Abstract

Background/Objectives: Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are widely used in type 2 diabetes mellitus for glycemic control and cardiovascular–renal protection, but adverse effects such as acute kidney injury (AKI), urinary tract infection (UTI), euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (Eu-DKA), and acute pancreatitis remain concerns. We aimed to determine the prevalence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use. Methods: This retrospective study assessed the prevalence of these adverse events and identified factors associated with UTI among SGLT2 inhibitor users at Suddhavej Hospital (1 January 2019–15 August 2023). Data were extracted from the hospital electronic medical record system (BMS-HOSxP). Results: We analyzed 293 patients (59.73% male; mean age 63.08 ± 0.667 years; 62.08% aged >60). Dapagliflozin had the highest prevalence of AKI (11.42%) and UTI (13.40%). No acute pancreatitis cases were reported. Logistic regression identified female sex (odds ratios [OR] 2.31, 95% confidence intervals [CI] 1.08–4.96; p = 0.032), AKI diagnosis (OR 3.31, 95% CI 1.10–9.89; p = 0.032), age ≥ 60 years (OR 2.78, 95% CI 1.09–7.09; p = 0.033), and SGLT2 inhibitor use <6 months (OR 5.78, 95% CI 2.74–14.18; p = 0.017) as significant risk factors for UTI. Conclusions: Dapagliflozin was associated with the highest prevalence of AKI and UTIs. Female sex, AKI diagnosis, age ≥ 60 years, and SGLT2 inhibitor use <6 months were significant risk factors for UTI among SGLT2 inhibitor users.

1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a metabolic disorder characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from either inadequate insulin secretion or impaired cellular response to insulin [1]. The long-term complications of diabetes, including cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, retinopathy, and peripheral neuropathy, substantially increase mortality and morbidity, particularly in older adults [2]. In 2021, diabetes directly caused >2 million deaths worldwide, and ~11% of cardiovascular deaths were associated with elevated blood glucose. Globally, the number of people living with diabetes rose from ~200 million in 1990 to 830 million in 2022, with prevalence increasing more rapidly in low- and middle-income countries [3].

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, including dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and canagliflozin, represent a class of antihyperglycemic agents recommended in the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines as adjunctive treatment options for patients with T2DM [4]. These agents offer multiple clinical benefits, including a reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), body weight [5], and blood pressure [6].

Evidence from two meta-analyses supports the efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors in improving glycemic control. These studies reported that SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced HbA1c levels by approximately 0.44–0.96% compared with that of placebo, either as monotherapy or in combination with other antidiabetic agents. Additionally, patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors experienced weight reductions of 1.6–2.8 kg. These agents also contributed to lowering blood pressure, significantly reducing systolic and diastolic blood pressure [7,8].

In addition to their clinical indications, it is essential to carefully evaluate the safety profiles of SGLT2 inhibitors. As a relatively new class of antidiabetic agents, first approved for clinical use in 2015 by both the ADA and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, SGLT2 inhibitors require continuous safety surveillance [4].

Post-marketing safety surveillance is a cornerstone of modern drug regulation because newly approved medicines require ongoing pharmacovigilance to detect rare or delayed adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in real-world use. Globally, the World Health Organization established the Program for International Drug Monitoring in 1968, providing an international framework for collecting, evaluating, and sharing drug safety data across member countries. Within this framework, national pharmacovigilance systems, including hospital-based monitoring programs, are essential for generating real-world safety evidence. Real-world studies and pharmacovigilance reports have linked sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors to adverse drug reactions such as acute kidney injury, urinary tract infections, euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis, and acute pancreatitis, although reported frequencies vary by region and healthcare setting. However, data from Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand, remain limited. Hospital-based pharmacovigilance can help address this gap by contextualizing global safety signals within local clinical practice and supporting safer, more rational use of SGLT2 inhibitors in real-world settings [9].

In Thailand, post-marketing safety surveillance of newly approved drugs is conducted through the Safety Monitoring Program (SMP) [10], a stimulated reporting system established in 1991 under the Thai Food and Drug Administration. During the conditional registration period (typically two years), newly approved drugs may be used only in public or private healthcare institutions under close medical supervision, with systematic safety monitoring by healthcare professionals and marketing authorization holders [11]. Full registration and wider distribution are granted only after sufficient post-marketing safety data have been accumulated [12].

Currently, Suddhavej Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Mahasarakham University, includes four SGLT2 inhibitors on its formulary. Three are single-agent formulations: canagliflozin 100 mg (Invokana®), dapagliflozin 10 mg (Forxiga®), and luzeogliflozin 5 mg (Lusefi®) tablets. The fourth is a fixed-dose combination of dapagliflozin 10 mg and metformin 1000 mg (Xigduo®). These aforementioned SGLT2 inhibitors have been removed from the SMP list [13]; however, the hospital continues to actively monitor their safety profiles within the SMP framework, reflecting ongoing surveillance for potential adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

Globally and locally, SGLT2 inhibitor use for managing T2DM has increased, driven by guideline recommendations and added benefits in specific populations, including patients with cardiovascular disease, renal impairment, and heart failure. However, recent reports have noted increasing numbers of ADRs associated with SGLT2 inhibitors, including acute kidney injury (AKI), acute pancreatitis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and euglycemic–diabetic ketoacidosis (Eu-DKA), a rare but serious complication characterized by metabolic acidosis with normal blood glucose levels. Notably, patients with T2DM receiving SGLT2 inhibitors have an approximately seven-fold higher risk of Eu-DKA, with an estimated overall incidence of ~0.1% [14].

Therefore, careful safety evaluation of SGLT2 inhibitor use is essential. Identifying and understanding the risk factors contributing to ADRs is critical to prevention. Moreover, providing appropriate education to both patients and healthcare providers is crucial for the early detection, prevention, and effective management of potential SGLT2 inhibitor-associated ADRs. Accordingly, in this study, we investigated the prevalence rate of ADR associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use, specifically AKI, acute pancreatitis, UTI, and Eu-DKA, and identified potential factors associated with UTI occurrence in patients treated with SGLT2 inhibitors.

2. Results

2.1. Participant Demographics

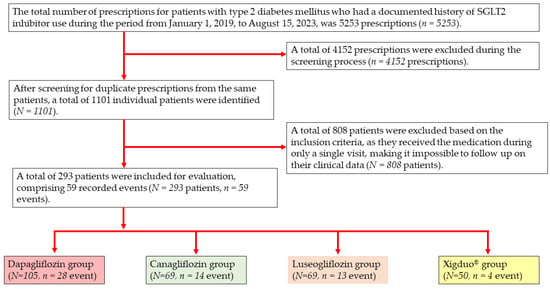

A total of 5253 prescriptions for SGLT2 inhibitors were identified among patients with T2DM between 1 January 2019, and 15 August 2023. After removing 4152 duplicate prescriptions, 1101 individual patients remained. Of these, 808 patients were excluded because they received the medication on only a single occasion, precluding follow-up. This left 293 patients for analysis, among whom 59 reported ADRs. The cohort comprised 105, 69, 69, and 50 patients in the dapagliflozin (28 events), canagliflozin (14 events), luseogliflozin (13 events), and fixed-dose dapagliflozin/metformin (Xigduo®) (four events) groups, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study sample selection flow diagram.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 293 patients included in this study. The majority were male (59.73%) and aged over 60 years (62.08%), with a mean age of 63.08 ± 0.667 years. Most patients (67.92%) had a glomerular filtration rate within stage 1 (mL/min/1.73 m2), with a mean SCr level of 1.057 ± 0.023 mg/dL. A high proportion (81.51%) had suboptimal glycemic control, defined as HbA1C ≥ 7%. The three most frequently prescribed medications were metformin (74.28%), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)/angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (53.31%), and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (51.15%). Most participants received SGLT2 inhibitors for diabetes mellitus (51.68%), followed by heart failure (36.91%). The largest proportion had used an SGLT2 inhibitor for 12 to <24 months (35.91%).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of included participants (n = 293).

When examining the prevalence of adverse events associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use, all agents in this class were associated with an increased risk of AKI. Dapagliflozin showed the highest prevalence (11.42%). UTIs were another notable adverse event, with the highest prevalence observed for dapagliflozin (13.40%), followed by canagliflozin (13.27%) and luseogliflozin (12.50%). Eu-DKA occurrence was relatively rare, with the highest rate reported for Xigduo® (2%). No cases of acute pancreatitis were identified. There were no statistically significant differences observed in the prevalence of acute kidney injury, euglycemic–diabetic ketoacidosis, or urinary tract infection among different SGLT2 inhibitor regimens (all p > 0.05). (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of adverse events associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use. (n = 293).

2.2. Univariate Analysis

The univariate regression analysis identified several factors significantly associated with the occurrence of ADRs (p < 0.05). Specifically, four factors were found to be significantly correlated with adverse events related to SGLT2 inhibitors: female sex (OR 2.52; 95% CI 1.78–5.01), age ≥ 60 years (OR 2.87; 95% CI 1.25–5.99), diagnosis of AKI (OR 3.42; 95% CI 1.88–7.64), concomitant insulin use (OR 1.79; 95% CI 0.66–4.02), and duration of SGLT2 inhibitor < 6 months (OR 1.87; 95% CI 1.58–4.64), as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with UIT related to SGLT2 inhibitor use (n = 298).

2.3. Logistic Regression Analysis

Univariate analysis of the ADR-associated factors revealed that only sex, AKI diagnosis, insulin use, and age met the criteria for further evaluation. Logistic regression analysis conducted to assess predictors of UTI prevalence revealed that female patients had a 2.27-fold higher risk than males did (95% CI 1.07–4.95; p = 0.031). Patients diagnosed with AKI had a 3.27-fold higher risk than those without AKI (95% CI 1.12–9.78; p = 0.033), and individuals aged ≥60 years had a 2.68-fold higher risk of developing UTIs than those aged <60 years (95% CI 1.07–7.01; p = 0.033). Additionally, SGLT2 inhibitor use for <6 months was associated with a 5.78-fold higher risk than use for ≥6 months (CI 2.74–14.18; p = 0.017) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with UTI among study subjects (n = 298).

3. Discussion

In a retrospective review of prescription records between 1 January 2019, and 15 August 2023, 894 prescriptions for SGLT2 inhibitors were identified. Among these, 190 were associated with ADRs, representing an overall prevalence rate of 20.14%. When categorized by type, the most frequently reported ADR was UTI (11.60%), followed by AKI (6.82%) and Eu-DKA (1.7%). No cases of acute pancreatitis were reported. Canagliflozin and dapagliflozin were associated with the highest number of ADRs, likely because of their earlier introduction into the hospital formulary than that of other agents in the class. Among the ADRs observed, UTIs were the most prevalent. Further analysis revealed that female sex and a concurrent AKI diagnosis were statistically significant factors for developing UTIs in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors. Dapagliflozin was the most frequently prescribed SGLT2 inhibitor, consistent with national and international guidelines and formulary availability. Consequently, more patients were exposed to dapagliflozin than to other agents in this class, which likely increased the absolute number and proportion of observed ADRs. Dapagliflozin is also often prescribed to older patients and those with multiple comorbidities, including cardiovascular and renal disease, who may have a higher baseline risk of adverse events such as AKI and UTIs.

The proportion of Eu-DKA in our study (1.7%) appears higher than the commonly cited global incidence of ~0.1% among SGLT2 inhibitor users. Several factors may explain this difference. First, we report the proportion of Eu-DKA cases within a hospital-based cohort of SGLT2 inhibitor users, not a population-based incidence rate per patient-year; thus, direct comparisons with global estimates from large pharmacovigilance databases or population-level studies may be inappropriate. Second, prior reports indicate that 2.6–3.2% of all DKA admissions are euglycemic, and SGLT2 inhibitor-associated DKA has been estimated at 0.16–0.76 events per 1000 patient-years in type 2 diabetes. Blau et al. [15] further estimated an approximately seven-fold higher DKA risk in SGLT2 inhibitor users versus non-users. These data suggest that although Eu-DKA is rare at the population level, it may be detected more often in clinical settings with greater awareness and targeted evaluation. Third, selection bias in a single-center, hospital-based study and strict diagnostic criteria (including biochemical confirmation of ketosis with normal or mildly elevated glucose) may have increased case detection. Additionally, hospitalized patients may represent a higher-risk group due to intercurrent illness or other DKA precipitants [16,17].

In the present study, the prevalence of Eu-DKA was 1.70%, most frequently associated with dapagliflozin. Supporting evidence comes from a systematic review and quantitative analysis by Dutta et al. (2022) [18], who examined Eu-DKA occurrence with respect to SGLT2 inhibitor use. They aimed to identify demographic and clinical risk factors, as well as trends associated with Eu-DKA, by systematically reviewing 47 published case reports involving 77 patients who developed Eu-DKA while receiving SGLT2 inhibitors. Surgery was the most commonly reported precipitation factor (15 of 77 cases). Among the SGLT2 inhibitors, canagliflozin was the most frequently implicated agent (34 of 77 cases), particularly when combined with metformin, accounting for 63.6% of cases. Pooled analysis revealed that patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors plus metformin had a 3.7-fold higher risk of developing Eu-DKA than those receiving other antidiabetic therapies.

Real-world pharmacovigilance data from Bhanushali et al. [19] associate SGLT2 inhibitors with several ADR, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), urinary tract infections (UTIs), euglycemic DKA (Eu-DKA), mycotic genital infections, lower-limb amputations, and hypotension. DKA was the most frequently reported event, followed by UTIs and amputations. Similarly, Yoosuf et al. [20] identified UTIs as a predominant adverse event among SGLT2 inhibitor users. Together, these international real-world data contextualize our findings and support the clinical importance of monitoring UTI risk in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors.

UTI risk was significantly higher in patients who developed AKI during SGLT2 inhibitor treatment than in those without AKI. This finding aligns with that of a study conducted by Wang (2024) [21], which reported a risk ratio of 0.78 (95% CI 0.71–0.84; p < 0.001), underscoring the clinical relevance of increased UTI risk. In our cohort, all SGLT2 inhibitors were associated with UTI development, with dapagliflozin showing the highest prevalence, followed by canagliflozin. Multivariate analysis revealed that female sex was significantly associated with a higher UTI risk than that of male sex. Additionally, older age was identified as a significant contributing factor. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies reporting an overall UTI incidence of 11.52% among SGLT2 inhibitor users, with dapagliflozin showing the strongest association. A meta-analysis by Vasilakou et al. (2013) [22] showed that UTI risk was significantly higher in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors than in those receiving placebo (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.03–1.74). Specifically, dapagliflozin was associated with an even greater increase in UTI risk (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.10–1.67). Similarly, Johnsson et al. (2013) [23] reported a 4.6% UTI incidence in a cohort of 3152 dapagliflozin-treated patients, with infections occurring more frequently in female patients. Conversely, Uitrakul et al. (2022) [24], in an observational study conducted to evaluate UTI incidence among patients with T2DM receiving SGLT2 inhibitors, specifically dapagliflozin and empagliflozin, compared with those not receiving this class of drugs, found a significantly higher UTI incidence in the SGLT2 inhibitor group (33.49%), compared with only 11.72% in the non-SGLT2 inhibitor group. Moreover, female sex and advanced age were significantly associated with an increased UTI risk (p < 0.001), emphasizing the need for targeted patient monitoring and risk mitigation strategies during SGLT2 inhibitor therapy. Our analysis demonstrated that the majority of UTI events developed within the first six months of SGLT2 inhibitor therapy. This aligns with evidence from earlier studies reporting that UTIs commonly emerge during the initial six-month period after treatment initiation, although a substantial proportion may still occur thereafter. Notably, previous findings indicated that the median time to UTI onset could extend toward one year, suggesting that the risk persists beyond early treatment [25]. These observations underscore the importance of continued monitoring and clinical judgment regarding the continuation of SGLT2 inhibitors beyond the early phase of therapy.

In the present study, no prevalence of acute pancreatitis was observed among patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors. However, Zhang et al. (2022) [26] investigated the prevalence of acute pancreatitis associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use, including canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin. Utilizing data from the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System [27], they analyzed post-marketing adverse events and identified potential risk factors for mortality associated with SGLT2 inhibitor-induced acute pancreatitis, revealing 76,872 reported cases of acute pancreatitis as adverse events, of which 757 were associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use. These included 317 canagliflozin-related events, 150 dapagliflozin-related, 287 empagliflozin-related, and three ertugliflozin-related. Acute pancreatitis incidence was higher in males (56.7%) than in females (43.3%), with a mean age of 56.2 years. Approximately 75% of cases occurred in individuals aged between 18 and 64 years. Among those with available data (n = 334 of 757), the average body weight was 95.8 kg. Notably, approximately 83% of the reported adverse events occurred within 6 months of initiating SGLT2 inhibitor therapy.

The use of real-world data is a key strength of our study, providing evidence that may help administrators and policymakers develop standardized protocols and improve awareness when initiating SGLT2 inhibitor therapy in patients with identifiable risk factors. However, this study has limitations. First, the retrospective design precluded causal inference and led to incomplete data capture. Second, identification of some ADRs relied on symptom assessment, physician judgment, and hospitalization-based laboratory parameters (e.g., for diagnosing AKI or Eu-DKA). Third, no amputation events were observed, which may reflect the low incidence of this outcome and our limited sample size and follow-up duration; the single-center design and modest sample size also reduce power to detect infrequent events, limiting generalizability. Larger studies with longer follow-up are needed to evaluate rare outcomes and confirm our findings, including inconsistencies reported in prior studies. Finally, the absence of uniform application of standardized causality assessment tools may affect the certainty of causal attribution between SGLT2 inhibitors and the observed adverse events

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Setting

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects at Mahasarakham University, Thailand (Approval No. 249-080/2567). We employed a retrospective observational design, utilizing data collected from patients with a documented history of receiving SGLT2 inhibitors at Suddhavej Hospital. Data were retrieved from the hospital’s electronic medical record system, BMS-HOSxP version 3 (Bangkok Medical Software Co., Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand), between 1 January 2019, and 15 August 2023.

4.2. Participants

All patients prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors during the study period were identified to establish the population frame using electronic medical records from Suddhavej Hospital between 1 January 2019, and 15 August 2023. These patients were then screened according to predefined eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria were (1) patients aged ≥ 18 years; (2) patients diagnosed with T2DM or receiving SGLT2 inhibitors for other approved indications, such as heart failure or chronic kidney disease ≥ stage 3; (3) patients with documented laboratory evidence of ADRs (Eu-DKA, AKI, acute pancreatitis, or UTIs), or those clinically diagnosed with such adverse events and managed accordingly, regardless of normal laboratory findings; and (4) patients with a history of receiving care at Suddhavej Hospital during the specified study period. Exclusion criteria included patients who received SGLT2 inhibitors only during a single hospital visit and had no follow-up data on medication use or laboratory parameters indicating adverse events.

Medication adherence was routinely assessed for all patients by a clinical pharmacist using the pill count method as part of standard practice at our institution. Patients were instructed to take medications as prescribed, and adherence was considered acceptable when the pill count exceeded 90%. When suboptimal adherence or missed doses were identified, a pharmacist provided individualized, face-to-face counseling to reinforce adherence and review proper medication use. Adherence was reassessed at follow-up visits, and all counseled patients subsequently achieved pill count values > 90%.

4.3. Data Collection

Data were retrospectively collected and extracted from medical and electronic health records. Demographic information (age, sex, and comorbidities) was recorded. Additional data relevant to potential risk factors associated with SGLT2 inhibitor use were also extracted, including laboratory test results and concurrent medication use. Clinical symptoms indicative of UTIs, such as dysuria, increased urinary frequency and urgency, cloudy urine or hematuria, and lower abdominal pain, were documented. Furthermore, information on the duration of hospitalization and the principal admission diagnosis was included in the analysis. Drug–drug interactions were actively screened and managed in routine clinical practice, ensuring patient safety and minimizing the risk that unrecognized interactions affected the observed ADR.

During the study period, patients receiving dapagliflozin were prescribed the standard approved dose, and no renal dose adjustment was required based on the available drug information. In contrast, canagliflozin doses were adjusted in patients with reduced renal function, particularly those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, in accordance with the prescribing information. For luseogliflozin, use was not recommended in patients with eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; therefore, such patients did not receive this agent. The eGFR was calculated using the following equation (Table 5) [28]:

Table 5.

Equations for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by sex and serum creatinine [28].

Laboratory tests used to assess SGLT2 inhibitor-related ADRs were categorized according to the specific adverse event type. AKI was defined as an increase in serum creatinine (SCr) > 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h or an increase in SCr ≥ 1.5 times the patient’s baseline within 7 days, confirmed by a physician’s clinical diagnosis [29].

Eu-DKA was defined as a blood glucose level < 250 mg/dL, along with a blood ketone concentration > 3.5 mmol/L or a urine ketone level > 2+ [30]. Acute pancreatitis was identified either by a physician’s diagnosis or by meeting at least two of the following three criteria: typical abdominal pain, serum amylase or lipase levels ≥ three times the upper limit of normal, or characteristic findings on computed tomography imaging [31].

UTIs were identified based on the treating physician’s clinical diagnosis documented in the medical records. Diagnosis was supported by urinalysis findings (i.e., >5–8 white blood cells per high-power field or a positive nitrite test [32]) and documentation of antibiotic treatment. When available, positive urine culture results were used as confirmatory evidence in routine practice; however, culture positivity was not required because case identification primarily relied on clinical evaluation, patient-reported symptoms, and physician judgment.

4.4. Statistical Analyses

Discrete variables were presented as cumulative frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were summarized using means with standard deviations. The ADRs were recorded whenever they were documented during a visit, regardless of whether the reaction was newly occurring or a recurrence of a previously reported event. Therefore, an individual patient could experience the same ADR more than once across different visits, as well as different ADRs over time. Fisher’s exact test (Fisher–Freeman–Halton exact test for multi-group comparisons) was used to compare the prevalence of each adverse drug reaction across SGLT2 inhibitor regimens. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p-value < 0.05. To identify potential factors associated with UTI prevalence, a univariate analysis was initially performed. Variables with a p-value < 0.25 were subsequently included in a binary logistic regression model to further assess their association with UTI occurrence [33]. The strength of these associations was expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data management and statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Statiosn, TX, USA; Serial number: 401506248924).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found that AKI in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors was associated with age > 60 years, comorbid diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and the concomitant use of SGLT2 inhibitors with metformin, insulin, ACEIs/ARBs, or DPP4 inhibitors. UTI risk factors included female sex, age > 60 years, diabetes, hypertension, and co-administration with metformin, ACEIs/ARBs, DPP4 inhibitors, insulin, or acetylsalicylic acid, while for Eu-DKA, risk factors were age > 60 years, diabetes, hypertension, and concomitant use with metformin, DPP4 inhibitors, or ACEIs/ARBs. No cases of acute pancreatitis were observed. Canagliflozin and dapagliflozin had the highest prevalence of ADRs, likely because of their earlier introduction, with UTIs being the most frequently reported ADR. Further studies with larger cohorts and longer follow-up are needed to better define risk factors for SGLT2 inhibitor-associated adverse events and to inform optimized monitoring in routine clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., T.W., S.K., T.P. and W.P.; methodology P.S., T.W., S.K., T.P. and W.P.; software, P.S. and W.P.; validation, P.S., T.P. and W.P.; formal analysis, P.S., T.W., S.K., T.P. and W.P.; investigation, P.S., T.P. and W.P.; resources, P.S.; data curation, P.S., T.W., S.K., T.P. and W.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S., T.W. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, T.P. and W.P.; visualization, P.S. and W.P.; supervision, W.P.; project administration, P.S.; funding acquisition, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Faculty of Medicine, Mahasarakham University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mahasarakham University (IRB No. 249-080/2024, date of approval: 25 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective observational study design.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and Information Technology staff for their valuable assistance and support in data collection and research information retrieval for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACEIs | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| ARBs | Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| DPP-4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 |

| SGLT-2 | Sodium-glucose cotransporter |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| Eu-DKA | Euglycemic–diabetic ketoacidosis |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| SMP | Safety monitoring program |

| SCr | Serum creatinine |

| ADR | Adverse drug reaction |

| HCTZ | Hydrochlorothiazide |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| OR | Odds ratio |

References

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Perkins, B.A.; Fitchett, D.H.; Husain, M.; Cherney, D.Z.I. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2016, 134, 752–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, A.; Thool, A.R.; Daigavane, S. Understanding the Clinical Relationship Between Diabetic Retinopathy, Nephropathy, and Neuropathy: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e56674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Davies, M.J.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Fradkin, J.; Kernan, W.N.; Mathieu, C.; Mingrone, G.; Rossing, P.; Tsapas, A.; Wexler, D.J.; Buse, J.B. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2669–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, E.; Wexler, D.J.; Kim, S.C.; Paik, J.M.; Alt, E.; Patorno, E. Comparing Effectiveness and Safety of SGLT2 Inhibitors vs. DPP-4 Inhibitors in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Varying Baseline HbA 1c Levels. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, M.R.; Fisher, M. SGLT2 Inhibitors: Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Benefit Beyond Glycaemic Control. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Y.N.; Ting, A.Z.H.; Teo, Y.H.; Chong, E.Y.; Tan, J.T.A.; Syn, N.L.; Chia, A.Z.Q.; Ong, H.T.; Cheong, A.J.Y.; Li, T.Y.-W.; et al. Effects of Sodium/Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors and Combined SGLT1/2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular, Metabolic, Renal, and Safety Outcomes in Patients with Diabetes: A Network Meta-Analysis of 111 Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2022, 22, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapas, A.; Karagiannis, T.; Kakotrichi, P.; Avgerinos, I.; Mantsiou, C.; Tousinas, G.; Manolopoulos, A.; Liakos, A.; Malandris, K.; Matthews, D.R.; et al. Comparative Efficacy of Glucose-lowering Medications on Body Weight and Blood Pressure in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 2116–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regulation and Prequalification. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/regulation-prequalification/regulation-and-safety/pharmacovigilance (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Thai Food and Drug Administration. Guidelines for License Holders on Safety Reporting of Medicines for Human Use, Narcotics, and Psychotropic Substances Used for Medical Purposes After Marketing; The Government Buddhist Printing Office: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewpanukrungsi, W.; Anantachoti, P. Performance Assessment of the Thai National Center for Pharmacovigilance. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2015, 27, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrumpai, Y.; Kiatying-Angsulee, N.; Chamroonsawasdi, K. Identifying Safety Indicators of New Drug Safety Monitoring Programme (SMP) in Thailand. Drug Inf. J. 2007, 41, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Drug; Thai: Food and Drug Administration. Drug Product Information Search System, Ministry of Public Health. Available online: https://pertento.fda.moph.go.th/FDA_SEARCH_DRUG/SEARCH_DRUG/FRM_SEARCH_DRUG.aspx (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Hanke, J.; Romejko, K.; Niemczyk, S. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors in Diabetes and Beyond: Mechanisms, Pleiotropic Benefits, and Clinical Use—Reviewing Protective Effects Exceeding Glycemic Control. Molecules 2025, 30, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, J.E.; Tella, S.H.; Taylor, S.I.; Rother, K.I. Ketoacidosis Associated with SGLT2 Inhibitor Treatment: Analysis of FAERS Data. Diabetes. Metab. Res. Rev. 2017, 33, e2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.; Close, C.F.; Krentz, A.J.; Nattrass, M.; Wright, A.D. Euglycaemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis: Does It Exist? Acta Diabetol. 1993, 30, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, H.; Shafiq, M.A.; Batool, H.; Naz, T.; Ambreen, S. Diabetic Ketoacidosis in an Euglycemic Patient. Cureus 2020, 12, e10065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Kumar, T.; Singh, S.; Ambwani, S.; Charan, J.; Varthya, S.B. Euglycemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis Associated with SGLT2 Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Quantitative Analysis. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanushali, K.B.; Asnani, H.K.; Nair, A.; Ganatra, S.; Dani, S.S. Pharmacovigilance Study for SGLT 2 Inhibitors—Safety Review of Real-World Data & Randomized Clinical Trials. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoosuf, B.T.; Muhammed Favas, K.T.; Spoorthy, D.P.; Saini, A.; Garg, P.; Medenica, S.; Dutta, P.; Bansal, D. Risk of Genitourinary Tract Infections with SGLT-2 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials and Disproportionality Analysis Using FAERS. Endocrine 2025, 90, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, J.; Deng, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, G.; Chen, X.; Dong, Z. Influence of Sodium/Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors on the Incidence of Acute Kidney Injury: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1372421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilakou, D.; Karagiannis, T.; Athanasiadou, E.; Mainou, M.; Liakos, A.; Bekiari, E.; Sarigianni, M.; Matthews, D.R.; Tsapas, A. Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors for Type 2 Diabetes. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 159, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, K.M.; Ptaszynska, A.; Schmitz, B.; Sugg, J.; Parikh, S.J.; List, J.F. Urinary Tract Infections in Patients with Diabetes Treated with Dapagliflozin. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2013, 27, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitrakul, S.; Aksonnam, K.; Srivichai, P.; Wicheannarat, S.; Incomenoy, S. The Incidence and Risk Factors of Urinary Tract Infection in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Using SGLT2 Inhibitors: A Real-World Observational Study. Medicines 2022, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Z.; Guo, R.; Chandramouli, C.; Liu, L.; Tung, A.M.-O.; Tsang, C.T.-W.; Tse, Y.-K.; Chan, Y.-H.; Lee, C.-H.; Huang, J.-Y.; et al. Urinary Tract Infection and Continuation of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors in Diabetic Patients. Eur. Heart J. 2025, ehaf788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mao, W.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Hu, J. Analysis of Acute Pancreatitis Associated with SGLT-2 Inhibitors and Predictive Factors of the Death Risk: Based on Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Report System Database. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 977582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Mao, W.; Liu, D.; Hu, B.; Lin, X.; Ran, J.; Li, X.; Hu, J. Risk Factors for Drug-Related Acute Pancreatitis: An Analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1231320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F.; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A New Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimzadeh, I.; Barreto, E.F.; Kellum, J.A.; Awdishu, L.; Murray, P.T.; Ostermann, M.; Bihorac, A.; Mehta, R.L.; Goldstein, S.L.; Kashani, K.B.; et al. Moving toward a Contemporary Classification of Drug-Induced Kidney Disease. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, A.; Agrawal, A.; Morgan, F. Euglycemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Review. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2017, 13, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinlan, J.D. Acute Pancreatitis. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 90, 632–639. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, L.E.; Gupta, K.; Bradley, S.F.; Colgan, R.; DeMuri, G.P.; Drekonja, D.; Eckert, L.O.; Geerlings, S.E.; Köves, B.; Hooton, T.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: 2019 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, e83–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Model Building Strategy for Logistic Regression: Purposeful Selection. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.