Abstract

Trust in financial institutions hinges on the ability to prove solvency, yet recent crises have exposed the limits of audits and opaque governance. We introduce a practical protocol that enables crypto-exchanges and other financial actors to demonstrate real-time solvency without continuous third-party oversight, while preserving transparency and regulatory alignment. Complemented by a Particles model that fragments transactions to protect privacy and enhance liquidity, this framework integrates solvency, privacy, and governance into a unified standard. We argue that it represents a potential revolution in the financial industry.

1. Introduction

Recent years have witnessed a series of high-profile solvency crises within the cryptocurrency and traditional financial sectors, eroding public trust and highlighting the critical need for enhanced transparency and accountability. The collapse of FTX, a bankrupt crypto-exchange, where a significant portion of customer deposits were reportedly diverted to Alameda Research, exposed the dangers of opaque financial practices and inadequate oversight. Similarly, the challenges faced by Circle, with a substantial USD 3.3 billion held in the vulnerable SVB account, underscore the systemic risks that can impact even seemingly stable entities. Furthermore, the insolvency of Three Arrows Capital (3AC) following the sharp depreciation of Bitcoin in 2021 serves as a stark reminder of the volatile nature of cryptocurrency markets and the importance of robust risk management strategies. These events collectively raise a fundamental question: how can blockchain technology, with its inherent transparency and immutability, be effectively leveraged to prevent such solvency issues, restore confidence in financial institutions, and mitigate the systemic risks that threaten the stability of the entire ecosystem?

In response to these challenges, the concept of proof of solvency has emerged as a critical area of focus. Unlike traditional systems that rely on trust and periodic audits, proof of solvency seeks to provide verifiable and continuous assurance that an institution possesses sufficient assets to meet its liabilities at any given time. The core premise of proof of solvency lies in establishing a transparent and auditable framework where an institution can cryptographically demonstrate its solvency to stakeholders, thereby fostering trust and reducing the potential for fraudulent or irresponsible financial practices, and in a 24/7 live environment constituting the blockchain world. Achieving this requires addressing two fundamental questions: How can an institution convincingly prove its assets? And how can it transparently demonstrate its liabilities? The subsequent sections of this paper delve into these questions, exploring novel methodologies and architectural considerations for implementing robust and privacy-preserving proof-of-solvency solutions within blockchain-based financial systems.

Beyond its immediate applications in mitigating cryptocurrency-related risks, the proof-of-solvency framework represents a profound revolution in risk management principles, offering a blueprint for increased transparency and accountability across diverse financial sectors. This is not merely an incremental improvement but rather an invitation to reimagine the very foundations upon which corporate relationships are built within financial institutions. By shifting from a reliance on opaque, trust-based systems to verifiable, cryptographically backed solvency assurances, we can empower stakeholders with unprecedented insight into the financial health of organizations, fostering a more responsible and resilient global financial ecosystem. As thoroughly depicted in this paper, the implications extend far beyond cryptocurrency exchanges, offering a pathway toward systemic reforms that promote stability, reduce the potential for fraud, and ultimately reshape the landscape of risk management.

More specifically, proof of solvency hinges on two distinct proofs. The first concerns liabilities, wherein the institution (henceforth referred to as the exchange without loss of generality) demonstrates its unwavering commitment to honoring obligations to both customers and external liquidity providers. The second focuses on reserves or assets, where the exchange rigorously establishes that its holdings are sufficient to fully cover these liabilities.

Solvency has been a subject of extensive study within the realm of cryptocurrencies [1,2,3,4,5,6] (with mathematical blockchain properties providing a foundational starting point for solvency research, as noted in [7]). Existing proposals address proof-of-solvency within both audited environments (e.g., [2]) and unaudited scenarios (e.g., [3]). For early-stage ventures, a comprehensive audit may demand resources disproportionate to their means. While regular audits bolster the credibility of solvency verification, their associated costs can significantly diminish assets available for other crucial operations. Nonetheless, a third party will systematically be necessary for the control of the implementation (a state could represent this third party). The non-audited approaches to solvency proof, proposed to date, tend to be cryptographically driven (e.g., [3]). However, these approaches present challenges: (i) they primarily guard against the under-claiming of liabilities, offering limited protection against over-claiming, and (ii) they often presume access to public keys associated with Unspent Transaction Outputs (UTXOs) (or an address which contains bitcoins that have not been spent yet). A significant drawback lies in the susceptibility to inflating liabilities by strategically masking assets, potentially for tax optimization purposes. Furthermore, the cryptographic protocols underpinning asset verification are predicated on assumptions that may not hold true, e.g., the exchange might not possess the private key associated with the UTXOs, or it might decline to generate one upon request. The wealth of technical literature in this domain, while valuable, often lacks the practical considerations essential for real-world implementation, a gap this paper aims to bridge.

Therefore, existing research frequently overlooks the practical aspects of proof of solvency. Certain proposed solutions prove infeasible in practice, while others suffer from inherent limitations. Within the context of exchanges (typically Centralized Exchanges, or CEXs), prevailing implementations often fail to capture the nuanced dynamics and interdependencies between various counterparties. A truly effective proof-of-solvency mechanism must account for the full spectrum of relationships involved.

Beyond the establishment of a robust solvency proof, a further challenge arises: the potential for privacy breaches through UTXO tracing on the blockchain. The immutable ledger inherent to blockchain technology exposes user transaction data, creating opportunities for privacy attacks. This issue persists even in multi-transaction environments [8]. Moreover, statistical techniques, such as clustering spent and unspent outputs, have proven effective in unraveling the pseudonymity afforded by blockchains [9]. To counter these privacy risks, we introduce a method designed to reduce the probability of an attacker successfully linking address clusters to specific users.

This document aims to reconcile the goal of providing proof of solvency within a crypto-exchange-like company (comprising customers and external exchanges, i.e., liquidity providers). This approach, however, possesses the flexibility to be broadened to encompass any financial institution, or even states, contingent upon the presence of other stablecoin exchanges that serve as a bridge between the tokenized ecosystem and the traditional fiat currency system, and to which a standard audit cannot be avoided. Our solution will rigorously distinguish between assets and liabilities, offering a means to verify crypto assets recorded on a public blockchain, alongside fiat currencies (GBP, EUR, USD). The ultimate objective is to obviate the need for costly third-party audits by achieving an appropriate level of public disclosure. While implementing our solution will entail some expense, regular monitoring of its operation—particularly in its initial stages—remains essential. Furthermore, we address the privacy and security concerns stemming from public disclosure. Our proposal seeks to minimize the risk of user identification to near-negligible levels by employing multiple inputs and outputs, thereby increasing entropy, a privacy metric that we leverage to develop a fair price for typical transactions (for a blockchain introduction of the entropy of privacy, see [7]) [10,11,12]. Privacy has been studied in the literature [13,14,15,16,17,18].

In addition, ref. [19] addresses a critical challenge in the digital age: protecting intellectual property rights while preserving privacy. Their Ethereum-based system, employing ECC encryption and zk-SNARKs, mirrors our concern for balancing transparency with user privacy. Just as they leverage blockchain’s immutability for copyright authentication, our work utilizes blockchain for verifiable solvency, striving for a similarly robust and privacy-respecting framework in the financial domain. Ref. [20] deals with Sybil attacks in vehicular networks using a blockchain-based Proof-of-Location (PoL) system with privacy preservation. Similar to our approach in the financial domain, their work leverages blockchain’s immutability for verifiable data (location information) and implements mechanisms to protect user privacy. The challenges posed by Sybil attacks, where multiple fake identities are created, mirror the risks of over-claiming liabilities in our context, highlighting the broader need for robust verification methods and privacy-preserving techniques within decentralized systems. Ref. [21] tackles the challenge of data availability attacks on blockchains, a critical issue that limits their applicability. Their solution, combining coding theory with a zero-knowledge accumulator, shares a common goal with our work: ensuring data integrity and security while preserving privacy. Just as they aim to prevent fraudulent information generation by protecting the accumulation set, we strive to prevent the inflation of liabilities through privacy-preserving mechanisms in our proof-of-solvency framework. Finally, ref. [22] proposes a privacy-protection method for blockchain transactions using lightweight homomorphic encryption and zero-knowledge proofs. Like our work, their approach prioritizes data security and user privacy. By using the Paillier algorithm and zero-knowledge proofs to verify data legitimacy, they create a system where transaction details are encrypted, ensuring both security and efficiency, and this objective is in line with the privacy goals of our model.

In this paper, we propose a fundamental approach to build an order book respecting users’ privacy.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a solvency protocol tailored for cryptocurrencies, while Section 3 details a corresponding protocol applicable to fiat currencies through tokenization. These sections form the core of our proposed framework. Section 4 outlines recommendations for public disclosure that enhance the implementation of the solvency protocol. Subsequently, Section 5 introduces the Particles model, with Section 6 providing the mathematical underpinnings. Together, these sections represent the second key element of our approach. Finally, Section 7 develops a methodology for deriving a fair price based on an optimal calibration of trading costs, while Section 8 shows empirical evidence to support the proposed proof-of-solvency protocol and the Particles model. We conclude in Section 9.

Throughout this paper, denotes the floor function, represents the ceiling function, and defines the integer interval for integers . All discussions are framed within the context of a specified exchange. Where ambiguity arises between different exchanges, we denote the exchange of interest as ‘E’.

Key contributions of the paper

- Practical Proof-of-Solvency Framework: A comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for cryptocurrency exchanges to demonstrate solvency or insolvency.

- Clear Distinction Between Assets and Liabilities: A methodology for rigorous separation and independent verification of assets and liabilities.

- Adaptation to Fiat Currencies: A practical approach to proving solvency for fiat holdings through tokenization.

- Guidance on Public Disclosure: Recommendations for transparent information disclosure that eliminates the need for costly third-party audits.

- Privacy Enhancement via Particles Model: A novel ‘Particles Model’ to mitigate privacy risks associated with UTXO tracing, improving user anonymity.

- Fair Price Derivation: A methodology for determining a fair transaction price through optimal calibration, balancing exchange profitability and user costs.

- Comprehensive Consideration of Counterparties: Accounting for the complexities of relationships between exchanges, customers, and external liquidity providers.

2. Proof-of-Solvency Protocol for Cryptocurrencies

2.1. Overall Protocol

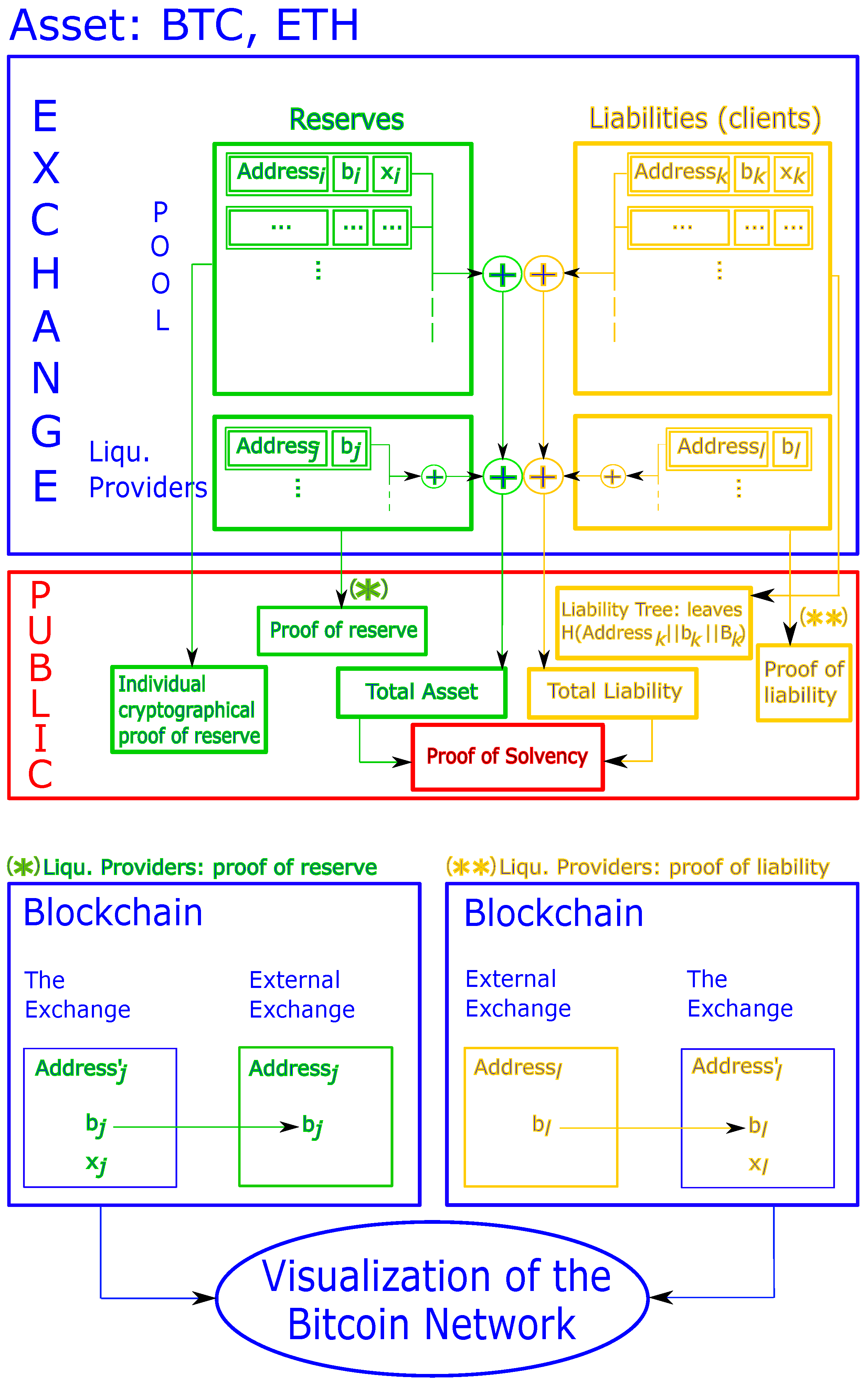

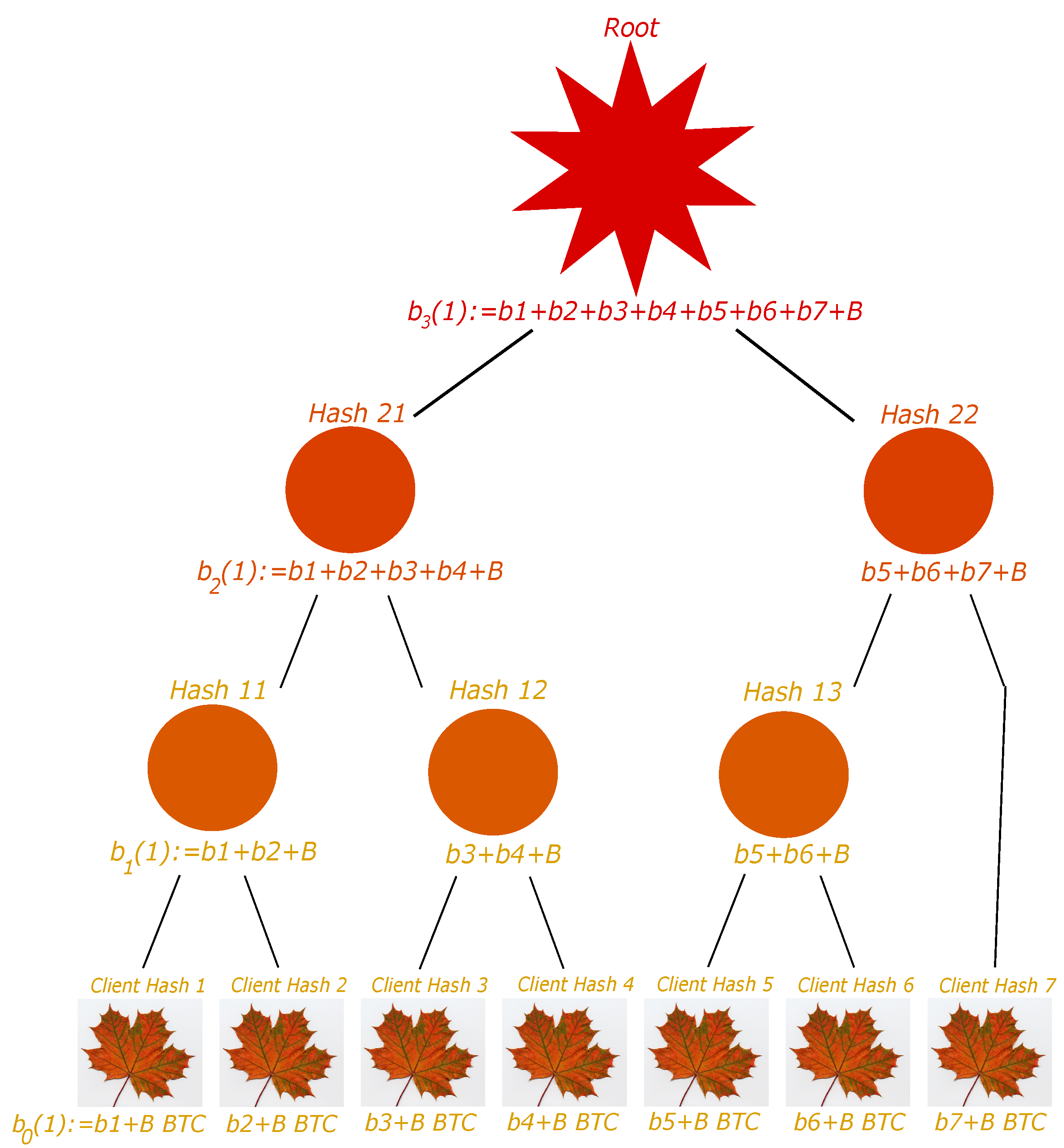

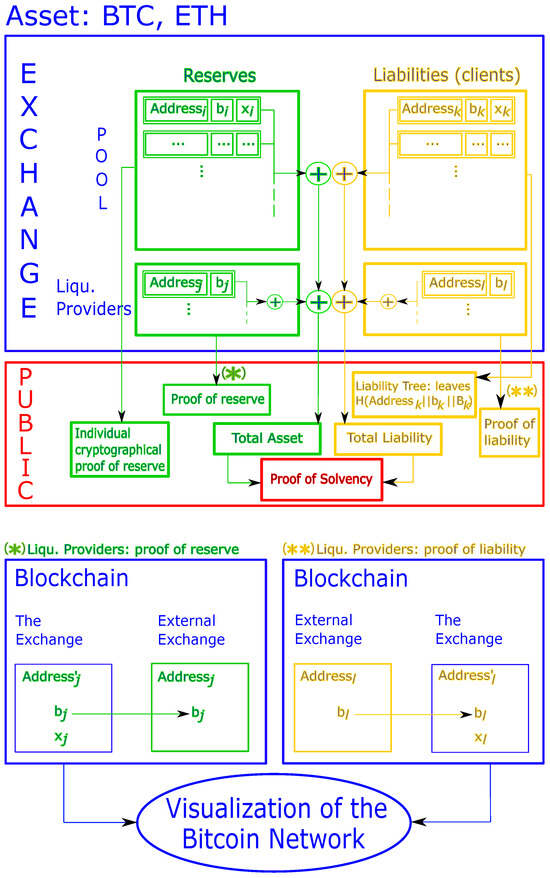

Figure 1 shows a schema explaining the details for the protocol. The sequence of this section deals with explanation of this protocol.

Figure 1.

Protocol implementation for proof of solvency, regarding bitcoin or ether assets (the b’s are the balances, x designates the private key, and B the total Liquidity Providers liability).

2.2. Exchange Proof of Reserves

In essence, cryptocurrency reserves come from addresses stored on the blockchain and owned by the exchange. This means that, for such a UTXO related to the address (i is the index identity of the considered address), the exchange possesses the private key (see the top green block in the blue ‘Exchange’ box on the top of Figure 1).

Schnorr Protocol

Providing proof of reserve for this address means proving to a counterparty that the exchange knows . We can provide a proof of knowledge of , for all the i’s, in a Zero-Knowledge framework, either by showing an adequate signature or by using the Schnorr protocol [23], which we remind as below, for any i.

- The exchange commits to the random integer (q is a large prime number which is the order of the elliptic curve secp256k1 group—a specific elliptic curve endowed with an additive operation and which is used for the Bitcoin signature; see [24], with generator G), and sends to the client . (The ‘times’ product × is the multiplication on the elliptic curve, e.g., . This step deviates from the traditional Pedersen commitment which involves two generators. Only G is sufficient here.)

- The client (or any party) sends the challenge to the exchange.

- The exchange sends to the client , (This is the usual congruence relation on ; for the mathematical details of operations on an elliptic curve, see [7,24]) and the client validates the exchange’s knowledge of if , where (the number y is the public key ). The exchange must commit to sending the public key to the client (generate one if it does not exist).

The exchange is honest if and only if the client validates, i.e., the correctness proof is given as follows:

- The client accepts if , and thus, substituting s with , we have the following:

- ,

- .

The exchange thus will prove to the client its knowledge of (see the green blocks in the red ‘Public’ box on the center of Figure 1).

Thus, at will, the exchange could provide proof of reserve from individual addresses (and can even charge anyone who wishes to validate).

An adaptation of a ZK-STARK Protocol

The reader is welcome to replace this with another Zero-Knowledge Proof of Knowledge algorithm, at their convenience, for instance, the ZK-STARK Proof, e.g., [5]. For each on-chain address , the exchange proves knowledge of for by committing (via Merkle roots) to an execution trace that computes scalar multiplication from G and the secret and satisfies an Algebraic Intermediate Representation (AIR; see [25]) whose boundary constraint enforces the public output y. Fiat–Shamir (seed c) derives the verifier’s random queries. The prover answers decommitments and supplies a Fast Reed–Solomon Interactive Oracle Proof of Proximity (FRI, ibid) low-degree proof. The verifier checks openings, constraint satisfaction at the sampled positions, low-degree via FRI, and the boundary . Zero-knowledge is preserved by trace randomization. This can be batched over all i to yield a single proof for all exchange-owned addresses.

The selection of a specific protocol rests entirely with the exchange, bearing in mind that Schnorr-style protocols involve interaction, whereas STARK-based approaches do not need to. This choice will ultimately be shaped by the exchange’s strategic priorities.

Man-in-the-middle Attack

A man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack poses a significant threat by allowing an adversary to intercept and potentially alter communications between the exchange and the client during the signature process. This could enable the attacker to forge signatures or manipulate transaction data undetected. While our adapted Schnorr protocol aims to maintain the core security properties of the original, a formal analysis is essential to ensure resilience against MITM attacks. Integrating mitigation strategies, such as those proposed by [26], who introduces a public third party (PTP) to secure multi-signature schemes against k-sum attacks, are necessary (but beyond the scope of the paper). This approach, which involves verifiable commitments and direct communication with the PTP, could offer enhanced security against MITM vulnerabilities in our adapted protocol.

2.3. External Exchanges’ Proof of Reserves

The exchange E also possesses some cryptos at external exchanges’ (see the bottom green block in the blue “Exchange” box on the top of Figure 1). The above should apply identically, but these external exchanges may have not necessarily implemented any proof protocol yet. Thus, the only ‘evidence’ the exchange has is a piece of paper, or receipt (what we call ‘receipt’ in this paper is a document which legally proves we have reserves to the external exchange; if no such document is available, then the exchange should gather the most documented paper/notification which writes it as the reserve in this exchange) as for any bank. The external exchanges provide the address and related balance , for all j’s. These addresses are not owned by the exchange E (which does not possess the private key) and cannot be proven in a zero-knowledge environment as above. However, the addresses ’s are supposed to be in the blockchain, and anyone can check their contents (including date of transaction).

Thus, there may be one way the exchange E can prove the external exchange owes cryptos to it: see in green in Figure 1. Specifically, if the external exchange owes the exchange E a balance , this means the exchange E could have sent from a previous address for which the exchange E owns the private key . Thus, the exchange E can prove it owned this address using the Schnorr protocol, depicted in Section 2.2.

In another scenario where the external exchange owes the exchange E a balance , it may also be because the exchange gave some fiats in exchange for an amount of bitcoins. In this case, refers to the receipt proving the exchange occurred. It is important to keep in mind that this receipt is the original one, used for filling the company’s balance sheet.

As a sum-up, the exchange could disclose the following:

- All the addresses ’s and ’s. The exchange can prove it owns the addresses ’s and ’s.

- The double-sh256 hash of the balances ’s and ’s—written and , respectively—related to the ’s and the ’s, to the public.

- The total reserve amount .

From these three points, there are two levels of confidentiality disclosure here:

- The exchange E does not provide any individual balance but their hashes;

- The exchange E provides all the addresses publicly so that the individual balances can be checked, but it will ask for further effort from the verifier.

Despite its non-necessary step, the hashes disclosure (point 2. above) allows the verifier to check that the reserves have been considered in the total reserve; see point 3 above. For this reason, the exchange can choose to disclose the double-sha256 hash of the total reserve instead of the total reserve itself , to further mask the reserve information. It is worth pointing out that the amounts ’s and ’s are shown in the blockchain.

2.4. Proof of Liabilities

This is the most sophisticated part of the proof-of-solvency aspects. The liabilities are acting as a symmetry to the reserves as illustrated in Figure 1: the exchange E possesses a list of addresses—which have cryptos they owe to clients, but also they owe cryptos to the external exchanges. However, the symmetry is broken due to the fact that the clients need to validate the liabilities of the exchange.

We specifically focus on addresses that are related to the exchange’s clients in this section, while next section deals with external exchanges’. Contrary to the reserves, there is a high confidentiality level when focusing on the information of the clients (e.g., their individual privacy), who have all legitimate reasons not to want to disclose their balances. Acting essentially the same as for the reserves is thus problematic. There are two causes that actually break the symmetry we have just mentioned:

- Clients do not want the public to see their information, some of which are in their addresses ’s (contrary to point 1 in Section 2.3) (see the top yellow block in the blue ‘Exchange’ box on the top of Figure 1);

- Clients can verify their own balance.

Bearing this in mind, three levels of disclosure are possible (and we believe only three are possible):

- Either the exchange E discloses all the client balances or ’s only. This will allow individuals to see all the liabilities and simply add them to obtain the exchange’s total liability. The problem with this possibility is that it does not prove that exchange E owes these values, and it does not allow individual clients to check if they indeed have an indicated balance, only that there are two identical balances, which is not trustworthy. This possibility is confusing, non-informative, and it violates point 1 above.

- To remedy the issue raised in point 1, the only way exchange E proves it owes the above disclosed balances is to disclose the related addresses ’s so that the exchange provides a proof it owns the private keys using the Schnorr protocol and follows the protocol given in Section 2.2. The strong disadvantage is that clients’ addresses are disclosed, which is dissatisfying.

- The last solution is that the exchange E is an intermediate between its clients and the public by providing, for example, the Liability Tree service (see Section 2.7). Although it does not provide a proof at any time contrary to the previous point, it does not invalidate that exchange E did not provide all its clients’ liabilities, unless the exchange has been dishonest and that a client realizes that their balance is incorrect. In this case, exchange E should take the risk to be severely punished by a third party, e.g., regulators or state, who likely will require any exchange to provide a solid blockchain-based balance sheet. There is simple evidence that anyone could see a number of addresses on the blockchain, which are related to liabilities: when a customer makes a buy order as an input, an explosion of outputs will be localized into the blockchain; see Section 5 explaining the Particles model. As such, a cluster of transactions will be necessarily identified to the exchange E’s platform. For this reason, we will indicate that exchange E implements this last point, in addition to the Particles model.

As a result, it seems essential to make explicit the constitution of the leaves for the Liability Tree. Section 2.7 explains in detail how to construct a Liability Tree.

2.5. External Exchanges Proof of Liabilities

In the context in which exchange E owes bitcoins to an external exchange (see the bottom yellow block in the blue “Exchange” box on the top of Figure 1), it could mean the external exchange has given bitcoins to the exchange E from address (external exchange) to address ’s owned by exchange E (see in yellow in Figure 1), which thus possesses the private key and can prove it knows this using the Schnorr protocol (Section 2.2).

In the scenario where exchange E owes bitcoins because it received fiats in exchange for an amount of bitcoins, here again, refers to the receipt showing this transaction occurred. As for the proof of reserve, it is important to keep in mind that this receipt is the original one, used for filling the company’s balance sheet. In all the cases, exchange E can prove liability to external exchanges.

To sum up, the exchange could disclose the following:

- All the (exchange’s) clients’ leaves hashes ’s (see Section 2.7);

- The total external exchanges’ liability ;

- The liability root as well as its balance , which is the total liability;

- All the external exchanges addresses ’s.

In order to further mask information, the exchange could provide the hash , instead of in point 2 above, and the verifier could indeed check that these liabilities have been considered.

2.6. General Proof of Solvency Protocol in the Crypto Case

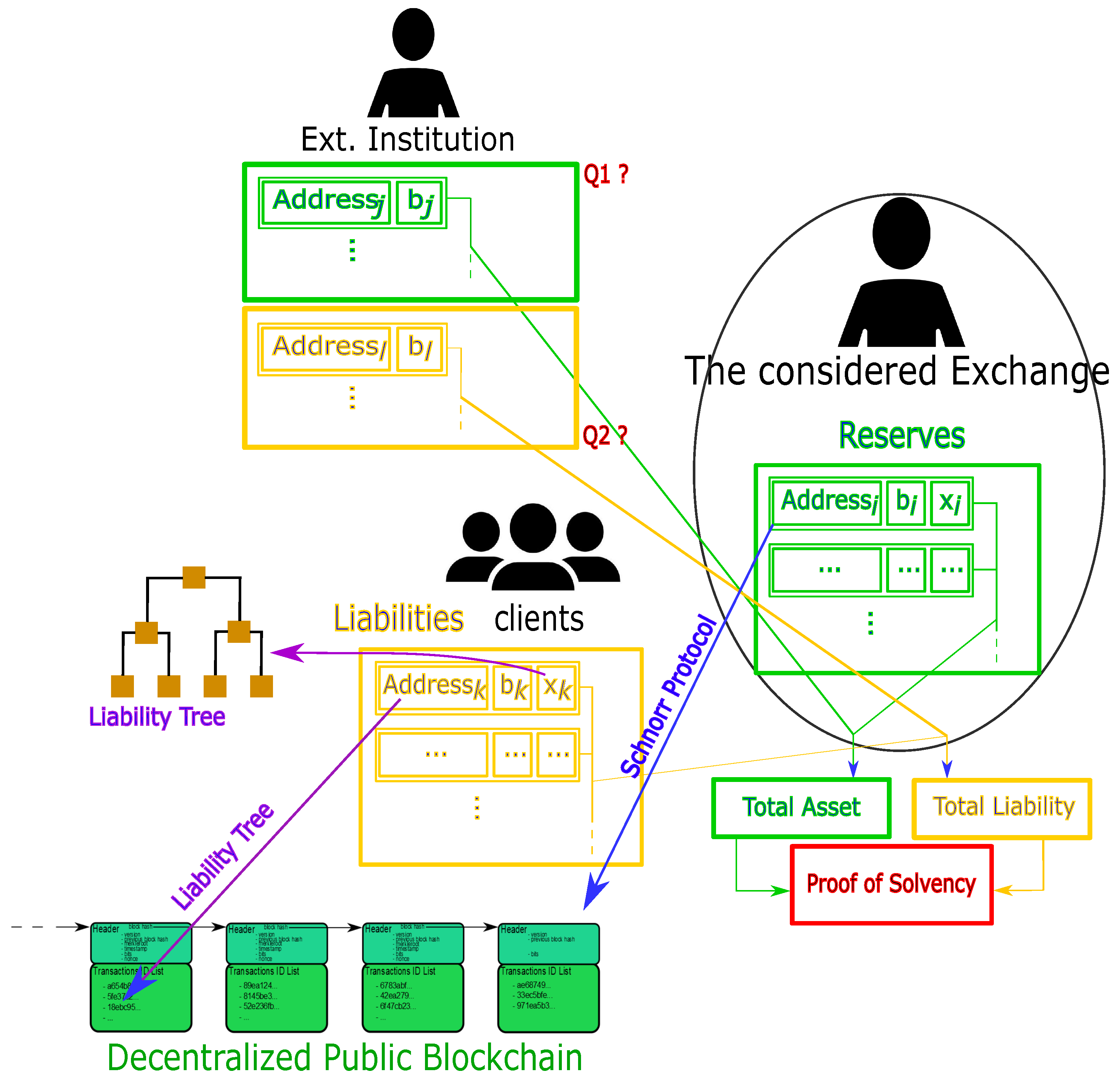

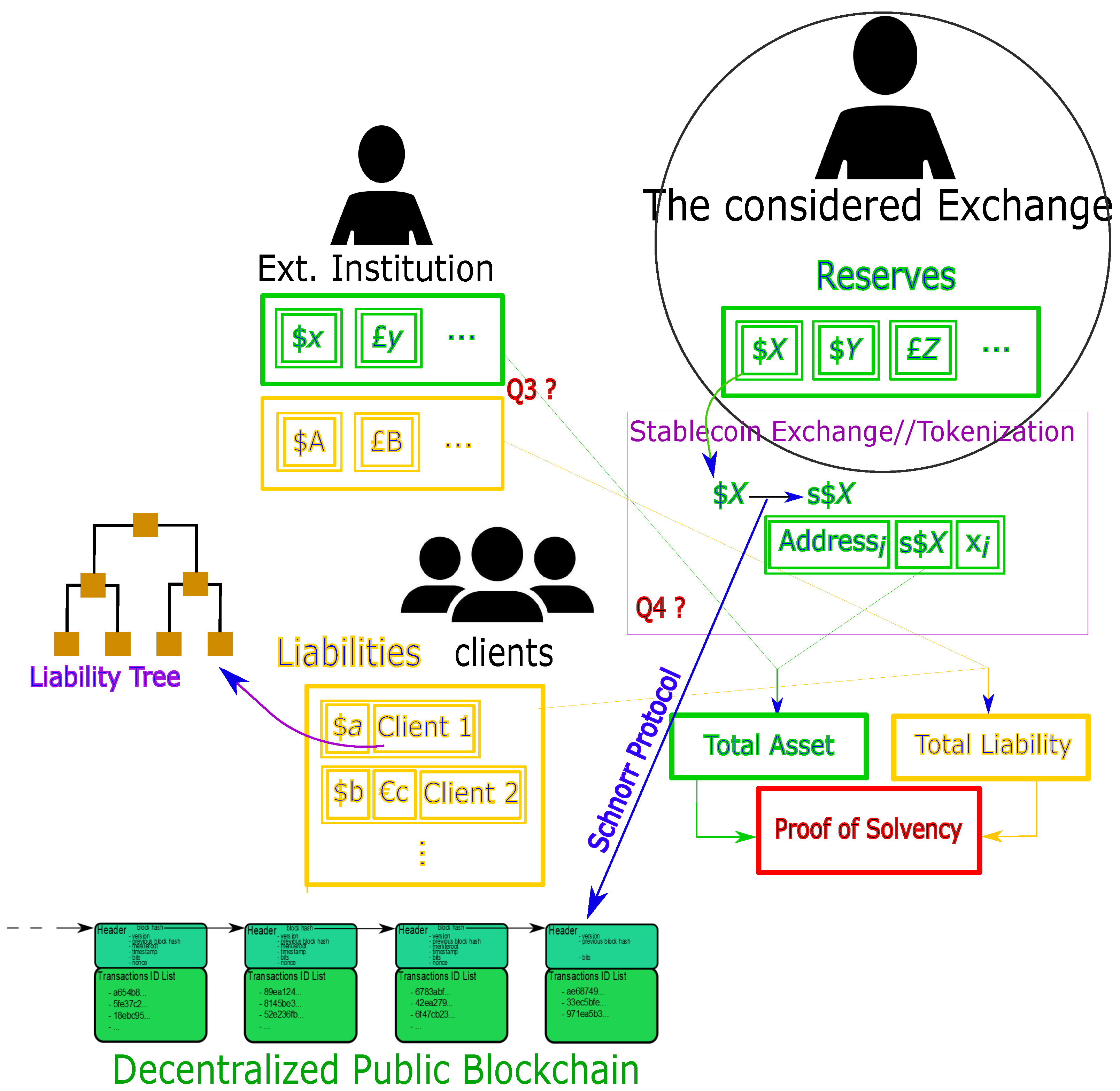

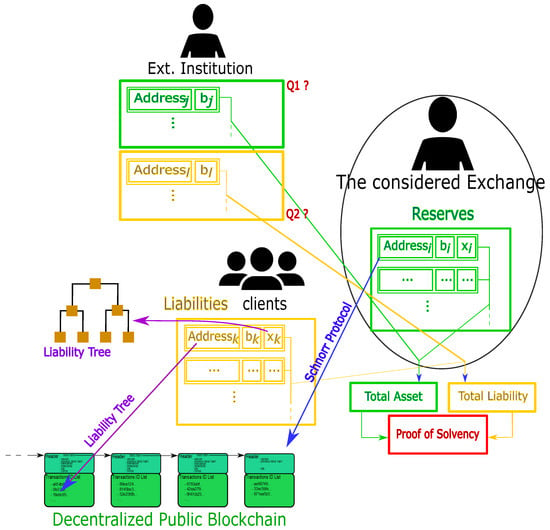

Figure 2 synthesizes the above proofs in the crypto case. Two main questions are indicated, and we provide answers to them below.

Figure 2.

General solvency protocol for the crypto environment. The considered institution is in a center of a market (right-hand-side in the figure) within its clients and external liquidity providers (both left-hand-side). The considered institution has reserves (green) in UTXOs and they own the private keys ’s, allowing them proving reserves through a Schnorr protocol, given the fact that the underlying blockchain is public. The institution also has reserves elsewhere, raising question Q1 (see text). In addition, the considered institution has liabilities (yellow) regarding their clients, and it possesses the private keys. Running the Liability Tree (see Section 2.7) is a possibility to allow the clients to check that the institution does have their money. The considered institution also has liabilities to external liquidity providers, leading to question Q2.

Figure 2 sheds light on two essential questions in case the external institution has not implemented the above proof-of-solvency protocol.

Exchange E could possess its reserves elsewhere, hence the question Q1: what if the external exchange cannot provide a proof of asset? We see two possibilities:

- Either exchange E provides a proof of address input (if any) from which the funds have traveled (from exchange to external institution) (see (*) in Figure 1);

- Or there is no choice of a usual governance (the exchange E is free to ask a proof to the external institution though).

Similarly, the exchange E could owe some cryptos to external institutions, leading to the question Q2: How do we prove exchange E has external institution liability? Here again, there are two possibilities:

- Either the exchange E provides proof of address output (if any) from which the funds have traveled (from external institution to exchange) (see (**) in Figure 1),

- Or there is no choice of a usual governance (and again exchange E is free to ask for proof to the external institution).

We conclude that to avoid usual audits and allow 24/7 proof of solvency from a blockchain, the above process has to be standardized.

2.7. The Liability Tree

This section explains a method which actually is inspired from the Merkle Tree. The method is explained in [2], but we propose simplifications for building the Liability Tree. It is worth pointing out that the exposed algorithms here use a vectorization approach: all the hashes are calculated at the same time. One could still complexify the leaves to further respect privacy as in [6].

2.7.1. Construction of the Tree

We set the total liability owed by the exchange to the external exchanges (the exchange can always prove it owes individual liabilities to its liquidity providers; see Section 2.5).

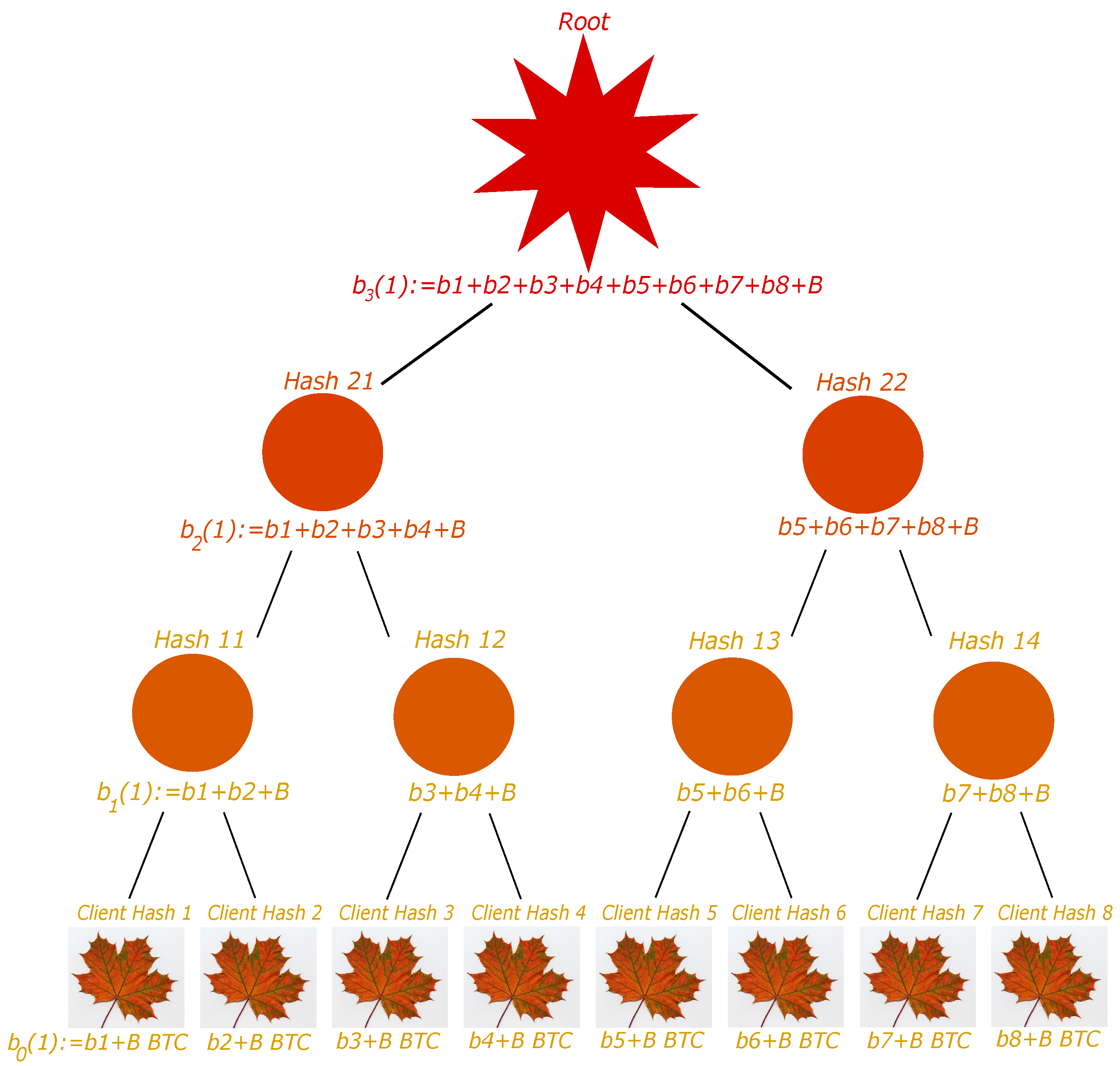

Particular Case

We suppose we have a number of clients which is a power of 2. The exchange may create the tree as follows; see Figure 3. First, each account is organized as a leaf of a binary tree. To each leaf, we associate its hash given by , with the associated balance (and not only ). Then, each odd-ranked leaf has its hash, concatenated with the next even-ranked leaf’s, and the whole obtained vector is hashed once more. The account balance associated with this parent node is the sum of its children balance, minus B. The process is repeated again until reaching the root of the binary tree. It turns out that the balance associated with the root represents all the liabilities the exchange owes to its clients and external exchanges.

Figure 3.

The Liability Tree. Each customer account is a leaf, and their hash and account balance, added with the total external exchanges’ liability B, are associated. Then each pair of IDs is concatenated and hashed into a node in the first floor, to which the sum of the below balances is associated, minus the total external exchanges’ liability. The process is iteratively repeated until reaching the root. The root and the leaves are shown to the customers for verification of their account. The balance associated with the root is the exchange’s total liability. In the notations of Algorithms 1–3, for instance, (ground floor ) is the node under ‘Client Hash 4’, (there are 8 leaves); is the node under ‘Hash 13’ (first floor ), ; the height of the tree is , etc.

To elaborate more on the associated balances, the balance of a parent node is not given only by the sum of balances of its two children, but we now require the balance to be . In this case, it can easily be proven that the balance associated with the liability root is the exchange total liability. Indeed, two brother leaves have balance and , where and are the balances of the two considered clients. The parent node therefore has balance . This easily generalizes to each floor. Thus, the last floor balance is , which is the exchange total liability.

It is worth pointing out that the hash function can be an appropriate one, particularly the SHA 3 (solving the issue of the CVE from using once the SHA 256 function) or the fast SHA256 function; see [27].

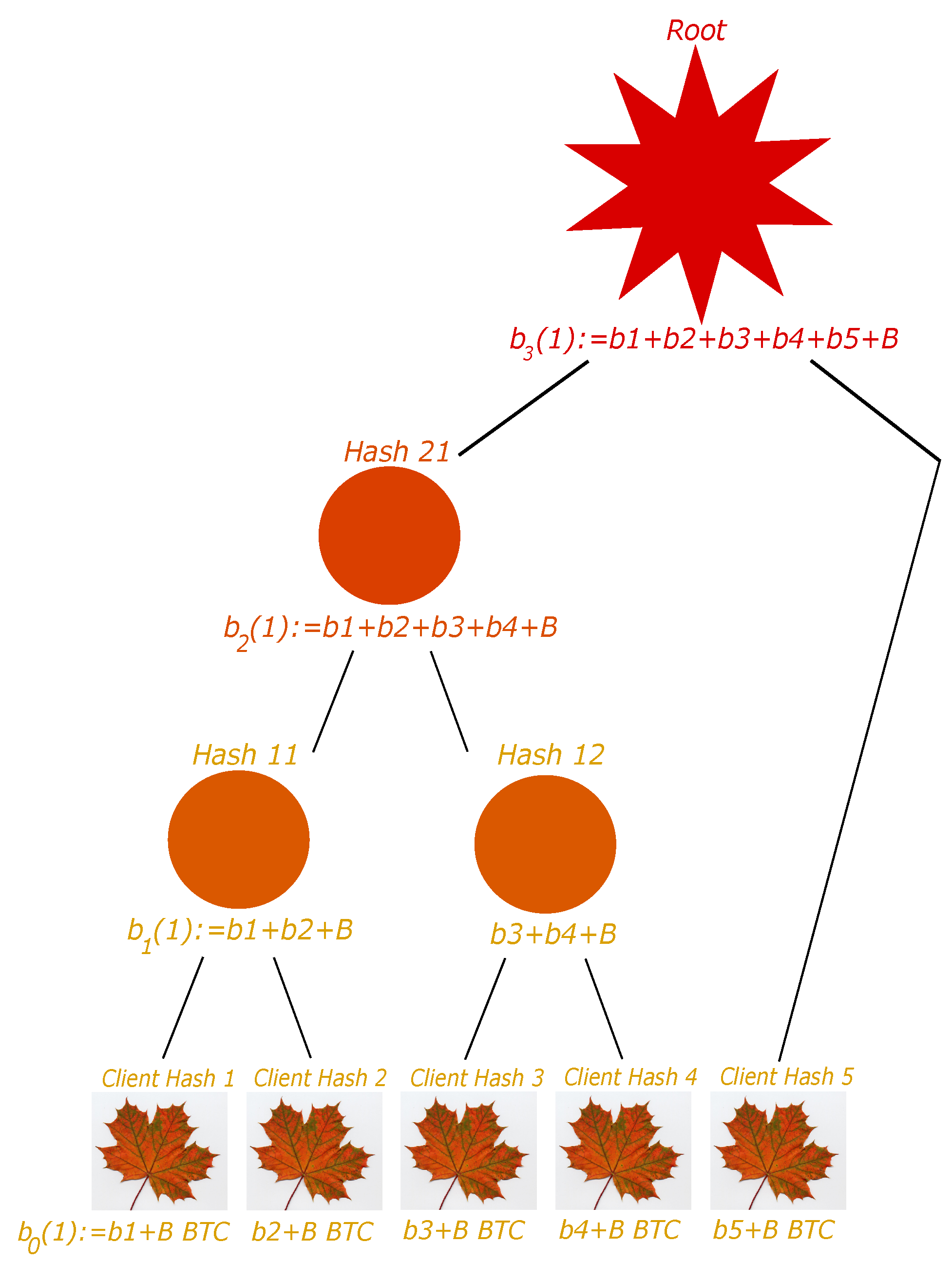

General Case

We suppose that the number of clients is not necessarily a power of 2. We consider a given floor. If the number of nodes is even, then we perform the hashing as previously explained to obtain the nodes at the above floor. If the number of nodes is odd, then we do the same but by not considering the last node, and we put this later node at the above floor. This simple process can be repeated iteratively. See Figure 4 and Figure 5 for examples.

Figure 4.

General case 1: client number 5 is considered a node in the second floor.

Figure 5.

General case 2: client number 7 is considered a node in the first floor.

More generally, we have the following Algorithm 1. We still call f the hashing function, and the -dimensional vector of nodes at floor . We note the balance vector at floor h. Finally, note that ‘’ means that r is removed from memory if it has not already performed.

There are at most three vector operations per loop: concatenation of with the last element of in case is odd, then concatenation of (odd components of ) with , and the f application to it. The complexity of this algorithm is therefore .

| Algorithm 1: Liability Tree computation. |

|

| Algorithm 2: Authentication Path Computation |

|

| Algorithm 3: Liability Tree and authentication path computations. |

|

2.7.2. Verification by Client

From the construction of the Liability Tree owned by the exchange, and only the exchange, we are going to explain how the client can verify their account well.

Liability Root and Authentication Path

The exchange provides to the client, who wants to verify that their account is an exchange’s liability, the Liability root, and the Authentication path. The following Algorithm 2 provides an efficient iterative way to calculate the authentication path from the tree.

The complexity of this algorithm is with two calculations per loop. Indeed, the primary loop iterates from the client’s starting floor up to the root of the tree, with height . Therefore, the number of loop iterations is directly related to the height of the tree.

It is worth pointing out that space can be saved by not remembering the full tree (simply replace and both by (independent of h) in the above Algorithms 1 and 2).

Verification

The client has the provided data (their hashed account) and , as well as the root. She therefore iteratively can use

to find the liability root at final, and see if this coincides with the one provided by the exchange. The client is sure their account is an exchange’s liability is both liability roots coincide.

For the reader’s convenience, Algorithm 3 includes the Liability Tree and authentication path calculations at the same time.

3. Proof-of-Solvency Protocol for Fiats

To the best of our knowledge, there are only two possibilities for providing proof of solvency for the fiats.

- Receipts: The exchange is providing a receipt to the users as well as a live statement generated by the external liquidity provider. This ideal case is possible without blockchain and requires trust.

- Tokenization: The exchange possesses one token per fiat, and there is a blockchain associated with the token version of the fiat so that all transactions can be followed live. Tokens are redeemed to the client each time they sell crypto-assets (see [28]). The exchange E can then systematically prove it has assets and liabilities, and a stablecoin exchange, which thus possesses all the fiat collateral, are subject to usual audits. This stablecoin exchange plays the role of a bridge between the world of cryptos and the world of fiats. It could be a regulator or a state.

3.1. On Stablecoins Creation

The only possibility to make cryptographic proofs, such as the ones for the crypto case (see previous sections), is to create a token pegged to a given fiat and use these instead of pure fiats. In this case, the previous Section 2 applies.

Although providing a receipt is the simplest way to show proof of transaction, we all know that a receipt is a piece of paper that does not guarantee the statement truth at any time, because it is showing cash flow between two distinct parties at a given date. For any given time, a receipt is not telling where the cash is (e.g., FTX, 3 Arrows Capital): in an exchange, users’ money is subject to Order Book, validating transactions by matching with others so that money cannot be ‘sleeping’ in an account just after the time of the transaction (any bank client can have access to bank reports explaining how the exchange proceeds but reports generally are heavy, and client’s knowledge is not necessarily advanced in banking and its jurisdiction, so their understanding highly is limited). Nevertheless, a statement does not provide the situation of users’ money within the Order Book neither but states what the exchange owes to the client, even if it is not guaranteed that the bank has sufficient reserve. It is worth pointing out that this issue might be solved in Decentralized Exchanges (DEX), though still representing a strong minority in the market.

We see that the only possibility to follow the trace of one’s money is to expose precisely where it is, and the concept of blockchain does satisfy this requirement. This means that the exchange should operate with stablecoins backed to fiat, and have access to the underlying blockchains thus created.

As indicated earlier, the entities which issue stablecoins are playing the role of bridges. They cannot use blockchain to prove they have fiat reserves, and thus they must be usually audited. However, the rest of the world could exclusively possess tokens and could therefore seize the opportunity to prove they are solvent or not in a 24/7 manner through blockchains. In particular, the full previous sections apply.

3.2. General Proof of Solvency Protocol in the Fiat Case

Figure 6 sheds light on two essential questions in case the external institutions have not implemented the above proof of solvency protocol and in the context of fiats.

Figure 6.

The considered institution is in a center of a market (right-hand-side in the figure) within its clients and external liquidity providers (both left-hand-side), at the likes of Figure 2. The ‘Stablecoin Exchange’ (i.e., the bridge) allows fiat tokenization, and it issues token versus fiat cash. Thus the ‘Stablecoin Exchange’ will need regular usual audits to manage its fiat reserves. If it is a state, the fiat cash could be used for further investments or debt payments with other states. Thus, ‘Stablecoin Exchanges’ are bridges between the fiat world (set of states in the world if they are states) and the token/crypto world (set of companies in the world). The interaction with external institutions and the considered one, as well as with the ‘Stablecoin Exchange’, raise two questions, Q3 and Q4, which we address in the text.

The exchange E could possess its reserves and liabilities elsewhere, hence question Q3: what if the external institution does not have stablecoins or tokenized reserves? We see two possibilities:

- Exchange E asks the external institution to tokenize their fiat cash and to align with the solvency protocol;

- Or there is no choice of a usual governance.

Similarly, the following question Q4 is very natural: How do we prove the stablecoin exchange has the reserves? The only possibility here is usual audits.

In order to work fluently, tokenization needs to be performed altogether to gain its efficiency. Bearing with all the above in mind, we conclude that the above solvency protocol should be standardized and its implementation controlled by authorities as regulators and states.

4. Some Suggestions for Information Disclosure

In addition to the above solvency protocol, we propose the following disclosure plan. This is unnecessary but it still provides further transparency.

4.1. Proving the Reserves

- All the addresses ’s (the exchange) and ’s (other external exchanges—see text for more details);

- The hash of the balances ’s and ’s-resp. written and -resp. related to the ’s and the ’s, to the public;

- The total reserve amount .

4.2. Proving the Liabilities

- All the (exchange) clients’ leaves hashes ’s;

- The total external exchanges’ liability ;

- All the external exchanges addresses ’s (see text for more details);

- The liability root as well as its balance , which is the total liability.

5. The Particles Model

We have proposed, in the previous sections, a practical protocol for proof of solvency. There is one particular point the above protocol does not solve: it has to provide information which the exchange may want not to provide. It is thus likely that the privacy requirement will not be fully satisfied. To solve this issue, we may propose a model which in the order book (the Pool) divides one address into millions of sub-addresses (particles) in order to further mask privacy. This is the Particles model.

It is worth pointing out that the content of this section is a immediate continuation of Chapter 7, Section 4 of [7], where the Particles model was introduced. We completely reintroduce it and much further develop the fundamentals and practical implementation.

5.1. Setting the Model Scene

An innovative method to enhance transaction anonymity within the Pool involves the strategic dilution of transaction amounts when a client places an order. This process entails the division of an amount X BTC () into a variety of distinct UTXOs for recording on the blockchain. The Pool orchestrates a transaction where X BTC serves as the input, and the output consists of n UTXOs (). The amounts are distributed such that the first UTXO contains BTC and the second BTC, continuing in this manner. Such transactions can be arranged to incur no fees, facilitated through pre-agreed contracts with miners, who are compensated separately. This methodology can result in extensive UTXOs per transaction, indicating a potentially large n.

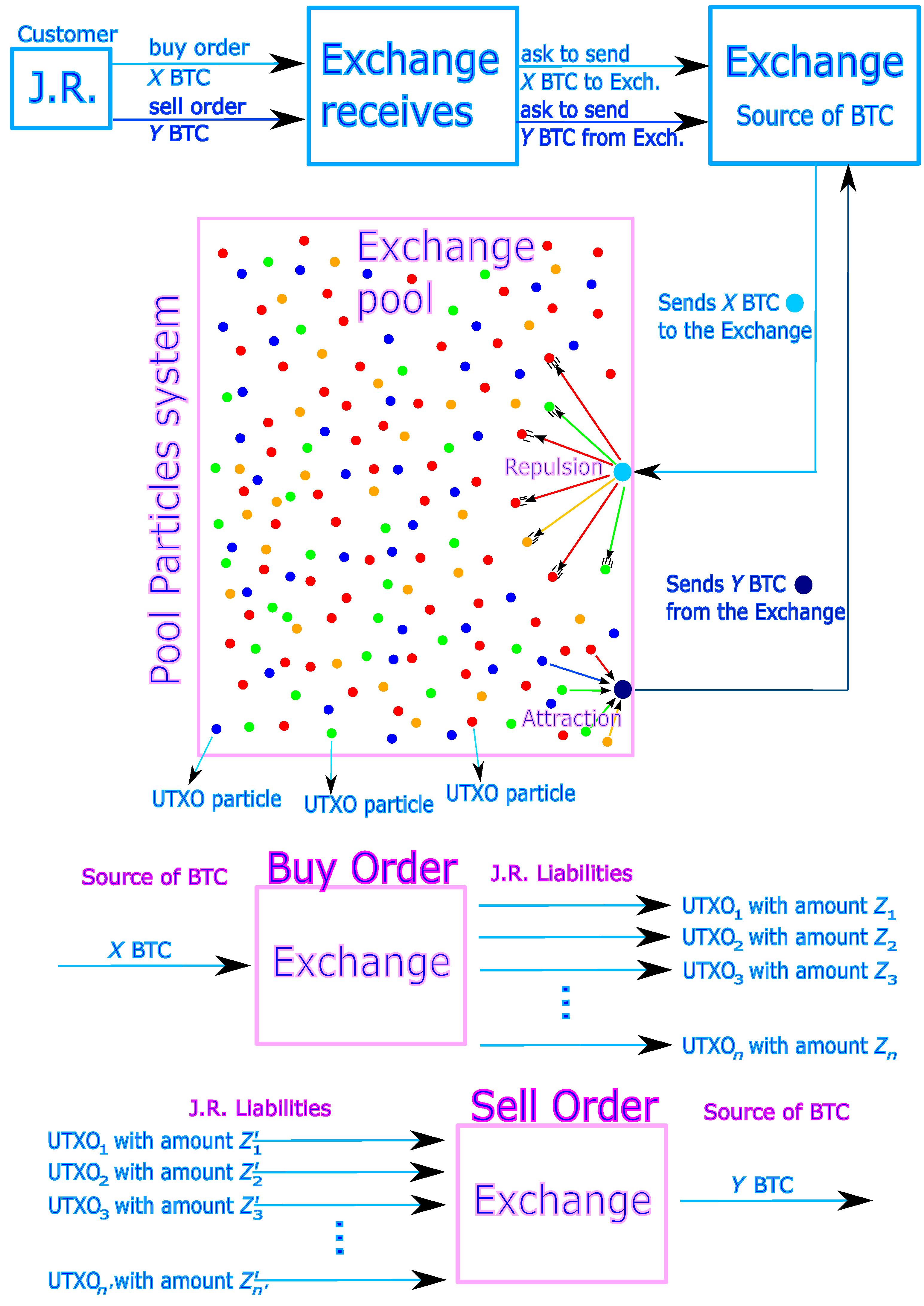

The concept extends to all transactional procedures within the Pool, whereby each client’s orders generate a multitude of smaller UTXOs, hereafter called particles. These particles contain fragmentary amounts of cryptocurrency, too small to serve as standalone inputs for conventional transactions. Nonetheless, by aggregating an appropriate combination of particles, it becomes possible to construct valid transfer transactions. For example, when executing a sell operation, particles can be selectively combined to produce a precise BTC quantity, effectively retracing the original BTC supply (depicted in the inverse route within Figure 7). This particle-based approach resembles the mechanics of an order book, with the added advantage of order fragmentation, which promotes greater matching efficiency. Over time, the Pool transforms into a dynamic assembly of particles, where repulsive interactions encourage the splitting of X BTC into smaller units, and attractive forces foster the recombination of particles to form Y BTC, maintaining systemic stability. The conceptual model is visually summarized in Figure 7 (from [7]).

Figure 7.

The Particles model: a customer balance is decomposed into several particles, i.e., UTXOs of very small BTC amounts. The particles constitute the matter of each amounts, and gravitating in the Exchange pool system where reign forces of repulsion (giving the particles in case of buy order) and of attraction (in case of sell order). This results in significant improvement of privacy, as it becomes much harder to follow the identity of customers (Source: [7]).

From a practical standpoint, a key challenge is to define a methodology for determining the optimal number of particles n generated from a given amount X, along with the respective amounts . Furthermore, it is necessary to establish procedures for selecting a subset of these particles whose combined value closely approximates Y BTC. It is important to note that an exact reconstruction of Y may not always be feasible; the reconstructed sum should never exceed Y, as clients are not authorized to transact beyond their original request. Nevertheless, with a sufficiently large and diverse set of particles, the likelihood of achieving a sum near Y increases statistically. The particles are heterogeneous, akin to different kinds of fundamental matter, each characterized by distinct properties that influence their selection and combination.

5.2. Trading Dynamics

In the following, the monetary unit is the satoshi (so all variables are integers).

5.2.1. The Mathematical Problems

We focus on the following mathematical problem: how many particles constitute an amount of X satoshis, and what are their associated values?

Definition 1.

We set the

buy order

problem as

with constraints

where are given integers (independent of X).

We set the

sell order

problem as

In the buy-order problem set, the numbers X, the ’s and the ’s are all given integers. The goal is thus to derive n and the ’s. In practice, we may choose (a UTXO has minimum 1 satoshi) for all i, while (which is the maximum relevant UTXO value to consider it as a particle, perhaps around 100,000 satoshis) for all i. We keep the general case by considering and a priori function of i.

The solution for the sell-order problem is highly dependent on the one for the buy-order problem. In the latter, the numbers are derived for a given X. In the former, there is a bunch of existing numbers derived from several values of X (several buy orders), and there are N particles in total in the Exchange Pool system (see Figure 7). We obviously expect that , at least in the long run, once there have been sufficient buy orders. Contrary to the buy-order problem, there always is a solution for the sell-order problem, where the idea is to have , and the equality is statistically guaranteed if N and n are sufficiently large (which is expected since these UTXOs are particles): once the exchange receives the sell order for amount Y, an appropriate number of particles gather to form the amount Y. In addition, we see that not only does the above framework provide further privacy but it also allows higher liquidity in the exchange, particularly for sell orders.

Before proposing a solution, we need to make sure that this problem makes sense, i.e., if there are indeed solutions, and, in the ideal case, how many. This is related to the partition of integers problem; see [29,30,31]. As an illustration, if we take the simple case where , then and , , , , and are possible solutions.

5.2.2. Buy-Order Problem—Conditions for the Existence of Solutions

First note that we immediately have a condition on X, which is given by

where and are the empirical means for the ’s and the ’s, respectively.

We claim that at least one solution exists if and only if X satisfies Inequalities (5), which is equivalent to giving a necessary and sufficient condition on n for the existence of solutions: Inequalities (5) are equivalent to

Thus, the number n can be any integer contained in the interval .

5.2.3. Number of Solutions for the Buy-Order Problem

This section develops the number of solutions for the above problems (2) and (3) in Section 5.2.1 from the most general case to our particular case of interest and (constant values). We may choose the generating function lead to solve the question. We assume that the conditions on Section 5.2.2 are satisfied so that there exists at least one solution to problems (2) and (3).

Theorem 1.

Proof.

We first simplify the problem, without any loss of generality. We set

where l is the empirical mean for the ’s so that problems (2) and (3) are equivalent to

with constraints

where is a given integer (independent of ) for any i.

We derive below the number of solutions for problems (8) and (9). The generating function for the number of partitions satisfying the problem’s constraints can be derived using standard combinatorial arguments (see [29,30,31] for background on partition generating functions). The function given by

which indeed normally converges for any real x such that , and is the number of solutions for problems (8) and (9), when m is the integer to partition, can actually be written as [31]

when we consider a sum of n integers. We are looking for the derivation of . By bearing in mind the fact that

we expand the generating function as follows:

From the formal power series expansion

we then have

Now, we use the appropriate variable change:

by bearing in mind that if the integers and are such that so that

By the unicity of coefficients, we conclude by extracting the coefficient of , which is the number of solutions for problems (8) and (9):

Now, also suppose that (relevant practical case for implementation purposes). Equation (12) becomes

Examples

As an illustration, suppose that , , and (no constraint since ). Then the sum over is zero since for any , so there are

possibilities to write with the constraints , which indeed are , and . As another verification, choose , , and . Then

Indeed, there is just one way to write , given the constraints , that is .

6. Practical Solutions and Algorithms

6.1. A Practical Solution for the Buy-Order Problem

We propose a simple solution—there exists at least one as proven in Section 5.2.3—to the problems (2) and (3).

Assumption 1.

We will make the following Assumptions all together:

- and for all i (all particles have the same properties);

- The ’s are all the same (symmetry argument);

- For any X, n is a convex expression in the set (see Inequalities (6)).

By the third point of the previous Assumption, we mean that

and that the parameter is universal, i.e., independent of X. It is therefore a calibrated parameter.

Theorem 2.

There exists a solution to the buy-order problem, which is such that all the particles have an equal amount. In addition, this amount is independent of X when X is sufficiently high.

Proof.

The buy-order problem then becomes

Therefore, we have

We are going to see that this choice implies that is approximately independent of X. Since, for any real x, we have that

that is

If , then and there is nothing else to do. Otherwise, we have

Bearing this in mind, we may assert that ( since it is assumed that a customer buys (or sells) much more than a satoshi)

This writes as

Hence the ’s all have the same value. This also means that, for two distinct buy orders of respective amounts X and , the difference in amount between the set of ’s derived from X and the one derived from is

This is negligible when X and are in the neighborhood of infinity. All the particles have their amount approximately given by . □

The amount is controlled through the universal parameter , that can be calibrated.

Algorithm

Let us assume that . We have and .

If one chooses to be the initial calibrated number as the middle of , i.e., , then

and

If one chooses as the calibrated number, then , and . If n does not divide X, then we could perform the Euclidean division of X by n so that , with , and allocate r to n UTXOs, then allocate z to one UTXO.

To sum up, we have the following more general Algorithm 4. In Section 7.3, we will see that the fair price-optimal calibrated number is indeed .

There is one calculation for the value of n, and a Euclidean division, which means that the complexity of this algorithm only is .

Add Randomness

We could decide to add randomness to the obtained result. This is convenient if the exchange wants to mask more of the the deterministic pattern above. Once we obtain the numbers , we may choose a random integer from 1 to n. We then randomly choose particles and, for each of them, we repeat the above process. This will result in more particles with smaller amounts.

| Algorithm 4: Buy Order Algorithm |

Result: Obtain the appropriate number of particles as the result of the buy order. The client is setting a buy order with amount X

Inputs: Client’s request of amount X; Outputs:

|

Examples,

Choose satoshis. Then we obtain 5 UTXOs of 2 satoshis. If we choose to add randomness, let be the selected random number. Then randomly pick 3 UTXOs, e.g., the first, the third, and the fifth, and repeat the above process: each selected UTXO gives 2 UTXOs whose respective amount is 1 satoshi. We finally obtain 8 UTXOs, 6 with amount of 1 satoshi, and 2 with amount 2 satoshis.

Choose satoshis. Then we obtain 5 UTXOs of 2 satoshis and 1 UTXO of 1 satoshi. If we choose to add randomness, let be the selected random number, and we choose, say, the first, the third, and the fifth UTXO. According to the previous example, we finally obtain 8 UTXOs, 7 UTXOs with amount of 1 satoshi, and 2 UTXOs with an amount of 2 satoshis.

6.2. A Practical Solution for the Sell-Order Problem

In this section, we propose a solution for the sell-order problem (4), highly dependent on the solution to the problems (2) and (3). We suppose the Pool has a high quantity N of particles with amounts . The solution proposed below is practical and easily implementable, and it is essential that, during the process, we do not come to a higher amount than the required one—but the idea is to come closer and closer to it using all the available particles. We also give examples later below.

For a given , we proceed with the following Algorithm 5. Suppose the exchange has different amounts for all its particles (with indeed N particles in total), and set these amounts such that . Let be the family of positive integers such that is the number of particles whose amount is , for all . It is worth pointing out that the total number of particles is .

The following Theorem 3 has its notations from Algorithm 5.

Theorem 3.

Algorithm 5 provides that the , , are the closest to Y successively. In addition, if , then so that Step 4 is well defined.

Proof.

We focus on the heredity of this algorithm (put , and set ). Perform the Euclidean division of with respect to to have , with . Then, for amount , is the maximal possible number of particles to implode since, if one was to implode particles with amount , we then would have hence

which is unexpected. Therefore step k is imploding at most particles with amount , hence, if step k is imploding exactly particles with amount , then we deduce that is the closest amount to involving all particles with amount , for any . When , Step 4 guarantees that, when there remains at least a particle (i.e., ), the algorithm obtains Y as the output amount for the sell order since, if , then such that , and, using Equation (16) with and that , we have

where the sum ‘’ is 0 if , which ends the proof. □

| Algorithm 5: Sell-order algorithm. |

Result: Obtain the most appropriate output value from a given bunch of particles. The client is setting a sell order with amount Y;

Inputs:

Outputs:

|

The advantage of this Algorithm 5 for the exchange is that particles with large amounts do not allow to precisely come closer, by below, to the required amount Y. Thus, the algorithm does not only utilize many particles with little amount, but also it converges fast in time by utilizing particles with large amounts first. There are at most distinct particles, thus this algorithm complexity is at most .

Examples

- Suppose and we have the following particle amounts five times (), five times (), and eight times ().We proceed as follows: the Euclidean division of with respect to (w.r.t.) is , thus , and set . It remains particle of amount .Next, the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains particles of amount .Finally, the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains particles of amount . The algorithm stops there, and .

- Suppose and we have the following particle amounts ten times (), 2 twenty times (), and hundred times ().We proceed as follows: the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains no particle of amount .Next, the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains particles of amount .Finally, the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains particles of amount . The algorithm stops there, and .

- Suppose and we have the following particle amounts nineteen times (), and three times ().We proceed as follows: the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains one particle of amount .Next, the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains no particle of amount .Finally, set , and we explode Z into and , so that we obtain . One particle of amount is created.

- Suppose and we have the following particle amounts twenty times (), only.We proceed as follows: the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains particles of amount .Finally, set , and we explode Z into and , so that we obtain . One particle of amount is created.

- Suppose and we have the following particle amounts thirty times (), and ten times ().We proceed as follows: the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains particles of amount .Next, the Euclidean division of w.r.t. is , thus , and set . It remains particles of amount .Finally, set , and we explode Z into and , so that we obtain . One particle of amount is created.

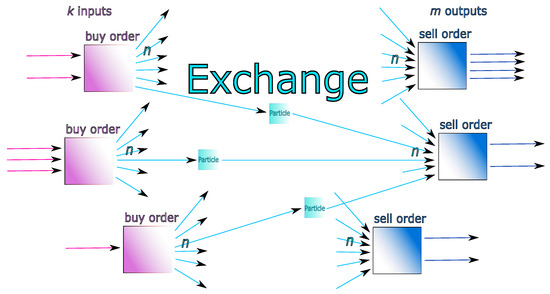

6.3. Buy (Respectively, Sell)-Order Problem: Inputs (Respectively, Outputs)

For cost-reduction purposes, as well as masking more privacy, the exchange can consider a set of p distinct buy orders to form particles () from the same user or, better, distinct users. In this case, if we designate by the amount for the buy order, we set . Section 5.2.3 and Section 6.1 then apply to X thus defined. This means that the p orders are forming a unique ‘super’ buy order as shown in the bottom of Figure 7.

In addition, the Pool could form a set of outputs of a ‘super’ sell order, obtained by gathering the set of current sell orders in the market. If we introduce as the amount of the sell order, we set . Section 6.2 then applies to Y thus defined.

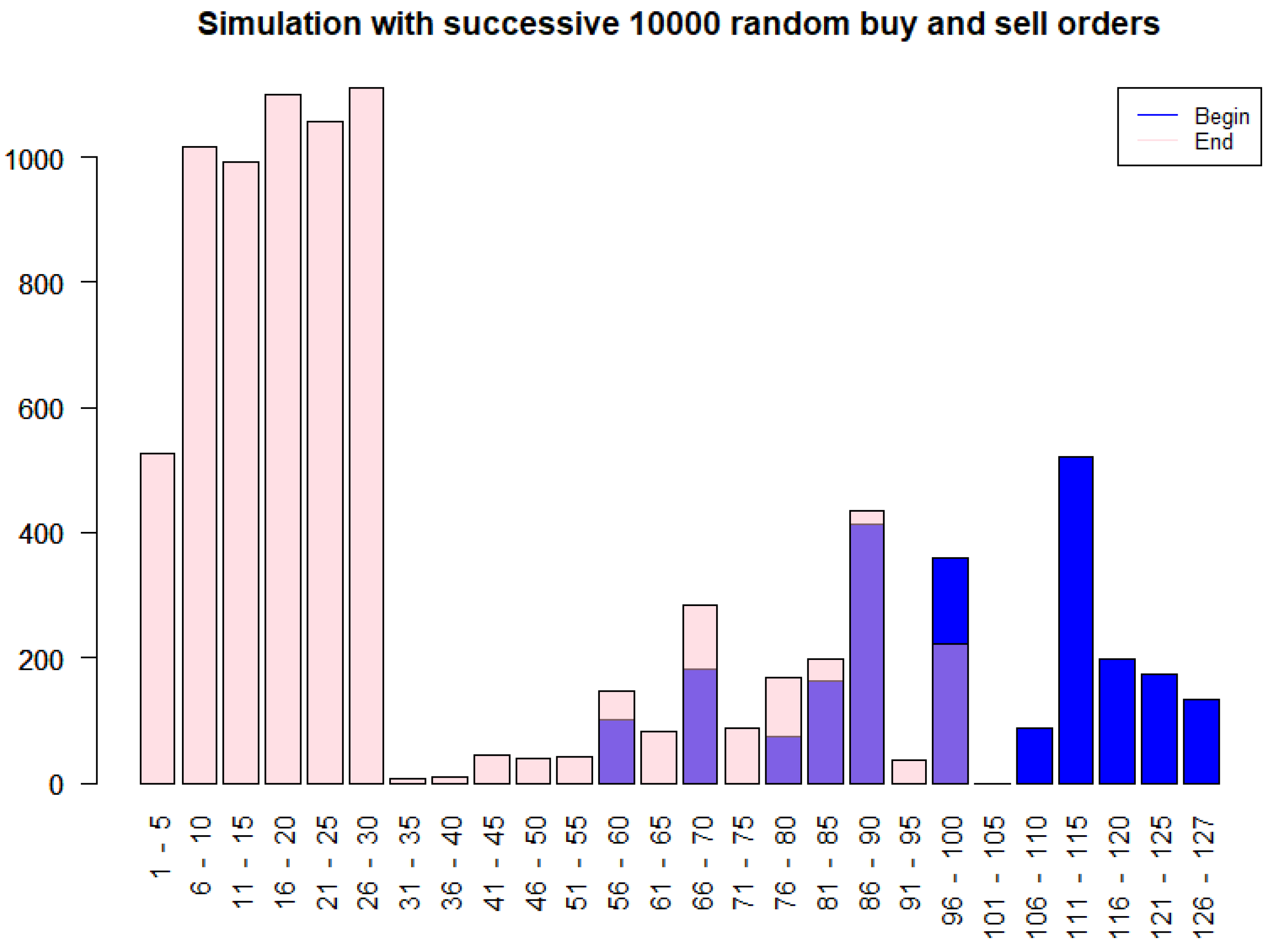

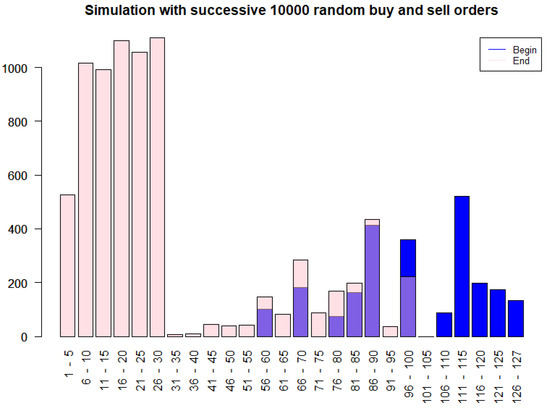

6.4. Simulation of an Order-Book System Subject to the Particles Model

To illustrate the dynamic behavior of the Particles model, we conducted a simulation of a simplified order book subject to 10,000 consecutive random buy and sell orders. The initial state (depicted in blue in Figure 8) consisted of particles with relatively larger amounts of bitcoins. The simulation, implemented in R on a standard laptop (32 GB RAM, Windows 11) and completed in approximately 10 s, used . After the 10,000 simulated orders, the resulting distribution (shown in pink) reveals a shift towards a greater abundance of smaller-cash particles, indicating a tendency for the system to fragment larger UTXOs into smaller denominations through the buy/sell action. This dynamical fragmentation is consistent with the theoretical framework above and enhances the exchange’s trading liquidity, as sell orders can be fulfilled more readily and with greater precision.

Figure 8.

UTXO distribution before (blue) and after (pink) 10,000 random buy/sell orders in the Particles model, demonstrating fragmentation into smaller denominations and improving trading liquidity.

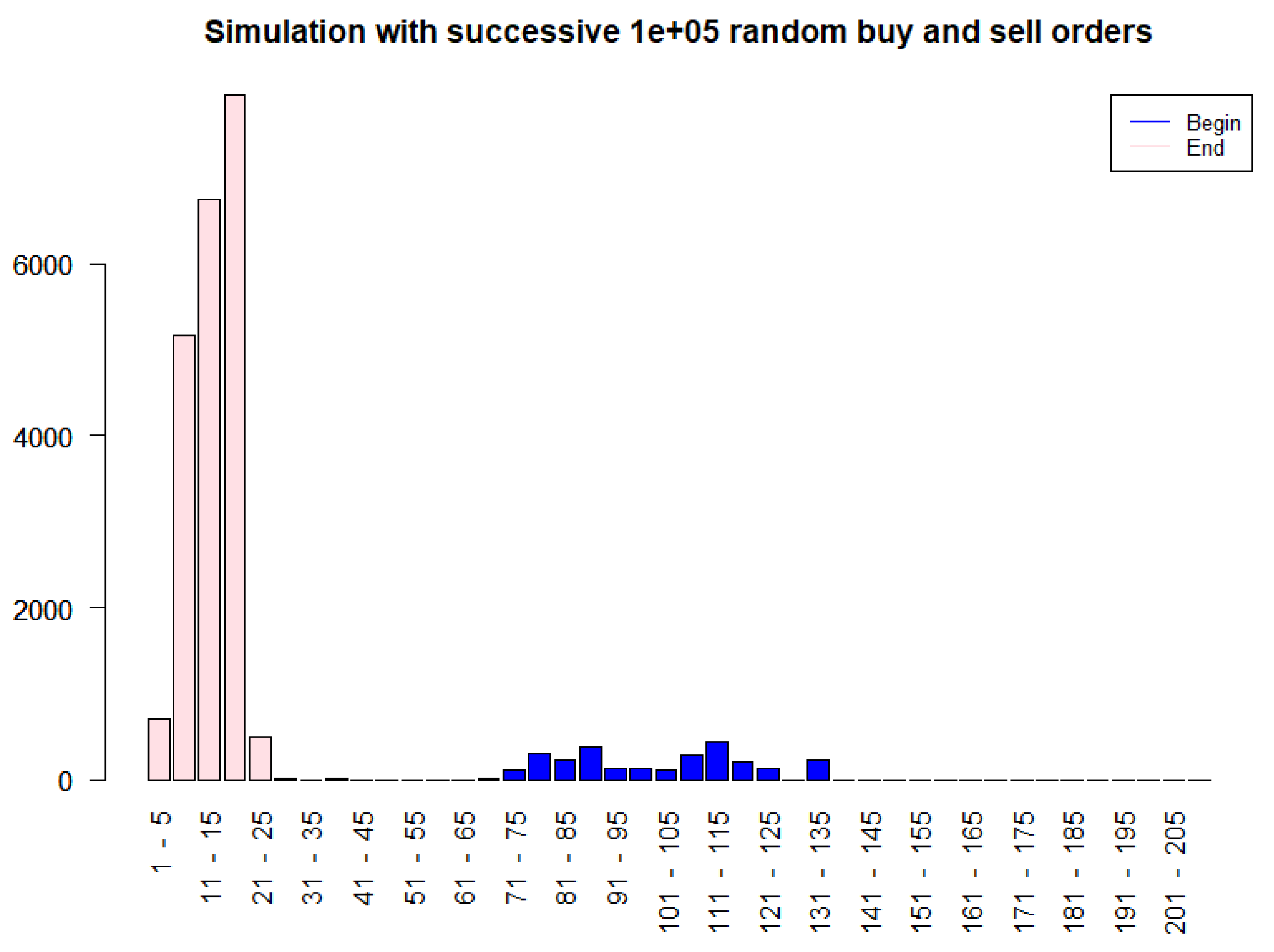

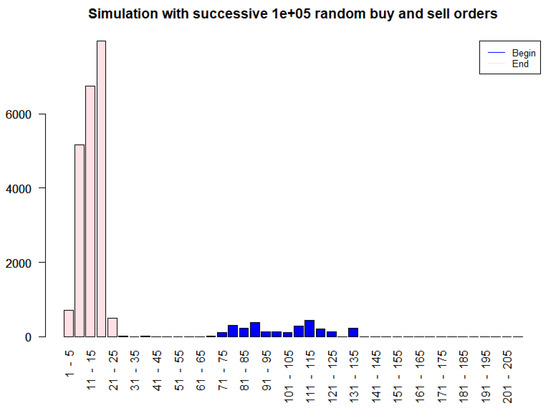

For illustration purposes, we also performed the simulation for 100,000 simulated orders in Figure 9 (3 min).

Figure 9.

UTXO distribution before (blue) and after (pink) 100,000 random buy/sell orders in the Particles model.

7. Optimal Calibration

In this section—which is an application of the above modeling to an exchange which uses the Particles model—we introduce a novel approach to Optimal Calibration, an important component for the practical deployment of our proof-of-solvency framework. This section moves beyond simply ensuring solvency and privacy to address the economic viability of the proposed system. By deriving a fair price for transactions, we aim to create a sustainable ecosystem that benefits both the exchange and its users. This optimal calibration is a piece of the puzzle for encouraging the broader adoption of our framework and providing advantages to the CEX.

7.1. Transaction Fair Price

From [32], it is possible to evaluate the size (in bytes) of a transaction.

Definition 2.

If a system of T transactions has K inputs and M outputs in total, the total cost to perform this system of transactions is given by

where In = 148 and Out = 34 (Input script type: P2PKH; one signature per input; no pubkey). In addition, we introduce the

fair price

of a transaction as

which is the average cost per transaction of the system (note that, in Equation (18) and for a given number T of transactions, if K and M are random variables (hence C is random), then we would better use the definition . The equality is an intuitive condition for an exchange to be sufficiently liquid).

For BTC, 1 byte is 1 BTC satoshi so that Equation (18) gives the price in BTC satoshis for one system with T transactions, K inputs, and M outputs.

7.2. Fair Price-Optimal Calibration

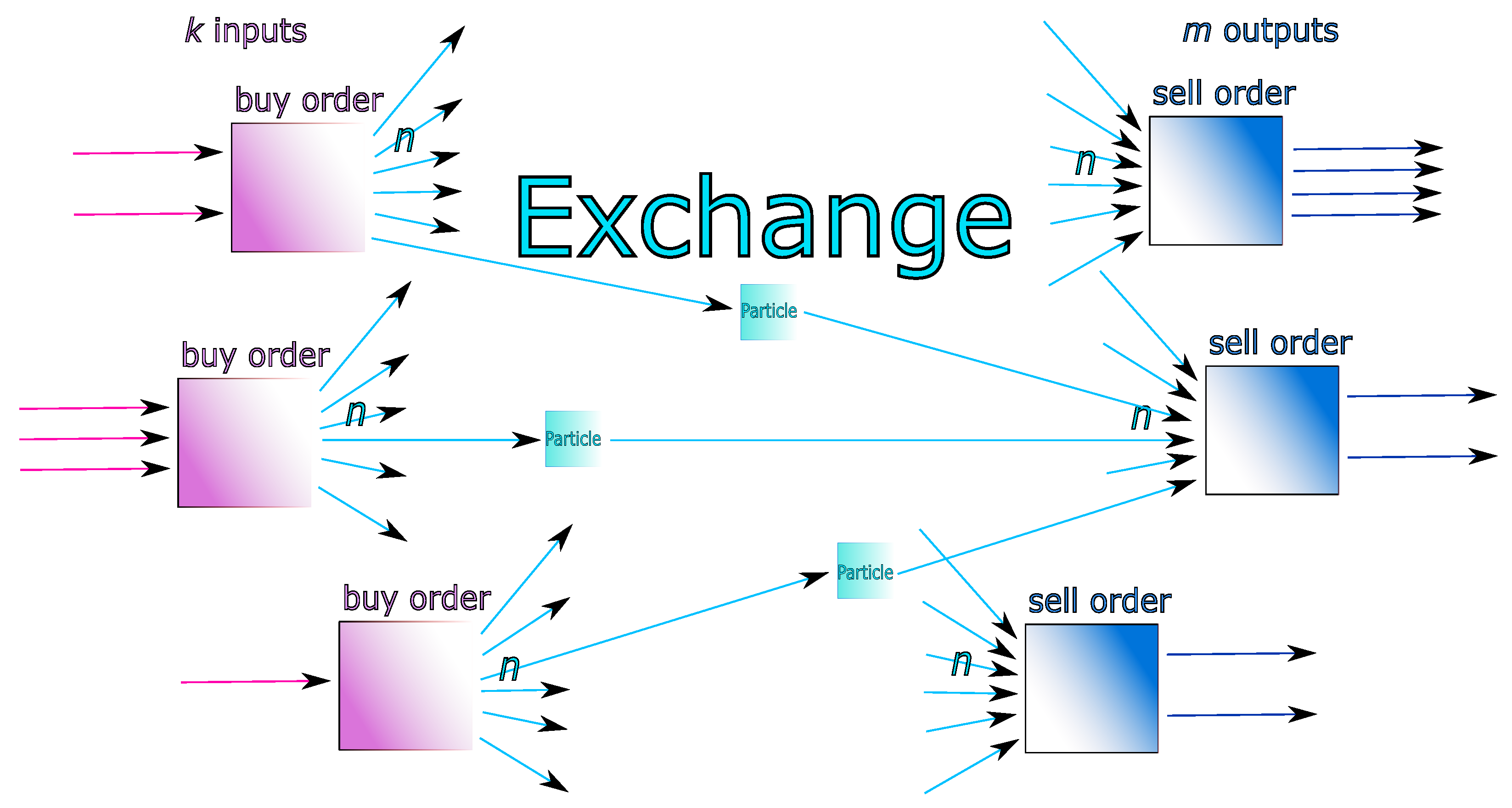

We consider total number of inputs of buy-order transactions, which have i inputs, and total number of outputs of sell-order transactions, which have i outputs. Let and , which are the total inputs of buy-order transactions, respectively, outputs of sell-order transactions. We can calculate the total cost of the system in Figure 10. We indeed have ( is the number of sell-order transactions of i outputs), , and so that we have the following theorem.

Figure 10.

Illustration of a sets of inputs and outputs interacting with the exchange. There are buy-order transactions (left-hand side, purple boxes) having in total k inputs, and sell-order transactions (right-hand side, blue boxes) having in total m outputs. We suppose, to simplify, that there are systematically n particles involved for explosions and implosions. We are able to derive a fair price-optimal calibrated strategy (source of the figure: [7]).

Assumption 2.

The average condition for the price refers to when , for all i (as many buy orders with i inputs than sell orders with i outputs, for those existing).

Theorem 4.

With the above notations, and under the average condition, the optimal fair price is given by

where is the average transaction value for buy orders, is the calibrated value giving the optimal price, and A is a constant depending on the system.

Proof.

The total price of system shown in Figure 10 is given by

The fair price is given by

From Equation (22), the average condition leads to

where . We now set as the average transaction value in the exchange, for buy and sell orders, that is, in light of Equation (13), the value satisfies

Since , we have that

Since the map is strictly non-increasing (), and since there are integers in , there exists a maximal value such that is the minimal-valued integer contained in .

Thus, we obtain the optimal fair price , given by

This is the optimal fair price corresponding to the cost-optimal calibrated parameter . □

It is worth mentioning that r can be interpreted as the average amount associated with particles.

7.3. Fair Price, Optimal Calibration—Numerical Application

We can obtain the value of from the exchange. As an example, on average, customers make buy or sell orders with amount BTC. Hence = 100,000 , so that, on the one hand, and . With , the minimal fair price is given by

With this calibration, the fair price of a transaction is given by USD 52.9.

8. Experiments and Results

In this section, we provide empirical evidence supporting the feasibility, scalability, and advantages of the proposed proof-of-solvency protocol and the Particles model. The evaluation focuses on five key aspects: (i) computational efficiency of the Liability Tree, (ii) privacy enhancement through particleization, and (iii) liquidity improvement and numerical validation of the fair price calibration.

All simulations were performed on a standard laptop (Intel i7, 32 GB RAM). Since real client liabilities are not publicly accessible, we set ourselves as a virtual exchange and generated synthetic datasets that mimic realistic exchange distributions: client liabilities were sampled from log-normal distributions, while order sizes were drawn from exponential distributions to replicate heavy-tailed trading behavior. Unless otherwise noted, we simulated between and clients and between and trading orders. Publicly available blockchain data were not required for these tests, though the algorithms are designed to operate, for instance, on actual Bitcoin or Ethereum address sets.

For comparative purposes, we contrast our approach with baseline solvency structures relying solely on naive Merkle Trees (without privacy enhancements) and simple UTXO pools (without particleization).

8.1. Liability Tree Efficiency

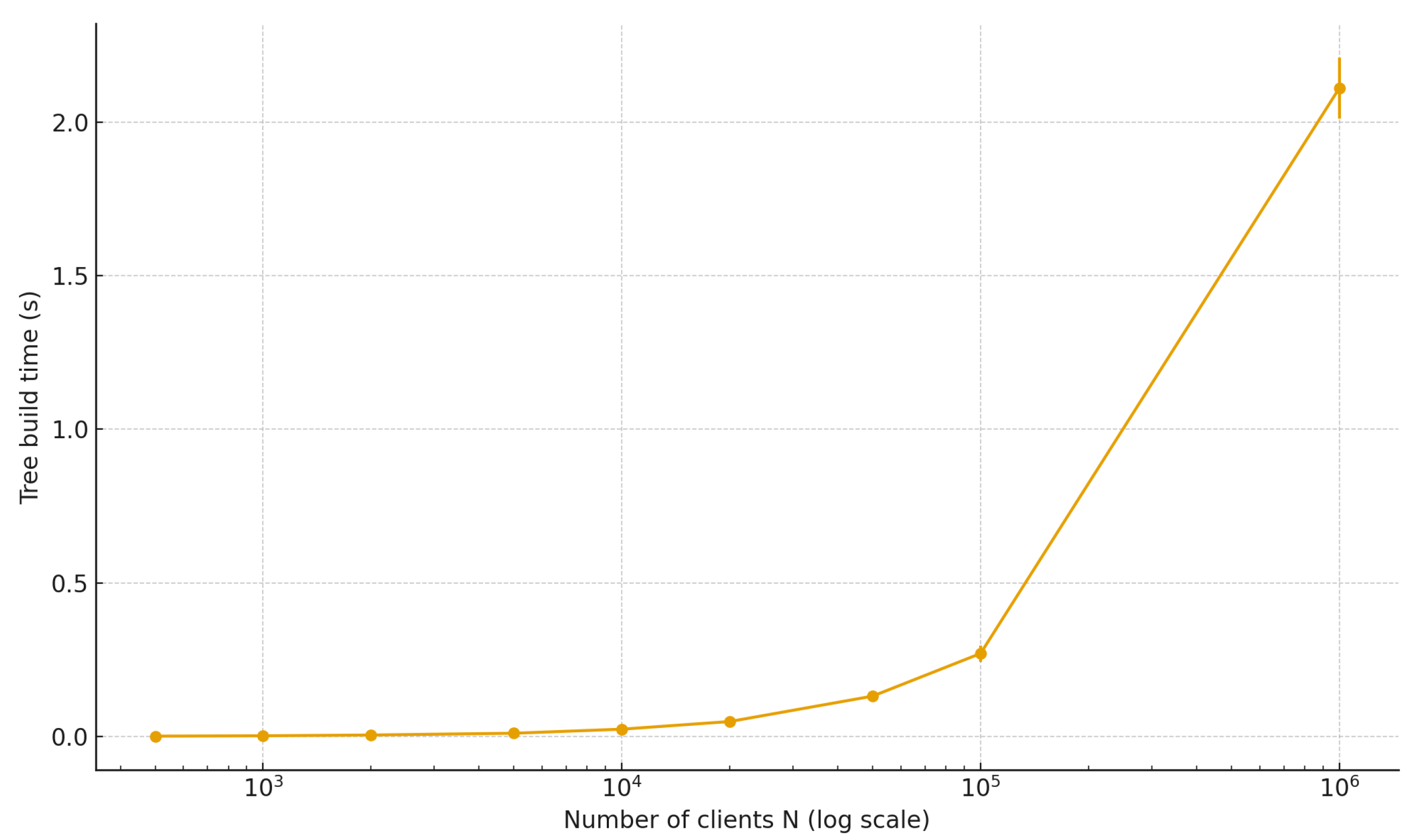

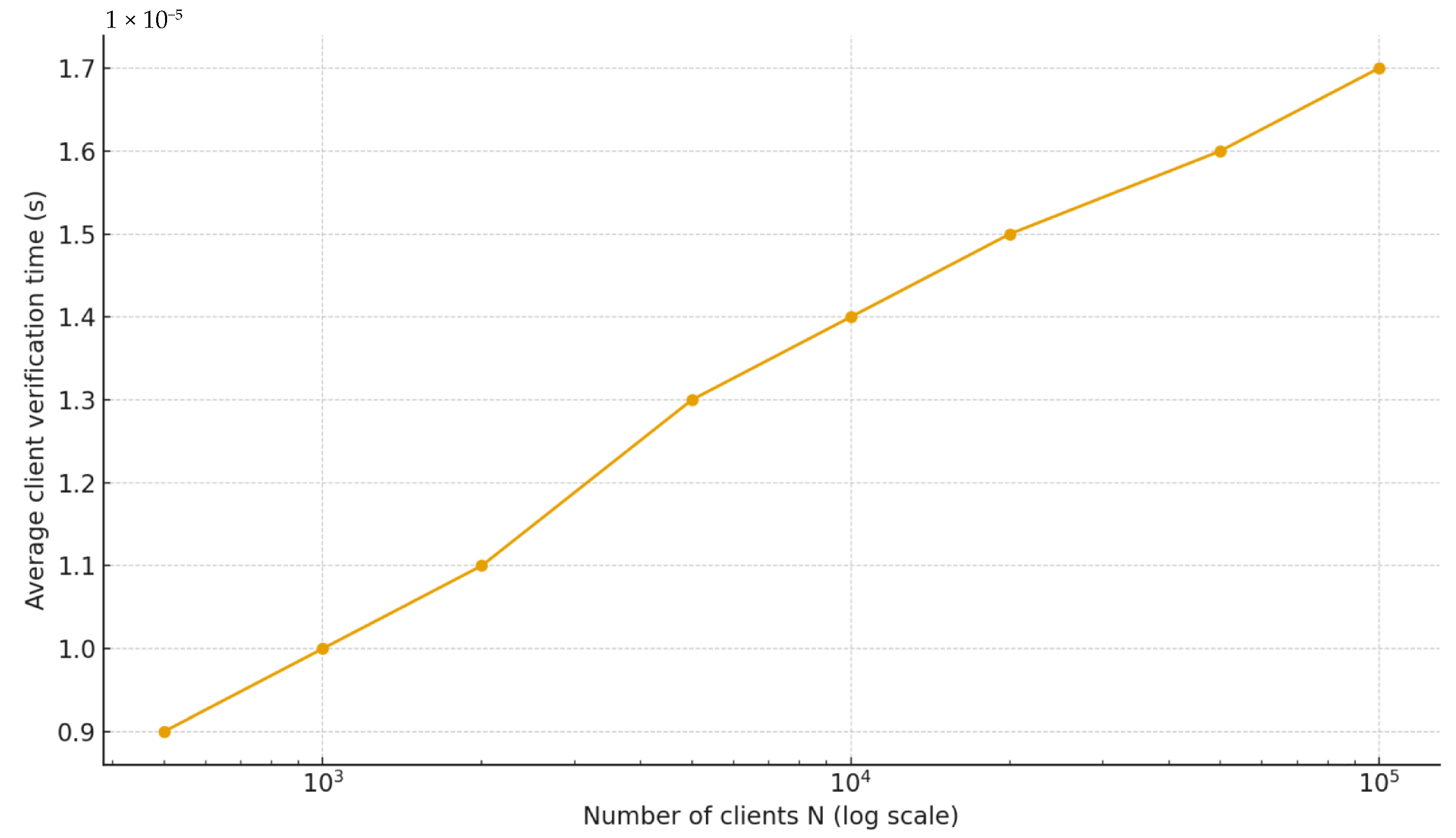

We first evaluate the computational feasibility of building and verifying Liability Trees for different client populations. Table 1 reports tree height, construction time, average verification latency, and proof sizes.

Table 1.

Liability Tree simulations (10 runs—error bars not represented for the average verification time, as they are of the same magnitude order).

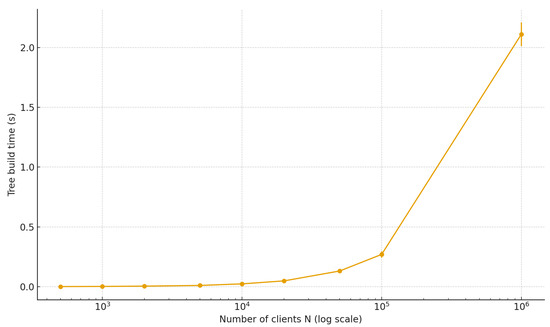

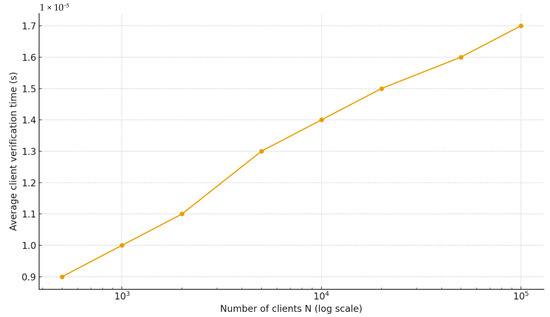

Figure 11.

Liability Tree construction time as a function of the number of clients N, averaged over 10 independent runs. Error bars indicate one standard deviation around the mean. Build time scales linearly in N, yet remains within a few seconds even for clients.

Figure 12.

Client-side verification time as a function of the number of clients N. Since verification requires hash computations, the cost grows logarithmically. Verification remains in the order of tens of microseconds even for millions of clients, confirming the practicality of the approach (error bars not represented, as they are of the same magnitude order).

- The time to construct the Liability Tree grows linearly with N. Even for clients, the tree can be built in well under a second; at clients, extrapolated construction remains feasible in ∼2 s.

- Verification requires only hashes, resulting in sub-millisecond client-side verification times. Proof sizes remain compact (<1 kB even for a million clients).

These results demonstrate that the Liability Tree is both computationally and communicationally lightweight, enabling continuous proof-of-liability at exchange scale without burdening clients.

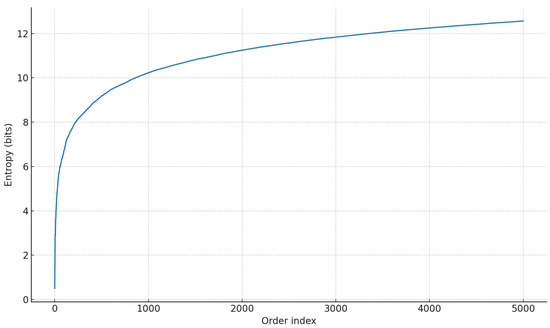

8.2. Privacy Enhancement via the Particles Model

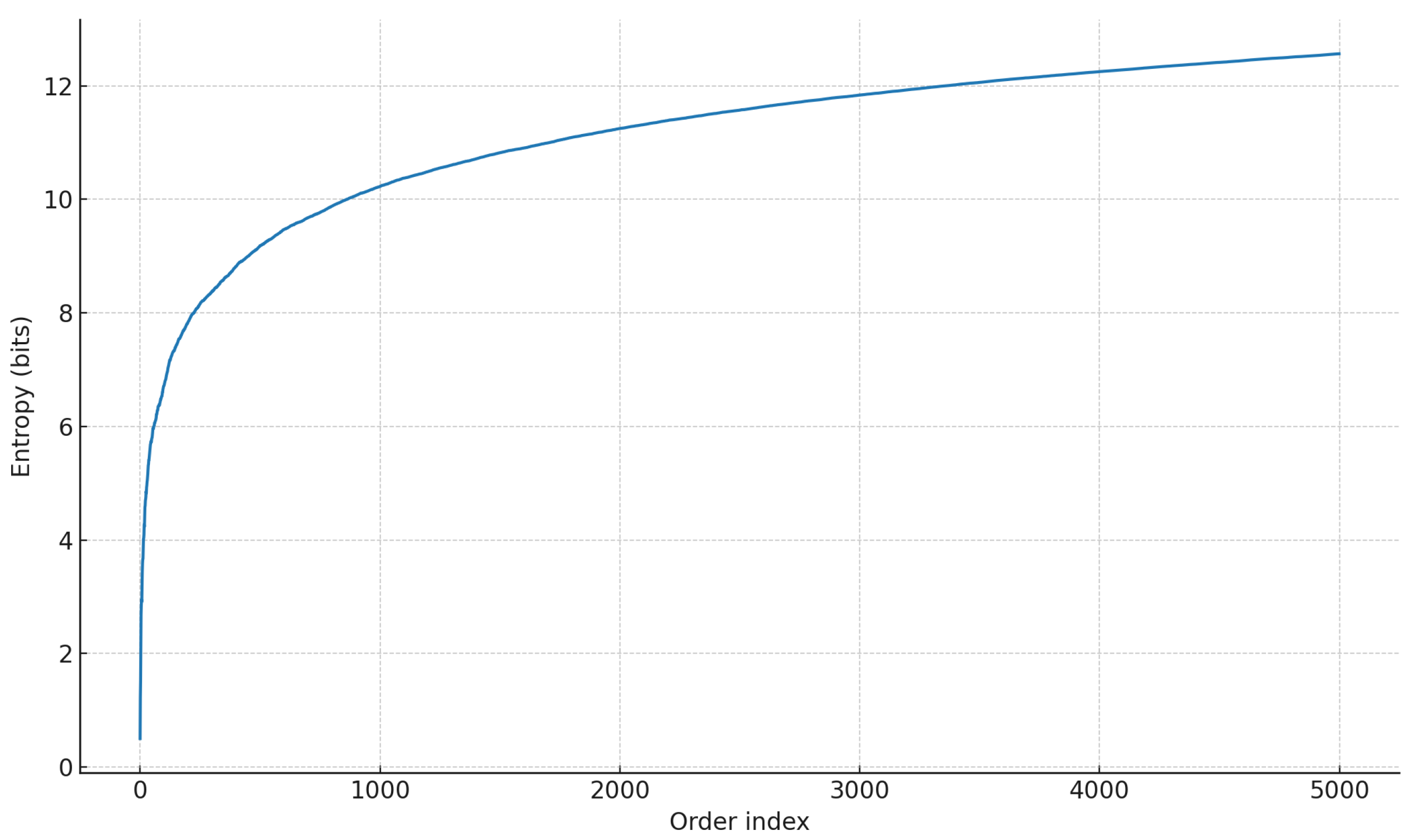

We next quantify anonymity gains. Without particleization, each order generates a single UTXO, making entropy effectively zero. With the Particles model, buy orders are split into 2-100 fragments, and anonymity is measured as Shannon entropy of active user indistinguishability [7].

As Figure 13 illustrates, entropy increases steadily with order activity, yielding anonymity sets equivalent to several hundred indistinguishable users in practice. This demonstrates that the Particles model significantly reduces the probability of successful tracing attacks.

Figure 13.

Anonymity entropy over time for the Particles model (mean of 10 runs). Entropy steadily increases as the number of processed orders grows, reaching double-digit values within a few thousand orders. This confirms that particleization substantially enhances privacy by enlarging the anonymity set over time.

8.3. Liquidity Improvement and Fair Price Validation

We compare the ability of baseline vs. particleized order books to satisfy sell orders. Baseline matching was restricted to direct, two-sum, or three-sum UTXO combinations, while the Particles model employed our greedy Algorithm 5 with splitting when necessary. More specifically, the fill ratio is the fraction of sell orders that can be exactly satisfied (matched) by available particles in the pool at the moment of the request. We ran the following experiment for 12 k buy orders and 5 k sell orders (which took ≈ 150 s):

- Baseline pool (particleization): Each buy creates one UTXO of size satoshis. For each sell, the matcher tries (in order): (i) exact match, (ii) two-sum, (iii) three-sum. To keep the runtime reasonable at this scale, the search was capped: candidates considered were sampled and bounded. This mirrors a practical ‘best effort’ book rather than an exhaustive subset-sum solver.

- Particles model: Each buy with amount X is split into many particles with a hard cap satoshis on particle size, with , so . Sell is described as in Section 6.2.

The Particles model dramatically improves liquidity, raising the fraction of perfectly matched orders from 46% to 100%, see Table 2 This validates that order fragmentation increases the probability of fulfilling sell requests with minimal slippage, and long-time exchange becomes more and more liquid, validating the other simulations in Section 6.4.

Table 2.

Fraction of sell orders that can be exactly sastified (matched) by available particles in the pool at the moment of request.

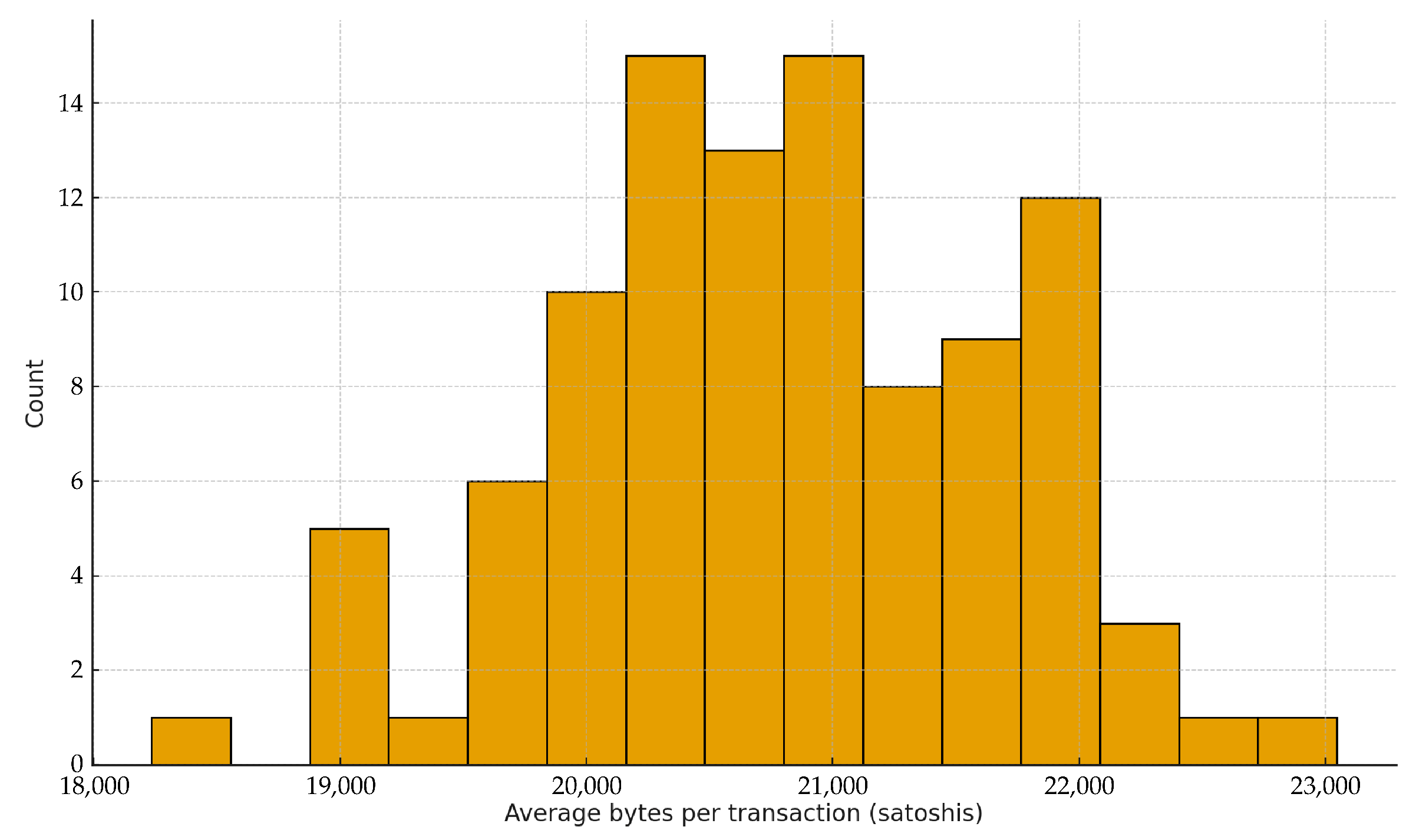

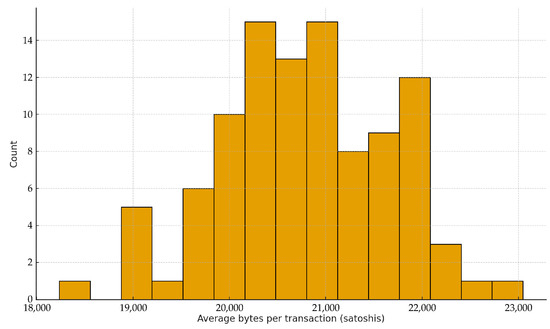

Finally, we validate the theoretical calibration of Section 7.3. Using 50 randomly generated transaction systems, we compute the average transaction cost per system:

- Average transaction cost: 20,789 satoshis (std dev 891 satoshis) ≈ 0.000208 BTC;

- At 1 BTC = 116,069 USD: ≈24.1 USD per transaction.

Figure 14 shows the distribution of per-transaction costs across systems, centered around 20–22 k satoshis. This empirical estimate confirms our earlier theoretical calibration, demonstrating that the system remains economically viable.

Figure 14.

Distribution of average transaction cost (bytes per transaction, i.e. satoshis) across 100 simulated transaction systems. The distribution centers around 20,784 satoshis (USD ≈ 24.1 at BTC = USD 116,069), confirming the theoretical fair price calibration.

9. Conclusions

This paper depicted a method for implementing a proof-of-solvency protocol and a way to enhance privacy on an exchange. Specifically, we attempted to provide concrete practice for proving reserves and liabilities when an exchange’s counterparties are limited to external liquidity providers (other exchanges) and exchange customers. The proposed proof of solvency takes into account two asset categories: (i) cryptocurrency assets, in which case all the transactions are stacked into the blockchain, and are therefore publicly available, and (ii) fiat currency holdings (GBP, EUR, and USD) where the exchange either chooses to prove solvency via receipts (the easiest way but requires usual trust), or tokenize the fiat currency from a stablecoin exchange (which could be state). Where tokenization is implemented, related transactions can be stored into a public blockchain owned by the stablecoin exchange (the blockchain can also be made available for use by other exchanges). For each type of asset, we introduced a protocol for proof of reserves and one for proof of liabilities (including the Liability Tree proposal—see the Section 2.7). These protocols are quite practical but could be further adapted.

As exchanges risk violating user privacy, we proposed a protocol that triggers an explosion of UTXOs (aka particles) of the buy order amount set by a customer, and an implosion gathering ready-made particles into a unique output to the value of a sell order. In this model, i.e., the Particles model, we established conditions for the existence of solutions, calculated the number of solutions, and provided algorithms for practical and efficient solutions’ implementation. Our solutions have the advantages of being intuitive, simple, and consistent. It is worth pointing out that we are providing a methodology for CEX to allow more liquidity. By adding the formula for calculating the fair price, we concluded with a specific calibration that minimizes the fair price. This calibration is an opportunity for a win–win relationship between the exchange and the miners.

From a managerial perspective, the implementation of this proof-of-solvency protocol and privacy-enhancing Particles model offers a pathway to restoring trust in cryptocurrency exchanges, differentiating them in a competitive landscape, and potentially attracting institutional investors who demand higher levels of transparency and security. The ability to provide continuous, verifiable proof of solvency can be a powerful marketing tool, demonstrating a commitment to responsible financial practices and setting a new standard for the industry. Furthermore, the Particles model, by increasing transaction anonymity, addresses growing user concerns about privacy, positioning exchanges as custodians of user data. However, managers must carefully weigh the costs of implementation, including the computational overhead, especially concerning scalability in high-frequency trading environments. Beyond these operational considerations, systemic trust incentives require careful examination. While the protocol aims to increase transparency, ensuring that exchanges are motivated to maintain its integrity and that users are able to effectively verify the provided information remains a key challenge. Further research is needed to explore the design of incentive structures, such as staking mechanisms or reputation systems, that reward honest participation and deter malicious behavior. Finally, the discussion remains open with regard to some regulatory conflicts in terms of governance needed to improve exchange trustworthiness. Future research should focus on refining the cost–benefit analysis of this approach in diverse market conditions and regulatory environments. The exploration of alternative privacy-preserving techniques, such as zero-knowledge succinct non-interactive arguments of knowledge (SNARK/STARK) or secure multi-party computation, and their integration with proof-of-solvency protocols could offer enhanced efficiency and scalability. Research should also investigate the use of automated governance mechanisms to ensure protocol compliance and reduce the risk of manipulation. Finally, developing a standardized framework for proof-of-solvency reporting, perhaps leveraging decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) to oversee implementation and validation, could foster greater consistency and comparability across the cryptocurrency ecosystem. Furthermore, careful consideration must be given to navigating the evolving regulatory landscape to ensure compliance with jurisdictional requirements and avoid potential conflicts with data privacy laws. While a comprehensive comparative analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, several ongoing developments are tackling related challenges. These include advancements in confidential computing, federated learning for fraud detection, and novel approaches to decentralized identity management. Beyond the banking sector, these models have significant potential in supply chain management (ensuring transparency and accountability), healthcare (protecting patient data while enabling data sharing), and voting systems (enhancing security and verifiability). The growing emphasis on blockchain security and privacy is driving demand for professionals skilled in cryptography, smart contract auditing, and decentralized system architecture, suggesting promising future job prospects in these areas. Moreover, expertise in regulatory compliance and risk management within the blockchain space will become increasingly valuable as the industry matures. By rigorously pursuing these avenues of research and development, we can unlock the full potential of blockchain technology to build a more transparent, secure, and equitable financial future for all.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

I extend my deepest gratitude to Michael Hudson from Bitstocks Ltd., whose insightful discussions and unwavering encouragement served as the very spark that ignited the passion behind this work. I dedicate this study to him, with sincere appreciation for the frank motivation he provided to propagate the general Solvency idea.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Julien Riposo is from J.R. Enterprise. The company provided no funding for this research. The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chalkias, K.; Lewi, K.; Mohassel, P.; Nikolaenko, V. Distributed Auditing Proofs of Liabilities; Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 468, 2020. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2020/468.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Proof of Solvency Real Case. Medium-Iconomi, 2018. Available online: https://medium.com/iconominet/proof-of-solvency-technical-overview-d1d0e8a8a0b8 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Dagher, G.; Bnz, B.; Bonneau, J.; Clark, J.; Boneh, D. Provisions: Privacy-Preserving Proofs of Solvency for Bitcoin Exchanges; ACM CCS; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 720–731. [Google Scholar]

- Bateni, H.; Kambakhsh, K. Private Proof of Solvency. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.13900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berentsen, A.; Lenzi, J.; Nyffenegger, R. A Walk-Through of a Simple Zk-STARK Proof. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4308637 (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Ji, Y.; Chalkias, K. Generalized Proof of Liabilities. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 1350, 07/10/2021. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2021/1350 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Riposo, J. Some Fundamentals of Mathematics of Blockchain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, M.; Kumar, E.S.; Lal, C.; Ruj, S. A Survey on Security and Privacy Issues of Bitcoin. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 20, 3416–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhsz, P.L.; Stger, J.; Kondor, D.; Vattay, G. A Bayesian approach to identify Bitcoin users. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Carrion, A.; Rebollo-Monedero, D.; Forn, J.; Campo, C.; Garcia-Rubio, C.; Parra-Arnau, J.; Das, S.K. Entropy-Based Privacy against Profiling of User Mobility. Entropy 2015, 17, 3913–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.-G.; Ding, H.-F.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Tian, Y.; Fu, Z.-F. Information entropy models and privacy metrics methods for privacy protection. J. Softw. 2016, 27, 1891–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liang, Z.; Lyu, Q. Empowering Privacy Through Peer-Supervised Self-Sovereign Identity: Integrating Zero-Knowledge Proofs, Blockchain Oversight, and Peer Review Mechanism. Sensors 2024, 24, 8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Fang, J.; Hong, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, J.; Liang, C.; Zhao, G.; Tang, H. Privacy Protection Method for Blockchain Transactions Based on the Stealth Address and the Note Mechanism. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ma, J. Towards Building a Faster and Incentive Enabled Privacy-Preserving Proof of Location Scheme from GTOTP. Electronics 2024, 13, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Shao, Y. Research on Blockchain Transaction Privacy Protection Methods Based on Deep Learning. Future Internet 2024, 16, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. A Universal Privacy-Preserving Multi-Blockchain Aggregated Identity Scheme. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I.; Eckhoff, D. Technical Privacy Metrics: A Systematic Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]