Abstract

The one health approach recognizes the interconnection between human, animal, and environmental health, emphasizing that human health should never be threatened in the pursuit of agricultural productivity. Indeed, within agricultural systems, this approach is particularly relevant, as the overuse of chemical inputs and the mismanagement of organic wastes can directly threaten human health. Overuse of chemical inputs can result in various health disturbances and contribute to the development of acute or chronic human diseases. Likewise, organic wastes constitute potential human health risks due to the presence of pathogens in these wastes such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Despite increasing research, many studies often lack integrated risk assessments of agrochemicals and organic waste within a “One Health” framework, leaving gaps in practical guidance for safe agricultural management. This review was conducted to address these gaps and answer the following questions: What are the human health risks associated with agrochemicals and mismanaged organic wastes? How can composting/compost mitigate these risks and support sustainable agricultural production? It examines the role of composting in managing organic wastes, producing high-quality compost, and reducing exposure to hazardous chemicals and pathogens. Furthermore, it outlines key characteristics of compost required to ensure safety for humans, plants, soil, and ecosystems. By integrating evidence on human health and crop productivity, this review provides insights for safe, sustainable agricultural practices within a unified One Health framework.

1. Introduction

The economic growth and rising food consumption resulted in the expansion of intensive agricultural systems, which rely heavily on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides to sustain high productivity [1]. This reliance has led to widespread environmental pollution and increased human exposure to harmful agricultural pesticide residues. It has been highlighted that agrochemicals are frequently used at rates exceeding crop requirements [2], contributing to soil degradation, biodiversity loss, and chronic health effects among exposed populations. Several workers have linked both acute and chronic exposure to fertilizers and pesticides to many diseases including cancer, Parkinson’s disease, asthma, and hepatic and renal toxicity [3,4,5,6,7].

Alongside chemical inputs, manure remains a commonly used soil amendment regarding its beneficial effects on soil and plant productivity. However, it can present a potential risk to human health due to the existence of pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. In addition, mismanaged manure could serve as a critical pathway for the dissemination of zoonotic diseases and human pathogens [8]. These issues highlight growing concerns about the sustainability and safety of conventional agricultural practices.

In response to these concerns, sustainable agriculture was emerged to overcome the limits of the conventional agricultural practices and mitigate their environmental and health impacts [9]. This transitional phase emphasizes the need for safe, environmentally friendly, and health-protecting alternatives for agricultural chemicals and untreated organic waste [10]. Organic amendments (e.g., compost) are among the available sustainable and human healthy options to improve soil fertility, plant health, and crop yield and quality without the adverse effects linked to mismanaged manure and to agrochemical overuse.

To strengthen this transition, compost and its extract commonly called compost tea are currently used in agriculture and horticulture. Their application was shown to improve soil fertility and plant health by improving soil organic matter and macro- and microelements [11,12,13], increasing cation exchange capacity [14], and improving the soil water retention capacity [15]. In addition, compost and compost tea exert a suppressive effect on soil-borne pathogens [16,17], and contribute to the increase in gas exchanges and microbial activity [18]. The incorporation of compost in soils was shown to improve the plant biomass, root growth and development, and productivity and yield of different crops [13,19,20,21,22,23]. Despite its effectiveness, only safe, quality, and mature composts can be used, based on some criteria, thereby ensuring benefits for plants and ecosystems as well as humans, within a One Health framework.

Despite growing interest in the One Health framework, gaps remain in assessing human health risks of agrochemicals and mismanaged organic wastes, as well as in evaluating the effectiveness of composting for safe waste management. Limited studies address criteria for producing high-quality compost. Our review addresses these gaps by synthesizing current knowledge and highlighting how compost can serve as a safe and sustainable solution while integrating human health, soil quality, and crop productivity.

In view of the above, this review aims to discuss the human health risks of agrochemicals and organic wastes, to emphasize the role of composting in managing these wastes, and to produce a quality compost that can be used as both an organic amendment and disease control product. In addition, this review also focuses on describing the characteristics required before the use of compost to prevent possible negative impacts on human health, soil, plant, and ecosystems. By integrating human health, soil quality, and crop productivity, our work provides a novel perspective within the One Health framework, emphasizing the interconnections between agricultural practices and public health.

2. Data Collection and Database Sources

To ensure a comprehensive and critical synthesis of the current knowledge, the literature used in this review was identified through a broad search of recent and foundational publications related to the topic (older references were included when they provided essential baseline information or historically significant data). Articles were selected based on their scientific relevance, the robustness of their methodology, and their contribution to understanding the agronomical, environmental, and health implications discussed. We compiled evidence through diverse databases including Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. Keywords used for search process included, but were not limited to, the following: agrochemicals, pesticides, fertilizers, organic wastes, human health risks, composting, compost, compost tea, pathogens, food safety, one health, sustainability. A total of more than 500 articles and documents were screened, and more than 138 of the relevant sources aligned with the objectives of this review were retained and provided in the reference section.

3. Human Risks Associated with Overuse of Agrochemicals

The widespread application of agrochemicals including pesticides and fertilizers played a key role in ensuring global food security. According to FAO, the global fertilizer consumption exceeds 200 million tons annually [2]. However, crops absorb only a limited proportion of applied agrochemicals, while a considerable fraction is lost to the environment, suggesting substantial overuse and inefficiency [24]. For instance, around one-third of applied N is taken up by some crops while the rest is lost to the environment, reflecting widespread inefficiency and potential overuse [25]. Similarly, phosphorus recovery efficiency varies widely, but assessments show that a substantial fraction of applied P fertilizer is not taken up by crops, especially in P-fixing soils, where much of the added P becomes immobilized rather than absorbed [26]. Pesticide application is also highly inefficient, as less than 0.1% of sprayed pesticides reach the target pest, while the remaining >99% disperse into the surrounding environment, contributing to contamination of air, soil, water, and food chains, and affecting public health [27].

Their overuse has raised concerns related to their effects on environmental and human health [3,4,5,6,7]. Agrochemicals may enter the human body from oral, respiratory, dermal, and eye pathways involving various routes such as food chain, air, water, soil, flora, and fauna [6,28]. Many studies have linked both acute and chronic agrochemicals’ exposures to several diseases. A recent systematic review suggested the possible association between chemical fertilizers and increased risks of cancers and underscored that some inorganic fertilizers may contain significant amounts of heavy metals like Pb, Cd, and As that contaminate soil, water, and foods and lead to possible long-term health problems like carcinogenesis and renal damage [3]. Similarly, Kim et al. [6] and Asghar et al. [7] emphasized that many diseases and physiological perturbations including asthma, neural defects, Parkinson’s disease, leukemia, and some other cancers could be associated with utilization of agrochemicals, mainly pesticides exposure. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals by consumption of contaminated food and water may lead to anemia, complications during pregnancy, kidney malfunctioning, and cancer in severe cases [29]. Tasleem et al. [30] revealed that some agrochemicals such as NPK-fertilizers and TSP contain higher concentrations of Cd, Pb, Cr, and Cu, leading to contamination of crops such as potato, onion, and brinjal. These authors also highlighted the increased bioaccumulation risk of some heavy metals along the food chain [30]. The study conducted by Naz et al. [5] assessing the heavy metals in wheat and rice revealed that these crops accumulate more heavy metals when farmers use chemical fertilizers. The authors indicated that fertilizers accumulate in plants and soils, representing a high risk to enter the food chain, and highlighted the human health risks associated with the long-term exposure to contaminated food and water including renal and hepatic toxicity, neurological disorders, and carcinogenic effects [5]. In addition, many studies have highlighted that over application of nitrogen fertilizers leads to nitrate leaching in drinking water that could bioaccumulate in the human body, resulting in carcinogenesis [3,4,31].

Overall, research has clearly demonstrated the health risks associated with exposure to agricultural chemicals; however, the current evidence base is far from consistent. Studies often differ in how they measure exposure, the environmental contexts examined, and the populations assessed, leading to significant variations in reported outcomes. Many scientifically described associations still need to be substantiated, as long-term cohort studies and biomonitoring data remain scarce. Climatic conditions, geographic location, soil composition, agrochemical doses, and farming practices are factors that can complicate comparisons between studies and contribute to inconsistent findings on pollution and bioaccumulation. Consequently, several critical gaps remain as pointed out by Zhou et al. [32], who highlighted several gaps in the research on human health risks associated with agrochemical use, such as research on the health and environmental impacts of mixed chemical residues, better differentiation between chronic and long-term exposures, more detailed assessments of impacts on non-target species, and the development of long-term studies capable of capturing cumulative risks.

4. Sanitary Risks of Mismanaged Organic Wastes

Due to human behavior, consumption patterns, and population growth, around 38 billion metric tons of organic wastes are annually generated worldwide [33]. These wastes are typically dumped or incinerated. The organic wastes, especially originating from animals, namely manure, present a potential risk to human health due to the existence of pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Environmental mismanagement of animal manure serves as a critical pathway for the dissemination of zoonotic diseases and human pathogens [8]. These pathogens could infect humans directly through the handling or processing of manure, or indirectly via contaminated meat, milk, or water as well as by bio-aerosol for farmers [8]. Several studies found that organic wastes, especially untreated manure, contain pathogens with a high probability of dissemination through water source contamination and contaminated crops, leaching into ground water, and surface run-off [3,34,35]. According to Hembach et al. [36], all the analyzed manures contained human pathogenic bacteria such as Enterococcus faecium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and E. coli as well as resistance genes against antibiotics usually applied in veterinary therapies. Some clinically critical resistance genes against reserve antibiotics for human medicine were also found in manures more frequently than in hospital wastewater. Findings from the study of Atidégla et al. [37] revealed that the application of poultry manure leads to the contamination of three vegetables, namely carrot, eggplant, and tomato, by human pathogen bacteria such as fecal coliforms, Escherichia coli, and fecal streptococci. Other pathogens like E. coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, and Providencia spp. could be found in manure, as in the review by Black et al. [34]. Likewise, Zhu et al. [38] detected 157 human bacterial pathogens in soils amended with manure with a significant potential risk to public health through the consumption of contaminated crops or direct contact with soil. The study also identified virulence factor genes as well as antibiotic resistance genes in the manure-amended soils, indicating that the manure application may enhance the pathogen virulence and facilitate the transfer of these genes to human pathogens, thereby complicating treatment strategies [38]. Regarding the public health concern, investigations revealed that an outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections was attributed to pull and horse manures, demonstrating the public health risks associated with manure mismanagement [39]. Similarly, results suggested that field application of manure played a crucial role in the dissemination of Q-fever in the Dutch Q-fever epidemic of 2006–2010 in the Netherlands [35]. In addition, the landfill leachate generated from the organic wastes could contain notable concentrations of organic carbon, nitrogen, ammonia, chloride, fluoride, heavy metals and also be characterized by high biological and chemical oxygen demand [40,41,42]. Although studies clearly demonstrate the presence of pathogens in manure, the results are inconsistent regarding the pathogen species, their prevalence, and contamination levels, reflecting differences between studies such as sampling methods, environmental conditions, and the type and origin of studied manures. Most studies are short-term or cross-sectional, which limits our understanding of pathogen persistence, gene transmission, and their long-term public health effects, as well as their direct and indirect impact on specific aspects of human health. Furthermore, few studies and investigations directly examine the relationship between manure use and the incidence of human diseases, such as the study on the dissemination of Q-fever in the Dutch Q-fever epidemic of 2006–2010 in the Netherlands [35], making conclusions regarding the manure–human disease relationship somewhat complex and not evident. There is also a lack of standardized methods for monitoring disease pathogens transmitted through animal manure and assessing associated health risks, leaving significant gaps in evidence-based risk management and mitigation strategies.

5. Composting for Human Pathogen Control and Production of Safe Organic Fertilizer

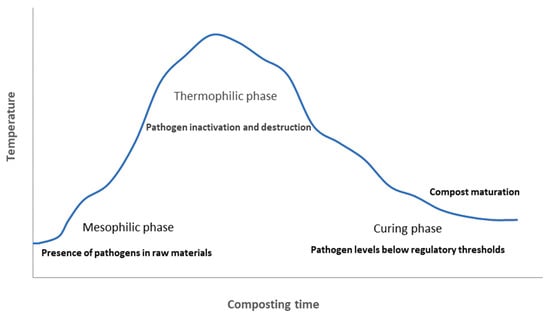

Given the potential risks associated with raw organic wastes and untreated manure application, compost offers a sufficient, sustainable, and healthy safe alternative with high potential on agronomic scale. Composting is a biological transformation process that ensures the hygienic transformation and stabilization of complex organic materials, usually derived from plant debris and animal wastes, in the presence of adequate moisture and temperature. This controlled process reduces waste volume, minimizes environmental nuisances, and ensures hygienization through the destruction of pathogenic microorganisms [43,44]. A mature compost is therefore characterized by its stable physical and chemical properties, absence of phytotoxicity, and compliance with microbial safety standards [45]. The hygienic efficiency of composting is mainly attributed to the thermophilic phase of the process, during which high temperature maintained long enough by thermophilic microorganisms inactivates and destroys both zoonotic and human pathogens [46,47] (Figure 1). For instance, due to the heat generated during composting, the viability of Ascaris lombricoïde eggs was completely lost at the end of the process, producing a final compost that meets the recommendations for safe and sustainable agricultural, thereby allowing limiting health risks associated with helminths [48]. Typically, pathogens are destroyed when they reach their thermal death points, which depend on the temperature and time of treatment. Likewise, other mechanisms could be involved in pathogen suppression such as microbial antagonism, production of antimicrobial compounds, competition for space and nutrients, pH variations, and release of chemical compounds [49,50]. Composting further reduces, in addition to microorganisms, nuisance odors and insect proliferation associated with manure, which may otherwise contribute to diseases transmission [46]. The effectiveness of composting as a hygienic process has been demonstrated by several studies, including the work of Xu et al. [51], who underscored that on-site composting of cattle carcasses and manure resulted in high degradation of cattle carcasses and fast and complete destruction of pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7 and Newcastle disease virus as well as a significant reduction in Campylobacter jejuni population, suggesting that bio-secure composting systems enable the management of manures and even animal carcasses in infectious disease outbreaks. In our previous research, we highlighted that adequate composting processes produce composts without any sanitary risk since the concentrations of pathogen indicators namely E. coli, Clostridium perfringens, Enterococcus, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., and viable helminth eggs were below suggested limits [16].

Figure 1.

General temperature dynamics and pathogen inactivation during the composting process.

6. Agronomic Beneficial Effects of Compost

6.1. Soil Properties

6.1.1. Soil Organic Matter

Soil organic matter (SOM) depletion is one of the main factors leading to the loss of ecosystem services and resilience [52]. While the soil mineral nutrients could be improved via the application of mineral fertilizers, the SOM is improved exclusively by the application of organic amendments. The compost is the sustainable organic amendment and the efficient way to improve the SOM level [53]. Chehab et al. [54] found that the amendment of olive soil with olive pomace compost increased the SOM content by more than 185%. Similarly, Lee et al. [55] noted that SOM concentration was significantly increased in organic, micro-aggregate, and macro-aggregate soil fractions, as a response to the continuous application of mature compost. Garratt et al. [56] found that the SOM increase leads to an improvement of crop yield across 84 fields in five European countries. The increase recorded in SOM is generally attributed to the large amount of OM supplied to the soil through compost application [54]. It has been found that the utilization of various organic amendments including compost made from household wastes increased significantly the soil OM by increasing the organic carbon from 0.69% to 1.74% [57]. Similarly, the increased SOM response under organic amendments is ascribed to the increase in external organic C inputs [58].

6.1.2. Soil Mineral Nutrients

Compost contains all of the essential plant nutrients namely macro- and microelements. The examination of compost’s effect on soil chemical properties revealed that the amount of available N, P, and K as well as the concentrations of microelements such as Mn, Fe, Cu, and Zn were increased following the application of compost [59]. The workers reported that the increase in soil mineral nutrients content is correlated with the increase in the amount of applied compost [59]. Mohamedelnour et al. demonstrated that N, P, and K concentrations increase as the amount of applied compost increases [60]. It has been confirmed that the incorporation of compost in nutrient-deficient soil at two experimental sites significantly increased the soil-available P [61]. Likewise, the organic amendments significantly increased the olive soil’s N, P, and K by 100, 13, and 123%, respectively [. Microelements like Cu, Mn, Zn, and Fe are vital nutrients for crop production and food quality. Results obtained by Dhaliwal and Dhaliwal [62] demonstrated that the organic amendments along with mineral fertilizers increase significantly the Zn and Cu contents as compared to the unique application of mineral fertilizers. The improvement of soil nutritional status is principally due to the compost’s richness of mineral nutrients and to the degradation of its OM releasing mineral elements [54,63].

6.1.3. Soil Physical Properties

The impact of adding compost on the soil physical properties has been widely studied. Soil physical properties, namely soil available moisture, soil bulk density, field capacity, and soil porosity, were significantly improved through compost application [64]. It positively affects the soil structure by decreasing its density and increasing its porosity [53]. Due to the high bulk density, soil compaction can limit root growth, inadequate aeration can occur in wet soil, and excessive soil strength occurs in dry conditions [65]. Numerous studies have clearly demonstrated that the incorporation of compost at different depths and at different rates reduces significantly the bulk density [66,67,68,69]. It has been found that compost application in paddy soils significantly decreased the bulk density and increased its porosity by increasing the portion of large-size aggregates at the expense of small ones [55]. According to Bouajila and Sanaa [57], the application of sufficient amounts of compost allowed better water infiltration compared to the non-amended soils. The same result was found by Adugna [53], who showed that the compost incorporation increases the water holding capacity. Moreover, reduced erosion could be related to the best soil structure following the application of compost, and accordingly result in better pore volume, infiltration rate, and stability [53].

6.1.4. Soil Biological Properties

In addition to its particular physical and chemical characteristics, compost is an ideal substrate where beneficial microorganisms are living [70]. For healthy soil, soil microbial diversity and activity are considered as key factors for nutrient cycling and other biological processes [71]. Somerville et al. [72] found that compost application improved the biological properties of soil through the increase in the microbial activity at two different experimental sites. Furthermore, Brown and Cotton [73] noted a significant increase in the microbial activity in soils receiving compost. Similarly, Zhen et al. [74] demonstrated that compost application resulted in higher levels of soil respiration rate, microbial biomass, cultivable microorganisms, and microbial enzyme activities. It has been highlighted that compost enriches soil with beneficial microorganisms that contribute to the transformation of insoluble matter into assimilated nutrients, the degradation of harmful substances, and the enhancement of soil properties, leading to an improvement of the biological diversity in the soil [71].

6.2. Plant Productivity

Due to its positive effects on the soil properties, compost application leads to the stabilization of and increase in crop productivity and quality [53]. Wei et al. [58] investigated the effect of different organic amendments including compost on crop productivity and found that the yield of wheat, maize, and rice increased on average by more than 114%, 84%, and 31%, respectively, following the application of organic amendments. Caporale et al. [75] demonstrated that green compost application improves the hydraulic and physico-chemical properties of low-fertile alkaline substrate’s Mars simulants, and thus the applied compost makes the regolith a suitable substrate for cultivation of lettuce. In a recent study, Filipović et al. [76] tested the effect of different doses of compost made from medicinal plant wastes on pot marigold productivity and flower quality and found that continuous application of this compost at 30 kg/m2 improves the fresh and dry flower yield and increases the content in total carotenoid, flavonoid, and phenolic compounds. Similarly, it has been found that compost amendment increases significantly olive tree performance by improving the olive tree growth and yield, and the maximum yield of photosystem II [54]. The application of different composts at two doses (5% and 10%) resulted in increasing the shoot and root dry biomasses of alfalfa, improving the above- and belowground biomasses of wheat, and plant growth of tomato [77]. These researchers also found that the application of compost under field conditions increased the yield and growth of several crops including vegetable crops such as leek and lettuce, leguminous like alfalfa, and cereals like wheat [77]. Benabderrahim et al. [78] demonstrated that the application of compost at 30 t ha−1 improved significantly the fresh biomass of alfalfa by more than 20% as well as the grain yield and plant growth rate. In addition, this dose of compost enhanced the mineral nutrition of alfalfa for both phosphorus and nitrogen compared to non-amended plots [78]. The effect of compost on crop productivity is generally more pronounced when applied for the long term as compared to short-term application due to the low mineralization rate and slow release of nutrients. The long-term application of compost proved its effect in the equalization of the seasonal and annual fluctuations regarding water, air, and heat balance of soil, as well as the availability of nutrients for plant roots, and as a result the final crop yields [75]. More studies on the effect of different composts on soil fertility and productivity of several crops under various conditions are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Effects of compost application on plant and soil under various experimental conditions.

6.3. Control of Plant Pathogens

Biocontrol of soil-borne pathogens using compost is currently an established horticultural approach due the relevant results obtained in this context. Indeed, plant disease suppression via compost was suggested for the first time by Hoitink et al. [85] and confirmed by several workers [16,17,86,87]. Yogev et al. [88] proved the ability of three composts derived from plant residues to control various special forms of Fusarium sp. The suppressive effect of compost is attributed to biotic and abiotic modes [89]. Milinković et al. [90] found that compost derived from urban green spaces contributes to the suppression of plant pathogenic fungi, resulting in improving the overall environmental quality. The identification of the mechanisms behind disease suppression is crucial in order to increase the effectiveness of composts in crop protection and soil health.

6.3.1. Biotic Effect

This mode involves several mechanisms which are generally the main factors intervening in plant disease suppression.

- Spatial and nutritional competition

Compost contains diverse microorganisms, which transform it from a sample substrate to a bio-inoculant that confers to the amended soil the ability to be supplied by microorganisms. Therefore, the compost microorganisms occupy the soil and then exert a competition effect against the soil pathogens. Indeed, in all ecosystems, microorganisms are competing for both nutrients and space [87]. Hoitink and Changa [91] emphasized that beneficial microbiota competes with pathogens in the rhizosphere. According to Diánez et al. [92], this competition plays a key role, especially in the nutrient-dependent pathogens, and it involves not only the nutritional competition but also the competition for root colonization and infection sites. For instance, Phytophthora nicotianae, a fungus depending on the exogen carbon sources required for the germination of spores and the infection of host plants, is considered sensitive to microbial competition [93]. Kyselková and Moënne-Loccoz [94] underscored that Pseudomonas sp. plays a crucial role in disease suppression due to its competitive nature against soil-borne pathogens.

- Production of antimicrobial substances

The autochthone microorganisms of compost are able to produce some substances known by their antimicrobial activity. This activity could be exerted by specific or non-specific substances, antibiotics, lytic enzymes, or other substances [87]. This mechanism named antibiosis refers to the association of different microorganisms, generally pathogens and biocontrol agents, in which the pathogen is affected by the suppressive microorganisms via the secretion of antimicrobial substances released during their coexistence in the same space. San Fulgencio et al. [95] found that compost limits the development of the disease caused by Phytophthora capsici due to some autochthone microorganisms that produce some metabolites such as siderophores, salicylic acid, cyanide, and chitinase-like enzymes known by their antifungal activity.

- Hyperparasitism

Some organisms such as obligate bacterial pathogens, facultative parasites, and predators are known by their direct attack [96]. As declared by Pal and Gardener [97], Pasteuria penetrans is a typical example of hyperparasitism bacteria exerting a suppressive activity against root-knot nematodes. Beneficial microorganisms in compost are able to parasitize or lyse the fungal mycelium, inactive sclerotia, hyphae, or spores of several soil pathogen fungi [87].

- Induction of systematic resistance

Plants amended with compost have been shown to be colonized by a wide variety of microorganisms capable of inducing systemic resistance leading to the activation of host plant resistance mechanisms against pathogens [86]. Compost has exerted a suppressive effect on root rot and anthracnose of cucumber due to its systemic effect on the plant resistance mechanisms as well as on its enzymatic and hormonal activities [98]. Similarly, the application of the oak-bark compost enhanced plant resistance to Phytophthora infestans in whole plant and on detached leaves due to the activation of induced systemic resistance in plant tissues [99].

6.3.2. Abiotic Effect

The physical and chemical properties of compost play an important role in the suppression of soil pathogens. Several studies showed that the pH of compost could affect the growth and proliferation of soil pathogens [100]. On the other hand, Pane et al. [101] detected a negative correlation between the salinity of compost-amended substrates and damping-off in Lepidium sativum, indicating the impact of salinity on the growth, proliferation, and infectivity of the plant pathogens. In addition, the suppressive effect could also be partially caused by the phenolic compounds, humic molecules, and other antifungal substances existing in the compost teas [102,103]. Some compost compounds contribute to plant protection by improving the nutritional status of plants, inducing systemic resistance, or directly by affecting pathogens through toxicity [87].

7. Compost Maturity and Quality Indicators

Immature and unstable composts may pose serious problems during storage, marketing, and use [104]. Compost maturity and stability are two principal criteria that define its quality. According to Sayara et al. [71], maturity is related to the absence of negative effects on plant growth and development, while stability refers to the resistance of organic matter against extensive biodegradation and microbial activity. Therefore, a quality compost is a stable and mature one that exhibits some characteristics indicating its probable use without negative impacts on human, soil, plants, and ecosystems [104].

7.1. Sensory Indicators

Mature and stable composts are generally characterized by their ambient temperature, dark color, and pleasant odor, and by the absence of ammonia odor and non-decomposed materials [43].

7.2. Physico-Chemical Characteristics

7.2.1. Moisture

An acceptable limit for moisture content is required in order to avoid the water selling and to prevent the development of anaerobic conditions [105]. The low moisture indicates that the compost is unstable due to low watering during the composting process or that the compost has been stored for a long period [106]. Lasaridi et al. [105] stated that the most commonly encountered compost moisture limit is 45%.

7.2.2. pH

Several researchers have considered pH as one of the first indicators of compost quality [43]. The pH value depends on the composition of the inputs, the N content, and the nitrification intensity during composting [107]. Mature composts have a pH between 6 and 8 [106].

7.2.3. Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC)

The ability of humic compounds to adsorb positively charged ions and to easily exchange them with other cations on the same adsorption sites refers to CEC [43]. According to Wichuk and McCartney [108], the CEC increases during the composting process as organic materials are humified and carboxyl and phenolic functional groups are formed. A CEC of at least 60 cmol kg−1 is generally considered indicative of mature compost [109].

7.2.4. Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio

According to the maturity index developed by CCQC [104], composts must first have an acceptable C/N ratio before an assessment of the other quality and maturity criteria. The research conducted by Ko et al. [107,110] showed that the C/N ratio decreased during the composting. The maturity of compost is commonly characterized by a C/N ratio that should not exceed 20 [111].

7.2.5. Humification

During composting, humic substances are produced with an increase in humic acids (HAs) and a decrease in fulvic acids (FAs) contents [112]. Therefore, the humification ratio (HA/FA) of compost increases as its maturity increases. Values less than one characterize immature composts, and values of more than three characterize mature composts [43].

7.3. Biological Characteristics

7.3.1. Biological Oxygen Demand

The compost stability and maturity can be evaluated through the respiration measure, which is a mean indicator of the microbial activity [112]. Immature composts are characterized by a high rate of O2 demand and CO2 production caused by intense microbial activity [43]. This activity leads to an intense degradation of the materials and therefore to a high oxygen demand in comparison with mature and stable composts which are less active [43].

7.3.2. Phytotoxicity Level

One of the most important criteria that indicate the maturity of compost is the absence of any negative effect on plant growth. Kapanen and Itavaara [113] mentioned that a germination test is one of the most common techniques for assessing the phytotoxicity level of compost. Cress (Lepidium sativum L.) is the plant frequently used for this test because of its high sensitivity to toxicity and its quick germination [114]. Zucconi et al. [115] suggested that values of the germination index less than 50% indicate the high phytotoxicity of compost, values between 50% and 80% indicate moderate phytotoxicity, and values more than 80% indicate the absence of phytotoxicity.

7.3.3. Sanitary Quality

National compost standards include compost sanitization criteria for human pathogens (e.g., Salmonella, Enterococcus, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Clostridium perfringens) and, as a result, the presence of pathogen microorganisms is a limitation for the use of composts. According to standard NF U 44–095 [16], concentrations of pathogens in compost must be below the required thresholds of 103, 104, and 105 CFU/g for C. perfringens, E. coli, and Enterococcus, respectively, while Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, and viable helminth eggs must be absent in compost [16]. The effect of the temperature/time combination during the composting process plays an important role in the elimination of pathogens [116]. Thus, poorly hygienic compost indicates an ineffective composting process leading to the production of non-mature composts.

7.3.4. Weed Seeds

The absence of weed seeds is among the criteria used to characterize the compost quality [117]. The high temperatures during composting play a critical role in inhibiting the viability and germination of weed seeds and, as a result, the mature compost is considered weed-free and suitable to be used in agriculture [118]. Indeed, Grundy et al. [119] reported that the viability of weed seeds was inhibited when a temperature of 55 °C occurred for 3 days during the composting of municipal wastes.

8. Compost Tea

Application of compost to soil, whilst effective in restoring soil fertility and biological control of soil-borne pathogens, is sometimes limited in responding quickly and effectively to all nutrient deficiencies and diseases [120]. Consequently, the water extract of compost, commonly called compost tea, could be a source of soluble nutrients and active microorganisms and molecules that may have the capacity to enhance the plant growth and control the plant pathogens. Eudoxie and Martin [120] declaimed that compost tea is a derivative of compost that provides an opportunity to increase the benefits of soluble components preexisting in compost.

8.1. Production Process

The preparation of compost tea can be under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. The physico-chemical composition and microbial properties of compost teas and, therefore, their effectiveness in terms of fertilization and biocontrol are closely affected by the aeration, the compost source, the compost to water ratio, the brewing time, and the type of nutrient additives [9,120,121]. Table 2 shows some examples of studies testing the effect of these parameters on the aerated compost tea quality.

Table 2.

Main parameters involved in the production of aerated compost tea.

8.1.1. Compost Source

Investigations on the compost teas prepared from different raw materials revealed the relevance of compost source in the compost tea quality. Scheuerell and Mahaffee [127] declared that the compost source is one of the most important factors influencing the quality and efficiency of teas. Usually, the compost used must be mature, free from pathogens and toxic substances, and characterized by suitable moisture content (no more than 45%).

8.1.2. Aeration

The preparation of compost tea can be conducted under aerobic or anaerobic conditions [123,128]. However, various researchers have demonstrated that the aeration of compost teas during extraction improves significantly their properties [121,129]. Lastly, attention is being given to aerobically produced compost teas. Generally, a concentration of 5 ppm of dissolved oxygen is considered by several workers as the minimal aerobic level required for supporting a diverse microbial population [122,125].

8.1.3. Compost to Water Ratio

Compost to water ratio is an important factor influencing the nutritional and microbial status of the final product [128]. Researchers have worked with several ratios ranging from 1/1 to 1/1000 (w/v) [123,130]. With highly concentrated teas, there is a risk of oxygen deficiency, occurrence of anaerobic conditions during the brewing, and probable phytotoxicity of final compost teas. In contrast, diluted teas could be not efficient as a fertilizer due to the low concentrations of nutrients and beneficial microorganisms, and could also be less effective in plant disease suppression [9]. Accordingly, the recommended ratios are generally between 1:3 and 1:10 [131].

8.1.4. Brewing Time

The extraction time is a crucial factor in the preparation of compost teas. After mixing the compost with water at a suitable ratio, and supplying the system with sufficient oxygen, the extraction process could be conducted for 18 h to 72 h [124,131]. At a short brewing time, the extraction would not be sufficient to extract all nutrient categories from compost or for the growth, proliferation, and activation of compost-inhabiting microorganisms. However, at a long brewing time, the anaerobic conditions could be established in the culture, leading to the growth of anaerobic and pathogen microbes over aerobic microorganisms. Shrestha et al. [123] examined the evolution of the microbial activity during the aerated extraction at three time points (12, 24, and 48 h) and found that 48 h is the suitable extraction time, characterized with the highest microbial activity. Naidu et al. [124] found that the maximum number of microbial populations was recorded after 72 h of brewing.

8.1.5. Nutrient Additives

In addition to these factors, the effect of supplying the teas with nutrient additives during the extraction process was evaluated by several workers [9,124,125]. Additives such as molasses, kelp extract, and humic acid are commonly used as microbial food sources [121,124]. Their addition during brewing of aerated tea was found beneficial in improving the microbial activity of the finished product, and thus, its quality [125]. Shrestha et al. [123] found that the enzymatic activity and microbial population were higher in compost teas supplemented with additives compared to non-enriched teas. These additives improve the microbiological properties of the compost teas because they contain carbon chain acids that provide an essential nutrient source required for the proliferation of microorganisms [124,132]. The concentration of mineral nutrients was significantly higher in compost teas supplemented with different additives compared to teas prepared without additives [125].

8.2. Compost Tea as Biofertilizer

Compost tea is considered as a source of fine particulate organic matter, organic acids, active microorganisms, and soluble mineral nutrients [133]. Several studies have shown that compost tea improves crop yield, nutritional quality, and soil properties [133,134]. González-Hernandez et al. [134] found that weekly application of 40 mL of compost tea via irrigation reduced the number of days to flowering and increased plant height, stem diameter, shoot dry weight, and fruit weight of pepper. Similarly, Samet et al. [135] reported that compost tea increased plant length, stem, and root fresh biomass as well as potato vigor. Recently, it has been revealed that the application of compost tea improved the enzymatic activities and total soluble sugars in plant tissues, and concluded that the combination of compost tea with beneficial bacteria had beneficial effects on the growth and quality of sugar beet growing under both drought and saline stresses [136]. In addition to soil application, compost teas could be applied by spraying, as noticed by Villecco et al. [137], indicating that a compost tea prepared from artichoke and fennel composted residues resulted in a significant impact on nursery performances of tomato, pepper, and melon.

8.3. Compost Tea as Biocontrol Solution

In addition to their role in promoting plant growth and development, compost teas also protect plants against pathogens [134] and thus could be used in some cases as a sustainable alternative to synthetic fungicides in order to control plant diseases without harmful effects on the environment [138]. The biocontrol effect of compost tea against Fusarium solani was proved by Samet et al. [135], indicating that the antagonistic effect is associated with a noticeable increase in the pathogenesis-related protein expression and antioxidant enzymes and a decrease in disease severity. Similarly, Li et al. [118] found that compost tea mediates the induction of resistance mechanisms in strawberry against Verticillium wilt by increasing the activities of polyphenol oxidase and peroxydase and reducing malondialdehyde accumulation in plant tissues. The biocontrol effect is also attributed to the antagonistic microorganisms of compost tea exerting an inhibitory effect on pathogens [118]. In addition, the application of compost tea significantly decreased the preemergence and postemergence of damping-off, enhanced plant survival, and increased total phenol content in bean plants [138].

9. Recommendations and Prospects for Human Health and Environmentally Safe Composting

Based on discussions developed throughout this review, several recommendations and prospects could be emphasized:

- -

- Strengthen the enforcement and monitoring of existing compost sanitation standards to ensure reliable pathogen reduction and better protect public and environmental health.

- -

- Develop standardized, long-term epidemiological and biomonitoring studies to clarify causal links between both agrochemical exposure and mismanaged organic wastes and health outcomes as well as to address current evidence gaps.

- -

- Avoid the direct use of raw manures as organic amendment due to their probable impacts on soil, plant, environment, and human health.

- -

- Adopt composting as a safe process to manage organic wastes, principally manure;

- -

- Maintain appropriate composting conditions to mitigate environmental risks such as gas emissions, leaching, and nutrient losses.

- -

- Incorporate mature compost into fertilization and plant protection programs to reduce over-reliance on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

- -

- Apply strict conditions during the preparation of compost teas to produce high-quality and safe products.

- -

- Consider the interrelationship between human health, environmental protection, and agricultural productivity within the One Health perspective, with the aim of ensuring that composting simultaneously protects public health, maintains ecosystem quality, and supports sustainable agricultural production.

10. Conclusions

The excessive use of agrochemical products has raised concerns related to their effects on environmental and human health. Furthermore, mismanaged organic wastes facilitate the spread of zoonotic and human pathogens. Composting provides a sustainable solution by converting organic wastes into a safe product with high agronomic potential. This review demonstrated clearly the role of the composting process in the suppression of human pathogens and production of hygienic and safe end-products (compost). Its application has been demonstrated to significantly improve soil fertility and health as well as crop productivity. Concomitantly, this leads to optimized crop yield and productivity and represents a viable strategy for reducing complete dependency on synthetic agrochemical inputs. The “One Health” approach, which emphasizes the interconnected health of humans, animals, and the environment, indicates the relevance of composting and compost as sustainable agronomic solutions to mitigate the human health risks associated with pesticides, fertilizers, and mismanaged manure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.-Z.; Methodology, M.O.-Z., S.E.K., R.B. and S.E.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.O.-Z.; Writing—Review and editing, M.O.-Z., S.E.K., S.E. and R.B.; Supervision, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were created or analyzed in this review article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duhamel, M.; Vandenkoornhuyse, P. Sustainable Agriculture: Possible Trajectories from Mutualistic Symbiosis and Plant Neodomestication. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. World Fertilizer Trends and Outlook to 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-92-5-131894-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tagkas, C.F.; Rizos, E.C.; Markozannes, G.; Karalexi, M.A.; Wairegi, L.; Ntzani, E.E. Fertilizers and Human Health—A Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Evidence. Toxics 2024, 12, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, E.E.; Said Abasse, K.; Côté, A.; Mohamed, K.S.; Baig, M.M.F.A.; Habib, M.; Abbas, M. Drinking-Water Nitrate and Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2022, 77, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Fazio, F.; Habib, S.S.; Nawaz, G.; Attaullah, S.; Ullah, M.; Ahmed, I. Incidence of Heavy Metals in the Application of Fertilizers to Crops (Wheat and Rice), a Fish (Common carp) Pond and a Human Health Risk Assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Kabir, E.; Jahan, S.A. Exposure to Pesticides and the Associated Human Health Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, U.; Malik, M.F.; Javed, A. Pesticide Exposure and Human Health: A Review. J. Ecosyst. Ecography 2016, S5, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Polley, S.; Biswas, S.; Kesh, S.S.; Maity, A.; Batabyal, S. The Link Between Animal Manure and Zoonotic Disease. In Animal Manure; Mahajan, S., Varma, A., Eds.; Soil Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 64, pp. 297–333. ISBN 978-3-030-97290-5. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.K.; Yaseen, T.; Traversa, A.; Kheder, M.B.; Brunetti, G.; Cocozza, C. Effects of the Main Extraction Parameters on Chemical and Microbial Characteristics of Compost Tea. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Verma, J.P. Does Plant—Microbe Interaction Confer Stress Tolerance in Plants: A Review? Microbiol. Res. 2018, 207, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogger, C.G. Potential Compost Benefits for Restoration of Soils Disturbed by Urban Development. Compos. Sci. Util. 2005, 13, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donn, S.; Wheatley, R.E.; McKenzie, B.M.; Loades, K.W.; Hallett, P.D. Improved Soil Fertility from Compost Amendment Increases Root Growth and Reinforcement of Surface Soil on Slopes. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 71, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou-Zine, M.; Symanczik, S.; Rachidi, F.; Fagroud, M.; Aziz, L.; Abidar, A.; Mäder, P.; Achbani, E.H.; Haggoud, A.; Abdellaoui, M.; et al. Effect of Organic Amendment on Soil Fertility, Mineral Nutrition, and Yield of Majhoul Date Palm Cultivar in Drâa-Tafilalet Region, Morocco. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, G.; Bass, A.M.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Benefits of Biochar, Compost and Biochar-Compost for Soil Quality, Maize Yield and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in a Tropical Agricultural Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 543, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aşkin, T.; Aygün, S. Does Hazelnut Husk Compost (HHC) Effect on Soil Water Holding Capacity (WHC)? An Environmental Approach. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2018, 7, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.Z.; Yassine, B.; El Hassan, A.; Abdellatif, H.; Rachid, B. Evaluation of Compost Quality and Bioprotection Potential against Fusarium Wilt of Date Palm. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou-Zine, M.; El Hilali, R.; Haggoud, A.; Achbani, E.H.; Bouamri, R. Effects and Relationships of Compost Dose and Organic Additives on Compost Tea Properties, Efficacy Against Fusarium oxysporum and Potential Effect on Endomycorrhization and Growth of Zea mays L. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 4431–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalwe, H.M.; Lungu, O.I.; Mweetwa, A.M.; Phiri, E.; Njoroge, S.M.C.; Brandenburg, R.L.; Jordan, D.L. Effects of Compost Manure on Soil Microbial Respiration, Plant-Available-Water, Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Yield and Pre-Harvest Aflatoxin Contamination. Peanut Sci. 2019, 46, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, H.A.; Kassem, H.A. Improving Fruit Quality, Nutritional Value and Yield of Zaghloul Dates by the Application of Organic and/or Mineral Fertilizers. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 127, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hose, T.; Cougnon, M.; Vliegher, A.; Vandecasteele, B.; Viaene, N.; Cornelis, W. The Positive Relationship between Soil Quality and Crop Production: A Case Study on the Effect of Farm Compost Application. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2014, 75, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barje, F.; Meddich, A.; El Hajjouji, H.; El Asli, A.; Ait Baddi, G.; El Faiz, A.; Hafidi, M. Growth of Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) in Composts of Olive Oil Mill Waste with Organic Household Refuse. Compos. Sci. Util. 2016, 24, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, G.; Ewusi-Mensah, N.; Nouri, M.; Tetteh, F.M.; Safo, E.Y.; Abaidoo, R.C. Nutrient Release Patterns of Compost and Its Implication on Crop Yield under Sahelian Conditions of Niger. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2016, 105, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Razzak, H.; Alkoaik, F.; Rashwan, M.; Fulleros, R.; Ibrahim, M. Tomato Waste Compost as an Alternative Substrate to Peat Moss for the Production of Vegetable Seedlings. J. Plant Nutr. 2019, 42, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Searchinger, T.D.; Dumas, P.; Shen, Y. Managing Nitrogen for Sustainable Development. Nature 2015, 528, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raun, W.R.; Johnson, G.V. Improving Nitrogen Use Efficiency for Cereal Production. Agron. J. 1999, 91, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syers, J.K.; Johnston, A.E.; Curtin, D. Efficiency of Soil and Fertilizer Phosphorus Use: Reconciling Changing Concepts of Soil Phosphorus Behaviour with Agronomic Information; FAO Fertilizer and Plant Nutrition Bulletin; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008; ISBN 978-92-5-105929-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, D. Amounts of Pesticides Reaching Target Pests: Environmental Impacts and Ethics. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 1995, 8, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.E.; Meade, B.J. Potential Health Effects Associated with Dermal Exposure to Occupational Chemicals. Environ. Health Insights 2014, 8s1, EHI.S15258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, M.S.; Venkatraman, S.K.; Vijayakumar, N.; Kanimozhi, V.; Arbaaz, S.M.; Stacey, R.S.; Swamiappan, S. Bioaccumulation of Lead (Pb) and Its Effects on Human: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasleem, S.; Masud, S.; Habib, S.S.; Naz, S.; Fazio, F.; Aslam, M.; Attaullah, S. Investigation of the Incidence of Heavy Metals Contamination in Commonly Used Fertilizers Applied to Vegetables, Fish Ponds, and Human Health Risk Assessments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 100646–100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, P. A Human Model of Gastric Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 3554–3560. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Achal, V. A Comprehensive Review on Environmental and Human Health Impacts of Chemical Pesticide Usage. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, K.K.; Ibrahim, M.H.; Quaik, S.; Ismail, S.A. Introduction to Organic Wastes and Its Management. In Prospects of Organic Waste Management and the Significance of Earthworms; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-3-319-24706-9. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Z.; Balta, I.; Black, L.; Naughton, P.J.; Dooley, J.S.G.; Corcionivoschi, N. The Fate of Foodborne Pathogens in Manure Treated Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 781357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, T.; Jeurissen, L.; Hackert, V.; Hoebe, C. Land-Applied Goat Manure as a Source of Human Q-Fever in the Netherlands, 2006–2010. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hembach, N.; Bierbaum, G.; Schreiber, C.; Schwartz, T. Facultative Pathogenic Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Swine Livestock Manure and Clinical Wastewater: A Molecular Biology Comparison. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atidégla, S.C.; Huat, J.; Agbossou, E.K.; Saint-Macary, H.; Glèlè Kakai, R. Vegetable Contamination by the Fecal Bacteria of Poultry Manure: Case Study of Gardening Sites in Southern Benin. Int. J. Food Sci. 2016, 2016, 4767453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Lian, Y.; Lin, D.; Huang, D.; Yao, Y.; Ju, F.; Wang, M. Insights into Microbial Contamination in Multi-Type Manure-Amended Soils: The Profile of Human Bacterial Pathogens, Virulence Factor Genes and Antibiotic Resistance Genes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 437, 129356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, S.; Krishnasamy, V.; Saw, L.; Smith, L.; Wagner, J.; Weigand, J.; Tewell, M.; Kellis, M.; Penev, R.; McCullough, L.; et al. Outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 Infections Associated with Exposure to Animal Manure in a Rural Community—Arizona and Utah, June–July 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferronato, N.; Torretta, V. Waste Mismanagement in Developing Countries: A Review of Global Issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torretta, V.; Ferronato, N.; Katsoyiannis, I.; Tolkou, A.; Airoldi, M. Novel and Conventional Technologies for Landfill Leachates Treatment: A Review. Sustainability 2016, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karak, T.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Das, T.; Paul, R.K.; Bezbaruah, R. Non-Segregated Municipal Solid Waste in an Open Dumping Ground: A Potential Contaminant in Relation to Environmental Health. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 10, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, K.; Soudi, B.; Boukhari, S.; Perissol, C.; Roussos, S.; Alami, I.T. Composting Parameters and Compost Quality: A Literature Review. Org. Agric. 2018, 8, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, M.; Persiani, A.; Palese, A.M.; Meo, V.; Pastore, V.; D’Adamo, C.; Celano, G. Composting: The Way for a Sustainable Agriculture. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 123, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucconi, F.; Bertoldi, M. Compost Specifications for the Production and Characterization of Compost from Municipal Solid Waste. In Compost: Production, Quality and Use; De Bertoldi, M., Ferranti, M.P., L′Hermite, M.P., Zucconi, F., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 1987; pp. 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, E.D.; Millner, P.D.; Wells, J.E.; Kalchayanand, N.; Guerini, M.N. Fate of Naturally Occurring Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Other Zoonotic Pathogens during Minimally Managed Bovine Feedlot Manure Composting Processes. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1308–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, M.L.; Walters, L.D.; Avery, S.M.; Moore, A. Decline of Zoonotic Agents in Livestock Waste and Bedding Heaps. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadra, A.; Ezzariai, A.; Kouisni, L.; Hafidi, M. Helminth Eggs Inactivation Efficiency by Sludge Co-Composting under Arid Climates. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 31, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M.; Muoghalu, C.C.; Acheng, P.O. Inactivation of Faecal Pathogens during Faecal Sludge Composting: A Systematic Review. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2023, 12, 150–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepesteur, M. Human and Livestock Pathogens and Their Control during Composting. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 1639–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Reuter, T.; Inglis, G.D.; Larney, F.J.; Alexander, T.W.; Guan, J.; McAllister, T.A. A Biosecure Composting System for Disposal of Cattle Carcasses and Manure Following Infectious Disease Outbreak. J. Environ. Qual. 2009, 38, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, C.; Blanchart, E.; Bernoux, M.; Lal, R.; Manlay, R. Soil Fertility Concepts over the Past Two Centuries: The Importance Attributed to Soil Organic Matter in Developed and Developing Countries. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2012, 58, S3–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adugna, G. A Review on Impact of Compost on Soil Properties, Water Use and Crop Productivity. Acad. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 2016, 4, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chehab, H.; Tekaya, M.; Ouhibi, M.; Gouiaa, M.; Zakhama, H.; Mahjoub, Z.; Mechri, B. Effects of Compost, Olive Mill Wastewater and Legume Cover Crops on Soil Characteristics, Tree Performance and Oil Quality of Olive Trees Cv. Chemlali grown under organic farming system. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 253, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Lee, C.H.; Jung, K.Y.; Do Park, K.; Lee, D.; Kim, P.J. Changes of Soil Organic Carbon and Its Fractions in Relation to Soil Physical Properties in a Long-Term Fertilized Paddy. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 104, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, M.P.; Bommarco, R.; Kleijn, D.; Martin, E.; Mortimer, S.R.; Redlich, S. Enhancing Soil Organic Matter as a Route to the Ecological Intensification of European Arable Systems. Ecosystems 2018, 21, 1404–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouajila, K.; Sanaa, M. Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Physico-Chemical and Biological Properties. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2011, 2, 485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Yan, Y.; Cao, J.; Christie, P.; Zhang, F.; Fan, M. Effects of Combined Application of Organic Amendments and Fertilizers on Crop Yield and Soil Organic Matter: An Integrated Analysis of Long-Term Experiments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 225, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roghanian, S.; Hosseini, H.M.; Savaghebi, G.; Halajian, L.; Jamei, M.; Etesami, H. Effects of Composted Municipal Waste and Its Leachate on Some Soil Chemical Properties and Corn Plant Responses. Int. J. Agric. Res. Rev. 2012, 2, 801–814. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamedelnour, A.; Taşkin, M.B.; Elamin, E.A. Influence of Composted Mesquite on Growth, Yield, Nutrients Content of Maize (Zea mays L.) and Some Soil Properties in Sudan. Int. J. Agric. Policy Res. 2019, 7, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Argaw, A. Organic and Inorganic Fertilizer Application Enhances the Effect of Bradyrhizobium on Nodulation and Yield of Peanut (Arachis hypogea L.) in Nutrient Depleted and Sandy Soils of Ethiopia. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2017, 6, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, M.K.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Impact of Manure and Fertilizers on Chemical Fractions of Zn and Cu in Soil under Rice-Wheat Cropping System. J. Indian Soc. Soil Sci. 2019, 67, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Hernández, A.; Roig, A.; Serramiá, N.; Civantos, C.G.O.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. Application of Compost of Two-Phase Olive Mill Waste on Olive Grove: Effects on Soil, Olive Fruit and Olive Oil Quality. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, R.S.; Hussain, F.; Abbas, I.; Umair, M.; Sun, Y. Effect of Compost and Chemical Fertilizer Application on Soil Physical Properties and Productivity of Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2020, 13, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, C.N.; McLaughlin, R.A.; Johnson, A.; Miller, G.; Heitman, J.L. The Effects of Compost Incorporation on Soil Physical Properties in Urban Soils—A Concise Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadshirazi, F.; Brown, V.K.; Heitman, J.L.; McLaughlin, R.A. Effects of Tillage and Compost Amendment on Infiltration in Compacted Soils. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2016, 71, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadshirazi, F.; McLaughlin, R.A.; Heitman, J.L.; Brown, V.K. A Multi-Year Study of Tillage and Amendment Effects on Compacted Soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, M.S.; Bassuk, N.; Es, H.; Rakow, D. Long-Term Remediation of Compacted Urban Soils by Physical Fracturing and Incorporation of Compost. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 24, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P.D.; May, P.B.; Livesley, S.J. Effects of Deep Tillage and Municipal Green Waste Compost Amendments on Soil Properties and Tree Growth in Compacted Urban Soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 227, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittarelli, F.; Petruzzelli, G.; Pezzarossa, B.; Civilini, M.; Benedetti, A.; Sequi, P. Quality and Agronomic Use of Compost. In Waste Management Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 8, pp. 119–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sayara, T.; Basheer-Salimia, R.; Hawamde, F.; Sánchez, A. Recycling of Organic Wastes through Composting: Process Performance and Compost Application in Agriculture. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P.D.; Farrell, C.; May, P.B.; Livesley, S.J. Biochar and Compost Equally Improve Urban Soil Physical and Biological Properties and Tree Growth, with No Added Benefit in Combination. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Cotton, M. Changes in Soil Properties and Carbon Content Following Compost Application: Results of on-Farm Sampling. Compos. Sci. Util. 2011, 19, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, N.; Guo, L.; Meng, J.; Ding, N. Effects of Manure Compost Application on Soil Microbial Community Diversity and Soil Microenvironments in a Temperate Cropland in China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 108555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, A.G.; Vingiani, S.; Palladino, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; Duri, L.G.; Pannico, A.; Rouphael, Y.; Pascale, S.; Adamo, P. Geo-Mineralogical Characterisation of Mars Simulant MMS-1 and Appraisal of Substrate Physico-Chemical Properties and Crop Performance Obtained with Variable Green Compost Amendment Rates. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović, V.; Ugrenović, V.; Popović, V.; Dimitrijević, S.; Popović, S.; Aćimović, M.; Pezo, L. Productivity and Flower Quality of Different Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) Varieties on the Compost Produced from Medicinal Plant Waste. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddich, A.; Oufdou, K.; Boutasknit, A.; Raklami, A.; Tahiri, A.; Ben-Laouane, R.; Baslam, M. Use of Organic and Biological Fertilizers as Strategies to Improve Crop Biomass, Yields and Physicochemical Parameters of Soil. In Nutrient Dynamics for Sustainable Crop Production; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 247–288. [Google Scholar]

- Benabderrahim, M.A.; Elfalleh, W.; Belayadi, H.; Haddad, M. Effect of Date Palm Waste Compost on Forage Alfalfa Growth, Yield, Seed Yield and Minerals Uptake. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2018, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, A.G.; Paradiso, R.; Liuzzi, G. Green Compost Amendment Improves Potato Plant Performance on Mars Regolith Simulant as Substrate for Cultivation in Space. Plant Soil 2023, 486, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, M.A.; Al-Yasi, H.M.; Ghoneim, A.M. Nitrogen and Compost Enhanced the Phytoextraction Potential of Cd and Pb from Contaminated Soils by Quail Bush [Atriplex lentiformis (Torr.) S.Wats]. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anli, M.; Baslam, M.; Tahiri, A.; Raklami, A.; Symanczik, S.; Boutasknit, A.; Meddich, A. Biofertilizers as Strategies to Improve Photosynthetic Apparatus, Growth, and Drought Stress Tolerance in the Date Palm. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 516818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kinany, S.; Achbani, E.; Faggroud, M.; Ouahmane, L.; El Hilali, R.; Haggoud, A.; Bouamri, R. Effect of Organic Fertilizer and Commercial Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on the Growth of Micropropagated Date Palm Cv. Feggouss. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Hui, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. Effects of Different Fertilization and Fallowing Practices on Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralization in a Dryland Soil with Low Organic Matter. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2019, 19, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Crohn, D.M. Effect of Composted Greenwaste and Rockwool on Plant Growth of Okra, Tomato, and Chili Peppers. Compos. Sci. Util. 2018, 26, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoitink, H.A.J.; Schmitthenner, A.F.; Herr, L.J. Composted Bark for Control of Root Rot in Ornamentals. J. Arboric. 1975, 1, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corato, U. Disease-suppressive compost enhances natural soil suppressiveness against soil-borne plant pathogens: A critical review. Rhizosphere 2020, 13, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, C.M.; Palni, U.; Franke-Whittle, I.H.; Sharma, A.K. Compost: Its Role, Mechanism and Impact on Reducing Soil-Borne Plant Diseases. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogev, A.; Raviv, M.; Hadar, Y.; Cohen, R.; Katan, J. Plant Waste-Based Composts Suppressive to Diseases Caused by Pathogenic Fusarium Oxysporum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2006, 116, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, R.; Coventry, E. Suppression of Soil-Borne Plant Diseases with Composts: A Review. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2005, 15, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinković, M.; Lalević, B.; Jovičić-Petrović, J.; Golubović-Ćurguz, V.; Kljujev, I.; Raičević, V. Biopotential of Compost and Compost Products Derived from Horticultural Waste—Effect on Plant Growth and Plant Pathogens’ Suppression. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 121, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoitink, H.A.J.; Changa, C.M. Managing soil-borne pathogens. Acta Hortic. 2004, 635, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diánez, F.; Santos, M.; Tello, J.C. Suppression of Soilborne Pathogens by Compost: Suppressive Effects of Grape Marc Compost on Phytopathogenic Oomycetes. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Soilless Culture and Hydroponics 697, Almería, Spain, 14–19 November 2004; pp. 441–460. [Google Scholar]

- You, M.P.; Sivasithamparam, K. Changes in Microbial Populations of an Avocado Plantation Mulch Suppressive of Phytophthora cinnamomi. Appl. Soil Ecol. 1995, 2, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyselková, M.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Pseudomonas and Other Microbes in Disease-Suppressive Soils. Org. Fertil. Soil Qual. Hum. Health-Sustain. Agric. Rev. 2012, 9, 93–140. [Google Scholar]

- San Fulgencio, N.S.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; López, M.J.; Jurado, M.M.; López-González, J.A.; Moreno, J. Biotic Aspects Involved in the Control of Damping-off Producing Agents: The Role of the Thermotolerant Microbiota Isolated from Composting of Plant Waste. Biol. Control 2018, 124, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Pessarakli, M. A Review on Biological Control of Fungal Plant Pathogens Using Microbial Antagonists. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 10, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, K.K.; Gardener, B.M. Biological Control of Plant Pathogens. Plant Health Instr. 2006, 2, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dick, W.A.; Hoitink, H.A.J. Compost-Induced Systemic Acquired Resistance in Cucumber to Pythium Root Rot and Anthracnose. Phytopathology 1996, 86, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramisharif, A.; Rose, L.E. Efficacy of Biological Agents and Compost on Growth and Resistance of Tomatoes to Late Blight. Planta 2019, 249, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avilés, M.; Borrero, C.; Trillas, M.I. Review on Compost as an Inducer of Disease Suppression in Plants Grown in Soilless Culture. Dyn. Soil Dyn. Plant 2011, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, C.; Spaccini, R.; Piccolo, A.; Scala, F.; Bonanomi, G. Compost Amendments Enhance Peat Suppressiveness to Pythium ultimum, Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotinia minor. Biol. Control 2011, 56, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Y.; Meon, S.; Ismail, M.R.; Ali, A. Trichoderma-Fortified Compost Extracts for the Control of Choanephora Wet Rot in Okra Production. Crop Prot. 2008, 27, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatafora, C.; Tringali, C. Valorization of Vegetable Waste: Identification of Bioactive Compounds and Their Chemo-Enzymatic Optimization. Open Agric. J. 2012, 6, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California Compost Quality Council. Compost Maturity Index; California Compost Quality Council: Nevada City, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lasaridi, K.; Protopapa, I.; Kotsou, M.; Pilidis, G.; Manios, T.; Kyriacou, A. Quality Assessment of Composts in the Greek Market: The Need for Standards and Quality Assurance. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 80, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffella, P.J.; Kahn, B.A. (Eds.) Compost Utilization in Horticultural Cropping Systems; Jewil Publishers: Nanning, China; CRC Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Larbi, M. Influence de la Qualité des Composts et de Leurs Extraits sur la Protection des Plantes Contre les Maladies Fongiques. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wichuk, K.M.; McCartney, D. Compost Stability and Maturity Evaluation—A Literature Review. J. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2013, 8, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, Y.; Inoko, A. The Measurement of the Cation-Exchange Capacity of Composts for the Estimation of the Degree of Maturity. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1980, 26, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.J.; Kim, K.Y.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, C.N.; Umeda, M. Evaluation of Maturity Parameters and Heavy Metal Contents in Composts Made from Animal Manure. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golueke, G.C. Principles of Biological Resource Recovery. BioCycle 1981, 22, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, M.P.; Sommer, S.G.; Chadwick, D.; Qing, C.; Guoxue, L.; Michel, F.C. Current Approaches and Future Trends in Compost Quality Criteria for Agronomic, Environmental, and Human Health Benefits. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 144, pp. 143–233. ISBN 978-0-12-812419-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kapanen, A.; Itävaara, M. Ecotoxicity Tests for Compost Applications. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2001, 49, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, M.T.; Paradelo, R. A Review on the Use of Phytotoxicity as a Compost Quality Indicator. Dyn. Soil Dyn. Plant 2011, 5, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zucconi, F.; Forte, M.; Monaco, A.; Bertoldi, M. Biological Evaluation of Compost Maturity. BioCycle 1981, 22, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Martin, M. A Review of the Literature on the Occurrence and Survival of Pathogens of Animals and Humans in Green Compost; WRAP Standard Report; Waste Resources Action Programme: Newbury, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Vicente, A.; Ros, M.; Tittarelli, F.; Intrigliolo, F.; Pascual, J.A. Citrus Compost and Its Water Extract for Cultivation of Melon Plants in Greenhouse Nurseries. Evaluation of nutriactive and biocontrol effects. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 8722–8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, M.; Awasthi, M.K.; Chen, H.; Awasthi, S.K.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Measurement of Cow Manure Compost Toxicity and Maturity Based on Weed Seed Germination. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, A.C.; Green, J.M.; Lennartsson, M. The Effect of Temperature on the Viability of Weed Seeds in Compost. Compos. Sci. Util. 1998, 6, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eudoxie, G.; Martin, M. Compost Tea Quality and Fertility. In Organic Fertilizers-History, Production and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, E. The Compost Tea Brewing Manual; Soil Food Web Incorporated: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kannangara, T.; Forge, T.; Dang, B. Effects of Aeration, Molasses, Kelp, Compost Type, and Carrot Juice on the Growth of Escherichia Coli in Compost Teas. Compos. Sci. Util. 2006, 14, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, K.; Shrestha, P.; Walsh, K.B.; Harrower, K.M.; Midmore, D.J. Microbial Enhancement of Compost Extracts Based on Cattle Rumen Content Compost–Characterisation of a System. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 8027–8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, Y.; Meon, S.; Kadir, J.; Siddiqui, Y. Microbial Starter for the Enhancement of Biological Activity of Compost Tea. Int. J. Agric. Biol 2010, 12, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, A.P.; Radovich, T.J.; Hue, N.V.; Talcott, S.T.; Krenek, K.A. Vermicompost Extracts Influence Growth, Mineral Nutrients, Phytonutrients and Antioxidant Activity in Pak Choi (Brassica rapa Cv. Bonsai, Chinensis Group) Grown under Vermicompost and Chemical Fertiliser. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 2383–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, T.; Gil, M.V.; Calvo, L.F.; Morán, A. The Influence of Aeration System, Temperature and Compost Origin on the Phytotoxicity of Compost Tea. Compos. Sci. Util. 2009, 17, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuerell, S.J.; Mahaffee, W.F. Compost Tea as a Container Medium Drench for Suppressing Seedling Damping-off Caused by Pythium ultimum. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weltzien, H.C. The Use of Composted Materials for Leaf Disease Suppression in Field Crops. In Monograph—British Crop Protection Council; British Crop Protection Council: London, UK, 1990; pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Zhao, S.; Xiong, Y.; Peng, C.; Xu, X.; Si, G. Biological, Physicochemical, and Spectral Properties of Aerated Compost Extracts: Influence of Aeration Quantity. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2015, 46, 2295–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Han, D.Y.; Dick, W.A.; Davis, K.R.; Hoitink, H.A.J. Compost and Compost Water Extract-Induced Systemic Acquired Resistance in Cucumber and Arabidopsis. Phytopathology 1998, 88, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuerell, S.; Mahaffee, W.F. Compost Tea: Principles and Prospects for Plant Disease Control. Compos. Sci. Util. 2002, 10, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, S.A. Physiological Action of Humic Substances on Microbial Cells. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1985, 17, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.P.; Radovich, T.J.; Hue, N.V.; Paull, R.E. Biochemical Properties of Compost Tea Associated with Compost Quality and Effects on Pak Choi Growth. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 148, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]