Abstract

Background: The recently defined pachychoroid disease spectrum (PDS), which includes central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR), is a group of retinal disorders that share the common characteristic of a thick, dilated, hyperpermeable choroid. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of difluprednate and loratadine in the treatment of pachychoroid disease spectrum (PDS). Methods: A retrospective study of 27 eyes from 19 patients with macular edema secondary to chronic PDS were treated with topical difluprednate and oral loratadine at a tertiary medical center. Visual acuity and optical coherence tomography (OCT) images were analyzed at baseline, 1-, 2-, 3-, 6-, 12-month, and final follow-up. Baseline was defined as the initiation of topical difluprednate. Patients with neovascularization or who had other concurrent treatments for PDS were excluded. Subfoveal choroidal thickness was measured at each time point. Response was defined as eyes that showed a reduction in intra- or subretinal fluid. Results: All 27 eyes studied responded to treatment. Of these, 70.4% resolved by 4 months and 81.5% by 6 months, with 52.2% of these patients having recurrences related to cessation or tapering of topical steroids. Visual acuity remained stable (p > 0.05) while subfoveal choroidal thickness decreased compared to baseline (p < 0.001) across all time points. Eleven (40.7%) of the eyes developed increased intraocular pressure, for which seven (25.9%) required incisional surgery. Conclusions: Chronic PDS can be treated with a combination of topical difluprednate and oral antihistamines to reduce retinal edema and subfoveal choroidal thickness. The effectiveness of therapy could be linked to the regulation of mast cell degranulation, necessitating a well-powered prospective randomized clinical trial.

1. Introduction

The recently defined pachychoroid disease spectrum (PDS), which includes central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR), is a group of retinal disorders that share the common characteristic of a thick, dilated, hyperpermeable choroid [1,2]. These disorders are typically associated with serous macular and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) detachments and can develop macular neovascularization (MNV) [2]. While significant evidence links endogenous and exogenous steroids to an increased risk of these disorders, the exact underlying etiology and pathogenesis of PDS spectrum are still unclear [1,3]. Although many treatments exist, these patients remain challenging to treat [4]. A review of 31 studies by the American Academy of Ophthalmology where the efficacy of several therapeutic modalities for the treatment of CSCR was assessed found that photodynamic therapy (PDT), intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections and oral beta blockers, have shown inconsistent benefits for patients with chronic CSCR [4].

Mast cells, known to release histamine in allergic diseases, have been implicated as a potential pathophysiological mechanism for the development of PDS [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Mast cells have been shown to aggregate within the posterior choroid, and their activation can induce choroidal thickening and hyperpermeability [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Specifically, chemical induction of mast cell degranulation in rats produces choroidal thickening and serous retinal detachments [11]. In addition, inhibition of mast cell degranulation prevents the development of serous retinal detachments [11]. Combined modulation of mast cell activation may be a therapeutic target for PDS that has been previously proposed but not formally evaluated in patients.

In mast-cell-specific diseases or chronic allergic diseases, the cornerstone of therapy involves the combined use of steroids and antihistamines [12]. In mast cell activation syndromes, these cells release anaphylaxis mediators, producing inflammatory and vasoactive substances that cause tissue-specific symptoms such as urticaria, allergic rhinitis, or wheezing. Patients are advised to avoid triggers of mast cell activation proactively and are initiated on first- or second-generation type 1 histamine receptor blockers [13]. In cases marked by severity or resistance to conventional measures, the inclusion of glucocorticoids or immunomodulatory therapies, such as omalizumab, is necessary [13].

Although systemic steroids have been implicated in the pathogenesis of PDS, topical steroids have been shown to be associated with but not causative of disease activation [14,15]. In two large claim database studies from Taiwan, patients with CSCR more frequently, recently, and persistently used topical ophthalmic corticosteroids [14,15]. However, these studies do not prove that topical steroids cause PDS flares. In fact, there is evidence that supports the use of topical steroids to treat these patients [2,16]. Difluprednate, to our knowledge, has not been studied for the treatment of PDS. In this study, we evaluate the use of topical difluprednate with oral antihistamines in the treatment of chronic PDS.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles, adhered to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent requirement was waived given the limited protected health information used and the no more than minimal risk to participants. Patients were evaluated and treated at a single tertiary medical center. Patients were included if they were diagnosed with chronic pachychoroid disease spectrum (e.g., CSCR, peripapillary pachychoroid disease, etc.) and were treated with a combination of topical difluprednate either three or four times a day and a daily oral antihistamine (loratadine). Patients were excluded if treated only with either topical or oral antihistamine or with difluprednate and a topical antihistamine. The tapering protocol involved reducing the dosing frequency every two weeks, from four times daily to three, twice, and once daily, followed by administration every other day, every two days, every three days, and then discontinuation. Eyes with macular neovascularization were excluded. Patients with concurrent alternative treatments, such as anti-VEGF injections or photodynamic therapy (PDT), were also excluded. A diagnosis of chronicity was considered if the patient sustained 3 months of symptom onset without improvement, confirmed on OCT.

Patient demographic and systemic clinical information was collected including age, initial diagnosis of pachychoroid disease spectrum, body mass index, steroid use, comorbid obstructive sleep apnea, diabetes mellitus, presence of stressors, allergies, prior treatment with photodynamic therapy (PDT), prior treatment with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF), and development of elevated intraocular pressure. The date of initiation and cessation of difluprednate and loratadine was recorded. Baseline was defined as the initiation of difluprednate.

OCT B-scans at baseline were analyzed for the presence of subretinal and intraretinal fluid in relationship to the nerve (peripapillary) or the fovea (diffuse, subfoveal, or parafoveal). Response to treatment was defined as eyes that showed a reduction in intraretinal or subretinal fluid at the three-month follow-up. Resolution was defined as the absence of intraretinal or subretinal fluid at any time point after 3 months. Recurrence was deemed as the presence of any intraretinal or subretinal fluid after fluid had previously resolved at any time point. Subfoveal choroidal thickness (SFCT), defined as the distance from the inner choriocapillaris to the scleral-choroidal junction, was measured using the Heidelberg Explorer (Version 1.6.2, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) calipers if the scleral-choroidal junction was visible.

Categorical variables (e.g., history of obstructive sleep apnea) were recorded as numerical counts with percentages of totals, while continuous variables were presented as averages with standard deviation (e.g., logMAR vision). Demographics and risk factors were compared between groups using either linear (for continuous variables) or logistic (for categorical variables) regression models with mixed effects to control for bilateral enrollment across different groups. Paired t-test was used to compare the baseline and follow-up visual acuity and SFCT. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed on Microsoft Excel (Version 16.104, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results

A total of 27 eyes from 19 patients received treatment with a combination of oral antihistamine and topical difluprednate. Eight patients had bilateral disease. Patients’ demographics and risk factors are summarized in Table 1. The cohort had an average age of 64.3 ± 13.1 years, was predominantly male (89%), and had an average body mass index of 26.7 ± 4.7. The average duration of disease prior to difluprednate and loratadine treatment was 36.5 ± 44.5 months from the onset of symptoms (range 0 months to 11.5 years). Patients with prior treatment with anti-VEGF or PDT had a mean of 18.5 ± 27.3 months prior to the last treatment (range 1 month to 7 years). No other anti-VEGF or PDT treatment was performed while topical difluprednate was administered. There was a mean follow-up from the initiation of treatment of 20.2 ± 10.8 months (range 3 to 34.6 months). The small number of subjects with OSA (n = 5) limited our ability to perform a meaningful subgroup analysis.

Table 1.

Demographics and risk factors of PDS patients at presentation.

The detailed treatment history of each patient is presented in Table 2. Of the 27 eyes from 19 patients studied, all responded to treatment with a combination of oral loratadine and topical difluprednate. Nineteen of the eyes (70.4%) resolved by 4 months, twenty-two (81.5%) by 6 months, and twenty-three of the eyes (85.2%) were noted to have complete resolution of intra- or sub-retinal fluid at follow-up.

Table 2.

Treatment outcomes.

The mean time to improvement was 1.9 ± 2.7 months (median 1.1, range 0.5–13.3 months) and the mean time to resolution was 2.9 ± 1.6 months (median 3.0, range 0.6–6.5 months). Of the 23 eyes that had complete resolution, 12 eyes (52.2%) had recurrences of fluid and were all associated with tapering or cessation of topical difluprednate (Figure 1). None required rescue treatment of anti-VEGF or PDT. Of the 11 eyes without recurrence, 3 eyes (27.2%) have been completely off difluprednate and are only on antihistamines (median of 28.5-month follow-up, range 1.4–29.9 months). Mean duration of difluprednate for all eyes was 17.1 ± 9.7 months (median 18.4, range 3.0–34.6 months).

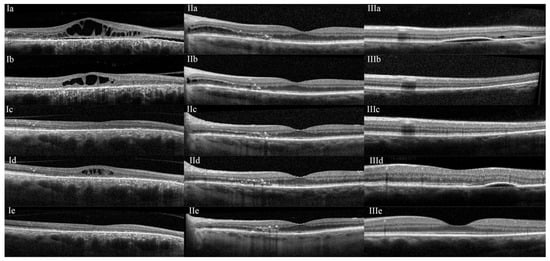

Figure 1.

(I): A 60-year-old patient (patient #7 OD) with a history of a sudden decline in vision with a central scotoma in the right eye two years prior. Initial ocular coherence tomography (OCT) showed retinal pigment epithelium changes, outer retinal atrophy, subretinal fluid extending from the disk to the fovea, and cystoid macular edema (Ia) consistent with a diagnosis of pachychoroid disease spectrum (PDS). Treatment with topical difluprednate (4 times a day) and oral loratadine (10 mg twice a day) was started, and the patient showed improvement in 1.5 months (Ib). By 3.5 months, all retinal fluid had resolved (Ic). During the tapering of difluprednate (to once every other day, loratadine was maintained), there was a recurrence of cystoid macular edema (Id). The difluprednate dose was increased to twice daily, and the fluid resolved once again (Ie). (II): A 78-year-old male (patient #10 OS) with a longstanding (>3 years) history of PDS was started on topical difluprednate and oral loratadine (IIa). At 1-month follow-up, OCT showed significant improvement in intraretinal and subretinal fluid (IIb). The patient remained stable at the 2-month (IIc), 1-year (IId), and 4-year (IIe) follow-ups while following a very slow taper of difluprednate. (III): A 46-year-old patient (patient #1 OS) with a history of obstructive sleep apnea and PDS was started on topical difluprednate (4 times a day) and oral loratadine (IIIa). The subretinal fluid resolved by 2 months, and the pigment epithelial detachment improved dramatically (IIIb) and was stable at future follow-ups (IIIc: 5-month). The patient had a mild recurrence of subretinal fluid at another location, which did not require restarting treatment (IIId: 1-year, and IIIe: 2-year).

Baseline visual acuity across all patients was 0.3 ± 0.3 (20/40). Visual acuity remained grossly stable across all follow-up visits (p > 0.05) with a final visual acuity of 0.3 ± 0.4 (20/40, p = 0.83). Of the 27 eyes, 22 eyes had measurable subfoveal choroidal thickness at baseline with a mean SFCT of 317.4 ± 90.9 µm. This significantly improved to 290.8 ± 105 at month 1 (p < 0.05) and remained decreased at all subsequent time points (p < 0.05). Continued decrease in SFCT was noted at final follow-up across all measurable patients with a final average SFCT of 263.2 ± 86.6 µm (p < 0.001).

Table 3 summarizes the intraocular pressure changes. Four eyes (14.8%) had pre-existing glaucoma and two eyes had pseudoexfoliation syndrome without glaucoma (7.4%). The mean baseline intraocular pressure (IOP) was 16.4 ± 3.4 mmHg, and the mean final IOP was 14.7 ± 4.3 mmHg. Medical therapy was the primary management approach in 26 eyes (81%), most commonly including dorzolamide (74%), timolol (63%), brimonidine (32%), prostaglandin analogs (26%), and rhopressa (61%). Surgical or laser interventions were performed in 7 eyes (25.9%), including minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS; 5 eyes, 18.5%), and selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT; 2 eyes, 7.4%). Supplemental Table S1 demonstrates that glaucoma-related structural OCT metrics (CTD, PSD, MSD) remained largely stable throughout treatment, with no consistent pattern of progressive glaucomatous change despite transient IOP elevations.

Table 3.

Intraocular pressure differences with treatment.

4. Discussion

In this cohort, we found that the use of topical difluprednate in combination with oral loratadine did not cause recurrence or progression of fluid and can effectively treat fluid in PDS patients without MNV. Retinal fluid showed improvement within the first month and resolved completely within three months in most eyes. These positive outcomes were accompanied by stable visual acuity and a decrease in subfoveal choroidal thickness. However, several patients also reported subjective improvement in metamorphopsia—an outcome not captured by standard acuity metrics. Future studies should incorporate more sensitive assessments of visual function, such as microperimetry or multifocal electroretinography (mfERG), to better characterize functional changes associated with anatomical improvement. The time frame of fluid resolution is similar to previously described treatment outcomes with successful PDT [17,18,19]. Notably, the recurrence of fluid associated with the tapering or cessation of treatment was observed in several patients.

The use of topical steroids can be counterintuitive in the setting of the established risk associated with systemic steroids in the development of PDS. Multiple studies have demonstrated that patients who use oral, intranasal, inhaled, and, to a lesser extent, topical (e.g., dermal or ophthalmic) steroids are associated with a greater risk of developing serous macular detachments in CSCR. In fact, one large case–control study showed that patients with CSCR were 6.3 times more likely to use topical corticosteroids compared to an age -, sex -, and geographic-matched control group in Taiwan [14]. However, by design, these studies prove association but not causation.

Steroids have previously been shown to be effective in treating PDS. In a study that used topical dexamethasone as an adjuvant to mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism, 80% of patients responded to treatment, 50% resolving completely [16]. There was no significant change in visual acuity for these patients [16]. In a study by van den Tillart, 54 eyes from 58 patients with PDS were treated with topical prednisolone [2]. This resulted in a decreased macular volume (due to decreased sub- or intra-retinal fluid) in 68% of their patients. Of note, there was also no significant change in these patients’ visual acuity [2]. A review by Adriono evaluated nine studies involving triamcinolone and dexamethasone in the treatment of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, a subclassification of PDS [20]. Of these, only two of the studies reported significantly improved visual acuity; however, several reported significant improvement in central foveal thickness and central retinal thickness [20]. In a case report of CSCR treated with intravitreal triamcinolone, there was no progression or resolution of chronic subretinal fluid [21]. The precise mechanism for why differing steroids, administration routes, and doses can have varying effects on PDS remains unclear. One possible explanation is that steroids are known to suppress the number of mast cells and, when tapered, can allow mast cells to repopulate, allowing for recurrence [22,23]. This explains the rationale behind using an antihistamine to chronically inhibit mast cells.

Recurrence after tapering steroids in our study suggests that steroids are the primary driver of fluid control in PDS. Loratadine was used with the goal of stabilizing mast cells after steroid-induced suppression, but the lack of sustained effect may point to insufficient mast cell inhibition. This highlights the need to explore other mast cell–targeted therapies, such as alternative antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, leukotriene inhibitors, or biologics. Additionally, while steroids can help preserve the outer retina by reducing fluid, their use carries the risk of optic nerve damage from elevated intraocular pressure. This trade-off must be carefully considered when deciding between prolonged steroid therapy and the need for pressure-lowering interventions, whether medical or surgical.

Although the exact etiology of PDS remains elusive, choroidal inflammation may play a role in the underlying mechanism of the disease [24]. Genome-wide association studies conducted in European and Japanese CSCR cohorts have consistently identified complement factor H (CFH) as a contributory pathway [25,26,27,28]. The gene CFH has also been associated with age-related macular degeneration, indicating a potential overlap between the two diseases, which can often present similarly [25,29]. Other genes involved in mast cell biology, such as GATA5, TNFRSF10A, VIPR2, have also been identified in various CSCR populations [27,28,30,31,32]. Of note, mast cells have been reported to contribute to metabolic dysregulation leading to obesity which although it has not been directly correlated with PDS, it is associated with OSA, a known risk factor for PDS [33]. This potential association requires further study. Two separate studies of human donor eyes with AMD found increased degranulated mast cells in all choroidal areas of early and advanced AMD compared to age-matched controls [34]. Bousquets et al. demonstrated that mast cell degranulation can induce serous choroidal detachments and choroidal thickening, while inhibition of mast cell degranulation prevented these pathological changes [11]. This was further supported by in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrating that exogenous histamine recruits uveal leukocytes [10]. Additionally, allergic respiratory disease and the use of an anti-histamine were independently found to be associated with the development of CSCR [1]. Our study provides further support for the suppression of mast cell function within the choroid through steroids and antihistamines as a novel therapeutic pathway in the management of PDS.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective, non-controlled, and non-randomized nature. Although all patients were diagnosed with chronic CSCR or PDS, their duration of disease varied, ranging from patients who were treatment-naïve to those with a history of multiple anti-VEGF or PDT treatments. Because PDS comprises a spectrum of diseases, the therapeutic effect may differ across subtypes. Specifically, each drug effect may vary and the relative efficacy of difluprednate versus loratadine was not assessed. Importantly, while we collected systemic factors—including BMI and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)—the cohort was underpowered to evaluate their associations with treatment response or safety outcomes. Future studies should stratify by OSA status and BMI and adjust for these covariates in multivariable models. Finally, CSCR/PDS can wax and wane with spontaneous fluid resolution; however, most patients here had chronic symptoms and prior unsuccessful therapies. Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings support a potential additional treatment option for PDS that warrants prospective evaluation. The independent role of antihistamines—particularly in reducing recurrence risk after steroid discontinuation—remains to be determined in controlled trials. Given its retrospective and exploratory nature, this study should be considered a pilot investigation aimed at informing the design of future prospective, controlled trials.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we show that the combination of topical difluprednate and oral loratadine can reduce retinal fluid and subfoveal choroidal thickness in patients with PDS, without worsening visual acuity. These findings suggest that targeting choroidal inflammation and mast cell activity may play a meaningful role in managing PDS. While the data are preliminary and drawn from a retrospective cohort, the consistent anatomical improvements observed support further investigation of this approach. Future prospective studies are needed to clarify the independent contributions of steroids and antihistamines, determine optimal dosing strategies, and assess long-term outcomes. This combined therapy may represent a promising treatment approach to the current therapeutic landscape for PDS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcto4010002/s1, Table S1: Glaucoma-related structural outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.G., J.A. and A.A.; methodology, M.B.G., J.A. and A.A.; formal analysis, E.R.V.-F. and A.A.; investigation, E.R.V.-F., J.A. and A.A.; data curation, A.A. and E.R.V.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A., E.R.V.-F., J.A. and M.B.G.; supervision, M.B.G.; project administration, M.B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of UCLA (approval on 27 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent requirement was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, and given the no more than minimal risk to participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Haimovici, R.; Koh, S.; Gagnon, D.R.; Lehrfeld, T.; Wellik, S. Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: A case-control study. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Tillaart, F.M.; Temmerman, I.M.; Hartgers, F.; Yzer, S. Prednisolone Eye Drops as a Potential Treatment in Nonneovascular Pachychoroid-Related Diseases. Retina 2024, 44, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho-Recchia, C.A.; Yannuzzi, L.A.; Negrão, S.; Spaide, R.F.; Freund, K.B.; Rodriguez-Coleman, H.; Lenharo, M.; Iida, T. Corticosteroids and central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 1834–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.A.; Maguire, M.G.; Weng, C.Y.; Smith, J.R.; Jain, N.; Flaxel, C.J.; Patel, S.; Kim, S.J.; Yeh, S. Therapies for Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilstrup, G. Studies on the vascular capacity and tissue fluid content of the choroid and their variations under treatment with histamine. Acta Ophthalmol. 1952, 30, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, G. An autoradiographic study on the uptake of S35-labeled sodium sulfate; in the eyes of normal, scorbutic, and hormonal treated guinea pigs. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1959, 47, 519–529; discussion 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.; Cunha-Vaz, J.G. Effect of Histamine on the Permeability of the Ocular Vessels. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1965, 73, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.S.; Trokel, S. Effects of mast-cell degranulation on the choroid. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1966, 75, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, W.A. Characterization of the choroidal mast cell. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1987, 85, 557–599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schlaegel, T.F., Jr. Histamine and uveal infiltration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1949, 32, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, E.; Zhao, M.; Thillaye-Goldenberg, B.; Lorena, V.; Castaneda, B.; Naud, M.C.; Bergin, C.; Besson-Lescure, B.; Behar-Cohen, F.; de Kozak, Y. Choroidal mast cells in retinal pathology: A potential target for intervention. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 2083–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akin, C. Mast cell activation syndromes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabato, V.; Beyens, M.; Toscano, A.; Van Gasse, A.; Ebo, D.G. Mast Cell-Targeting Therapies in Mast Cell Activation Syndromes. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2024, 24, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Weng, S.F.; Chang, C.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, J.Y.; Jan, R.L. Associations Between Topical Ophthalmic Corticosteroids and Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: A Taiwanese Population-Based Study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 4083–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Weng, S.F.; Wang, J.J.; Jan, R.L. Temporal Association between Topical Ophthalmic Corticosteroid and the Risk of Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Zhu, D.; Li, A.S.; Lee, J.G.; Ferrone, P.J. Topical Dexamethasone as an Adjuvant to Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Recalcitrant Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2022, 53, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.H.; Heo, J.; Kim, C.; Kim, T.W.; Shin, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Song, S.J.; Park, T.K.; Moon, S.W.; Chung, H. Low-fluence photodynamic therapy versus ranibizumab for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: One-year results of a randomized trial. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E.H.C.; Fauser, S.; Breukink, M.B.; Blanco-Garavito, R.; Groenewoud, J.M.M.; Keunen, J.E.E.; Peters, P.J.H.; Dijkman, G.; Souied, E.H.; MacLaren, R.E. Half-Dose Photodynamic Therapy versus High-Density Subthreshold Micropulse Laser Treatment in Patients with Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: The PLACE Trial. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolo, M.; Eandi, C.M.; Alovisi, C.; Grignolo, F.M.; Traverso, C.E.; Musetti, D.; Cardillo Piccolino, F. Half-fluence versus half-dose photodynamic therapy in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 157, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriono, G.A.; Triyoga, I.F.; Kadharusman, M.M.; Victor, A.A.; Djatikusumo, A.; Yudantha, A.R.; Hutapea, M.M. Efficacy and Safety of Ophthalmic Steroids in the Management of Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy: A Systematic Review. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; Kamppeter, B.A. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide and central serous chorioretinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 386–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, P.; McGarity, B.; Walls, A.F.; Church, M.K.; Millward-Sadler, G.H.; Robertson, D.A. Corticosteroid treatment reduces mast cell numbers in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1990, 35, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvisi, M.G. Regulation of inflammatory cell function by corticosteroids. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2004, 1, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnegar, A.; Ong, J.; Matsyaraja, T.; Arora, S.; Chhablani, J. Pathomechanisms in central serous chorioretinopathy: A recent update. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2023, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, M.; Miyake, M.; Momozawa, Y.; Arakawa, S.; Maruyama-Inoue, M.; Endo, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Ishigaki, K.; Matoba, N.; Okada, Y. Genome-Wide Association Study of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Reveals 2 New Loci Implying Shared Genetic Components with Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology 2023, 130, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, A.; Kondo, N.; Yanagisawa, S.; Bessho, H.; Honda, S.; Negi, A. Common variants in the complement factor H gene confer genetic susceptibility to central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, Y.; Yoshikawa, M.; Miyake, M.; Tabara, Y.; Ahn, J.; Woo, S.J.; Honda, S.; Sakurada, Y.; Shiragami, C.; Nakanishi, H. CFH and VIPR2 as susceptibility loci in choroidal thickness and pachychoroid disease central serous chorioretinopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6261–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.K.; Breukink, M.B.; Schellevis, R.L.; Bakker, B.; Mohr, J.K.; Fauser, S.; Keunen, J.E.; Hoyng, C.B.; den Hollander, A.I.; Boon, C.J. Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy is associated with genetic variants implicated in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramo, J.T.; Abner, E.; van Dijk, E.H.C.; Wang, X.; Brinks, J.; Nikopensius, T.; Nõukas, M.; Marjonen, H.; Silander, K.; Jukarainen, S. Overlap of Genetic Loci for Central Serous Chorioretinopathy With Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023, 141, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zon, L.I.; Gurish, M.F.; Stevens, R.L.; Mather, C.; Reynolds, D.S.; Austen, K.F.; Orkin, S.H. GATA-binding transcription factors in mast cells regulate the promoter of the mast cell carboxypeptidase A gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 22948–22953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, J.D.; Elias, M.G.; Fereydouni, M.; Daniels-Wells, T.R.; Dellinger, A.L.; Penichet, M.L.; Kepley, C.L. Human Mast Cells From Adipose Tissue Target and Induce Apoptosis of Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado-Bedmar, M.; Heil, S.D.S.; Myrelid, P.; Söderholm, J.D.; Keita, Å.V. Upregulation of intestinal mucosal mast cells expressing VPAC1 in close proximity to vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in inflammatory bowel disease and murine colitis. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 31, e13503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Hu, C. Mast cell promotes obesity by activating microglia in hypothalamus. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1544213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, I.A.; McLeod, D.S.; Jing, T.; Sunness, J.S.; Seddon, J.M.; Lutty, G.A. Increased choroidal mast cells and their degranulation in age-related macular degeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 100, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.