Abstract

For patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) follicular lymphoma (FL) after ≥2 prior lines of therapy, T-cell-redirecting therapies—including the bispecific CD3xCD20 antibody (BsAbs) mosunetuzumab (mosu) and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies such as axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel), lisocabtagen maraleucel (liso-cel), and tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel)—are approved by the FDA and EMA. Treatment selection should consider patient-related factors, prior therapeutic exposure, and toxicity profiles. We describe the 20-year history of a patient with R/R FL. At the fourth relapse, both BsAbs and CAR-T cells were available; however, due to the cumulative toxic burden and the high risk of cytopenias, mosu was selected as the preferred option. During mosu, the patient developed pure red cell aplasia unrelated to infections. Despite achieving a partial response after eight cycles of mosu, this complication led to the decision to proceed with allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). The course was ultimately complicated by severe early toxicity with massive hemoptysis, acute respiratory failure, and hemorrhagic alveolitis, resulting in a fatal outcome. This case illustrates the delicate balance required in selecting between BsAbs and CAR-T therapy in R/R FL. Contributing factors to the patient’s fragility included profound immune status, transfusion-dependent red cell aplasia, prior cumulative chemotherapy, and pulmonary toxicity associated with conditioning regimens. The case underscores the importance of individualized treatment strategies and suggests that earlier integration of novel T-cell-redirecting therapies may mitigate cumulative toxicity and infection risk. Individualized therapeutic planning is critical in heavily pretreated R/R FL. In select cases, bridging strategies using BsAbs can provide disease control and facilitate transplantation. Still, careful assessment of patient fitness, marrow reserve, and cumulative toxicity is essential to minimize the risk of fatal complications.

1. Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the second most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for approximately 20–25% of cases [1,2]. Despite generally favorable long-term survival, the disease is characterized by a relapsing course, and most patients eventually require multiple lines of therapy. Relapse becomes progressively more challenging to manage, and outcomes worsen in heavily pretreated patients.

Over the past decade, novel immunotherapies have revolutionized the therapeutic landscape of relapsed/refractory (R/R) FL. In particular, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) targeting CD3xCD20, such as mosunetuzumab (mosu), have demonstrated significant efficacy in this setting from the third line onward [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. These two forms of T-cell-engaging therapy exhibit distinct mechanisms of action. CAR-T therapy involves engineering the patient’s T cells to express a chimeric receptor directed against the CD19 antigen. In contrast, BsAbs simultaneously bind CD3 on T cells and CD20 on B cells, redirecting T-cell cytotoxicity toward malignant B cells without the need for ex vivo cell modification. The differing targets (CD19 for CAR-T vs. CD20 for mosu) may influence efficacy, toxicity profiles, and treatment outcomes, underscoring the need to consider antigen-specific biology when selecting therapy [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Nowadays, these therapies can also be employed as a bridge to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) [10,11]. In real-world practice, management of heavily pretreated, multiply relapsed FL patients often precedes the availability of these novel therapies. Treatment decisions must be individualized, taking into account patient-related factors (age, performance status, comorbidities), prior treatment burden (including disease- and infection-related complications), and the feasibility of allo-HSCT in younger, fit patients. The choice between CAR-T and BsAbs should integrate these considerations while also acknowledging differences in target antigens and mechanisms of action, highlighting the importance of direct comparative studies in the future.

2. Case Report

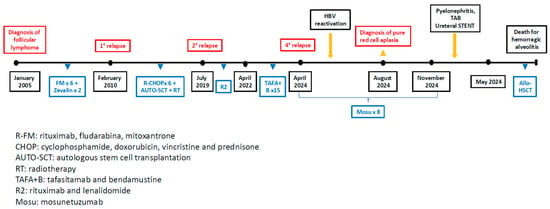

In January 2005, a 41-year-old man was diagnosed with grade 3A stage IV FL with abdominal and bone marrow involvement (Figure 1). Lamivudine prophylaxis was started because the patient had a history of prior HBV infection. He received six cycles of novantrone, fludarabine, and rituximab, followed by two cycles of zevalin, achieving complete remission (CR) documented by computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET). In February 2010, the patient experienced a relapse with lymphadenopathy in the laterocervical and paraesophageal regions. The biopsy showed the progression to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). At this time, he was treated with six cycles of rituximab–cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP regimen), followed by autologous stem cell transplantation. At the end of treatment, the residual abdominal mass was irradiated with 30 Gy (CT-PET negative). In July 2019, the patient experienced a second relapse of the previous FL, which was treated with bendamustine and anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody tafasitamab, as part of a clinical trial, achieving CR. The patient received this treatment for 15 cycles until April 2022, when a third relapse of FL was documented (CT positive). A fourth-line therapy with rituximab and lenalidomide was initiated and continued until November 2023, when disease progression of FL was documented with an abdominal mass by CT. In this period, the patient exhibited a significant HBV reactivation, which required treatment with entecavir, leading to a subsequent reduction in viral load. At that time, both CAR-T therapy and mosu were available. The case was discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting, and the patient was considered eligible to mosu as a bridge to allo-HSCT, considering the previous exposure to multiple cycles of chemotherapy and radiation. From April 2024 to November 2024, the patient received a total of eight cycles of mosu, achieving a partial response according to the Lugano 2014 criteria (the CT-scan documented a 50% reduction in abdominal mass). Mosu was administered in 21-day cycles based on the standard schedule (cycle 1: step-up dosing schedule; cycle 2: day 1, 60 mg; from cycle 3 onward, the dose was 30 mg on day 1). In August, due to persistent anemia, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, revealing red cell aplasia likely related to the previous chemotherapy burden, given the exclusion of a virological etiology and the absence of reported cases mosu-related. At this time, the patient became transfusion-dependent, and iron chelation therapy was started. Considering the patient’s age, good performance status, cumulative treatment burden, immunosuppression, and the onset of pure red cell aplasia, the patient was considered eligible for allo-HSCT, and a search for a matched unrelated donor (MUD) was activated, as the patient’s sister was haploidentical [10]. In the subsequent months, the patient developed nephrolithiasis-associated pyelonephritis, which required multiple hospital admissions for fever and antibiotic therapy. Furthermore, in March, the patient underwent placement of a ureteral stent. In April, the stent was removed following spontaneous stone passage, allowing resumption of the transplant workup. In May 2025, the patient underwent allo-HSCT from an 8/8 HLA-matched unrelated male donor. At the time of transplantation, the patient had no organ-specific comorbidities and no active infections, as HBV-DNA was undetectable. The HCT-CI score was 0, as was the ECOG performance status. The PET pre-allo-HSCT revealed a Deauville score of 3. The reduced-intensity TBF (thiotepa 5 mg/kg day 1 and 2, busulfan 6.4 mg/kg ev day 3, 4, 5, fludarabine 150 mg/m2 day 3, 4, and 5) conditioning regimen was used, and anti-thymocyte globulin (thymoglobulin 2 mg/kg day −3, −2, −1), cyclosporine, and a short-course of methotrexate as GvHD prophylaxis. Unfortunately, the day after the infusion, he experienced episodes of massive, life-threatening hemoptysis and developed acute respiratory failure. Chest radiography demonstrated diffuse bilateral peribronchial and alveolar opacities consistent with hemorrhagic bronchiolitis. He died rapidly despite maximal supportive intensive care measures.

Figure 1.

Patient’s timeline treatment.

3. Discussion

We presented a clinical case in which the therapeutic decision-making was particularly challenging, requiring a balance between disease control and toxicity in a heavily pretreated R/R FL patient. The patient’s immunosuppressed status, further complicated by HBV reactivation and prior treatment exposure, required a therapeutic strategy aimed at minimizing infectious and hematologic risks while maintaining adequate disease control. Furthermore, cumulative toxicity burden raised concerns about secondary myeloid neoplasms and long-term marrow reserve. In this context, allo-HSCT remained a consolidative and potentially curative option.

However, a retrospective and critical analysis of this choice highlights that the patient’s favorable pre-transplant profile (HCT-CI 0, ECOG 0) coexisted with significant adverse factors, including partial metabolic response (Deauville 3), transfusion-dependent aplasia, and five prior treatment lines. When interpreted in light of European Bone Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) registry data reporting a 1-year NRM of approximately 20–30% in R/R FL undergoing allo-HSCT, these elements acquire particular relevance, underscoring that the decision to proceed to transplant was made in a context where baseline transplant-related mortality was already non-negligible [12]. Furthermore, prior thoracic radiotherapy, extensive exposure to alkylating agents, and the use of a busulfan-based conditioning regimen likely compounded the patient’s vulnerability to pulmonary toxicity, contributing to a risk landscape less benign than suggested by comorbidity scores alone. This case, therefore, highlights the importance of integrating quantitative NRM prediction tools—not solely clinical intuition—into pre-transplant assessment to better refine individual risk estimates and support shared decision-making in future scenarios [13]. A more comprehensive analysis of the hemorrhagic alveolitis suggests a multifactorial etiology, consistent with the condition’s low reported incidence (<5%) but high mortality (>80%). Although the negative pre-transplant CT and the normal DLCO—Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Carbon Monoxide—might initially argue against overt baseline lung injury, several converging factors likely created a vulnerable pulmonary environment. Busulfan-related toxicity—administered without area under the curve (AUC) guided exposure monitoring—remains a central contributor, particularly when contextualized within cumulative endothelial damage from prior thoracic radiotherapy and repeated alkylator exposure, including fludarabine. Additional pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative stressors, such as iron overload, together with profound peri-transplant immunosuppression and HBV reactivation, may have further amplified susceptibility to diffuse alveolar injury. This case, therefore, underscores the necessity of structured pre-transplant pulmonary risk stratification—incorporating imaging, functional assessment, and pharmacokinetic monitoring—to better anticipate and mitigate such life-threatening complications in future candidates. When evaluating available immunotherapies, the choice between CAR T-cell therapy and BsAbs was particularly complex. Current guidelines for therapeutic sequencing in R/R FL remain limited, and the absence of head-to-head trials requires clinicians to rely on indirect comparisons and patient-specific considerations [7]. The three approved CD19-directed CAR T-cell products have shown remarkable efficacy, with overall and CR rates exceeding 90% and 75%, respectively, and durable responses. Yet logistical constraints, the need for lymphodepleting chemotherapy, and prolonged cytopenias are non-negligible risks in profoundly immunocompromised patients such as ours [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Conversely, mosu provides high response rates (ORR ≈ 80%; CR ≈ 60–70%) with a more favorable hematologic and infectious toxicity profile [14,15], offering an off-the-shelf option suitable for rapid disease control to maintain transplant eligibility.

4. Conclusions

The therapeutic choice in heavily pretreated R/R FL remains challenging, especially when patients develop bone marrow toxicity, as in our case. Using a BsAbs as a bridge to allo-HSCT can be a viable strategy when multiple prior lines have progressively limited therapeutic options. Ideally, the decision between BsAbs and CAR-T should occur earlier in the disease course to preserve marrow reserve, reduce toxicity, and prevent further immunosuppression. Ongoing trials such as CELESTIAL (NCT04245839), evaluating CAR-T therapy, and LOTIS-7 (NCT04680052), exploring loncastuximab tesirine in combination with bispecific antibodies, are expected to clarify critical issues regarding early-line application, including efficacy, tolerability, and the optimal integration of combination strategies within these emerging therapeutic platforms.

Author Contributions

M.C. (Martina Canichella) conceived and wrote the paper; M.M.T., M.C. (Mariagiovanna Cefalo), A.D.R., C.M., and L.C. revised some sections of the paper; A.C. revised the bibliography; R.C., P.d.F., and E.A. revised and approved the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require authorization from an ethics committee for this case report, as all treatments and drugs administered were approved by the competent regulatory authorities and used according to standard clinical practice.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carbone, A.; Roulland, S.; Gloghini, A.; Younes, A.; von Keudell, G.; López-Guillermo, A.; Fitzgibbon, J. Follicular lymphoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinzani, P.L.; Muñoz, J.; Trotman, J. Current and future therapies for follicular lymphoma. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Chavez, J.C.; Sehgal, A.R.; Epperla, N.; Ulrickson, M.; Bachy, E.; Munshi, P.N.; Casulo, C.; Maloney, D.G.; de Vos, S.; et al. Three-year follow-up analysis of axicabtagene ciloleucel in relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (ZUMA-5). Blood 2024, 143, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dreyling, M.; Fowler, N.H.; Dickinson, M.; Martinez-Lopez, J.; Kolstad, A.; Butler, J.; Ghosh, M.; Popplewell, L.; Chavez, J.C.; Bachy, E.; et al. Durable response after tisagenlecleucel in adults with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma: ELARA trial update. Blood 2024, 143, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morschhauser, F.; Dahiya, S.; Palomba, M.L.; Martin Garcia-Sancho, A.; Reguera Ortega, J.L.; Kuruvilla, J.; Jäger, U.; Cartron, G.; Izutsu, K.; Dreyling, M.; et al. Lisocabtagene Maraleucel in Follicular Lymphoma: The Phase 2 TRANSCEND FL Study. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2199–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budde, L.E.; Assouline, S.; Sehn, L.H.; Schuster, S.J.; Yoon, S.S.; Yoon, D.H.; Matasar, M.J.; Bosch, F.; Kim, W.S.; Nastoupil, L.J.; et al. Single-agent mosunetuzumab shows durable complete responses in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphomas: Phase I dose-escalation study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morabito, F.; Martino, E.A.; Nizzoli, M.E.; Talami, A.; Pozzi, S.; Martino, M.; Neri, A.; Gentile, M. Comparative Analysis of Bispecific Antibodies and CAR T-Cell Therapy in Follicular Lymphoma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2025, 114, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jacobson, C.A.; Chavez, J.C.; Sehgal, A.R.; William, B.M.; Munoz, J.; Salles, G.; Munshi, P.; Casulo, C.; Maloney, D.G.; de Vos, S.; et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel in relapsed or refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (ZUMA-5): A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, N.H.; Dickinson, M.; Dreyling, M.; Martinez-Lopez, J.; Kolstad, A.; Butler, J.; Ghosh, M.; Popplewell, L.; Chavez, J.C.; Bachy, E.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: The phase 2 ELARA trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snowden, J.A.; Sánchez-Ortega, I.; Corbacioglu, S.; Basak, G.W.; Chabannon, C.; de la Camara, R.; Dolstra, H.; Duarte, R.F.; Glass, B.; Greco, R.; et al. Indications for haematopoietic cell transplantation for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: Current practice in Europe, 2022. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2022, 57, 1217–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barone, A.; De Philippis, C.; Stella, F.; Dodero, A.; Sarina, B.; Pennisi, M.; Santoro, A.; Carlo-Stella, C.; Guidetti, A.; Bramanti, S.; et al. Allogeneic transplantation after failure of chimeric antigen receptor-T cells and exposure to bispecific antibodies: Feasibility, safety and survival outcomes. Br. J. Haematol. 2025, 207, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, M.; Montané, C.; Paviglianiti, A.; Hurtado, L.; González, S.; Carro, I.; Maluquer, C.; Domingo-Domenech, E.; Gonzalez-Barca, E.; Sureda, A.; et al. Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after bispecific antibodies in non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2023, 58, 1282–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamaison, C.; Latour, S.; Hélaine, N.; Le Morvan, V.; Saint-Vanne, J.; Mahouche, I.; Monvoisin, C.; Dussert, C.; Andrique, L.; Deleurme, L.; et al. A novel 3D culture model recapitulates primary FL B-cell features and promotes their survival. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 5372–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sehn, L.H.; Bartlett, N.L.; Matasar, M.J.; Schuster, S.J.; Assouline, S.E.; Giri, P.; Kuruvilla, J.; Shadman, M.; Cheah, C.Y.; Dietrich, S.; et al. Long-term 3-year follow-up of mosunetuzumab in relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma after ≥2 prior therapies. Blood 2025, 145, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matasar, M.; Bartlett, N.L.; Shadman, M.; Budde, L.E.; Flinn, I.; Gregory, G.P.; Kim, W.S.; Hess, G.; El-Sharkawi, D.; Diefenbach, C.S.; et al. Mosunetuzumab Safety Profile in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory B-cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Clinical Management Experience from a Pivotal Phase I/II Trial. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024, 24, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).