Abstract

This study examined the effects of perceived parenting styles and restrictive parental internet intervention on adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors in Macau. A survey conducted in 2023 gathered responses from 708 secondary school students aged 12 to 18. The findings indicated that fathers’ authoritative and permissive parenting styles were positively associated with adolescents’ experiences of cyberbullying, both as perpetrators and victims. Mothers’ authoritative style was significantly associated with increased cyber-victimization. Notably, when mothers used an authoritative style and also applied restrictive internet intervention strategies—such as time or content controls—adolescents reported higher levels of cyber-victimization. These results suggest that rigid control, if not combined with open communication, may heighten risk. This study highlights the importance of involving both parents—particularly fathers—in adolescent media education and calls for increased awareness in social work, education, and family policy to prevent and mitigate cyberbullying in the digital age.

1. The Background of This Study

The current study used Baumrind [1,2] to frame the association between parenting styles, parental internet intervention strategies, and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors. The existing literature found that parenting style was related to cyberbullying [3] and discussed the finding that restrictive parental internet intervention (RPII) acts as a moderator between parenting style and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors.

Cyberbullying is a recent trend in bullying [4,5], and “no child is entirely safe from online risks,” says the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Cyberbullying is bullying through the use of digital technologies. It can take place on social media, messaging, gaming, and mobile phones. It is a repeated behavior that is aimed at scaring, angering, or shaming those targeted. There are adverse effects for victims of cyberbullying, such as isolation, sleeping disorders, anxiety, depression, and even committing suicide [6,7]. Previous studies noted that cyberbullying might also be related to internalized problems, such as lower self-esteem, or externalized and physical symptoms, such as self-harm, aggression, and/or social problems [7,8]. Similar insights were found in Hong Kong [9]. The perpetration and victimization of cyberbullying correlate negatively with adolescents’ self-efficacy, empathy level, and psychosocial conditions.

Cyberbullying is an increasingly widespread trend. In 2011, 15% of the parents interviewed in the United States reported that their own children had experienced cyberbullying, and the percentage increased to 26% in 2018. In 2011, 11% of parents in China reported that their children were victims of cyberbullying, and this rose to 17% in 2018. In Macau, a Special Administrative Region (MSAR) of China, 3690 secondary school students participated in a survey, and 4.1% of the participants claimed to be perpetrators of cyberbullying, and 11.2% had been victims of cyberbullying [10].

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) reported that around 84% of parents worldwide were worried about their children’s online lives [11]. Some 30% of parents in Macau thought that children’s and adolescents’ use of the internet should be monitored [12]. The behaviors of families and parents have been found to be correlated with negative outcomes for adolescents involved in aggressive or bullying behaviors [7,13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, knowledge concerning the role of parenting styles in adolescents’ engagement in cyberbullying is scarce [19,20].

A high prevalence of cyberbullying has been found in Hong Kong, ranging from 12% to 72% for victimization and 13% to 60% for perpetration [9]. Previous research found that perceived social acceptance of cyberbullying behavior, internet self-efficacy, motivations, and experience of cyberbullying victimization were strong statistical predictors of cyberbullying perpetration behaviors in Hong Kong [19].

In Macau, research on cyberbullying is scarce, with empirical studies focusing on traditional school bullying [20,21]. Using a sample of children aged 10 to 20 years, researchers indicated that victims experienced strong feelings of anxiety and depression and expressed low satisfaction with life [20]. More recently, scholars investigating 2185 young people from Hong Kong, Macau, and Guangzhou found that 71% of participants had been victims, and 63.7% had been perpetrators [22], showing that cyberbullying is extensive in the Greater Bay Area of Southeast China.

2. Parenting Styles and Adolescents’ Cyberbullying Behaviors

Family plays an important role in a person’s life, but how does it affect us? The celebrated psychologist Alfred Adler [23] put forward the point that if parents use inadequate methods of child-rearing for their children, display a lack of compassion for their children, or use unnecessary punishment, then their children may feel that life is full of suffering and, as a result, have a hostile attitude towards the world.

Diana Baumrind’s Pillar Theory emphasizes that a child’s behavior is associated with parenting styles as they grow and interact with new people. Parenting styles have always been perceived to be a major factor in children’s development. Parenting style has been found to predict child well-being in the domains of social competence, academic performance, psychosocial development, and problem solving [24]. In Baumrind’s theory, at its inception, she suggested that there are three different parenting styles, including authoritative, authoritarian, and indulgent parenting styles [25]. Later, based on the work of Maccoby and Martin [26], Baumrind [1,2] further expanded her typology to include the ‘neglectful parenting style’ as the fourth type. The parenting styles were classified according to two dimensions: parental responsiveness and parental demandingness [2]. Here, first, the ‘authoritative parents’, combining high responsiveness and high demandingness, were more likely to be trusted, reliable, and likely to be respected and obeyed by virtue of their effective leadership, expertise, and charisma [2]. Second, the ‘authoritarian style’, making higher demands but with lower responsiveness, was characteristic of an ‘authoritarian style’. Parents who adopted this type expected children to obey and conform and did not appreciate their autonomy and independence. Third, the ‘permissive style’ referred to parents with a high level of responsiveness but lower demandingness. Parents are highly responsive and supportive of their children, while giving them freedom simultaneously, which might turn into permissiveness, allowing them to do whatever they wish without restrictions. And lastly, neglectful parenting was the least ideal parenting style [26]. Many scholars demonstrated that the neglectful parenting style led to negative consequences for children [27].

Studies found that parenting styles predicted adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors statistically with regard to the four parenting styles [28,29]. Firstly, the authoritative parenting style was found to correlate less frequently with all cyberbullying behaviors [28,29,30,31]. Secondly, the authoritarian parenting style can put children at risk of bullying or being bullied in cyberspaces [29,31,32]. Previous research noted that adolescents from authoritarian families reported higher levels of cyber-victimization than those from permissive or authoritative families [29]. Additionally, adolescents who experienced an authoritarian parenting style could have a higher percentage of cyberbullying offences [3,15,28,29,32,33]. Thirdly, the permissive parenting style led to different outcomes. It was found to be related statistically to a lower level of perpetration and victimization of cyberbullying [30,31]. In contrast, researchers found that adolescents experiencing a permissive parenting style were more likely to be bullied in cyberspaces [34]. Lastly, the neglectful parenting style was found to increase adolescents’ perpetration of cyberbullying [34]. Further, differences in parenting styles can be found between mothers and fathers. A systematic review investigated differences between mothers and fathers in parenting styles [35]. Here, 28 articles were included in the review, and the findings indicated that, from the perspectives of the parents and the children, mothers were reported to be more authoritative and permissive than fathers, and fathers were more authoritarian than mothers in overall parenting. Informed by these findings, the present research reported here investigated the possible correlations between parenting styles and cyberbullying and being cyberbullied.

In recent years, studies have found that parenting styles may predict adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors. First, an authoritarian parenting style is linked to their child being cyberbullied [29,31,32]. Adolescents from authoritarian families reported higher levels of cyber-victimization than those from permissive or authoritative families [29]. Further, adolescents who witness, or are subject to, an authoritarian style of parenting might have a higher percentage of committing cyberbullying [15,28,29,32,33]. In western countries, authoritative parenting is described as positive parenting that results in the best possible outcomes for children [2], while authoritarian parenting has been associated with several problematic behaviors in children [36]. However, scholars argued that authoritarian parenting should not be considered a negative parenting style, as it is viewed as a way of showing affection and involvement in Chinese cultures [37]. Some scholars found that authoritarian parenting improves child outcomes in Asian cultures and is correlated with academic performance in China [4] and Japan [38] and with cyberbullying behaviors in Indonesia [39]. Adolescents who experience a non-authoritarian parenting style have a higher risk of being cyber-victimization [39]. It remains unclear whether findings in Western societies are applicable to other ethnic societies [9], as ecological context is considered to be an essential element in shaping parenting styles [39,40], and child-rearing practices also reflect prevailing cultural values [41].

Second, scholars indicated that adolescents who experienced a permissive parenting style were found to have less cyberaggression than others [31]. However, there were different outcomes concerning cyber-victimization. Some found that permissive parenting was associated with the lowest level of victimization [32]. In contrast, other scholars found that a permissive parenting style was most likely to result in their adolescent child being bullied in cyberspace [34]. From these studies, it appears that the authoritarian parenting style may be related to an increase in the experience of adolescents’ cyberaggression, and permissive parenting differs between studies with regard to bullying or being bullied. Although the relationship between parenting styles and cyberbullying behaviors seems to be clear, it is notable that these results come from Western studies, and currently, there is little research published on the situation of Chinese societies.

3. Parental Internet Intervention and Adolescents’ Cyberbullying Behaviors

Regulating children’s media by using parental internet intervention has become more challenging for parents because of the proliferation of media goods [42]. A parental internet intervention strategy was found to be associated with parenting styles, and in turn, parental internet intervention strategies have been found to be associated statistically with the perpetration and victimization of cyberbullying [39,43].

There are diverse categories of parental internet strategies. For example, previous research defined three methods of mediation: ‘restrictive mediation’, ‘co-viewing’, and ‘instructive mediation’ [44]. Restrictive mediation is where parents make rules to regulate the time spent on viewing specific content, and they might use it as a reward or punishment. ‘Co-viewing’ is a shared set of motivations for viewing. ’Instructive mediation’ means making efforts to discuss content in words that children can understand [45]. Parental intervention strategies are defined as follows: ‘active co-use’; ‘technical restrictions’; ‘interaction restrictions’; and ‘monitoring’ [42]. ‘Active co-use’ sets rules on time spent on the internet, with parents staying nearby or sitting at the children’s side while their children are online and looking at the screen and talking to children about internet use, in addition to the usage of filters and/or monitoring software. ‘Interaction restrictions’ prohibit children from using specific online media, such as e-mail, chat rooms, or playing online games, etc. ‘Monitoring’ comprises a strategy of checking the websites that children have visited, as well as the e-mails or instant messages that they have sent or received.

Researchers in Taiwan adapted the 2010 ‘EU Kids’ online survey parental mediation scale and used it with 1917 participants from junior high schools. The results indicated that RPII was a significant factor in cyberbullying perpetration, victimization, and internet addiction [43]. Scholars investigated the relationships between parenting style and parental internet intervention of media use. They found that RPII was associated with parenting styles [46,47]. For example, for the restrictive parenting style, parents intervened with regard to their children’s internet usage, making rules to regulate the time spent on viewing specific content and used the internet as a reward or punishment [45]. It was observed that the more the parents controlled the time spent on the internet, following a lack of care from the parents, the greater the chance of their adolescent children becoming perpetrators of cyberbullying [48]. Scholars reported that parental monitoring was negatively related to both the perpetration and victimization of adolescents’ cyberbullying [15]. A recent study showed that authoritarian parenting alleviated cyberbullying among teenagers [39].

Furthermore, less frequent RPII was found to be statistically associated with reduced online risks and time spent online [49]. However, other studies indicated that controlling parenting, such as using RPII, was not statistically significantly associated with any forms of online aggression [18]. For example, using software to check the viewing history of their adolescent child was not effective in reducing their aggressive behaviors online [50].

Parents’ restrictive intervention strategies have been investigated as a moderator in the literature. Scholars investigated the relationship between adolescents and their consequent adjustment difficulties, finding that parental restrictive intervention was not only statistically significantly correlated with adolescents’ behavior outcomes but also that it played a moderating role [51].

In the current study, the moderator ‘RPII’ was taken to be both an independent variable that derived from and had been tested in past studies, and it is a contextual factor in the study in question, i.e., it had considerable potential influence and relevance. Parents’ interventions in preventing children’s television and cell phone usage correlated positively with the authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting styles [47]. Here, research also reported that parents’ RPII was a significant factor in cyberbullying perpetration, victimization, and internet addiction [39,43], i.e., it had a role to play in investigating the nature and strength of the relationships between parenting style and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors.

A previous study found that permissive parents did not monitor adolescents’ usage of the internet, while authoritative parents were more likely to set restrictions on their children’s usage of the internet and were found to have more rules for their children’s use of the internet [52]. At the same time, more control over internet access was found to lead to a greater likelihood of the adolescent bullying others on the internet [48]. A research study that recruited parents in Israel found that authoritarian and permissive parents were subsequently less active in mediating their children’s exposure and access to pornography. In contrast, authoritative parents mediated internet usage more restrictively regarding pornography. They found that fathers were reported to have less caring mediation than mothers [53]. Another study examined the moderating effect of RPII on the relationship between active mediation and time spent online by a child [54]. These studies suggested that the RPII influenced the statistical significance of the positive relationship between active mediation and time spent online by the child.

Investigating the effect of RPII as a moderating variable aimed to clarify the nature and strength of the relationship between parenting styles and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors. Specifically, the moderation analysis assessed whether and to what extent the association between parenting styles and cyberbullying varied across different levels of RPII (i.e., high vs. low).

In the Macau context, little is known about how restrictive parental mediation affects this relationship. This study, therefore, hypothesized that parental restriction would serve as a moderator between perceived parenting styles and cyberbullying outcomes.

Cyberbullying in Macau is increasingly recognized as a public health concern. However, the empirical literature on this issue remains limited. First, research on cyberbullying within Chinese contexts is sparse, particularly regarding its psychosocial impacts. Second, most existing studies in Macau focus on traditional (offline) school bullying [20,21]. Third, there is a gap in studies that examine how parenting dynamics contribute to adolescents’ experiences of online victimization and perpetration.

This research addressed two research questions and hypotheses, as indicated below:

Research Questions:

- Are parenting styles associated with adolescents’ perpetration and victimization of cyberbullying, and if so, how?

- Does restrictive parental internet intervention moderate the relationship between parenting styles and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors in Macau?

Hypotheses:

- Parenting styles (authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful) are significantly associated with adolescents’ perpetration and victimization of cyberbullying.

- Restrictive parental internet intervention moderates this relationship such that the association between parenting styles and cyberbullying behaviors varies in magnitude depending on the level of restriction applied.

4. Theoretical Framework

The present study draws upon Baumrind’s parenting style typology [1,2] as the core theoretical lens for examining the relationship between parenting behaviors and adolescents’ involvement in cyberbullying, either as perpetrators or victims. Baumrind classifies parenting into four styles—authoritative, authoritarian, permissive (indulgent), and neglectful—based on two primary dimensions: responsiveness and demandingness. Authoritative parenting, marked by high responsiveness and high control, is generally associated with positive child outcomes, particularly in Western cultures. Conversely, authoritarian parenting (low responsiveness and high control) is linked to stricter rule enforcement and, in some contexts, adverse behavioral outcomes. However, studies from East Asian cultural contexts [4,37] suggest that authoritarian parenting may serve different functions, including expressions of care or investment in academic success. These cultural nuances are particularly relevant for interpreting parental behavior in the Macau context.

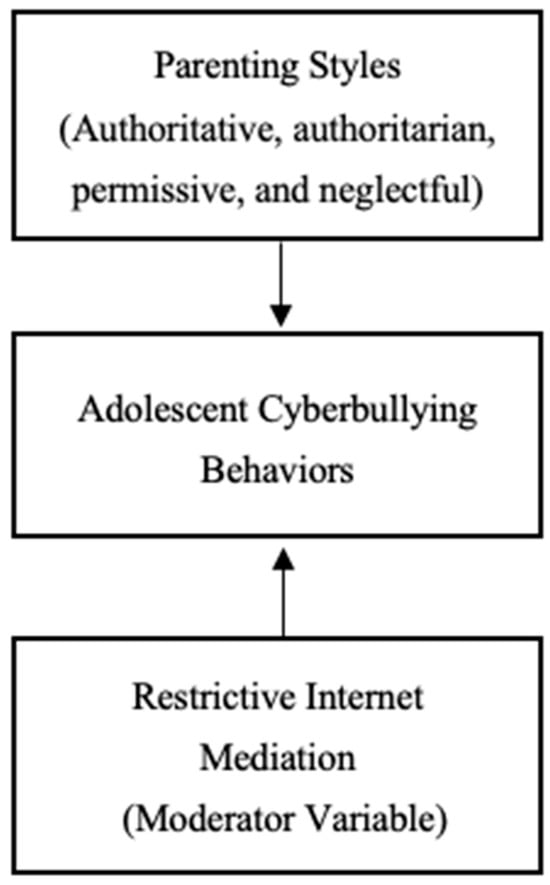

To structure this study’s assumptions, the following conceptual framework (Figure 1) illustrates the proposed relationship between perceived parenting styles and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors, with restrictive internet intervention modeled as a moderator. The framework is grounded in Baumrind’s typology [1,2] and reflects prior findings suggesting that parenting control strategies—especially RPII—can either buffer or exacerbate behavioral outcomes in digital contexts [48,54]. In this model, RPII is hypothesized to alter the strength or direction of the relationship between parenting styles and the likelihood of cyberbullying perpetration or victimization.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

5. Methodology

5.1. Participants

The geographic location of this project was Macau, an enclave of China in the Greater Bay Area of Southeast China. This study used a convenience sampling strategy by recruiting participants aged 12 to 18, which refers to Form 1 to Form 6 in Macau’s local schools. It is often difficult to obtain access to schools because they are reluctant to put their reputation at risk (“fear of scrutiny and exposure”) [55] (p. 262) and because Macau is a small territory. It is not uncommon for schools to be asked repeatedly to take part in research, putting them at risk of ‘‘questionnaire fatigue’ and of being endlessly researched, with the more ‘cooperative’ schools being even more over-researched [55] (p. 255). As a researcher noted, “not only is it almost impossible not to identify a school in Macau, but the very fact that a researcher is working in a school quickly becomes public knowledge” [55] (p. 254). Hence, finding participants often relies on personal connections, and there is a compelling need for schools and participants to be non-traceable; hence, fuller details are excluded here. Often, as in the present case, a convenience sample was the only possible sampling strategy, and as Morrison observed, it is either that or “doing nothing” [55] (p. 255).

This study recruited 708 participants. In addressing inclusion criteria, information from Macau’s Education and Youth Development Bureau (DSEDJ) indicated that there were thirty-six Chinese schools in Macau. From these, three selection criteria were used. Firstly, schools had to be non-residential, because the current study aimed to investigate the association between the parenting that adolescents perceived and their cyberbullying behaviors. Secondly, the schools should provide student participants from Form 1 to Form 6 to cover the age range of adolescents. According to the literature above, adolescents aged 12 to 15 had the highest rates of being bullied or bullying others in cyberspaces, and such behaviors decreased by age; hence, students studying from Form 1 to Form 6 were involved to include a wide range of adolescent ages. Thirdly, single-sex schools were excluded, as the intention was to investigate what happened when male and female students were together in school. Nine schools were excluded from the list, such as special education schools (n = 1), residential schools (n = 2), closed (n = 1), and technical schools (n = 5). This is because technical schools enrolled students over 18, and students living in a residential school were separated from family interactions. The data used came only from all the students who had returned parental permission. The self-administered questionnaires were delivered in paper-based formats. The research team sent out invitation letters to school principals to explain the rationale of this research. After agreeing to join this study, informed consent forms were sent to the parents because the participants were under 18 years old. Participants took approximately 40 min to complete the questionnaires, with a face-to-face introduction.

5.2. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the university’s Research Ethics Committee. All data were anonymous and non-traceable to individuals or schools. Participants were informed of their right to decline participation and to withdraw from the research if they wished once it had begun, without having to give a reason. The survey questionnaire was given only to those students who had returned parental consent forms, and there was no coercion to participate.

6. Measurements

6.1. Cyberbullying Behaviours

The Cyber Bullying Inventory (CBI) was first developed by Erdur-Baker in 2007 and was used in a study conducted by Erdur-Baker and Kavsut in 2007. Later, the inventory was revised, and the Revised Cyber Bullying Inventory (RCBI) consisted of two parallel forms: one for measuring cyberbullying perpetration and the other one measuring cyber-victimization [56]. Topcu and Erdur-Baker sampled 697 participants aged between 13 and 21 from two different schools using the RCBI. Participants were asked to rate themselves on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = ‘‘It has never happened to me’’, 2 = ‘‘It happened once or twice’’, 3 = ‘‘It happened three to five times’’, and 4 = ‘‘It happened more than five times’’). An example of this is given here: stealing personal information from computers, such as files, email addresses, pictures, IM messages, or Facebook information.

The Cyber Bullying Inventory [56] has two parts with 14 identical statements providing scores for being (a) a bullying perpetrator and (b) a victim for the past six months. The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s α) of the Revised Cyber Bullying Inventory (RCBI) were 0.82 for the cyberbullying form and 0.75 for the cyber-victimization form [56]. The RCBI was empirically tested and demonstrated valid and reliable psychometric components and properties in different samples across populations. The RCBI was validated in the age group from 12 to 24 years and was applied in the Chinese population [57,58]. In the current study, the Cronbach’s α value was 0.797 for measuring adolescents’ perpetration in cyberbullying and 0.855 for measuring the cyber-victimization of the adolescents.

6.2. Parenting Styles

The current study adapted the parenting style scale developed by Yeh and Cheng [59]. One study investigated the parenting style perceived by 1281 grade 8 students in Taiwan [60]. This scale asks adolescents about the patterns of reactions, attitudes, approaches, and behaviors of their mother and father when raising and interacting with them. It uses a five-point Likert scale from 0 to 4, with anchor statements of “never”, “seldom”, “sometimes”, “often”, and “always like this.” In total, 24 items are divided into four different parenting styles, with each style having 6 items. The use of Likert scales with anchor statements was designed to be straightforward for adolescents to understand and use, and the Cronbach’s α of the scales was found to have acceptable internal reliability, ranging from 0.79 to 0.90 [60].

In identifying the items and their reliability in the current study, items 2, 8, 10, 12, 17, and 20 measured the level of authoritative parenting that participants perceived from their parents, and the Cronbach’s α value was 0.782 for the father’s parenting and 0.76 for the mother. Items 5, 6, 9, 14, 16, and 23 measured authoritarian parenting, and here, the Cronbach’s α value was 0.85 for fathers’ parenting and 0.83 for mothers’ parenting. For permissive parenting, items 4, 11, 13, 18, 22, and 24 were included, and the two Cronbach’s α values were 0.68 for fathers’ parenting and 0.65 for mothers’ parenting. The neglectful parenting style included items 1, 19, and 21, and the Cronbach’s α values were 0.61 and 0.60 for fathers and mothers, respectively.

6.3. Restrictive Parents’ Internet Intervention

This study used the parental mediation scale that was designed and used by Lin & Chen [61]. This study also adapted items from Livingstone and Helsper’s study [42]. Three 5-point Likert-scale items were listed to investigate the restrictions that participants perceived: “parents restrict me from sharing personal information to others on the internet”; “parents forbid me from videos that are not suitable for people under age”, and “parents restrict me from downloading non-authorized files.” The Cronbach’s α value of the scale was 0.746. The Cronbach’s α value for adopting the scale in this current study was 0.829. When participants rated with higher scores, this referred to them having perceived more rigorous restrictions by their parents. Later in the stage of examining the moderating effect of the variable ‘RPII’, this study divided the variable into two groups according to the mean. First, for those who scored 3 or below, this was named as “low restrictions”, and for those who scored from 3.01 to 5, this was defined as “high restrictions”.

7. Data Analysis Strategy

This study coded questionnaires into a database and processed the data using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS)® 22 software. Data cleaning and screening procedures were carried out in advance. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, standard deviations, and percentages, were generated for a comprehensive understanding of the demographic variables, such as age, sex, and marks/grades awarded for student academic performance. Whilst the Likert scale data were ordinal, interval-level statistics were used, as (a) it was assumed that the psychological distance between points was close to being equal and uniform (equal intervals), (b) the sample size was large, (c) the Central Limit Theorem permits the use of parametric methods on ordinal data if the normal curve of distribution is approximated. To address the research questions of this study, regression analyses were conducted to determine whether and to what degree the independent variable (parenting style) predicted the dependent variable (adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors). Moderation analysis examined whether parents’ restrictive intervention strategy led to variations in the associations between parenting styles and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors. To conduct moderation analysis, first, parental restrictive intervention was recoded as a dichotomous variable by way of mean splits, as indicated above. Mean splits, where a continuous moderator is divided into high and low groups based on their means, can be used to visualize and interpret this effect, e.g., for creating graphs. Previous studies examined and verified the practice of dichotomization at the mean based on valid measurement and statistical analyses, though the mean split resulted in a more conservative result, reducing the effect size [62,63]. Second, multiple linear regressions and Fisher’s Z-transformation were involved to test the moderating effect of high/low parental restrictive intervention.

8. Results

8.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 presents the disclosable descriptive statistics of the social demographic variables of the adolescents and their families. This study recruited 708 adolescents from all forms in the high schools selected in Macau, in which 413 (58.3%) of the participants were male and 295 (41.7%) were female. This study recruited students from junior and senior high schools, with more participants being from junior high schools (54.4%) and 45.6% of the participants being from senior high schools. The majority of the participants were born in Macau (86.5%); 7.1% were born in other parts of Mainland China; 4.5% of the participants were born in Hong Kong; 1.9% of the participants were born elsewhere. No fuller details of the schools and the students are included here in order to be faithful to the guarantee of non-traceability. However, the demographics indicated that there was comprehensive coverage of the student population.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the socio-demographics.

In terms of family structure, the majority of participants were living in a nuclear family (83%). In total, 13.6% of the participants were from a single-parent family, and 3.4% were living in an extended family, such as living with grandparents or other relatives. Moreover, over half of the parents were not working on shifts (69.9%), while 30.1% of parents were working on shifts. Most of the fathers and mothers had graduated from a senior high school: 256 (36.1%) for fathers and 281 (39.7%) for mothers. This all suggested that there was a comprehensive coverage of the parent population.

This study found the following: 43.6% of the participants reported spending an average of 3–6 h online per day; 24.2% of the participants estimated being 6–9 h online per day; and 19.5% spent 1–3 h online every day. Only 2.1% of the sample used the internet for less than one hour per day, and approximately 10.6% of the adolescents spent more than 9 h a day on the internet. Most adolescents used the internet for leisure purposes, such as listening to music or playing online games; 68.5% used the internet for leisure; 54% used social media platforms on the internet. In total, 83.8% of participants played online games, and among those who played online games, first-person shooting games were the most popular option (54%), followed by simulation and tower defence games (43.1%).

8.2. Influence of Parenting Styles on Adolescents’ Cyberbullying Behaviors

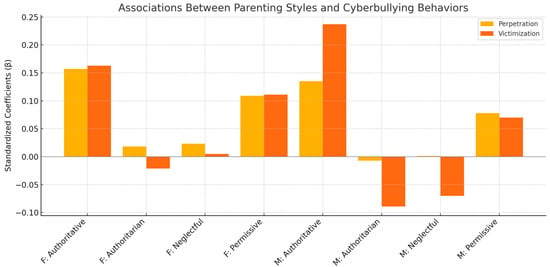

According to the first research question, the current study found a statistically significant association between parenting styles and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviours. Table 2 presents the association between the four different types of parenting styles from fathers and mothers and the adolescents’ perpetration of cyberbullying. Authoritative and permissive parenting, from both fathers and mothers, was statistically significantly positively associated with the cyberbullying perpetration of adolescents. Specifically, fathers’ authoritative parenting had statistically significant effects on adolescents’ perpetration. A one-standard-deviation increase in fathers’ authoritative parenting was associated with a 0.157 standard-deviation increase in adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration (β = 0.157, SE = 0.011, t = 4.22, p < 0.001). Permissive parenting also had a similar statistically significant effect. A one-standard-deviation increase in fathers’ permissive parenting was associated with a 0.109 standard-deviation increase in adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration (β = 0.109, SE = 0.016, t = 2.907, p < 0.05). These two types of parenting styles applied by the fathers were related to the increase in the frequency of cyberbullying by the adolescents.

Table 2.

Regression of associations between parenting styles and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors.

Essentially, a higher degree of authoritative and permissive parenting from both fathers and mothers was associated with, and predictive of, increased cyberbullying, while a lower degree of authoritative and permissive parenting was associated with, and predictive of, reduced instances. However, there were no statistically significant associations found (p > 0.05) between the authoritarian and neglectful styles of both fathers and mothers and adolescents’ perpetration of cyberbullying.

On the other hand, the authoritative parenting style of mothers was statistically associated with and predictive of perpetration. A one-standard-deviation increase in mothers’ predictive parenting was associated with a 0.109 standard-deviation increase in adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration (β = 0.109, SE = 0.016, t = 2.907, p < 0.05) (β = 0.135, SE = 0.012, p < 0.001).

The permissive style of mothers was positively associated with and predictive of the perpetration of adolescents’ cyberbullying. A one-standard-deviation increase in mothers’ permissive parenting was associated with a 0.078 standard-deviation increase in adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration (β = 0.078, SE = 0.017, p < 0.05).

Table 2 also shows the associations of parenting styles and adolescents’ cyber-victimization. As shown in the table, the authoritative and permissive parenting of fathers was positively statistically associated with and predictive of an increased incidence of adolescents being victims of cyberbullying. More specifically, A one-standard-deviation increase in fathers’ authoritative parenting was associated with a 0.163 standard-deviation increase in adolescents’ cyber-victimization (β = 0.163, SE = 0.015, p < 0.001). In terms of fathers’ permissive parenting style, a one-standard-deviation increase in fathers’ permissive parenting was associated with a 0.111 standard-deviation increase in adolescents’ cyber-victimization (β = 0.111, SE = 0.022, p < 0.01).

The results from the mothers were slightly different; the permissive parenting style of mothers did not show a statistically significant association with the victimization of adolescents. The authoritative parenting style was positively associated with and predictive of cyberbully victimization (β = 0.237, SE = 0.015, p < 0.001). On the other hand, the authoritarian parenting style of mothers was negatively associated with the victimization of adolescents. A one-standard-deviation increase in mothers’ authoritarian parenting was associated with a 0.089 standard-deviation decrease in adolescents’ cyber-victimization (β = −0.089, SE = 0.017, p < 0.05).

Figure 2 shows the standardized regression coefficients (β) of parenting styles in predicting adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. The chart visualizes the effects of fathers’ and mothers’ authoritative, authoritarian, neglectful, and permissive parenting styles on adolescents’ cyber-perpetration and cyber-victimization. Statistically significant associations (p < 0.05) are highlighted, revealing the strongest predictive effects for authoritative and permissive styles, particularly from fathers, and a notable negative association for mothers’ authoritarian style.

Figure 2.

Associations between parenting styles and cyberbullying behaviors.

Overall, fathers’ parenting styles had the same association in the relationships between both perpetration and victimization. The association between mothers’ parenting styles and the perpetration and victimization of adolescents differed slightly, as the authoritarian style of mothers had a negative association with victimization.

9. Moderation Effects of Restrictive Parental Internet Intervention

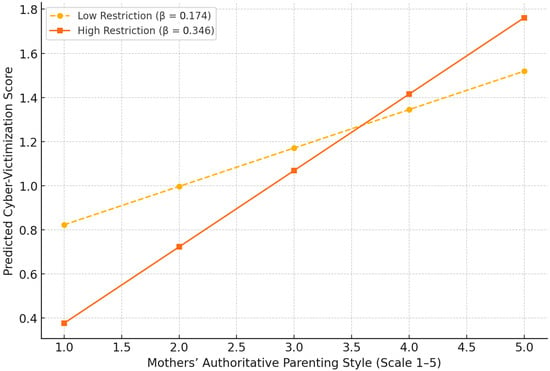

With regard to the second research question of this study, the authors found that the RPII strategy moderated mothers’ authoritative parenting style on adolescents’ cyber-victimization. Statistical moderation effects were further investigated to determine whether the association between the parenting styles and adolescents’ perpetration or victimization of cyberbullying varied according to the RPII. The results of this study indicated that more frequent internet restrictions by authoritative mothers had a stronger association with increased cyber-victimization than low levels of restriction by authoritative mothers.

Fisher’s Z analysis was conducted to identify differences between two regression coefficients derived from the high/low RPII. The calculation showed that there was a statistically significant difference between the two regression coefficients for high/low RPII (p < 0.05) by the mother with regard to cyber-victimization. Table 3 shows that, at one standard deviation above the RPII mean, the linear relationship between mothers’ high authoritative parenting style and cyber-victimization is statistically significant and positive (β = 0.346, p < 0.001), whereas the relationship between low authoritative parenting style and cyber-victimization is weaker (β = 0.174, p < 0.001). This indicates that cyber-victimization increased as mothers’ authoritative parenting style increased more when mothers applied high RPII than when their authoritative parenting style was less restrictive, and this is shown graphically in Figure 3, where the gradient of the slope was higher for ‘high restrictions’ than for ‘low restrictions’. The plot shows that higher levels of restrictive internet intervention significantly strengthen the positive association between mothers’ authoritative parenting style and adolescents’ cyber-victimization, as evidenced by the steeper slope in the “High Restriction” condition.

Table 3.

Moderating effect of restrictive parental internet intervention.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of restrictive parental internet intervention on the association between mothers’ authoritative parenting and adolescents’ cyber-victimization.

10. Discussion

This study aimed to explore associations between adolescent-perceived parenting styles, cyberbullying behaviors, and restrictive parental intervention from parents. Regarding research question 1, this study examined statistical associations between parenting styles and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors. The findings show that parents engaging in authoritative, permissive, or neglectful parenting were associated highly with their child’s risk of both cyberbullying perpetration and cyber-victimization; this suggests that further research could establish whether these associations were at all causal.

This study found that the hypothesis was supported concerning the correlations between paternal and maternal authoritative parenting style and adolescents’ perpetration and victimization of cyberbullying. Being an authoritative parent was associated positively with an increased frequency in children perpetrating bullying or being bullied in cyberspaces. In addition, mothers’ authoritative style was found to have a statistically significant positive association with cyber-victimization. These results differed from those in the existing literature [9,29]. In the existing literature, authoritative parenting is a protective factor, characterized by the highest responsiveness to the needs of children and parental warmth. However, in Macau, this research found that while parents had high expectations, they also encouraged, pressed, and supported their children to meet their expectations, echoing the findings of the Macau Catholic Family Advisory Council [64]. With the high demands of authoritative parenting on children, this type of parenting may drive children toward excessive internet use as an escape from high expectations concerning their academic performance.

One notable finding in the present study was that the authoritarian parenting style of mothers was found to be a protective factor in avoiding adolescents’ cyberbullying victimization. Authoritarian parenting is characterized by very high expectations for children, with a lack of feedback and responsiveness from the parent. This finding is consistent with the results found in Chinese societies [9,37,38,40]. Authoritarian parenting is considered to be a positive parenting style, as it is viewed as a way of showing affection and involvement in Chinese cultures and improves children’s outcomes in terms of child development and academic performance in Asian cultures. However, authoritarian parenting in Western contexts has been associated with many mental and behavioural problems in the child. Studies revealed that authoritarian parenting results in a higher percentage of adolescents engaging in cyberbullying [3,15,28,29,30,33].

Another key finding of this current study is the statistical moderation effect of the RPII on mothers’ authoritative parenting style and the cyber-victimization of adolescents. These findings could be found in many families in Macau, as traditional roles often placed mothers in charge of child-rearing and household duties [64]. Research has found that parents often use restrictive intervention as the main strategy, but it is ineffective in reducing the risk of adolescents being involved in pornography, violence, and social risks on the Internet [39,65,66]. In addition, as teenagers’ sense of autonomy is increased, the RPII provides evidence that they are not trusted by their parents, which leads to their resistance to parental management [67]. Therefore, restrictive parental intervention often failed to reduce adolescents’ online risks (such as cyber-victimization).

Consistent with past studies, mothers, when compared to fathers, were perceived to be more accepting, responsive, and supportive, as well as more behaviorally controlling, demanding, and autonomy-granting [35]. At the time of writing, according to the latest report from the social work department of Macau, approximately 30% of mothers were primarily responsible for taking care of children [68], and the present study confirms this. The restrictive parental intervention strategy moderated the association between mothers’ authoritative parenting and the cyber-victimization of adolescents. Authoritative mothers have high expectations for their children, together with more controlling actions, such as restricting internet use time or access. Here, adolescents may be more likely to refuse to communicate what they have experienced on the internet with their parents, which, in turn, might lead to a higher risk of being bullied on the internet.

11. Implications and Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, we propose several recommendations for educators, parents, social workers, and policymakers to address cyberbullying among adolescents in Macau.

For Educators and Parent Support Programs

Given that both authoritative and permissive parenting styles were associated with a higher risk of adolescent cyberbullying and victimization, schools and community centers should develop parent workshops focusing on digital parenting strategies. In addition, authoritarian parenting is an important topic that should be addressed in parenting classes, as this was found to be the only style that was associated with a lower risk of cyberbullying behaviours. These workshops can enhance media literacy, increase awareness of adolescents’ online experiences, and offer guidance on how to model safe and respectful online behaviors. Specific modules may include how digital technology impacts adolescent socialization, emotional development, and vulnerability to cyberbullying.

On Restrictive Parenting and Communication

This study found that higher levels of RPII from authoritative mothers were paradoxically linked with increased cyber-victimization. Time-based and content-based restrictions are common parental strategies, yet these may sometimes be counterproductive if not paired with open communication. Thus, parents—especially mothers—should balance restriction with dialogue and demonstrate responsiveness to their children’s needs, perceptions, and digital environments.

Promoting Active and Positive Parenting

Parents are encouraged to engage in positive interactions, such as co-viewing digital content and discussing online risks with their children. Fathers in particular should increase their emotional support and involvement in their children’s digital lives. Traditional gender roles in Macau—where caregiving is still predominantly assumed by mothers—should be reconsidered. Equal parental involvement can mitigate risks and promote a more balanced family dynamic.

On the Role of Shift Work and Structural Constraints

Many Macau families are dual-income households, with one or both parents engaged in shift work, especially in the tourism and gaming sectors. In this study, the authors found that approximately 30% of parents work shifts, and the resulting fatigue and time constraints may reduce parent–child interactions and increase adolescents’ exposure to unsupervised internet use. Policies should aim to support work–life balance, for instance, through family-friendly labor reforms, subsidies for after-school programs, and digital literacy support for domestic caregivers.

Gender Equality and Policy Recommendations

Policymakers should consider gender-sensitive approaches when designing family support programs. The 2020 Framework Law on Family Policy, including the “Family Life Education 5-Year Scheme,” is a commendable initiative but should further emphasize paternal involvement, equitable caregiving, and joint digital supervision. Addressing parenting roles in Macau’s evolving socio-economic context is essential for reducing cyberbullying risks and promoting adolescent well-being.

12. Limitations and Future Research

This study found that permissive fathering is statistically associated with both cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. However, current research in China still tends to focus primarily on maternal influence. More empirical work is needed to examine how fathers’ working schedules, emotional availability, and parenting strategies impact adolescents’ online behavior.

Second, in this current study design, the RPII of parents was not measured separately with respect to the father and the mother. Therefore, the difference between how fathers and mothers mediate adolescents’ internet usage is not yet known in Macau. This limits the current study and suggests the need to further explore the association between mothers and fathers and how this affects people with respect to internet parenting.

Third, the sample used is not representative, as the participants in the current study were all recruited by a convenience sampling strategy. Moreover, all participants were students of schools in only one undisclosed district of Macau, and this confirmed the difficulties of gaining access to schools in Macau, as indicated earlier in this article. Future studies could seek to recruit more participants from other districts of Macau, and this may help expand the characteristics, coverage, and scope of the dataset and understand more fully and comprehensively the situation of adolescents’ cyberbullying in Macau.

Fourth, bias from the Hawthorne effect may have affected the results of this study, especially the outcome of adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors. The questionnaires were self-reported by participants in classrooms, and the environmental settings and some of the items being asked in the questionnaire were quite sensitive; hence, participants might not have reported the real situation, which might have affected research findings.

Fifth, other stakeholders’ points of view would be useful. In the current study, the researchers only focused on adolescents concerning their perspectives on parenting and the RPII, and the frequencies of bullying and victimization of cyberbullying were both self-reported. The views of parents were not included; the findings were derived from questionnaires completed by children and not their parents. Self-reporting bias may lead to social desirability, memory limitations, misrepresentation, selectivity, unreliability, and a misunderstanding of questions. To address these limitations, future studies could improve parents and their understanding of, and familiarity with, the internet using digital technology by investigating how digital technology integrates into family life and further promotes parental mediation and parenting strategies. In addition, based on the findings, sampling, and focus of the current study, researchers can also further conduct focus groups or in-depth interviews with school teachers in order to expand the knowledge and handling of cyberbullying with regard to adolescents at school.

Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the current study risks overlooking the temporal sequence and dimension in cause-and-effect relationships. A longitudinal study could be conducted to address causality and to detect any changes that might occur over a period of time in the field of cyberbullying behaviors and adolescents’ well-being for future studies.

13. Conclusions

This study aims to update the understanding of cyberbullying processes in Chinese society and offer insights into mental health and well-being among adolescents in Macau. It highlights important cultural differences in how parenting styles and the RPII strategies may function in relation to adolescent cyberbullying behaviors, which is a significant contribution to the literature. This study underlines that fathers’ authoritative and permissive parenting styles were positively associated with adolescents’ experiences of cyberbullying, both as perpetrators and victims. Mothers’ authoritative style was significantly associated with increased cyber-victimization. In particular, when mothers used an authoritative style and also applied restrictive internet intervention strategies, adolescents reported higher levels of cyber-victimization. The findings have the potential to inform education and help professionals and policymakers in developing targeted interventions and in considering gender-sensitive approaches when designing family support programs. These support systems are aimed at improving the well-being of adolescents and their family members in the digital age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.H.; Methodology, S.-W.L. and K.L.H.; Formal analysis, K.L.H. and S.-W.L.; Investigation, S.-W.L.; Resources, S.-W.L.; Data curation, S.-W.L.; Writing—original draft, S.-W.L. and K.L.H.; Visualization, S.-W.L.; Supervision, S.-W.L.; Project administration, S.-W.L.; Funding acquisition, S.-W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Macau Foundation [Project number: MF/2022/ACA/04].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University Research Ethics Committee (protocol code 1-3-1-23 and 19 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request form the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baumrind, D. Rearing competent children. In Child Development Today and Tomorrow; Damon, W., Ed.; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 349–378. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J. Early Adolesc. 1991, 11, 56–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among junior and senior high school students in Guangzhou, China. Inj. Prev. 2019, 25, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.C.; Wong, D.S.W. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying in Chinese societies: Prevalence and a review of the whole-school intervention approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, R.; Smith, P.K. Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scand. J. Psychol. 2008, 49, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Marées, N.; Petermann, F. Cyberbullying: An increasing challenge for schools. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2012, 33, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A.P.; Lokhande, A.P.; Ekambaram, V.; Deshpande, S.N.; Ostermeyer, B. Cyberbullying: An Unceasing Threat in Today’s Digitalized World. Psychiatr. Ann. 2018, 48, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Navarro, R. Parenting Styles and Self-Esteem in Adolescent Cybervictims and Cyberaggressors: Self-Esteem as a Mediator Variable. Children 2022, 9, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.S.W.; Chan, H.C.; Cheng, C.H.K. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 36, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Association of Chinese Students of Macau; Macau Youth Research Association. Research Report on the Current Situation of Cyberbullying among Students in Macau. 2020. Available online: https://www.myra.org.mo/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/澳門學生網絡欺凌的現况調查研究報告.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024). (In Chinese).

- Message from Ms Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of UNESCO. 4 November 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379613 (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Social Welfare Bureau Government of the MSAR. Study on the Current Situation and Causes of Internet Addiction Among Youth in Macau SAR. 2012. Available online: https://www.ias.gov.mo/uploads/wp-content/themes/ias/tw/stat/download/AdolescentInternetAddictResearchReport_20130125.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2024). (In Chinese)

- Bowes, L.; Arseneault, L.; Maughan, B.; Taylor, A.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E. School, Neighborhood, and Family Factors Are Associated with Children’s Bullying Involvement: A Nationally Representative Longitudinal Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehue, F.; Bolman, C.; Völlink, T. Cyberbullying and traditional bullying in relation with adolescents’ perception of parenting. J. Cyber Ther. Rehabil. 2012, 5, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Elsaesser, C.; Russell, B.; Ohannessian, C.M.; Patton, D. Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 35, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Y.; Alink, L.R.A.; Tseng, W.-L.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Crick, N.R. Maternal and paternal parenting styles associated with relational aggression in children and adolescents: A conceptual analysis and meta-analytic review. Dev. Rev. 2011, 31, 240–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C.M. Bullying and Victimization in Early Adolescence: Associations with Attachment Style and Perceived Parenting. J. Sch. Violence 2013, 12, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, D.M.; Shapka, J.D.; Olson, B.F. To control or not to control? Parenting behaviors and adolescent online aggression. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.S.; Wong, Y.M. Cyber-Bullying Among University Students: An Empirical Investigation from the Social Cognitive Perspective. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 2013, 8, 34–69. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, X.; Chui, W.; Liu, L. Bullying Behaviors among Macanese Adolescents—Association with Psychosocial Variables. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.S.; Choi, T.Y. A comprehensive study of school bullying in Macau: Implications to strategies for promoting school harmony. In Proceedings of the Conference on Juvenile Delinquency: Phenomenon and Theories, Macau, China, 17–20 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ali Hamiza Wan, W.N.; Mohd, M.; Fauzi, F. Cyberbullying Detection: An Overview. In Proceedings of the 2018 Cyber Resilience Conference (CRC), Putrajaya, Malaysia, 13–15 November 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A. Individual psychology. In Psychologies of 1930; Murchison, C., Ed.; Clark University Press: Worcester, MA, USA, 1930; pp. 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Candelanza, A.; Queenilyn, E.; Buot, C.; Merin, J. Diana Baumrind’s parenting style and child’s academic performance: A tie-in. Psychol. Educ. J. 2021, 58, 1553–6939. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet. Psychol. Monogr. 1967, 75, 43–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. IV: Socialization, Personality and Social Development, 4th ed.; Hetherington, E.M., Mussen, P.H., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Stack, D.M.; Serbin, L.A.; Enns, L.N.; Ruttle, P.L.; Barrieau, L. Parental effects on children’s emotional development over time and across generations. Infants Young Child 2010, 23, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, K.; Demetriou, C.; Tricha, L.; Ioannou, M.; Georgiou, S.; Nikiforou, M.; Stavrinides, P. The effect of parental style on bullying and cyber bullying behaviors and the mediating role of peer attachment relationships: A longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. 2018, 64, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makri-Botsari, E.; Karagianni, G. Cyberbullying in Greek Adolescents: The Role of Parents. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 3241–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C. Understanding Cyberbullying in Upper Elementary School Students (Publication No. 13900510). Doctoral Dissertation, Northcentral University, La Jolla, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno–Ruiz, D.; Martínez–Ferrer, B.; García–Bacete, F. Parenting styles, cyberaggression, and cyber-victimization among adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I. Parenting in the digital era: Protective and risk parenting styles for traditional bullying and cyberbullying victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaç, B.; Aydoğan, D. Parental Attitudes as a Predictor of Cyber Bullying among Primary School Children. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2010, 4, 1667–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broll, R.; Reynolds, D. Parental Responsibility, Blameworthiness, and Bullying: Parenting Style and Adolescents’ Experiences with Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2021, 32, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, Y. Systematic review of the differences between mothers and fathers in parenting styles and practices. Curr. Psychol. J. Divers. Perspect. Divers. Psychol. Issues 2020, 42, 16011–16024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.J.; Salas, M.D.; Bernedo, I.M.; García-Martín, M.A. Impact of the parenting style of foster parents on the behaviour problems of foster children. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.; Tseng, V. Parenting of Asians. In Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 4. Social Conditions and Applied Parenting; Bornstein, M., Ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Watabe, A.; Hibbard, D.R. The influence of authoritarian and authoritative parenting on children’s academic achievement motivation: A comparison between the United States and Japan. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2014, 16, 359–382. [Google Scholar]

- Safaria, T.; Ariani, I.H. The Role of Self-Control, Authoritarian Parenting Style, and Cyberbullying Behaviour Among Junior High School Students. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2025, 10, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Farver, J.M.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, L.; Cai, B. Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent-child interaction. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005, 29, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K. The Parenting of Immigrant Chinese and European American Mothers. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Helsper, E. Parental Mediation of Children’s Internet Use. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2008, 52, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.C.; Chiu, C.H.; Miao, N.F.; Chen, P.H.; Lee, C.M.; Chiang, J.T.; Pan, Y.C. The relationship between parental mediation and Internet addiction among adolescents, and the association with cyberbullying and depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 57, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Krcmar, M.; Peeters, A.L.; Marseille, N.M. Developing a scale to assess three styles of television mediation: “Instructive mediation,” “restrictive mediation,” and “social coviewing”. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 1999, 43, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, R. Parental Mediation of Children’s Television Viewing in Low-Income Families. J. Commun. 2005, 55, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, D.; Knop, K.; Schmitt, S.; Vorderer, P. Rules? Role model? Relationship? The impact of parents on their children’s problematic mobile phone involvement. Media Psychol. 2019, 22, 82–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, R.; Aloia, L. Parenting Style, Parental Stress, and Mediation of Children’s Media Use. West. J. Commun. 2019, 83, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, G.; Paradeisioti, A.; Hadjimarcou, M.; Mappouras, G.; Kalakouta, O.; Avagianou, P. Cyberbullying In Cyprus—Associated Parenting Style and Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Cybertherapy Telemed. 2013, 191, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. Parental restrictive mediation of children’s internet use: Effective for what and for whom? New Media Soc. 2012, 15, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, A.; Chen, Y.A. Parental Internet practices in the family system: Restrictive mediation, problematic Internet use, and adolescents’ age-related variations in perceptions of parent-child relationship quality. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2024, 41, 1347–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. The Buffering Effect of Parental Mediation in the Relationship between Adolescents’ Cyberbullying Victimizations and Adjustment Difficulties. Child Abus. Rev. 2016, 25, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, P.; Singh, R. Parental regulation of internet use: Issues of control, censorship and cyberbullying. Mousaion S. Afr. J. Inf. Stud. 2016, 34, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniel-Nissim, M.; Efrati, Y.; Dolev-Cohen, M. Parental Mediation Regarding Children’s Pornography Exposure: The Role of Parenting Style, Protection Motivation and Gender. J. Sex Res. 2019, 57, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciacca, B.; Laffan, D.A.; Norman, J.O.H.; Milosevic, T. Parental mediation in pandemic: Predictors and relationship with children’s digital skills and time spent online in Ireland. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.R.B. Sensitive educational research in small states and territories: The case of Macau. Compare 2006, 36, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, Ç.; Erdur-Baker, Ö. The Revised Cyber Bullying Inventory (RCBI): Validity and reliability studies. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.W.; Fan, C.Y. Revision of the Revised Cyber Bullying Inventory among Junior High School Students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 6, 1031–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, G. Cyberbullying victimization and problematic Internet use among Chinese adolescents: Longitudinal mediation through mindfulness and depression. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 26, 2822–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K.H.; Cheng, S.P. Parenting, children’s empathy and compliance, and filial types. In Proceedings of the 113th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association (APA), Washington, DC, USA, 18–21 August 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Yeh, K. The Effect of Perceived Parenting Styles on Adolescents’ Dual Filial Belief: A Mediational Analysis. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 2013, 39, 119–164. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.; Chen, H.J. Relationships Between Parental Internet Intervention, School Engagement, and Risky Online Behaviors Among Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Family Cohesion. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 61, 205–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D.; Posavac, S.S.; Kardes, F.R.; Schneider, M.J.; Popovich, D.L. Toward a more nuanced understanding of the statistical properties of a median split. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Zhang, S.; Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macau Catholic Family Advisory Council. The Needs of Different Stages of Marriage and Family Life Course in Macau; University of Saint Joseph: Macau, China, 2021; Available online: https://online.fliphtml5.com/dpzbn/enxf/#p=1 (accessed on 27 June 2024). (In Chinese)

- Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Tang, H. The interactive effects of parental mediation strategies in preventing cyberbullying on social media. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.; Ismail, N. Exploring the role of parents and peers in young adolescents’ risk taking on social networking sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, C.P. Parenting in the digital age: Between socio-biological and socio-technological development. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Welfare Bureau Government of The MSAR. The State of Women in Macau 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.camc.gov.mo/cam/wr_2022_cn.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2024). (In Chinese)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).