Abstract

Background: The Allium cepa test is a widely used, cost-effective, and versatile model for assessing cytogenotoxicity. Cytotoxicity is determined through changes in root growth and the mitotic index, while genotoxicity is identified through chromosomal aberrations such as breaks, bridges, and micronuclei. Objective: To synthesize the methodological principles, applications, and interpretation of the assay’s endpoints, with emphasis on environmental monitoring, nanotoxicology, and the evaluation of emerging materials. Methods: An exploratory analytical approach was applied to identify and compare studies employing the Allium cepa assay across different contexts. The literature, selected from scientific databases, was organized to highlight methodological diversity and biomarker performance. Conclusions: Compared with other models, Allium cepa stands out for its simplicity, the availability of multiple cytogenotoxic markers, and its minimal ethical constraints, making it especially suitable for research in low-infrastructure settings. Future studies should work toward the international standardization of methodologies, the integration of this model with molecular and omics-based approaches, and its incorporation into predictive frameworks for environmental and human health risk assessment. In an increasingly complex toxicological landscape, Allium cepa emerges as a pivotal tool for enhancing toxicological surveillance and safeguarding biological systems.

1. Introduction

Environmental pollution and the increasing presence of emerging contaminants have heightened the need for reliable tools capable of assessing their biological effects. In this context, toxicology seeks to understand and predict the impacts that xenobiotics may exert on living systems; thus, their characterization is essential to determine whether these agents can damage genetic material or compromise cellular viability, providing key information for regulatory decision-making and for safeguarding human and environmental health [1,2,3]. However, predicting toxicity remains a challenging task due to the inherent variability of environmental interactions.

To address these challenges, a broad range of model organisms—plants, animals, and microorganisms—are employed as toxicological systems capable of generating relevant information on the mutagenic, cytotoxic, and genotoxic potential of numerous chemical compounds [4]. Among the most frequently used approaches are classical assays, including in vitro, such as lymphocyte cultures [5]; ex vivo, such as zebrafish (Danio rerio) [6]; and in vivo, such as plant-based models [3,7,8,9]. Collectively, these systems are accessible, cost-effective, and reproducible, and they exhibit strong concordance with widely established toxicological methodologies [1,4,10]. Nevertheless, they also present limitations and potential sources of error that must be considered when interpreting results [11].

Within this spectrum of models, plants represent particularly valuable tools for both basic research and the development of rapid testing methods. Their nearly ubiquitous distribution and their ability to absorb mutagenic and carcinogenic agents from soil, water, and air make them sensitive indicators of environmental stress. Exposure to contaminants can significantly alter vital functions such as germination, growth, and reproduction [12]. Among the plant species most frequently used as experimental models are Arabidopsis thaliana, Crepis capsularis, Glycine max, Hordeum vulgare, Solanum lycopersicum, Nicotiana tabacum, Pisum sativum, Tradescantia ruppius, Vicia faba, Zea mays, and Allium cepa [1,4,12], and all can be used as markers to identify genotoxic chemicals and monitor genotoxic contaminants in the environment in real time [13].

In particular, the Allium cepa model has proven to be one of the most versatile and effective tools for monitoring cytotoxic and genotoxic effects. Due to its multiple advantages (Table 1)—such as high sensitivity, low cost, ease of handling, and broad availability—it has been widely applied in the evaluation of environmental contaminants [12,13,14,15,16,17,18] pesticides [14], heavy metals [15], fertilizers, and emerging materials such as nanomaterials, microplastics, and pharmaceuticals [16]. It is also ethically preferable to animal testing, while still demonstrating a strong correlation with mammalian genotoxicity endpoints [13]

Table 1.

Characteristics and advantages of Allium cepa as a toxicological model.

Compared with other cytogenotoxicity models, the Allium cepa assay offers significant advantages. For instance, the micronuclei (MN) test in mice, although valuable for generating information relevant to higher organisms, is constrained by ethical considerations, high costs, and the need for specialized facilities and trained personnel [16]. Similarly, human-based assays, such as the MN test in peripheral blood via the Cytokinesis-Block Micronucleus (CBMN) method and oral mucosa essays, require adherence to ethical, technical, and financial considerations that limit their applicability in settings with restricted human, material, or economic resources [5,19]. In contrast, the versatility of the Allium cepa assay enables the exploration of adverse effects across multiple biological levels and reinforces its role as an integral tool for evaluating environmental risks and technological advances in innovative materials [1].

Given this context, the aim of this work is to examine the biological characteristics of the Allium cepa assay and to highlight its value as a tool for cytogenetic studies and the evaluation of genotoxicity and cytotoxicity. Emphasis is placed on its accessibility, versatility, low cost, and effectiveness in various experimental processes related to environmental toxicological monitoring and public health. Furthermore, this review analyzes the methodologies employed and explores the applications of the model in the monitoring of environmental contaminants, as well as its contributions to biomedical research.

2. Methodological Approach for the Allium cepa Assay

Levan first introduced the Allium cepa assay as an experimental model to investigate the effects of different concentrations of colchicine on mitosis in onion meristematic cells [20], and the assay was later standardized by Fiskesjö, 1985 [10]. The discovery of colchicine’s ability to disrupt the mitotic mechanism stimulated intensive research into the so-called c-mitotic reactions, particularly those involving the destruction of the spindle apparatus. During this period, it also became evident that various chemicals could induce gene alterations, bringing chemical mutagenesis to the forefront of toxicological research. This led to the establishment of distinctions such as “spindle poisons,” which interfere primarily with the mitotic spindle, and “chromosome poisons,” which mainly exert direct effects on chromosomal structure. Since then, the Allium cepa assay has been increasingly adopted across a wide range of toxicological and environmental studies, demonstrating its value as a sensitive and versatile cytogenetic tool [21,22].

To start the assay, the first step involves hydrating Allium cepa bulbs to stimulate cell division and root growth in the root meristematic tissue. The following working groups are then formed: the negative control, positive control, and those exposed to the test agent at the chosen concentration(s). The approving agent can stimulate, delay, inhibit, or even cause cell death. To determine the effect, it is necessary to compare the possible deviations in mitosis or cytokinesis between groups. For this reason, calculating the percentage of dividing cells—referred to as the mitotic index—is essential to estimate the proliferative activity of each experimental group and to enable meaningful comparisons among them [8,10]. Additionally, the test substance may cause direct or indirect damage to Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), commonly referred to as genotoxicity, which can be assessed by identifying cytogenetic alterations such as chromosomal rearrangements, DNA breaks, or disruptions in the mitotic spindle apparatus [8,10].

2.1. Reagents, Materials, and Laboratory

Conducting the Allium cepa assay does not require specialized instruments or complex materials. The basic setup includes an optical microscope equipped with 10×, 40×, and 100× objectives, along with standard slides and coverslips. Additional materials include 50 mL containers, watch glasses approximately 7 cm in diameter, fine-tipped forceps, and a vernier caliper. The reagents necessary for the procedure are distilled water, a positive control (such as an antineoplastic agent), the test compound, 50 mL of hydrochloric acid, 50 mL of acetic acid, Carnoy’s fixative (a 3:1 mixture of methanol and acetic acid), 50 mL of glycerinated gelatin, and 250 mL of DNA-specific dye equipment [10].

2.2. Selection and Pre-Treatment of Allium cepa Bulbs

To initiate the assay, onion bulbs can be obtained from local markets. Although genotype and growing conditions may influence the biochemical composition of the bulbs, these variations do not affect the validity of the Allium cepa assay. All varieties share a highly conserved diploid chromosome number (2n = 16) and exhibit consistent meristematic characteristics, resulting in comparable cytogenetic responses across bulbs from different sources. Moreover, the use of negative controls from the same batch ensures internal normalization of any baseline variation. Because the assay relies on chromosomal and mitotic endpoints—rather than on the metabolic composition of the bulb—the use of onions purchased from local markets is a widely accepted methodological practice and does not represent a limitation for the interpretation of the results [8,10,23].

It is recommended to select small bulbs—which also lower the amount of reagents required, optimizing resources without compromising assay quality—with vibrant green leaves, uniform size, and no visible signs of damage or pest infestation. The bulbs must have an intact germinative disc and healthy roots, as this region contains the meristem that drives root growth. If damaged, cell division decreases and the cytogenotoxic response is altered, increasing the risk of false negatives and compromising assay reliability. To prevent dehydration during handling and sorting, they should be kept moist by placing them in water or on damp paper towels. Prior to use, the bulbs are thoroughly washed to remove any soil residues. Dry leaves, outer scales, and the brownish basal plate are carefully removed, and the green leaves are trimmed to approximately 15 cm to facilitate manipulation. Before beginning the experiment, the roots are cut back to about 1 cm in length using sharp scissors or a razor blade, taking care not to damage the root primordia. The prepared specimens should then be acclimated for at least 24 h at a temperature between 19 and 24 °C by placing them in a container with their roots submerged in clean water [10,23].

2.3. Working Groups and Treatment

Each treatment should be formed with at least three specimens (replicates). However, it is recommended to select five bulbs, of which two are kept as replacements, since 20% show poor growth. The bulbs are distributed randomly or homogeneously to form the working groups. At least three groups of organisms must be formed, as follows: the first group is placed only in water (negative control), the second is exposed to an agent of known cytogenotoxicity, such as colchicine (positive control), and the third and subsequent groups will be the organisms exposed to the test agent at the chosen concentration(s).

After cleaning, each specimen is placed individually in containers with a capacity of approximately 50 mL, to which 10 mL of the solution with the test agent is previously added; the test substance is added in successive dilutions prepared with distilled water to obtain a profile to determine the dose–response curve. For the negative control, distilled water is used, and in the case of the positive control, colchicine [0.05%/1–2 h] [24], cyclophosphamide [50 mg/mL] [25], mitomycin C [2 mg/L] [26], sodium arsenite [0.37 mg/mL (2.84 mM)/1 h], ethyl methane sulfonate [125 µg/mL] [27] potassium dichromate [28], maleic hydrazide [4 × 10−3 M] [29], ethidium bromide [100 μg/mL] [26], Sodium azide (NaN3) [1 mg/L] [30], ethyl methyl sulphoxide (EMS) [0.2%] [31], methyl methane sulfonate [ZnSO4·7H2O 6 mg/L] [32], sodium benzoate [100 pm] [33], or any other agent already known to disrupt mitosis.

Each experiment must include the test substance, along with appropriate negative and positive controls. For instance, when evaluating five different dilutions in addition to the controls, a minimum of seven experimental groups is required, each composed of three replicates. This setup results in a total of 35 samples for the complete assay. Following preparation, the bulbs are incubated under dark conditions at 25 ± 0.5 °C for 72 h. A commonly recommended protocol involves exposing the bulbs to the test substance and the positive control for one hour, after which they are transferred to distilled water to complete the incubation period. Alternatively, the bulbs may remain in the test solution for the full 72 h, followed by an additional 48 h in distilled water. In either case, the liquid should be replaced every 24 h to ensure consistent volume and experimental conditions, depending on the specific objectives of the study [10].

2.4. Sample Collection and Preparation

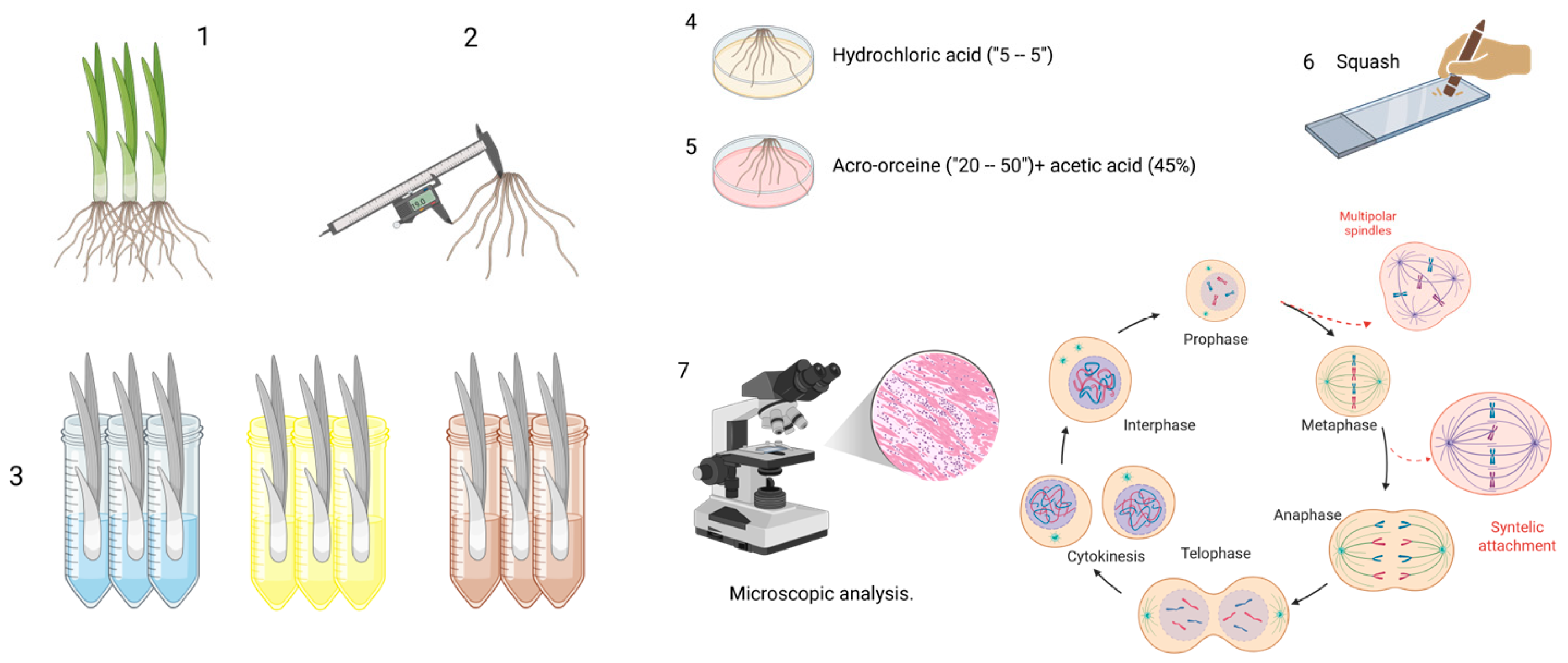

At the end of the acclimatization period, samples are counted and measured for length [10]. Subsequently, they are cut and fixed in Carnoy solution (methanol–acetic acid, 3:1) inside a small, labeled container with a secure lid. The samples can be kept in good condition for several months. Before preparing the roots, the excess fixative solution is removed by gentle washing with distilled water (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sample processing. (1) Specimen selection, (2) root length measurement, (3) working groups, (4,5) sample processing (hydrochloric acid, aceto-orcine + acetic acid [45%]), (6) squash, and (7) microscopic analysis. Created in BioRender. Delgado, D. (2025) https://BioRender.com/6m8c9ch (accessed on 9 January 2026).

To enhance the penetration of the dye into the cytoplasm and nucleus and to improve structural contrast during microscopic observation, the root cell walls are hydrolyzed by immersing the roots in concentrated hydrochloric acid for five minutes in a watch glass. After hydrolysis, the roots are gently rinsed with distilled water and subsequently stained by placing them in a few drops of the selected dye—commonly 2% hydrochloric aceto-orcein—for 30 to 50 min [10].

Several staining options are available, including acetic orcein [10], 1–2% acetocarmine [34,35], Feulgen [10], Saffrania (40–45%) [36], and Schiff’s reagent [37]. Even if epifluorescence-equipped microscopy is available, acridine orange can be used [38].

After staining, two to three roots are selected, rinsed, and placed on a microscope slide previously prepared with a few drops of 45% acetic acid and a drop of liquid glycerinated gelatin. A coverslip is then applied, and the squash technique is used—gently but firmly pressing the coverslip—to spread the cells into a single layer. This preparation allows for clear visualization of the various stages of mitosis and the detection of cytogenetic alterations under the microscope. Removing excess liquid by wrapping the slide with absorbent paper is essential. Finally, the slides are ready for microscopic analysis. It is recommended that only the slides that will be examined within 1 to 2 weeks be mounted to avoid drying the roots. During this time, the samples can be wrapped in wet napkins (in humid chambers), but ensure they are always moist and free from fungus.

Microscopic analysis: Samples are examined under an optical microscope at 10×, 40×, and 100× magnification. Cells in interphase and those in mitosis are identified and counted, as well as their phases (prophase [P], metaphase [M], anaphase [A], and telophase [T]). Chromosomal aberrations (fragments, lagging or sticky chromosomes, bridges, micronuclei, lobulated nuclei, binucleated cells, and polar nuclei) are also recorded. At least 1000–2000 cells are analyzed for each bulb; however, a minimum of two roots per specimen and three specimens per treatment should be evaluated to obtain representative data [10].

2.5. Caution

Although the Allium cepa assay is easy to use, each step must be performed accurately to avoid errors and to ensure reliable results and interpretations.

3. Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity Biomarkers in the Allium cepa Assay

3.1. Cytotoxicity Biomarker

A biomarker is a measurable biological feature—such as a molecule, cell, organism, or physiological process—that indicates a normal or pathological state, or the presence of chemical or environmental agents. In simple terms, it is an indicator that reveals changes in organisms or ecosystems in response to disease, contaminants, or treatments. In environmental research, biomarkers may consist of organisms or biological communities that reflect the presence of contamination in real socio-ecosystems or laboratory settings, allowing inferences about environmental health [4]. In the Allium cepa bioassay, cytotoxicity biomarkers are used to evaluate alterations in cell viability and function in response to toxic agents. Among the most employed indicators is the mitotic index, which reflects the proportion of cells undergoing division; a decrease in mitotic index indicates inhibition of the cell cycle. Root growth is another sensitive biomarker, as reduced root elongation reveals impairment of the apical meristem. Additionally, staining methods such as Evans blue allow the detection of membrane integrity loss, a characteristic feature of non-viable cells. Together, these biomarkers provide an integrated assessment of cytotoxicity, enabling the identification of early and sublethal effects before more complex genotoxic damage becomes apparent.

Phytotoxicity: Phytotoxic effects can be evaluated by the inhibition of root growth, which is identified by the observation of fewer and shorter roots compared to the control. Additionally, structural alterations of the root, such as chlorosis, necrosis, or tumors in the plant tissue, may also be observed [13].

Cell viability: Evan’s Blue Staining technique is widely used to assess cell viability by distinguishing living cells from those with compromised membrane integrity. Freshly harvested roots are first immersed in an aqueous 0.25% Evans blue solution for 15 min, allowing the dye to penetrate only cells that have lost membrane selectivity. After staining, ten root tips of uniform length (10 mm) are excised, thoroughly rinsed in distilled water for 30 min to remove excess dye, and then transferred to 4 mL of N, N-dimethylformamide for 1 h at room temperature. This solvent facilitates the extraction of the dye retained within damaged cells [39]. The amount of Evans blue released into the solvent is subsequently quantified spectrophotometrically by measuring absorbance at 600 nm. Because Evans blue selectively enters non-viable cells, the intensity of the extracted dye provides a direct quantitative indicator of cell membrane damage and overall cell mortality. This method is valued for its sensitivity, simplicity, and reliability in detecting early cytotoxic effects in plant tissues [13,39].

Cytotoxicity relates to damage caused to a cell’s vital processes, thereby affecting its viability and function. It also plays a critical role in the development of new pharmaceutical and biotechnological products. In Allium cepa, cytotoxicity is determined by alteration in the MI, which is established by the percentage of dividing cells concerning the total number counted, which is usually 1000–2000 meristematic cells, as well as alterations in the proportions of the different stages of the cell cycle concerning the control [1,10,11].

MI: This is the percentage of dividing cells among the total number of cells analyzed, which is necessary to determine cytotoxic and genotoxic effects. The following formula calculates it [40].

where MI = mitotic index, I = total of cells in interphase, P = total of cells in prophase, M = total of cells in metaphase, A = total of cells in anaphase, and T = total of cells in telophase.

Importance of mitotic index: Because a test agent could stimulate, delay, inhibit, or even cause cell death, establishing possible cytotoxic and even genotoxic effects is key to establishing the MI [8,10]. If after treatment, relative to the control, values below 50% are observed, this could be the result of alterations in growth and development; this action is called autoinhibition. If values above this threshold are observed, this indicates increased proliferation, which is not necessarily good, since it would be a mitogen or microstimulator. This could inhibit the natural brake on cell cycle progression and, consequently, lead to disordered cell division and even the formation of tumor tissues [8,41]. Therefore, their analysis, combined with root growth (root number and length), provides a comprehensive view of the cytotoxic effects of the agents evaluated [10,12,42].

3.2. Gentotoxicity Biomarker

Genotoxicity: This is the ability of a substance to damage genetic material; in meristem cells of Allium cepa, it is possible to detect chromosomal aberrations like anaphase bridges, vagrant or sticky chromosomes, as well as metaphases and micronuclei, among other cytogenetic alterations. This method accurately assesses the genotoxic risks associated with exposure to different compounds [1,3].

Genotoxic risk is determined using the following formula:

% of aberrant cells [40]. The evaluation of chromosomal abnormalities in Allium cepa enables the identification of disruptions in mitosis, including aberrations in the phases of mitosis (P, M, A, and T).

The percentage (%) is calculated using the following formula:

where

- Brg = cell with chromosomal bridges

- Stg = cell with straggler chromosomes

- Sticky = cell with sticky chromosomes

- Vag = cell with vagrant chromosomes

- BNc = binucleated cell

- Nls = cell with nuclear lesions

- PDV = cell with polar deviation in giant cells

- MNc = micronucleated cell

- Frequency of micronucleated cells (%)

Another alternative [43]

where

- MNc = Total of micronucleated cells.

4. Phase of Mitosis in Allium cepa

Before addressing the chromosomal aberrations observed in the Allium cepa assay, it is necessary to describe the phases of the mitotic process briefly. Although these stages are part of the cell cycle in all eukaryotic cells, their inclusion in this context is justified because the Allium cepa model allows each phase to be visualized with remarkable clarity due to the large size of its chromosomes and the high mitotic activity of its root meristematic cells [12,44,45]. This characteristic facilitates the identification of specific alterations that may occur during metaphase, anaphase, telophase, and other stages. Moreover, understanding the mitotic phases is crucial for accurately interpreting the biomarkers used in this assay, including the mitotic index and various types of chromosomal aberrations. Therefore, this description not only has educational value, but also provides a necessary methodological foundation for cytogenetic analysis in this plant model [12,45].

The observation of chromosomes in a cell shows that it is in some phase of the mitosis process. Determining the specific phase enables the calculation of the frequency of each phase and the determination of the mitotic index. During the G1 phase, the cell grows, produces essential proteins, and checks that conditions are suitable to move on to the S phase. If the cell is going to prepare for cell division, it must duplicate 100% of its genetic material during the S phase. During the G2 phase, the cell continues to grow, checks that DNA replication in the S phase is accurate, and produces the proteins needed for mitosis. On the other hand, if it is in cell division, it will be in the M phase. In the case of somatic cells, this process corresponds to mitosis, whereas in the case of germ cells, it is meiosis. Mitosis is a cell division process in which a mother cell generates two genetically identical daughter cells with the same number of chromosomes. It is essential for growth and tissue repair and reproduction in eukaryotic organisms.

Interphase: The cytoplasm is observed homogeneously. The nucleus is round or slightly oval, with a fine and continuous granular texture. Areas with varying staining intensities are identified but show no discontinuities. Although the nuclear envelope is not visible, it serves to delimit the nucleus. Chromatin, formed by DNA associated with histones, is decondensed, facilitating gene transcription and the replication of genetic material. This state of decondensation is a distinctive feature of the interface.

In some cases, the nucleoli―which regulate the cell cycle and are responsible for transcription and ribosomal assembly―are distinguishable and are observed as one or two clear or almost colorless areas due to their high RNA content, which prevents them from staining. They are usually found in the center of the nucleus or slightly displaced towards the periphery. Nucleoli have no membrane; they are visualized as small translucent spheres and the most heterochromatic region. When the cells are close to entering mitosis, the nucleoli become more voluminous and increases significantly in size. The nucleolus disappears during cell division. After the separation of the daughter cells by cytokinesis, the nucleolus fragments fuse again around the nucleolar organizer regions (NORs) of the chromosomes. It can be observed that in anaphase, the cells lack nucleoli. In telophase, they reappear, and in interphase, they become visible again.

5. Cytogenetic Alteration

The Allium cepa test is, par excellence, one of the most widely used to study chromosomal alterations induced by toxic, cytotoxic, and genotoxic agents [23]. Based on its principle, chromosomal aberrations can be classified according to their mechanism of formation.

These alterations are classified as clastogenic, which cause structural damage to chromosomes, and aneugenic, which interfere with the mitotic spindle and disrupt chromosome segregation.

Clastogenic agents induce chromosome breaks that may lead to the formation of bridges and micronuclei. In contrast, aneugenic agents generate c-metaphases, lagging chromosomes, chromosome loss, polar or multipolar divisions, chromosomal adhesion, and micronuclei, among many other spindle-related abnormalities [12,42].

Among the most relevant alterations are chromosomal bridges and breaks (clastogenic activity), as well as chromosome loss, lagging, adhesions, and multipolarity, which are typical effects of aneugenic agents. Other observable anomalies include chromosome or chromatid fragments, interchromatinic or subchromatidic connections, nucleoplasmic bridges, heteromorphic chromosomes, dicentric or ring chromosomes, and the presence of micronuclei. Even phenomena such as mitotic asynchrony or alterations in cell cycle duration may be considered additional indicators of cytogenetic damage [8,23,45,46].

5.1. Clastogenetic/Structural Alterations

The primary feature that defines clastogenic activity is the presence of chromosomal bridges and chromosome breaks [23]. However, some authors also mention chromosome fragments (these can originate from micronuclei), nucleoplasmic bridges, heteromorphic chromosomes, dicentric or ring chromosomes, and mitosis [8].

Micronuclei are small, extranuclear bodies composed primarily of chromosomes or chromosomal fragments that fail to reintegrate into the main nucleus after cell division. Also referred to as Howell–Jolly bodies, these structures contain DNA that remains isolated due to delays during anaphase. Their membranes are often unstable and susceptible to rupture without repair. The DNA within micronuclei may undergo condensation, replication, and asynchronous division, potentially contributing to nuclear content. In some cases, this material may experience chromothripsis and re-enter the primary nucleus, leading to genomic instability and potentially promoting cancer development [47].

Sticky chromosomes indicate a highly toxic effect, which is generally not reversible and probably leads to cell death [10].

Anaphase bridges occur when abnormal breaks and fusions of chromosomes or chromatids occur, typically visible during anaphase. Chromosomes do not separate properly and remain connected by thin strands of genetic material. This results in single- and double-stranded DNA breakage [10]. Bonciu mentions that interchromatin or subchromatid connections, known as chromosome bridges, are chromosomal structural changes that can result from exchanges between homologous or non-homologous chromosomes and from the formation of dicentric chromosomes or deficient activity of replication enzymes [8].

Nucleoplasmic bridges originate from dicentric chromosomes or occur because of a faulty longitudinal breakdown of sister chromatids during anaphase. The production of two simultaneous breaks in the same chromosome and the subsequent union of non-centromeric fragments explain the formation of ring chromosomes [8].

Chromosomal breakage represents a critical event that, when followed by the abnormal rejoining or fusion of broken ends of adjacent chromatids, can lead to the formation of dicentric chromosomes, that is, structures containing two active centromeres. This type of aberration reflects defective DNA repair processes and is commonly associated with clastogenic activity, as it compromises chromosomal stability and may interfere with the normal segregation of chromosomes during mitosis [8].

Acentric fragments are segments of chromosomes without centromeres that do not segregate correctly during cell division and give rise to micronuclei formation.

Giant cells may correspond to polyploid cells formed because of endoreplication or endomitosis, processes in which the genetic material is replicated without subsequent cell division. Such cells are often found in tissues exposed to genotoxic or cytotoxic stress, and their presence serves as a morphological indicator of disrupted cell cycle regulation [8].

Cell cycle asynchrony, including internuclear asynchrony, is frequently observed in large multinucleated cells, where different nuclei coexist at various early stages of mitosis. This phenomenon is accompanied by interchromosomal asynchrony, evidenced by uneven chromosome condensation throughout the mitotic stages, and by intrachromosomal asynchrony, characterized by a gradient of chromatin compaction within a single chromosome.

Binucleated cells undergo division, meaning that both nuclei may enter mitosis synchronously, a phenomenon known as synchronous mitosis. These irregularities reflect disruptions in cell cycle control mechanisms and are often associated with genotoxic effects that interfere with mitotic progression, leading to genomic instability and increasing the likelihood of structural or numerical chromosomal aberrations [8].

5.2. Aneugenic/Numerical Alterations

Aneugenic agents induce laggard, delay, and vagrant chromosomes, chromosome loss, chromosome stickiness, C-metaphase, multipolar divisions, and nuclear buds [41].

Aneuploidy: This refers to the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell, typically resulting from segregation errors during mitosis or meiosis.

Polyploidy: This is an increase in the complete number of chromosomes, often associated with failure of cytokinesis.

Lagging chromosomes: These occur when chromosomes do not remain connected to the spindle fiber, allowing them to move to either pole. The stickiness is caused by further shrinkage or condensation of chromosomes or depolymerization of DNA and partial dissolution of nucleoproteins. This alteration is indicative of toxic effects that are typically irreversible and may ultimately result in cell death.

Vagrant chromosomes: These are chromosomes that migrate prematurely toward the cell poles, ahead of their associated chromosome group, causing unequal distribution of genetic material between daughter cells. This phenomenon may result from structural interference with DNA and its associated proteins or from defects in the assembly and function of the mitotic spindle apparatus.

Other relevant mitotic alterations include the presence of lagging chromosomes (delayed or vagrant chromosomes with abnormal displacement toward the spindle poles), precocious or forward chromosomes (premature movement toward the poles), and star-shaped polar anaphase, characterized by an irregular arrangement of chromosomes during segregation.

The formation of lagging or vagrant chromosomes (laggards–vagrants) is thought to be associated with the inhibition of tubulin polymerization or alterations in cytoskeletal proteins, which interfere with the proper formation and function of the mitotic spindle. These abnormalities reflect a dysfunction in microtubule dynamics and may have significant consequences for chromosome segregation, promoting the development of aneuploidy and other chromosomal aberrations [8].

C-mitosis: This is when a disorganized metaphase of the metaphase plate is observed. The disintegration of the spindle forms it; the chromosomes are randomly dispersed throughout the cell and form characteristic configurations. After the division of the chromosomes, a single nucleus of tetraploid restitution is often formed. If a substance capable of giving complete c-mitosis is applied in more dilute solutions, partial c-mitosis may be induced. The spindle is not wholly inactivated, but it is unable to achieve an equal chromosome distribution; the result is multipolar anaphases, which involve the risk of aneuploidy. C-mitosis, also known as stathmokinesis, refers to an alteration in the mitotic process in which the toxic effect of colchicine or other antimicrotubular agents prevents the transition from metaphase to anaphase by blocking tubulin polymerization, thus inhibiting the proper formation of the mitotic spindle.

Because of this interruption, the chromosomes remain aligned on the equatorial plane without separating toward the poles, leading to the formation of polyploid cells. This phenomenon is considered a typical indicator of aneugenic activity, as it reflects a disturbance in microtubule dynamics and in the chromosomal segregation mechanisms that ensure genomic stability [8,10].

Polar metaphase: This is when, instead of lining up correctly in the center of the cell, the chromosomes are clustered toward one of the poles (ends) of the cell. This indicates that the cell has been affected by a substance that interferes with the correct distribution of genetic material during cell division.

Binucleated cells (BNs): These are formed by aberrant spindle division during early anaphase or failure of cytokinesis after telophase. Alterations in the ratio between histones and other nuclear proteins responsible for maintaining the optimal structure and organization of chromatin may lead to an increase in chromatin adhesiveness, directly affecting the dynamics of chromosomal condensation and segregation. This structural deregulation can manifest as the formation of atypical metaphases and anaphases, often accompanied by persistent chromosomal bridges during anaphase and telophase, which reflect defective separation of sister chromatids. Therefore, cytokinesis may be inhibited, resulting in the formation of binucleated or multinucleated cells, phenomena associated with genomic instability and an increased risk of cellular transformation.

Nuclear buds: Moreover, nuclear buds are recognized as morphological indicators of polyploidization and gene amplification processes. Their appearance represents a cellular response to excess or imbalanced genetic material, facilitating the expulsion of surplus or damaged DNA in aneuploid or genetically unstable cells. These events not only reveal failures in DNA repair mechanisms and cell cycle control but may also constitute a preceding stage to apoptosis or to the development of more complex structural aberrations [8].

Nuclear abnormalities (NAs): These can be observed in daughter cells as a similar structure to the main nucleus but in reduced size (lobulated nuclei, nuclei carrying nuclear buds, polynuclear cells, and mini cells), which may indicate a process of cell death, since these abnormalities are very rare in the root cells of negative control experimental groups, but very abundant in positive ones. Specifically, nuclear sprouts may arise because of the elimination of excess genetic material derived from the polyploidization process [8].

6. Advantages and Limitations

6.1. Advantages of Allium cepa

The Allium cepa assay is recognized as a dependable and versatile tool in both biological and toxicological research. Its ability to generate consistent and reproducible data makes it highly valuable across various scientific disciplines. Thanks to its affordability, simplicity, and minimal technical requirements, it is widely accessible to the broader scientific community. This assay has proven particularly useful in fields such as plant biology [48,49], toxicology [50,51,52], and environmental monitoring [53,54,55,56]. Moreover, it enables the assessment of cytotoxic and genotoxic effects by detecting chromosomal damage, disturbances in cell division, and other adverse responses to chemical exposure—information that is essential for risk evaluation and regulatory frameworks [38]. Its low cost and methodological simplicity further reinforce its suitability for monitoring pollutants in soil, water, and air, thereby supporting effective environmental management and informed decision-making in surveillance programs [57,58].

One of the key advantages of the Allium cepa model is the large size of its chromosomes, which greatly facilitates staining and microscopic observation. This allows for the clear identification of chromosomal aberrations such as bridges, fragments, and micronuclei [59,60,61]. Additionally, Allium cepa exhibits a well-defined and rapid cell cycle that can be easily synchronized, enabling precise evaluation of mitotic phases and the effects of toxic agents on cell division [59].

The model also demonstrates high sensitivity to a wide range of genotoxic and cytotoxic agents, including environmental contaminants [7], chemical compounds [61], various forms of radiation [46] and nanomaterials―AuNps [62,63,64], AgNPs [62], AgNPs sigma [65], AgNps ArgovitTM [43], AgMO3 [43], CuNPs [66], and TiO2NPs [67]—making it a versatile system for initial toxicity testing and an excellent option for preliminary toxicity screening.

Moreover, the method is both simple and cost-effective. Root cultivation and treatment procedures are easy to perform and do not require sophisticated equipment or a large team of specialized personnel. In addition, the staining and analytical reagents are inexpensive, making it feasible to carry out statistically robust studies with minimal resources.

The Allium cepa test offers the advantage of assessing multiple biological indicators simultaneously. It allows for evaluation of the mitotic index (MI) to determine cytotoxicity, the frequency of chromosomal aberrations to detect genotoxicity, and the formation of micronuclei as a marker of genetic damage. Its capacity to directly analyze water, soil, or chemical samples reinforces its value as an environmentally relevant model for monitoring potentially toxic substances across diverse ecosystems [56].

The cytogenetic responses observed in Allium cepa are considered extrapolatable to a wide range of eukaryotic organisms, given the high degree of conservation in core cellular processes such as mitosis, cell cycle regulation, and DNA damage and repair mechanisms. This biological relevance grants the model both ecological and biomedical importance, enabling the prediction of genotoxic and cytotoxic risks in higher organisms, including humans [53].

Another key benefit is the speed at which results can be obtained, making it a time-efficient method suitable for studies in genetic toxicology, ecotoxicology, mutagenesis, genotoxicity, and carcinogenesis. Its flexibility supports analyses at morphological, cytological, and molecular levels, further solidifying its role in scientific research. Internationally, the Allium cepa test is recognized as a standard model in genotoxicity and cytotoxicity testing due to its methodological robustness and reproducibility [18,68].

Its low cost and operational simplicity make it particularly suitable for laboratories with limited resources, especially in low- and middle-income countries. This enhances global participation in environmental and public health surveillance and aligns with the growing demand for alternative testing methods that promote animal welfare and uphold ethical standards in scientific research. This is especially noteworthy, as there is a growing global demand for alternative testing methods that respect animal welfare and safeguard the integrity of human subjects. Replacing animal models with plants contributes to a reduction in the number of animals used in experimentation and enhances the refinement of more ethical and sustainable experimental methods. As such, the Allium cepa test aligns with the principles of replacement, reduction, and refinement (3R), contributing to the development of more ethical and sustainable practices in scientific research. In addition to its scientific applications, this model serves as an effective educational resource. It provides students and early-career researchers with hands-on experience in observing key biological processes such as the cell cycle, mitosis, and the mechanisms of genotoxicity and cytotoxicity [12]. The Allium cepa test stands out for its simplicity, affordability, and reliability, making it a valuable tool across multiple scientific disciplines. Its capacity to produce consistent and reproducible data, along with its adaptability to both environmental and toxicological contexts, underscores its relevance. Moreover, ongoing research continues to expand its potential applications and improve its effectiveness, reinforcing its role as a key instrument in environmental monitoring, biomedical investigation, and the promotion of human health.

6.2. Potential and Challenges of Allium cepa as a Bioassay for Nanomaterials

According to the collected data, Argovit AgNPs stand out as the least cytogenotoxic agents, with a mitotic index (MI) of 23% and a micronucleus (MN) frequency of 2.6 ± 1.1, compared with controls, with the exception of water. Specifically, silver nitrate (AgNO3) showed an MI of 8.6% and MN = 4, sodium arsenite exhibited an MI of 12.5% and MN = 13 ± 3.6, while, as expected, the water control recorded an MI of 12.5 ± 1.5 and MN = 1.3 ± 0.5 [43]. Overall, the chemical controls induced a marked reduction in root growth, a significant decrease in the mitotic index, and an increase in micronucleus formation, evidencing greater cytotoxic and genotoxic effects compared with Argovit AgNPs. In contrast, materials such as CuNPs (IM = 13.0 ± 0.4) [66] and VAuNPs (IM 43.7 ± 0.7) [64] exhibited much milder effects, whereas TiO2 NPs (IM = 60.6 ± 60.5) [67] showed strong growth inhibition accompanied by less consistent genotoxic outcomes across studies.

Comparative interpretation among studies is limited by substantial methodological heterogeneity, including variations in exposure times (72 h, 4 h, or 1 h), high variation in the concentrations tested, and the use of different units ranging from 1 µg/mL, 10 mg L−1, or even ppm. Regarding fixatives, the most commonly used include Carnoy’s solution and 80% MeOH. However, in several studies, this parameter is not consistently reported. With regard to staining procedures, a wide diversity of dyes has also been reported, among which aceto-orcein, safranin, and acetocarmine are the most used. These discrepancies hinder the establishment of direct equivalences between assays and complicate the integrated interpretation of the findings [43,62,63,64,65,66,67].

In this context, the observed variability also highlights the versatility and sensitivity of the Allium cepa model, which is capable of detecting both cytotoxic and genotoxic effects under a broad range of experimental conditions. Nevertheless, the results underscore the urgent need to standardize the methodology at an international level through well-defined and widely adopted protocols that enable more precise, reproducible, and rigorous comparisons in the risk assessment of emerging materials.

6.3. Limitations of Allium cepa

Although the Allium cepa test is recognized for its efficiency and cost-effectiveness, it is important to consider its limitations. To achieve a more comprehensive assessment of the cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of the agents under study, it is advisable to complement this assay with additional methodologies [69].

Biological variability: As with any biological system, the Allium cepa test is subject to natural variability, which may affect the reproducibility of experimental outcomes.

Restricted applicability to plant organisms: While the test yields valuable insights, its results cannot always be directly extrapolated to animals or humans due to fundamental physiological and metabolic differences.

Variable sensitivity to specific agents: Certain substances may produce distinct effects in plant versus animal cells, potentially leading to underestimation or overestimation of their toxicological impact. Furthermore, the model’s sensitivity can be influenced by experimental variables such as culture conditions and treatment protocols. To mitigate this limitation, it is essential to standardize methodologies and environmental parameters, thereby enhancing the reliability and consistency of the results [70,71,72].

Lack of specific mechanisms: Allium cepa does not allow the evaluation of complex metabolic pathways or processes specific to animal organisms, such as liver metabolism or immune response. The onion model allows the detection of a wide range of genotoxic agents but does not allow the identification of some specific types of genetic damage or the mechanism of action underlying such damage. Therefore, it is recommended to complement the Allium cepa test with other specialized tests capable of providing more detailed insights into the specific types of genetic damage and underlying mechanisms of action.

Controlled experimental conditions: To ensure the reliability of results, the Allium cepa test requires a stable experimental environment, including controlled temperature, light, and humidity. This requirement may pose challenges when applying the method in settings where such conditions cannot be consistently maintained.

Results influenced by environmental factors: The response of Allium cepa can be affected by external variables such as water quality, soil composition, or nutrient availability. These factors may introduce biases or variability in environmental studies, potentially influencing the interpretation of toxicological effects.

Limited time for evaluation: Its rapid cell cycle, although helpful, may make it challenging to observe chronic or long-term effects.

The complexity of some treatments: Insoluble substances or substances with low penetration into plant tissue may not show significant effects, which could underestimate their potential toxicity.

Experience and technical knowledge: The interpretation of genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on onion roots requires a certain degree of experience and technical knowledge to ensure the accuracy of the results.

7. Bibliometric Indicators of the Relevance and Expansion of the Allium cepa Assay

A PubMed search conducted on 25 November 2025, using the keyword “Allium cepa”, retrieved 6377 publications, reflecting the substantial scientific interest in this biological model. When the search was refined to toxicological endpoints, the prominence of the assay became even more apparent: “Allium cepa genotoxicity” yielded 685 results, “Allium cepa cytotoxicity” 514, “Allium cepa chromosomal aberration” 491, “Allium cepa micronuclei” 196, “Allium cepa toxicology” 179, and “Allium cepa toxicogenomics” 9. These figures demonstrate both the versatility of the assay and its consolidation as a widely used tool in cytonetics and environmental toxicology.

Historical comparisons further illustrate this expansion. Bonciu et al. previously reported 3170 results for the Allium cepa test on Google Scholar [8]. In contrast, the same query now yields approximately 423,000 results, indicating an exponential increase in the visibility and application of this model. Although not all entries are strictly related to toxicology, a more targeted search for “Allium cepa genotoxicity” currently produces 19,100 results, reaffirming the central role of the assay in genotoxicity research and its continued adoption across diverse scientific fields [41].

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

The Allium cepa assay reasserts itself as a robust and sensitive bioindicator for detecting cytogenetic and cytotoxic effects resulting from exposure to emerging contaminants and toxic agents. Its capacity to reveal early cellular alterations in response to nanomaterials, persistent organic pollutants, complex chemical mixtures, and other environmentally relevant stressors positions it as a strategic tool for monitoring systems subjected to dynamic and insufficiently characterized chemical burdens. Its low cost, operational simplicity, and the absence of ethical concerns associated with animal-based models further enhance its value in resource-limited settings.

Nevertheless, the model presents limitations inherent to its plant-based nature, including biological variability among bulbs and a lack of metabolic and toxicokinetic parameters comparable to those of higher organisms. These factors, combined with methodological heterogeneity across studies, underscore the need for a critical and context-dependent application of the bioassay.

In addition, the manual scoring required by the Allium cepa assay—particularly the microscopic examination and counting of hundreds or thousands of cells—remains one of its most time-consuming aspects. In response to this challenge, emerging tools in digital image analysis, machine learning, and artificial intelligence offer promising avenues for automating the detection of mitotic stages and chromosomal abnormalities. Although still under development for this specific bioassay, these technologies have been successfully applied in other cytogenetic contexts, suggesting that future integration of automated workflows could improve efficiency, reduce observer bias, and enhance reproducibility. Incorporating these innovations represents an important perspective for modernizing the assay and increasing its applicability in large-scale monitoring programs.

This reinforces the importance of advancing toward internationally standardized protocols that define uniform exposure criteria, control selection, and biomarker quantification methods. Such harmonization will improve cross-study comparability and strengthen the assay’s regulatory relevance. Even so, its utility as an initial screening platform remains unequivocal.

The incorporation of the Allium cepa assay into environmental and human health risk-assessment frameworks, alongside its expanding role in nanotoxicology, is expected to further broaden its impact. Moreover, integrating the assay with multicellular bioindicators and with molecular and omics-based approaches—including transcriptomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics—will better link meristematic responses to specific biological mechanisms, enhance interpretive resolution, and support the development of more predictive and transdisciplinary risk-assessment models.

Ultimately, the Allium cepa assay does more than detect early cellular damage: it has become an essential tool for anticipating risks in a world where contaminants evolve faster than regulatory capacity, thereby playing a critical role in safeguarding environmental and human health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: O.T.-B. and M.E.A.-G.; methodology: O.T.-B., M.E.A.-G. and M.L.-R.I.; validation: F.C.-F., B.R.-R., R.B.-B. and A.S.-G.; investigation: O.T.-B., M.E.A.-G., I.G.-F., M.C.-D. and K.I.O.-J.; writing—original draft preparation. O.T.-B., M.E.A.-G., K.I.O.-J., M.L.-R.I., F.C.-F. and B.R.-R.; review and editing: M.E.A.-G., O.T.-B., I.G.-F., M.C.-D., A.S.-G. and R.B.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We express our sincere gratitude to the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Inno-vation (SECIHTI) for the support received through the Postdoctoral Fellowships in Mexico 2023 Program, Academic Modality (Registration No. 19104). The authors gratefully acknowledge the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara (UAG) for the financial support provided through its Fondo Semilla Program, which covered the article publication fees.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Our special thanks go to Hugo Alexander Rangel Vázquez for his outstanding technical support. We also extend our appreciation to the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara (UAG) and the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC) for the facilities and valuable institutional support provided during the development of this postdoctoral stay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to the preparation of this work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A | Anaphase |

| BNc | Binucleated cell |

| Brg | Cell with chromosomal bridges |

| CBMN | Cytokinesis-block micronucleus |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| EMS | Methyl sulphoxide |

| I | Total of cells in interphase |

| M | Metaphase |

| MI | Mitotic index |

| MN | Micronucleus |

| MN | Micronucleated cell |

| NA | Nuclear abnormality |

| Nls | Cells with nuclear lesions |

| NORs | Nucleolar organizer regions |

| P | Prophase |

| PDV | Cell with polar deviation in giant cells |

| Stg | Cell with straggler chromosomes |

| Sticky | Cell with sticky chromosomes |

| T | Telophase |

| Vag | Cell with vagrant chromosomes |

| ZnSO4·7H2O | Methyl methane sulfonate |

References

- Marmiroli, M.; Marmiroli, N.; Pagano, L. Nanomaterials Induced Genotoxicity in Plant: Methods and Strategies. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evarista Arellano-García, M.; Torres-Bugarín, O.; Roxana García-García, M.; García-Flores, D.; Toledano-Magaña, Y.; Sofia Sanabria-Mora, C.; Castro-Gamboa, S.; García-Ramos, J.C. Genomic Instability and Cyto-Genotoxic Damage in Animal Species; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.F. The present status of higher plant bioassays for the detection of environmental mutagens. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1994, 310, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomartire, S.; Marques, J.C.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Biomarkers based tools to assess environmental and chemical stressors in aquatic systems. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, M.; Bonassi, S.; Turner, J.; Lando, C.; Ceppi, M.; Chang, W.P.; Holland, N.; Kirsch-Volders, M.; Zeiger, E.; Bigatti, M.P.; et al. Intra- and inter-laboratory variation in the scoring of micronuclei and nucleoplasmic bridges in binucleated human lymphocytes: Results of an international slide-scoring exercise by the HUMN project. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2003, 534, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, L.; Santonastaso, M.; Mottola, F.; Costagliola, D.; Suero, T.; Pacifico, S.; Stingo, V. Genotoxicity assessment of TiO2 nanoparticles in the teleost Danio rerio. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 113, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.F. Chromosome aberration assays in allium. A report of the U.S. environmental protection agency gene-tox program. Mutat. Res./Rev. Genet. Toxicol. 1982, 99, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonciu, E.; Firbas, P.; Fontanetti, C.S.; Wusheng, J.; Karaismailoğlu, M.C.; Liu, D.; Menicucci, F.; Pesnya, D.S.; Popescu, A.; Romanovsky, A.V.; et al. An evaluation for the standardization of the Allium cepa test as cytotoxicity and genotoxicity assay. Caryologia 2018, 71, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Tettamanti, M. Testing Times in Toxicology—In Vitro vs In Vivo Testing. ALTEX Proc. 2013, 2, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Fiskesjo, G. Allium test on river water from Braan and Saxan before and after closure of a chemical factory. Ambio 1985, 14, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Yahya, F.A.; Hashim, N.F.M.; Israf Ali, D.A.; Chau Ling, T.; Cheema, M.S. A brief overview to systems biology in toxicology: The journey from in to vivo, in-vitro and –omics. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, D.M.; Marin-Morales, M.A. Allium cepa test in environmental monitoring: A review on its application. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2009, 682, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavarekere Venkataravanappa, J.; Saraswathi, S.; Shapur Gopalkrishnashetty, Y.; Soman, P.; Mitta Lakshminarayana Gupta, N.; Srivastava, S.; Kumari, S. Allium cepa L. as a bioindicator: A comprehensive review of genotoxicity and cytotoxicity assessment methods. Toxicon 2025, 267, 108586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dizdar, A.M.; Kopliku, D. Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Potency Screening of Two Pesticides on Allium cepa L. Procedia Technol. 2014, 8, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzima, C.S.; Banti, C.N.; Hadjikakou, S.K. Assessment of the biological effect of metal ions and their complexes using Allium cepa and Artemia salina assays: A possible environmental implementation of biological inorganic chemistry. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 27, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda-Yslas, I.Y.; Torres-Bugarín, O.; García-Ramos, J.C.; Toledano-Magaña, Y.; Radilla-Chávez, P.; Bogdanchikova, N.; Pestryakov, A.; Ruiz-Ruiz, B.; Arellano-García, M.E. AgNPs ArgovitTM modulates cyclophosphamide-induced genotoxicity on peripheral blood erythrocytes in vivo. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshika, J.D.; Zakariyyah, A.M.; Zaynab, T.; Zengin, G.; Rengasamy, K.R.R.; Pandian, S.K.; Fawzi, M.M. Traditional and modern uses of onion bulb (Allium cepa L.): A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, S39–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.H.; Xu, Z.; Xu, C.; McConnell, H.; Valtierra Rabago, E.; Adriana Arreola, G.; Zhang, H. The improved Allium/Vicia root tip micronucleus assay for clastogenicity of environmental pollutants. Mutat. Res./Environ. Mutagen. Relat. Subj. 1995, 334, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Bugarín, O.; Garcia-Arellano, E.; Onel Salas-Cordero, K.; Molina-Noyola, L. Micronuclei and Nuclear Abnormalities as Bioindicators of Gene Instability Vulnerability. Austin J. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2019, 6, 1023. [Google Scholar]

- Levan, A. The effect of colchicine on root mitoses in allium. Herditas 1938, 24, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, E.C.D.; da Silva Pinheiro, R.; Costa, B.S.; Lima, R.M.T.D.; Dias, A.C.S.; de Jesus Aguiar dos Santos, T.; Nascimento, M.L.L.B.D.; de Castro e Sousa, J.M.; Islam, M.T.; de Carvalho Melo Cavalcante, A.A.; et al. Allium cepa as a Toxicogenetic Investigational Tool for Plant Extracts: A Systematic Review. Chem Biodivers 2024, 21, e202401406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levan, A. Chemically induced chromosome reactions in Allium cepa and Vicia faba. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1951, 16, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banti, C.N.; Hadjikakou, S.K. Evaluation of Genotoxicity by Micronucleus Assay in vitro and by Allium cepa test in vivo. Bio-Protocol 2019, 9, e3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, M.K. Evaluation of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of treated wastewater in Almadinah Almonawrah, Saudi Arabia using Allium cepa assay. Pak. J. Bot. 2022, 54, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okorie Asita, A.; Moramang, S.; Rants’o, T.; Magama, S. Modulation of mutagen-induced genotoxicity by vitamin C and medicinal plants in Allium cepa L. Caryologia 2017, 70, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madike, L.N.; Takaidza, S.; Ssemakalu, C.; Pillay, M. Genotoxicity of aqueous extracts of Tulbaghia violacea as determined through an Allium cepa assay. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2019, 115, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, K.Y.; Darah, I.; Yusuf, U.K.; Yeng, C.; Sasidharan, S. Genotoxicity of Euphorbia hirta: An Allium cepa assay. Molecules 2012, 17, 7782–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.P.; Aarey, A.; Tamkeen, S.; Jahan, P. Forskolin: Genotoxicity assessment in Allium cepa. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2015, 777, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujon, E.; Sta, C.; Trivella, A.; Goupil, P.; Richard, C.; Ledoigt, G. Genotoxicity of sulcotrione pesticide and photoproducts on Allium cepa root meristem. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2014, 113, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Devashree, Y.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, S.; Wani, M.S.; Singh, V. Genotoxic effect of fruit extract of wild and cultivated cucurbits using Allium cepa assay. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2022, 28, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerda, D.; Biagi Bistoni, M.; Pelliccioni, P.; Litterio, N. Allium cepa as a biomonitor of ochratoxin A toxicity and genotoxicity. Plant Biol. 2010, 12, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Filho, R.; Vicari, T.; Santos, S.A.; Felisbino, K.; Mattoso, N.; Sant’anna-Santos, B.F.; Cestari, M.M.; Leme, D.M. Genotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and triggering of defense mechanisms in Allium cepa. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2019, 42, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkoǧlu, Ş. Genotoxicity of five food preservatives tested on root tips of Allium cepa L. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2007, 626, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, R.; Arjun, J. Evaluation of industrial effluent and domestic sewage genotoxicity using Allium cepa bioassay. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Commun. 2018, 11, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıyıksız, G.; Kalefetoğlu Macar, T.; Çavuşoğlu, K.; Yalçın, E. A study investigating the multifaceted toxicity induced by triflumuron insecticide in Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaram, A.K.; Logeshwaran, P.; Abinandan, S.; Mukunthan, K.; Megharaj, M. Cyto-genotoxicity evaluation of pyroligneous acid using Allium cepa assay. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2022, 57, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.K.; Ahmad, I. Genotoxicity of chrysotile asbestos on Allium cepa L. meristematic root tip cells. Curr. Sci. 2013, 105, 781–786. [Google Scholar]

- Ozakca, D.U.; Silah, H. Genotoxicity effects of Flusilazole on the somatic cells of Allium cepa. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013, 107, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavareddy, P.; Adhinarayanreddy, V.; Vemanna, R.S.; Sreeman, S.; Makarla, U. Quantification of Membrane Damage/Cell Death Using Evan’s Blue Staining Technique. Bio-Protocol 2017, 7, e2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeen, M.; Mahmood, Q.; Ahmad Bhatti, Z.; Faridullah; Irshad, M.; Bilal, M.; Hayat, M.T.; Irshad, U.; Akbar, T.A.; Arslan, M.; et al. Allium cepa assay based comparative study of selected vegetables and the chromosomal aberrations due to heavy metal accumulation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrete, D.S.; Sánchez, M.D.C.P.; Borjas-García, S.; Tiwari, D.K. Assessment of the Genotoxic Effects of Nanomaterials on Plant Tissues, Using Allium cepa as the Experimental Model Organism. Microsc. Microanal. 2025, 31, ozaf048-461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.M.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Shaikhaldein, H.O. Genotoxic analysis of aqueous extract of Aerva javanica leaves on Allium cepa: Cytogenetic and molecular assessment. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas-Figueroa, F.; Arellano-García, M.E.; Leyva-Aguilera, C.; Ruíz-Ruíz, B.; Luna Vázquez-Gómez, R.; Radilla-Chávez, P.; Chávez-Santoscoy, R.A.; Pestryakov, A.; Toledano-Magaña, Y.; García-Ramos, J.C.; et al. ArgovitTM silver nanoparticles effects on Allium cepa: Plant growth promotion without cyto genotoxic damage. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiskesjö, G. The Allium test as a standard in environmental monitoring. Hereditas 1985, 12, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicuță, D.; Grosu, L.; Patriciu, O.I.; Voicu, R.E.; Alexa, I.C. The Allium cepa model: A review of its application as a cytogenetic tool for evaluating the biosafety potential of plant extracts. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çavuşoğlu, K.; Kalefetoğlu Macar, T.; Macar, O.; Çavuşoğlu, D.; Yalçın, E. Comparative investigation of toxicity induced by UV-A and UV-C radiation using Allium test. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 33988–33998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Bugarín, O.; Arias-Ruiz, L.F. Micronúcleos: Actualización del papel en la inestabilidad genética, inflamación, envejecimiento y cáncer. Revisión panorámica. Rev. Bioméd. 2023, 34, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arık, M.A.; Yalçın, E.; Çavuşoğlu, K.; Özkan, B. Integrated evaluation of methidathion-induced toxicity in Allium cepa with a multifactorial biological approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, N.; Zelena, L. An onion (Allium cepa L.) as a test plant. Biota Hum. Technol. 2023, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, M.A.; de Almeida, L.C.F.; Furtado, R.A.; Cunha, W.R.; Tavares, D.C. Antimutagenicity of rosmarinic acid in Swiss mice evaluated by the micronucleus assay. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2008, 657, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosculete, C.A.; Bonciu, E.; Rosculete, E.; Olaru, L.A. Determination of the environmental pollution potential of some herbicides by the assessment of cytotoxic and genotoxic effects on Allium cepa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artico, L.L.; Kommling, G.; Migita, N.A.; Menezes, A.P.S. Toxicological Effects of Surface Water Exposed to Coal Contamination on the Test System Allium cepa. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.C.; Martins, K.G.; de Vasconcelos, E.C.; Leite, B.Z.; de Assis, T.M.; Barana, A.C. Use of Allium Cepa Test in the Ecotoxicological Evaluation of Sanitary Sewage at Different Stages of Treatment in Two Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTP). Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskesjö, G. The allium test in wastewater monitoring. Environ. Toxicol. Water Qual. 1993, 8, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathiratne, A.; Hemachandra, C.K.; De Silva, N. Efficacy of Allium cepa test system for screening cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of industrial effluents originated from different industrial activities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterich, A.; Gaete, H. Assessment of the genotoxicity of sediment elutriates from an aquatic ecosystem on Allium cepa: Limache stream in central Chile. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, M. Malignancies due to occupational exposure to benzene. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1985, 7, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarac, I.; Bonciu, E.; Butnariu, M.; Petrescu, I.; Madosa, E. Evaluation of the cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of some heavy metals by use of Allium test. Caryologia 2019, 72, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskesjö, G. Allium Test. In In Vitro Toxicity Testing Protocols; O’Hare, S., Atterwill, C., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskesjö, G. Two types of constitutive heterochromatin made visible in Allium by a rapid C-banding method. Hereditas 1974, 78, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskesjö, G. Allium test for screening chemicals; evaluation of cytological parameters. Plants Environ. Stud. 1997, 11, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, P.; Mondal, A.; Hajra, A.; Das, C.; Mondal, N.K. Cytogenetic effects of silver and gold nanoparticles on Allium cepa roots. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Soto, J.C. Citotoxicidad y genotoxicidad de nanopartículas de oro sintetizadas por ablación láser sobre Allium cepa L. (Amaryllidaceae). Arnaldoa 2018, 25, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.S.; Rookes, J.E.; Cahill, D.M.; Lenka, S.K. Reduced Genotoxicity of Gold Nanoparticles with Protein Corona in Allium cepa. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 849464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in Allium cepa. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 5243–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo Paredes, C.R.; Rodríguez Soto, J.C.; Contreras Quiñones, M.; Aspajo Villalaz, C.; Calderón Peña, A.; León Alcántara, E.; Cornejo Roque, B.E.; Aldama Reyna, C.W.; Agreda Delgado, J.; Valverde Alva, M. Citotoxicidad y genotoxicidad de nanopartículas de cobre sobre Allium cepa L. (Amaryllidaceae). Arnaldoa 2020, 27, e108–e112. [Google Scholar]

- Pakrashi, S.; Jain, N.; Dalai, S.; Jayakumar, J.; Chandrasekaran, P.T.; Raichur, A.M.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. In vivo genotoxicity assessment of titanium dioxide nanoparticles by Allium cepa root tip assay at high exposure concentrations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaya, N.; Gill, B.S.; Grover, I.S.; Murin, A.; Osiecka, R.; Sandhu, S.S.; Andersson, H. Vicia faba chromosomal aberration assay. Mutat. Res./Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1994, 310, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy, Ö. Detection of Environmental Mutagens Through Plant Bioassays. In Plant Ecology—Traditional Approaches to Recent Trends; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, C.; Feretti, D.; Viola, G.V.C.; Zerbini, I.; Bisceglie, F.; Pelosi, G.; Zani, C.; Buschini, A.; Carcelli, M.; Rogolino, D.; et al. Allium cepa tests: A plant-based tool for the early evaluation of toxicity and genotoxicity of newly synthetized antifungal molecules. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2023, 889, 503654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Rathore, H.; Rathore, M.; Panchal, S.; Makwana, M.; Sharma, A.; Shrivastava, S. Can genotoxic effect be model dependent in Allium test?—An evidence. Environment Asia 2010, 3, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Barbério, A.; Voltolini, J.C.; Mello, M.L.S. Standardization of bulb and root sample sizes for the Allium cepa test. Ecotoxicology 2011, 20, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.