1 < … < vn = 1.

- (1)

- (S, FV) is a special Menger space with a finite range.

[Let p, q, r ∈ S, x, y ∈ R+, G = FVpq, and H = FVqr. Suppose G(x) = vk and H(y) = vm with k ≤ m. If k = 0, then min{G(x), H(y)} = 0. If k > 0, then G(x) > vk−1 and H(y) > vm−1, so Fpq(x + y) > vk−1. Hence, FVpq(x + y) ≥ vk = min{G(x), H(y)}. A similar argument works if m < k. Therefore, (S, FV) satisfies condition (T) for T = Min, so by Lemma 3.2.1(a)(b), it is a special Menger space.

Given ε > 0, let V = {k/n | 0 ≤ k ≤ n}, where n ∈ N+ satisfies 1/n < ε. Therefore, for each p, q ∈ S, || FVpq − Fpq ||∞ ≤ 1/n by Lemma 3.2.1(c). □

To establish Theorem 3.2.2, (S, F) must be a Menger space. Otherwise, there exists p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+ such that a = Fpr(x + y) < b = Fpq(x) ≤ Fqr(y). Let V = {0, (a + b)/2, 1}. Then FVpq(x) = FVqr(y) = 1, but FVpr(x + y) ≤ (a + b)/2, so (S, FV) does not satisfy (w3).

3.3. Geometric Conditions

The Menger spaces are characterized among WPMSs by the fact that each associated distance is a pseudometric. This is the gold standard. However, before the definition of a metric space was codified, other properties of distances were studied [14,15,16,17]. In particular one largely forgotten property of a distance-space (S, d) is the following weak triangle condition:

(wtc) ≡ ∀ε > 0 ∃δ > 0 ∀x, y, z ∈ M · d(x, z) < δ and d(z, y) < δ ⟹ d(x, y) < ε.

Clearly, each pseudometric satisfies (wtc), but in Example 2.1.5, some distances do not satisfy it. Also, in Example 4.2.1(1), (R, F) is a WPMS+ and for each 0 < t ≤ 1,

|

Given 0 < t < 1, let p = 0, q = 1 − t, and r = 2(1 − t). Then ωt(p, q) = ωt(q, r) = 0, but ωt(p, r) = 1. Therefore, no member of ΩF satisfies (wtc). On the other hand, in Example 2.4.2, the (wtc) property holds for each distance.

The importance of the (wtc) property is demonstrated by Theorem A.3.1: if a distance-space (S, d) satisfies (wtc), then d is uniformly equivalent to a pseudometric on S. More generally, other special properties of distances may be useful for the classification of WPMSs. For purposes of comparison, we have included a second (wpc) property in Appendix A.3.

3.4. Generalized Menger Spaces

Now we present the third new idea in the paper. Much study has been devoted to the study of Menger spaces, but it seems that a natural generalization has not received much attention. Consider a WPMS that satisfies the following weaker version of (T), where T = Min:

(M′) ∀ε > 0 ∃δ > 0 ∀p, q, r ∈ S · Fpr(ε) ≥ min{Fpq(δ), Fqr(δ)}.

In this case, we say that (S, F) is a generalized Menger space. If (S, F) is a Menger space, then (M′) holds since Fpr(ε) ≥ min{Fpq(ε/2), Fqr(ε/2)} for each ε > 0.

The next result gives several characterizations of generalized Menger spaces.

Theorem 3.4.1.

The following conditions are equivalent for a WPMS (S, F).

- (a)

- (M′) holds.

- (b)

- There is a right-continuous modulus of continuity φ such that for p, q, r ∈ S and 0 < t < 1,

ωt(p, r) < φ(max{ωt(p, q), ωt(q, r)}).

- (c)

- There is a right-continuous modulus of continuity φ such that Fpr ° φ ≥ min{Fpq, Fqr} for p, q, r ∈ S.

- (d)

- ΩF satisfies (equi-wtc): for each ε > 0, there exists δ > 0 such that for each 0 < t < 1 and p, q, r ∈ S, ωt(p, r) < δ and ωt(q, r) < δ ⟹ ωt(p, q) < ε.

Proof.

(a) ⟹ (b): In the definition of (M′), δ depends only on ε, so the proof of (a) ⟹ (b) in Theorem A.3.1 shows that there is a non-decreasing mapping τ: (0, +∞) ⟶ (0, +∞) that satisfies the following conditions:

(ec1) For each p, q, r ∈ S and 0 < t < 1, if ωt(p, q) < x and ωt(q, r) < x, then ωt(p, r) < τ(x).

(ec2) τ(0+) = 0.

Define the mapping φ: R+ ⟶ R+ by φ(x) = τ(x+). Since τ is non-decreasing, φ is non-decreasing and an elementary argument shows that φ is right-continuous. Hence, by (ec2), φ(0+) = φ(0) = 0, so φ is a modulus of continuity that satisfies (ec1). Let p, q, r ∈ S, 0 < t < 1, and assume that ωt(p, q) ≤ ωt(q, r). By (ec1), if ωt(q, r) < x, then ωt(p, r) < τ(x) ≤ φ(x). Hence, by the right-continuity of φ, ωt(p, r) ≤ φ(ωt(q, r)).

(b) ⟹ (c): Let x ∈ R+ and assume that s = Fpq(x) ≤ t = Fqr(x). Then ωs(q, r) ≤ ωt(q, r) ≤ x and ωs(p, q) ≤ x, so ωs(p, r) < φ(max{ωs(p, q), ωs(q, r)}) ≤ φ(x). Hence, Fpr(φ(x)) ≥ s.

(c) ⟹ (d): Since φ(0+) = φ(0) = 0, given ε > 0, there is δ > 0 such that φ(δ) < ε/2. Suppose ωt(p, q) < δ and ωt(q, r) < δ for some 0 < t < 1. Then Fpq(δ) ≥ t and Fqr(δ) ≥ t, so by (c), we obtain Fpr(ε/2) ≥ Fpr(φ(δ)) ≥ t. Hence, ωt(p, r) ≤ ε/2 < ε. Therefore, ΩF satisfies (equi-wtc).

(d) ⟹ (a): Let ε > 0 and choose δ > 0 such that the conclusion in (d) holds. Let p, q, r ∈ S and suppose α = Fpq(δ/2) ≤ β = Fqr(δ/2). If α = 0, then Fpr(ε) ≥ min{α, β}. If α = 1, then β = 1. Let 0 < t < 1. Then Fpq(δ/2) = Fqr(δ/2) > t, so ωt(q, r) < δ and ωt(q, r) < δ. Hence, ωt(p, r) < ε, so Fpr(ε) ≥ t. Since t is arbitrary, Fpr(ε) = 1, so Fpr(ε) ≥ min{α, β}. If 0 < α < 1, then ωα(p, q) < δ and ωα(q, r) < δ, so ωα(p, r) < ε. Hence, Fpr(ε) ≥ α = min{α, β}. This establishes (M′). □

In Example 2.1.5, ωt does not satisfy (wtc) for 0 < t ≤ 1/2, so by the previous result, the WPMS is not a generalized Menger space. The following example also shows that a generalized Menger space may not be a Menger space.

Example 3.4.1.

We reuse Example 2.4.2. For 0 < t ≤ 1, the distance ρt on (0, 1) is defined by ρt(p, q) = | p − q |2/(t+1) and (S, F) is a special WPMS.

We claim that Ω = {ρt} is an (equi-wtc) family. For 0 < ε < 1, let δ = ε/4 and let p, q, and r be distinct points in (0, 1). Let a = | p − q |, b = | q − r |, and c = | p − r |. For 0 < t < 1, let y = 2/(t + 1), and suppose ay < δ and by < δ. If c = a + b, then cy < (2δ1/y)y = 2yδ = 2y−2ε < ε. If c = a − b, then cy < ay < ε and, similarly, if c = b − a, then cy < by < ε. By Theorem 3.4.1, (S, F) satisfies (M′). Choose 0 < t < 1 and let p = 1/4, q = 1/2, r = 3/4, and y = 2/(t + 1). Then ρt(p, q) = ρt(q, r) = (1/4)y, so ρt(p, q) + ρt(q, r) = 2(1/4)y = 21−2y and ρt(p, r) = 2−y. Since y > 1, 2−y > 21−2y, so ρt is not a pseudometric. Hence, by Prop 2.2.2, (S, F) is not a Menger space.

The following result shows that each generalized Menger space has a closely associated Menger space.

Theorem 3.4.2.

If a WPMS (S, F) satisfies (M′), then there is a Menger space (S, G) and right-continuous moduli of continuity f and g such that the following statements hold for p, q ∈ S and 0 < t < 1, where ΩF = {ωt} and ΩG = {σt}:

- (a)

- σt(p, q) < δ < 1/8 ⟹ ωt(p, q) < f(δ).

- (b)

- ωt(p, q) < δ < 1 ⟹ σt(p, q) < g(δ).

In terms of distribution functions, for 0 < δ < 1/8, Gpq(δ) ≤ Fpq(f(δ)) and Fpq(δ) ≤ Gpq(g(δ)).

Proof.

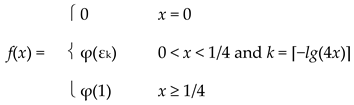

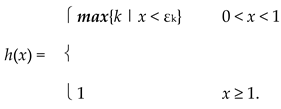

and define h: R+ ⟶ N+ by

The proof is essentially the same as the proof of (b) ⟹ (c) in Theorem A.3.1 except that we use the regular écart φ from Theorem 3.4.1. In statements (1) and (2), ω denotes one of the mappings ωt. Their proofs follow the proof of Theorem A.3.1. Recall from Appendix A.1 that if d is a distance on S, then S(d, r) = Sd(r) = {Sd(x, r) | x ∈ S} for each r > 0, where Sd(x, r) = {y ∈ S | d(x, y) < r}.

- (1)

- For each x ∈ M and r > 0, St(x, Sω(r)) ⊆ Sω(x, φ(r)).

- (2)

- There is a decreasing sequence {εk} ⊆ (0, 1] converging to 0 with ε0 = ε1 = 1 such that φ(εk+1) < εk and Sω(εk+1) <* Sω(εk) for each k > 0.

For each 0 < t < 1, let A0,t = {S} and Ak,t = S(ωt, εk) for k > 0. By (2), each {Ak,t} is a normal sequence. Define μt: S × S ⟶ R by μt(p, q) = inf{2−k | q ∈ St(p, Ak,t)} and let ρt be the corresponding path-metric based on Prop A.2.2(i). If 0 < s < t < 1, then Ak,t < Ak,s for each k since ωs ≤ ωt. Therefore, μs ≤ μt, so ρs ≤ ρt.

Define f: R+ ⟶ R+ by

|

|

Define g: R+ ⟶ R+ by g(0) = 0 and g(x) = x + 2−h(x) if x > 0. One can verify that f and g are right-continuous moduli of continuity.

- (3)

- (i)ρt(p, q) < δ < 1/4 ⟹ ωt(p, q) < f(δ).(ii) ωt(p, q) < δ < 1 ⟹ ρt(p, q) < g(δ).

[(i): By Prop A.2.2(ii), ρt ≤ μt ≤ 2ρt, so we obtain μt(p, q) < 2δ < 1. Let k = ⌈−lg(2δ)⌉. Then 2−k−1 ≤ 2δ < 2−k, so μt(p, q) ≤ 2−k. Since q ∈ St(p, Ak,t) = St(p, Sω(t)(εk)), it follows from (1) that ωt(p, q) < φ(εk) = f(δ).

(ii): Let k = h(δ). Since δ < εk, it follows that ωt(p, q) < εk, so we have q ∈ St(p, Ak,t). Therefore, ρt(p, q) ≤ μt(p, q) ≤ 2−k < g(δ).]

For each 0 < t < 1, let μ′t = sup{μs | 0 < s < t} and ρ′t = sup{ρs | 0 < s < t}. Then μ′t ≤ μt, ρ′t ≤ ρt, and by Lemma 2.4.1, {ρ′t} is a linearly ordered family of pseudometrics satisfying (lcp). Therefore, by Theorem 3.2.1(a)(c), there is a Menger space (S, G) with σt = ρ′t for each t, where ΩG = {σt}.

- (4)

- For each 0 < t < 1, μt ≤ 2μ′t and ρt ≤ 2ρ′t.

[Assume that μ′t(p, q) = 2−k and choose 0 < s′ < t such that μs′(p, q) > 2−k−1. Let s′ < s < t. Then μs(p, q) = 2−k, so q ∈ St(p, Ak,s). Hence, by (1), ωs(p, q) ≤ φ(εk). By Prop 2.4.1(a), the family {ωt} satisfies (lcp), so by (2), ωt(p, q) ≤ φ(εk) < εk−1. Therefore, μt(p, q) ≤ 21−k = 2μ′t(p, q). This establishes the first statement. The second statement follows from the first one and the definition of a path-metric.]

- (5)

- (i)σt(p, q) < δ < 1/8 ⟹ ωt(p, q) < f(δ)(ii) ωt(p, q) < δ < 1 ⟹ σt(p, q) < g(δ).

[(i): By (4), ρt(p, q) ≤ 2σt(p, q) < 2δ < 1/4, so by (3)(i), ωt(p, q) < f(δ).

(ii): By (3)(ii), σt(p, q) ≤ ρt(p, q) < g(δ).]

To verify the final statement, assume that Gpq(δ) > Fpq(f(δ)) and choose Gpq(δ) > t > Fpq(f(δ)). Then σt(p, q) < δ, so by (5)(i), ωt(p, q) < f(δ). Hence, Fpq(f(δ)) ≥ t, which is a contradiction. Therefore, Gpq(δ) ≤ Fpq(f(δ)). The other statement is established similarly.] □

4. Operations on WPMSs

4.1. The Category WP

In this section, we introduce the fourth new idea in the paper—a categorical framework for WPMSs and accompanying operations. The idea has been touched on in [4,18], where a generalized notion of probabilistic metric spaces is introduced in the context of quantales.

The reader is referred to [19] for general categorical notions. Let | WP | denote the family of WPMSs. For (S, F) and (T, G) in | WP |, a morphism [f]: (S, F) ⟶ (T, G) is a mapping f: S ⟶ T such that Fpq ≦ Gf(p)f(q) for each p, q ∈ S, where ≦ denotes the point-wise order on Δ+. The symbol WP((S, F), (T, G)) denotes the family of morphisms from (S, F) to (T, G). The composition of morphisms [f]: (S, F) ⟶ (T, G) and [g]: (T, G) ⟶ (V, K) is the morphism [g ° f]: (S, F) ⟶ (V, K). Also, [idS] is the identity morphism for each WPMS (S, F), so WP is a category.

The first result characterizes the morphisms in WP in terms of the families of distances.

Lemma 4.1.1.

The following statements are equivalent for WPMSs (S, F) and (T, G) and a mapping f: S ⟶ T, where ΩF = {ωt} and ΩG = {ρt}.

- (a)

- [f]: (S, F) ⟶ (T, G) is a WP-morphism.

- (b)

- For each 0 < t < 1, f: (S, ωt) ⟶ (T, ρt) is a non-expansive mapping.

Proof.

¬(b) ⟹ ¬(a): Choose t, p, and q such that ωt(p, q) < ρt(f(p), f(q)). Let ωt(p, q) < x < ρt(f(p), f(q)). Therefore, Gf(p)f(q)(x) < t ≤ Fpq(x), so ¬(a) holds.

¬(a) ⟹ ¬(b): Choose p, q, and x such that Gf(p)f(q)(x) < Fpq(x) and let Gf(p)f(q)(x) < t < Fpq(x). Then ωt(p, q) < x ≤ ρt(f(p), f(q)). Hence, ωt(p, q) < ρt(f(p), f(q)), so ¬(b) holds. □

Corollary 4.1.1.

The following statements are equivalent for WPMSs (S, F) and (T, G) and a mapping h: S ⟶ T, where ΩF = {ωt} and ΩG = {ρt}.

- (a)

- [h]: (S, F) ⟶ (T, G) is a WP-isomorphism.

- (b)

- h is a bijection and Fpq = Gh(p)h(q) for each p, q ∈ S.

- (c)

- For each 0 < t < 1, h: (S, ωt) ⟶ (T, ρt) is a surjective isometry.

Proof.

The equivalence of (a) and (b) follows from the definition of a WP-isomorphism. The equivalence of (a) and (c) follows from Lemma 4.1.1. □

We note that the notion of isomorphic WPMS’s is the same as the idea of isometric WPMS’s found in ([1], 8.1.2).

The next result lists some elementary facts about the category WP. The proof is left to the reader.

Lemma 4.1.2.

The following statements hold for WPMSs (S, F) and (T, G).

- (a)

- The monomorphisms (resp. epimorphisms) in WP are exactly the morphisms that are injections (resp. surjections) on the base sets.

- (b)

- For each t ∈ T, constt: S ⟶ T defines a WP-morphism [constt]: (S, F) ⟶ (T, G).

- (c)

- Let H ⊆ S and FH = F|H×H. Then (H, FH) is a WPMS and inclH: H ⟶ S defines a WP-morphism [inclH]: (H, FH) ⟶ (S, F).

In the literature, both countable products and arbitrary products of WPMSs have been studied. In our setting, we can characterize when products exist.

For a set W = {(Si, Fi) | i ∈ I} ⊆ | WP |, let S = ΠSi and define the mapping F: S × S ⟶ F(R+, I) by F(p, q) = inf{Fi(pi, qi) | i ∈ I}. Then the following statements hold:

- (1)

- For each p, q ∈ S, Fpq(0) = 0, Rng(Fpq) ⊆ I, and Fpq is non-decreasing. (This follows since each Fi(pi, qi) ∈ Δ+.)

- (2)

- (S, F) satisfies (w1)–(w3). (Clearly, (w1) and (w2) hold. If Fpq(x) = Fqr(y) = 1 for some p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+, then each Fi(pi, qi)(x) = Fi(qi, ri)(y) = 1, so Fi(pi, ri)(x + y) = 1. Hence, Fpq(x + y) = 1, so (w3) holds.)

- (3)

- For each 0 < t < 1, ωt = sup{ωi,t}, where ΩF = {ωt} and each ΩF(i) = {ωi,t}.

It may not be the case that sup(Fpq) = 1 for each p, q ∈ S (Example 4.1.1), so Fpq may not belong to Δ+. To remedy this problem, we introduce the following property.

We say that W satisfies the uniform limit property (ulp) if for each ε > 0 and each {pi, qi} ⊆ Si, i ∈ I, there is x ∈ R+ such that inf{Fi(pi, qi)(x) | i ∈ I} > 1 − ε. Clearly, (ulp) holds if W is a finite family. Also, if W satisfies (ulp), then each Fpq ∈ Δ+, so by (1) and (2), (S, F) is a WPMS.

Prop 4.1.1.

The following statements hold for a set W = {(Si, Fi) | i ∈ I} ⊆ | WP |.

- (a)

- If W satisfies (ulp), then (S, F) is the product in WP of the members of W. Hence, each finite family of WPMSs has a product in WP.

- (b)

- If W satisfies (ulp) and W consists of Menger spaces, then (S, F) is a Menger space.

- (c)

- If W is an infinite set and its product in WP exists, then W satisfies (ulp).

Proof.

(a): Based on our earlier discussion, (S, F) is a WPMS, where S = ΠSi and F: S × S ⟶ Δ+ is defined by F(p, q) = inf{Fi(pi, qi) | i ∈ I}. For each i ∈ I, let πi: S ⟶ Si be the standard projection mapping. Since F ≤ Fi, [πi]: (S, F) ⟶ (Si, Fi) is a morphism. Let (T, G) be a WPMS and assume that each [fi]: (T, G) ⟶ (Si, Fi) is a morphism. Let f: T ⟶ S be the mapping that satisfies πi ° f = fi for each i. Then G(a, b) ≤ Fi(fi(a), fi(b)) for each a, b ∈ T and i, so G(a, b) ≤ F(f(a), f(b)). Therefore, [f]: (T, G) ⟶ (S, F) is a morphism. If a morphism [g]: (T, G) ⟶ (S, F) satisfies πi ° g = fi for each i, then clearly, f = g. Hence, (S, F) is the product.

(b): We refer to (2) above. Suppose F(p, r)(x + y) < b = F(p, q)(x) ≤ c = F(q, r)(y) for p, q, r ∈ S and x, y ∈ R+. Choose i ∈ I with Fi(pi, ri)(x + y) < b. Since b ≤ Fi(pi, qi)(x) and c ≤ Fi(qi, ri)(y), Fi(pi, ri)(x + y) < min{Fi(pi, qi)(x), Fi(qi, ri)(y)}. This is a contradiction, so (S, F) is a Menger space.

(c): Assume that (T, G) is the product of the family W based on the projection mappings {[σi]: (T, G) ⟶ (Si, Fi)}. If W does not satisfy (ulp), then there is 0 < ε < 1 and {pi, qi} ⊆ Si, i ∈ I, such that inf{Fi(pi, qi)(x) | i ∈ I} ≤ δ = 1 − ε for each x ∈ R+.

Let ({∗}, H) be the trivial WPMS and for each i, define the morphism [fi]: ({∗}, H) ⟶ (Si, Fi) by fi(∗) = pi. By assumption, there is a morphism [f]: ({∗}, H) ⟶ (T, G) such that σi ° f = fi for each i.

Similarly, for each i, define the morphism [gi]: ({∗}, H) ⟶ (Si, Fi) by gi(∗) = qi. Then there is a morphism [g]: ({∗}, H) ⟶ (T, G) such that σi ° g = gi for each i. Let s = f(∗) and t = g(∗). Then for each i ∈ I and x ∈ R+, Gst(x) ≤ Fi(fi(∗), gi(∗))(x) = Fi(pi, qi)(x), so sup(Gst) ≤ inf{Fi(pi, qi)(x)} ≤ δ, which contradicts the fact that Gst ∈ Δ+. Therefore, W satisfies (ulp). □

Many authors have studied products of WPMSs independently of any categorical framework. For example, ([20], Theorem 1) establishes the finite case of Prop 4.1.1(a) and ([21], Proposition 3) “purports” to establish a general product theorem. Here are some additional details about finite products based on the previous construction:

- If (S, F) is the product of a finite family {(Si, F(i))} of WPMS’s, then ωt = max{ωi,t} for each t, where ΩF = {ωt} and ΩF(i) = {ωi,t} for each i.

- The product of a finite family of Menger spaces is a Menger space. (By Prop 2.2.2, each coordinate distance is a pseudometric, so by the previous remark, each distance in the product is a pseudometric. Hence, by Prop 2.2.2, the product is a Menger space.)

- The product (S, F) of a finite family {(Si, Fi)} of special WPMS’s is a special WPMS. (For each p, q ∈ S and i, choose xi such that Fi(pi, qi)(xi) = 1. Then F(p, q)(max{xi}) = 1.)

The following example shows that the (ulp) property does not hold in general.

Example 4.1.1.

For each n ∈ N+, define Fn: [0, n] × [0, n] ⟶ Δ+ by Fn(p, q)(x) = H(x − | p − q |).

Each ([0, n], Fn) ∈ | WPM |, but W = {([0, n], Fn) | n ∈ N+} does not satisfy (ulp). To see this, note that for each x ∈ R+, inf{Fn(0, n)(x)} = inf{H(x − n)} = 0.

By way of contrast with Prop 4.1.1, we have the following rather dramatic result.

Prop 4.1.2.

No pair of WPMSs has a coproduct in WP.

Proof.

which is a contradiction. Hence, the coproduct does not exist. □

Let (S, F) and (T, G) be WPMSs and assume that (C, H) is their coproduct in WP based on the morphisms [i]: (S, F) ⟶ (C, H) and [j]: (T, G) ⟶ (C, H). Suppose ΩH = {ρt}. Choose p ∈ S and q ∈ T and let a = i(p) and b = j(q). Let r = ρ1/2(a, b) + 1. Let D = {0, r} and let Kr0 = K0r: R+ ⟶ I be the characteristic function of (r, +∞). Also, let K00 = Krr = H. Then (D, K) is a WPMS and ΩK = {ωt}, where each ωt satisfies ωt(0, r) = r. By Lemma 4.1.2(b), each constant mapping defines a morphism, so there exists a morphism [h]: (C, H) ⟶ (D, K) such that h ° i = const0 and h ° j = constr. By Lemma 4.1.1, h: (C, ρ1/2) ⟶ (D, ω1/2) is non-expansive, so

ω1/2(h(a), h(b)) = ω1/2(0, r) = r ≤ ρ1/2(a, b) = r − 1,

A result related to Prop 4.1.2 is found in ([22], Proposition 1) stating that the category Met (Section 4.2) has no coproducts. Next, we consider limits in WP.

Prop 4.1.3.

Suppose W = {(Si, Fi) | i ∈ D} ⊆ | WP |, where (D, ≤) is a directed set, and ({(Si, Fi) | i ∈ I}, {[fij]: (Sj, Fj) ⟶ (Si, Fi) | i, j ∈ D and i ≤ j}) is an inverse system in WP. If W satisfies (ulp), then the inverse system has an inverse limit in WP.

Proof.

Let P = ΠSi and define F: P × P ⟶ Δ+ by F(p, q) = inf{Fi(pi, qi) | i ∈ I}. By Prop 4.1.1(a), (P, F) is the product of {(Si, Fi)}. Let S = {s ∈ P | i, j ∈ D and i ≤ j ⟹ fij(sj) = si}. By Lemma 4.1.2(c), (S, FS) is also a WPMS. We claim that ((S, FS), {[πi]: (S, FS) ⟶ (Si, Fi) | i ∈ D}) is the inverse limit, where each πi is a projection mapping. If ((T, G), {[φi]: (T, G) ⟶ (Si, Fi) | i ∈ I}) is a source (fij ° φj = φi for i, j ∈ D satisfying i ≤ j), then φ: T ⟶ S defined by φ(t) = (φi(t)) is well-defined and πi ° φ = φi for each i. By assumption, for u, v ∈ T and i ∈ D, Guv ≤ Fi(φi(u), φi(v)), so Guv ≤ FS(φ(u), φ(v)). Therefore, [φ]: (T, G) ⟶ (S, FS) is a WP-morphism. □

Prop 4.1.4.

Each directed system in WP has a direct limit.

Proof.

Let ({(Si, Fi) | i ∈ I}, {fij: (Si, Fi) ⟶ (Sj, Fj) | i, j ∈ I and i ≤ j}) be a directed system in WP, where (I, ≤) is a directed set. For each i, j ∈ I, let I(i, j) = {k ∈ I | i ≤ k and j ≤ k}. For each i ∈ I, let S^i = Si × {i}, and let S^ = ∪{S^i | i ∈ I}. For each (p, i) ∈ S^i and (q, j) ∈ S^j, define (p, i) ~ (q, j) if there is k ∈ I(i, j) such that fik(p) = fjk(q). Then ~ is an equivalence relation on S^.

Let

denote the set of equivalence classes for ~. Let a = [(p, i)], b = [(q, j)] ∈ S. If a = b, let Fab = H. If a ≠ b, let

S = {[(p, i)]: i ∈ I and p ∈ Si}

Fab = sup{Fk(fik(p), fjk(q)) | k ∈ I(i, j)}.

It is easy to show (S, F) is a WPMS. For each i ∈ I, define ψi: Si ⟶ S by ψi(p) = [(p, i)].

- (1)

- Each [ψi]: (Si, Fi) ⟶ (S, F) is a morphism and {[ψi]} is a sink for the directed system.

[Let a = [(p, i)], b = [(q, i)] ∈ S, and x ∈ R+. If a = b, then Fi(p, q)(x) ≤ 1 = H(x) = Fab(x). If a ≠ b, then Fi(p, q) ≤ sup{Fk(fik(p), fik(q)) | i ≤ k} = Fab(x). If i, j ∈ I and i ≤ j, then fij(p) = fjj(fij(p)) for each p ∈ Si, so (p, i) ~ (fij(p), j). Hence, for each p ∈ Si, ψj(fij(p)) = [(fij(p), j)] = [(p, i)] = ψi(p). Therefore, ψj ° fij = ψi for each i, j ∈ I.]

- (2)

- ((S, F), {[ψi]: (Si, Fi) ⟶ (S, F) | i ∈ I}) is the direct limit of the directed system.

[Let ((T, G), {[φi]: (Si, Fi) ⟶ (T, G) | i ∈ I}) be a sink for the directed system and define the mapping h: S ⟶ T by h([(p, i)]) = φi(p). If (p, i) ~ (q, j), then there exists k ∈ I(i, j) such that fik(p) = fjk(q), so φi(p) = φk(fik(p)) = φk(fjk(q)) = φj(q). Therefore, h is well-defined and h ° ψi = φi for each i ∈ I.

We claim that [h]: (S, F) ⟶ (T, G) is a morphism. Let a = [(p, i)], b = [(q, j)] ∈ S. If a = b, then Fab = H = Gh(a)h(b). Suppose a ≠ b. If k ∈ I(i, j), then since [φk] is a morphism,

Fk(fik(p), fjk(q)) ≤ G(φk(fik(p)), φk(fjk(q))) = G(φi(p), φj(q)) = G(h(a), h(b)).

Therefore, Fab ≤ G(h(a), h(b)).] □

Here are two useful examples that illustrate the previous results.

Example 4.1.2.

Each WPMS is the direct limit of the family of finite subspace WPMSs.

Let (S, F) be a WPMS and assume that I ⊆ PF+(S) satisfies S = ∪I and (I, ≤) is a directed set, where ≤ is defined by A ≤ B if A ⊆ B. Let W = {(A, FA) | A ∈ I} be the family of subspace WPMSs (Lemma 4.1.2(c)) and let F = {[fAB]: (A, FA) ⟶ (B, FB) | A, B ∈ I and A ≤ B}, where each fAB is the inclusion mapping. Since {W, F} is a directed system, by Prop 4.1.4, {(T, G), {[ψA]: A ∈ I} is the direct limit, where T = {[(a, A)]: A ∈ I and a ∈ A} is the set of equivalence classes of ~ and each ψA: S ⟶ T is defined by ψA(a) = [(a, A)]. Since (a, A) ~ (b, B) if there exists C ∈ I(A, B) such that fAC(a) = fBC(b), we have [(a, A)] = {(a, B): a ∈ B ∈ I}.

By Lemma 4.1.2(c), {(S, F), {[inclA]: (S, FA) ⟶ (S, F) | A ∈ I} is a sink for the directed system, so there exists a morphism [h]: (T, G) ⟶ (S, F) such that h ° ψA = inclA for each A ∈ I. It is easy to verify that h is a bijection since S = ∪I. Also, Gtt′ = Fh(a)h(b) for each t = [(a, A)] and t′ = [(b, B)], so by Corollary 4.1.1, [h] is an isomorphism. Therefore, (S, F) is the direct limit.

Example 4.1.3.

Each Menger space (S, F) is the inverse limit of special Menger spaces with a finite range.

Let V = {V ∈ PF+([0, 1]) | {0, 1} ⊆ V} and for V, W ∈ V, define V ≤ W if V ⊆ W. Then (V, ≤) is a down-directed set. Statement (1) in Theorem 3.2.2 shows that for each V ∈ V, (S, FV) is a Menger space with a finite range. Also, by Lemma 3.2.1(c), each πV = [idS]: (S, F) ⟶ (S, FV) is a morphism, so W = {(S, FV) | V ∈ V} satisfies (ulp). If V, W ∈ V and V ≤ W, then FWpq(x) ≤ FVpq(x) for each p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+. Therefore, each fVW = [idS]: (S, FW) ⟶ (S, FV) is a morphism, so (W, {fVW | V, W ∈ V and V ≤ W}) is an inverse system in WP. Based on the construction in Prop 4.1.3, the inverse limit is (Δ, G), where Δ = {δ ∈ SV | V, W ∈ V and V ≤ W ⟹ fVW(δW) = δV} and G(δ, ξ) = inf{FV(δV, ξV) | V ∈ V} for δ, ξ ∈ Δ. Let δ ∈ Δ and let A, B ∈ V. Let V = A ∩ B. Then V ∈ V and δA = fVA(δA) = δV = fVB(δB) = δB, so Δ is the diagonal in SV, that is,

Δ = {δ ∈ SV | δV = δW for each V, W ∈ V}.

Since {(S, F), {πV | V ∈ V}) is a source for the inverse system, the bijection φ: S ⟶ Δ defined by φ(s)V = s for each V ∈ V defines a morphism [φ]: (S, F) ⟶ (Δ, G). Let p, q ∈ S and x ∈ R+. Then y = Fpq(x) ≤ z = Gφ(p)φ(q)(x) = inf{FVpq(x) | V ∈ V}. Choose A ∈ V that contains y. Then z ≤ FApq(x) = y, so Fpq = Gφ(p)φ(q). Hence, by Corollary 4.1.1, [φ] is an isomorphism.

Note that the same conclusion holds by using V = {{0, 1}} ∪ {{0, r, 1}: 0 < r < 1}.

4.2. Subcategories of WP

In this section, we introduce and compare several special subcategories of WP. Here are the categories that we will be using:

Dist—objects are distance-spaces and morphisms are non-expansive mappings.

PMet (resp. Met)—objects are pseudometric (resp. metric) spaces and morphisms are non-expansive mappings.

WPD—full subcategory of WP based on WPMSs determined by pseudometric spaces.

WPM—full subcategory of WP based on Menger spaces.

WPS—full subcategory of WP based on special WPMSs.

The following result describes some relationships between the various categories.

Theorem 4.2.1.

- (a)

- PMet is a reflective subcategory of Dist.

- (b)

- PMet and WPD are isomorphic categories.

- (c)

- WPD is a coreflective subcategory of WPS and the coreflection of a special WPMS (S, F) is the WPMS determined by the pseudometric space (S, ω1).

- (d)

- WPM is a reflective subcategory of WP.

Proof.

(a): Let (M, ω) be a distance-space. By Prop A.2.1, there is a largest pseudometric dω such that dω ≤ ω, so r = idM: (M, ω) ⟶ (M, dω) is a non-expansive mapping. Let f: (M, ω) ⟶ (N, σ) be a non-expansive mapping to a pseudometric space and define τ by τ(x, y) = σ(f(x), f(y)). Since σ is a pseudometric, τ is a pseudometric on M satisfying τ ≤ ω, so τ ≤ dω. Hence, f: (M, dω) ⟶ (N, σ) is a morphism and f ° r = f. Clearly, f is the unique mapping with this property.

(b): For each (S, γ) ∈ | PMet |, let E((S, γ)) = (S, Gγ) (Example 2.1.1) and for each non-expansive mapping g: (S, γ) ⟶ (S′, γ′), where (S′, γ′) ∈ | PMet |, let E(g) = g. By definition, for p, q ∈ S, Gpq(x) = H(x − γ(p, q)). Hence, if Gpq(x) = 1, then x > γ(p, q)) ≥ γ′(g(p), g(q)), so we obtain G′g(p)g(q)(x) = H(x − γ′(g(p), g(q))) = 1. Therefore, Gpq ≤ G′g(p)g(q), so E(g) is a morphism. This defines a functor E: PMet ⟶ WPD.

For each (S, Gγ) ∈ | WPD |, let F((S, Gγ)) = (S, γ) and for each morphism [h]: (S, Gγ) ⟶ (S′, Gγ′), where (S′, γ′) ∈ | WPD |, let F(h) = h. Given p, q ∈ S and ε > 0, choose γ(p, q) < x < γ(p, q) + ε. Then Gpq(x) = 1, so G′h(p)h(q)(x) = 1 since [h] is a morphism. Therefore, x > γ′(h(p), h(q)). Hence, γ(p, q) + ε > γ′(h(p), h(q)) for each ε > 0, so h: (S, γ) ⟶ (S′, γ′) is a non-expansive mapping. This defines a functor F: WPD ⟶ PMet. Based on the definitions, E °F (resp. F ° E) is the identity functor on WPD (resp. PMet), so E is an isomorphism.

(c): If (S, F) is a special WPMS, then by Lemma 2.2.2, γ = ω1 is a pseudometric. Let (S, Gγ) be the WPMS determined by (S, γ) which belongs to | WPD |.

- (1)

- [idS]: (S, Gγ) ⟶ (S, F) is a morphism.

[Let p, q ∈ S. Since Gpq(x) = H(x − ω1(p, q)), if x ≤ ω1(p, q), then Gpq(x) = 0 ≤ Fpq(x). On the other hand, if x > ω1(p, q), then Fpq(x) = 1, so Gpq(x) ≤ Fpq(x).]

- (2)

- (S, Gγ) is the coreflection of (S, F) in WPD.

[Suppose [g]: (M, Gγ′ = {G′ab})) ⟶ (S, F) is a WP-morphism where the domain WPMS is determined by the pseudometric space (M, γ′). Let a, b ∈ M. Then G′ab ≤ Fpq, where p = g(a) and q = g(b). If γ′(a, b) < γ(p, q), choose γ′(a, b) < x < γ(p, q). Since x < γ(p, q) = ω1(p, q), Fpq(x) < 1, but G′ab(x) = H(x − γ′(a, b)) = 1, so Fpq(x) = 1, which is a contradiction. Hence, γ(p, q) ≤ γ′(a, b), so g is a non-expansive mapping. Therefore, by Lemma 4.1.1, [g]: (M, Gγ′) ⟶ (S, Gγ) is a morphism, which establishes (2).]

(d): Let (S, F) be a WPMS and ΩF = {ωt}. By Prop A.2.1, for each 0 < t < 1, the path-metric ρt based on ωt is the largest pseudometric on S satisfying ρt ≤ ωt. Since ΩF is linearly ordered, Ω = {ρt} is also linearly ordered. For each 0 < t < 1, let ρt′ = sup{ρs | 0 < s < t}. By Lemma 2.4.1, {ρt′} is a linearly ordered family of pseudometrics that satisfies (lcp), so by Theorem 3.2.1(a)(c), there is a Menger space (S, G) such that ΩG = {ρt′}. Since each ρt′ ≤ ωt, by Lemma 4.1.1, [idS]: (S, F) ⟶ (S, G) is a morphism.

- (3)

- (S, G) is the reflection of (S, F) in WPM.

Note to editors: the font has changed in the next paragraph…

[Let [f]: (S, F) ⟶ (S*, F*) be a WP-morphism to a Menger space, where ΩF* = {ωt*}. By Lemma 4.1.1, for each t, f: (S, ωt) ⟶ (S*, ωt*) is non-expansive, so ωt*(f(p), f(q)) ≤ ωt(p, q) for p, q ∈ S. Since (S*, F*) is a Menger space, by Prop 2.2.2, ΩF* consists of pseudometrics, so for each t, the equation σt(p, q) = ωt*(f(p), f(q)) defines a pseudometric σt on S satisfying σt ≤ ωt. Hence, by Prop A.2.1, each σt ≤ ρt. By Prop 2.4.1(a), σt = sup{σs | 0 < s < t} ≤ sup{ρs | 0 < s < t} = ρt′. Hence, by Lemma 4.1.1, [f]: (S, G) ⟶ (S*, F*) is a morphism. Therefore, [idS]: (S, F) ⟶ (S, G) is the reflection mapping associated with WPM.] □

The following example illustrates the reflection into Menger spaces.

Example 4.2.1.

- (1)

- In Example 2.1.4, (R, F) is not a Menger space and the distances have the following form: for each 0 < t ≤ 1 and p, q ∈ R,

|

Let 0 < t < 1 and ε = 1 − t, and let ρ be a pseudometric satisfying ρ ≤ ωt. If | p − q | ≤ ε, then ρ(p, q) ≤ ωt(p, q) = 0, so ρ(p, q) = 0. If | p − q | > ε, choose n satisfying 1/n < ε/| p − q | and let xk = (1 − k/n)p + (k/n)q for 0 ≤ k ≤ n. For each k, | xk − xk+1 | = | p − q |/n < ε, so ωt(xk, xk+1) = 0. Hence, ρ(p, q) ≤ ∑ρ(xk, xk+1) ≤ ∑ωt(xk, xk+1) = 0. Therefore, ρ is the zero pseudometric.

The construction used in the proof of Theorem 4.2.1(d) shows that the Menger space reflection of (R, F) is the trivial WPMS (R, {H}).

- (2)

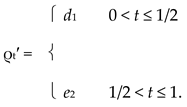

- In Example 2.1.5, (R+, F) is not a Menger space and the distances have the following form: for each 0 < t ≤ 1 and p, q ∈ R+,

|

By definition, e1(p, q) = min{a, b} and e2(p, q) = max{a, b}, where a = | p − q | and b = | p2 − q2 |. In addition, e2 is a pseudometric. Let c = 1/2, A = [0, c], and B = (c, +∞). An analysis of cases shows that the largest pseudometric d1 ≤ e1 is defined by

|

The construction used in the proof of Theorem 4.2.1(d) shows that the Menger space reflection (R+, G) of (R+, F) has the pseudometrics defined by

|

The construction is the one used in the proof of Theorem 3.2.1. One can show that if p, q ∈ A or p, q ∈ B, then Gpq = Fpq. However, if p ∈ A and q ∈ B, then

|

For example, if p = 1/4 and q = 1, then a = 3/4 and b = 15/16. Therefore, Fpq(x) = 0 for 0 ≤ x ≤ 3/4 and Gpq(x) = 1/2 for 11/16 < x < 3/4, so Fpq ≠ Gpq.

5. Discussion and Future Work

In some sense, the paper represents a step backwards instead of forwards since it addresses the fundamental issues rather than more contemporary work. However, the results speak for themselves. The most significant ones are (i) the construction of WPMSs from linearly ordered families (Theorems 2.4.1 and 3.2.1), (ii) the introduction of finite range WPMSs and related results (Theorems 2.3.1 and 3.2.2, and Example 4.1.3), (iii) the definition and characterization of generalized Menger spaces (Theorem 3.4.1), and (iv) the presentation of a categorical framework where the Menger spaces are a reflective subcategory (Theorem 4.2.1).

I did not emphasize the point in Section 1.1, but there is a significant amount of recent research on new ideas about distances employed in connection with fixed point theory. The reader is referred to [23,24] for the details. These papers also contain many additional references for the interested reader. Without attempting any summary here, I can say that the work introduces generalized distribution functions on Menger spaces with a t-norm which greatly expands the scope of the subject and potential applications.

Finally, in the text, I mentioned the general problem of classifying WPMSs. The originator of the subject was aware of this issue and proposed interesting ideas in ([25], pp. 441–444) that were used in ([20], Section 3), but have not gained much attention. The geometric properties of distances that we have mentioned may play a role. In my opinion, the classification problem is the most interesting foundational issue. A potential sequel to the present paper may address it in some detail.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Distance Spaces

In this appendix, we discuss distance-spaces and present some accompanying geometric conditions that can be imposed on them.

Appendix A.1. Distances

We say that a mapping d: M × M ⟶ R+ is a distance on a set M if d(x, x) = 0 for each x ∈ M and d(x, y) = d(y, x) for each x, y ∈ M. If d(x, y) > 0 for each distinct pair x, y ∈ M, then d is called a semi-metric. We say that (M, d) is a distance-space (resp. semi-metric space) if d is a distance (resp. semi-metric) on M. Let f: (M, d) ⟶ (N, e) be a mapping between distance-spaces. We say that f is uniformly continuous if for each ε > 0, there exists δ > 0 such that for each x, y ∈ M, d(x, y) < δ ⟹ e(f(x), f(y)) < ε; non-expansive if for x, y ∈ M, e(f(x), f(y)) ≤ d(x, y), and a uniform equivalence if f is a bijection and f and f−1 are uniformly continuous.

Appendix A.2. Covers and Pseudometrics

Let CX denote the family of covers on a set X. For U, V ∈ CX, we write U < V if for each U ∈ U, there is V ∈ V such that U ⊆ V. For U ∈ CX,

Uδ = {St(x, U) | x ∈ X}, where St(x, U) = ∪{U ∈ U | x ∈ U}

U* = {St(V, U) | V ∈ U}, where St(V, U) = ∪{U ∈ U | U ∩ V ≠ ∅}.

We write U <δ V if Uδ < V and U <* V if U* < V. If U, V, W ∈ CX, U <δ V, and V <δ W; then, U <* W. A family {Uk | k ∈ N} ⊆ CX is a normal sequence if Uk+1 <* Uk for each k.

For a distance space (X, d) and r > 0, S(d, r) = Sd(r) = {Sd(x, r) | x ∈ X} is the cover by open spheres and Bd(r) = {Bd(x, r) | x ∈ X} is the cover by closed spheres, where Sd(x, r) = {y ∈ X | d(x, y) < r} and Bd(x, r) = {y ∈ X | d(x, y) ≤ r}.

Prop A.2.1.

For each distance-space (M, ω), there is a largest pseudometric dω on M such that dω ≤ ω.

Proof.

Given x, y ∈ M, we say that P = (x0, …, xn) is a path in M from x to y if x = x0, y = xn, and each xk ∈ M. The path-length ωP is defined by ωP(x, y) = ∑{ω(xk, xk+1) | 0 ≤ k < n}. Then the path-metric dω on M is defined by

dω(x, y) = inf{ωP(x, y) | P is a path in M from x to y}.

The reader can verify that dω is a pseudometric and if ρ is a pseudometric on M satisfying ρ ≤ ω, then ρ ≤ dω. □

The next result states the well-known connection between pseudometrics and normal sequences of covers.

Prop A.2.2.

Let {Uk} be a normal sequence of covers on a set X with U0 = {X} and let rk = 2−k for each k ≥ 0. For each x, y ∈ X, define ω(x, y) = inf{rk | y ∈ St(x,Uk)}. Then (i) Uk < Bd(2−k) and Sd(2−k) < Ukδ for each k > 0 and (ii) d ≤ ω ≤ 2d, where d = dω.

Proof.

The result (i) is found in ([26], I.14). To prove (ii), we use a statement similar to the one on ([24], page 8, line 22): (#) ≡ d(x, y) < rk ⟹ y ∈ St(x, Uk+1*). By (#), if d(x, y) = 0, then y ∈ St(x, Uk) for each k, so ω(x, y) = 0. If d(x, y) > 0, then either (a) d(x, y) = rk or (b) rk+1 < d(x, y) < rk for some k. (a): If k = 0, then ω(x, y) ≤ r0 = d(x, y); otherwise, by (#), d(x, y) < rk−1 ⟹ y ∈ St(x, Uk−1). Hence, ω(x, y) ≤ rk−1 = 2rk = 2d(x, y). (b): By (#), y ∈ St(x, Uk), so ω(x, y) ≤ rk = 2rk+1 < 2d(x, y). □

Appendix A.3. Geometric Conditions

Here are two examples of geometric conditions that can be imposed on a distance-space (M, ω):

- weak polygonal condition

(wpc) ≡ ∀ε > 0 ∃δ > 0 ∀paths P between x, y ∈ M · ωP < δ ⟹ ω(x, y) < ε

- weak triangle condition

(wtc) ≡ ∀ε > 0 ∃δ > 0 ∀x, y, z ∈ M · ω(x, z) < δ and ω(z, y) < δ ⟹ ω(x, y) < ε.

Clearly, (wpc) implies (wtc), but the converse is false. Corresponding to each condition, there is a theorem that states a uniform equivalence with a pseudometric space. First, we establish the following result.

Prop A.3.1.

A distance-space (M, ω) satisfies (wpc) if and only if idM: (M, ω) ⟶ (M, dω) is a uniform equivalence.

Proof.

Suppose (M, ω) satisfies (wpc). Given ε > 0, there is δ > 0 such that for any path P from x to y, ωP < r ⟹ ω(x, y) < ε. If dω(x, y) < δ, then there is a path P from x to y with ωP < δ. Therefore, ω(x, y) < ε, so idM: (M, dω) ⟶ (M, ω) is uniformly continuous. Also, since dω ≤ ω, the mapping idM: (M, ω) ⟶ (M, dω) is non-expansive, so idM is a uniform equivalence. Conversely, suppose idM: (M, dω) ⟶ (M, ω) is uniformly continuous. Given ε > 0, there is δ > 0 such that for x, y ∈ M, dω(x, y) < δ ⟹ ω(x, y) < ε. If P is a path between x and y such that ωP < δ, then dω(x, y) ≤ ωP < δ. Hence, ω(x, y) < ε, so ω satisfies (wpc). □

For the next result, we need to introduce the following notion. We say that a distance-space (M, ω) is a regular écart if there is a non-decreasing mapping φ: [0, +∞) ⟶ (0, +∞) that satisfies

(ec1) For each x, y, z ∈ M, ω(x, z) < r and ω(y, z) < r ⟹ ω(x, y) < φ(r)

(ec2) φ(0+) = φ(0) = 0.

Theorem A.3.1.

The following statements are equivalent for a distance-space (M, ω).

- (a)

- (M, ω) satisfies (wtc).

- (b)

- (M, ω) is a regular écart.

- (c)

- There is a path-metric d on M such that idM: (M, ω) ⟶ (M, d) is a uniform equivalence.

- (d)

- There is a pseudometric d on M such that idM: (M, ω) ⟶ (M, d) is a uniform equivalence.

Proof.

Given ε > 0 and r > 0, define the predicate

Pω(ε, r) ≡ ∀x, y ∈ M · ω(x, y) ≥ ε ⟹ ∀z ∈ M · ω(x, z) + ω(y, z) ≥ r.

Clearly, (c) ⟹ (d).

(d) ⟹ (a): Let ε > 0 and choose δ > 0 such that d(x, y) < δ ⟹ ω(x, y) < ε. Also, choose r > 0 such that ω(x, y) < r ⟹ d(x, y) < δ/2. Suppose ω(x, y) ≥ ε and let z ∈ M. Then d(x, y) ≥ δ, so without loss of generality, we can assume that d(x, z) ≥ δ/2. Therefore, ω(x, z) + ω(y, z) ≥ ω(x, z) ≥ r. Hence, Pω(ε, r) holds, so (M, ω) satisfies (wtc).

To make the remaining proof less cluttered, we put the proofs of statements (1)–(4) at the end.

(b) ⟹ (c): By assumption, there is a non-decreasing mapping φ: (0, +∞) ⟶ (0, +∞) that satisfies (ec1) and (ec2), so we can assume that φ(0) = 0. Then the following statements hold.

- (1)

- For each x ∈ M and r > 0, St(x, Sω(r)) ⊆ Sω(x, φ(r)).

- (2)

- There is a decreasing sequence {εk} ⊆ (0, 1] converging to 0 with ε0 = ε1 = 1 such that φ(εk+1) < εk and Sω(εk+1) <* Sω(εk) for each k > 0.

Let {εk} be a sequence that satisfies the conditions in (2). Let A0 = {M} and Ak = Sω(εk) for k > 0. By (2), {Ak} is a normal sequence. Define the distance σ on M by σ(x, y) = inf{2−k | y ∈ St(x, Ak)} and let dσ be the induced path-metric. Then by Prop A.2.2(ii), dσ ≤ σ ≤ 2dσ, so σ and dσ are uniformly equivalent.

- (3)

- ω and σ are uniformly equivalent, so dσ and ω are uniformly equivalent. Hence, part (c) holds.

(a) ⟹ (b): Without loss of generality, assume that Δ = diamω(M) > 0.

Case 1: Δ = +∞ or Δ < +∞ and Rng(ω) ⊆ [0, Δ).

- (4)

- (i): If Δ = +∞, then there is a non-decreasing g: (0, +∞) ⟶ (0, +∞) such that Pω(ε, g(ε)) holds for each ε > 0. (ii) If Δ < +∞ and Rng(ω) ⊆ [0, Δ), then there is a non-decreasing g: (0, Δ) ⟶ (0, Δ] such that Pω(ε, g(ε)) holds for each 0 < ε < Δ.

Subcase 1: L = limε ⟶ Δ−g(ε) = +∞.

For each r > 0, Br = {ε > 0 | g(ε) ≥ r} ≠ ∅. Define τ: (0, +∞) ⟶ [0, +∞) by τ(r) = inf(Br). If 0 < r < r′, then Br′ ⊆ Br, so τ(r) ≤ τ(r′). Hence, τ is non-decreasing. Define φ: (0, +∞) ⟶ (0, +∞) by φ(r) = τ(2r) + r. Then φ is also non-decreasing.

Suppose x, y ∈ M and ω(x, y) ≥ φ(r) for some r > 0. Let z ∈ M and let s = ω(x, z) + ω(y, z). Since ω(x, y) > τ(2r) = inf(B2r), there is ε ∈ B2r such that ω(x, y) > ε. Then by (4), s ≥ g(ε) ≥ 2r, so either ω(x, z) ≥ r or ω(y, z) ≥ r. Hence, φ satisfies (ec1).

Subcase 2: L = limε ⟶ Δ−g(ε) < +∞.

For each 0 < r < L, Br = {0 < ε < Δ | g(ε) ≥ r} ≠ ∅. Define τ: (0, L) ⟶ [0, Δ) by τ(r) = inf(Br). As in Subcase 1, τ is non-decreasing, so K = limr ⟶ L−τ(r) exists and K ≤ Δ. Now define τ on (0, +∞) by assigning τ(r) = K for each r ≥ L. Then τ: (0, +∞) ⟶ (0, Δ] is non-decreasing. Define φ: (0, +∞) ⟶ (0, +∞) by φ(r) = τ(2r) + 4rΔ/L. Then φ is also non-decreasing.

Suppose x, y ∈ M and ω(x, y) ≥ φ(r) for some r > 0. Let z ∈ M and let s = ω(x, z) + ω(y, z). If r ≥ L/2, then ω(x, y) ≥ 4rΔ/L ≥ 2Δ, which is impossible. Since r < L/2, ω(x, y) > τ(2r) = inf(B2r), so there is ε ∈ B2r such that ω(x, y) > ε. As in Subcase 1, by (4), either ω(x, z) ≥ r or ω(y, z) ≥ r, so φ satisfies (ec1).

If a = limn ⟶ +∞τ(1/n) > 0, choose 0 < x < a. If L < +∞, then for each n > 1/L, x < τ(1/n) = inf(B1/n), so g(x) < 1/n. Hence, g(x) = 0, which is a contradiction. Hence, a = 0, so φ(0+) = 0. If L = +∞, the same proof works, so in either case, φ satisfies (ec2).

Case 2: Δ < +∞ and Δ ∈ Rng(ω).

Let M′ = M ∪d B, where B = (0, Δ + 1) and define ω′: M′ × M′ ⟶ R+ by ω′(x, y) = ω(x, y) if x, y ∈ M, ω′(x, y) = | x − y | if x, y ∈ B, and ω′(x, y) = ω′(y, x) = 1 if x ∈ M and y ∈ B. Evidently, diamω′(M′) = Δ + 1 and Rng(ω′) ⊆ [0, Δ + 1). By part (a), given ε > 0, choose r > 0 such that Pω(ε, r) holds. Then Pω′(ε, min{r, ε, 1}) holds, so (M′, ω′) satisfies (wtc). Hence, by Case 1, (M′, ω′) is a regular écart, so (M, ω) is also a regular écart. □

Proof

(intermediate statements).

- (1)

- For each x ∈ M and r > 0, St(x, Sω(r)) ⊆ Sω(x, φ(r)).

If x ∈ Sω(p, r) for some p ∈ M, then ω(x, p) < r and ω(p, y) < r for each y ∈ Sω(p, r), so by (ec1), ω(x, y) < φ(r). Hence, St(x, Sω(r)) ⊆ Sω(x, φ(r)).

- (2)

- There is a decreasing sequence {εk} ⊆ (0, 1] converging to 0 with ε0 = ε1 = 1 such that φ(εk+1) < εk and Sω(εk+1) <* Sω(εk) for each k > 0.

Let ε0 = ε1 = 1 and suppose ε1, …, εk have been defined for k > 0 such that the two conditions hold. By (ec2), there is r > 0 such that r < εk and φ(r) < εk and there is 0 < εk+1 < εk such that φ(εk+1) < r. Then φ(εk+1) < εk and by (1), Sω(εk+1) <δ Sω(φ(εk+1)) and Sω(φ(εk+1)) < Sω(r) <δ Sω(φ(r)) < Sω(εk). Hence, by our earlier remarks, Sω(εk+1) <* Sω(εk).

- (3)

- σ are uniformly equivalent, so dσ and ω are uniformly equivalent.

Let x, y ∈ M. If σ(x, y) ≤ 2−(k+1) for some k ≥ 0, then y ∈ St(x, Ak+1), so there is z ∈ M such that x, y ∈ Sω(z, εk+1). Hence, by (ec1) and (2), ω(x, y) < φ(εk+1) < εk. Conversely, if ω(x, y) < εk for some k > 1, then y ∈ St(x, Ak), so σ(x, y) ≤ 2−k.

- (4)

- (i): If Δ = +∞, then there is a non-decreasing g: (0, +∞) ⟶ (0, +∞) such that Pω(ε, g(ε)) holds for each ε > 0. (ii) If Δ < +∞ and Rng(ω) ⊆ [0, Δ), then there is a non-decreasing g: (0, Δ) ⟶ (0, Δ] such that Pω(ε, g(ε)) holds for each 0 < ε < Δ.

By part (a), for each ε > 0, Sε = {r > 0 | Pω(ε, r)} ≠ ∅.

(i): Let ε > 0 and choose x, y ∈ M such that ω(x, y) > ε. If r ∈ Sε, then ω(x, y) + ω(y, y) ≥ r, so Sε ⊆ (0, ω(x, y)]. Define g: (0, +∞) ⟶ (0, +∞) by g(ε) = sup(Sε). If 0 < ε < ε′, then Sε ⊆ Sε′, so g(ε) ≤ g(ε′). Hence, g is non-decreasing. If x, y ∈ M satisfies ω(x, y) ≥ ε > 0, then for each r ∈ Sε and z ∈ M, ω(x, z) + ω(y, z) ≥ r. Hence, ω(x, z) + ω(y, z) ≥ g(ε), so Pω(ε, g(ε)) holds.

(ii): Let 0 < ε < Δ. The argument used in (i) shows that Sε ⊆ (0, Δ]. Define g: (0, Δ) ⟶ (0, Δ] by g(ε) = sup(Sε). Then the previous argument shows that each Pω(ε, g(ε)) holds. □