Abstract

Allergic rhinitis and asthma remain major public-health challenges, with airborne pollen serving as a key environmental driver. This study investigates the temporal association between aeroallergen exposure, patient healthcare utilization, and allergy medicine consumption at the MNIT Jaipur dispensary from 2015 to 2020, focusing on Holoptelea integrifolia pollen as a primary allergen. Patient visit data and medicine issuance records were analyzed to evaluate seasonal co-trends using descriptive time-series and statistical tests, including Pearson correlation and Mann–Whitney U. The analysis revealed consistent peaks in both patient visit and medicine issuance during February–April, corresponding with H. integrifolia pollen release, and secondary peaks during August–September and October, coinciding with Amaranthus spinosus, Parthenium hysterophorus, and monsoon mold activity. A moderate positive correlation (r = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.22–0.79, p = 0.007) and significant differences between high- and low-patient months (U = 107.5, p = 0.043, 95% CI of difference: 1323–3620 units) indicating that increased healthcare utilization coincides with seasonal aeroallergen exposure. These findings highlight the potential of medicine consumption data as a cost-effective proxy for allergen surveillance, aiding early warning and preparedness for seasonal allergy management. Integration of such pharmaco-epidemiological insights with dispersion models may strengthen predictive frameworks for pollen exposure and public-health response.

1. Introduction

Allergic rhinitis and asthma represent major public-health burdens globally, with pollen identified as one of the most significant aeroallergens contributing to morbidity [1,2]. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) has highlighted a rising prevalence of allergic conditions across low- and middle-income countries, including India, where urbanization and vegetation changes exacerbate exposure risks. In India, Holoptelea integrifolia (Indian Elm) pollen is a recognized aeroallergen, with sensitization rates exceeding 25% among allergic patients in northern regions [3]. Pollen release from this species typically occurs from February to April, coinciding with seasonal surges in patient presentations for respiratory and allergic complaints.

Clinical guidelines provide strong evidence that early recognition and effective management of allergic rhinitis and asthma are critical for reducing exacerbation and associated healthcare burden. The Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma, ARIA 2020 guidelines [4] emphasize the value of real-time symptoms and medication surveillance for anticipating healthcare demand and informing public-health responses during peak allergen periods. Similarly, the Global Initiative for Asthma [5] highlights that seasonal aeroallergen exposure is a major driver of exacerbation spikes and recommends proactive monitoring to support preparedness strategies. Incorporating such principles into resource-limited settings is especially relevant where continuous aerobiological monitoring infrastructure is lacking.

Pharmaco-epidemiological studies increasingly demonstrate that allergy medicine consumption—both over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription—serves as a sensitive indicator of pollen-related healthcare burden. In New York City, OTC allergy medication sales were shown to peak approximately nine days before asthma-related emergency department (ED) visits, suggesting that medication purchases act as a leading indicator of hospital demand during high-pollen episodes [6]. A companion study confirmed a strong short-term association between tree pollen exposure and daily OTC medication sales, with sales increasing by nearly 29% within two days of pollen peaks and significant cumulative effects over one week [7]. Extending this approach to multiple U.S. cities, [8] found that tree, weed, and grass pollen exposure significantly elevated both outpatient physician visits for allergic rhinitis and prescription fills, underscoring the coherence of medication consumption and healthcare utilization metrics. Evidence from other geographical contexts reinforces this link. In Beijing, peaks in hospital outpatient prescriptions for antihistamines, leukotriene receptor antagonists, nasal sprays, and short-acting β-agonists corresponded directly with spring and autumn pollen maxima [9]. Earlier European time-series analyses also reported short-term rises in anti-allergic drug sales following pollen exposure, highlighting the utility of medication data for surveillance. Although some studies are geographically restricted or limited to single data sources (e.g., urban pharmacies or single tertiary hospitals), the consistency of findings across diverse healthcare settings indicates that medication consumption reflects both self-care behavior and subsequent clinical demand. Importantly, such consumption trends often precede peaks in clinical encounters, providing a valuable tool for forecasting healthcare burden and strengthening early warning systems during pollen seasons.

In the Indian context, few studies have quantified the direct association between pollen exposure, patient visits, and drug consumption. Existing aerobiological surveys provide pollen calendars and prevalence estimates [10,11], but robust pharmaco-epidemiological analyses remain sparse. This study therefore investigates whether patient visits and allergy medicine consumption at the MNIT Jaipur dispensary follow seasonal trends consistent with aeroallergen exposure, focusing particularly on Holoptelea integrifolia during February–April.

2. Data Sources and Availability

The analysis draws on two primary datasets from the MNIT dispensary, covering 2015 to 2020, which span pre- and post-COVID periods, enabling examination of demographic shifts (predominantly students pre-COVID, staff in 2020 due to campus closures). The 2020 data are influenced by COVID-19 lockdowns, which reduced patient visits in March–April. Medicine issuance is assumed to reflect consumption, as new stock is issued only after depletion, allowing temporal alignment with patient visits.

2.1. Patient Visit Records

Patient footfall data, recorded daily from January 2015 to December 2020, provide monthly aggregates of dispensary visits. These records capture total patient counts per month (e.g., 1838 in January 2015, 3833 in February 2020), with non-numeric entries (e.g., “Public Holiday”) standardized to zero for consistency.

2.2. Medicine Consumption Records

Medicine issuance logs document the quantity and date of allergy-related medicines dispensed, including antihistamines (e.g., Cetirizine, Levocetirizine), leukotriene receptor antagonists (e.g., Montelukast), and combination drugs (e.g., Cheston Cold). Data are available from April 2018 to December 2020, with no records for 2015 to early 2018, limiting full temporal alignment with patient data. Each entry includes the medicine name, quantity issued (in tablets, syrups, or units) to the doctor by the storekeeper, and issuance date, serving as a proxy for consumption.

Table 1 below shows the earliest and latest dates for which valid allergy-related medicine data is available:

Table 1.

Availability of medicine consumption data at MNIT Jaipur Dispensary.

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Medicine

To align with the hypothesis of pollen-driven allergies, the analysis focuses on medicines pharmacologically relevant to allergic and respiratory symptoms, including antihistamines, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and select corticosteroids. Included medicines, such as Cetirizine, Montelukast, Levocetirizine, Avil, Atarax, and Cheston Cold, target allergic rhinitis, asthma, and urticaria. Medicines like Asthalin (salbutamol) and Budicort (budesonide), primarily for non-allergic asthma, and non-specific drugs (e.g., Kuffdryl Syp) were excluded, based on their limited relevance to pollen-induced allergies [12,13]. Only medicines listed in Table 2a were included in the statistical analysis; excluded medicines listed in Table 2b were removed prior to aggregation.

Table 2.

(a) Reasoning for inclusion of medicine in the study. (b) Reasoning for exclusion of medicine from the study.

2.4. Data Processing

Patient visit data were aggregated monthly from 2015 to 2020 to identify seasonal trends, with daily counts cleaned to ensure numerical consistency. Medicine issuance quantities were aggregated by month and year for included medicine, using issuance dates to align with patient visits. Due to the temporal mismatch (patient data: 2015–2020; medicine data: 2018–2020), the analysis is bifurcated:

- Descriptive Time Series (2015–2020): Examines patient visit trends across all years to identify seasonal peaks.

- Correlation and Co-Trend Analysis (2018–2020): Merges patient visits and medicine issuance for the overlapping period, using line plots and statistical tests (Pearson correlation, Mann–Whitney U) to assess relationships, particularly during February–April.

This approach maximizes data utilization while acknowledging limitations in historical medicine records.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Temporal Trends in Patient Footfall and Medicine Issuance

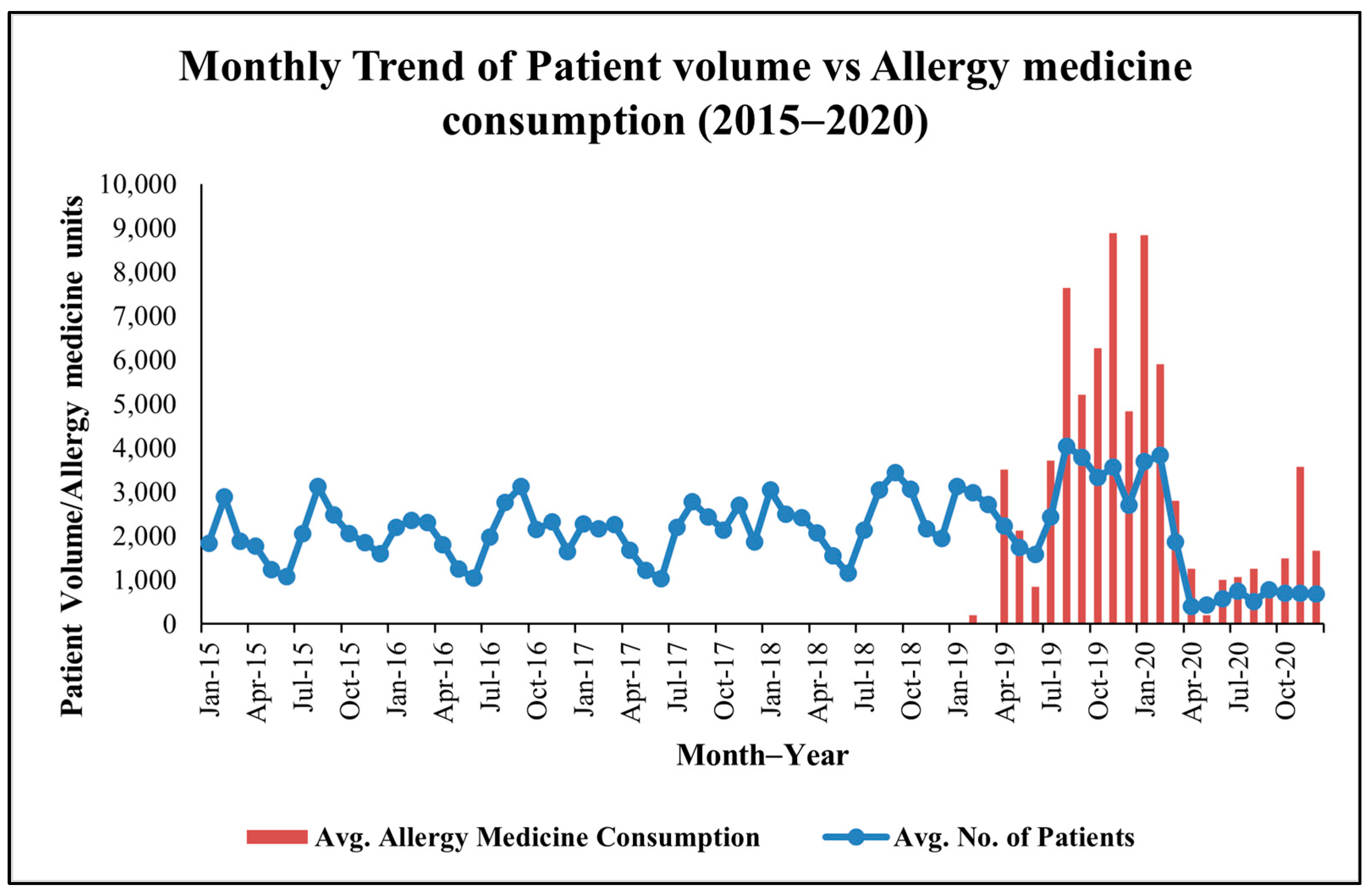

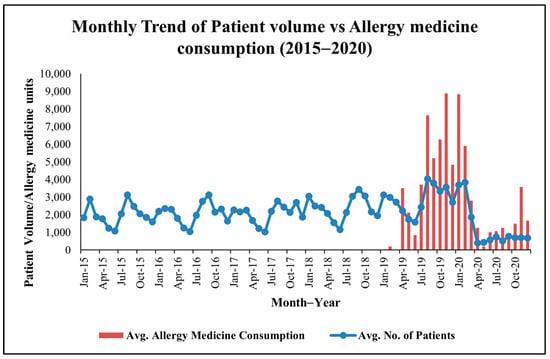

Patient visit data exhibit significant monthly variability, with consistent peaks (see Figure 1) in February–March (e.g., 2888 patients in February 2015, 3833 in February 2020) and August–September (e.g., 4041 in August 2019, 3792 in September 2019), suggesting seasonal health challenges. These periods align with the Holoptelea integrifolia pollen season (February–April) and potential monsoon-related triggers (e.g., Amaranthus spinosus pollen, mold spores) in August–September [14]. A sharp decline in April 2020 (405 patients) reflects COVID-19 lockdown effects.

Figure 1.

Monthly co−trend of patient visits and allergy−related medicine consumption data at MNIT Jaipur Dispensary.

Medicine issuance data, available from April 2018 to 2020, show corresponding peaks (see Figure 1) in February–April (e.g., 3100 units in March 2019) and August–September (e.g., 3200 units in September 2019). These trends suggest pollen-driven allergies during the Holoptelea integrifolia season and additional environmental triggers, such as Amaranthus spinosus pollen and monsoon molds later in the year.

Across 2018–2020, the median monthly patient visit count was 2564 (IQR: 1982–3044), while median monthly allergy-related medicine issuance was 2310 units (IQR: 1188–3625), establishing a quantitative baseline for subsequent correlation and hypothesis testing.

3.2. Analysis of Medicine-Specific Trends

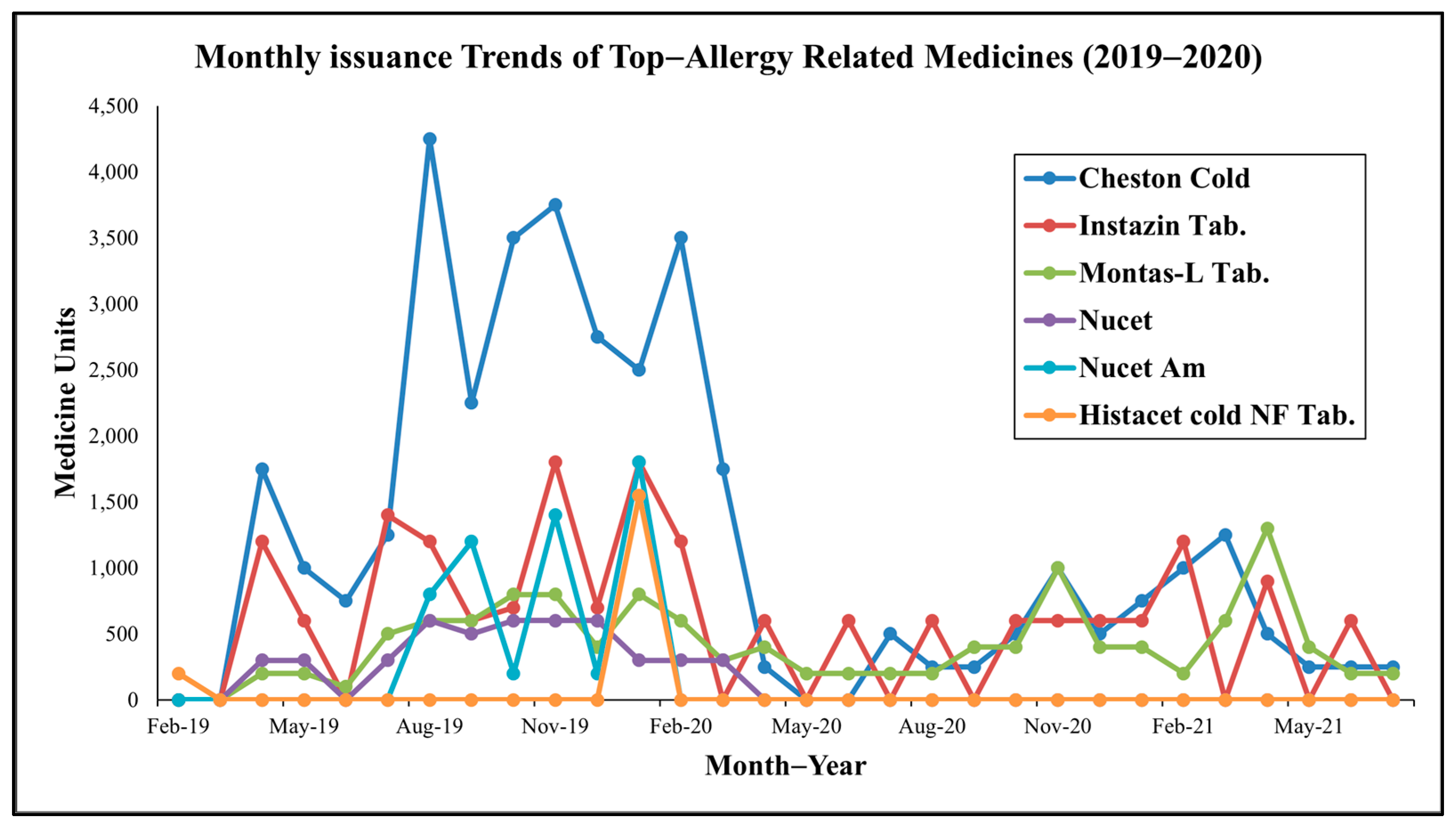

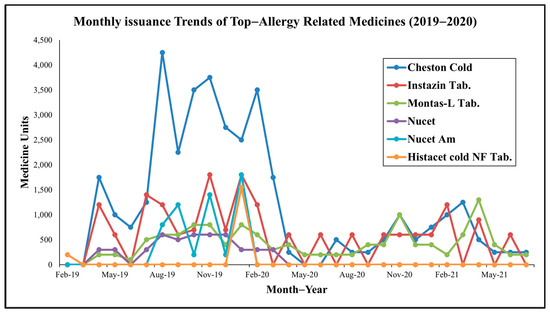

Analysis of medicine-specific trends (see Figure 2) reveals further insights. Montas-L Tab (montelukast + levocetirizine), a leukotriene receptor antagonist and antihistamine combination, was the most consistently dispensed drug, reflecting its efficacy in managing allergic rhinitis and asthma [15,16]. Nucet and Instazin (cetirizine-based antihistamines) showed pronounced seasonal peaks, while Cheston Cold (cetirizine + paracetamol + phenylephrine) and Dexona (dexamethasone), though non-specific, aligned with high-patient months, likely addressing inflammatory or respiratory symptoms.

Figure 2.

Monthly trends of top allergy-related medicine consumption at MNIT Jaipur Dispensary.

Notably (see Table 3), July peaks in Montas-L, Nucet, and Asthalin (salbutamol) correspond to monsoon-related mold proliferation or Amaranthus spinosus pollen, while October increases in Montas-FX (montelukast + fexofenadine), Atarax (hydroxyzine), and L-zine (levocetirizine) align with post-monsoon weed growth, such as Parthenium hysterophorus, a potent allergen [17]. November and December surges (e.g., Dexona Inj, Montas-L Kid, antihistamines) suggest winter-related triggers like cold air and increased particulate matter in ambient air.

Table 3.

Noteworthy peaks in other months.

These multi-phasic trends indicate reactive prescribing in response to diverse aeroallergen exposures, extending beyond Holoptelea integrifolia pollen to include weeds, grass and molds, supporting the hypothesis of a year-round allergic burden.

The observed seasonal medicine consumption patterns align closely with global management recommendations. ARIA guidelines [4] advocates anticipatory planning for peak allergy seasons and recognizes pharmacological demand trends as valuable markers for population-level burden. GINA guidelines [5] similarly identifies pollen exposure as a significant trigger for asthma exacerbations and supports preventive intervention strategies, including adequate stockpiling of antihistamines, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and inhaled corticosteroids during high-risk periods. The convergence of our healthcare utilization data with these guideline principles reinforces the clinical utility of medicine-consumption-based surveillance in low-monitoring environments.

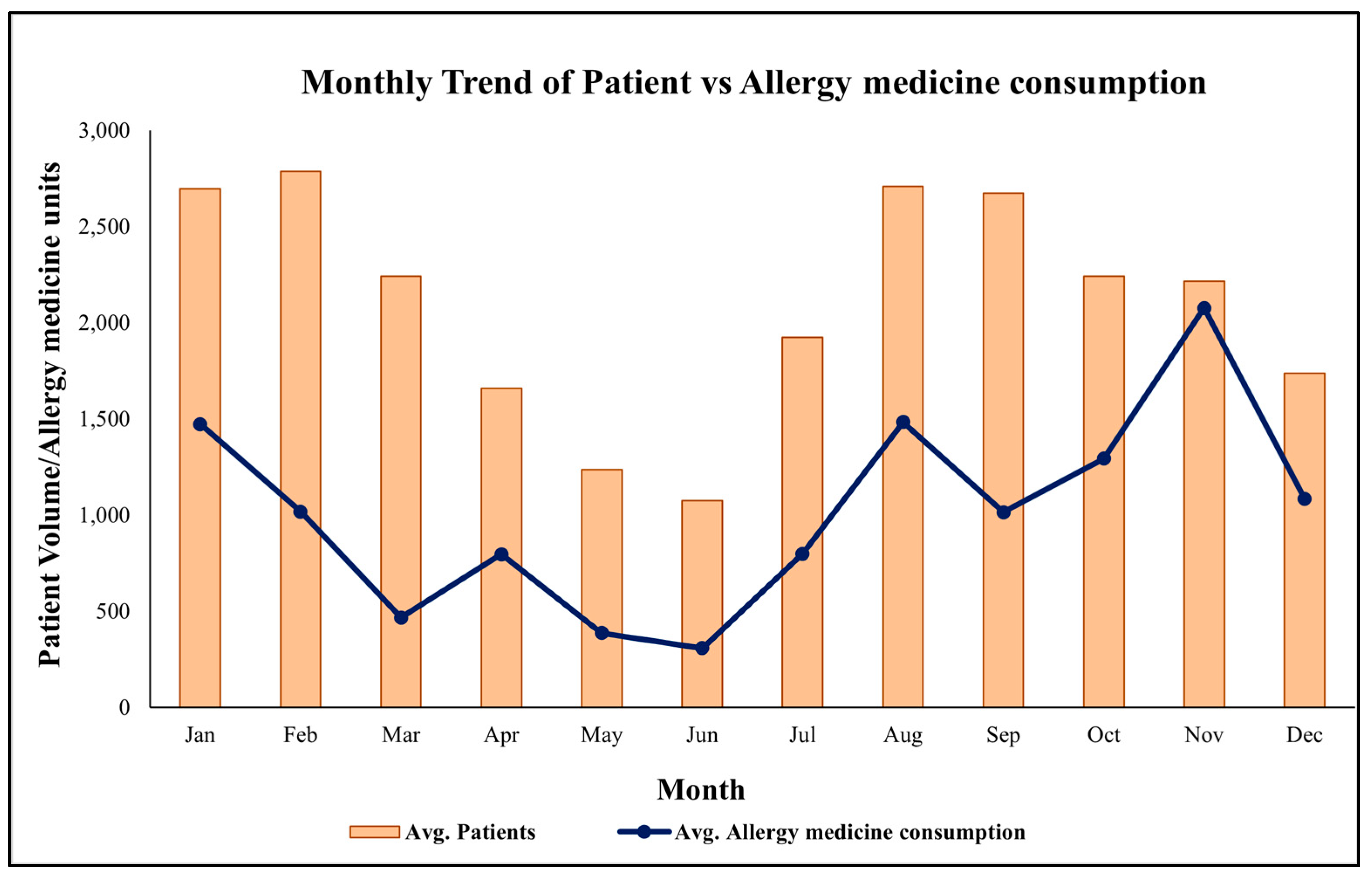

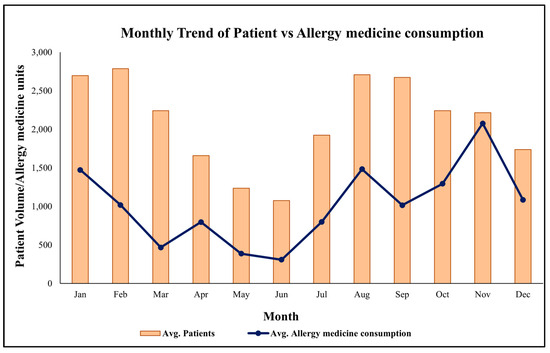

3.3. Merged Patient–Medicine Trends

To explore the association between health service utilization and allergy treatment, monthly patient visits (2018–2020) were merged with medicine issuance data for anti-allergy drugs (e.g., Cetirizine, Montelukast). This integrated dataset enabled joint visualization and statistical analysis (see Figure 3). Periods of elevated patient visits corresponded closely with increased medicine issuance, particularly during February–April, but also in August–September and October, suggesting multiple allergen exposures, including Holoptelea integrifolia pollen, Amaranthus spinosus, Parthenium hysterophorus, and monsoon molds [14].

Figure 3.

Average monthly trend of patient and allergy-related medicine consumption at MNIT Jaipur Dispensary.

3.4. Correlation Between Patient Count and Medicine Issuance

The Pearson correlation coefficient between patient visits and medicine issuance was r = 0.58 (95% CI: 0.22–0.79, p = 0.007), indicating a statistically significant moderate positive relationship. This suggests that higher patient footfall, particularly during pollen seasons, drives increased consumption of allergy-related medicines.

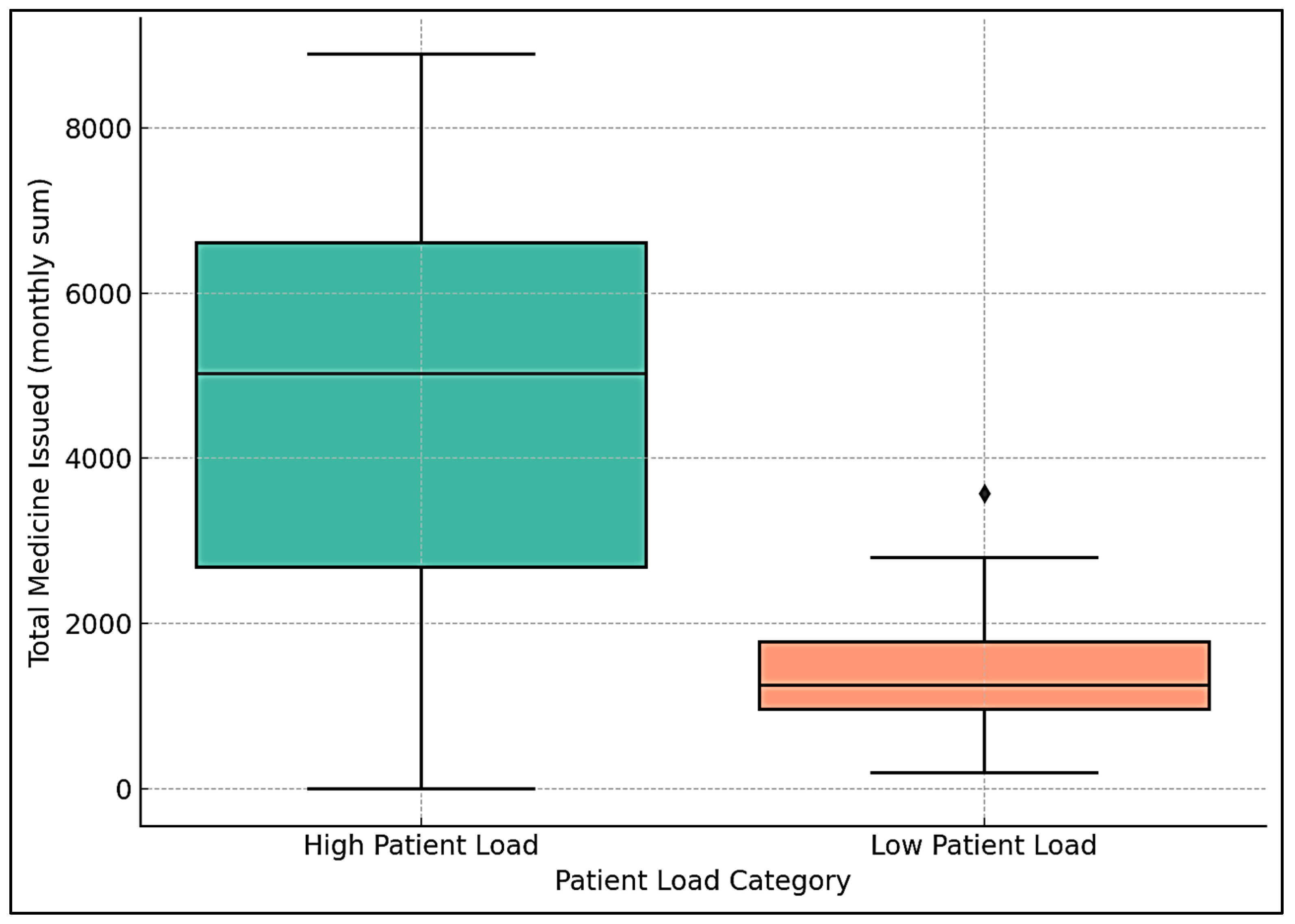

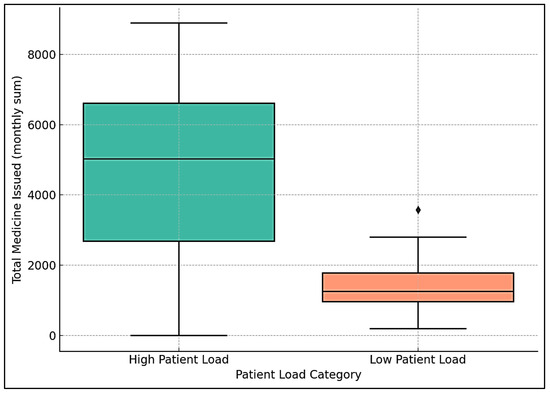

3.5. Hypothesis Testing: Medicine Use in High- vs. Low-Patient Months

To further investigate this relationship, a Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare medicine issuance in high- versus low-patient months, defined as above or below the median patient visits. High-patient months had a mean medicine issuance of 4585 units, compared to 1516 units in low-patient months (see Figure 4). The test yielded a U-statistic of 107.5 (p = 0.043, 95% CI of difference: 1323–3620 units), indicating a statistically significant difference.

Figure 4.

Box plot of high- and low-patient months.

A box plot showed a higher median and wider interquartile range for medicine issuance in high-patient months, compared to a lower median and reduced demand in low-patient months. This supports the correlation findings, indicating that increased patient visits, likely driven by seasonal allergies, are associated with greater medicine consumption.

4. Limitations

This study did not incorporate confounder controls such as meteorological variables (temperature, relative humidity, rainfall, and PM2.5), which are known to influence respiratory health and pollen dispersion. The absence of concurrent direct pollen count measurements limits causal attribution. Future modeling should incorporate these meteorological covariates to improve attribution strength. Additionally, the year 2020 was affected by COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, which significantly reduced outpatient visits in March–April and likely underestimated seasonal peaks.

5. Conclusions

Patient visits and allergy-related medicine consumption at the MNIT dispensary coincided with seasonal patterns consistent with Holoptelea integrifolia pollen release, with secondary peaks during monsoon and post-monsoon periods, suggesting a complex interplay of aeroallergens, including pollen from Parthenium hysterophorus, Amaranthus spinosus and monsoon molds. The moderate correlation (r = 0.58, p = 0.007) and significant Mann–Whitney U test results (U = 107.5, p = 0.043) underscore the public-health impact of environmental triggers on the MNIT campus. These findings are robust for 2018–2019, though 2020 data are skewed by COVID-19 restrictions.

These findings suggest an influence of seasonal aeroallergens and highlight the potential utility of routine dispensary records as proxy indicators of aeroallergen-related healthcare burden in regions lacking continuous pollen monitoring. These results have practical implications for health system preparedness, such as stockpiling antihistamines and leukotriene antagonists during peak seasons and exploring campus greening strategies to reduce allergenic flora. The data also supports AERMOD modeling by providing empirical evidence of pollen-driven healthcare utilization, leveraging tree characteristics to estimate pollen emission rates [18]. Future research should incorporate direct pollen measurements and detailed patient demographics to refine these insights.

Author Contributions

R.P.S.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. S.K.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization. A.B.G.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Original unprocessed data will be shared on reasonable requests after approval from the MNIT Jaipur dispensary.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of MNIT Jaipur dispensary for their assistance in providing access to their medical records.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ISAAC | International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood |

| MNIT | Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur |

| OTC | Over-the-Counter (medication) |

References

- Asher, M.I.; Montefort, S.; Björkstén, B.; Lai, C.K.; Strachan, D.P.; Weiland, S.K.; Williams, H. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006, 368, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthma. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Singh, A.B.; Kumar, P. Aerial pollen diversity in India and their clinical significance in allergic diseases. Ind. J. Clin. Biochem. 2004, 19, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, J.; Schünemann, H.J.; Togias, A.; Bachert, C.; Erhola, M.; Hellings, P.W.; Klimek, L.; Pfaar, O.; Wallace, D.; Ansotegui, I.; et al. Next-generation Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines for allergic rhinitis based on Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) and real-world evidence. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 70–80.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Asthma. GINA Report, 2024. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Available online: https://ginasthma.org (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Ito, K.; Weinberger, K.R.; Robinson, G.S.; Sheffield, P.E.; Lall, R.; Mathes, R.; Ross, Z.; Kinney, P.L.; Matte, T.D. The associations between daily spring pollen counts, over-the-counter allergy medication sales, and asthma syndrome emergency department visits in New York City, 2002–2012. Environ. Health 2015, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheffield, P.E.; Weinberger, K.R.; Ito, K.; Matte, T.D.; Mathes, R.W.; Robinson, G.S.; Kinney, P.L. The Association of Tree Pollen Concentration Peaks and Allergy Medication Sales in New York City: 2003–2008. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 537194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuhrman, C.; Sarter, H.; Thibaudon, M.; Delmas, M.C.; Zeghnoun, A.; Lecadet, J.; Caillaud, D. Short-term effect of pollen exposure on antiallergic drug consumption. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007, 99, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Y.; Tian, Z.-M.; Ning, H.-Y.; Wang, X.-Y. The ambient pollen distribution in Beijing urban area and its relationship with consumption of outpatient anti-allergic prescriptions. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.B.; Kumar, P. Aeroallergens in clinical practice of allergy in India. An overview. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2003, 10, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.B.; Shahi, S. Aeroallergens in clinical practice of allergy in India- ARIA Asia Pacific Workshop report. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2008, 26, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.B. Pollen and Fungal Aeroallergens Associated with Allergy and Asthma in India. Glob. J. Immunol. Allerg. Dis. 2014, 2, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Shahi, S.; Katiyar, R.K.; Gaur, S.; Jain, V. Hypersensitivity to pollen of four different species of Brassica: A clinico-immunologic evaluation in patients of respiratory allergy in India. Asia Pac. Allergy 2014, 4, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, R.P.; Khandelwal, S.; Gupta, A.B.; Singh, N.; Singh, V. Exploring the correlation between airborne pollen levels and respiratory conditions in Jaipur, India. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2025, 35, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, M.; Mohd Noor, N.; Mat Lazim, N.; Abdullah, B. Efficacy of Montelukast in Allergic Rhinitis Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Drugs 2020, 80, 1831–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwaskar, M.; Kamdar, B.J.; Prabhudesai, P.P. Montelukast: A Scientific and Legal Review. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2025, 73, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhateria, R.; Renu, D.; Snehlata. Parthenium hysterophorus L.: Harmful and beneficial aspects—A review. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2015, 14, 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Grell, G.A.; Emeis, S.; Stockwell, W.R.; Schoenemeyer, T.; Forkel, R.; Michalakes, J.; Knoche, R.; Seidl, W. Application of a multiscale, coupled MM5/chemistry model to the complex terrain of the VOTALP valley campaign. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 1435–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.