Simple Summary

Zoonotic diseases are strongly influenced by environmental and social changes. In Brazil, factors such as deforestation, urban growth, poverty, and climate variation affect where and how these diseases occur. This study brings together scientific information to understand how these drivers shape the patterns of major zoonotic diseases in Brazil. By analyzing research trends, themes, and geographic distribution, we identified where knowledge is lacking. The results show that scientific attention mirrors the country’s environmental and social challenges, especially in regions under high human pressure like the Amazon and Cerrado. This work helps reveal how ecological degradation and social inequality contribute to disease risk and highlights the importance of integrating environmental and health data to guide prevention and early-warning systems.

Abstract

Zoonotic diseases represent an important interface between socio-environmental change and public health, yet integrative assessments linking ecological and social determinants remain limited in tropical regions. This study mapped how socio-environmental drivers have shaped research patterns on zoonotic diseases in Brazil. We integrated socio-environmental data from empirical evidence with statistical modeling to evaluate temporal trends, thematic associations, and geographic distribution across six major zoonoses: leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, leptospirosis, yellow fever, Brazilian spotted fever, and hantavirus infection. Research output increased after 2010, particularly for leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, and leptospirosis, reflecting growing recognition of land-use change and socioeconomic vulnerability as key drivers of disease risk. Network analyses revealed strong thematic connections between zoonoses and land-use or socioeconomic factors, whereas climate change remained underrepresented. Spatially, research efforts were concentrated in the Amazon and Cerrado biomes, underscoring both ecological significance and persistent regional disparities in knowledge production. These findings demonstrate that Brazil’s zoonotic research landscape mirrors broader socio-environmental pressures, where deforestation, poverty, and climatic variability jointly influence disease dynamics. Strengthening geographically inclusive and environmentally informed research frameworks that integrate climate, land-use, and surveillance data will be essential to improve early-warning systems and guide sustainable, cross-sectoral public health policies.

1. Introduction

Environmental, climatic, and socioeconomic changes are closely linked to the emergence of zoonoses, which account for more than 60% of human infectious diseases [1,2]. In Brazil, the combination of high biodiversity, accelerated land-use change, persistent environmental degradation, and social inequalities creates favorable conditions for the emergence and reemergence of zoonotic pathogens [3,4]. Despite their relevance to public health, understanding how these multiple drivers interact to shape zoonotic risk remains fragmented.

Brazil encompasses six major biomes (Amazon, Cerrado, Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Pantanal, and Pampa), each characterized by distinct climatic regimes, vegetation structures, and biodiversity profiles that influence zoonotic transmission dynamics [5]. The Amazon is dominated by extensive tropical rainforest; the Cerrado by seasonally dry savanna formations; and the Atlantic Forest by humid evergreen and semi-deciduous forests. The Caatinga consists of semi-arid shrublands, the Pantanal represents one of the world’s largest floodplains with pronounced seasonal hydrological cycles, and the Pampa is characterized by temperate grasslands [6]. These ecological contrasts shape vector distributions, reservoir communities, and human exposure patterns, emphasizing the value of biogeographical context in assessing zoonotic risk across Brazil.

Among the zoonotic diseases present in the country, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, leptospirosis, yellow fever, Brazilian spotted fever, and hantavirus infection stand out due to their epidemiological significance and well-established environmental determinants [7]. They are consistently represented in national surveillance systems and in scientific literature, reflecting their substantial burden and broad geographic distribution. Each exhibits clear links to socio-environmental variables, enabling meaningful comparisons across spatial and temporal gradients [8]. Focusing on this group of high-impact zoonoses, therefore, provides a coherent empirical basis for examining how environmental and social pressures shape disease patterns at the national scale.

Zoonotic diseases impose substantial morbidity, mortality, and economic losses across Brazil, disproportionately affecting populations with limited access to sanitation, healthcare, and environmental protection [9]. Beyond their clinical burden, they demand considerable investment in surveillance, vector control, environmental management, and hospital care [3]. The country reports thousands of cases annually due to its ecological diversity and persistent social and environmental vulnerabilities [8]. Clarifying the mechanisms that drive the emergence, persistence, and expansion of these pathogens is essential to strengthen early detection, guide preventive interventions, and inform evidence-based public health policy.

The conversion of natural ecosystems, unplanned urban expansion, and extreme climatic events alter the distribution of vectors and reservoirs, directly influencing zoonotic transmission cycles [10,11]. These drivers rarely act in isolation; instead, they interact through nonlinear and region-specific pathways [12]. However, much of the Brazilian literature remains compartmentalized by disease or region, lacking integrative assessments that capture nationwide patterns linking environmental and social dynamics to zoonotic risk [13].

Integrating environmental, climatic, and socioeconomic data through statistical modeling provides a coherent framework for understanding the drivers of major zoonotic diseases in Brazil, including leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, leptospirosis, yellow fever, Brazilian spotted fever, and hantavirus infection. By combining this data with empirical evidence, such approaches situate scientific knowledge within the real-world conditions that shape disease risk. This study examines how environmental and social factors jointly influence the spatial dynamics of these diseases across Brazil, identifying key determinants and highlighting both ecological and regional knowledge gaps. The findings contribute to environmental health and ecosystem sustainability by clarifying the complex relationships among ecological processes, human activities, and zoonotic transmission.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Compilation

This study was conducted on 25 August 2025, to assess how socio-environmental drivers are linked to zoonotic diseases in Brazil. Data were compiled from Scopus, Web of Science, and SciELO, which collectively ensure broad discipline and nationwide coverage. Combining these sources, expanded representativeness and minimized potential bias due to database-specific limitations [14].

The dataset included all records available until 30 June 2025, without retrospective time restriction, ensuring complete temporal coverage of the research landscape. The search strategy was based on thematic categories related to zoonoses and socio-environmental threats in Brazil (Table 1). We included original peer-reviewed articles from the fields of ecology, epidemiology, environmental sciences, public health, and tropical medicine that addressed ecological, epidemiological, or socio-environmental aspects of zoonoses. Reviews, meta-analyses, book chapters, editorials, technical notes, preprints, and studies not explicitly linked to the Brazilian territory were excluded. Data selection followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Although our review does not fully align with a traditional systematic review, we applied PRISMA guidelines to standardize article identification and selection. This ensured a transparent and reproducible screening process and allowed consistent extraction of information for subsequent quantitative analyses. While our methodological framework is unconventional, it is replicable and offers an innovative approach for synthesizing and analyzing literature-based data.

Table 1.

Descriptors and search terms used to identify zoonotic diseases and associated socio-environmental drivers in publications related to Brazil. Keywords were standardized to group synonymous terms in English and Portuguese, allowing consistent classification across thematic categories and geographic regions.

2.2. Data Processing

Records were filtered by language (English or Portuguese) to ensure consistency and nationwide relevance. The initial dataset comprised 2284 records (Scopus = 1126; Web of Science = 797; SciELO = 361). After removing duplicates, 1903 unique records were screened by titles, abstracts, and keywords by two independent reviewers. A total of 1188 records were excluded due to lack of relevance to zoonoses or socio-environmental factors, or because they focused solely on clinical or veterinary aspects. The remaining 715 records underwent full-text review, with 258 excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria. The final dataset included 457 records.

To assess data reliability, a random sample of 100 records was independently evaluated by two reviewers. This subsample, representing 22% of all included studies, is consistent with methodological guidance suggesting that screening approximately 20–30% of the dataset provides a reliable estimate of inter-rater agreement while remaining operationally feasible [15]. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, and inter-rater agreement was quantified using Cohen’s kappa (κ = 0.85; p < 0.01), indicating substantial concordance. To verify search comprehensiveness, the ten most productive authors in zoonoses and socio-environmental health research in Brazil were cross-referenced against indexed outputs, confirming that no major omissions occurred.

2.3. Analytical Framework

Analyses were performed in GNU R 4.4.1 [16]. The dplyr [17] and stringr [18] packages were used to standardize terminology for the six zoonoses (Leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, Leptospirosis, Yellow fever, Brazilian spotted fever, Hantavirus infection) and for the four socio-environmental drivers (land-use change, biodiversity loss, climate change, and socioeconomic factors). Because the included studies differed in design and measured variables, these socio-environmental drivers were not identically reported across publications. To ensure comparability, we harmonized the reported variables into the four thematic categories listed above, reflecting consistent patterns described in the literature. This standardization enabled a coherent synthesis of otherwise heterogeneous evidence. In addition, cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis were combined under the unified category “Leishmaniasis”.

Temporal trends in research activity and associations with socio-environmental drivers were assessed using the Mann–Kendall test (Kendall package, [19]), which is appropriate for detecting monotonic, non-linear trends without assuming normality. Thematic networks were constructed to visualize associations between zoonoses and socio-environmental drivers, where link color reflected connection strength, allowing identification of dominant clusters and relationships.

The relative importance of each driver was quantified through Random Forest models (randomForest package, [20]) fitted separately for each zoonosis, with parameters ntree = 1000 and mtry = 4. The number of studies related to each zoonosis served as the response variable, while socio-environmental drivers were used as predictors. Variable importance was estimated by the mean decrease in accuracy, and model performance was evaluated using pseudo-R2, representing the proportion of variance explained.

Spatial analyses were performed with geobr [21] and sf [22] packages, using official IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística) biome shapefiles. Records were aggregated by biome and linked to their total area (km2). The relationship between biome size and zoonoses frequency was modeled using Generalized Additive Models (GAM) with a quasi-Poisson distribution (mgcv package, [23]) to capture non-linear relationships and manage data dispersion.

2.4. Ethical Aspects

All the data are secondary, publicly available, and anonymized, ensuring that there is no possibility of individual identification. Therefore, the study was not submitted for research ethics committee review.

3. Results

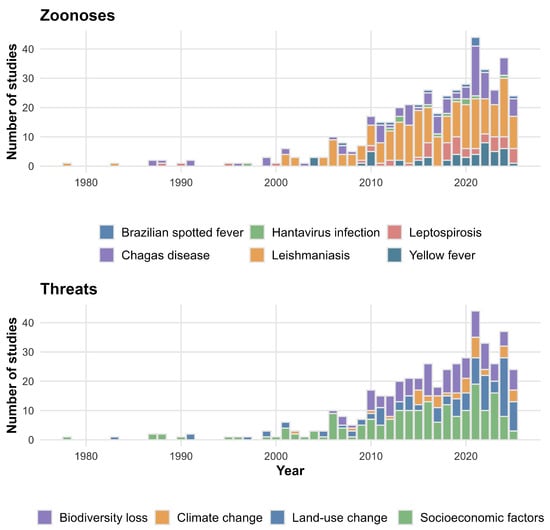

Research addressing zoonoses and socio-environmental drivers increased after 2010 (Figure 1). The Mann–Kendall test indicated significant upward trends for leishmaniasis (τ = 0.67; p < 0.001), Chagas disease (τ = 0.51; p < 0.001), and leptospirosis (τ = 0.59; p < 0.01). In contrast, yellow fever (τ = 0.32; p = 0.13), Brazilian spotted fever (τ = 0.26; p = 0.38), and hantavirus infection (τ = 0.01; p = 0.98) did not show significant growth. Research emphasis was highest for land-use change (τ = 0.73; p < 0.001) and socioeconomic factors (τ = 0.62; p < 0.001), with more recent increases in climate change studies (τ = 0.49; p = 0.02). Biodiversity loss remained stable, showing marginal significance (τ = 0.34; p = 0.06).

Figure 1.

Trends in the number of studies addressing major zoonotic diseases (top panel) and socio-environmental threats (bottom panel).

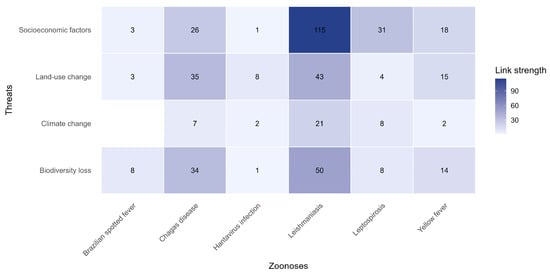

Network analyses revealed strong linkages between zoonoses and socio-environmental drivers (Figure 2). Random Forest importance values supported these patterns (Table 2), indicating robust model performance (see pseudo-R2 in Table 2). Socioeconomic factors exhibited the strongest associations with leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, leptospirosis, and yellow fever. Land-use change was strongly correlated with leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, and yellow fever, while biodiversity loss was primarily linked to leishmaniasis and Chagas disease. Climate change showed weaker and less consistent relationships only with leishmaniasis.

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating the links between six zoonotic diseases and major environmental and social drivers. The color gradient represents the relative network frequency between zoonoses and threats.

Table 2.

Results of Random Forest models fitted separately for each zoonotic disease to estimate the importance of socio-environmental threats. Variable importance was expressed as the mean decrease in accuracy, and model performance was evaluated using pseudo-R2 values representing the proportion of explained variance.

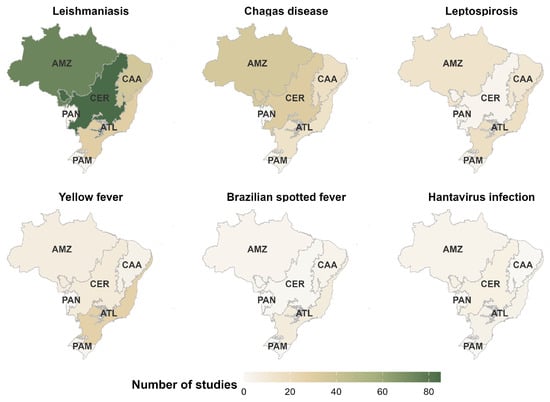

Geographically, the Amazon and Cerrado biomes dominated research on leishmaniasis and Chagas disease (Figure 3). The Amazon, Caatinga, and Atlantic Forest concentrated most leptospirosis studies, while yellow fever was most frequent in the Atlantic Forest. Brazilian spotted fever and hantavirus infections were underrepresented across all biomes. The relationship between biome size and study frequency followed a positive, non-linear pattern (β = 3.84; p < 0.01; R2 = 0.99), indicating greater research intensity in larger, ecologically complex regions.

Figure 3.

Maps showing the spatial distribution of studies for six zoonotic diseases across the main Brazilian biomes: Amazon (AMZ), Cerrado (CER), Caatinga (CAA), Atlantic Forest (ATL), Pantanal (PAN), and Pampa (PAM).

4. Discussion

Increased research on zoonoses and socio-environmental factors in Brazil reflects a growing integration between environmental and health sciences. Over the past two decades, however, research activity across major environmentally mediated and vector-borne zoonoses has been uneven. Leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, and leptospirosis have dominated scientific output, while yellow fever, Brazilian spotted fever, and hantavirus infections have received comparatively stable attention. These contrasts arise from well-defined historical, institutional, and epidemiological contexts [1,8].

Long-standing national control programs for leishmaniasis and Chagas disease, established in the 1970s and 1980s, strengthened diagnostic networks, entomological surveillance, and academic expertise, while their chronic disease profiles and broad geographic ranges supported sustained investment [7]. Leptospirosis remains a priority among municipal and state authorities due to its strong association with flooding, inadequate sanitation, and high urban density, maintaining continuous research attention [24]. Conversely, interest in yellow fever oscillates with epidemic cycles, intensifying during outbreaks and decreasing during inter-epidemic periods [25]. Brazilian spotted fever research is constrained by its focal distribution and reliance on specialized diagnostics, whereas hantavirus infections remain infrequent and require high-containment laboratory facilities, limiting surveillance and scientific productivity [7].

The associations identified between zoonoses and socio-environmental drivers underscore the tightly interconnected nature of ecological and social processes [13,26]. Diseases with broader geographic distribution are consistently linked to poverty, rapid urbanization, and deficient infrastructure, highlighting social vulnerability as a central determinant of exposure [24,27]. Land-use change, particularly deforestation, agricultural expansion, and habitat fragmentation, emerge as a major eco-epidemiological driver by disrupting natural habitats and increasing human–wildlife contact [26]. Expanding agricultural frontiers alter microclimates and resource availability, concentrating vectors and reservoirs along human-modified edges [28]. Unplanned urbanization further amplifies these dynamics: inadequate sanitation, poor waste management, and dense informal settlements create favorable conditions for synanthropic hosts, sustaining urban cycles of environmentally mediated diseases such as leptospirosis and Chagas disease [29].

The domestication and illegal trade of wildlife weaken ecological barriers and promote novel interfaces among humans, domestic animals, and wild species, facilitating spillovers across both vector-borne and non-vector-borne pathogens [26]. Together, these socio-environmental disruptions undermine natural buffers and create interconnected habitats that heighten transmission potential across diverse settings [30]. Although studies linking climate change and health are expanding, they remain underrepresented in zoonotic contexts, underscoring the need for integrative approaches that consider combined ecological, climatic, and socioeconomic pressures across multiple transmission modes [31].

Research remains disproportionately concentrated on the Amazon and Cerrado, biomes characterized by high biodiversity and strong anthropogenic pressure [32]. This pattern reflects both ecological relevance and the presence of established research infrastructure [26]. In contrast, the Caatinga and Pampa biomes remain underexplored, revealing geographic asymmetries in scientific production and disease surveillance. The positive correlation between biome size and research effort suggests a bias toward large and accessible ecosystems, potentially overlooking smaller yet epidemiologically significant regions. Such imbalances may hinder the early detection of emerging hotspots in ecologically fragile and socially vulnerable landscapes [33].

These findings carry important implications for public health planning. By clarifying which socio-environmental drivers most strongly shape zoonotic transmission systems, the results highlight opportunities to strengthen early-warning frameworks that integrate deforestation alerts, climatic anomalies, land-use information, and social vulnerability indicators [8]. Prioritizing surveillance in rapidly changing landscapes can enhance detection of both vector-borne and environmentally mediated zoonoses [4]. Such integrative frameworks are essential for understanding how environmental and social pressures jointly influence the distribution of vector-borne pathogens, urban and peri-urban bacterial hazards, and rodent-borne viral threats, reinforcing the need for coordinated, preventive public health strategies.

Zoonoses in Brazil arise from interdependent socio-environmental pressures, with poverty, land conversion, and climatic variability jointly shaping exposure and transmission dynamics [13,25,34]. These insights underscore the importance of interdisciplinary approaches linking ecosystem degradation, climate variability, and social inequality within a broader socio-environmental health perspective. Still, several limitations must be acknowledged. Reliance on literature-derived data may underrepresent regional or non-indexed sources; study frequency reflects research attention rather than disease incidence; and the absence of surveillance or field data constrains mechanistic inference regarding vector and reservoir dynamics.

Despite these limitations, the study demonstrates the value of integrating socio-environmental evidence to identify thematic and geographic gaps in zoonotic research. Scientific attention remains uneven across diseases, drivers, and biomes, often shaped more by institutional priorities than epidemiological need. Future work should strengthen quantitative integration among climate variables, land-use data, and disease metrics to elucidate environmental feedback on zoonotic dynamics. Expanding interdisciplinary collaborations on neglected zoonoses, particularly under climate change scenarios, will be essential for forecasting risks and guiding adaptive environmental and health policies [35]. Strengthening monitoring systems that couple deforestation alerts, land-use change indicators, and disease surveillance can enhance early-warning capacity in tropical regions and support more proactive, geographically tailored strategies for prevention and control.

5. Conclusions

Research on zoonoses in Brazil has expanded markedly, particularly for leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, and leptospirosis. This trend mirrors growing recognition of land-use change, biodiversity loss, and socioeconomic vulnerability as central determinants of disease risk. The results emphasize the interdependence between ecosystem integrity and zoonotic transmission, reinforcing the need to integrate socio-environmental indicators within health research and policy. The predominance of studies in the Amazon and Cerrado highlights their ecological and epidemiological importance but also exposes underrepresented regions. Developing geographically inclusive and socio-environmentally grounded frameworks for zoonotic surveillance and risk assessment will be crucial to guide sustainable land management, strengthen early-warning systems, and inform adaptive environmental health policies across diverse landscapes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.D.S. and D.S.; formal analysis, D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.D.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and R code associated with this manuscript are available on figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30395965.v1, accessed on 25 August 2025).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Max Kedley Maranhão from Afya Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Bragança for assisting with English grammar checking.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cediel-Becerra, N.M.; Olaya Medellin, A.M.; Tomassone, L.; Chiesa, F.; de Meneghi, D. A survey on One Health approach in Colombia and some Latin American countries: From a fragmented health organization to an integrated health response to global challenges. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 649240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, A.; Prist, P.R.; Marrelli, M.T. Biodiversity and Public Health Interface. Biota Neotrop. 2022, 22, e20221372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga-Samanez, A.; Romero, D.; Murray, K.A.; Cobos-Mayo, M.; Segura, M.; Real, R.; Olivero, J. Climate Change Is Aggravating Dengue and Yellow Fever Transmission Risk. Ecography 2024, 2024, e06942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaz, V.R.; Rocha, J.C.; Sánchez-García, P.A.; Dauriach, A.; Roukny, T.; Jørgensen, P.S. Financial Influence on Global Risks of Zoonotic Emerging and Re-Emerging Diseases: An Integrative Analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e951–e962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, L.A.V.; Garcez, D.S.; Campos da Silva, M.; Gurgel-Lourenço, R.C.; Pinto, L.M.; Valentim, G.A.; Batista, L.B.; Avelar, V.S.; Siqueira, W.L.X.; Loiola, S.C.; et al. BRValuation: A systematic comparison of ecosystem services across Brazilian biomes and ecosystems. Environ. Dev. 2025, 56, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.; Reis, L.K.; Borges, F.L.G.; Ojeda, P.T.A.; Pineda, D.A.M.; Miranda, C.O.; de Lima Maidana, D.P.F.; dos Santos, T.M.R.; Shibuya, P.S.; Marques, M.C.M.; et al. Ecological restoration in Brazilian biomes: Identifying advances and gaps. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 458, 117802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico: Morbimortalidade por Zoonoses no Brasil 2007–2023; Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde e Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 2025.

- Carvalho, R.L.; Anjos, D.; Harmange, C.; Pinter, A.; Faust, C.; Streicker, D.; Lorenz, C.; Prist, P.R.; Metzger, J.P. Unpacking the Risks of Zoonotic and Vector-Borne Pathogen Transmission to Humans in the Context of Environmental Change. One Earth 2025, 8, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwanger, J.H.; Fearnside, P.M.; Ziliotto, M.; Valverde-Villegas, J.M.; da Veiga, A.B.G.; Vieira, G.F.; Bach, E.; Cardoso, J.C.; Müller, N.F.D.; Lopes, G.; et al. Synthesizing the Connections Between Environmental Disturbances and Zoonotic Spillover. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2022, 94, e20211530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Jiménez, J.L.; Gutiérrez, J.D.; Altamiranda-Saavedra, M. The effect of El Niño and La Niña episodes on the existing niche and potential distribution of vector and host species of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Acta Trop. 2024, 249, 107060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prist, P.R.; Prado, A.F.; Tambosi, L.R.; Umetsu, F.; de Arruda Bueno, A.; Pardini, R.; Metzger, J.P. Moving to healthier landscapes: Forest restoration decreases the abundance of Hantavirus reservoir rodents in tropical forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Roque, F.; Herrera, H.M.; de Andrade, G.B.; Johnson, M.F.; Nunes, A.V.; Oliveira, A.G.D.; de Castro Ferreira, E.; Fernandes, G.W.; Araújo, G.A.; Santos, L.G.R.O.; et al. One Health tropical wetlands: A transdisciplinary framework for assessing the risks of emerging zoonotic diseases in the Brazilian Pantanal. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 33, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.R.; Codeço, C.T.; Svenning, J.C.; Escobar, L.E.; van de Vuurst, P.; Gonçalves-Souza, T. Neglected Tropical Diseases Risk Correlates with Poverty and Early Ecosystem Destruction. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnham, J.F. Scopus Database: A Review. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, 1.1.4. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dplyr/index.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Wickham, H. stringr: Simple, Consistent Wrappers for Common String Operations, 1.5.2. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/stringr/index.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- McLeod, A.I. Kendall: Kendall Rank Correlation and Mann-Kendall Trend Test, 2.2.1. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Kendall/index.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R.H.M.; Goncalves, C.N. geobr: Download Official Spatial Data Sets of Brazil, 1.9.1. 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/geobr/index.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Pebesma, E. Simple features for R: Standardized support for spatial vector data. R J. 2018, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric Generalized Linear Models. J. R. Stat. Soc. B Stat. Methodol. 2010, 73, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D.S.; Khalil, H.; Palma, F.A.G.; Santana, R.; Nery, N.R.R.; Quintero Vélez, J.C.; Zeppelini, C.G.; Sacramento, G.A.D.; Cruz, J.S.; Lustosa, R.; et al. Factors associated with differential seropositivity to Leptospira interrogans and Leptospira kirschneri in a high transmission urban setting for leptospirosis in Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0011292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlet, A.; Gaythorpe, K.A.M.; Garske, T.; Ferguson, N.M. Seasonal and inter-annual drivers of yellow fever transmission in south America. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0008974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Prado, E.; Yeager, J.; Vasconez-Gonzalez, J.; Culqui-Sánchez, M.V.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S. Integrating environmental conservation and public health strategies to combat zoonotic disease emergence: A call to action from the Amazon rainforest. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1405472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Santana, R.; de Oliveira, D.S.; Palma, F.A.G.; Lustosa, R.; Eyre, M.T.; Carvalho-Pereira, T.S.D.A.; Reis, M.G.; Koid, A.I.; Diggle, P.J.; et al. Poverty, sanitation, and leptospira transmission pathways in residents from four Brazilian slums. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlet, A.; Ramos, D.G.; Gaythorpe, K.A.M.; Romano, A.P.M.; Garske, T.; Ferguson, N.M. Seasonality of agricultural exposure as an important predictor of seasonal yellow fever spillover in Brazil. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durães, L.S.; Bitencourth, K.; Ramalho, F.R.; Nogueira, M.C.; Nunes, E.D.C.; Gazêta, G.S. Biodiversity of potential vectors of Rickettsiae and epidemiological mosaic of spotted fever in the State of Paraná, Brazil. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 577789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmeirim, A.F.; Barreto, J.R.; Prist, P.R. The importance of Indigenous Lands and landscape structure in shaping the zoonotic disease risk: Insights from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. One Health 2025, 21, 101104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J.I.M.; Kmetiuk, L.B.; Farias, M.; Gonçalves, G.; Freitas, A.R.; Biondo, L.M.; de Paula, C.A.; Delai, R.R.; Pimpão, C.T.; Perotta, J.H.; et al. One Health approach to Trypanosoma cruzi: Serological and molecular detection in owners and dogs living on oceanic islands and seashore mainland of Southern Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winck, G.R.; Raimundo, R.L.G.; Fernandes-Ferreira, H.; Bueno, M.G.; D’Andrea, P.S.; Rocha, F.L.; Cruz, G.L.T.; Vilar, E.M.; Brandão, M.L.; Cordeiro, J.L.P.; et al. Socioecological vulnerability and the risk of zoonotic disease emergence in Brazil. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, N.N.H.; Prist, P.R.; Uríarte, M. Environmental and socioeconomic risk factors for visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in São Paulo, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 797, 148960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.D.S.; Ursine, R.L.; Cardozo, M.; Matos, R.L.F.D.R.; de Souza, R.d.C.M.; Diotaiuti, L.G.; Gorla, D.E.; de Carvalho, S.F.G.; Vieira, T.M. Socio-environmental factors associated with the occurrence of triatomines (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in an endemic municipality in northern Minas Gerais, Brazil. Zoonoses Public Health 2024, 71, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakimoto, M.D.; Menezes, R.C.; Nery, T.M.M.; Nunes, N.C.; Pereira, S.A.; Veloso, V.G. One health governance: Recent advances in Brazil. One Health 2025, 20, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).