Abstract

Designing laboratory experiences that support both skill development and conceptual understanding is a persistent challenge in introductory chemistry education—especially within accelerated or compressed course formats. To address this need, we developed and implemented a systems-thinking-based laboratory module on error analysis for a large introductory chemistry course at Brown University, composed primarily of first-year students (approximately 150–200 students in the spring semesters). Unlike traditional labs that isolate single techniques or concepts, this module integrates calorimetry, precipitation reactions, vacuum filtration, and quantitative uncertainty analysis into a unified experiment. Students explore how procedural variables interact to affect experimental outcomes, promoting a holistic understanding of accuracy, precision, and uncertainty. The module is supported by multimedia pre-lab materials, including faculty-recorded lectures and interactive videos developed through Brown’s Undergraduate Teaching and Research Awards (UTRA) program. These resources prepare students for hands-on work while reinforcing key theoretical concepts. A mixed-methods assessment across four semesters (n > 600) demonstrated significant learning gains, particularly in students’ ability to analyze uncertainty and distinguish between accuracy and precision. Although confidence in applying significant figures slightly declined post-lab, this may reflect increased awareness of complexity rather than decreased understanding. This study highlights the educational value of integrating systems thinking into early-semester laboratory instruction. The module is accessible, cost-effective, and adaptable for a variety of institutional settings. Its design advances chemistry education by aligning foundational skill development with interdisciplinary thinking and real-world application.

1. Introduction

Introductory chemistry laboratories represent a unique pedagogical challenge. They are expected to bridge the gap between abstract theory and empirical practice, introduce students to essential techniques and safety protocols, and cultivate habits of scientific inquiry—yet they must do so for students who arrive with vastly different levels of preparation [1]. Some learners bring substantial prior laboratory experience from Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate courses, while others encounter experimental chemistry for the first time. This variation in background knowledge, confidence, and familiarity with scientific practices requires a laboratory curriculum that is inclusive, rigorous, and adaptable.

Traditionally, introductory chemistry labs address these challenges by isolating techniques and concepts—calorimetry in one experiment, precipitation in another, error analysis confined to a final calculation or post-lab question. While effective for building procedural fluency, this fragmented design can obscure the fact that chemical processes are inherently interconnected and that experimental outcomes are shaped by the cumulative effects of decisions made at every stage. Students may master individual steps without developing the ability to see how those steps interact within a larger system.

Systems thinking offers a framework to address this gap. Rooted in the recognition that outcomes emerge from the interactions of interdependent components, systems thinking encourages learners to look beyond linear cause-and-effect and to analyze how variations in one part of a process ripple through the whole. In the context of chemistry, this means recognizing how small measurement errors propagate across procedures, how early technique choices influence later results, and how experiments unfold as dynamic networks rather than isolated tasks. Integrating systems thinking into the laboratory has the potential to cultivate not only technical proficiency but also higher-order reasoning, reflection, and adaptability.

At Brown University, the need for such an approach is intensified by the structure of our accelerated introductory chemistry curriculum, which condenses a year’s worth of material—quantum mechanics, molecular structure, bonding, equilibrium, thermodynamics, kinetics—into a single semester. Laboratory instruction must therefore be both efficient and impactful, reinforcing complex ideas within a limited timeframe while preparing students for more advanced coursework. Recognizing this challenge, we developed an early-semester laboratory module to foreground systems thinking as a guiding pedagogical principle. This is a multi-technique lab module centered on error analysis as a unifying theme. Rather than presenting calorimetry, precipitation reactions, and vacuum filtration as discrete exercises, we embedded them into a coherent, systems-oriented experimental sequence. Each step was deliberately connected to the next, with students prompted to reflect on how procedural decisions influenced subsequent outcomes. By experiencing the propagation of error in real time, students engaged directly with the systemic nature of experimental work and developed a more sophisticated approach to evaluating data and interpreting results.

Ultimately, our goal was not only to prepare students for the technical demands of advanced laboratory courses, but also to foster curiosity, resilience, and a sense of agency as emerging scientists. By embedding systems thinking at the start of their undergraduate experience, we sought to help students see chemistry as an integrated discipline, error analysis as a process rather than a calculation, and laboratory practice as a dynamic system of interdependent choices.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Over the past two decades, systems thinking has gained considerable traction within STEM education, emerging as a key framework for cultivating interdisciplinary understanding, analytical reasoning, and adaptive problem-solving skills. This approach has moved beyond its roots in ecology and engineering to influence pedagogical strategies across mathematics, biology, physics, and increasingly, chemistry. At its core, systems thinking encourages learners to perceive the world not as a set of isolated facts or discrete events but as a network of interrelated components governed by dynamic relationships, feedback loops, and equilibrium processes. It emphasizes pattern recognition, the ability to predict outcomes, and causal reasoning across multiple temporal and spatial scales. In doing so, it cultivates the higher-order cognitive skills that are essential for navigating complex scientific and societal problems.

Within educational research, systems thinking is commonly defined by its emphasis on examining how components within a system influence one another over time and in context. This perspective challenges reductionist instructional approaches that treat scientific phenomena as separable and self-contained. Instead, systems thinking foregrounds complexity, interaction, and emergence—qualities that more accurately reflect the nature of real-world problems and scientific inquiry. By encouraging students to make connections across scales, disciplines, and conceptual domains, systems thinking fosters not only deeper content comprehension but also transferable skills such as modeling, synthesis, and reflective evaluation.

In science education broadly—and in chemistry education specifically—the value of systems thinking is increasingly acknowledged. Chemistry, by nature, is a discipline of interconnected variables. Changes in a single parameter—temperature, concentration, or pH—can set off a cascade of effects that alter equilibrium states, energy transformations, and observable outcomes. In the context of laboratory instruction, these interactions become even more pronounced. Experiments consist of procedural chains in which early decisions can affect downstream results. Measurement error, technique variation, and equipment limitations interact in ways that compound or mitigate uncertainty. Teaching students to recognize these dependencies is essential for cultivating both conceptual mastery and experimental literacy.

Early foundational work by Assaraf and Orion [2] identified systems thinking as a critical component in students’ ability to comprehend environmental systems, linking microscopic changes to macroscopic phenomena. Their research demonstrated that systems-oriented curricula helped students bridge disciplinary gaps and understand the broader significance of scientific processes. Building upon this, York and Orgill [3,4] developed a detailed framework for integrating systems thinking into general chemistry education. Their work highlighted how systems-oriented instruction improved student understanding of equilibrium, thermodynamic cycles, sustainability, and interdisciplinary problems by framing chemistry as a cohesive system rather than a collection of fragmented topics.

Mahaffy and colleagues [5,6,7] expanded on this perspective, calling for a fundamental reimagining of chemistry curricula through the lens of systems thinking. They argued that contemporary challenges—such as climate change, energy production, environmental degradation, and global health—cannot be addressed using traditional disciplinary boundaries. Chemistry education, therefore, must evolve to emphasize systems-level reasoning, connecting molecular processes to global outcomes and empowering students to think critically about their role as scientific citizens. This call has spurred the development of instructional models that embed sustainability, complexity, and feedback processes into both lecture and laboratory settings. Mahaffy and colleagues also suggested that chemistry education needs to help learners use systems thinking to see the interconnections both among branches within the discipline itself and between chemistry and other disciplines and domains within and outside of the natural sciences. Of particular importance is the interplay between chemistry and earth and societal systems.

The emerging area of the systems thinking in chemistry education (STICE) framework, formulated by an international IUPAC project (IUPAC, 2017-010-1-050), has the goal of articulating strategies and exemplars for infusing systems thinking into chemistry education, with a focus on postsecondary first-year or general chemistry. A special issue: “Reimagining Chemistry Education: Systems Thinking, and Green and Sustainable Chemistry” dedicated to this topic was recently published in the Journal of Chemical Education (Vol. 96, issue 12, Dec. 2019). This STICE framework places the learner in the center of a system of learning, with three interconnected subsystems: (1) Educational Research & Theories, (2) The Chemistry Teaching & Learning, and (3) The Earth & Societal Systems. In their representation gears as a visual metaphor for the three nodes, emphasizing the dynamic interconnection of the nodes as a part of a system of learning, and the influence that the activity of each element of learning has on the others. The Educational Research & Theories node explores and describes the processes at work for students, including the following: learning theories, learning progressions, cognitive and affective aspects of learning, and social contexts for learning. The Chemistry Teaching & Learning node applies general understanding of how students learn to the unique challenges of learning chemistry. These include the use of pedagogical content knowledge; analysis of how intended curriculum is enacted, assessed, learned, and applied; and incorporation of student learning outcomes that include responsibility for the safe and sustainable use of chemistry. The Earth & Societal Systems node orients chemistry education toward meeting societal and environmental needs articulated in initiatives such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the Planetary Boundaries framework.

Schultz et al. [8] showed that the benefits of systems thinking go beyond helping students connect chemical concepts. By having secondary students create open-ended maps of socio-scientific issues, the researchers were able to measure clear growth in students’ systems-reasoning skills. Across three classroom settings, students’ maps became more detailed and sophisticated, showing stronger causal links and better integration of chemical and societal ideas. Their findings indicated that students exposed to systems-based instruction demonstrated stronger conceptual clarity, greater retention, and improved knowledge transfer across domains. Similarly, Reinagel and Bray Speth found that undergraduate students engaged in structured systems mapping exercises developed improved causal reasoning, particularly in describing complex, multi-step processes such as titrations and redox reactions [9]. These studies underscore the cognitive and metacognitive gains associated with systems-based pedagogy.

Laboratory education presents a particularly promising venue for implementing systems thinking. Unlike lectures, which are often constrained by time and content pacing, labs offer space for experimentation, reflection, and synthesis. Ho [10] introduced systems thinking into physical chemistry labs by integrating error analysis and procedural feedback into each stage of the experimental process. Students reported increased confidence in interpreting data and assessing reliability. Likewise, Moon, Stanford, and Towns [11] argued that systems-based assessment frameworks encouraged students to prioritize synthesis over rote memorization, leading to improved scientific reasoning and greater experimental intuition.

Despite these advantages, few introductory chemistry laboratories are intentionally designed with systems thinking as a core pedagogical framework. Systems thinking has primarily been applied in classroom instruction, particularly in contexts such as green chemistry, environmental science, and sustainability [3]. In general chemistry courses, systems thinking approaches have been used to help students connect molecular-level concepts to global sustainability issues [6]. However, most studies on systems thinking in education have been concentrated in the life sciences, geosciences, and engineering, with relatively few situated in the physical sciences.

Importantly, there are few—if any—reports on applying systems thinking frameworks to hands-on laboratory teaching and practice in introductory or general chemistry. A recent study by Reynders et al. [12] described the development of systems thinking in a large first-year chemistry course through a group activity on detergents, implemented after students had nearly completed two semesters of general chemistry and were beginning introductory organic chemistry. By contrast, the present work integrates systems thinking directly into an engaging laboratory module for a large introductory chemistry course composed primarily of first-year students. Implemented early in the semester, this module is designed to heighten students’ awareness of experimental error and error analysis within a systems thinking, better preparing them for success in subsequent, more advanced courses. Thus, incorporating systems thinking into early-semester general chemistry laboratory experiences represents a critical step in strengthening students’ conceptual foundations.

While many introductory chemistry labs address concepts such as calorimetry, stoichiometry, and error analysis, they often do so in isolation. For example, Treptow [13], Butcher and Quintus [14], and Kratochvil et al. [15] highlight accuracy and precision through experiments with graduated cylinders, titrations, and particulate sampling, foregrounding uncertainty in measurement. Prilliman [16], Jordan [17], and Bularzik [18] extend this focus with inquiry-based or comparative designs—such as density determination, precision versus accuracy analysis, and the penny experiment—that encourage students to confront error through data interpretation rather than abstract calculation. Similarly, Hill and Nicholson [19], Sen [20], and Burgstahler and Bricker [21] illustrate how simple or everyday systems, from bead hydration to calorimetry with dry ice, can serve as vehicles for teaching measurement reliability.

Other studies refine calorimetric approaches: Ngeh et al. [22], Barth and Moran [23], and Herrington [24] demonstrate how adjustments to methodology or inquiry-based framing can better connect experimental technique to data quality. Statistical perspectives are also integrated into lab instruction, as seen in the work of Cacciatore and Sevian [25], Guedens et al. [26], and Harvey [27], who show how stoichiometry, worked examples, and indicator evaluations scaffold error treatment for undergraduates. Finally, Edmiston and Williams [28] and Salzsieder [29] present structured exercises in repeated measurement and statistical evaluation, illustrating how sustained engagement with variability deepens understanding of uncertainty and reproducibility.

Collectively, these labs can be valuable for developing procedural fluency, yet they frequently neglect to highlight the interconnections between variables, the propagation of measurement error, or the systemic impact of methodological decisions. Error analysis is often relegated to the final section of a lab report rather than embedded throughout the experimental process. This fragmented approach limits students’ ability to appreciate chemistry as an integrated, dynamic system and reduces opportunities for metacognitive growth.

Moreover, many traditional labs make use of overly simplified materials (e.g., food coloring, pennies, beads) or tools with limited precision, which can unintentionally obscure key concepts. While such approaches aim to be approachable for beginners, they often fail to demonstrate how complexity arises in real chemical systems. Other labs, especially those that introduce stoichiometry or thermochemistry early in the semester, can become mathematically intensive without sufficient scaffolding, overwhelming novice learners and reinforcing the perception that chemistry is disconnected from real-world experience.

As a result, there is a pressing need for laboratory modules that integrate systems thinking with accessible experimental techniques in ways that are conceptually rich, pedagogically sound, and developmentally appropriate. Such modules should engage students in multi-step experimental sequences where decisions at each stage—how to measure, mix, heat, filter, or record data—affect subsequent steps and outcomes. They should embed error analysis into every phase of the experiment, prompting students to reflect continuously on the consequences of their actions, the reliability of their measurements, and the interpretability of their results.

The benefits of addressing this pedagogical gap are substantial. Systems-oriented labs have the potential to increase student engagement, promote long-term conceptual retention, and improve students’ ability to transfer knowledge from lab to lecture and beyond. They align with broader calls in chemistry education for holistic, interdisciplinary, and sustainability-driven teaching. When designed with intention, such labs can transform introductory experiences into meaningful foundations for scientific identity development, critical thinking, and informed action.

In response to this opportunity, we designed a novel laboratory module that deliberately incorporates systems thinking into its experimental structure and pedagogical scaffolding. Drawing on prior research and best practices, our goal was to create a module that supports students in developing both foundational laboratory competencies and systems-level reasoning. This includes understanding how uncertainties propagate across procedures, how technique and instrument choice affect accuracy and precision, and how scientific processes unfold as interconnected, dynamic systems. By integrating student-designed multimedia resources—such as animated pre-lab videos—we further aimed to scaffold complex ideas and foster peer-to-peer engagement. In this way, the module not only introduces chemistry content but also models the cognitive and collaborative processes of doing science in the real world.

3. Learning Goals and Research Questions

The laboratory module described in this study was developed with a set of interrelated pedagogical goals designed to address both the cognitive and practical demands of introductory chemistry instruction. Grounded in current best practices and supported by emerging research in STEM education, the module seeks to create a transformative learning environment that fosters skill development, conceptual integration, and systems-level reasoning. Recognizing that first-year undergraduate students often enter the laboratory with a wide range of academic backgrounds, confidence levels, and exposure to scientific experimentation, we intentionally designed the module to be inclusive, engaging, and intellectually rigorous.

The primary learning objectives of the module are threefold:

(1) To develop essential laboratory competencies that will serve as a foundation for upper-level coursework. These competencies include measurement accuracy, data collection and analysis, safe handling of materials, proper use of laboratory equipment, and critical evaluation of experimental procedures. By introducing these core skills early in the semester, we aim to enhance students’ preparedness for more complex techniques and investigations later in their academic trajectory.

(2) To introduce the principles and applications of systems thinking to the first-year college students. This goal reflects the increasing consensus that students benefit from engaging with systems-based reasoning from the beginning of their STEM education. Our module emphasizes concepts such as interdependence, feedback, propagation of error, and causal chains, helping students develop both conceptual comprehension and analytical problem-solving abilities.

(3) To ensure that all laboratory activities are conducted using materials and equipment that are safe, sustainable, and environmentally responsible, and that these activities are designed to be accessible to students with varied prior laboratory experience. We prioritized the selection of non-toxic reagents, reusable or recyclable materials, and low-waste experimental designs, with the broader goal of aligning laboratory instruction with the values of sustainability and equity.

In addition to these core goals, the module promotes scientific habits of mind such as reflective thinking, attention to detail, and evidence-based reasoning. Through repeated opportunities for students to interpret data, assess the reliability of their results, and draw conclusions based on observed patterns and sources of uncertainty, we aim to foster scientific confidence and intellectual independence. The structure of the lab encourages metacognitive engagement, requiring students to think not only about what they are doing but also why they are doing it—and how their choices affect outcomes.

These learning goals were not only shaped by institutional and curricular considerations but also informed by a robust body of literature in science education. Theoretical frameworks including constructivist learning theory, situated cognition, and systems thinking pedagogy suggest that students learn most effectively when they can link abstract content to hands-on, contextually meaningful experiences. By targeting both procedural fluency and conceptual synthesis, the lab seeks to bridge the often-perceived divide between theoretical instruction and practical experimentation—a divide that can be particularly pronounced in accelerated or content-dense introductory courses.

This manuscript provides a detailed examination of the theoretical foundation, pedagogical design, and empirical implementation of the laboratory module across multiple academic semesters. We analyze student learning through both qualitative and quantitative measures, drawing from student reflections, survey data, and performance on lab assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of our approach. Our central research question focuses on whether the integration of systems thinking into early-semester, multi-technique laboratory instruction can produce meaningful improvements in student learning outcomes.

More specifically, we explore several interrelated research questions:

- To what extent does a systems thinking-based laboratory module improve students’ confidence in applying error analysis concepts, including accuracy, precision, uncertainty, and error propagation?

- How does embedding systems thinking throughout the experimental process affect students’ ability to connect procedural choices with experimental outcomes?

- In what ways do pre-laboratory multimedia resources—particularly student-created videos—enhance students’ conceptual readiness, confidence, and engagement with error analysis?

- How effectively do students transfer their learning from this module to demonstrate measurable gains in specific error analysis skills (e.g., significant figure application, distinguishing accuracy vs. precision, calculating uncertainty)?

Together, these research questions aim to illuminate the potential of systems thinking as both a pedagogical tool and a cognitive framework for laboratory learning. We hypothesize that embedding systems thinking within the structure and delivery of the lab—along with the use of student-generated multimedia—will promote deeper engagement, improved comprehension, and a stronger alignment between experimental practice and conceptual understanding.

4. Methodology

4.1. Lab Design and Implementation

The laboratory module was implemented as a hands-on laboratory experience in the early semester of Brown University’s accelerated introductory chemistry sequence. This placement was strategic: occurring early enough to set foundational expectations for scientific inquiry, but late enough for students to have completed initial training in safety protocols and basic lab techniques. Each lab section accommodates 17 to 18 students, who are assigned to work in pairs to promote collaboration, reduce resource consumption, and foster peer-to-peer learning. Sessions are scheduled for a four-hour block, though the lab typically takes two to three hours to complete, allowing time for in-lab reflection and preliminary data analysis.

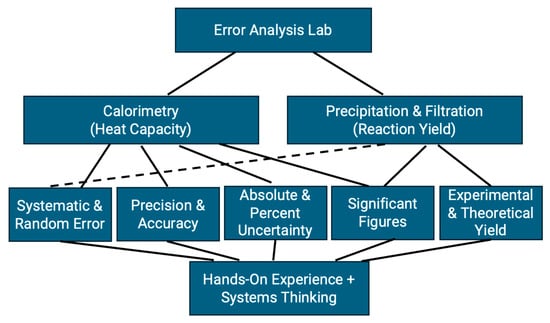

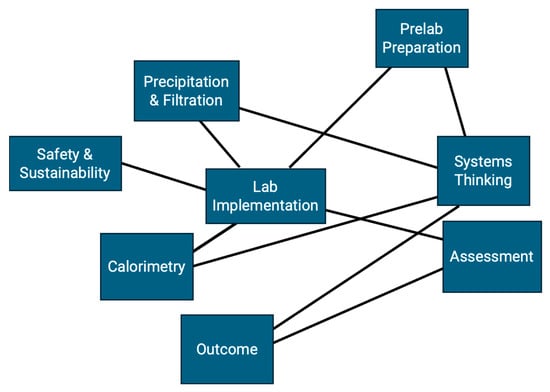

The module consists of two interconnected components, each contributing to the overarching goal of introducing systems thinking and error analysis through practical experimentation. Full procedural details are provided in the lab manual (Supplementary Materials SI), which students are encouraged to consult throughout the lab as a resource for planning and evaluating each experimental step. The module integrates two laboratory activities: (1) determining the specific heat capacity of an unknown metal using a calorimeter, and (2) measuring reaction yield through vacuum filtration and precipitation techniques. Together, these activities engage students with five key sub-areas of error analysis—systematic and random error, precision and accuracy, absolute and percent uncertainty, significant figures, and experimental versus theoretical yield. Each experiment highlights multiple sub-areas with intentional overlap, reinforcing the interconnected nature of error analysis. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the conceptual framework and methodology of the module, showing how diverse error analysis concepts are unified within a systems-thinking approach.

4.2. Pre-Laboratory Preparation

To ensure that students enter the lab session with adequate background knowledge and a systems-thinking mindset, a series of structured pre-lab activities are required. These materials were carefully designed to reduce cognitive load during lab execution and to support students in making informed decisions throughout the experiment. The pre-lab assignment includes the following components:

- A structured lab notebook setup guide that outlines key procedural steps, prompts students to write hypotheses and predictions, and emphasizes learning objectives.

- A written question set that focuses on predicting experimental outcomes, identifying potential sources of random and systematic error, and interpreting relationships between variables.

- A 40-min faculty-recorded pre-lab lecture, which introduces relevant theory, explains procedural steps, and discusses laboratory safety.

Two interactive multimedia videos, co-developed through Brown’s Undergraduate Teaching and Research Awards (UTRA) program, that illustrate the concepts of error propagation and systems-based reasoning in engaging, student-friendly formats.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing depicting how multiple sub-concepts of error analysis are integrated into a single hands-on lab module, incorporating systems thinking.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing illustrating the methodology of the error analysis lab module integrated with systems thinking. The lab implementation includes multiple components—pre-lab preparation, precipitation and filtration, calorimetry, safety and sustainability, and assessment—while systems thinking is interwoven throughout these components.

4.3. Student-Created Multimedia Resources

The videos, both created by a collaborative team of undergraduates, graduate teaching assistants, and faculty, serve as a cornerstone of the pre-lab learning experience. These videos are:

4.3.1. Video 1: “Understanding Sources of Error”

This video (https://youtu.be/UxPQnFrkHz0?si=4LZZEGegMY29vq6q (accessed on 1 November 2024) see Supplementary Materials SII) uses real-life laboratory footage to demonstrate common mistakes and variations in technique. Examples include measuring pH with and without calibrating the probe, weighing compounds with and without a draft shield, and using pipettes with and without proper technique. The goal is to distinguish between random error (inconsistencies between trials) and systematic error (consistent deviation due to flawed technique or equipment).

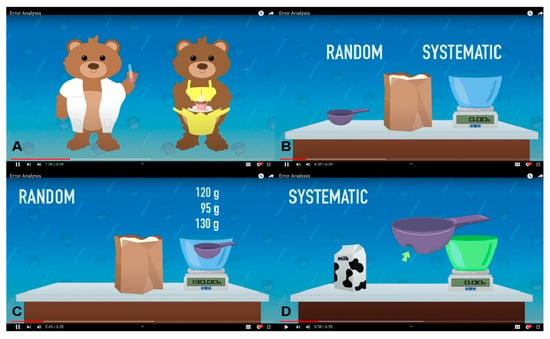

4.3.2. Video 2: “Error Analysis”

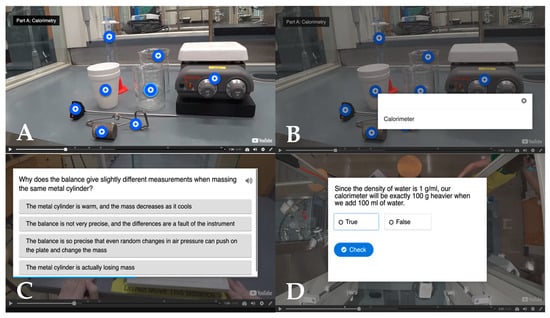

This animated video (https://sites.brown.edu/chemistrylab/2024/01/11/12/ (accessed on 1 November 2024) (see Supplementary Materials SIII) uses a cooking metaphor to explain how errors propagate in multi-step processes. For example, random error is illustrated through variation in scooping flour with an uneven spoon, while systematic error is represented by repeated mismeasurement due to a dented measuring cup (see Figure 3). The video transitions into interactive live-action segments (see Figure 4), in which students click on various parts of lab equipment to learn their names and functions. These segments include ungraded multiple-choice and true/false questions that reinforce the content and promote active learning.

Figure 3.

Animated portion of instructional video. (A) Use of bear mascots to emphasize real-life applications and to add entertainment. (B) A baking analogy is used to explain random and systematic error. (C) Random error is analogous to inconsistent measurement with a measuring cup. (D) Systematic error is analogous to consistent measurement with a dented measuring cup.

Figure 4.

Interactive portion of instructional video. (A) Experimental set-up shown with interactive buttons. (B) Students are able to press the buttons to display the name of the equipment. (C) Example of a multiple-choice question. (D) Example of a true or false question.

Together, these pre-lab resources are designed to reduce student anxiety, enhance understanding of key concepts, and provide a foundation for in-lab performance. Prior research indicates that visual and interactive content significantly improves novice learners’ ability to transfer theoretical concepts to real-world practice, especially when tackling abstract topics like uncertainty and experimental error.

4.4. Safety Considerations

Safety remains a top priority in all aspects of the laboratory module design. In Part 1, students use hot plates to heat water and handle metal cylinders with tongs. Clear instructions and instructor demonstrations are provided to minimize the risk of burns or accidents. In Part 2, students work with aqueous solutions of CaCl2 and Na2CO3, both of which are low risk but require basic chemical handling protocols. All students are required to wear chemical splash goggles, gloves, and lab aprons throughout the session. Work is conducted under fume hoods where appropriate, and spills are addressed with prompt cleanup and notification procedures.

The materials selected for this lab were chosen not only for their instructional value but also for their safety, affordability, and sustainability. The procedures generate minimal waste, use small quantities of benign reagents, and rely on reusable equipment. These considerations align with Green Chemistry principles and ensure that the module can be easily implemented in a wide range of institutional settings.

4.5. Data Collection and Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness, usability, and pedagogical impact of the laboratory module, we employed a mixed-methods assessment strategy spanning four academic semesters: Spring 2019, Spring 2020, Spring 2023, and Spring 2024. This longitudinal, multi-cohort design enabled us to examine the module’s impact across a range of instructional settings and student populations, capturing not only immediate learning gains but also iterative refinements and long-term trends in student engagement and performance. By incorporating both quantitative and qualitative data, we sought to construct a more nuanced understanding of how students interacted with the module, how their conceptual understanding evolved, and how systems thinking shaped their approach to laboratory work.

The decision to use a mixed-methods framework was motivated by the complexity of our learning goals, which spanned cognitive, affective, and procedural domains. We aimed to assess not only students’ grasp of specific chemistry concepts (e.g., significant figures, sources of error, uncertainty propagation) but also their confidence in applying these ideas, their perceived usefulness of the lab experience, and their reflections on the interconnectedness of experimental steps. This approach allowed us to triangulate our findings, validate patterns across multiple sources, and account for variations in student background, preparation, and response to systems-based instruction.

Data collection instruments were carefully designed and revised over time based on pilot testing, feedback from instructional staff, and evolving research questions. These tools included:

- Pre-lab questionnaires (administered in Fall 2020 and Spring 2024) were used to establish students’ baseline understanding of core concepts in error analysis, including definitions and applications of accuracy, precision, significant figures, uncertainty types (systematic vs. random), and rounding conventions. The questionnaire included a combination of multiple-choice questions, Likert-scale ratings, and short reflective prompts. This format enabled us to quantify students’ initial knowledge while also capturing qualitative insights into their preconceptions and potential areas of confusion.

- Post-lab questionnaires (collected in all four semesters) provided a measure of learning gains, shifts in student confidence, and overall reactions to the systems-oriented lab structure. In addition to repeating key knowledge questions from the pre-lab instrument (to measure conceptual gains), the post-lab survey included open-ended items asking students to reflect on how their understanding of uncertainty had changed, what connections they saw between different procedural steps, and how the lab compared to other chemistry lab experiences. These data offered valuable feedback for iterative improvements to the module design and delivery.

- Quiz and lab report analysis (Spring 2024 only) offered a deeper lens into students’ ability to apply concepts in summative assessment contexts. We selected targeted questions from end-of-lab quizzes and graded reports that addressed critical error analysis themes—e.g., performing multi-step uncertainty calculations, identifying sources of propagation error, and distinguishing between precision-related and technique-related discrepancies. These artifacts provided a measure of knowledge retention, conceptual synthesis, and alignment with our learning objectives.

We analyzed performance trends across semesters to identify improvements or regressions in student outcomes and examined whether the revised instructional scaffolding (e.g., student-designed pre-lab videos introduced in Spring 2024) had a measurable impact on performance or confidence levels. Confidence ratings were tracked using Likert-scale data, and changes were assessed both within individuals (pre- vs. post-lab) and across cohorts. Key results were disaggregated by question type and concept area to diagnose patterns in student understanding.

In parallel, qualitative responses from open-ended questionnaire items were ministered. This open-ended question helped illuminate not only what students learned but also how they were thinking about their learning, which is central to systems-based instruction.

To ensure the ethical handling of student data, all responses were anonymized prior to analysis. No identifying information was linked to individual surveys, assessments, or reflections. The Brown University Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed the project and determined that it did not constitute research involving human subjects, as defined by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations. Consequently, the data collection was approved as exempt from full IRB review, and participation in the study did not affect students’ grades or course standing.

Overall, this comprehensive assessment design enabled us to evaluate not only whether students achieved the targeted learning goals, but also whether they internalized systems thinking as a conceptual framework for approaching laboratory science. The combination of student self-report data, performance metrics, and open-ended reflections provided a rich and multifaceted view of the lab’s educational impact.

5. Assessment Results

The assessment results provide strong evidence that the laboratory module improved student understanding and awareness of error analysis concepts, particularly in areas related to uncertainty and distinguishing between accuracy and precision. Pre-lab questionnaires were distributed in Spring 2020 (n = 138) and Spring 2024 (n = 217), and post-lab questionnaires were administered in Spring 2019 (n = 90), Spring 2020 (n = 133), Spring 2023 (n = 242), and Spring 2024 (n = 207). These instruments were used to track both cognitive and affective outcomes, such as conceptual gains and changes in student confidence regarding core components of error analysis.

Students’ overall perceptions of their knowledge, experience, and confidence with error analysis—covering concepts such as accuracy, precision, uncertainty, and experimental error—were assessed through post-lab questionnaires in all four years. As shown in Table 1, the majority of students reported that their understanding of error analysis had improved after completing the lab. Across years, most students “agreed” or “strongly agreed” (ratings of 4 or 5 on a five-point Likert scale) that the module enhanced their learning, indicating sustained positive impact over multiple course offerings.

Table 1.

Questions pertaining to overall knowledge and confidence growth in using error analysis skills after lab.

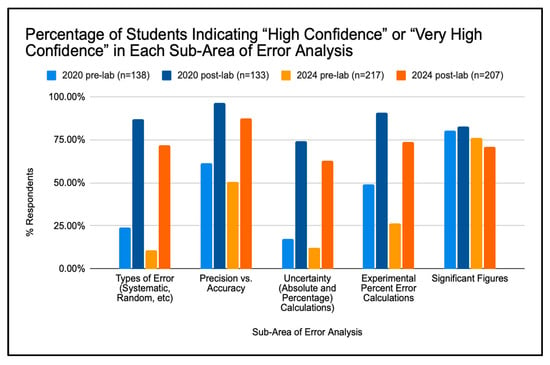

When confidence in sub-areas of error analysis was evaluated (in Spring 2020 and Spring 2024), most categories showed increased confidence following the lab. These categories included distinguishing types of error, interpreting uncertainty, identifying significant sources of procedural variability, and applying quantitative reasoning to evaluate experimental reliability. The one exception, consistently observed across semesters, was a slight decrease in confidence related to significant figures, where students’ self-reported confidence dropped slightly from pre- to post-lab assessments (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Student Confidence in Each Sub-Area of Error Analysis.

In Spring 2020, student confidence increased between the pre- and post-lab responses across all sub-areas, except significant figures, where the proportion reporting “very high confidence” decreased slightly (43.5% pre-lab to 37.5% post-lab). A similar pattern appeared in Spring 2024, with confidence increasing in nearly all categories except significant figures.

For both semesters, students’ self-reported confidence increased significantly in four of the five sub-areas following the intervention. The statistical analyses of pre- and post-lab data for five key sub-areas of error analysis in the 2020 and 2024 cohorts are given in Table 2. For instance, in Spring 2020, confidence in identifying types of error rose from a mean of 2.74 (SD = 1.01) to 4.18 (SD = 0.63), t(N1 = 138, N2 = 132) = −14.20, p < 0.001. Similarly, confidence in distinguishing precision vs. accuracy increased from 3.64 (SD = 1.11) to 4.80 (SD = 0.51), t = −11.02, p < 0.001, and confidence in calculating absolute and percent uncertainties rose from 2.41 (SD = 1.00) to 4.10 (SD = 0.80), t = −15.27, p < 0.001. These large t-values and corresponding p < 0.001 indicate highly significant learning gains.

Table 2.

The statistical analyses of pre- and post-lab data for five key sub-areas of error analysis in the 2020 and 2024 cohorts (Likert scale: 1 = lowest, 5 = highest).

In contrast, confidence in significant figures showed a modest decline—from 4.17 to 3.20 in 2020 and from 3.93 to 3.91 in 2024—indicating that greater engagement with real data prompted students to develop a more realistic appreciation of the nuanced challenges involved in applying significant figures accurately.

To examine potential year-to-year differences, a one-way ANOVA compared post-lab responses between the 2020 and 2024 cohorts (Table 3). Significant differences were found across all five items (p < 0.001). The 2020 cohort reported higher post-intervention confidence on Q1–Q4 (F = 17.93–27.37), while the 2024 cohort reported higher confidence on Q5 (F = 57.70). These findings suggest variation in student engagement and perception between pre- and post-pandemic offerings, possibly reflecting broader shifts in learning environments and student experience.

Table 3.

ANOVA results comparing 2020 and 2024 post-lab responses.

In the 2024 spring semester, learning outcomes were assessed through three questions aimed at determining whether students demonstrated an improved understanding of the fundamental error analysis topics covered. The results in Table 4 demonstrate substantial gains in understanding for two of the three targeted learning outcomes. The significant improvement occurred in uncertainty calculations, where correct responses more than doubled. The largest increase in understanding of how to properly round using significant figures—from 8.8% to 69.0%—also reflects meaningful learning gains, though this was tempered by reduced confidence in that area. Gains in distinguishing accuracy from precision were more modest but still evident.

Table 4.

Questions evaluating lab learning outcomes.

The application-based questions to measure students’ learning outcomes with the results listed in Table 2 can be found in Supplementary Materials SIV.

In the post-semester survey, free responses to open-ended questions were overwhelmingly positive. Representative comments included:

- “It was very informative in learning important topics like precision vs. accuracy.”

- “Knowing uncertainties in measurements is extremely important in labs.”

- “The short video that went with the lab was great.”

- “There was plenty of preparatory material, so I felt prepared going in.”

Beyond these general observations, students frequently noted specific learning gains. For example, one student reflected, “I enjoyed the opportunity to have hands-on experience to notice how easily data can be changed or an experiment can be done wrong if one commits the smallest of errors. It gave me an appreciation for all that researchers do to ensure that the experiments they conduct are done correctly,” highlighting an increased awareness of error propagation. Another explained, “Finding the equilibrium point between the metal and the water is quite interesting because it expands on previous theoretical knowledge of specific heat,” demonstrating a connection between laboratory practice and classroom concepts. A third remarked, “I enjoyed being able to do two different experiments and seeing how uncertainties factored in differently for the calorimeter part and for the precipitate part,” recognizing how experimental design influences the role of uncertainty.

Students also emphasized the real-world relevance of the experiments, such as one who valued “the application to real-world studies—realizing how big of a difference errors can have in experimental settings.” Finally, many highlighted the effectiveness of the pre-lab preparation, noting that the interactive, animated video helped them visualize laboratory procedures and reinforced the value of visual learning resources.

6. Discussion

Taken together, these findings indicate that the systems-thinking-based laboratory module significantly improved students’ comprehension of core concepts in error analysis, particularly those requiring quantitative reasoning and application. Among the most striking outcomes were the substantial gains in students’ ability to perform quantitative uncertainty analysis. Specifically, correct responses on targeted pre-lab questions—covering absolute uncertainty and propagation of error—averaged below 40% at baseline and rose to nearly 85% after the lab, suggesting a meaningful conceptual shift. Importantly, this pattern aligns with prior studies showing that systems-based pedagogy supports deeper conceptual understanding and transfer (Schultz et al., 2020; Reinagel & Speth, 2016 [8,9]). Our findings extend this work by demonstrating that similar benefits can be achieved in the context of hands-on laboratory instruction in introductory chemistry, an area that has been underexplored compared with lecture-based interventions.

The design of the module itself likely played a key role in these outcomes. Both parts of the lab—calorimetry and precipitation/filtration—were deliberately structured to highlight different sources of uncertainty while reinforcing overlapping sub-concepts. This mirrors York and Orgill’s framework [4], which emphasizes helping students recognize interconnections across contexts to strengthen systems-level reasoning. By encountering errors in two distinct but connected experiments, students were able to transfer principles of uncertainty analysis across systems, a hallmark of systems thinking. Feedback further suggested that the module helped students appreciate chemistry as a dynamic process in which measurement, calculation, and procedural decisions interact—a perspective that resonates with Mahaffy et al.’s call for reimagining chemistry instruction through interconnected systems rather than isolated facts [5,6,7].

Pre-laboratory scaffolding also contributed to effectiveness. The interactive videos and notebook prompts reduced procedural load, allowing students to focus on conceptual reasoning about error. Student feedback highlighted the value of animated visualizations of error propagation, consistent with prior research showing that multimedia preparation fosters connections between abstract theory and physical practice [10,11] Within the broader Systems Thinking in Chemistry Education (STICE) framework (IUPAC, 2017-010-1-050), these scaffolds represent an integration of the “Chemistry Teaching & Learning” and “Educational Research & Theories” subsystems, where pedagogical design is directly informed by cognitive and affective considerations.

Interestingly, while cognitive gains were clear, a post-lab decline in students’ confidence regarding significant figures emerged as a recurring theme. Rather than a negative outcome, this can be interpreted as evidence of metacognitive recalibration [30,31]. Students’ confrontation with authentic cases of rounding and reporting uncertainty revealed the complexity of applying rules in practice, which may have temporarily reduced confidence but ultimately deepened awareness. This outcome underscores the distinction between performance confidence and conceptual growth and points to opportunities for embedding reflective scaffolds to support metacognitive development.

Another noteworthy finding was the consistency of learning gains across semesters and instructional contexts despite variation in TA training and quiz administration. This robustness suggests that the module’s design principles—interconnected activities, scaffolded preparation, and explicit systems thinking—are transferable across diverse contexts. Such resilience reflects broader insights from the systems thinking literature, which highlights adaptability as a defining feature of systems-oriented instruction [2,6].

Beyond cognitive outcomes, affective and motivational gains were evident. Students reported greater appreciation for the real-world significance of error analysis and stronger connections between lecture concepts (e.g., specific heat, stoichiometry) and laboratory practice. These reflections align with Mahaffy’s emphasis on chemistry as a bridge between molecular processes and societal implications, suggesting that even introductory modules can foster early habits of systems-oriented thinking about the role of error in scientific reliability.

Finally, this module addresses a persistent gap in general chemistry education: the lack of early, coherent exposure to error analysis framed as a dynamic system rather than a procedural sidebar. Prior labs have emphasized accuracy and precision [13,25] but often in isolation and without attention to systemic interconnections. By embedding error analysis within an explicit systems thinking, our approach helps students see how methodological choices and measurement decisions propagate across experimental outcomes. In doing so, it responds directly to calls from Mahaffy et al. [5,6,7] and the STICE project to integrate systems thinking into foundational chemistry experiences, thereby laying the groundwork for later engagement with sustainability, complexity, and interdisciplinary problem solving.

While these findings are encouraging, several factors may limit the generalizability of our results. First, some outcomes rely on student self-reports of confidence and perceived learning gains, which can be influenced by biases such as overestimation or social desirability. Second, the study was conducted exclusively at Brown University, where small lab sections, ample instructional support, and a highly prepared student population may not reflect broader undergraduate settings. Third, although we collected data across multiple semesters and cohorts, the overall sample size remains modest relative to larger introductory chemistry courses. Finally, while the module’s core principles—embedding systems thinking, emphasizing error propagation, and connecting multi-step experiments—are broadly applicable, adaptations may be needed for institutions with larger classes, limited equipment, or fewer instructional resources. Future work could explore how these strategies can be modified to support effective implementation across diverse educational contexts.

In summary, this study demonstrates that systems-oriented lab design can produce measurable conceptual gains, foster metacognitive awareness, and enhance student engagement even in large introductory courses. By aligning with the emerging systems thinking literature and extending it into hands-on laboratory practice, our module represents a model for integrating error analysis, systems thinking, and sustainability in a coherent, scalable way. Future work will examine how such early interventions influence students’ long-term development as scientific thinkers and their ability to connect chemistry to broader societal systems.

7. Conclusions

The findings of this study strongly support the effectiveness of a systems-thinking-based laboratory module designed to teach foundational concepts in error analysis during the early weeks of an introductory chemistry course. By strategically integrating multiple experimental techniques—including calorimetry, precipitation reactions, and vacuum filtration—into a cohesive learning experience, the lab fosters both procedural competence and conceptual understanding.

Quantitative data showed substantial learning gains, particularly in students’ ability to perform uncertainty calculations and distinguish between accuracy and precision. Although confidence in applying significant figures slightly decreased, this likely reflects increased cognitive engagement with the material rather than a loss of understanding.

The use of multimedia pre-lab materials, including student-developed animated and interactive videos, proved highly effective in preparing students for hands-on work and reinforcing key concepts. These tools also addressed affective learning goals by reducing anxiety and improving students’ sense of readiness and engagement.

The lab’s design supports broad accessibility, aligning with current goals in inclusive STEM education by using affordable materials, reducing cognitive overload, and embedding sustainability principles throughout. The module is adaptable to a variety of instructional settings and can serve as a model for other institutions seeking to modernize introductory laboratory curricula with interdisciplinary thinking and real-world application.

Future directions include enhancing in-lab instruction on significant figures, refining assessment tools to reduce variability across semesters, and exploring the long-term impacts of early systems-thinking instruction on students’ performance in more advanced laboratory environments. The success of this module affirms the value of integrating systems thinking into foundational chemistry education and underscores its potential for wider adoption.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/laboratories2040022/s1, Content includes the lab manual, two pre-lab videos, and questionnaire results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and L.-Q.W.; methodology, A.H., E.E., T.L. and L.-Q.W.; software, A.H., E.E. and L.-Q.W.; validation, A.H., E.E., T.L. and L.-Q.W.; formal analysis, A.H. and L.-Q.W.; investigation, A.H., T.L. and L.-Q.W.; resources, L.-Q.W.; data curation, A.H. and L.-Q.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H., E.E., T.L. and L.-Q.W.; writing—A.H., E.E. and L.-Q.W.; visualization, A.H., E.E. and L.-Q.W.; supervision, L.-Q.W.; project administration, L.-Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laura Perlmutter, Noah Bronowich, Matthew Vigilante, Jake Ruggiero, and Habesha Petros for making the interactive and animated lab video. The authors acknowledge the support from the Brown University UTRA program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Simonsmeier, B.A.; Flaig, M.; Deiglmayr, A.; Schalk, L.; Schneider, M. Domain-specific prior knowledge and learning: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 57, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaraf, O.B.; Orion, N. Development of System Thinking Skills in the Context of Earth System Education. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2005, 42, 518–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, S.; Lavi, R.; Dori, Y.J.; Orgill, M. Applications of Systems Thinking in STEM Education. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2742–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, S.; Orgill, M. ChEMIST Table: A tool for designing or modifying instruction for systems thinking in chemistry education. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 2114–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffy, P.G.; Matlin, S.A.; Holme, T.A.; MacKellar, J. Systems thinking for education about the molecular basis of sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffy, P.G.; Matlin, S.A.; Whalen, J.M.; Holme, T.A. Integrating the Molecular Basis of Sustainability into General Chemistry through Systems Thinking. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2730–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffy, P.G.; Ho, F.M.; Haack, J.A.; Brush, E.J. Can Chemistry Be a Central Science without Systems Thinking? J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2679–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.; Chan, D.; Eaton, A.C.; Ferguson, J.P.; Houghton, R.; Ramdzan, A.; Taylor, O.; Vu, H.H.; Delaney, S. Using Systems Maps to Visualize Chemistry Processes: Practitioner and Student Insights. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinagel, A.; Bray Speth, E. Beyond the central dogma: Model-based learning of regulation of gene expression. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, ar4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F.M. Applying systems thinking in a physical chemistry laboratory setting to support deeper learning. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 2851–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, A.; Stanford, C.; Towns, M.H. Characterizing assessments for systems thinking in chemistry education. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2023, 24, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynders, M.; Pilcher, L.; Potgieter, M. Development of Systems Thinking in a Large First-Year Chemistry Course Using a Group Activity on Detergents. J. Chem. Educ. 2025, 102, 1352–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treptow, R.S. Precision and Accuracy in Measurements: A Tale of Four Graduated Cylinders. J. Chem. Educ. 1998, 75, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J.; Quintus, F. Theoretical error in acid-base titrations. J. Chem. Educ. 1966, 43, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvil, B.; Reid, S.R.; Harris, W.E. Sampling error in a particulate mixture: An analytical chemistry experiment. J. Chem. Educ. 1980, 57, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilliman, S.G. An Inquiry-Based Density Laboratory for Teaching Experimental Error. J. Chem. Educ. 2012, 89, 1305–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.D. Which Method Is Most Precise; Which Is Most Accurate? J. Chem. Educ. 2007, 84, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bularzik, J. The Penny Experiment Revisited: An Illustration of Significant Figures, Accuracy, Precision, and Data Analysis. J. Chem. Educ. 2007, 84, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.A.; Nicholson, C.P. Hydration of Decorative Beads: An Exercise in Measurement, Calculations, and Graphical Analysis. J. Chem. Educ. 2017, 94, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, B. Simple classroom experiment on uncertainty of measurement. J. Chem. Educ. 1977, 54, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgstahler, A.W.; Bricker, C.E. Measuring the heat of sublimation of dry ice with a polystyrene foam cup calorimeter. J. Chem. Educ. 1991, 68, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeh, L.N.; Orbell, J.D.; Bigger, S.W. Simple Heat Flow Measurements: A Closer Look at Polystyrene Cup Calorimeters. J. Chem. Educ. 1994, 71, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.; Moran, M.J. Improved Method for Determining the Heat Capacity of Metals. J. Chem. Educ. 2014, 91, 2155–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, D.G. The Heat Is On: An Inquiry-Based Investigation for Specific Heat. J. Chem. Educ. 2011, 88, 1558–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, K.L.; Sevian, H. Teaching Lab Report Writing through Inquiry: A Green Chemistry Stoichiometry Experiment for General Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedens, W.J.; Yperman, J.; Mullens, J.; Van Poucke, L.C.; Pauwels, E.J. Statistical analysis of errors: A practical approach for an undergraduate chemistry lab: Part 2. Some worked examples. J. Chem. Educ. 1993, 70, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.T. Statistical evaluation of acid/base indicators: A first experiment for the quantitative analysis laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 1991, 68, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmiston, P.L.; Williams, T.R. An Analytical Laboratory Experiment in Error Analysis: Repeated Determination of Glucose Using Commercial Glucometers. J. Chem. Educ. 2000, 77, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzsieder, J.C. Statistical Analysis Experiment for the Freshman Chemistry Lab. J. Chem. Educ. 1995, 72, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J.H. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G.; Dennison, R.S. Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 19, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).