Abstract

The Danish asbestos executive order defines a range of situations and work processes that require no protective measures, due to an assumption of low dust generation and therefore negligible exposure to asbestos fibers. The purpose of the study was to investigate the exposure of workers performing tasks where low dust generation is assumed, as well as those in direct proximity. Five roof renovation projects, one facade removal project, and one removal project of whole pipes with intact asbestos insulation were included in the study. A total of 52 personal samples and 33 stationary samples were collected. The asbestos fiber concentrations measured in personal samples ranged from below the detection limit to 0.13 f/cm3 (fibers/cm3). Despite the large spread between projects, the measured concentrations of asbestos fibers in 45 of the 52 personal samples were above the Danish occupational exposure limit value (OEL) of 0.003 f/cm3. The concentration of asbestos fibers in 20 of 33 stationary samples was also above the Danish OEL. The results of personal and stationary measurements suggest that any work with asbestos-containing materials may be associated with a significant risk of exposure above the OEL and, thus, should not be considered a low-dust-generating process without measurements.

1. Introduction

Asbestos is a group of naturally occurring fibrous materials. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), asbestos fibers with length L > 5 µm, diameter D < 3 µm, and size ratio L:D > 3:1 are dangerous when inhaled or ingested. Exposure can cause a number of diseases, such as lung, larynx, and ovarian cancer, mesothelioma, and asbestosis [1,2].

Peak asbestos consumption in Denmark took place in the early 1970s, with annual imports of 30,000 tons of asbestos. Asbestos imports first began to decline in connection with the ban on asbestos in insulation materials in 1972 and, later, sharply with the near-total ban in 1986 [3]. The first working environment limit value for asbestos in the air was introduced in the 1970s (an average of 2 f/cm3 per 8 h shift). It was then lowered several times, first to 1 f/cm3, then to 0.5 f/cm3, followed by 0.3 f/cm3 and, in 2005, to 0.1 f/cm3. In 2022, the limit was flowered even further and now stands at 0.003 f/cm3.

Fonseca et al. [3] looked at historical exposure to asbestos fibers in the Danish working environment. The analysis of 5869 historical measurements taken between 1971 and 1997 showed a geometric mean concentration of asbestos fibers in the air between 0.003 f/cm3 and 35 f/cm3, depending on occupation type and task. Production of asbestos-containing products, such as asbestos cement sheets, insulation materials, and materials for the automotive industry, was associated with the highest risk, especially in the period of 1971 to 1980, when values as high as 103 f/cm3 were measured. Later, the highest concentrations were measured during active handling of asbestos products in the construction sector, such as in the removal of asbestos-containing floors and ceilings. All measurements carried out without or outside a protective mask were above 0.1 f/cm3, i.e., above the current limit value of 0.003 f/cm3 [4].

As the production and use of asbestos and asbestos-containing materials are now prohibited, demolition and maintenance workers are among the groups at greatest risk of exposure. Already in 1987, Brown [5] published results of personal measurements taken during the renovation and demolition of buildings containing asbestos cement materials. He reported average concentrations during the demolition of asbestos roofs between 0.3 and 0.6 f/cm3. Similar concentrations were measured in a Polish study carried out between 2000 and 2007 involving the removal of asbestos-containing façade panels and roof sheets [6]. The average concentration of asbestos fibers in personal and stationary measurements was 0.31 f/cm3 (range: 0.03–0.90 f/cm3) and 0.20 f/cm3 (range: 0.03–0.52 f/cm3), respectively. Results of personal measurements from Tehran, Iran [7] were at a similar level, with an average Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) concentration of 0.20 f/cm3 (0.02–0.36 f/cm3) and an average Phase Contrast Microscopy (PCM) concentration of 0.07 f/cm3 (0.01–0.15 f/cm3)

Obminski et al. [8] investigated the effectiveness of different fiber binders on the concentration of asbestos fibers during brush grinding of asbestos cement roof sheets. The study showed a relatively large spread in efficiency of the examined fiber binders, which varied from 35% to 96%, compared to non-sealed sheets. Despite the high efficiency of some of the tested products, the release of fibers was still high. All asbestos roof sheets selected for the study were visually assessed to be in good condition. However, half of them were, in fact, not up to standard when assessed using the abrasion test. This emphasizes that visual inspection can be misleading when assessing the condition of asbestos-containing materials. As further shown by Ervik et al. [9], loose fibers can be expected on the surface of asbestos cement roofs as a result of weathering.

In §5 of the Danish asbestos executive order [10], a range of situations and work types are defined that require no protective measures against asbestos exposure due to an assumption of low dust generation and therefore negligible asbestos fiber exposure. Removal of undamaged materials without destroying them, if the asbestos fibers are tightly bound together in a matrix, is one of the processes listed in the executive. In practice, this includes the removal of asbestos cement roofing sheets and facade plates. The purpose of this study was therefore to assess asbestos fiber exposure of workers performing tasks where low dust generation is assumed, as well as exposure of workers performing other tasks in direct proximity.

2. Materials and Methods

Despite the assumption of low dust generation in the selected working processes, only projects where workers wore personal protective equipment, including Turbo—masks, were invited to take part in this study. The personal samples were, however, taken outside the mask, simulating the exposure of an unprotected worker. To minimize the impact of weather (wind, rain) on the results and to prevent the spread of fibers into the surrounding environment, we only included projects where roof removal was conducted in enclosed spaces, i.e., buildings covered with scaffolding and top-roofs tightly wrapped in plastic and with negative pressure in the working area. Façade work was not performed in an enclosed space.

2.1. Selection of Working Processes

The selected processes included the removal of roofing sheets, the removal of facade panels, the removal of pipes partially covered with asbestos insulation, and the drilling of holes in tiles covered with asbestos-containing tile adhesive. As we only managed to perform one measurement while drilling holes in tiles covered with asbestos-containing tile adhesive, this process was not included in the paper but presented in the Danish report summarizing all the collected data [11].

Removal of asbestos cement roofing sheets was the focus of the project, as this type of work is generally carried out in Denmark as a low-dust-generating process. When removing roof sheets, the underlying surfaces, which are often covered with asbestos-containing dust (Figure 1), are opened up. Although removal of underlying insulation and removal of laths do not directly fall under §5 of the Danish executive, they are often inseparable processes in the demolition of asbestos roofs. Where possible, the two processes, i.e., removal of asbestos sheets and removal and packing of the underlying insulation, were split up. This was not possible in the case of the removal of facades, as the working process included the simultaneous removal of facade plates and the underlying insulation.

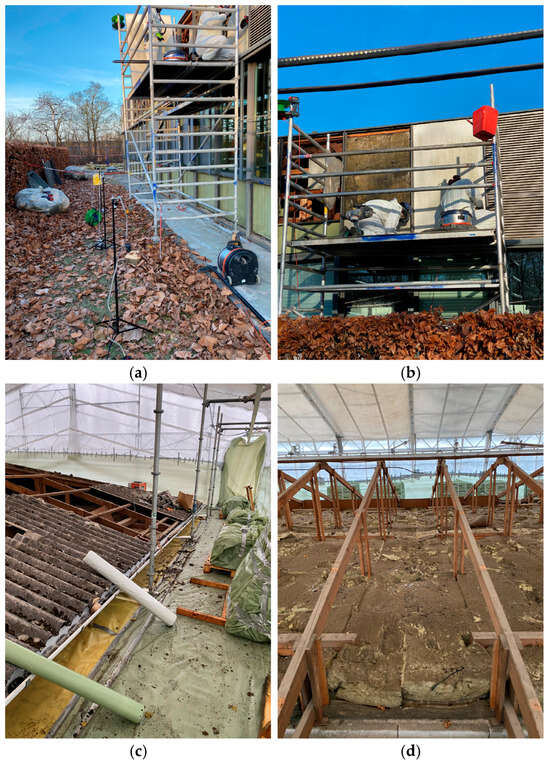

Figure 1.

Measuring set up and conditions during removal of facade panels (a,b) and roofing sheets and underlying insulation (c,d). (a) Stationary samples during the removal of facade panels. (b) Personal samples conducted on workers during the removal of facade panels with underlying insulation. (c) Working area during the removal of roofing sheets. The roofing plates covered with moss. (d) A large amount of asbestos-containing dust on the top of the insulation after removing the roof.

The roof tiles are normally loosened and removed by sliding them down the roof surface from top to bottom, directly on top of the other tiles. The stacks of plates are later packed into plastic bags. In order to assess whether changing the working methodology could reduce dust generation, an artificial scenario was set up in one of the projects, where four employees were asked to handle roof tiles as gently as possible by lifting them up and carrying them down one at a time. In another project, the use of a fiber binder to prevent dust generation was investigated.

The removal of pipe installations covered partially in asbestos was assumed not to release asbestos fibers, as the cutting points were located on asbestos-free parts of the pipes. As a supplementary protective measure, the asbestos-containing insulation material was wrapped in plastic foil and sealed with tape on both ends.

2.2. Personal and Stationary Samples

Exposure of workers undertaking asbestos-containing tasks was investigated using personal sampling. Sampling of asbestos fibers was performed by collecting dust from the air on gold-coated filters (TJ Environmental, Hilversum, The Netherlands) using SKC Leland Legacy Pump (Blandford Forum, UK) air pumps with a flow of 3–5 L/min. Filters were mounted outside the mask, at the workers’ breathing zone, while the pump was mounted on a belt at the back, to avoid disturbing the workers as much as possible. Flow was measured before and after sampling. On average, there was a 4% drop in the flow measured after sampling compared to before sampling. In some cases, the difference was higher due to filter overload (up to 30%). Average values taken before and after sample readings were used to calculate the sample volume. Depending on the exposure scenario, collection was carried out during the entire working time (six hours as permitted when using Turbo-masks) or during shorter periods of two hours of uninterrupted work. The latter was often chosen in connection with roof cases, as the filters quickly became overloaded due to heavy dust generation. The total expected exposure time was set at eight hours (two hours break-time with zero exposure and six hours with the measured exposure).

Stationary sampling was carried out in parallel with personal sampling in the areas where the asbestos work was carried out. These samples represent the exposure of other workers who may have been present in the vicinity but were performing a different task. Stationary sampling was carried out by collecting dust from the air on MILLIPORE (0.8 µm; Millipore, Sigma Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) filters at a flow of 10–15 L/min. Usually, three pumps were placed in the area, just behind the workers, on the left and on the right side of the working area, all approximately 1 m from the asbestos-containing material and approximately 1.5 m above the ground.

2.3. Laboratory Analysis of Air Samples

Two methods were selected for the analysis of air samples. All stationary samples were analyzed with the PCM method, which is the most common in Denmark. The SEM method was used for personal samples because of the use of smaller pumps with lower airflows and to avoid overestimation of fiber concentrations due to possible contamination of samples with other fibers and particles.

2.3.1. PCM Method

The PCM (Phase Contrast Microscopy) method is not asbestos-specific. All fibers with length L > 5 µm, diameter D < 3 µm, and size ratio L:D > 3:1 are counted. Furthermore, the method cannot identify fibers with D < 0.2 µm. The continuous fall in limit value over the years and the fact that working environments often have a variety of different fibers in the air present challenges to the PCM method. PCM is, however, a relatively cheap method; it is standardized with many years of experience and is still recommended in several working guidelines, including the Danish asbestos executive order.

PCM analyses were carried out in our own laboratory. The fiber counts were carried out according to DS 2169 [12] and the Danish asbestos executive order [4]. Procedures not covered by these were taken from NIOSH 7400 [13]. The analysis was performed at 400× magnification on a Diaplan light microscope with fitted phase contrast equipment. The fibers were counted according to the criteria in NIOSH 7400 (WHO counting criteria). If fewer than 10 (+blank value) PCM fibers/100 fields were counted, counting continued up to 200 fields, which corresponds to 0.4% (1.57 mm2). The blank value was deducted when calculating the fiber concentration, but was not deducted from the fiber count number listed in the results form. Based on the air volume of 1500 L (12.5 L/min for 2 h) and the number of analyzed fields of the filters (200 fields corresponding to 0.4% of the filter area), the limit of detection (LOD) was estimated to be 0.0008 f/cm3. The concentration and 95% confidence interval mean count were estimated according to NIOSH 7400, assuming Poisson distribution [13]. If the net fiber count was below five fibers, the result was indicated below the statistical detection limit. For net fiber counts of five and above, the result was stated, and the theoretical confidence interval and detection limit were given.

The laboratory currently finds, on average, 0 PCM fibers/100 fields in blind and field blind counts.

2.3.2. SEM Method

The SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) method, combined with Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis (EDXA), can identify fibers with D < 0.2 µm and identify asbestos fibers based on their mineral composition, i.e., distinguish between asbestos and non-asbestos fibers. However, detection and identification of fibers become progressively more uncertain as the fiber width is reduced below 0.2 µm. As described above, the concentration of fibers in personal samples was expected to be lower as a result of lower flow on the collection equipment. Furthermore, the presence of non-asbestos dust and dirt generated during work was expected, which could hide the presence of very fine asbestos fibers and hinder their detection by the PCM method. The SEM method combined with EDXA was therefore the method of choice for personal sampling.

The analysis of personal air samples was carried out by an accredited subcontractor (CRB Analyse Service GmbH, Hardegsen, Germany). The analyses were conducted according to VDI 3492:2013-06. With 480 L of air collected (2 h, 4 L/min), the laboratories detection limit was 0.0023 fibers/cm3.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data collected during the removal of asbestos cement roofing sheets and underlying insulation were not normally distributed. All results are shown as geometric means, and minimum and maximum values are given. The difference between projects and processes was tested with an independent samples Kruskal–Wallis test for comparison of multiple groups and a Mann–Whitney U test for comparison of two groups. We used half the limit for data below LOD. The significance threshold was p < 0.05, and all analyses were performed in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0.2.0 for Windows).

3. Results and Discussion

A total of 33 stationary samples for PCM analysis and 52 personal samples for SEM analysis were collected during five different asbestos removal projects in the period from 1 March to 31 October 2023. The personal and stationary samples were taken at the same time. We did not perform stationary sampling during the process of cutting vertically sealed pipes due to the very limited space. All selected processes were considered low-dust generating processes and performed as such in practice at the time of the study. Despite this, 20 of 33 stationary samples and 45 of 52 personal samples showed concentrations of asbestos fibers above the Danish occupational exposure limit value (OEL) of 0.003 f/cm3. Two personal samples, one measured during the removal of facade plates and one measured during the removal of pipes, had concentrations below the limit of detection.

Personal and stationary fiber concentrations in each of the work processes are shown in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Both personal exposure of workers performing the tasks, measured in close proximity to the source, and exposure of other employees in the vicinity but performing a different task farther from the source, as measured by stationary samples, are considerable.

Table 1.

Personal asbestos fiber concentrations in different work processes; analyzed with SEM; n > LOD-number of samples in which Chrysolite and Amphibole asbestos fibers were found above the limit of detection; %—percent content of, respectively, Chrysolite and Amphibole fibers in samples; N/A—not applicable.

Table 2.

Stationary asbestos fiber concentrations in different working processes; analyzed with PCM; N/A—not applicable.

3.1. Asbestos Cement Facade Plates

Measurements were conducted at one construction site over two days. Five of the six personal measurements were above the detection limit, with the measured concentration of asbestos fibers between 0.0011 f/cm3 and 0.0061 f/cm3. The first three personal samples were conducted with smaller pumps and a lower airflow of 2 L/min. Since those pumps had problems with pressure drop on the filter, the pumps were substituted with larger pumps that ran at twice the airflow.

Concentrations of asbestos fibers in these later samples were all above the detection limit, with a geometric mean (GM) equal to 0.0029 f/cm3. The later samples were conducted on the same workers performing the same tasks as in the first three measurements. The lower air flow in the first three measurements possibly resulted in an underestimation of asbestos concentrations compared to later measurements with doubled flow and probably also explains the one measurement below the LOD.

The first three measurements were conducted on a sunny day with temperatures between −1 and +8 °C, 57–98% relative humidity (RH), and wind speeds between 1.9 and 3.4 m/s, blowing from the north and northwest. The last three measurements were conducted two months later, on a sunny day with temperatures between 11 and 16 °C, 45–60% RH, and wind speeds between 5.9 and 7.1 m/s, blowing from the Southeast. These conditions may have impacted the results, as higher wind speeds may have contributed to a higher release ratio of asbestos fibers. This tendency was, however, not observed in stationary samples where lower values were measured during the second round of measurements. All stationary measurements were above the LOD, ranging from 0.0016 f/cm3 to 0.0041 f/cm3. Other than asbestos fibers, we measured high concentrations of mineral wool fibers coming from the removal of underlying insulation.

Two personal measurements were above the Danish OEL for an eight-hour work period. Both measurements were conducted in four hours of work time. Workers continued performing the same tasks for another two hours, where exposure is assumed to be at the same level. The measured values reflect, therefore, a six-hour average exposure in an eight-hour working day, where the last two hours constitute breaks and can be considered as near-zero exposure. If two hours of zero exposure is considered true, the eight-hour average for the highest measured value can be calculated to 0.0046 f/cm3. i.e., still above the Danish OEL.

The removal of the facade plates was not performed in an enclosed area. The concentrations, especially for the stationary samples, can; therefore, be underestimated as a result of wind exposure. Our results are considerably lower than the results of personal measurements conducted by Ervik et al., who reported SEM-analyzed asbestos concentrations in the range of 0.02 and 0.4 f/cm3 during the removal of wall shingles and 0.1 f/cm3 during the removal of felt and batten on exterior walls, both processes conducted inside plastic coverings [14]. A high concentration of fibers was also measured in Poland during the stripping of asbestos cement facade plates, with concentrations ranging from 0.03 to 0.9 f/cm3 for work conducted on a block of flats and 0.01–0.20 f/cm3 for work conducted on cooling towers (personal measurements, PCM analysis) [15].

3.2. Asbestos Cement Roofs

Five projects involving asbestos cement roofing were included in the study. In four of the five projects, closed areas were built with a full roof covering, negative pressure, and with access to the work area through three-chamber locks. In one project (project no. 4, Table 3), a roof covering was built as well, but the sides are not tightened properly, and windbreaks are cut in the cover, so there is a passage of wind through the area.

Table 3.

Results of personal air samples during the removal of corrugated roof sheets and the wrapping of roof sheets and insulation in five projects; analyzed with SEM.

As shown in Table 3, the results collected during the removal of roof sheets varied significantly between projects (p = 0.002). The number of workers performing tasks in the working area, the intensity and type of the work being performed, the wind, and varying construction site designs all contribute to this variation. In project no. 3, very little work was conducted by only two workers during measuring time, resulting in lower fiber concentrations compared to the other projects (p = 0.025), but still above the Danish OEL. Project no. 4, conducted under a loose cover on windy days, had lower measurements for stationary samples compared to other projects (p = 0.018). Project no. 5 was an exceptional case compared to the other four projects in that there was extensive planning work and a close dialog between the consultant and the Danish Labor Authority to ensure a low-dust-generating work process. Despite these efforts, project no. 5, such as the other four, showed the presence of asbestos fibers in the work environment. Despite the large spread, the measured concentrations of asbestos fibers in personal samples were high, with all but one above the Danish OEL. The concentration of asbestos fibers in 12 of 23 stationary samples was also above the Danish OEL (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of stationary air samples during the removal of corrugated roof sheets and the wrapping of roof sheets and insulation in five projects; analyzed with PCM.

In two projects (project no. 1 and 2, Table 3), measurements are performed during two processes, namely the removal of roof sheets and the wrapping of roof sheets and underlying insulation, revealing higher personal concentrations measured during the removal process (p < 0.001).

A sub-study was carried out on project no. 3. Three to four employees were asked to handle the roofing sheets as gently as possible by carefully lifting them up and carrying them down. Results of sampling carried out under these special conditions still showed high concentrations of asbestos fibers in the air, where all three personal measurements and both stationary measurements were above the Danish OEL (see Table 1 and Table 2). As shown in Figure 1c,d, the roofing sheets and underlying insulation were covered with large amounts of moss and asbestos-containing dust. Even gentle handling of the sheets did not prevent the spread of fibers into the environment.

The use of fiber binder on roofing sheets and insulation bats prior to removal had no measurable impact on personal or stationary asbestos concentrations. The number of measurements was, however, limited.

In addition to a high concentration of asbestos fibers measured during the investigated processes, a high development of dust was observed by visual inspections. Furthermore, high concentrations of mineral wool fibers were measured in the personal samples (Table 1).

Our results are moderate compared to prior studies. In 1987, Brown [5] reported high asbestos fiber concentrations during the renovation and demolition of asbestos cement-clad buildings. Personal measurements of workers replacing weathered asbestos cement roofing showed concentrations between 0.03 f/cm3 and 0.32 f/cm3. Similar concentrations were also found in newer studies. A Norwegian study [14] reported concentrations between 0.1 and 0.4 f/cm3 in personal samples and 0.02–0.08 f/cm3 in stationary samples during the dismantling of corrugated roof sheets and slate shingles, measured with the SEM method. As in our study, the work was conducted within a plastic roof covering. Measurements without the plastic cover during the dismantling of corrugated roof sheets ranged from <0.004 f/cm3 to 0.01 f/cm3, similar to the findings of this study. Measurements during the demolition of residential dwellings in Turkey also showed concentrations between 0.0066 f/cm3 and 0.0242 f/cm3 [16]. These concentrations are comparable to our results, though the work environment and sampling methods differ. To our knowledge, there are no other studies where the work environment and process type are comparable to our study. Several other studies suggest; however, elevated exposure to asbestos fibers in the construction sector [7,17,18].

3.3. Pipe Insulation

Six measurements were carried out over three days at a single construction site, where vertical pipes with asbestos-containing insulation were first sealed and then cut off. Only personal measurements were taken as the workspace was too small to accommodate the stationery set up.

Five of the six personal measurements were above the detection limit with a measured concentration of asbestos fibers between 0.0012 f/cm3 and 0.0102 f/cm3. Four measurements were above the Danish OEL. This process was assumed not to release asbestos fibers since the cutting points were located on asbestos-free parts of the pipe, and the asbestos-containing insulation material was wrapped in the plastic foil and sealed with tape on both ends prior to cutting. A possible accumulation of asbestos fibers in the dust in pipe penetrations between floors and their release in the removal process could explain the high asbestos fiber counts.

The measurements were carried out over 49–104 min, after which no more pipes were cut in the remainder of the workday. However, employees performed other tasks in the area, where zero asbestos exposure in the remaining six hours cannot be assumed.

We found only one study where measurements under similar processes were conducted. Ervik et al. [14] reported a personal measurement concentration of 0.02 f/cm3, which is equivalent to the highest value measured in this study.

3.4. Limitations

The project was met with resistance from contractors, who, for several reasons, did not want to participate in the study. Thus, fewer measurements were carried out than planned, and, in the case of façade removal and pipe removal, only on one construction site. Although results were fairly consistent for these various processes, there may be differences in design and execution practices on other construction sites that are not apparent from the results of this study.

Foreign craftsmen worked on most of the construction sites, and many of them could only communicate in their own language. The language barrier hindered the collection of information on the tasks and the conditions in which they were carried out. This did not likely affect the measurements, but some important observations and information about the work performed may have been lost, e.g., the number of plates destroyed, varying workloads, and possible changes in procedure. The language barrier also resulted in a few instances in the pumps being switched off, dropped, or disconnected by workers due to misunderstandings. Such errors reduced the number of valid observations.

Most processes turned out to be quite dusty. Shortening sampling time was, therefore, necessary to prevent the overloading of filters. This resulted in a relatively high LOD for the personal samples. The recommended detection limit is typically 10% of the established occupational exposure limit, which is why current measurements would not be accurate enough to conclude exposure below the Danish OEL. As the opposite was found, we believe that high concentrations measured in the study are not affected by the LOD. Despite shortening the sampling time to two hours for most processes, some filters still became overloaded. Overloaded filters may have hidden smaller fibers from being detected, introducing possible underestimation of fiber counts. This possible underestimation only strengthens the study’s main finding, namely that the investigated processes were not low dust-generating, and the exposure to asbestos fibers of workers is most likely to be greater than the Danish OEL.

Two analysis methods were used in this study. Personal samples were collected on gold-coated filters and analyzed by SEM, while stationary samples were taken on cellulose filters and analyzed by PCM. Theoretically, if only asbestos fibers were present, PCM and SEM should have a 1:1 correspondence [14]. Results from these two methods are, however, not directly comparable, due to the presence of other fibers and asbestos fibers thinner than 0.2 µm [9,14]. Therefore, the direct comparison of the exposure of workers performing asbestos removal tasks with the exposure of workers in the vicinity is not possible. The results from SEM analysis showed that mostly asbestos and mineral wool fibers were present, and suggest that the combination of the two fiber types was detected by PCM analysis. No parallel sampling using both methods of fiber detection was carried out in this study, and this is a limitation. Ervik et al. [14] reported a slope of 0.72 for the relationship between SEM results for WHO fibers and PCM results during exterior wall and roof removal. This suggests an overestimation of the PCM results due to the presence of other fibers.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the exposure of workers to asbestos fibers performing low-dust-generating demolition processes, as defined by the Danish law and considered in practice. This study included processes involving the removal of roofing sheets, the removal of facade panels, and the removal of pipes covered with intact asbestos insulation.

Despite the large spread of results between processes and between workers and construction sites within each process, none of the investigated processes were confirmed to be low-dust generating. Concentrations of asbestos fibers considerably above the Danish OEL were measured in all investigated processes, in both personal and stationary samples. Attempts to reduce the generation of dust and asbestos fibers with the use of fiber binder and gentle handling of roofing plates have not been sufficiently effective.

This study underlines the need for protective measures while working with asbestos—containing materials in order to protect workers in direct contact with such materials and workers performing other non-asbestos containing tasks in the vicinity.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was mostly performed by B.D.K. All laboratory analyses were performed by S.C.R. The first draft of the manuscript was written by B.D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work has been supported by a grant from the Danish Working Environment.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present work does not report research involving human or animal subjects, their data, and/or biological materials. Therefore, the ethical declaration is unnecessary.

Informed Consent Statement

The present work did not involve data collection from human subjects. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on special request. Raw data have been published in the form of a project report available in Danish at https://at.dk/media/e5qbjehn/dma-projekt-om-luftmaalinger-af-asbeststoev.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the companies that participated in this project and generously contributed their time. A special appreciation goes to the dedicated workers who took part in the measurements—their cooperation and commitment were instrumental to the success of this study. We also extend our heartfelt gratitude to Mille Bolander for her invaluable assistance in data collection and Victoria De Knegt for extensive language corrections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors B.D.K., S.C.R., M.N.O., and K.K. are employed by the company Danish Environmental Analysis Inc. (Dansk Miljoanalyse Aps). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OEL | occupational exposure limit value |

| PCM | Phase Contrast Microscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

References

- WHO. Elimination of Asbestos-Related Diseases. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-PHE-EPE-14.01 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- WHO. Determination of Airborne Fibre Number Concentrations. 1997. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241544961 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Fonseca, A.S.; Jørgensen, A.K.; Larsen, B.X.; Moser-Johansen, M.; Flachs, E.M.; Ebbehøj, N.E.; Bønløkke, J.H.; Østergaard, T.O.; Bælum, J.; Sherson, D.L.; et al. Historical Asbestos Measurements in Denmark—A National Database. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BEK nr 291. Bekendtgørelse om Grænseværdier for Stoffer og Materialer (Kemiske Agenser) i Arbejdsmiljøet; Beskæftigelsesministeriet, Arbejdstilsynets: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024.

- Brown, S. Asbestos exposure during renovation and demolition of asbestos-cement clad buildings. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 1987, 48, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakol, G.; Muszynska-Graca, M. Removeal of asbestos-cement sheets and occupationel and enviromental exposure to asbestos (article in Polish). Medycna Srodowiskowa-Environ. Med. 2017, 20, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kakooei, H.; Normohammadi, M. Asbestos exposure among construction workers during demolition of old houses in Tehran, Iran. Ind. Health 2014, 52, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obminski, A.; Janeczek, J. The effektivness of asbestos stabilizers during abrasion of asbestos-cement sheets. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervik, T.; Hammer, S.E.; Graff, P. Mobilization of asbestos fibres by weathering of a corrugated asbestes cement roof. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2021, 18, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEK nr 744. Bekendtgørelse om Asbest i Arbejdsmiljøet; Arbejdstilsynets Beskæftigelsesministeriet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024.

- Kolarik, B.; Nerum Olsen, M.; Kampmann, K.; Vaagelund Eriksen, J.; Rørbye, S.C. Måleprojekt—Asbestniveauer Ved Arbejde der Udføres Som Arbejde Med Lavt Støvniveau; Dansk MiljøAnalyse: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- DS 2169:1981; Luftundersøgelse. Arbejdspladsluft. Tællekriterier for Asbestfibre. Dansk Standard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1981.

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. ASBESTOS and OTHER FIBERS by PCM. 1994. Report No.: NIOSH 7400. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2003-154/pdfs/7400.pdf (accessed on 15 August 1994).

- Ervik, T.K.; Hammer, S.E.; Skaugset, N.P.; Graff, P. Measuremens of airborne asbesos fibres during refurbishing. Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2023, 67, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakol, G.; Muszynska-Graca, M. Air pollution during asbestos removal. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 28, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetik, Y.O.; Bayram-Zumrut, I.; Camurcu, A.G.; Kale, O.A.; Baradan, S. Measurement and removal of asbesos in residential dwellings to be demolished—Urban transformation experience in Izmir-Turkey. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 9857–9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarselli, A.; Marinaccio, A.; Di Marzio, D.; Iavicoli, S. Occupational asbestos exposure after the ban: A job exposure matrix developed in Italy. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, J.H.; Lange, P.R.; Reinhard, T.K.; Thomulka, K.W. A study of Personal and area airborne asbestos concentrations during asbestos abatement: A statistical evaluation of fibre concentration data. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 1996, 40, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).