Abstract

Therapy resistance remains a major cause of relapse and poor outcomes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Recent multi-omics studies in ALL have revealed that resistance arises from a combination of leukemia-specific genetic lesions, treatment-driven clonal evolution, and adaptive non-genetic programs. Genomic analyses have identified recurrent alterations associated with resistance to chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and immunotherapies, while single-cell profiling has uncovered heterogeneous cell states that persist during treatment and contribute to minimal residual disease. Emerging epigenetic, proteomic, and metabolic data further indicate that reversible regulatory and signaling changes play a central role in leukemic persistence. Integrative analyses are beginning to define convergent resistance pathways and clinically relevant biomarkers, although longitudinal sampling and clinical translation remain limited. This review summarizes the current multi-omics landscape of therapy resistance in ALL and discusses opportunities to improve risk stratification and therapeutic strategies.

1. Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is an aggressive hematologic malignancy characterized by the clonal proliferation of immature lymphoid cells in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, and other organs [1]. It represents the most common cancer in children and also occurs in adults, where outcomes are generally less favorable [2]. Over the past several decades, the introduction of intensive multi-agent chemotherapy, targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for BCR::ABL1-positive disease [3], and novel immunotherapies including blinatumomab [4] and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy [5] has markedly improved survival rates, particularly in pediatric populations. However, therapy resistance remains a major obstacle, leading to relapse in a significant subset of patients and contributing to poor long-term outcomes, especially in adults and high-risk subgroups [6].

Therapy resistance in ALL is a multifactorial process influenced by both genetic and non-genetic mechanisms. Genomic alterations such as mutations in NT5C2 [7], CREBBP [8], TP53 [8], and IKZF1 [9] can confer intrinsic or acquired drug resistance. Transcriptional reprogramming, epigenetic plasticity, proteomic changes, and metabolic adaptations further enable leukemic cells to survive under therapeutic pressure [10]. The tumor microenvironment, including bone marrow stromal support and immune evasion mechanisms, also plays a critical role. Given this complexity, single-layer molecular analyses often provide an incomplete picture, limiting the ability to predict resistance or develop effective counterstrategies.

Multi-omics approaches—integrating genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—offer a comprehensive framework to unravel the molecular underpinnings of therapy resistance in ALL [10,11]. Advances in high-throughput sequencing, mass spectrometry, and computational biology now allow the systematic profiling of genetic mutations, gene expression programs, chromatin accessibility, protein signaling networks, and metabolic states. Importantly, single-cell multi-omics technologies add spatial and temporal resolution, enabling the dissection of heterogeneous subpopulations and the identification of rare but clinically relevant resistant clones [12]. By integrating data across multiple molecular layers, researchers can uncover convergent pathways and master regulators that might be overlooked by single-modality studies.

In recent years, multi-omics studies have revealed several key insights into ALL therapy resistance. For instance, genomic analyses have traced the clonal evolution from diagnosis to relapse, pinpointing mutations that arise under treatment pressure [13]. Transcriptomic profiling has identified cell states associated with quiescence, stemness, and altered drug metabolism [14], while epigenomic studies have highlighted reversible chromatin modifications that permit adaptive transcriptional responses [15]. Proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses have mapped rewired signaling cascades, revealing novel kinase dependencies, and metabolomics has shed light on altered energy utilization and redox balance in resistant cells [16]. When integrated, these datasets can identify vulnerabilities that may be exploited therapeutically, such as metabolic bottlenecks or synthetic lethal interactions.

The clinical implications of such integrative multi-omics analyses are substantial. They can enable precise patient stratification, guiding the selection of optimal treatment regimens and informing the use of targeted agents or combination therapies to preempt or overcome resistance [17]. They also facilitate the discovery of predictive biomarkers for minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring and early detection of resistance emergence, which is critical for timely therapeutic intervention [18]. Furthermore, multi-omics-driven drug discovery can accelerate the identification of novel targets and pathways amenable to pharmacologic modulation.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain in translating multi-omics findings into routine clinical practice. Technical and analytical issues, such as data integration, standardization, and interpretation, must be addressed [19]. Biological heterogeneity within and between patients necessitates large, longitudinal cohorts to capture the full spectrum of resistance mechanisms. Moreover, ethical and logistical considerations, including data sharing, cost, and accessibility of multi-omics technologies, will need to be navigated to ensure equitable implementation [20].

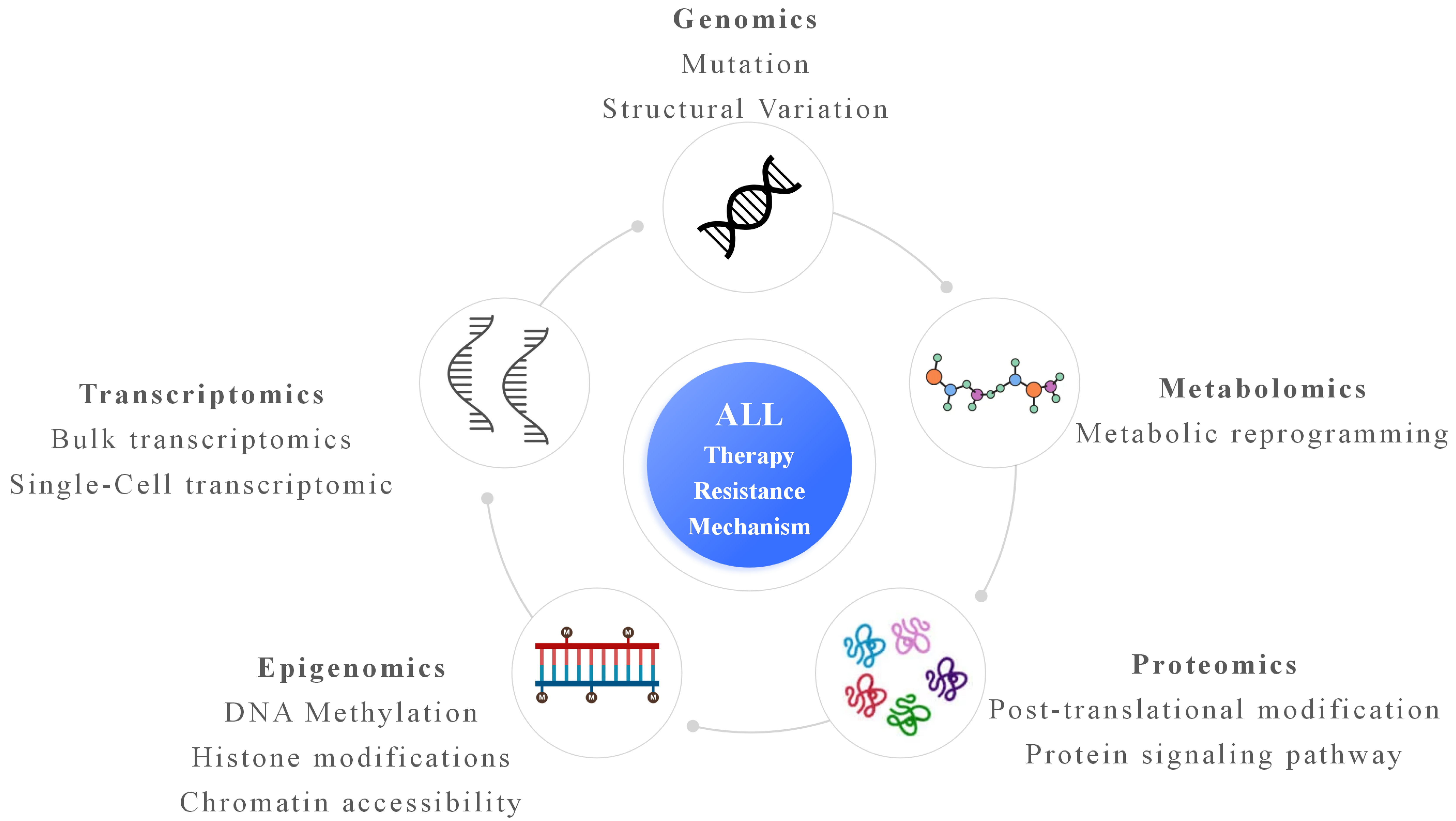

This review aims to synthesize current knowledge on therapy resistance in ALL through the lens of multi-omics research. We first outline the major therapeutic modalities used in ALL and summarize known resistance mechanisms. We then explore how each omics layer—genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—has contributed to understanding resistance biology (Figure 1), with particular attention to single-cell and integrative multi-omics approaches. Finally, we discuss the translational potential of multi-omics in guiding personalized therapy, the current challenges hindering clinical adoption, and future directions for leveraging these technologies to improve patient outcomes. By bridging basic and translational research, multi-omics approaches hold promise for overcoming therapy resistance and achieving durable remissions in ALL.

Figure 1.

Multi-omics underlying therapy resistance in ALL. Genomic alterations, including gene mutations and structural variations, provide the genetic basis for resistance. Transcriptomic analyses, at both bulk and single-cell resolution, reveal heterogeneous gene expression programs and rare drug-tolerant cell states. Epigenomic changes, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and altered chromatin accessibility, enable transcriptional plasticity and adaptive responses to therapeutic pressure. Proteomic profiling captures post-translational modifications and rewired signaling pathways that directly mediate survival and drug insensitivity. Metabolomic reprogramming reflects adaptive changes in cellular metabolism that support energy homeostasis and stress tolerance during treatment. Integration of these multi-omics layers converges on a comprehensive understanding of ALL therapy resistance, highlighting interconnected molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities.

2. Genomic Findings Related to Therapy Resistance in ALL

Genomic alterations are a major driver of both intrinsic and acquired therapy resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [21]. Advances in high-throughput sequencing have enabled comprehensive characterization of the mutational landscape, revealing recurrent lesions that promote drug insensitivity, facilitate clonal evolution, and ultimately contribute to relapse [22].

One of the most frequently implicated genomic events in relapsed ALL is mutation of NT5C2 [7], a cytosolic 5′-nucleotidase involved in purine metabolism. Activating NT5C2 mutations enhance the breakdown of nucleoside analogs such as 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) [23] and thioguanine [24], diminishing their cytotoxicity. These alterations are often absent at diagnosis but emerge under selective pressure from maintenance therapy, highlighting their role in acquired resistance.

Mutations in CREBBP, encoding a histone acetyltransferase, are enriched in relapsed B-ALL and can impair glucocorticoid receptor-mediated transcription, leading to steroid resistance [25]. Similarly, alterations in TP53 disrupt cell cycle checkpoints and DNA damage responses, conferring broad resistance to chemotherapeutics [26]. IKZF1 deletions or mutations, common in high-risk BCR::ABL1-positive and BCR::ABL1-like ALL, are associated with poor treatment response and increased relapse risk [27].

In T-cell ALL (T-ALL), activating mutations in NOTCH1 [28] and loss-of-function lesions in FBXW7 are frequent, and these alterations drive leukemogenesis [29], their contribution to therapy resistance is context-dependent. Relapsed T-ALL often harbors additional lesions affecting cell cycle regulation (CDKN2A/B deletions) and kinase signaling pathways, suggesting stepwise genomic evolution during treatment [30].

Clonal evolution is a hallmark of therapy-resistant ALL. Longitudinal sequencing has shown that resistant subclones may pre-exist at low frequencies before treatment, expanding under therapeutic pressure [31]. In some cases, relapse is driven by a genetically distinct lineage derived from an ancestral pre-leukemic clone, indicating that eradication of dominant diagnostic clones may not prevent disease recurrence [32]. This dynamic evolution underscores the importance of serial genomic monitoring for early detection of resistant clones. Notably, however, several studies [33,34] have demonstrated that the presence of relapse-associated mutations in minor diagnostic subclones does not consistently predict relapse, suggesting that genetic alterations alone are insufficient to determine clonal fitness. Instead, additional factors such as therapy-induced selective pressure, non-genetic adaptive states, and microenvironmental influences play critical roles in enabling subclone persistence and expansion at relapse.

Structural variations also play a role in resistance [35]. For example, CRLF2 rearrangements [36] and JAK-STAT pathway mutations in Ph-like ALL can confer resistance to standard regimens but may create vulnerabilities to JAK inhibitors [37]. Likewise, gene fusions such as ETV6::RUNX1 and KMT2A rearrangements influence treatment response and may shape relapse biology through secondary genomic hits [38].

Recent mutational signature analyses have provided important insights into the evolution of relapsed ALL and the contribution of therapy-induced mutagenesis to resistance. Compared with diagnostic samples, relapsed ALL frequently shows increased treatment-associated mutational signatures, reflecting DNA damage caused by cytotoxic chemotherapy and indicating that therapy itself actively shapes the leukemic genome [39]. Notably, RAS pathway mutations are often enriched at relapse and have been linked to treatment adaptation in pediatric B-cell precursor ALL, supporting their potential role as predictive biomarkers [40].

Of note, the composition of upfront therapy at diagnosis plays a crucial role in shaping the landscape of relapse in ALL. Recent studies have shown that different therapeutic regimens exert distinct selective pressures on leukemic clones, influencing both their survival and clonal evolution. For example, certain therapies may drive the expansion of subclones with specific mutations, while others may induce mutagenic processes that generate novel relapse-associated mutations [40,41]. This highlights the need to consider the therapeutic context when studying relapse, as the initial treatment regimen may significantly impact the genetic and clonal features of subsequent relapses.

Collectively, genomic studies have illuminated diverse mechanisms by which ALL cells evade therapy. While individual lesions can guide targeted interventions, integrative genomic profiling—particularly in serial samples—remains essential for capturing the full spectrum of resistance pathways and informing adaptive treatment strategies.

3. Transcriptomic and Single-Cell Transcriptomic Characterization in ALL

Transcriptomic profiling has provided crucial insights into the molecular programs that underlie therapy resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [42]. Bulk RNA sequencing has enabled the identification of gene expression signatures associated with poor prognosis, drug insensitivity, and relapse [43], while single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has further resolved the cellular heterogeneity that often underlies treatment failure [44].

Bulk transcriptomic studies have revealed distinct expression patterns in resistant ALL compared with treatment-sensitive disease. For example, glucocorticoid resistance—one of the most common forms of drug insensitivity in ALL—has been linked to downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor target genes and activation of pro-survival pathways such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling [45]. In relapsed B-ALL, upregulation of genes involved in cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and drug efflux (e.g., ABC transporters) has been frequently observed [46]. In T-ALL, transcriptional reprogramming toward a stem-like phenotype, with increased expression of genes regulating quiescence and self-renewal, has been implicated in resistance to chemotherapy and targeted agents [47].

Single-cell RNA-seq has transformed the understanding of therapy resistance by enabling the dissection of heterogeneous leukemic cell populations within individual patients [48]. Resistant subpopulations often pre-exist at diagnosis, characterized by distinct transcriptional states that confer survival advantages under treatment pressure [49]. For instance, rare quiescent or dormant subclones can evade cytotoxic agents targeting rapidly dividing cells, only to expand during remission and cause relapse [50]. In addition, scRNA-seq has revealed transcriptional plasticity, where leukemic cells dynamically shift between cell states in response to therapy, adopting phenotypes that favor persistence and immune evasion [51].

Another critical contribution of single-cell transcriptomics is the ability to map the interplay between leukemic cells and the bone marrow microenvironment [52]. Studies have identified resistance-associated programs driven by stromal interactions, cytokine signaling, and hypoxic niches, highlighting the role of extrinsic factors in sustaining drug-tolerant states.

Integration of transcriptomic data with other omics layers has further clarified the functional impact of genetic and epigenetic alterations on gene expression programs. For example, CREBBP mutations correlate with altered expression of glucocorticoid-responsive genes [53], while IKZF1 deletions disrupt transcriptional networks critical for B-cell differentiation.

Overall, transcriptomic and single-cell transcriptomic analyses provide a high-resolution view of the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of therapy resistance in ALL. These approaches not only illuminate the cellular states and pathways driving relapse but also offer a foundation for identifying biomarkers and therapeutic targets aimed at eradicating resistant subpopulations.

4. Epigenomic Mechanisms Underlying Resistance in ALL

Epigenetic regulation plays a pivotal role in shaping gene expression programs without altering the underlying DNA sequence, and accumulating evidence indicates that epigenomic dysregulation contributes significantly to therapy resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [54]. Alterations in DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin accessibility can enable leukemic cells to adapt transcriptionally to therapeutic stress, thereby sustaining survival and promoting relapse.

Aberrant DNA methylation patterns are frequently observed in ALL and can modulate the expression of genes involved in drug metabolism, apoptosis, and cell cycle control [55]. Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters, such as CDKN2A/B, silences their expression and contributes to unchecked proliferation [56]. Conversely, hypomethylation at oncogenic loci can sustain the activation of pro-survival pathways. Relapse-specific methylation changes often emerge under treatment pressure, indicating that the epigenome is dynamically remodeled during disease progression.

Histone modifications also play a critical role in resistance. Loss-of-function mutations in the histone acetyltransferase CREBBP, enriched in relapsed B-ALL, reduce histone acetylation at glucocorticoid-responsive promoters, impairing transcriptional activation by the glucocorticoid receptor and conferring steroid resistance [57]. Similarly, mutations in histone methyltransferases such as SETD2 alter chromatin structure and influence DNA repair capacity, enhancing tolerance to chemotherapy-induced genotoxic stress [58].

Chromatin accessibility profiling using ATAC-seq has revealed that resistant leukemic cells frequently maintain open chromatin at enhancers and promoters of survival genes, even under drug treatment [59]. This epigenetic plasticity enables rapid transcriptional reprogramming in response to therapy, allowing cells to adopt drug-tolerant states. Single-cell ATAC-seq studies have further shown that subpopulations with distinct chromatin landscapes pre-exist at diagnosis, potentially serving as reservoirs for relapse [60].

Importantly, epigenomic alterations often act in concert with genetic lesions. For example, IKZF1 deletions disrupt chromatin organization at B-cell regulatory elements, reprogramming transcriptional networks toward a less differentiated and more therapy-resistant state [61]. This interplay underscores the need for integrated genomic and epigenomic analyses to fully elucidate resistance mechanisms.

From a therapeutic standpoint, the reversibility of epigenetic modifications offers a promising avenue for intervention. Agents targeting DNA methyltransferases (e.g., azacitidine) or histone deacetylases have shown potential in re-sensitizing resistant ALL cells to conventional therapies [62]. Future strategies may involve rational combinations of epigenetic modulators with targeted agents or immunotherapies to prevent or overcome resistance.

In summary, epigenomic dysregulation in ALL fosters transcriptional adaptability, enabling leukemic cells to survive therapeutic pressure. Comprehensive mapping of these alterations will be essential for developing strategies to eradicate drug-tolerant populations and improve long-term outcomes.

5. Proteomic and Metabolomic Contributions in ALL

While genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic profiling reveal upstream regulatory mechanisms of therapy resistance, proteomic [63] and metabolomic [64] analyses provide direct insight into the functional consequences of these alterations. Proteins and metabolites represent the active effectors of cellular phenotypes, and their abundance, modifications, and interactions often more closely reflect the drug-resistant state than gene-level data alone.

Proteomic profiling, particularly using quantitative mass spectrometry and phosphoproteomics, has uncovered aberrant activation of signaling pathways that promote survival under therapeutic stress [65]. In B-ALL, resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has been associated with upregulation of alternative kinase signaling, such as SRC family kinases [66] or PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways [67], which bypass BCR-ABL1 inhibition. In T-ALL, proteomic studies have revealed persistent NOTCH1 signaling and elevated phosphorylation of downstream effectors that maintain proliferation despite chemotherapy [68]. Moreover, post-translational modifications (PTMs)—including phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination—can dynamically alter protein stability, localization, and activity, thereby modulating drug sensitivity [69]. For example, altered phosphorylation states of apoptosis regulators such as BCL2 family proteins can tilt the balance toward cell survival [70].

Metabolomic analyses have highlighted the role of metabolic reprogramming in ALL resistance [71]. Drug-tolerant leukemic cells frequently shift toward oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to meet energy demands and maintain redox homeostasis. Enhanced mitochondrial metabolism not only supports survival under nutrient or drug stress but also reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, thereby mitigating chemotherapy-induced oxidative damage [72]. Some resistant phenotypes display increased glycolytic flux and glutamine dependence, providing metabolic flexibility that enables adaptation to different microenvironmental conditions. Additionally, alterations in nucleotide biosynthesis pathways can affect the efficacy of antimetabolite drugs, as observed in thiopurine-resistant ALL with increased purine salvage pathway activity.

Integration of proteomic and metabolomic data has revealed coordinated adaptations between signaling and metabolic networks. For instance, activation of PI3K/AKT signaling can drive glycolytic reprogramming [73], while alterations in AMPK and mTOR signaling influence lipid and amino acid metabolism [74]. These interconnected changes create a metabolic landscape optimized for resistance, often at the expense of proliferative speed but with enhanced persistence.

From a translational perspective, proteomic and metabolomic profiling can identify actionable vulnerabilities. Targeting metabolic dependencies with OXPHOS inhibitors or disrupting compensatory kinase signaling pathways has shown promise in preclinical models. Furthermore, proteomic biomarkers, such as phosphorylation patterns or metabolite ratios, may serve as early indicators of resistance emergence, guiding adaptive therapy strategies.

Overall, proteomic and metabolomic approaches complement other omics layers by capturing the functional outputs of resistance mechanisms, offering critical opportunities for biomarker discovery and therapeutic intervention in ALL.

6. Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis and Systems Biology Approaches in ALL

While individual omics platforms provide valuable insights into therapy resistance, no single layer can capture the full complexity of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) biology. Integrative multi-omics approaches combine data from genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to construct a holistic view of resistance mechanisms [75]. This comprehensive perspective is particularly valuable in ALL, where resistance often arises from interconnected genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic adaptations.

Data integration can be achieved through sequential or simultaneous profiling of matched patient samples, enabling direct correlation between molecular alterations at different regulatory levels. For example, combining genomic and transcriptomic analyses can link specific mutations (e.g., CREBBP, NT5C2) to downstream transcriptional reprogramming and pathway activation. Similarly, integration of epigenomic and transcriptomic data has revealed how chromatin remodeling reshapes gene expression in resistant leukemic subclones, while proteogenomic approaches bridge the gap between mutational landscapes and functional protein signaling changes.

Systems biology frameworks further enhance these integrative analyses by modeling molecular interactions within complex networks [76]. Network-based approaches can identify “hub” genes or proteins—master regulators whose perturbation may reverse resistance phenotypes [77]. For instance, multi-omics integration has pinpointed convergent activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in resistant ALL, regardless of upstream mutational drivers, suggesting a central vulnerability amenable to targeted inhibition.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) are increasingly employed to handle the high dimensionality of multi-omics datasets [78]. Predictive models trained on integrated omics features can stratify patients according to relapse risk, forecast treatment responses, identify candidate biomarkers for minimal residual disease (MRD) detection, and facilitate diagnostics and translational discovery [79]. In preclinical studies, AI-driven integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic data has revealed metabolic signatures predictive of glucocorticoid resistance, opening avenues for tailored metabolic interventions [80].

Longitudinal integrative analyses, involving multi-omics profiling at diagnosis, during therapy, and at relapse, provide unique insights into clonal evolution and the temporal dynamics of resistance [81]. Such studies can distinguish early adaptive responses from late, genetically fixed resistance mechanisms, guiding the timing and selection of therapeutic interventions.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in standardizing data processing, harmonizing results across platforms, and validating findings in large, diverse patient cohorts. Nonetheless, integrative multi-omics coupled with systems biology represents a powerful paradigm for unraveling the complexity of ALL resistance. By revealing cross-cutting vulnerabilities and enabling predictive modeling, these approaches hold promise for informing adaptive, personalized therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing or overcoming relapse.

7. Clinical Implications and Translational Applications in ALL

The integration of multi-omics research into the clinical landscape of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) offers unprecedented opportunities to refine diagnosis, predict therapy response, and personalize treatment strategies [82]. Genomic profiling has already become a cornerstone in risk stratification, enabling the identification of actionable mutations such as BCR-ABL1, JAK-STAT pathway alterations, and IKZF1 deletions that influence therapeutic decisions. Extending beyond genomics, transcriptomic and epigenomic data provide additional layers of patient-specific molecular information, helping to distinguish between primary and acquired resistance mechanisms and to identify minimal residual disease (MRD) signatures with higher sensitivity [83].

Multi-omics insights are driving the development of novel targeted therapies in ALL. For example, the identification of metabolic reprogramming patterns and altered protein interaction networks in resistant clones has informed the design of combination therapies that concurrently target oncogenic signaling, metabolic dependencies, and epigenetic regulators [84]. Such approaches aim to prevent the emergence of drug-tolerant persister cells, a major clinical obstacle. Moreover, multi-omics-derived biomarkers can inform adaptive treatment regimens, allowing early intervention upon detection of resistance signatures through non-invasive liquid biopsies.

The clinical translation of multi-omics research also extends to immunotherapy optimization. Profiling tumor and immune microenvironment interactions at the single-cell level has revealed markers of CAR-T cell exhaustion, immune evasion pathways, and cytokine signaling imbalances, providing a basis for engineering next-generation cellular therapies with improved persistence and efficacy [85]. Epigenomic reprogramming strategies, such as targeting histone modifiers or DNA methyltransferases, are being explored to enhance immune recognition and response durability.

Importantly, the implementation of multi-omics in clinical practice requires robust bioinformatics pipelines and standardized data integration frameworks to ensure reproducibility, scalability, and regulatory compliance [86]. The increasing availability of multi-omics datasets facilitates the development of predictive algorithms and machine learning models capable of delivering real-time, patient-tailored treatment recommendations. However, translation to routine care is challenged by issues of cost, data interpretation complexity, and the need for multidisciplinary expertise.

In summary, multi-omics approaches hold transformative potential for overcoming therapy resistance in ALL by enabling precision oncology strategies that integrate molecular, cellular, and systemic insights. As technological advances reduce barriers to implementation, the future of ALL management will increasingly rely on multi-layered biomarker-guided interventions, bridging the gap between bench discoveries and bedside applications.

8. Future Directions and Challenges in ALL

The application of multi-omics technologies to elucidate therapy resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has yielded critical insights, yet several challenges must be addressed to fully translate these findings into clinical benefit (Table 1). Future research directions should focus on enhancing data resolution, expanding cohort diversity, and integrating multi-dimensional datasets into actionable therapeutic strategies.

Table 1.

Major multi-omics findings and limitations in therapy resistance of ALL.

First, while current studies have identified numerous genetic, transcriptomic, epigenetic, proteomic, and metabolic alterations associated with resistance, the causal relationships among these layers remain incompletely defined. Longitudinal sampling before, during, and after treatment—coupled with single-cell multi-omics—could reveal the temporal evolution of resistant clones and the interplay between intrinsic tumor features and extrinsic microenvironmental cues. Furthermore, integrating spatial transcriptomics and spatial proteomics may uncover niche-specific resistance mechanisms that bulk profiling fails to detect.

Second, large-scale, harmonized datasets across diverse patient populations are needed to overcome the limitations of small, heterogeneous cohorts. Pediatric and adult ALL differ markedly in molecular landscape and treatment outcomes [49]; therefore, future research must ensure representation across age groups, ethnic backgrounds, and treatment regimens to identify both shared and subgroup-specific resistance mechanisms [87].

Third, the integration of multi-omics data into predictive models remains computationally challenging. Systems biology approaches, incorporating machine learning and network-based modeling, can aid in prioritizing resistance drivers and forecasting therapeutic vulnerabilities. However, these models require rigorous validation in preclinical models and prospective clinical studies to ensure reproducibility and clinical applicability.

Fourth, translating omics findings into therapeutic strategies demands robust functional validation. Genome editing, CRISPR screens, and organoid or patient-derived xenograft models will be essential to confirm the role of candidate targets and assess druggability. Combination therapies designed to simultaneously disrupt multiple resistance pathways hold promise, but optimal regimens must be guided by mechanistic evidence.

Finally, logistical and ethical considerations—including data privacy, cost, and equitable access to omics-guided therapies—must be addressed to ensure that advances benefit all patients. Collaborative consortia, standardized analytical pipelines, and open-access data repositories will be crucial to accelerating discovery and translation.

By addressing these challenges through technological innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and clinically anchored research, the next decade holds promise for leveraging multi-omics to overcome therapy resistance and improve outcomes in ALL.

9. Conclusions

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) remains a major therapeutic challenge despite remarkable advances in risk-adapted chemotherapy, targeted agents, and immunotherapies. While cure rates for pediatric patients have reached encouraging levels, outcomes for high-risk subsets, relapsed disease, and adults remain suboptimal. Over the past decade, multi-omics technologies—including genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—have transformed our understanding of the disease’s molecular underpinnings, revealing the intricate interplay of genetic lesions, dysregulated transcriptional programs, aberrant epigenetic landscapes, altered protein networks, and metabolic reprogramming.

Genomic studies have identified recurrent mutations and structural alterations that not only define biologically distinct subtypes but also illuminate mechanisms of therapy resistance. Transcriptomic and single-cell profiling have uncovered intratumoral heterogeneity and rare subpopulations with stem-like properties that can survive therapy and drive relapse [88]. Epigenomic mapping has revealed reversible regulatory changes that contribute to drug tolerance, offering new avenues for targeted reprogramming. Proteomic and metabolomic approaches have provided functional insights beyond static genetic information, capturing the dynamic states of leukemic cells in response to treatment.

Integrative multi-omics frameworks and systems biology approaches are now enabling the construction of comprehensive disease models that connect alterations across molecular layers, allowing for the identification of convergent vulnerabilities and biomarker signatures with potential clinical utility. These integrated insights are beginning to inform precision medicine strategies, from early risk stratification to the rational design of combination therapies aimed at preventing or overcoming resistance.

Despite these advances, translating multi-omics discoveries into routine clinical practice faces substantial challenges, including the need for standardized methodologies, robust bioinformatic pipelines, and cost-effective assays deployable in diverse healthcare settings [89]. Furthermore, longitudinal sampling and analysis are essential to capture the evolutionary trajectories of ALL under therapeutic pressure, but remain logistically and ethically complex.

In summary, multi-omics research has profoundly reshaped the landscape of ALL biology and therapy, providing an increasingly detailed and actionable blueprint of disease mechanisms. Continued integration of these technologies into translational research, coupled with collaborative efforts across disciplines, holds promise for achieving more durable remissions and, ultimately, cures. The future of ALL management will likely hinge on our ability to leverage these molecular insights to guide individualized treatment, monitor disease in real time, and anticipate resistance before it emerges.

Author Contributions

X.W. and J.Z. wrote and reivewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81900112).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adomako, J.; Jiménez-Camacho, K.E.; Correa-Lara, M.V.M.; Núñez-Enriquez, J.C.; Schnoor, M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapse: Biomarkers, hopes, and challenges. Trends Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 1032–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azza, E.; Ben Othmen, A.; Bahri, M.; Hsasna, R.; Ben Lakhel, R.; Ben Abdennebi, Y.; Aissaoui, L. T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Therapeutic outcomes in adolescents and young adults. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 4637–4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braish, J.; Kantarjian, H.; Short, N.J.; Tang, G.; Daver, N.; Kadia, T.; Senapati, J.; Jen, W.Y.; Takahashi, K.; Garris, R.; et al. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors During Frontline Therapy in Adults With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia With ABL-class Rearrangements. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025, 26, e110–e113.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.L.; Lu, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, L.H.; Feng, H.D.; Li, B.; Jia, W.W.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.T.; Tang, X.; et al. The efficacy of blinatumomab in the treatment of pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A multicenter study. Chin. J. Pediatr. 2025, 63, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, H.; Jhakri, K.; Al-Shudifat, M.; Sumra, B.; Kocherry, C.; Malasevskaia, I. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy in the Treatment of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Efficacy, Safety, and Future Directions. Cureus 2025, 17, e89172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, X.; Guan, Y.; Jiang, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, W.; Wu, Y. Molecular insights into chemotherapy resistance mediated by MLL-AF9 fusion gene in pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Diz, M.; Reglero, C.; Falkenstein, C.D.; Castro, A.; Hayer, K.E.; Radens, C.M.; Quesnel-Vallières, M.; Ang, Z.; Sehgal, P.; Li, M.M.; et al. An Alternatively Spliced Gain-of-Function NT5C2 Isoform Contributes to Chemoresistance in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 3327–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gimenez, A.; Ditcham, J.E.; Azazi, D.M.A.; Giotopoulos, G.; Asby, R.; Meduri, E.; Bagri, J.; Sakakini, N.; Lopez, C.K.; Narayan, N.; et al. CREBBP inactivation sensitizes B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia to ferroptotic cell death upon BCL2 inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, B.M.T.; Butler, M.; Grünewald, K.J.T.; Schenau, D.; Tee, T.M.; Lucas, L.; Huitema, A.D.R.; Boer, J.M.; Bornhauser, B.C.; Bourquin, J.P.; et al. IKZF1 gene deletions drive resistance to cytarabine in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2024, 109, 3904–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F.; Ma, X.J.; Ying, L.L.; Tong, Y.H.; Xiang, X.P. Multi-Omics Analysis of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Identified the Methylation and Expression Differences Between BCP-ALL and T-ALL. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 622393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Zhu, S.; Peng, H.; Wang, Z. Unveiling the omics tapestry of B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Bridging genomics, metabolomics, and immunomics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aertgeerts, M.; Meyers, S.; Gielen, O.; Lamote, J.; Dewaele, B.; Tajdar, M.; Maertens, J.; De Bie, J.; De Keersmaecker, K.; Boeckx, N.; et al. Single-cell DNA and surface protein characterization of high hyperdiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis and during treatment. Hemasphere 2025, 9, e70085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narang, S.; Ghebrechristos, Y.; Evensen, N.A.; Murrell, N.; Jasinski, S.; Ostrow, T.H.; Teachey, D.T.; Raetz, E.A.; Lionnet, T.; Witkowski, M.; et al. Clonal evolution of the 3D chromatin landscape in patients with relapsed pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Witkowski, M.T.; Harris, J.; Dolgalev, I.; Sreeram, S.; Qian, W.; Tong, J.; Chen, X.; Aifantis, I.; Chen, W. Leukemia-on-a-chip: Dissecting the chemoresistance mechanisms in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia bone marrow niche. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghantous, A.; Nusslé, S.G.; Nassar, F.J.; Spitz, N.; Novoloaca, A.; Krali, O.; Nickels, E.; Cahais, V.; Cuenin, C.; Roy, R.; et al. Epigenome-wide analysis across the development span of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Backtracking to birth. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, G.; Lovisa, F.; Cortese, G.; Pillon, M.; Carraro, E.; Cesaro, S.; Provenzi, M.; Buffardi, S.; Francescato, S.; Biffi, A.; et al. Phosphoproteomic Analysis Reveals a Different Proteomic Profile in Pediatric Patients With T-Cell Lymphoblastic Lymphoma or T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 913487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, Z.; Sarno, J.; Jager, A.; Samusik, N.; Aghaeepour, N.; Simonds, E.F.; White, L.; Lacayo, N.J.; Fantl, W.J.; Fazio, G.; et al. Single-cell developmental classification of B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis reveals predictors of relapse. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, A.; Glogova, E.; Peters, C.; Sedlacek, P.; Dalle, J.H.; Locatelli, F.; Meisel, R.; Burkhardt, B.; Buechner, J.; Wachowiak, J.; et al. Impact of minimal residual disease on the outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia within the FORUM Trial. Haematologica 2025, 111, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, V.W.; Sahay, S.; Vergis, J.; Weistuch, C.; Meller, J.; McCullumsmith, R.E. Pathway Analysis Interpretation in the Multi-Omic Era. BioTech 2025, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormond, K.E.; Stanclift, C.; Reuter, C.M.; Carter, J.N.; Murphy, K.E.; Lindholm, M.E.; Wheeler, M.T. Researcher views on returning results from multi-omics data to research participants: Insights from The Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium (MoTrPAC) Study. BMC Med. Ethics 2025, 26, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlgren, L.; Pilheden, M.; Sturesson, H.; Song, G.; Walsh, M.P.; Yang, M.; Maillard, M.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, Z.; Singh, V.; et al. The genomic landscape of relapsed infant and childhood KMT2A-rearranged acute leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Chen, P.; Xu, Y.; Jia, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, W.; Zhen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of thirteen-gene panel with prognosis value in Multiple Myeloma. Cancer Biomark. 2023, 38, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.M.; Singh, R.; Haugen, M.; Duff, A.; Shoop, J.; Morgan, E.R.; Rossoff, J.E.; Weinstein, J.L.; Heneghan, M.B.; Badawy, S.M. Adherence to 6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) and Habit Strength in Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL). Eur. J. Haematol. 2025, 114, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kager, L.; Boztug, K. The NUDIX hydrolase NUDT5 influences purine nucleotide metabolism and thiopurine pharmacology. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e194434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro-Navarro, J.; Alcon, C.; Dorel, M.; Alasfar, L.; Bastian, L.; Baldus, C.; Astrahantseff, K.; Yaspo, M.L.; Montero, J.; Eckert, C. Inhibiting H3K27 Demethylases Downregulates CREB-CREBBP, Overcoming Resistance in Relapsed Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Di, S.; Nie, F.; Meng, W.; Huang, S. RPS15a knockdown impedes the progression of B-ALL by inducing p53-mediated nucleolar stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 763, 151768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Leons, G.K.; Singh, V.; Naseer, S.; Ribeyron, L.; Bakhshi, S.; Gupta, R.; Gajendra, S.; Thoudam, D.S.; Sarawat, S.K.; et al. Gene expression signature of IKZF1 deleted B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia reveals a unique regulation of MUC4. Br. J. Haematol. 2025, 207, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xue, X.; Wang, H.; Hao, Y.; Yang, Q. Notch1 activation and inhibition in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia subtypes. Exp. Hematol. 2025, 148, 104771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Ishida, T.; Masaki, A.; Murase, T.; Ohtsuka, E.; Takeshita, M.; Muto, R.; Choi, I.; Iwasaki, H.; Ito, A.; et al. Clinical significance of NOTCH1 and FBXW7 alterations in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Int. J. Hematol. 2025, 121, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalska-Sadowska, J.; Dawidowska, M.; Szarzyńska-Zawadzka, B.; Jarmuż-Szymczak, M.; Czerwińska-Rybak, J.; Machowska, L.; Derwich, K. Translocation t(8;14)(q24;q11) with concurrent PTEN alterations and deletions of STIL/TAL1 and CDKN2A/B in a pediatric case of acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia: A genetic profile associated with adverse prognosis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studd, J.B.; Cornish, A.J.; Hoang, P.H.; Law, P.; Kinnersley, B.; Houlston, R. Cancer drivers and clonal dynamics in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia subtypes. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antić, Ž.; Yu, J.; Bornhauser, B.C.; Lelieveld, S.H.; van der Ham, C.G.; van Reijmersdal, S.V.; Morgado, L.; Elitzur, S.; Bourquin, J.P.; Cazzaniga, G.; et al. Clonal dynamics in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with very early relapse. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antić, Ž.; Yu, J.; Van Reijmersdal, S.V.; Van Dijk, A.; Dekker, L.; Segerink, W.H.; Sonneveld, E.; Fiocco, M.; Pieters, R.; Hoogerbrugge, P.M.; et al. Multiclonal complexity of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and the prognostic relevance of subclonal mutations. Haematologica 2021, 106, 3046–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, U.; Sagar, F.; Al Mohajer, M.; Majeed, A. Management of Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection During Intensive Chemotherapy and Stem Cell Transplantation for Leukemia: Case with Literature Review. Cureus 2018, 10, e2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Grimes, K.; Rauwolf, K.K.; Bruch, P.M.; Rausch, T.; Hasenfeld, P.; Benito, E.; Roider, T.; Sabarinathan, R.; Porubsky, D.; et al. Functional analysis of structural variants in single cells using Strand-seq. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zheng, R.; Fuda, F.; Cantu, M.D.; Koduru, P.; Jaso, J.M.; Weinberg, O.; Germans, S.; Chen, M.; Xu, J.; et al. Genomic and Clinicopathological Characterization of CRLF2-Rearranged Mixed Phenotype Acute Leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2025, 72, e31507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Liu, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Cao, J.; Yue, M.; Zhong, D.; Tang, R. Clinical features and prognosis of pediatric acute lymphocytic leukemia with JAK-STAT pathway genetic abnormalities: A case series. Ann. Hematol. 2023, 102, 2445–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.F.; Smadbeck, J.B.; Sharma, N.; Blackburn, P.R.; Demasi Benevides, J.; Akkari, Y.M.N.; Jaroscak, J.J.; Znoyko, I.; Wolff, D.J.; Schandl, C.A.; et al. Apparent coexistence of ETV6::RUNX1 and KMT2A::MLLT3 fusions due to a nonproductive KMT2A rearrangement in B-ALL. Leuk. Lymphoma 2022, 63, 2243–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ham, C.G.; Van Leeuwen, F.N.; Kuiper, R.P. Treatment-related mutagenic processes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2025, 110, 2261–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerchel, I.S.; Hoogkamer, A.Q.; Ariës, I.M.; Steeghs, E.M.P.; Boer, J.M.; Besselink, N.J.M.; Boeree, A.; van de Ven, C.; de Groot-Kruseman, H.A.; de Haas, V.; et al. RAS pathway mutations as a predictive biomarker for treatment adaptation in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2018, 32, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Waanders, E.; van Reijmersdal, S.V.; Antić, Ž.; van Bosbeek, C.M.; Sonneveld, E.; de Groot, H.; Fiocco, M.; Geurts van Kessel, A.; van Leeuwen, F.N.; et al. Upfront Treatment Influences the Composition of Genetic Alterations in Relapsed Pediatric B-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Hemasphere 2020, 4, e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.C.; Chan-Seng-Yue, M.; Ge, S.; Zeng, A.G.X.; Ng, K.; Gan, O.I.; Garcia-Prat, L.; Flores-Figueroa, E.; Woo, T.; Zhang, A.X.W.; et al. Transcriptomic classes of BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Lai, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, D.; Huang, J.; Zhou, D.; Li, Y.; et al. The potential role of RNA sequencing in diagnosing unexplained insensitivity to conventional chemotherapy in pediatric patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. BMC Med. Genom. 2024, 17, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Hu, D.; Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Wang, S. Immunometabolic Dysregulation in B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Revealed by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Perspectives on Subtypes and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, G.; Peloso, A.; Cani, A.; Mariotto, E.; Corallo, D.; Aveic, S.; Russo, L.; Cescon, M.; Santinon, G.; Frasson, C.; et al. NFATc1 and NFATc2 regulate glucocorticoid resistance in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia through modulation of cholesterol biosynthesis and the WNT/β-catenin pathway. Haematologica 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M.; Chiaretti, S.; Iacobucci, I.; Tavolaro, S.; Lonetti, A.; Santangelo, S.; Elia, L.; Papayannidis, C.; Paoloni, F.; Vitale, A.; et al. AICDA expression in BCR/ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is associated with a peculiar gene expression profile. Br. J. Haematol. 2011, 152, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, C.S.; Saw, J.; Yan, F.; Boyle, J.A.; Amarasinghe, O.; Abdollahi, S.; Vo, A.N.Q.; Shields, B.J.; Mayoh, C.; McCalmont, H.; et al. Targeting LMO2-induced autocrine FLT3 signaling to overcome chemoresistance in early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2025, 39, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, Z.; Li, L.; Huang, J.; Liu, S.; Lu, B.; Duan, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; et al. scRNA-seq reveals an immune microenvironment and JUN-mediated NK cell exhaustion in relapsed T-ALL. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Gao, G.; Xu, Y.; Jia, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, J.; Du, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Novel gene signature reveals prognostic model in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1036312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpar, D.; Wren, D.; Ermini, L.; Mansur, M.B.; van Delft, F.W.; Bateman, C.M.; Titley, I.; Kearney, L.; Szczepanski, T.; Gonzalez, D.; et al. Clonal origins of ETV6-RUNX1+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Studies in monozygotic twins. Leukemia 2015, 29, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Guillaumet-Adkins, A.; Dimitrova, V.; Yun, H.; Drier, Y.; Sotudeh, N.; Rogers, A.; Ouseph, M.M.; Nair, M.; Potdar, S.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals developmental plasticity with coexisting oncogenic states and immune evasion programs in ETP-ALL. Blood 2021, 137, 2463–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhu, S.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, X.; Xie, W.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Development of a cuproptosis-related prognostic signature to reveal heterogeneity of the immune microenvironment and drug sensitivity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullighan, C.G.; Zhang, J.; Kasper, L.H.; Lerach, S.; Payne-Turner, D.; Phillips, L.A.; Heatley, S.L.; Holmfeldt, L.; Collins-Underwood, J.R.; Ma, J.; et al. CREBBP mutations in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 2011, 471, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Jose-Eneriz, E.; Agirre, X.; Rodríguez-Otero, P.; Prosper, F. Epigenetic regulation of cell signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Epigenomics 2013, 5, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer Hackenhaar, F.; Refhagen, N.; Hagleitner, M.; van Leeuwen, F.; Marquart, H.V.; Madsen, H.O.; Landfors, M.; Osterman, P.; Schmiegelow, K.; Flaegstad, T.; et al. CpG island methylator phenotype classification improves risk assessment in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2025, 145, 2161–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.M.; Chen, H.Q.; Liu, L.T.; Zhang, Y.T.; Wang, J.; Zhou, D.H.; Fang, J.P.; Xu, L.H. Clinical characteristics and prognostic analysis of CDKN2A/2B gene in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A retrospective case-control study. Hematology 2025, 30, 2439606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, E.J.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Pham, J.; Zhao, Y.; Nguyen, C.; Huantes, S.; Park, E.; Naing, K.; Klemm, L.; Swaminathan, S.; et al. Small-molecule inhibition of CBP/catenin interactions eliminates drug-resistant clones in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncogene 2014, 33, 2169–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Wong, S.H.; Kurzer, J.H.; Schneidawind, C.; Wei, M.C.; Duque-Afonso, J.; Jeong, J.; Feng, X.; Cleary, M.L. SETDB2 Links E2A-PBX1 to Cell-Cycle Dysregulation in Acute Leukemia through CDKN2C Repression. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Tan, T.K.; Lee, D.Z.Y.; Huang, X.Z.; Ong, J.Z.L.; Kelliher, M.A.; Yeoh, A.E.J.; Sanda, T.; Tan, S.H. Oncogenic dependency on SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling factors in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2024, 38, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtonen, J.; Teppo, S.; Lahnalampi, M.; Kokko, A.; Kaukonen, R.; Oksa, L.; Bouvy-Liivrand, M.; Malyukova, A.; Mäkinen, A.; Laukkanen, S.; et al. Single cell characterization of B-lymphoid differentiation and leukemic cell states during chemotherapy in ETV6-RUNX1-positive pediatric leukemia identifies drug-targetable transcription factor activities. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; He, B.; Bogush, D.; Schramm, J.; Singh, C.; Dovat, K.; Randazzo, J.; Tukaramrao, D.; Hengst, J.; Annageldiyev, C.; et al. Critical roles of IKAROS and HDAC1 in regulation of heterochromatin and tumor suppression in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2025, 39, 2010–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Pang, Y. Successful remission induction therapy with azacitidine and venetoclax for a treatment-naive elderly patient with ETP/myeloid mixed-phenotype acute leukemia: A case report. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1628767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumel, L.; Bernardi, F.; Picard, D.; Diaz, J.T.; Jepsen, V.H.; Hasselmann, R.; Schliehe-Diecks, J.; Bartl, J.; Qin, N.; Bornhauser, B.; et al. Proteogenomic profiling uncovers differential therapeutic vulnerabilities between TCF3::PBX1 and TCF3::HLF translocated B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2024, 109, 2290–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyczynski, M.; Vesterlund, M.; Björklund, A.C.; Zachariadis, V.; Janssen, J.; Gallart-Ayala, H.; Daskalaki, E.; Wheelock, C.E.; Lehtiö, J.; Grandér, D.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in response to glucocorticoid treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordo, V.; Meijer, M.T.; Hagelaar, R.; de Goeij-de Haas, R.R.; Poort, V.M.; Henneman, A.A.; Piersma, S.R.; Pham, T.V.; Oshima, K.; Ferrando, A.A.; et al. Phosphoproteomic profiling of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia reveals targetable kinases and combination treatment strategies. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Chan, W.W.; Mohi, G.; Rosenbaum, J.; Sayad, A.; Lu, Z.; Virtanen, C.; Li, S.; Neel, B.G.; Van Etten, R.A. Distinct GAB2 signaling pathways are essential for myeloid and lymphoid transformation and leukemogenesis by BCR-ABL1. Blood 2016, 127, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lai, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, M.; Xu, B. Anlotinib exerts potent antileukemic activities in Ph chromosome negative and positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia via perturbation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 25, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Garcia, F.M.; Jenkins, Y.R.; Assmann, V.D.; Paul, S.; Sharma, N.D.; Moore, C.; Ma, E.H.; Diamanti, P.; Hennequart, M.; Blagih, J.; et al. Canagliflozin synergises with serine restriction mediating anti-leukaemic effects in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Mol. Metab. 2025, 102, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirs, S.; Van der Meulen, J.; Van de Walle, I.; Taghon, T.; Speleman, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Vlierberghe, P. Epigenetics in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 263, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvolo, V.R.; Kurinna, S.M.; Karanjeet, K.B.; Schuster, T.F.; Martelli, A.M.; McCubrey, J.A.; Ruvolo, P.P. PKR regulates B56(alpha)-mediated BCL2 phosphatase activity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia-derived REH cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 35474–35485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachón-Meza, K.L.; Moreno-Cristancho, C.E.; Padilla-Agudelo, J.L.; Ramos-Murillo, A.I.; Londoño-Barbosa, D.; Salguero, G.; Sanabria-Barrera, S.M.; Chica, C.; Cruz-Rodriguez, N.; Godoy-Silva, R.D.; et al. Integration of Metabolic Profiling and Functional Genomics Suggests IGJ as a Driver of Chemoresistance in B-ALL. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2025, 72, e32068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hamaly, M.A.; Winter, E.; Blackburn, J.S. The mitochondria as an emerging target of self-renewal in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2025, 26, 2460252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlozkova, K.; Hermanova, I.; Safrhansova, L.; Alquezar-Artieda, N.; Kuzilkova, D.; Vavrova, A.; Sperkova, K.; Zaliova, M.; Stary, J.; Trka, J.; et al. PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway alters sensitivity of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia to L-asparaginase. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakana, E.; Altman, J.K.; Glaser, H.; Donato, N.J.; Platanias, L.C. Antileukemic effects of AMPK activators on BCR-ABL-expressing cells. Blood 2011, 118, 6399–6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Liu, T.; Hao, Q.; Fang, Q.; Gong, X.; Li, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wei, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; et al. Comprehensive omics-based classification system in adult patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol. Oncol. 2025, 19, 3578–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, B.; Tükel, E.Y.; Turanlı, B.; Kiraz, Y. Integrated systems biology analysis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Unveiling molecular signatures and drug repurposing opportunities. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 4121–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavian, Z.; Nowzari-Dalini, A.; Stam, R.W.; Rahmatallah, Y.; Masoudi-Nejad, A. Network-based expression analysis reveals key genes related to glucocorticoid resistance in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cell. Oncol. 2017, 40, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamrani, S.Q.; Ball, G.R.; El-Sherif, A.A.; Ahmed, S.; Mousa, N.O.; Alghorayed, S.A.; Alatawi, N.A.; Ali, A.M.; Alqahtani, F.A.; Gabre, R.M. Machine Learning for Multi-Omics Characterization of Blood Cancers: A Systematic Review. Cells 2025, 14, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Antić, Ž.; Fardzadeh, P.; Pietzsch, S.; Schröder, C.; Eberhardt, A.; van Bömmel, A.; Escherich, G.; Hofmann, W.; Horstmann, M.A.; et al. An artificial intelligence-assisted clinical framework to facilitate diagnostics and translational discovery in hematologic neoplasia. EBioMedicine 2024, 104, 105171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Houby, E.M.F. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia diagnosis using machine learning techniques based on selected features. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, A.; Ebadi, M.; Rehman, T.U.; Elhusseini, H.; Halaweish, H.; Kaiser, T.; Holtan, S.G.; Khoruts, A.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Staley, C. Compilation of longitudinal gut microbiome, serum metabolome, and clinical data in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsagaby, S.A. Omics-based insights into therapy failure of pediatric B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncol. Rev. 2019, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Qin, M.; Jia, C.; Wang, B.; Zhu, G.; Zheng, H. Prognostic Impact of the Level of Minimal Residual Disease Prior to Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation on Pediatric Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A 10-Year Single-Center Study. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Wu, Q.F.; Ren, A.Q.; Chen, Q.; Shi, J.Z.; Li, J.P.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.J.; Tang, Y.Z.; Zhao, Y.; et al. ATF4 renders human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell resistance to FGFR1 inhibitors through amino acid metabolic reprogramming. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 2282–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Feng, B.; McClory, S.E.; de Oliveira, B.C.; Diorio, C.; Gregoire, C.; Tao, B.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Peng, L.; et al. Single-cell CAR T atlas reveals type 2 function in 8-year leukaemia remission. Nature 2024, 634, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.X. Comprehensive omics profiling in acute myeloid leukemia: From molecular landscape to clinical translation. Curr. Proteom. 2025, 22, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vllahu, M.; Savarese, M.; Cantiello, I.; Munno, C.; Sarcina, R.; Stellato, P.; Leone, O.; Alfieri, M. Application of Omics Analyses in Pediatric B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertgeerts, M.; Meyers, S.; Demeyer, S.; Segers, H.; Cools, J. Unlocking the Complexity: Exploration of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia at the Single Cell Level. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2024, 28, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Khan, A.H.; Bilal, S.F.; Li, J. Deep learning approaches for resolving genomic discrepancies in cancer: A systematic review and clinical perspective. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.