Abstract

Objective: Health education is critical in imparting health literacy to children and developing community health and wellbeing. The effectiveness of the teaching–learning interaction in health education classes depends on the teacher employing effective teaching methods, facilitating students’ deep understanding, critical thinking, and the development of skills, beliefs and attitudes that will be needed for them to cultivate healthy behaviours throughout their lives. Health education teaching differs from other learning areas as it addresses controversial and sensitive topics in class. Little research has been conducted regarding the preferred teaching methods of health educators and their ability to employ these teaching methods effectively in the classroom. Methods: In this paper, we present findings from a doctoral grounded theory study to explain the preferred teaching methods of teachers as they work with young people in the important learning area of health education. The study was conducted using a Chamazian constructivist grounded theory approach with the data being analysed using an inductive process, beginning with open codes and progressing to high-level categories. Main Results: This study determined that the preferred teaching method of the teachers delivering health education in Western Australia was discussion-based teaching. We examine the literature regarding discussion-based teaching methods, particularly in health education. Our findings evidence that teachers report preferring a discussion-based teaching approach, even though the health curriculum advises a critical inquiry approach and many schools in Australia currently promote an explicit teaching method. Conclusions: Teachers have expressed uncertainty as to how to effectively employ a discussion-based approach in class and have sought further clarification as they lead class discussions. Effective teaching practices need to be interrogated to support teachers, so how do we do this in a way that provides clarity for teachers and ultimately produces the best outcomes for young people?

1. Introduction

Health education involves enabling young people to engage with health information in a way that promotes good health and wellbeing, leading to a healthier population [1]. The teaching and learning interaction in health education classes can be conducted in a way that provides opportunities for students to engage with health information that leads to deep understanding and helps them to think critically. Currently, health education, while also having the ultimate goal of helping young people lead healthy lives, differs from other learning areas as it addresses controversial and sensitive topics in class.

The aim of this study was exploration of the classroom teacher’s lived experiences of curriculum reform in health education in Western Australian schools. The research set out to engage participants by exploring perspectives of their own worldview, personal beliefs, and interaction with curriculum implementation.

The health education curriculum in Western Australia has undergone several reforms over the past 40 years. In the latest version of the Australian Curriculum (AC), health education forms one stream of the Health and Physical Education (HPE) Learning Area. An examination of the teaching method choices of teachers working in Western Australia to implement the latest health education curriculum, the Western Australian adaptation of the Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education (AC:HPE), is presented in this paper. The HPE syllabus includes two strands: Personal, Social and Community Health (referred to in this paper as Health Education) and Movement and Physical Activity (Commonly referred to as Physical Education). The Personal, Social and Community Health strand covers content relating to Personal Identity and Change, Staying Safe, Healthy and Active Communities and Interacting with Others.

Curriculum implementation appears, on the surface, to be simply following the prescribed curriculum; however, it requires teachers to interpret the new curriculum, considering their own perspective, along with that of their school context, and then develop suitable and appropriate teaching and learning programmes. It also asks the teachers to engage with and, at times, adopt a new pedagogical approach, which many find challenging.

The constructivist instructional approach has been embraced by many contemporary educators, including Australian secondary school teachers, as they seek to create more engaging and effective learning environments for their students [2]. This preference of constructivist approaches has replaced the previous popularity of explicit instruction and remains the choice of the teacher as to which method they employ [3].

Rather than explicit or constructivist approaches, the AC:HPE promotes a critical pedagogy that attends to concepts of power, social hierarchies and exclusion [4]. Leading up to the implementation of the AC:HPE, scholars such as McCuaig, Carroll, and Macdonald [5] warned that a shift towards a critical approach had considerable resistance amongst many HPE teachers. This resistance was still evident in 2022, as reported by Cruickshank, Pill, Williams, Nash, Mainsbridge, MacDonald and Elmer [6], who reported a critical pedagogy as challenging and described teachers’ understanding of the AC:HPE curriculum naive in relation to the underlying socio-critical elements.

The critical pedagogy approach was embedded into the AC:HPE curriculum in the form of five innovative propositions that underly the content descriptors. This represented a big change for health teachers in Australia because it shifted the focus from ‘what’ to teach to ‘how’ to teach it [7]. Prior to the development of Australia’s National Curriculum, the HPE curriculum documents were primarily content-based with little or no direction about how to go about teaching the content. The five propositions include a focus on educative purpose (FOEP), strengths-based approach (SBA), critical inquiry (CI), health literacy (HL) and valuing movement (VM) [8].

The five propositions underpinning the new HPE syllabus suggested teachers use a critical inquiry-based approach. This shift away from transmissional pedagogy towards critical inquiry [9] was welcomed by many scholars. Critical pedagogy, as encouraged in the propositions, focused on student learning on the problems, issues, and real-world experiences of the students [10], resulting in an expected increase in motivation to learn and improved learning outcomes [11].

However, health education involves the teaching of controversial and sensitive issues and when teaching such topics, it has been reported that teachers may feel more comfortable with an information transmission approach (teacher-led) rather than a critical inquiry and strengths-based approach [7,12].

Throughout the period of time when the AC:HPE was first being implemented in WA (2016–2020), scholars such as Smith, Philpot, Gerdin, Schenker, Linnér, Larsson, Mordal Moen, and Westlie [13] reported that while teachers should attend to the social justice agenda and concepts such as power in the classroom (as promoted in the AC:HPE curriculum), many of these ideals were beyond the power of the teacher to address in the HPE classroom.

This study explores the teaching methods and approaches used and preferred by health teachers in Western Australia when they delivered health education and reveals their preference for discussion-based pedagogies.

2. Materials and Methods

This study investigated how teachers’ individual perspectives shaped their delivery of the health education curriculum and informed their pedagogical decisions. We employed a three-phase qualitative research design grounded in constructivist grounded theory [14]. Data collection was conducted using a series of semi-structured interviews conducted between May and November 2020.

A criterion sampling strategy was used to recruit participants [15]. Eligibility criteria specified that participants must be currently employed as secondary school teachers in Western Australia and actively teaching the Personal, Social and Community Health (PSCH) curriculum to students in years 7–10 (or a portion of this group). Teachers were drawn from Western Australia’s three schooling sectors: State Government schools (777), Catholic Education schools (159), and Independent schools (132).

An invitation to participate was distributed through teacher email networks (ranging from 500 to 2400 subscribers) and posted on various professional online platforms for educators. Respondents were screened via phone or email to ensure they met the study criteria. Two individuals were excluded because they were not currently teaching PSCH at a secondary school level. All participants signed a consent form prior to taking part in the study, and data were anonymised to protect participants’ identities.

In total, 23 teachers participated in the study, representing diverse school contexts across regions, socioeconomic backgrounds, and education sectors in Western Australia. This included 9 male and 14 female teachers. Each semi-structured interview lasted between 26 and 87 min.

Phase 1 interviews began by asking participants about their implementation processes with the new Australian Curriculum. Grounded theory begins with open questions, so the first question was “What’s your involvement with health education at the moment?”. In the second interview, participants were asked to bring a lesson plan they had recently taught regarding what they perceived to be a controversial topic. Participants were given latitude to discuss themes and ideas that concerned them. The third interview was the final phase in this grounded theory approach so it was a confirmatory interview, where participants were shown quotes from previous interviews (anonymously) and they were asked to comment on these in any way they wanted to.

The analytical process began with open coding, followed by ongoing comparative analysis, memo writing, focused coding, and the creation of visual models. This iterative process supported the identification of key categories and ultimately the development of theory.

Theoretical saturation was achieved through an iterative process of simultaneously collecting and analysing data. For example, in Phase 2 of the study, 17 of the 22 participants had stated that they did not feel they had enough time to teach the curriculum. This indicated a saturation of data and prompted the data collection to move on.

Before commencing the study, ethical approval was obtained from the Higher Education Ethics Committee at Alphacrucis University College.

3. Results

This section will report on a selection of key findings of this study, specifically regarding the use of teaching methods in health education. Results below have been categorised into three key groupings: (1) Preferred Teaching methods; (2) Discussion-based Teaching; and (3) Sharing Behaviours.

3.1. Preferred Teaching Methods

Throughout the interviews, the teachers’ descriptions about how they delivered their lessons were tracked, taking note of the different teaching methods mentioned or described. Discussion-based teaching was the method most commonly mentioned (68.65%), followed by research or inquiry-based learning (12.97%) and then lecture-based or teacher-driven lessons, including the use of PowerPoint presentations (8.38%).

Over half of the teachers interviewed in Phase 1 of this study spoke of preferring discussion-based teaching methods because they believed the discussion was a place where learning was constructed. One participant explained it like this, “I don’t like to give out worksheets and go just write down notes and write down that, right? I rather like, if you’ve got a class that’s willing to share, I think they can learn from each other and hear what other people’s opinions are. It’s okay to have those sorts of thoughts and feelings or to not understand this or to understand that. They learn from one another through talking rather than someone reading something or telling them, like talking at them kind of thing.”

For some teachers, the process of the discussion was important as students need to hear a range of opinions and then start to form their own stance. Teachers expressed that they believed a lesson focused on discussion would result in better learning outcomes, rather than a lesson spent filling in a workbook.

Conversely, lecture-based teaching was seen as especially necessary when teaching lower-ability students by some teachers, who stated unequivocally that they would avoid discussion-based lessons in favour of a lecture-based lesson with their lower-ability classes. “With the lower ability levels, it’s much more explicit, and it’s much more direct instruction.”

3.2. Discussion-Based Teaching

Discussions in health education were described as being all about how to interact with other people respectfully. The aim of the discussion is for students to have an opinion while listening to other peoples’ opinions. This is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught to young people.

Teachers in this study described the elements of a discussion-based lesson, including starting with a safe environment, then leading with a stimulus, a sharing of diverse perspectives, reflection or interrogation of views, and ending by guiding the discussion to lead students to the healthy outcome.

Participants spoke about creating a safe classroom to ensure that students felt comfortable to discuss health topics. This could be done through the establishment of ground rules such as using proper terms and keeping confidentiality.

A total of 12 of the 23 teachers interviewed in Phase 1 of this study agreed that discussion-based lessons often began with a stimulus. The stimulus could be a video clip, something to read, presentation of a real-world example, or posing an open-ended question.

Participants expressed that using class discussion as a teaching method is effective as it allowed students to hear a range of perspectives and then reflect on their own, as expressed by a participant, “They have a chance to kind of reflect on their own values in relation to what we’ve covered that lesson.” Another participant put it like this, “I think for me personally, like I said, with, with being a lot of our discussions, we not only get to hear other people’s opinions in the class, but hopefully get kids thinking about their own as well.”

Three teachers said that, during class discussions, they deliberately tried to present different views by asking different students to share their views, or by presenting several different ways of thinking about a topic. They present a range of resources and a range of opinions.

Teachers explained how they prompted students throughout the discussion to help them reflect and really interrogate their thinking. Teachers would facilitate discussion by asking questions such as “Why do you think that?”, “What’s influenced you to think that way?”, “Where did that thought come from?”, and “How do you feel about this?”.

Teachers described the need to “guide” students towards healthy outcomes throughout the discussion and “have their attitudes and values shift.” The basis for this guidance was towards the teachers’ own attitudes and values toward the topic under focus, i.e., what they believed to be a healthy outcome.

This notion of guidance was contested as some teachers believed they should remain neutral during discussions, while others were clear about the need to guide students towards the healthy outcome throughout the discussion. Some teachers describe their role as the facilitator of classroom discussions by leading with a neutral stance. This neutral stance was designed to allow students to feel safe to state their views without the fear of being ‘wrong’ or not in agreement with the teacher. This was expressed succinctly by a participant who said, “I actively do not put my position across.”

Teachers who were proponents of guidance, as opposed to neutral, explained this guidance as convincing students to “rethink their attitude” about health topics. This guidance was described as needing to be formed from a value base. One participant explained their concern about the lack of guidance if teachers simply presented options and allowed students to choose for themselves, “The biggest issue you’re going to face is this issue of, of values. Because ultimately, as you say, if you, if you don’t have a values base, then you’re teaching the, here’s all your options kid, go, go take your pick. And is that going to produce a better society?”

The notion of the teacher needing to be skilled at facilitating discussion was raised by eight teachers. The teacher’s role was very much described as keeping the conversation on the right track, as explained by one participant, “If they’re getting on the wrong track, then I can be like actually, well then, let’s try and put them back on the right track,” and another, “They’re on the wrong track, saying misinformation, you kind of pull back into ‘Ok I’m gonna lead this for a bit.’” Teachers explained that getting students back on the ‘right track’ involved “a lot of questions” to guide the discussion. Eleven teachers stated that they prepared for discussion-based lessons by developing a set of questions to guide the discussion and to engage the students.

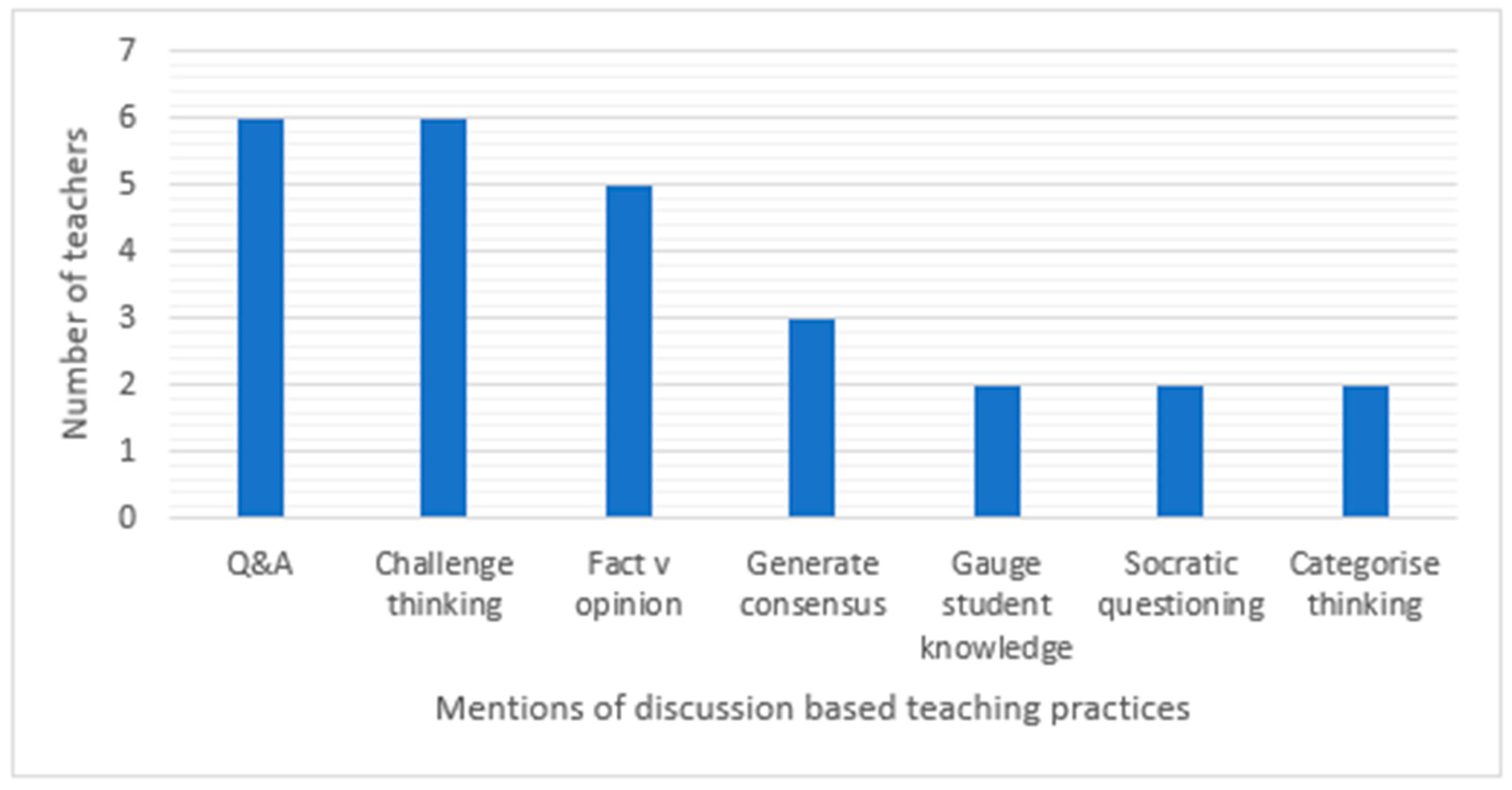

In Phase 2, participants were asked to describe what discussion-based teaching looked like in their classroom; these data are represented in Figure 1 (below). A total of 6 of the 19 teachers who responded to this question described class discussions as “Q&A”; 6 teachers described the class discussion as a time to challenge incorrect thinking and for the teacher to challenge thinking; 5 teachers classified student responses as either fact or opinion and suggested that students needed to know the difference; 3 teachers used the discussion to generate consensus within the class as a process to construct knowledge; 2 teachers used the discussion to gauge students’ knowledge on a topic; 2 teachers mentioned the use of Socratic or open questioning; and 2 teachers used a process whereby they categorised student responses as healthy or unhealthy and then discussed how students can shift their behaviour to be more healthy.

Figure 1.

Discussion-based teaching practices.

3.3. Sharing Behaviours

In Phase 1 interviews, teachers discussed their experiences in class when teaching what they described as uncomfortable, controversial, or difficult topics. In these discussions, five teachers expressed that they were very careful about what they said in class and how they reacted to different conversations or content.

Teachers made it clear that while they held their own views and, at times, shared their personal beliefs with the class, they also taught across a range of beliefs and life choices. Teachers explained that they shared personal examples to help students understand the topic and to make the discussion more real and authentic but were very clear about the need to state to students when a personal belief was being shared.

Coding of the Phase 1 transcripts revealed the category ‘discussion-based teaching methods’, with the discussion element of the lesson shown to be where personal beliefs would be shared.

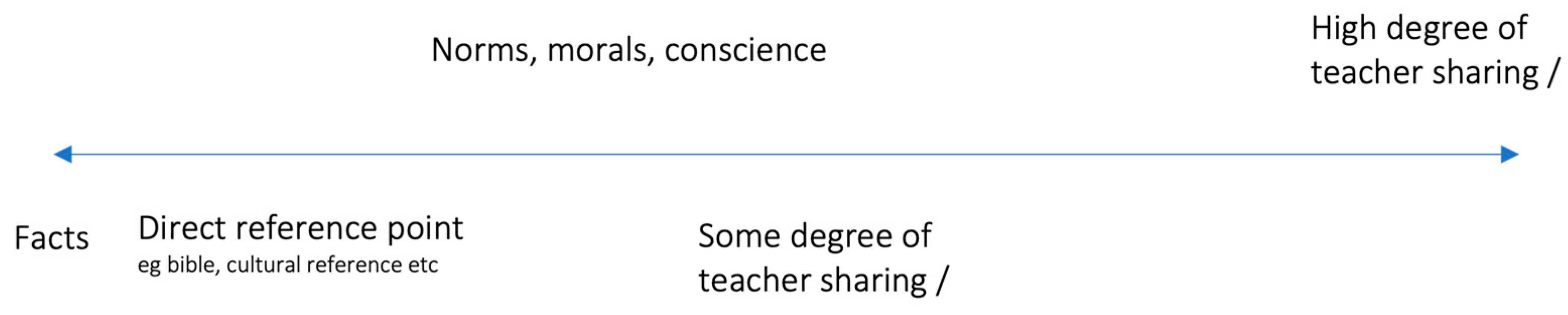

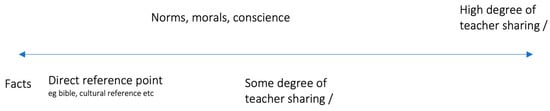

As teachers described their personal belief sharing practices, the grounded theory method of memoing was used together with annotating a spectrum diagram (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

Spectrum of sharing.

This spectrum was annotated to reflect what the teachers were saying about their sharing behaviours in class. Twenty-two memos were made based on the transcripts from Phase 2 interviews and then combined onto one spectrum for analysis. This process revealed that participants could be separated into three distinct groups based on the level of sharing they described. These three groups were labelled High Sharers, Mediated Sharers, and Low Sharers.

High sharers were participants who shared across the spectrum from facts and figures to storytelling to first-person sharing. First-person sharing was seen as the highest level of sharing because it would most directly reveal a teacher’s personal beliefs and worldview. These teachers were very open about sharing their views with students, often sharing facts, statistics, media stories, personal stories, the Bible (for Christian teachers), and personal stories told in the third person. One participant described the power of being vulnerable while sharing personal stories with classes, “If you’re exploring emotions, or exploring values, to relate that personal story, I think is, is quality pedagogy related to your own context and relate it to how it’s supported or hindered. Obviously, that would have to be appropriate. But sharing a personal story has, has proven on a number of occasions from a personal perspective to, to create some magical teaching moments.”

Mediated sharers also shared facts and participated in storytelling but mediated their sharing to use third person instead of first person. While this still revealed the teachers’ beliefs and worldview, it was less direct and thus mediated. These teachers formed the most common category with 12 of the participants in this group. They were also often sharing personal views with classes, similar to the high sharers, but they mediated the sharing by using pseudonyms, third-person narratives, documentary or media examples and facts. A participant explained how the third-person method is used, “If there’s a good story that I know will engage them, but I don’t want them to I know it was me. Be like, Yeah, I know this person one time that went to this country, or I don’t know, did this thing.”

Low sharers were participants who stated they did not engage in storytelling or sharing personal anecdotes and stuck to facts and figures. This was the smallest group with only three participants, who expressed they did not share personal views at all. There was an acknowledgement by these teachers of how difficult this practice was and they admitted to avoiding content in lessons due to inability to remain neutral and not share personal views.

Mediated and high sharing behaviours were the most preferred by teachers in this study. Teachers should share their stories because they “have powerful, positive stories of determination and perseverance, stories that reflect who they are as people and as learners” [16]. This study suggests that school leaders need to better prepare teachers in how to share their stories and facilitate engaging dialogue with students.

4. Discussion

Health teachers are aware of the need for students to engage meaningfully with PSCH content. They are conscious of the need to present content in a way that students can understand, while reframing misunderstandings and guiding students to question assumptions and explore multiple perspectives. Teachers encourage students to reflect and make informed decisions about what they believe to be true or morally right.

It would seem health teachers do not want to add to the misconceptions and misinformation that is already in the public discourse; hence, they work hard in discussion-based classes. This was explained by a participant when describing the teaching of sensitive topics, “They’re exhausting those lessons, because you’re thinking all the time, and making sure that what you say is going to be, there’s no other interpretation to what you say that could lead a kid down the wrong path.”

Teachers need to make a series of decisions when planning a health education lesson. Siuty, Leko, and Knackstedt [17], in their study of teacher decision-making in USA, reported that once teachers had decided upon “what to teach”, they next focused on “how best to” teach. Within the Western Australian curriculum, the PSCH curriculum writers included the innovative five propositions to support teachers as they engage with the PSCH content, providing clues as to ‘how’ to teach it [7]. Unfortunately, many teachers in this study were unaware of the propositions or had not fully engaged with them, so efforts by ACARA and the PSCH creators to guide teaching of the PSCH missed the mark.

Teachers in this study referred to presenting students with information, conducting class (or small-group) discussions, and designing inquiry-based tasks. However, most preferred discussion-based lessons.

In discussion-based lessons, the focus for teacher decision-making was on selecting a stimulus for the discussion or on generating a set of guiding questions. Borgerding and Dagistan [18], in their work regarding the teaching methods used to deliver controversial topics in the USA, reported that whole- or small-group discussions were favoured by many teachers. Participants in Borgerding and Dagistan’s [18] study described presenting students with information prior to the discussion so they could “look at it critically for themselves” and have a basis of facts and information prior to open discussion. Likewise, in this study, a participant reported, “We give them information, or we give them a piece of reading.”

Borgerding and Dagistan [18] also reported that teachers were keen to make sure that “there are multiple viewpoints rather than just one-sided” views being shared. This finding often occurred where teachers reported an aim of discussion-based learning to “get to hear other people’s opinions” and to “reflect on their own values” after hearing the views of others.

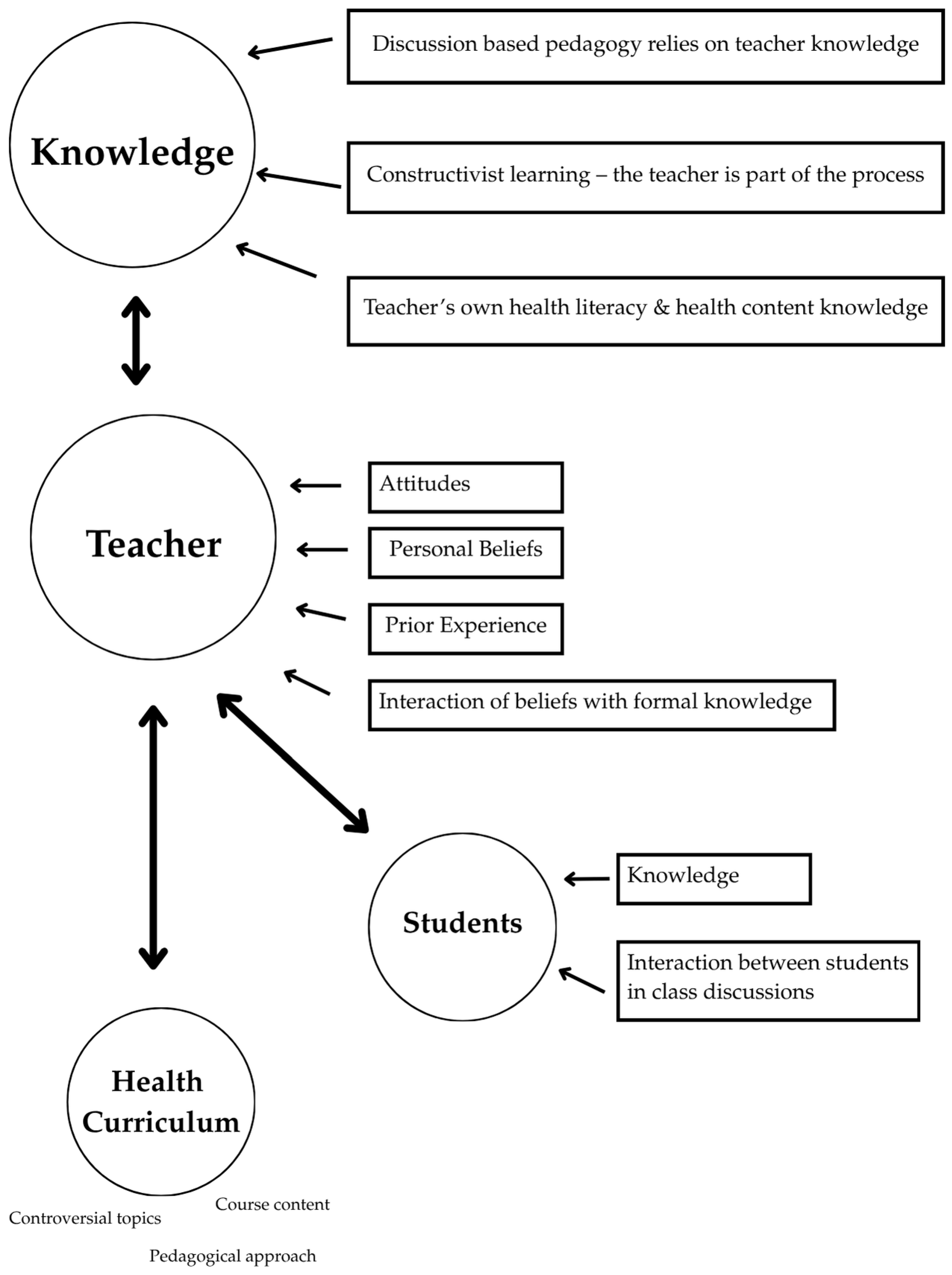

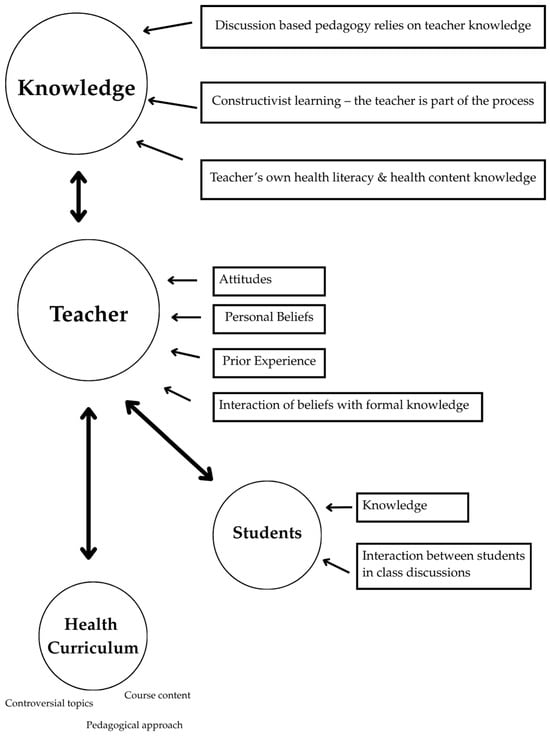

Grounded theorists look for ideas by studying their data and then returning to gather more focused data to answer analytic questions and fill conceptual gaps. While studying the data regarding the preference for discussion-based teaching and searching for literature detailing the use of discussion-based pedagogy, this conceptual model of the elements of discussion-based teaching was developed (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Discussion-based pedagogy schematic [1,7,19,20,21].

This schematic indicates the main elements of discussion-based teaching, such as the role of the teacher, who was clearly not a neutral bystander in the process [1,20]. This research placed emphasis on the teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experience.

According to the schematic derived from the literature, depicted above in Figure 3, teachers needed to be well-versed in the content and have well-developed knowledge of constructivist pedagogy to be able to guide and monitor discussions such as these. This acknowledgement of the knowledge required by health education teachers to lead these discussions was highlighted by a HPE teacher when talking about non-HPE teachers leading a lesson. “He will not be able to dive into conversations the way that our teachers can.”

When preparing for discussion-based learning experience, teachers needed to decide whether to be authentic or neutral (and to which extent in each). Smith et al. [22] reported that teachers were uncertain about what is acceptable to say in class and feared backlash if they shared personal beliefs in class. This uncertainty could lead some teachers to adopt a neutral stance to avoid sharing personal views. Conversely, Abbasi [23] reported that the role of the secondary school teacher in moral and identity formation was to actively guide and support students rather than remain neutral.

Teachers in this study were classified as either high, mediated, or low sharers based on their accounts of the manner in which they participated in class discussions and shared their personal stories. One of the decisions teachers had to make was how much they would share of their personal perspective. Low sharers (of whom there were only three in this study) mainly subscribed to the philosophy of taking a neutral stance with the teacher maintaining distance between the subject matter and the students. The concept of neutrality has been contested by many scholars and studied internationally in several learning areas including health education, humanities, and sciences. Neutrality seemed to be of most importance when teachers were required to teach content that is considered controversial or sensitive, such as politics and history for humanities teachers, climate change and evolution for science teachers and sexuality for health teachers.

The opposite of neutrality has been described as authentic teaching, where teachers “bring parts of oneself into interactions with students” and be “defined by oneself rather than by others’ expectations” [24]. Cohen [20] also explored authenticity in the classroom and highlighted the importance of creating an authentic environment where teachers can show their authentic selves and the students are also allowed to show their authentic selves. Cohen referred to Palmer’s [25] teaching theories regarding authenticity, in particular his reference to the following, “Our deepest calling is to grow into our own authentic self-hood, whether or not it conforms to some image of who we ought to be. As we do so, we will not only find the joy that every human being seeks—we will also find our path of authentic service in the world” (p. 16).

A teacher’s personal perspective interacting with the curriculum and the evolving teaching perspective is what McCuaig and Tinning [26] referred to as the uniqueness of health education, as a “profession that values its moral education role.” They argued that health teachers had something unique to offer students because of its special subject matter and caring teacher–student relationships. This study affirms McCuaig and Tinning’s findings that health education offers a special opportunity for discussion and conversation between students and teachers.

Discussion-based teaching emerges as a highly valued and effective approach within Health education, both due to the preference of educators and in terms of student outcomes. Teachers appreciate its flexibility, relevance, and capacity to engage learners in meaningful dialogue about real-life health issues. When students are given space to explore ideas, share experiences, and critically reflect with their peers, they are more likely to internalise health education concepts and apply them to their own lives. However, it is important to recognise that effective discussion-based teaching requires authenticity on the part of the teacher. Rather than adopting a position of neutrality, teachers must be willing to participate in discussions with openness and care, offering guidance, sharing values, and modelling respectful engagement. This relational and involved stance not only supports deeper understanding but also empowers students to make informed choices that contribute to healthier, more active lifestyles.

Practically, in Western Australian schools, teachers need to be given time to explore and reflect on their use of discussion-based teaching practices in health education. They need support from school leadership to help them make decisions about neutrality and authentic teaching in relation to the controversial and sensitive topics in the health curriculum. This has implications for teacher training (both pre-service teachers and in-service teachers), whereby teachers need assistance to develop schemas for planning discussion-based lessons and empowering them to show up authentically in class to help guide and support their students.

In order to increase transparency, school leaders need to engage health teachers in conversations about school stance and ethos to ensure alignment between the discussions occurring in health education classes and the vision or aim of the school. Increased openness about the structure of a discussion-based lesson, the stance of the school regarding controversial topics and the notion of authenticity will ultimately empower teachers to hold respectful and meaningful discussions with students and provide guidance as they navigate adolescence.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights discussion-based teaching as a central pedagogy in health education, valued for its ability to foster critical thinking, moral reflection, and authentic engagement with sensitive content. While neutrality may have its place, the findings suggest that authenticity is key to facilitating meaningful dialogue. By intentionally guiding discussions, challenging misconceptions, and encouraging multiple perspectives, health teachers not only deepen students’ understanding but also equip them with the capacity to navigate complex health and social issues with confidence, empathy, and informed judgement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.; writing—review and editing, J.B.-B. and P.D.; supervision, J.B.-B. and P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted with ethics approval from the Higher Education Ethics Panel at the Alphacrucis University College, March 2020, the approval code is EC00466.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HPE | Health and Physical Education |

| ACARA | Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. |

| PSCH | Personal, Social, Community Health |

| AC:HPE | Australian Curriculum, Health and Physical Education. |

References

- Kaymakamoglu, S.E. Teachers’ Beliefs, Perceived Practice and Actual Classroom Practice in Relation to Traditional (Teacher-Centered) and Constructivist (Learner-Centered) Teaching (Note 1). J. Educ. Learn. 2017, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arega, N.T.; Hunde, T.S. Constructivist instructional approaches: A systematic review of evaluation-based evidence for effectiveness. Rev. Educ. 2025, 13, e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A. Australia’s Education Perspectives: Historical Evolution and Current Trends. J. Taiwan Educ. Stud. 2025, 6, 345–369. [Google Scholar]

- Alfrey, L.; O’Connor, J. Critical pedagogy and curriculum transformation in Secondary Health and Physical Education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuaig, L.; Carroll, K.; Macdonald, D. Enacting critical health literacy in the Australian secondary school curriculum: The possibilities posed by e-health. Asia-Pac. J. Health Sport Phys. Educ. 2014, 5, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, V.; Pill, S.; Williams, J.; Nash, R.; Mainsbridge, C.P.; MacDonald, A.; Elmer, S. Exploring the ‘everyday philosophies’ of generalist primary school teacher delivery of health literacy education. Curric. Stud. Health Phys. Educ. 2022, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K. Practitioner initial thoughts on the role of the five propositions in the new Australian Curriculum Health and Physical Education. Curric. Stud. Health Phys. Educ. 2018, 9, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACARA. Health and Physical Education. 2016. Available online: https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/curriculum-information/understand-this-learning-area/health-and-physical-education (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Collier, J.; Dowson, M. Beyond Transmissional Pedagogies in Christian Education: One School’s Recasting of Values Education. J. Res. Christ. Educ. 2008, 17, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, C. Critical pedagogy in health education. Health Educ. J. 2014, 73, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.L. The Futures of Learning 3: What kind of pedagogies for the 21st century? Int. J. Bus. Educ. 2023, 164, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuaig, L.; Quennerstedt, M.; Macdonald, D. A salutogenic, strengths-based approach as a theory to guide HPE curriculum change. Asia-Pac. J. Health Sport Phys. Educ. 2013, 4, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Philpot, R.; Gerdin, G.; Schenker, K.; Linnér, S.; Larsson, L.; Mordal Moen, K.; Westlie, K. School HPE: Its mandate, responsibility and role in educating for social cohesion. Sport Educ. Soc. 2020, 26, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Teaching Theory Construction with Initial Grounded Theory Tools: A Reflection on Lessons and Learning. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.J. Personal Story Sharing as an Engagement Strategy to Promote Student Learning. Penn GSE Perspect. Urban Educ. 2019, 16, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Siuty, M.B.; Leko, M.M.; Knackstedt, K.M. Unraveling the Role of Curriculum in Teacher Decision Making. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. J. Teach. Educ. Div. Counc. Except. Child. 2018, 41, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgerding, L.A.; Dagistan, M. Preservice science teachers’ concerns and approaches for teaching socioscientific and controversial issues. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2018, 29, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterelyukhin, M. Discussion-Based Learning in a Harkness-Based Mathematics Classroom. Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, C.Z. Applying Dialogic Pedagogy: A Case Study of Discussion-Based Teaching; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pajares, M.F. Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning up a Messy Construct. Rev. Educ. Res. 1992, 62, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Schlichthorst, M.; Mitchell, A.; Walsh, J.; Lyons, A.; Blackman, P.; Pitts, M. Sexuality Education in Australian Secondary Schools—Results of the 1st National Survey of Australian Secondary Teachers of Sexuality Education 2010 Sexuality Education in Australian Secondary Schools; Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, Ed.; La Trobe University: Bundoora, VIC, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, N. Adolescent identity formation and the school environment. In The Translational Design of Schools; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreber, C.; Klampfleitner, M.; McCune, V.; Bayne, S.; Knottenbelt, M. What do you mean by “authentic”? A comparative review of the literature on conceptions of authenticity in teaching. Adult Educ. Q. 2007, 58, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, P.J. Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McCuaig, L.; Tinning, R. HPE and the moral governance of p/leisurable bodies. Sport Educ. Soc. 2010, 15, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).