Abstract

Additive manufacturing (AM), commonly known as 3D printing, is revolutionizing manufacturing, medicine, and engineering. This perspective explores recent breakthroughs that position AM as a disruptive technology. Innovations like volumetric additive manufacturing (VAM) enable rapid, high-resolution, layer-free fabrication, overcoming limitations of traditional methods. Multi-material printing allows the integration of diverse functionalities—fluid channels, structural elements, and possibly functional electronic circuits—within a single device. Advances in material science, such as biocompatible polymers, ceramics, and transparent silica glass, expand the applicability of AM across healthcare, aerospace, and environmental sectors. Emerging applications include custom implants, microfluidic devices, various sensors, and optoelectronics. Despite its potential, challenges such as scalability, material diversity, and process optimization remain active and critical research areas. Addressing these gaps through interdisciplinary collaboration over the coming decade will solidify AM’s transformative role in reshaping production and fostering innovation across many industries.

1. Introduction

Disruptive technologies catalyze transformative change across industries, reshaping social norms and economic reality. From the personal automobile revolutionizing our daily experiences to the internet reshaping communication and commerce, disruptive technologies redefine what is possible. Additive manufacturing, commonly known as 3D printing, is currently emerging as a similarly disruptive force poised to revolutionize manufacturing, medicine, education, and beyond [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

Additive manufacturing represents a fundamental shift in production philosophy. Traditional manufacturing relies on subtractive methods, carving out materials such as metal or wood to create components. However, 3D printing builds objects in three dimensions, enabling unparalleled design freedom, material efficiency, and customization. These capabilities are allowing designs that were inconceivable through conventional manufacturing.

Several recent advances underscore 3D printing’s disruptive potential. In principle, multi-material printing allows the creation of devices integrating diverse functions (e.g., fluid channels, electrodes, and structural components) within a single manufacturing process. This innovation mirrors the transformative impact of integrated circuits in electronics, where miniaturization and multi-functionality catalyzed exponential growth in the field since the mid 20th century [8]. The rapid pace of advancements has necessitated organizations such as ASTM and ISO to develop standards regarding the nomenclature, manufacturing processes, and validation of various additive manufacturing technologies [9]. Table 1 summarizes these recent standards.

Table 1.

ASTM and ISO standards for additive manufacturing.

Additionally, advances in printing hardware such as volumetric additive manufacturing are enabling the fabrication of entire 3D structures in seconds rather than hours. This mirrors the transition from analog to digital photography, where a leap in speed and convenience made traditional methods obsolete.

The ability to rapidly tailor designs to individual needs also positions additive manufacturing as a disruptive force in healthcare [10,11,12,13]. Custom implants, prosthetics, and even pharmaceuticals can now be produced with unprecedented precision, echoing the personalized revolutions seen in genomics and precision medicine.

As with any disruptive technology, challenges remain. Scalability, material diversity, and economic accessibility continue to be areas requiring innovation and refinement. However, the trajectory of additive manufacturing is clear—it is ushering in a new era of possibility, where the boundaries of manufacturing, engineering, and creativity will be redefined.

2. Volumetric Additive Manufacturing (VAM)

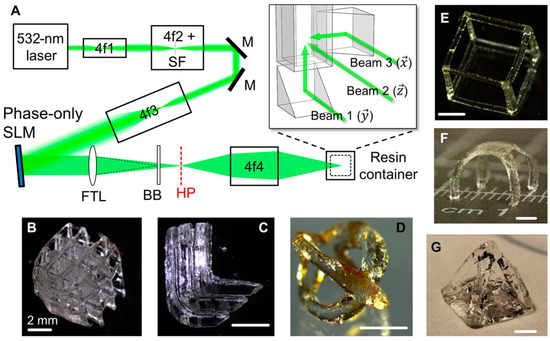

VAM fabricates parts by differentially delivering energy to all points (voxels) in a volume of a photopolymer which causes one or more chemical reactions to generate a solid physical part [14]. Initial attempts at VAM by Shusteff et al. utilized low-molecular-weight PEGDA (poly(ethylene glycol)diacrylate), with a photochemical initiator called Irgacure 784 (0.05 to 0.2% (w/w)) which was illuminated by three separate laser beams (532 nm wavelength) aligned in each spatial dimension [15]. This approach is depicted in Figure 1. The authors found that photopolymerization initiation rate was a non-linear function of light power density. Consequently, by carefully tuning the intensity of each laser beam and illumination time, the authors achieved the ability to polymerize only the volume element where all three laser beams coincide. To print an object, a digital 3D model is converted to an energy deposition distribution field (EDDF)—the spatial distribution of light energy deposited within the print volume to achieve the desired geometry. By scanning the laser’s spatial location according to the EDDF the desired part is printed. Unlike layer-by-layer printing methods, VAM eliminates poor surface quality and mechanical property differences between print axes. VAM also enables the creation of any geometry without the need for underlying support material. Most importantly, VAM features very fast print times since the laser beams can be scanned rapidly, with intricate designs being printed in just seconds.

Figure 1.

(A) Initial VAM approach demonstrated by Shusteff et al. employed convergence of three laser beams for printing. (B–G) Structures printed by this approach. Figure reproduced from Shusteff et al. [15] with permission.

A major step forward in print hardware occurred in 2019 when Kelly et al. reported tomographic VAM [16,17] as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(A) Concept of tomographic VAM. (B) Experimental apparatus. (C) Print in progress. Object forming within photopolymer. (D–G) Structures printed by this approach. Figure reproduced from Kelly et al. [16,17] with permission.

In this approach, a DLP projector illuminates a rotating volume of photosensitive material. The projector casts a series of 2D images (light patterns) of the desired object into the resin. As the print volume rotates, the image projected presents a new spatial perspective of the object. Summing to the sequence of images results in a 3D light-energy dose which causes photopolymerization to occur in a volume defined by the desired object’s shape. Even this initial demonstration of the technology yielded impressive spatial resolution on the order of 300 microns and print times of only 30–120 s for objects measured in centimeters. It should be noted that more recently Loterie et al. have demonstrated superior spatial resolution of devices utilizing a low-etendue illumination system [18]. Tomographic VAM can also easily print over or embed an existing object within the printed device, allowing options for multi-material fabrication.

3. Print Materials

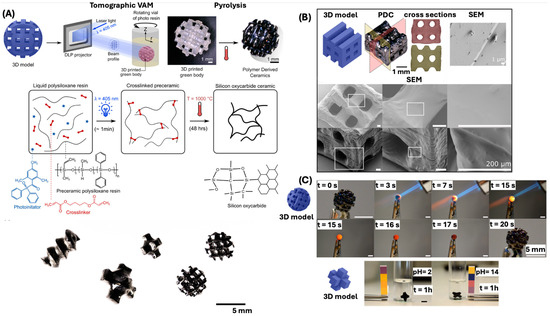

At this point, the reader may infer that only very specific photopolymers may be printed using VAM. Certainly, presence of light-activated polymerization is indeed crucial and research and development of novel resins has been previously reviewed [14,19]. One print material of commercial interest is ceramics because they are highly chemically, thermally, electrically, and mechanically resistant. One remarkably creative contribution was offered by Kollep et al. who used preceramic polymers (PCPs) in liquid form and VAM to print a desired geometry as described in Figure 3 [20]. The ‘preceramic’ photocurable resin was prepared by combining a commercial polysiloxane (SPR 684, Starfire Systems, Schenectady, NY, USA) with 1,4-butanediol diacrylate (BDDA) as a cross-linker, and diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide (TPO) as a photoinitiator. VAM effectively creates the desired shape and crosslinks the photopolymer. Then, a pyrolysis procedure converts the object into a ceramic. The inorganic silicon oxycarbide material, with Si-C and Si-O bonds, forms after thermal decomposition of the photopolymer during pyrolysis. The heating protocol used ramps the device temperature to 375 °C prior to holding for 1 h. Then, a heating ramp up to 1000 °C occurs and devices are held at the peak temperature for 48 h to complete the ceramic formation. While distortion and/or shrinkage (~30%) of parts is/are observed during the process, the resulting material is highly resistant to chemical attack, corrosion, and extremes of temperature.

Figure 3.

(A) Tomographic VAM workflow for printing ceramic parts. (B) A 3D model and actual printed parts resulting. While distortion of features is observed, objects on the scale of a hundred micrometers are possible. (C) Ceramic objects created were subjected to extremes of heat and pH without effect. Figure reproduced from Kollep et al. [20] with permission.

A second recent development is the printing of transparent glass microstructures by VAM [21]. The authors used an approach similar to the previous work but created a silica glass nanocomposite (Glassomer µSL v2.0) with a solid loading of 35 vol% silica in liquid monomer binder consisting of a mixture of trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) and hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA). To the nanocomposite was added 0.117 wt% camphorquinone (CQ) and equal-mass ethyl 4-(dimethylamino)benzoate (EDAB) to make a 0.01 M photoinitiator concentration. The desired device is then printed using VAM to achieve desired shape and dimension. After printing, the device was initially heated following a ‘dibinding protocol’. This involved ramping the temperature to 150 C for 2 h, prior to increasing to a final temperature of 600 C over the next 8 h. Then, a sintering phase at 1300 C was conducted to thermally sinter the glass nanoparticles together and achieve the device’s final form. While device shrinkage of 25–30% was again observed, the resultant structures which were achieved are remarkable. Devices with transparency similar to fused silica could be achieved with minor dimensional features on the order of 50 micrometers (see Figure 4). The authors used the method to fabricate three-dimensional microfluidic devices with internal channels of 150 μm, micro-optical elements with a surface roughness of 6 nanometers, and complex-geometry, high-strength truss/lattice structures with feature sizes of 50 μm. The article offers a remarkable glimpse into the future of this exciting technology while printing devices in a material which is low-cost, familiar, and serves as the basis for many existing laboratory technologies.

Figure 4.

(Top) Glass microstructure printed with tomographic VAM. Scale bar is 1 mm. Figure reproduced from Toombs et al. [21] with permission. (Bottom) SEM and fluorescent images of printed QD structures of various compositions. Figure reproduced from Li et al. [22] with permission.

In 2022–2023, Liu et al. and Li et al. reported the 3D printing of inorganic materials and quantum dots [22,23], the latter work using 2-photon absorption to photo-generate nitrene radicals at both ‘ends’ of a molecule yielding a reactive bidentate cross-linking agent which ultimately covalently binds nanoparticles together. While not a demonstration of VAM, the published results highlight the ability to craft arbitrary complex objects with sub-micrometer control. The work also demonstrates features crafted from multiple different quantum dot materials and even creates nanostructures with mixed materials. The precise patterning of functional semiconductors demonstrated in this work has nearly limitless applications for microelectronics and sensing. However, the approach could be enhanced significantly if electrically conductive crosslinkers could be used. This goal may represent the next step for this research group and if achieved would usher in a wide array of applications of the technology in microelectronics manufacturing.

An additional major area of focus is the printing of biomaterials or biocompatible materials. One application of interest is the rapid printing of bespoke medical implants for personalized medicine. Kermavnar et al. reported that the most common uses of 3D printing to manufacture medical devices were in the fields of orthopedics (37%) and orthopedic oncology (33%), maxillofacial surgery (7%), and neurosurgery (4%) [24]. Guttridge et al. have recently published a comprehensive review of photosensitive, biocompatible materials for the printing of medical devices and found 99 rigid materials and 31 flexible materials available on the market for these purposes [25].

An additional application of interest is using a 3D printer to produce a porous scaffold of an organ to potentially allow organ creation and transplant. In recent years, investigators have utilized natural polymers such as collagen, gelatin, alginate, fibrinogen, hyaluronic acid, chitosan, and agarose to print scaffolds onto which cells and tissues may grow [26]. Such approaches clearly demonstrate innovation and organ mimetics can be used for testing drugs in lieu of animal experiments. Continued development of print technologies to allow for vascular networks in printed organs to provide water, gas, and nutrients for cells is necessary to advance the technology further [27].

4. Future Directions and Research Needs

The continued evolution of additive manufacturing depends on breakthroughs in materials science and print hardware. The continued development of multi-material printing capabilities, allowing for seamless integration of conductors, insulators, and structural and functional elements, is essential for moving the technology forward. In addition, there is a growing need for additional bio-compatible and high-performance materials, such as ceramics and composites, to expand the applicability across industries like healthcare, aerospace, and environmental engineering.

Of specific need is the demonstration of the ability to print functional electronic circuits and integrate these onto devices constructed from glass or ceramics. Engineering the print hardware needed and developing ‘binders’ which can successfully bond vastly different materials will be crucial to move forward. Nonetheless, printing micrometer-sized features has already been demonstrated, allowing the very real possibility that portable or even implantable sensors can be developed within the coming decade provided functional electronics may be printed on devices.

Equally critical are advancements in process optimization. Achieving scalability without compromising quality will present a key manufacturing challenge, as devices move from the laboratory to production lines. Innovations like volumetric additive manufacturing offer promising solutions by dramatically reducing print times while maintaining high resolution. However, it is not yet clear whether reproduction of a singular device can achieve the precision and reproducibility needed to meet rigid manufacturing specifications. On the hardware side, hybrid systems combining both additive and subtractive processes may tackle complex geometries, facilitate multi-material prints, and/or improve surface finishes.

5. Conclusions

Additive manufacturing stands as a transformative force in modern industry, offering unprecedented opportunities for innovation across diverse fields. As breakthroughs in materials science, print hardware, and process optimization continue to address current limitations, the potential for 3D printing to revolutionize production, healthcare, and engineering becomes increasingly evident. Clearly, there exists plenty of room for collaboration among scientists, engineers, and leading manufacturers to overcome challenges such as scalability, efficiency, cost basis, and material versatility. By building on its current trajectory, additive manufacturing will not only redefine how we create but also expand the horizons of what is possible in a rapidly changing technological landscape.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VAM | volumetric additive manufacturing |

| QD | quantum dot |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| DLP | digital light processing |

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| PEGDA | poly(ethylene glycol)diacrylate |

| EDDF | energy deposition distribution field |

| PCPs | preceramic polymers |

| BDDA | 1,4-butanediol diacrylate |

| TPO | diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide |

| TMPTA | trimethylolpropane triacrylate |

| HEMA | hydroxyethylmethacrylate |

| CQ | camphorquinone |

| EDAB | ethyl 4-(dimethylamino)benzoate |

References

- Barreto, J.E.F.; Kubrusly, B.S.; Lemos Filho, C.N.R.; Silva, R.S.; de Osterno Façanha, S.; dos Santos, J.C.C.; Cerqueira, G.S. 3D printing as a tool in anatomy teaching. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2022, 10, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, A.; Erdogan, I. Use of 3D Printers for Teacher Training and Sample Activities. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2021, 17, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, C.; Meier, M. 3D Printing as an Element of Teaching—Perceptions and Perspectives of Teachers at German Schools. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1233337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Minshall, T. Invited Review Article: Where and How 3D Printing Is Used in Teaching and Education. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 25, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, G.; Vasudev, H.; Bhuddhi, D. Additive Manufacturing: Expanding 3D Printing Horizon in Industry 4.0. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 17, 2221–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Miller, J.; Vezza, J.; Mayster, M.; Raffay, M.; Justice, Q.; Al Tamimi, Z.; Hansotte, G.; Sunkara, L.D.; Bernat, J. Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Zhang, Q.; Thompson, J.E. Designing, Constructing, and Using an Inexpensive Electronic Buret. J. Chem. Educ. 2014, 92, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalise, G. Milestones in Microelectronics. Jpn. Spotlight 2008, 25–27. Available online: https://www.jef.or.jp/journal/pdf/161th_cover07.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- ISO/TC 261-Additive Manufacturing. Available online: https://www.iso.org/committee/629086/x/catalogue/p/1/u/0/w/0/d/0 (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Shine, K.M.; Schlegel, L.; Ho, M.; Boyd, K.; Pugliese, R. From the Ground up: Understanding the Developing Infrastructure and Resources of 3D Printing Facilities in Hospital-Based Settings. 3D Print. Med. 2022, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diment, L.E.; Thompson, M.S.; Bergmann, J.H.M. Clinical Efficacy and Effectiveness of 3D Printing: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, S.; Frisch, P.; Platzman, A.; Booth, P. 3D Printing in a Hospital: Centralized Clinical Implementation and Applications for Comprehensive Care. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231221900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, P.; Victor, J.; Gemmel, P.; Annemans, L. 3D-Printing Techniques in a Medical Setting: A Systematic Literature Review. Biomed. Eng. Online 2016, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, D.J.; Doeven, E.H.; Sutti, A.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Adams, S.D. Volumetric Additive Manufacturing: A New Frontier in Layer-Less 3D Printing. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 84, 104094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shusteff, M.; Browar, A.E.M.; Kelly, B.E.; Henriksson, J.; Weisgraber, T.H.; Panas, R.M.; Fang, N.X.; Spadaccini, C.M. One-Step Volumetric Additive Manufacturing of Complex Polymer Structures. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, eaao5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.E.; Bhattacharya, I.; Heidari, H.; Shusteff, M.; Spadaccini, C.M.; Taylor, H.K. Volumetric Additive Manufacturing via Tomographic Reconstruction. Science 2019, 363, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, I.; Toombs, J.; Taylor, H. High Fidelity Volumetric Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loterie, D.; Delrot, P.; Moser, C. High-Resolution Tomographic Volumetric Additive Manufacturing. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrid-Wolff, J.; Toombs, J.; Rizzo, R.; Bernal, P.N.; Porcincula, D.; Walton, R.; Wang, B.; Kotz-Helmer, F.; Yang, Y.; Kaplan, D.; et al. A Review of Materials Used in Tomographic Volumetric Additive Manufacturing. MRS Commun. 2023, 13, 764–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollep, M.; Konstantinou, G.; Madrid-Wolff, J.; Boniface, A.; Hagelüken, L.; Sasikumar, P.V.W.; Blugan, G.; Delrot, P.; Loterie, D.; Brugger, J.; et al. Tomographic Volumetric Additive Manufacturing of Silicon Oxycarbide Ceramics. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24, 2101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toombs, J.T.; Luitz, M.; Cook, C.C.; Jenne, S.; Li, C.C.; Rapp, B.E.; Kotz-Helmer, F.; Taylor, H.K. Volumetric Additive Manufacturing of Silica Glass with Microscale Computed Axial Lithography. Science 2022, 376, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, S.F.; Liu, W.; Hou, Z.W.; Jiang, J.; Fu, Z.; Wang, S.; Si, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhou, H.; et al. 3D Printing of Inorganic Nanomaterials by Photochemically Bonding Colloidal Nanocrystals. Science 2023, 381, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.F.; Hou, Z.W.; Lin, L.; Li, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.Z.; Zhang, H.; Fang, H.H.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.B. 3D Nanoprinting of Semiconductor Quantum Dots by Photoexcitation-Induced Chemical Bonding. Science 2022, 377, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kermavnar, T.; Shannon, A.; O’Sullivan, K.J.; McCarthy, C.; Dunne, C.P.; O’Sullivan, L.W. Three-Dimensional Printing of Medical Devices Used Directly to Treat Patients: A Systematic Review. 3D Print Addit. Manuf. 2021, 8, 366–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttridge, C.; Shannon, A.; O’Sullivan, A.; O’Sullivan, K.J.; O’Sullivan, L.W. Biocompatible 3D Printing Resins for Medical Applications: A Review of Marketed Intended Use, Biocompatibility Certification, and Post-Processing Guidance. Ann. 3D Print. Med. 2022, 5, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, Q.; Liu, C.; Ao, Q.; Tian, X.; Fan, J.; Tong, H.; Wang, X. Natural Polymers for Organ 3D Bioprinting. Polymers 2018, 10, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wen, L.; Wang, X. Progress of 3D Bioprinting in Organ Manufacturing. Polymers 2021, 13, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).